ABSTRACT

Background

TNF‐related apoptosis‐inducing ligand (TRAIL) belongs to the tumor necrosis factor superfamily. TRAIL selectively induces apoptosis in tumor cells while sparing normal cells, which makes it an attractive candidate for cancer therapy. Recombinant soluble TRAIL and agonistic antibodies against TRAIL receptors have demonstrated safety and tolerability in clinical trials. However, they have failed to exhibit expected clinical efficacy. Consequently, extensive research has focused on optimizing TRAIL‐based therapies, with one of the most common approaches being the construction of TRAIL fusion proteins.

Methods

An extensive literature search was conducted to identify studies published over the past three decades related to TRAIL fusion proteins. These various TRAIL fusion strategies were categorized based on their effects achieved.

Results

The main fusion strategies for TRAIL include: 1. Construction of stable TRAIL trimers; 2. Enhancing the polymerization capacity of soluble TRAIL; 3. Increasing the accumulation of TRAIL at tumor sites by fusing with antibody fragments or peptides; 4. Decorating immune cells with TRAIL; 5. Prolonging the half‐life of TRAIL in vivo; 6. Sensitizing cancer cells to overcome resistance to TRAIL treatment.

Conclusion

This work focuses on the progress in recombinant TRAIL fusion proteins and aims to provide more rational and effective fusion strategies to enhance the efficacy of recombinant soluble TRAIL, facilitating its translation from bench to bedside as an effective anti‐cancer therapeutic.

Keywords: apoptosis, cancer, fusion protein, resistance, TRAIL

This review comprehensively covers the TRAIL fusion proteins that have been reported in recent years. It also summarizes six commonly employed strategies used in the construction of TRAIL fusion proteins.

Abbreviations

- ABD

albumin‐binding domain

- ADCC

antibody‐dependent cell‐mediated cytotoxicity

- Apaf‐1

apoptotic protease activating factor 1

- BAK

BCL‐2 homologous antagonist killer

- BAX

B‐cell lymphoma 2‐associated X

- BCL‐2

B‐cell lymphoma 2

- BID

BH3‐interacting domain death agonist

- c‐FLIP

cellular FLICE‐inhibitory protein

- DcR1

decoy receptor 1

- DcR2

decoy receptor 2

- DISC

death‐inducing signaling complex

- DR4

death receptor 4

- DR5

death receptor 5

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- EHD2

heavy‐chain domain 2

- ELPs

elastin‐like polypeptides

- ERK

extracellular signal‐regulated kinase

- FADD

Fas‐associated protein with death domain

- FeSOD

iron superoxide dismutase

- Fn14

fibroblast growth factor‐inducible 14

- HER2

human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- IAP

inhibitor of apoptosis

- IgBDs

immunoglobulin‐binding domains

- IgE

immunoglobulin E

- JNK

c‐Jun N‐terminal kinase

- LUBAC

linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex

- LZ

leucine zipper

- MAPK

mitogen‐activated protein kinase

- NEMO

NF‐κB essential modulator

- NF‐kB

nuclear factor kappa‐light‐chain‐enhancer of activated B‐cells

- NK cells

natural killer cells

- OPG

osteoprotegrin

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositide 3‐kinases

- RIPK1

receptor‐interacting serine/threonine protein kinase 1

- RIPK3

receptor‐interacting serine/threonine protein kinase 3

- scFv

single‐chain variable fragments

- scTRAIL

single‐chain trimeric TRAIL

- SMAC

second mitochondria‐derived activator of caspase

- STAT3

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

- tBID

truncated BH3‐interacting domain death agonist

- TNC

tenascin‐C

- TNFRSF

tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily

- TNFSF

tumor necrosis factor superfamily

- TRAF2

TNF receptor‐associated factor 2

- TRAIL

tumor necrosis factor‐related apoptosis‐inducing ligand

- TWEAK

tumor necrosis factor‐like weak inducer of apoptosis

- VEGFR2

vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2

- XIAP

X‐linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein

1. Introduction

Tumor necrosis factor‐related apoptosis‐inducing ligand (TRAIL), also known as Apo‐2 ligand (Apo2L), belongs to the tumor necrosis factor superfamily (TNFSF) [1]. TRAIL has demonstrated the ability to induce apoptosis in cancer cells while causing little damage to normal cells, making it a promising candidate for cancer therapy. Since its discovery nearly three decades ago, recombinant soluble TRAIL (sTRAIL) and monoclonal antibodies targeting agonistic TRAIL receptors have been developed and evaluated in both preclinical and clinical studies. Although these drugs have shown good tolerability in patients during clinical trials, they have failed to elicit compelling objective responses either as monotherapy or in combination with other therapeutic agents [2].

Nevertheless, there is still considerable interest in developing TRAIL‐based therapeutics as cancer‐selective drugs by enhancing the pharmacokinetic and/or pharmacodynamic properties of TRAIL. One significant approach is the construction of genetically engineered fusion proteins that combine recombinant sTRAIL with other functional proteins or polypeptides. In recent years, many elegantly designed recombinant sTRAIL fusion proteins have been reported, with an increasingly wide range of fusion partners. Some of these have demonstrated superior anticancer activity, and several have entered clinical trials. This review focused on the progress in recombinant TRAIL fusion proteins, including updates on their clinical trials in order to provide more rational and effective fusion strategies to enhance the efficacy of recombinant sTRAIL and facilitate its development for cancer therapy.

2. TRAIL Signaling

As an immunocyte cytokine, TRAIL is expressed as a homotrimeric type II transmembrane protein on the surfaces of various immunocytes including natural killer (NK) cells [3], activated T cells, monocytes, dendritic cells, and macrophages. It plays a role in regulating immune surveillance [1]. The trimeric structure of TRAIL relies on the coordination of three Cys‐230 residues from each monomer with one Zn2+ ion at its trimeric core, and the Zn2+ ion is also essential for maintaining stability and biological activity for the trimeric TRAIL [4]. Similar to other members of the TNFSF family, the extracellular domain of membrane‐bound TRAIL can be cleaved from the cell membrane to generate sTRAIL, which is also a bioactive homotrimer. However, it has been demonstrated that membrane‐bound TRAIL possesses much stronger cancer cell killing activity than the soluble version [5].

TRAIL interacts with five receptors: TRAIL‐R1/death receptor (DR) 4, TRAIL‐R2/DR5, TRAIL‐R3/decoy receptor (DcR) 1, TRAIL‐R4/DcR2, and osteoprotegrin (OPG) [6]. Both DR4 and DR5 serve as agonistic receptors, with their extracellular domain containing a preligand assembly domain (PLAD) that promotes the oligomerization of the DR4 and DR5 trimers to enhance binding with TRAIL [7]. The intracellular domains of DR4 and DR5 contain the full‐length intracellular death domain (DD), a conserved motif crucial for cell death induction [8]. There are two decoy TRAIL receptors: DcR1 lacks a cytosolic region while DcR2 has a truncated, non‐functional cytoplasmic DD. OPG is a soluble receptor without an intracellular domain. These three receptors cannot initiate cell death signaling, but they act as decoys competitively inhibiting the binding of TRAIL to DR4 and DR5 [9].

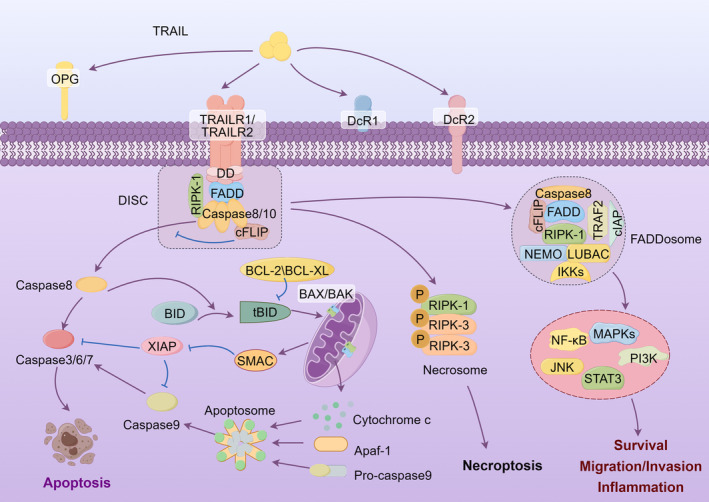

Ligation of TRAIL trimers to DR4 and DR5 initiates receptors trimerization, then leading to the formation of higher‐order complexes [10]. The crosslinked receptors lead to cross‐linking of their intracellular DDs. Then, their DDs recruit the intracellular adaptor Fas‐associated protein with death domain (FADD), which further recruits initiator caspases: procaspase‐8, and/or procaspase‐10, to form the death‐inducing signaling complex (DISC) [11]. Procaspase‐8/10 within the DISC is then activated via proteolytic cleavage, and following activates downstream effector proteins caspase‐3, ‐6, and ‐7. Activated effector caspases then cleave vital cellular proteins, ultimately causing apoptosis. This pathway is referred to as the “extrinsic apoptosis pathway” [12]. In some cells, TRAIL triggers the intrinsic apoptotic pathway by the caspase‐8‐mediated cleavage of BH3‐interacting domain death agonist (BID) to generate truncated BH3‐interacting domain death agonist (tBID). tBID subsequently binds and activates the proapoptotic proteins B‐cell lymphoma 2 (BCL‐2)‐associated X (BAX) and BCL‐2 homologous antagonist killer (BAK), resulting in mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization, and the subsequent release of cytochrome c and the second mitochondria‐derived activator of caspase (SMAC) into the cytoplasm [13]. Cytochrome c then complexes with apoptotic protease activating factor 1 (Apaf‐1) and procaspase‐9 to form the apoptosome, which activates caspase‐9 followed by the hydrolysis of caspase‐3, ‐6, and ‐7, ultimately resulting in cellular apoptosis [14] (Figure 1). The extent to which DR4 and DR5 induce apoptosis in cancer cells via extrinsic or intrinsic pathways remains incompletely characterized and appears to differ depending on the cell type.

FIGURE 1.

The apoptotic and non‐apoptotic pathways of TRAIL.

In addition to its role in apoptosis induction, TRAIL binding with DR4 and DR5 may also elicit noncanonical signaling pathways. Under certain conditions, such as caspase‐8 deficiency or inactivation [15], receptor‐interacting serine/threonine protein kinase 1 (RIPK1) is recruited to the TRAIL DRs, which then recruits and phosphorylates RIPK3, leading to the formation of the necrosome and the induction of necroptosis [16] (Figure 1).

TRAIL can also trigger inflammatory and cell survival pathways, although the signaling mechanisms are not fully understood. Ligation of TRAIL receptors leads to the formation of DISC (complex I), which presumably dissociates from the receptors and assembles into a secondary cytoplasmic complex known as the FADDosome (complex II) [17, 18]. The FADDosome consists of caspase‐8, FADD, and RIPK1, along with cellular FLICE‐inhibitory protein (c‐FLIP) [17], caspase‐10, TNF receptor‐associated factor 2 (TRAF2), inhibitors of apoptosis (IAPs), NF‐κB essential modulator (NEMO) [19], the linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex (LUBAC) [20], and other regulatory molecules. This complex then leads to inflammation or cell survival via pathways such as nuclear factor κB (NF‐κB), mitogen‐activated protein kinase (MAPK) including p38, phosphoinositide 3‐kinases/protein kinase B (PI3K/Akt), extracellular signal‐regulated kinase (ERK), c‐Jun N‐terminal kinase (JNK), and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) [21] (Figure 1). Furthermore, emerging evidence suggests that DcR2 may induce noncanonical TRAIL signaling through its truncated intracellular domain [22].

3. Dilemma of TRAIL Research

Given TRAIL's ability to selectively induce apoptosis in tumor cells, recombinant human TRAIL and TRAIL‐receptor agonistic antibodies have been developed as anticancer therapeutics. These agents, classified as first‐generation TRAIL receptor agonists (TRAs), have demonstrated promising preclinical antitumor activity by inducing apoptosis in various tumor cell types [23]. Clinical trials have shown that these agents are well tolerated by patients, even at high doses. However, they seem to elicit a limited therapeutic efficacy.

Agonistic antibody to DR4, such as Mapatumumab [24, 25, 26, 27, 28], and agonistic antibody to DR5, including Conatumumab [29, 30], Tigatuzumab [31, 32, 33], Drozitumab [34], Lexatumumab [35, 36], and LBY135 [37], have been evaluated in Phase 1 and/or 2 clinical trials as monotherapy or in combination for the treatment of various cancers. These antibodies demonstrated acceptable safety and tolerability, but their efficacy was generally underwhelming, with only negligible benefits, if any, reported.

Dulanermin, the first recombinant soluble human TRAIL (aa114‐281) [38], has completed clinical trials from Phase 1 to Phase 3 in patients of non‐small cell lung cancer [39, 40, 41], B‐cell lymphomas [42], colorectal cancer [43], or non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma [44], either as monotherapy or in combination with other anticancer therapies. These trials demonstrated that dulanermin was safe and well tolerated. However, the clinical efficacy was rather limited [2, 45]. Combining TRAIL with paclitaxel, carboplatin (PC), and bevacizumab (PCB) did not improve the patients' clinical outcomes [40] or elicit rather limited therapeutic efficacy [41]. Another recombinant TRAIL variant, circularly permuted TRAIL (CPT, Aponermin), has entered Phase 1, 2, and 3 studies [46, 47, 48, 49]. CPT in combination with thalidomide and dexamethasone was well tolerated and showed significant improvements in progression‐free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), and overall response rate (ORR) in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma in the Phase 3 trial. However, the investigators found that this benefit was still limited compared to that of other new drugs [49].

The challenges encountered by TRAIL and TRAs in transitioning from bench to bedside are primarily attributed to three main factors: pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and resistance. Recombinant sTRAIL has a short serum half‐life (0.56–1.02 h in Phase 1 trials in patients [38]), which leads to rapid systemic clearance via renal excretion [50]. Consequently, repeated administration is necessary for maintaining therapeutic levels in circulation. Furthermore, membrane‐bound TRAIL is more potent (100‐ to 1000‐fold) as an inducer of cell death compared to sTRAIL due to its ability to oligomerize or cluster DR4 and DR5, facilitating more efficient downstream signal transduction [51, 52]. In contrast, recombinant sTRAIL or agonistic TRAIL receptor antibodies struggle to anchor to cell membranes, resulting in inefficient clustering of TRAIL receptors and lower effective apoptotic signal transduction than membrane‐bound TRAIL [51]. Additionally, many tumor cells exhibit inherent or acquired resistance toward TRAIL or agonistic TRAIL receptor antibodies through various mechanisms.

Therefore, to enhance the clinical efficacy of TRAIL, efforts should be focused on these three areas.

4. Construction of Recombinant TRAIL Fusion Proteins

To address the limitations of TRAIL‐based therapy, numerous strategies have been investigated to enhance the antitumor efficacy of TRAIL, including the engineering of TRAIL fusion proteins, combination with chemotherapeutic drugs, developing TRAIL sensitizers, TRAIL gene therapy, and targeted delivery of TRAIL by nanocarriers or host cells (reviewed in [2]). Among these strategies, the construction of recombinant TRAIL fusion proteins stands out as an efficacious and fundamental approach, which is to fuse the DNA of sTRAIL with DNA encoding one or more functional peptides/proteins with genetic engineering methods. Then the resulting recombinant construct is transformed into prokaryotic cells (e.g., Escherichia coli) or eukaryotic cells (e.g., CHO cells) to express the fusion proteins.

4.1. Construction of Stable TRAIL Trimers

As mentioned above, the structure of homotrimer is prerequisite for the biological activity of TRAIL. However, recombinant soluble trimeric TRAIL is prone to instability, leading to dissociation into monomers and subsequent formation of disulfide‐linked dimers, which exhibit significantly reduced apoptotic activity compared to trimers [53]. Therefore, the primary focus in the development of TRAIL fusions is on achieving stable trimer formation. Covalently linking three soluble recombinant TRAIL monomers into a single polypeptide promotes trimerization, resulting in improved stability and cytotoxicity comparable to native TRAIL. This fused single‐chain trimeric TRAIL (scTRAIL) often serves as a tool or module for constructing more intricate TRAIL fusion proteins [54].

Another effective method to obtain trimeric TRAIL is to fuse TRAIL with domains capable of spontaneous trimerization, such as leucine zipper (LZ) [55], tenascin‐C (TNC) [56], the C‐terminal fiber shaft repeat of human adenovirus type 5 (Ad5) fiber protein [57], the triple helix domain of human collagen XVIII [58], the c‐propeptide of α1(I) collagen [59], and the trimer coiled helix domain of human lung surfactant‐associated protein D [60]. Overall, trimeric TRAIL fusion proteins exhibit activity similar to or slightly better than that of native TRAIL in in vitro assays of tumor cell activity. However, the trimeric form of the fusion proteins is more stable and binds zinc ions more tightly [59], resulting in stronger antitumor activity in vivo. The increased molecular weight of fusion TRAILs also results in an extended half‐life.

Among these trimeric fused TRAIL variants, SCB‐313, which is a fusion of TRAIL with the c‐propeptide of α1(I) collagen, has already completed Phase 1 clinical trials in China and Australia (NCT04051112, NCT04123886, NCT03443674, and NCT03869697) for the treatment of malignant peritoneal tumors and malignant pleural effusion. Results from NCT04051112 and NCT03443674 have demonstrated that SCB‐313 exhibits acceptable safety profiles and a reduction in ascites flow rate at therapeutic doses [61]. However, there have been no reports of Phase 2 clinical trials of SCB‐313 to date.

4.2. Promoting the Formation of TRAIL Polymers

Similar to other members of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily (TNFRSF) [10, 62], forming higher order assemblies of DR4 or DR5 based on the trimeric structure has been shown to more effectively activate the receptors and induce significantly amplified apoptosis. This is supported by observations that secondary cross‐linking of FLAG‐tagged TRAIL, achieved through the addition of anti‐FLAG antibodies, exhibits markedly enhanced tumor cell apoptosis compared to native TRAIL [63, 64]. Consequently, it is plausible that the insufficient cross‐linking of sTRAIL may be a contributing factor to its limited antitumor efficacy in clinical trials.

Therefore, constructing polymeric TRAIL becomes an attractive option for enhancing therapeutic efficacy of TRAIL to promote higher order oligomerization of TRAIL receptors (Table 1). The fusion of TRAIL with a hexametric domain of the isoleucine zipper motif, known as ILz(6):TRAIL, has been observed to form hexamers and higher order polymers, resulting in enhanced apoptosis‐inducing activity compared to the trimeric form of TRAIL [65]. Immunoglobulins are natural covalently linked homodimer that can serve as scaffolds for the construction of polymeric TRAIL. For instance, fusion of the heavy‐chain domain 2 (EHD2) of immunoglobulin E (IgE) with scTRAIL resulted in a hexavalent TRAIL with enhanced antitumor activity [67]. Similarly, fusion of scTRAIL to either the light chain, heavy chain, or both chains of an anti‐EGFR IgG antibody produced hexavalent or dodecavalent IgG‐scTRAIL molecules, all of which exhibited increased bioactivity. Notably, dodecavalent scTRAIL demonstrated superior bioactivity compared to the hexavalent IgG‐scTRAIL [68]. Moreover, fusion of the Fc‐part of a human IgG1‐mutein with two scTRAIL‐receptor‐binding domain polypeptides also created a hexavalent scTRAIL‐RBD dimer known as APG350 [77] (with an optimized version named ABBV‐621 [69]), with increased antitumor activity in vitro and in vivo. Encouragingly, ABBV‐621 has advanced to clinical trials. A completed Phase 1 trial (NCT03082209) evaluated its safety, efficacy, and pharmacokinetic profile in patients with previously treated solid tumors or hematologic malignancies. This study demonstrated the acceptable safety and preliminary antitumor effects of ABBV‐621 [78]. Another Phase 1b clinical trial (NCT04570631) is ongoing in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma that aimed to determine the efficacy of ABBV‐621 in combination with bortezomib and dexamethasone [79].

TABLE 1.

Polymeric TRAIL fusion proteins.

| Fusion partner | Name | Polymeric state | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isoleucine zipper motif | ILz(6):TRAIL | Hexamers and higher order polymers | [65] |

| α‐Helical coils from MBD2 and p66α proteins | HexTR | Hexamer | [66] |

| Heavy‐chain domain 2 of IgE | scFv‐EHD2‐scTRAIL | Hexamer | [67] |

| Light chain of anti‐EGFR IgG | LC‐scTRAIL | Hexamer | [68] |

| Heavy chain of anti‐EGFR IgG | HC‐scTRAIL | Hexamer | [68] |

| Light and heavy chains of anti‐EGFR IgG | LC/HC‐scTRAIL | Dodecamer | [68] |

| Fc‐part of a human IgG1‐mutein | APG350 or ABBV‐621 | Hexamer | [69] |

| Multivalent protein scaffold (MV) by adding tailpiece of IgM to IgG Fc | MV‐TRAIL | Polymers | [70] |

| TGF3L peptide | TGF3L‐TRAIL | Polymers | [71] |

| NCTR25 peptide | NCTR25‐TRAIL | Polymers | [72] |

| NCTR25‐TGF3L | NCTR25‐TGF3L‐TRAIL | Polymers | [72] |

| Elastin‐like polypeptides | RGD‐TRAIL‐ELP | Nanoparticles | [73] |

| Ferritin | TRAIL‐ATNCIL4rP | Active trimer nanocage | [74] |

| SnoopTagJr/SnoopDogTag | SnHexaTR | Trimer or hexamer when adding SnoopLigase | [75] |

| Fn14 | Fn14.TRAIL | Adding TWEAK to form oligomer | [76] |

In addition to forming oligomers, some TRAIL fusion proteins can form high‐order assemblies, even reaching nanoscale. Elastin‐like polypeptides (ELPs) are temperature‐sensitive biopolymers derived from human tropoelastin. When fused with TRAIL, the resulting fusion protein can spontaneously assemble into nanoparticles at 37°C with improved apoptosis‐inducing bioactivity [73]. Additionally, TRAIL fused with the triple helical domain of pulmonary surfactant‐associated protein D and ferritin, known for its ability to form a cage‐like supramolecular assembly, produced TRAIL‐ATNC, which formed nanoparticles with prolonged serum half‐life and enhanced tumor targeting [74]. We have reported a series of self‐assembled stable TRAIL polymers, including TGF3L‐TRAIL [71], NCTR25‐TRAIL, and NCTR25‐TGF3L‐TRAIL [72], and their hydrodynamic radius measured by DLS was 30–40 nm on average. These polymers demonstrated significantly enhanced tumor cell‐specific cytotoxicity in vitro, with an LD50 four orders of magnitude lower than sTRAIL in Colo205 cells, and also showed improved in vivo activity compared to recombinant sTRAIL.

Additionally, the polymerization of TRAIL can be achieved by adding enzymes or ligand. The fusion of TRAIL with minimal superglue peptide pairs, such as Snoopligase‐catalyzed SnoopTagJr/SnoopDogTag and SpyStapler‐catalyzed SpyTag/SpyBDTag, resulted in superglue‐fusion TRAIL variants capable of spontaneous trimerization. Upon introduction of Snoopligase or SpyStapler, the trimeric superglue‐fusion TRAIL variants were predominantly crosslinked into hexavalent TRAIL variants, named snHexaTR or spHexaTR [75, 80]. Furthermore, distinct from previously reported fusion proteins, the fusion of TRAIL to fibroblast growth factor‐inducible 14 (Fn14)—a receptor for tumor necrosis factor‐like weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK)—is capable of forming trimers. And this fusion protein and undergoes oligomerization in the presence of TWEAK, resulting in increased activity [76].

In addition to enhanced activity, many polymeric TRAIL fusion proteins have shown increased drug accumulation. For example, hexavalent SnHexaTR demonstrated enhanced tumor uptake (over 2 times) than that of trivalent TRAIL [75]; a TRAIL‐active trimer nanocage (TRAIL‐ATNC) showed approximately 1.5 times higher tumor uptake than that of TRAIL [74]. The self‐assembly nanoparticle RGD‐TRAIL‐ELP exhibited 2.5‐fold higher tumor accumulation than that of RGD‐TRAIL [73].

4.3. Enhancing the Tumor Targeting of TRAIL

As mentioned above, TRAIL has five corresponding receptors. TRAIL triggers cell apoptosis in cancerous cells due to its ligation to agonistic receptors DR4 and DR5, while sparing normal cells due to the competitively inhibition of DcR1 and DcR2 on normal cells [9]. Nevertheless, the systemic administration of TRAIL was trapped by its sequestration by normal cells that overexpress DcRs, leading to limited uptake by tumor cells. Tumor cells can resist to TRAIL through downregulation or increased internalization of DR4 and DR5, or overexpression of DcRs (DcR1 and DcR2) [81]. In addition, some normal cells, such as hepatocytes, can express DR4 and DR5 [82], leading to concerns about TRAIL‐induced hepatotoxicity. Therefore, enhancing the targeting of TRAIL to tumor sites is essential when optimizing TRAIL.

Molecules overexpressed on the surface of tumor cells provide opportunities for the design of targeted TRAIL fusion proteins. For instance, peptides that target the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) [83, 84, 85] or human epidermal growth factor receptor‐2 (HER2) [85, 86] are frequently used in the design of TRAIL fusion proteins. Additionally, the tumor microenvironment is characterized by vigorous neovascularization, which is vital for tumor proliferation, metastasis, and drug resistance. Targeting neovascularization is therefore another effective cancer treatment strategy [87]. Fusion with targeted fragments gives TRAIL the potential to selectively accumulate in tumor tissues, thereby improving therapeutic outcomes and minimizing harm to normal tissues.

4.3.1. Antibody/Antibody Fragment Fusion With TRAIL

Antibodies are a crucial class of targeted cancer therapeutics known for their high specificity and affinity, long half‐life, and the ability to block receptor–ligand interactions. They also mediate complement‐dependent cytotoxicity (CDC), antibody‐dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), and antibody‐dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP) [88]. Therefore, in addition to serving as targeted therapeutics themselves, antibodies have also been reported to be fused with TRAIL to enhance its targeting and efficacy [68, 89, 90] (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

TRAIL fusions with antibody/antibody fragments.

| Fusion partner | Name | Target | Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete antibodies | ||||

| CD19 IgG1 | CD19‐TRAIL | CD19 | Efficiently kills CD19+ tumor cells | [89] |

| Anti‐EGFR huC225 IgG1 | LC‐scTRAIL, HC‐scTRAIL, LC/HC‐scTRAIL | EGFR | Efficiently induces EGFR+ cell death | [68] |

| Anti‐MCSP | TRAIL | MCSP | Potently inhibits outgrowth of melanoma | [90] |

| Antibody fragments | ||||

| EGFR targeted nanobody | ENb‐TRAIL | EGFR | Induces apoptosis in cancer cells insensitive to TRAIL | [83] |

| Diabody of anti‐EGFR | Db‐scTRAIL | EGFR | Shows potent and long‐lasting tumor response | [84] |

| scFvhu225 | scFvhu225‐Fc‐scTRAIL | EGFR | Almost complete tumor remission but early regrowth | [85] |

| 4D5 scFv of anti‐HER2 | 4D5 scFv‐TRAIL | HER2 | Specifically targets to the surface of HER2‐overexpressing tumor cells and inhibits cell growth | [86] |

| scFv3‐43 | scFv3‐43‐Fc‐scTRAIL | HER3 | Stable tumor remission | [85] |

| scFv323/A3hu3 | scFv323/A3hu3‐Fc‐scTRAIL | EpCAM | Partial tumor regression and fast regrowth | [85] |

| Anti‐Kv10.1 nanobody | VHH‐D9‐scTRAIL | Kv10.1 | Induces apoptosis in Kv10.1+ tumor cells | [91] |

| scFv:G28‐5 | scFv:G28‐TRAIL | CD40 | Enhances apoptosis induction and stimulates DC maturation | [92] |

| scFv:lαhCD70 | scFv:lahCD70‐TNC‐TRAIL | CD70 | Triggers cell death 10‐ to 100‐fold more efficiently in CD70 positive cells | [93] |

| scFvCD33 | scFvCD33:sTRAIL | CD33 | Induces CD33‐targeted apoptosis and shows bystander activity toward CD33− tumor cells | [94] |

| Anti‐CD38 scFv Diabody | IL2‐αCD38‐αCD38‐scTRAIL | CD38, IL‐2R | Selectively kills CD138+ cells | [95] |

| scFvCD20 | scFvCD20‐sTRAIL | CD20 | scFvCD20‐sTRAIL secreting mesenchymal stem cells migrates to the tumor site and significantly inhibits the tumor growth | [96] |

| scFvCD7 | scFvCD7:sTRAIL | CD7 | Induces potent apoptosis in CD7+ malignant T cells and induces bystander apoptosis of CD7− tumor cells | [97] |

| scFvCD47 | Anti‐CD47:TRAIL | CD47 | Enhances RTX‐induced B‐NHL cell phagocytosis by granulocytes | [98] |

| scFvPD‐L1 | Anti‐PD‐L1:TRAIL | PD‐L1 | Blocks PD‐1/PD‐L1 interaction, enhances T cell activation, and sensitizes cancer cells to TRAIL | [99] |

| scFvM58 | scFvM58‐sTRAIL | MRP‐3 | Induces apoptosis toward MRP3+ GBM cells | [100] |

However, the large molecular weight of full‐length antibodies makes it challenging for constructing fusion proteins. The single‐chain variable fragments (scFvs) of antibodies (26–28 kDa) are more popular in the construction of fusion proteins. ScFvs incorporate the complete antigen‐binding site of an antibody by combining the VH (variable domain of immunoglobulin heavy chain) and VL (variable domain of immunoglobulin light chain) connected with a flexible peptide linker [101], making it a more compact size and comparable antigen‐binding specificity and high affinity to complete antibodies. In recent years, there have been numerous TRAIL fusion proteins constructed using scFvs (Table 2). Alongside scFvs, the diabody (a variant of scFv by reducing the linker between VH and VL) has also been employed to construct dimerized targeted TRAIL [84]. Furthermore, nanobodies, another smaller antibody fragments with the VH from camelids antibodies, are also utilized as fusion partners for TRAIL [83, 91].

The fusion of antibodies or antibody fragments with TRAIL led to multifunctional TRAIL fusion proteins, which exhibit enhanced tumor selectivity and reduced off‐target effects. Furthermore, certain antibodies could inhibit cell prosurvival signaling [83, 99] or stimulate dendritic cells maturation [92], thereby synergistically enhancing the antitumor efficacy with TRAIL. Moreover, the high affinity of antibodies allows for temporary anchoring of TRAIL to the cell membrane, mimicking membrane‐bound TRAIL and augmenting its activity. Additionally, the scFv‐TRAIL fusion protein demonstrates a so‐called “bystander effect” by eliminating tumor cells without the specific antigen in close proximity to target cells through a paracrine‐like mechanism [92, 94, 97]. Table 2 presents a summary of TRAIL fusions with their targets and fused antibody/antibody fragments in recent studies.

4.3.2. Peptides Fusion With TRAIL

In addition to antibodies, small peptides/ligands that recognize tumor‐associated antigens/receptors have been utilized as fusion partners for TRAIL to enhance the tumor‐homing capabilities of TRAIL and inhibit tumor growth through alternative molecular pathways. “Z‐domain” or “affibody” is a small recognition molecule derived from domain B of staphylococcal protein A [102], which shows excellent tumor penetration and precisely targets some cancer cells with specific overexpressed molecular signatures [103]. For instance, the fusion of PDGFRβ‐specific affibody ZPDGFRβ with ABD‐TRAIL has been demonstrated to effectively target tumor cells and PDGFRβ‐positive pericytes on tumor microvessels, facilitating the homing of TRAIL to the tumor site [104]. Similarly, the antiangiogenic synthetic peptide SRHTKQRHTALH has been shown to confer the TRAIL variant with the ability to target vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) [105]. Peptides from RGD and NGR families have also been extensively exploited to enhance the penetration of various compounds by binding to integrins αVβ3 and αVβ5 [106], which are highly expressed in both tumor cells and the tumor vasculature. Table 3 displays the peptides that have been fused with TRAIL in recent studies.

TABLE 3.

TRAIL fusions with targeting small peptides.

| Fusion partner | Name | Target | Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL‐2 | IL2‐TRAIL | IL2 receptor | Induces higher apoptosis in CD25+ cells | [107] |

| IL4 receptor‐binding peptides (IL4rPs) | TRAIL‐ATNCIL4rP nanocages | IL4 receptor | Enhanced in vivo stability and antitumor efficacy | [74] |

| MUC16‐binding domain of mesothelin | Meso64‐TR3 | MUC16 | More potent than TR3 in vitro and in vivo in MUC16+ ovarian cancer | [108] |

| CD19L | CD19L‐TRAIL | CD19 | Potent in vivo antileukemic activity at nontoxic fmol/kg dose levels and slower in vivo elimination than TRAIL | [109] |

| HER2‐specific affibody ZHER2:342 | TRAIL‐ Affibody | HER2 | Increased tumor‐homing ability and antitumor efficiency than those of TRAIL | [110] |

| PDGFRβ‐specific affibody ZPDGFRβ | Z‐ABD‐TRAIL | PDGFRβ | Engagement of PDGFRβ‐expressing pericytes on tumor microvessels and long‐lasting (> 72 h) tumor‐killing ability | [104] |

| RGR peptide (CRGRRST) | RGR‐TRAIL | Not clear | Improved the tumor uptake and antitumor effects of TRAIL in DR‐overexpressing colorectal cancer cells | [111] |

| NGR and (or) RGD | RGD‐TRAIL, TRAIL‐NGR, RGD‐TRAIL‐NGR | Integrin ανβ3 | Induces more potent apoptosis in cells insensitive to TRAIL | [106] |

| iRGD (CRGDKGPDC) | DR5‐B‐iRGD | Integrin αvβ3 | Penetrates U‐87 tumor spheroids much faster with enhanced antitumor effect than DR5‐B | [112] |

| Antiangiogenic synthetic peptide SRHTKQRHTALH | SRH‐DR5‐B | VEGFR2 | Shows higher efficacy than DR5‐B in 3D tumor spheroids of the HT‐29 and U‐87 cell lines | [105] |

| RKRKKSR peptides derived from VEGFA | AD‐O51.4 | VEGF receptors | Triggers apoptosis in TRAIL‐resistant cancer cells | [113, 114] |

| Vasostatin | VAS‐TRAIL | Not given | Induces apoptosis in endothelial cells | [115] |

4.4. Arming Immune Cells With TRAIL

TRAIL, expressed on the surface of various innate and adaptive immune cells [116, 117, 118, 119, 120], plays a pivotal role in tumor immune surveillance [6]. It collaborates with FasL and perforin to exert cytotoxic effects against tumor cells [3]. However, the substantial expression of TRAIL on immune cells typically requires stimuli, such as interferons [116, 117, 118, 119] or interleukins [120], which limit the apoptotic potential of endogenous TRAIL against tumor cells. Moreover, immune cells express both the membrane‐bound and soluble forms of TRAIL, yet studies have demonstrated that the membrane‐bound TRAIL exhibits higher cytotoxic activity than its soluble counterpart [51, 52]. Consequently, immobilizing recombinant sTRAIL on the membrane of immune cells is an effective strategy to enhance the antitumor efficacy of both the immune cells and the recombinant soluble TRAIL.

T cells are pivotal in the immune response against tumors, characterized by high expression levels of CD3 and CD7. However, resting T cells expressed relatively lower levels of TRAIL. Fusion of TRAIL with anti‐CD7 or anti‐CD3 antibodies facilitates its binding to the resting T cell surface, thereby converting TRAIL into a mimic membrane‐bound form [121]. Especially for anti‐CD3‐TRAIL, the anti‐CD3 component can simultaneously activate resting T cells, endowing them with intrinsic cytotoxic effector activity of T cells and leading to granzyme/perforin‐mediated tumor cell lysis. Consequently, anti‐CD3‐TRAIL concurrently enhances the tumor‐killing capabilities of resting T cells and TRAIL [121]. Similarly, neutrophils, which are more abundant than T cells in the circulatory system, also can be equipped with TRAIL. The fusion of anti‐CLL1 with TRAIL is proposed to facilitate the anchoring of TRAIL to the neutrophil surface, thereby enhancing its cytotoxicity against tumor cells and simultaneously increasing the ADCC effect of antibody drugs [122].

Although these fusion proteins are also the fusion of antibodies and TRAIL, they differ from the previously described TRAIL fusion proteins designed to enhance targeting tumor tissues. The activity of these fusion proteins is significantly enhanced only when they are co‐incubated with T cells or granulocytes.

4.5. Prolonging Half‐Life of TRAIL

The serum half‐life of recombinant sTRAIL is short (3–5 min in rodents, 23–31 min in nonhuman primates [123], and 0.56–1.02 h in Phase 1 trials in patients [38]), which impedes its clinical application.

The human serum albumin (HSA) and the albumin‐binding domain (ABD) are commonly utilized fusion partners to prolong the plasma half‐life of TRAIL and enhance its bioavailability, because the HSA has an exceptionally long half‐life of ~19 days [124]. The fusion of FLAG‐TNC‐TRAIL with HSA has proven to be an effective approach, as the half‐life of this fusion TRAIL in mice is increased to ~15 h, resulting in enhanced antitumor activity in vivo [125]. Linking HSA with TRAIL via a bifunctional PEG derivative can also improve the pharmacokinetic profiles of TRAIL, resulting in a 27‐fold increase in half‐life in mice [126]. Additionally, genetically fusing TRAIL with the ABD, a small domain that binds to albumin, has been found to significantly prolong the plasma half‐life of TRAIL by 40–50 times, leading to enhanced antitumor effects [127].

IgG molecules, particularly IgG1, IgG2, and IgG4, have exceptionally long half‐lives up to ∼18–21 days [128]. The extended half‐life of IgG is attributed to its recycling process involving Fc region binding to FcRn [124]. Thus, fusion to an Fcγ region provides therapeutic proteins with the long half‐life properties of immunoglobulins [129]. For instance, fusion of the Fcγ region of IgG1 to TRAIL significantly extends its half‐life by more than 10‐fold and enhances its antitumor efficacy in vivo by approximately 5‐fold. Additionally, the Fc region confers oligomeric ability to TRAIL [130]. Furthermore, the fusion of immunoglobulin‐binding domains (IgBDs) to TRAIL allows for binding to Fab fragments of IgG. IgBD‐TRAIL exhibits a significantly longer serum half‐life compared to TRAIL, with an increase of 50–60‐fold, as well as a four‐ to seven‐fold increase in tumor uptake and more than 10 times greater in vivo antitumor effect compared to TRAIL [131].

4.6. Overcoming Resistance of Tumor Cells to TRAIL

Cancer cells have developed diverse mechanisms to resist apoptosis triggered by TRAIL [132]. Dysregulation of TRAIL receptors, such as decreased expression of DR4 and DR5 [133], increased internalization of DR4 and DR5 [134], and overexpression of DcR1, DcR2, or OPG were observed to correlate with TRAIL resistance [9]. Upregulation of antiapoptotic proteins also plays a vital role in TRAIL resistance. Upregulation of c‐FLIP is one of the main mechanisms for cancer cells escaping from TRAIL‐induced apoptosis [135]. c‐FLIP can bind to FADD but is unable to activate caspases and thus prevents effective DISC formation [81] (Figure 1). In intrinsic apoptosis pathway, antiapoptotic proteins of the BCL‐2 family, specifically BCL‐XL, can compete with BAX for binding to tBID, whereas BCL‐2 can inhibit tBID translocating into the mitochondrial outer membrane (Figure 1). Overexpression of BCL‐XL or BCL‐2 is associated with tumor cells' resistance to TRAIL [136]. IAP family proteins regulate both the extrinsic and intrinsic pathways (Figure 1). XIAP has been shown to interact with caspases 3, 7, and 9 and inhibits their activities, whereas cellular inhibitor of apoptosis protein (cIAP)1 and cIAP2 polyubiquitinates caspases 3 and 7, leading to their degradation. XIAP, cIAP1, and cIAP2 are frequently overexpressed in a number of cancers and revolved in cell death resistance [137].

It was found that decreased levels of phosphorylated Akt (p‐Akt) led to reduced expression of c‐FLIP, thereby alleviating TRAIL resistance in cancer cells. Iron superoxide dismutase (FeSOD) was shown to decrease p‐Akt levels. Consequently, the fusion protein sTRAIL:FeSOD resulted in the downregulation of both p‐Akt and c‐FLIP, thereby promoting apoptosis in TRAIL‐resistant cells [138]. AD‐O57.4 and AD‐O57.5 are fusion proteins composed of TRAIL and the BH3 domain of BID connected by distinct linkers. Both constructs have demonstrated the ability to induce apoptosis in cell lines that were initially resistant to TRAIL [139]. The IAPs impede the activation of downstream caspases, and the mitochondrial protein SMAC/Diablo can eliminate the inhibitory effects of XIAP on caspase activation [140]. A fusion protein, AD‐O53.2, was designed to combine sTRAIL with a peptide derived from SMAC/Diablo protein (AVPIAQKP) in order to facilitate the delivery of the SMAC/Diablo peptide to the cytoplasm for the purpose of inhibiting XIAP and overcoming TRAIL resistance [141]. Similarly, in another study, the 10 aa in the N‐terminal of the sTRAIL was replaced with RRRRRR (a cell penetrating peptide polyarginine) and AVPI (the N‐terminal and binding site of SMAC). The resulted protein, named R6ST, exhibited improved affinity to DR4 and DR5, and significantly decreased XIAP intracellular concentration in PANC‐1 cells compared with sTRAIL [142]. The fusion protein AD‐O56.9 also demonstrated significant tumor regression in mouse xenograft models of TRAIL‐resistant tumors. It consists of sTRAILand the cationic, alpha‐helical (KLAKLAK) 2 antimicrobial peptide, which is known for its potent ability to induce apoptosis by disrupting the mitochondrial membrane [143]. Another fusion protein SAC‐TRAIL consists of TRAIL and SAC protein. SAC is the core domain (aa137–195) as well as the effector domain of prostate apoptosis response‐4, which was identified as essential for TRAIL‐induced apoptosis [144]. The two functional components of SAC‐TRAIL demonstrated synergistic effects, resulting in enhanced antitumor efficacy compared to TRAIL alone [145].

4.7. Other TRAILFusions

There are also constructs of TRAIL fusions that demonstrated higher antitumor efficacy than native TRAIL without accurate mechanism, for example, the antibacterial peptide CM4 fused with TRAIL induced more potent apoptosis than that of TRAIL [146]. Another chimeric protein Annexin V‐TRAIL triggered robust apoptosis in A549 cells and demonstrated significant inhibition of tumor growth in A549 xenografts, which is resistant to TRAIL [147]. Additionally, TRAIL‐Mu3, a mutant form of wild‐type TRAIL, is not a typical TRAIL fusion protein. The 114–121 amino acid sequence “VRERGPQR” of TRAIL was mutated into a membrane‐penetrating peptide‐like amino acid sequence “RRRRRRRR.” This modification resulted in increased affinity for the cell membrane and enhanced proapoptotic potential [148].

5. Conclusion and Perspective

TRAIL is an endogenous apoptosis‐inducing ligand that specifically kills cancer cells with little harm to normal cells, which makes it a promising molecule for cancer treatment. However, clinical trials of sTRAIL showed limited efficacy, due to its relatively short half‐life, decreased protein stability, insufficient tumor accumulation, and resistance exhibited by cancer cells. An increasing number of TRAIL fusion proteins have been constructed over the past few years, and potent approaches have been successfully employed to create multifunctional TRAIL. Notably, some of them have shown sufficient promise to advance into clinical trials [78, 79, 149, 150]. Nevertheless, significant challenges remain in TRAIL fusion protein development.

Hepatotoxicity has been a major limitation for the clinical use of TNF superfamily members [151]. Certain versions of tagged TRAIL, such as His‐TRAIL [152], FLAG‐TRAIL, or LZ TRAIL [153], have been reported to induce apoptosis in human hepatocytes. This hepatotoxicity has been attributed to the self‐aggregation of tagged TRAIL due to the lack of Zn2+ ions and reduced solubility [152], or to the artificial receptor cross‐linking by the addition of FLAG antibody [153], which induces a stronger signal through the DRs in hepatocytes. Consistent with these observations, in our previous study [72], we observed fatal hepatotoxicity in BALB/c nude mice administered a high dose (40 mg/kg) of His‐TRAIL. In addition, in a nonclinical toxicology study, recombinant human TRAIL (without any tag) also demonstrated hepatotoxicity in cynomolgus monkeys. Researchers determined that cross‐species antitherapeutic antibodies in cynomolgus monkeys crosslinked recombinant human TRAIL, inducing the aggregation of hepatocyte DRs and amplifying downstream signaling leading to apoptosis [154]. Similarly, in a Phase 1 study of TAS266, a tetravalent agonistic nanobody targeting the DR5 receptor, three patients developed TAS266‐related hepatotoxicity. The possible cause is suspected to be related to the multivalence of the molecule, which efficiently enhances DR5 clustering [155].

Therefore, minimizing hepatoxicity is crucial in the TRAIL fusion protein design, particularly ensuring that potency and valency enhancement should not be pursued at the expense of safety. One approach to attenuate hepatotoxicity is to enhance the tumor‐targeting specificity of TRAIL fusion proteins, as detailed in the text. Alternatively, optimized delivery systems can be employed. For example, therapeutic engineered neural stem cells were developed to be implanted in the resection cavity of glioblastoma in mice, offering a continuous and concentrated local delivery of sTRAIL, thus reducing its nonselective targeting [156]. In summary, it is advisable to concurrently evaluate the hepatotoxicity of TRAIL fusion proteins alongside their antitumor activity.

Notably, the existence of resistance of tumor cells against TRAIL fusion proteins should be considered during the design and development of TRAIL fusion proteins. Combination with other drugs is a common strategy to overcome resistance. For example, the combination of cyclopamine and CPT exhibited synergistic effects on inhibition, proliferation, and inducing apoptosis in myeloma cells [157]. For ABBV‐621, researchers have demonstrated that the inherent resistance of cancer cells to ABBV‐621 treatment can be overcome in combination with chemotherapeutics or with selective inhibitors of BCL‐XL, A‐1331852 [69]. Furthermore, an ongoing Phase 1b clinical trial (NCT04570631) is evaluating the efficacy of ABBV‐621 in combination with bortezomib and dexamethasone in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma [79]. It is also necessary to identify appropriate biomarkers for patients to determine their suitability for TRAIL treatment and to select the most effective sensitizers for TRAIL fusion proteins to achieve better therapeutic efficacy. In addition to combination with TRAL sensitizers, meticulously designed delivery systems can also enhance tumor cell sensitivity to TRAIL. For example, a nanocage was designed to deliver TRAIL in its native‐like trimeric structure, along with doxorubicin, which re‐sensitizes TRAIL‐resistant tumor cells [158]. Another nanoplatform, named CPT MV, is a novel reactive oxygen species (ROS)‐dependent TRAIL‐sensitizing nanoplatform, featuring a Ce6‐PLGA core and a TRAIL‐modified cell membrane shell. Upon laser irradiation, it generates ROS in targeted cancer cells, improving DR5 expression, triggering cytochrome c release from mitochondria, and strengthening TRAIL‐induced apoptosis [159]. Furthermore, considering that DcRs can competitively block TRAIL's interaction with DR4 and DR5, potentially conferring resistance to TRAIL in tumor cells [160, 161], and that DcR2 may induce non‐apoptotic signaling pathways [22], using DR4‐specific [162] or DR5‐specific [163, 164] TRAIL variants as the main body for fusion could represent a viable option [93].

We note that while a small portion of fusion protein designs utilize computer‐aided design, the majority still rely on empirical screening approaches with high uncertainty. Unexpected outcomes, including improper folding, reduced biological activity, and unforeseen toxicity, frequently arise, highlighting our limited understanding of the structure–function relationships in these fusion proteins [165]. Nowadays, computational methods have revolutionized protein engineering, allowing a diverse set of biocomputing capabilities such as prediction of protein three‐dimensional models, characterization of protein–protein interactions, and the molecular dynamics simulations [166]. We believe that prevalidation of fusion protein conformational state and overall quality through biocomputing methods will make the design of TRAIL fusion proteins more efficient and rational.

Overall, we are inclined to believe that an optimal strategy for engineering TRAIL fusion proteins should ideally address all the three issues: pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and resistance. Among these, the most critical goal should be increasing the oligomerization of recombinant TRAIL without the formation of aggregates. Other desirable attributes might encompass improved tumor targeting, the ability to overcome resistance, and prolonged half‐life. It is imperative to emphasize that vigilance on hepatotoxicity should accompany the entire process, from the initial design to the validation of antitumor activity.

Notwithstanding a number of challenges in the way, TRAIL remains one of the most promising approaches for cancer treatment. Rational design of fusion proteins, or further development based on this approach, could potentially provide opportunities for the clinical use of TRAIL‐based therapeutics.

Author Contributions

Yan Wang: conceptualization (lead), data curation (equal), funding acquisition (lead), visualization (equal), writing – original draft (lead), writing – review and editing (lead). Xin Qian: data curation (equal), visualization (equal), writing – original draft (equal), writing – review and editing (equal). Yubo Wang: data curation (equal). Caiyuan Yu: data curation (equal), writing – review and editing (supporting). Li Feng: data curation (equal), writing – review and editing (supporting). Xiaoyan Zheng: data curation (equal). Yaya Wang: data curation (equal). Qiuhong Gong: conceptualization (supporting), supervision (lead), writing – review and editing (supporting).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82104255), Youth Foundation of the Open University of China (Q23A0015), and Natural Science Foundation of Beijing Municipality (7162134).

Yan Wang and Xin Qian contributed equally to this work.

Data Availability Statement

The authors have nothing to report.

References

- 1. Dianat‐Moghadam H., Heidarifard M., Mahari A., et al., “TRAIL in Oncology: From Recombinant TRAIL to Nano‐ and Self‐Targeted TRAIL‐Based Therapies,” Pharmacological Research 155 (2020): 104716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thapa B., Kc R., and Uludag H., “TRAIL Therapy and Prospective Developments for Cancer Treatment,” Journal of Controlled Release 326 (2020): 335–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Takeda K., Hayakawa Y., Smyth M. J., et al., “Involvement of Tumor Necrosis Factor‐Related Apoptosis‐Inducing Ligand in Surveillance of Tumor Metastasis by Liver Natural Killer Cells,” Nature Medicine 7 (2001): 94–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bodmer J. L., Meier P., Tschopp J., and Schneider P., “Cysteine 230 Is Essential for the Structure and Activity of the Cytotoxic Ligand TRAIL,” Journal of Biological Chemistry 275 (2000): 20632–20637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wajant H., “Molecular Mode of Action of TRAIL Receptor Agonists‐Common Principles and Their Translational Exploitation,” Cancers (Basel) 11 (2019): 954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pimentel J. M., Zhou J. Y., and Wu G. S., “The Role of TRAIL in Apoptosis and Immunosurveillance in Cancer,” Cancers (Basel) 15 (2023): 2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chan F. K., “Three Is Better Than One: Pre‐Ligand Receptor Assembly in the Regulation of TNF Receptor Signaling,” Cytokine 37 (2007): 101–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schneider P., Thome M., Burns K., et al., “TRAIL Receptors 1 (DR4) and 2 (DR5) Signal FADD‐Dependent Apoptosis and Activate NF‐kappaB,” Immunity 7 (1997): 831–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jong K. X. J., Mohamed E. H. M., and Ibrahim Z. A., “Escaping Cell Death via TRAIL Decoy Receptors: A Systematic Review of Their Roles and Expressions in Colorectal Cancer,” Apoptosis 27 (2022): 787–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vanamee E. S. and Faustman D. L., “The Benefits of Clustering in TNF Receptor Superfamily Signaling,” Frontiers in Immunology 14 (2023): 1225704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kischkel F. C., Lawrence D. A., Chuntharapai A., Schow P., Kim K. J., and Ashkenazi A., “Apo2L/TRAIL‐Dependent Recruitment of Endogenous FADD and Caspase‐8 to Death Receptors 4 and 5,” Immunity 12 (2000): 611–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Oh Y. T. and Sun S. Y., “Regulation of Cancer Metastasis by TRAIL/Death Receptor Signaling,” Biomolecules 11 (2021): 499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schug Z. T., Gonzalvez F., Houtkooper R. H., Vaz F. M., and Gottlieb E., “BID Is Cleaved by Caspase‐8 Within a Native Complex on the Mitochondrial Membrane,” Cell Death and Differentiation 18 (2011): 538–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Johnstone R. W., Frew A. J., and Smyth M. J., “The TRAIL Apoptotic Pathway in Cancer Onset, Progression and Therapy, Nature Reviews,” Cancer 8 (2008): 782–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Newton K., Wickliffe K. E., Dugger D. L., et al., “Cleavage of RIPK1 by Caspase‐8 Is Crucial for Limiting Apoptosis and Necroptosis,” Nature 574 (2019): 428–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mompean M., Li W., Li J., et al., “The Structure of the Necrosome RIPK1‐RIPK3 Core, a Human Hetero‐Amyloid Signaling Complex,” Cell 173 (2018): 1244–1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Henry C. M. and Martin S. J., “Caspase‐8 Acts in a Non‐Enzymatic Role as a Scaffold for Assembly of a Pro‐Inflammatory “FADDosome” Complex Upon TRAIL Stimulation,” Molecular Cell 65 (2017): 715–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Varfolomeev E., Maecker H., Sharp D., et al., “Molecular Determinants of Kinase Pathway Activation by Apo2 Ligand/Tumor Necrosis Factor‐Related Apoptosis‐Inducing Ligand,” Journal of Biological Chemistry 280 (2005): 40599–40608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Davidovich P., Higgins C. A., Najda Z., Longley D. B., and Martin S. J., “cFLIP(L) Acts as a Suppressor of TRAIL‐ and Fas‐Initiated Inflammation by Inhibiting Assembly of Caspase‐8/FADD/RIPK1 NF‐kappaB‐Activating Complexes,” Cell Reports 42 (2023): 113476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lafont E., Kantari‐Mimoun C., Draber P., et al., “The Linear Ubiquitin Chain Assembly Complex Regulates TRAIL‐Induced Gene Activation and Cell Death,” EMBO Journal 36 (2017): 1147–1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Azijli K., Weyhenmeyer B., Peters G. J., de Jong S., and Kruyt F. A., “Non‐Canonical Kinase Signaling by the Death Ligand TRAIL in Cancer Cells: Discord in the Death Receptor Family,” Cell Death and Differentiation 20 (2013): 858–868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yang J., LeBlanc F. R., Dighe S. A., et al., “TRAIL Mediates and Sustains Constitutive NF‐kappaB Activation in LGL Leukemia,” Blood 131 (2018): 2803–2815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wong S. H. M., Kong W. Y., Fang C. M., et al., “The TRAIL to Cancer Therapy: Hindrances and Potential Solutions,” Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 143 (2019): 81–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Belch A., Sharma A., Spencer A., et al., “A Multicenter Randomized Phase II Trial of Mapatumumab, a TRAIL‐R1 Agonist Monoclonal Antibody, in Combination With Bortezomib in Patients With Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma (MM),” Blood 116 (2010): 5031. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ciuleanu T., Bazin I., Lungulescu D., et al., “A Randomized, Double‐Blind, Placebo‐Controlled Phase II Study to Assess the Efficacy and Safety of Mapatumumab With Sorafenib in Patients With Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma,” Annals of Oncology 27 (2016): 680–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. von Pawel J., Harvey J. H., Spigel D. R., et al., “Phase II Trial of Mapatumumab, a Fully Human Agonist Monoclonal Antibody to Tumor Necrosis Factor‐Related Apoptosis‐Inducing Ligand Receptor 1 (TRAIL‐R1), in Combination With Paclitaxel and Carboplatin in Patients With Advanced Non‐Small‐Cell Lung Cancer,” Clinical Lung Cancer 15 (2014): 188–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Younes A., Vose J. M., Zelenetz A. D., et al., “A Phase 1b/2 Trial of Mapatumumab in Patients With Relapsed/Refractory Non‐Hodgkin's Lymphoma,” British Journal of Cancer 103 (2010): 1783–1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Trarbach T., Moehler M., Heinemann V., et al., “Phase II Trial of Mapatumumab, a Fully Human Agonistic Monoclonal Antibody That Targets and Activates the Tumour Necrosis Factor Apoptosis‐Inducing Ligand Receptor‐1 (TRAIL‐R1), in Patients With Refractory Colorectal Cancer,” British Journal of Cancer 102 (2010): 506–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fuchs C. S., Fakih M., Schwartzberg L., et al., “TRAIL Receptor Agonist Conatumumab With Modified FOLFOX6 Plus Bevacizumab for First‐Line Treatment of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Randomized Phase 1b/2 Trial,” Cancer 119 (2013): 4290–4298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kindler H. L., Richards D. A., Garbo L. E., et al., “A Randomized, Placebo‐Controlled Phase 2 Study of Ganitumab (AMG 479) or Conatumumab (AMG 655) in Combination With Gemcitabine in Patients With Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer,” Annals of Oncology 23 (2012): 2834–2842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cheng A. L., Kang Y. K., He A. R., et al., “Safety and Efficacy of Tigatuzumab Plus Sorafenib as First‐Line Therapy in Subjects With Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Phase 2 Randomized Study,” Journal of Hepatology 63 (2015): 896–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Forero‐Torres A., Infante J. R., Waterhouse D., et al., “Phase 2, Multicenter, Open‐Label Study of Tigatuzumab (CS‐1008), a Humanized Monoclonal Antibody Targeting Death Receptor 5, in Combination With Gemcitabine in Chemotherapy‐Naive Patients With Unresectable or Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer,” Cancer Medicine 2 (2013): 925–932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Reck M., Krzakowski M., Chmielowska E., et al., “A Randomized, Double‐Blind, Placebo‐Controlled Phase 2 Study of Tigatuzumab (CS‐1008) in Combination With Carboplatin/Paclitaxel in Patients With Chemotherapy‐Naive Metastatic/Unresectable Non‐Small Cell Lung Cancer,” Lung Cancer 82 (2013): 441–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Baron A. D., O'Bryant C. L., Choi Y., Ashkenazi A., Royer‐Joo S., and Portera C. C., “Phase Ib Study of Drozitumab Combined With Cetuximab (CET) Plus Irinotecan (IRI) or With FOLFIRI ± Bevacizumab (BV) in Previously Treated Patients (Pts) With Metastatic Colorectal Cancer (mCRC),” Journal of Clinical Oncology 29 (2011): 3581. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Merchant M. S., Geller J. I., Baird K., et al., “Phase I Trial and Pharmacokinetic Study of Lexatumumab in Pediatric Patients With Solid Tumors,” Journal of Clinical Oncology 30 (2012): 4141–4147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wakelee H. A., Patnaik A., Sikic B. I., et al., “Phase I and Pharmacokinetic Study of Lexatumumab (HGS‐ETR2) Given Every 2 Weeks in Patients With Advanced Solid Tumors,” Annals of Oncology 21 (2010): 376–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sharma S., de Vries E. G., Infante J. R., et al., “Safety, Pharmacokinetics, and Pharmacodynamics of the DR5 Antibody LBY135 Alone and in Combination With Capecitabine in Patients With Advanced Solid Tumors,” Investigational New Drugs 32 (2014): 135–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Herbst R. S., Eckhardt S. G., Kurzrock R., et al., “Phase I Dose‐Escalation Study of Recombinant Human Apo2L/TRAIL, a Dual Proapoptotic Receptor Agonist, in Patients With Advanced Cancer,” Journal of Clinical Oncology 28 (2010): 2839–2846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Soria J. C., Smit E., Khayat D., et al., “Phase 1b Study of Dulanermin (Recombinant Human Apo2L/TRAIL) in Combination With Paclitaxel, Carboplatin, and Bevacizumab in Patients With Advanced Non‐Squamous Non‐Small‐Cell Lung Cancer,” Journal of Clinical Oncology 28 (2010): 1527–1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Soria J. C., Mark Z., Zatloukal P., et al., “Randomized Phase II Study of Dulanermin in Combination With Paclitaxel, Carboplatin, and Bevacizumab in Advanced Non‐Small‐Cell Lung Cancer,” Journal of Clinical Oncology 29 (2011): 4442–4451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ouyang X., Shi M., Jie F., et al., “Phase III Study of Dulanermin (Recombinant Human Tumor Necrosis Factor‐Related Apoptosis‐Inducing Ligand/Apo2 Ligand) Combined With Vinorelbine and Cisplatin in Patients With Advanced Non‐small‐Cell Lung Cancer,” Investigational New Drugs 36 (2018): 315–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cheah C. Y., Belada D., Fanale M. A., et al., “Dulanermin With Rituximab in Patients With Relapsed Indolent B‐Cell Lymphoma: An Open‐Label Phase 1b/2 Randomised Study,” Lancet Haematology 2 (2015): e166–e174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wainberg Z. A., Messersmith W. A., Peddi P. F., et al., “A Phase 1B Study of Dulanermin in Combination With Modified FOLFOX6 Plus Bevacizumab in Patients With Metastatic Colorectal Cancer,” Clinical Colorectal Cancer 12 (2013): 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Belada D., Mayer J., Czuczman M. S., Flinn I. W., Durbin‐Johnson B., and Bray G. L., “Phase II Study of Dulanermin Plus Rituximab in Patients With Relapsed Follicular Non‐Hodgkin's Lymphoma (NHL),” Journal of Clinical Oncology 28 (2010): 8104. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Snajdauf M., Havlova K., J. Vachtenheim, Jr. , et al., “The TRAIL in the Treatment of Human Cancer: An Update on Clinical Trials,” Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences 8 (2021): 628332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Geng C., Hou J., Zhao Y., et al., “A Multicenter, Open‐Label Phase II Study of Recombinant CPT (Circularly Permuted TRAIL) Plus Thalidomide in Patients With Relapsed and Refractory Multiple Myeloma,” American Journal of Hematology 89 (2014): 1037–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hou J., Qiu L., Zhao Y., et al., “A Phase1b Dose Escalation Study of Recombinant Circularly Permuted TRAIL in Patients With Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma,” American Journal of Clinical Oncology 41 (2018): 1008–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Leng Y., Qiu L., Hou J., et al., “Phase II Open‐Label Study of Recombinant Circularly Permuted TRAIL as a Single‐Agent Treatment for Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma,” Chinese Journal of Cancer 35 (2016): 86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Xia Z., Leng Y., Fang B., et al., “Aponermin or Placebo in Combination With Thalidomide and Dexamethasone in the Treatment of Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma (CPT‐MM301): ARandomised, Double‐Blinded, Placebo‐Controlled, Phase 3 Trial,” BMC Cancer 23 (2023): 980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Duiker E. W., Dijkers E. C., Lambers Heerspink H., et al., “Development of a Radioiodinated Apoptosis‐Inducing Ligand, rhTRAIL, and a Radiolabelled Agonist TRAIL Receptor Antibody for Clinical Imaging Studies,” British Journal of Pharmacology 165 (2012): 2203–2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Vanamee E. S. and Faustman D. L., “On the TRAIL of Better Therapies: Understanding TNFRSF Structure‐Function,” Cells 9 (2020): 764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wajant H., Moosmayer D., Wuest T., et al., “Differential Activation of TRAIL‐R1 and −2 by Soluble and Membrane TRAIL Allows Selective Surface Antigen‐Directed Activation of TRAIL‐R2 by a Soluble TRAIL Derivative,” Oncogene 20 (2001): 4101–4106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hymowitz S. G., O'Connell M. P., Ultsch M. H., et al., “A Unique Zinc‐Binding Site Revealed by a High‐Resolution X‐Ray Structure of Homotrimeric Apo2L/TRAIL,” Biochemistry 39 (2000): 633–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Schneider B., Munkel S., Krippner‐Heidenreich A., et al., “Potent Antitumoral Activity of TRAIL Through Generation of Tumor‐Targeted Single‐Chain Fusion Proteins,” Cell Death & Disease 1 (2010): e68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rozanov D. V., Savinov A. Y., Golubkov V. S., et al., “Engineering a Leucine Zipper‐TRAIL Homotrimer With Improved Cytotoxicity in Tumor Cells,” Molecular Cancer Therapeutics 8 (2009): 1515–1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Berg D., Lehne M., Muller N., et al., “Enforced Covalent Trimerization Increases the Activity of the TNF Ligand Family Members TRAIL and CD95L,” Cell Death and Differentiation 14 (2007): 2021–2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Yan J., Wang L., Wang Z., et al., “Engineered Adenovirus Fiber Shaft Fusion Homotrimer of Soluble TRAIL With Enhanced Stability and Antitumor Activity,” Cell Death & Disease 7 (2016): e2274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Pan L. Q., Xie Z. M., Tang X. J., et al., “Engineering and Refolding of a Novel Trimeric Fusion Protein TRAIL‐Collagen XVIII NC1,” Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 97 (2013): 7253–7264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Liu H., Su D., Zhang J., et al., “Improvement of Pharmacokinetic Profile of TRAIL via Trimer‐Tag Enhances Its Antitumor Activity In Vivo,” Scientific Reports 7 (2017): 8953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wu X., Li P., Qian C., Li O., and Zhou Y., “Trimeric Coiled‐Coil Domain of Human Pulmonary Surfactant Protein D Enhances Zinc‐Binding Ability and Biologic Activity of Soluble TRAIL,” Molecular Immunology 46 (2009): 2381–2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Guo Y., Roohullah A., Xue J., et al., “Abstract 6180: First‐In‐Human (FIH) Phase I Studies of SCB‐313, a Novel TNF‐Related Apoptosis‐Inducing Ligand TRAIL‐Trimer™ Fusion Protein, for Treatment of Patients (Pts) With Malignant Ascites (MA),” Cancer Research 82 (2022): 6180. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ashkenazi A., “Targeting Death and Decoy Receptors of the Tumour‐Necrosis Factor Superfamily,” Nature Reviews. Cancer 2 (2002): 420–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wiley S. R., Schooley K., Smolak P. J., et al., “Identification and Characterization of a New Member of the TNF Family That Induces Apoptosis,” Immunity 3 (1995): 673–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Muhlenbeck F., Schneider P., Bodmer J. L., et al., “The Tumor Necrosis Factor‐Related Apoptosis‐Inducing Ligand Receptors TRAIL‐R1 and TRAIL‐R2 Have Distinct Cross‐Linking Requirements for Initiation of Apoptosis and Are Non‐redundant in JNK Activation,” Journal of Biological Chemistry 275 (2000): 32208–32213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Han J. H., Moon A. R., Chang J. H., et al., “Potentiation of TRAIL Killing Activity by Multimerization Through Isoleucine Zipper Hexamerization Motif,” BMB Reports 49 (2016): 282–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Richardson P. G., Polepally A. R., Motwani M., et al., “A Phase 1b, Open‐Label Study of Eftozanermin Alfa in Combination With Bortezomib and Dexamethasone in Patients With Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma,” Blood 136 (2020): 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Shin G., Lee J. E., Lee S.‐Y., Lee D.‐H., and Lim S. I., “Spatially Organized Nanoassembly of Single‐Chain TRAIL That Induces Optimal Death Receptor Clustering and Cancer‐Specific Apoptosis,” Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 95 (2024): 105638. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Seifert O., Plappert A., Fellermeier S., Siegemund M., Pfizenmaier K., and Kontermann R. E., “Tetravalent Antibody‐scTRAIL Fusion Proteins With Improved Properties,” Molecular Cancer Therapeutics 13 (2014): 101–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Phillips D. C., Buchanan F. G., Cheng D., et al., “Hexavalent TRAIL Fusion Protein Eftozanermin Alfa Optimally Clusters Apoptosis‐Inducing TRAIL Receptors to Induce on‐Target Antitumor Activity in Solid Tumors,” Cancer Research 81 (2021): 3402–3414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Yang H., Li H., Yang F., et al., “Molecular Superglue‐Mediated Higher‐Order Assembly of TRAIL Variants With Superior Apoptosis Induction and Antitumor Activity,” Biomaterials 295 (2023): 121994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Yoo J. D., Bae S. M., Seo J., et al., “Designed Ferritin Nanocages Displaying Trimeric TRAIL and Tumor‐Targeting Peptides Confer Superior Anti‐Tumor Efficacy,” Scientific Reports 10 (2020): 19997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. She T., Yang F., Chen S., et al., “Snoopligase‐Catalyzed Molecular Glue Enables Efficient Generation of Hyperoligomerized TRAIL Variant With Enhanced Antitumor Effect,” Journal of Controlled Release 361 (2023): 856–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Wang Y., Lei Q., Shen C., and Wang N., “NCTR(25) Fusion Facilitates the Formation of TRAIL Polymers That Selectively Activate TRAIL Receptors With Higher Potency and Efficacy Than TRAIL,” Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology 88 (2021): 289–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Huang K., Duan N., Zhang C., Mo R., and Hua Z., “Improved Antitumor Activity of TRAIL Fusion Protein via Formation of Self‐Assembling Nanoparticle,” Scientific Reports 7 (2017): 41904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Prigozhina T. B., Szafer F., Aronin A., et al., “Fn14.TRAIL Fusion Protein Is Oligomerized by TWEAK Into a Superefficient TRAIL Analog,” Cancer Letters 400 (2017): 99–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. LoRusso P., Ratain M. J., Doi T., et al., “Eftozanermin Alfa (ABBV‐621) Monotherapy in Patients With Previously Treated Solid Tumors: Findings of a Phase 1, First‐In‐Human Study,” Investigational New Drugs 40 (2022): 762–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Siegemund M., Schneider F., Hutt M., et al., “IgG‐Single‐Chain TRAIL Fusion Proteins for Tumour Therapy,” Scientific Reports 8 (2018): 7808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Zhang Y., Zhao G., Chen Y. F., et al., “Engineering Nano‐Clustered Multivalent Agonists to Cross‐Link TNF Receptors for Cancer Therapy,” Aggregate 4 (2023): e393. [Google Scholar]

- 79. Wang Y., Lei Q., Yan Z., Shen C., and Wang N., “TGF3L Fusion Enhances the Antitumor Activity of TRAIL by Promoting Assembly Into Polymers,” Biochemical Pharmacology 155 (2018): 510–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Gieffers C., Kluge M., Merz C., et al., “APG350 Induces Superior Clustering of TRAIL Receptors and Shows Therapeutic Antitumor Efficacy Independent of Cross‐Linking via Fcgamma Receptors,” Molecular Cancer Therapeutics 12 (2013): 2735–2747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Deng D. and Shah K., “TRAIL of Hope Meeting Resistance in Cancer, Trends,” Cancer 6 (2020): 989–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Jo M., Kim T. H., Seol D. W., et al., “Apoptosis Induced in Normal Human Hepatocytes by Tumor Necrosis Factor‐Related Apoptosis‐Inducing Ligand,” Nature Medicine 6 (2000): 564–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Hutt M., Fellermeier‐Kopf S., Seifert O., Schmitt L. C., Pfizenmaier K., and Kontermann R. E., “Targeting scFv‐Fc‐scTRAIL Fusion Proteins to Tumor Cells,” Oncotarget 9 (2018): 11322–11335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Zhu Y., Bassoff N., Reinshagen C., et al., “Bi‐Specific Molecule Against EGFR and Death Receptors Simultaneously Targets Proliferation and Death Pathways in Tumors,” Scientific Reports 7 (2017): 2602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Siegemund M., Seifert O., Zarani M., et al., “An Optimized Antibody‐Single‐Chain TRAIL Fusion Protein for Cancer Therapy,” MAbs 8 (2016): 879–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Wang Z., Chi L., and Shen Y., “Design, Expression, Purification and Characterization of the Recombinant Immunotoxin 4D5 scFv‐TRAIL,” International Journal of Peptide Research and Therapeutics 26 (2019): 889–897. [Google Scholar]

- 87. Katayama Y., Uchino J., Chihara Y., et al., “Tumor Neovascularization and Developments in Therapeutics,” Cancers (Basel) 11 (2019): 316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Goydel R. S. and Rader C., “Antibody‐Based Cancer Therapy,” Oncogene 40 (2021): 3655–3664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. de Bruyn M., Rybczynska A. A., Wei Y., et al., “Melanoma‐Associated Chondroitin Sulfate Proteoglycan (MCSP)‐Targeted Delivery of Soluble TRAIL Potently Inhibits Melanoma Outgrowth In Vitro and In Vivo,” Molecular Cancer 9 (2010): 301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Winterberg D., Lenk L., Osswald M., et al., “Engineering of CD19 Antibodies: A CD19‐TRAIL Fusion Construct Specifically Induces Apoptosis in B‐Cell Precursor Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (BCP‐ALL) Cells In Vivo,” Journal of Clinical Medicine 10 (2021): 2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. El‐Mesery M., Trebing J., Schafer V., Weisenberger D., Siegmund D., and Wajant H., “CD40‐Directed scFv‐TRAIL Fusion Proteins Induce CD40‐Restricted Tumor Cell Death and Activate Dendritic Cells,” Cell Death & Disease 4 (2013): e916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. ten Cate B., Bremer E., de Bruyn M., et al., “A Novel AML‐Selective TRAIL Fusion Protein That Is Superior to Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin in Terms of In Vitro Selectivity, Activity and Stability,” Leukemia 23 (2009): 1389–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Bremer E., Samplonius D. F., Peipp M., et al., “Target Cell‐Restricted Apoptosis Induction of Acute Leukemic T Cells by a Recombinant Tumor Necrosis Factor‐Related Apoptosis‐Inducing Ligand Fusion Protein With Specificity for Human CD7,” Cancer Research 65 (2005): 3380–3388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. De Luca R., Kachel P., Kropivsek K., Snijder B., Manz M. G., and Neri D., “A Novel Dual‐Cytokine‐Antibody Fusion Protein for the Treatment of CD38‐Positive Malignancies,” Protein Engineering, Design & Selection 31 (2018): 173–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Wiersma V. R., He Y., Samplonius D. F., et al., “A CD47‐Blocking TRAIL Fusion Protein With Dual Pro‐Phagocytic and Pro‐Apoptotic Anticancer Activity,” British Journal of Haematology 164 (2014): 304–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Hendriks D., He Y., Koopmans I., et al., “Programmed Death Ligand 1 (PD‐L1)‐Targeted TRAIL Combines PD‐L1‐Mediated Checkpoint Inhibition With TRAIL‐Mediated Apoptosis Induction,” Oncoimmunology 5 (2016): e1202390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Yan C., Li S., Li Z., et al., “Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells as Vehicles of CD20‐Specific TRAIL Fusion Protein Delivery: A Double‐Target Therapy Against Non‐Hodgkin's Lymphoma,” Molecular Pharmaceutics 10 (2013): 142–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Wang L. H., Ni C. W., Lin Y. Z., et al., “Targeted Induction of Apoptosis in Glioblastoma Multiforme Cells by an MRP3‐Specific TRAIL Fusion Protein In Vitro,” Tumour Biology 35 (2014): 1157–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Trebing J., El‐Mesery M., Schafer V., et al., “CD70‐Restricted Specific Activation of TRAILR1 or TRAILR2 Using scFv‐Targeted TRAIL Mutants,” Cell Death & Disease 5 (2014): e1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Weisser N. E. and Hall J. C., “Applications of Single‐Chain Variable Fragment Antibodies in Therapeutics and Diagnostics,” Biotechnology Advances 27 (2009): 502–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Hartung F., Kruwel T., Shi X., et al., “A Novel Anti‐Kv10.1 Nanobody Fused to Single‐Chain TRAIL Enhances Apoptosis Induction in Cancer Cells,” Frontiers in Pharmacology 11 (2020): 686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Checco J. W., Kreitler D. F., Thomas N. C., et al., “Targeting Diverse Protein‐Protein Interaction Interfaces With Alpha/Beta‐Peptides Derived From the Z‐Domain Scaffold,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112 (2015): 4552–4557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Xia X., Yang X., Huang W., Xia X., and Yan D., “Self‐Assembled Nanomicelles of Affibody‐Drug Conjugate With Excellent Therapeutic Property to Cure Ovary and Breast Cancers,” Nano‐Micro Letters 14 (2021): 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Tao Z., Liu Y., Yang H., et al., “Customizing a Tridomain TRAIL Variant to Achieve Active Tumor Homing and Endogenous Albumin‐Controlled Release of the Molecular Machine In Vivo,” Biomacromolecules 21 (2020): 4017–4029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Yagolovich A. V., Artykov A. A., Isakova A. A., et al., “Optimized Heterologous Expression and Efficient Purification of a New TRAIL‐Based Antitumor Fusion Protein SRH‐DR5‐B With Dual VEGFR2 and DR5 Receptor Specificity,” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23 (2022): 5860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Wang X., Qiao X., Shang Y., et al., “RGD and NGR Modified TRAIL Protein Exhibited Potent Anti‐Metastasis Effects on TRAIL‐Insensitive Cancer Cells In Vitro and In Vivo,” Amino Acids 49 (2017): 931–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Madhumathi J., Sridevi S., and Verma R. S., “Novel TNF‐Related Apoptotic‐Inducing Ligand‐Based Immunotoxin for Therapeutic Targeting of CD25 Positive Leukemia, Target,” Oncologia 11 (2016): 535–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Su Y., Tatzel K., Wang X., et al., “Mesothelin's Minimal MUC16 Binding Moiety Converts TR3 Into a Potent Cancer Therapeutic via Hierarchical Binding Events at the Plasma Membrane,” Oncotarget 7 (2016): 31534–31549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Uckun F. M., Myers D. E., Qazi S., et al., “Recombinant Human CD19L‐sTRAIL Effectively Targets B Cell Precursor Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia,” Journal of Clinical Investigation 125 (2015): 1006–1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]