Abstract

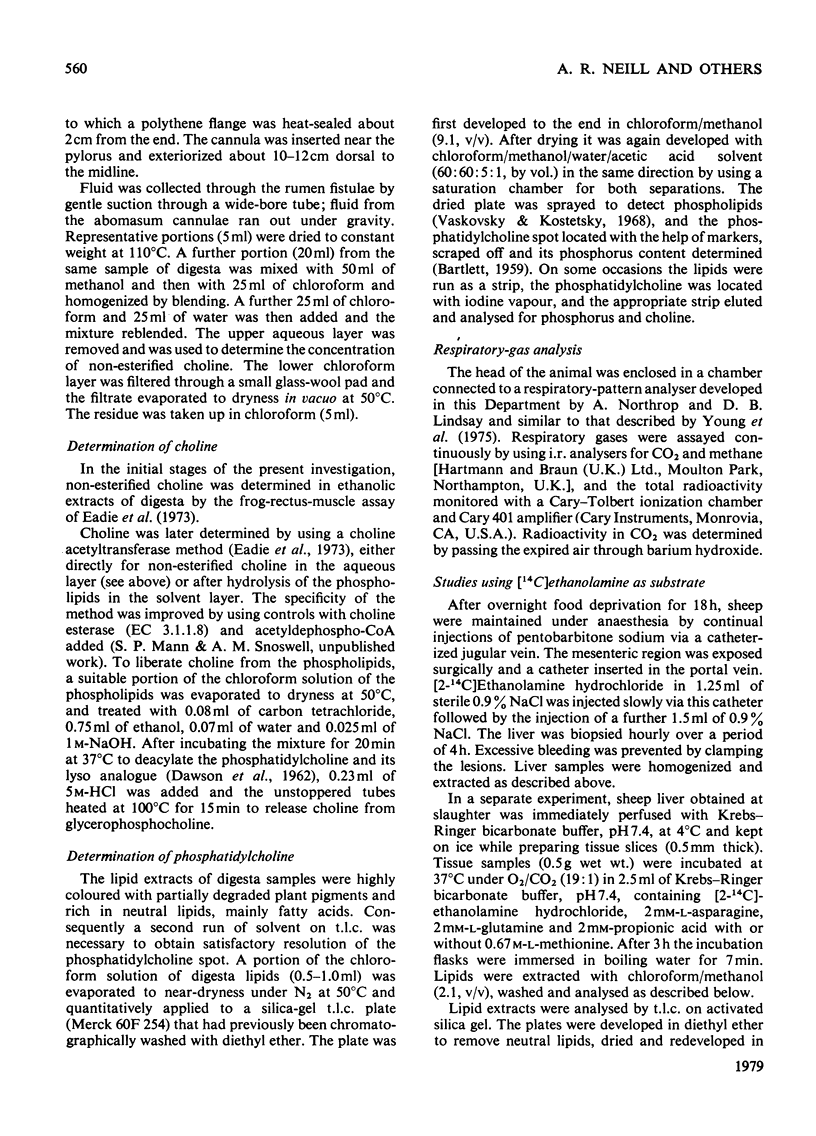

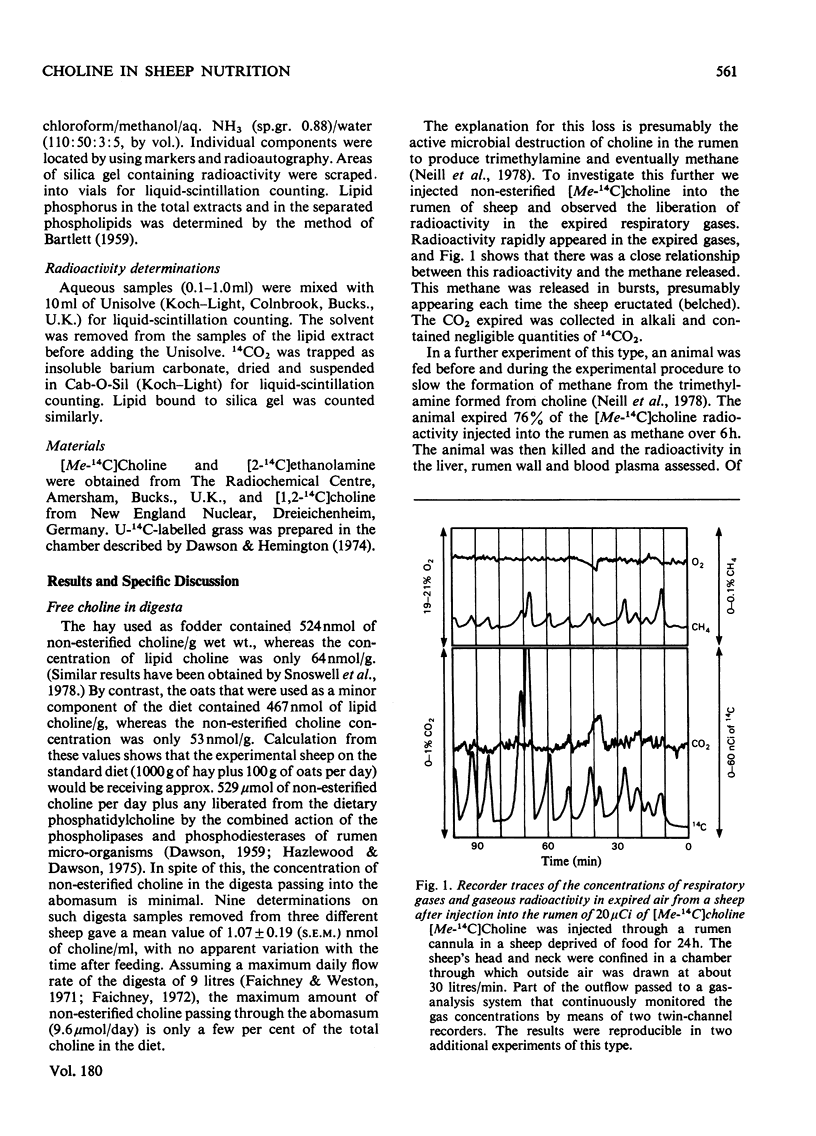

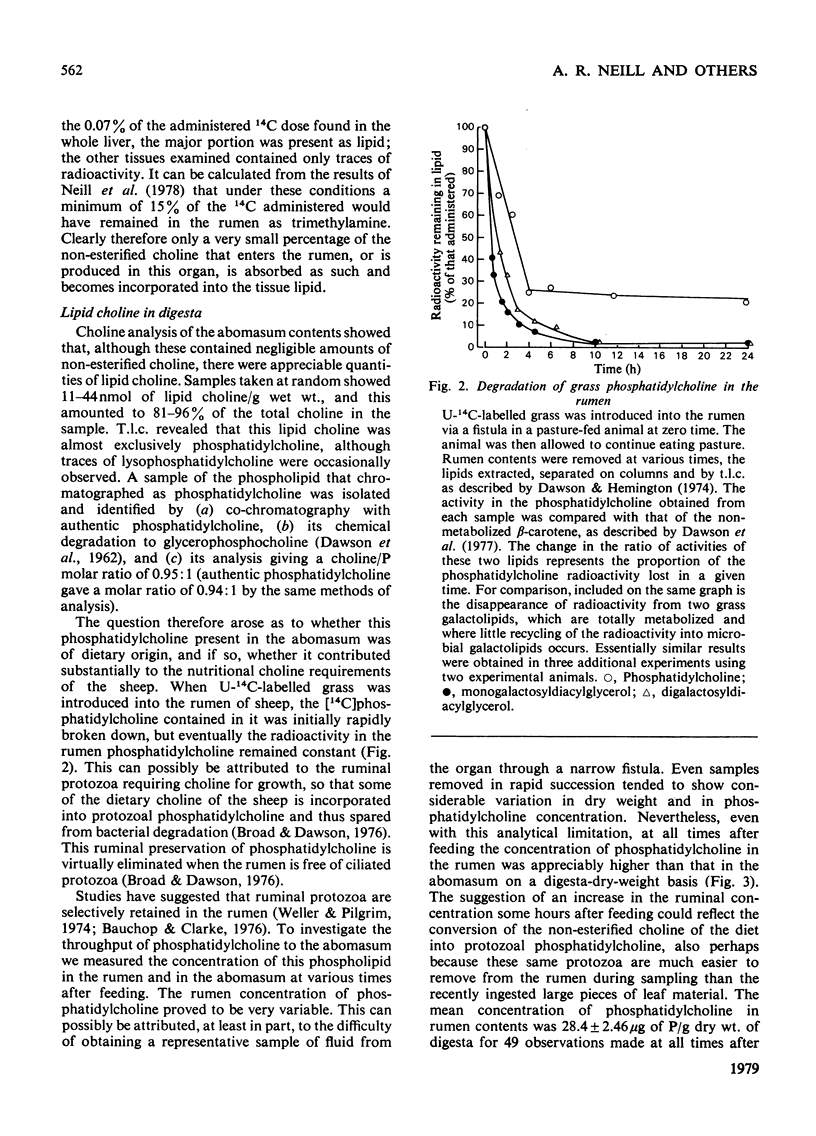

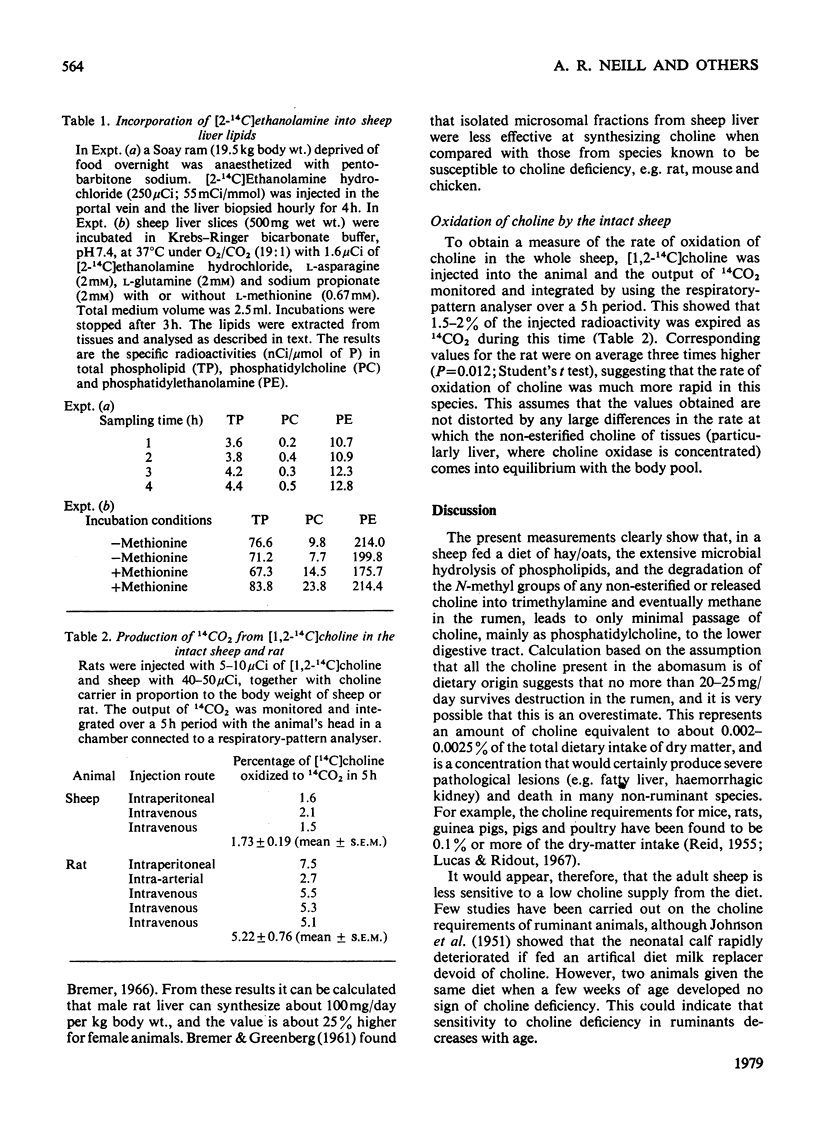

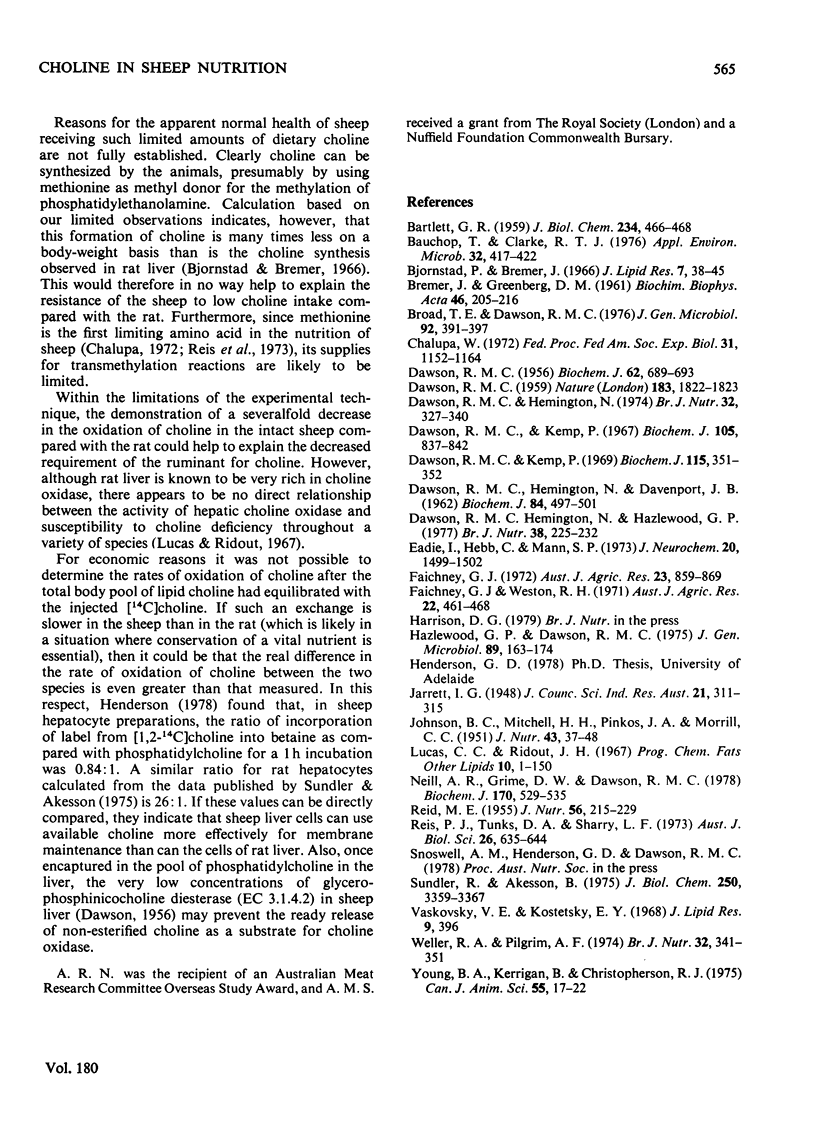

1. Choline, which is present in the diet of the sheep either in the non-esterified form or combined in phospholipids, is rapidly degraded in the rumen. The ultimate product formed from the N-methyl groups is methane. 2. Analysis of the non-esterified choline and the phosphatidylcholine in ruminal and abomasal digesta indicate that the phospholipid is the main vehicle for the passage of choline to the lower digestive tract. 3. The concentration of phosphatidylcholine in abomasal digesta is lower than that of ruminal digesta, which is in line with a selective retention of protozoa in the rumen as observed by others. 4. On defaunation of the rumen to remove ciliated protozoa the concentration of phosphatidylcholine in ruminal digesta falls markedly and becomes lower than that in abomasal digesta. 5. Calculation shows that the adult sheep obtains at most only about 20--25 mg of effective choline per day from its diet (0.002--0.0025% of dietary total dry-weight intake). This is some fifty times less than the minimum required to avoid pathological lesions and death in other species investigated (0.1%+ of dietary dry-weight intake). 6. Sheep liver can synthesize choline from [14C]ethanolamine both in vitro and in vivo, but the synthesis of choline per kg body weight is many times less than it is in the rat. 7. The intact sheep oxidizes an injected dose of [1,2-14C]choline to CO2 at a rate that is several times less than that observed for the rat. This could help to explain the apparent minimal requirement of sheep for dietary choline.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- BARTLETT G. R. Phosphorus assay in column chromatography. J Biol Chem. 1959 Mar;234(3):466–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauchop T., Clarke R. T. Attachment of the ciliate Epidinium Crawley to plant fragments in the sheep rumen. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1976 Sep;32(3):417–422. doi: 10.1128/aem.32.3.417-422.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjørnstad P., Bremer J. In vivo studies on pathways for the biosynthesis of lecithin in the rat. J Lipid Res. 1966 Jan;7(1):38–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broad T. E., Dawson R. M. Role of choline in the nutrition of the rumen protozoon Entodinium caudatum. J Gen Microbiol. 1976 Feb;92(2):391–397. doi: 10.1099/00221287-92-2-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalupa W. Metabolic aspects of nonprotein nitrogen utilization in ruminant animals. Fed Proc. 1972 May-Jun;31(3):1152–1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAWSON R. M., HEMINGTON N., DAVENPORT J. B. Improvements in the method of determining individual phospholipids in a complex mixture by successive chemical hydrolyses. Biochem J. 1962 Sep;84:497–501. doi: 10.1042/bj0840497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAWSON R. M. Liver glycerylphosphorylcholine diesterase. Biochem J. 1956 Apr;62(4):689–693. doi: 10.1042/bj0620689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson R. M., Hemington N. Digestion of grass lipids and pigments in the sheep rumen. Br J Nutr. 1974 Sep;32(2):327–340. doi: 10.1079/bjn19740086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson R. M., Hemington N., Hazlewood G. P. On the role of higher plant and microbial lipases in the ruminal hydrolysis of grass lipids. Br J Nutr. 1977 Sep;38(2):225–232. doi: 10.1079/bjn19770082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson R. M., Kemp P. The aminoethylphosphonate-containing lipids of rumen protozoa. Biochem J. 1967 Nov;105(2):837–842. doi: 10.1042/bj1050837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson R. M., Kemp P. The effect of defaunation on the phospholipids and on the hydrogenation of unsaturated fatty acids in the rumen. Biochem J. 1969 Nov;115(2):351–352. doi: 10.1042/bj1150351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eade I., Hebb C., Mann S. P. Free choline levels in the rat brain. J Neurochem. 1973 May;20(5):1499–1502. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1973.tb00266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHNSON B. C., MITCHELL H. H., PINKOS J. A. Choline deficiency in the calf. J Nutr. 1951 Jan;43(1):37–48. doi: 10.1093/jn/43.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neill A. R., Grime D. W., Dawson R. M. Conversion of choline methyl groups through trimethylamine into methane in the rumen. Biochem J. 1978 Mar 15;170(3):529–535. doi: 10.1042/bj1700529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REID M. E. Nutritional studies with the guinea pig. III. Choline. J Nutr. 1955 Jun 10;56(2):215–229. doi: 10.1093/jn/56.2.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis P. J., Tunks D. A., Sharry L. F. Plasma amino acid patterns in sheep receiving abomasal infusions of methionine and cystine. Aust J Biol Sci. 1973 Jun;26(3):635–644. doi: 10.1071/bi9730635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundler R., Akesson B. Regulation of phospholipid biosynthesis in isolated rat hepatocytes. Effect of different substrates. J Biol Chem. 1975 May 10;250(9):3359–3367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaskovsky V. E., Kostetsky E. Y. Modified spray for the detection of phospholipids on thin-layer chromatograms. J Lipid Res. 1968 May;9(3):396–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller R. A., Pilgrim A. F. Passage of protozoa and volatile fatty acids from the rumen of the sheep and from a continuous in vitro fermentation system. Br J Nutr. 1974 Sep;32(2):341–351. doi: 10.1079/bjn19740087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]