Abstract

Background

Email is a popular and commonly‐used method of communication, but its use in health care is not routine. Where email communication has been demonstrated in health care this has included its use for communication between patients/caregivers and healthcare professionals for clinical purposes, but the effects of using email in this way is not known.This review addresses the use of email for two‐way clinical communication between patients/caregivers and healthcare professionals.

Objectives

To assess the effects of healthcare professionals and patients using email to communicate with each other, on patient outcomes, health service performance, service efficiency and acceptability.

Search methods

We searched: the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group Specialised Register, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, The Cochrane Library, Issue 1 2010), MEDLINE (OvidSP) (1950 to January 2010), EMBASE (OvidSP) (1980 to January 2010), PsycINFO (OvidSP) (1967 to January 2010), CINAHL (EbscoHOST) (1982 to February 2010) and ERIC (CSA) (1965 to January 2010). We searched grey literature: theses/dissertation repositories, trials registers and Google Scholar (searched July 2010). We used additional search methods: examining reference lists, contacting authors.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials, quasi‐randomised trials, controlled before and after studies and interrupted time series studies examining interventions using email to allow patients to communicate clinical concerns to a healthcare professional and receive a reply, and taking the form of 1) unsecured email 2) secure email or 3) web messaging. All healthcare professionals, patients and caregivers in all settings were considered.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed the risk of bias of included studies and extracted data. We contacted study authors for additional information. We assessed risk of bias according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. For continuous measures, we report effect sizes as mean differences (MD). For dichotomous outcome measures, we report effect sizes as odds ratios and rate ratios. Where it was not possible to calculate an effect estimate we report mean values for both intervention and control groups and the total number of participants in each group. Where data are available only as median values it is presented as such. It was not possible to carry out any meta‐analysis of the data.

Main results

We included nine trials enrolling 1733 patients; all trials were judged to be at risk of bias. Seven were randomised controlled trials; two were cluster‐randomised controlled designs. Eight examined email as compared to standard methods of communication. One compared email with telephone for the delivery of counselling. When email was compared to standard methods, for the majority of patient/caregiver outcomes it was not possible to adequately assess whether email had any effect. For health service use outcomes it was not possible to adequately assess whether email has any effect on resource use, but some results indicated that an email intervention leads to an increased number of emails and telephone calls being received by healthcare professionals. Three studies reported some type of adverse event but it was not clear if the adverse event had any impact on the health of the patient or the quality of health care. When email counselling was compared to telephone counselling only patient outcomes were measured, and for the majority of measures there was no difference between groups. Where there were differences these showed that telephone counselling leads to greater change in lifestyle modification factors than email counselling. There was one outcome relating to harm, which showed no difference between the email and the telephone counselling groups. There were no primary outcomes relating to healthcare professionals for either comparison.

Authors' conclusions

The evidence base was found to be limited with variable results and missing data, and therefore it was not possible to adequately assess the effect of email for clinical communication between patients/caregivers and healthcare professionals. Recommendations for clinical practice could not be made. Future research should ideally address the issue of missing data and methodological concerns by adhering to published reporting standards. The rapidly changing nature of technology should be taken into account when designing and conducting future studies and barriers to trial development and implementation should also be tackled. Potential outcomes of interest for future research include cost‐effectiveness and health service resource use.

Keywords: Humans, Professional‐Patient Relations, Caregivers, Caregivers/statistics & numerical data, Electronic Mail, Electronic Mail/statistics & numerical data, Health Personnel, Health Personnel/statistics & numerical data, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Telephone, Telephone/statistics & numerical data

Plain language summary

Using email for patients/caregivers and healthcare professionals to contact each other

Email is widely used in many sectors and lots of people use it in their day to day lives. The use of email in health care is not yet so common, although one use for it is for patients/caregivers and healthcare professionals to contact each other. This review examines how patients, healthcare professionals and health services may be affected by using email in this way. We looked for trials examining the use of email for patients/caregivers and healthcare professionals to contact each other and found nine trials with 1733 participants in total.

Eight of the trials looked at email compared with standard methods of communication. Where email was compared to standard methods of communication we found that we could not properly determine what effect email was having on patient/caregiver outcomes, as there were missing data and the results of the different studies varied. For health service use outcomes the situation was the same, but some results seemed to show that an email intervention may lead to an increased number of emails and telephone calls being received by healthcare professionals.

One of the trials looked at email counselling compared with telephone counselling. We found that it only looked at patient outcomes, and found few differences between groups. Where there were differences these showed that telephone counselling leads to greater changes in lifestyle than email counselling.

None of the trials measured how email affects healthcare professionals and only one measured whether email can cause harm. All of the trials were biased in some way and when we measured the quality of all of the results we found them to be of low or very low quality. As a result the results of this review should be viewed with caution.

The nature of the results means that we cannot make any recommendations for how email might best be used in clinical practice. Future research should make allowances for how quickly technology changes, and should consider how much email would cost to introduce and what effect it has on the use of healthcare resources. Research reports should be sure to clearly report their methods and findings, and researchers interested in carrying out research in this area should be assisted in developing ideas and put them into action.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Summary of findings: Email as additional communication method compared to standard methods: Patient participants.

| Email as additional method of communication compared to standard methods of communication | |||

| Patient or population: Healthcare usersa Settings: Different healthcare settings b Intervention: Email communicationc | |||

| Outcomes | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Impact |

| Patient's understanding | 74 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowd,e,f | It was not possible to adequately assess whether email has any effect on a patient's understanding. |

| Patient health status and wellbeing | 147 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowg,h,i,j,k | It was not possible to adequately assess whether email has any effect on a patient's health status and wellbeing |

| Patient/caregiver views | 90 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowl, m | It was not possible to adequately assess whether email has any effect on patient/caregiver views |

| Patient behaviours and actions | 147 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lown,o,p,q | It was not possible to adequately assess whether email has any effect on patient behaviours and actions, though it is possible to report that email did not have any effect on a patient's use of the internet. |

| Health service outcome; resource use | 379 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowr,s,t,u | It is unclear to what extent email impacts on resource use when compared with standard methods of communication, with studies reporting variable results or having missing data. |

| Health professional outcomes | 0 (0) | See impact | NOT MEASURED |

| Harms | 0 (0) | See impact | NOT MEASURED |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

a children & young adults, caregivers, adults b head and neck surgery, paediatric dermatology clinic, augmentative communication service, heart failure clinic, primary care. c standard email, secure web system, patient portal. d Serious limitation, 3 of 6 domains have high risk of bias e Examines patient understanding in relation to post‐operative instructions only f One study for this outcome, 74 participants responding, measure using median values as data not normally distributed. g Two studies, one with 3 of 6 domains high risk, another with 4 of 6 high risk h Both studies found no significant difference between groups. One study has missing data i Both studies found no significant difference between groups. One study has missing data j Not possible to fully assess precision due to missing data for one of the studies. One of the studies uses median values. k One measure for this outcome was not fully reported, and author told us upon contact that this was because the difference between groups was not significant. l Both studies with 3 of 6 domains high risk m One study looks only at median values. Other study had very small sample size and did not carry out any analysis of data. n Two studies, one with 3 of 6 domains high risk, another with 4 of 6. o A mix of general measures (use of Internet, costs, resources) and setting specific measures. p One measure uses median values, other measures do not present confidence intervals, data are partly missing for two measures. q Three measures for this outcome were not fully reported, and author told us upon contact that this was because the difference between groups was not significant. r One study has 1 of 6 domains high risk, two have 4 of 6 domains s Evidence is inconclusive,each study has contradictory results for different measures under this outcome t One measure looked at use of complementary therapy. Three measures set in heart failure clinic with heart failure patients. But all measures general in relation to resource use. u For one measure data are missing and authors say this is because the difference between groups was not significant. Two measures look at the same thing over two different time points, no justification given for splitting the time period (first 6 months, second 6 months of intervention) and data are not presented for the study period overall. This could be construed as selective reporting.

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings: Email as additional communication method compared to standard methods: Healthcare professional participants.

| Email as additional method of communication compared to standard methods of communication | |||

| Patient or population: Physicians Settings: Primary care clinics Intervention: Email communication1 | |||

| Outcomes | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Impact |

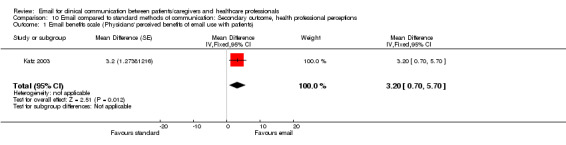

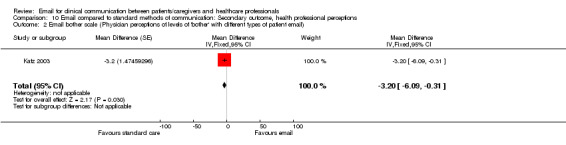

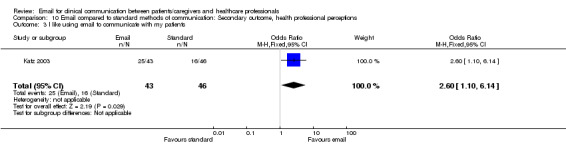

| Patient related outcomes | 0 (0) | See impact | NOT MEASURED |

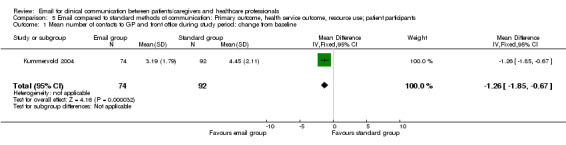

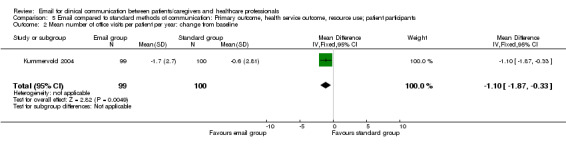

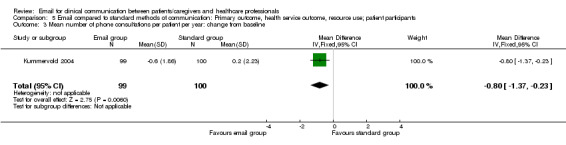

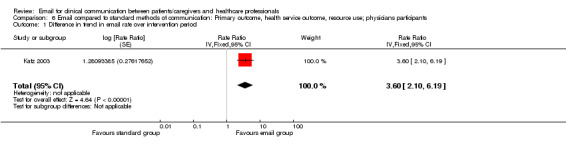

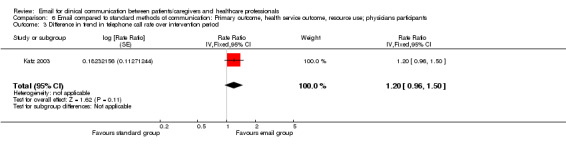

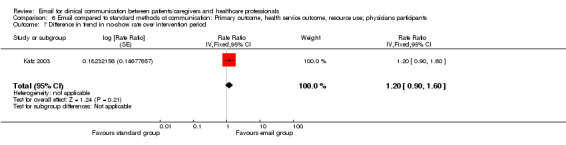

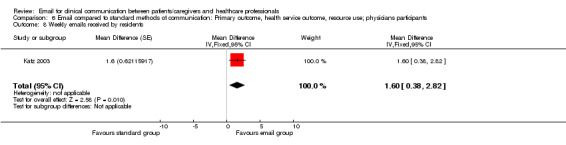

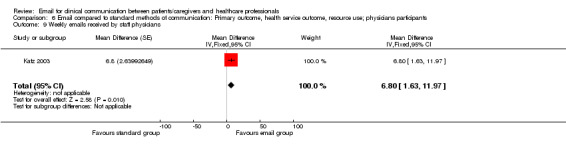

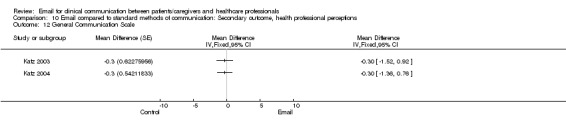

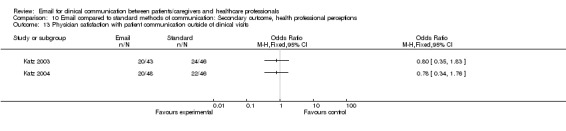

| Health service outcome; resource use | 230 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3 | It is unclear to what extent email impacts on resource use when compared with standard methods of communication, with studies reporting variable results or having missing data, though results indicate that an email intervention leads to an increased number of emails and telephone calls being received by healthcare professionals as compared to standard methods of communication. |

| Health professional outcome | 0 (0) | See impact | NOT MEASURED |

| Harms | 0 (0) | See impact | NOT MEASURED |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

1 Secure email interface, secure web based tool 2 Both studies have 3 of 6 domains at high risk of bias, and one domain unclear. 3 Evidence within studies is inconclusive; each study has contradictory results for different measures under the same outcome; some measures are significantly different, others not.

Summary of findings 3. Summary of findings: Email counselling compared with telephone counselling.

| Email counselling compared with telephone counselling | |||

| Patient or population: Adults (25‐60 years) Settings: Independent research clinic Intervention: Email counselling Comparison: Telephone counselling | |||

| Outcomes | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Impact |

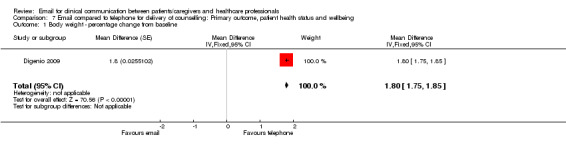

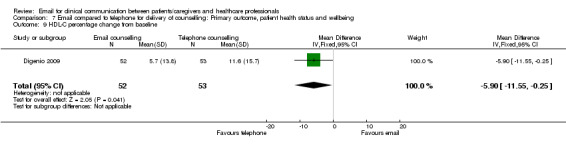

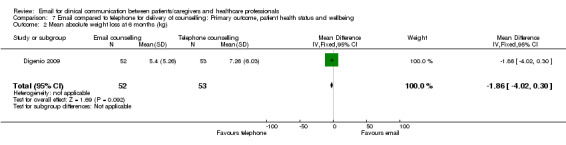

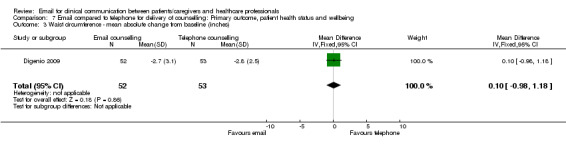

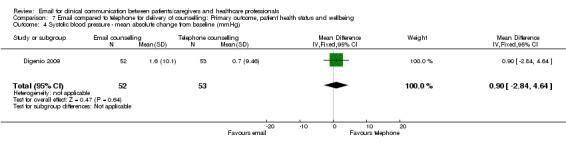

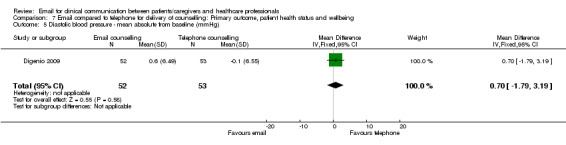

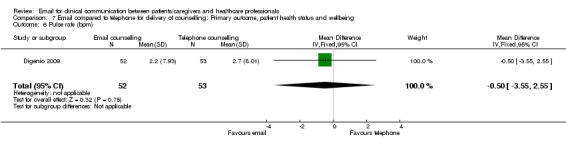

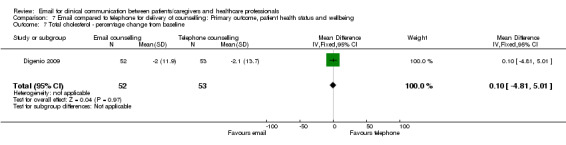

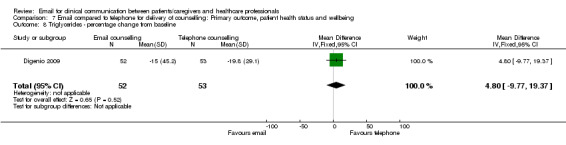

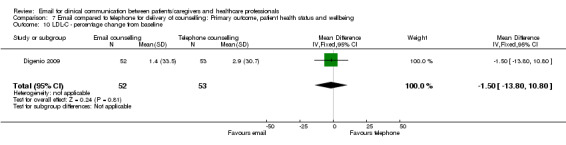

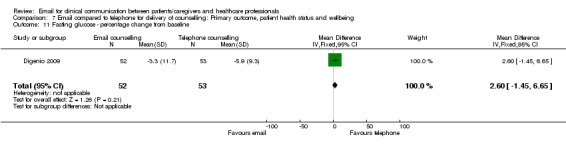

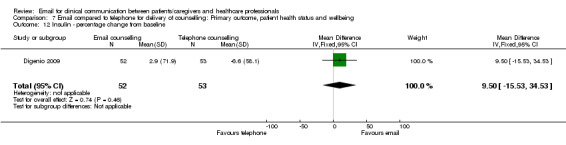

| Patient health status and wellbeing | 105 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3,4,5 | Telephone counselling leads to greater change than email counselling for some, but not all, measures of patient health status and wellbeing. There was no difference between groups for the majority of measures. |

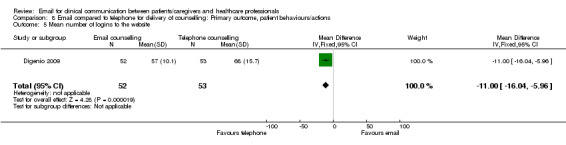

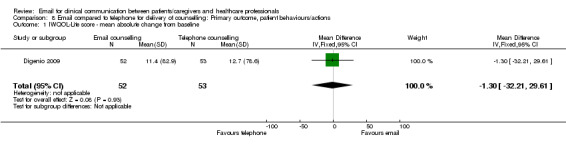

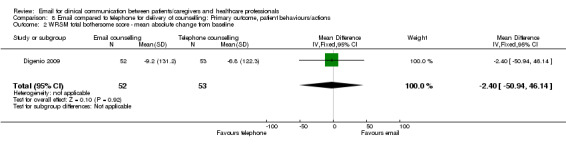

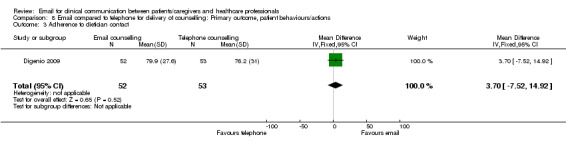

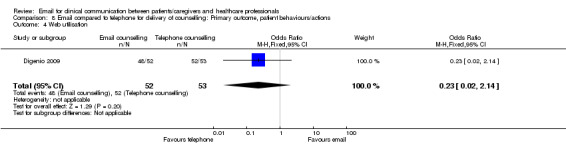

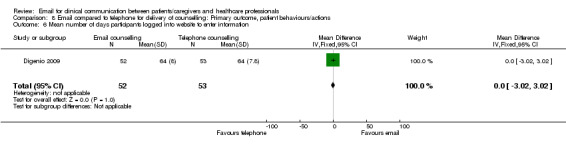

| Patient behaviours and actions | 105 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low6,7 | Telephone counselling leads to greater change than email counselling for some, but not all, measures of patient behaviours and actions. There was no difference between groups for the majority of measures. |

| Health service outcomes | 0 (0) | See impact | NOT MEASURED |

| Health professional outcomes | 0 (0) | See impact | NOT MEASURED |

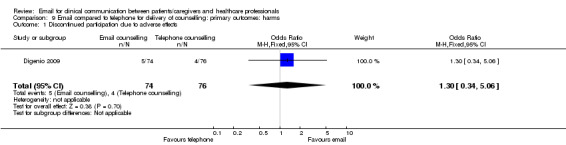

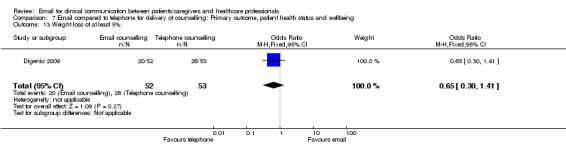

| Harms | 105 (1 study) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low6,7 | There is no difference in harms between the email and telephone counselling groups. |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

1 For this study 4 of 6 domains have high risk of bias. 2 One study with twelve different measures from the same study for this outcome. No comparison data, but 9 measures in favour of telephone and 3 in favour of email. Two post hoc measures favoured the telephone. 3 Population is patients meeting very specific criteria for obesity and drug intake. Setting is research clinic, which is not very applicable in the real world sense intended by this review. 4 Only one study. Confidence intervals visibly wide for three measures. 5 Two measures presented that were from a post hoc analysis. 6 For this study 4 of 6 domains with high risk of bias. 7 Population is patients meeting very specific criteria for obesity and drug intake. Setting is research clinic, which is not very applicable in the real world sense intended by this review.

Background

Related systematic reviews

This review forms part of a suite of reviews, incorporating four other reviews:

email for the provision of information on disease prevention and health promotion (Sawmynaden 2012);

email for communicating results of diagnostic medical investigations to patients (Meyer 2012);

email for the clinical communication between healthcare professionals (Pappas 2012); and

email for the coordination of healthcare appointments and attendance reminders (Atherton 2012).

The use of email

Email is easy to use, widely available across the world, and inexpensive. It is used in many areas of life, such as banking, travel and retail. Despite the ubiquity of email in day‐to‐day life and in other sectors of the economy, its use in the healthcare sector is still not routine (Neville 2004; Dixon 2010) though is on the increase. Factors driving the trend of increasing email use include the natural demographic shift towards an increasing proportion of people comfortable with using technology‐driven care solutions, and increasing demands on healthcare resources(OECD 2006).

In 1998 a survey of American physicians showed that less than seven per cent had used email to contact their patients (Lacher 2000); however more recent surveys show this to be increasing. US surveys have revealed that the increase in use is variable, from 16% of physicians using email in a survey of primary care practitioners to as many as 72% in a large outpatients' department (Gaster 2003; Brooks 2006). Uptake may vary according to patient group. The majority (79%) of doctors at a student health centre in Finland reported email use with patients (Castren 2005).

Nonetheless, the volume of email communication remains low, with surveys reporting averages from 7.7 emails per month to 8.6 emails per week in the aforementioned Finnish student healthcare centre (Gaster 2003; Castren 2005). Email communication was used for requesting prescriptions, booking appointments and for clinical consultation. It was commonly noted that email was used for non‐urgent communication only (Gaster 2003; Brooks 2006).

Several factors are likely to continue to drive the trend of increasing email use, including increasing patient demand, (Couchman 2001; Kleiner 2002; Moyer 2002),Harris 2006a natural demographic shift toward an increasing proportion of doctors (and patients) comfortable with using technology‐driven care solutions, and increasing per capita demand on healthcare resources (OECD 2006).

Email for clinical communication between patients and healthcare professionals

Email for clinical communication between patients and healthcare professionals can take several forms. Email consultations can be used instead of telephone consultations for simple and non‐urgent conditions (Car 2004b) such as urinary tract infections or back pain (Kassirer 2000). This may help to address unmet need for some patients in primary care, who may not otherwise be able to contact their practitioner easily (Katz 2003; White 2004). Healthcare professionals as well as patients have been shown to prefer email over telephone consultations for non‐urgent problems (Liederman 2003). This may act as a complementary method of communication, rather than wholly replacing face‐to‐face consultations.

Qualitative evidence has shown that healthcare professionals who use email for patient consultations think it is a useful addition to conventional methods of consultation, being easy to use and improving communication. Email may also enhance management of chronic diseases, improve continuity of care and increase healthcare professionals' flexibility in responding to non‐urgent issues (Liederman 2003; Patt 2003).

Email consultations are not appropriate for every circumstance, such as urgent communications and queries about symptoms like or chest pain that could indicate an emergency situation (Car 2004a), and for controversial topics such as illicit drug use (Dunbar 2003; Katz 2003). In some cases patients may provide incomplete, abstract or inappropriate information via email, requiring professionals to use a different method of communication such as telephone or face‐to‐face consultation for clarification (Patt 2003). Car 2004b There is recognition that the acceptability and potential of email communication will vary from patient to patient (Kassirer 2000).

The use of a standard protocol for email communication by both healthcare professional and patient might address these circumstances. This may include the types of communication permitted via email, such as administrative issues or specific clinical conditions. The patient could be advised not to email their healthcare provider regarding urgent conditions (Car 2004b).

Triage

Possible systems for implementation include triage‐based systems for messages about health concerns, prescription renewals and referrals, all controlled by a nurse 'navigator' (Katz 2003).

Sensitive issues

Email communication, by removing the face‐to‐face element of an 'in person' consultation, may encourage patients to raise sensitive or embarrassing issues that they may not otherwise discuss, thus addressing an unmet need. Caregivers have been documented as raising on behalf of the patient an issue that they have been reluctant to discuss with the healthcare professional (Patt 2003). Awareness of such an issue may provide a lead in to their discussion in any future consultation.

Chronic diseases

Email consultation allows ongoing and close monitoring and support of patients with chronic diseases (Kleiner 2002). Patients may also be able to communicate health data such as blood pressure levels or glucose levels to their healthcare professional for monitoring (Katz 2004). This type of service can improve continuity of care (Balas 1997), reduce the number of face‐to‐face consultations required, and improve quality of care and quality of life (Perlemuter 2002).

Follow up

Email can be used for communicating reminders to encourage adherence to treatment, and to solicit responses about side effects of medication. Dunbar 2003 reports high satisfaction and improved medication adherence with such systems. Email can also be used for follow up, for instance after an appointment with a physician (Katz 2003), when clarification or added information may be required (Patt 2003). Email can be used before an appointment, for ongoing health updates from patient to physician (White 2004), and to replace outpatient appointments after day surgery(Wedderburn 1996; Ellis 1999).

Advantages and disadvantages

The key advantages of email for clinical communication between patients and healthcare professionals include the following (adapted from Freed 2003; Car 2004a):

Timely and low cost delivery of information (relative to conventional mail) (Houston 2003)

Convenience: emails can be sent and subsequently read at an opportune time, outside of traditional office hours where convenient (Leong 2005).

'Read receipts' can be used to confirm that communications have been received.

Relative to oral communication, the written nature of the communication can be of value as reference for the patient, aiding recall and providing evidence of the exchange (Car 2004a; Car 2004b).

Email addresses usually stay constant when an address or telephone number changes (Virji 2006) making this a reliable way of maintaining communication with transient patients.

Email may improve access for non‐urgent and simple enquiries (Kassirer 2000, Katz 2003).

Emails can be archived in online or offline folders separate from the inbox of the email account so that they do not use up space in the inbox but can be kept for reference (Car 2004a; Car 2004b).

Patients may perceive email as a more intimate and considered form of communication than using the telephone (Katz 2003).

Email is an easier communication method for patients with disabilities, and with patients who are temporarily overseas e.g. seconded employees (Goodyear‐Smith 2005).

There are also potential downsides, including the following.

There is evidence of patient and physician concerns about privacy, confidentiality and potential misuse of information (Fridsma 1994; Harris 2006; Kleiner 2002; Moyer 2002; Katzen 2005).

Physicians may be wary of the potential for email to generate an increased workload (Mandl 1998; Pondichetty 2004).

Patients may expect a quick response, often within 48 hours, which may be problematic for healthcare professionals (Couchman 2001; Sittig 2001; Liederman 2003).

Email as a communication tool provides a different context for interaction. Face‐to‐face communication and telephone calls contain many layers of communication that are lost in an email; such as the emotive cues from vocal intonation or body language (Car 2004a). This may lead to misunderstandings.

The possible misuse of email for urgent clinical matters (Couchman 2001).

Recovery of implementation and other associated costs (especially in fee‐for‐service healthcare systems) (Mandl 1998).

Medico‐legal issues (including informed consent and use of non‐encrypted email) (Bitter 2000).

The potential to widen health inequalities via the digital divide (Kleiner 2002; Katz 2003; Goodyear‐Smith 2005; Virji 2006).

Technological issues may occur, such as recipients having a full mailbox causing email to bounce back to the sender (Virji 2006).

Systems may be at risk of failure, for instance a loss of the link to a central server (a computer which provides services used by other computers, such as email) (Car 2008a).

Potential for human error which can lead to unintended content or incorrect recipients.

Quality and safety issues

The main quality and safety issues around email consultation, as demonstrated in the previous section; advantages and disadvantages, are: privacy and confidentiality; potential for errors and ensuing liability; identifying clinical situations where email consultation is inefficient or inappropriate; securing payment; incorporating email into existing work patterns; and achievable costs (Moyer 1999; Kleiner 2002; Gaster 2003; Gordon 2003; Hobbs 2003, Houston 2003; Car 2004b).

Web messaging systems can address issues around security and liability that are associated with conventional email communication since they offer encryption capability and access controls (Liederman 2003). Such systems allow the structuring of communication; for example, messages can be triaged to the correct members of staff (Moyer 2002). However not all healthcare institutions are capable of providing such a facility and instead rely on standardised mail (Car 2004b).

Suggestions for minimising the legal risks of using email in practice include: adherence to the same strict data protection rules that must be followed in business and industry; adequate infrastructure to provide encrypted secure email transit and storage; and informed consent by the patient (Car 2004b). Additionally healthcare professionals may wish to exercise discretion about the patient's capability to use email communication. There may be patients who should be advised not to use this method of communication, and this should be at the discretion of the healthcare professional (Medem 2007).

Patient opinion of such systems is also important. Issues facing service users have included questionable reliability, timeliness and the impersonal nature of email (Katz 2003). However high patient satisfaction has been found in trials of email consultation, with patients preferring this method to telephone consultations and finding it easy to use (Liederman 2003). A content analysis of email communication between patients and healthcare professionals in the US found that only 1.8% of emails analysed were complaints, and these concerned timeliness and difficulties contacting the clinic via telephone (White 2004). The same content analysis found that patients adhered to guidelines for the use of email, avoiding urgent or sensitive requests and keeping emails formal and concise.

Education and training results in capable and competent end‐users of any technology. This can be costly and time consuming, but enhances the chance of effective implementation of such systems and thus should be a priority. A UK‐based survey showed that clinicians recently‐qualified feel more comfortable using the Internet and consider it reliable (Potts 2002). This is unsurprising given the relatively recent introduction of such technologies, and illustrates a potential generational effect on their use. This may influence training needs and the types of demographic groups leading the use of this technology. As well as the requirement for initial training, on‐going support is usually necessary to ensure continuing use and further development (Car 2008a).

Such issues are wide ranging and encompass both healthcare professional and patient perspective. All issues of quality and safety arising will be identified and addressed in the review.

Forms of electronic mail

In the absence of a standardised email communication infrastructure in the healthcare sector, email has been adopted in an ad‐hoc fashion and this has included the use of unsecured and secured email communication.

Standard unsecured email is email which is sent unencrypted. Secured email is encrypted; encryption transforms the text into an un‐interpretable format as it is transferred across the Internet. Encryption protects the confidentiality of the data, however both sender and recipient must have the appropriate software for encryption and decoding (TechWeb Network 2008).

Secure email also includes various specifically‐developed applications such as secure patient portals which utilise web messaging. Such portals provide pro‐formas into which patients can enter their message. The message is sent to the recipient as an email (TechWeb Network 2008). Secure websites are distributed by secure web servers. Web servers store and disseminate web pages. Secure servers ensure data from an Internet browser are encrypted before being uploaded to the relevant website. This makes it difficult for the data to be intercepted and deciphered (TechWeb Network 2008).

There are significant differences in terms of the applications. Bespoke secure email programmes may incorporate special features such as standard forms guiding the use and content of the email sent, ability to show read receipts (in order to confirm the patient has received the correspondence) and, if necessary, facilities for receiving payment (Liederman 2005). However they are costly to set up and may require a greater degree of skill on the part of the user than standard unsecured email (Katz 2004). For the purpose of the review we included all forms of email although secured versus unsecured email was to be considered in a subgroup analysis.

Methods of accessing email

Methods of accessing the Internet and thus an email account have changed with time. Traditionally access was via a personal computer or laptop at home or work, connecting to the Internet using a fixed line. There are now several methods of accessing the Internet. Wireless networks (known colloquially as wifi) allow Internet connection to a personal computer, laptop computer or other device wherever a network is available (TechWeb Network 2008). Internet connection is also possible via alternative networks using mobile devices. This includes access via mobile telephones to a wireless application protocol (WAP) network (rather than to the www) or to third generation (3G) network. Adaptors connecting to a universal serial bus (USB) port can be used to access the 3G network using a laptop computer (TechWeb Network 2008). Therefore email can be accessed away from the office or home in a variety of ways.

For the purposes of the review we included all methods of accessing email.

Objectives

To assess the effects of healthcare professionals and patients using email to communicate with each other; on patient outcomes, health service performance, service efficiency and acceptability, when compared to other forms of communicating clinical information.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs), quasi‐randomised trials, controlled before and after studies (CBAs) with at least two intervention and two control sites, and interrupted time series (ITS) with at least three time points before and after intervention.

Due to the practicalities of organisational change in a healthcare environment, most studies are not randomised and therefore we included quasi‐randomised trials and CBAs. The inclusion of ITS is particularly valuable in assessing the ongoing merits of a new technology which may require a 'settling in' period. We included trials with individual and cluster randomisation, and relevant trials with economic evaluations.

Types of participants

We included all healthcare professionals, patients and caregivers regardless of age, gender and ethnicity. We included studies in all settings i.e. primary care settings (services of primary health care), outpatient settings (outpatient clinics), community settings (public health settings) and hospital settings. We did not exclude studies according to the type of healthcare professional (e.g. surgeon, nurse, doctor, allied staff).

We considered participants originating the email communication, receiving the email communication and copied into the email communication.

Types of interventions

We included studies in which email was used for two‐way clinical communication between patients/caregivers and healthcare professionals. We included interventions that use email to allow patients to communicate clinical concerns to a healthcare professional and receive a reply.

We included interventions that used email in any of the following three forms:

Unsecured standard email to/from a standard email account.

Secure email which is encrypted in transit and sent to/from a standard email account with the appropriate encryption decoding software.

Web messaging; whereby the message is entered into a pro‐forma which is sent to a specific email account, the address of which is not available to the sender.

We included all methods of accessing email, including broadband via a fixed line, broadband via a wireless connection, and connecting to the 3G network and the WAP network.

We excluded studies which considered the general use of email for healthcare professional‐patient contact for multiple purposes but did not separately consider clinical communication between patients/caregivers and healthcare professionals. We included studies in which email was one part of a multifaceted intervention, if the effects of the email component were individually reported, even if they did not represent the primary outcome. However these were only included where they achieved the appropriate statistical power. Where this could not be determined or where it was not possible to separate the effects of the multifaceted intervention, they were not included.

We considered comparisons between outcomes of email communication and no intervention, as well as other modes of communication such as face‐to‐face, postal letters, calls to a landline or mobile telephone, text messaging using a mobile telephone, and automated versus personal emails.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes of interest were whether the email was understood and acted upon correctly by the recipient as intended by the sender, and secondary outcomes were whether email was an appropriate mode for the communication exchange.

Primary outcomes

Healthcare professional outcomes resulting from whether the email was understood and acted upon correctly by the recipient as intended by the sender (where this impacts on the healthcare professional), e.g. professional knowledge and understanding, professional preferences or views, and behaviour, action or performance.

Patient outcomes associated with whether email has been understood and acted upon correctly by the recipient as intended by the sender, e.g. patient's understanding, patient health status and well‐being, patient views and patient behaviours or actions (such as adherence to treatment advice).

Health service outcomes associated with whether email has been understood and acted upon correctly by the recipient as intended by the sender, e.g. rates of treatment adherence.

Harms e.g. effects on safety or quality of care such as missed diagnoses, breaches in privacy, technology failures.

Secondary outcomes

Professional, patient or caregiver outcomes associated with whether email was an appropriate mode for the communication exchange, e.g. knowledge and understanding, effects on professional‐patient or professional‐caregiver communication or relationship, evaluations of care (convenience, timeliness, acceptability, satisfaction).

Health service outcomes associated with whether email was an appropriate mode for the communication exchange, e.g. use of resources or time, costs, use of medical services, referrals, admissions.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched:

Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group Specialised Register (searched 8 January 2010)

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, The Cochrane Library, Issue 1 2010)

MEDLINE (OvidSP) (1950 to 5 January 2010)

EMBASE (OvidSP) (1980 to 7 January 2010)

PsycINFO (OvidSP) (1967 to 5 January 2010)

CINAHL (EbscoHOST) (1982 to 2 February 2010)

ERIC (CSA) (1965 to 7 January 2010)

We present detailed search strategies in Appendices 1 to 5. John Kis‐Rigo, Trials Search Coordinator for the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group compiled the strategies.

There were no language or date restrictions.

Searching other resources

Grey literature

We searched:

Australasian Digital Theses Program (http://adt.caul.edu.au/) (searched July 2010)

Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations (http://www.ndltd.org) (searched July 2010)

UMI ProQuest Digital Dissertations (http://wwwlib.umi.com/dissertations/) (searched July 2010)

Index to Theses (http://www.theses.com/) (Great Britain and Ireland) (searched July 2010)

Clinical trials register (Clinicaltrials.gov) (searched July 2010)

WHO Clinical Trial Search Portal (www.who.int/trialsearch) (searched July 2010)

Current Controlled Trials (www.controlled‐trials.com) (searched July 2010)

Google Scholar (http://scholar.google.co.uk/) (we examined the first 500 hits) (searched July 2010)

We searched online trials registers for ongoing and recently completed studies and contacted authors where relevant. We kept detailed records of all the search strategies applied.

Reference lists

We also examined the reference lists of retrieved relevant studies.

Correspondence

We contacted the authors of included studies for advice as to any further studies or unpublished data that they were aware of. Many of the authors of included studies were also experts in the field.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (HA and PS) independently assessed the potential relevance of all titles and abstracts identified from electronic searches. We retrieved full text copies of all articles judged to be potentially relevant. Both HA and PS independently assessed these retrieved articles for inclusion. Where HA and PS could not reach consensus a third author, JC, examined these articles.

During a meeting of all review authors, we verified the final list of included and excluded studies. Any disagreements about particular studies were resolved by discussion. Where the description of a study was insufficiently detailed to allow us to judge whether it met the review's inclusion criteria, we contacted the study authors seeking more detailed information to allow a final judgement regarding inclusion or exclusion. We retain detailed records of these communications.

Data extraction and management

We extracted data from all included studies using a standard form derived from the data extraction template provided by the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group. We extracted the following data:

General information: Title, authors, source, publication status, date published, language, review author information, date reviewed.

Details of study: Aim of intervention and study, study design, location and details of setting, methods of recruitment of participants, inclusion/exclusion criteria, ethical approval and informed consent, consumer involvement.

Assessment of study quality: Key features of allocation, contemporaneous data collection for intervention and control groups; and for interrupted time series, number of data points collected before and after the intervention, follow‐up of participants.

Risk of bias: data to be extracted was dependent on study design (see Assessment of risk of bias in included studies).

Participants: Description, geographical location, setting, number screened, number randomised, number completing the study, age, gender, ethnicity, socio‐economic grouping and other baseline characteristics, health problem, diagnosis, treatment.

Health service: description, geographical location, setting, age, gender, population served, medical setting and clinical context of patients.

Intervention: Description of the intervention and control including rationale for intervention versus the control (usual care). Delivery of the intervention including email type (standard unsecured email, secure email, web portal or hybrid). Type of clinical information communicated. Content of communication (e.g. text, image). Purpose of communication (e.g. obtaining information, providing information). Communication protocols in place. Who delivers the intervention (e.g. healthcare professional, administrative staff). How consumers of interventions are identified. Sender of first communication (health service, professional, patient and/or caregiver). Recipients of first communication (health service, professional, patient and/or caregiver). Whether communication is responded to (content, frequency, method of media). Any co‐interventions included. Duration of intervention. Quality of intervention. Follow up period and rationale for chosen period.

Outcomes: principal and secondary outcomes, methods for measuring outcomes, methods of follow‐up, tools used to measure outcomes, whether the outcome is validated.

Results: for outcomes and timing of outcome assessment, control and intervention groups where applicable.

HA and PS piloted the data extraction template. For every included study both HA and PS independently performed the data extraction. Any discrepancies between the review authors' data extraction sheets were discussed and resolved by HA and PS. Where necessary, we involved JC to resolve discrepancies.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors, HA and PS, independently assessed the risk of bias of included studies, with any disagreements resolved by discussion and consensus, and by consulting a third author, JC, where necessary.

We assessed and reported on the following elements that contribute to bias, according to the guidelines outlined in Higgins 2008:

Sequence generation;

Allocation concealment;

Blinding (outcomes assessors);

Intention‐to‐treat analysis;

Incomplete outcome data;

Selective outcome reporting.

We assigned a judgement relating to the risk of bias for each item. We used a template to guide the assessment of risk of bias, based upon Higgins 2008, judging each item as low, unclear or high risk of bias. We summarised risk of bias for each outcome where this differed within studies.

We also assessed a range of other possible sources of bias and indicators of study quality, in accordance with the guidelines of the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group (Ryan 2007), including:

Baseline comparability of groups;

Validation of outcome assessment tools;

Reliability of outcome measures;

Other possible sources of bias

We present the results of the risk of bias assessment in tables and have incorporated the results of the assessment into the review through systematic narrative description and commentary about each of the risk of bias items. This led to an overall assessment of the risk of bias across the included studies and a judgement about the possible effects of bias on the effect sizes of the included studies.

We contacted study authors (where possible) for additional information about the included studies, or for clarification of the study methods as required.

For the cluster randomised trials we used chapter 16, section 16.3.2 of Higgins 2008 to aid assessment of risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous data, where data were available, we report the odds ratio/rate ratio and confidence intervals. For continuous data, where data were available, we report the mean difference and confidence intervals. For outcomes where data were missing, where possible we calculated standard error from confidence intervals, or P values where these were available. The standard error value was calculated presuming that a Z test had been used in the study in question, unless authors stated that a t test had been used. We could then calculate a mean difference using generic inverse variance.

Where confidence intervals or a P value were not available, it was not possible to calculate standard error values and so we have reported the mean values for the intervention versus control group and total number of participants in each group, in 'other data' tables. Where data were available only as median values, we present them as such.

Unit of analysis issues

We included two cluster randomised trials in the review (Katz 2003; Katz 2004). These were identified as cluster randomised trials after contact with the authors revealed a cluster method of randomisation had been used, but the trial was presented as a parallel group trial with some variables controlled for 'physician clinic.' It is possible to correct for data that have been analysed as though individual randomisation has taken place, but we were unable to do this because the required data were not available to us, either in the report or via the authors (see Appendix 2 for list of required information). Therefore any outcome data presented for these studies must be viewed in light of the potential unit of analysis errors. As the unit of analysis is different from the unit of allocation, any resulting P values are artificially small, which can result in false positive conclusions that the intervention had an effect (Higgins 2008). This does not bias the estimate of effect, but was considered in presenting the results of the review.

Dealing with missing data

Where data were not available with which to calculate an effect estimate, we contacted authors of the studies to obtain relevant information.

Data synthesis

In a meeting of three of the review authors (HA, PS, JC) the included studies were assessed and it was decided that it was not possible to combine the data in a meta‐analysis. Most outcomes were represented by only one study, and there were unobtainable missing data which meant that effect estimates could not always be calculated. The methods that we would have applied had data analysis and pooling been possible are outlined in Appendix 2 and will be applied to future updates of the review. Instead, we provide a summary of the overall findings for each outcome group at Effects of interventions.

We also applied the GRADE approach to assessing the quality of outcomes, and produced three Summary of findings Tables to outline the overall result for each individual outcome. In order to rate each outcome according to quality, two authors (HA and PS) each independently rated the outcomes according to the five factors, using guidance from the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews and the GRADE working group (Higgins 2008; GRADE 2010). Where ratings differed these were discussed until consensus was reached. Where consensus could not be reached a third author, JC, was consulted. We entered the finalised ratings into the GRADEpro software.

A typical Summary of Findings table produced in GRADEpro software contains a list of all important outcomes (usually primary outcomes per the review), a measure of the typical burden of these outcomes, the absolute and relative magnitude of effect (either/or), the number of participants and studies addressing these outcomes and a grade score for the overall quality of evidence for each outcome (rather than by study). For the purposes of this review we adapted the tables to account for the lack of data pooling. Although there was a lack of numerical data the Summary of Findings table was still a useful tool in summarising the findings of the review for the reader, and allowing for the quality of the outcomes to be assessed using the GRADE quality of the evidence framework.

We designed the Summary of Findings tables to contain the following:

Each primary outcome (patient outcomes, health professional outcomes, health service outcomes and harms).

Corresponding number of participants and studies.

Quality of the evidence (GRADE score).

Impact (via brief narrative summary).

We used an impact statement for each outcome to summarise the evidence available in the absence of statistical pooling. This statement was based on the measures of effect as entered into the review. Where the outcome had not been measured by any study in the review we stated this in the Summary of Findings tables. (See Table 1; Table 2; Table 3).

Consumer input

We asked two consumers, a health services researcher (UK) and healthcare consultant (Saudi Arabia) to comment on the completed review before submitting the review for the peer‐review process, with a view to improving the applicability of the review to potential users. The review also received feedback from two consumer referees as part of the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group's standard editorial process.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

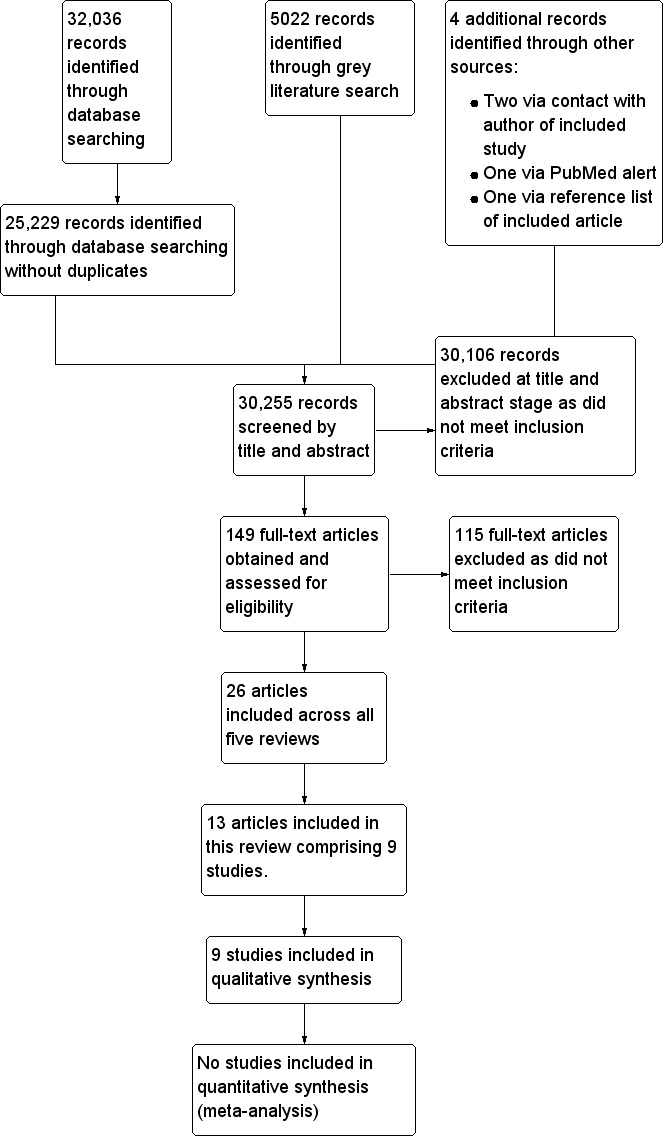

As this review was one in a suite of five looking at varying uses of email in healthcare, we conducted a common search for all five reviews (Atherton 2012; Meyer 2012; Pappas 2012; Sawmynaden 2012). We allocated relevant articles to each review after assessing them in full text. Figure 1 shows the search and selection process.

1.

Flow diagram illustrating search results.

Included studies

We included nine studies enrolling 1733 participants (MacKinnon 1995; Katz 2003; Katz 2004; Kummervold 2004; Ross 2004; Lin 2005; Stalberg 2008; Bergmo 2009; Digenio 2009). These 9 studies were reported in 13 papers; Kummervold 2004 was reported in a thesis and 3 journal articles, and Katz 2003 was reported in an abstract and a journal article.

Design

All of the included studies were randomised controlled trials. However not all authors described their studies as such. Digenio 2009 describes the study as a "randomised 6 month open label study" because all participants were aware that they were receiving a weight loss drug. MacKinnon 1995 describes the study as a pretest‐post‐test control group design with random assignment. Stalberg 2008 described the study as a ‘prospective randomised controlled clinical trial’.

Two studies (Katz 2003; Katz 2004) were described and analysed by the authors as parallel group randomised controlled trials, but contact with one of the authors revealed that the method of randomisation used involved randomising individuals in groups to avoid contamination. For the purposes of the review we classified these two studies as cluster‐RCTs.

Sample sizes

Sample sizes ranged from n = 16 to n = 606 participants.Three studies used power calculations (Ross 2004; Lin 2005; Digenio 2009). Two used post‐hoc power calculations (Katz 2003; Katz 2004) and four did not use a power calculation (MacKinnon 1995; Kummervold 2004; Stalberg 2008; Bergmo 2009). Of the three studies using power calculations one was adequately powered (Digenio 2009).

Setting

All studies were conducted in high income countries, as follows:

| Country | Study |

| USA | 5 studies: Katz 2003; Katz 2004; Ross 2004; Lin 2005; Digenio 2009 |

| Norway | 2 studies: Kummervold 2004; Bergmo 2009 |

| Canada | MacKinnon 1995 |

| Australia | Stalberg 2008 |

Studies were conducted in a variety of healthcare settings across primary, secondary and tertiary care, and in the community.

Primary care

Three studies were set in primary care settings; Katz 2003 and Katz 2004 in primary care clinics affiliated with the University of Michigan and Kummervold 2004 in a group general practice with a city office and two district practices.

Secondary and tertiary care

Three studies were set in secondary care, specifically in outpatient settings. Bergmo 2009 was set in a paediatric and dermatology outpatient clinic in a secondary care hospital, Lin 2005 was set in an ambulatory internal medical practice affiliated with the University of Colorado Hospital. Ross 2004 was also set at the University of Colorado Hospital in a speciality outpatient clinic for heart failure. Stalberg 2008 was set in tertiary care, specifically a peri‐operative surgical setting for head and neck surgery at a tertiary referral centre.

Community and other care

MacKinnon 1995 was set in a rehabilitation centre providing an augmentative communication service for children/young adults with physical disability. Finally, Digenio 2009 was set in 12 research centres comprised mostly of non‐academic independent clinics. This setting was different to the others in that it was a research‐focused healthcare setting, rather than a conventional healthcare setting.

Participants

Participants were adults in all studies except MacKinnon 1995, in which participants were children and young adults with physical disabilities. These children and young adults (aged 7 to 25 years) were already clients of an augmentative communication service. They had a range of physical disabilities, though the majority suffered from cerebral palsy (12 of 16 participants). In Bergmo 2009 participants were the parents (caregivers) of the children attending the paediatric dermatology clinic and the intervention was aimed at the parent, although the outcomes assessed concerned both parents (parental behaviour) and children (child health status).

Five studies included adult patient participants. In Digenio 2009 participants had to be aged 25 to 60 years and have a body mass index of between 30 and 40. For Ross 2004 and Lin 2005 patients had to be at least 18 years old and English speaking. For Stalberg 2008 participants were those referred for thyroid or parathyroid surgery and aged 18 to 65. In Kummervold 2004 participants were patients at the general practice.

In the remaining two studies the adult participants were physicians; specifically a mixture of staff and resident physicians (Katz 2004), and faculty and resident physicians in primary care (Katz 2003).

Access to email

Some studies specified that participants should have a certain level of Internet or email access. Specifications included having access to the Internet and email (Digenio 2009), having access to the Internet and a personal cell phone (Kummervold 2004) and having both home and work access to the Internet (Stalberg 2008). In MacKinnon 1995 participants in the intervention group were provided with the equipment needed to use the email service because the use of the Internet and email was not widespread at that time. For two studies patients only had to have experience of using an Internet browser (Ross 2004, Lin 2005).

Interventions

Each study featured a different intervention.

Purpose and type

Five studies used some form of web‐messaging as their intervention (Katz 2004; Kummervold 2004; Ross 2004; Lin 2005; Bergmo 2009). In the remaining four studies the type of email was not specified, but in two of these studies (Stalberg 2008; Digenio 2009) it was presumed to be standard email because of the nature of the intervention described.

The intervention by Bergmo 2009 was a secure messaging system allowing parents of children to contact a dermatological specialist with a written description of the child’s condition along with the option to attach photos of the eczema area. Parents received a reply containing treatment advice. This was the only study to utilise images.

Three studies set in primary care examined interventions consisting of messages with general content (such as general enquiries, test results, and information). Katz 2004 trialled a secure web‐based patient‐provider tool, which allowed patients to communicate with clinic staff. Kummervold 2004 used a system called 'PatientLink', an electronic messaging system for sending unstructured messages between doctors and patients. Patients used a web browser to log in and send messages to the doctor. Katz 2003 trialled an intervention known as EMAIL (Electronic Messaging, Advice and Information Link). It is not clear what type of email is used in the EMAIL intervention other than it being described as an ‘email interface’ between patients and the health system, mediated by triage nurses.

Two studies featured multi‐faceted interventions and for the purposes of this review the outcomes relating to electronic messaging were of interest. 'My Doctor’s Office', a patient portal, was trialled by Lin 2005. This intervention allowed patients to request appointments, prescription refills and specialist referrals, and send secure electronic messages to their physicians. Clinical messages were sent directly to the physician, who could send an electronic response to the patient or forward the message with instructions to clinic nurses. Ross 2004 trialled SPPARO (System Providing Patients Access to Records Online). There were three components to SPPARO: access to the medical record, an educational guide and an electronic messaging system. The messaging system allowed patients to exchange secure messages with nursing staff in the speciality heart failure clinic.

Both MacKinnon 1995 and Stalberg 2008 asked patients in the intervention group to use email as their first line of contact with their health professional. In MacKinnon 1995 participants were asked to make all of their contacts to the augmentative communication service by email. The exact type of email is unknown because of the age of the study and subsequent changes in technology. In Stalberg 2008 participants were given an information sheet relating to their surgery with the surgeon’s email address as the top listed method of communication.

Digenio 2009 administered a lifestyle modification programme. Participants received weekly dietician contact via email during the first three months of the study and every other week during the following three months. This study also did not specify the type of email used, but it was presumed to be standard email.

Comparator

Email with usual care compared to usual care alone (standard methods of communication)

Eight studies compared the intervention as being additional to usual care for patients, usual care being the standard methods of communication offered in these settings (MacKinnon 1995; Katz 2003; Katz 2004; Kummervold 2004; Ross 2004; Lin 2005; Stalberg 2008; Bergmo 2009).

Email compared to telephone for delivery of counselling

Digenio 2009 was multi‐interventional with five arms. The group of interest was high frequency email counselling. Of the other four arms of the study (high frequency face to face counselling, low frequency face to face counselling, high frequency telephone counselling and lifestyle modification information with self care), high frequency telephone counselling was chosen as the comparator for the purpose of this review. Telephone is one of the specified comparators in this review, and in the context of the study provided the most appropriate comparison.

Communication protocol

Five studies had some sort of protocol around how the intervention should and would be used. This took the form of informal guidance and did not constitute a formal part of the trial. Four studies did not have any communication protocol at all according to the published reports (MacKinnon 1995; Ross 2004; Stalberg 2008; Digenio 2009).

Bergmo 2009 placed no restrictions on the number of messages each family could send during the 1‐year trial period and parents were informed that the specialist would respond within 24 hours or during the next working day. Katz 2003 asked patients to follow specific guidelines when emailing their physicians. The secure web site in Katz 2004 contained educational content addressing appropriate message content, expected response times and message handling by clinic staff.

Participants in Kummervold 2004 using the PasientLink system were free to decide the content, the length, the number of messages and the time of day that they wished to send messages, but they were told not to use it for acute problems. Participants in Lin 2005 using ‘My Doctor’s Office’ were warned in advance not to send urgent messages.

Outcomes

We outline details of the specific outcome measures in each study in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Patient/caregiver outcomes

Four studies reported primary patient outcomes. Three studies assessed both patient health and wellbeing and patient behaviour outcomes. Additionally Stalberg 2008 assessed patient understanding and patient views. MacKinnon 1995 assessed patient views. Three studies reported secondary patient outcomes, Lin 2005 and Stalberg 2008 reported the effect of email on patient‐professional communication, Kummervold 2004 and Stalberg 2008 reported evaluation of care and Kummervold 2004 also reported value of service.

Health professional outcomes

The only health professional outcome reported was a secondary outcome. Katz 2003 and Katz 2004 reported health professional perceptions.

Health service outcomes

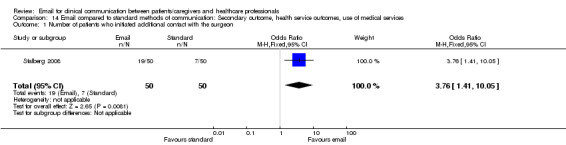

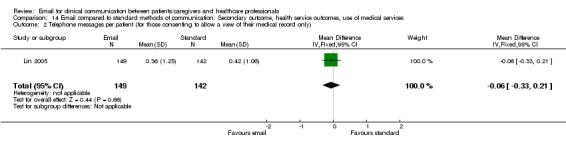

Five studies reported primary health service outcomes. Kummervold 2004; Ross 2004 and Bergmo 2009 had patient participants and reported resource use outcomes. Katz 2003 and Katz 2004 had physician participants and also reported resource use outcomes. Three studies reported secondary health service outcomes and in all studies these were use of medical services outcomes (MacKinnon 1995; Lin 2005; Stalberg 2008).

Harms

One study reported data relating to harms (Digenio 2009). Three studies (MacKinnon 1995; Katz 2004; Lin 2005) did report some information on adverse events but this was not in the form of outcomes.

Missing data

Data were missing from all studies and we contacted all authors to try and obtain it. Four provided some or all additional data when requested (Kummervold 2004; Ross 2004; Lin 2005; Digenio 2009). Authors for five studies were unable to provide requested data (MacKinnon 1995; Katz 2003; Katz 2004; Stalberg 2008; Bergmo 2009).

Excluded studies

Of the 149 full text articles retrieved across the suite of five reviews, eleven of these were deemed potentially relevant to this review and subsequently excluded upon further inspection (see Characteristics of excluded studies table). Six of these studies were multi‐faceted interventions with an email component, in which the effects of email were not individually reported (Tate 2003; Carlbring 2006; Klein 2006; Hanauer 2009; Klein 2009b; Leveille 2009). Two studies looking at email for follow‐up featured two‐way communication where the patient response was administrative rather than for clinical communication (Ezenkwele 2003; Goldman 2004). One study compared two interventions with differing frequencies of email support and rather than assessing the effect of the email, assessed only frequency (Klein 2009a). Two studies had an inappropriate study design (Leong 2005, Pier 2008).

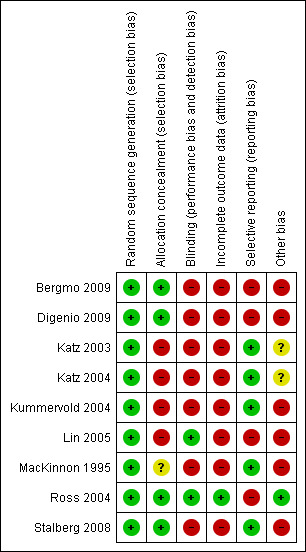

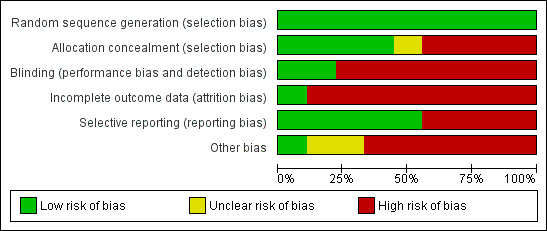

Risk of bias in included studies

All of the studies featured some bias. Figure 2 summarises the risk of bias for each included study and Figure 3 summarises the risk of bias for each domain. For three of the studies (MacKinnon 1995; Katz 2003; Katz 2004) there were unclear domains in the assessment of risk of bias; these remained unclear even after author contact.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

All of the included studies used adequate generation of allocation sequence. Just four studies reported adequate allocation concealment. (Ross 2004; Stalberg 2008; Bergmo 2009; Digenio 2009). MacKinnon 1995 did not provide information on allocation concealment and the author was unable to provide information when contacted. The remaining four studies reported inadequate allocation concealment.

Blinding

For many of the interventions in the review the blinding of participants (patients/caregivers, health professionals) was not feasible. Where participants were allocated to the intervention it was apparent, for instance that intervention participants had access to an email system, and control participants did not. Therefore for the purpose of this review we decided that the main focus in assessing of risk of bias related to blinding would be whether the investigators were blind to the allocation status of their participants.

Only two studies were adequately blinded (Ross 2004; Lin 2005). In Bergmo 2009 not all investigators were blinded. The dermatologist assessing the severity of eczema in participants was aware of group allocation. For all other outcomes investigators were blinded.

In the remaining studies investigators were not blind to participant allocation. Contact with the authors of MacKinnon 1995; Katz 2003; Katz 2004 and Digenio 2009 confirmed that investigators were not blinded. Kummervold 2004 state in one of the four publications associated with the study that blinding was not conducted in the project. In Stalberg 2008 investigators had routine access to the patient notes which contained the allocation data.

Incomplete outcome data

Only one study adequately addressed incomplete outcome data. Ross 2004 carried out a repeated measures analysis to account for missing participants across all relevant outcomes. The remaining studies featured some incomplete outcome data that was judged to introduce bias into the studies. This mostly concerned response rates to questionnaires, whereby non‐responders were not described or investigated. In Bergmo 2009 the response rate to the post‐intervention questionnaire was 74%, In Katz 2003 and Katz 2004 the response rates to the physician surveys were 91% and 71% respectively. In Kummervold 2004 the response rate to the patient survey was 93% in the intervention group and 73% in the control group, and for the willingness to pay element of the questionnaire the response rate was 68% for the intervention group and 84% for the control group. In Stalberg 2008 the response rate to the post‐operative feedback questionnaire, which addressed the patient satisfaction outcome, was 76% for the intervention group and 77% for the control group. Lin 2005 did investigate non‐responders, comparing overall satisfaction with care (as per the baseline survey) between participants who completed the study and those who did not (those participants lost to follow up along with those who did not complete final survey). Those not completing were less satisfied on the baseline survey, and this difference was significant. Therefore the least satisfied participants were not in the final analysis and this will have biased the final overall result.

The majority of studies did not carry out an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis, or it was not clear if one had been carried out. MacKinnon 1995; Katz 2003; Katz 2004 did not carry out an ITT analysis. Despite stating that they would be carrying out a 'modified ITT,' in Digenio 2009 data are presented for the completers in the study only. In Stalberg 2008 an ITT analysis could not be completed for the patient satisfaction outcome as not all patients proceeded to surgery, and thus could not complete the post‐operative questionnaire. Bergmo 2009 provided insufficient information to assess whether an ITT analysis was carried out.

Other incidences of incomplete outcome data include Bergmo 2009 not stating how many participants were assessed for severity of eczema, and Katz 2003 and Katz 2004 imputing missing values to zero for the email volume outcome, stating that this was to account for incomplete data, but using zero meant that this served to enable analysis and did not account for the missing data. In MacKinnon 1995, for the outcome ‘number of independent contacts’ the method of contact was recorded for only 24 of 32 contacts. Upon contact the authors stated that this was because clinicians did not specify this information on the contact forms they were required to complete for the purposes of the study.

Selective reporting

Only one study had a published trial protocol (Digenio 2009).

Four studies were judged to have selective outcome reporting. In Bergmo 2009, the results for the primary outcomes are presented as mean values for the whole sample before the intervention versus the whole sample at the end of the intervention, rather than for the intervention and control groups independently. Selective reporting of data was confirmed during contact with the author. Digenio 2009 presents a post‐hoc analysis of two measures (proportions of participants achieving 5% and 10% weight loss) that was not pre‐specified. The study report also states that self‐reported data collected through the website would be descriptively summarised (collection of this descriptive data was not pre‐specified in the protocol) but for two measures (steps per day and calories per day) the data were not presented nor mentioned in the results section. Lin 2005 introduced an additional group to the study analysis: intervention non‐user. This group was compared to both the intervention and control groups. This addition was not pre‐specified. The content of messages was analysed according to two sub‐groups (clinical phone messages and clinical portal messages), and these groups constituted only around half of the originally randomised participants in each group. Therefore we were unable to use these data. 'Value to patient' data were presented for the whole sample and not by group, and the study author informed us that this was because they deemed this outcome as a peripheral part of the study. Whilst Ross 2004 addressed all outcomes in the results section this was sometimes in the form of a P‐value alone, with no other values presented. Categories of messages are presented graphically for the whole sample but not by group, despite the text stating that there were significant differences between the groups.

Other potential sources of bias

Six studies were assessed as having a high risk of other sources of bias. These included potential issues with the reliability of measures (MacKinnon 1995; Kummervold 2004; Stalberg 2008; Bergmo 2009; Digenio 2009), recall bias (Bergmo 2009) and participant bias (Lin 2005) amongst other sources (Characteristics of included studies).

In Digenio 2009 the study authors were all employees of a pharmaceutical company (Pfizer) that funded the research and this represents a conflict of interest in their conducting the research.

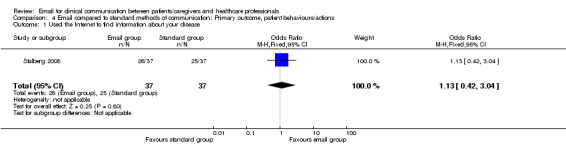

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

We present data for primary outcomes for each comparison in turn, and then secondary outcomes. Table 1; Table 2; and Table 3 present a summary of the results of the primary outcome measures.

Email compared to standard methods of communication: primary outcomes

Healthcare professional outcomes

No primary healthcare professional outcomes were reported.

Patient/caregiver outcomes

Patient's understanding

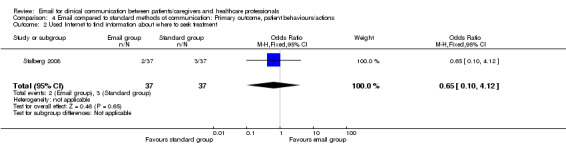

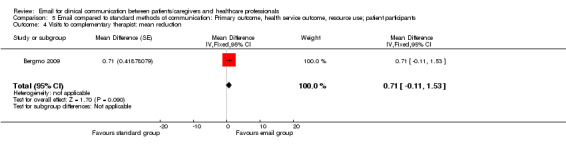

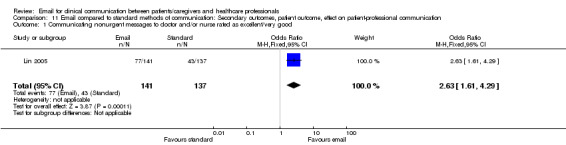

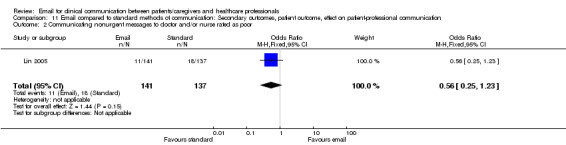

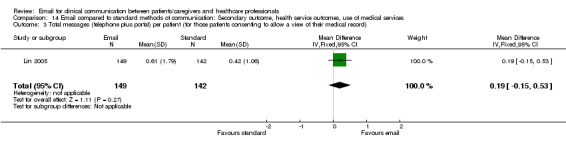

It is not possible to adequately assess whether email has any effect on a patient's understanding when compared with standard methods of communication, due to missing data. Stalberg 2008 examined understanding of post‐operative instructions using a rating scale (1 to 7). A higher score indicated a more favourable outcome. Mean values were the same for email and standard groups (rating 6.1) but an effect estimate could not be calculated (Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Email compared to standard methods of communication: Primary outcome, patient understanding:, Outcome 1 How did communication with the surgeon affect your understanding of postoperative instructions? (Scale 1‐7).

| How did communication with the surgeon affect your understanding of postoperative instructions? (Scale 1‐7) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Email group (mean) | Email group (Total) | Standard group (mean) | Standard group (total) |

| Stalberg 2008 | 6.1 | 37 | 6.1 | 37 |

Patient health status and wellbeing

It is not possible to adequately assess whether email has any effect on a patient's health status and wellbeing when compared with standard methods of communication, due to missing data. Stalberg 2008 examined anxiety level on the day of operation using a rating scale (1 to 7). They reported a 0.4 difference in mean values between email (rating 4.3) and standard method (rating 4.7) groups, but an effect estimate could not be calculated (Analysis 2.1). Bergmo 2009 examined severity of eczema. The authors described no significant interaction between email and standard method groups for severity of asthma but did not present any values. Study authors were unable to provide these data.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Email compared to standard methods of communication: Primary outcome, patient health status and wellbeing, Outcome 1 How did communication with the surgeon affect your anxiety level on the day of the operation? (Scale 1‐7).

| How did communication with the surgeon affect your anxiety level on the day of the operation? (Scale 1‐7) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Email group (mean) | Email group (total) | Standard group (mean) | Standard group (total) |

| Stalberg 2008 | 4.3 | 37 | 4.7 | 37 |

Patient/caregiver views

It is not possible to adequately assess whether email had any effect on a patient/caregiver's views when compared with standard methods of communication, due to missing data. Stalberg 2008 examined whether ‘questions and concerns were addressed in a satisfactory manner,’ ‘how communication with the surgeon affected sense of preparedness for the operation’ and ‘how communication with the surgeon affected sense that the surgeon was available to deal with any problems that might arise using a rating scale (1 to 7). They reported little difference in mean values between email and standard groups for all three measures but an effect estimate could not be calculated. (Analysis 3.1; Analysis 3.2; Analysis 3.3). MacKinnon 1995 reported mean satisfaction ratings for ‘requests and questions dealt with in a timely manner’ and ‘problems dealt with adequately,’ using a rating scale (1 to 5). A higher score indicated a more favourable outcome. They reported little difference in mean values between email and standard groups however an effect estimate could not be calculated (Analysis 3.4; Analysis 3.5).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Email compared to standard methods of communication: Primary outcome, patient/caregiver views, Outcome 1 How did communication with the surgeon affect your sense of preparedness for the operation (Scale 1‐7).

| How did communication with the surgeon affect your sense of preparedness for the operation (Scale 1‐7) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Email group (mean) | Email group (total) | Standard group (mean) | Standard group (total) |

| Stalberg 2008 | 6.2 | 37 | 6.4 | 37 |

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Email compared to standard methods of communication: Primary outcome, patient/caregiver views, Outcome 2 Questions and concerns addressed in a satisfactory manner? (Scale 1‐7).

| Questions and concerns addressed in a satisfactory manner? (Scale 1‐7) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Email group (mean) | Email group (total) | Standard group (mean) | Standard group (total) |

| Stalberg 2008 | 6.4 | 37 | 6.3 | 37 |

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Email compared to standard methods of communication: Primary outcome, patient/caregiver views, Outcome 3 How did communication with the surgeon affect your sense that the surgeon was available to deal with any problems that might arise? (Scale 1‐7).

| How did communication with the surgeon affect your sense that the surgeon was available to deal with any problems that might arise? (Scale 1‐7) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Email group (mean) | Email group (total) | Standard group (mean) | Standard group (total) |

| Stalberg 2008 | 6 | 37 | 6.4 | 37 |

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Email compared to standard methods of communication: Primary outcome, patient/caregiver views, Outcome 4 Requests and questions dealt with in a timely manner (satisfaction rating at 6 months) (Scale 1‐5).

| Requests and questions dealt with in a timely manner (satisfaction rating at 6 months) (Scale 1‐5) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Email group (mean) | Email group (total) | Standard group (mean) | Standard group (total) |

| MacKinnon 1995 | 4 | 7 | 3.3 | 9 |

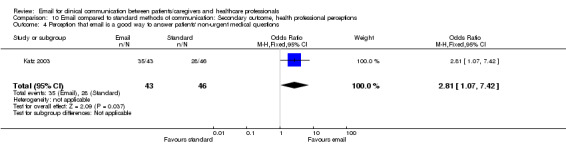

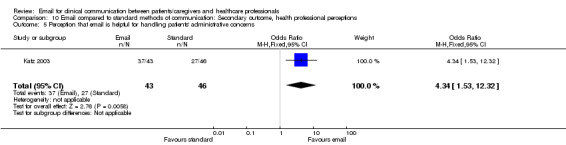

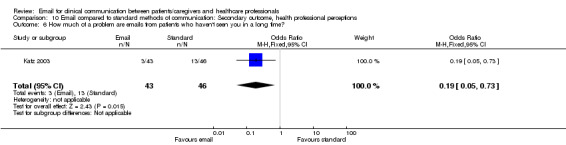

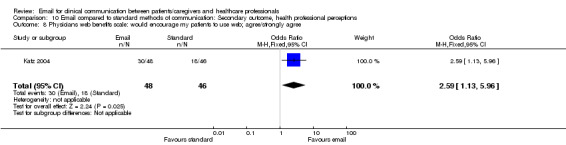

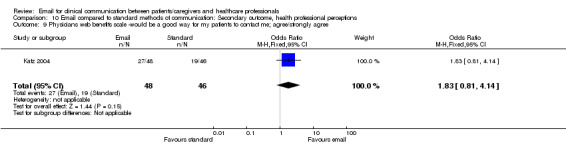

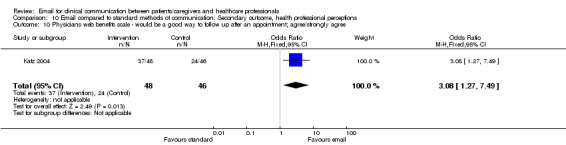

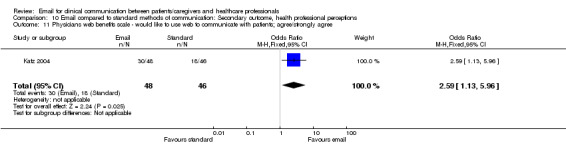

3.5. Analysis.