Abstract

The rs72613567:TA polymorphism in 17-beta hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 13 (HSD17B13) has been found to reduce the progression from steatosis to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH). In this study, we sought to define the pathogenic role of HSD17B13 in triggering liver inflammation. Here, we demonstrate that HSD17B13 forms liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS) around lipid droplets in the livers of MASH patients. The dimerization of HSD17B13 supports the LLPS formation and promotes its enzymatic function. HSD17B13 LLPS increases the biosynthesis of platelet activating factor (PAF), which in turn promotes fibrinogen synthesis and leukocyte adhesion. Blockade of the PAF receptor or STAT3 pathway inhibits the fibrinogen synthesis and leukocyte adhesion. Importantly, adeno-associated viral-mediated xeno-expression of human HSD17B13 exacerbates western diet/carbon tetrachloride-induced liver inflammation in Hsd17b13−/− mice. In conclusion, our results suggest that HSD17B13 LLPS triggers liver inflammation by promoting PAF-mediated leukocyte adhesion, and targeting HSD17B13 phase transition could be a promising therapeutic approach for treating hepatic inflammation in chronic liver disease.

Keywords: 17-beta hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 13, liquid–liquid phase separation, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, liver inflammation, platelet activating factor, fibrinogen synthesis

Introduction

Metabolic associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) is a prevalent metabolic syndrome worldwide (Byrne and Targher, 2015; Abdelmalek, 2021). Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) is a progressive form of MAFLD, characterized by chronic inflammation and fibrosis in liver tissue (Younossi et al., 2018; Sheka et al., 2020). Leukocyte adhesion to liver sinusoidal endothelial cells is a critical step in initiating hepatic inflammation in MASH (Volpes et al., 1992; Ibrahim, 2021). Fibrinogen, primarily expressed in hepatocytes, bridges leukocytes and endothelial cells to promote leukocyte adhesion (Khandoga et al., 2002). The significant impact of fibrinogen levels on disease outcomes and the promising therapeutic potential of targeting fibrinogen have spurred interest in understanding the mechanisms regulating fibrinogen synthesis.

Polymorphisms rs72613567:TA, rs62305723, and rs6834314 in 17-beta hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 13 (HSD17B13) have been shown to confer protection from liver inflammation in chronic liver disease (Abul-Husn et al., 2018; Luukkonen et al., 2020). The rs72613567:TA allele generates an alternative transcript encoding a truncated isoform (isoform D) that lacks enzymatic function (Abul-Husn et al., 2018). However, murine Hsd17b13 deficiency did not protect against liver inflammation induced by an obesogenic diet in mice (Ma et al., 2021), indicating possible interspecies differences in HSD17B13. As a metabolic enzyme, HSD17B13 regulates lipid accumulation and pyrimidine catabolism (Su et al., 2014, 2022; Luukkonen et al., 2023). The specific mechanism by which human HSD17B13 may regulate inflammation through metabolic enzyme activity remains unclear.

In this study, we found that HSD17B13 liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS) in the liver of MASH patients increases the platelet activating factor (PAF) biosynthesis, promoting fibrinogen expression and leukocyte adhesion. Additionally, adeno-associated viral (AAV)-mediated xeno-expression of human HSD17B13 exacerbated western diet/carbon tetrachloride (WD/CCl4)-induced liver inflammation in Hsd17b13−/− mice. Overall, our findings indicate that HSD17B13 LLPS contributes to inflammation in chronic liver disease by inducing PAF-mediated leukocyte adhesion.

Results

HSD17B13 homodimer forms LLPS in the liver of MASH patients

An increase of HSD17B13 expression was observed in MAFLD patients with homozygous carriage of HSD17B13 rs72613567:T (T/T) or rs72613567:TA insertion variant allele (T/TA) (Figure 1A). In the liver of MASH patients, HSD17B13 accumulated and generated puncta in hepatocytes (Figure 1B). No solid protein aggregates were detected in the HSD17B13 puncta (Supplementary Figure S1A), suggesting that HSD17B13 in the puncta was in a soluble state. HSD17B13 is capable of forming homodimers (Supplementary Figure S1B; Ma et al., 2020). The bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assay (Don et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2022) was used to detect the presence of HSD17B13 homodimers in living cells (Figure 1C). The majority of HSD17B13 homodimers formed distinctive puncta that spontaneously fused into larger puncta around the nucleus (Figure 1D and E, solid arrow). Only a limited quantity of HSD17B13 homodimers were found to be localized on lipid droplets (LDs) (Figure 1D, hollow arrow). Intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) drive proteins to form LLPS (Martin and Holehouse, 2020; Tsang et al., 2020). The sequence of amino acids 1–27 of HSD17B13 was predicted as an IDR (Supplementary Figure S1C). The fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) assay showed that the fluorescence of HSD17B13 homodimer puncta recovered within minutes after photobleaching (Figure 1F). Purified HSD17B13 in different concentrations of NaCl buffers showed increased turbidity over time (Supplementary Figure S1D). Truncation of the IDR of HSD17B13 (amino acids 1–27) abolished the puncta formation in cells and caused a decrease in the turbidity over time (Figure 1G; Supplementary Figure S1D). The IDR truncation also reduced HSD17B13 enzyme activity (Figure 1H). These data suggest that dimerization of HSD17B13 promotes LLPS formation and governs its catalytic activity.

Figure 1.

HSD17B13 LLPS is observed in the liver of MASH patients and regulates enzymatic function. (A) Western blot analysis of HSD17B13 protein expression in the liver tissues of healthy and MAFLD patients. Homozygous carriage of HSD17B13 rs72613567:T represents WT (T/T); HSD17B13 rs72613567:TA insertion variant allele gives heterozygotes (T/TA) and homozygotes (TA/TA). (B) Immunohistofluorescence analysis of HSD17B13 expression in liver samples from healthy individuals and MASH. Scale bar, 25 μm. (C) Schematic diagram for illustrating the work model of BiFC-HSD17B13. (D) Analysis of the subcellular location of HSD17B13 homodimers in HeLa cells by BiFC. LDs were labeled with LipidTOX. Solid arrows showed that BiFC-HSD17B13 strongly presented around LDs; hollow arrows showed that BiFC weakly presented on LDs. Scale bar, 10 μm. (E) Time-lapse analysis of the dynamic behavior of HSD17B13. Scale bar, 10 μm. (F) FRAP analysis of HSD17B13 homodimers in HeLa cells by BiFC, with boxes indicating the bleached area. (G) Protein diagram of full-length and truncated BiFC-HSD17B13 is shown above, with gray areas indicating the IDRs. Images below show full-length and truncated BiFC-HSD17B13. Scale bar, 20 μm. (H) Enzymatic activity of full-length and truncated HSD17B13. Data are presented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 determined by student's unpaired t-test.

Human but not mouse HSD17B13 promotes fibrinogen synthesis and leukocyte adhesion

To investigate the function of HSD17B13 LLPS in hepatocytes, we expressed human HSD17B13 in HepaRG cells, as HSD17B13 expression levels are low in multiple liver cell lines (Supplementary Figure S2). RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis indicated that human HSD17B13 expression altered 346 genes, including 116 upregulated and 230 downregulated genes (Figure 2A). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) revealed that hemostasis-related process was enriched in the HSD17B13-overexpressing group (Figure 2B). The top 28 differentially expressed genes enriched in hemostasis and cell adhesion processes are shown in Figure 2C. Fibrinogen promotes platelet and inflammatory cell accumulation at the injury site of blood vessels, which is critical for initiating tissue inflammation (Luyendyk et al., 2019). We found that HSD17B13 increased fibrinogen expression in HepaRG cells, with FGG, FGA, and FGB coding for fibrinogen gamma, alpha, and beta chains, respectively (Figure 2D). Pearson correlation analysis showed a positive correlation between hepatic HSD17B13 and fibrinogen mRNA expression levels in MAFLD patients (Figure 2E–G). We also found that human HSD17B13 promoted leukocyte adhesion in vitro (Figure 2H). Mouse HSD17B13 shares 82% protein similarity with the human version. IDR score of mouse HSD17B13 is predicted comparable to that of human HSD17B13, suggesting that mouse HSD17B13 may also form LLPS (Supplementary Figure S1C). However, mouse HSD17B13 did not promote leukocyte adhesion and fibrinogen expression in hepatocytes (Figure 3A–E). In addition, HSD17B13 as a hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase regulates sterol metabolism (Su et al., 2019). Mutation of human HSD17B13 with deficient enzyme activity and HSD17B13Δ1–27 failed to promote fibrinogen expression and leukocyte adhesion (Figure 3F–I). These data suggest that metabolites regulated by human HSD17B13 enzyme activity may play a role in HSD17B13-mediated leukocyte adhesion.

Figure 2.

Human HSD17B13 promotes fibrinogen expression and leukocyte adhesion. (A) Volcano plot of the distributed genes with statistical significance and fold change (P < 0.05 and |log2(fold change)| ≥ 0.5) in HepaRG cells infected with lenti-HSD17B13 or lenti-vector (n = 3). (B) GSEA of differentially expressed genes identified between the lenti-HSD17B13 and lenti-vector groups enriched in hemostasis pathway. (C) Heatmap of differentially expressed genes related in the hemostasis and cell adhesion pathway (n = 3). (D) FGG, FGA, and FGB mRNA expression levels in HSD17B13-overexpressing HepaRG cells. Data are presented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments. (E–G) Pearson correlation coefficient analysis between mRNA expression levels of HSD17B13 and FGG, FGA, or FGB in human liver samples (n = 50). (H) In vitro adhesion activity analysis for the number of THP-1 cells adhesive to HepaRG cells. The experiment was repeated at least three times, and one representative result is shown. Scale bar, 200 μm. Data are presented as mean ± SD of 30 fields calculated in each group. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 determined by student's unpaired t-test.

Figure 3.

Human HSD17B13, but not mouse HSD17B13, promotes fibrinogen expression and leukocyte adhesion in an enzymatic activity-dependent manner. (A) Protein sequence alignment between human and mouse HSD17B13. (B–E) HepaRG cells were transfected to overexpress human or mouse HSD17B13. (F–I) HepaRG cells were transfected to overexpress full-length, truncated (Δ1–27), or mutant (Y54F, K58Q, Y185F, and K189Q) human HSD17B13. (B and F) The number of THP-1 cells adhesive to HepaRG cells. The experiment was repeated at least three times, and one representative result is shown. Data are presented as mean ± SD of 30 fields calculated in each group. (C–E and G–I) FGG, FGA, and FGB mRNA expression levels in HepaRG cells. Data are presented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments. All groups were compared to the control group. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and not significant (NS) determined by one-way ANOVA analysis followed by Tukey's test.

Human HSD17B13 promotes PAF biosynthesis

To determine the critical metabolite for HSD17B13-mediated leukocyte adhesion, we applied mass spectrometry (MS)-based metabolomic analysis. PAF was discovered as the most upregulated metabolite induced by HSD17B13 (Figure 4A). Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis (Kanehisa and Goto, 2000) revealed that differentially expressed metabolites were enriched in the choline metabolism and glycerophospholipid metabolism pathways (Figure 4B). Levels of glycerol 3-phosphate, choline, and cytidine monophosphate were upregulated in HSD17B13-overexpressing hepatocytes (Figure 4C). These metabolites are involved in the de novo pathway for PAF biosynthesis (Figure 4D and E). Thus, our results indicate that HSD17B13 promotes PAF biosynthesis.

Figure 4.

Human HSD17B13 promotes the biosynthesis of choline and PAF. (A) Volcano plot of nontarget metabolomics in the positive ion model identified 503 metabolites. PAF was one of the most significant changed metabolites. (B) KEGG pathway analysis of differential levels of metabolites. (C) Differential metabolites related to choline metabolism. (D) Content of PAF in HSD17B13-overexpressing HepaRG cells. Data are presented as mean ± SD of five samples. ***P < 0.001 determined by student's unpaired t-test. (E) Schematic representation of choline and PAF metabolism.

HSD17B13 activates PAF/STAT3 signaling in hepatocytes to promote leukocyte adhesion

PAF binds to its receptor PAFR and activates multiple signaling pathways (Ogbozor et al., 2015; Sharif, 2022). We found that human HSD17B13 promoted STAT3 phosphorylation and FGG mRNA expression (Figure 5A–D; Supplementary Figure S3). A decreasing trend of STAT3 expression was observed in human HSD17B13-overexpressing group (Supplementary Figure S3C). When PAFR/STAT3 signaling was blocked by the PAFR inhibitor BN-52021 or the STAT3 inhibitor cryptotanshinone (Zhang et al., 2019), HSD17B13 failed to promote STAT3 phosphorylation and FGG mRNA expression (Figure 5A–D). Consistently, both BN-52021 and cryptotanshinone blocked human HSD17B13-induced leukocyte adhesion (Figure 5E). Furthermore, PAF addition increased fibrinogen expression and leukocyte adhesion in HepaRG cells (Figure 5F and G). These data suggest that human HSD17B13-induced autocrine PAF/STAT3 signaling promotes the fibrinogen synthesis and leukocyte adhesion.

Figure 5.

Human HSD17B13 promotes leukocyte adhesion via PAF autocrine. (A–E) HepaRG cells overexpressing HSD17B13 or control were treated with BN-2521 (10 μM) or cryptotanshinone (10 μM) for 12 h. (A and C) Western blot analysis of p-STAT3 and STAT3 protein expression levels. (B and D) Quantitative PCR analysis of FGG mRNA expression levels. (E) The number of THP-1 cells adhesive to HepaRG cells. (F and G) HepaRG cells were treated with or without 50 nM PAF for 24 h. (F) The number of THP-1 cells adhesive to HepaRG cells. (G) FGG, FGA, and FGB mRNA expression levels in HepaRG cells. (A–D and G) Data are presented as mean ± SD of three independent samples. (E and F) The experiment was repeated at least three times, and one representative result is shown. Data are presented as mean ± SD of 30 fields calculated in each group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and not significant (NS) determined by one-way ANOVA analysis followed by Tukey's test.

Human HSD17B13 exacerbates liver inflammation in WD/CCl4-treated mice

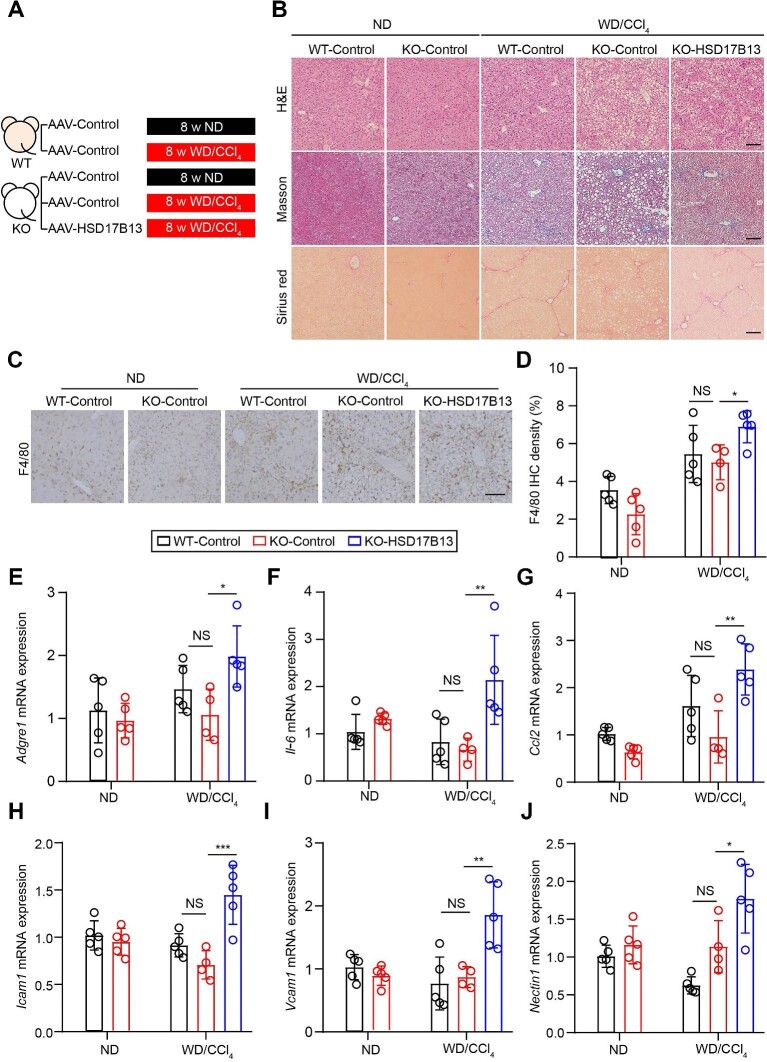

Hsd17b13−/− mice were generated to investigate the role of human HSD17B13 in liver inflammation (Supplementary Figure S4). Human HSD17B13 was xeno-expressed in the liver of Hsd17b13−/− mice by AAV. The xeno-expression of human HSD17B13 promoted inflammatory and fibrinolysis gene expression in hepatocytes isolated from Hsd17b13−/− mice (Supplementary Figure S5), consistent with the in vitro results. Human HSD17B13 is considered to retain its enzymatic activity in mouse, as hepatic Fgg expression in human HSD17B13-overexpressing Hsd17b13−/− mice was inhibited after treatment with BN-52021 (Supplementary Figure S6). These mice were challenged with eight weeks of WD/CCl4 to establish a murine MASH model (Figure 6A). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining showed macrovesicular or microvesicular steatosis and the infiltration of inflammatory cells in liver sections from WD/CCl4-treated mice (Figure 6B). Masson and Sirius red staining showed an increase in collagen deposition in WD/CCl4-treated mice. Consistent with a previous study, Hsd17b13 deficiency did not improve liver inflammation or fibrosis (Figure 6B–J). F4/80 is a surface biomarker of macrophages. F4/80 immunohistochemistry (IHC) showed that xeno-expression of human HSD17B13 increased macrophage cell infiltration in the liver of WD/CCl4-treated mice (Figure 6C and D). The mRNA expression levels of inflammatory genes Il-6 and Ccl2 and cell adhesion-related genes Icam1, Vcam1, and Nectin1 (Zhong et al., 2018) were all upregulated by the xeno-expression of human HSD17B13 (Figure 6E–J). Futhermore, xeno-expressing human HSD17B13 also upregulated serum aspartate aminotransferase and hepatic hydroxyproline levels in WD/CCl4-treated mice (Supplementary Figure S7). These data suggest that human HSD17B13 promotes immune cell infiltration and liver inflammation in vivo. HSD17B13 rs72613567:TA mutation generates a loss-of-function isoform D with a truncation of amino acids 271–300 (Abul-Husn et al., 2018). The protein sequence of amino acids 269–286 of HSD17B13 was predicted as an IDR (Supplementary Figure S1C). Consistently, the isoform D of HSD17B13 hardly formed LLPS (Supplementary Figure S8A). Xeno-expression of isoform D in the liver was not able to promote liver inflammation in WD/CCl4-treated mice (Supplementary Figure S8B–G).

Figure 6.

Human HSD17B13 initiates liver inflammation in WD/CCl4-treated mice. (A) Schematic overview of the in vivo experiment (n = 4–5 mice in each group). (B) Representative images of H&E, Sirius red, and Masson staining. Scale bar, 100 μm. (C and D) Representative images and quantitative analysis of F4/80 IHC in mice. Scale bar, 100 μm. (E–J) mRNA expression levels of inflammatory-related genes F4/80, Il-6, and Ccl2 and adhesion-related genes Icam1, Vcam1, and Nectin1. KO group represents Hsd17b13−/− mouse group, which was compared with the wide-type mouse (WT) group. Data are presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and not significant (NS) determined by one-way ANOVA analysis followed by Tukey's test. ND, normal chow diet.

Discussion

HSD17B13 is a promising target for the treatment of MAFLD (Dong, 2020). We report that HSD17B13 LLPS is a distinctive morphological configuration in the liver of MASH patients. Dimerization of HSD17B13 facilitates the LLPS formation and induces autocrine PAF/STAT3 signaling-mediated leukocyte adhesion (Figure 7). This study also indicates a species-specific role of human HSD17B13 in promoting chronic liver inflammation.

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of the roles of HSD17B13 LLPS in triggering liver inflammation. HSD17B13 homodimers form LLPS and support the enzymatic function. HSD17B13 promotes the de novo biosynthesis of PAF that activates the PAFR/STAT3 pathway to promote fibrinogen expression. The increased fibrinogen expression in hepatocytes further increases leukocyte adhesion and triggers liver inflammation.

HSD17B13 homodimers form LLPS and regulate enzyme activity, raising an interesting question of how LLPS promotes the enzymatic function of HSD17B13. As a biomolecular condensate, LLPS regulates many biological processes (Boeynaems et al., 2018; Alberti et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2020) and can serve as the reaction crucible, effectively concentrating enzymes and substrates, thereby enhancing substrate turnover rates (O'Flynn and Mittag, 2021; Ilık and Aktaş, 2022). Here, we observed that HSD17B13 homodimers formed LLPS around LDs with a perinuclear distribution, which may facilitate the transportation of substrates/products from other organelles. We hypothesize that HSD17B13 LLPS provides a highly favorable environment for catalytic activity to occur. The specific mechanism needs further investigation. There are 56 different amino acids between human and mouse HSD17B13 proteins. These different amino acids are distributed across multiple protein domains, such as the membrane anchoring region, dimerization region, and kinase domain. The different amino acids in the kinase domain may affect substrate type and enzymatic activity, which could be one reason for the different functions of human and mouse HSD17B13. Besides, HSD17B11, a hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, shows high similarity to HSD17B13. HSD17B11 and HSD17B13 are both located in LDs and recognize similar substrates, implying that HSD17B11 may compensate some functions of HSD17B13.

The de novo and remodeling pathways are two classic metabolic pathways for PAF biosynthesis (Reznichenko and Korstanje, 2015; Shindou et al., 2000). Arachidonic acid and its derivatives are involved in the production of PAF (Nigam and Schewe, 2000). However, the levels of prostaglandin B2, prostaglandin F2α, and 18-carboxy dinor leukotriene B4 were not altered by human HSD17B13 (Supplementary Figure S9). We then focused on the de novo pathway of HSD17B13-induced PAF production in hepatocytes. CDP-choline is involved in both biosynthetic pathways of choline and PAF (Heller et al., 1991; Fagone and Jackowski, 2013). The level of CDP-choline was downregulated by HSD17B13 (Figure 4E), suggesting that HSD17B13 may regulate the transformation of CDP-choline to promote PAF and phosphatidylcholine (PC) biosynthesis.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates the species-specific pathogenic role of HSD17B13 in trigging liver inflammation by promoting leukocyte adhesion. Our findings indicate that the formation of LLPS by HSD17B13 homodimers could function as an essential process in the development of chronic liver disease and thus targeting HSD17B13 LLPS may be a promising approach for treating liver inflammation in chronic liver disease.

Materials and methods

Patients

The human liver samples used in this study were obtained from the Affiliated Drum Tower Hospital of Nanjing University Medical School. Normal liver samples from patients receiving surgery for hepatic hemangioma were collected. Liver samples from MAFLD and MASH patients undergoing diagnostic needle biopsies were collected. Each group included 20 samples. Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants in the study. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committees of the Affiliated Drum Tower Hospital of Nanjing University Medical School (no. 2019-257-01) and was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

Cell culture

HepaRG cells were purchased from BeNa Culture Collection (Beijing; BNCC340037). HEK293T, HeLa, and THP-1 cells were purchased from the National Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures (Shanghai; no. SCSP-502, no. SCSP-504, and no. SCSP-567, respectively). HepaRG cells were cultured in William's E medium (Gibco, A1217601) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Vivacell, C04001-500), 2 mM GlutaMax (Gibco, 35050061), and 5 μg/ml insulin (Beyotime Biotechnology, P3376-100IU). HEK293T and HeLa cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM; KeyGEN, KGM12800N-500) supplemented with 10% FBS.

BiFC

Human HSD17B13 and its variants were fused with 173 N-terminal amino acids (N173) or 155 C-terminal amino acids (C155) in VENUS protein and cloned into pcDNA3.4(+) vector. Expression plasmids were constructed by GenScript. Plasmids with N173 and C155 were transfected into cells at a ratio of 1:1 by using Lipo3000 (Invitrogen, L3000015). Cells were then treated as indicated and assessed accordingly.

Immunohistofluorescence

Human liver samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), and dehydrated, embedded in paraffin. Sections were permeabilized with 0.5% TritonX-100 (Merck, T8787-100ML) and stained with antibodies for Collagen I and HSD17B13. After staining with secondary antibodies and DAPI (Beyotime Biotechnology, C1005), images of sections were captured by a fluorescent confocal microscopy system (Leica TCS SP8-MP). The information of antibodies is listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Immunocytofluorescence

HeLa cells were seeded on glass coverslips in 2-cm2 wells before BiFC plasmid transfection. After 24 h treatment, cells were fixed with 4% PFA and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100. After staining with the antibody for HSD17B13 (Origene, TA814158) overnight, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and stained with secondary antibody for 2 h. Cells were stained with LipidTOX (Thermo Fisher Scientific, H34476) and DAPI for 20 min. Cells were then washed with PBS and imaged with Leica TCS SP8-MP. The antibody information is listed in Supplementary Table S1.

FRAP

The FRAP assay was performed using the FRAP module of the Zeiss LSM 880 (Zeiss) as reported (Zhu et al., 2020). Cells transfected with BiFC plasmids were bleached using a 488-nm laser beam within a circular region of interest and time-lapse images were acquired. Fluorescence intensity was measured using ZEISS Zen lite (Zeiss).

Expression and purification of HSD17B13

The recombinant human full-length and truncated (Δ1–27) HSD17B13 proteins were generated via heterologous expression using pET vectors and Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells. A 6×His-tag and a tobacco etch virus protease cleavage site were included in the C-terminus of proteins. The protein purification process was carried out by affinity chromatography (Ni-NTA column) (Smart-Lifesciences Biotechnology, SA004025) and size exclusion chromatography (General Electric Company, 28-9893-32). The eluant buffer contained 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0) and 500 mM NaCl (Nanjing Reagent company, 7647-14-5).

Detection of HSD17B13 enzyme activity

The HSD17B13 enzyme activity was measured by NADH-Glo Detection kit (Promega, G9061). Briefly, 10 μl PBS containing 500 μM NAD+ (Bidepharm, BD126917), 15 μM β-estradiol (MCE, HY-B0141) (with 0.05% DMSO), and 300 ng recombinant human HSD17B13 protein was added into each well of a 384-well plate. Then, an equal volume of luciferase reagent was added. After 1 h incubation, the plate was scanned at 450 nm using a multi-mode plate reader (Tecan).

RNA-seq and analysis

Total RNA from the control or HSD17B13-overexpressing HepaRG cells were extracted using the TRIzol method. The RNA Nano 6000 Assay Kit (Agilent Technologies) was used to determine the RNA integrity. The cDNA library was prepared and transcriptome sequencing was performed in the Novogene Laboratories using an Illumina Novaseq platform. Reads were aligned to the human reference genome using Hisat2 v2.0.5. The read numbers mapped to each gene were counted using feature Counts v1.5.0-p3. The DESeq2 R package was used as a differential gene expression analysis. The RNA-seq data are deposited in NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) with the accession number GSE238060.

Cell adhesion analysis

HepaRG cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 5 × 105 cells per well. After 12 h, THP-1 cells were stained with 2 μg/ml Hoechst 33342 (Beyotime, C1028) for 20 min, washed twice with PBS, and added to HepaRG cells at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well. The cells were co-cultured at 37°C for 30 min, washed twice with PBS, and then imaged with Olympus microscope (IX51).

Plasmid transfection

pcDNA3.1(+)-3×Flag vectors containing expression cassettes for full-length, truncated (Δ1–27), or mutant (Y54F, K58Q, Y185F, and K189Q) HSD17B13 were purchased from GenScript. Vectors were introduced into HepaRG cells using Lipo3000 according to the manufacturer's instructions. The transfected cells were maintained in the culture medium for 48 h before treatment or sample preparation.

Lentiviral vector construction and production

For lentiviral vector construction, lentiviral vectors were generated using the pLVX-IRES-mCherry vector (TaKaRa, 631237), as described previously (Kueh et al., 2013). Human or mouse cDNAs were cloned into this vector under the CMV promoter. For lentivirus production, the pLVX-IRES-mCherry vector was co-transfected with psPAX2 (Addgene, 12260) and pMD2.G (Addgene, 12259) into HEK293T cells by PEI (YEASEN, 40815ES03) to produce infectious lentiviral particles. Briefly, HEK293T cells were seeded in a 10-cm dish to grow until 70% confluency before transfection. Chloroquine (25 mM) (YEASEN, 53755ES60) was added to the culture the following day. Plasmids (psPAX2:pMD2.G:pLVX-h/mHSD17B13-IRES-mCherry = 5:3:2) were mixed with PEI and added into dishes. Medium containing lentivirus was collected twice at 24 h and 48 h post transfection into a 50-ml tube (stored at 4°C). Collected medium was passed through a 0.45-μm filter and mixed with 5× PEG8000 (YEASEN, 60304ES76). After 12 h incubation at 4°C, lentivirus was collected by centrifugation at 3000× g for 25 min. Pellets were resuspended in DMEM at −80°C.

MS-based metabolomic analysis

Metabolites were extracted from HepaRG cells transfected with HSD17B13 expression or control vector with 1 ml cold methyl alcohol/acetonitrile/water (2:2:1) for 1 × 107 cells/sample. After vertexing, ultrasonic treatment, and centrifugation, extracted molecules in both aqueous layers were combined and dried in vacuo. Chromatographic separation was performed on an Agilent 1290 Infinity LC system equipped with AB SCIEX Triple TOF 6600 System. A 100 × 2.1 mm inner diameter, 1.7-μm particle size Amide C18 column (Waters, 186002344) was used for all experiments. Separation conditions were: solvent A, 25 mM ammonium acetate (Sigma, 73594) and 25 mM ammonium hydroxide (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 14923); solvent B, acetonitrile (Merck, 34851); separation gradient, initially 95% B, then linear to 40% B in 8.5 min, maintained at 40% B for 0.1 min, and then linear to 90% B in 3.9 min; flow rate, 0.2 ml/min; injection volume, 2 μl; autosampler temperature, 25°C; and column temperature, 25°C. MS analysis was carried out on AB SCIEX Triple TOF 6600 System equipped with an electrospray ionization source operating in positive/negative switching mode. The detector was run in full scan MS analysis under the following conditions: spray voltage, 5.5 kV; capillary temperature, 600°C; sheath gas, 60 (arbitrary units); auxiliary gas, 60 (arbitrary units); primary m/z range, 60–1000 Da; and secondary m/z range, 25–1000 Da. The raw MS data were converted to MzXML files using Proteo Wizard MS Convert before importing into freely available XCMS software (Scripps Center for Metabolomics). For peak picking, the following parameters were used: cent wave m/z = 10 ppm, peak width = c (10, 60), and prefilter = c (10, 100). For peak grouping, bw = 5, mzwid = 0.025, and min frac = 0.5 were used. Collection of Algorithms for MEtabolite pRofile Annotation (Georgetown University) was used for annotation of isotopes and adducts. Only the variables having >50% of the nonzero measurement values in at least one group were kept. Compound identification of metabolites was performed by comparison of accuracy m/z value (<10 ppm). MS-based metabolomic analysis was performed by Shanghai Applied Protein Technology.

Western blotting

Protein was extracted with radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (Beyotime, P0013B) or cell lysis buffer (Beyotime, P0013). Protein samples were denaturized under 95°C after quantitated with BCA assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 23225). After the preparation of samples, 20–40 μg of protein was subjected to 5% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore). After blocking with 5% skimmed milk for 1 h, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C. Next day, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature and then scanned using AMERSHAM ImageQuant 800 (Cytiva). The antibodies used for western blotting are described in Supplementary Table S1.

Generation of Hsd17b13−/− mice

Hsd17b13 −/− mice on the C57BL/6N background were generated by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome engineering and purchased from Cyagen Biosciences. Heterozygous mice were crossed with each other and raised at the Animal Center, School of Life Sciences, Nanjing University. The genotypes were identified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using genomic DNA with the following primers: Primer 1 forward, 5′-CTTAGCACTCTACTGCCAACAATG-3′; Primer 1 reverse, 5′-CTGTTTTGAGCTGTGTTGAGGAAAT-3′; and Primer 2 reverse, 5′-TCTCACCTGATCCACAGAGTTGTA-3. C57BL/6N wild-type mice were purchased from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. All in vivo assays were approved by the Animal Care Committee of Nanjing University.

Mouse treatment

Mice were housed in a temperature-controlled environment (22.2°C ± 1.6°C) with a 12-h/12-h light/dark cycle and had free access to water and food. AAV-control and AAV-HSD17B13 were purchased from Hanbio. To introduce human HSD17B13 overexpression in mouse liver cells, 6- to 8-week-old mice were injected intravenously with 100 μl AAV-HSD17B13 (viral titer 1 × 1012 VG/ml) or AAV-control. The mice were then fed a normal chow diet (Jiangsu Xietong Pharmaceutical Bio-engineering Co., Ltd, SWS9102) and normal tap water or a WD (21.1% fat, 41% sucrose, and 1.25% cholesterol by weight) and a high-sugar solution [23.1 g/L D-fructose (Macklin, D809612) and 18.9 g/L D-glucose (Aladdin, G116300)]. Corn oil or CCl4 was injected intra-peritoneally once per week, starting simultaneously with the diet administration. After 8 week treatment, the mice were sacrificed and tissue samples were harvested for further analysis.

Liver histology

Liver tissues from mice were fixed with 4% PFA. Paraffin embedded liver samples were prepared for H&E, Sirius red, and Masson staining. Staining was performed by Servicebio.

IHC

Mouse liver samples were fixed with 4% PFA for 24 h and then dehydrated with the different ethanol (Merck, 100938) concentrations. Paraffin-embedded samples were coronally sectioned (7 μm) and stained with antibodies against F4/80. After washing with PBS three times, the sections were incubated with secondary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature. Immunostaining was performed using a DAB kit (Solarbio, DA1016) and counterstain hematoxylin (Beyotime, C0107). Images were captured by a light microscope (Olympus IX51). The percentage of positive cells was calculated by ImageJ (National Institutes of Health) (Jensen, 2013). Antibody information is listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Reverse transcription–PCR and quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cell or tissue samples with RNAiso Plus (TaKaRa, 9109) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Total RNA (2 μg) was used for reverse transcription to cDNA using a cDNA Synthesis kit (Vazyme, R323-00). PCR was performed for 40 cycles at 94°C for 30 sec, 58°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min (Vazyme, Q712-02). The GAPDH RNA expression was utilized for normalization. mRNA expression was also normalized to control group. Results from three independent experiments, each containing three technique repetition for one sample, were analyzed. Detection and data analysis were executed with Bio-Rad C1000 Touch Thermal Cycler. The primers used for quantitative PCR are described in Supplementary Table S2.

Statistical analysis

Statistical data presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) were evaluated by Student's t-test when only two value sets were compared or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) analysis followed by Tukey's test when the data involved three or more groups. P < 0.05 was considered significant, shown as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Jing Ye, State Key Laboratory of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, School of Life Sciences, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210023, China.

Xiyu Huang, State Key Laboratory of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, School of Life Sciences, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210023, China.

Manman Yuan, State Key Laboratory of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, School of Life Sciences, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210023, China.

Jinglin Wang, Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery, The Affiliated Drum Tower Hospital of Nanjing University Medical School, Hepatobiliary Institute of Nanjing University, Nanjing 210008, China.

Ru Jia, State Key Laboratory of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, School of Life Sciences, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210023, China.

Tianyi Wang, State Key Laboratory of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, School of Life Sciences, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210023, China.

Yang Tan, State Key Laboratory of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, School of Life Sciences, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210023, China.

Shun Zhu, Department of Cellular and Genetic Medicine, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China.

Qiang Xu, State Key Laboratory of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, School of Life Sciences, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210023, China.

Xingxin Wu, State Key Laboratory of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, School of Life Sciences, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210023, China.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82273989, 2193005, 81722047, and 81874317) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (020814380161).

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Author contributions: J.Y.: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, and writing. X.H.: methodology and formal analysis. M.Y.: methodology and formal analysis. J.W.: human sample preparation. R.J.: methodology and formal analysis. T.W.: methodology and formal analysis. Y.T.: software. S.Z.: software. Q.X.: conceptualization. X.W.: conceptualization, methodology, writing, reviewing, and editing.

References

- Abdelmalek M.F. (2021). Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: another leap forward. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 18, 85–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abul-Husn N.S., Cheng X., Li A.H. et al. (2018). A protein-truncating HSD17B13 variant and protection from chronic liver disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 1096–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberti S., Gladfelter A., Mittag T. (2019). Considerations and challenges in studying liquid–liquid phase separation and biomolecular condensates. Cell 176, 419–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeynaems S., Alberti S., Fawzi N.L. et al. (2018). Protein phase separation: a new phase in cell biology. Trends Cell Biol. 28, 420–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne C.D., Targher G. (2015). NAFLD: a multisystem disease. J. Hepatol. 62, S47–S64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M., Sui T., Yang L. et al. (2022). Live imaging of RNA and RNA splicing in mammalian cells via the dcas13a–SunTag-BiFC system. Biosens. Bioelectron. 204, 114074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Don E.K., Maschirow A., Radford R.A.W. et al. (2021). In vivo validation of bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) to investigate aggregate formation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Mol. Neurobiol. 58, 2061–2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X.C. (2020). A closer look at the mysterious HSD17B13. J. Lipid Res. 61, 1361–1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagone P., Jackowski S. (2013). Phosphatidylcholine and the CDP-choline cycle. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1831, 523–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller R., Bussolino F., Ghigo D. et al. (1991). Stimulation of platelet-activating factor synthesis in human endothelial cells by activation of the de novo pathway. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate activates 1-alkyl-2-lyso-sn-glycero-3-phosphate:acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase and dithiothreitol-insensitive 1-alkyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol:CDP-choline cholinephosphotransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 21358–21361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim S.H. (2021). Sinusoidal endotheliopathy in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: therapeutic implications. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 321, G67–G74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilık İ.A., Aktaş T. (2022). Nuclear speckles: dynamic hubs of gene expression regulation. FEBS J. 289, 7234–7245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen E.C. (2013). Quantitative analysis of histological staining and fluorescence using ImageJ. Anat. Rec. 296, 378–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M., Goto S. (2000). KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khandoga A., Biberthaler P., Enders G. et al. (2002). Platelet adhesion mediated by fibrinogen-intercelllular adhesion molecule-1 binding induces tissue injury in the postischemic liver in vivo. Transplantation 74, 681–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kueh H.Y., Champhekar A., Nutt S.L. et al. (2013). Positive feedback between PU.1 and the cell cycle controls myeloid differentiation. Science 341, 670–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luukkonen P.K., Sakuma I., Gaspar R.C. et al. (2023). Inhibition of HSD17B13 protects against liver fibrosis by inhibition of pyrimidine catabolism in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2217543120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luukkonen P.K., Tukiainen T., Juuti A. et al. (2020). Hydroxysteroid 17-β dehydrogenase 13 variant increases phospholipids and protects against fibrosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. JCI Insight 5, e132158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luyendyk J.P., Schoenecker J.G., Flick M.J. (2019). The multifaceted role of fibrinogen in tissue injury and inflammation. Blood 133, 511–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y., Brown P.M., Lin D.D. et al. (2021). 17-Beta hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 13 deficiency does not protect mice from obesogenic diet injury. Hepatology 73, 1701–1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y., Karki S., Brown P.M. et al. (2020). Characterization of essential domains in HSD17B13 for cellular localization and enzymatic activity. J. Lipid Res. 61, 1400–1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin E.W., Holehouse A.S. (2020). Intrinsically disordered protein regions and phase separation: sequence determinants of assembly or lack thereof. Emerg. Top Life Sci. 4, 307–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigam S., Schewe T. (2000). Phospholipase A2s and lipid peroxidation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1488, 167–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Flynn B.G., Mittag T. (2021). The role of liquid–liquid phase separation in regulating enzyme activity. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 69, 70–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogbozor U.D., Opene M., Renteria L.S. et al. (2015). Mechanism by which nuclear factor-kappa beta (NF-κB) regulates ovine fetal pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 4, 11–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reznichenko A., Korstanje R. (2015). The role of platelet-activating factor in mesangial pathophysiology. Am. J. Pathol. 185, 888–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharif N.A. (2022). PAF-induced inflammatory and immuno-allergic ophthalmic diseases and their mitigation with PAF receptor antagonists: cell and nuclear effects. Biofactors 48, 1226–1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheka A.C., Adeyi O., Thompson J. et al. (2020). Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a review. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 323, 1175–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shindou H., Ishii S., Uozumi N. et al. (2000). Roles of cytosolic phospholipase A2 and platelet-activating factor receptor in the Ca-induced biosynthesis of PAF. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 271, 812–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su W., Mao Z., Liu Y. et al. (2019). Role of HSD17B13 in the liver physiology and pathophysiology. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 489, 119–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su W., Wang Y., Jia X. et al. (2014). Comparative proteomic study reveals 17β-HSD13 as a pathogenic protein in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 11437–11442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su W., Wu S., Yang Y. et al. (2022). Phosphorylation of 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 13 at serine 33 attenuates nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. Nat. Commun. 13, 6577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang B., Pritišanac I., Scherer S.W. et al. (2020). Phase separation as a missing mechanism for interpretation of disease mutations. Cell 183, 1742–1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpes R., Van Den Oord J.J., Desmet V.J. (1992). Vascular adhesion molecules in acute and chronic liver inflammation. Hepatology 15, 269–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younossi Z., Anstee Q.M., Marietti M. et al. (2018). Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 15, 11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Ji X., Li P. et al. (2020). Liquid–liquid phase separation in biology: mechanisms, physiological functions and human diseases. Sci. China Life Sci. 63, 953–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Lu W., Zhang X. et al. (2019). Cryptotanshinone protects against pulmonary fibrosis through inhibiting Smad and STAT3 signaling pathways. Pharmacol. Res. 147, 104307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong L., Simard M.J., Huot J. (2018). Endothelial microRNAs regulating the NF-κB pathway and cell adhesion molecules during inflammation. FASEB J. 32, 4070–4084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu G., Xie J., Kong W. et al. (2020). Phase separation of disease-associated SHP2 mutants underlies MAPK hyperactivation. Cell 183, 490–502.e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.