Abstract

Purpose

This study explored nurses’ experience of “good nursing care” in the context of caring for terminally ill and end-of-life patients, providing a foundation for improving patient care.

Methods

We employed a qualitative research approach, integrating both inductive and deductive analysis methods. Data collection occurred from May 1 to August 1, 2023, involving nine nurses from intensive care units, hospice and palliative care wards, and nursing homes. All participants had at least two years of experience in caring for terminally ill and end-of-life patients. Data were collected through individual in-depth interviews and analyzed using Colaizzi’s six-stage phenomenological method for inductive analysis, and a deductive method based on four taxonomies client domain, client-nurse domain, practice domain, and environment domain.

Results

A total of 172 meaningful statements were derived, with five themes and 57 (33.14%) statements in the client-nurse domain, including three phenomena (contact, communication, and interaction); eight themes and 91 (52.91%) statements in the practice domain, including three phenomena (mentalistic, enactment, and role related phenomenon); and five themes and 24 (13.95%) statements in the environmental domain, including three phenomena (physical, social, and symbolic).

Conclusion

The 18 themes of good nursing care, as conceived and experienced by nurses who cared for terminally ill and end-of-life patients, underscore the importance of attentive nursing care.

Keywords: Patients, Terminally ill, Nursing, Qualitative research

INTRODUCTION

When a person is nearing death and cannot care for himself or herself, he or she requires assistance from others. The role of nurses, who provide round-the-clock care, is particularly crucial for terminally ill and end-of-life (EoL) patients in Korea. Most patients in hospice care die in hospital-based hospices [1]. As caregivers and patients become more knowledgeable, the importance of the quality of care is increasingly emphasized. Consequently, there is a growing demand for ‘good care’ and ‘high-quality nursing’. In response, the Korea Institute for Healthcare Accreditation [2] is calling for ongoing improvements in nursing quality, emphasizing the need for ‘safe and accurate nursing’.

The concept of a “good nurse” has evolved over time. During the Nightingale era, nurses were primarily seen as loyal and cooperative assistants, with a strong emphasis on ethics and virtue. Following World War II, the role of nurses expanded to include independent responsibilities, reflecting advancements in science. In the latter half of the 20th century, the focus shifted to nurses as care experts, highlighting the fundamental aspect of nursing care. More recently, in the 21st century, the importance of nurses as patient advocates has been recognized [3]. It has been suggested that the good nurses of the future will need to possess skills in autonomy, advocacy, accountability, and assertiveness [4]. Consequently, the core values that underpin “good nursing” are also undergoing significant changes.

In particular, the elderly population in Korea aged 65 or older is projected to increase by more than 30% from 2015, reaching 9,938,000 by 2024. Concurrently, the number of cancer patients has steadily risen, from 2013 to 277,523 in 2021, with the mortality rate continuing to climb through 2022 [5]. As a result, many terminally ill and EoL patients at the end of their lives are dying in medical institutions, highlighting an urgent need to redefine the concepts of “quality nursing” and “good nursing” and to establish clear guidelines for their care. Nurses who care for terminally ill and EoL patients often balance the biomedical perspective of ‘life extension’ with the hospice perspective of ‘pain relief and peaceful death’ [6]. They recognize the importance of alleviating pain and helping patients end their lives with dignity. However, while there are studies on good nursing from the general perspective of nurses [7] and from the perspective of cancer patients [8,9], research on ‘good nursing’ specifically in the context of terminal care remains scarce.

Therefore, this study aimed to examine the characteristics of good nursing from the perspectives of nurses and the core essence of nursing care for terminally ill and EoL patients. Specifically, it seeks to understand the concept of “good nursing” as experienced by nurses who provide care for terminally ill patients. These patients are expected to die within several months due to progressively worsening symptoms and have no prospects for recovery despite active treatment. The findings from this study will serve as foundational data for enhancing nursing practices for such patients. The analysis will be conducted using a typology that encompasses four distinct conceptual areas: client, client-nurse, practice, and environments. This framework, suggested by Kim [10], serves as the metaparadigm framework of nursing. The classification system within this framework is an effective analytical tool for categorizing and defining concepts and phenomena within specific boundaries. It facilitates the generation and evaluation of conceptualization and theoretical statement, with a clear understanding of the empirical locality of the phenomena [10]. Furthermore, this framework aids in conceptualizing and theorizing observations about the nursing world, demonstrating how theoretical concepts manifest in actual nursing practices [10]. An analysis using this metaparadigm framework of nursing will provide contextual understanding and interpretive insights in nurses’ perceptions of good nursing practice in caring for terminally ill and EoL patients, and will provide evidence for good nursing practice in caring for terminally ill and EoL patients.

METHODS

1. Study design

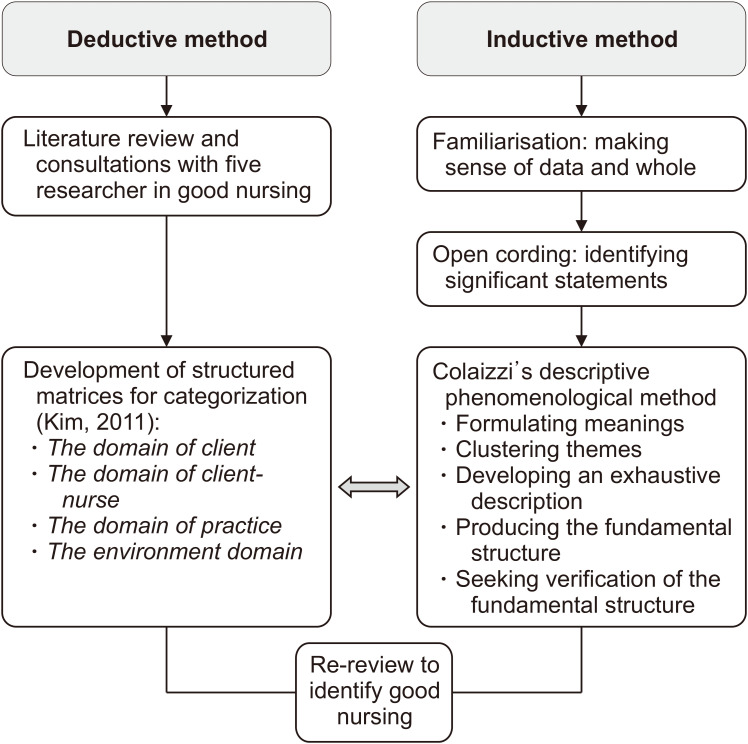

This study employed a qualitative research approach, utilizing both inductive and deductive analysis methods. Inductive analysis was based on content analysis, while deductive analysis followed Kim’s classification system [10]. The focus was on examining nurses’ experiences of providing quality care to terminally ill and EoL patients (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Research design.

2. Participants

For this study, purposive sampling was employed to select nurses from intensive care units, hospice and palliative care settings, and nursing homes. Eligible participants were required to have at least two years of experience in caring for terminally ill and EoL patients, possess insightful stories about the significance and value of quality nursing experiences, understand the study’s objectives, and consent to participate. Nurses with less than two years of practical experience were excluded because, according to Benner’s “from novice to expert” theory [11], nurses typically begin to appreciate the essence of “good nursing” once they reach the competent stage.

The research participants, who comprised nine participants from various wards, were individually interviewed. This process continued until no new concepts emerged and data saturation was achieved.

3. Ethical considerations and data collection

This study commenced data collection following approval from the K University Institutional Review Board, prior to the study’s initiation (No. 2023-03-005-001).

All researchers involved in this study have completed training in qualitative research and possess the necessary experience to conduct this study effectively. The research question, “What is the meaning of good nursing?” as experienced by nurses caring for terminally ill and EoL patients, was formulated during two video conferences held by the researchers. During these meetings, they thoroughly discussed and agreed upon the research methodology and data collection techniques that best suited the study’s objectives, aiming to minimize discrepancies among the researchers.

The data collection period spanned from May 1 to August 1, 2023. Nurses with over two years of experience in caring for terminally ill and EoL patients in intensive care units, hospice and palliative care settings, and nursing homes were recruited with the permission and cooperation of the nursing departments. Data were collected using the individual in-depth interview method. To promote a natural interview environment, a comfortable location conducive to open discussion and suitable for recording was chosen. Interviews typically lasted between 60 and 90 minutes. Before each interview, the purpose and procedures of the study were explained to the participants. They were encouraged to express their thoughts freely and comfortably, beginning with casual questions at a time they preferred. The in-depth interviews involved open-ended questions about the nurses’ experiences of what constitutes “good nursing.” Based on their responses, the questions were progressively focused using follow-up queries such as “why,” “how,” and “what.” No questions were designed to lead the participants to a predetermined conclusion. Specific questions included: “What do you consider good nursing for terminally ill and EoL patients? Can you recall an instance where you applied such nursing? How did you feel at that time? What constitutes special nursing care for terminally ill and EoL patients? What are your thoughts on such nursing?” During the interviews, participants’ behaviors, facial expressions, movements, and intonation were meticulously observed and later analyzed to interpret their meanings.

4. Data analysis

Inductive and deductive methods were employed for data analysis (Figure 1). Using the deductive approach, we analyzed the classification system that facilitates systematic analysis of elements in nursing situations. This system is based on Kim’s [10] theoretical framework, which includes four categories: client, client-nurse relationships, nursing practice, and environment domain. The researchers held two sessions to thoroughly explore and discuss the significance of each domain.

For the inductive method, we applied the phenomenological method of qualitative research analysis using Colaizzi’s six stages [12] to clearly interpret the content described by the participants and to accurately capture the essence of the phenomenon. The analysis process of this study proceeded as follows: Step 1: Listening to the recorded data, transcribing it, reading the participants’ descriptions (protocols), and repeatedly reviewing the data to gain a comprehensive understanding. Step 2: Extracting significant statements from the transcripts that pertain to positive nursing experiences. Step 3: Providing a general restatement of the extracted sentences and phrases. Step 4: Deriving formulated meanings from the significant statements and their restatements. Step 5: Organizing these meanings into themes, theme clusters, and categories. The categories were organized according to the four frameworks of the deductive method (client, client-nurse, practice, and environment domains), and theme clusters were classified based on the phenomena within each domain. Each researcher independently analyzed the data using the content analysis strategy, grouped similar content, and repeatedly reviewed key statements until consensus was reached on each subtheme. Additionally, repeated reviews were conducted to derive theme clusters, or phenomena, by categorizing them by topic within each category. Five rounds of discussions were held to address any inconsistencies among researchers and to reach a consensus. In the sixth step, a comprehensive statement (exhaustive description) was formulated regarding the phenomenon and topic of interest. Finally, participants were asked to confirm whether they agreed with the findings derived by the researchers. Additionally, the frequency and percentage of each topic corresponding to the categories were presented as methods of quantitative analysis.

To ensure the rigor of this study, and considering the involvement of all interviewers, we adhered to Sandelowski’s criteria for qualitative research: credibility, fittingness, auditability, and confirmability [13]. To enhance credibility, we transcribed responses from open-ended questions and interviews verbatim and analyzed them to verify the appropriateness of the derived themes as research results. We continued interviews with research participants until we gathered enough data to meet the criterion of fittingness. Additionally, the findings were evaluated by two experts in hospice and terminal patient care to assess their viability. For auditability, the researcher utilized field notes to check the consistency of the data collection process, including the methods used and researcher participation. The data analysis procedure was documented thoroughly, enabling other researchers to trace it, and this process was repeatedly verified. To maintain confirmability, during the interviews, we asked participants to clarify any ambiguous statements. This step helped to reconfirm and clarify the participants’ meanings, ensuring that the researcher’s bias did not influence the results and that neutrality was maintained.

RESULTS

1. General characteristics of participants

The study participants included seven women (77.78%), with an average age of 38.22±12.37 years. Six of the participants (66.67%) were employed at general hospitals or tertiary general hospital. The average length of their nursing careers was about 13 years (153.33±133.16 months). It was also noted that approximately 80 patients (80.22±195.25) died annually under their care (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Participants (N=9).

| Characteristics | Categories | Mean±SD (min~max) | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 7 (77.78) | |

| Male | 2 (22.22) | ||

| Age | 38.22±12.37 (26~61) | ||

| 20s | 4 (44.44) | ||

| 30s | 2 (22.22) | ||

| >40s | 3 (33.33) | ||

| Type of hospital | Tertiary general hospital | 1 (11.11) | |

| General hospital | 5 (55.55) | ||

| Primary hospital | 2 (22.22) | ||

| Long-term care hospital | 1 (11.11) | ||

| Current unit/ workplace | Hospice | 4 (44.44) | |

| Intensive care unit | 4 (44.44) | ||

| Other | 1 (11.11) | ||

| Clinical career (mo) | 153.33±133.16 (25~456) | ||

| Career in current unit (mo) | 83.11±83.06 (25~264) | ||

| Patient deaths experienced while working as a nurse (no. of people) | 20~35 | 4 (44.44) | |

| 35~50 | 2 (22.22) | ||

| 50~100 | 1 (11.11) | ||

| ≥100 | 2 (22.22) | ||

| Patient deaths in a year (no. of people) | 80.22±195.25 (3~600) |

2. Good nursing care for terminally ill and EoL patients by nurses

A total of 172 meaningful statements were extracted from the raw data collected from participants. These statements were classified using Kim’s [10] four-classification system, which employs the deductive method. The classification revealed that there were no themes in the client domain, while the client-nurse domain contained five themes, the practice domain contained eight themes, and the environment domain contained five themes, totaling 18 themes. The specific contents of these categories are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Nurses’ Experiences of Good Nursing Care for Terminally Ill and End-of-life Patients (N=172).

| Domain | Phenomena or concept | Themes | n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Client-nurse | Contact phenomena | 1.1. Stay together and provide comfort care | 5 (2.90) | 9 (5.23) | 57 (33.14) |

| 1.2. Walk a fine line between empathy and professionalism | 4 (2.33) | ||||

| Communication phenomena | 1.3. Build an empathetic relationship (rapport) | 20 (11.63) | 37 (21.51) | ||

| 1.4. Establish empathetic communication and help patients pass on without distress | 17 (9.88) | ||||

| Interaction phenomena | 1.5. Listen to the patient’s needs and negotiate flexibly | 11 (6.40) | 11 (6.40) | ||

| Practice | Mentalistic phenomenon | 2.1. Take interest in caring for patients and make clinical judgments | 13 (7.56) | 13 (7.56) | 91 (52.91) |

| Enactment phenomenon | 2.2. Provide fundamental care with respect | 13 (7.56) | 75 (43.60) | ||

| 2.3. Manage the symptoms (such as pain) for the patient’s comfort | 11 (6.40) | ||||

| 2.4. Understand patients and provide good nursing | 10 (5.81) | ||||

| 2.5. Understand the patient’s needs and provide comprehensive comfort care | 14 (8.14) | ||||

| 2.6. Help patients finish out their life | 21 (12.21) | ||||

| 2.7. Explain the patient’s condition thoroughly to family | 6 (3.49) | ||||

| Role related phenomenon | 2.8. Independently provide holistic nursing care | 3 (1.74) | 3 (1.74) | ||

| Environment | Physical environment | 3.1. Promote an appropriate environment for patients | 4 (2.33) | 4 (2.33) | 24 (13.95) |

| Social environment | 3.2. Offer support to patient and family to stay together | 4 (2.33) | 4 (2.33) | ||

| Symbolic environment | 3.3. Provide nursing care with respect | 2 (1.16) | 16 (9.30) | ||

| 3.4. Provide sincere nursing care from one’s heart | 6 (3.49) | ||||

| 3.5. Ensure that patients receive the best care | 8 (4.65) | ||||

Category 1: The Client-Nurse Domain

The client-nurse domain encompasses situations where nurses provide nursing care to clients through various contact methods. There were nine ‘contact phenomena’ (5.23%), 37 ‘communication phenomena’ (21.51%), and 11 ‘interaction phenomena’ (6.40%). A total of 57 statements (33.14%) were classified into these three categories.

1) Contact phenomena

Since nurses are integral to patient care, providing both assistance and direct nursing, the nature of their contact with patients is crucial. This contact can be understood in terms of therapeutic or instrumental interactions, as well as distancing strategies. The phenomenon of contact encompasses two main themes: “stay together and provide comfort care” and “walk a fine line between empathy and professionalism.” The good nursing, as experienced by nurses, involves actions that address the psychological and spiritual needs of patients. This might include holding a patient’s hand as they are dying or simply being present in silence. However, it is also important to maintain a suitable emotional distance. Over-identification with a patient can compromise the effectiveness of nursing care.

“Just being there with the patient can be a great help and good care to the patient. Being able to hold the patient’s hand at the moment of death and pray together with them...” (Participant 4)

“There is a certain boundary that cannot be crossed because we are at the relationship between hospital staff and patients. But it sometimes happens. “I think the line needs to be drawn. When we cross the line, it’s no longer a relationship between a nurse and a patient, or a guardian, but rather I am at somewhere in between their family. This does not help me make clear decisions since I become so emotional...” (Participant 5)

2) Communication phenomena

Nursing practices, including the exchange of information, emotions, and education between nurses and patients, are primarily conducted through communication. This encompasses concepts such as therapeutic and empathic communication, matching, and information exchange. The ‘communication phenomena’ encompasses two main themes: “build and empathetic relationship (rapport)” and “establish empathetic communication and help patients pass on without distress.” Effective nursing, as experienced by nurses, involves cultivating empathy in the process of ending life humanely prior to the conclusion of the nurse-patient relationship. It also includes assisting patients and their families in concluding their lives meaningfully and without regrets, ensuring they feel their lives are worthwhile.

“Hospice is mutual care and support between the host and the guest. But I realized what ‘mutual’ truly meant later. I always thought that I, we, were the one giving, but I was receiving so much from the patients. Especially in hospice. Because they leave us with so many valuable insights like how we should live, as they pass away. We gain a lot through our relationships with patients.” (Participant 9)

“Now, when the family members are with patients, I speak calmly: ‘Your family is with you now. Don’t worry. They are all watching over you, so you can rest comfortably.’ They acknowledge that their family is with them by hearing my voice...” (Participant 7)

“The most important thing is to guide them so that they can talk to their family. I guide the patient’s family to say everything they wish to share, as patients have sharp hearing even when lying down and unresponsive. I encourage family members to express their thoughts, say their goodbyes, and even share words they couldn’t say before.” (Participant 7)

3) Interaction phenomena

Nurses primarily deliver care to patients through interactions that include nonverbal communication, encompassing concepts such as role conflict, role modeling, and agreement. A key theme identified within this ‘interaction phenomena’ is “listen to the patient’s needs and negotiate flexibly.” Nurses have expressed that a positive nursing experience involves finding an optimal compromise through decision-making when there is a difference of opinion regarding hospice nursing goals between the patients or their families, or among the patients and their families themselves.

“Let’s go with what the patient wants and what makes the patient comfortable. If we do this now, the patient might have a hard time. However, the choice is up to the patient and the family, and moreover, saying such things can make the guardians feel guilty. I think we should be careful in what we say.” (Participant 7)

Category 2: The Practice Domain of Nursing

The nursing practice area encompasses phenomena experienced by nurses within their work environment. It was divided into three categories, comprising a total of 91 statements (52.91%). These included 13 ‘mentalistic phenomenon’ (7.56%) occurring during the deliberation stage, 75 ‘enactment phenomenon’ (43.60%), and 3 ‘role related phenomenon’ (1.74%). The phenomenon of knowledge utilization was not confirmed.

1) Mentalistic phenomenon

These phenomena emerge through cognitive processes when a nurse contemplates the appropriate actions for a patient. In the realm of nursing practice, one aspect identified within the mental phenomena associated with clinical decision-making was ‘take interest in caring for patients and make clinical judgments’. Effective nursing involves showing concern for the patient’s comfort and safety, evaluating the patient’s information, and proactively making judgments and decisions.

“When I observe senior nurses, I notice how they carefully monitor vital signs on the screen, paying close attention to any changes. They thoroughly assess these signs to understand the patient’s condition and actively engage with doctors, providing interventions to ensure the patient’s comfort...” (Participant 1)

2) Enactment phenomenon

The actual nursing work performed by nurses is demonstrated through their tasks, execution, and activities. The six themes identified within the practice behavior phenomenon included “provide fundamental care with respect,” “manage the symptoms (such as pain) for the patient’s comfort,” “understand patients and provide good nursing,” “understand the patient’s needs and provide comprehensive comfort care,” “help patients finish out their life,” and “explain the patient’s condition thoroughly to family.” Good nursing, as experienced by nurses, involves focusing on fundamental nursing practices and pain management to ensure that patients can enjoy basic human rights and remain comfortable. It also includes promptly recognizing changes in a patient’s condition and responding with appropriate care. Furthermore, good nursing means understanding the patient’s preferences and needs and striving to meet them as fully as possible, as well as honoring the patient’s life choices at the end of their life. Additionally, it involves providing detailed explanations and suitable opportunities for the family to remain informed and at ease, supporting a worry-free environment until the patient’s final moments.

“General care basic nursing is becoming more and more important. And even though they are nearing death, I think it means helping them maintain their dignity as much as possible.” (Participant 6)

“It’s important that the patient is having a hard time. I think that symptom control, such as pain or other important symptoms, is necessary before we can think about what comes next. So I try to prioritize that and make it as easy as possible. Ultimately, what’s important is that the patient is comfortable.” (Participant 3)

“When a patient’s blood pressure drops, it’s better to quickly assess the situation and communicate actively, rather than hesitating and not handling the situation well. If you can intervene effectively in an emergency with quick judgment and good communication, that would make you a truly good nurse. Of course, having both skills would be even better.” (Participant 1)

“It’s important to understand the patient’s personality and provide nursing care that meet the patient’s needs. Some people are picky, and some people think they will live even if they are on the verge of death. It’s important to provide nursing care according to their personality. That’s good nursing.” (Participant 4)

“I think the most important thing is respecting one’s own decisions and values. When it comes to one’s final moments, I believe it is important to allow them to pass in the way they wish.” (Participant 9)

“I definitely tell the guardians that there are differences between yesterday and today, and that there are differences in progress, and when I tell them from a nurse’s perspective, they are grateful, saying things like ‘I really appreciated that you explain it so well.’ I think that’s where the guardians feel reassured, so I honestly feel a sense of accomplishment in that regard.” (Participant 8)

3) Role related phenomenon

The phenomenon of nurses being the primary practitioners of nursing involves various elements such as requests, socialization, role ambiguity, power, and the negotiation of relationships with other medical staff. One aspect of these role-related phenomena is ‘independently provide holistic nursing care’. Nurses reported that to deliver comprehensive care, both physically and mentally, they often had to take on roles outside their usual duties. However, they expressed regret over the lack of autonomy and authority to make independent decisions in these matters.

“Nurses should just provide nursing care, so why do they keep interfering with the work of social workers or nuns? But what I felt really frustrated about was that when we first learned, we learned holistic nursing. Nurses. So, we also covered physical nursing, psychosocial, mental, and spiritual nursing. That was a source of conflict for me.” (Participant 9)

Category 3: The Environment Domain

The environment domain serves as the foundational basis for a comprehensive understanding and explanation of the phenomena related to the client, client-nurse, and nursing practice domain. It was categorized into three phenomena: the ‘physical environment’, represented by four statements (2.33%); the ‘social environment’, also represented by four statements (2.33%); and the ‘symbolic environment’, which included 16 statements (9.30%). In total, there were 24 statements in the environmental domain, accounting for 13.95% of the content.

1) Physical environment

The ‘physical environment’ is categorized into biotic elements, which are considered from the perspective of energy generation, and abiotic elements, viewed from the material-based perspective. One aspect of the ‘physical environment’ discussed was ‘promote an appropriate environment for patients’. Nurses expressed that effective nursing involves establishing a natural or familiar setting that allows patients to end their lives comfortably while minimizing environments that could induce anxiety.

“One thing I’ve really felt while working in hospice is that people truly love nature. The healing power of nature, the way it makes you reflect, I think it’s something that’s very necessary, and creating an environment that provides such an opportunity. It’s different from dying in a hospital environment—surrounded by unfamiliar things. I encourage patients to bring familiar items from their home. That’s also one good method.” (Participant 9)

2) Social environment

The ‘social environment’ refers to the individuals or groups with whom people interact and communicate. Nurses have the ability to manage this environment for their patients. One aspect of the ‘social environment’ identified was “offer support to patient and family to stay together.” Nurses expressed that ideal nursing involves creating a suitable environment where end-of-life patients can spend ample time with their caregivers. However, they also acknowledged the unfortunate reality that such togetherness is not always possible.

“I think it is good to provide a space and time where they can spend a lot of time with their caregiver, if possible, in terms of the mental aspect.” (Participant 8)

3) Symbolic environment

The ‘symbolic environment’ exists only within the realm of human cognition and comprises elements such as values, beliefs, rules, laws, organizations, and society. Within the environmental domain, the three identified themes of the ‘symbolic environment’ are “provide nursing care with respect,” “provide sincere nursing care from one’s heart,” and “ensure that patients receive the best care.” Nurses described good nursing as possessing a respectful heart towards patients and striving to provide the sincerest care possible, ensuring that patients can end their lives naturally. However, they acknowledged that delivering such quality care is often hindered by the high patient-to-nurse ratio.

“I think that the most important thing is to be able to protect the dignity of the patient, and to respect humanity.” (Participant 6)

“Good nursing means the nursing care that I have to do and the extra nursing care. It’s something that I do because I want to do it. In order to do good things, I have to do it with joy.” (Participant 4)

“I think I’m doing my best. I’m everything I can for this patient right now. I also hope that my efforts can make a difference for them, even if it’s just a small amount.” (Participant 2)

Discussion

In Korea, a significant number of deaths occur in hospitals. Although 95.8% of nurses in general hospitals have experience with terminally ill and EoL patients, they often lack specialized training for such care [14]. This gap in training can lead to various challenges when managing the complex symptoms of these patients. Notably, the mortality rate per 100,000 people has risen from 574.8 in 2019 to 727.6 in 2022 [5]. Additionally, the quality of end-of-life care for cancer patients in tertiary hospitals has reportedly declined during the COVID-19 pandemic [15]. The pandemic led to staff shortages as medical personnel were isolated, and despite fewer staff members, the number of deaths rose. Furthermore, social distancing measures and restrictions on hospital visits have complicated the provision of compassionate care, making it difficult for patients to experience a ‘good death’ and for their families to properly say their final goodbyes. Given these circumstances, it becomes even more crucial to explore what constitutes ‘good nursing’ from the perspective of nurses who care for terminally ill and EoL patients and those at the end of their lives, especially during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

This study employed qualitative research methods, incorporating both inductive and deductive analysis techniques. It utilized the theoretical framework of Kim’s [10] four-part classification system, which systematically analyzes elements in nursing situations using the deductive method. Research conducted within this framework includes a study from the field of pediatric nursing in Korea, which reviewed research concepts within the client domain [16], and another study that additionally analyzed the client-nurse, practice, and environment domains [17]. Internationally, a study examined the nature of nursing research in Northern European countries by categorizing papers according to this four-part classification system [18]. More recently, research employed keyword network analysis to categorize studies within the patient safety [19]. No previous study has analyzed the topic of “good nursing” using Kim’s [10] four-part classification system as a theoretical foundation. Therefore, it is significant that this research conceptualized and analyzed the phenomenon of “good nursing” for terminal patients by applying the mid-range theory of nursing.

In this study, the most frequently observed phenomena in client-nurse included communication (21.51%), building an empathetic relationship (rapport) (11.63%), and establishing empathetic communication and helping patients pass on without distress (9.88%). Given the terminal status of the patients, the importance of family presence at the time of death was emphasized, along with the need for sufficient communication to facilitate a dignified farewell. It was noted that, even when patients could not communicate extensively, nurses still engaged in significant exchanges with them. Um et al. [20] described the hallmarks of “good nursing” as primarily involving communication, particularly the development of rapport in the emergency room setting. This includes providing reassurance and expressing empathy at the patient’s level. Furthermore, “good nursing” from the nurse’s perspective involves forming a therapeutic relationship where the patient feels thoroughly cared for through professional, comprehensive, and autonomous nursing practices. This approach not only focuses on patient care but also ensures satisfaction for both the nurse and the patient [7].

Among the client-nurse, practice, and environment domains, the practice domain was the most commonly mentioned (52.91%) by nurses regarding their experiences of good nursing. Um et al. [20] noted that a nurse who demonstrates good nursing through meticulous and accurate actions rather than words aligns with the 5.81% of this study’s statements that emphasized understanding the patient and skillfully providing nursing care. In this study, nurses caring for terminally ill and EoL patients reported that good nursing involved allowing patients to die according to their wishes, respecting their self-determination and the values they deemed important. Most nurses stated that they helped patients finish out their life, as reflected in 12.21% of statements. They also highlighted the importance of understanding the patient’s preferences and providing tailored nursing care, specifically understanding the patient’s needs and providing comprehensive comfort care (8.14%). Advisory hospice nurses [21] stated that they addressed the overall needs of patients and their families by providing patient- and family-centered end-of-life care. Cho and Na [22] appear essential to support patients in achieving their desired death by focusing on natural, painless deaths without reliance on mechanical devices, fostering intimacy that includes end-of-life and psychological satisfaction in interactions with significant others, and maintaining a sense of control that encompasses physical and mental functionality until death. Moreover, providing fundamental care with respect (7.56%) is crucial among various patient care tasks, but managing symptoms such as pain to ensure comfort for terminally ill and EoL patients (6.40%) was also identified as an aspect of “good nursing.” Research on terminal nursing care performance [23] ranked “providing physical nursing including oral care and changing positions for terminal or end-of-life patients” second, and “administering drug therapy for symptoms including pain for these patients” third, underscoring the importance of pain management for terminal and end-of-life patients, consistent with findings from this study.

In the environment domain, the ‘symbolic environment’ was identified as the most prevalent (9.30% of statements). It is characterized by a commitment to excellence and sincerity in nursing care, exemplified by sentiments such as, “I’m doing the best I can for this patient right now. And I hope that my best can be of some help to this person,” and “It’s something that I do because I want to do it. In order to do good things, I have to do it with joy.” A key attribute of a good nurse is their personal satisfaction and happiness, both with themselves and their role in nursing. They feel a strong sense of being needed by many people and find comfort in the moments spent working in the ward [20]. Furthermore, returning to the fundamental nature of nursing, especially in the care of terminally ill and EoL patients who may be unconscious or less interactive, it is crucial to maintain a respectful attitude, acknowledging that “In the end, I think the most important thing is to respect people.” Care for these patients should also include providing familiar objects, allowing them to experience nature, and creating an environment where they are not in sight of other terminally ill patients (2.33%). Additionally, while these patients spend considerable time with nurses, it is equally important to be considerate and allow ample time for interactions with their guardians (2.33%).

In this study, nurses reported that a lower patient-to-nurse ratio allows them to provide better care for terminally ill patients. With fewer patients, they can focus more on patient care rather than on documenting consultation records. However, they also expressed concerns about being too busy at times, which compromises the quality of care they wish to deliver. Additionally, environmental constraints were mentioned as a regrettable limitation. This study suggests that nurses can develop a foundation for improved care performance by gaining a contextual understanding and interpretive insight into effective nursing practices for terminally ill and EoL patients. Although this study involved only nine participants, future research should include a larger number of nurses to deepen the understanding of care for this patient group. The subject area of this study was not covered in Kim’s [10] client, client-nurse, practice, and environment domains. This omission is likely because the subject area primarily encompasses essentialistic, problematic, and healthcare experiential dimensions, focusing on issues reported by the participants. Additionally, this study primarily explored the phenomena, beliefs, and thoughts that arise during interactions between nurses and terminally ill or EoL patients, as well as throughout the care process. To grasp the concept of quality nursing for terminally ill and EoL patients, it is crucial to understand what constitutes good nursing from the perspective of the patients receiving care.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary materials can be found via https://doi.org/10.14475/jhpc.2024.27.4.120.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

AUTHOR’S CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception or design of the work: MNL. Data collection: all authors. Data analysis and interpretation: all authors. Drafting the article: MNL, JWS, HJW, HZL. Critical revision of the article: MNL, JWS, HJW. Final approval of the version to be published: MNL, JWS, HJW.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Hospice Center & Ministry of Health and Welfare, author. Hospice & palliative care in Korea : Facts & figures 2023. National Hospice Center & Ministry of Health and Welfare; Goyang: 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Korea Institute for Healthcare Accreditation, author. Accreditation standards and guidelines [Internet] Korea Institute for Healthcare Accreditation; Seoul: 2021. [cited 2024 Oct 22]. Available from: https://www.koiha.or.kr/web/kr/library/establish_board.do . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fry ST. In: Handbook of bioethics : Taking stock of the field from a philosophical perspective. Khushf G, editor. Springe; Dordrecht: 2004. Nursing ethics; pp. 489–505. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Begley AM. On being a good nurse: reflections on the past and preparing for the future. Int J Nurs Pract. 2010;16:525–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2010.01878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Statistics Kore, author. Korean Statistical Information Service's Top 100 Indicators [Internet] Ministry of Health and Welfare; Goyang: 2024. [cited 2024 Oct 22]. Available from: https://kosis.kr/visual/nsportalStats/main.do . [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho MO. Experiences of ICU nurses on temporality and spatiality in caring for dying patients. J Qual Res. 2010;11:80–93. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee EK, Kwon SB, Cha HG, Kim HJ. The good nursing of experienced as a nurse. KSW. 2017;12:305–17. doi: 10.21097/ksw.2017.05.12.2.305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho NO, Hong YS, Han SS, Um YR. Attributes perceived by cancer patients as a good nurse. J Korean Clin Nurs Res. 2006;11:149–62. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suh EY, Yoo HJ, Hong JH, KWON IG, Song HJ. Good nursing experience of patients with cancer in a Korean Cancer Hospital. Journal of Korean Critical Care Nursing. 2020;13:51–61. doi: 10.34250/jkccn.2020.13.3.51. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim HS. The nature of theoretical thinking in nursing. 3rd ed. HYUNMOON Publishing Co.; Seoul: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benner P. From novice to expert. Am J Nurs. 1982;82:402–7. doi: 10.1097/00000446-198282030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colaizzi PF. In: Existential phenomenological alternatives for psychology. Valle RS, King M, editors. Oxford University Press; New York: 1978. Psychological research as the phenomenologist views it; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sandelowski M. The problem of rigor in qualitative research. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 1986;8:27–37. doi: 10.1097/00012272-198604000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim DR, Han EK, KIM SH, LEE TW, Kim KN. Factors influencing nurses' ethical decision-making regarding end-of-life care. Korean Journal of Medical Ethics. 2014;17:34–47. doi: 10.35301/ksme.2014.17.1.34. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shin J, Kim Y, Yoo SH, Sim JA, Keam B. Impact of COVID-19 on the end-of-life care of cancer patients who died in a Korean tertiary hospital: a retrospective study. J Hosp Palliat Care. 2022;25:150–8. doi: 10.14475/jhpc.2022.25.4.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han KJ, Kim JS, Kim SY, Kim HA. An analysis of the concepts in child health nursing studies in Korea (1): from 1990 to 2000. Child Health Nurs Res. 2002;8:449–57. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han KJ, Cho KM, Kim HA, Kim JS, Kim SY. An analysis of the concepts in child health nursing studies in Korea (2): The practice, the client-nurse, the environmental domain. Child Health Nurs Res. 2004;10:165–72. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lundgren SM, Valmari G, Skott C. The nature of nursing research: dissertations in the Nordic countries, 2003. Scand J Caring Sci. 2009;23:402–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2008.00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim EJ, Seomun G. Exploring the knowledge structure of patient safety in nursing using a keyword network analysis. Comput Inform Nurs. 2023;41:67–76. doi: 10.1097/CIN.0000000000000882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Um YR, Song KJ Park MH; Hospital Nurses Association, author. Good nurses better nursing. HAKJISA, INC.; Seoul: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kwon S, Byun J. Clinical experience of nurses in a consultative hospice palliative care service. J Hosp Palliat Care. 2024;27:31–44. doi: 10.14475/jhpc.2024.27.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho M, Na H. Factors that influence attitudes toward advance directives among hemodialysis patients. J Hosp Palliat Care. 2024;27:11–20. doi: 10.14475/jhpc.2024.27.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jung SY, Song HS, Kim JY, Koo HJ, Shin YS, Kim SR, et al. Nurses' perception and performance of end-of-life care in a tertiary hospital. J Hosp Palliat Care. 2023;26:101–11. doi: 10.14475/jhpc.2023.26.3.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.