Abstract

Background

As part of the containment of the COVID-19 pandemic, mobile handwashing stations (mHWS) were deployed in healthcare facilities in low-resource settings. We assessed mHWS in hospitals in the Democratic Republic of the Congo for contamination with Gram-negative bacteria.

Methods

Water and soap samples of in-use mHWS in hospitals in Kinshasa and Lubumbashi were quantitatively cultured for Gram-negative bacteria which were tested for antibiotic susceptibility. Meropenem resistant isolates were assessed for carbapenemase enzymes using inhibitor-based disk and immunochromatographic tests. Mobile handwashing stations that grew Gram-negative bacteria at counts > 10,000 colony forming units/ml from water or soap were defined as highly contaminated.

Results

In 26 hospitals, 281 mHWS were sampled; 92.5% had the “bucket with hand-operated tap” design, 50.5% had soap available. Overall, 70.5% of mHWS grew Gram-negative bacteria; 35.2% (in 21/26 hospitals) were highly contaminated. Isolates from water samples (n = 420) comprised 50.3% Enterobacterales (Klebsiella spp., Citrobacter freundii, Enterobacter cloacae), 14.8% Pseudomonas aeruginosa and 35.0% other non-fermentative Gram-negative bacteria (NFGNB, including Chromobacterium violaceum and Acinetobacter baumannii). Isolates from soap samples (n = 56) comprised Enterobacterales (67.9%, including Pluralibacter gergoviae (n = 13)); P. aeruginosa (n = 12) and other NFGNB (n = 6). Nearly one-third (31.2%, 73/234) of Enterobacterales (water and soap isolates combined) were multi-drug resistant; 13 isolates (5.5%) were meropenem-resistant including 10 New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase (NDM) producers. Among P. aeruginosa and the other NFGNB, 7/198 (3.5%) isolates were meropenem resistant, 2 were NDM producers. Bacteria listed as critical or high priority on the World Health Organization Bacterial Priority Pathogens List accounted for 20.3% of isolates and were present in 12.0% of all mHWS across 13/26 hospitals. Half (50.5%) of highly contaminated mHWS were used by healthcare workers and patients as well as by caretakers and visitors.

Conclusions

More than one third of in-use mobile handwash stations in healthcare facilities in a low resource setting were highly contaminated with clinically relevant bacteria, part of which were multidrug resistant. The findings urge a rethink of the place of mobile handwash stations in healthcare facilities and to consider measures to prevent their contamination.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13756-024-01506-1.

Keywords: Mobile handwashing stations, Gram-negative bacteria, Hand hygiene, Soap, Bacterial contamination, COVID-19

Introduction

Hand hygiene plays a crucial role in infection prevention and control in healthcare facilities (HCF) and in the community setting [1, 2]. It was recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a critical part in the containment of the COVID-19 pandemic [3], where it has proved its efficacy [4]. However, in 2020, at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, an estimated 2.3 billion people lacked basic hand hygiene services at home [5] and only a quarter of HCF in low-income countries had functioning hand hygiene stations at all points of care [5, 6]. WHO therefore recommended the deployment of hand hygiene stations (either for hand rubbing or hand washing) at the entrance of public and private commercial buildings [7].

According to the WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water supply, Sanitation and Hygiene, handwashing stations must provide water, liquid or bar soap, and single-use or clean reusable towels [8]. They may be fixed or portable (also called “mobile”) [5]. Mobile handwashing stations (mHWS) have originally been used in humanitarian emergencies [9]; they are also used in households and schools in low resource settings [10–12]. They are locally manufactured and require little maintenance. Moreover, they also are deployed in HCF in low resource settings, where they are considered as low-cost, high-impact interventions in hand hygiene [10, 13]. Studies in Kenya have confirmed that mHWS can be durably adopted in HCF [10, 12–15]. Several technologies of mHWS have been developed [16–19]. Widely used is the “bucket with tap” design [18], consisting of a container with a tap and a basin for wastewater, mounted on a metal tripod (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Mobile handwashing station. An outdoor-located mobile handwashing station consisting of a bucket-with tap reservoir, a hand-commanded plastic tap and a basin, mounted on a metal tripod

There are no internationally accepted standards for microbiological quality of water for handwashing. According to WHO and UNICEF, water used for handwashing must be of the highest quality possible but does not need to be of drinking water quality [20–22]. A risk-based model concluded that handwashing with non-potable water still provided net benefits (removal of pathogens) at concentrations of < 1000 Escherichia coli per 100 ml [23]; this threshold has been adopted as a guideline by UNICEF [22]. WHO and UNICEF do not recommend chlorine solutions for reasons of potential harm to users and maintenance staff, and its degradation by sunlight and heat [7, 22]. For the microbiological quality of plain soap (i.e., soap without antiseptics added), the European Commission adopted the ISO17516 Standard which mentions the presence of ≤ 103 Colony Forming Units (CFU) per ml or gram, and the absence of E. coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus and Candida albicans in 1 ml or gram [24].

Being a relatively new phenomenon and upscaled during the COVID-19 pandemic, studies about mHWS mainly addressed design, local procurement, user experience, water-saving technologies, technical maintenance, and COVID-19 related adaptations [17–19, 22]. However, although acknowledged as relevant [10, 12], the microbiological quality of in-use mHWS has not yet been assessed. In HCF, water and liquid soap are well-known reservoirs of Gram-negative bacteria, some of which are multidrug resistant [25]. Triggered by anecdotal observations of grossly contaminated mHWS in field hospitals in sub-Saharan Africa [26], we conducted a microbiological survey of in-use mHWS in hospitals in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The primary objectives were to assess the frequency, species, counts and antimicrobial susceptibility of Gram-negative bacteria contaminating water and soap of the mHWS.

Methods

Study design and period, selection of hospitals and handwashing stations

The study was carried out in Kinshasa (May–August 2021, dry season) and Lubumbashi (October–November 2021, rainy season). Kinshasa is located in the western part of DRC and has a tropical climate with a shorter dry season (dry season lasts 4 months and rainy seasons 8 months), whereas Lubumbashi is located in the southeastern part of the DRC and has a tropical climate with a more pronounced and longer dry season (dry season lasts 7 months and rainy season 5 months) [27]. During the study period, COVID-19 containment measures were implemented. Hospitals were selected in correspondence with the DRC Ministry of Health. Eligibility criteria included representativeness, accessibility, and a well-functioning hospital organization. In preparation of site visits, the hospital management was given explanations and asked for consent. It was agreed to inform the hospital staff about the survey but not to announce the exact day of the visit. Per hospital, at least 5 mHWS were targeted, with the exact number determined on site according to the number of mHWS deployed. For inclusion, the mHWS must be functional and in-use, and have (for reasons of sampling) at least 1 L of water in the reservoir.

Mobile handwash stations: observations, location, and end-users

The study site visits were conducted in the morning. For the observations of the mHWS, recorded items included design and construction, presence of commodities (water, soap, towels, and instructions), location (hospital areas), and type of end-users and photos were taken.

Patient areas were categorized into general patient areas (outpatient and inpatients excluding acute care), specialized patient areas (areas or units for high-dependency patients) and other patient-related services [28] (Table 1). End-users were categorized as community persons (visitors and caretakers), healthcare workers and the term “mixed user type” was used to denote mHWS that were used by community persons as well as by healthcare workers and/or patients.

Table 1.

Hospital areas of the sampled mobile handwashing stations (mHWS) matched with end-user groups, for 281/300 mHWS for which complete data were available

| End-users | Hospital areas | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Administrative & support areas | Public areas | General patient areas | Specialized patient areas | Other patient-related services | Total | |

| Non-clinical staff | 8 | – | – | – | – | 8 (2.9%) |

| Visitors only | 3 | 1 | 6 | 1 | – | 11 (3.9%) |

| Healthcare workers only | 14 | 1 | 21 | 42 | 8 | 86 (30.6%) |

| Patients and healthcare workers | – | – | 22 | 12 | 4 | 38 (13.5%) |

| Patients, visitors, and caretakers* | 1 | 4 | 9 | 3 | – | 17 (6.1%) |

| Visitors and healthcare workers* | 13 | 4 | 12 | 4 | 5 | 38 (13.5%) |

| Patients, healthcare workers, visitors, and caretakers* | 1 | 11 | 57 | 8 | 6 | 83 (29.5%) |

| Total (% of total mHWS) | 40 (14.2%) | 21 (7.5%) | 127 (45.2%) | 70 (24.9%) | 23 (8.2%) | 281 (100%) |

| *Mixed users (% per hospital area) | 15 (37.5%) | 19 (90.5%) | 78 (61.4%) | 15 (21.4%) | 11 (47.8%) | 138 (49.1%) |

Administrative and support areas: offices, maintenance service, meeting room

Public areas: entrance, hallway, restaurant, toilet

General patient areas: waiting areas, consultations, minor procedural areas, COVID-19 treatment center, maternity, adult hospitalization

Specialized patient areas: operating room, intensive care unit, emergency ward, labor and delivery wards, neonatology unit, medication preparation areas

Other patient-related areas: laboratory, radiology, kinesitherapy, central sterilization unit, morgue

Data in cells represent the numbers of mHWS. Mixed users of mHWS (indicated with “*”) refers to mHWS that were used by community-based persons (visitors and caretakers) as well as by healthcare workers and/or patients. Patient areas (general versus specialized) were defined according to reference 28, for details see footnote

Sampling of water and soap, laboratory work-up, colony counts

After flushing away an initial jet, 500 ml of water was collected via the reservoir tap into a 500-ml autoclavable bottle with screw cap (Schott, Mainz, Germany). Liquid soap (3 ml) was sampled from the dispenser pump or stopper nozzle into a 15-ml sterile polypropylene screw cap tube (Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany). The collected samples were immediately transported at room temperature to the laboratory (National Institute of Biomedical Research (INRB) in Kinshasa and Provincial Laboratory of Lubumbashi).

Upon reception in the laboratory, water samples were inoculated by filtration method on MacConkey agar No.3 (MC agar, CM0115B, Oxoid, Hampshire, U.K) and by the spread plate method on both MacConkey agar No.3 and Plate Count agar (PC agar, CM0325B, Oxoid), poured in Petri dishes of 90 mm diameter. For filtration, 100 ml was filtered through a 0.45 µm pore size nitrocellulose filter (18,406-47-ACN, Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany). The filter membrane was placed directly on the agar. Bar soap samples were mixed with 10 ml of sterile NaCl 0.9% in a sterile plastic zip lock bag. For soap samples, 100 µl of the samples was inoculated by the spread plate method on both agars. Incubation was done at 35 °C for 24 h in a standard atmosphere. Cultures were read after 24 h: in case of no growth, they were incubated for another 24 h and read at a total of 48 h of incubation.

Per spread plate, Gram-negative colony counts, and total colony counts were assessed respectively on MC and PC agar [25]. For low or medium growth density, all colonies per plate were counted. For samples with abundant growth of distinct colonies, colonies were counted in one quadrant and multiplied by 4. Confluent growth with no distinct colonies discernable was categorized as > 1000 colonies per plate. To obtain the number of CFU/ml, the colony counts per spread plate were multiplied by 10. For the filtration method, colonies were counted as for the spread plate method. Confluent growth was categorized as > 200 colonies per 100 ml. To obtain the number of CFU/ml, the colony counts per membrane were divided by 100.

Identification and antibiotic susceptibility testing of Gram-negative bacteria

If bacterial colonies were well isolated on the MC agar plates, one colony per morphotype and lactose reaction on the MC agar plates was subcultured onto PC agar and next stored on Tryptic Soy Agar (CM0131, Oxoid). In cases of suspicion of mixed growth, bacteria were subcultured first on MC agar to obtain isolated colonies before being processed as described above. Stored isolates were shipped to the Institute of Tropical Medicine (ITM) and identified by Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization—Time of Flight (MALDI-TOF) (Bruker MALDI Biotyper, Bruker, Billerica, MA, US, software version 4.1.80 (PYTH) 102 2017). For isolates for which MALDI-TOF did not provide an acceptable identification, biochemical identification panels (Analytical Profile Index (API) 20E and 20NE, bioMérieux, Marcy-L’Etoile, France) were used. Isolates for which API 20E or 20NE did not provide an acceptable identification were categorized to the group level of Enterobacterales, Aeromonas spp. or non-fermentative Gram-negative bacteria based on glucose fermentation on Kligler Iron Agar (Oxoid) and oxidase tests. Acinetobacter spp. isolates were tested for growth at 44 °C in Tryptic Soy Broth to distinguish between the Acinetobacter baumannii/calcoaceticus group and the other Acinetobacter species [29].

The first isolate per species and per sample (soap and water) was selected for antibiotic susceptibility testing (AST) by disk-diffusion (Neo-Sensitabs, Rosco Diagnostica A/S, Taastrup, Denmark) according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI) guidelines [30]. AST results were presented for isolates from water and soap combined; intermediate susceptible and resistant categories were merged [31]. Multidrug resistance (MDR) was defined as acquired non-susceptibility to at least one agent in 3 or more antimicrobial categories [32]. Enzymes associated with carbapenem resistance were tested with an immunochromatographic lateral-flow test (O.K.N.V.I Resist-5, Coris BioConcept, Gembloux, Belgium) and an inhibitor-based disk diffusion kit (KPC/MBL and OXA-48 Confirm kit, Rosco Diagnostica A/S) (Supplementary Table 1).

Data collection, definitions, analysis, and presentation of results

Data were recorded on paper forms and transcribed into electronic forms of a web-based Redcap database (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, US). For analysis, data were transferred to an Excel database (Microsoft version 2307, Redmond, Washington, US).

Gram-negative bacteria were grouped as (i) Enterobacterales and the Aeromonas group (further jointly referred to as Enterobacterales), (ii) P. aeruginosa and (iii) non-fermentative Gram-negative bacteria other than P. aeruginosa (referred to as “other NFGNB”). Results of colony counts displayed were those of the Gram-negative colony counts obtained by the spread plate method; if there was no growth on the spread plate, the results of the corresponding filtration plate were presented. Colony counts were grouped in 4 intervals: < 250; 251–2,500; 2,501–10,000; > 10,000 CFU/ml.

Mobile handwashing stations with growth of Gram-negative bacteria in either soap or water at any concentration ≥ 1 CFU/100ml were defined as “contaminated mHWS”, at counts > 10,000 CFU/ml, they were defined as “highly contaminated mHWS”. Bacterial species and their AST profiles were assessed for their presence on the WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List (version 2024) [33] and the List of Opportunistic Pathogens of Premise Plumbing (OPPP list) [34].

Results were calculated and expressed per total number of mHWS for which complete data of location, end-user, and microbiology results were available. In case of relevant differences, details per (sub)group were listed. Medians were presented with ranges. Differences in proportions were assessed by the chi square test of Pearson or Fisher’s Exact test [35] and considered significant at a p-value < 0.05.

Additional methods: chlorine granule residues

During the observations of the mHWS, white amorphous residues were seen, floating on the water surface, or deposited on the bottom of the water reservoir. They were supposed to be remnants of the HTH chlorine granules [36]. To confirm this assumption, a simulation experiment was conducted: HTH-70% chlorine granules (HTH, Innovative Water Care, Val de Loire, France) were added up to chlorine concentrations 0.05%, 0.5% and 1.0% in 10-L tap water volumes and the solutions were observed for appearance of residues (Supplementary Document 1).

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium (1434/20) and the ethics committee of the School of Public Health of the University of Kinshasa, DRC (ESP/CE/208/2020). Written support for the study was granted by the General Health Office of the DRC Ministry of Health. All hospital directors and interviewees provided consent. Results presented were aggregated for all hospitals and no results of individual hospitals were presented.

Results

Selected hospitals, location, and end-users of the mobile handwashing stations

Twenty-six hospitals were selected (16 at Kinshasa and 10 at Lubumbashi) and confirmed participation. They were public (n = 20/26), faith-based (n = 3/26) or private-for-profit (n = 3/26). All but 2 were in urban areas. The median number of beds was 129 (14–1092). All but one hospital comprised at least pediatrics, surgery, internal medicine, and gynecology-obstetrics.

For 281/300 (93.7%) mHWS assessed, complete data were available (184 in Kinshasa and 97 in Lubumbashi). A total of 300 mHWS were assessed (203 in Kinshasa and 97 in Lubumbashi). The median number of mHWS sampled per hospital was 10 (4–31). Two-thirds (69.4%, 195/281) of mHWS were located indoors. A quarter (24.9%) were in specialized patient areas; proportions were higher in Kinshasa compared to Lubumbashi (31.5% versus 12.4% (12/97). Conversely, proportions of sampled mHWS in administrative, support and public areas were higher in Lubumbashi compared to Kinshasa (30.9% versus 16.8% respectively). Nearly half of mHWS (49.1%) were used by mixed users (Table 1, Supplementary Table 1).

Inspection and observations of handwashing stations

Nearly all (92.5%) mHWS had the “bucket with tap” design. Except for 3 dusty reservoirs and a rusty frame, all sampled mHWS were in good condition. Most (91.5%) reservoirs had a volume ≥ 15 L; all but 2 were made from plastic and nearly all (98.9%) were closed with a dedicated lid. Most mHWS (96.4%) had a hand-operated tap, mostly (96.8%) made of plastic. One-third (35.6%) of water reservoirs had dirt and sand deposits. The median environmental temperature recorded during hospital visits was 32.6 °C (range 25.0 °C—39.0°C).

In half of mHWS (50.5%), soap was present, comprising 128 liquid soap and 14 bar soap samples. Only 11.0% mHWS had posted instructions or reminders for handwashing, and only 3.2% had cloth or paper towels for hand drying. Among the liquid soap containers, 75.0% were original containers of branded soap products, this proportion was higher in Lubumbashi versus Kinshasa (94.6%, (35/37) versus 67.0% (61/91), p = 0.001). The remaining soap containers were reused.

The laboratory experiment confirmed the white residues in the water reservoirs as remnants of HTH chlorine granules. At the 0.05% active chlorine concentration, they were scattered across the bucket’s bottom and the water surface, and the water was slightly turbid. At 0.5% and 1.0% chlorine concentrations, the residues covered the entire bottom and were confluent at the water surface; the turbidity of the water was high (i.e., the aspect of the water was cloudy). The pH associated with these concentrations reached 10.08 and 11.40 respectively (Supplementary Document 1). Chlorine granule residues were observed in 27.0% (76/281) of mHWS from 19 hospitals, and more frequently in Lubumbashi compared to Kinshasa (52.6% (51/97) versus 13.6% (25/184) mHWS, p < 0.001). For 67 mHWS, photos were available: most (88.1%, 59/67) water reservoirs showed residue densities and water turbidity equal to or exceeding those observed at the 1% chlorine concentration of the laboratory experiment (Supplementary Document 1).

Laboratory results

The median delay between sampling and laboratory processing was 4 (0–8) hours (information available for 248 mHWS). All growth occurred after 24h of incubation; no additional growth was observed at 48h of incubation.

Proportions of contaminated and highly contaminated mHWS, overview of isolates

Among 281 mHWS, 70.5% were contaminated with Gram-negative bacteria and 35.2% were highly contaminated (Tables 2 and 3). More than two-thirds of the water samples were contaminated (n = 191/281, 68.0%) versus 29.6% (42/142) soap samples. High contamination was observed at similar proportions for water and soap: 29.5% (83/281) and 22.5% (32/142) respectively. Sixteen out of the 99 highly contaminated mHWS had both highly contaminated water and soap. For all contaminated mHWS and soap and water combined, 476 and 432 non-duplicate Gram-negative isolates were available for species identification and AST respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Numbers of contaminated and highly contaminated mobile handwashing stations (mHWS) and highly contaminated mHWS which contained multidrug resistant Gram-negative bacteria

| Total | Water | Soap | Kinshasa | Lubumbashi | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total mHWS | 281 | 281 | 142 | 184 | 97 |  |

| Contaminated (% of total) | 198 (70.5%) | 191 (68.0%) | 42 (29.6%) | 147 (80.0%) | 51 (52.6%) | |

| Highly contaminated (% of total) | 99 (35.2%) | 83 (29.5%) | 32 (22.5%) | 72 (39.1%) | 27 (27.8%) | |

| Highly contaminated with MDR (% of total) | 27 (9.6%) | 27 (9.6%) | 1 (0.7%) | 21 (11.4%) | 6 (6.2%) |

Contaminated mHWS had growth of Gram-negative bacteria at concentrations ≥ 1 Colony Forming Unit (CFU)/100 ml. Highly contaminated mHWS were defined as mHWS of which water and/or soap were contaminated at concentrations > 10,000/ml CFU/ml. MDR stands for the presence of multidrug resistant Gram-negative bacteria. The Ven-diagram shows the numbers of mHWS with highly contaminated water, soap and both water and soap. Soap was present in 30/67 mHWS with highly contaminated water samples

Table 3.

Location of highly contaminated mobile handwashing stations (mHWS, n = 281) according to hospital area matched with user groups

| End–users (numbers of mHWS) | Hospital areas (total number of mHWS) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Administrative & Support areas (n = 40) |

Public areas (n = 21) |

General patient areas (n = 127) |

Specialized patient areas (n = 70) |

Other patient-related services (n = 23) |

Total (n = 281) |

|

| Non–clinical staff (n = 8) | 1 (1) | – | – | – | – | 1 (1) |

| Visitors only (n = 11) | 1 | 1 | – | – | 2 | |

| Healthcare workers only (n = 86) | 6 (1) | 1 | 6 (2) | 17 (7) | 3 | 33 (10) |

| Patients and healthcare workers (n = 38) | – | – | 7 | 4 (2) | 2 | 13 (2) |

| Patients, visitors and caretakers* (n = 17) | – | 1 | 4 | – | – | 5 |

| Visitors and healthcare workers* (n = 38) | 3 | 5 (2) | 1 | 2 | 11 (2) | |

| Patients, healthcare workers, visitors and caretakers* (n = 83) | – | 1 (1) | 26 (9) | 5 (2) | 2 | 34 (12) |

| Total highly contaminated mHWS | 11 (2) | 3 (1) | 49 (13) | 27 (11) | 9 | 99 (27) |

| *Mixed users (n = 138) | 3 | 2 (1) | 35 (11) | 6 (2) | 4 | 50 (14) |

Highly contaminated mHWS were defined as mHWS of which water and/or soap were contaminated at concentrations > 10,000 Colony Forming Units/ml. Data in the cells represent mHWS, numbers in brackets and italics represent numbers of highly contaminated mHWS with multidrug resistant (MDR) organisms. Mixed users of mHWS (indicated with “*”) refers to mHWS that were used by community-based persons (visitors and caretakers) as well as by healthcare workers and/or patients. For details of hospital areas, see Table 1

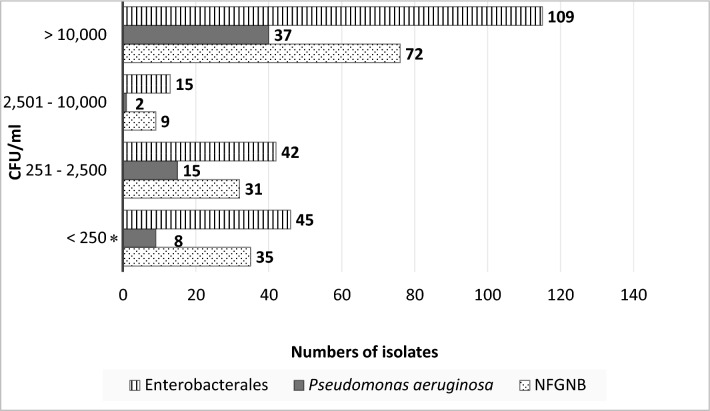

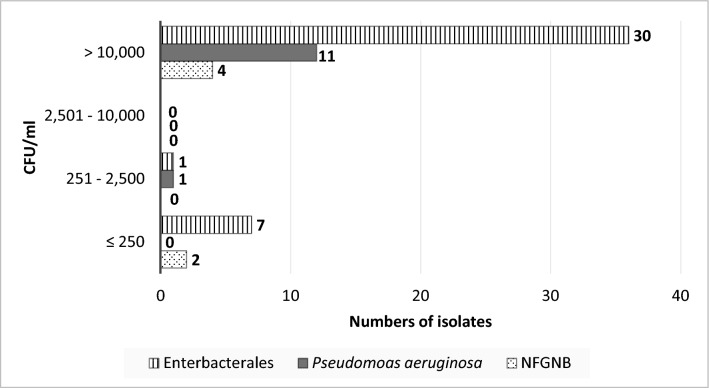

The isolates from water samples (n = 420 isolates from 177 mHWS) comprised Enterobacterales (50.3%, 211/420), P. aeruginosa (14.8%, 62/420) and other NFGNB (35.0%, 147/420) (Supplementary Table 3A). Half of them (51.9%, 218/420) were associated with counts > 10,000 CFU/ml (Fig. 2), including Klebsiella spp., C. freundii complex, Enterobacter cloacae complex and Aeromonas hydrophila (each accounting for > 10 mHWS), as well as Salmonella salamae (Table 4, Supplementary Table 3A). NFGNB isolates associated with counts > 10,000 CFU/ml were Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (n = 12 mHWS), Pseudomonas alcaligenes (n = 9), Chromobacterium violaceum (n = 2) and Acinetobacter baumannii and nosocomialis (n = 4 and 2, respectively). (Supplementary Table 3A). Among the soap isolates (n = 56 isolates from 39 mHWS), Enterobacterales represented two-thirds (67.9%, 38/56) and P. aeruginosa and other NFGNB accounted for 12 and 6 isolates, respectively (Supplementary Table 3B). Most (80.4%, 45/56) of these isolates were associated with counts > 10,000 CFU/ml (Table 5, Fig. 3). They included Pluralibacter gergoviae (n = 13 mHWS), present in different brands of soap samples (Supplementary Table 3B).

Fig. 2.

Associated Gram-negative counts for 420 Gram-negative isolates grown from contaminated water samples (n = 177) of mobile handwashing stations (mHWS). The bars represent Enterobacterales (n = 211), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n = 62), and non-fermentative Gram-negative bacteria other than P. aeruginosa (n = 147). Abbreviations: NFGNB = Non-fermentative Gram-negative bacteria other than P. aeruginosa, CFU/ml = colony forming units per milliliter. Legend: * = 56/88 isolates with < 250 CFU/ml were recovered from filtration plates only: 26 Enterobacterales, 7 Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and 23 NFGNB

Table 4.

Bacterial species of Gram-negative bacteria isolated from highly contaminated water samples of mobile handwashing stations (mHWS)

| Bacterial species | Numbers of mHWS with water samples affected |

|---|---|

| Enterobacterales (n = 109) | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae* + K. oxytoca* | 36 + 3 |

| Enterobacter cloacae* + E. cloacae complex | 5 + 20 |

| Citrobacter freundii + C. freundii complex | 11 + 2 |

| Aeromonas hydrophila* | 11 |

| Enterobacter bugandensis | 4 |

| Enterobacter sp. | 1 |

| Serratia marcescens* | 4 |

| Morganella morganii | 3 |

| Phytobacter ursingii | 1 |

| Providencia alcalifaciens + P. rettgeri | 1 + 1 |

| Escherichia coli | 1 |

| Pantoea dispersa | 1 |

| Citrobacter koseri | 1 |

| Salmonella salamae | 1 |

| Kluyvera ascorbata | 1 |

| No species Identification | 1 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n = 37) | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa* | 37 |

| Non-fermentative Gram-negative bacteria other than Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n = 72) | |

| Pseudomonas alcaligenes | 9 |

| Pseudomonas mendocina | 1 |

| Pseudomonas otitidis | 1 |

| Pseudomonas sp. | 7 |

| Pseudomonas stutzeri | 6 |

| Pseudomonas putida* | 1 |

| Pseudomonas putida group | 2 |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia* | 12 |

| Comamonas aquatica | 7 |

| Comamonas testosteronii | 1 |

| Comamonas sp. | 3 |

| Chromobacterium violaceum | 2 |

| Alcaligenes faecalis* | 2 |

| Burkholderia cepacia complex* | 3 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii* | 4 |

| Acinetobacter bereziniae | 1 |

| Acinetobacter johnsonii | 1 |

| Acinetobacter junii | 1 |

| Acinetobacter nosocomialis | 2 |

| Acinetobacter seifertii | 1 |

| Brevundimonas vesicularis | 1 |

| Shewanella xiamenensis | 2 |

| No species Identification | 2 |

| Total | 218 |

The total number of isolates (n = 218) exceeds the number of highly contaminated mHWS (n = 83) as some samples contained more than one species. Bacterial species indicated with “*” are listed as Opportunistic Pathogens of Premise Plumbing (n = 118) (reference 34)

Table 5.

Bacterial species of Gram-negative bacteria isolated from highly contaminated liquid and bar soap samples (n = 30 and 2 respectively) of mobile handwashing stations (mHWS, n = 32)

| Bacterial species | Numbers of mHWS with soap samples affected |

|---|---|

| Enterobacterales (n = 30) | |

| Pluralibacter gergoviae | 13 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae* | 8 |

| Enterobacter cloacae complex + E. cloacae* | 1 + 1 |

| Serratia rubidaea + S. marcescens* | 2 + 1 |

| Citrobacter freundii | 1 |

| Citrobacter koseri | 2 |

| No species identification | 1 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n = 11) | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa* | 11 |

| Non-fermentative Gram-negative bacteria other than Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n = 4) | |

| Pseudomonas stutzeri | 1 |

| Pseudomonas sp. | 1 |

| Alcaligenes faecalis* | 2 |

| Total | 45 |

The total number of isolates (n = 45) exceeds the number of soap samples (n = 32) as several samples contained more than one species. Bacterial species indicated with “*” are listed as Opportunistic Pathogens of Premise Plumbing (n = 23) (reference 34)

Fig. 3.

Associated Gram-negative counts for 56 Gram-negative species grown from contaminated soap samples (n = 39) of mobile handwashing stations (mHWS). The bars represent Enterobacterales (n = 38), P. aeruginosa (n = 12) and non-fermentative Gram-negative bacteria other than P. aeruginosa (n = 6). Abbreviations: NFGNB = Non-fermentative Gram-negative bacteria other than P. aeruginosa, CFU/ml = colony forming units per milliliter

A total of 36.3% (85/234) of Enterobacterales were resistant to third generation cephalosporins including 31.2% (73/234) which were MDR and 5.5% (13/234) which were meropenem resistant (Table 6). Most (12/14) P. gergoviae isolates were pan-susceptible. Among the 13 meropenem-resistant Enterobacterales isolates, 10 were New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase (NDM) carbapenemase producers (Supplementary Table 1). Among P. aeruginosa and the other NFGNB, 3.0% (6/198) isolates were MDR and 3.5% (7/198) were meropenem resistant (Table 7); among them, 2 were NDM-carbapenemase producers (Acinetobacter baumannii and Acinetobacter bereziniae), and one P. aeruginosa produced Verona Integron-encoded Metallo-β-lactamase (VIM). Three isolates of Pseudomonas otitidis were meropenem resistant but did not show a corresponding carbapenemase enzyme (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 6.

Antibiotic resistance profiles of Enterobacterales/Aeromonas spp. isolates from water and soap samples of mobile handwashing stations (mHWS) with growth of Gram-negative bacteria

| Antibiotics |

Enterobacter spp.a (n = 68) |

Klebsiella spp.b (n = 77) |

Citrobacter freundii groupc (n = 22) |

Pluralibacter gergoviae (n = 14) |

Serratia spp.d (n = 13) |

Morganella/Providencia groupe (n = 12) |

Aeromonas spp. (n = 11) |

Citrobacter spp. other than C. freundii (n = 4) |

Phytobacter ursingii (n = 4) |

Pantoea dispersa (n = 2) |

Escherichia coli (n = 3) |

Proteus mirabilis (n = 1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ampicillin | 68 | 77 | 22 | – | 13 | 12 | 11 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid | 68 | 24 | 22 | – | 13 | 12 | 7 | – | 2 | 2 | – | – |

| Ceftriaxone | 37 | 42 | 9 | – | 1 | 5 | 3 | – | 3 | – | 2 | 1 |

| Piperacillin + tazobactam | 3 | 7 | 2 | – | – | 1 | – | – | 1 | – | – | – |

| Gentamicin | 19 | 18 | 4 | – | 1 | 3 | – | – | 2 | – | 1 | – |

| Amikacin | 3 | 1 | – | – | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| TMP/SMX | 40 | 42 | 12 | 2 | 1 | 10 | 6 | – | 3 | – | 3 | 1 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 33 | 37 | 7 | – | – | 7 | 5 | – | 1 | – | 1 | 1 |

| 3GC-resistant | 26 | 38 | 8 | – | 1 | 4 | 3 | – | 2 | – | 2 | 1 |

| Meropenem | 4 | 5 | 1 | – | 1 | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | 1 |

| MDR | 25 | 32 | 5 | – | 1 | 4 | 1 | – | 2 | – | 2 | 1 |

| WHO priority pathogens | 26 | 38 | 8 | – | 1 | 4 | 3 | – | 2 | – | 2 | 1 |

Data were available for 234/249 isolates from 133 mHWS; 10 isolates were not identifiable and another 5 did not grow upon retrieval. Not listed are Salmonella salamae (n = 1, pan-susceptible), Kluyvera ascorbata (n = 1, pan-susceptible) and Leclercia adecarboxylata (n = 1, ampicillin resistant only). Data in the cells represent the numbers of isolates which were intermediate susceptible or resistant to the corresponding antibiotics. Bacterial species were grouped according to EUCAST expected antimicrobial resistance phenotypes (EUCAST2023). Abbreviations: TMP/SMX = trimethoprim + sulfamethoxazole, 3GC-resistant = third generation cephalosporin-resistant, MDR = multidrug resistant. Enterobacterales that display 3GC or carbapenem resistance (n = 85) are listed as “critical priority group” among the WHO List of Priority Pathogens, i.e., bacterial pathogens of public health importance to guide research, development, and strategies to prevent and control antimicrobial resistance (reference 33)

aEnterobacter spp. includes Enterobacter cloacae (n = 12), E. cloacae complex (n = 48), E. aerogenes (n = 1), E. bugandensis (n = 7)

bKlebsiella spp. includes Klebsiella pneumoniae (n = 73), and K. oxytoca (n = 4)

cCitrobacter freundii group includes Citrobacter freundii (n = 20) and C. freundii complex (n = 2)

dSerratia spp. includes Serratia marcescens (n = 11), and S. rubidaea (n = 2)

eMorganella/Providencia group includes Morganella morganii (n = 8), Providencia alcalifaciens (n = 2), and P. rettgeri (n = 2)

Table 7.

Antibiotic susceptibility profile of non-fermentative Gram-negative bacteria isolated from water and soap samples of mobile handwashing stations (mHWS) with growth of Gram-negative bacteria

| Antibiotics |

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n = 74) |

Pseudomonas spp. (n = 49) |

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (n = 19) |

Comamonas spp. (n = 20) |

Acinetobacter group 1a (n = 14) |

Burkholderia cepacia complex (n = 7) |

Acinetobacter group 2b (n = 7) |

Alcaligenes faecalis (n = 7) |

Elizabethkingia meningoseptica (n = 1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ceftriaxone | 14 | 2 | |||||||

| Ceftazidime | 4 | 5 | 3 | 1 | – | 1 | 1 | ||

| Piperacillin + tazobactam | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | – | 1 | ||

| Gentamicin | 3 | 4 | 10 | 1 | 1 | – | |||

| Amikacin | 1 | 1 | 8 | 1 | – | – | |||

| TMP/SMX | 5 | 2 | – | 3 | – | ||||

| Ciprofloxacin | 3 | 7 | 18 | 2 | 1 | – | |||

| Minocycline | 1 | – | |||||||

| Meropenem | 2 | 3c | – | 1d | – | 1e | – | – | |

| MDR | 1 | 1 | – | 2 | 1 | – | 1 | – | – |

| WHO priority pathogens | 2 | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | – | – |

Data were available for 198/227 isolates from 140 mHWS. For 22 isolates, no CLSI guidelines for antibiotic susceptibility testing were available (Brevundimonas vesicularis, Chromobacterium violaceum, Cupriavidus spp., Delftia acidovorans, Herbaspirillum huttiense, Ochrobactrum spp., Ralstonia pickettii, Rhizobium radiobacter, Shewanella xiamenensis); 4 isolates were not identifiable to the species level, and another 3 isolates did not grow upon retrieval. Data in the cells represent the numbers of isolates which were intermediate susceptible or resistant to the corresponding antibiotics. Bacterial species were grouped according to EUCAST expected antimicrobial resistance phenotypes (EUCAST2023). A grey box indicates that the antibiotic was not listed for testing by the CLSI guidelines. Abbreviations: TMP/SMX = trimethoprim + sulfamethoxazole, MDR = multidrug resistant. Acinetobacter baumannii (n = 2) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n = 1) displaying carbapenem resistance listed as “critical group” respectively “high priority” among the WHO List of Priority Pathogens, i.e., bacterial pathogens of public health importance to guide research, development, and strategies to prevent and control antimicrobial resistance (reference 33)

aAcinetobacter group1 contains Acinetobacter baumannii (n = 7), A. baumannii complex (n = 1), A. nosocomialis (n = 5), and A. pittii (n = 1)

bAcinetobacter group2 contains Acinetobacter modestus (n = 1), A. junii (n = 2), A. bereziniae, A. seifertii, A. schindleri, and A. johnsonii (n = 1 each)

cMeropenem resistant species were Pseudomonas otitidis (n = 2 out of 3), and Pseudomonas putida (n = 1 out of 3)

dMeropenem resistant species = Acinetobacter baumannii (n = 1 out of 7)

eMeropenem resistant species = Acinetobacter bereziniae (n = 1 out of 1)

Highly contaminated mHWS, distribution over the hospital areas, users, and study sites

Proportions of highly contaminated mHWS were higher in hospital areas with patient-related activities compared to the administrative & support areas and public areas (38.6% (85/220) versus 22.9% (14/61) respectively, p = 0.02) (Table 3). Half (50.5%, 50/99) of highly contaminated mHWS was of the mixed-user type (Table 3). Highly contaminated mHWS were observed in 21/26 hospitals, and proportions tended to be higher in Kinshasa compared to Lubumbashi (39.1% (72/184), versus 27.8% (27/97), p = 0.05) (Table 2). Among mHWS with chlorine granule residues, the proportion of highly contaminated mHWS was considerably lower compared to the other mHWS (19.7% (15/76) versus 41.0% (84/205), p < 0.001). Proportions of highly contaminated mHWS with MDR bacteria were highest in the specialized patient areas (15.7%, 11/70, including neonatology (n = 4), intensive care (n = 3), delivery room (n = 2) and critical care and emergency units (n = 1 each)) (Table 3).

Isolates and highly contaminated mHWS according to CDC and WHO listing

Half (50.2%, 239/476) of isolates belonged to the list of Opportunistic Pathogens of Premise Plumbing (OPPP) [34] (Tables 4, 5). They were present in 86.8% (86/99) of highly contaminated mHWS representing 30.6% (86/281) of all mHWS across 20 out of 26 hospitals.

Bacteria listed as critical or high priority on the WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List [33] accounted for 20.3% (88/432) isolates (Tables 6, 7). They were present in 34.3% (34/99) of highly contaminated mHWS representing 12.0% (34/281) of all mHWS across half (n = 13) of the hospitals.

Sources of water supply

In all but one hospital (n = 25), a staff member was present for an interview. All hospitals obtained water from an improved water source, including the municipal piped water supply, boreholes, and distribution by a beverage company (17, 14 and 3 hospitals respectively). Shortage or interruption of water supply was reported by 12/25 interviewees and had occurred days (n = 6), weeks (n = 2) and months up to years (n = 4) ago; 3 of these interruptions had lasted for more than a week.

Discussion

Bacterial contamination of fixed handwash stations and liquid soap is a well-known cause of healthcare-associated infections worldwide, often with strong causation [37–42]. Healthy people are not vulnerable to most of the bacteria involved, but patients in HCF may be susceptible due to general immunodeficiencies and immature or damaged skin or mucosa barriers [34, 37, 38, 43]. The present study showed that more than a third of in-use mHWS in hospitals in a resource-limited setting were highly contaminated with Gram-negative bacteria. These findings are of concern, because of the clinical relevance, associated AMR and colony counts of the bacteria and the high proportion, healthcare facility setting and end-user profile of the affected mHWS.

Clinical relevance, associated AMR and colony counts of the contaminating bacteria.

Most (86.8%) of the highly contaminated mHWS contained at least one species listed on the OPPP list (“opportunistic pathogens of premise plumbing”) which have been reported from healthcare-associated infections, mainly in HIC [34, 37, 39]. In addition, virulent pathogenic bacteria were isolated, such as Salmonella salamae and Chromobacterium violaceum. The latter species causes community-acquired bloodstream infections in healthy adults in tropical regions and has been reported as a cause of healthcare-associated infections in Nigeria [44, 45]. Among the mHWS which were contaminated at concentrations below 104 CFU/ml a similar spectrum of bacteria was observed.

Pluralibacter gergoviae was found in 13 soap samples of highly contaminated mHWS. The species (previously Enterobacter gergoviae) is naturally resistant to preservatives and has been reported worldwide as a contaminant of cosmetic products. Despite its low virulence and natural susceptibility to antibiotics, MDR P. gergoviae has been associated with healthcare-associated infections [46–48].

The colony counts associated with the highly contaminated mHWS largely exceeded the above-mentioned risk-based thresholds [22–24]. These criteria were partly based on experimental studies showing increased contamination of hands during washing with water containing E. coli above 1,000 CFU/100 ml [23] and when using liquid soap containing Serratia marcescens at concentrations ≥ 3.7 log 10 CFU/ml (5.000 CFU/ml) [49]. For liquid soap, contamination with Enterobacterales with high colony counts (≥ 104 CFU/ml) has been reported also from high-income community settings [25, 41, 42, 47, 50]. For water samples, there are no data for comparison as previous studies in LMIC focused on drinking water and reported colony counts capped at ≥ 100 CFU/100ml [51–53].

A considerable proportion of isolates (20.3%) belonged to species listed as critical or high priority on the WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List, which provides guidance for research, development, and strategies to prevent and control AMR, based on public health importance [33]. Although the proportion of MDR among NFGNB was tenfold lower compared to the Enterobacterales (3.0% versus a third), it should be noted that the NFGNB display natural resistance to many antibiotic classes and are also categorized as “difficult to treat” organisms [54, 55]. Furthermore, K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii—present in 71.9% of highly contaminated mHWS—appeared among the worldwide top-10 bacterial species causing deaths attributable to and associated with AMR [56].

Most of concern was the occurrence of meropenem (carbapenem) resistance. Carbapenem resistance is spreading across sub-Saharan Africa and the present findings are line with the estimated 1 to 5% proportion of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella spp. in DRC [57]. The NDM and VIM carbapenemases are metallo-beta-lactamases, which are resistant to the newly developed beta-lactamase inhibitors [58]. Among the NFGNB, 3 out of 4 Pseudomonas otitidis isolates were meropenem resistant. P. otitidis isolates produce a sub class B3 metallo-β-lactamase (named POM-1) and can cause invasive infections in immunocompromised patients [59, 60].

Proportion, healthcare facility setting, and end-user profile of the affected mHWS

The proportions of contaminated and highly contaminated mHWS were 70.5% and 35.2% respectively. As publications about contamination of hospital water systems were outbreak-related, it is difficult to compare proportions. Nevertheless, these proportions were consistent among hospitals and can be considered as very high. Bacterial contamination of bar and liquid soap products has been demonstrated in cross-sectional studies worldwide, proportions ranging between 7.3% and 100% [41, 42].

Highly contaminated mHWS were most frequently observed in patient-related hospital areas, where the frequency and impact of healthcare-associated infections are expected to be the highest in specialized patient areas [37, 38]. Among the wards with highly contaminated mHWS with MDR bacteria included neonatology and maternity, services which in LMIC are notable for numbers and vulnerability of patients [43, 61].

Half (50.5%) of the highly contaminated mHWS (including those with MDR bacteria) were mixed user type. In LMIC, caretakers (mostly family members) may stay overnight and are numerous in the neonatal and maternity wards. They provide food and basic hygienic care to patients and sometimes assist in aseptic nursing procedures [61, 62]. Use of highly contaminated mHWS may make them not only a potential vector for handborne transmission of MDR bacteria to patients but might also favor the spread of the MDR bacteria to the community.

The chain of infection and risk factors for bacterial contamination of water and soap

The sources and risk factors promoting transfer and amplification of bacteria in liquid soap containers have recently been reviewed [41, 42]. Tap water is not sterile and even when an improved water source is used, water at the point of use may be contaminated because of aged infrastructure, disruptions of supply, and stagnation [8, 53]. Re-use of non-autoclavable single use containers (without appropriate reprocessing), using beyond the expiry date or the period-after-opening are risk factors for bacterial growth. Topping-up containers and hand-touching of the spout exit of the container’s pump may transfer bacteria into the containers [63, 64]. Furthermore, there may be biofilm production by bacteria, consisting of an extracellular matrix which protects them from desiccation and disinfectants [42].

For mHWS water reservoirs and taps, risk factors are probably similar to those listed above but have only partly been studied. Contamination of the mHWS can occur through contaminated water, hand contact of the tap or handling of the containers [52]. In addition, the wastewater basin is right under the mHWS tap and backsplash of the water jet might contaminate the tap, as has been observed in the case of sink outlets [65]. Biofilm formation is favored by plastic taps (representing a high touch surface), particularly when scratches and grooves are present, low water flow rates, inaccessibility of the tap’s internal mechanisms for cleaning, filling by topping-up, and interruptions of replenishment leading to standing water residues. Further, high temperatures (over 30°C at the present study sites) promote growth of Gram-negative bacteria [66–68].

Once transferred to hands, the contaminated hands may further transmit the bacteria to patients, food, or medical or household items, known as handborne transmission [34]. Dispersion of bacteria from fixed handwash stations to the environment or humans through backsplashes may reach up to 1.8 m distance [69, 70], and this transmission route probably also applies to mHWS.

Limitations and strengths

A limitation was the selection of hospitals (based on criteria of functionality) and mHWS (restricted to well-functioning mHWS). Furthermore, the observation of high concentrations of chlorine granule remnants was unexpected as chlorination was not recommended by the DRC health authorities and raised suspicion of purposely adding use. Likewise, the high numbers of original single-use soap containers in Lubumbashi were unexpected given previous observations in LMIC [25, 42]. Furthermore, the study focused on fast-growing pathogens and was not designed to detect OPPP-listed mycobacteria.

Among the strengths were the high sample size, and the robust microbiological work-up. The findings were consistent across the hospitals and the lower proportions of highly contaminated mHWS in Lubumbashi could be ascribed to the location of the mHWS (more frequent in non-patient related hospital areas) and the high proportion of mHWS containing chlorine granule remnants. In line with other field studies about drinking water analysis in LMIC, a chlorine neutralizer was not used [53, 71–73] and samples were processed within 4 h after sampling. The selection of culture media may have missed organisms thriving in nutrient-poor environments [34, 74] but reading of culture media after 48h did not reveal additional growth.

Relevance and generalizability

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study assessing microbiology quality of in-use mHWS deployed in HCF. The study is further original by the bacterial identification and counting beyond the limits of standard water analysis.

Given the potential biases (selection of mHWS, adding of chlorine granules), the proportion of highly contaminated mHWS might be higher than found. The hospitals were representative for urban settings, but higher proportions may be expected in HCF in rural areas and in unplanned urban populations which are underserved as to provision of water, sanitation, and hygiene [8, 43].

Conversely, the present study assessed nearly exclusively mHWS of the “bucket-with-plastic-tap-and-basin” design, which harbors several factors conducive to bacterial contamination and proliferation such as low flow rate, hand-touched tap, biofilm, and splashes from the waste-basin. More advanced design-type mHWS may be less prone to contamination.

Risk mitigation and outstanding issues

Among the numerous design types of mHWS, only a few were listed for use in HCF [16, 18]. The present findings therefore support the recommendation to prioritize alcohol-based hand rub in HCF, in particular in high-risk areas [20, 25]. Further, the use of mHWS in HCF should be as much as possible restricted to visitors and administrative areas.

Good maintenance and regular checks and repairs of broken or dysfunctional parts are recommended to assure well-functioning of the mHWS [12, 18, 19] and in turn reduce the risk of slow or interrupted water and biofilm expansion. The wastewater basin should be disposed if it is 80% full [19]. Regular cleaning of high touch surfaces is also recommended, but only one source gave concrete instructions (applying to a community-type of mHWS): daily cleaning of the outside of the reservoir, emptying the reservoir once weekly and clean it with clean water and a household disinfectant such as 1% chlorine [75]. Some parts of mHWS such as the internal tubes and taps are however not accessible for cleaning. Continuous supply of water and soap is vital but concrete instructions about refilling are not provided [18, 19, 75]. The practice of topping-up (i.e., refilling without emptying) should be avoided [42].

Design features that reduce the risk of bacterial contamination and growth include hands-free taps and soap-dispensing systems (elbow, forearm or foot-operated taps and self-closing taps) [22, 75], and the use of brass and copper taps [76]. Best practices for the use and management of liquid soap containers have been reviewed recently [42].

Chlorination of mHWS water is not recommended except as a last resort in emergency outbreak situations (e.g., filovirus outbreaks) [3, 22, 77]. Moreover, one third of mHWS reservoirs in this study showed dirt sand deposits, precluding efficacious chlorination. Other outstanding issues which were observed but not in-depth addressed in this study were the poor presence of soap (only half of mHWS, similar to what was found in other studies [12, 53, 71]) and the near total absence of towels for hand drying, both essential for proper handwashing.

Future research

Future research of mHWS should address the reduction of incoming and exiting contamination of mHWS. Technological innovations should be feasible and adapted to the local context including on-site manufacturing and repair and anticipate restricted access to safe water and end-user acceptability [19]. Safe levels of water contamination for handwashing in HCF should be developed, as well as field-adapted affordable point-of-care indicator tests [20, 67]. Research extending the mHWS should be done to study the potential role of caretakers in the uptake of MDR bacteria and their subsequent spread in the community, and how to prevent this.

Conclusion

Although conforming to the definition of a handwash station, the mHWS in the present study were highly contaminated with multidrug resistant bacteria and constitute reservoirs for healthcare-associated infections and potential spread towards the community. After the emergency of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is time now to review the place of mHWS in HCF and to consider measures to prevent their contamination.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our colleagues from National Institute of Biomedical Research, Provincial laboratory of Lubumbashi, as well as the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, for their contribution to data collection and microbial analysis.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, J.K., O.L., and J.J.; methodology, J.K., A.-S.H., and J.J.; validation, J.K., O.L., and J.J.; data collection, J.K., I.K., and J. M., data cleaning, J.K.; P.H., and A.-S.H.; data analysis, J.K., P.H., A.-S.H., and J.J.; writing—original draft preparation, J.K., O.L., and J.J.; writing—review and editing, J.K., A.-S.H., I.K., P.H., J.M., O.L., and J.J.; supervision, O.L., and J.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Belgian Directorate for Development Cooperation and Humanitarian Aid (DGD) through Framework Agreement between the Belgian DGD and the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Belgium. JK received a PhD fellowship from DGD.

Data availability

To access the research database, a Data Access Request Form needs to be sent to ITMresearchdataaccess@itg.be, contact point at the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium. All requests will be reviewed for approval by the Data Access Committee. Further information: https://www.itg.be/en/research/data-sharing-and-open-access.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium (1434/20) and the ethics committee of the School of Public Health of the University of Kinshasa, DRC (ESP/CE/208/2020). Written support for the study was granted by the General Health Office of the DRC Ministry of Health. All hospital directors and interviewees provided consent. Results presented were aggregated for all hospitals and no results of individual hospitals were presented.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Octavie Lunguya and Jan Jacobs have contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.MacLeod C, Braun L, Caruso BA, et al. Recommendations for hand hygiene in community settings: a scoping review of current international guidelines. BMJ Open. 2023. 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-068887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Guidelines on core components of infection prevention and control programmes at the national and acute health care facility level. 2016. https://www.who.int/teams/integrated-health-services/infection-prevention-control/core-components. Accessed 24 June 2024. [PubMed]

- 3.World Health Organization. WHO saves lives: clean your hands in the context of covid-19. 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/save-lives-clean-your-hands-in-the-context-of-covid-19. Accessed 24 June 2024.

- 4.Talic S, Shah S, Wild H, Gasevic D, Maharaj A, Ademi Z, et al. Effectiveness of public health measures in reducing the incidence of COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2 transmission, and COVID-19 mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2021. 10.1136/bmj-2021-068302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization/United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund. State of the World’s Hand Hygiene. 2021. https://www.unicef.org/reports/state-worlds-hand-hygiene. Accessed 24 June 2024.

- 6.Tomczyk S, Twyman A, de Kraker MEA, Coutinho Rehse AP, Tartari E, Toledo JP, et al. The first WHO global survey on infection prevention and control in health-care facilities. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:845–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. WHO recommendations to member states to improve hand hygiene practices to help prevent the transmission of the COVID-19 virus. 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/recommendations-to-member-states-to-improve-hand-hygiene-practices-to-help-prevent-the-transmission-of-the-covid-19-virus. Accessed 24 June 2024.

- 8.World Health Organization/ United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund. Progress on WASH in health care facilities 2000–2021: special focus on WASH and infection prevention and control (IPC). 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240058699. Accessed 24 June 2024.

- 9.Vujcic J. Strategies and challenges to handwashing promotion in humanitarian emergencies Key informant interviews with agency experts. 2014. https://globalhandwashing.org/resources/strategies-and-challenges-to-handwashing-promotion-in-emergencies/. Accessed 27 June 2024.

- 10.Bennett SD, Otieno R, Ayers TL, Odhiambo A, Faith SH, Quick R. Acceptability and use of portable drinking water and hand washing stations in health care facilities and their impact on patient hygiene practices, Western Kenya. PLoS ONE. 2015. 10.1371/journal.pone.0126916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tetteh-Quarcoo PB, Anim-Baidoo I, Attah SK, Abdul-Latif Baako B, Opintan JA, Minamor AA, et al. Microbial content of “bowl water” used for communal handwashing in preschools within Accra Metropolis. Ghana Ghana Int J Microbiol. 2016;2016:8–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rajasingham A, Leso M, Ombeki S, Ayers T, Quick R. Water treatment and handwashing practices in rural Kenyan health care facilities and households six years after the installation of portable water stations and hygiene training. J Water Health. 2018;16:263–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cronk R, Guo A, Folz C, Hynes P, Labat A, Liang K, et al. Environmental conditions in maternity wards: evidence from rural healthcare facilities in 14 low- and middle-income countries. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2021. 10.1016/j.ijheh.2020.113681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sreenivasan N, Gotestrand SA, Ombeki S, Oluoch G, Fischer TK, Quick R. Evaluation of the impact of a simple hand-washing and water-treatment intervention in rural health facilities on hygiene knowledge and reported behaviors of health workers and their clients, Nyanza Province, Kenya, 2008. Epidemiol Infect. 2015;143:873–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freedman M, Bennett SD, Rainey R, Otieno R, Quick R. Cost analysis of the implementation of portable handwashing and drinking water stations in rural Kenyan health facilities. J Water Sanit and Hyg Dev. 2017;7:659–64. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Humanitarian innovation fund. WASH in emergencies problem exploration report: Handwashing. 2016. https://www.elrha.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Handwashing-WASH-Problem-Exploration-Report.pdf. Accessed 25 June 2024.

- 17.WaterAid. Technical Guide for handwashing facilities in public places and buildings. 2020. https://washmatters.wateraid.org/publications/technical-guide-for-handwashing-facilities-in-public-places-and-buildings. Accessed 25 June 2024.

- 18.Coultas M, Iyer R. with Myers J. Handwashing compendium for low resource settings: a living document. 2021. https://globalhandwashing.org/resources/handwashing-compendium-for-low-resource-settings-a-living-document/. Accessed 27 June 2024.

- 19.Foundation of Netherlands Volunteers in Tanzania, Practical options for hand-washing stations: A guide for promoters and producers, technical paper. 2020. https://www.snv.org/library/practical-options-handwashing-stations-guide-promoters-and-producers. Accessed 27 June 2024.

- 20.World Health Organization. WHO guidelines on hand hygiene in healthcare : first global patient safety challenge clean care is safer care. 2009. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241597906. Accessed on 24 June 2024. [PubMed]

- 21.World Health Organization. Water, sanitation, hygiene, and waste management for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19: interim guidance. 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-IPC-WASH-2020.4. Accessed 24 June 2024.

- 22.United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund. Handwashing stations and supplies for the COVID-19 response. 2020. https://www.corecommitments.unicef.org/kp/handwashing-facility-factsheet-(final).pdf. Accessed 24 June 2024.

- 23.Verbyla ME, Pitol AK, Navab-Daneshmand T, Marks SJ, Julian TR. Safely managed hygiene: a risk-based assessment of handwashing water quality. Environ Sci Technol. 2019;53:2852–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety SCCS. The SCCS notes of guidance for the testing of cosmetic ingredients and their safety evaluation 12th revision. 2023. https://health.ec.europa.eu/publications/sccs-notes-guidance-testing-cosmetic-ingredients-and-their-safety-evaluation-12th-revision_en. Accessed 27 June 2024.

- 25.Lompo P, Heroes AS, Agbobli E, Kazienga A, Peeters M, Tinto H, et al. Growth of Gram-negative bacteria in antiseptics, disinfectants and hand hygiene products in two tertiary care hospitals in west Africa—A cross-sectional survey. Pathogens. 2023. 10.3390/pathogens12070917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacobs J, Hardy L, Semret M, Lunguya O, Phe T, Affolabi D, Yansouni C, Vandenberg O. Diagnostic bacteriology in district hospitals in sub-Saharan Africa: at the forefront of the Containment of Antimicrobial Resistance. Front Med. 2019. 10.3389/fmed.2019.00205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weather Atlas. Climate and monthly weather forecast Democratic Republic of Congo. 2024. https://www.weather-atlas.com/en/democratic-republic-of-congo-climate. Accessed 17 Oct 2024.

- 28.Centers for Disease Control. Best practices for environmental cleaning in healthcare facilities in resource-limited settings version 2. 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/healthcare-associated-infections/media/pdfs/environmental-cleaning-RLS-508.pdf. Accessed 26 June 2024.

- 29.Denis F, Ploy M, Martin C, Cattoir V. Acinetobacter. In: Bactériologie Médicale—Techniques Usuelles; Amsterdam:Elsevier; 2016. pp. 346–348.

- 30.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. M100, 33rd ed. 2023. http://em100.edaptivedocs.net/GetDoc.aspx?doc=CLSI M100 ED33:2023&scope=user. Accessed 25 June 2024.

- 31.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Analysis and presentation of cumulative antimicrobial susceptibility test data, M39, 5th ed. 2022. https://infostore.saiglobal.com/en-us/standards/clsi-m39-ed5-2022-1299841_saig_clsi_clsi_3143074/. Accessed 25 June 2024.

- 32.Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant Bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:268–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization. WHO Bacterial priority pathogens list. 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240093461. Accessed 24 June 2024.

- 34.Centers for Disease Control Reduce risk from water from plumbing to patients. 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/healthcare-associated-infections/php/toolkit/water-management.html. Accessed 24 June 2024.

- 35.VassarStats: Website for Statistical Computation. Lowry, Richard. Available at: http://vassarstats.net/. Accessed on 24 June 2024.

- 36.Sterk E. Filovirus haemorrhagic fever guideline Médecins Sans Frontières. 2008. https://www.nursingworld.org/globalassets/practiceandpolicy/work-environment/health--safety/medicins.pdf. Accessed 25 June 2024.

- 37.Kanamori H, Weber DJ, Rutala WA. Healthcare outbreaks associated with a water reservoir and infection prevention strategies. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:1423–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kizny Gordon AE, Mathers AJ, Cheong EYL, Gottlieb T, Kotay S, Walker AS, et al. The hospital water environment as a reservoir for carbapenem-resistant organisms causing hospital-acquired infections - A systematic review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64:1436–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Curran ET. Outbreak column 3: outbreaks of Pseudomonas spp. from hospital water. J Infect Prev. 2012;13:125–7. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weinbren MJ. The handwash station: friend or fiend? Hosp Infect J. 2018;100:159–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lompo P, Heroes AS, Agbobli E, Kühne V, Tinto H, Affolabi D, et al. Bacterial contamination of antiseptics, disinfectants and hand hygiene products in healthcare facilities in high-income countries: a scoping review. Hygiene. 2023;3:136–75. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lompo P, Agbobli E, Heroes AS, Van den Poel B, Kühne V, Kpossou CMG, et al. Bacterial contamination of antiseptics, disinfectants, and hand hygiene products used in healthcare settings in low- and middle-income countries—A systematic review. Hygiene. 2023;3:93–124. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moffa M, Guo W, Li T, Cronk R, Abebe LS, Bartram J. A systematic review of nosocomial waterborne infections in neonates and mothers. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2017;220:1199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anah MU, Udo JJ, Ochigbo SO, Abia-Bassey LN. Neonatal septicaemia in Calabar. Nigeria Trop Doct. 2008;38:126–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bottieau E, Mukendi D, Kalo JR, Mpanya A, Lutumba P, Barbé B, et al. Fatal Chromobacterium violaceum bacteraemia in rural Bandundu, Democratic Republic of the Congo. New Microbes New Infect. 2015;3:21–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stock I, Wiedemann B. Natural antibiotic susceptibility of Enterobacter amnigenus, Enterobacter cancerogenus, Enterobacter gergoviae and Enterobacter sakazakii strains. Clin Microbiol and Infect. 2002;8:564–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lucassen R, van Leuven N, Bockmühl D. A loophole in soap dispensers mediates contamination with Gram-negative bacteria. MicrobiologyOpen. 2023. 10.1002/mbo3.1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davin-Regli A, Lavigne JP, Pagès J-M. Enterobacter spp.: update on taxonomy, clinical aspects, and emerging antimicrobial resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019. 10.1128/CMR.00002-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zapka CA, Campbell EJ, Maxwell SL, Gerba CP, Dolan MJ, Arbogast JW, et al. Bacterial hand contamination and transfer after use of contaminated bulk-soap-refillable dispensers. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:2898–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chattman M, Maxwell SL, Gerba CP. Occurrence of heterotrophic and coliform bacteria in liquid hand soaps from bulk refillable dispensers in public Facilities. J Environ Health. 2011;73:26–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murphy JL, Kahler AM, Nansubug I, Nanyunj EM, Kaplan B, Jothikumar N, et al. Environmental survey of drinking water sources in Kampala, Uganda, during a typhoid fever outbreak. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2017. 10.1128/AEM.01706-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kundu A, Smith WA, Harvey D, Wuertz S. Drinking water safety: Role of hand hygiene, sanitation facility, and water system in semi-urban areas of India. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;99(4):889–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Potgieter N, Banda NT, Becker PJ, Traore-Hoffman AN. WASH infrastructure and practices in primary health care clinics in the rural Vhembe District municipality in South Africa. BMC Fam Pract. 2021. 10.1186/s12875-020-01346-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kadri SS, Adjemian J, Lai YL, Spaulding AB, Ricotta E, Rebecca Prevots D, et al. Difficult-to-treat resistance in gram-negative bacteremia at 173 US hospitals: retrospective cohort analysis of prevalence, predictors, and outcome of resistance to all first-line agents. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67:1803–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ombelet S, Kpossou G, Kotchare C, Agbobli E, Sogbo F, Massou F, et al. Blood culture surveillance in a secondary care hospital in Benin: epidemiology of bloodstream infection pathogens and antimicrobial resistance. BMC Infect Dis. 2022. 10.1186/s12879-022-07077-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Murray CJ, Ikuta KS, Sharara F, Swetschinski L, Robles Aguilar G, Gray A, et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022;399:629–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Venne DM, Hartley DM, Malchione MD, Koch M, Britto AY, Goodman JL. Review and analysis of the overlapping threats of carbapenem and polymyxin resistant E. coli and Klebsiella in Africa. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2023. 10.1186/s13756-023-01220-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yusuf E, Bax HI, Verkaik NJ, van Westreenen M. An update on eight “new” antibiotics against multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacteria. J Clin Med. 2021;10:1–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thaller MC, Borgianni L, Di Lallo G, Chong Y, Lee K, Dajcs J, et al. Metallo-β-lactamase production by Pseudomonas otitidis: a species-related trait. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:118–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mori T, Yoshizawa S, Yamada K, Sato T, Sasaki M, Nakamura Y, et al. Pseudomonas otitidis bacteremia in an immunocompromised patient with cellulitis: case report and literature review. BMC Infect Dis. 2023. 10.1186/s12879-023-08919-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ogunsola FT, Mehtar S. Challenges regarding the control of environmental sources of contamination in healthcare settings in low-and middle-income countries - a narrative review. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2020. 10.1186/s13756-020-00747-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Biswal M, Angrup A, Rajpoot S, Kaur R, Kaur K, Kaur H, et al. Hand hygiene compliance of patients’ family members in India: importance of educating the unofficial ‘fourth category’ of healthcare personnel. J Hosp Infect. 2020;104:425–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Buffet-Bataillon S, Rabier V, Bétrémieux P, Beuchée A, Bauer M, Pladys P, et al. Outbreak of Serratia marcescens in a neonatal intensive care unit: contaminated unmedicated liquid soap and risk factors. J Hospi Infect. 2009;72:17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sartor C, Jacomo V, Duvivier C, Tissot-Dupont H, Sambuc R, Drancourt M. Nosocomial Serratia marcescens infections associated with extrinsic contamination of a liquid nonmedicated soap. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2000;21:196–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stjärne Aspelund A, Sjöström K, Olsson Liljequist B, Mörgelin M, Melander E, Påhlman LI. Acetic acid as a decontamination method for sink drains in a nosocomial outbreak of metallo-β-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Hosp Infect. 2016;94:13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ling ML, How KB. Pseudomonas aeruginosa outbreak linked to sink drainage design. Healthc Infect. 2013;18:143–6. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kanamori H, Weber DJ, Rutala WA, Kanamori H. Healthcare outbreaks associated with a water reservoir and infection prevention strategies. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:1423–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hayward C, Ross KE, Brown MH, Whiley H. Water as a source of antimicrobial resistance and healthcare-associated infections. Pathogens. 2020. 10.3390/pathogens9080667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brown DG, Baublis J, Arbor A. Reservoirs of Pseudomonas in an intensive care unit for newborn infants: mechanisms of control. J Pediatr. 1977;90:453–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kotay SM, Donlan RM, Ganim C, Barry K, Christensen BE, Mathers AJ. Droplet- rather than aerosol-mediated dispersion is the primary mechanism of bacterial transmission from contaminated hand-washing sink traps. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2019. 10.1128/AEM.01997-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Davis W, Odhiambo A, Oremo J, Otieno R, Mwaki A, Rajasingham A, et al. Evaluation of a water and hygiene project in health-care facilities in Siaya county, Kenya, 2016. Am J Trop Med and Hyg. 2019;101:576–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gärtner N, Germann L, Wanyama K, Ouma H, Meierhofer R. Keeping water from kiosks clean: Strategies for reducing recontamination during transport and storage in Eastern Uganda. Water Res X. 2021. 10.1016/j.wroa.2020.100079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Davis W, Massa K, Kiberiti S, Mnzava H, Venczel L, Quick R. Evaluation of an inexpensive handwashing and water treatment program in rural health care facilities in three districts in Tanzania, 2017. Water. 2020. 10.3390/w12051289. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cervia JS, Girolamo A, Ortolano MB, McAlister. Role of Biofilm in Pseudomonasaeruginosa colonization and infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30:924–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Africa Center for Disease Control. Hand washing facility options for resource limited settings. 2020. https://africacdc.org/download/hand-washing-facility-options-for-resource-limited-settings/. Accessed 24 June 2024.

- 76.Dauvergne E, Mullié C. Brass alloys: copper-bottomed solutions against hospital-acquired infections? Antibiotics. 2021. 10.3390/antibiotics10030286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mehtar S, Bulabula AN, Nyandemoh H, Jambawai S. Deliberate exposure of humans to chlorine-the aftermath of Ebola in West Africa. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2016. 10.1186/s13756-016-0144-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

To access the research database, a Data Access Request Form needs to be sent to ITMresearchdataaccess@itg.be, contact point at the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium. All requests will be reviewed for approval by the Data Access Committee. Further information: https://www.itg.be/en/research/data-sharing-and-open-access.