Abstract

ABSTRACT

Introduction

Ethnic disparities in the prevalence and pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes are well documented, but prospective data on insulin dynamics vis-à-vis pre-diabetes/early dysglycemia risk in diverse populations are scant.

Research design and methods

We analyzed insulin secretion, sensitivity, and clearance among participants in the Pathobiology of Prediabetes in a Biracial Cohort (POP-ABC) study. The POP-ABC study followed initially normoglycemic offspring of parents with type 2 diabetes for 5.5 years, the primary outcome being incident dysglycemia. Assessments included anthropometry, oral glucose tolerance test, insulin sensitivity (hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp, HEC), insulin secretion (intravenous glucose tolerance test, IVGT), and disposition index (DI). Insulin clearance was derived as the molar ratio of plasma C peptide to insulin and by calculating the metabolic clearance rate during HEC.

Results

POP-ABC participants who completed IVGT and HEC at baseline (145 African American, 123 European American; 72% women; mean age 44.6±10.1 years) were included in the present analysis. The baseline fasting plasma glucose was 91.9±6.91 mg/dL (5.11±0.38 mmol/L) and 2-hour plasma glucose was 123±25.1 mg/dL (6.83±1.83 mmol/L). African American offspring of parents with type 2 diabetes had higher insulin secretion and DI, and lower insulin sensitivity and clearance, than their European American counterparts. During 5.5 years of follow-up, 91 of 268 participants developed incident dysglycemia and 177 maintained normoglycemia. In Cox proportional hazards models, insulin secretion (HR 0.997 (95% CI 0.996 to 0.999), p=0.005), insulin sensitivity (HR 0.948 (95% CI 0.913 to 0.984), p=0.005), DI (HR 0.945 (95% CI 0.909 to 0.983), p=0.005) and basal insulin clearance (HR 1.030 (95% CI 1.005 to 1.056), p=0.018) significantly predicted incident dysglycemia.

Conclusions

Insulin sensitivity, secretion, and clearance differ significantly in normoglycemic African American versus European American offspring of parents with type 2 diabetes and are associated with the risk of incident dysglycemia.

Keywords: Longitudinal Study, Impaired Glucose Tolerance, Ethnic Groups, African Americans

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

The roles of genetic predisposition, insulin resistance, and impaired beta-cell function in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes are well known, as are ethnic differences in insulin resistance and insulin secretion.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

To elucidate the roles of genetic diabetes risk versus ethnicity in the pathogenesis of early glucose abnormalities, the present study enrolled healthy offspring of parents with type 2 diabetes. We demonstrate that ethnic (Black vs White) differences in insulin sensitivity, insulin secretion, and insulin clearance are discernible among normoglycemic adults with similar parental history of type 2 diabetes. Black offspring of parents with type 2 diabetes had lower insulin sensitivity, higher insulin secretion, and lower insulin clearance than White offspring of parents with type 2 diabetes. The disposition index (insulin secretion corrected for insulin sensitivity) predicted progression to dysglycemia during 5.5-year follow-up, regardless of race/ethnicity.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Ethnic differences in insulin sensitivity, insulin secretion, and insulin clearance persist, despite similar hereditary (parental) diabetes history, suggesting specific mechanisms that may be mediated by racial/ethnic factors. Knowledge of the underlying mechanisms for such differences would inform appropriate early interventions to prevent dysglycemia in high-risk groups.

Introduction

The prevalence of type 2 diabetes varies across demographic groups, with higher rates being reported in non-Hispanic Black or African Americans compared with non-Hispanic White or European Americans.1 2 Current understanding identifies obesity, insulin resistance, impaired insulin secretion, and increased hepatic glucose production as major metabolic abnormalities in the pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes.3,9 Pre-diabetes is an intermediate stage between normal glucose regulation and type 2 diabetes. Despite reports of ethnic disparities in diabetes prevalence and underlying mechanisms, the progression from normal glucose regulation to pre-diabetes is not fully understood. Cross-sectional studies have reported disparities in insulin action, insulin secretion, and hepatic insulin clearance in persons of African descent compared with Caucasians.10,16 In the multiethnic Diabetes Prevention Program, higher baseline insulin secretion predicted regression from pre-diabetes to normal glucose regulation during longitudinal follow-up.17 Similar prospective studies of diverse cohorts are needed to elucidate the roles of insulin secretion, action, and clearance in the natural history of early dysglycemia.

The Pathobiology of Prediabetes in a Biracial Cohort (POP-ABC) study enrolled initially normoglycemic African American and European American adults with parental history of type 2 diabetes and followed them for 5.5 years, for incident dysglycemia.18 The objectives of the present post hoc analysis were to compare insulin secretion, action, and clearance, and assess their association with incident dysglycemia in African American and European American participants.

Research design and methods

Participants

The POP-ABC study18 19 is a prospective study that enrolled healthy offspring of parents with type 2 diabetes. Parental history of type 2 diabetes was documented with a diabetes-focused questionnaire that obtained information on diagnosis history, number of affected biological parents, sex of parent(s), parental age at diagnosis, parental use of diabetes medications, history of diabetic complications, and contact information of the parents’ physicians. Participants underwent a screening oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) to document normal fasting plasma glucose (FPG) (<100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L)) and normal glucose tolerance (NGT) (2-hour plasma glucose (2hrPG) <140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L)) prior to enrollment.18 19 By design, 75% of the subjects were enrolled with normal FPG and NGT, and 25% had either normal FPG or NGT at baseline. Individuals with diabetes or taking antidiabetes medications or other drugs known to affect glucose metabolism or body weight were excluded. Current illness, participation in weight loss programs, and recent hospitalization were among the exclusion criteria.18 19 A written informed consent was obtained from all participants and the study was carried out at The University of Tennessee Health Science Center General Clinical Research Center (GCRC). Enrollees who completed baseline assessment of insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity, and had evaluable follow-up data, were included for the present analysis (online supplemental figure S1).

Assessments

Clinical

Participants arrived at the GCRC for initial procedures after fasting for approximately 8–12 hours overnight. The procedures included a physical examination and measurement of height, weight, and waist circumference. Standing height was measured in duplicate with the participants barefoot, using a standard stadiometer. Body weight was measured in duplicate on a calibrated balance beam scale, with participants wearing light outdoor clothing. Waist was defined as the midpoint between the top of the iliac crest and the lowest costal margin in the midaxillary line and the circumference was measured using a Gulick II tape measure (Country Technology, Gays Mills, Wisconsin, USA).

The body mass index (BMI) was calculated as the weight in kilograms divided by the height in meter squared. A 75 g OGTT was completed by each participant, as previously described.18 19

Insulin sensitivity

Insulin sensitivity was measured using hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp, as previously described.19 20 In brief, overnight fasted participants underwent the clamp studies at the GCRC. Indwelling intravenous cannulas were placed in antecubital veins in both arms and a primed, continuous infusion of regular human insulin (2 mU/kg/min; 12 pmol/kg/min) was administered over 180 min while blood glucose concentration was maintained at ~100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L) with a variable rate dextrose (20%) infusion.19 Arterialized blood samples for glucose and insulin assays were obtained every 10 min. Insulin-stimulated glucose disposal or glucose metabolized (M) was calculated during steady state (final 60 min) and corrected for the steady-state plasma insulin levels to obtain the insulin sensitivity index (Si-clamp).19 20 Additionally, we estimated insulin sensitivity by calculating the Matsuda index, using plasma glucose and insulin data obtained during OGTT.21

Insulin secretion

Basal insulin secretion was assessed using the fasting plasma insulin level and by homeostasis modeling. The homeostasis model assessment of beta-cell function (HOMA-B) was calculated with a computer program (HOMA2 calculator, https://homa-calculator.informer.com/2.2/) based on Matthews et al.22 Dynamic insulin secretion was assessed by calculating the insulinogenic index and the acute insulin response (AIR) following intravenous glucose bolus. The insulinogenic index was calculated using glucose and insulin values from the OGTT as follows: [plasma insulin (30 min)−fasting plasma insulin (µU/mL)]/[plasma glucose (30 min)−fasting plasma glucose (mg/mL)].23

Acute insulin response

Participants arrived at the GCRC after an overnight fast for intravenous glucose tolerance test (IVGT) for assessing AIR to glucose. An intravenous bolus of dextrose (25 g) was administered, with sampling of arterialized blood for glucose and insulin measurement at −30, 0, and 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, and 10 min relative to the dextrose bolus. The mean incremental plasma insulin concentration at 3, 4, 5 min after the dextrose bolus was computed as the AIR and expressed as a percentage of fasting values (AIR% increase).9 18 The disposition index was calculated as AIR×Si-clamp.9 24

Insulin clearance

Basal insulin clearance was calculated as the mean of the molar ratios of fasting C peptide to fasting insulin concentrations in plasma specimens obtained at −30 min and 0 min before administration of intravenous dextrose.25 Dynamic insulin clearance was calculated as the mean of the molar ratios of incremental plasma C peptide to insulin levels at 3, 4, 5, 7 and 10 min during IVGT. The molar ratios of C peptide and insulin at steady state reflect hepatic insulin extraction in healthy individuals with normal kidney dysfunction. The use of simple molar ratios of C peptide and insulin to compute hepatic insulin extraction or clearance during non-steady state is fraught with potential limitations.26 However, use of the molar ratios of incremental integrated values of plasma C peptide and insulin levels has been suggested as an acceptable approach for assessing hepatic insulin extraction or clearance.27

The metabolic clearance rate (MCR) of insulin during hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp was calculated by the method of DeFronzo et al20 using the formula:

Laboratory analyses

Plasma glucose levels were measured using the glucose oxidase method (Yellow Springs Instruments, Yellow Springs, Ohio). Plasma insulin and C peptide levels were measured immunochemically at our Endocrine Research Laboratory using commercial kits. The insulin assay had a sensitivity of 2 µIU/mL; the within-run and between-run coefficients of variation were 2% and 4.8%, respectively. The C peptide assay had a sensitivity of 0.2 ng/mL; the within-run and between-run coefficients of variation were 2.5% and 4.9%, respectively. Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels were measured in a contract laboratory.

Determination of dysglycemic outcomes

The primary outcome measure of the POP-ABC study was the development of incident pre-diabetes.18 19 Pre-diabetes was diagnosed as impaired fasting glucose (IFG), evidenced by FPG of 100–125 mg/dL (5.5–6.9 mmol/L) or impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) (2hrPG of 140–199 mg/dL (7.8–11.0 mmol/L)).18 19 Any occurrence of diabetes, as indicated by an FPG value of 126 mg/dL (7.0 mmol/L) or higher or 2hrPG of 200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L) or higher, or use of a diabetes medication, was an endpoint. For individuals enrolled with normal FPG and NGT, the occurrence of IFG and/or IGT was an endpoint. For those enrolled with normal FPG and isolated IGT, progression to IFG was an endpoint. For persons enrolled with NGT and isolated IFG, progression to IGT was an endpoint. All endpoints were independently adjudicated by the Institutional Data and Safety Officer (Murray Heimberg, MD, PhD).

Statistical analysis

Data are reported as means±SD. Differences between comparison groups were analyzed using unpaired t-test, χ2 test and multivariate analysis of variance, as appropriate. The area under the curve (AUC) of plasma insulin and AUC of plasma glucose excursions during IVGT were calculated using the trapezoidal rule. The association between metabolic variables and incident dysglycemia was assessed using Cox proportional hazards regression models, with adjustments for baseline variables. To enable evaluation of the relative importance of the variables to the development of dysglycemia, the raw data were standardized by transformation to z-scores before running the Cox models. Thus, the HRs represent the effect of a 1 SD change in the measured variable on the incidence of dysglycemia. Multicollinearity was assessed in the models.28 The association of disposition index with incident dysglycemia was assessed using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and logrank test. Significance level was set as p<0.05 (two tailed). The analyses were performed using SAS statistical software V.9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

Demographic and metabolic variables at baseline

A total of 268 adults (145 African American, 123 European American; 193 women, 75 men) who completed baseline assessment of insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity in the POP-ABC study were included in the present analysis (online supplemental figure S1). The participants’ baseline characteristics are shown in table 1. The mean age of participants was 44.6±10.1 years and mean BMI was 30.3±7.37 kg/m2. Compared with European American participants, African American participants were younger, had higher BMI and HbA1c, similar waist circumference and 2hrPG, and lower FPG values (table 1). Approximately 85% of participants had one parent with type 2 diabetes and ~15% had both parents affected. As reported in the primary results of the POP-ABC study,29 African American participants were more likely to report maternal diabetes history, whereas European American participants were more likely to report paternal diabetes history.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of study subjects.

| Characteristics | All participants (n=268) |

African American (n=145) |

European American (n=123) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 44.6±10.1 | 42.9±9.80 | 46.7±10.1 | 0.0021 |

| Sex (women/men) | 268 (193/75) (72%/28%) | 145 (110/35) (75.9%/24.1%) | 123 (83/40) (67.5%/32.5%) | 0.13 |

| One parent with type 2 diabetes | 229 (85.4%) | 121 (83.4%) | 108 (87.8%) | 0.89 |

| Maternal diabetes | 125 (46.6%) | 80 (55.2%) | 45 (36.6%) | 0.0024 |

| Paternal diabetes | 104 (38.8%) | 41 (28.3%) | 63 (51.2%) | 0.0001 |

| Both parents with type 2 diabetes | 39 (14.6%) | 24 (16.6%) | 15 (12.2%) | 0.31 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 94.6±15.9 | 95.4±16.2 | 93.7±15.5 | 0.37 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.3±7.37 | 31.6±7.64 | 28.9±6.79 | 0.0032 |

| FPG (mg/dL) | 91.9±6.91 | 91.0±7.26 | 93.1±6.31 | 0.012 |

| 2hrPG (mg/dL) | 123±25.1 | 122±26.9 | 123±23.1 | 0.79 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.58±0.44 | 5.69±0.49 | 5.44±0.34 | <0.0001 |

BMI, body mass index; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; 2hrPG, 2-hour postload plasma glucose during oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT).

Basal and dynamic insulin secretion and clearance

At enrollment, the mean fasting plasma insulin level was similar in African American versus European American offspring of parents with type 2 diabetes, as was HOMA-B (table 2). African American offspring of parents with type 2 diabetes had lower basal insulin clearance compared with European American offspring of parents with type 2 diabetes, before and after adjustment for multiple baseline variables, including sex, age, maternal/paternal diabetes history, BMI, waist circumference, FPG, and HbA1c (table 2).

Table 2. Baseline insulin sensitivity, secretion, and clearance under basal and dynamic conditions by race/ethnicity.

| All participants (n=268) | African American (n=145) | European American (n=123) |

Unadjusted P value |

Adjusted P value* |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basal state | |||||

| Fasting insulin (µU/mL) | 8.19±7.31 | 7.79±5.72 | 8.69±8.87 | 0.35 | 0.16 |

| HOMA-B (%) | 91.8±66.9 | 92.5±57.4 | 91.0±71.8 | 0.85 | 0.27 |

| Basal insulin clearance | 19.2±10.6 | 17.3±9.36 | 21.1±11.6 | 0.008 | 0.026 |

| Dynamic state | |||||

| Si-clamp (mmol/kg fat-free mass.min/pM.) | 0.134±0.067 | 0.125±0.069 | 0.143±0.063 | 0.049 | 0.02 |

| M (μmol/kg fat-free mass) | 86.3±30.1 | 85.1±32.4 | 87.6±27.6 | 0.541 | 0.11 |

| Matsuda index | 6.07±3.86 | 6.20±4.16 | 5.91±3.47 | 0.59 | 0.44 |

| Insulinogenic index | 1.28±1.11 | 1.56±1.31 | 0.920±0.633 | <0.0001 | 0.005 |

| AUC-IVGT glucose (mg/dL/min) |

5306±444 | 5234±477 | 5392±386 | 0.0017 | 0.24 |

| AUC-IVGT insulin (µU/mL/min) |

1062±1004 | 1195±980 | 900±1013 | 0.013 | 0.002 |

| AIR (% increase) | 1798±1423 | 1805±1553 | 1269±1252 | 0.0024 | 0.0013 |

| Disposition index | 9.76±7.55 | 11.0±9.09 | 8.50±5.37 | 0.027 | 0.20 |

| Dynamic insulin clearance | 6.81±3.52 | 5.84±3.28 | 7.82±3.48 | <0.0001 | 0.0005 |

| MCR insulin (mL/m2 BSA/min) | 4.89±2.15 | 4.50±2.17 | 5.29±2.07 | 0.02 | 0.13 |

Adjusted for sex, age, maternal/paternal diabetes history, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, fasting plasma glucose (FPG), and HbA1c at baseline.

AIR, acute insulin response to intravenous glucose; AUC-IVGT, area under the curve during intravenous glucose tolerance test; BSA, body surface area; HOMA-B, homeostasis model assessment of beta-cell function; M, glucose metabolized during euglycemic clamp; MCR, metabolic clearance rate of insulin during euglycemic clamp; Si-clamp, insulin sensitivity measured with hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp.

The mean insulinogenic index was significantly higher in African American versus European American participants, adjusted for baseline variables (table 2). Compared with European American participants, African American participants had higher AUC insulin during IVGT, despite similar plasma glucose excursions (table 2 and online supplemental figure S2). The peak insulin response during IVGT as a percentage of baseline fasting insulin level (AIR%) was higher in African American offspring of parents with type 2 diabetes compared with European American offspring of parents with type 2 diabetes (table 2). Compared with European American participants, African American participants had significantly lower dynamic insulin clearance based on molar ratios of plasma insulin and C peptide during IVGT (table 2). The MCR for insulin during hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp also was lower in African American offspring of parents (table 2).

Insulin sensitivity

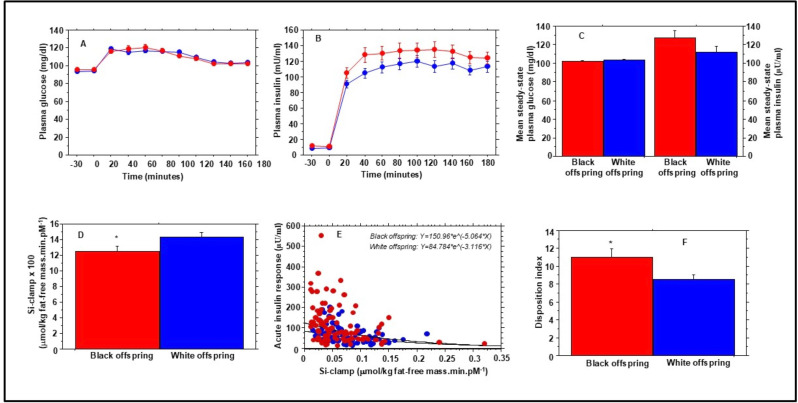

There was no significant difference between African American versus European American participants in the Matsuda index of insulin sensitivity derived from OGTT plasma insulin and glucose values (table 2). Figure 1 shows plasma glucose (figure 1A) and insulin (figure 1B) excursions during hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp in African American and European American participants. The mean steady-state (final 60 min of the clamp) plasma glucose (102±6.00 mg/dL vs 103±4.53 mg/dL, p=0.20) was similar in African American versus European American participants (figure 1C and table 2). The mean steady-state plasma insulin during the hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp was numerically higher in African American versus European American participants (figure 1C), but the difference did not reach statistical significance (127±48.2 µU/mL vs 113±39.1 µU/mL, p=0.11). Mean values for M (glucose metabolized during euglycemic clamp) were not significantly different in African American versus European American participants (table 2). However, the mean whole-body insulin sensitivity (Si-clamp) was lower in African American versus European American participants (figure 1D). The ethnic difference in Si-clamp remained significant (p=0.038) after adjusting for sex, baseline variables age, BMI, waist circumference, FPG, 2hrPG, HbA1c, and parental diabetes history.

Figure 1. Plasma glucose (A) and insulin (B) levels during hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp in African American (red symbols) and European American (blue symbols) offspring of parents with type 2 diabetes at enrollment in the Pathobiology of Prediabetes in a Biracial Cohort (POP-ABC) study. Glucose infusion rate during steady-state plasma glucose (final 60 min of the clamp procedure) was corrected for ambient steady-state plasma insulin levels (C) to derive insulin sensitivity (Si-clamp) (D). (E) The regression of acute insulin response versus Si-clamp in African American (red symbols) and European American (blue symbols) offspring of parents with type 2 diabetes. The disposition index was calculated as the product of acute insulin response and Si-clamp (F). *P=0.017.

Disposition index

Figure 1E shows the regression of AIR versus Si-clamp in African American and European American participants. The regression equations were Y=126.223*eˆ(−6.755*X) in African American offspring of parents with type 2 diabetes and Y=82.776*eˆ(−5.654*X) in European American offspring of parents with type 2 diabetes (p<0.0001). The mean disposition index was higher in African American versus European American offspring of parents with type 2 diabetes (11.0±9.09 vs 8.50±5.37; 0.027) (figure 1F, table 2). The ethnic difference in disposition index remained significant (p=0.03) after adjustment for age, sex, BMI, FPG, and HbA1c at baseline, but not after additional adjustment for baseline waist circumference and maternal/paternal diabetes history (table 2).

As already noted, among study participants who had one parent with type 2 diabetes, maternal diabetes predominated among African American participants, whereas paternal diabetes predominated among European American participants. However, we found no significant interaction between maternal/paternal diabetes status and insulin sensitivity, secretion, or clearance. We also did not observe sex differences in the measures of insulin sensitivity, secretion, or clearance among our study population.

Progression to dysglycemia

Online supplemental table S1 shows the baseline characteristics of participants who developed dysglycemia (progressors) compared with non-progressors. As was observed in the overall POP-ABC study population,29 there were significant baseline differences in age, BMI, waist circumference and blood glucose between progressors and non-progressors (online supplemental table S1) among the 268 participants in the present analysis. During 5.5 years (mean 2.62 years) of follow-up in the POP-ABC study, 91 of 268 participants developed incident dysglycemia (83 pre-diabetes (43 African American, 40 European American) and 8 type 2 diabetes (4 African American, 4 European American)). The remainder 177 participants (98 African American, 79 European American) maintained normoglycemia (non-progressors). The cumulative incidence of pre-diabetes/diabetes was 34% (32.4% in African American participants and 35.8% in European American participants). Consistent with our previous report of the main results from the POP-ABC study, the incidence of dysglycemia did not differ significantly by race/ethnicity, after adjustment for sex, age, BMI, waist circumference and blood glucose at baseline (logrank p=0.30).29

Table 3 shows baseline measures of insulin secretion, sensitivity, and clearance in progressors and non-progressors. All measures of insulin clearance were similar in progressors versus non-progressors; however, there were differences in measures of insulin action and secretion.

Table 3. Baseline insulin sensitivity, secretion, and clearance by dysglycemia progression status.

| Total (n=268) |

Non-progressors (n=177) |

Progressors (n=91) |

Unadjusted P value |

Adjusted P value* |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basal state | |||||

| Fasting insulin (µU/mL) | 8.19±7.31 | 7.40±6.65 | 9.73±8.27 | 0.02 | 0.16 |

| HOMA-B (%) | 91.8±66.9 | 87.7±67.6 | 100±65.0 | 0.12 | 0.38 |

| Basal insulin clearance | 19.2±10.6 | 19.7±10.4 | 18.3±11.0 | 0.32 | 0.97 |

| Dynamic state | |||||

| Si-clamp (mmol/kg fat-free mass.min/pM.) | 0.134±0.067 | 0.146±0.064 | 0.116±0.067 | 0.002 | 0.40 |

| M (μmol/min/kg fat-free mass) | 86.3±30.1 | 91.6±28.6 | 78.7±30.6 | 0.002 | 0.20 |

| Matsuda index | 6.07±3.86 | 6.38±3.62 | 5.49±4.25 | 0.09 | 0.58 |

| Insulinogenic index | 1.28±1.11 | 1.30±1.14 | 1.25±1.10 | 0.71 | 0.86 |

| AUC-IVGT glucose (mg/dL/min) | 5306±444 | 5290±437 | 5338±458 | 0.38 | 0.76 |

| AUC-IVGT insulin (µU/mL/min) | 1062±1004 | 1083±1123 | 1020±719 | 0.56 | 0.50 |

| AIR (% increase) | 1798±1423 | 2070±1567 | 1401±1074 | 0.0007 | 0.34 |

| Disposition index | 9.76±7.55 | 11.1±8.55 | 7.89±5.41 | 0.005 | 0.038 |

| Dynamic insulin clearance | 6.81±3.52 | 6.90±3.62 | 6.67±3.37 | 0.64 | 0.36 |

| MCR insulin (mL/m2 BSA/min) | 4.77±2.26 | 4.75±2.11 | 4.80±2.49 | 0.87 | 0.32 |

Adjusted for sex, age, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, fasting plasma glucose (FPG), and HbA1c at baseline.

AIR, acute insulin response to intravenous glucose; AUC-IVGT, area under the curve during intravenous glucose tolerance test; BSA, body surface area; HOMA-B, homeostasis model assessment of beta-cell function; M, glucose metabolized during euglycemic clamp; MCR, metabolic clearance rate of insulin during euglycemic clamp; Si-clamp, insulin sensitivity measured with hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp.

Insulin secretion and incident dysglycemia

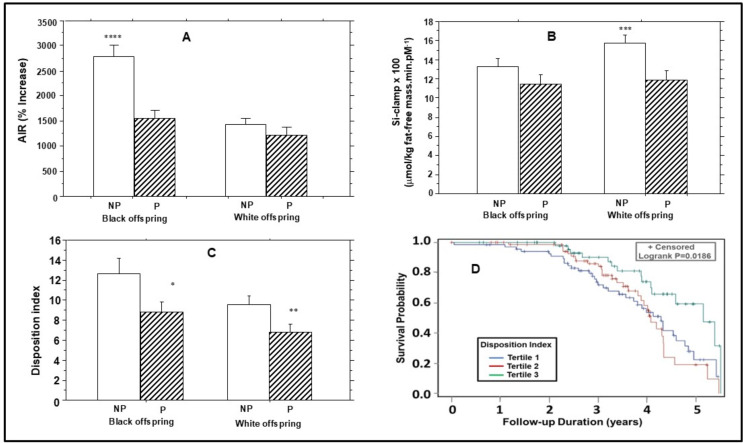

In adjusted comparisons, participants with incident dysglycemia had higher baseline fasting insulin levels but lower AIR (%) (peak insulin secretion during IVGT), compared with non-progressors (1401±1074% vs 2070±1567%, p=0.0007) (table 3). The progressors versus non-progressors difference in AIR (%) was more marked in African American participants (1544±1118% vs 2784±1784%, p<0.0001) compared with European American participants (1222±1002 vs 1432±985, p=0.29) (figure 2), and lost statistical significance after adjustment for baseline age, sex, BMI, waist circumference, FPG, and HbA1c (table 3).

Figure 2. Baseline insulin secretion (A), insulin sensitivity (B) and disposition index (C) in progressors (P) and non-progressors (NP) to dysglycemia among offspring of parents with type 2 diabetes. (D) Kaplan-Meier plot of dysglycemia survival probability stratified by baseline tertiles of disposition index. Higher baseline disposition index was associated with increased dysglycemia survival probability (logrank p=0.015). *P=0.042; **p=0.015; ***p=0.0022; ****p<0.0001. AIR, acute insulin response.

Insulin sensitivity and incident dysglycemia

The Matsuda index of insulin sensitivity was similar in progressors to dysglycemia versus non-progressors (table 2). However, baseline Si-clamp and M values were lower in progressors versus non-progressors in unadjusted but not adjusted comparisons (table 3). The finding of difference in Si-clamp between progressors and non-progressors was less evident in African American participants (0.114±0.074 vs 0.133±0.065, p=0.17) compared with European American participants (0.119±0.059 vs 0.158±0.061, p=0.002) (figure 2).

Disposition index and incident dysglycemia

The baseline disposition index (insulin secretion adjusted for insulin sensitivity) was lower in progressors to dysglycemia (7.89±5.41) versus non-progressors (11.1±8.55, p=0.005) (table 3). The lower disposition index in progressors versus non-progressors was consistent in African American (8.87±6.07 vs 12.7±9.06, p=0.042) and European American (6.82±4.41 vs 9.63±5.69, p=0.015) participants (figure 2C), and persisted after adjustment for sex, age, BMI, waist circumference, FPG, and HbA1c at baseline (table 3). In relative terms, baseline disposition index was significantly lower by 29.2% in European American progressors versus non-progressors and by 30.1% in African American progressors versus non-progressors.

In Cox proportional hazards models, baseline AIR (%) predicted incident dysglycemia with an HR (per 1 SD change) of 0.695 (95% CI 0.540 to 0.896), p=0.005, adjusted for age, sex and race/ethnicity. Specifically, there was no interaction by race/ethnicity in the relationship between AIR (%) and incident dysglycemia (p=0.34). In the same models, insulin sensitivity had an HR (per 1 SD change) of 0.700 (95% CI 0.546 to 0.896), p=0.005 (interaction by race, p=0.34); and baseline disposition index had an HR (per 1 SD change) of 0.692 (95% CI 0.516 to 0.928), p=0.005 (interaction by race, p=0.48) (online supplemental table S2). After additional adjustment for BMI, the HR (per 1 SD change) for insulin sensitivity (0.858 (95% CI 0.651 to 1.131), p=0.28) and insulin secretion (0.783 (95% CI 0.609 to 1.007), p=0.056) became attenuated, indicating that the effects were mediated, at least in part, by adiposity. However, the association of baseline disposition index with incident dysglycemia remained significant after additional adjustment for BMI (HR (per 1 SD change) 0.700 (95% CI 0.517 to 0.947), p=0.02) (interaction by race, p=0.80). Figure 2D shows Kaplan-Meier plot of dysglycemia survival probability stratified by tertiles of baseline disposition index. Higher baseline disposition index was associated with decreased probability of developing dysglycemia, adjusted for age, sex, BMI and race/ethnicity (logrank p=0.0186).

Insulin clearance and incident dysglycemia

Neither the clearance of endogenous insulin (in the fasting state and during IVGT) nor that of exogenous insulin infused during euglycemic clamp (MCR) differed significantly in progressors versus non-progressors (table 3). However, in Cox proportional hazards models, adjusted for age, sex, BMI and race/ethnicity, the HR (per 1 SD change) for incident dysglycemia was 1.372 (95% CI 1.056 to 1.781, p=0.018) for basal insulin clearance and 1.339 (95% CI 1.050 to 1.707, p=0.019) for dynamic insulin clearance (online supplemental table S2). After additional adjustments for FPG, fasting plasma insulin, insulin sensitivity, and insulin secretion, the HR (per 1 SD change) for incident dysglycemia was 1.741 (95% CI 1.231 to 2.464, p=0.0017) for basal insulin clearance and 1.850 (95% CI 1.204 to 2.844, p=0.005) for dynamic insulin clearance (online supplemental table S2). The MCR for exogenous insulin infused during euglycemic clamp was not a significant predictor of dysglycemia in unadjusted (HR 0.861 (95% CI 0.687 to 1.079), p=0.19), minimally adjusted (HR 0.859 (95% CI 0.682 to 1.081), p=0.20), or fully adjusted (HR 0.950 (95% CI 0.747 to 1.209), p=0.68) models.

Multicollinearity diagnostics28 determined that the largest condition index (conditional number) was 17 for baseline AIR (%), 19 for Si-clamp and 17 for disposition index in the regression models predicting incident dysglycemia. A condition number between 10 and 30 indicates the presence of multicollinearity and a number larger than 30 indicates strong multicollinearity in the model. Thus, the condition numbers of 17–19 associated with our regression models indicate moderate multicollinearity among AIR (%), Si-clamp, and disposition index, as predictors of incident dysglycemia.

Discussion

The present study showed that, among normoglycemic adults with parental history of type 2 diabetes, African Americans had lower insulin sensitivity, higher insulin secretion, and lower insulin clearance compared with European Americans. Additionally, insulin sensitivity, insulin secretion, and insulin clearance predicted progression to pre-diabetes, regardless of ethnicity. Defects in insulin action and insulin secretion are demonstrable in people with type 2 diabetes.4,1230 In prospective studies, these defects precede the onset of dysglycemia.9 24 33 However, there are limited data on insulin action, secretion, and clearance in relation to incident pre-diabetes.

By enrolling normoglycemic African American and European American adults with parental type 2 diabetes, we had hoped to dampen differences due to genetic (hereditary) diabetes risk, thereby permitting the detection of differences explicable by race/ethnicity. Our findings of lower insulin sensitivity in African American versus European American participants extend previous reports10 11 34 35 by demonstrating ethnic disparities among individuals with similar parental diabetes history. Thus, insulin sensitivity appears to be a trait with a discernible link to race/ethnicity, after controlling for hereditary diabetes risk. Potential mediators of our findings include obesity, proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory markers in African Americans versus European Americans.29 36 37 Defects in insulin signaling, such as the inactivating AKT2 variant found in Finns, have not been reported in African Americans.38 However, differential expression of gene ontologies associated with insulin action has been reported in transcriptomic analysis of adipose tissue from African American and European American adults.39

We also observed greater glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in African American versus European American participants, consistent with previous reports.11,1440 Thus, greater insulin secretion coexists with lower insulin sensitivity as a trait that might also be explicable by race/ethnicity when comparing African American and European American offspring of parents with diabetes. To our knowledge, ethnic differences in the cellular and molecular mechanisms leading to glucose-stimulated insulin secretion have not been reported.41

Our data showed lower clearance of endogenous insulin in African American participants compared with European American participants. These findings extend previous reports13 14 16 17 by demonstrating such disparities among individuals with similar parental diabetes history. The liver normally extracts most (~70%) of the endogenous insulin secreted by the pancreatic beta cells into the portal circulation.42 43 Endogenous insulin that escapes hepatic first-pass extraction enters the systemic circulation for clearance by peripheral tissues.44,46 Thus, our findings indicate ethnic disparities in hepatic insulin extraction among healthy offspring of parents with type 2 diabetes.

Regarding mechanisms, it has been suggested that insulin resistance could impair insulin clearance, given the shared downstream mechanisms of insulin signal transduction and insulin degradation.45,47 It has also been proposed that hyperinsulinemia, from decreased clearance, could induce insulin resistance through downregulation of receptors, thereby increasing the risk of type 2 diabetes.48 Reduced insulin clearance has been implicated as a risk factor for type 2 and pre-diabetes,49 50 although prospective studies in diverse cohorts are scant. Semnani-Azad et al reported an inverse association between baseline insulin clearance and incident pre-diabetes during 9-year follow-up of initially normoglycemic individuals.50 In contrast, our present study showed a direct association between baseline insulin clearance and incident dysglycemia during 5.5 years of follow-up. Taken together, these findings suggest that lower clearance (leading to hyperinsulinemia) might be protective of incident dysglycemia initially but could eventually become maladaptive and increase the risk of progressive dysglycemia.4345,47

Our study has several strengths, including the prospective design, moderate sample size, diverse cohort, and lengthy follow-up. Other strengths include the rigorous assessments of insulin sensitivity and insulin dynamics. Additionally, the primary outcome of pre-diabetes/type 2 diabetes was adjudicated robustly. The limitations of our study include the exclusive enrollment of individuals with parental history of diabetes, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to people without parental history of diabetes. Furthermore, being a natural history study, lifestyle practices by study participants (such as diet and exercise) that could affect insulin sensitivity and blood glucose levels were ad libitum. Thus, individual differences in lifestyle practices could have affected some of the differences observed between comparison groups. Another limitation is that we assessed insulin secretion, sensitivity, and clearance only at baseline. Thus, any effects of temporal changes in those measures on incident dysglycemia could not be determined. Despite these limitations, our study extends previous reports by demonstrating ethnic disparities in insulin sensitivity, insulin secretion, and insulin clearance among normoglycemic African American and European American adults with parental history of type 2 diabetes.

In conclusion, differences in glucoregulatory measures persist between Black and White individuals, despite similar hereditary (parental) diabetes risk, which raises the possibility of factors uniquely mediated by race/ethnicity. Importantly, we show that baseline insulin secretion, insulin sensitivity, the disposition index, and insulin clearance were associated with the risk of progression from normoglycemia to dysglycemia, regardless of race/ethnicity.

Supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the research volunteers who participated in the POP-ABC study; The University of Tennessee Clinical Research Center staff for their assistance; and Murray Heimberg, MD, PhD (Institutional Data and Safety Officer), for adjudication of endpoints.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Funding: The POP-ABC study was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Diabetes Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01 DK067269).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: This study involves human participants and the POP-ABC study protocol was approved by The University of Tennessee Institutional Review Board (IRB approval number: 8399). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

Data availability free text: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National diabetes statistics report. 2024 https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics-report/index.html Available.

- 2.Brancati FL, Kao WHL, Folsom AR, et al. Incident Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in African American and White Adults. JAMA. 2000;283:2253. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.17.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dagogo-Jack S. Ethnic disparities in type 2 diabetes: pathophysiology and implications for prevention and management. J Natl Med Assoc. 2003;95:774–89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeFronzo RA. The Triumvirate: β-Cell, Muscle, Liver: A Collusion Responsible for NIDDM. Diabetes. 1988;37:667–87. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.6.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reaven GM, Hollenbeck CB, Chen YDI. Relationship between glucose tolerance, insulin secretion, and insulin action in non-obese individuals with varying degrees of glucose tolerance. Diabetologia. 1989;32:52–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00265404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeFronzo RA. From the Triumvirate to the Ominous Octet: A New Paradigm for the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes. 2009;58:773–95. doi: 10.2337/db09-9028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lillioja S, Mott DM, Spraul M, et al. Insulin resistance and insulin secretory dysfunction as precursors of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Prospective studies of Pima Indians. N Engl J Med . 1993;329:1988–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312303292703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knowler WC, Pettitt DJ, Saad MF, et al. Diabetes mellitus in the Pima Indians: incidence, risk factors and pathogenesis. Diabetes Metab Rev. 1990;6:1–27. doi: 10.1002/dmr.5610060101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weyer C, Bogardus C, Mott DM, et al. The natural history of insulin secretory dysfunction and insulin resistance in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:787–94. doi: 10.1172/JCI7231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osei K, Gaillard T, Schuster DP. Pathogenetic mechanisms of impaired glucose tolerance and type II diabetes in African Americans. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:396–404. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.3.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haffner SM, D’Agostino R, Saad MF, et al. Increased insulin resistance and insulin secretion in nondiabetic African-Americans and Hispanics compared with non-Hispanic whites. The Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study. Diabetes. 1996;45:742–8. doi: 10.2337/diab.45.6.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mbanya JC, Cruickshank JK, Forrester T, et al. Standardized comparison of glucose intolerance in west African-origin populations of rural and urban Cameroon, Jamaica, and Caribbean migrants to Britain. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:434–40. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osei K, Schuster DP, Owusu SK, et al. Race and ethnicity determine serum insulin and C-peptide concentrations and hepatic insulin extraction and insulin clearance: comparative studies of three populations of West African ancestry and white Americans. Metab Clin Exp. 1997;46:53–8. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(97)90167-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris MI, Cowie CC, Gu K, et al. Higher fasting insulin but lower fasting C-peptide levels in African Americans in the US population. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2002;18:149–55. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mbanya JC, Pani LN, Mbanya DN, et al. Reduced insulin secretion in offspring of African type 2 diabetic parents. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:1761–5. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.12.1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ladwa M, Bello O, Hakim O, et al. Insulin clearance as the major player in the hyperinsulinaemia of black African men without diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22:1808–17. doi: 10.1111/dom.14101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perreault L, Kahn SE, Christophi CA, et al. Regression from pre-diabetes to normal glucose regulation in the diabetes prevention program. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1583–8. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dagogo-Jack S, Edeoga C, Nyenwe E, et al. Pathobiology of Prediabetes in a Biracial Cohort (POP-ABC): design and methods. Ethn Dis. 2011;21:33–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dagogo-Jack S, Edeoga C, Ebenibo S, et al. Pathobiology of Prediabetes in a Biracial Cohort (POP-ABC) Research Group. Pathobiology of Prediabetes in a Biracial Cohort (POP-ABC) study: baseline characteristics of enrolled subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:120–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeFronzo RA, Tobin JD, Andres R. Glucose clamp technique: a method for quantifying insulin secretion and resistance. Am J Physiol. 1979;237:E214–23. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1979.237.3.E214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsuda M, DeFronzo RA. Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing: comparison with the euglycemic insulin clamp. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:1462–70. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.9.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, et al. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28:412–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kitabchi AE, Temprosa M, Knowler WC, et al. Role of insulin secretion and sensitivity in the evolution of type 2 diabetes in the diabetes prevention program: effects of lifestyle intervention and metformin. Diabetes. 2005;54:2404–14. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.8.2404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kahn SE, Prigeon RL, McCulloch DK, et al. Quantification of the relationship between insulin sensitivity and beta-cell function in human subjects. Evidence for a hyperbolic function. Diabetes. 1993;42:1663–72. doi: 10.2337/diab.42.11.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castillo MJ, Scheen AJ, Letiexhe MR, et al. How to measure insulin clearance. Diabetes Metab Rev. 1994;10:119–50. doi: 10.1002/dmr.5610100205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Polonsky KS, Rubenstein AH. C-peptide as a measure of the secretion and hepatic extraction of insulin. Pitfalls and limitations. Diabetes . 1984;33:486–94. doi: 10.2337/diab.33.5.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Radziuk J, Morishima T. In: Methods in Diabetes Research. Lanner J, Pohl SL, editors. New York, Wiley: 1986. Assessment of insulin kinetics in vivo; pp. 91–106. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Belsley DA, Kuh E, Welsch RE. Regression Diagnostics: Identifying Influential Data and Sources of Collinearity. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dagogo-Jack S, Edeoga C, Ebenibo S, et al. Lack of racial disparity in incident prediabetes and glycemic progression among black and white offspring of parents with type 2 diabetes: the pathobiology of prediabetes in a biracial cohort (POP-ABC) study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:E1078–87. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dagogo-Jack S, Askari H, Tykodi G. Glucoregulatory physiology in subjects with low-normal, high-normal, or impaired fasting glucose. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:2031–6. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferrannini E, Natali A, Bell P, et al. Insulin resistance and hypersecretion in obesity. EGIR J Clin Invest. 1997;100:1166–73. doi: 10.1172/JCI119628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Echouffo-Tcheugui JB, Perreault L, Ji L, et al. Diagnosis and Management of Prediabetes: A Review. JAMA. 2023;329:1206–16. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.4063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Owei I, Umekwe N, Provo C, et al. Insulin-sensitive and insulin-resistant obese and non-obese phenotypes: role in prediction of incident pre-diabetes in a longitudinal biracial cohort. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2017;5:e000415. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2017-000415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chiu KC, Cohan P, Lee NP, et al. Insulin sensitivity differs among ethnic groups with a compensatory response in beta-cell function. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:1353–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.9.1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arslanian S. Insulin secretion and sensitivity in healthy African-American vs American white children. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1998;37:81–8. doi: 10.1177/000992289803700204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morimoto Y, Conroy SM, Ollberding NJ, et al. Ethnic differences in serum adipokine and C-reactive protein levels: the multiethnic cohort. Int J Obes (Lond) 2014;38:1416–22. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2014.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bacha F, Saad R, Gungor N, et al. Does adiponectin explain the lower insulin sensitivity and hyperinsulinemia of African-American children? Pediatr Diabetes. 2005;6:100–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-543X.2005.00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manning A, Highland HM, Gasser J, et al. A Low-Frequency Inactivating AKT2 Variant Enriched in the Finnish Population Is Associated With Fasting Insulin Levels and Type 2 Diabetes Risk. Diabetes. 2017;66:2019–32. doi: 10.2337/db16-1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Das SK, Sharma NK, Zhang B. Integrative network analysis reveals different pathophysiological mechanisms of insulin resistance among Caucasians and African Americans. BMC Med Genomics. 2015;8:4. doi: 10.1186/s12920-015-0078-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koh H-CE, Patterson BW, Reeds DN, et al. Insulin sensitivity and kinetics in African American and White people with obesity: Insights from different study protocols. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2022;30:655–65. doi: 10.1002/oby.23363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ashcroft FM. KATP Channels and the Metabolic Regulation of Insulin Secretion in Health and Disease: The 2022 Banting Medal for Scientific Achievement Award Lecture. Diabetes. 2023;72:693–702. doi: 10.2337/dbi22-0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duckworth WC, Bennett RG, Hamel FG. Insulin degradation: progress and potential. Endocr Rev. 1998;19:608–24. doi: 10.1210/edrv.19.5.0349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Najjar SM, Perdomo G. Hepatic Insulin Clearance: Mechanism and Physiology. Physiology (Bethesda) 2019;34:198–215. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00048.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ferrannini E, Wahren J, Faber OK, et al. Splanchnic and renal metabolism of insulin in human subjects: a dose-response study. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 1983;244:E517–27. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1983.244.6.E517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Najjar SM, Caprio S, Gastaldelli A. Insulin Clearance in Health and Disease. Annu Rev Physiol. 2023;85:363–81. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-031622-043133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bizzotto R, Tricò D, Natali A, et al. New Insights on the Interactions Between Insulin Clearance and the Main Glucose Homeostasis Mechanisms. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:2115–23. doi: 10.2337/dc21-0545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee WH, Najjar SM, Kahn CR, et al. Hepatic insulin receptor: new views on the mechanisms of liver disease. Metab Clin Exp. 2023;145:155607. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2023.155607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Galderisi A, Polidori D, Weiss R, et al. Lower Insulin Clearance Parallels a Reduced Insulin Sensitivity in Obese Youths and Is Associated With a Decline in β-Cell Function Over Time. Diabetes. 2019;68:2074–84. doi: 10.2337/db19-0120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee CC, Haffner SM, Wagenknecht LE, et al. Insulin clearance and the incidence of type 2 diabetes in Hispanics and African Americans: the IRAS Family Study. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:901–7. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Semnani-Azad Z, Johnston LW, Lee C, et al. Determinants of longitudinal change in insulin clearance: the Prospective Metabolism and Islet Cell Evaluation cohort. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2019;7:e000825. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2019-000825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.