Abstract

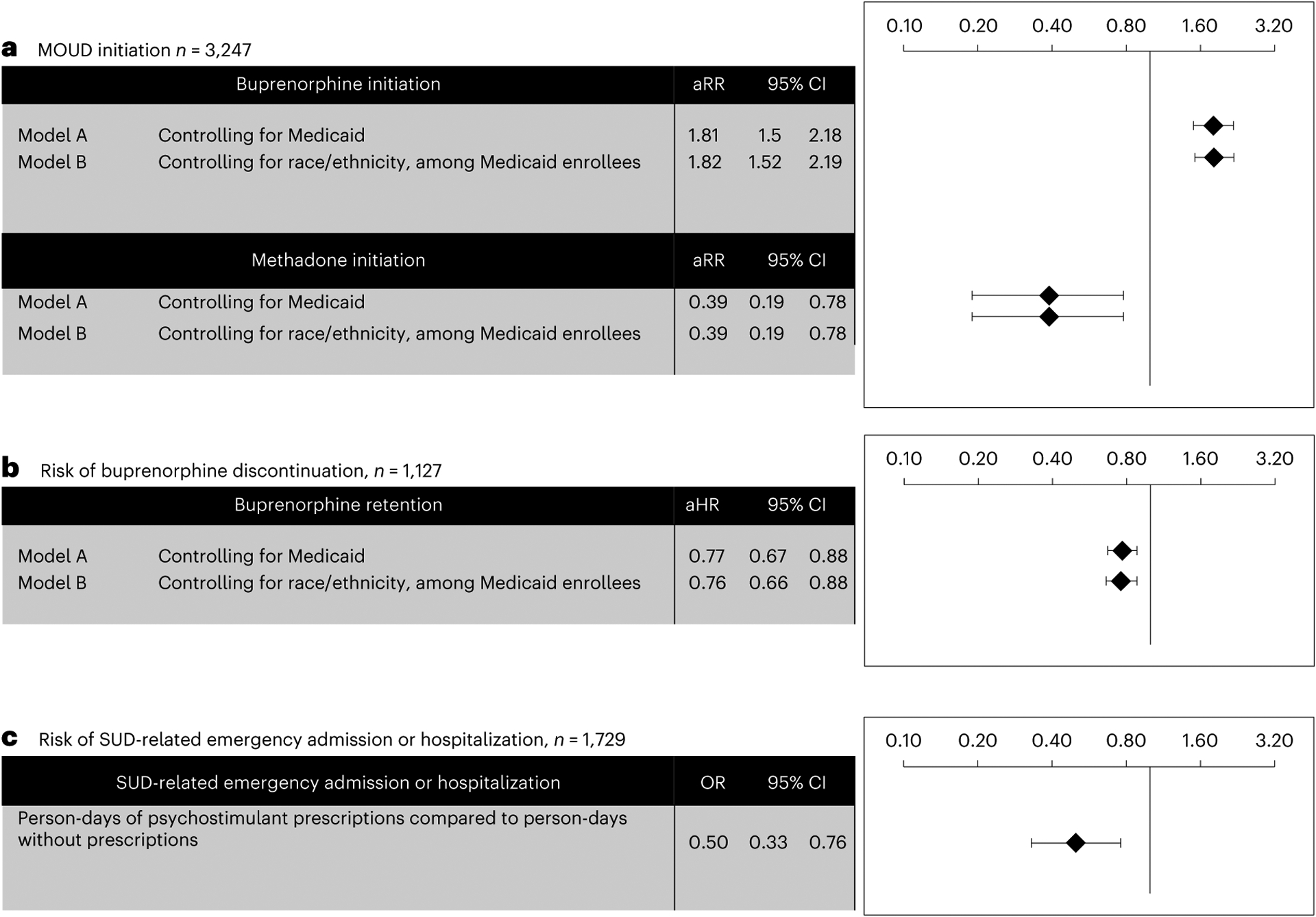

While attention deficit hyperactivity disorder is common among people with addiction, the risks and benefits of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder medication in pregnant people with opioid use disorder are poorly understood. Here, using US multistate administrative data, we examined 3,247 pregnant people initiating opioid use disorder treatment, of whom 5% received psychostimulants. Compared to peers not receiving psychostimulants, the psychostimulant cohort had greater buprenorphine (adjusted relative risk 1.81 (1.50–2.18)) but lower methadone initiation (adjusted relative risk 0.39 (0.19–0.78)). Among psychostimulant recipients who initiated buprenorphine, we observed lower buprenorphine discontinuation associated with the psychostimulant cohort compared to nonrecipients (adjusted hazard ratio 0.77 (0.67–0.88)). In within-person case-crossover analyses, person-days defined by psychostimulant fills were associated with fewer substance use disorder-related admissions compared to days without fills (odds ratio 0.50 (0.33–0.76)). Overall, our data suggest that psychostimulant use in pregnancy may be associated with increased buprenorphine initiation, decreased methadone initiation and improved buprenorphine retention. Decreased substance use disorder-related admissions were associated with person-days of psychostimulant receipt, although other risks of psychostimulant use in pregnancy warrant further investigation.

While the United States has experienced a substantial increase in the number of pregnant individuals with opioid use disorder (OUD)1–3, less than 50% receive medications to treat OUD (MOUD) such as buprenorphine4,5 and methadone6. In nonpregnant populations, data have shown that psychostimulant treatment of underlying attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) may decrease the burden of substance use disorder (SUD)-related acute care utilization7,8, boost outpatient SUD treatment engagement9 and improve treatment retention10,11.

In pregnancy, however, the risks and benefits of psychostimulant use are poorly understood12, and there are no formal guidelines for prescribing stimulants during pregnancy so far. It is thus important to evaluate the prevalence of psychostimulant prescriptions in pregnant people receiving buprenorphine and methadone. Furthermore, amid data showing that 60% and 54% of pregnant people discontinued buprenorphine and methadone, respectively, at 270 days6, it is important for us to understand whether the beneficial effects of psychostimulant exposure on OUD treatment retention in nonpregnant people holds true in pregnant cohorts. It is also important to assess downstream acute SUD-related event risks in pregnant people with OUD who are prescribed psychostimulants.

The OUD treatment initiation period is a particularly vulnerable time for poor outcomes, and how patients fare during treatment initiation is often a strong predictor of long-term treatment outcomes13,14. In this Article, we seek to address the gap in the literature by evaluating MOUD initiation (aim 1) and retention (aim 2) associated with psychostimulant use in pregnancy, as well as rates of SUD-related emergency admissions (aim 3) or hospitalizations associated with psychostimulant exposure in pregnancy.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Our sample consisted of 3,247 pregnant people with OUD initiating buprenorphine (37.4%), methadone (13.7%) or psychosocial treatment without MOUD (48.9%). The mean age was 27.7 (standard deviation (s.d.) ± 5.0) years. A total of 2,652 (81.7%) were enrolled in Medicaid. Among Medicaid enrollees, 85.5% were non-Hispanic white, 6.7% non-Hispanic Black, 1.1% Hispanic and 6.7% ‘other’ race/ethnicity. A total of 168 (5.2%) received prescription stimulants in the 6-month baseline period before OUD treatment initiation through 14 days following initiation. Co-occurring mood disorders and anxiety disorders were common, at 31.6% (n = 1,027) for mood disorder and 37.6% (n = 1,221) for anxiety disorders. There were no significant differences in co-occurring mood, anxiety, and psychotic disorder burden between those receiving and not receiving stimulants. In total, 30.6% (n = 995) and 44.8% (n = 1,453) had either co-occurring cannabis use disorder or tobacco dependence/use disorder, respectively, and 430 (13.2%) had co-occurring stimulant use disorder. There were no significant differences in co-occurring alcohol, stimulant and sedative use disorder burden between those receiving and not receiving stimulants.

Buprenorphine/methadone initiation (aim 1)

As shown in the unadjusted analyses in Table 1, buprenorphine receipt was more common among those receiving stimulants (129/168, 76.8%) than peers not receiving stimulants (1,085/3,079, 35.2%, P < 0.0001). Methadone receipt was overwhelmingly less common among people receiving psychostimulants (8/168, 4.8%) compared to peers not receiving stimulants (438/3,079, 14.2%). As shown in the adjusted analyses in Fig. 1a, psychostimulant receipt was associated with increased buprenorphine initiation (adjusted risk ratio (aRR) 1.81 (1.50–2.18)) and decreased methadone initiation (aRR 0.39 (0.19–0.78)), adjusting for age, insurance status, and co-occurring substance use and psychiatric conditions. Similar findings were observed in subgroup analyses of Medicaid enrollees that controlled for race or ethnicity. Full models are depicted in Supplementary Table 1.

Table 1 |.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of 3,247 pregnant people with OUD initiating medication to treat OUD

| All, initiating OUD treatment N = 3,247 (100) | People not receiving prescription psychostimulants N = 3,079 (94.8) | People receiving prescription psychostimulants N = 168 (5.2) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnant at time of OUD treatment initiation | 3,247 (100) | 3,079 (94.8) | 168 (5.2) | |

| Age at start of treatment (s.d.)a | 27.7 (5.0) | 27.7 (5.0) | 28.2 (5.6) | 0.30 |

| Age under 30 yearsb | 2,157 (66.4) | 2,055 (66.7) | 102 (60.7) | 0.11 |

| Medicaid (as opposed to commercial insurance)b | 2,652 (81.7) | 2,545 (82.7) | 107 (63.7) | <0.0001 |

| MOUDb | ||||

| Buprenorphine | 1,214 (37.4) | 1,085 (35.2) | 129 (76.8) | <0.0001 |

| Methadone | 446 (13.7) | 438 (14.2) | 8 (4.8) | 0.0005 |

| Psychosocial treatment without MOUD | 1,587 (48.9) | 1,556 (50.5) | 31 (18.5) | <0.0001 |

| Had SUD-related emergency room admissions and hospitalization after OUD treatment initiation through 360 days postpartumb | 1,729 (53.3) | 1,660 (53.9) | 69 (41.1) | 0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity (among Medicaid enrollees)b | 0.004 | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 2,221 (85.5) | 2,119 (85.1) | 102 (96.2) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 173 (6.7) | 172 (6.9) | 1 (0.9) | |

| Hispanic | 28 (1.1) | 26 (1.0) | 2 (1.9) | |

| ‘Other’ | 175 (6.7) | 174 (7.0) | 1 (0.9) | |

| Diagnoses in the 6 months preceding OUD treatment initiation | ||||

| Mood disorderb | 1,027 (31.6) | 973 (31.6) | 54 (32.1) | 0.88 |

| Anxiety disorderb | 1,221 (37.6) | 1,158 (37.6) | 63 (37.5) | 0.98 |

| Psychotic disorderb | 72 (2.2) | 70 (2.3) | 2 (1.2) | 0.35 |

| Alcohol use disorderb | 257 (7.9) | 242 (7.9) | 15 (8.9) | 0.62 |

| Stimulant (amphetamine use disorder, cocaine use disorder)b | 430 (13.2) | 409 (13.3) | 21 (12.5) | 0.77 |

| Sedative use disorderb | 121 (3.7) | 113 (3.7) | 8 (4.8) | 0.47 |

| Tobacco dependence/use disorderb | 1,453 (44.8) | 1,408 (45.7) | 45 (26.8) | <0.0001 |

| Cannabis dependence/use disorderb | 995 (30.6) | 962 (31.2) | 33 (19.6) | 0.002 |

Wilcoxon sum-rank test (nonparametric);

Chi-square test. All reported P values are two-sided.

Fig. 1 |. Differences in substance use disorder treatment outcomes in pregnant individuals with or without psychostimulant prescriptions.

a, Adjusted analyses (multivariable Poisson regression) illustrate the association between prescription psychostimulants and initiation of buprenorphine and methadone (aim 1), with full models in Supplementary Table 1. b, Adjusted analyses (multivariable Cox regression) illustrate the association between prescription psychostimulant receipt and risk of buprenorphine discontinuation (aim 2), with full models in Supplementary Table 2. c, Conditional logistic regression models illustrate the association between person-days of psychostimulant receipt and risk of SUD-related emergency admission or hospitalization (aim 3) For all models (a–c), data are presented with error bars reflecting 95% confidence intervals (CI) (mean ± 1.96 × standard error of the mean). aRR, adjusted risk ratio; aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; OR, odds ratio.

Buprenorphine discontinuation (aim 2)

In unadjusted analyses, the median time to buprenorphine discontinuation was 177 days for people not receiving psychostimulants, versus 239 days for those receiving psychostimulants (P < 0.0001). With regard to buprenorphine retention, whereas 55.5% (86/155) of people receiving stimulants had 180-day retention in buprenorphine, this figure was 41.7% (394/920) in people not receiving stimulants (P = 0.001). As depicted in the adjusted analyses in Fig. 1b, we conducted Cox proportional hazards regression models to further examine the relationship between psychostimulant use and buprenorphine retention, adjusting for age, insurance status, and co-occurring substance use and psychiatric conditions; we found that treatment episodes marked by stimulant receipt were associated with lower buprenorphine discontinuation relative to episodes without stimulant use (adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) 0.77 (0.67–0.88)). We observed similar findings in models controlling for race or ethnicity among Medicaid enrollees. Full models are depicted in Supplementary Table 2. We conducted sensitivity analyses specifying buprenorphine retention with episode definitions using 14-, 45- and 60-day gaps between episodes; these models did not differ from parent analyses (Supplementary Table 2).

SUD-related admissions (aim 3)

As depicted in Table 1, SUD-related emergency room admissions or hospitalizations were common in univariate analyses, at 53.3% across the overall sample, with increased burden among people who did not receive stimulants (n = 11,660, 53.9%) relative to those who received stimulants (n = 69, 41.1%, P = 0.001). As shown in Fig. 1c, conditional logistic regression revealed that person-days of prescription psychostimulant exposure was associated with a lower overall risk of SUD-related admission and hospitalization between OUD treatment initiation and 360 days postpartum (odds ratio (OR) 0.50 (0.33–0.76)).

Discussion

Active untreated OUD in pregnancy is associated with multiple obstetric and neonatal adverse outcomes1, and studies routinely show that treatment with buprenorphine and methadone reduces fetal exposure to multiple illicit substances and improves pregnancy outcomes15. This study shows that psychostimulant receipt is associated with increased buprenorphine initiation in contrast to decreased methadone initiation in pregnancy. While we cannot infer causation from observational data, these findings are intriguing; despite low misuse potential of psychostimulants in nonpregnant people receiving methadone16,17, epidemiologic studies18,19 and patient accounts20 have raised concern about methadone treatment programs prohibiting patient access to psychostimulant medication. Studies in nonpregnant populations have shown that people receiving methadone may have greater ADHD symptom severity compared to peers on buprenorphine21, yet our data suggest they may be less likely to receive ADHD treatment. Future studies should consider examining how the structure of surveillance in methadone treatment programs may be contributing to the under-treatment of ADHD.

In addition, our data show that use of prescribed psychostimulants in pregnancy is associated with improved buprenorphine retention, thus increasing the protective effect of buprenorphine against OUD-related morbidity and mortality22, and SUD-related admissions23. Indeed, our data showed that prescription psychostimulant exposure was associated with a modestly lower overall risk of admission and hospitalization with no apparent differences between those of varying race and ethnicities. This is particularly important given the magnified racial disparities with regard to morbidity, mortality and treatment outcomes of both OUD and pregnancy in the United States24,25.

Ultimately, this study highlights important potential benefits to prescription stimulant treatment during pregnancy in people with OUD. While stimulant exposure in pregnancy appears generally safe, findings are inconsistent and frequently limited to substance use or misuse as opposed to prescribed use. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently completed a study that warned of possible increased risk of omphalocele, gastroschisis and transverse limb deficiency after early pregnancy exposure to psychostimulants in utero26.There are also multiple conflicting studies regarding risk of cardiac malformations after in utero exposure to methylphenidate, specifically27–30. More recent studies have been reassuring, including a 2023 Danish population-based cohort study that detected no neurodevelopmental or growth differences between children exposed to ADHD medications in utero versus those whose parent discontinued their ADHD medication before pregnancy31 as well as a 2023 preliminary analysis of the Massachusetts General Hospital National Pregnancy Registry for Psychiatric Medications that showed no increased risk of major malformation in infants exposed in utero to the most commonly prescribed ADHD medications32. A 2024 analysis of US administrative claims data suggested that prescription amphetamine and methylphenidate exposure in a general pregnant sample did not correlate meaningfully with increased risk of childhood neurodevelopmental disorders in multivariable analyses that adjusted for confounding33. Prescribed psychostimulant use during pregnancy has also been associated with increased risk of preeclampsia and preterm labor, though authors noted that absolute risk was still quite small and warned against discontinuing ADHD treatment during pregnancy on the basis of the study34. Therefore, the decision to treat warrants consideration of individual risks and shared decision-making with the patient. Unfortunately, the 2023 clinical practice guidelines for mental health management during and after pregnancy published by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologist does not include recommendations for the treatment of ADHD35. Those making these decisions with patients would benefit from future studies regarding concomitant OUD and ADHD in pregnancy that assist in generating formal guidelines for treatment and perhaps identifying pregnancy and birth outcomes relative to specific treatments.

There are a number of limitations to consider in this study. First, this study was underpowered to evaluate methadone-associated retention, outcomes by trimester, or opioid poisonings specifically. While our study’s finding of decreased net SUD-related emergency admission and hospitalizations associated with psychostimulant use is supported by findings in the nonpregnant population7–9, analyses by Mintz et al.10 have suggested an increased risk of opioid overdose associated with prescription psychostimulant exposure, albeit this was counteracted by an increased retention in buprenorphine treatment, which is protective against opioid overdose. Second, there are limitations to generalizability. This analysis was limited to a very specific subpopulation of pregnant people with OUD initiating treatment. Furthermore, our cohort was required to have 6 months of continuous insurance coverage before initiating treatment (excluding 30% of MarketScan’s treatment episodes), which cannot be generalized to people who are uninsured or incarcerated, or people receiving methadone via self-pay. Many patients with ADHD are unable to receive treatment, and so stimulant prescription during pregnancy is probably a marker for a resource-rich environment that may also increase retention in OUD treatment36,37. The underrepresentation of people from minoritized and historically oppressed racial and ethnic backgrounds in our stimulant-receiving cohort further illustrates that the protective effects of psychostimulants on retention may be confounded by the social privilege that stimulant receipt is associated with. As such, these results should not be interpreted as a call for stimulant initiation in all pregnant people with OUD.

Third, this study also was not powered to evaluate the reproductive safety profile of prescription psychostimulants during pregnancy in this population. There continues to be an aforementioned lack of comprehensive data on the reproductive safety profiles of prescription psychostimulants in pregnant people, especially those with OUD12. This study does not have data on delivery and birth outcomes, which is critical for assessing risks and benefits of stimulant treatment in pregnancy for this at-risk population. Fourth, we suspect undercounting of billable ADHD diagnoses in our data, which limits the utility of ADHD diagnoses as a requirement for inclusion in the cohort, as is the case for other studies on psychostimulants using administrative claims10. Some patients with ADHD may also see a psychiatrist for refills so infrequently38,39 that their doctors’ visits (and ADHD diagnoses) are not captured in the 6-month baseline period for covariate assessment. Furthermore, this analysis cannot provide insight into the effectiveness of prescription stimulants for treating specific ADHD symptoms (that is, impulsivity associated with ADHD), nor does this paper shed light on whether treatment outcomes may differ by the indication for the prescribed stimulant. Finally, while case-crossover designs can mitigate selection bias (by comparing person-days of stimulant exposure and SUD-related admissions within the same person and mitigating bias resulting from recruitment of different case and control subjects in conventional observational designs), residual time-varying confounding cannot be ruled out.

For future studies, randomized controlled trials should be considered to clarify whether the differences shown in these analyses were due to ADHD medications as opposed to differences between people taking versus not taking psychostimulants (that is, whether people with greater severity of SUDs may be less likely to receive stimulants). We urgently need up-to-date data, as the present dataset ends in 2016, preceding the ongoing overdose crisis characterized by escalating use of potency-enhancing synthetics (that is, fentanyl). Future analyses should also evaluate outcomes by trimester, which may help us understand how stimulant treatment’s effects on MOUD outcomes may be influenced by pregnancy timing.

Conclusions

We observed an association between stimulant use before OUD treatment initiation in pregnancy and improved buprenorphine treatment retention as well as decreased SUD-related emergency room admissions and hospitalizations in the period spanning treatment initiation during pregnancy and 360 days postpartum. These findings highlight important potential benefits of pharmacologically treating ADHD with stimulants in pregnant people with concomitant OUD and ADHD. Future studies are warranted to clarify pregnancy and neonatal outcomes when treating this specific population to further inform share decision-making.

Methods

Study design and data source

We used data from the Merative MarketScan Commercial and Multi-State Medicaid Databases (2006–2016), which include comprehensive longitudinal clinical, enrollment and pharmacy data for all clinical encounters and filled prescriptions in the United States, as previously described40. Our data were available from 1 January 2006 to 31 December 2016. Analyses were conducted from 15 July 2022 through 21 December 2023. The Washington University Institutional Review Board found this study exempt from review because no identifiable private data were used.

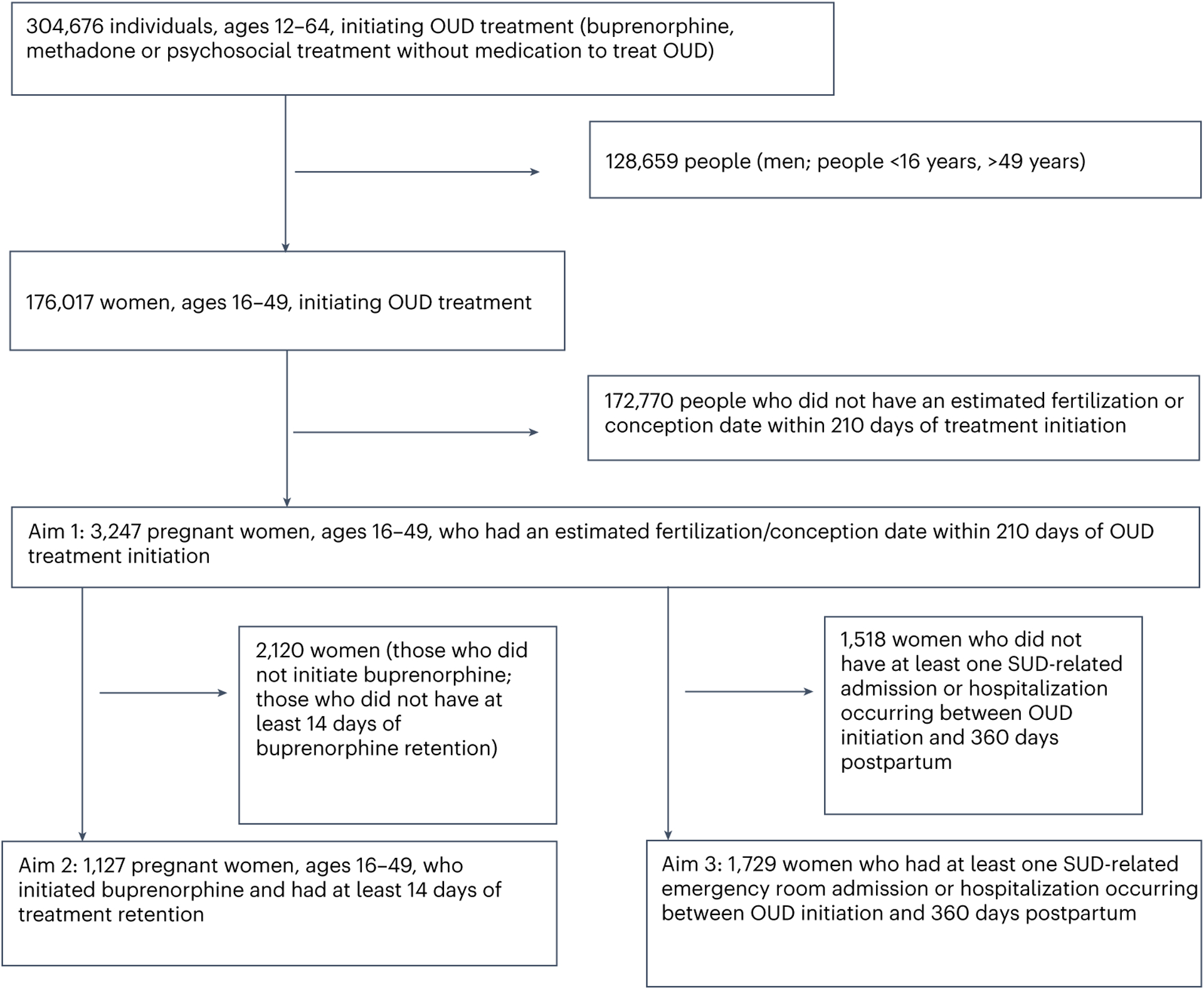

Participants and observation window

Our cohorts were derived from 304,676 people initiating treatment for OUD (buprenorphine, methadone or psychosocial treatment without MOUD). All were identified as enrolled in Medicaid or commercial insurance in the United States, having a diagnosis of OUD based on ICD (International Classification of Diseases)-9/10 codes, and a 6-month minimum of pharmacy and medical coverage before the start of OUD treatment, representing a standard baseline period for covariate assessment41. We excluded 128,659 people (men and individuals <16 years or >49 years), deriving a sample of 176,017 women, ages 16–49 initiating treatment. We included full inclusion and exclusion criteria in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2 |. Diagram of sample set inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Illustration of the derivation of the analytic sample.

For aim 1, we excluded 172,770 people who did not have an estimated fertilization or conception date within 210 days of OUD treatment initiation to derive a cohort of 3,247 pregnant individuals for our analysis of the association between psychostimulant exposure and treatment initiation (buprenorphine versus methadone versus psychosocial treatment without MOUD). We identified pregnancy status by computing conception dates retrospectively from delivery (Supplementary Protocols 1)42,43.

For aim 2 (Supplementary Protocols 2), we examined retention in buprenorphine treatment, defined as days elapsed between date of first buprenorphine script (date of initiation) until last script of a treatment episode, using 30 days as the threshold for episode discontinuity, limiting our analyses to 1,127 pregnant people who initiated buprenorphine and had at least 14 days of treatment retention (as our window for ascertaining stimulant receipt stretched from 6 months before treatment initiation to 14 days after treatment start). As few patients receiving psychostimulants initiated treatment on methadone, our analyses were underpowered to evaluate methadone retention.

For aim 3 (Supplementary Protocols 3), we employed a case-crossover design to evaluate differences in rates of SUD-related emergency admission and hospitalization by stimulant receipt status. Our sample for this aim comprised 1,729 pregnant people starting treatment (buprenorphine, methadone and psychosocial treatment without MOUD) who had at least one SUD-related emergency admission or hospitalization between the date of OUD treatment initiation and 360 days postpartum, excluding 1,518 people who did not have at least one admission.

Variables

For aims 1 and 2, the primary predictor variable was a binary variable of prescription psychostimulant receipt (yes/no) between 6 months preceding OUD treatment initiation to the 14 days following OUD treatment initiation; the outcome variable for the first aim was the initiation of an episode of buprenorphine, methadone or psychosocial treatment without MOUD. Naltrexone (oral, long-acting) was not included as it does not have a US Food and Drug Administration indication for treatment of OUD during pregnancy44. The ascertainment of MOUD from pharmacy and procedure codes in the MarketScan data has been previously described6. As shown in Supplementary Protocols 4, an episode of OUD treatment was defined as a continuous series of MOUD possession until a gap in MOUD receipt occurred. We ascertained prescription psychostimulants using generic names in the MarketScan drug files, encompassing amphetamine salts, methylphenidate, dexmethylphenidate and lisdexamfetamine.

For the second aim, the outcome was the exposure-time variable of days until buprenorphine discontinuation. We defined retention in treatment as the number of days of the first treatment claim for buprenorphine and the date on which the last claim occurred, with each buprenorphine episode defined by continuous receipt, with no lapse in buprenorphine possession exceeding more than 30 days45. Covariates for aims 1 and 2 included age at start of OUD treatment (in years), Medicaid versus commercial insurance, and race/ethnicity (among people with Medicaid, as race/ethnicity is not provided in the commercial insurance claims). We also ascertained covariates for co-occurring stimulant use disorder and other SUDs, mood disorder (depression or bipolar disorder), anxiety disorders (composite of post-traumatic stress disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, social anxiety and anxiety disorder unspecified) and psychotic disorders (schizoaffective disorder and schizophrenia) using ICD-9/10 diagnostic codes during the 6 months preceding OUD treatment initiation.

For aim 3, the primary predictor variable was person-days of prescription psychostimulant exposure; the outcome variable was the binary variable of SUD-related emergency admission or hospitalizations, a measure previously used as a function of SUD burden, in the observation window spanning treatment initiation through 360 days postpartum7. We selected 360 days postpartum given past data showing increased risk of SUD-related admissions (that is, nonfatal overdose) during this period1. We defined an individual’s index admission as the first admission or hospitalization observed in the data upon initiation of OUD treatment; this was operationalized using ICD-9/10 codes encompassing any non-tobacco-related SUD, primary or otherwise, including accidents, poisonings and overdoses2. Participants were permitted to have multiple admissions as long as they fell within the observation window.

Statistical analyses

We first computed descriptive statistics among people receiving and not receiving prescription psychostimulants by demographic and clinical characteristics, employing chi-square tests for categorical variables and Wilcoxon sum-rank tests for numeric variables. We used multivariable Poisson regression models to evaluate the association of stimulant receipt with MOUD initiation (aim 1). Next, we computed buprenorphine retention as a function of psychostimulant use (defined as psychostimulant receipt during the 6-month baseline period through the first 14 days of buprenorphine treatment) using multivariable cox regression (aim 2). Covariates for the models of aims 1 and 2 included insurance (or self-reported race, only available among Medicaid enrollees), age at start of treatment, and comorbidities by the presence of ICD-9/10 diagnostic codes for mood, anxiety, psychotic or co-occurring SUDs (cocaine, methamphetamine, alcohol and sedative). Because there is heterogeneity in thresholds for buprenorphine discontinuation used by past studies46, sensitivity analyses were conducted that specified discontinuation with 14-day, 45-day and 60-day gaps, as opposed to 30-day gaps (Supplementary Protocols 4)

Finally, we used the case-crossover approach described by Allison and Christakis47, evaluating the relationship between person-days of stimulant exposure and person-days characterized by admission or hospitalization (aim 3), among the subsample of pregnant people initiating OUD treatment with at least one SUD-related admission/hospitalization. Secular confounding was accounted for via restricted cubic splines47–49. This approach is illustrated in detail in Supplementary Protocols 3 and described in other past analyses of this cohort23,50,51. All reported P values were two-sided, with a significance level of 0.05. All analyses were conducted via SAS version 9.4.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contributions of the following individuals: L. Bierut (Washington University), T. Fidalgo (Federal University of Sao Paulo) and V. Tardelli (University of Toronto) for their thoughtful insights that contributed to this manuscript; J. Goldbach and K. Bucholz of the Transdisciplinary Training in Addictions Research (TranSTAR) T32 Program of Washington University for obtaining funding to support effort for personnel (K.Y.X.); P. Cavazos-Rehg and L. Bierut of the NIDA K12 Program of Washington University for obtaining funding to support effort for personnel (K.Y.X.); M. Keller, J. Sahrmann and D. Stwalley from the Center for Administrative Data Research (CADR) of Washington University for technical support of the MarketScan Databases. Merative and MarketScan are trademarks of Merative Corporation in the United States, other countries or both. This project was funded by R21 DA044744 (K.Y.X., principal investigator (PI): R.A.G./L. Bierut). Effort for some personnel was supported by grants T32 DA015035 (K.Y.X., PI: K. Bucholz, J. Goldbach) and K12 DA041449 (KYX, PI: L. Bierut, P. Cavazos-Rehg), St. Louis University Research Institute Fellowship (R.A.G.) and K23 DA053507 (C.E.M.), but these grants did not fund the analyses of the Merative MarketScan Multi-State Medicaid Database data performed by K.Y.X. C.A.D.R. is supported in part by the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences via grants UL1 TR002345 (from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health).

Competing interests

R.A.G. reported receiving grants from the NIH and Arnold Ventures LLC during the conduct of the study, consulting for Janssen Pharmaceuticals and receiving personal fees for grant reviews from the NIH outside the submitted work. These funding sources had no influence on the design and analysis of the present study. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Code availability

Relevant code is available on written reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-024-00270-w.

Data availability

The MarketScan data are proprietary and can be accessed via a request to Merative (marketscan.support@merative.com). No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Schiff DM et al. Fatal and nonfatal overdose among pregnant and postpartum women in Massachusetts. Obstet. Gynecol 132, 466–474 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayatbakhsh MR et al. Illicit drug use before and during pregnancy at a tertiary maternity hospital 2000–2006. Drug Alcohol Rev. 30, 181–187 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schiff DM et al. Perinatal opioid use disorder research, race, and racism: a scoping review Pediatrics 10.1542/peds.2021-052368 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saia KA et al. Caring for pregnant women with opioid use disorder in the USA: expanding and improving treatment. Curr. Obstet. Gynecol 5, 257–263 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schiff DM et al. Assessment of racial and ethnic disparities in the use of medication to treat opioid use disorder among pregnant women in massachusetts. JAMA Netw. Open 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.5734 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu KY et al. Initiation and treatment discontinuation of medications for opioid use disorder in pregnant compared with nonpregnant people. Obstet Gynecol. 141, 845–853 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quinn PD et al. ADHD medication and substance-related problems. Am. J. Psychiatry 174, 877–885 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heikkinen M et al. Association of pharmacological treatments and hospitalization and death in individuals with amphetamine use disorders in a Swedish Nationwide Cohort of 13 965 patients. JAMA Psychiatry 80, 31–39 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kast KA, Rao V & Wilens TE Pharmacotherapy for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and retention in outpatient substance use disorder treatment: a retrospective cohort study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 82, 20m13598 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mintz CM et al. Analysis of stimulant prescriptions and drug-related poisoning risk among persons receiving buprenorphine treatment for opioid use disorder. JAMA Netw. Open 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.11634 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tardelli V et al. Prescription amphetamines in people with opioid use disorder and co-occurring psychostimulant use disorder initiating buprenorphine: an analysis of treatment retention and overdose risk. BMJ Ment. Health 26, e300728 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freeman MP ADHD and pregnancy. Am. J. Psychiatry 171, 723–728 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams AR, Nunes EV, Bisaga A, Levin FR & Olfson M Development of a Cascade of Care for responding to the opioid epidemic. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 45, 1–10 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whitley SD et al. Factors associated with complicated buprenorphine inductions. J. Subst. Abuse Treat 39, 51–57 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suarez EA et al. Buprenorphine versus methadone for opioid use disorder in pregnancy. New Engl. J. Med 387, 2033–2044 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levin FR et al. Treatment of methadone-maintained patients with adult ADHD: double-blind comparison of methylphenidate, bupropion and placebo. Drug Alcohol Depend. 81, 137–148 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cassidy TA et al. Nonmedical use of prescription ADHD stimulant medications among adults in a substance abuse treatment population: early findings from the NAVIPPRO surveillance system. J. Atten. Disord 19, 275–283 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bramness JG & Kornor H Benzodiazepine prescription for patients in opioid maintenance treatment in Norway. Drug Alcohol Depend. 90, 203–209 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abel KF, Bramness JG & Martinsen EW Stimulant medication for ADHD in opioid maintenance treatment. J. Dual Diagn 10, 32–38 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moraff C Forced to quit methadone because of his Adderall prescription. Filter Magazine https://filtermag.org/quit-methadone-adderall/ (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lugoboni F et al. Co-occurring attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms in adults affected by heroin dependence: patients characteristics and treatment needs. Psychiatry Res. 250, 210–216 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krans EE et al. Outcomes associated with the use of medications for opioid use disorder during pregnancy. Addiction 116, 3504–3514 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu KY, Mintz CM, Presnall N, Bierut LJ & Grucza RA Association of bupropion, naltrexone, and opioid agonist treatment with stimulant-related admissions among people with opioid use disorder: a case-crossover analysis. J. Clin. Psychiatry 10.4088/JCP.21m14112 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin CE et al. Disparities in opioid use disorder-related hospital use among postpartum Virginia Medicaid members. J. Subst. Use Addict. Treat 145, 208935 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu KY et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in buprenorphine and methadone utilization among reproductive-age women with opioid use disorder: an analysis of multi-state medicaid claims in the USA (2011–2016). J. Gen. Intern. Med 38, 3499–3508 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson KN et al. ADHD medication use during pregnancy and risk for selected birth defects: National Birth Defects Prevention Study, 1998–2011. J. Atten. Disord 24, 479–489 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diav-Citrin O et al. Methylphenidate in pregnancy: a multicenter, prospective, comparative, observational study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 77, 1176–1181 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dideriksen D, Pottegård A, Hallas J, Aagaard L & Damkier P First trimester exposure to methylphenidate. Basic Clin. Pharmacol 112, 73–76 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huybrechts KF et al. Association between methylphenidate and amphetamine use in pregnancy and risk of congenital malformations a cohort study from the International Pregnancy Safety Study Consortium. JAMA Psychiatry 75, 167–175 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kolding L et al. Associations between ADHD medication use in pregnancy and severe malformations based on prenatal and postnatal diagnoses: a Danish registry-based study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 82, 20m13458 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Madsen KB et al. In utero exposure to ADHD medication and long-term offspring outcomes. Mol. Psychiatry 28, 1739–1746 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szpunar MJ et al. Risk of major malformations in infants after first-trimester exposure to stimulants results from the Massachusetts General Hospital national pregnancy registry for psychiatric medications. J. Clin. Psychopharm 43, 326–332 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suarez EA et al. Prescription stimulant use during pregnancy and risk of neurodevelopmental disorders in children. JAMA Psychiatry 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.5073 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cohen JM et al. Placental complications associated with psychostimulant use in pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol 130, 1192–1201 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Treatment and management of mental health conditions during pregnancy and postpartum: ACOG Clinical Practice Guideline No. 5. Obstet Gynecol. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000005202 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Friedman J et al. Assessment of racial/ethnic and income disparities in the prescription of opioids and other controlled medications in California. JAMA Intern. Med 179, 469–476 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang KG, Flores MW, Carson NJ & Cook BL Racial and ethnic disparities in childhood ADHD treatment access and utilization: results from a national study. Psychiatr. Serv 73, 1338–1345 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brinkman WB et al. Relationship between attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder care and medication continuity. J. Am. Acad. Child. Psychiatry 55, 289–294 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perwien A, Hall J, Swensen A & Swindle R Stimulant treatment patterns and compliance in children and adults with newly treated attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Manag. Care Pharm 10, 122–129 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu KY et al. Association between benzodiazepine or Z-drug prescriptions and drug-related poisonings among patients receiving buprenorphine maintenance: a case-crossover analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 178, 651–659 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brunelli SM et al. Estimation using all available covariate information versus a fixed look-back window for dichotomous covariates. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf 22, 542–550 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bello JK, Salas J & Grucza R Preconception health service provision among women with and without substance use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109194 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Palmsten K et al. Harnessing the Medicaid Analytic eXtract (MAX) to evaluate medications in pregnancy: design considerations. PLoS ONE 8, e67405 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jones HE, Chisolm MS, Jansson LM & Terplan M Naltrexone in the treatment of opioid-dependent pregnant women: common ground. Addiction 108, 255–256 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meinhofer A, Williams AR, Johnson P, Schackman BR & Bao Y Prescribing decisions at buprenorphine treatment initiation: do they matter for treatment discontinuation and adverse opioid-related events? J. Subst. Abuse Treat 105, 37–43 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dong HR, Stringfellow EJ, Russell WA, Bearnot B & Jalali MS Impact of alternative ways to operationalize buprenorphine treatment duration on understanding continuity of care for opioid use disorder. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict 10.1007/s11469-022-00985-w (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Allison P & Christakis N Fixed-effects methods for the analysis of nonrepeated events. Sociol.Methodol 36, 155–172 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mittleman MA & Mostofsky E Exchangeability in the case-crossover design. Int. J. Epidemiol 43, 1645–1655 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hallas J, Pottegard A, Wang S, Schneeweiss S & Gagne JJ Persistent user bias in case-crossover studies in pharmacoepidemiology. Am. J. Epidemiol 184, 761–769 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ellis MS et al. Gabapentin use among individuals initiating buprenorphine treatment for opioid use disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.3145 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu KY et al. Association of opioid use disorder treatment with alcohol-related acute events. JAMA Netw. Open 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0061 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The MarketScan data are proprietary and can be accessed via a request to Merative (marketscan.support@merative.com). No additional data are available.