Classes de Recomendação:

Classe I: Condições para as quais há evidências conclusivas e, na sua falta, consenso geral de que o procedimento é seguro e útil/eficaz.

Classe II: Condições para as quais há evidências conflitantes e/ou divergência de opinião sobre segurança e utilidade/eficácia do procedimento.

Classe IIa: Peso ou evidência/opinião a favor do procedimento. A maioria aprova.

Classe IIb: Segurança e utilidade/eficácia menos estabelecidas, havendo opiniões divergentes.

Classe III: Condições para as quais há evidências e/ou consenso de que o procedimento não é útil/eficaz e, em alguns casos, pode ser prejudicial.

Níveis de Evidência

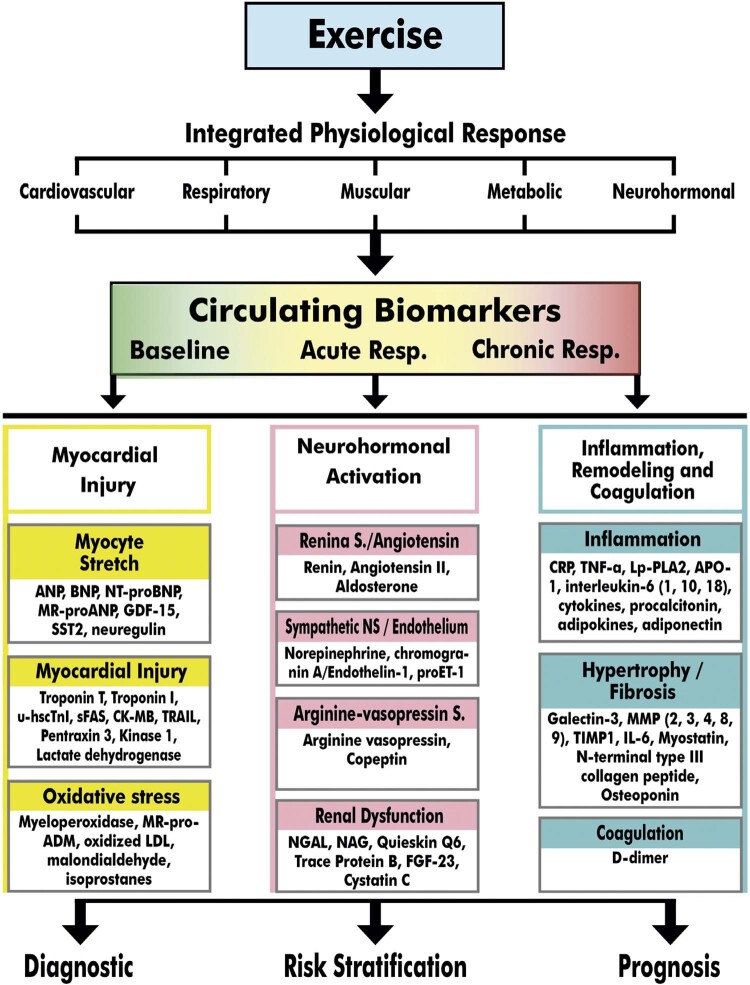

Nível A: Dados obtidos a partir de múltiplos estudos randomizados de bom porte, concordantes e/ou de metanálise robusta de estudos randomizados.

Nível B: Dados obtidos a partir de metanálise menos robusta, a partir de um único estudo randomizado e/ou de estudos observacionais.

Nível C: Dados obtidos de opiniões consensuais de especialistas.

| Diretriz Brasileira de Ergometria em População Adulta – 2024 | |

|---|---|

| O relatório abaixo lista as declarações de interesse conforme relatadas à SBC pelos especialistas durante o período de desenvolvimento deste posicionamento, 2022/2023. | |

| Especialista | Tipo de relacionamento com a indústria |

| Anderson Donelli da Silveira | Nada a ser declarado |

| Andréa Maria Gomes Marinho Falcão | Nada a ser declarado |

| Antonio Eduardo Monteiro de Almeida | Nada a ser declarado |

| Arnaldo Laffitte Stier Junior | Declaração financeira A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Libbs: educação continuada, Ebatz, Vatis. Outros relacionamentos Participação societária de qualquer natureza e qualquer valor economicamente apreciável de empresas na área de saúde, de ensino ou em empresas concorrentes ou fornecedoras da SBC: - Quanta Diagnóstico Curitiba. |

| Artur Haddad Herdy | Nada a ser declarado |

| Carlos Alberto Cordeiro Hossri | Nada a ser declarado |

| Claudia Lucia Barros de Castro | Nada a ser declarado |

| Clea Simone Sabino de Souza Colombo | Nada a ser declarado |

| Dalton Bertolim Precoma | Declaração financeira A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Novonordisk: Ozempic; Daiichi-Sankyo: Lixiana; Servier: Vastarel; Astrazeneca: Forxiga. B - Financiamento de pesquisas sob sua responsabilidade direta/pessoal (direcionado ao departamento ou instituição) provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Bayer: anticoagulante; Janssen: anticoagulante; Novonordisk: cardiometabolismo; Astrazeneca: insuficiência cardíaca, hipercalcemia, disfunção diastólica; Daiichi-Sankyo: anticoagulante; Cardiol: COVID e miocardite; Servier: coronariopatia crônica. Outros relacionamentos Financiamento de atividades de educação médica continuada, incluindo viagens, hospedagens e inscrições para congressos e cursos, provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Novonordisk: cardiometabolismo; Daiichi-Sankyo: anticoagulante; Servier: coronariopatia crônica; Torrent: dislipidemia. Participação societária de qualquer natureza e qualquer valor economicamente apreciável de empresas na área de saúde, de ensino ou em empresas concorrentes ou fornecedoras da SBC: - Área da Saúde: medicina nuclear. |

| Fabio Sandoli de Brito | Nada a ser declarado |

| Felipe Lopes Malafaia | Nada a ser declarado |

| Iran Castro | Nada a ser declarado |

| José Luiz Barros Pena | Nada a ser declarado |

| Josmar de Castro Alves | Nada a ser declarado |

| Leonardo Filipe Benedeti Marinucci | Nada a ser declarado |

| Luiz Eduardo Fonteles Ritt | Declaração financeira A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Boeringher Lilly: Jardiance; Novonordis: pesquisador em estudos; Astrazeneca; Novartis; Bayer; Bristol; Pfizer. B - Financiamento de pesquisas sob sua responsabilidade direta/pessoal (direcionado ao departamento ou instituição) provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - MDI Medical. Outros relacionamentos Financiamento de atividades de educação médica continuada, incluindo viagens, hospedagens e inscrições para congressos e cursos, provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Novo Nordisk: Ozempic. |

| Luiz Eduardo Mastrocola | Nada a ser declarado |

| Marcelo Luiz Campos Vieira | Nada a ser declarado |

| Mauricio Milani | Nada a ser declarado |

| Mauro Augusto dos Santos | Nada a ser declarado |

| Miguel Morita Fernandes da Silva | Declaração financeira A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Novartis: Entresto; Bayer: Firialta; Astrazeneca: Forxiga; Boehringer: Jardiance. B - Financiamento de pesquisas sob sua responsabilidade direta/pessoal (direcionado ao departamento ou instituição) provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Novartis; Bayer. |

| Odilon Gariglio Alvarenga de Freitas | Nada a ser declarado |

| Pedro Ferreira de Albuquerque | Declaração financeira A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - MMedicine Cursos: aula de Ergometria. Outros relacionamentos Vínculo empregatício com a indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras, assim como se tem relação vínculo empregatício com operadoras de planos de saúde ou em auditorias médicas (incluindo meio período) durante o ano para o qual você está declarando: - Sócio Cooperado da Unimed Maceió Alagoas. |

| Ricardo Quental Coutinho | Nada a ser declarado |

| Ricardo Stein | Outros relacionamentos Financiamento de atividades de educação médica continuada, incluindo viagens, hospedagens e inscrições para congressos e cursos, provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Life Genomics |

| Salvador Manoel Serra | Nada a ser declarado |

| Susimeire Buglia | Nada a ser declarado |

| Tales de Carvalho | Nada a ser declarado |

| William Azem Chalela | Nada a ser declarado |

Sumário

Parte 1 – Indicações, Aspectos Legais e Formação em Ergometria 08

1. Introdução 08

2. Indicações e Contraindicações do TE e TCPE, Inclusive Associados a Imagens 08

2.1. Indicações Gerais do TE 08

2.2. Indicações do TE em Situações Clínicas Específicas 09

2.2.1. Indicações do TE na Doença Arterial Coronariana 09

2.2.2. Indicações do TE em Assintomáticos 09

2.2.3. Indicações do TE em Atletas 09

2.2.4. Indicações do TE na Hipertensão Arterial Sistêmica 09

2.2.5. Indicações do TE em Valvopatias 09

2.2.6. Indicações na Insuficiência Cardíaca e nas Cardiomiopatias 11

2.2.7. Indicações do TE no Contexto de Arritmias e Distúrbios de Condução 11

2.2.8. Indicações do TE em Outras Condições Clínicas 12

2.3. Contraindicações Relativas e Absolutas 12

2.3.1. Contraindicações Relativas do TE/TCPE 12

2.3.2. Contraindicações Absolutas do TE/TCPE 14

2.4. Indicações do TCPE 14

2.4.1. Indicações Gerais do TCPE 14

2.4.2. Indicações do TCPE em Situações Clínicas Específicas 14

2.5. Indicações do TE/TCPE Associados a Métodos de Imagem 14

2.5.1. Cintilografia de Perfusão Miocárdica 14

2.5.2. Indicações da Ecocardiografia sob Estresse 15

3. Aspectos Legais e Condições Imprescindíveis para Realização do TE, TCPE e Quando Associados a Exames Cardiológicos de Imagem 16

3.1. Aspectos Legais da Prática do TE e TCPE 16

3.2. Condições Imprescindíveis à Realização do TE e TCPE 16

3.3. Termo de Consentimento para o TE e TCPE 20

3.4. Termo de Consentimento ao TE Associado a Métodos de Imagem 21

4. Aspectos Referentes à Formação na Área de Atuação de Ergometria 21

Parte 2 – Teste Ergométrico 23

1. Metodologia do TE 23

1.1. Condições Básicas para a Realização do TE 23

1.1.1. Equipe 23

1.1.2. Área Física 23

1.1.3. Equipamentos 23

1.1.4. Material para Emergência Médica 24

1.1.5. Medicamentos para Emergência Médica 24

1.1.6. Orientações ao Paciente na Marcação do TE 24

1.2. Procedimentos Básicos para a Realização do TE 24

1.2.1. Fase Pré-teste 24

1.2.2. Avaliação Inicial 25

1.2.3. Exame Físico Sumário e Específico 25

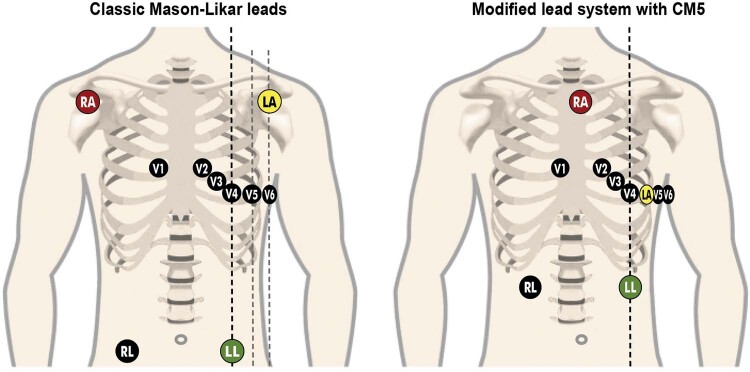

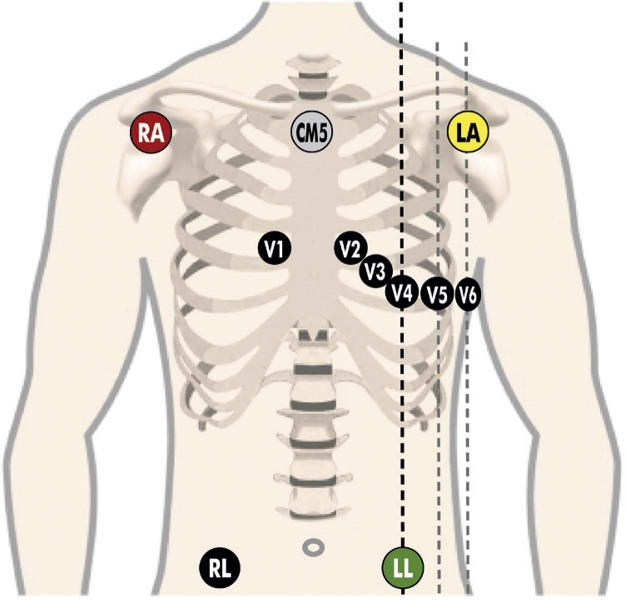

1.2.4. Sistema de Monitorização e Registro Eletrocardiográfico 25

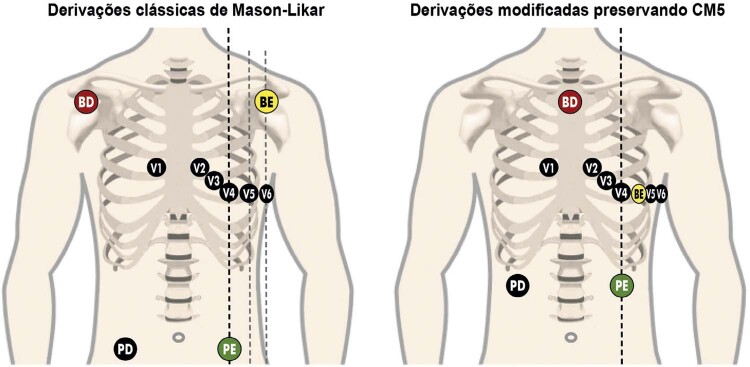

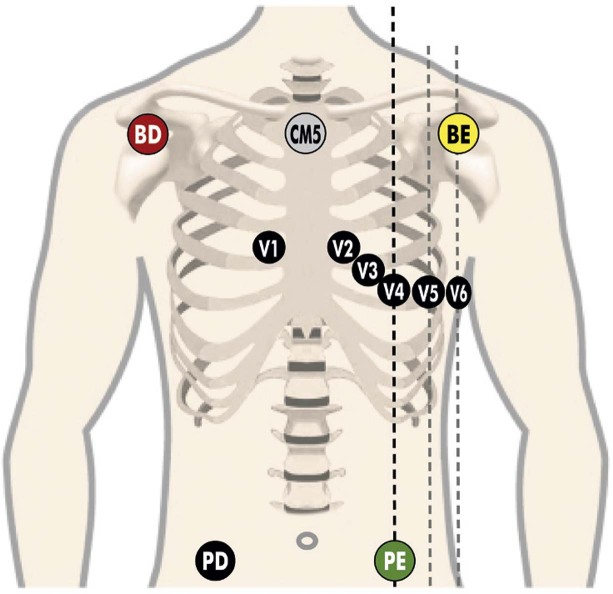

1.2.4.1. Sistemas de Três Derivações 25

1.2.4.2. Sistema de 12 Derivações 25

1.2.4.3. Sistema de 13 ou Mais Derivações 26

1.2.4.4. Preparo da Pele para Monitorização Eletrocardiográfica 26

1.2.4.5. Registros Eletrocardiográficos 26

1.2.5. Monitorização dos Dados Hemodinâmicos 27

1.2.5.1. Monitorização da Frequência Cardíaca 27

1.2.5.2. Monitorização da Pressão Arterial Sistêmica 27

1.2.6. Monitoração de Sinais e Sintomas 27

1.2.7. Profilaxia de Complicações no TE 28

1.3. Ergômetros 28

1.3.1. Cicloergômetro 28

1.3.2. Esteira Ergométrica 28

1.3.3. Cicloergômetro de Braço 28

1.3.4. Outros Ergômetros 28

1.4. Escolha do Protocolo 28

1.4.1. Protocolos para Bicicleta Ergométrica 28

1.4.2. Protocolos para Esteira Ergométrica 29

1.4.2.1. Protocolos Escalonados 29

1.4.2.1.1. Protocolo de Bruce 29

1.4.2.1.2. Protocolo de Bruce Modificado 29

1.4.2.1.3. Protocolo de Ellestad 29

1.4.2.1.4. Protocolo de Naughton 29

1.4.2.2. Protocolo em Rampa 29

1.4.3. Protocolo para Ergômetro de Braços 30

1.4.4. Interrupção/Término do Exame 30

2. Acurácia, Probabilidade e Escores Pré-teste 30

2.1. Probabilidade Pré-teste de DAC 30

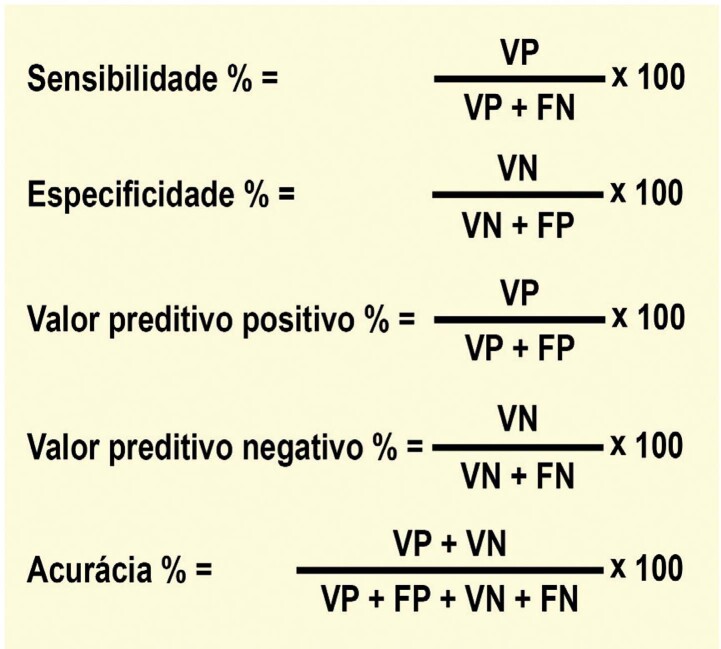

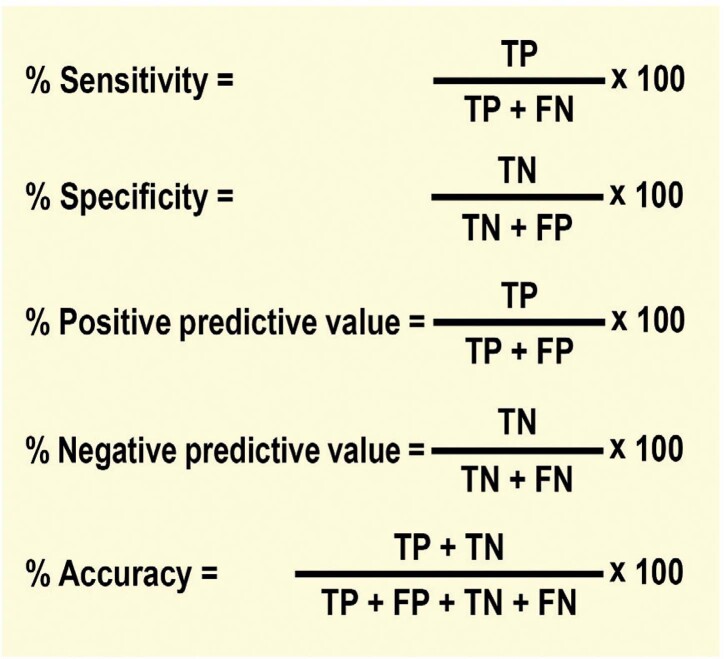

2.2. Sensibilidade, Especificidade e Valor Preditivo 30

2.3. Escores e Fatores de Risco DCV Pré-teste 31

3. Respostas Clínicas e Hemodinâmicas ao Esforço na População Adulta 32

3.1. Respostas Clínicas 32

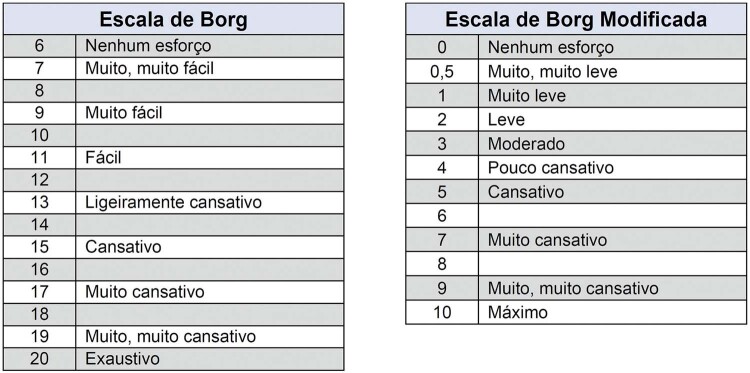

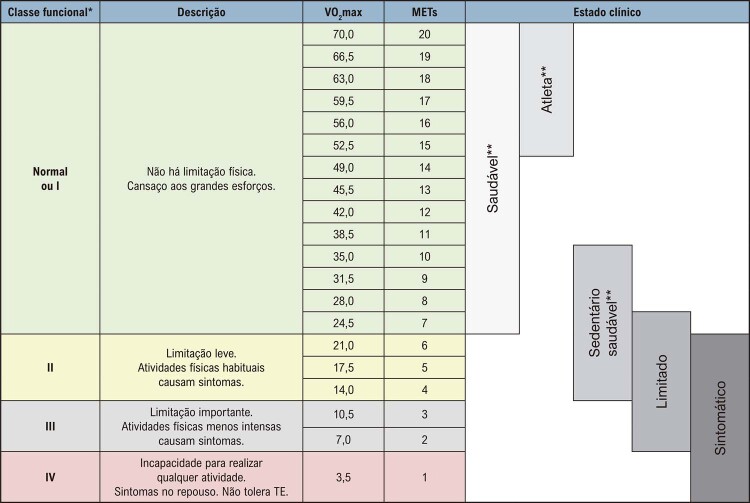

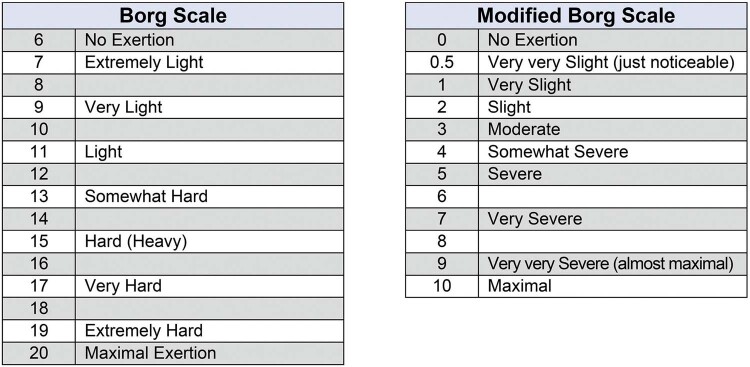

3.1.1. Tolerância ao Esforço 32

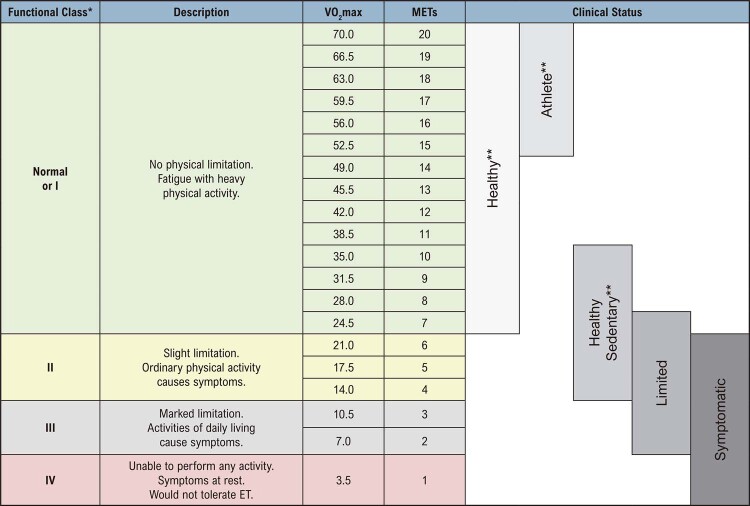

3.1.2. Aptidão Cardiorrespiratória/Classificação Funcional 32

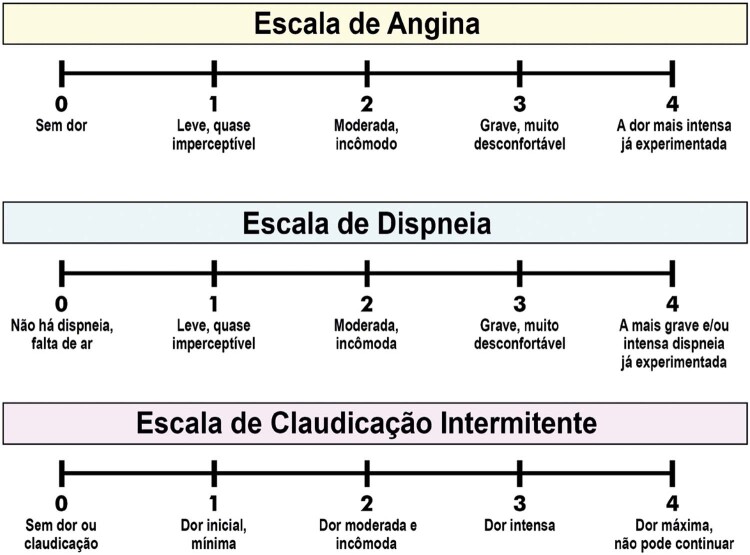

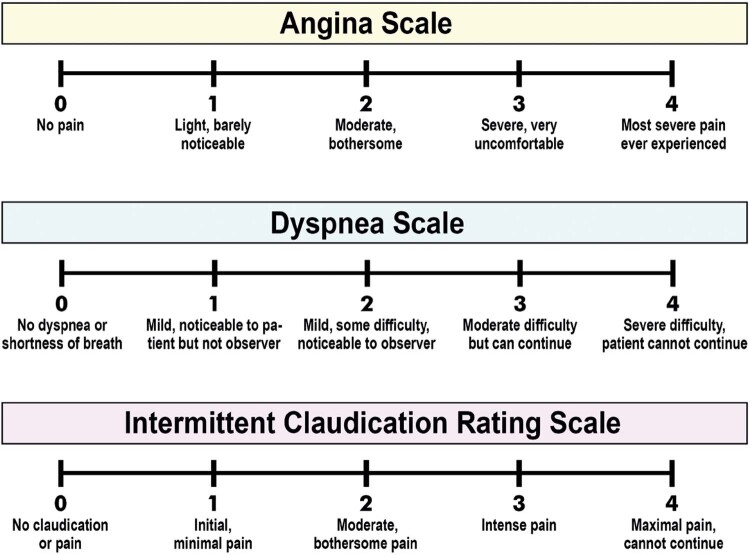

3.1.3. Sintomas 33

3.1.4. Ectoscopia/Ausculta 34

3.2. Respostas Hemodinâmicas 35

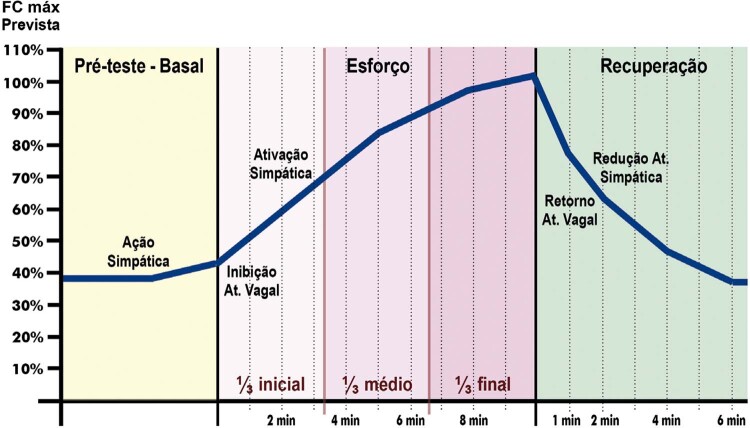

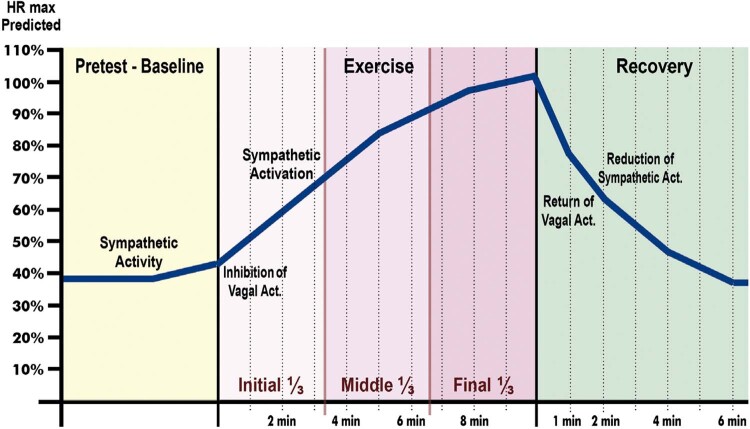

3.2.1. Frequência Cardíaca 35

3.2.1.1. Frequência Cardíaca de Repouso 35

3.2.1.2. Resposta Cronotrópica 35

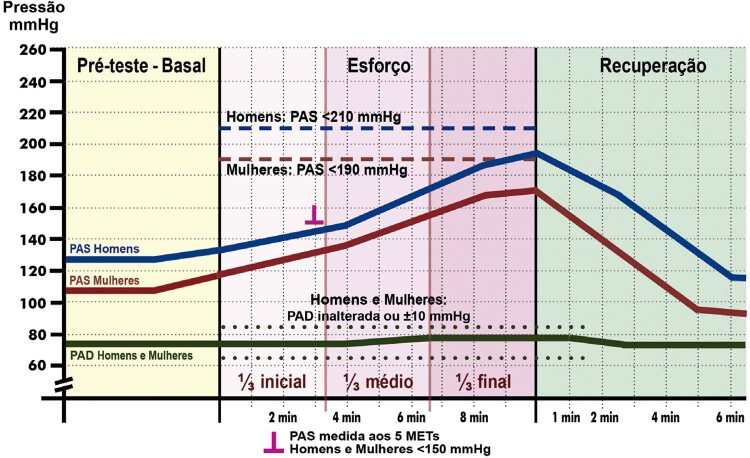

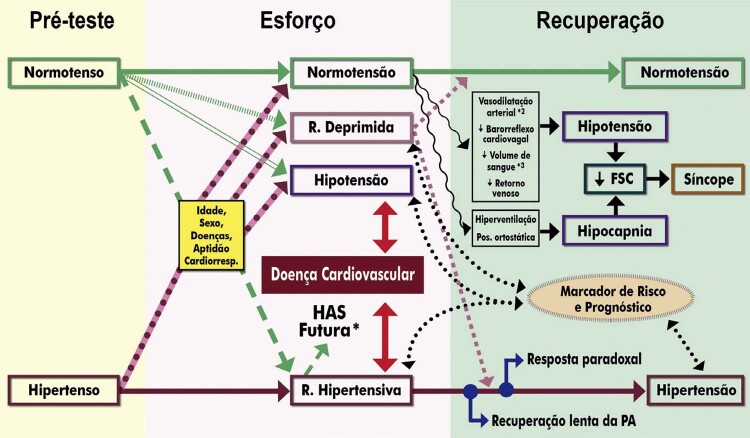

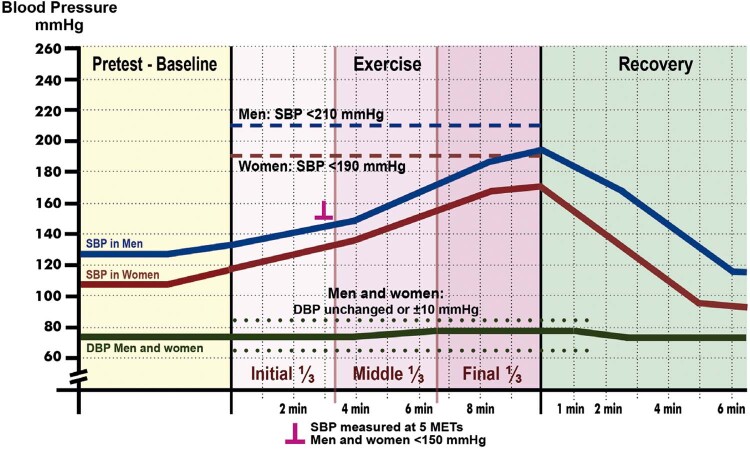

3.2.2. Resposta da Pressão Arterial 36

3.2.3. Duplo-Produto 39

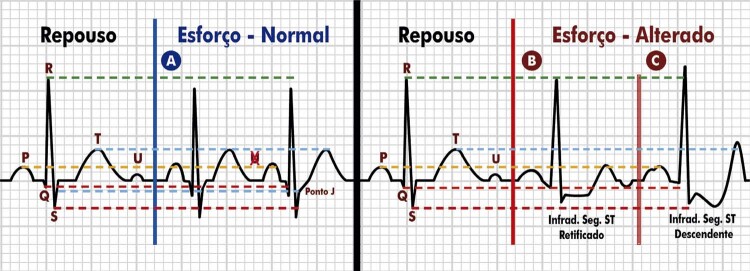

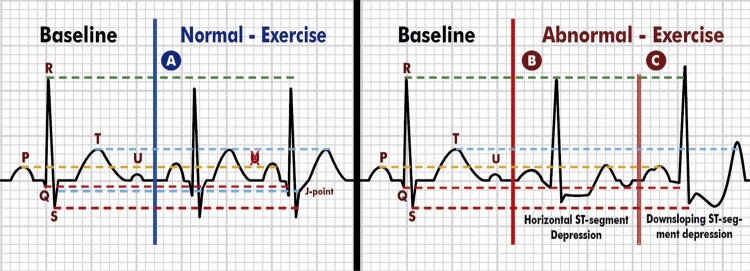

4. Respostas Eletrocardiográficas 41

4.1. Onda P 42

4.1.1. Respostas Normais 42

4.1.2. Respostas Anormais 42

4.2. Intervalo PR/Segmento PR 43

4.2.1. Respostas Normais 43

4.2.2. Respostas Anormais 43

4.3. Onda Q 43

4.3.1. Respostas Normais 43

4.3.2. Respostas Anormais 43

4.4. Onda R 43

4.4.1. Respostas Normais 43

4.4.2. Respostas Anormais 43

4.5. Onda S 44

4.5.1. Respostas Normais 44

4.5.2. Respostas Anormais 44

4.6. Duração QRS 44

4. 6.1. Respostas Normais 44

4.6.2. Respostas Anormais 44

4.7. Fragmentação de QRS em Alta Frequência 44

4.7.1. Respostas Normais 44

4.7.2. Respostas Anormais 45

4.8. Onda T 45

4.8.1. Respostas Normais 45

4.8.2. Respostas Anormais 45

4.9. Onda U 45

4.9.1. Respostas Normais 45

4.9.2. Respostas Anormais 45

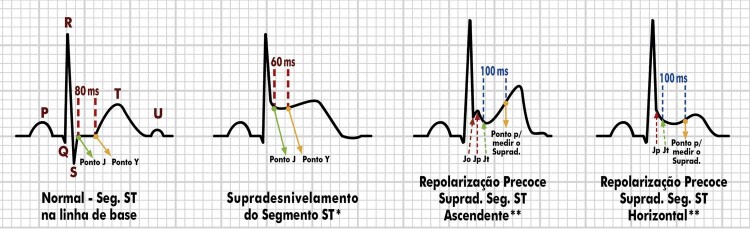

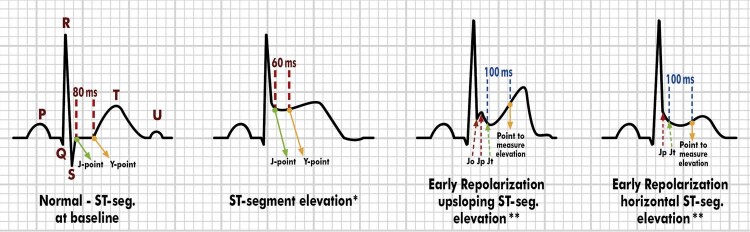

4.10. Repolarização Precoce 46

4.11. Supradesnivelamento do Segmento ST 47

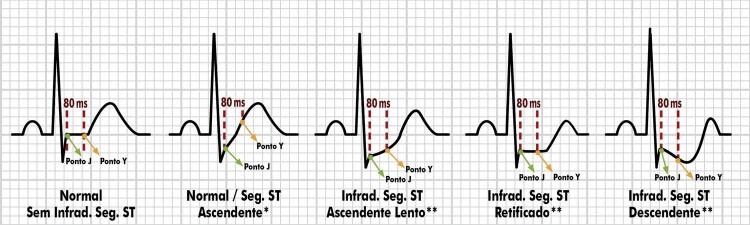

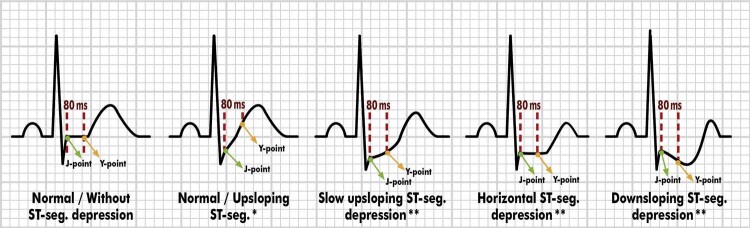

4.12. Ponto J e Infradesnivelamento Ascendente 47

4.13. Infradesnivelamento do Segmento ST: Ascendente Lento, Horizontal e Descendente 48

4.13.1. Sinal de Corcunda do Segmento ST 49

4.14. Normalização de Alterações do Segmento ST 49

4.15. Inclinação ( Slope ) ST/FC, Índice ST/FC, Loop ST/FC e Histerese ST/FC 49

4.15.1. Inclinação ( Slope ) ST/FC 49

4.15.2. Índice ST/FC 49

4.15.3. Loop ST/FC 50

4.15.4. Histerese ST/FC 50

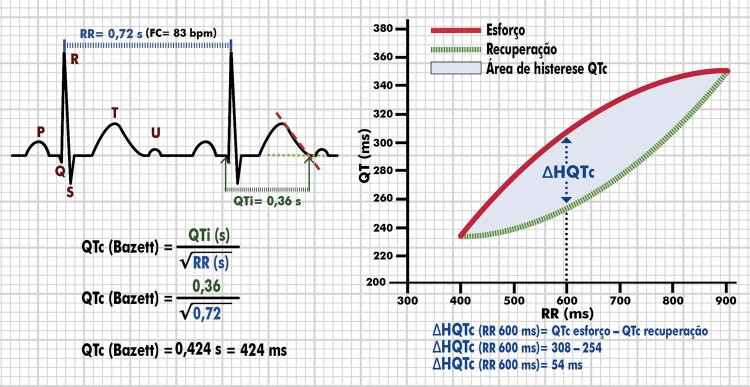

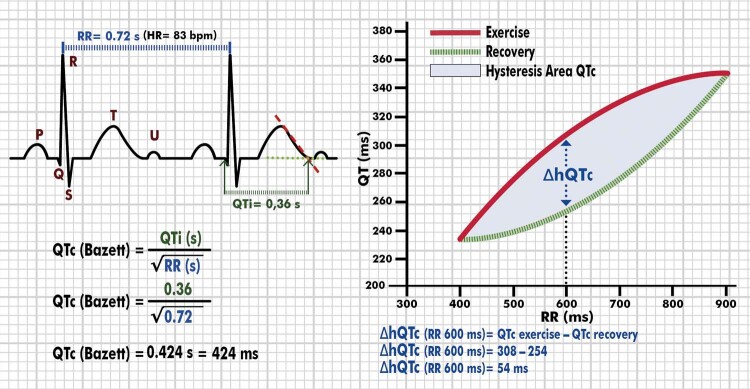

4.16. Intervalo QT/QTc/Histerese QT/Dispersão QT 50

4.17. Distúrbios da Condução Atrioventricular, Intraventricular e da Formação do Impulso 51

4.17.1. Distúrbios da Condução Atrioventricular 51

4.17.1.1. Bloqueio Atrioventricular (BAV) de Primeiro Grau 51

4.17.1.2. Bloqueio Atrioventricular de Segundo Grau Tipo I (Mobitz I) 52

4.17.1.3. Bloqueio Atrioventricular de Segundo Grau Tipo II (Mobitz II) 52

4.17.1.4. Bloqueio Atrioventricular Tipo 2:1/Bloqueio Atrioventricular Avançado ou de Alto Grau/Bloqueio Atrioventricular de Terceiro Grau ou Total 52

4.17.2. Distúrbios da Condução Intraventricular 53

4.17.2.1. Bloqueio de Ramo Esquerdo 53

4.17.2.1.1. Bloqueio do Ramo Esquerdo Preexistente 53

4.17.2.1.2. Bloqueio do Ramo Esquerdo Esforço-induzido 53

4.17.2.2. Bloqueios Divisionais do Ramo Esquerdo 54

4.17.2.3. Bloqueio de Ramo Direito 54

4.17.2.3.1. Bloqueio de Ramo Direito Preexistente 54

4.17.2.3.2. Bloqueio de Ramo Direito Esforço-induzido 54

4.17.3. Distúrbios da Formação do Impulso 55

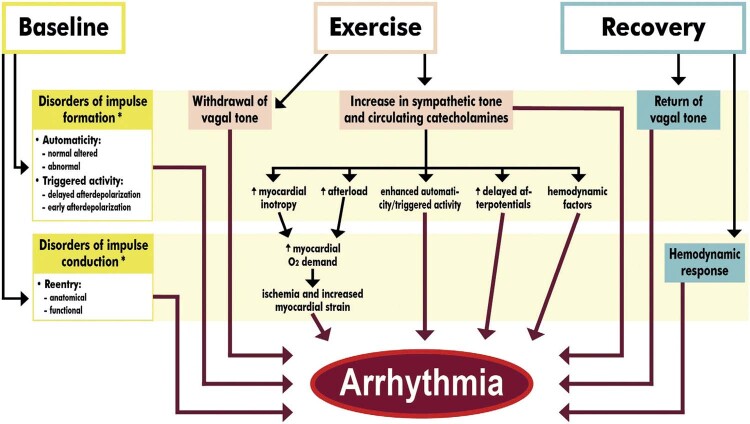

4.17.3.1. Arritmias Ventriculares 55

4.17.3.2. Arritmias Supraventriculares 57

4.17.3.3. Fibrilação Atrial/Flutter Atrial 57

4.17.3.4. Bradiarritmias/Incompetência Cronotrópica Crônica 58

4.17.3.5. Taquicardia Sinusal Inapropriada 59

4.18. Avaliação Metabólica Indireta 59

4.18.1. VO 2 /METs 59

4.18.2. Déficit Funcional Aeróbico (FAI) 59

4.18.3. Déficit Aeróbio Miocárdico (MAI) 60

4.19. Escores de Risco Pós-teste e Variáveis Prognósticas do TE 60

4.19.1. Escore de Duke 60

4.19.2. Escore de Athenas/Escore QRS 61

4.19.3. Escore de Raxwal e Morise 61

5. Critérios de Interrupção do Esforço 62

6. Elaboração do Laudo do TE 62

6.1. Dados Gerais 62

6.2. Dados Observados, Mensurados e Registrados 62

6.3. Relatório Descritivo 63

6.4. Conclusão 64

6.5. Registros Eletrocardiográficos 64

7. Exames Realizados Simultaneamente e Adicionalmente ao TE 65

7.1. Índice Tornozelo-braquial 65

7.1.1. Realização do Exame ITB 65

7.1.1.1. ITB de Repouso 65

7.1.1.2. ITB Pós-esforço 66

7.1.2. Preparação do Paciente e Técnica de Exame 66

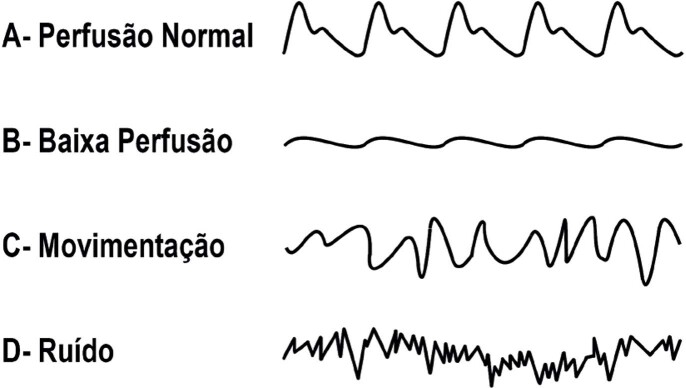

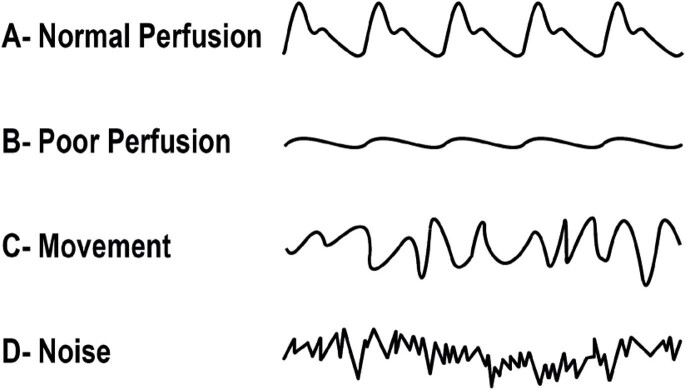

7.2. Oximetria Não Invasiva 67

7.2.1. Equipamentos 67

7.2.2. Procedimentos da Oximetria Não Invasiva 68

7.2.3. Interpretação dos Dados 68

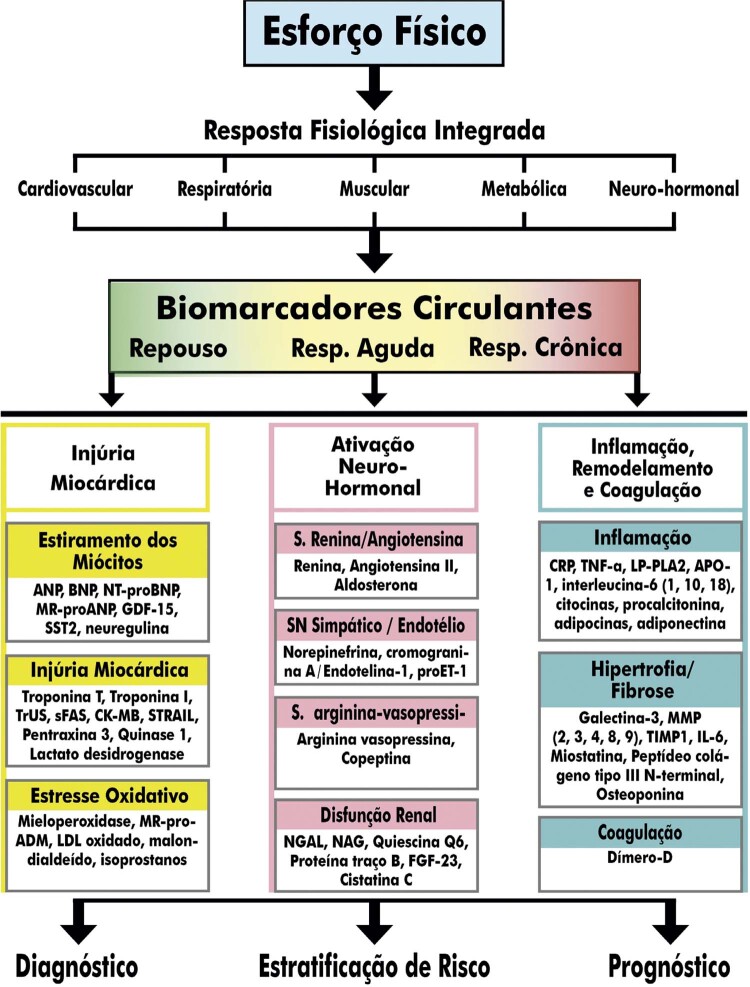

7.3. Biomarcadores e Exames Laboratoriais 69

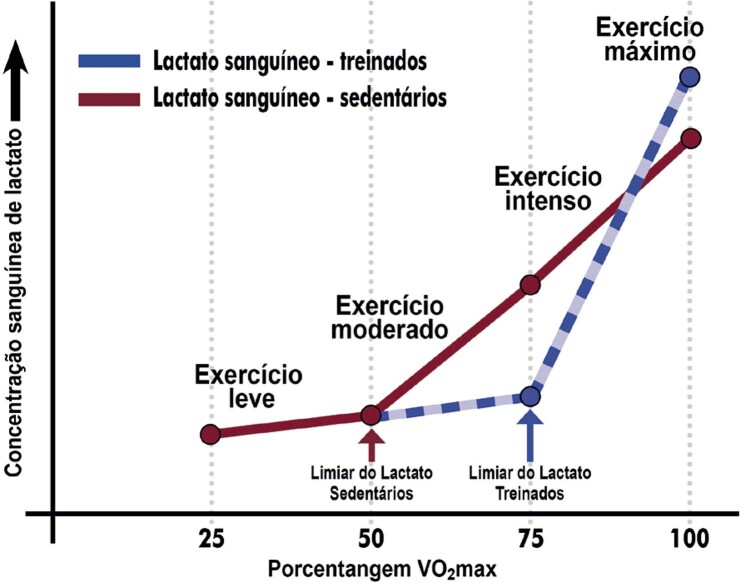

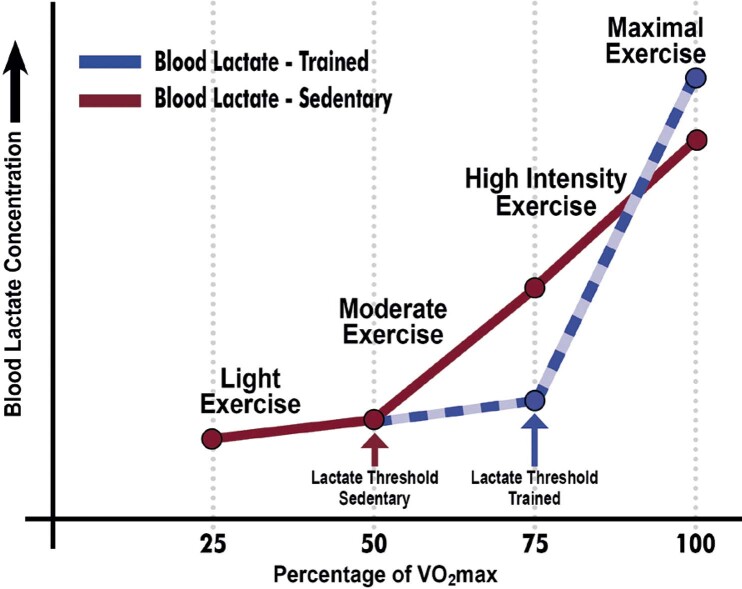

7.3.1. Lactato Sanguíneo 70

7.3.2. Gasometria Arterial 70

8. Particularidades na Realização e Interpretação do TE em Condições Clínicas Específicas 71

8.1. Dextrocardia/ Situs Inversus 71

8.2. Doença de Chagas/Cardiomiopatia Chagásica 72

8.3. Doença Arterial Periférica 73

8.4. Doença de Parkinson 74

8.5. Doenças Valvares 75

8.5.1. Estenose Aórtica 75

8.5.2. Regurgitação Aórtica 76

8.5.3. Estenose Mitral 76

8.5.4. Regurgitação Mitral 77

8.5.5. Prolapso da Válvula Mitral 77

8.6. TE Pós-revascularização Miocárdica 78

8.6.1. TE após Intervenção Coronária Percutânea 78

8.6.2. TE após Cirurgia de Revascularização Miocárdica 79

Parte 3 – Teste Cardiopulmonar de Exercício 79

1. Introdução 79

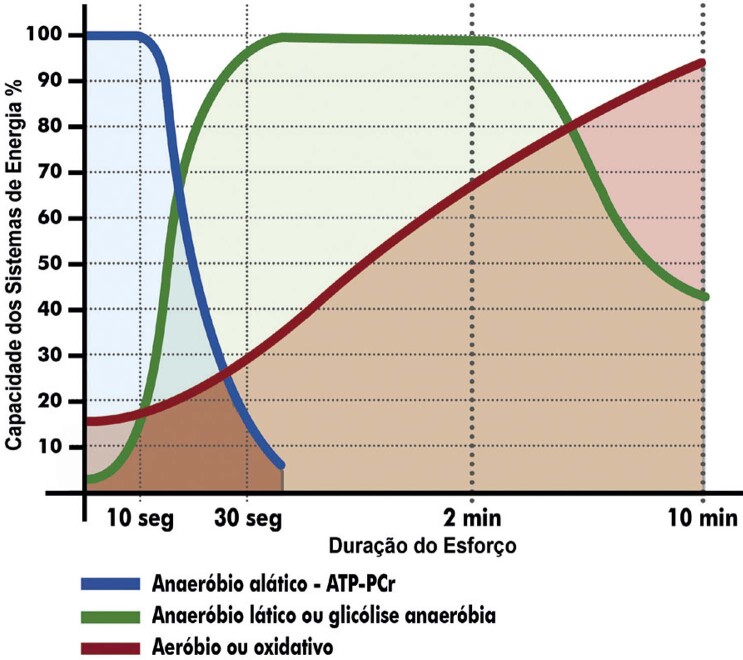

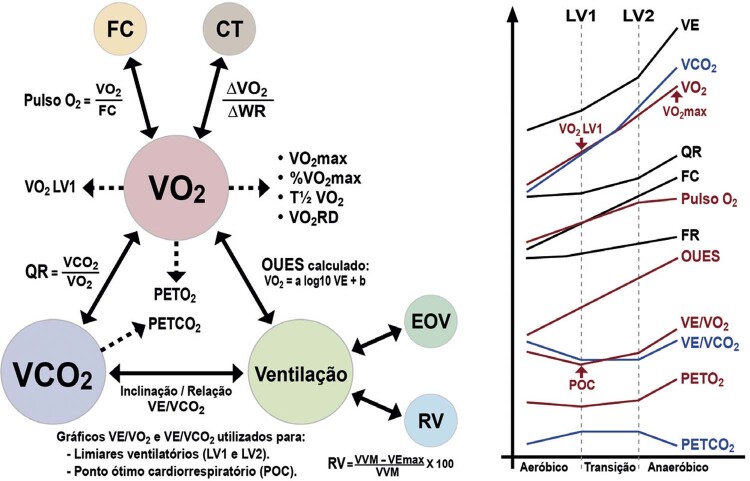

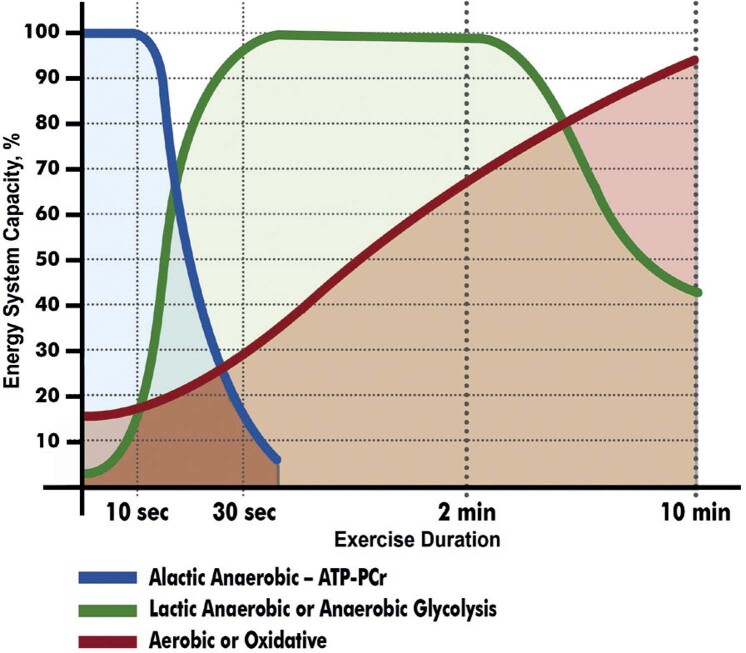

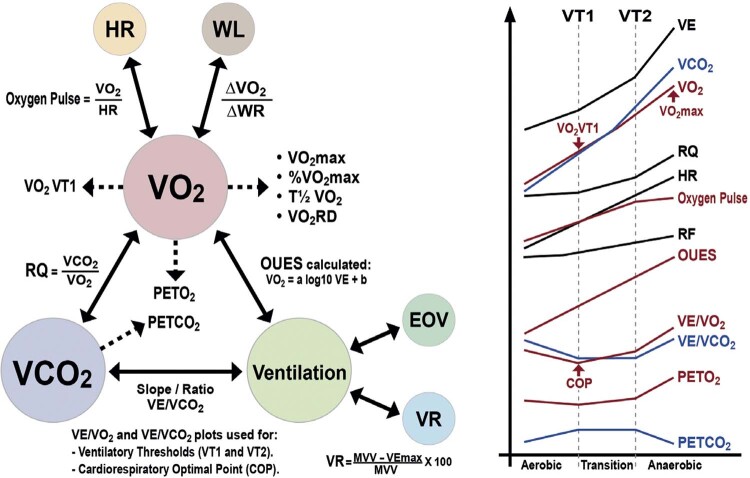

2. Fisiologia do Exercício Aplicada ao TCPE 79

3. Ventilação Pulmonar, Gases no Ar Expirado e Variáveis Derivadas 80

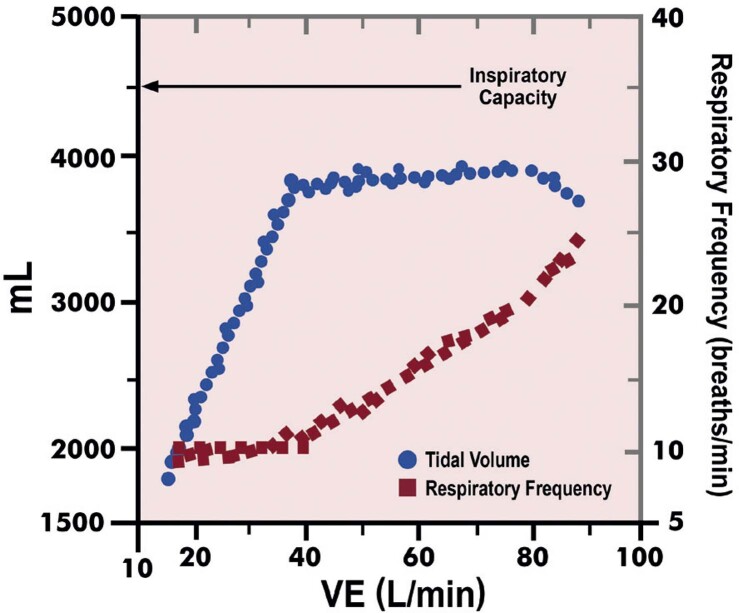

3.1. Ventilação Pulmonar 80

3.1.1. Espirometria Basal 80

3.1.2. Ergoespirometria 81

3.1.3. Reserva Ventilatória 81

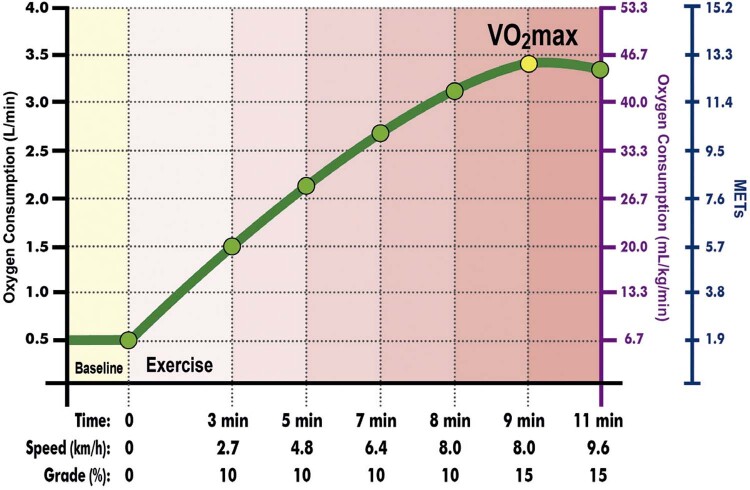

3.2. Consumo de Oxigênio 82

3.3. Produção de Gás Carbônico 82

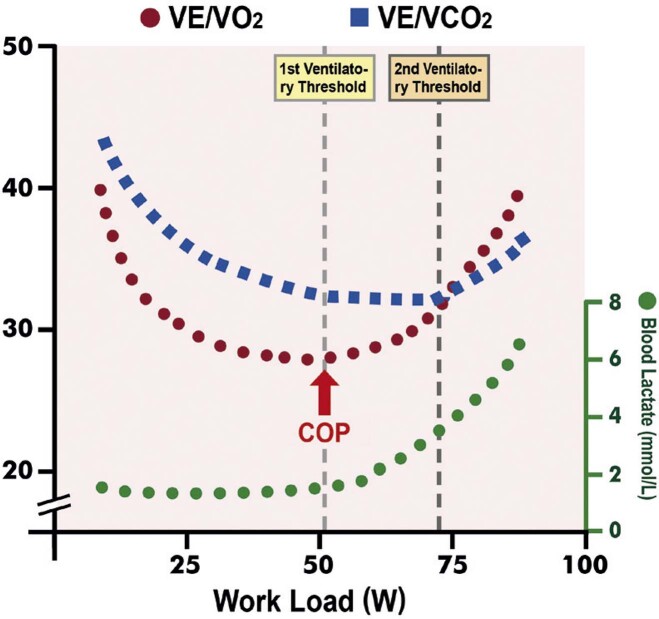

3.4. Limiares Ventilatórios 82

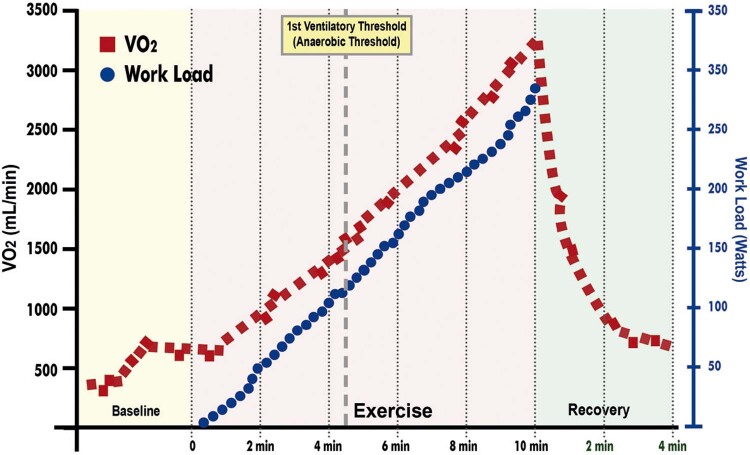

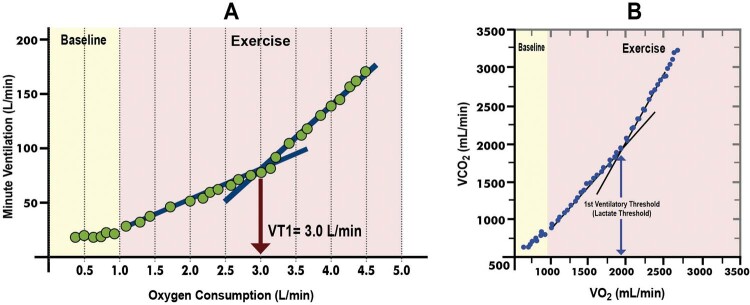

3.4.1. Primeiro Limiar Ventilatório 82

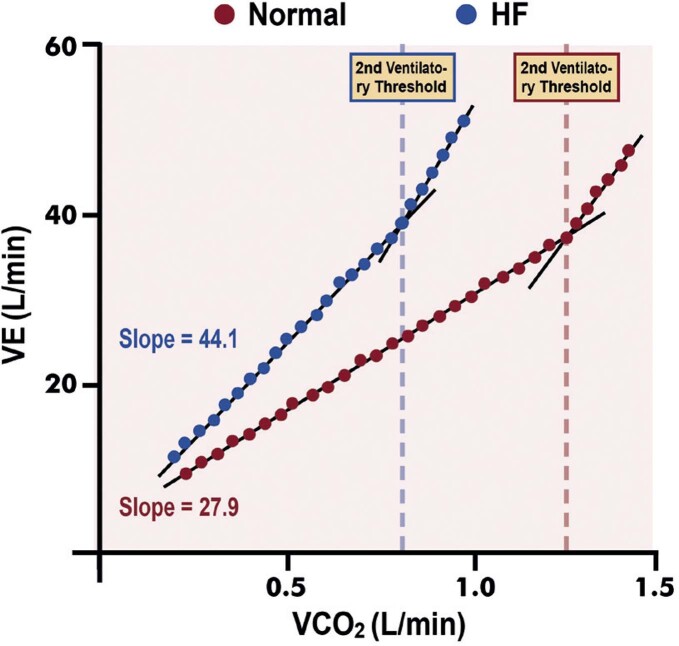

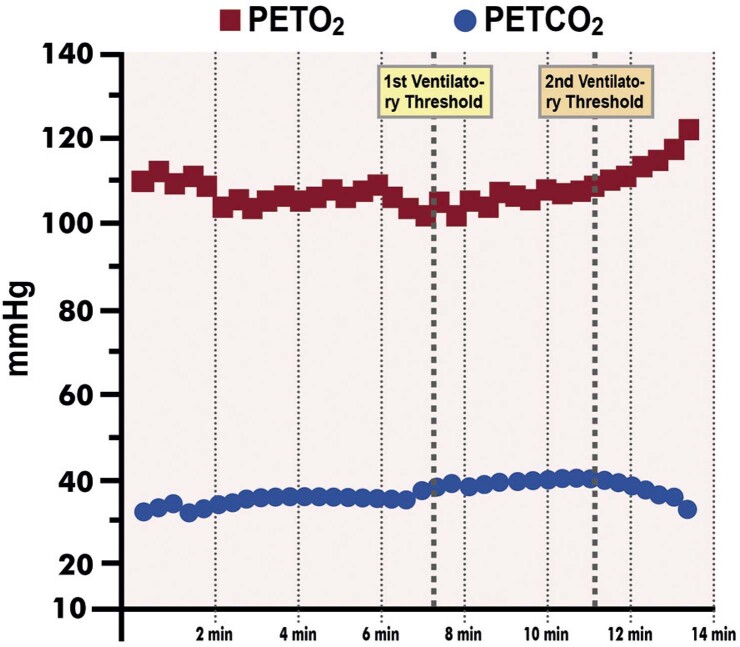

3.4.2. Segundo Limiar Ventilatório 83

3.5. Quociente Respiratório 84

3.6. Equivalentes Ventilatórios de Oxigênio e Gás Carbônico 84

3.7. Pressões Parciais Expiratórias do Oxigênio e Dióxido de Carbono 84

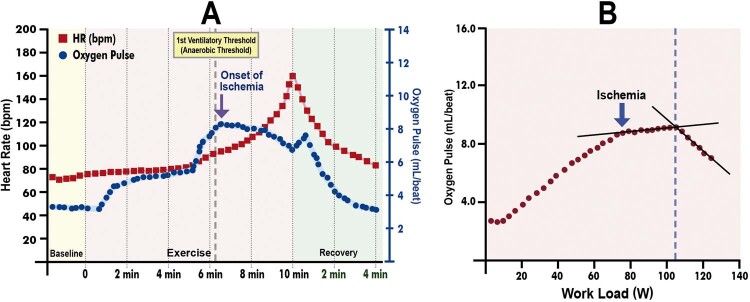

3.8. Pulso de Oxigênio 85

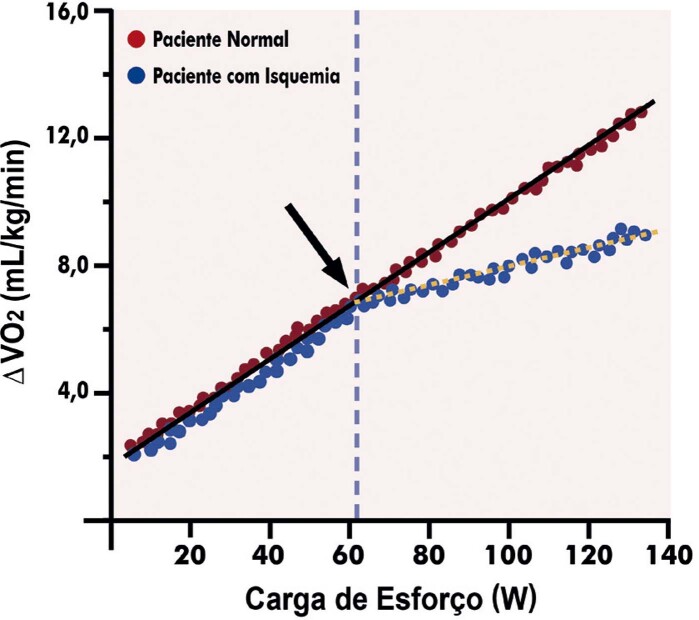

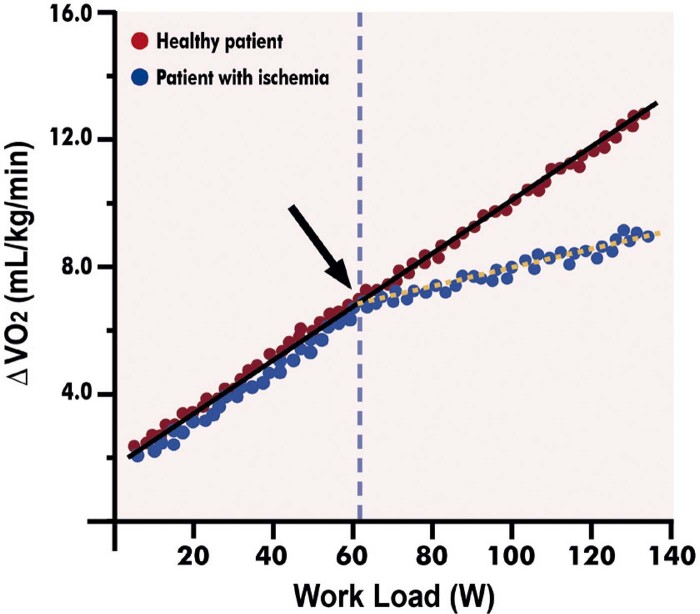

3.9. Relação Delta VO 2 e Delta Carga de Trabalho (ΔVO 2 /ΔWR) 85

3.10. Ponto Ótimo Cardiorrespiratório 85

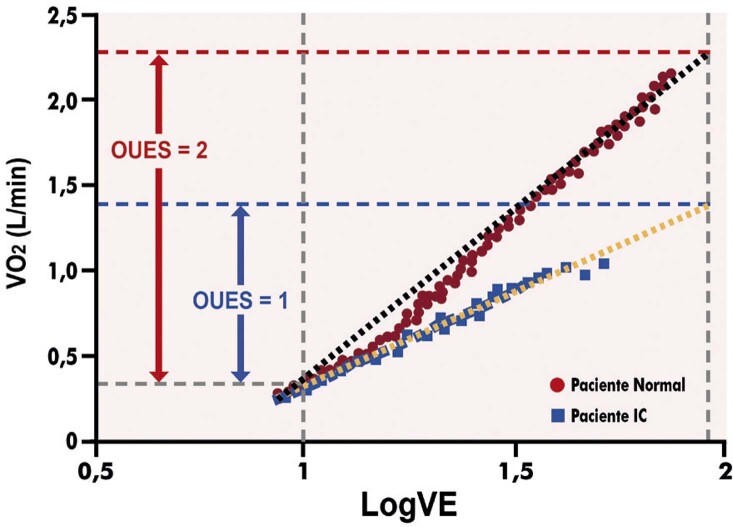

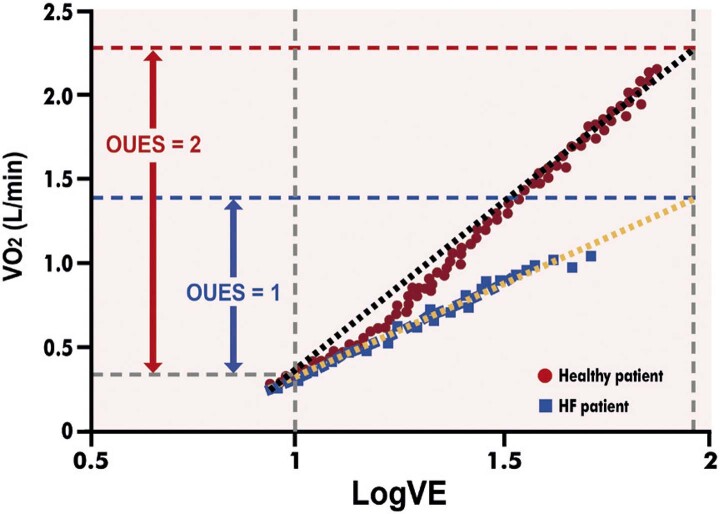

3.11. Inclinação da Eficiência da Captação do Oxigênio (OUES) 86

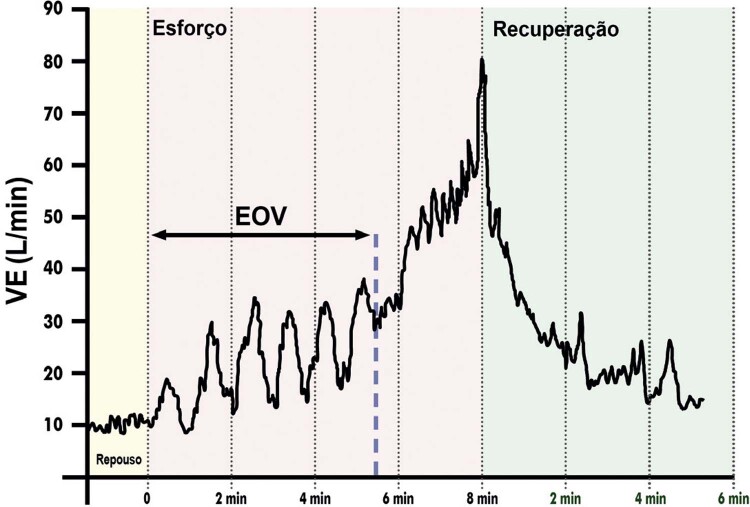

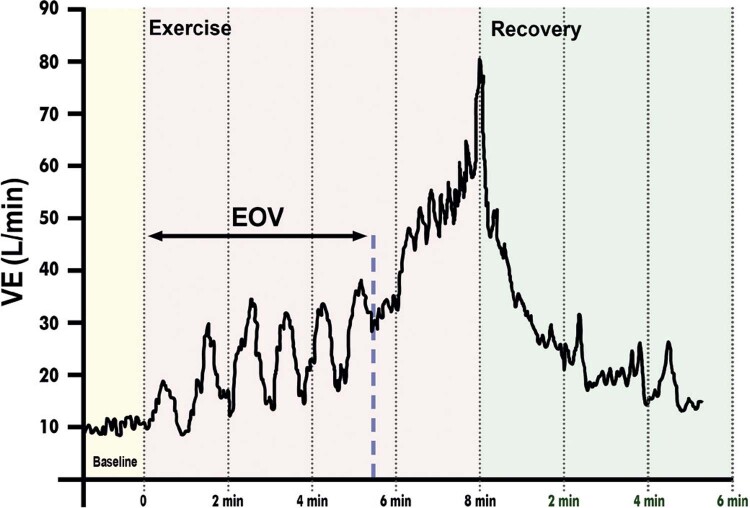

3.12. Ventilação Oscilatória ao Esforço 86

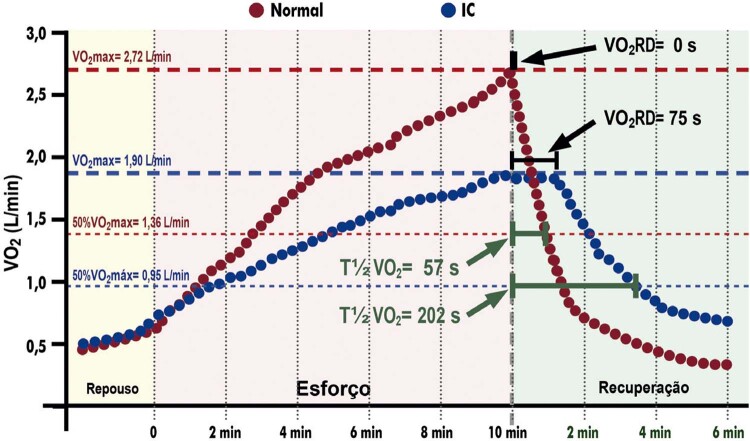

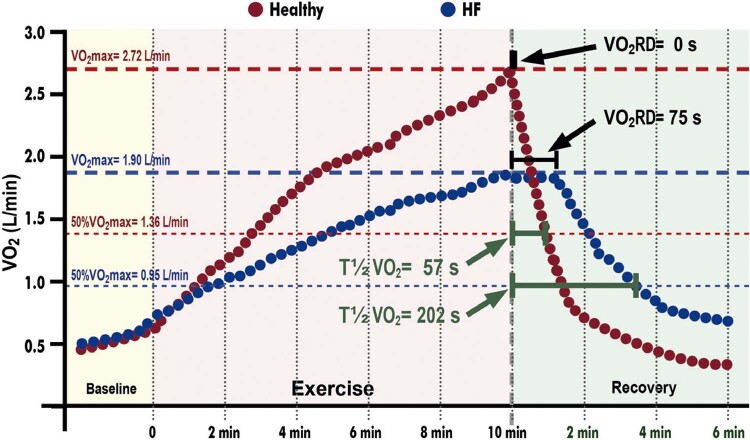

3.13. Tempo de Recuperação do Consumo de Oxigênio 87

3.14. Potência Circulatória e Potência Ventilatória 87

3.15. Valores de Referência de Variáveis do TCPE 88

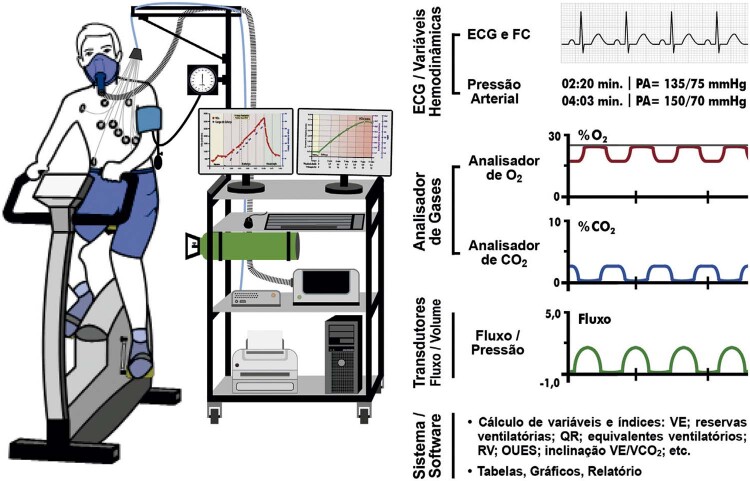

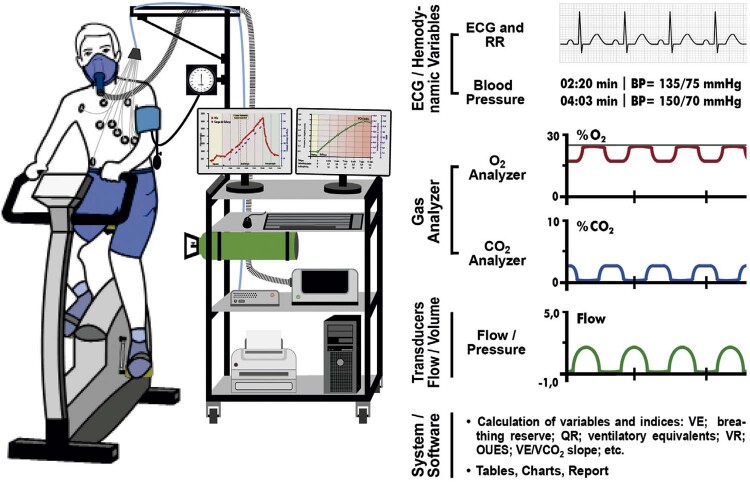

4. Equipamentos e Metodologia 88

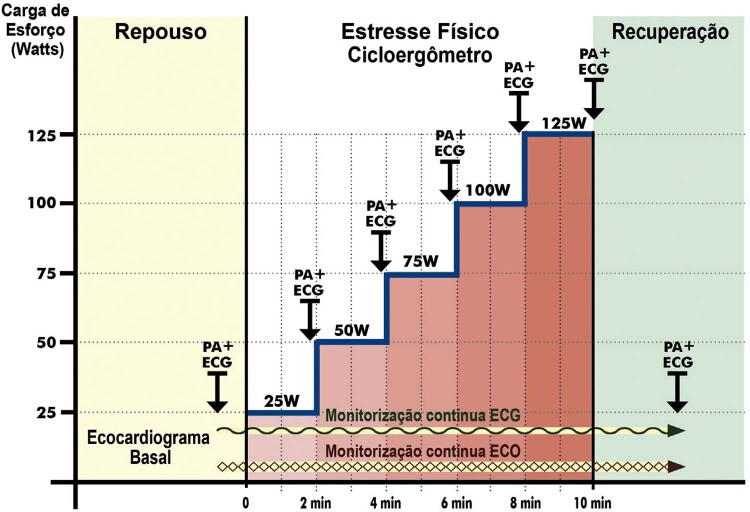

4.1. Ergômetros 88

4.2. Transdutores de Fluxo ou Volume de Ar 88

4.3. Analisadores de Gás 88

4.4. Medições das Trocas Gasosas 88

4.5. Procedimentos de Calibração, Controle de Qualidade e Higienização 88

4.6. Protocolos 90

4.7. Software para Análise dos Dados 90

4.8. Recomendações Prévias aos Pacientes 90

5. Realização do TCPE em Algumas Situações Específicas 90

5.1. Insuficiência Cardíaca 90

5.2. Doença Arterial Coronariana 90

5.3. Miocardiopatia Hipertrófica 91

5.4. Valvopatias 91

5.5. Pneumopatias 91

5.5.1. Doença Pulmonar Obstrutiva Crônica 91

5.5.2. Doença Vascular Pulmonar 92

5.6. Diagnóstico Diferencial da Dispneia 93

5.7. Atletas e Exercitantes 94

5.8. Reabilitação Cardiorrespiratória 94

6. Interpretação e Elaboração do Laudo do TCPE 94

Parte 4 – Teste Ergométrico Associado aos Métodos de Imagem em Cardiologia 94

1. Estresses Cardiovasculares Associado aos Métodos de Imagem em Cardiologia 94

1.1. Cintilografia Perfusional Miocárdica 94

1.1.1. Metodologia do Estresse Físico – Teste Ergométrico 94

1.1.1.1. Contraindicações à Realização do Estresse Físico na CPM 95

1.1.1.2. Orientações para Marcação do Estresse Físico na CPM 95

1.1.1.3. Realização do Estresse Físico na CPM 95

1.1.1.4. Interpretação do TE na CPM 96

1.1.2. Metodologia das Provas Farmacológicas 96

1.1.2.1. Fármacos que Promovem Vasodilatação 96

1.1.2.1.1. Dipiridamol 96

1.1.2.1.2. Adenosina 96

1.1.2.2. Fármacos que Promovem a Elevação do Consumo de Oxigênio Miocárdico 97

1.1.3. Metodologia do Estresse Combinado 97

1.1.4. Novos Fármacos 97

1.2. Ecocardiografia sob Estresse 97

1.2.1. Metodologia 98

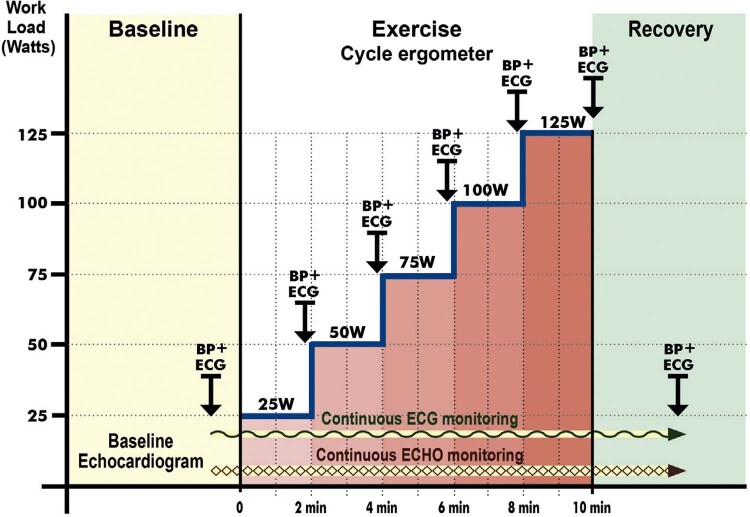

1.2.1.1. Metodologia do Estresse Físico 98

1.2.1.2. Metodologia do Estresse Farmacológico 98

1.2.1.2.1. Dobutamina 98

1.2.1.2.2. Vasodilatadores 99

1.2.1.3. Agentes de Realce Ultrassonográfico 99

Referências 100

Parte 1 – Indicações, Aspectos Legais e Formação em Ergometria

1. Introdução

O Teste Ergométrico ou Teste de Exercício (TE) é um exame médico, complementar e rotineiro na prática clínica/cardiológica, no qual o indivíduo é submetido a um esforço físico programado e individualizado, com a finalidade de avaliar as respostas clínica, hemodinâmica, autonômica, eletrocardiográfica, metabólica indireta e eventualmente enzimática. 1 , 2 Recebe a denominação de Teste Cardiopulmonar de Exercício (TCPE) quando, ao realizar o TE, são feitas a avaliação dos parâmetros ventilatórios e a análise dos gases expirados. 3 A denominação Ergometria contempla o TE e o TCPE.

Em linhas gerais, o TE e TCPE:

– Contribuem para o diagnóstico e prognóstico de doenças cardiovasculares, fornecem orientações para a definição das intervenções terapêuticas, auxiliam na adoção de providências relacionadas à prevenção e à prática esportiva, são utilizados nas avaliações periciais médicas e fornecem subsídios para o acompanhamento evolutivo de pacientes. 1 , 3 - 5

– Apresentam alta reprodutibilidade, excelência reconhecida em termos de custo-benefício e custo-efetividade, são passíveis de realização em todas as regiões do Brasil. 1 , 6

– São reconhecidos e legalmente registrados como Área de Atuação em Ergometria pela Comissão Mista de Especialidades médicas. 7

– Têm grande importância como estressor cardiovascular associado aos métodos de imagem em cardiologia, especialmente visando ao diagnóstico e prognóstico da doença cardiovascular isquêmica. 8 , 9

Esta diretriz consolida e atualiza, em um único documento, todas as informações e recomendações presentes nas diretrizes anteriores da SBC sobre o TE e TCPE, abordando novos aspectos não considerados nos documentos anteriores, destacando-se como importantes novidades as informações relacionadas aos exames em população adulta e as necessárias adequações do exame em cenários de síndromes respiratórias agudas. 1 , 2 Esta diretriz será relevante fonte de consultas para os cardiologistas em geral e, de forma especial, para os médicos em formação e atuantes na área de Ergometria.

2. Indicações e Contraindicações do TE e TCPE, Inclusive Associados a Imagens

2.1. Indicações Gerais do TE

O TE está amplamente disponível no Brasil, a um custo acessível e com reconhecida utilidade na prática clínica. 10 , 11 É uma importante ferramenta de diagnóstico, para estratificação de risco e determinação de prognóstico em pacientes com doença cardíaca conhecida ou suspeita. Permite avaliar a repercussão das doenças cardiovasculares e a eficácia de terapêuticas implementadas.

Indicações e objetivos gerais do TE: 1 , 6 , 12 - 18

1) Avaliar sintomas esforço-induzidos.

2) Determinar capacidade funcional.

3) Avaliar o comportamento da pressão arterial.

4) Avaliar o comportamento da frequência cardíaca.

5) Detectar isquemia miocárdica.

6) Reconhecer as arritmias cardíacas quanto ao tipo, densidade e complexidade.

7) Avaliar o comportamento das canalopatias ao esforço.

8) Diagnosticar e estabelecer o prognóstico em determinadas doenças cardiovasculares.

9) Avaliação de indicação de intervenções terapêuticas.

10) Avaliar os resultados de intervenções terapêuticas.

11) Avaliação pré-operatória.

12) Avaliar a aptidão cardiorrespiratória e o condicionamento físico.

13) Contribuir para prescrição de exercícios físicos, inclusive na reabilitação cardiopulmonar.

14) Fornecer subsídios para exames admissionais, periódicos e perícia médica.

O TE pode ser realizado em situações clínicas e doenças nas quais se deseje verificar as condições citadas, respeitando as contraindicações relativas e absolutas.

2.2. Indicações do TE em Situações Clínicas Específicas

Em determinadas situações clínicas específicas, o TE teve sua efetividade estudada e testada, permitindo a determinação do grau e o nível de recomendação de suas indicações, a serem apresentadas nas próximas sessões. 6 , 12 - 14 , 17 , 19

2.2.1. Indicações do TE na Doença Arterial Coronariana

A doença arterial coronariana permanece como uma das principais doenças por sua morbidade e mortalidade, estimando-se que a prevalência de angina entre 65 a 84 anos seja de 12% a 14% nos homens e 10% a 12% nas mulheres. No Brasil, cerca de 30% das mortes são de causa cardiovascular. 20

TE está indicado na investigação de dor precordial de provável origem cardíaca devido a sua relevância, ampla disponibilidade e custo-efetividade, sendo referendado como a escolha ideal pelo Choosing Wisely . 21

A prevalência de DAC assintomática e isquemia silenciosa varia amplamente dependendo da população estudada. Assintomáticos diabéticos apresentam risco relativo (RR) de 2,0 para DAC e a prevalência de TE positivo é de aproximadamente 23% nesses pacientes. 22 , 23

O diagnóstico de isquemia miocárdica silenciosa permite realizar intervenções visando à redução de risco de eventos futuros, inclusive morte. 24

O TE é recomendado para estratificação de risco dos pacientes com DAC estável, definição de prognóstico, eficácia de intervenções e investigação de mudança no quadro clínico. 25 - 27

Mesmo com um TE não isquêmico, os pacientes com suspeita de DAC podem se beneficiar da estratificação de risco aprimorada pelo TE, por meio de variáveis de prognóstico, tais como sintomas esforço-induzidos, capacidade funcional, resposta pressórica e cronotrópica, função autonômica e resposta musculoesquelética. 28

O TE é fundamental em pacientes com DAC para a prescrição inicial de exercícios e subsequentes ajustes na programação de reabilitação cardiovascular ( Tabela 1 ). 17 , 29 , 30

Tabela 1. – Indicações do TE na doença arterial coronariana sintomática e assintomática .

| Indicação | GR | NE |

|---|---|---|

| Pacientes com probabilidade pré-teste intermediária para DAC incluindo aqueles com bloqueio de ramo direito ou infradesnivelamento do segmento ST <1 mm no ECG de repouso 14 , 31 | I | A |

| Diagnóstico diferencial de dor torácica em paciente de baixo risco, estável clínica e hemodinamicamente (após 9 a 12 horas), sem sinais de isquemia eletrocardiográfica e/ou disfunção ventricular e com marcadores sorológicos de necrose normais, na unidade de dor torácica 32 , 33 | I | A |

| Prescrição de exercício e avaliação seriada em programa de reabilitação 29 , 30 | I | A |

| Sintomas atípicos e anormalidades no ECG de repouso (interpretável) para liberação de atividade física de alta intensidade 17 , 34 | I | A |

| Síndromes coronarianas agudas após, no mínimo, 72 horas de completa estabilização clínica e hemodinâmica para estratificação de risco e definição terapêutica 33 , 35 | I | B |

| Pós IAM, não complicado, antes da alta hospitalar, para estratificação de risco e adequação terapêutica 36 , 37 | I | B |

| Avaliação prognóstica na DAC estável* 38 , 39 | I | B |

| Investigação de DAC em pacientes sintomáticos, diabéticos e com ECG interpretável 40 - 42 | I | B |

| Suspeita de angina vasoespástica 43 , 44 | IIa | B |

| Estratificação de risco e definição terapêutica em pacientes de alto risco para DAC 14 , 45 | IIa | B |

| Avaliação de assintomáticos com três ou mais fatores de risco clássicos 46 , 47 | IIa | B |

| Decisão terapêutica em lesões coronarianas intermediárias detectadas na cineangiocoronariografia 14 , 26 | IIa | B |

| Avaliação da eficácia terapêutica farmacológica na DAC 27 , 48 | IIa | B |

| Investigação de alterações de repolarização ventricular (desde que infradesnivelamento <1 mm) no ECG de repouso 6 , 14 | IIa | B |

| Pacientes sintomáticos após revascularização miocárdica (cirurgia ou intervenção coronária percutânea) 49 , 50 | IIa | B |

| Avaliação de assintomáticos após revascularização miocárdica (cirurgia ou intervenção coronária percutânea) para estratificação de risco, ajuste terapêutico, liberação/prescrição de exercícios físicos, inclusive reabilitação 14 , 49 | IIa | B |

| Pré-operatório de paciente com risco intermediário ou alto de complicações** 51 , 52 | IIa | C |

| Investigação de DAC em pacientes com critérios eletrocardiográficos para sobrecarga ventricular esquerda com depressão do segmento ST <1 mm 53 , 54 | IIb | B |

| Avaliação funcional nos casos em que outro método tenha avaliado anatomia coronariana 6 , 14 | IIb | B |

| Perícia médica e/ou avaliação pela medicina do trabalho 55 , 56 | IIb | B |

| Baixa probabilidade de DAC para estratificação de risco cardiovascular 24 | IIb | C |

| Portador assintomático de lesão de TCE ou equivalente conhecido para acompanhamento evolutivo e ajuste/decisões terapêuticas 6 , 14 | IIb | C |

| Síndromes coronarianas agudas não estabilizadas clínica ou hemodinamicamente ou ainda com alterações eletrocardiográficas persistentes ou marcadores de necrose não normalizados 14 , 33 | III | B |

| Pesquisa de DAC em pacientes com BRE, WPW, ritmo de MP, depressão do segmento ST ≥1 mm no ECG de repouso e terapêutica com digitálicos 6 , 14 | III | B |

| Presença de lesão de TCE ou equivalente conhecido sintomático 6 , 14 | III | B |

| GR: grau de recomendação; NE: nível de evidência; ECG: eletrocardiograma; IAM: infarto agudo do miocárdio; DAC: doença arterial coronariana; HAS: hipertensão arterial sistêmica; MP: marca-passo; BRE: bloqueio de ramo esquerdo; TCE: tronco de coronária esquerda; WPW: síndrome de Wolff-Parkinson-White. *Avaliação prognóstica/evolutiva da DAC poderá ser necessária anualmente, de acordo com a condição clínica. **Ver classificação do risco intrínseco da cirurgia de complicações cardíacas da 3ª Diretriz de Avaliação Cardiovascular Perioperatória da Sociedade Brasileira de Cardiologia. 51,52 | ||

2.2.2. Indicações do TE em Assintomáticos

O TE apresenta papel relevante na avaliação de pacientes assintomáticos por permitir determinar o prognóstico e o risco de futuras anormalidades através de suas variáveis (FC, pressão arterial, eletrocardiograma etc.). 57 , 58

A aptidão cardiorrespiratória (capacidade funcional) determinada no TE é considerada um marcador fundamental de saúde e definidor de metas terapêuticas e preventivas. Em pacientes assintomáticos com comorbidades, auxilia na prescrição de exercícios de modo a promover a saúde e o bem-estar. O TE é viável e seguro mesmo em pacientes com idade avançada e comorbidades significativas. 59 , 60

O TE também aprimora a estratificação de risco de um indivíduo assintomático quanto a estar fisicamente apto para desempenho de suas atividades físicas laborais, sem colocar em risco indevido a si mesmo ou a terceiros ( Tabela 2 ). 61

Tabela 2. – Indicações do TE em pacientes assintomáticos.

| Indicação | GR | NE |

|---|---|---|

| Avaliação de indivíduos com história familiar de DAC precoce (em mulheres <65 anos e em homens <55 anos) – realizar pelo menos um TE até os 40 anos 45 , 62 | I | B |

| Rastreamento de indivíduos com história de morte súbita em familiares de primeiro grau 55 , 63 | IIa | B |

| Avaliação de sedentários diabéticos para diagnóstico de sintoma moderado ou intenso esforço-induzido e/ou prescrição de exercício 41 , 64 , 65 | IIa | B |

| Indivíduos classificados como de alto risco pelo escore de Framingham 1 , 62 | IIa | B |

| Avaliação de indivíduo com ocupação de alto risco e/ou responsável pela vida de outros, tais como pilotos, motoristas profissionais, militares, policiais, bombeiros etc. 14 , 66 | IIa | B |

| Avaliação pré-participativa para atividades de lazer e esporte recreacional em indivíduos ≥60 anos 17 , 34 | IIa | C |

| Pré-operatório de paciente com história familiar de DAC precoce em cirurgia não cardíaca de médio e grande porte 52 , 67 | IIa | C |

| Considerar na avaliação pré-participação para atividades de lazer e esporte recreacional em indivíduos de 35 a 59 anos 17 , 34 | IIb | B |

| Paciente <35 anos, sem fator de risco cardiovascular, para início de programa de atividade física de intensidade leve ou moderada 34 | III | C |

| GR: grau de recomendação; NE: nível de evidência; DAC: doença arterial coronariana; TE: teste ergométrico. | ||

2.2.3. Indicações do TE em Atletas

A atividade física (AF) é definida como qualquer movimento corporal produzido pelo sistema musculoesquelético. O exercício ou treinamento físico é um programa de atividade física estruturada, repetitiva, com objetivo de recuperar, manter ou melhorar um ou mais componentes da aptidão física (cardiorrespiratório, morfológico, muscular, metabólico ou motor). O atleta é indivíduo de qualquer idade, amador ou profissional, que pratique regularmente exercícios físicos, com maior ênfase no desempenho e, eventualmente, participe de competições esportivas. 13 , 34

O TE fornece dados importantes para a cardiologia, medicina esportiva e preventiva quanto à saúde dos atletas de elite, atletas olímpicos, atletas profissionais, atletas competitivos, federados e/ou pertencentes a clubes esportivos, atletas masters e atletas recreativos (atividade de prazer e de lazer). É utilizado na avaliação pré-participação e permite detectar doenças pulmonares e cardiovasculares latentes (p. ex., asma esforço-induzida, hipertensão, isquemia, arritmias etc.), monitorar intervenções e realizar avaliação prognóstica ( Tabela 3 ). 13 , 17 , 34 , 68

Tabela 3. – Indicações do TE em atletas.

| Indicação | GR | NE |

|---|---|---|

| Realizar em indivíduos ≥60 anos ao iniciar atividade de alta intensidade, esportiva e competições esportivas 13 , 17 , 69 | I | B |

| Rastreamento de indivíduos com história de morte súbita em familiares de primeiro grau 13 , 17 , 70 | I | B |

| Indivíduo ≥35 anos com alto risco (escore clínico) em avaliação pré-participação para exercícios de alta intensidade e competições esportivas 13 , 17 , 34 | IIa | A |

| Indivíduos de 35-59 anos, considerar no início do programa de exercício de alta intensidade e competições esportivas 13 , 17 , 34 | IIa | B |

| História familiar de DAC precoce (em mulheres <65 anos e em homens <55 anos) – realizar pelo menos um TE até os 35 anos 13 , 17 , 34 | IIa | B |

| Atleta diabético para diagnóstico de sinais e sintomas esforço-induzidos, estratificação de risco e prognóstico 17 , 40 , 41 , 64 | IIa | B |

| No ajuste de carga de treinamento físico de atletas | III | C |

| Atleta em síndrome de excesso de treinamento sintomática | III | C |

| GR: grau de recomendação; NE: nível de evidência; DAC: doença arterial coronariana. | ||

2.2.4. Indicações do TE na Hipertensão Arterial Sistêmica

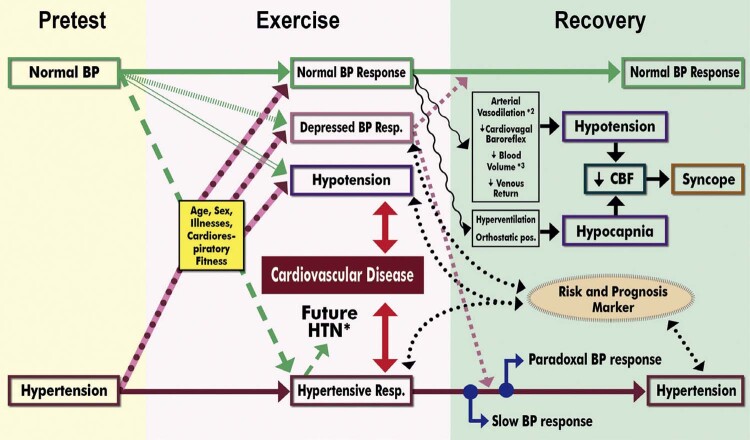

O comportamento da pressão arterial sistólica (PAS) durante o TE é considerado marcador de risco para desenvolvimento de hipertensão, morte por doença cardiovascular e risco de acidente vascular cerebral. 71 - 73 Dados recentes sugerem que a resposta da PA ao exercício de intensidade submáxima tem maior significado clínico e prognóstico do que a PA alcançada no exercício de intensidade máxima. O desempenho físico no TE influi na interpretação da resposta da PA ao exercício. Tanto a hipotensão quanto a PA exagerada servem como marcador prognóstico e indicador de necessidade de investigação de DCV subjacentes ( Tabela 4 ). 74 , 75

Tabela 4. – Indicações do TE na hipertensão arterial sistêmica .

| Indicação | GR | NE |

|---|---|---|

| Avaliação de hipertensos sintomáticos com ECG normal para investigação de DAC 27 , 77 , 78 | I | B |

| Comportamento da PA em pacientes com síndrome metabólica ou diabéticos 79 , 80 | IIa | B |

| Em hipertensos, para avaliação de aptidão cardiorrespiratória, estratificação de risco e liberação para prática esportiva 71 , 76 , 81 , 82 | IIa | B |

| Ajustes da terapêutica farmacológica anti-hipertensiva 83 - 85 | IIa | B |

| Avaliação do comportamento da PA em pacientes sob investigação de hipertensão 86 , 87 | IIa | B |

| Avaliação do comportamento pressórico em hipertensos com DAC para estratificação de risco, ajuste terapêutico e liberação para exercícios físicos 78 , 88 | IIa | B |

| Avaliação de idosos hipertensos para programa de atividade física 29 , 34 , 89 | IIa | C |

| Suspeita de hipotensão arterial esforço-induzida em hipertensos tratados 90 , 91 | IIa | B |

| Comportamento da PA em indivíduos com história familiar de HAS 71 | IIb | B |

| GR: grau de recomendação; NE: nível de evidência; DAC: doença arterial coronariana; HAS: hipertensão arterial sistêmica; PA: pressão arterial; ECG: eletrocardiograma. | ||

Em atletas submetidos ao TE, a resposta da PA indexada à carga de esforço foi superior à PASpico como preditora de mortalidade em homens saudáveis, sendo útil na triagem pré-participação. A resposta hipertensiva ao TE esteve associada ao desenvolvimento de hipertensão em atletas jovens. 76

2.2.5. Indicações do TE em Valvopatias

Na doença valvar, o TE deve ser realizado rotineiramente para esclarecimento de sintomas duvidosos, avaliação de indicadores que contribuam na decisão sobre intervenção e para liberação e prescrição de exercícios ( Tabela 5 ). 92 - 94 O TE é útil para desmascarar os pacientes “pseudoassintomáticos” e permite o acompanhamento seriado de assintomáticos. 94 As intervenções, cirúrgica ou transcateter, são indicadas em pacientes sintomáticos ou com sintomas esforço-induzidos. 94

Tabela 5. – Indicações do TE em valvopatias.

| Indicação | GR | NE |

|---|---|---|

| Em valvopatia leve e moderada, para confirmação de ausência de sintomas, esclarecimento de sintomas, avaliação da capacidade funcional e prescrição de exercícios físicos 93 , 94 , 96 , 97 | I | B |

| Na insuficiência mitral, para esclarecimento de sintomas, avaliação da capacidade funcional, indicação de intervenção e prognóstico 98 - 100 | IIa | A |

| EAo para esclarecimento de sintomas, indicação de intervenção e prognóstico 93 , 94 , 101 , 102 | IIa | A |

| EAo moderada e grave, em paciente assintomático, para avaliação de marcadores de mau prognóstico e indicação de intervenção 93 , 94 , 96 , 101 , 103 | IIa | A |

| No seguimento de IAo para esclarecimento de sintomas, avaliação de capacidade funcional e prognóstico 104 , 105 | IIa | B |

| EM assintomática ou presença de sintomas atípicos ou sintomas discordantes com o grau de estenose 14 , 106 , 107 | IIa | B |

| No seguimento de EAo grave assintomática pelo menos a cada 6 meses para detecção precoce de sintomas, avaliação funcional e indicação de intervenção 93 , 108 , 109 | IIa | B |

| EAo grave, assintomática, com FEVE normal em planejamento familiar para gestação 110 , 111 | IIa | B |

| Avaliação pós-intervenção valvar para esclarecimento de sintomas, avaliação da capacidade funcional, prognóstico e prescrição de exercício (incluindo reabilitação cardiovascular) 93 , 112 | IIa | B |

| Cirurgia não cardíaca para determinação do risco cirúrgico e capacidade funcional 52 , 67 , 113 | IIb | B |

| Nas estenoses ou insuficiências aórtica e mitral, assintomáticas, para determinar a capacidade funcional e prescrição de exercícios 17 , 29 , 114 | IIb | B |

| Investigação de DAC em pacientes com valvopatia grave 115 | III | B |

| EAo ou mitral grave sintomática 93 | III | C |

| GR: grau de recomendação; NE: nível de evidência; EAo: estenose aórtica; IAo: insuficiência aórtica; DAC: doença arterial coronariana; FEVE: fração de ejeção do ventrículo esquerdo. | ||

A prática de exercícios físicos requer avaliação de sintomatologia, capacidade funcional, características da lesão valvar e sua repercussão na função cardíaca. Indivíduos assintomáticos com lesões de gravidade moderada podem se exercitar intensamente se o TE revelar boa capacidade funcional e ausências de isquemia miocárdica, distúrbios hemodinâmicos e arritmias. 95

2.2.6. Indicações na Insuficiência Cardíaca e nas Cardiomiopatias

Na insuficiência cardíaca (IC) e nas cardiomiopatias, o TE é utilizado no esclarecimento de sintomas, avaliação da tolerância ao esforço/classe funcional, avaliação prognóstica, ajustes terapêuticos e prescrição de programas de exercício ( Tabela 6 ). 29 , 116

Tabela 6. – Indicações do TE na insuficiência cardíaca e nas cardiomiopatias .

| Indicação | GR | NE |

|---|---|---|

| Na IC e nas cardiomiopatias compensadas, para prescrição e adequação de programa de exercícios (incluindo programas de reabilitação cardiovascular)* 6 , 13 , 17 , 29 , 119 | IIa | B |

| Na cardiomiopatia hipertrófica e na IC compensada, em protocolo atenuado, para esclarecimento de sintomas, avaliação da capacidade funcional e marcadores prognósticos (sintomas, arritmia ventricular e resposta pressórica) 17 , 29 , 120 , 121 | IIa | B |

| Na cardiomiopatia hipertrófica, de forma seriada, para ajustes de programa de exercícios e atividade esportiva recreacional 6 , 13 , 17 , 29 , 121 | IIa | B |

| Pacientes recuperados e assintomáticos, após 3 a 6 meses de quadro agudo de miocardite, para liberação e prescrição de prática de exercícios 122 , 123 | IIa | B |

| Prescrição e adequação de programa de exercícios (incluindo reabilitação cardiovascular) em pacientes após transplante cardíaco* 13 , 29 , 124 , 125 | IIa | C |

| Na cardiomiopatia hipertrófica ou na IC compensada, de forma seriada, para avaliação do comportamento pressórico e de intervenções terapêuticas 14 , 18 , 119 , 121 | IIa | C |

| Reavaliação periódica após miocardite, nos primeiros 2 anos, para identificar progressão silenciosa da doença e estratificação de risco 115 , 123 , 126 , 127 | IIa | C |

| Seleção para transplante cardíaco pelo TE (com base nos valores de VO 2 estimados e não medidos)** 6 , 115 | III | B |

| Miocardite, pericardite aguda ou IC descompensada 6 , 115 | III | C |

| Diagnóstico de insuficiência cardíaca 6 , 115 | III | C |

| GR: grau de recomendação; NE: nível de evidência; IC: insuficiência cardíaca; VO 2 : consumo de O 2 . *Na indisponibilidade do TCPE. **As variáveis obtidas pelo TCPE são fundamentais para a indicação do transplante cardíaco, permitindo detectar com maior precisão os mecanismos responsáveis pela limitação ao esforço. | ||

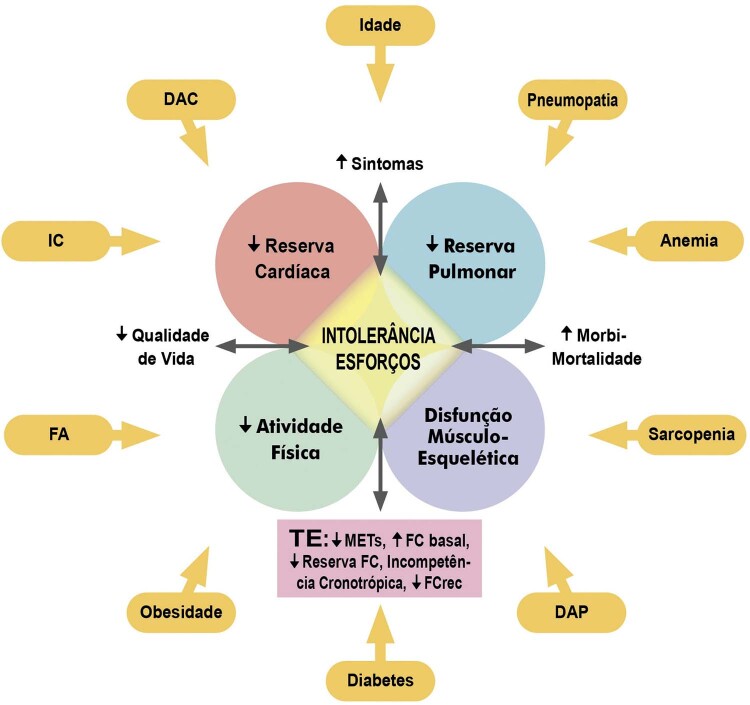

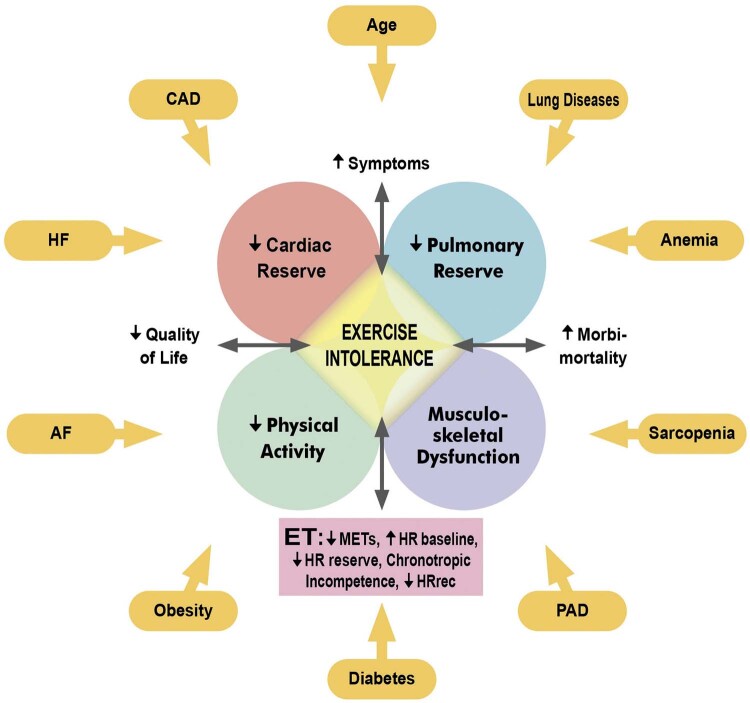

A intolerância ao exercício é uma manifestação típica de pacientes afetados por IC, sendo a classificação funcional e a resposta da FC no TE variáveis importantes de prognóstico. 117 , 118

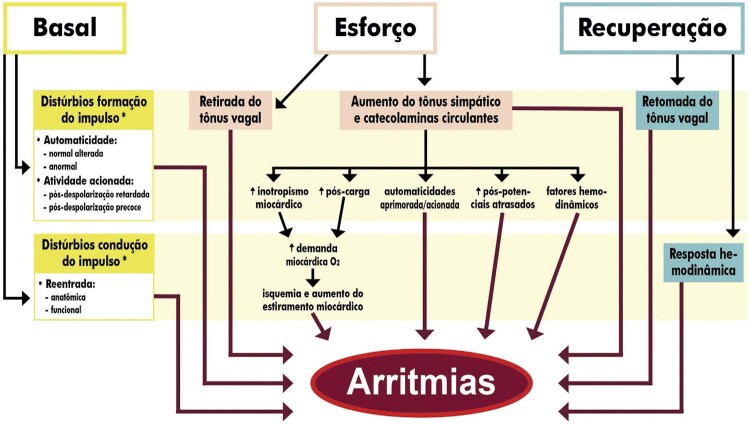

2.2.7. Indicações do TE no Contexto de Arritmias e Distúrbios de Condução

As arritmias esforço-induzidas são frequentemente causadas por diversas doenças cardiovasculares passíveis de avaliação pelo TE. Podem ser totalmente assintomáticas ou cursar com sintomas que variam de palpitações até síncope. O TE permite investigar a sintomatologia, diagnosticar e quantificar (densidade) as arritmias e estratificar o risco de morte súbita cardíaca (MSC). Apresenta, também, papel relevante nos distúrbios de condução atrioventricular e intraventricular na investigação de suas causas, repercussões e decisões terapêuticas ( Tabela 7 ). 63 , 128 - 132

Tabela 7. – Indicações do TE no contexto de arritmias e distúrbios de condução .

| Indicação | GR | NE |

|---|---|---|

| Palpitação, síncope, pré-sincope, equivalente sincopal, mal-estar indefinido ou palidez relacionada ao esforço físico e/ou recuperação 6 , 14 , 133 , 134 | I | B |

| Arritmia assintomática detectada em exame clínico/complementar, para avaliação do comportamento ao esforço e determinação de prognóstico 14 , 39 , 133 , 135 , 136 | I | B |

| No BAVT congênito, para avaliação da resposta ventricular e indicação de marca-passo 131 , 132 , 137 , 138 | I | B |

| Em pacientes com taquicardia ventricular catecolaminérgica, para avaliação de terapêutica farmacológica e indicação de cardiodesfibrilador implantável 132 , 138 , 139 | I | B |

| Na doença do nó sinusal, para avaliação da resposta cronotrópica* 14 , 133 , 134 | I | B |

| Na síndrome do QT longo (sintomática e assintomática), para confirmação diagnóstica, estratificação de risco, avaliação de potencial arritmogênico e de terapêutica 140 , 141 | I | B |

| Suspeita diagnóstica de taquicardia ventricular paroxística catecolaminérgica 115 , 132 , 138 , 139 | I | C |

| No BAVT congênito, para avaliação da resposta atrial e consequente escolha do tipo de marca-passo 131 , 132 , 134 , 138 | I | C |

| Eficácia da terapêutica farmacológica e/ou pós-ablação 131 - 134 , 142 | IIa | B |

| Indicação de implante de marca-passo 14 , 131 , 132 , 138 , 143 | IIa | B |

| Recuperado de parada cardiorrespiratória, estável clinicamente, para liberação e prescrição de exercício físico (recreacional e/ou reabilitação cardiovascular) 13 , 144 - 146 | IIa | B |

| Na síndrome de Brugada (sintomática e assintomática), para confirmação diagnóstica, estratificação de risco e avaliação de potencial arritmogênico e de terapêutica** 147 , 148 | IIa | B |

| Suspeita de incompetência cronotrópica 6 , 14 , 149 - 151 | IIa | B |

| Marca-passo com biossensor, para avaliação do comportamento da frequência cardíaca 131 , 132 , 134 , 137 , 138 , 152 | IIa | B |

| Avaliação de marca-passo, ressincronizador e/ou cardiodesfibrilador implantável, para ajustes de programação 131 , 132 , 134 , 137 , 138 , 152 | IIa | C |

| Rastreamento dos familiares de pacientes com síndrome do QT longo 13 , 140 , 153 , 154 | IIa | B |

| Na arritmia conhecida, controlada, para liberação e prescrição de exercício físico (recreacional e/ou reabilitação cardiovascular) 6 , 13 , 14 , 133 , 134 | IIa | C |

| Em assintomático com cardiomiopatia arritmogênica praticante de exercícios físicos, anualmente 17 , 155 - 157 | IIa | C |

| Na fibrilação atrial persistente (crônica) para avaliação terapêutica, controle da resposta ventricular, estratificação de risco e liberação para exercícios (inclusive reabilitação) 119 , 158 , 159 | IIa | C |

| Avaliação do comportamento de via anômala (pré-excitação) e do potencial arritmogênico 6 , 13 , 14 , 133 , 134 | IIb | B |

| Displasia arritmogênica do ventrículo direito para estratificação de risco e liberação de exercícios físicos 14 , 134 , 135 | IIb | B |

| Em portadores de desfibrilador cardíaco implantável para avaliação funcional, prognóstica, da eficácia terapêutica e liberação para programa de exercícios 131 , 132 , 160 , 161 | IIb | B |

| Rastreamento dos familiares de pacientes com Síndrome de Brugada** 13 , 134 , 147 , 162 | IIb | C |

| Portador de marca-passo de frequência fixa 115 , 133 | III | B |

| BAVT adquirido com baixa resposta da frequência ventricular 115 , 133 | III | B |

| Arritmia não controlada, sintomática ou com comprometimento hemodinâmico 115 , 133 | III | C |

| GR: grau de recomendação; NE: nível de evidência; BAVT: bloqueio atrioventricular total. *Contraindicação absoluta na presença de bloqueio sinoatrial total. **Utilizando derivações precordiais altas e recuperação passiva. | ||

2.2.8. Indicações do TE em Outras Condições Clínicas

A Tabela 8 apresenta outras condições clínicas para as quais o TE é recomendado, visando a avaliação funcional, prescrição de exercícios físicos e ajustes terapêuticos.

Tabela 8. – Indicações do TE em outras condições clínicas reconhecidas .

| Indicação | GR | NE |

|---|---|---|

| Assintomáticos com artéria coronária de origem anômala, para estratificação de risco, definição da conduta terapêutica e para liberação de exercícios físicos/atividades esportivas 13 , 17 , 34 | IIa | B |

| 3 meses após correção cirúrgica de artéria coronária de origem anômala, se assintomático, para liberação de exercícios físicos/atividade esportiva 13 , 17 , 29 , 163 | IIa | C |

| Ponte miocárdica para estratificação de risco, decisão terapêutica e liberação para exercícios físicos 13 , 17 , 29 , 163 , 164 | IIa | C |

| Cardiomiopatia não compactada de VE, assintomática, FEVE ≥40%, em programa de exercícios de baixa a moderada intensidade 17 , 127 , 165 | IIa | C |

| Na doença de Parkinson, para avaliação da tolerância ao esforço e liberação/prescrição de exercícios 19 , 166 , 167 | IIa | B |

| Na anemia falciforme, para avaliar capacidade funcional, estratificação de risco e liberação/prescrição de exercícios 168 - 170 | IIa | C |

| Paciente em tratamento oncológico, para liberação e prescrição de exercícios (inclusive reabilitação) 171 , 172 | IIa | C |

| Avaliação de risco e prognóstico após efeitos colaterais do tratamento de câncer 173 , 174 | IIb | C |

| Na doença arterial periférica, para avaliar claudicação, quantificar a isquemia, estratificar o risco e decisão terapêutica 175 , 176 | I | B |

| Na doença arterial periférica, para avaliar a capacidade funcional, prescrever e adequar programa de exercícios físicos 176 , 177 | I | B |

| Prescrição e adequação de programa de exercícios (incluindo reabilitação cardiovascular) em pacientes em hemodiálise e pós-transplante renal 178 , 179 | IIb | C |

| Aneurisma de aorta ou em outras artérias, assintomático, sem critérios para intervenção, para ajustes terapêuticos (p. ex., otimização tratamento anti-hipertensivo) e liberação/prescrição de exercícios (incluindo reabilitação) 180 | IIa | C |

| Recuperados de acidente vascular cerebral ou ataque isquêmico transitório, estável clinicamente, para ajustes terapêuticos (p. ex., otimização de tratamento anti-hipertensivo) e liberação/prescrição de exercícios 181 | IIb | C |

| No adulto com cardiopatia congênita, estável clinicamente (classe funcional I e II), para prescrição e adequação de programa de exercícios 17 , 182 , 183 | IIb | B |

| GR: grau de recomendação; NE: nível de evidência; VE: ventrículo esquerdo; FEVE: fração de ejeção do ventrículo esquerdo. | ||

2.3. Contraindicações Relativas e Absolutas

O TE geralmente é bem tolerado e seguro quando adequadamente indicado e realizado. Entretanto, situações clínicas específicas podem aumentar os riscos para eventuais complicações, exigindo intervenções médicas imediatas ( Tabela 9 ). O risco de morte cardíaca súbita encontra-se em torno de 1 em 10.000 TE. 6 , 184 , 185

Tabela 9. – Principais eventos e complicações durante o TE.

| Evento | Frequência | Comentários |

|---|---|---|

| Morte súbita cardíaca | 1 para 10.000 exames | Dependente do quadro clínico e comorbidades. 6 , 184 , 185 |

| Taquicardia ventricular esforço-induzida | 0,05-2,3% | Risco aumentado de ocorrência se arritmias ventriculares prévias. Risco aumentado de morte por DCV e por todas as causas. 135 , 186 , 187 Ocorrência frequente na suspeita de TV polimórfica catecolaminérgica, TV da via de saída do ventrículo direito e TV fascicular. 63 , 130 , 188 |

| Taquicardia supraventricular paroxística | 3,4-15% | Risco aumentado de desenvolver FA. 189 Quando reentrante, geralmente exige terapia medicamentosa para interrupção. 129 , 142 , 190 |

| Extrassistolia ventricular esforço-induzida | 2-20% | Quando frequente, risco aumentado de mortalidade (por todas as causas e por DCV) e eventos cardiovasculares. 191 - 195 Mais comum em pacientes com DAC: 7% a 20%. 196 |

| Extrassistolia supraventricular esforço-induzida | 4-25% | Ocorrem em até 10% dos pacientes aparentemente saudáveis e em até 25% dos com DAC. Não está associada a mortalidade cardíaca ou IAM. 189 , 197 , 198 Em idosos, associa-se a maior risco de FA/FluA. 199 , 200 |

| Fibrilação/flutter atrial esforço-induzidos | <1% | Costumam causar repercussão hemodinâmica se a resposta ventricular for exacerbada. 197 , 201 |

| Bloqueio intermitente do ramo esquerdo | 0,4-0,5% | DAC e IC são as causas mais prevalentes. Maior risco de mortalidade por todas as causas e eventos cardiovasculares. 202 , 203 |

| Bloqueio intermitente do ramo direito | 0,25% | Geralmente associado à DAC. 202 - 204 |

| Bradiarritmia/BAVT esforço-induzidos | <0,1% | Na disfunção do nó sinusal, podem ocorrer sintomas de IC e angina. 133 Na bradicardia sinusal esforço-induzida, pode ocorrer síncope devido ao reflexo de Bezold-Jarisch. 205 , 206 BAVT esforço-induzido pode estar associado à isquemia transitória ou doença degenerativa grave do sistema de condução. 207 , 208 |

| Síndrome coronariana aguda | 0,1-0,5% | Requer interrupção imediata do esforço. 6 , 209 , 210 |

| DCV: doença cardiovascular; BAVT: bloqueio atrioventricular avançado/total; DAC: doença arterial coronariana; IC: insuficiência cardíaca; TV: taquicardia ventricular; IAM: infarto agudo do miocárdio; FA: fibrilação atrial; FluA: flutter atrial. | ||

2.3.1. Contraindicações Relativas do TE/TCPE

São situações clínicas de alto risco para a realização do TE/TCPE que exijam a adoção de eventuais condutas preventivas e terapêuticas ( Tabela 10 ). Tais medidas incluem a realização do TE exclusivamente em ambiente hospitalar e cuidados especiais: adequação de protocolos e carga de esforço a ser atingida no TE, rigorosa observação de sintomas, medições mais frequentes da pressão arterial, presença de pessoal e equipamento para reprogramação de marca-passo/CDI.

Tabela 10. – Contraindicações relativas e eventuais condutas no TE/TCPE 1,6,12-17 .

| Ambiente hospitalar + Cuidados especiais | Cuidados especiais |

|---|---|

| Dor torácica aguda: realizar exclusivamente em hospital, idealmente em unidade de dor torácica, seguindo rigorosamente o protocolo | Cardiomiopatia hipertrófica não obstrutiva |

| Estenoses valvares graves em assintomáticos* | Marca-passo unicameral, ventricular, sem resposta de frequência (modo estimulação VVI) |

| Insuficiências valvares graves* | Insuficiência cardíaca compensada avançada (classe III da NYHA) |

| IAM não complicado (a partir do 5º dia e estável clinicamente) | AVC ou ataque isquêmico transitório recente (menos que 2 meses) 9 |

| Angina instável após 72 horas de estabilização* | Aneurisma de aorta ou em outras artérias, sem critérios para intervenção |

| Doença conhecida do tronco da coronária esquerda ou equivalente, em assintomático* | FA ou FluA assintomáticos detectados na avaliação pré-teste, com paciente informando desconhecimento da arritmia** |

| Suspeita de arritmias complexas (taquiarritmias e bradiarritmias), QT longo e síndrome de Brugada | FA (persistente ou crônica) ou FluA crônico com FC elevada em repouso** |

| Síncope por provável etiologia arritmogênica ou suspeita de bloqueio atrioventricular de alto grau ou total esforço-induzido | Gravidez*** |

| Insuficiência renal dialítica | |

| Cardiodesfibrilador implantado (CDI) | |

| Cardiopatias congênitas complexas acianóticas | |

| Hipertensão pulmonar importante ou sintomática* | |

| Cardiomiopatia hipertrófica obstrutiva com gradiente de repouso grave* | |

| Anemia grave (hemoglobina <8,0g/dL)** 211 , 212 | |

| FA: fibrilação atrial; FLuA: flutter atrial; FC: frequência cardíaca. *Situação em que o risco/benefício do exame deverá ser criteriosamente avaliado. **Situação em que o risco/benefício do exame deverá ser criteriosamente avaliado e provavelmente resultará na decisão de adiar ou cancelar o exame. ***Em nível submáximo de esforço, grávidas em situações específicas (p. ex., valvopatias e cardiopatias congênitas), após exclusão das contraindicações clínicas e obstétricas absolutas. Não é recomendado como exame de rotina. 213,214 | |

2.3.2. Contraindicações Absolutas do TE/TCPE

São consideradas contraindicações absolutas, não devendo realizar o TE e o TCPE, a presença das situações constantes no Quadro 1 . 1 , 6 , 12 - 17

Quadro 1. – Contraindicações absolutas do TE e TCPE.

| Contraindicações absolutas do TE e TCPE |

|---|

| – Embolia pulmonar aguda ou infarto pulmonar |

| – Enfermidade aguda, febril ou grave |

| – Deficiência mental ou física que leva à incapacidade de se exercitar adequadamente |

| – Intoxicação medicamentosa |

| – Distúrbios hidroeletrolíticos e metabólicos não corrigidos |

| – Bloqueio atrioventricular de risco para eventos/complicações* |

| – Pressão arterial sistólica persistente em repouso ≥180 mmHg ou pressão arterial diastólica >110 mmHg** |

| – Crise/urgência hipertensiva** |

| – Hipertireoidismo descontrolado |

| – Deslocamento recente de retina, em fase de recuperação*** |

| – Cardiopatias congênitas cianóticas descompensadas |

| – Infarto agudo do miocárdio antes de 5 dias ou com complicações |

| – Angina instável |

| – Arritmias cardíacas não controladas |

| – Estenose aórtica grave sintomática |

| – Insuficiência cardíaca descompensada |

| – Miocardite aguda ou pericardite |

| – Dissecção aguda da aorta |

| – Aneurisma de aorta ou em outras artérias com indicação de intervenção |

| – Doença pulmonar descompensada |

| – Diabetes mellitus descompensado**** |

| *Considera-se como de risco para eventos/complicações: bloqueio atrioventricular de segundo grau tipo II; bloqueio AV 2:1; bloqueio avançado/alto grau; bloqueio atrioventricular de terceiro grau/total (exceto bloqueio atrioventricular total congênito). **Crise hipertensiva: elevação aguda da pressão arterial (PA) sistólica ≥180 mmHg e/ou PA diastólica ≥120 mmHg, que pode resultar ou não em lesões de órgãos-alvo (LOA), que é dividida em urgência hipertensiva (elevação da PA sem LOA e sem risco de morte iminente; isso permite a redução da PA em 24 a 48 horas) e emergência hipertensiva (elevação da PA com LOA aguda ou em progressão e risco imediato de morte; requer redução rápida e gradual da PA em minutos a horas, com medicamentos intravenosos). 215 ***Para retorno à atividade física, principalmente em carga moderada/alta, são necessárias a avaliação e a liberação por parte do oftalmologista. 216,217 ****Caso o paciente com diabetes tipo II tenha feito o automonitoramento da glicemia no pré-teste ou no dia do exame, suspender exercícios físicos se glicemia >300 mg/dL (16,7 mmol/L). Caso o paciente com diabetes tipo I tenha feito o automonitoramento da glicemia, suspender exercícios se glicemia >350 mg/dL; se entre 251-350 mg/dL, sugere-se avaliação prévia de presença de cetonas, pois caso em moderada a grande quantidade, deve-se também suspender o exame. 64,218 |

2.4. Indicações do TCPE

2.4.1. Indicações Gerais do TCPE

As indicações gerais para a realização do TCPE são as mesmas relacionadas ao TE, principalmente quando há necessidade de adicionar as variáveis ventilatórias e metabólicas ( Quadro 2 ).

Quadro 2. – Indicações gerais do TCPE 3,5,219-223 .

| Indicações gerais do TCPE |

|---|

| 1) Doenças e situações em que a adição da determinação direta dos parâmetros ventilatórios e a análise de gases no ar espirado contribuem para avaliação diagnóstica, estratificação de risco e estabelecimento de condutas preventivas e terapêuticas |

| 2) Determinação das causas limitantes do desempenho cardiorrespiratório e mecanismos fisiopatológicos envolvidos |

| 3) Diagnóstico diferencial de dispneia (asma esforço-induzida, IC, DPOC etc.) |

| 4) Doenças cardiovasculares visando ao diagnóstico, prognóstico e ajustes terapêuticos (DAC, CC, IC etc.) |

| 5) Seleção de candidatos ao transplante cardíaco |

| 6) Nas doenças pulmonares (DPOC, asma, enfisema, intersticiais etc.) visando ao diagnóstico, prognóstico e ajustes terapêuticos |

| 7) Resposta terapêutica na hipertensão pulmonar e fibrose cística |

| 8) Outras situações: |

| – Pré-operatório de cirurgia não cardíaca em pneumopata |

| – Avaliação após transplante de pulmão, coração e coração-pulmão |

| – Seleção de modalidade esportiva em atleta competitivo |

| – Teste seriado para ajustes de intensidade de cargas de treinamento em atletas competitivos de atividades predominantemente aeróbicas |

| – Avaliação pericial/medicina do trabalho |

| – Avaliação e prescrição de exercícios para reabilitação cardiovascular, pulmonar e metabólica |

| DPOC: doença pulmonar obstrutiva crônica; CC: cardiopatia congênita; DAC: doença arterial coronariana; IC: insuficiência cardíaca. |

2.4.2. Indicações do TCPE em Situações Clínicas Específicas

Situações clínicas com evidências científicas que possibilitam determinar o grau de recomendação do TCPE são apresentadas na Tabela 11 .

Tabela 11. – Indicações específicas do TCPE.

| Indicação | GR | NE |

|---|---|---|

| Intolerância ao esforço e diagnóstico diferencial de dispneia 14 , 224 , 225 | I | A |

| Paciente pós-síndrome respiratória aguda (incluindo COVID-19), para investigação de dispneia, fadiga crônica e/ou intolerância ao esforço 226 - 228 | I | B |

| Paciente pós-síndrome respiratória aguda (incluindo COVID-19), para determinação da aptidão cardiorrespiratória e liberação/prescrição de exercícios físicos (incluindo reabilitação) 13 , 226 , 227 | I | B |

| Avaliação de broncoespasmo esforço-induzido (associado à prova espirométrica pré e pós-esforço) 219 , 229 - 231 | IIa | B |

| Na IC estável, para determinação da aptidão cardiorrespiratória, estratificação de risco, ajustes terapêuticos e liberação/prescrição de exercícios físicos (incluindo reabilitação) 14 , 232 , 233 | I | A |

| Na IC, para indicação de implante de dispositivo de suporte ventricular ou transplante cardíaco 3 , 14 , 224 , 232 , 234 , 235 | I | B |

| Paciente com DAC, para determinação da aptidão cardiorrespiratória, estratificação de risco, ajustes terapêuticos e liberação/prescrição de exercícios físicos (incluindo reabilitação) 14 , 29 , 236 | I | B |

| Na suspeita de DAC, para investigação diagnóstica, estratificação de risco e decisão terapêutica 237 , 238 | IIa | B |

| Estenose aórtica grave assintomática, para orientar a decisão terapêutica 14 , 93 , 239 , 240 | IIa | B |

| Na doença valvar estável, para determinação da aptidão cardiorrespiratória, ajustes terapêuticos e liberação/prescrição de exercícios físicos (incluindo reabilitação) 13 , 17 , 29 , 163 | IIa | B |

| Doença valvar com quadro clínico não correspondente aos achados ecocardiográficos (exceto na estenose aórtica) 14 , 92 - 94 , 240 | IIa | C |

| Adulto com CC, para avaliação de sintomas, decisões terapêuticas, estratificação de risco e liberação/prescrição de exercícios físicos (incluindo reabilitação) 17 , 30 , 241 , 242 | I | B |

| Avaliação pré-participação de atleta com CC 17 , 241 - 243 | IIa | B |

| Atletas competitivos após revascularização miocárdica ou correção de doença valvar, para estratificação de risco e liberação para retorno ao esporte 17 , 34 | IIa | B |

| Na cardiomiopatia hipertrófica, para avaliar aptidão cardiorrespiratória, estratificação de risco e liberação/prescrição de exercícios físicos (incluindo reabilitação) 14 , 121 , 244 , 245 | IIa | B |

| Hipertensão pulmonar, para diagnóstico e avaliação seriada (em intervalos de 6 a 12 meses) 14 , 246 | I | B |

| Hipertensão pulmonar para investigação de piora de sintomas e estratificação de risco 14 , 246 | IIa | B |

| Pós-embolia pulmonar aguda (após 3 meses), sintomática com discordância entre ventilação/perfusão na cintilografia pulmonar (V/Q scan ), para diagnóstico e seguimento da hipertensão pulmonar 247 | I | B |

| Paciente em tratamento oncológico para estratificação de risco e liberação / prescrição de exercícios (inclusive reabilitação) 248 , 249 | I | B |

| Pré-operatório de cirurgia não cardíaca em pacientes com baixa capacidade funcional (<4 METs) e/ou alto risco cardiovascular 14 , 250 | IIa | B |

| GR: grau de recomendação; NE: nível de evidência; CC: cardiopatia congênita; DAC: doença arterial coronariana; IC: insuficiência cardíaca. | ||

2.5. Indicações do TE/TCPE Associados a Métodos de Imagem

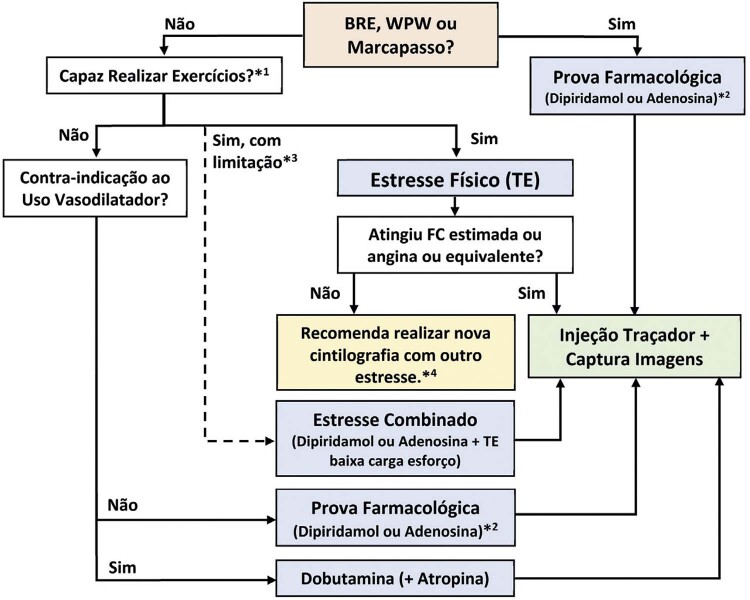

2.5.1. Cintilografia de Perfusão Miocárdica

A cintilografia de perfusão miocárdica (CPM) apresenta indicações nas diversas apresentações clínicas das doenças isquêmicas cardíacas e contribui para definição de sua gravidade. 9 Outras indicações são a avaliação de revascularização em pacientes com viabilidade miocárdica e no pré-operatório em situações específicas ( Tabela 12 ). 26 , 31 , 128 , 251 - 253

Tabela 12. – Escolha de estresse cardiovascular na cintilografia de perfusão do miocárdio 26,31,128,251-253 .

| Indicação | GR | NE |

|---|---|---|

| Estresse físico (TE) desde não haja limitação ou contraindicações ao esforço | I | A |

| Prova farmacológica (dipiridamol ou adenosina) nos casos de BRE, síndrome WPW e marca-passo | I | A |

| Prova farmacológica (dipiridamol, adenosina, dobutamina) na contraindicação de realização do estresse físico (TE) | I | A |

| Prova farmacológica (dipiridamol, adenosina, dobutamina) quando existir limitação para o estresse físico (TE) | IIa | A |

| Protocolo combinado: esforço físico de baixa carga de trabalho após a prova farmacológica (dipiridamol ou adenosina) | IIa | A |

| GR: grau de recomendação; NE: nível de evidência; BRE: bloqueio de ramo esquerdo; WPW: síndrome de Wolff-Parkinson-White; TE: teste ergométrico. | ||

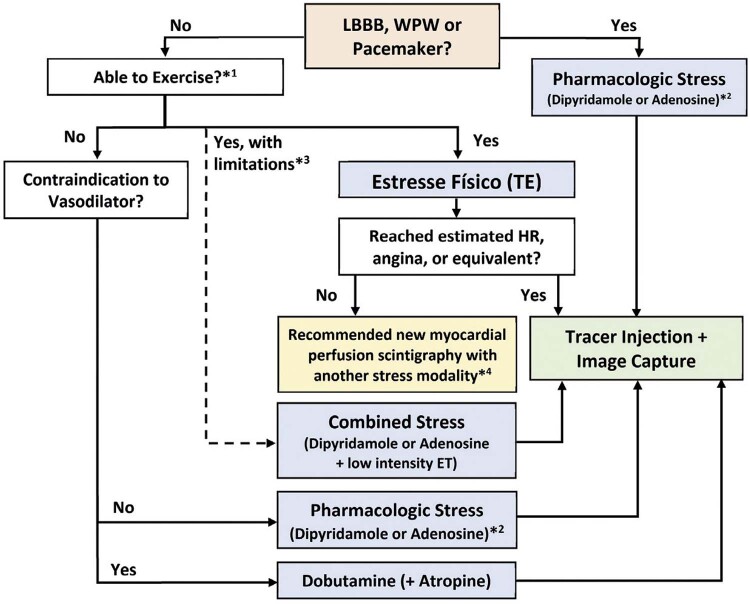

Pacientes sintomáticos com risco intermediário para cardiopatia isquêmica são os que mais se beneficiam da CPM para avaliação diagnóstica e prognóstica. Deve ser realizada, preferencialmente, em associação com o esforço físico (estresse físico) desde que o paciente tenha capacidade funcional acima de 5 METs e habilidade para execução do esforço no ergômetro disponível.

Os pacientes com bloqueio de ramo esquerdo (BRE), síndrome de Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) e marca-passo devem realizar a CPM com prova farmacológica (dipiridamol ou adenosina). 9

Entre as indicações para a realização de CPM, destacam-se pacientes com baixa capacidade funcional ou condições que impedem a interpretação quanto à presença de isquemia no TE e TCPE. A CPM apresenta melhores resultados na estratificação de risco da DAC em pacientes de alta probabilidade pré-teste de DAC. A CPM deverá ser realizada sob estresse farmacológico nos indivíduos com probabilidade pré-teste intermediária e ECG de repouso que impossibilita interpretar isquemia ou naqueles que não conseguem realizar esforço físico ( Tabela 13 ). 9

Tabela 13. – Critérios para indicação da cintilografia de perfusão do miocárdio em pacientes sintomáticos 9 .

| Indicação | GR | NE | Escore |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alta probabilidade pré-teste de DAC, independentemente do ECG de repouso interpretável e preencha os critérios para estresse físico* | I | A | 8 |

| Probabilidade pré-teste intermediária de DAC, com ECG de repouso não interpretável ou não preencha os critérios para estresse físico* | I | A | 9 |

| Probabilidade pré-teste intermediária de DAC, com ECG de repouso interpretável e preencha os critérios para estresse físico* | IIa | B | 7 |

| Baixa probabilidade pré-teste de DAC, com ECG de repouso não interpretável ou indivíduo que não preencha os critérios para estresse físico* | IIa | B | 7 |

| Baixa probabilidade pré-teste de DAC, com ECG de repouso interpretável e preencha os critérios para estresse físico* | III | C | 3 |

| GR: grau de recomendação; NE: nível de evidência; DAC: doença arterial coronariana; ECG: eletrocardiograma de 12 derivações; SCA: síndrome coronariana aguda. * Estresse físico: tenha capacidade funcional para realização de atividades físicas diárias acima de 5 METs e habilidade para execução do esforço no ergômetro disponível. | |||

Seguindo as recomendações da Diretriz Brasileira de Cardiologia Nuclear, adotamos o escore internacional de indicação: indicação apropriada, se o escore for de 7 a 9; possivelmente apropriada, se o escore for de 4 a 6; raramente apropriada, com escore de 1 a 3. 9

Pacientes assintomáticos sem história de cardiopatia isquêmica e sem TE/TCPE alterado geralmente não se beneficiam da realização da CPM. Os assintomáticos com TE alterado podem se beneficiar da CPM, principalmente se risco intermediário ou alto ( Tabela 14 ). 9 , 254

Tabela 14. – Critérios de indicação da cintilografia de perfusão do miocárdio para pacientes assintomáticos e/ou com exames cardiológicos prévios 9,254 .

| Assintomáticos – detecção de DAC/estratificação de risco | GR | NE | Escore |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baixo risco (critérios ATP III) | III | A | 1 |

| Risco intermediário (critérios ATP III) – ECG não interpretável | IIa | B | 5 |

| Risco intermediário (critérios ATP III) – ECG interpretável | IIb | C | 3 |

| Alto risco (critérios ATP III) | I | A | 7 |

| Alto risco e escore de cálcio (Agatston) entre 100 e 400 | IIa | B | 7 |

| Escore de cálcio (Agatston) > 400 | IIa | B | 7 |

| Escore de Duke de risco elevado (<-11) | I | A | 8 |

| Escore de Duke de risco intermediário (entre -11 e +5) | IIa | B | 7 |

| Escore de Duke de baixo risco (>+5) | III | B | 2 |

| GR: grau de recomendação; NE: nível de evidência; Agatston: escore que define a presença e quantidade de cálcio nas artérias coronárias, caracterizando aterosclerose; ATP III: painel de tratamento em adultos, do programa de detecção, avaliação e tratamento de colesterol elevado em adultos; DAC: doença arterial coronariana. | |||

Em pacientes assintomáticos após intervenção coronária percutânea (ICP) e/ou revascularização cirúrgica do miocárdio, a CPM apresenta relação custo-benefício favorável em seguimentos superiores a 2 e 5 anos, respectivamente. Tais pacientes, caso apresentem sintomas anginosos ou manifestações equivalentes, beneficiam-se da CPM a qualquer momento ( Tabela 15 ). 9 , 31 , 251 , 252 , 254

Tabela 15. – Critérios de indicação da cintilografia de perfusão do miocárdio após procedimentos de revascularização (CRM ou ICP) 9,31,251,252,254 .

| Revascularização percutânea ou cirúrgica prévia | GR | NE | Escore |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sintomáticos a qualquer momento | I | B | 8 |

| Assintomático, CRVM ≥5 anos | IIa | B | 7 |

| Assintomático, CRVM <5 anos | IIb | B | 5 |

| Assintomático, revascularização percutânea ≥2 anos | IIa | B | 6 |

| Assintomático, revascularização percutânea <2 anos | III | C | 3 |

| GR: grau de recomendação; NE: nível de evidência; ICP: intervenção coronária percutânea; CRVM: cirurgia de revascularização miocárdica. | |||

Pacientes com DAC estabelecida e piora dos sintomas (ou com manifestações equivalentes), podem se beneficiar do exame a qualquer momento, com o objetivo principal da quantificação da carga isquêmica (extensão e intensidade dos defeitos) e suporte à decisão terapêutica (GR-NE: I-C). 252

Nos quadros de dor torácica aguda com suspeita de SCA, ECG normal (sem alterações isquêmicas ou necrose) ou ECG não interpretável (BRE, WPW e ritmo de marca-passo) e marcadores de necrose miocárdica (MNM) normais, a CPM em repouso apresenta elevado valor preditivo negativo, permitindo a liberação do paciente da sala de emergência ( Tabela 16 ). 1 , 9 , 33 , 254 - 258

Tabela 16. – Critérios de indicação da cintilografia de perfusão do miocárdio em pacientes com dor torácica aguda ou pós-síndrome coronariana aguda 1,9,33,254-258 .

| Dor torácica aguda (imagem em repouso) | GR | NE | Escore |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCA possível – ECG normal ou ECG não interpretável*; escore TIMI de baixo risco; MNM limítrofes, minimamente e elevados ou normais | IIa | A | 8 |

| SCA possível – ECG normal ou ECG não interpretável*; escore TIMI de alto risco; MNM limítrofes, minimamente elevados ou normais | IIa | A | 7/8 |

| SCA possível – ECG normal ou ECG não interpretável*; MNM iniciais negativos. Dor torácica recente (até 2 horas) ou em evolução | IIa | B | 7 |

| Pós-SCA (infarto com ou sem supradesnível do segmento ST) | GR | NE | Escore |

| Paciente estável pós-IAM com supradesnível do segmento ST para avaliação de isquemia / viabilidade e cateterismo cardíaco não realizado | IIa | B | 8 |

| Paciente estável pós-IAM sem supradesnível do segmento ST para avaliação de isquemia / viabilidade e cateterismo cardíaco não realizado. | IIa | B | 9 |

| GR: grau de recomendação; NE: nível de evidência; BRE: bloqueio do ramo esquerdo; DCA: doença arterial coronariana; ECG: eletrocardiograma de 12 derivações; IAM: infarto agudo do miocárdio; MP: marca-passo; SCA: síndrome coronariana aguda. ECG normal: sem alterações isquêmicas ou de necrose. ECG não interpretável: BRE antigo, ritmo de marca-passo, síndrome de WPW e sobrecarga ventricular esquerda importante; MNM: marcadores de necrose miocárdica. | |||

A pesquisa de viabilidade miocárdica através da CPM auxilia a seleção de pacientes com disfunção ventricular esquerda acentuada, elegíveis para revascularização miocárdica ( Tabela 17 ). 1 , 9 , 31 , 128 , 258 , 259

Tabela 17. – Critérios de indicação da cintilografia de perfusão do miocárdio para avaliação de viabilidade miocárdica 1,9,31,128,258,259 .

| Avaliação de viabilidade miocárdica | GR | NE | Escore |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disfunção ventricular esquerda acentuada, elegível para revascularização | I | A | 9 |

| GR: grau de recomendação; NE: nível de evidência. | |||

As indicações de CPM referentes a investigação de insuficiência cardíaca, arritmias, síncope, pacientes com escore de cálcio elevado (≥400), diabéticos, insuficiência renal crônica ou com história familiar de cardiopatia isquêmica, avaliação de risco pré-operatório em cirurgia não cardíaca e cirurgia vascular estão contempladas na Atualização da Diretriz de Cardiologia Nuclear. 9 , 253

2.5.2. Indicações da Ecocardiografia sob Estresse

O ecocardiograma sob estresse (EcoE) é o método de imagem não invasivo utilizado para diagnóstico, estratificação de risco, prognóstico e avaliação da viabilidade miocárdica na doença arterial coronariana (DAC), valvopatias e cardiomiopatias. 260

Na investigação de isquemia, oferece boa acurácia em pacientes de moderado a alto risco, com leve predomínio da especificidade frente a outros métodos não invasivos de imagem, como a CPM. 260 - 262 Entretanto, o método não deve ser considerado como substituto do TE, e está indicado nos pacientes com limitações ou contraindicações à realização do TE. 262

As modalidades de estresse aplicáveis são: físico (em esteira, bicicleta ergométrica ou cicloergômetro de maca); farmacológico com dobutamina (sensibilizada com atropina) ou com vasodilatador (adenosina ou dipiridamol; uso mais raro). Tanto o estresse físico quanto o farmacológico com dobutamina apresentam desempenho diagnóstico similar em relação à isquemia. Entretanto, o estresse físico (GR-NE: I-A) permite melhor interpretação da repercussão funcional, avaliação da aptidão cardiorrespiratória e da disfunção ventricular, além de definição de prognóstico e terapêuticas nas cardiopatias isquêmicas, valvopatias ou cardiomiopatias ( Tabela 18 ). 8 , 260 , 263

Tabela 18. – Vantagens, desvantagens e contraindicações das diferentes modalidades de estresse 8,260,264 .

| Cicloergômetro de maca | Bicicleta ergométrica | Esteira | Dobutamina | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aumenta a demanda miocárdica de oxigênio | Sim | Sim | Sim | Sim |

| Avaliação durante o período de estresse | Sim | Sim | Não | Sim |

| Permite imagens no estresse máximo | Sim | Sim | Não* | Sim |

| Avaliação adequada da gravidade das DCV | Sim | Sim | Sim | Sim |

| Avaliação diagnóstica de isquemia | Sim | Sim | Sim | Sim |

| Aptidão cardiorrespiratória | Sim | Sim | Sim – melhor | Não |

| Repercussão funcional | Sim | Sim | Sim | Não |

| Risco de complicações | Muito baixo | Baixo | Baixo | Baixo |

| Definição de prognóstico | Sim | Sim | Sim | Limitada |

| Disponibilidade da modalidade de estresse | Moderada | Baixa | Alta | Alta |

| Contraindicações | 1) Síndrome coronariana aguda instável ou complicada** 2) Arritmias cardíacas graves (TV e BAVT)** 3) Hipertensão moderada/grave (PAS >180 mmHg)** 4) Alteração EcoB que possa tornar o estresse inseguro** 5) Contraindicações absolutas ao TE (Quadro 1) | Mesmas (1 a 4) e 5) Obstrução significativa de via de saída VE | ||

| DCV: doenças cardiovasculares; TV: taquicardia ventricular; BAVT: bloqueio atrioventricular total; PAS: pressão arterial sistólica de repouso; VE: ventrículo esquerdo. EcoB: ecocardiograma basal. *Aquisição de imagens feita imediatamente após o esforço, o mais rápido possível. **Contraindicações comuns ao estresse físico e dobutamina. | ||||

O EcoE pode ser recomendado para estratificação de risco de pacientes com síndrome coronariana aguda em unidades de dor torácica ( Tabela 19 ), e na investigação da DAC estável ( Tabela 20 ). As principais indicações do EcoE em outras DCV não isquêmicas são apresentadas na Tabela 21 .

Tabela 19. – Indicações do ecocardiograma sob estresse na síndrome coronariana aguda em unidade de dor torácica e internação hospitalar 8,260,261,265 .

| Indicação | GR | NE |

|---|---|---|

| Pacientes com angina instável de baixo risco controlada clinicamente* antes de decidir a estratégia invasiva | IIa | A |

| Para avaliar o significado funcional de obstrução coronariana moderada na angiografia, desde que o resultado interfira na conduta | IIa | C |

| Estratificação de risco após infarto do miocárdio não complicado | IIa | A |

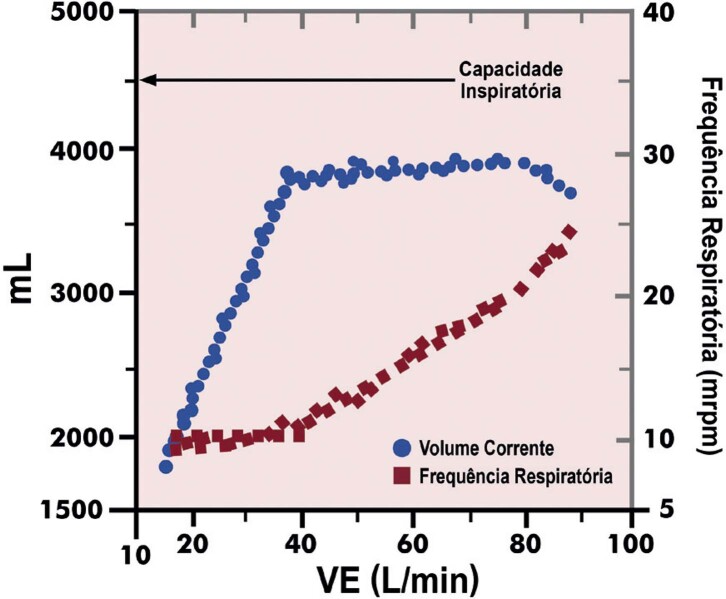

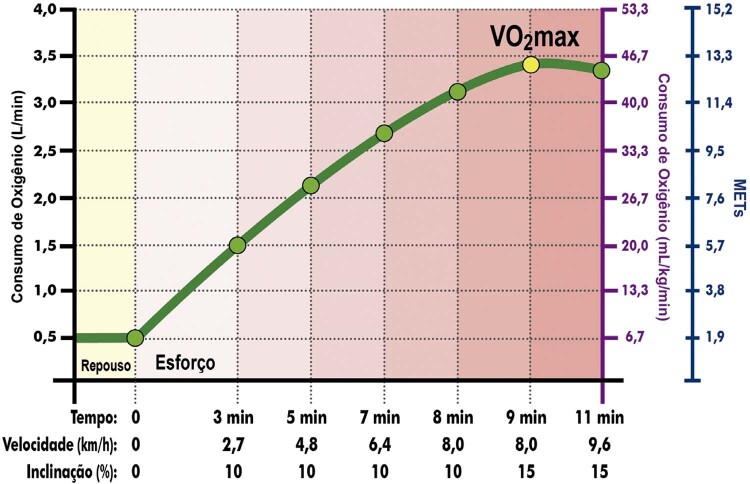

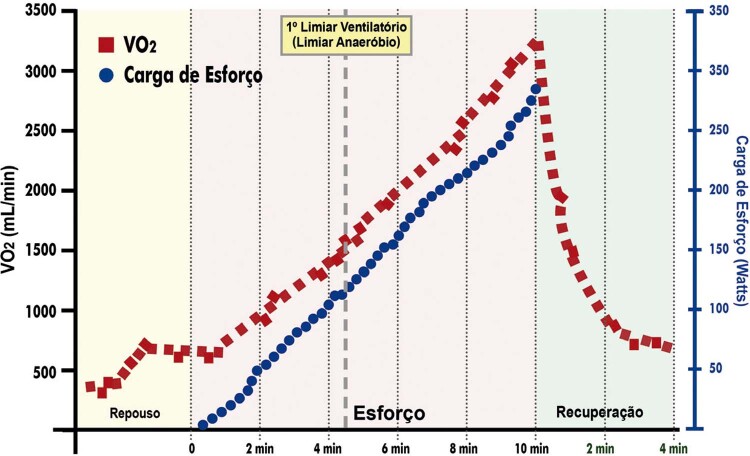

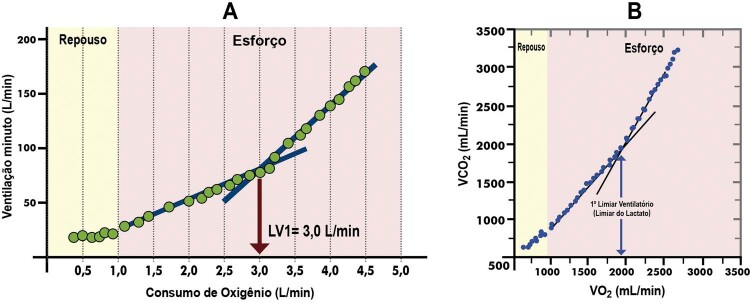

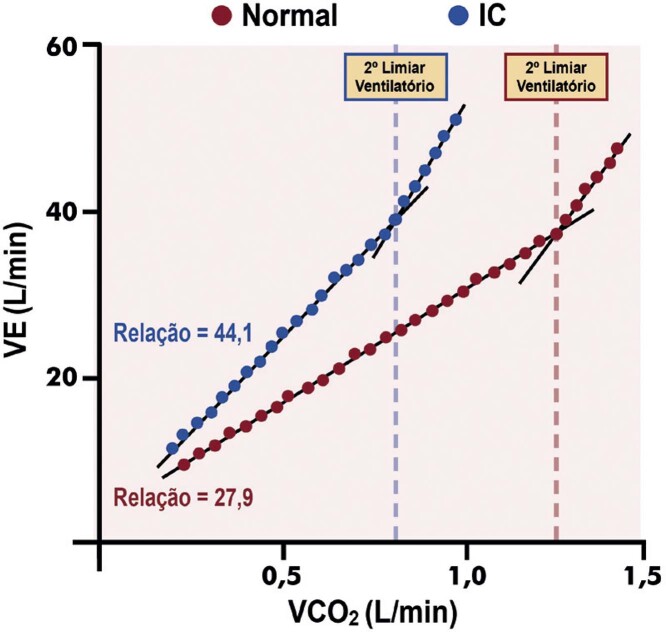

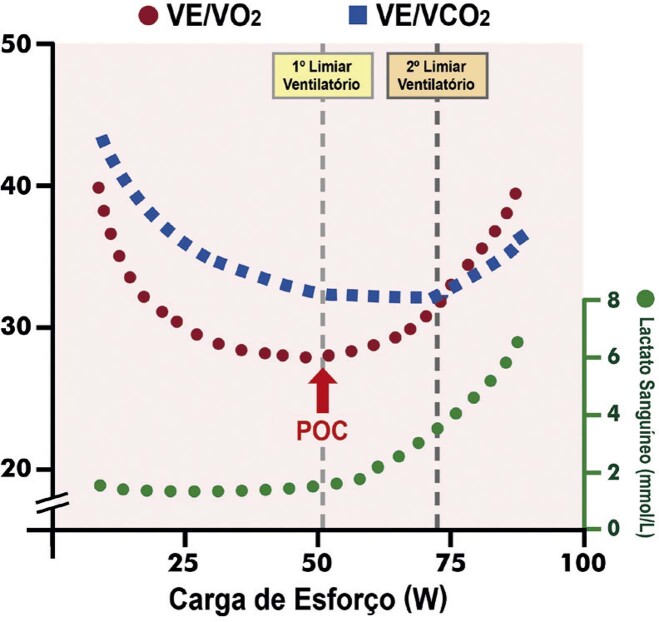

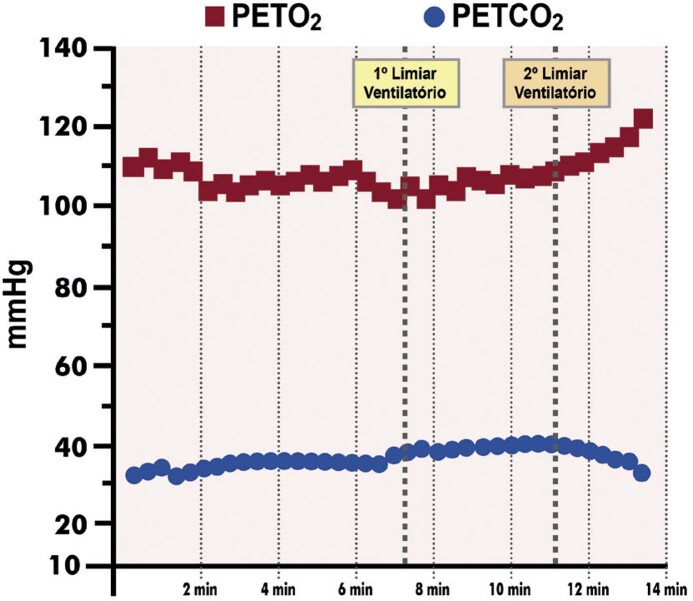

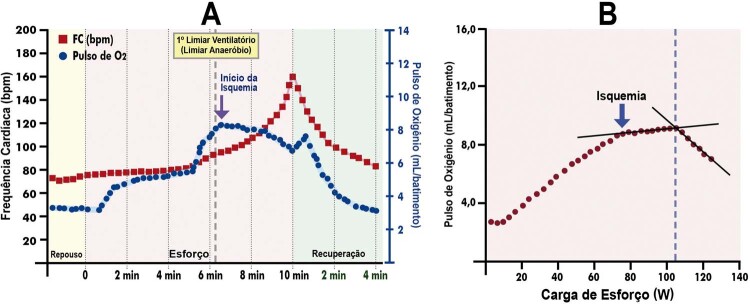

| Investigação de pacientes com suspeita de doença microvascular,** para estabelecer se há alteração segmentar simultânea à angina e alterações eletrocardiográficas | IIa | C |