Abstract

Previous research has focused on the possibility of cervical dysfunction in migraine patients, similar to what is observed in patients with tension-type headaches. However, there is no evidence concerning the physical function of other body regions, even though lower levels of physical activity have been reported among migraine patients. The aim of this study was to compare cervical and extra-cervical range of motion, muscular strength, and endurance, as well as overall levels of physical activity, between patients with chronic migraine (CM) and asymptomatic participants. The secondary objective included the analysis of associations between CM-related disability and various physical and psychological variables. A total of 90 participants were included in this cross-sectional study: 30 asymptomatic participants (AG) and 60 patients with CM. Cervical and lumbar range of motion, strength and endurance, as well as handgrip strength were measured. Headache-related disability, kinesiophobia, pain behaviors, physical activity level and headache frequency were assessed through a self-report. Lower values were found in CM vs AG for cervical and lumbar ranges of motion (p < 0.05; effect sizes ranging from 0.57 to 1.44). Also, for neck extension strength (p = 0.013; d = − 0.66), lumbar strength (p < 0.001; d = − 1.91) and handgrip strength (p < 0.001; d = − 0.98), neck endurance (p < 0.001; d = − 1.81) and lumbar endurance (p < 0.001; d = − 2.11). Significant differences were found for physical activity levels (p = 0.01; d = − 0.85) and kinesiophobia (p < 0.001; d = − 0.93) between CM and AG. Headache-related disability was strongly associated with headache frequency, activity avoidance, and rest, which together explained 41% of the variance. The main findings of this study suggest that patients with CM have a generalized fitness deficit and not specifically cervical dysfunction. These findings support the hypothesis that migraine patients have not only neck-related issues but also general body conditions.

Keywords: Chronic migraine, Cervical region, Physical activity, Physical function, Migraine related disability

Subject terms: Neurological disorders, Pain

Introduction

Migraine is a complex and multifactorial neurological disorder1 that can present as episodic or chronic, depending on the frequency of the signs and symptoms2.

Epidemiologically, migraine is one of the most disabling disorders worldwide3. The prevalence of CM is estimated to be between 1% and 2.2% of the general population4,5, and it has been reported that 3.1% of patients with EM might progress to CM6.

Patients with migraine might experience neck discomfort and stiffness during the various phases of the migraine attack7. Recent evidence based on a meta-analytical analysis indicates that neck pain is a highly prevalent symptom in patients with CM8 and has been reported as an even more prevalent symptom than nausea9. These and other findings suggest that factors associated with cervical disability should be considered in the prevention and treatment of migraine and suggest the need for further research10.

One of the most extensively studied aspects of the cervical region has been range of motion deficits. The results of these studies confirm that patients with CM and EM present decreased cervical range of motion compared with the asymptomatic population11,12. The data obtained for neck range of motion in patients with migraine were 59.3° extension, 44.5° left lateral flexion and 60.8° right rotation11, also reduced flexion rotation test mobility and reduced velocity of neck movements12. It has also been observed that limitations in range of motion were related to migraine frequency and disability12.

Another cervical function characteristic found to be altered in patients with migraine is the strength and endurance of the cervical musculature13–15. The flexor endurance was found to be a 25% reduced compared to controls13. Regarding strength, a reduction of 4.4 N/kg was observed in cervical extension force in patients with migraine compared to asymptomatic participants14. This strength deficit has been associated with cutaneous allodynia15 and migraine frequency14. Also, significantly greater coactivation of antagonist muscles (splenius capitis muscle) was found among EM and CM compared to controls14.

Although the findings on cervical function disorders in migraine are important, these studies have a significant limitation in the assessment of strength and range of motion was evaluated only in the cervical region, which questions the specificity of the results, especially considering that recent evidence reports that patients with migraine have lower levels of physical activity than the asymptomatic population16. Indeed, lower cardiovascular fitness levels had higher long-term risk of developing migraine17. These findings support our hypothesis that deficits in physical variables such as strength and range of motion occur at a general level and not only in the cervical region.

In patients with migraine, avoidance of physical activity has been reported as a behavioral response driven by cognitive factors, such as fear of exacerbating headaches18. This avoidance is further influenced by anxiety18 and fear of movement12,19, both of which are closely linked to a reduction in physical activity and limited movement of the cervical region and head.

These findings suggest two hypotheses: (1) Migraine patients exhibit general, not localized, functional deficits in strength and range of motion, linked to reduced physical activity; and (2) Migraine-related disability correlates with functional deficits, low physical activity, and psychological factors. This study aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of migraine patients, potentially influencing treatment strategies. Unlike previous cervical-focused research, it employs a thorough evaluation of overall physical condition. The primary objective is to compare cervical region strength and range of motion with other areas in CM patients and asymptomatic participants. Secondary goals involve analyzing CM disability’s association with physical/psychological factors and comparing physical activity levels between CM patients and asymptomatic individuals.

Materials and methods

Study design

This cross-sectional study employed purposive sampling, adhering to STROBE guidelines20. Participants received comprehensive information and provided voluntary informed consent. Ethical principles following the Declaration of Helsinki were upheld21, with approval from the Centro Superior de Estudios Universitarios La Salle ethics committee (CSEULS-PI-034/2019).

Participants

The participants included in the study were required to meet the proposed inclusion criteria. Male and female adult patients aged between 18 and 65 years were recruited and were required to have a good command of the Spanish language. Participants in the CM group were recruited from a clinic specializing in treating patients with temporomandibular disorders, headaches, and craniofacial pain (Madrid, Spain). The patients had to have a previous medical diagnosis and meet the CM criteria of the International Classification for Headache Disorders22, which are as follows: (a) headache frequency ≥ 15 days per month; (b) migraine symptom frequency ≥ 8 days; (c) chronicity ≥ 3 months; and (d) a history of migraine starting before the age of 50 years. The following cases were excluded: (a) previous cervical and cranial trauma; (b) infectious or tumor diseases; and (c) recent surgical procedures (in the previous 12 months).

The control group consisted of asymptomatic individuals with no history of head and neck pain for at least one year and who did not require any medical treatment or physiotherapy. Participants in this group were intentionally age- and gender-matched with those in the CM group to achieve similar groups. The control group was recruited through social networking from a university population.

Procedure

After giving their consent to participate in the study, all participants were given a set of questionnaires, which included a socio-demographic assessment and were asked to complete a series of self-reports: Head Impact Test (HIT-6)23, International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)24, Tampa scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK-11)25, Pain Catastrophism Scale (PCS)26, chronic pain self-efficacy scale (CPSS)27, Pain Behaviors Questionnaire (PBQ)28.

After the participants had completed the self-report measured, the following physical measured were assessed: cervical range of motion, lumbar range of motion, cervical flexor muscle endurance, maximal isometric contraction of the cervical flexor and extensor muscles was assessed during cervical flexion and extension movements, maximal lumbar isometric contraction and handgrip dynamometry. The assessor was a physical therapist blinded to the participants’ condition. All patients’ assessments were done during the interictal periods.

Physical measures

Cervical range of motion

Cervical range of motion (CROM) was measured in degrees using a cervical range-of-motion device referred to as a CROM (Performance Attainment Associates, Lindstrom, MN)29, which consists of three independent inclinometers, one for each plane of motion, attached to a plastic frame similar to a pair of glasses. The cervical ranges of motion measured were (1) flexion–extension, (3) right-left lateral flexion, (5) right-left rotation. CROM was measured with participants seated in a chair with a backrest, maintaining a 90-degree angle at both the hips and knees, and feet flat on the floor to ensure a standardized and stable position. Each movement was performed three times, and the average value was used for analysis. The CROM has proven to be a valid and reliable tool for measuring the range of motion of the cervical region30.

Lumbar range of movement

Lumbar flexion range of motion was assessed in degrees using a digital inclinometer based on the iHandy mobile application. To perform the measurement, the assessor holds the mobile device over the participants’ sacrum and applies light pressure while the participants perform a lumbar flexion movement. Each movement was repeated three times, and the average value was used for analysis. This measurement has been shown to have good intra-rater and inter-rater reliability, with an intra-class correlation coefficient ≥ 0.8631.

Endurance of the cervical musculature

The endurance of the cervical musculature was measured with a test that primarily assesses the endurance of the neck flexor muscles, which has good reliability32. Participants were placed in the supine position. The examiner raised the participants’ head 2.5 cm above the couch and instructed the participants to hold this position for as long as possible. The examiner then let go of the participants’ head, leaving it suspended, held in place only by the participants’ muscle exertion. The test was finished when the participant could no longer maintain the head in the required position, and the endurance was recorded in seconds. The test was performed two times, and the average value was used for analysis.

Endurance of the lumbar musculature

Endurance of the lumbar musculature was assessed using the Ito test. Participants lay prone with a 10-cm pillow beneath their lower abdomen to reduce lumbar lordosis. With arms parallel to the body axis, they raised their upper body to a 15° angle, maintaining a neutral cervical spine position, and both feet on the couch. The test continued until fatigue, with termination upon a > 10° decrease in trunk angle. Endurance was measured in seconds. Two brief practice attempts (5 s) ensured correct execution. The test was performed twice, and the best result was used for analysis. The Ito test is a valid and reliable measure of lumbar extensor muscle strength33.

Cervical strength

Maximal isometric contraction (MIC) of cervical flexion and extension was assessed using a calibrated handheld digital dynamometer (MicroFET 2 dynamometer, Hoggan Health Industries, Salt Lake City, UT). The dynamometer, with a cushioned pad, was placed on the area to be assessed. For flexion MIC, participants were supine, with the pad on their forehead, performing maximal craniocervical flexion. For extension MIC, participants were prone, with the pad on the occipital area, resisting the assessor’s opposing force. Each movement was tested three times, with each attempt lasting 5 s, and a 60-s rest between attempts. The MIC was measured in kilograms of force (kgf), ensuring consistent reliability34.

Lumbar strength

The extension MIC of the lumbar region was measured using a foot dynamometer (Takei TM 5420, Takei Scientific Instruments CO., Niigata City, Japan). This device has been validated and can be used to determine leg and back strength in held positions, provided that the measurement protocol is standardized (r, 0.91; p < 0.001)35. For the measurement, participants let their arms hang down to hold the dynamometer’s bar with both hands, palms facing the body. The dynamometer chain was adjusted so that the knees were flexed to approximately 110°. The evaluator took 3 measurements, each in kgf, and the mean was used in the data analysis.

Handgrip strength

Isometric handgrip strength was measured using a JAMAR hydraulic handgrip dynamometer (Sammons Preston, Rolyon, Bolingbrook, IL), following the procedure recommended by Roberts et al. Participants sat upright with feet flat on the floor, elbows flexed at 90°, and wrists and forearms in a neutral position36. Grip strength was recorded three times on the dominant hand, in kgf, with a 30-s interval between measurements. This test demonstrates excellent reliability across various populations and conditions37–39.

Psychological and disability measures

Headache-related disability

Disability was assessed using the Spanish HIT-6, comprising 6 items to measure headache-related disability in CM patients23. The questionnaire exhibits acceptable psychometric properties and validation for CM patients40. Scores range from 36 to 78 points, categorized into four severity levels: little or no impact (36–49), some impact (50–55), substantial impact (56–59), and severe impact (60–78).

Pain behaviors

The PBQ assesses pain-related behaviors, initially validated in headache patients41,42. The Spanish version, validated in patients with migraine and tension-type headache, exhibits strong psychometric properties, comprising 19 items across six factors: avoidance behaviors (5 items), active non-verbal complaint (4 items), passive non-verbal complaint (3 items), verbal complaint (3 items), rest (2 items), and medication (2 items)28.

Fear of movement

We assessed fear of movement using the Spanish TSK-11, with good psychometric properties (Cronbach’s α, 0.81)25. It has 2 subscales: one for fear of physical activity and another for fear of harm. Each of 11 items was scored 1–4 (1 = “strongly disagree”, 2 = “disagree”, 3 = “agree”, 4 = “strongly agree”), yielding scores from 11 to 44.

Physical activity level

The IPAQ assessed participants’ physical activity, categorizing them into three levels (high, moderate, low/sedentary) and estimating activity in METs. IPAQ’s psychometric properties are accepted; it has a reliability of about 0.77 (95% CI 0.67–0.84)43.

Pain intensity

Self-reported pain intensity was assessed using the numerical pain scale (NPS) (0–10/10). A score of 0 indicates “no pain”, while a score of 10 indicates “maximum possible pain intensity”44.

Sample size

The sample size was estimated with G*Power 3.1.7 (G*Power of the University of Düsseldorf, Germany)45. A pilot study was conducted with 16 patients with CM and 16 asymptomatic participants to determine differences using Student’s t-test and effect size to compare cervical muscle endurance variables and the handgrip dynamometry pressure. The study employed an alpha error level of 0.05, a statistical power of 80% (1-B error) and an effect size d (0.68 and 0.81). The estimated total sample size was 56 for the cervical muscle endurance variable and 40 for the handgrip dynamometry variable; ultimately, the larger sample size (28 patients with CM and 28 asymptomatic participants) was chosen. An additional 5% of the sample was included to allow for possible withdrawals that may occur during the physical evaluation. For these comparisons, the sample was finally 60 participants.

The sample calculation required for the multiple regression analysis was performed taking into account the use of 8 predictor variables, an alpha error level of 0.05, a statistical power of 99% (1-B error), an R2 of 0.2 and an effect size f2 of 0.25, resulting in a total sample estimate of 65 patients with CM. The procedures followed for this estimation are based on the guidelines outlined by Faul et al. (2009) for calculating sample sizes in studies involving correlation and regression analyses46.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software, version 27.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Statistical analyses were performed at a 95% confidence level; P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. To compare descriptive statistics, physical variables and self-reports scores between the CM group and asymptomatic participants t-test for independent samples was used and the chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated for the outcome variables. According to Cohen’s method, the effect size was classified as small (0.20–0.49), moderate (0.50–0.79) or large (≥ 0.8)47.

An analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used, it included “physical activity level” as a covariate for between-group comparisons of physical measures and kinesiophobia. For this analysis the effect size was estimated with partial eta squared (ηp2).

The relationship between headache-related disability and physical and psychological variables in the CM group was examined using Pearson’s correlation coefficients. A Pearson correlation coefficient > 0.60 indicated a strong correlation, a coefficient between 0.30 and 0.60 indicated a moderate correlation, and a coefficient < 0.30 indicated a low or very low correlation48.

A stepwise multiple linear regression analysis was used to estimate the strength of the association between headache-related disability (criterion variable) and psychological, behavioral, and physical variables (predictor variables). Only variables that obtained moderate correlations in the correlation analysis were included in the regression model. We assessed multicollinearity in the models using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). A VIF near 1 implies minimal multicollinearity; values between 1 and 5 suggest moderate correlation among predictors; and a VIF over 10 indicates significant multicollinearity.

In the development of our multiple linear regression model, we have performed comprehensive diagnostic analyses to verify its robustness and adherence to key assumptions.

The model’s evaluation began with an investigation into the homogeneity of variance, which is crucial for the reliability of the regression estimates. A graphical approach was employed, plotting residuals against fitted values to visually inspect the data. This plot revealed a random dispersion of residuals with no apparent patterns or funnels, leading us to confirm that the variance of the residuals is consistent across all levels of the independent variables, thereby satisfying the homogeneity criterion.

Another critical assumption, the independence of observations, was rigorously tested using the Durbin-Watson statistic. This test is instrumental in detecting any autocorrelation in the residuals that could compromise the integrity of the regression analysis. A value of the statistic proximate to 2.0 was indicative of the absence of autocorrelation, thereby upholding the model’s assumption of independent observations.

Moreover, the normality of the residuals’ distribution was scrutinized using Q-Q plots. These plots provided a visual assessment by comparing the distribution of the residuals to a perfectly normal distribution. The alignment of the residuals along a straight line on the Q-Q plots suggested that the distribution of the residuals aligns well with the assumption of normality.

Lastly, the linearity assumption was substantiated by examining scatter plots of observed versus predicted values and normal P-P plots of standardized residuals. These assessments disclosed a clear linear trajectory, thereby reinforcing our confidence in the linearity of the relationship modeled.

Results

The total study sample consisted of 95 participants (30 asymptomatic participants and 65 patients with CM) who met the inclusion criteria. Statistically significant differences were found only in body mass index (which was higher in the CM group) and in the level of physical activity measured in METS (p = 0.01) (the control group were more active). There were statistically significant differences in the subclassification according to the level of physical activity (Fig. 1). The statistics for the sociodemographic variables are presented in Table 1. All statistics followed a normal distribution except for those representing physical activity.

Fig. 1.

Physical activity subclassification. The graph shows the subclassification of the physical activity levels of both study groups.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for sociodemographic data.

| Measures | CM group (n = 30) |

Asymptomatic group (n = 30) |

p-value t-test (independent samples) or chi-square test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 46.8 ± 12.5 | 43 ± 14.4 | p = 0.281 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.9 ± 4.7 | 23.8 ± 1.6 | p = 0.028 |

| Gender | |||

| Women | 19 (63) | 22 (73) | p = 0.405 |

| Men | 11 (34) | 8 (24) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 12 (40) | 18 (60) | p = 0.052 |

| Single | 7 (23) | 10 (34) | |

| Divorced | 5 (17) | 1 (3) | |

| Widow | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | |

| No answer | 5 (17) | 0 | |

| Educational level | |||

| Primary education | 3 (10) | 2 (7) | p = 0.299 |

| Secondary education | 14 (47) | 9 (38) | |

| College education | 13 (43) | 19 (63) | |

| Employment status | |||

| Unemployed | 7 (23) | 2 (6) | p = 0.057 |

| Sick leave | 7 (23) | 2 (6) | |

| Active | 13 (44) | 17 (57) | |

| Student | 2 (7) | 5 (17) | |

| No answer | 1 (3) | 4 (13) | |

| IPAQ (Mets) | 1554.4 ± 2472.4 | 3848.4 ± 4183.6 | p = 0.001 |

Values are presented as mean ± SD or number (%); CM chronic migraine, BMI Body Mass Index, IPAQ physical activity questionnaire.

Comparative analysis

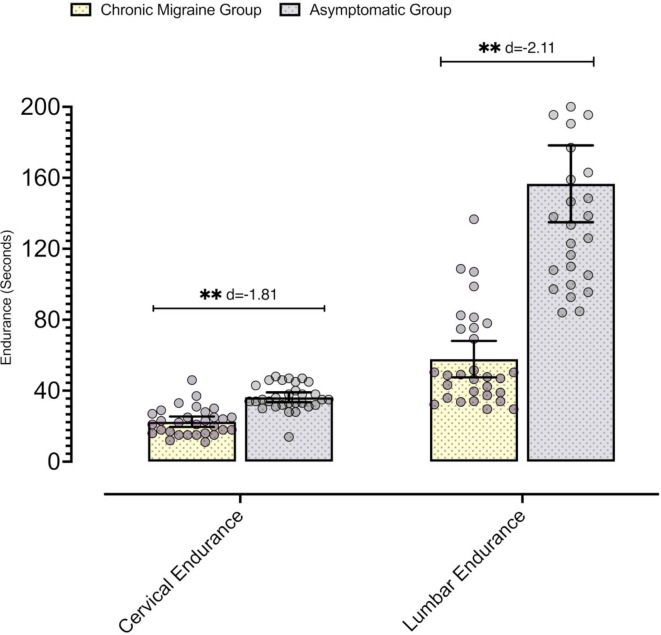

In the comparative analysis, there were statistically significant differences in the variables of range of motion, endurance and MIC for measurements in the cervical region and in other body segments (p < 0.05), and the effect sizes of these comparisons were moderate-high in magnitude (Table 2), with the endurance-related variables having the largest differences (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Comparative analysis between the CM group and the asymptomatic group.

| Measures | CM group (n = 30) | Asymptomatic group (n = 30) | Difference of means (95% CI) | t-student; p-value; Effect size (d) | Covariate: physical activity F; p-value; Eta Squared (ηp2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROM | |||||

| Cervical flexion–extension (°) | 99.36 ± 15.72 | 107.33 ± 11.76 | − 7.96 (− 15.14 to − 0.78) | t = − 2.22; p = 0.030; d = − 0.57 | F = 2.94; p = 0.091; ηp2 = 0.05 |

| Cervical rotation (°) | 113.22 ± 22.99 | 129.1 ± 20.17 | − 15.3 (− 26.47 to − 4.12) | t = − 2.74; p = 0.008; d = − 0.71 | F = 0.11; p = 0.739; ηp2 = 0.002 |

| Cervical lateral flexion (°) | 71.43 ± 18.79 | 83.16 ± 10.56 | − 11.73 (− 19.61 to − 3.85) | t = − 2.98; p = 0.004; d = − 0.77 | F = 0.63; p = 0.429; ηp2 = 0.11 |

| Lumbar flexion (°) | 36.04 ± 8.3 | 46.36 ± 5.71 | − 10.32 (− 14.03 to − 6.63) | t = − 5.60; p < 0.001; d = − 1.44 | F = 1.64; p = 0.205; ηp2 = 0.03 |

| Muscular endurance | |||||

| Cervical endurance (s) | 22.53 ± 7.81 | 36.3 ± 7.41 | − 13.76 (− 17.7 to − 9.83) | t = − 7.01; p < 0.001; d = 1.81 | F = 0.03; p = 0.864; ηp2 = 0.001 |

| Lumbar endurance (s) | 57.81 ± 27.44 | 155.58 ± 59.62 | − 97.77 (− 121.76 to − 73.78) | t = − 8.15; p < 0.001; d = − 2.11 | F = 0.28; p = 0.596; ηp2 = 0.005 |

| Muscular strength | |||||

| Cervical extension (Kgf) | 21.16 ± 5.72 | 25.1 ± 6.18 | − 3.93 (− 7.01 to − 0.85) | t = − 2.55; p = 0.013; d = − 0.66 | F = 8.05; p = 0.006; ηp2 = 0.12 |

| Cervical flexion (Kgf) | 12.56 ± 4.02 | 16 ± 4.85 | − 3.43 (− 5.73 to − 1.13) | t = − 2.98; p = 0.004; d = − 0.77 | F = 9.00; p = 0.004; ηp2 = 0.14 |

| Handgrip (Kgf) | 33.88 ± 6.71 | 40.14 ± 5.94 | − 6.25 (− 9.53 to − 2.98) | t = − 3.82; p < 0.001; d = − 0.98 | F = 7.29; p = 0.009; ηp2 = 0.113 |

| Lumbar extension (Kgf) | 43.78 ± 13.42 | 75.71 ± 19.34 | − 31.92 (− 40.55 to − 23.31) | t = − 7.42; p < 0.001; d = − 1.91 | F = 0.98; p = 0.362; ηp2 = 0.02 |

| Kinesiophobia (TSK-11) | 27.63 ± 7.08 | 21.7 ± 5.52 | 5.93 (2.65 to 9.21) | t = 3.61; p < 0.001; d = 0.93 | F = 0.03; p = 0.859; ηp2 = 0.001 |

| Harm_subscale | 10.36 ± 3.51 | 8.66 ± 2.29 | 1.7 (0.16 to 3.23) | t = 2.22; p = 0.030; d = 0.57 | F = 0.004; p < 0.952; ηp2 = 0.00 |

| Activity Avoidance_subscale | 17 ± 4.71 | 13.33 ± 3.69 | 3.66 (1.48 to 5.85) | t = 3.35; p = 0.001; d = 0.86 | F = 0.03; p < 0.867; ηp2 = 0.00 |

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation. CI coefficient interval, CM Chronic Migraine, ROM Range of motion, TSK Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia.

Fig. 2.

Differences in endurance tests. The graphs represent the comparison of the endurance tests between the two groups.

With respect to the kinesiophobia variable (TSK-11) and the avoidance subscale, there were statistically significant differences with a large effect size (TSK-11; p < 0.001; d = 0.93; Activity Avoidance, p = 0.001; d = 0.86); as well as for the harm subscale although the effect size was moderate (p = 0.030; d = 0.57).

When adjusting with the physical activity covariate, only statistically significant results where obtained for the maximal isometric cervical flexion strength (F = 8.05; p = 0.006; ηp2 = 0.12), maximal isometric cervical extension strength (F = 9.00; p = 0.004; ηp2 = 0.14) and handgrip strength (F = 7.29; p = 0.009; ηp2 = 0.113).

Correlation analysis

Table 3 shows the Pearson correlation analysis. The highest correlations were between disability (HIT-6) and frequency of headaches (HIT-6) (r = 0.51; p < 0.001); and between disability and the avoidance behaviors subscale of the PBQ (r = 0.50; p < 0.001).

Table 3.

Pearson correlation coefficients in CM group.

| N = 60 | Headache-related disability 56.4 ± 7 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Measures | Mean ± SD | r | p-value |

| Headache frequency | 20.2 ± 3.6 | 0.51** | < 0.001 |

| Pain intensity | 5.5 ± 1.4 | 0.41** | 0.001 |

| Harm_subscale | 10.6 ± 3.6 | 0.31* | 0.016 |

| Activity Avoidance_subscale | 17.2 ± 5 | 0.29 | 0.026 |

| Pain behaviour_avoidance behaviors subscale | 4.1 ± 2.3 | 0.50** | < 0.001 |

| Pain behaviour_Rest subscale | 3.8 ± 1.6 | 0.40** | 0.001 |

| Pain behaviour_passive non-verbal complaint subscale | 2.6 ± 1.4 | − 0.01 | 0.927 |

| Pain behaviour_active non-verbal complaint subscale | 3.1 ± 1.8 | 0.07 | 0.586 |

| Pain behaviour_medication subscale | 1.5 ± 0.9 | 0.23 | 0.070 |

| Pain behaviour_verbal complaint_subscale | 2.3 ± 1.5 | 0.31* | 0.014 |

| CROM_FE | 97.8 ± 13.9 | − 0.19 | 0.132 |

| CROM_ROT | 111.8 ± 20.8 | − 0.16 | 0.217 |

| CROM_LF | 70.1 ± 17.8 | 0.11 | 0.410 |

| LROM_F | 37.3 ± 7.5 | − 0.23 | 0.067 |

| C_Endurance | 21.4 ± 7.3 | − 0.31* | 0.016 |

| L_Endurance | 60.3 ± 26.7 | − 0.16 | 0.195 |

| CE_Strength | 20.5 ± 5.9 | − 0.23 | 0.070 |

| CF_Strength | 12.5 ± 4.1 | − 0.17 | 0.173 |

| Handgrip strength | 33.9 ± 7.1 | − 0.32* | 0.012 |

| LE_strength | 44.4 ± 14.5 | − 0.28 | 0.030 |

| IPAQ | 1634.8 ± 1278.2 | 0.15 | 0.238 |

Values are presented as mean ± SD; CROM_FE Cervical Range of motion_flexoextension, CROM_ROT Cervical range of motion rotation, CROM_LF Cervical range of motion lateral flexion, LROM_F Lumbar range of motion flexion, C_Endurance Cervical Endurance, L_Endurance Lumbar Endurance, CE cervical extension, CF cervical flexion, LE lumbar extension, IPAQ physical activity questionnaire.

The physical variables with the highest correlations with disability were the cervical flexor endurance test (r = 0.31; p = 0.016) and handgrip strength (r = 0.32; p = 0.012), and the correlations were negative in magnitude (Table 3).

Regression analysis

Table 4 presents the linear regression model for the disability criterion variable (HIT-6). The model found that headache frequency, avoidance behaviors (PBQ/Avoidance behaviors subscale), and rest (PBQ/Rest subscale) were associated with headache-related disability, together explaining 41% of the variance. Six variables were excluded from the model (pain intensity, fear of movement, harm subscale, verbal complaint subscale, cervical endurance and handgrip strength) due to their lack of significant correlation with the disability outcome or minimal contribution to explaining the variance. The results of the variance inflation factor indicates that there is very little multicollinearity in the model.

Table 4.

Regression model for headache-related disability in chronic migraine group (n = 65).

| Variable criteria: headache-related disability | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall model | ||||

| R2 = 0.44; Adjusted R2 = 0.41; F = 14.695; p < 0.001 | ||||

| Regression coefficient (B) | Standardized coefficient (β) | p-value | VIF | |

| Predictor variables | ||||

| Headache frequency | 0.7 | 0.38 | 0.001 | 1.12 |

| Pain behaviour_Avoidance behaviors subscale | 0.9 | 0.29 | 0.012 | 1.26 |

| Pain behaviour _Rest_subscale | 1 | 0.24 | 0.029 | 1.15 |

| Excluded variables | ||||

| Pain intensity | – | 0.25 | 0.256 | 1.30 |

| Harm subscale (TSK-11) | – | 0.09 | 0.612 | 1.19 |

| Pain behaviour_verbal complaint_subscale | – | 0.05 | 0.654 | 1.29 |

| C_Endurance | – | 0.05 | 0.574 | 1.25 |

| Handgrip strength | – | 0.17 | 0.093 | 1.11 |

VIF Variance Inflation Factor, TSK Tampa scale of kinesiophobia, C. Endurance Cervical Endurance.

Discussion

This study aimed to compare cervical and overall physical variables in patients with CM and asymptomatic participants. Findings revealed that CM patients exhibited lower strength, endurance, and range of motion in all assessed regions. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate these physical variables in the cervical region and in other regions. This represents a novel exploration, as previous research mainly focused on cervical neurophysiological mechanisms in migraine11–14. Our results introduce alternative hypotheses regarding the observed physical deficits in migraine patients.

The reduced physical fitness variables may be linked to the lower physical activity levels observed in these patients, aligning with our initial hypothesis. Existing studies consistently show that migraine patients exhibit lower physical activity levels compared to asymptomatic participants16,49–53. Although the relationship between physical activity levels and deficits in fitness-related variables seems relatively clear, the results are not at all clear when this relationship is established with respect to variables related to migraine worsening. Bond et al. found that patients with migraine had lower physical activity levels, but this has not been related, for example, to migraine frequency53, with recent findings contradicting those results16. Importantly, physical activity or physical exercise was not found to cause migraine exacerbations53, as recently suggested in other studies54.

Bond et al. reported that the analyzed migraine population had a higher body mass index than the asymptomatic participants53, a finding consistent with our results. A number of consistent results from the scientific literature suggest that obesity might be related to the prevalence, frequency and disability of migraine in both pediatric and adult populations55.

In our study, the BMI in the migraine group (25.9) was slightly elevated but did not reach the threshold for obesity. While previous studies have linked migraine with obesity, our sample’s BMI does not fully represent this association, as the asymptomatic group had a BMI of around 23. This discrepancy could be related to the reduced levels of physical activity observed in the CM patients, rather than obesity itself. Lower levels of physical activity, which were significantly different between groups, might contribute to the overall burden of migraine, influencing headache frequency and severity, as suggested in the literature. Thus, it is plausible that reduced physical activity, rather than higher BMI, could be a more critical factor in migraine pathology.

Several literature reviews agree on the preventive effect of exercise on CM and EM56–58, and it has been observed that women with headaches who are more physically active have a lower consumption of analgesics59. Meta-analyses have reported that aerobic exercise can decrease the frequency, duration and intensity of migraine attacks and improve the quality of life of these patients60–62, a clinical trial with similar results using general strength training has recently been published63. However, another trial found no effect of specific strength training on the cervical region64.

The neurophysiological relationship between the upper cervical region and the trigeminal nerve has been extensively documented, with an observed increase in the mechanosensitivity of the cervical region after dural stimulation65. The explanation for this phenomenon might be the convergence of both cervical and trigeminal innervation in the trigeminocervical nucleus in the brainstem65. This relationship could perhaps explain the high prevalence of neck pain in patients with migraine8. According to this assumption, some researchers have hypothesized that manual therapy and specific exercise interventions directed to the cervical region could improve both neck pain and migraine conditions. However, scarce evidence exists regarding the effectiveness of manual therapy in the cervical region for migraine treatment that supports its application62,66–68. Regarding the effectiveness of specific exercise interventions directed to the cervical region, they seem not to be superior to sham ultrasound nor aerobic exercise for the treatment of migraine64; moreover, at 3 months, aerobic exercise showed a greater reduction in migraine frequency compared to cervical exercises69. In contrast, aerobic exercise and full-body resistance training have shown significant results for reducing migraine symptoms and improving quality of life, as previously mentioned61,63. The presence of central sensitization in thalamocortical and cortical levels in patients with migraine represents evidence of dysfunctional central pain mechanisms that could affect pain sensitivity throughout the body70. Cutaneous allodynia and temporal summation in extracephalic regions have also been associated with a worse outcome and a higher migraine frequency71,72. It is hypothesized that exercise could produce a generalized decrease in pain due to exercise-induced analgesia, a phenomenon that seems to involucrate mainly opioid and endocannabinoid systems73. Aerobic exercise and full-body resistance exercise have also been shown to decrease pain sensitivity in other chronic pain populations, such as fibromyalgia and chronic low back pain74–77. These results demonstrate that it is not necessary to directly apply an exercise intervention to a specific region to obtain an improvement in pain.

For this reason, it is possible that the cervical region is not a specific therapeutic target for patients with migraine. A more general physical assessment such as the one performed in our study should therefore be conducted to identify possible deficits in variables related to range of motion and strength/endurance to better determine the ideal exercise prescription for these patients.

It is important to note that our study did not specifically record the presence of low back pain (LBP) in migraine patients. However, what we did observe and record was that patients with chronic migraine (CM) exhibited significantly lower lumbar muscle endurance compared to asymptomatic participants. This finding raises the possibility that undiagnosed or unreported LBP could have contributed to the reduced lumbar endurance seen in the CM group. Previous studies, such as those by Yoon et al. (2013), have demonstrated a strong association between chronic headaches, including CM, and frequent LBP, suggesting that the neurobiology of chronic headache may involve generalized pain processing dysfunction that extends beyond the trigeminal system78. This broader pain sensitization could potentially explain the lumbar deficits observed in our study.

Additionally, a recent study by Deodato et al. (2024) identified musculoskeletal dysfunctions throughout the spine in patients with chronic primary headaches, including CM and chronic tension-type headache, with no significant differences in postural alterations or musculoskeletal dysfunctions between these two headache types79. This finding further supports the hypothesis that musculoskeletal dysfunctions, including in the lumbar region, could be related to central sensitization in chronic migraine patients.

Given the evidence linking chronic headache with LBP, future studies should consider incorporating a direct assessment of LBP in CM patients to explore its potential role in the observed physical impairments, particularly in the lumbar region. The high prevalence of LBP in individuals with chronic headaches underscores the importance of a more comprehensive evaluation of musculoskeletal function in this population.

Findings related to headache-related disability show that the predictors are headache frequency, and activity avoidance and rest of the PBQ. Other studies have independently found relationships between disability and variables such as headache frequency, activity avoidance80,81 and social avoidance81. In relation to these three variables, it has been observed that patients with migraine who avoid physical activity were more likely to experience CM and more frequent headaches82.

After the present results, authors’ recommendations for future research would be to assess the effects of a combined intervention including aerobic and full body strength exercises. In addition, the assessment of the physical condition of the migraine patients in a general approach would be needed over a segmental cervical assessment.

Limitations

This study has limitations to consider. Physical activity data relied on self-reports, which are subjective and prone to recall bias and inaccuracies. Future research should employ objective instruments like accelerometers to capture precise physical activity data. Additionally, measuring cardiorespiratory fitness could offer a more comprehensive understanding of patients’ physical fitness. The cross-sectional design limits predictive insights. Comorbidities were not assessed, and comparisons with patients having episodic migraines (EM) could be beneficial in future studies, enhancing our understanding of physical variables’ behavior in CM versus EM patients.

Conclusions

This study revealed that patients with CM exhibit reduced overall range of motion, lower endurance and strength in cervical and non-cervical areas, and lower physical activity levels compared to asymptomatic participants. Headache-related disability was primarily associated with headache frequency, activity avoidance behaviors, and rest.

Author contributions

Author RL contributed to the conception and design of the manuscript. Author RL, author MGA, author ARV, and author APA have given substantial contributions to acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data. All authors have participated to drafting the manuscript, author TGP revised it critically. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Centro Superior de Estudios Universitarios La Salle provided funding and support for this study.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Amiri, P. et al. Migraine: a review on its history, global epidemiology, risk factors, and comorbidities. Front. Neurol.12, 800605. 10.3389/FNEUR.2021.800605 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mathew, N. T., Stubits, E. & Nigam, M. P. Transformation of episodic migraine into daily headache: analysis of factors. Headache22, 66–68. 10.1111/J.1526-4610.1982.HED2202066.X (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vos, T. et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet386, 743–800. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Natoli, J. L. et al. Global prevalence of chronic migraine: a systematic review. Cephalalgia30, 599–609. 10.1111/J.1468-2982.2009.01941.X (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buse, D. et al. Chronic migraine prevalence, disability, and sociodemographic factors: results from the American migraine prevalence and prevention study. Headache52, 1456–1470. 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2012.02223.x (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lipton, R. B. et al. Ineffective acute treatment of episodic migraine is associated with new-onset chronic migraine. Neurology84, 688–695. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001256 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karsan, N. & Goadsby, P. J. Biological insights from the premonitory symptoms of migraine. Nat. Rev. Neurol.14, 699–710. 10.1038/S41582-018-0098-4 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Khazali, H. M. et al. Prevalence of neck pain in migraine: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cephalalgia 033310242110680. 10.1177/03331024211068073 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Calhoun, A. H. et al. The prevalence of neck pain in migraine. Headache: J. Head Face Pain50, 1273–1277. 10.1111/J.1526-4610.2009.01608.X (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aoyama, N. Involvement of cervical disability in migraine: a literature review. Br. J. Pain15, 199–212. 10.1177/2049463720924704 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bevilaqua-Grossi, D. et al. Cervical mobility in women with migraine. Headache49, 726–731. 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.01233.x (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pinheiro, C. F. et al. Neck active movements assessment in women with episodic and chronic migraine. J. Clin. Med.10. 10.3390/JCM10173805 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Florencio, L. et al. Muscle endurance and cervical electromyographic activity during submaximal efforts in women with and without migraine. Clin. Biomech. Elsevier Ltd. 82. 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2021.105276 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Florencio, L. et al. Cervical muscle strength and muscle coactivation during isometric contractions in patients with migraine: a cross-sectional study. Headache55, 1312–1322. 10.1111/head.12644 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Florencio, L. et al. Comparison of cervical muscle isometric force between migraine subgroups or migraine-associated neck pain: a controlled study. Sci. Rep.11. 10.1038/S41598-021-95078-4 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.de Oliveira, A. B. et al. Physical inactivity and headache disorders: cross-sectional analysis in the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil). Cephalalgia41, 1467–1485. 10.1177/03331024211029217 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nyberg, J. et al. Cardiovascular fitness and risk of migraine: a large, prospective population-based study of Swedish young adult men. BMJ Open9. 10.1136/BMJOPEN-2019-029147 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Farris, S. G. et al. Anxiety sensitivity and intentional avoidance of physical activity in women with probable migraine. Cephalalgia39, 1465–1469. 10.1177/0333102419861712 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benatto, M. T. et al. Kinesiophobia is associated with migraine. Pain Med.20, 846–851. 10.1093/PM/PNY206 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.von Elm, E. et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol.61, 344–349. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA310, 2191–2194. 10.1001/JAMA.2013.281053 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.ICHD-3. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia38, 1–211 (2018). 10.1177/0333102417738202 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Martin, M., Blaisdell, B., Kwong, J. W. & Bjorner, J. B. The short-form headache impact test (HIT-6) was psychometrically equivalent in nine languages. J. Clin. Epidemiol.57, 1271–1278. 10.1016/J.JCLINEPI.2004.05.004 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roman-Viñas, B. et al. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: reliability and validity in a Spanish population. Eur. J. Sport Sci.10, 297–304. 10.1080/17461390903426667 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gómez-Pérez, L., López-Martínez, A. E. & Ruiz-Párraga, G. T. Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK). J. Pain12, 425–435. 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.08.004 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.García Campayo, J. et al. Validación de la versión española de la escala de la catastrofización ante El Dolor (Pain Catastrophizing Scale) en la fibromialgia. Med. Clin. (Barc)131, 487–492. 10.1157/13127277 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martín-Aragón, M. et al. Percepción De autoeficacia en dolor crónico. adaptación y validación de la Chronic Pain Selfefficacy Scale 1151–1176 (Revista de PSICOLOGÍA DE, 1999). 10.21134/PSSA.V11I1.799

- 28.Rodríguez Franco, L., Cano García, F. J. & Blanco Picabia, I. Conductas De dolor y discapacidad en migrañas y cefaleas tensionales. Adaptación española Del Pain Behavior Questionnaire (PBQ) Y Del Headache disability inventory (HDI). Análisis Y modificación de conducta26, 739–762 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Audette, I., Dumas, J. P., Côté, J. N. & De Serres, S. J. Validity and between-day reliability of the cervical range of motion (CROM) device. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther.40, 318–323 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams, M. A., McCarthy, C. J., Chorti, A., Cooke, M. W. & Gates, S. A systematic review of reliability and validity studies of methods for measuring active andPassive cervical range of motion. J. Manipulative Physiol. Ther.33, 138–155. 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.12.009 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kolber, M. J. et al. The reliability and concurrent validity of measurements used to quantify lumbar spine mobility: an analysis of an iphone® application and gravity based inclinometry. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther.8, 129–137. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/23593551/?tool = EBI (2013). [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Edmondston, S. J. et al. Reliability of isometric muscle endurance tests in subjects with postural neck pain. J. Manipulative Physiol. Ther.31, 348–354. 10.1016/J.JMPT.2008.04.010 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Müller, R., Strässle, K. & Wirth, B. Isometric back muscle endurance: an EMG study on the criterion validity of the Ito test. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol.20, 845–850. 10.1016/J.JELEKIN.2010.04.004 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vannebo, K. T., Iversen, V. M., Fimland, M. S. & Mork, P. J. Test-retest reliability of a handheld dynamometer for measurement of isometric cervical muscle strength. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 31, 557–565. 10.3233/BMR-170829 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coldwells, A., Atkinson, G. & Reilly, T. Sources of variation in back and leg dynamometry. Ergonomics37, 79–86. 10.1080/00140139408963625 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roberts, H. C. et al. A review of the measurement of grip strength in clinical and epidemiological studies: towards a standardised approach. Age Ageing40, 423–429. 10.1093/AGEING/AFR051 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karagiannis, C. et al. Test–retest reliability of handgrip strength in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD: J. Chronic Obstr. Pulmon. Dis.17, 568–574. 10.1080/15412555.2020.1808604 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Savva, C., Giakas, G., Efstathiou, M. & Karagiannis, C. Test-retest reliability of handgrip strength measurement using a hydraulic hand dynamometer in patients with cervical radiculopathy. J. Manipulative Physiol. Ther.37, 206–210. 10.1016/J.JMPT.2014.02.001 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bohannon, R. W. Test-retest reliability of measurements of hand-grip strength obtained by dynamometry from older adults: a systematic review of research in the PubMed database. J. Frailty Aging6, 83–87. 10.14283/jfa.2017.8 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rendas-Baum, R. et al. Validation of the headache impact test (HIT-6) in patients with chronic migraine. Health Qual. Life Outcomes12, 1–10. 10.1186/S12955-014-0117-0/TABLES/8 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Philips, C. & Hunter, M. Pain behavior in headache sufferers. Behav. Anal. Modif.4, 257–266. https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/en/publications/pain-behavior-in-headache-sufferers (1981).

- 42.Appelbaum, K. A., Radnitz, C. L., Blanchard, E. B. & Prins, A. The Pain Behavior Questionnaire (PBQ): a global report of pain behavior in chronic headache. Headache: J. Head Face Pain28, 53–58. 10.1111/J.1365-2524.1988.HED2801053.X (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Angarita-Fonseca, A., Camargo-Lemos, D. M. & Oróstegui-Arenas, M. Reproducibilidad del tiempo en posición sedente evaluado con el International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) y el Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ). MedUNAB13, 5–26. https://revistas.unab.edu.co/index.php/medunab/article/view/439 (2010).

- 44.Sendlbeck, M., Araujo, E. G., Schett, G. & Englbrecht, M. Psychometric properties of three single-item pain scales in patients with rheumatoid arthritis seen during routine clinical care: a comparative perspective on construct validity, reproducibility and internal responsiveness. RMD Open1. 10.1136/RMDOPEN-2015-000140 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G. & Buchner, A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods39, 175–191. 10.3758/BF03193146 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Erdfelder, E., FAul, F., Buchner, A. & Lang, A. G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods41, 1149–1160. 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149/METRICS (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Second (LEA, 1988).

- 48.Hinkle, D. E., Wiersma, W. & Jurs, S. G. Applied Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences. http://jebs.aera.net (1988).

- 49.Rogers, D. G., Bond, D. S., Bentley, J. P. & Smitherman, T. A. Objectively measured physical activity in migraine as a function of headache activity. Headache60, 1930–1938. 10.1111/HEAD.13921 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Varkey, E., Hagen, K., Zwart, J. A. & Linde, M. Physical activity and headache: results from the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT). Cephalalgia28, 1292–1297. 10.1111/J.1468-2982.2008.01678.X (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stronks, D. L., Tulen, J. H. M., Bussmann, J. B. J., Mulder, L. J. M. M. & Passchier, J. Interictal daily functioning in migraine. Cephalalgia24, 271–279. 10.1111/J.1468-2982.2004.00661.X (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krøll, L. S. et al. Level of physical activity, well-being, stress and self-rated health in persons with migraine and co-existing tension-type headache and neck pain. J. Headache Pain18. 10.1186/S10194-017-0753-Y (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Bond, D. S. et al. Objectively measured physical activity in obese women with and without migraine. Cephalalgia35, 886–893. 10.1177/0333102414562970 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hagan, K. K. et al. Prospective cohort study of routine exercise and headache outcomes among adults with episodic migraine. Headache61, 493–499. 10.1111/HEAD.14037 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Verrotti, A., Di Fonzo, A., Penta, L., Agostinelli, S. & Parisi, P. Obesity and headache/migraine: the importance of Weight reduction through lifestyle modifications. Biomed. Res. Int.2014. 10.1155/2014/420858 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Barber, M. & Pace, A. Exercise and migraine prevention: a review of the literature. Curr. Pain Headache Rep.24. 10.1007/S11916-020-00868-6 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Song, T. J. & Chu, M. K. Exercise in treatment of migraine including chronic migraine. Curr. Pain Headache Rep.25. 10.1007/S11916-020-00929-W (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Amin, F. M. et al. The association between migraine and physical exercise. J. Headache Pain19, 83. 10.1186/S10194-018-0902-Y (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Müller, B. et al. Physical activity is associated with less analgesic use in women reporting headache—a cross-sectional study of the German Migraine and Headache Society (DMKG). Pain Ther.11. 10.1007/S40122-022-00362-4 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Lemmens, J. et al. The effect of aerobic exercise on the number of migraine days, duration and pain intensity in migraine: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J. Headache Pain20, 16. 10.1186/s10194-019-0961-8 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.La Touche, R. et al. Is aerobic exercise helpful in patients with migraine? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports30, 965–982. 10.1111/sms.13625 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Herranz-Gómez, A., García-Pascual, I., Montero-Iniesta, P., Touche, R. & La, Paris-Alemany, A. Effectiveness of exercise and manual therapy as treatment for patients with migraine, tension-type headache or cervicogenic headache: an umbrella and mapping review with meta-meta-analysis. Appl. Sci.11, 6856. 10.3390/app11156856 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sari Aslani, P., Hassanpour, M., Razi, O., Knechtle, B. & Parnow, A. Resistance training reduces pain indices and improves quality of life and body strength in women with migraine disorders. Sport Sci. Health 202118, 2. 10.1007/S11332-021-00822-Y (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Benatto, M. T. et al. Neck-specific strengthening exercise compared with placebo sham ultrasound in patients with migraine: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Neurol.22, 126. 10.1186/S12883-022-02650-0 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bartsch, T. & Goadsby, P. J. Increased responses in trigeminocervical nociceptive neurons to cervical input after stimulation of the dura mater. Brain126, 1801–1813. 10.1093/brain/awg190 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Luedtke, K. et al. Neck treatment compared to aerobic exercise in migraine: a preference-based clinical trial. Cephalalgia Rep.3, 251581632093068. 10.1177/2515816320930681 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jafari, M., Bahrpeyma, F., Togha, M., Vahabizad, F. & Hall, T. Effects of upper cervical spine manual therapy on central sensitization and disability in subjects with migraine and neck pain. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J.13, 177–185. 10.32098/MLTJ.01.2023.21 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 68.Muñoz-Gómez, E., Inglés, M., Serra-Añó, P. & Espí-López, G. V. Effectiveness of a manual therapy protocol based on articulatory techniques in migraine patients. A randomized controlled trial. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract.54, 102386. 10.1016/J.MSKSP.2021.102386 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Is, E. E., Coskun, O., Likos Akpinar, R. & Is, S. The effectiveness of aerobic exercise and neck exercises in pediatric migraine treatment: a randomized controlled single-blind study. Ir. J. Med. Sci., 1–9. 10.1007/S11845-024-03660-2/TABLES/6 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 70.Sebastianelli, G. et al. Central sensitization mechanisms in chronic migraine with medication overuse headache: a study of thalamocortical activation and lateral cortical inhibition. Cephalalgia43. 10.1177/03331024231202240/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/10.1177_03331024231202240-FIG4.JPEG (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 71.Pijpers, J. A., Kies, D. A., van Zwet, E. W., de Boer, I. & Terwindt, G. M. Cutaneous allodynia as predictor for treatment response in chronic migraine: a cohort study. J. Headache Pain24, 1–11. 10.1186/S10194-023-01651-9/TABLES/3 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.De Icco, R. et al. Experimentally induced spinal nociceptive sensitization increases with migraine frequency: a single-blind controlled study. Pain161, 429–438. 10.1097/J.PAIN.0000000000001726 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lesnak, J. B. & Sluka, K. A. Mechanism of exercise-induced analgesia: what we can learn from physically active animals. Pain Rep.5, E850. 10.1097/PR9.0000000000000850 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hernando-Garijo, I., Medrano-De-la-fuente R.et al. Immediate effects of a telerehabilitation program based on aerobic exercise in women with fibromyalgia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health18, 2075. 10.3390/IJERPH18042075 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 75.Larsson, A. et al. Resistance exercise improves muscle strength, health status and pain intensity in fibromyalgia—a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Res. Ther.17. 10.1186/S13075-015-0679-1 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 76.Suh, J. H., Kim, H., Jung, G. P., Ko, J. Y. & Ryu, J. S. The effect of lumbar stabilization and walking exercises on chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Medicine98, e16173. 10.1097/MD.0000000000016173 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cortell-Tormo, J. M. et al. Effects of functional resistance training on fitness and quality of life in females with chronic nonspecific low-back pain. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 31, 95–105. 10.3233/BMR-169684 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yoon, M. S. et al. Chronic migraine and chronic tension-type headache are associated with concomitant low back pain: results of the German Headache Consortium study. Pain154, 484–492. 10.1016/J.PAIN.2012.12.010 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Deodato, M., Granato, A., Del Frate, J., Martini, M. & Manganotti, P. Differences in musculoskeletal dysfunctions and in postural alterations between chronic migraine and chronic tension type headache: a cross-sectional study. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther.37, 404–411. 10.1016/J.JBMT.2023.11.011 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pradeep, R. et al. Quality of life, and its predictors. Ann. Neurosci.27, 18–23. 10.1177/0972753120929563 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Klonowski, T., Kropp, P., Straube, A. & Ruscheweyh, R. Psychological factors associated with headache frequency, intensity, and headache-related disability in migraine patients. Neurol. Sci.43, 1255–1266. 10.1007/S10072-021-05453-2 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Farris, S. G. et al. Intentional avoidance of physical activity in women with migraine. Cephalalgia Rep.1, 251581631878828. 10.1177/2515816318788284 (2018). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.