Abstract

Ampullary carcinoma (AC) of the intestinal type represents a distinct variant within the broader category of ampullary neoplasms. The scarcity of pertinent cellular models has constrained investigations centered on this particular malignancy. This research effectively generated a cell line (CL) of intestinal-type AC (DPC-X3). This newly developed CL has been continuously cultured for 1 year and has demonstrated stable passaging exceeding 60 generations. Morphologically, DPC-X3 exhibited characteristic attributes of an epithelial tumor. The cell proliferation rate of DPC-X3 exhibited a doubling interval of 79 h. Short tandem repeat (STR) analysis validated the high consistency between DPC-X3 and the patient’s primary tumor. Characteristically, DPC-X3 displayed sub diploid karyotypes, primarily featuring 44, XY inv (9), -18, -20, -22, and + mar. Under suspension culture conditions, DPC-X3 could efficiently form organoids, and DPC-X3 cells inoculated subcutaneously into NXG mice could form transplanted tumors. Drug susceptibility assays demonstrated that DPC-X3 resisted paclitaxel, oxaliplatin, 5-fluorouracil(5-FU), and gemcitabine. Immunohistochemical (IHC) evaluation revealed affirmative reactivity for CK7 and CK20 within DPC-X3 cells, while CDX2 exhibited no detectable expression. E-cadherin and Vimentin demonstrated positive immunoreactivity, whereas CEA and CA19-9 displayed faint positivity. The Ki-67 proliferation index was determined to be approximately 40%. DPC-X3 presents a valuable experimental platform for elucidating the pathogenesis of intestinal-type AC and can serve as a driver for drug development efforts.

Keywords: Ampullary carcinoma, Cell line establishment, Xenografted tumor, Short tandem repeat analysis, Drug resistance

Introduction

Although rare, ampullary carcinoma (AC) has exhibited a steady rise in its occurrence rate in recent times. It originates from the intricate junction of the pancreatic duct, bile duct, and duodenum, and its precise oncogenesis and disease development are still not fully understood [1–3]. Initially classified by Kimura et al. into intestinal-type and pancreaticobiliary-type based on histological features, AC was later redefined by the World Health Organization in 2010. The updated pathological standards identified three distinct histological categories founded on morphological and IHC features: intestinal-type, pancreaticobiliary-type, and mixed-type [4–6].

Pancreaticoduodenectomy is the main treatment for ampullary cancer, with approximately 50% of cases having the possibility of surgical resection, followed by adjuvant treatment [7, 8]. Although the prognosis for intestinal-type AC is comparatively better than that for pancreaticobiliary and mixed types, the optimal value and regimen of adjuvant chemotherapy for intestinal-type AC remain uncertain [4, 9].

Therefore, understanding the pathogenesis of intestinal-type ampullary cancer is crucial to unveil new drugs and treatment methodologies for ampullary cancer, ultimately enhancing patient survival prospects.

Currently, only nine existing cell lines (CLs) globally are available for in vitro research on AC, with merely one CL representing intestinal-type AC, namely SNU869 [10, 11]. Recognizing the diversity in tumor etiology, tumor heterogeneity, and race-related genetic variations [12–15], establishing a diverse array of ampullary cancer CLs is crucial for advancing fundamental studies and pharmaceutical innovations in this field.

This research effectively developed a stable CL designated DPC-X3, representing intestinal-type ampullary cancer. This CL originated from tumor tissue surgically extracted from patients with ampullary cancer, providing a valuable experimental model for studying intestinal-type ampullary malignancies.

Methodologies and materials

Tissue source

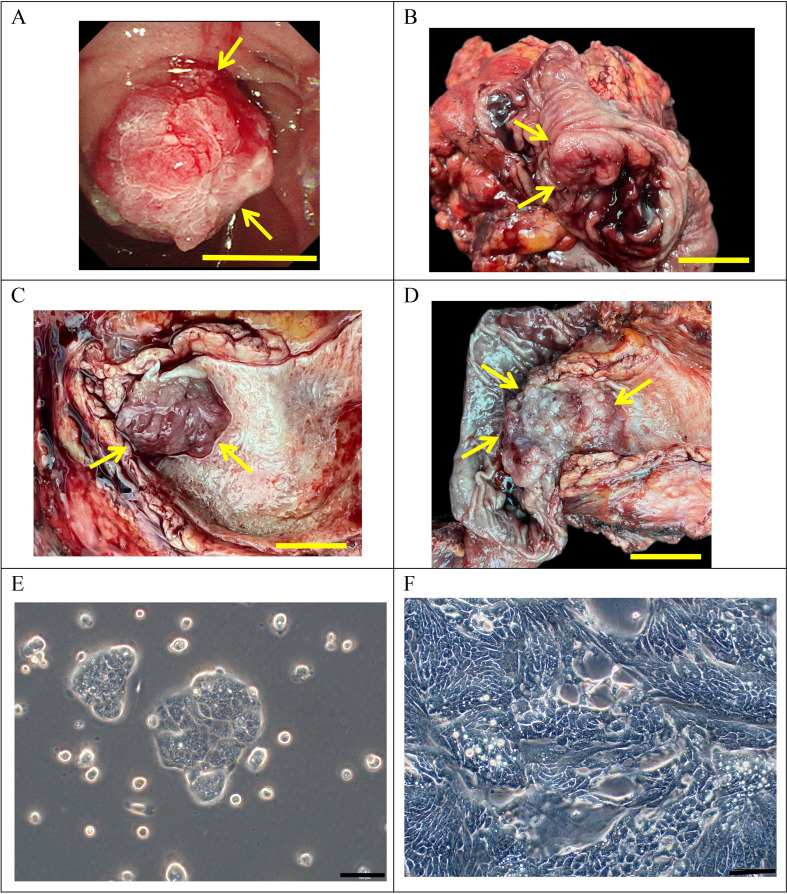

The subject, a 72-year-old man, reported no prior tobacco use, alcohol, or hepatitis B infection. His CEA level was 1.4 ng/mL (normal range: 0-5.2 ng/mL), AFP level was 4.6 U/mL (normal range: 0-5.8 U/mL), and CA 19 − 9 level was 38.3 U/mL (normal range: 0–35 U/mL; Table 1). Duodenoscopy examination indicated the presence of a tumor in the ampullary region (Fig. 1A). He did not undergo radiotherapy or chemotherapy before undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy at Lanzhou University Second Hospital on August 29, 2022. Surgical gross views of the postoperative specimens revealed an ampulla with a 2 × 1.5 cm new organism (Fig. 1B-D). Samples were collected from the main site of infection for initial and subsequent cultivation examination.

Table 1.

Clinical data of the included patient

| Cell line | Patient age/ethicity | Gender | Histopathology/differentiation | Tumor size(cm) | Prior therapy | Culture date | Serum | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFP IU/ml (0-5.8) |

CEA ng/ml (0-5.2) |

CA19-9 U/ml (0–35) |

|||||||

| DPC-X3 | 72/Asian | Male | Moderately | 2 × 1.5 | None | 2022−8−29 | 4.6 | 1.4 | 38.3 |

Fig. 1.

Clinical data and cell morphology. (A) Preoperative duodenoscopy findings of the patient depicting a tumor in the ampullary region (indicated by the arrow) (scale bar = 1 cm). (B–D) Gross examination of the postoperative specimen revealing a mass in the ampullary region (indicated by the arrow) (scale bar = 1 cm). (E–F) Microscopic examination showing DPC-X3 cell morphology under a light microscope (scale bar = 100 μm)

This research was sanctioned by the Medical Ethics Committee of Lanzhou University Second Hospital (2023 A-381), with the participant granting informed agreement to participate.

NXG mouse

The study utilized female NXG mice, 5–6 weeks of age, weighing 11–17 g. These rodents were obtained from Changzhou Cavens Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd. (Changzhou, China) and maintained in the specific pathogen-free facility at Lanzhou University’s Animal Experimental Center. The experimental design aimed to reduce animal distress. Prior to experimentation, mice were acclimated to laboratory settings (23℃, 12-h/12-h light/dark cycle, 50% humidity, unrestricted food, and water access) for 2 weeks. The animals were provided sterilized rodent feed without restriction, and their bedding, nourishment, and hydration were refreshed bi-daily. All protocols adhered to organizational and governmental standards for maintaining and utilizing laboratory fauna. The well-being and conduct of the subjects were monitored daily over four weeks. Mice were humanely euthanized when the xenograft tumor’s maximum diameter approached 1.5 cm or following 1 month of tumor development. Euthanasia was performed using an excessive dose of barbiturate (intravenous delivery, 150 mg/kg pentobarbital sodium), verified by the absence of heartbeat, respiration, and pupillary response.

The Medical Animal Experiment Ethics Committee of Lanzhou University Second Hospital provided ethical clearance for the animal research (D2023-318). All experiments complied with the ARRIVE guidelines and the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of China.

The techniques outlined in the following segments were comparable or equivalent to those utilized in earlier investigations [10, 16].

Primary culture, cell purification, and CL establishment

The tumor specimen was immersed in aseptic phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Gibco, Cat#10010023) and washed 3–5 times. After cutting it to the maximum extent possible, type II collagenase (Gibco, Cat#17101015) and Dispase II (Invitrogen, Cat#17105041) were added. The tissue was digested on a shaking table at 37 °C. The liquid above was procured after the limited enzymatic breakdown of the tissue samples. This fluid was strained using a 100-mesh sieve and centrifuged at 300 ×g for 3 min. The upper liquid was removed, and the residual material was reconstituted in PBS. After centrifugation at 300 ×g for 3 min, the sediment was mixed with full growth medium (RPMI-1640(BI, Cat#c3010-0500) + 10% fetal bovine serum [FBS](BI, Cat#04-002-1 A) + 1% penicillin-streptomycin (BI, Cat#03-031-1B)). This mixture was evenly seeded onto a six-well plate (NEST, Cat#703001), and the medium was replenished after 48 h. A sterile 1-mL pipette (KIRGEN) was used to scrape off fibroblasts repeatedly under direct microscope observation to remove fibroblasts from the primary culture process. Cell proliferation was routinely monitored using an optical microscope. From the third passage forward, cells underwent subculturing at a 1:2 proportion and were kept in a serum-free quick cell cryopreservation medium (Mei5 Biotechnology, Cat#MF699-01).

Analysis of DNA short tandem repeat sequences

DPC-X3 cells in the exponential growth stage (EGS) (P10) were collected after trypsin digestion. These cells and the original neoplastic tissue underwent short tandem repeat (STR) profiling performed by Suzhou Genetic Testing Biotechnology Company to evaluate the relationship between the cultured cells and the source tumor specimen.

Cell growth curve

DPC-X3 cells in the EGS (P25) were adjusted to a cell density of 1 × 104/mL following trypsinization. Subsequently, 0.1 mL of the cell suspension was inoculated per well onto a 96-well plate. After cell attachment, CCK-8 reagent (Dojindo, Cat#ck04) was introduced for 4 consecutive days, with a reaction period of 2 h for each instance. The absorbance value at a wavelength of 450 nm was ascertained utilizing an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay reader, and a calibration curve was constructed. The cell population doubling periods were calculated for multiple time intervals employing the “cell calculator++”tool [V. Roth MD, Doubling Time Calculator (2006), https://doubling-time.com/compute_more.php].

Karyotyping

DPC-X3 cells in the EGS (P30) were exposed to 0.25-µg/mL colchicine for 6 h and throughout the night at 37 °C. Cells in metaphase were harvested, fixed using a methanol-acetic acid solution (3:1), stained utilizing Giemsa staining solution after trypsin digestion, and enumerated under microscopic examination. For karyotype evaluation, well-separated and adequately stained mitotic figures were chosen.

Organoid culture from DPC-X3 cells

DPC-X3 cells (P33) underwent enzymatic digestion, centrifugation, and two PBS rinses in the EGS. The cells were then suspended in a growth medium (RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin, BI). The cell suspension (1,000 cells per well) was plated onto a non-adherent six-well plate (Corning, Cat#3471), with 2 mL of culture medium added for expansion. The development and quantity of organoids were routinely examined using a phase-contrast microscope.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

Cells in the logarithmic growth phase, harvested after 30 passages, were employed for SEM analysis. The cell-containing slides underwent washing with physiological saline, followed by fixation using a 4% glutaraldehyde solution (SPI-CHEM, USA). Subsequently, the samples were rinsed three times with phosphate buffer. Dehydration was conducted step-by-step using a gradient of tert-butanol (50%, 70%, 80%, 90%, and 100%) for 5 min each. The dried sample was placed into the JEOL JFD-320 freeze-drying apparatus, and upon equilibrating to ambient temperature, a conductive coating was affixed to the specimen mount utilizing a JEOL JFCC-160 ion sputtering device. The examinations were documented and micrographs were obtained employing a HITACHI Regulus 8100 scanning electron microscope.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

DPC-X3 cells (P30) in the EGS were subjected to enzymatic digestion, centrifugal separation, and fixation utilizing a suitable fixative for TEM analysis. The cellular samples were maintained and shipped at 4℃ before being processed for ultrathin sectioning and staining at Wuhan Servicebio Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). The prepared specimens were subsequently visualized utilizing a transmission electron microscope to examine intracellular components.

Drug sensitivity test

Utilizing logarithmically growing DPC-X3 cells at passage 35 (P35), a single-cell suspension was prepared following trypsin digestion. Subsequently, 10,000 cells per well were inoculated and seeded into a 96-well plate. Upon cell adherence, the experimental group received varying concentrations of antitumor drugs: gemcitabine (600µmol/L, 150µmol/L, 30µmol/L, 6µmol/L, 1.5µmol/L, 0.3µmol/L, 0.06µmol/L, 0.015µmol/L, 0.003µmol/L, 0.0006µmol/L. plasma peak concentration: 19.01 µmol/L [17]), paclitaxel (50µmol/L, 25µmol/L, 12.5µmol/L, 2.5µmol/L, 0.5µmol/L, 0.1µmol/L, 0.025µmol/L, 0.005µmol/L, 0.001µmol/L. plasma peak concentration: 16.2 µmol/L [18]), oxaliplatin (400µmol/L, 200µmol/L, 100µmol/L, 40µmol/L, 20µmol/L, 10µmol/L, 5µmol/L, 2.5µmol/L, 1.25µmol/L, 0.625µmol/L, 0.3125µmol/L, 0.15625µmol/L. plasma peak concentration: 11.33 µmol/L [19]), and 5-fluorouracil [5-FU] (3840µmol/L, 960µmol/L, 240µmol/L, 60µmol/L, 15µmol/L, 3µmol/L, 0.6µmol/L, 0.15µmol/L, 0.03µmol/L, 0.006µmol/L. plasma peak concentration: 76.92 µmol/L [20]), while the control group received the corresponding drug solution. Following 72 h of drug treatment, the complete growth medium was substituted with 100 µL of a serum-free medium comprising 10% (v/v) CCK-8. Following a 2-hour incubation, the OD value was measured at 450 nm.

Transplantation tumor formation experiment

Employing cells in the EGS at passage 33 (P33), the cellular concentration was regulated to 1 × 107/mL following trypsin treatment and thoroughly homogenized. A pair of NXG mice were administered an inoculation of these cells (0.1 mL per animal) on the right scapular region and dorsal area. On the subsequent day, neoplasm development in the athymic rodents was monitored and documented. After 28 days, the animals were humanely sacrificed and examined to assess the progression of the xenografted tumor.

IHC staining

Cells from the 42nd passage were enzymatically dissociated and plated on sanitized microscope slides for cultivation. Following a 48-hour incubation period, the adherent cells underwent a washing process with phosphate-buffered saline, immobilized using 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 15 min, allowed to dry in ambient air, and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 20 min. Sections of xenograft tumors and original neoplastic tissues were embedded in paraffin and subjected to overnight heating at 60 ℃.

The tissue samples underwent dewaxing, gradient alcohol hydration, and antigen retrieval utilizing the Autostainer Link 48 device from Dako. Afterwards, 3% hydrogen peroxide solution was added, followed by incubation at 37 ℃ for 15 min to inhibit peroxidase activity. Then, 100 µL of normal goat serum was dispensed dropwise, succeeded by a 15-minute incubation at 37 ℃ for blocking purposes.

Primary antibody (Fuzhou Maixin ready-to-use antibodies [CK7, Cat#MAB-0828; CK20, Cat#MAB-0834; CDX2, Cat#MAB-1056; Ki-67, Cat#MAB-0672; E-cadherin, Cat#MAB-0738; Vimentin, Cat#MAB-0735; CEA, Cat#MAB-0852; CA19-9, Cat#MAB-0778]) was introduced to the cells and kept at 37 ℃ for 1 h. The DAB staining kit (Dako, Cat#K3468) was utilized for chromogenic development, succeeded by washing the cells under flowing water for 5 min. After counterstaining with hematoxylin, the samples underwent dehydration and xylene clearing, and neutral resin was employed to seal the coverslip. Subsequently, the slides were examined under a microscope.

Whole-genome resequencing (WGS) of DPC-X3 cells

Sequencing and data analysis were conducted at OE Biotech (Shanghai OE Biotech Co., Ltd). In short, genomic DNA was extracted from the DPC-X3 sample, and after passing the electrophoresis detection, the library was constructed. After the library construction was qualified, used a sequencer for dual end sequencing. After obtaining raw sequencing data from the sequencing machine, bioinformatics analysis was performed.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS 26.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Student’s t-tests and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) were used for two-group and multi-group comparisons, respectively. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Establishment of DPC-X3 CL

A stable and passaged ampulla cancer CL, DPC-X3, was successfully established by isolating primary cells from surgical tumor tissue and subsequent culturing. Under an optical microscope, DPC-X3 exhibited typical epithelial cell-like morphology with cell island–like adherent growth. These polygonal cells possess a large nucleus and prominent nucleoli (Fig. 1E and F). The cellular structure maintained stability even following multiple cycles of cryopreservation and revival.

Analysis of DNA short tandem repeat sequences

The DNA typing outcomes verified that the two provided specimens stem from a single source, yielding a likelihood ratio (LR) of 2.4864 × 1026 (Table 2). This substantial LR strongly supports the derivation of the DPC-X3 CL, which originated from the identical subject as the primary neoplasm sample. Moreover, the genetic signature of DPC-X3 showed no correspondence with any current records in the ExPASy STR repository, validating its classification as a previously undescribed human AC CL.

Table 2.

Short tandem repeat profile of DPC-X3 and tumor tissue

| Loci | DPC-X3 | Tumor tissue | Matching probability | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amelogenin | X | Y | X | Y | / |

| D3S1358 | 15 | 17 | 15 | 17 | 0.1540 |

| D5S818 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 11 | 0.1287 |

| D2S1338 | 18 | 22 | 18 | 22 | 0.0202 |

| TPOX | 8 | 8 | 0.2862 | ||

| CSF1PO | 10 | 12 | 10 | 12 | 0.1415 |

| Penta D | 11 | 13 | 11 | 13 | 0.0424 |

| TH01 | 6 | 10 | 6 | 10 | 0.0086 |

| vWA | 16 | 18 | 16 | 18 | 0.0486 |

| D7S820 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 11 | 0.1350 |

| D21S11 | 30 | 31 | 30 | / | |

| Penta E | 11 | 14 | 11 | 14 | 0.0306 |

| D10S1248 | 15 | 15 | 0.0414 | ||

| D8S1179 | 15 | 15 | 0.0256 | ||

| D1S1656 | 13 | 15 | 13 | 15 | 0.0003 |

| D18S51 | 14 | 13 | 14 | / | |

| D12S391 | 18 | 20 | 18 | 20 | 0.0733 |

| D6S1043 | 14 | 14 | 19 | / | |

| D19S433 | 13 | 15 | 13 | 15 | 0.0244 |

| D16S539 | 9 | 12 | 9 | 12 | 0.1283 |

| D13S317 | 8 | 8 | 0.0484 | ||

| FGA | 22 | 25.2 | 22 | 25.2 | 0.0010 |

| LR | 2.4864 × 1026 | ||||

Cell growth curve

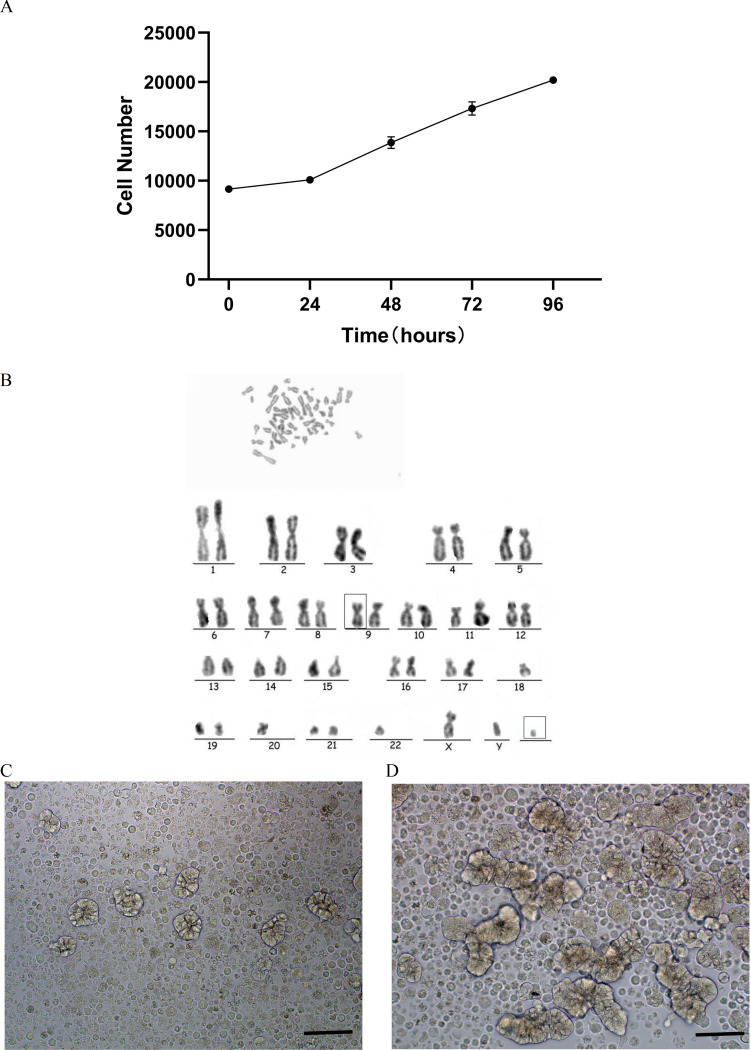

The proliferation rate of DPC-X3 cells was moderate, exhibiting steady growth in RPMI-1640 medium comprising 10% FBS. Utilizing the CCK-8 technique, the population doubling period of DPC-X3 cells was 79 h (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

DPC-X3 cell characteristics. (A) Growth curve illustrating the doubling time of the DPC-X3 cell population was 79 h. (B) Karyotype analysis revealed that 80% of DPC-X3 cells were subdiploid and 20% were subtriploid, with representative karyotype shown as 44, XY inv (9), -18, -20, -22, +mar. (C) Morphology of DPC-X3 cell organoids after 4 days under suspension culture condition (scale bar = 50 μm). (D) Morphology of DPC-X3 cell organoids after 10 days under suspension culture condition (scale bar = 50 μm)

Karyotyping

Karyotype analysis indicated that 80% of DPC-X3 cells were subdiploid and 20% were subtriploid, displaying chromosome count and morphology variations. Representative karyotypes were 44, XY inv (9), -18, -20, -22, +mar (Fig. 2B).

Organoid culture

Upon inoculating DPC-X3 cells on an ultra-low attachment culture dish, robust cell proliferation was observed in a complete culture medium, forming glandular-like tumor organoids. Over time, these organoids grew larger, exhibiting increased complexity in glandular structures, and developed longer branching patterns (Fig. 2C and D).

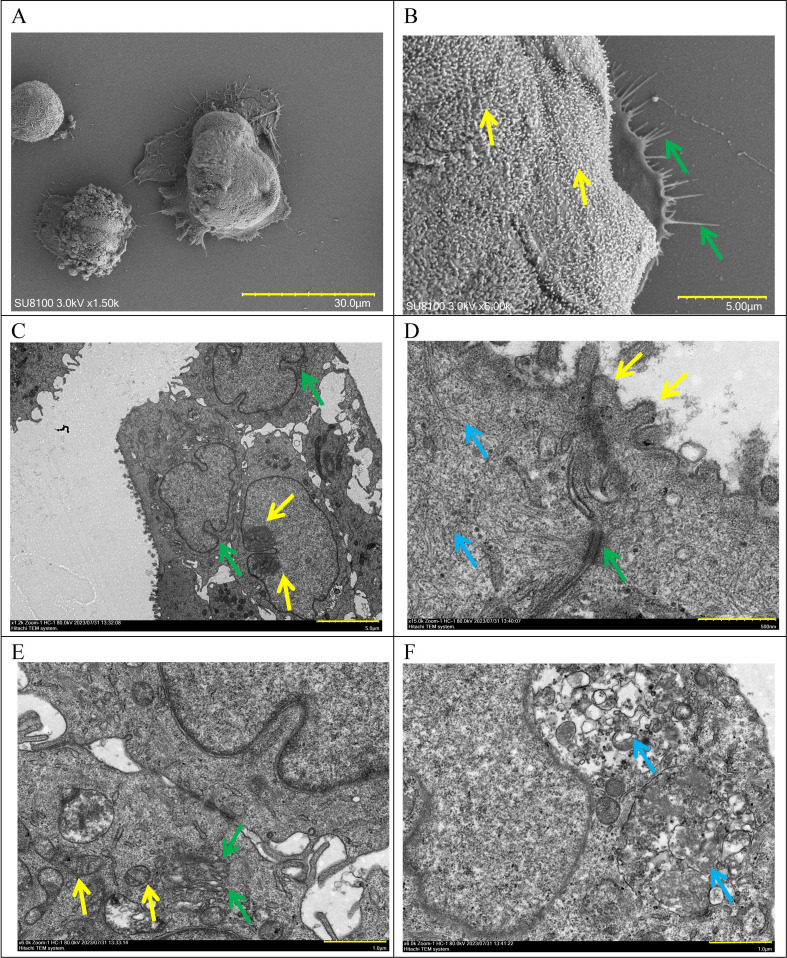

SEM and TEM

Examination through SEM unveiled DPC-X3 cells exhibiting a spheroidal form, characterized by copious microvilli adorning the cellular exterior (indicated by yellow arrow) and a comparatively consistent morphological appearance, displaying thread-like pseudopodia (denoted by green arrow; Fig. 3A and B). TEM showcased enlarged nuclei in DPC-X3, increased nucleoli gathering toward the edges (yellow arrow), nuclear membrane shrinkage (green arrow), and reduced cytoplasm.

Fig. 3.

Ultrastructural examination of DPC-X3 cells. (A-B) DPC-X3 cells are spherical and have a relatively uniform morphology, with abundant microvilli on the cell surface (yellow arrow) and filamentous pseudopodia visible (green arrow) (A, scale bar = 30 μm; B, scale bar = 5 μm). (C) The nucleus of DPC-X3 has enlarged, the number of nucleoli has increased, the edges appear to be gathered (yellow arrow), the nuclear membrane has shrunk (green arrow), and the cytoplasm content has decreased (scale bar = 5 μm). (D) Microvilli can be seen on the cell surface (yellow arrow), with a desmosome structure (green arrow) and several tension fibrils inside the cell (blue arrow) (scale bar = 500 nm). (E) The number of intracellular organelles has decreased, mitochondria have swollen and vacuolized, and the number of cristae decreases (yellow arrow). A certain amount of Golgi apparatus (green arrow) appears in the cell (scale bar = 1 μm). (F) Lysosomes (blue arrow)rich in zymogen particles can be seen (scale bar = 1 μm)

Microvilli could be observed on the cell surface (yellow arrow), and a desmosome structure (green arrow) and numerous tension fibrils (blue arrow) were observed inside the cell. The number of intracellular organelles decreased, showing swollen mitochondria with reduced cristae (yellow arrow). Golgi apparatus (green arrow) and zymogen particle-rich lysosomes (blue arrow) were observed (Fig. 3C-F).

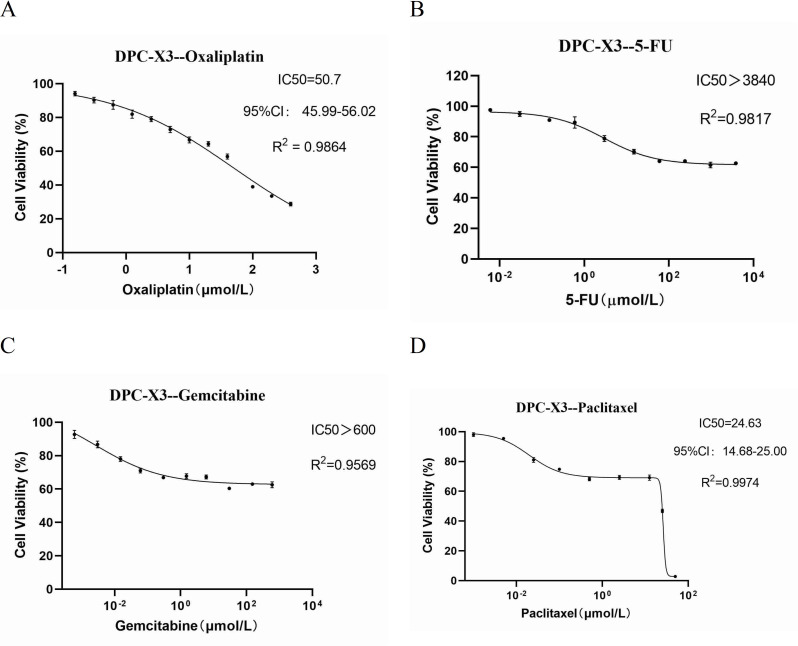

Drug sensitivity test

Chemotherapy drugs such as gemcitabine, paclitaxel, 5-FU, and oxaliplatin are frequently employed in treating gastrointestinal malignancies. The drug response assay demonstrated DPC-X3’s resistance to oxaliplatin (IC50 = 50.7 µmol/L); it exhibited high resistance to fluorouracil (IC50 > 3840 µmol/L) and gemcitabine (IC50 > 600 µmol/L), along with moderate resistance to paclitaxel (IC50 = 24.63 µmol/L; Fig. 4A-D).

Fig. 4.

Assessment of anticancer drug sensitivity in DPC-X3 cells. DPC-X3 cells demonstrated resistance to oxaliplatin (A), fluorouracil (B), gemcitabine (C), and paclitaxel (D)

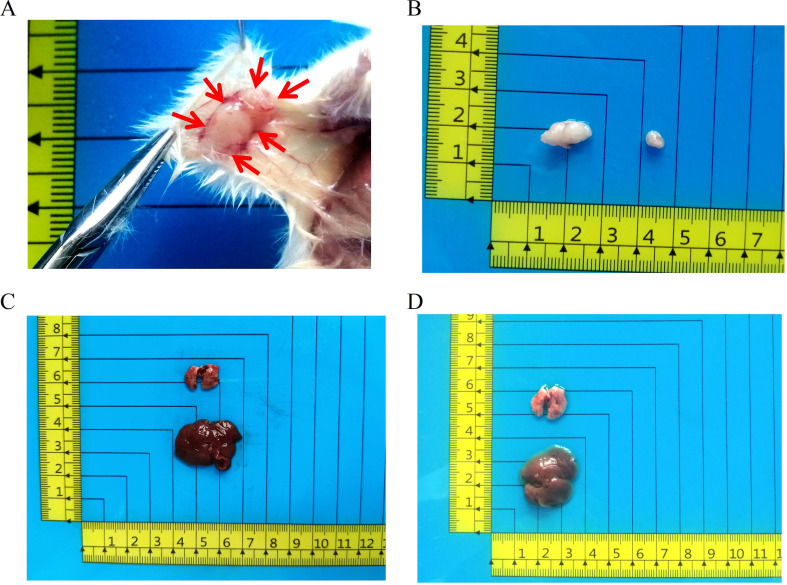

Transplantation tumor formation experiment

To validate the capacity of DPC-X3 for generating transplanted tumors in vivo, 1 × 106 DPC-X3 cells were subcutaneously inoculated into 2 NXG mice. The results indicated that DPC-X3 could form transplanted tumors in nude mice 4 weeks after subcutaneous inoculation, exhibiting a 100% tumor formation rate, the tumor volume was 161.5 ± 111.5 mm3 (Fig. 5A and B). Examination of the dissected mice revealed no metastatic sites in either the liver or lungs (Fig. 5C and D).

Fig. 5.

In vivo studies on xenograft tumor formation by DPC-X3 cells. (A-B) Subcutaneous transplantation of DPC-X3 cells in NXG mice resulted in notable tumor formation (red arrow), the tumor formation rate was 100%, and the tumor volume was 161.5 ± 111.5 mm3. (C-D) No metastatic lesions were observed in the liver and lung tissues of NXG mice 4 weeks after transplantation

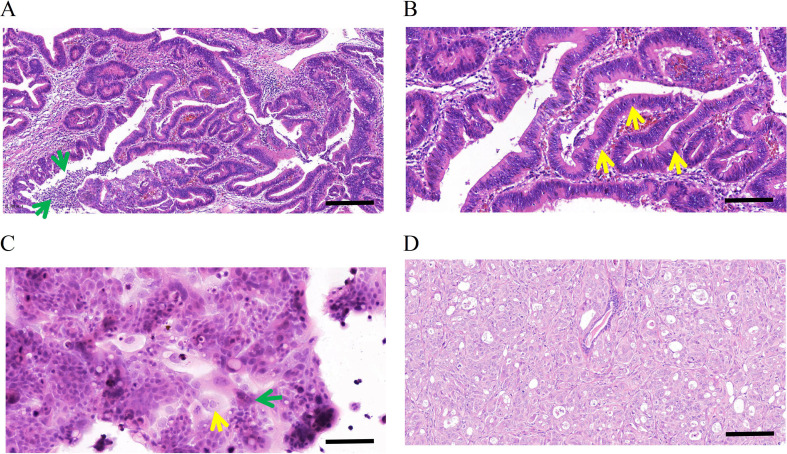

H&E and immunohistochemical staining

The patient’s primary tumor was classified as moderately differentiated upon postoperative pathological examination. The neoplastic cells exhibited an atypical glandular tubular arrangement, characterized by expansive tubules bordered by elongated columnar epithelium with stretched, multilayered, deeply stained nuclei (yellow arrow). Intraluminal necrotic material and acute inflammatory infiltrates (green arrow) were also observed, aligning with the distinctive architectural features of intestinal-type AC (Fig. 6A and B).

Fig. 6.

Hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining of the primary tumor, DPC-X3 cells, and xenograft tumor. The primary tumor was moderately differentiated. The tumor cells are arranged in an irregular glandular tubular pattern, large tubules lined by tall columnar cells with elongated, pseudostratified, hyperchromatic nuclei (yellow arrow). Luminal necrotic debris and acute inflammatory cells (green arrow) are also present. Typical structural characteristics are consistent with intestinal ampullary carcinoma (A, scale bar = 100 μm; B, scale bar = 50 μm). H&E staining showed that the morphology of DPC-X3 cells was relatively uniform, mainly polygonal, with an enlarged nucleus and evident nucleoli. The number of nucleoli increased, and the cytoplasm was less. A small number of multinucleated (yellow arrow) and megakaryocytes (green arrow)were visible (C, scale bar = 50 μm). H&E staining of the transplanted tumor shows irregular glandular structures formed by the cells, and its histological morphology was similar to that of the primary tumor (D). (scale bar = 50 μm)

H&E staining showed relatively uniform polygonal-shaped DPC-X3 cells, exhibiting enlarged nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and diminished cytoplasm. The sample displayed certain multinucleated cells (yellow arrow) and megakaryocytes (green arrow), presenting typical malignant tumor cell characteristics (Fig. 6C).

H&E examination of the grafted tumor exhibited atypical gland-like formations resembling those observed in the original malignancy (Fig. 6D).

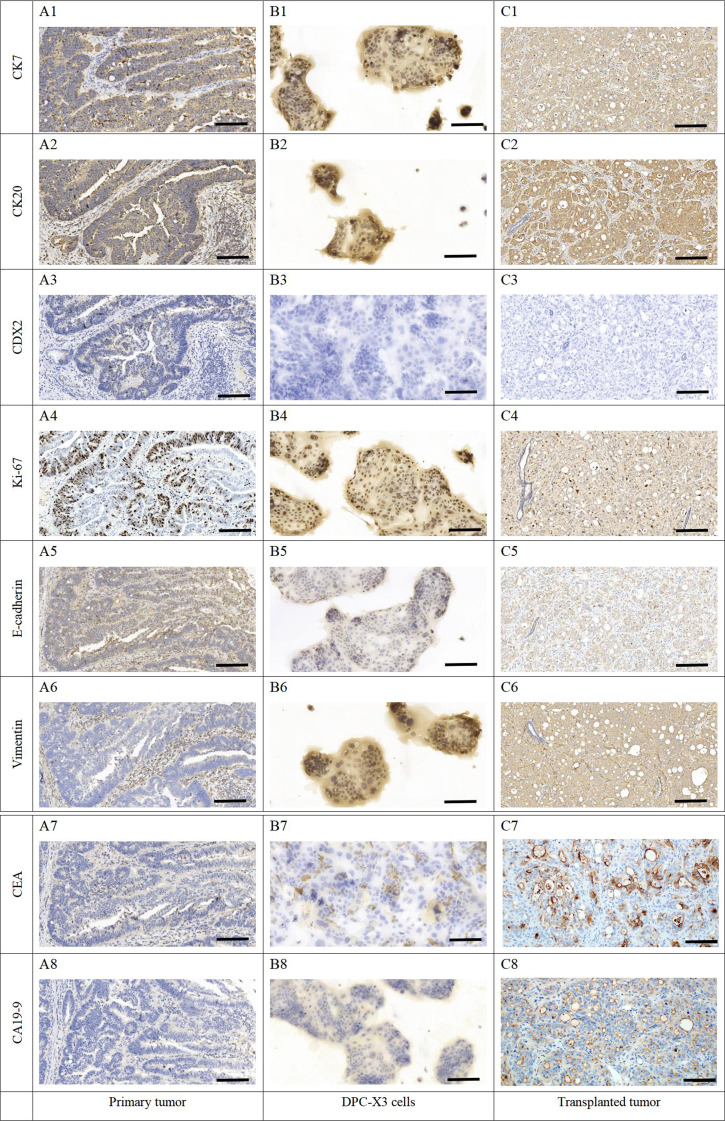

IHC displayed affirmative staining for CK7 (Fig. 7A1-C1) and CK20 (Fig. 7A2-C2) in primary tumors, DPC-X3 cells, and transplanted tumors, while CDX2 (Fig. 7A3-C3) expression was negative, indicating a common origin. The Ki-67 (Fig. 7A4-C4) proportion at 40% aligned with rapid tumor cell proliferation. Low E-cadherin (Fig. 7A5-C5) expression and positive Vimentin (Fig. 7A6-C6) expression indicated strong epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) characteristics in DPC-X3. Additionally, CEA (Fig. 7A7-C7) showed focal expression, while CA19-9 exhibited weak positivity (Fig. 7A8-C8).

Fig. 7.

Immunohistochemical staining of primary tumor, DPC-X3 cells, and xenograft tumor. (A1), (B1), and (C1) CK7-positive staining of primary tumor (A1), DPC-X3 cells (B1), and xenograft tumor (C1). (A2), (B2), and (C2) CK20-positive staining of primary tumor (A2), DPC-X3 cells (B2), and xenograft tumor (C2). (A3), (B3), and (C3) CDX2-negative staining of primary tumor (A3), DPC-X3 cells (B3), and xenograft tumor (C3). (A4), (B4), and (C4) Quantitative analysis showed a 40% positive rate of Ki67 in primary tumor (A4), DPC-X3 cells (B4), and xenograft tumor (C4). (A5), (B5), and (C5) Positive expression of E-cadherin was observed in primary tumor (A5), DPC-X3 cells (B5), and xenograft tumor (C5). (A6), (B6), and (C6) Positive expression of Vimentin was observed in primary tumor (A6), DPC-X3 cells (B6), and xenograft tumor (C6). (A7), (B7), and (C7) CEA was focally positive expressed in primary tumor (A7), DPC-X3 cells (B7), and xenograft tumor (C7). (A8), (B8), and (C8) CA19-9 was weakly expressed in primary tumor (A8), DPC-X3 cells (B8), and xenograft tumor (C8). (scale bar = 50 μm)

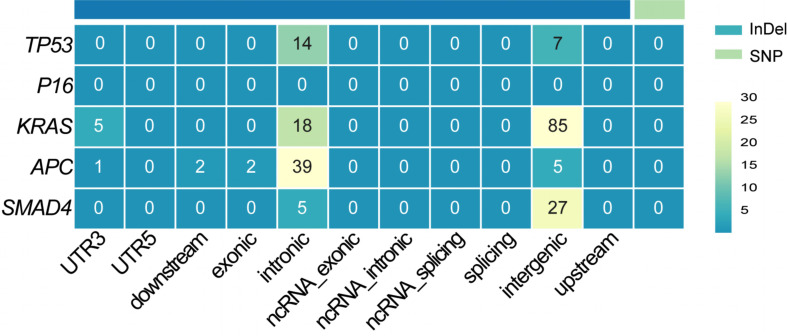

Mutation analysis of key driver genes

Whole-genome resequencing was conducted to identify mutations in TP53, P16, KRAS, APC, and SMAD4 in DPC-X3 cells. The results are presented in Fig. 8. No single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were detected in these genes. However, TP53 harbored 21 insertions and deletions (InDels), with 14 mutations located in intronic regions and 7 in intergenic regions. No mutations were identified in the P16 gene. In KRAS, 108 InDels were observed, including 5 within the 3’ untranslated region (UTR), 18 in intronic regions, and 85 in intergenic regions. APC exhibited 49 InDels, of which 1 was in the 3’UTR, 2 within 2 kb downstream of the transcription start site, 2 within an exonic region, 39 in intronic regions, and 5 in intergenic regions. SMAD4 harbored 32 InDels, with 5 in intronic regions, and 27 in intergenic regions.

Fig. 8.

Distribution of InDel and SNP mutations. InDel refers to insertion or deletion mutations. SNP stands for single nucleotide polymorphism. Exonic denotes mutations occurring within the coding regions of the coding sequence (CDS). Intronic refers to mutations located in the intronic regions of genes. Intergenic pertains to mutations found in the spacer regions between genes. UTR3 and UTR5 represent mutations within the 3’ and 5’ untranslated regions (UTRs) of the gene, respectively. Downstream indicates mutations occurring within 2 kb downstream of the transcription start site. Upstream refers to mutations located within 2 kb upstream of the transcription start site

Discussion

Intestinal-type ampullary cancer typically manifests with a non-invasive duodenal adenoma component. Its subtype shares similarities with colorectal cancer, displaying central necrosis, cribriform, or tubular glands [21, 22]. Intestinal-type ampullary cancer exhibits a more limited invasive component and less common perineural and lymphovascular infiltration, contributing to a comparatively better prognosis than that of pancreaticobiliary-type AC [23, 24].

The scarcity of ampullary cancer CLs severely limits understanding its pathogenesis and drug development. Determining the optimal treatment regimen, particularly for supplementary treatment and drug-based interventions in progressed instances, is challenging. There is an urgent need to comprehend the mechanisms driving ampullary cancer occurrence and progression to explore effective treatments, ultimately prolonging patient survival [8, 25].

AC classification predominantly relies on morphological assessment through H&E staining, supplemented by IHC staining results of related proteins. When discrepancies arise between morphological evaluation and IHC examination, priority should be given to the former [3]. The primary tumor of DPC-X3 has a tissue structure that conforms to the characteristics of typical intestinal-type AC, and IHC results exhibited positive CK7 and CK20 expression in DPC-X3 cells, all these signifying DPC-X3 as an intestinal-type AC CL. This CL offers a platform for basic research and drug development on ampullary cancer.

Tumor cell resistance significantly contributes to treatment failures, posing a major challenge in cancer therapy. Hence, investigating the causes of tumor cell resistance and strategies to enhance their responsiveness to chemotherapy drugs is a current, complex research focus. Drug-resistant CLs are vital models for exploring drug resistance mechanisms in tumor cells [26–28]. Newly established CLs closely maintain primary tumor characteristics, providing research outcomes closest to real-world human scenarios [29–31]. DPC-X3 cells, identified with multidrug resistance, represent an intrinsic multidrug-resistant CL, making them an excellent model to investigate drug resistance mechanisms in AC. Understanding the resistance mechanism of DPC-X3 cells is anticipated to aid in the diagnosis, treatment, and drug development for intestinal ampullary cancer.

The abnormal chromosome count in cancer cells has been strongly associated with unfavorable patient outcomes [32, 33]. Recent research suggests that triploidy might correlate with innate drug resistance in tumors, whereas those with more than four sets are linked to developed drug resistance [34]. The karyotype of DPC-X3 cells is notably complex, with approximately 20% of cells being subtriploid. This complexity might contribute to the inherent multidrug resistance observed in DPC-X3.

EMT represents a transformation where epithelial cells gain mesenchymal traits, a phenomenon associated with tumor resistance [35–39]. EMT typically involves a diminish in E-cadherin, and an increase in Vimentin expression typically occurs. Alterations in gene expression during EMT lead to various phenotypic shifts, including changes in cellular morphology, diminished adhesion, and acquisition of stem cell–like properties. Crucial signaling cascades implicated in EMT encompass transforming growth factor-β, Wnt, Notch, and hedgehog pathways [40–42]. IHC examination revealed reduced E-cadherin expression and heightened Vimentin expression in DPC-X3 cells, indicating EMT characteristics, which likely contribute significantly to its inherent multidrug resistance.

The mouse transplant model holds immense value and has been pivotal in our in vivo research on tumor mechanisms, development, and drug testing [43, 44]. DPC-X3 cells inoculated subcutaneously into NXG mice result in swift and uniform establishment of transplanted tumors with a brief latency interval and a 100% formation frequency. Pathological examination revealed similarities between the histological characteristics of DPC-X3 grafts and those of primary tumors. These findings underscore the DPC-X3 transplantation tumor as an exceptional in vivo experimental prototype.

The main limitation of this investigation is the lack of comparison between DPC-X3 and SNU869, mainly because the type classification of SNU869 is not so certain. SNU869 was reported by Ku JL in 2002 [45], but H&E results of the original tissue were not reported in that article; in 2016, Lai et al. determined SNU869 as an intestinal-type AC CL through IHC [11], but the type classification of AC predominantly relies on morphological assessment through H&E staining. Based on this information, comparing these two CLs has limited significance. Fortunately, our team is about to establish another intestinal-type AC CL. Next, our group will conduct further research based on these established and ongoing CLs. This study mainly conducted preliminary verification and characterization of DPC-X3 at the macro level. In the future, our group will conduct in-depth molecular research based on the established AC CLs to further reveal the development mechanism of AC and prevention and treatment methods for this cancer.

In summary, this study introduced a novel intestinal-type AC CL, DPC-X3, derived from a Chinese man. This newly established CL offers a promising and robust experimental model for fundamental research and drug development in the context of intestinal-type ampullary cancer.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Bullet Edits (http://www.bulletedits.cn) for English language editing of the manuscript.

Author contributions

C.P.C, X.M, Y.H.S and C.Y performed the cell culture. C.P.C, X.M, Y.H.S, C.Y, H.T and L.L performed identification of the cell line, and were major contributors in writing the manuscript. C.P.C, X.M, Y.H.S, W.C.Z and H.X analyzed and interpreted the results of the detection of this novel cell line. C.Y, H.T, L.L, Z.F.W and H.Z modified the images and were involved in data processing. C.Y, H.T, J.F.Y, Z.Z.Y, L.M and H.Z were responsible for specimen collection. C.P.C, X.M, Z.F.W, J.F.Y, Z.Z.Y and L.M produced the pathological sections. C.P.C, X.M, Y.H.S, C.Y, H.X, Z.H, L.Y.C, K.R.W and N.L organized the data for all the experiments. H.X, W.C.Z and L.P.W conceived and designed and supervised the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 82260555, 82360510 and 82074195), Natural Science Foundation of Gansu Province (Grants 23JRRA1601 and 23JRRA0929), Gansu Provincial University Innovation Foundation (Grants 2021B-161 and 2022 A-063), Lanzhou Science and Technology Plan Project (Grant 2023-2-38), Intra-Hospital Fund of the First Hospital of Lanzhou University (Grants ldyyyn2022-12, ldyyyn2023-59 and ldyyyn2023-31), Chengguan District Science and Technology Plan (Grant 2023-11-6).

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the NCBI repository. Accession to cite for these SRA data: PRJNA1194522. Submission ID: SUB14910632. Databank URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA1194522.

Declarations

Ethical approval

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Lanzhou University Second Hospital (2023 A-381). Informed consent was obtained from the patient. The animal procedures were approved by the Medical Animal Experiment Ethics Committee of Lanzhou University Second Hospital (D2023-318).

Consent for publication

We have obtained consents to publish this paper from all the participants of this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Changpeng Chai, Xin Miao, Yuanhui Su and Cheng Yu have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship.

Linpei Wang, Wence Zhou and Hao Xu contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Linpei Wang, Email: wlp@fjmu.edu.cn.

Wence Zhou, Email: zhouwc129@163.com.

Hao Xu, Email: amoyxu@126.com.

References

- 1.Zheng-Pywell R, Reddy S. Ampullary cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 2019;99(2):357–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang CY, Chao YJ, Chen YL, Wang TW, Phan NN, Hsu HP, et al. Upregulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α and the lipid metabolism pathway promotes carcinogenesis of ampullary cancer. Int J Med Sci. 2021;18(1):256–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawata J, Koga Y, Noguchi S, Shimada Y, Yamada Y, Yamamoto T, et al. Clinicopathologic features and genetic alterations in mixed-type ampullary carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2023;36(8):100181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kimura W, Futakawa N, Yamagata S, Wada Y, Kuroda A, Muto T, et al. Different clinicopathologic findings in two histologic types of carcinoma of papilla of Vater. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1994;85(2):161–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND. WHO classifification of tumours of the digestive system. 4th ed. IARC; 2010.

- 6.WHO Classifification of Tumours Editorial Board. WHO classifification of tumors: digestive system tumours. 5th ed. IARC; 2019.

- 7.Yeh CC, Jeng YM, Ho CM, Hu RH, Chang HP, Tien YW. Survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy for ampullary cancer is not affected by age. World J Surg. 2010;34(12):2945–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rizzo A, Dadduzio V, Lombardi L, Ricci AD, Gadaleta-Caldarola G. Ampullary carcinoma: an overview of a rare entity and discussion of current and future therapeutic challenges. Curr Oncol. 2021;28(5):3393–402. d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel M, Uboha NV. Treatment approach to adenocarcinoma of the ampulla of vater. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2021;22(11):103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu H, Chai CP, Miao X, Tang H, Hu JJ, Zhang H, et al. Establishment and characterization of a new human ampullary carcinoma cell line, DPC-X1. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29(17):2642–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lai ZW, Bolm L, Fuellgraf H, Biniossek ML, Makowiec F, Hopt UT, et al. Characterization of various cell lines from different ampullary cancer subtypes and cancer associated fibroblast-mediated responses. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo L, Xiang Y, Dou Y, Yin Z, Xu X, Tang L, et al. GBCdb: RNA expression landscapes and ncRNA-mRNA interactions in gallbladder carcinoma. BMC Bioinformatics. 2023;24(1):12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin SJ, Gagnon-Bartsch JA, Tan IB, Earle S, Ruff L, Pettinger K, et al. Signatures of tumour immunity distinguish Asian and non-Asian gastric adenocarcinomas. Gut. 2015;64(11):1721–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nassour I, Mokdad AA, Minter RM, Polanco PM, Augustine MM, Mansour JC, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in a national cohort of ampullary cancer patients. J Surg Oncol. 2018;117(2):220–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hattori E, Oyama R, Kondo T. Systematic review of the current status of human sarcoma cell lines. Cells. 2019;8(2):157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miao X, Hu J, Chai C, Tang H, Zhao Z, Luo W, et al. Establishment and characterization of a new intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma cell line derived from a Chinese patient. Cancer Cell Int. 2022;22(1):418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuemmerle A, Decosterd LA, Buclin T, Liénard D, Stupp R, Chassot PG, et al. A phase I pharmacokinetic study of hypoxic abdominal stop-flow perfusion with gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer and refractory malignant ascites. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2009;63(2):331–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qiu F, Zhao X. Study on the sensitivity of primary tumor cells of patients with cervical cancer to chemotherapeutic combinations. J BUON. 2018 Jan-Feb;23(1):117–23. [PubMed]

- 19.Sondak VK, Bertelsen CA, Kern DH, Morton DL. Evolution and clinical application of a rapid chemosensitivity assay. Cancer. 1985;55(6):1367–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kusumoto T, Sakaguchi Y, Maehara Y, Nakashima T, Furusawa M, Sugimachi K. Comparison of in vitro anticancer chemosensitivity between human squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma. Oncology. 1992;49(5):343–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roh YH, Kim YH, Lee HW, Kim SJ, Roh MS, Jeong JS, et al. The clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical characteristics of ampulla of Vater carcinoma: the intestinal type is associated with a better prognosis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54(78):1641–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carter JT, Grenert JP, Rubenstein L, Stewart L, Way LW. Tumors of the ampulla of Vater: histopathologic classification and predictors of survival. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207(2):210–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luchini C, Veronese N, Nottegar A, Riva G, Pilati C, Mafficini A, et al. Perineural invasion is a strong prognostic moderator in ampulla of Vater carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Pancreas. 2019;48(1):70–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kohler I, Jacob D, Budzies J, Lehmann A, Weichert W, Schulz S, et al. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of carcinomas of the papilla of Vater has prognostic and putative therapeutic implications. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;135(2):202–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ecker BL, Vollmer CM Jr, Behrman SW, Allegrini V, Aversa J, Ball CG, et al. Role of adjuvant multimodality therapy after curative-intent resection of ampullary carcinoma. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(8):706–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amaral MVS, de Sousa Portilho AJ, da Silva EL, de Oliveira Sales L, da Silva Maués JH, de Moraes MEA, et al. Establishment of drug-resistant cell lines as a model in experimental oncology: a review. Anticancer Res. 2019;39(12):6443–6455. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Casadevall D, Hernández-Prat A, García-Alonso S, Arpí-Llucià O, Menéndez S, Qin M, et al. mTOR inhibition and T-DM1 in HER2-positive breast cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2022;20(7):1108–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gandullo-Sánchez L, Pandiella A. An anti-EGFR antibody-drug conjugate overcomes resistance to HER2-targeted drugs. Cancer Lett. 2023;554:216024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mirabelli P, Coppola L, Salvatore M. Cancer cell lines are useful model systems for medical research. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(8):1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hirsch D, Seyfried S, Staib T, Fiedler D, Sauer C, Ried T, et al. Newly established gastrointestinal cancer cell lines retain the genomic and immunophenotypic landscape of their parental cancers. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):17895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qiu Z, Zou K, Zhuang L, Qin J, Li H, Li C, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines retain the genomic and transcriptomic landscapes of primary human cancers. Sci Rep. 2016;6:27411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen Y, Yang Z, Wang Y, Wang J, Wang C. Karyotyping of circulating tumor cells for predicting chemotherapeutic sensitivity and efficacy in patients with esophageal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Y, Liu Y, Zhang L, Tong L, Gao Y, Hu F, et al. Vimentin expression in circulating tumor cells (CTCs) associated with liver metastases predicts poor progression-free survival in patients with advanced lung cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2019;145(12):2911–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang M, Ma Y, Lv C, Li S, Lu F, Zhang S, et al. Aneuploid circulating tumor cells as a predictor of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Gen Med. 2021;14:6609–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sommers CL, Heckford SE, Skerker JM, Worland P, Torri JA, Thompson EW, et al. Loss of epithelial markers and acquisition of vimentin expression in adriamycin- and vinblastine-resistant human breast cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 1992;52(19):5190–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Debaugnies M, Rodríguez-Acebes S, Blondeau J, Parent MA, Zocco M, Song Y, et al. RHOJ controls EMT-associated resistance to chemotherapy. Nature. 2023;616(7955):168–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pastushenko I, Blanpain C. EMT transition states during tumor progression and metastasis. Trends Cell Biol. 2019;29(3):212–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hashemi M, Arani HZ, Orouei S, Fallah S, Ghorbani A, Khaledabadi M, et al. EMT mechanism in breast cancer metastasis and drug resistance: revisiting molecular interactions and biological functions. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;155:113774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ren Y, Mao X, Xu H, Dang Q, Weng S, Zhang Y, et al. Ferroptosis and EMT: key targets for combating cancer progression and therapy resistance. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2023;80(9):263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Du B, Shim JS. Targeting epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) to overcome drug resistance in cancer. Molecules. 2016;21(7):965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lamouille S, Xu J, Derynck R. Molecular mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15(3):178–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gonzalez DM, Medici D. Signaling mechanisms of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Sci Signal. 2014;7(344):re8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Massa A, Varamo C, Vita F, Tavolari S, Peraldo-Neia C, Brandi G, et al. Evolution of the experimental models of cholangiocarcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(8):2308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chuprin J, Buettner H, Seedhom MO, Greiner DL, Keck JG, Ishikawa F, et al. Humanized mouse models for immuno-oncology research. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023;20(3):192–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ku JL, Yoon KA, Kim IJ, Kim WH, Jang JY, Suh KS, et al. Establishment and characterisation of six human biliary tract cancer cell lines. Br J Cancer. 2002;87(2):187–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the NCBI repository. Accession to cite for these SRA data: PRJNA1194522. Submission ID: SUB14910632. Databank URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA1194522.