Abstract

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) is characterized by the regurgitation of stomach contents. Recent research indicates that acid reflux may disrupt the homeostasis of the middle and inner ear through the Eustachian tube. Given this context, we hypothesized that an association between GERD and tinnitus may exist due to the imbalance of the middle and inner ear caused by acid reflux. To explore this connection, we conducted a retrospective cohort study involving 669,159 patients registered in the National Health Insurance Service-National Sample Cohort (2012–2019) in South Korea. Our data showed that GERD and tinnitus are highly associated. Nevertheless, the use of proton pump inhibitor medication in GERD patients did not show a significant decrease in the onset of tinnitus.

Keywords: Gastroesophageal reflux disease, Tinnitus, Nationwide cohort study

Subject terms: Gastroenterology, Medical research

Introduction

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) is a condition characterized by the backflow of stomach contents, especially gastric acids, leading to troublesome symptoms and potential complications1–3. GERD is a prevalent disorder of the digestive system, with an estimated global prevalence of 13.3% in the population4. Daily habits such as smoking, dietary choices, and medication use can serve as risk factors for GERD1,2. Despite its high prevalence, GERD is often overlooked due to its relatively low mortality and severity compared to other digestive system diseases5. However, neglecting GERD can lead to chronic exposure to gastric acids and various gastric and non-gastric complications, including chronic gastritis, chronic cough, posterior laryngitis, and pharyngitis6,7. Furthermore, recent studies have shown that acid reflux can influence the homeostasis of the middle and inner ear via the Eustachian tube8,9. Based on this background, it is highly suggested that consistent GERD may modulate the normal physiological conditions of various anatomical structures in head and neck region.

Tinnitus is a condition characterized by the perception of sounds that lack an external source10,11. Tinnitus, though not widely acknowledged, is a prevalent condition affecting approximately 10% of the adult population10,11. While various factors, such as issues with the middle/inner ear, peripheral nervous system, and central nervous system, can contribute to tinnitus10, the precise pathophysiological mechanism of tinnitus remains unknown. However, it is well known that the most common cause of tinnitus initiation is a cochlear dysfunction10,12. In particular, even though the precise mechanism remains unclear, acids refluxed through the Eustachian tube may disrupt the round window membrane, which serves as one of the openings connecting the middle ear to the inner ear9,13. From this background, we hypothesized that GERD and tinnitus might be associated because the middle ear and pharynx are anatomically linked to each other by the Eustachian tube13. Few studies show this linkage, reporting that GERD is closely associated with otologic symptoms13–15. However, research based on the nation-wide population demonstrating the association between GERD and tinnitus is still lacking. To unveil this association, a retrospective cohort study of 669,159 patients was performed, registered in the National Health Insurance Service-National Sample Cohort (NHIS-NSC, 2012–2019) in South Korea. Furthermore, we assessed the efficacy of proton pump inhibitor (PPI), the primary treatment for GERD, in relation to the onset of tinnitus among GERD patients.

Methods

Data source

This study used cohort data from the Korean Nationwide Cohort Database, the NHIS-NSC 2.2 (2002–2019) based on the approval of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Ajou University Hospital (AJOUIRB-EX-2023-146). Based on the national population of health insurance enrollees and medical benefit recipients for one year as of 2006, a sample of 1 million people, representing 2% of the population, was stratified by age group, sex, participant’s eligibility status, income level, and region16. The database included information on participants’ insurance eligibility, treatment, medical care institutions, and general health examinations from 2002 to 201916.

Study design for primary analysis

We conducted a nationwide population-based cohort study. Figure S1 illustrates the research design and the definition of the timeframe. The study cohort was composed of patients who were newly diagnosed with GERD, which was defined based on diagnosis code K21 and its subcodes in the 10th edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) (Table S1). This definition was previously validated in the National Health Insurance claim database, demonstrating a diagnostic accuracy of 74%17. The comparative cohort included patients without a diagnosis of GERD from 2002 to 2019. The time after GERD diagnosis was classified as exposed person-time, and the time from cohort entry to GERD diagnosis was classified as unexposed person-time18. In this study, we defined the person-time exposed to GERD as a GERD group, and all unexposed time prior to GERD diagnosis in the study cohort and throughout the comparative cohort as a non-GERD group (Figure S2). The base cohort entry date was set as January 1, 2003, to ensure a minimum observation period of one year. The index date for the GERD group was established at the initial diagnosis of GERD, while the non-GERD group used the cohort entry date as the index date. Patients aged 18 and above at the index date were included in the study. The outcome measured was the incidence of tinnitus, defined by the ICD-10 diagnosis code H93.1 (Table S1). Subjects were excluded if they had (1) a diagnosis of tinnitus or GERD in 2002 or (2) a diagnosis of tinnitus or died before GERD diagnosis. Patients were followed from the index date until the diagnosis of tinnitus, death, or December 31, 2019, whichever came first. The design of the primary analysis adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines and the REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely collected health Data (RECORD) guidelines19,20.

Study design for secondary analysis

For the secondary analysis, the base cohort consisted of the study cohort from the primary study, defined as patients who received their initial diagnosis of GERD between January 1, 2003, and December 31, 2019, and were aged 18 or older at the time of diagnosis. In this base cohort, all patients with a record of PPI use after the diagnosis of GERD, at least once, were classified as the study cohort, while those without any record of PPI use in their entire medical history were defined as the comparative cohort. Assuming that the risk of tinnitus might change concurrently with the initiation of PPI treatment, the exposed person-time for PPI users was calculated from the time of PPI prescription. The time from cohort entry to PPI diagnosis was classified as unexposed person-time18. We categorize person-time with exposure to PPI as the PPI group, and all the person-time without PPI exposure before the PPI prescription in the study cohort and throughout the comparative cohort as the non-PPI group (Figure S2). The base cohort entry date was defined as the date of the first GERD diagnosis. The index date was set as the first prescription date for the PPI group and the cohort entry date for the non-PPI group. The outcome was referred from the primary analysis, focusing on the diagnosis of tinnitus. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients diagnosed with tinnitus, prescribed PPIs, or with records of death or GERD diagnosis in 2002, (2) patients receiving a diagnosis of tinnitus, those taking PPIs, or those who died before GERD diagnosis, and (3) for the study cohort, those diagnosed with tinnitus or deceased before PPI use. Patients were followed from the index date until the diagnosis of tinnitus, death, or December 31, 2019, whichever occurred first. The research design and the definition of the timeframe of the secondary analysis are illustrated in Figure S3. The secondary analysis adhered to the STROBE guidelines and the RECORD statement for pharmacoepidemiology (RECORD-PE) guidelines19,21.

Covariates

In the primary analysis, baseline covariates included age and sex at the index date. Additionally, income level, comorbidities such as gastritis, gastric cancer, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, hypertension, dyslipidemia, insomnia, vertigo, and hearing loss, as well as medications (PPIs, H2RAs, antidepressants, benzodiazepines, calcium channel blockers (CCBs), Ginkgo biloba, steroids), the number of gastroendoscopies and visits, and the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) were assessed within the 365 days before the index date. In the secondary analysis, the same covariates as the primary analysis were considered. However, because PPI use prior to the index date was an exclusion criterion, PPI use was excluded from the covariates. Model 1 was defined as the analysis excluding medication from the covariates, and Model 2 was defined as the analysis including medication in the covariates. The diagnostic and procedural codes used in the study can be found in Table S1.

Statistical analysis

To depict the characteristics of subjects at cohort entry, descriptive statistics were employed. The 1000 person-years frequency and incidence rates of tinnitus were summarized for each covariate. To estimate the hazard ratio (HR), both univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards model analyses were performed, each with a corresponding 95% confidence interval. Unadjusted tinnitus incidence was measured using the Kaplan–Meier method, and comparisons between the study and control groups were conducted using the log-rank test. The covariates used for adjustment in the multivariate model included those mentioned earlier in both primary and secondary analyses. All statistical analyses were carried out using SAS V.8.3 (SAS Institute) and R software V.4.3.0. A two-tailed p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. As a result of the NHIS-NSC 2.2 structure, none of the variables examined in this study contain any missing data. To validate the research findings, sensitivity analyses were additionally performed, which included incorporating lag times of 180, 365, and 730 days, and setting the outcome as a second diagnosis of tinnitus.

Results

Association between GERD and tinnitus

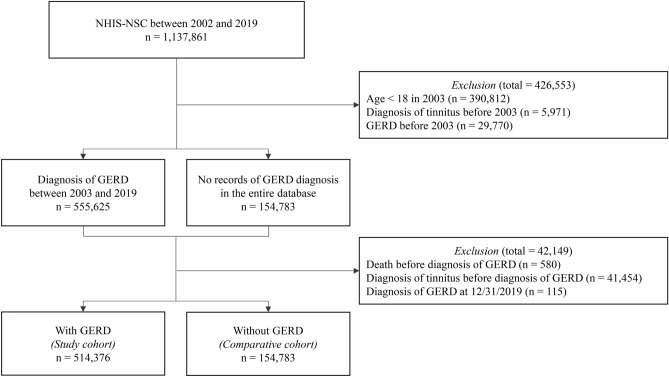

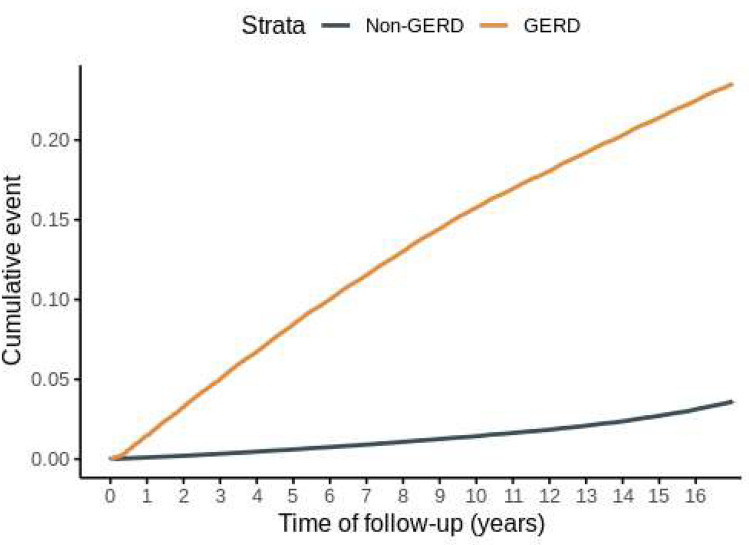

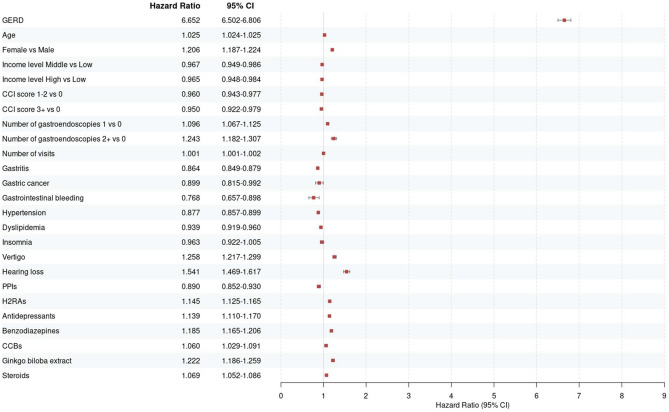

In the NHIS-NSC2 cohort of 1,137,861 patients, we selected the GERD group of 514,376 patients who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria, while the non-GERD group of 669,144 patients was analyzed (Fig. 1). Baseline characteristics of the patient cohort are presented in Table 1. During the follow-up period, 60,253 individuals in the GERD group and 11,367 individuals in the non-GERD group were diagnosed with tinnitus (GERD vs non-GERD; incidence rate 14.91 vs 1.74 cases per 1000 person-years; crude HR (cHR) 8.32, 95% CI 8.12–8.52). The adjusted HR (aHR) accounting for age, sex, income, number of gastroendoscopies and visits, comorbidities, and CCI score was 7.15 (95% CI, 6.99–7.32). Additionally, when adjusting for medications one year before the index date, the aHR remained similarly strong at 6.65, indicating a robust association between GERD and tinnitus (95% CI, 6.50–6.81) (Table 2). The Kaplan–Meier curve comparing the two groups also showed a significantly higher occurrence of tinnitus in the GERD group (p value for log-rank test ≤ 0.0001) (Fig. 2). To further validate the association between GERD and tinnitus, sensitivity analysis was performed (Table 3). The HR for tinnitus occurrence after 180-, 365-, and 730-days following GERD diagnosis, as well as for the occurrence of tinnitus with 2 diagnoses, closely aligned with the results of the primary analysis in GERD patients. Notably, the HR ranged from 4.01 in the full aHR with a 730-day lag to 10.28 in the cHR for the occurrence of tinnitus with 2 diagnoses, showing consistency with the primary analysis. The influence of covariates included in the primary analysis on tinnitus onset, as determined by univariate and multivariate Cox regression, is illustrated in Fig. 3 and S4-5.

Fig. 1.

A flowchart of the primary analysis. A flow chart illustrates the overall process of primary analysis before and after applying inclusion and exclusion criteria. GERD: Gastroesophageal reflux disease. National Health Insurance Service-National Sample Cohort (NHIS-NSC).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients according to GERD exposure.

| Baseline characteristic | GERD | p value | SMD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unexposed (n = 669,144) | Exposed (n = 514,376) | ||||

| Tinnitus (%) | No | 657,777 (98.3) | 454,123 (88.3) | < 0.001 | 0.409 |

| Yes | 11,367 (1.7) | 60,253 (11.7) | |||

| Age (years) (mean (SD)) | 40.35 (14.79) | 40.74 (14.47) | < 0.001 | 0.027 | |

| Age (years) (%) | < 40 | 351,468 (52.5) | 259,403 (50.4) | < 0.001 | 0.048 |

| 40–59 | 230,582 (34.5) | 189,015 (36.7) | |||

| 60 + | 87,094 (13.0) | 65,958 (12.8) | |||

| Sex (%) | Male | 338,206 (50.5) | 246,424 (47.9) | < 0.001 | 0.053 |

| Female | 330,938 (49.5) | 267,952 (52.1) | |||

| Income level (%) | Low | 178,924 (26.7) | 132,277 (25.7) | < 0.001 | 0.049 |

| Middle | 257,745 (38.5) | 191,186 (37.2) | |||

| High | 232,475 (34.7) | 190,913 (37.1) | |||

| CCI score (%) | 0 | 385,830 (57.7) | 250,527 (48.7) | < 0.001 | 0.181 |

| 1–2 | 227,097 (33.9) | 209,479 (40.7) | |||

| 3 + | 56,217 (8.4) | 54,370 (10.6) | |||

| Number of visits (mean (SD)) | 14.04 (17.46) | 17.41 (18.47) | < 0.001 | 0.187 | |

| Number of gastroendoscopies (%) | 0 | 619,187 (92.5) | 466,495 (90.7) | < 0.001 | 0.067 |

| 1 | 41,998 (6.3) | 40,025 (7.8) | |||

| 2 + | 7959 (1.2) | 7856 (1.5) | |||

| Gastritis (%) | None | 306,620 (45.8) | 169,780 (33.0) | < 0.001 | 0.265 |

| Present | 362,524 (54.2) | 344,596 (67.0) | |||

| Gastric cancer (%) | None | 666,153 (99.6) | 511,525 (99.4) | < 0.001 | 0.015 |

| Present | 2991 (0.4) | 2851 (0.6) | |||

| Gastrointestinal bleeding (%) | None | 667,570 (99.8) | 512,852 (99.7) | < 0.001 | 0.012 |

| Present | 1574 (0.2) | 1524 (0.3) | |||

| Hypertension (%) | None | 549,590 (82.1) | 403,640 (78.5) | < 0.001 | 0.092 |

| Present | 119,554 (17.9) | 110,736 (21.5) | |||

| Dyslipidemia (%) | None | 571,037 (85.3) | 419,399 (81.5) | < 0.001 | 0.102 |

| Present | 98,107 (14.7) | 94,977 (18.5) | |||

| Insomnia (%) | None | 654,789 (97.9) | 500,454 (97.3) | < 0.001 | 0.036 |

| Present | 14,355 (2.1) | 13,922 (2.7) | |||

| Vertigo (%) | None | 647,780 (96.8) | 493,772 (96.0) | < 0.001 | 0.044 |

| Present | 21,364 (3.2) | 20,604 (4.0) | |||

| Hearing loss (%) | None | 661,479 (98.9) | 507,127 (98.6) | < 0.001 | 0.023 |

| Present | 7665 (1.1) | 7249 (1.4) | |||

| PPIs (%) | None | 653,336 (97.6) | 499,061 (97.0) | < 0.001 | 0.038 |

| Present | 15,808 (2.4) | 15,315 (3.0) | |||

| H2RAs (%) | None | 431,644 (64.5) | 299,997 (58.3) | < 0.001 | 0.127 |

| Present | 237,500 (35.5) | 214,379 (41.7) | |||

| Antidepressants (%) | None | 632,000 (94.4) | 479,568 (93.2) | < 0.001 | 0.051 |

| Present | 37,144 (5.6) | 34,808 (6.8) | |||

| Benzodiazepines (%) | None | 511,151 (76.4) | 369,833 (71.9) | < 0.001 | 0.103 |

| Present | 157,993 (23.6) | 144,543 (28.1) | |||

| Calcium channel blockers (%) | None | 625,243 (93.4) | 475,143 (92.4) | < 0.001 | 0.042 |

| Present | 43,901 (6.6) | 39,233 (7.6) | |||

| Ginkgo biloba extract (%) | None | 646,360 (96.6) | 493,473 (95.9) | < 0.001 | 0.035 |

| Present | 22,784 (3.4) | 20,903 (4.1) | |||

| Steroids (%) | None | 376,893 (56.3) | 253,414 (49.3) | < 0.001 | 0.142 |

| Present | 292,251 (43.7) | 260,962 (50.7) | |||

CCI: Charlson comorbidity index; GERD: gastroesophageal reflux disease; H2RA: H2 receptor antagonist; PPI: proton pump inhibitor; SD: standard deviation; SMD: standardized mean difference.

Table 2.

Incidence and hazard ratios of tinnitus among patients according to GERD exposure.

| GERD diagnosis | Person-years | No. of cases | Incidence rate (per 1,000 person-years) | HR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude HR | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||

| Unexposed | 6,535,305 | 11,367 | 1.74 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| GERD | 4,039,581 | 60,253 | 14.92 | 8.32 (8.12, 8.52) | 7.15 (6.99, 7.32) | 6.65 (6.50, 6.81) |

| p value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||

Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex, income level, number of gastroendoscopies and visits, comorbidities (gastritis, gastric cancer, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, hypertension, dyslipidemia, insomnia, vertigo, hearing loss) and Charlson Comorbidity Index score in the 365 days before the index date. Model 2 was adjusted for age, sex, income level, number of gastroendoscopies and visits, comorbidities (gastritis, gastric cancer, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, hypertension, dyslipidemia, insomnia, vertigo, hearing loss), and medications (PPIs, H2RAs, antidepressants, benzodiazepines, calcium channel blockers, Ginkgo biloba, steroids), and Charlson Comorbidity Index score in the 365 days before the index date. CI: confidence interval; GERD: gastroesophageal reflux disease; H2RA: H2 receptor antagonist; HR: hazard ratio; PPI: proton pump inhibitor.

Fig. 2.

The cumulative incidence of tinnitus in patients with or without GERD. A Kaplan–Meier curve illustrates the cumulative incidence of tinnitus in patients with or without GERD. GERD: Gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Table 3.

Sensitivity analysis of tinnitus among patients according to GERD exposure.

| GERD diagnosis | HR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Crude HR | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| Lag 180 d | |||

| Unexposed | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| GERD | 7.25 (7.08, 7.42) | 6.23 (6.09, 6.37) | 5.74 (5.61, 5.88) |

| p value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Lag 365 d | |||

| Unexposed | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| GERD | 6.43 (6.28, 6.58) | 5.53 (5.41, 5.66) | 5.05 (4.94, 5.17) |

| p value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Lag 730 d | |||

| Unexposed | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| GERD | 5.15 (5.03, 5.28) | 4.45 (4.35, 4.55) | 4.01 (3.92, 4.10) |

| p value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Diagnosis twice | |||

| Unexposed | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| GERD | 10.28 (9.95, 10.62) | 8.44 (8.17, 8.72) | 7.76 (7.50, 8.02) |

| p value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex, income level, number of gastroendoscopies and visits, comorbidities (gastritis, gastric cancer, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, hypertension, dyslipidemia, insomnia, vertigo, hearing loss) and Charlson Comorbidity Index score in the 365 days before the index date. Model 2 was adjusted for age, sex, income level, number of gastroendoscopies and visits, comorbidities (gastritis, gastric cancer, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, hypertension, dyslipidemia, insomnia, vertigo, hearing loss), and medications (PPIs, H2RAs, antidepressants, benzodiazepines, calcium channel blockers, Ginkgo biloba, steroids), and Charlson Comorbidity Index score in the 365 days before the index date. CI: confidence interval; GERD: gastroesophageal reflux disease; H2RA: H2 receptor antagonist; HR: hazard ratio; PPI: proton pump inhibitor.

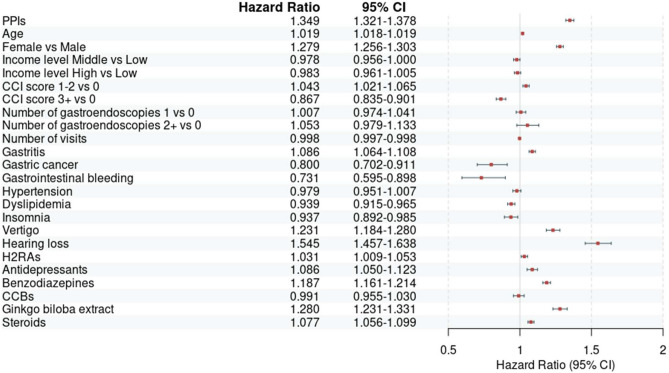

Fig. 3.

Forest plots from primary analysis using multivariate Cox regression (model 2). CCB: calcium channel blocker; CCI: Charlson Comorbidity Index; CI: confidence interval; GERD: gastroesophageal reflux disease; H2RA: H2 receptor antagonist; PPI: proton pump inhibitor.

Association between PPI medication and tinnitus onset among GERD patients

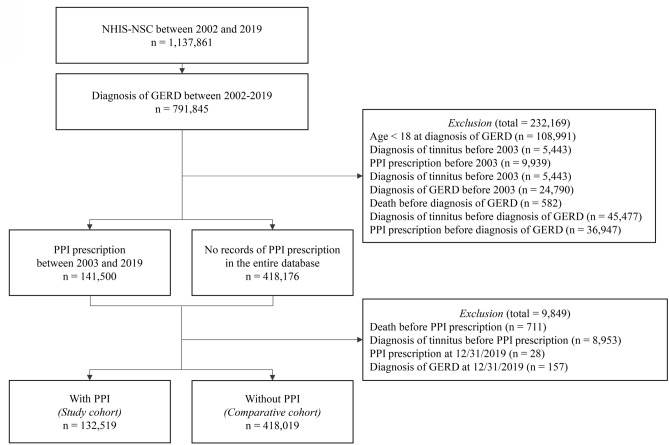

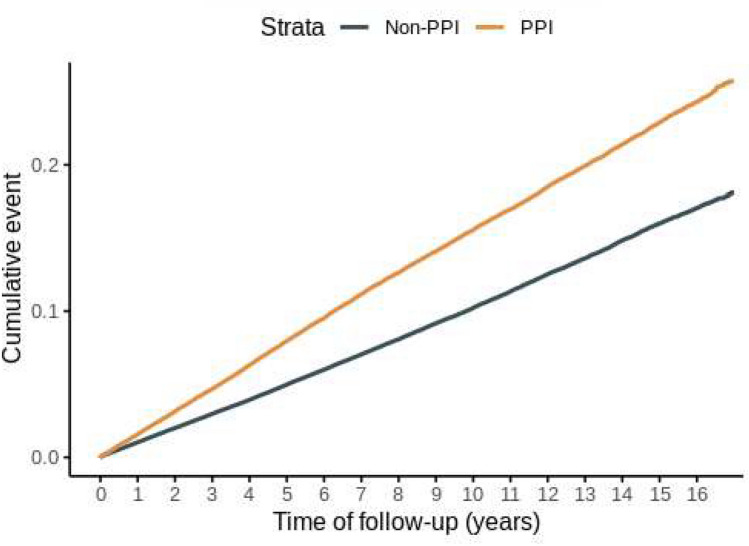

A total of 132,519 patients meeting the selection criteria for GERD diagnosis and exclusion criteria were included in the PPI group, while 502,521 patients were included in the non-PPI group (Fig. 4). The baseline characteristics of the GERD patients are presented in Table 4. During the follow-up period, 15,333 cases of tinnitus occurred in the PPI-exposed time, while 34,767 cases occurred in the PPI non-exposed time (PPI vs. non-PPI; incidence rate 17.22 vs. 10.80 cases per 1000 person-years; cHR 1.54, 95% CI 1.51–1.57). In the multivariate Cox analysis, adjusting for covariates including both non-drug and drug-related factors based on the index date, PPI use remained significantly associated with an increased risk of tinnitus (Model 1 aHR 1.40, 95% CI 1.38–1.43; Model 2 aHR 1.35, 95% CI 1.32–1.38) (Table 5). The Kaplan–Meier curve comparing the two groups also demonstrated a significantly higher incidence in the PPI group (p value for log-rank test ≤ 0.0001) (Fig. 5). The sensitivity analysis showed consistent results with secondary analysis (Table 6). The HRs for the occurrence of tinnitus after 180, 365, and 730 days of PPI use, as well as the occurrence of tinnitus with two diagnoses, closely aligned with the results of the secondary analysis. The HR for tinnitus ranged from 1.12 in the fully aHR with a 730-day lag to 1.62 in the cHR for two tinnitus diagnoses. The impact of covariates included in the secondary analysis on the onset of tinnitus, as determined through univariate and multivariate Cox regression, is depicted in Fig. 6 and S6–7.

Fig. 4.

A flowchart of the secondary analysis. A flow chart illustrates the overall process of secondary analysis before and after applying inclusion and exclusion criteria. GERD: Gastroesophageal reflux disease; National Health Insurance Service-National Sample Cohort (NHIS-NSC); PPI: Proton pump inhibitor.

Table 4.

Baseline characteristics of patients with GERD according to PPI exposure.

| Baseline characteristic | PPI | p value | SMD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unexposed (n = 502,521) | Exposed (n = 132,519) | ||||

| Tinnitus (%) | No | 467,754 (93.1) | 117,186 (88.4) | < 0.001 | 0.161 |

| Yes | 34,767 (6.9) | 15,333 (11.6) | |||

| Age (years) (mean (SD)) | 43.53 (15.81) | 49.18 (16.23) | < 0.001 | 0.352 | |

| Age (years) (%) | < 40 | 218,591 (43.5) | 39,324 (29.7) | < 0.001 | 0.329 |

| 40–59 | 197,712 (39.3) | 56,291 (42.5) | |||

| 60 + | 86,218 (17.2) | 36,904 (27.8) | |||

| Sex (%) | Male | 234,336 (46.6) | 64,732 (48.8) | < 0.001 | 0.044 |

| Female | 268,185 (53.4) | 67,787 (51.2) | |||

| Income level (%) | Low | 131,683 (26.2) | 36,527 (27.6) | < 0.001 | 0.052 |

| Middle | 188,549 (37.5) | 46,416 (35.0) | |||

| High | 182,289 (36.3) | 49,576 (37.4) | |||

| CCI score (%) | 0 | 293,587 (58.4) | 46,068 (34.8) | < 0.001 | 0.537 |

| 1–2 | 166,452 (33.1) | 57,030 (43.0) | |||

| 3 + | 42,482 (8.5) | 29,421 (22.2) | |||

| Number of visits (mean (SD)) | 15.13 (21.97) | 27.92 (33.72) | < 0.001 | 0.449 | |

| Number of gastroendoscopies (%) | 0 | 470,720 (93.7) | 110,543 (83.4) | < 0.001 | 0.328 |

| 1 | 27,205 (5.4) | 17,789 (13.4) | |||

| 2 + | 4596 (0.9) | 4187 (3.2) | |||

| Gastritis (%) | None | 174,427 (34.7) | 30,976 (23.4) | < 0.001 | 0.252 |

| Present | 328,094 (65.3) | 101,543 (76.6) | |||

| Gastric cancer (%) | None | 500,060 (99.5) | 130,507 (98.5) | < 0.001 | 0.103 |

| Present | 2461 (0.5) | 2012 (1.5) | |||

| Gastrointestinal bleeding (%) | None | 501,502 (99.8) | 131,819 (99.5) | < 0.001 | 0.054 |

| Present | 1019 (0.2) | 700 (0.5) | |||

| Hypertension (%) | None | 412,625 (82.1) | 91,094 (68.7) | < 0.001 | 0.314 |

| Present | 89,896 (17.9) | 41,425 (31.3) | |||

| Dyslipidemia (%) | None | 415,316 (82.6) | 91,551 (69.1) | < 0.001 | 0.321 |

| Present | 87,205 (17.4) | 40,968 (30.9) | |||

| Insomnia (%) | None | 489,075 (97.3) | 124,328 (93.8) | < 0.001 | 0.171 |

| Present | 13,446 (2.7) | 8191 (6.2) | |||

| Vertigo (%) | None | 483,497 (96.2) | 122,730 (92.6) | < 0.001 | 0.157 |

| Present | 19,024 (3.8) | 9789 (7.4) | |||

| Hearing loss (%) | None | 496,368 (98.8) | 129,435 (97.7) | < 0.001 | 0.084 |

| Present | 6153 (1.2) | 3084 (2.3) | |||

| H2RAs (%) | None | 389,164 (77.4) | 66,343 (50.1) | < 0.001 | 0.594 |

| Present | 113,357 (22.6) | 66,176 (49.9) | |||

| Antidepressants (%) | None | 477,063 (94.9) | 116,364 (87.8) | < 0.001 | 0.256 |

| Present | 25,458 (5.1) | 16,155 (12.2) | |||

| Benzodiazepines (%) | None | 420,142 (83.6) | 87,667 (66.2) | < 0.001 | 0.411 |

| Present | 82,379 (16.4) | 44,852 (33.8) | |||

| Calcium channel blockers (%) | None | 480,807 (95.7) | 116,677 (88.0) | < 0.001 | 0.282 |

| Present | 21,714 (4.3) | 15,842 (12.0) | |||

| Ginkgo biloba extract (%) | None | 491,662 (97.8) | 124,583 (94.0) | < 0.001 | 0.195 |

| Present | 10,859 (2.2) | 7936 (6.0) | |||

| Steroids (%) | None | 339,593 (67.6) | 63,860 (48.2) | < 0.001 | 0.4 |

| Present | 162,928 (32.4) | 68,659 (51.8) | |||

CCI: Charlson comorbidity index; GERD: gastroesophageal reflux disease; H2RA: H2 receptor antagonist; PPI: proton pump inhibitor; SMD: standardized mean difference.

Table 5.

Incidence and hazard ratios of tinnitus among patients with GERD according to PPI exposure.

| PPI exposure | Person-years | No. of cases | Incidence rate (per 1,000 person-years) | HR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude HR | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||

| Unexposed | 3,219,513 | 34,767 | 10.80 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Exposed | 890,626.3 | 15,333 | 17.22 | 1.54 (1.51,1.57) | 1.40 (1.38, 1.43) | 1.35 (1.32, 1.38) |

| p value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||

Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex, income level, number of gastroendoscopies and visits, comorbidities (gastritis, gastric cancer, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, hypertension, dyslipidemia, insomnia, vertigo, hearing loss) and Charlson Comorbidity Index score in the 365 days before the index date. Model 2 was adjusted for age, sex, income level, number of gastroendoscopies and visits, comorbidities (gastritis, gastric cancer, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, hypertension, dyslipidemia, insomnia, vertigo, hearing loss), and medications (H2RAs, antidepressants, benzodiazepines, calcium channel blockers, Ginkgo biloba, steroids), and Charlson Comorbidity Index score in the 365 days before the index date. CI: confidence interval; H2RA: H2 receptor antagonist; HR: hazard ratio; PPI: proton pump inhibitor.

Fig. 5.

The cumulative incidence of tinnitus in patients with or without PPIs. A Kaplan–Meier curve illustrates the cumulative incidence of tinnitus in patients with or without PPIs. PPI: proton pump inhibitor.

Table 6.

Sensitivity analysis for secondary analysis.

| PPI exposure | HR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Crude HR | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| Lag 180 d | |||

| Unexposed | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Exposed | 1.45 (1.42, 1.48) | 1.32 (1.30, 1.35) | 1.27 (1.24, 1.29) |

| p value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Lag 365 d | |||

| Unexposed | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Exposed | 1.38 (1.35, 1.41) | 1.27 (1.25, 1.30) | 1.21 (1.19, 1.24) |

| p value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Lag 730 d | |||

| Unexposed | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Exposed | 1.27 (1.24, 1.30) | 1.18 (1.15, 1.20) | 1.12 (1.09, 1.15) |

| p value | < 0.001 | 0.868 | < 0.001 |

| Diagnosis twice | |||

| Unexposed | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Exposed | 1.62 (1.58, 1.66) | 1.41 (1.38, 1.45) | 1.35 (1.31, 1.38) |

| p value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex, income level, number of gastroendoscopies and visits, comorbidities (gastritis, gastric cancer, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, hypertension, dyslipidemia, insomnia, vertigo, hearing loss) and Charlson Comorbidity Index score in the 365 days before the index date. Model 2 was adjusted for age, sex, income level, number of gastroendoscopies and visits, comorbidities (gastritis, gastric cancer, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, hypertension, dyslipidemia, insomnia, vertigo, hearing loss), and medications (H2RAs, antidepressants, benzodiazepines, calcium channel blockers, Ginkgo biloba, steroids), and Charlson Comorbidity Index score in the 365 days before the index date. CI: confidence interval; H2RA: H2 receptor antagonist; HR: hazard ratio; PPI: proton pump inhibitor.

Fig. 6.

Forest plots from secondary analysis using multivariate Cox regression (model 2). CCB: calcium channel blocker; CCI: Charlson Comorbidity Index; CI: confidence interval; H2RA: H2 receptor antagonist; PPI: proton pump inhibitor.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first and the largest national population-based cohort study aimed to explore the association between GERD and tinnitus, which encompasses data from 669,159 patients over 17 years. We also used national claim data that spans across all insured practices in Korea, including continuous medical visit data from virtually all hospitals within South Korea. Additionally, we used time-varying cox model to account for unexposed periods. Moreover, we performed vast array of sensitivity analysis, including a diverse range of lag times to ensure the reliability of our findings across various scenarios.

In this study, after adjusting for covariates, GERD patients had a 6.65 times higher risk of developing tinnitus compared to non-GERD patients. Previous research has raised the possibility of an association between GERD and otologic conditions. Although there are not many studies specifically focusing on the association between GERD and tinnitus, a significant body of research has indicated a strong link between GERD and conditions related to otologic disorders including hearing loss13, chronic otitis media14 and peripheral vertigo15. These studies consistently indicate an elevated risk of such disorders in presence of GERD. Considering this evidence, our study findings showing association in increase of risk on occurrence of tinnitus in patients with GERD (Table 2) may corroborate the existing literature, suggesting that acid reflux could potentially impact a range of otologic diseases. This association can be partially explained by mechanisms wherein gastric acid reflux adversely influences middle and inner ear, as demonstrated in experimental animal models8,9. Furthermore, elevated pepsinogen and Helicobacter pylori in middle ear fluid, along with the detection of pepsin across multiple studies, provide additional support for the role of laryngopharyngeal reflux in the development of otological conditions22,23. These studies may implicate the potential of gastric content influencing the cause or maintenance of the tinnitus which has strong links with hearing loss.

The causes of tinnitus can vary based on the risk factors present in individuals; specific diseases or conditions meet this criterion10,12. For instance, infectious and autoimmune diseases that can trigger inflammation, like otitis media, mastoiditis, and systemic lupus erythematosus, may lead to tinnitus10,24,25. Additionally, neoplastic diseases such as vestibular schwannoma and traumatic injuries also can contribute to the onset of tinnitus10,26. While the causes may differ, the pathophysiological mechanisms generally fall into two main categories: cochlear abnormality and neural modulation of the central auditory system10,27. The precise pathways remain elusive; however, it is hypothesized that cochlear abnormalities may initiate the tinnitus process, with subsequent neural modulation acting to sustain the condition10. Persistent exposure to risk factors may lead to enduring neuronal modulation, thereby maintaining tinnitus even in the absence of cochlear nerve function10,28. This may implicate that early intervention in the tinnitus cascade maybe pivotal for effective management and control9. In our study, GERD was associated with higher risk of having tinnitus, which may suggest that gastric content reflux to the middle and inner ear may act as a critical initiating factor in the development of tinnitus.

In this context, we investigated the association between the risk of tinnitus and the use of PPI, the first treatment of choice of GERD. However, our results showed that the use of PPIs is associated with an increased risk of tinnitus, rather than reducing it. Our result is in line with previous study showing the PPI medication is associated with tinnitus onset in type 2 diabetes patients29. Although the mechanism is still unknown, the possible mechanism is that PPI may directly act to inner ear physiology by inhibiting H, K-ATPase in the lateral wall of cochlear29. Considering PPI can affect cardiovascular system, PPI may affect the circulation defect of the cochlea and lead to tinnitus onset29,30. Aside from the possible effects on cochlear physiology and circulation, there are other potential mechanisms by which PPIs could contribute to the increased risk of tinnitus. One possibility is that long-term PPI use may lead to hypomagnesemia31, a known side effect of the medication. Magnesium plays an essential role in auditory function, and its deficiency has been linked to tinnitus and hearing loss32. It is noteworthy that gastroesophageal reflux can be both acidic and alkaline in nature33. If alkaline reflux is present, PPIs may not fully alleviate symptoms. This could explain the lack of improvement in tinnitus symptoms in GERD patients taking PPIs, as the medication may be insufficient in addressing non-acidic reflux that continues to affect the middle and inner ear. Once the auditory structures have been compromised, whether by acid or alkaline reflux, subsequent interventions may not be able to reverse the damage, explaining why tinnitus persists despite PPI treatment. In other comorbid otologic diseases with GERD, the effect of PPI and H2RA on otologic symptoms are still controversial. In Nurses’ Health Study II, there is no relation between PPI use or H2RA use and hearing loss after GERD onset13. However, anti-reflux precautions and treatment on children both with GERD and otitis media significantly improved the otitis media symptoms, such as middle ear effusion and hearing loss34. Hence, the impact of PPIs on otologic symptoms in GERD patients remains controversial, emphasizing the need for cautious application of PPIs to mitigate otologic symptoms.

In this study, we observed that hearing loss, a covariate in both our primary and secondary analyses, is associated with the onset of tinnitus. Considering tinnitus and hearing loss are highly associated each other35, it is highly suggested that a potential association between GERD and hearing loss as well. Additionally, a cohort from the Nurses’ Health Study II showed that GERD symptoms are highly associated with hearing loss in the American female population13. Therefore, investigating the association between GERD and hearing loss in the East Asian population will be the focus of our future research.

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, as a retrospective observational study utilizing health claim data, there might be unmeasured covariates, and the severity of GERD-related diseases or diagnostic results may be challenging to ascertain. To address this, we included the frequency of gastrointestinal endoscopies as a covariate in baseline characteristics. Secondly, depression and anxiety disorders are major risk factors for tinnitus36, but mental health-related codes in this database are often masked, making it challenging to identify them. To overcome this, we used antidepressants and benzodiazepines as covariates for matching or adjustment36. Additionally, since the primary analysis compared the non-disease group and the secondary analysis compared the non-drug use group, surveillance bias, differences in severity, and variations in health-seeking behavior could potentially influence the results. To minimize surveillance bias and differences in disease severity37, we included the count of gastroendoscopies as a covariate. To address variations in health-seeking behavior, we also included the number of physician visits as a covariate to mitigate potential limitations. Lastly, detailed hearing-related data, such as tone audiogram results, were not available in our dataset. This absence may hinder a thorough elucidation of the potential impact of GERD on the development of tinnitus.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

Conceptualization: S.W.K., M.H.A., S.S.P.; Methodology: S.W.K., M.H.A., S.H., K.S., M.G.K., H.K.K., R.W.P.; Investigation: S.W.K., M.H.A., S.S.P.; Visualization: S.W.K., M.H.A.; Funding acquisition: S.S.P., T.J.P.; Project administration: S.S.P.; Supervision: R.W.P., T.J.P.; Writing—original draft: S.W.K., M.H.A., S.S.P.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the National Research Foundation of Korea awarded to Tae Jun Park (NRF-2019R1A2C2086127, NRF-2020R1A6A1A03043539, and NRF-2020M3A9D8037604). Additional support was provided by a grant from the Korean Health Technology R&D Project awarded to Rae Woong Park (HR16C0001) and Soon Sang Park (RS- 2024-00406134), as well as a grant for the MD-PhD/Medical Scientist Training Program awarded to Min Ho An (funding number not applicable) through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare. This study also received funding from the Physician Scientist Training Program of Ajou University Hospital, supporting Soon Sang Park and Min Ho An (funding number not applicable).

Data availability

This study used cohort data from the Korean Nationwide Cohort Database, the NHIS-NSC 2.2. The NHIS-NSC 2.2 database requires a completed application form, a research proposal, and the institutional review board’s approval document.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The retrospective cohort study was conducted under an informed consent waiver approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Ajou University Hospital (AJOUIRB-EX-2023–146).

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Sung-Woo Kang and Min Ho An.

These authors jointly supervised this work: Rae Woong Park and Soon Sang Park.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-81658-7.

References

- 1.Fass, R. Gastroesophageal reflux disease. N. Engl. J. Med.387, 1207–1216 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dickson, I. Increasing global burden of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.17, 260. 10.1038/s41572-021-00287-w (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maret-Ouda, J., Markar, S. R. & Lagergren, J. Gastroesophageal reflux disease: A review. JAMA324, 2536–2547. 10.1001/jama.2020.21360 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eusebi, L. H. et al. Global prevalence of, and risk factors for, gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms: A meta-analysis. Gut67, 430–440. 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313589 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richter, J. E. & Rubenstein, J. H. Presentation and epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterol154, 267–276. 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.07.045 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanabe, T. & Oridate, N. Chronic pharyngitis and laryngitis caused by gastroesophageal reflux. Nihon Rinsho74, 1367–1371 (2016). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qua, C. S., Wong, C. H., Gopala, K. & Goh, K. L. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in chronic laryngitis: Prevalence and response to acid-suppressive therapy. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther.25, 287–295. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03185.x (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Develioglu, O. N., Yilmaz, M., Caglar, E., Topak, M. & Kulekci, M. Oto-toxic effect of gastric reflux. J. Craniofac. Surg.24, 640–644. 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31827c7dad (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basoglu, M. S. et al. Increased expression of VEGF, iNOS, IL-1beta, and IL-17 in a rabbit model of gastric content-induced middle ear inflammation. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol.76, 64–69. 10.1016/j.ijporl.2011.10.001 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baguley, D., McFerran, D. & Hall, D. Tinnitus. Lancet382, 1600–1607. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60142-7 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jarach, C. M. et al. Global prevalence and incidence of tinnitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol.79, 888–900. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.2189 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han, B. I., Lee, H. W., Kim, T. Y., Lim, J. S. & Shin, K. S. Tinnitus: characteristics, causes, mechanisms, and treatments. J. Clin. Neurol.5, 11–19. 10.3988/jcn.2009.5.1.11 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin, B. M. et al. Prospective study of gastroesophageal reflux, use of proton pump inhibitors and H2-receptor antagonists, and risk of hearing loss. Ear Hear.38, 21–27. 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000347 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yeo, C. D., Kim, J. S. & Lee, E. J. Association of gastroesophageal reflux disease with increased risk of chronic otitis media with effusion in adults: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Medicine100, e26940. 10.1097/MD.0000000000026940 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Viliušytė, E., Macaitytė, R., Vaitkus, A. & Rastenytė, D. Associations between peripheral vertigo and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Med. Hypotheses85, 333–335. 10.1016/j.mehy.2015.06.007 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee, J., Lee, J. S., Park, S. H., Shin, S. A. & Kim, K. Cohort profile: The national health insurance service-national sample cohort (NHIS-NSC). South Korea. Int. J. Epidemiol.46, e15. 10.1093/ije/dyv319 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim, K. M. et al. Prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease in Korea and associated health-care utilization: A national population-based study. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.27, 741–745. 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06921.x (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suissa, S. Immortal time bias in pharmacoepidemiology. Am. J. Epidemiol.167, 492–499. 10.1093/aje/kwm324 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elm, V. E. et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet370, 1453–1457. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benchimol, I. E. The REporting of studies conducted using observational routinely-collected health data (RECORD) statement. Plos Med.12, e1001885. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001885 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langan, M. S. et al. The reporting of studies conducted using observational routinely collected health data statement for pharmacoepidemiology (RECORD-PE). BMJ363, k3532. 10.1136/bmj.k3532 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doğru, M., Kuran, G., Haytoğlu, S., Dengiz, R. & Arıkan, O. K. Role of laryngopharyngeal reflux in the pathogenesis of otitis media with effusion. J. Int. Adv. Otol. 42 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Lechien, J. R. et al. Association between laryngopharyngeal reflux and media otitis: A systematic review. Otol. Neurotol.11, 66–71. 10.5152/iao.2015.642 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim, D. K. et al. Tinnitus in patients with chronic otitis media before and after middle ear surgery. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol.268, 1443–1448. 10.1007/s00405-011-1519-9 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aarhus, L., Engdahl, B., Tambs, K., Kvestad, E. & Hoffman, H. J. Association between childhood hearing disorders and tinnitus in adulthood. JAMA Otolaryngol.141, 983–989. 10.1001/jamaoto.2015.2378 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baguley, D. M., Humphriss, R. L., Axon, P. R. & Moffat, D. A. The clinical characteristics of tinnitus in patients with vestibular schwannoma. Skull Base16, 49–58. 10.1055/s-2005-926216 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eggermont, J. J. & Roberts, L. E. The neuroscience of tinnitus. Trends Neurosci.27, 676–682. 10.1016/j.tins.2004.08.010 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.House, J. W. & Brackmann, D. E. Tinnitus: Surgical treatment. Ciba Found. Symp.85, 204–216. 10.1002/9780470720677.ch12 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yee, J., Han, H. W. & Gwak, H. S. Proton pump inhibitor use and hearing loss in patients with type 2 diabetes: Evidence from a hospital‐based case‐control study and a population‐based cohort study. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol.88, 2738–2746. 10.1111/bcp.15210 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Nakashima, T. et al. Disorders of cochlear blood flow. Brain Res. Rev.43, 17–28 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Florentin, M., Elisaf, M. S. & Gwak, H. S. Proton pump inhibitor-induced hypomagnesemia: A new challenge. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol.88, 2738–2746. 10.5527/wjn.v1.i6.151 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cevette, M. J. et al. Phase 2 study examining magnesium-dependent tinnitus. Int. Tinnitus J.1, 168–173 (2011). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nath, B. J. & Warshaw, A. L. Alkaline reflux gastritis and esophagitis. Annu. Rev. Med.35, 383–396. 10.1146/annurev.me.35.020184.002123 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.McCoul, E. D. et al. A prospective study of the effect of gastroesophageal reflux disease treatment on children with otitis media. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg.137, 35–41. 10.1001/archoto.2010.222 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joo, Y. H., Han, K. D. & Park, K. H. Association of hearing loss and tinnitus with health-related quality of life: The Korea national health and nutrition examination survey. PLoS One10, e0131247. 10.1371/journal.pone.0131247 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oosterloo, B. C. et al. Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between tinnitus and mental health in a population-based sample of middle-aged and elderly persons. JAMA Otolaryngol.147, 708–716. 10.1001/jamaoto.2021.1049 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haut, E. R. & Pronovost, P. J. Surveillance bias in outcomes reporting. JAMA305, 2462–2463. 10.1001/jama.2011.822 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This study used cohort data from the Korean Nationwide Cohort Database, the NHIS-NSC 2.2. The NHIS-NSC 2.2 database requires a completed application form, a research proposal, and the institutional review board’s approval document.