Abstract

Background

Engaging fathers(to-be) can improve maternal, newborn, and child health outcomes. However, father-focused interventions in low-resource settings are under-researched. As part of an integrated early childhood development pilot cluster randomised trial in Nairobi’s informal settlements, this study aimed to test the feasibility of a text-only intervention for fathers (SMS4baba) adapted from one developed in Australia (SMS4dads).

Methods

A multi-phased mixed-methods study, which included an exploratory qualitative phase and pre-post evaluation of the adapted SMS4baba text-only intervention was conducted between 2019 and 2022. Three focus-group discussions (FGDs) with 19 fathers were conducted at inception to inform SMS4baba content development; two post-pilot FGDs with 12 fathers explored the acceptability and feasibility of SMS4baba implementation; and 4 post-intervention FGDs with 22 fathers evaluated SMS4baba programme experiences. In the intervention phase, 72 fathers were recruited to receive SMS4baba messages thrice weekly from late pregnancy until over six months postpartum. A pre-enrolment questionnaire captured fathers’ socio-demographic characteristics. Pre-post surveys were administered telephonically, and outcome measures evaluated using a paternal antenatal attachment scale, generalised anxiety disorder scale (GAD-7), patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9), and researcher-developed questionnaire items assessing paternal involvement, childcare and parenting practices. Qualitative data were analysed using a thematic approach. Statistical analysis performed included descriptive statistics, tests of association, and mixed model regression to evaluate outcomes.

Results

Fathers perceived SMS4baba messages as educational, instilling new knowledge and reinforcing positive parenting, and helped fathers cope with fatherhood transition. High levels of engagement by reading and sharing the texts was reported, and fathers expressed strong approval of the SMS4baba messages. SMS4baba’s acceptability was attributed to modest message frequency and utilising familiar language. Fathers reported examples of behaviour change in their parenting and spousal support, which challenged gendered parenting norms. Pre-post measures showed increased father involvement in childcare (Cohen’s d = 2.17, 95%CI [1.7, 2.62]), infant/child attachment (Cohen’s d = 0.33, 95%CI [-0.03, 0.69]), and partner support (Cohen’s d = 0.5, 95%CI [0.13, 0.87]).

Conclusion

Our findings provide support for father-specific interventions utilising digital technologies to reach and engage fathers from low-resource settings such as urban informal settlements. Exploration of text messaging channels targeting fathers, to address family wellbeing in the perinatal period is warranted.

Trial registration

This study was part of the integrated early childhood development pilot cluster randomised trial, registered in the Pan African Clinical Trial Registry on 26/03/2021, registration number PACTR202103514565914.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-024-21057-9.

Keywords: Early childhood development, Fathers, Kenya, Parenting, Pilot feasibility study, mHealth intervention, Mixed methods research, Urban informal settlements

Introduction

Involving male partners in reproductive health can have significant benefits for maternal, newborn and child health (MNCH) [1]. The World Health Organisation (WHO) has recommended involving fathers, stating that next to improving health care, “the inclusion of fathers is important, as they can play a role as caregivers to the newborn, and as a source of support for the mother” [2, P17]. Systematic reviews examining male partner involvement in reproductive healthcare include numerous studies from sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) reporting a positive association between men’s active engagement in the pregnancy, birth, and postnatal period and improved MNCH [3–5].

However, across low-and middle-income countries, increasing fathers’ support for the woman’s physical and mental health during pregnancy and birth, and increasing his involvement in care of infants, and support for the mother post-birth has been difficult to scale up beyond the research phase [6]. While interventions across SSA have shown promising results, these interventions most commonly address specific maternal health issues such as breastfeeding, HIV testing and care, or having a skilled birth attendant [7–9]. There is limited understanding of effective methods for recruiting and engaging fathers and systematic reviews of interventions have found limited attention to gender norms, decision-making surrounding birth and infant care, and a reliance on intervention modalities of interactive counselling and peer learning [10–13].

The widespread use of mobile phones and the development of mHealth technologies has provided a means to deliver educational health information and support to low-resourced settings at relatively low cost and avoiding the limitations of staffing and infrastructure availability [14]. Mobile phone use in Kenya has increased considerably over recent years, with an estimated 65 million mobile phone cellular subscriptions in 2022 [15]. Interventions aiming to improve MNCH have been piloted across urban and rural areas of Kenya [16–18], including in the informal settlements of Nairobi, and demonstrated improvement in knowledge on parenting and early childhood development [18], and increasing antenatal care service utilization [19]. Recent evidence in Kenya on father-inclusive interventions demonstrate the protective factor of father involvement on maternal depressive symptoms [20], increased father support in parenting, however there are mixed findings on the effect of these interventions on child-related outcomes such as engagement in stimulating activities [21]. Despite the growing evidence, the potential of leveraging mHealth interventions to engage fathers in MNCH in the African context remains under researched, particularly during the first 1,000 days of a child’s life. mHealth interventions may offer opportunities to communicate with fathers over the perinatal period to influence their understanding, and engagement in the care for their pregnant partners, and the developmental needs of infants and young children.

The present study

The aim of this study was to adapt a mHealth father-specific service developed in Australia (SMS4dads) for the Kenyan context and investigate the acceptability and feasibility of the adapted mHealth intervention SMS4baba. The SMS4dads programme was deemed suitable for adaptation given its digital method of delivery and its primary focus on supporting fathers transitioning into parenthood. An evaluation of the SMS4dads text-only intervention demonstrated the potential to improve paternal mental health and emotional regulation postpartum, as well as increase father-child attachment and partner support, while demonstrating good retention and relative low implementation costs [22]. The present study aimed to evaluate the effect of the adapted text-only SMS4baba intervention, on paternal and childcare involvement, parenting, and father wellbeing outcomes in a Kenyan urban informal settlement.

Methods

Methodology

The present study was part of the integrated early childhood development pilot cluster randomised trial, registered in the Pan African Clinical Trial Registry on 26/03/2021, registration number PACTR202103514565914. The formative phase of the parent study has been described in detail in a separate publication [23]. The pilot RCT implementation and findings will be reported separately in future publications. The present study incorporated a post-positivism paradigm to allow for multiple approaches in studying a phenomenon using quantitative and qualitative methods [24]. The study was also framed in a social constructivism paradigm to explore the end-users’ social realities and experiences with the SMS4baba intervention [24].

Study design

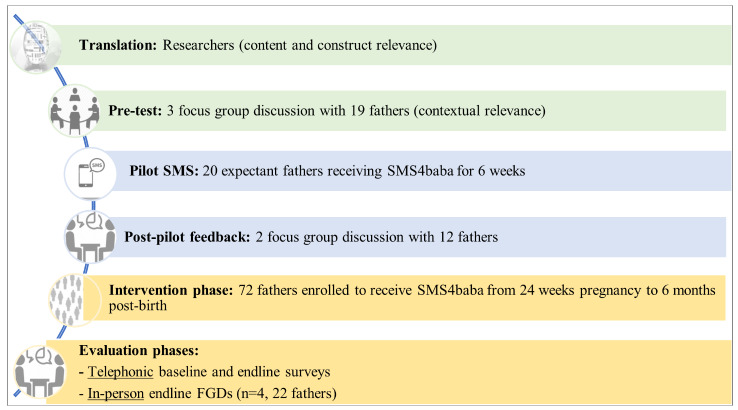

A multi-phased mixed methods study design applying both sequential and concurrent qualitative and quantitative data collection approaches [24]. Data were collected between 2019 and 2022 in the following distinct phases: (i) a qualitative phase involving the adaptation, translation, and pre-test of the Australian SMS4dads to the Kenyan SMS4baba text-only intervention between July and October 2019; (ii) pilot (quantitative) and qualitative evaluation of the adapted SMS4baba between November 2019 and March 2020, followed by harmonization and assembling of the SMS4baba content for the intervention phase between April and December 2020. The intervention (quantitative phase) and post-intervention qualitative evaluation phases of the SMS4baba programme were conducted between January to December 2021, and March to April 2022 respectively. Figure 1 illustrates SMS4baba adaptation and implementation study phases.

Fig. 1.

Illustration of SMS4baba adaption and implementation process

Study setting

The study reported here was conducted in the informal settlements of Dagoretti sub-county, which is approximately 12 km from the capital city, Nairobi. The informal settlement is of relatively poor amenities such as limited access to piped water, deficient sewage system, while housing is a combination of crowded tinned shelters and semi-permanent houses [23]. The population consists of both Kenyans and refugees from neighbouring countries. Data from a survey of 576 households in this setting indicates most males work in the informal economy as casual labourers, and the majority of Kenyan households are male-headed (84%), compared to refugee households (67%) [25].

Study population and sampling procedures

We engaged males above 18 years, who had expectant partners in the 24th week or 6-month trimester and were residents in the informal settlements of Dagoretti sub-county. For the pre-test and pilot phases, community health volunteers (CHVs) assisted in identifying eligible fathers (to-be) meeting the study inclusion criteria during household visits and referring them to the research field office in Kawangware, where trained staff went through the eligibility check, consent, and administered a pre-enrolment survey. During the intervention phase, fathers(to-be) were contacted through their pregnant spouses/partners in the intervention arm of the main study (the integrated ECD intervention), who gave consent and shared contact details of their partners to be approached by the study team. At the endline evaluation, all 58 fathers were informed of the post-intervention focus group discussions (FGDs), and those who expressed interest were recontacted and appointments booked based on their availability. Each FGD targeted a maximum composition of eight participants and an estimated four FGD rounds were planned to allow for maximum reach.

Overview of the SMS4baba programme and adaptation process

SMS4dads is an evidence-based, theory-informed mHealth intervention, developed and piloted in Australia [22]. The intervention consists of a set of 173 brief (160 character) text messages delivered to fathers’ mobile phones, with no end-user cost, from the 20th week of the pregnancy until the infant is 24 weeks of age. Message content addresses the fathers’ relationship with his baby (n = 72), his relationship with and support of the baby’s mother (n = 52), and his own self-care (n = 49). The intervention model aims to promote father-infant attachment and co-parenting, integrating components targeting couple relationships, and parent-child relationships. Most of the messages use ‘the voice’ of the baby to emphasise the fathers’ connection to the baby. The process of adapting the original SMS4dads (Australia) to the Kenyan SMS4baba involved a series of activities summarised in Fig. 1, while Table 1 describes the focus group discussion sample characteristics.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics of focus-group discussion participants

| Pre-test FGDs (n = 3, 19 fathers) | Post-pilot FGDs (n = 2, 12 fathers) | Post-intervention FGDs (n = 4; 22 fathers) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nationality | All Kenyans | All Kenyans | 19 Kenyans, 3 non-Kenyans |

| Mean age (range) | 31 (22–49) | 35 (20–60) | 33 (22–43) |

| Highest Education | |||

| Primary and below | 15.8% (3) | 8.3% (1) | 31.8% (7) |

| Secondary | 47.4% (9) | 75% (9) | 59.1% (13) |

| Tertiary level | 36.8% (7) | 16.7% (2) | 9.1% (2) |

| Occupation | |||

| Student | 10.5% (2) | 0 | 0 |

| Unemployed | 15.8% (3) | 8.3% (1) | 0 |

| Professional/technical worker | 5.3% (1) | 16.7% (2) | 0 |

| Sales and services | 42.1 (8) | 0 | 40.9% (9) |

| Skilled manual worker | 0 | 8.3% (1) | 13.36% (3) |

| Unskilled manual worker | 5.3% (1) | 50% (6) | 13.36% (3) |

| Casual/daily labourers | 21.1% (4) | 16.7% (2) | 31.8% (7) |

| First-time fathers | 47.37% (9) | 50% (6) | 36% (8) |

| Preferred SMS language (English) | N/A | 75% (9) | 64% (14) |

| Have access to internet | 79% (17) | 83.3% (10) | 72.7% (16) |

| Have mobile phone applications (e.g. Whatsapp) | 79% (15) | 58.3% (7) | 72.7% (16) |

| Have facebook account | 79% (17) | 75% (9) | 77.3% (17) |

| Smoking status* | N/A | N/A | 4.54% (1) |

| Alcohol status* | N/A | N/A | 9.1% (2) |

*This question item was only asked to fathers in the intervention phase

Translation phase

The original set of SMS4dads messages were translated to Swahili, one of the official languages in Kenya, by researchers at the Aga Khan University Institute for Human Development. A forward and backward translation approach were used to ensure the construct and cultural relevance were maintained, for example, replacing idioms with phrases of conceptual equivalence.

Pre-test phase

Translated messages of the Australian SMS4dads were presented in three focus group discussion (total of 19 fathers), with young men (under 30 years) and older men (above 30 years) who either had an expectant partner or had a child below 6 months. The pre-test aimed to assess the acceptability and contextual appropriateness of SMS4baba text-only intervention, and further refine the message for use in the Kenyan context. During the pre-test FGD sessions were organised in two parts: (i) to explore perceptions of mobile phone use and health topics men would like to receive on their phones; and (ii) an interactive discussion with fathers who reviewed the Swahili messages and provided feedback on areas for improvement e.g. alternative translations, areas of emphasis etc.

The pilot phase

This phase aimed at better understanding the feasibility and process of rolling out the adapted SMS4baba text-only intervention on a smaller population. We enrolled 20 Kenyan fathers with partners in the last trimester of their pregnancy. Forty messages were disbursed three times weekly for over a six weeks’ period from the University of Newcastle Australia platform to participant’s mobile phones. Message content focused on the pregnancy/prenatal phase. At the end, we invited participants to two focus group discussions (total 12 fathers) where they shared their experiences of the SMS4baba pilot programme.

Intervention phase

This phase targeted partners of pregnant women enrolled in the integrated ECD intervention arm of the parent study, and had provided consent for their partners to be contacted for recruitment in the SMS4baba programme. SMS4baba messages were timed based on the partners expected delivery date to ensure relevance. The fathers (to-be) continued to receive messages until over six months’ post-birth. Fathers were mainly engaged telephonically in all evaluation activities and invited for face-to-face focus group discussions after the endline evaluation.

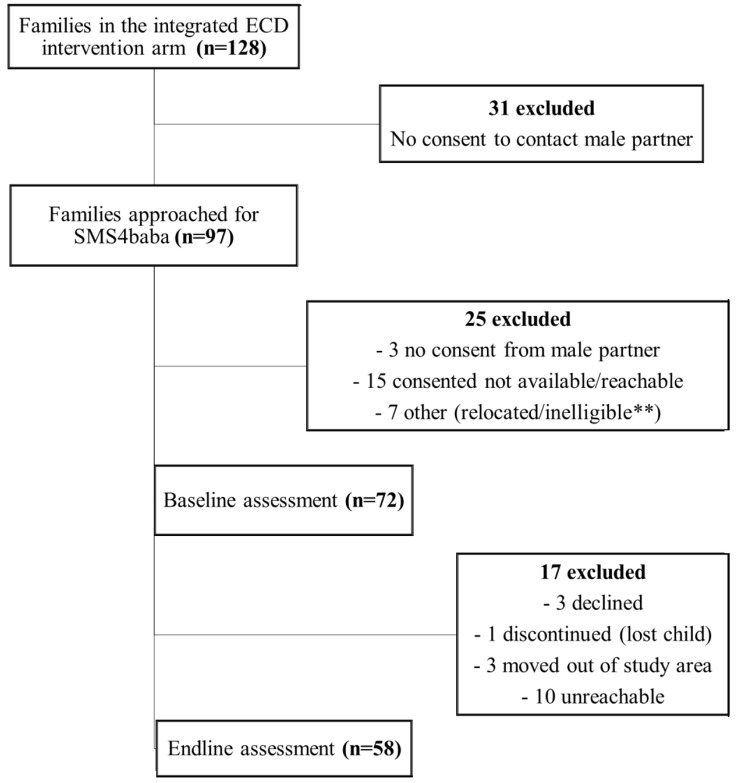

SMS4baba intervention phase flow chart

Figure 2 depicts the recruitment process of the prenatal fathers for the SMS4baba intervention. Ninety-seven fathers were assessed for eligibility, but 25 participants were excluded from the study because some did not consent, some consented but opted not to be engaged further, and some were ineligible. Seventy-two prenatal fathers completed the baseline assessment, and 58 (80.6%) completed the end of study (endline) evaluation. Seventeen fathers were not assessed at the endline evaluation; three declined to be engaged further, one had lost a child, three had moved out of the study area, and ten were unreachable for the endline evaluation. As a result, the pre-post data analysis only included 58 fathers.

Fig. 2.

SMS4baba intervention phase flowchart

Data collection procedures

Qualitative approaches

Topic guides were developed for the focus group discussion with fathers in the different study phases – see sample guides in Supplementary File 1. During pre-test FGDs, the topics explored views on mobile phone use, programme content and communication formats; a pre-test of the translated Swahili messages in an interactive discussion; as well as general remarks on the programme. During post-pilot and post-intervention FGDs, the focus was mainly to explore father’s experiences with the intervention, acceptability, and feasibility of its implementation. For instance, questions explored fathers’ level of engagement through reading messages, likes or dislikes of the programme, feedback on the programme’s value to fathers – see examples in Supplementary File 1. The FGDs were conducted by trained research assistants conversant with interviewing skills. All FGDs were audio-recorded and later transcribed verbatim in the original spoken language (English and/or Swahili) by the research assistants.

Quantitative approaches: study instruments and variables

Socio demographics

Participant’s socio demographics were obtained from a pre-enrolment survey form developed by the researchers. Details collected included; age, nationality, religion, marital status, living status with their expectant partner, occupation, educational level, alcohol and smoking status, and number of children. Information on mobile phone usage was also collected, that is; phone ownership, preferred contact to receive SMS and an alternative contact if unreachable, phone internet connectivity, enrolment in social media platforms such as WhatsApp and Facebook - with an interest to explore other potential engagement mechanisms with fathers.

Paternal antenatal attachment scale (PAAS)

The PAAS is a 16-item scale, which assesses the paternal quality of attachment and time spent in attachment mode to the foetus or infant [26]. Cross-cultural validation studies have been conducted to establish the psychometric properties of the original PAAS and reported a 13-item scale to be reliable in measuring parent-foetal bonding [27–29]. Similarly, for the Kenyan context items 6 and 13 were dropped from the original scale because they did not load well in the factor analysis, while item 16 was dropped because it asked about pregnancy loss, which may be perceived as sensitive and culturally or contextually inappropriate question to administer in the study setting. The total PAAS score was calculated by adding the remaining 13 items, and higher scores reflected the quality and strength of the father’s subjective experience with the foetus or infant.

Paternal involvement

The paternal involvement is a 10-item researcher-developed scale for this study, which assesses the paternal/male caregiver involvement and parenting responsibilities, which has not been previously validated. The item focused on how a father or male partner supports their expectant partner and child before and after their child’s birth. Due to the multiple rounds of assessment pre and post-birth, scale items wording were rephrased slightly to signify if the activities were with the unborn (baseline assessment), or with the baby (endline assessment). Items included engaging in play and communication activities with the baby, supporting breastfeeding and feeding the baby, contributing to household and educational expenses, accompanying the expectant mother to maternal and child health clinics, offering emotional support and encouragement, and providing disciplinary measures for the child’s behaviour. The scale was scored on a 5-point Likert scale rating from hardly ever “0” to very often “5”. The individual items were added to create a total score for paternal involvement, with higher scores indicating greater levels of paternal involvement – see Supplementary File 2.

Childcare and parenting practices score

This is a 3-item scale developed for this study to assess how male partners engaged with the un(born) baby during pregnancy and post-birth. Items included male partner/fathers’ engagement in early stimulation activities such as storytelling or reading to the baby, talking or singing to the baby. The answers to the items were assigned a value of “1” for “yes” and “0” for “no”. Scores for each item were added to create a total score, where higher scores indicated greater involvement in childcare and parenting practices – see Supplementary File 2.

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD-7)

The GAD-7 is a 7-item scale for assessing the general paternal anxiety over a two-week period. The Swahili version of the GAD-7 scale has been validated among adults in the Kenyan Coast [30], and demonstrated it is a reliable measure for use in a study within the informal settlements [31]. The items are scored on a Likert scale of “0” (not at all) to “3” (nearly every day). The total score was computed by summing up responses for all seven items. The resulting score could range from 0 to 21, with scores of 0–4, 5–9, 10–15, and > 15 indicating no anxiety, mild anxiety, moderate anxiety, and moderate to severe anxiety, respectively.

Patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9)

Paternal depression over the previous two weeks was assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) scale. The Swahili version of the PHQ-9 has been adapted and validated among Kenyan adults [32], and further demonstrated good psychometric properties in a study within the informal settlements [31]. This scale comprised of nine items, with responses recorded on a Likert scale ranging from “Never” (scored as 0) to “Almost every day” (scored as 3). All nine items were summed, and a higher total score indicated a more severe level of depression.

Data management and analysis

Qualitative data analysis

Audio-recorded focus group discussions were transcribed verbatim in the original spoken language (English or Swahili) by trained research assistants (EN, EK, EO, and MMM). We applied Braun and Clarke’s thematic analysis approach, given it is theoretically flexible, relatively accessible, and allows for summarising key features of large data, and provides ‘thick descriptions’ of datasets [33]. The first step involved data familiarisation by reading a subset of transcripts line by line to identify a priori/emerging themes, and generated deductive codes based on topic guide questions. VA and EN were involved in this step and developed the initial codebook. Thereafter, anonymised transcripts were imported into NVivo-Lumivero Windows© (QSR international) for coding, which was done by VA with extensive qualitative research training. The coded segments were reviewed by VA and RF to identify, refine, and name themes for presentation in this manuscript. This allowed for incorporating both the insider (in-country research team) perspectives of the research context, and outsider (RF) perspective of SMS4dads international implementation experiences. The rest of the authors provided feedback on the interpretation of the reported findings. Rigour and trustworthiness during the analysis process were observed through maintaining a coding journal for ease of tracking the process. Additionally, in the selection and presentation of quotes we strived for a spectrum of views, for instance, participants’ characteristics and including both dominant and minority views. In Supplementary File 3, we further describe the researchers’ positionality and reflexivity in the research process using the Standard Reporting for Qualitative Research (SRQR) checklist.

Quantitative data analysis

The paternal baseline socio-demographic characteristics (age, nationality, religion, marital status, living with a partner, occupation, level of education, alcohol/smoking status and number of children) were summarized using mean and standard deviation for continuous variables, and proportions for categorical variables. An independent t-test and chi-square test were performed to evaluate the differences in continuous and categorical socio-demographic characteristics between fathers expecting their first child versus non-first-time fathers, respectively.

The internal consistency of the Likert scales at pre-intervention (Paternal involvement, PAAS, GAD-7 and PHQ-9) were assessed using Cronbach’s alpha and MacDonald omega. Both Cronbach’s alpha and MacDonald’s omega were utilised because both measures can provide a complete picture of the internal consistency of a scale. Cronbach’s alpha assumes tau-equivalence, meaning that all items in the scale measure the same underlying construct and have equal factor loadings, while MacDonald’s omega considers each items to have distinct factor loadings [34]. The values of alpha and omega above 0.7 indicated good internal consistency [34, 35]. The paired T-test was used to assess the effect of pre- and post-intervention on paternal involvement, paternal antenatal attachment, and childcare/parenting practices.

The random intercept model was adopted to account for the correlation between the repeated measurements (that is, paternal involvement and childcare/parenting practices) by including the individual study identifiers as a random intercept. The random intercept model was used to assess the pre-intervention socio-demographic characteristics, paternal antenatal attachment, depression, and generalized anxiety associated with paternal involvement and childcare/parenting practices, respectively.

Internal consistency for study measures

Table 2 summarizes the Cronbach’s alpha and Macdonald omega of the paternal involvement scale, Paternal Antenatal Attachment Scale (PAAS), Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7), Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), and childcare and parenting practices measures used for this study. The results revealed that the paternal involvement scale, PAAS, and PHQ-9 had good internal consistency with alpha and omega above 0.70. The internal consistency of GAD-7 and childcare and parenting practices measures were also within acceptable range.

Table 2.

Internal consistency of SMS4BABA measures at baseline assessment

| Scales | Alpha (95% CI) | Omega (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Paternal involvement | 0.77 (0.77–0.88) | 0.73 (0.41–0.80) |

| Paternal Antenatal Attachment Scale (PAAS) | 0.76 (0.67–0.84) | 0.71 (0.46–0.84) |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) | 0.69 (0.59–0.80) | 0.73 (0.62–0.81) |

| Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) | 0.81 (0.79–0.84) | 0.80 (0.66–0.87) |

| Childcare and parenting measure | 0.65 (0.53–0.77) | 0.71 (0.57–0.79) |

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Aga Khan University ethics review committee (004-ERC-SSHA-19-EA) and received clearance from the National Commission for Science Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI/P/1950782/31710), and by the Mount Sinai Hospital’s Research Ethics Board (20-0061-E). Additional approvals were obtained from the Nairobi County Directorate of Health, and the sub-county Ministry of Health Dagoretti sub-county. Study participants in the qualitative component of the study provided written informed consent, while telephonic consent was obtained for fathers involved in the intervention phase. All study participants were provided with a detailed description of the study, its benefits, risks, confidentiality, data storage, and management plans. All participants had a chance to ask questions and seek clarifications prior to their involvement.

Results

SMS4baba adaptation process findings

During the three pre-test FGDs with 19 fathers, they expressed a desire to learn more on a variety of topics, for instance; mental health, father-child relationship, pregnancy facts/knowledge, and preparing for the baby many of which were included in the Australian message set. Fathers also placed emphasis on the need for the SMS content and tone of message to offer practical advice to problems that fathers were undergoing such as handling stress, suggest ‘actions’ for the father, and have messages that address men. In the example below an action was added (underlined) following feedback in the pre-test FGDs.

4baba: Breastfeeding. Great for baby’s health and development, good for mum, and easy on the wallet. [Encourage mum to breastfeed and support her to get help when facing difficulties.]”.

Other feedback focused on improving the SMS language and Swahili translation. Due to the informal settlement context, fathers suggested using everyday spoken language, by either adding ‘slang’ or addition of English phrases for words that were difficult to translate to Swahili without losing its conceptual equivalence. During the translation and harmonisation process, idioms were removed and problematic phrases simplified, and ensured the tone of the messages were appropriate for the fathers. A sample of the original SMS4dads messages and the harmonised translated SMS4baba messages after field-testing, with the proposed modifications in underlined text, that were included in the intervention phase are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Original Australian SMS4dad messages adapted to Kenya’s SMS4baba messages

| Original Australian SMS4dad message | Harmonized back-translated adapted SMS4baba message in English | Adapted SMS4baba message in Swahili |

|---|---|---|

| Welcome | Welcome, thank you for enrolling to the SMS4Baba program. You will soon start receiving messages. Some messages will have links to additional resources. In case you have questions you can contact us through mobile phone number: +254XXX or visit our office, XXX at XXX Building… | Karibu, asante kwa kujiunga na programu ya SMS4Baba. Utaanza kupokea jumbe hivi karibuni. Jumbe zingine zitakuwa na links/muongozo ili upate habari zaidi. Ukiwa na swali wasiliana na sisi kwa nambari ya simu + 254XXX au tembelea ofisi yetu XXX at XXX Building… |

| 4dad: When tired or stressed parents sometimes think a crying baby is trying to upset them. Its OK dad, try to keep your cool. I’m just doing what babies do. | 4dad: “Dad, when you are tired or stressed you might think when I am crying, I am trying to upset you. It is okay dad, try to be patient. It is normal for children to cry as a way of communicating.” | “Baba, wakati umechoka, ama una mawazo mengi, waweza fikiria kuwa nikilia najaribu kukukasirisha. Ni sawa baba, jaribu kuwa na subira. Ni kawaida kwa watoto kulia kama njia ya kuwasiliana.” |

| 4dad: It is a myth that women know how to be a mother from instinct. This myth might make mums feel bad when things are not going well. | 4dad: It is a myth that women know how to parent from instinct. Such beliefs are not true and they might make mums feel bad when things are not going well during parenting. Dad, try and help mum to care for me well. | Watu huamini kuwa wanawake wanajua kulea watoto kupitia instinct. Imani kama hizi sio za ukweli na zinaweza fanya kina mama wahisi vibaya wakati kuna shida za malezi. Baba, jaribu umsaidie mama kunilea vyema. |

| 4dad: Feeling irritable or angry can be a sign of anxiety or depression. See your doctor if you are worried about these feelings. | 4dad: Feeling irritable or angry can be a sign of anxiety or depression. Try take a walk and clear your mind, or seek doctor’s advice if overwhelmed by these feelings. | Kuwa na hasira inaweza kuwa dalili ya huzuni/depression.Tafadhali jaribu kutembea nje kupata hewa na kutuliza akili, au pata ushauri wa daktari ikiwa hisia hizi zimezidi. |

| 4dad: My nervous system is ready to go. I may be startled by loud noises and I might even turn my head toward the sound of your voice. | 4dad: My nervous system is ready to go. I may be startled/shaken by loud noises outside mum’s womb. Dad, I might kick or turn my head toward the sound of your voice. Try and talk to me. | “Nervous system yangu (mfumo wa kuwasiliana mwilini) iko tayari. Ninaweza kushtuliwa na kelele kubwa nje ya tumbo ya mama. Baba, naweza kukick ama kuelekeza kichwa changu upande wa sauti yako. Jaribu kuzungumza nami.” |

| 4dad: Braxton-Hicks are practice contractions that get her body ready for labour. Mums usually feel these in the final months of pregnancy. | 4dad: Braxton-Hicks are practice contractions that get her body ready for labour. Mums usually feel these in the final months of pregnancy. If pains persist take expectant partner to hospital. | 4dad: Kufunga na kufunguka kwa misuli ya tumbo la uzazi (Braxton-hicks) ni njia ya mwili kujitayarisha kwa maumivu ya kujifungua (labour). Kawaida, kina mama huhisi hivi miezi ya mwisho ya uja uzito. Mpeleke mama hospitalini maumivu yakizidi. |

| 4dad: Hey dad I am arriving soon. Can you make the commitment to stop smoking? | 4dad: Hey dad I am arriving soon. Can you attempt to try and quit smoking, so I am born in a safe environment? | 4dad: “Habari baba, naja hivi karibuni. Je! Unaweza kujitolea kuacha sigara ili nizaliwe katika mazingira salama?” |

| 4Dad: Hey dad, did you know that drinking alcohol daily can cause health problems. | 4dad: Hey Dad. Did you know that alcohol consumption during pregnancy can cause birth defects e.g. premature birth, low birth weight or disabilities? Please help mum to keep me safe by avoiding taking alcohol. | 4dad: “Habari baba. Je unajua kuwa unywaji pombe wakati wa uja uzito unaeza leta kasoro za kuzaliwa (kama vile kuzaliwa kabla muda, kuwa na kilo kidogo au ulemavu)? Tafadhali msaidie mama anilinde vyema kwa kutokunywa pombe.” |

With regards to the SMS4baba administration, cumulative feedback from fathers in the three pre-test FGDs and two post-pilot FGDs showed fathers preferred to receive messages in moderate frequency; that is, either twice of thrice a week, and preferred messages to be sent during less busy times of the day to cater for working fathers. To incorporate this feedback in the main intervention, messages were disbursed three times weekly, from the University of Newcastle SMS4dads platform to the registered phone contacts of Kenyan fathers.

In the intervention phase, a total of 250 messages were scheduled, which included a set of smoking and alcohol related messages (10 each) disbursed to fathers who indicated their smoking and alcohol intake status at enrolment. Messages were timed to be synchronised with the child’s gestational age and the endpoint was set at a fixed period (31st December 2021) when the child estimated age was above six months’ post-birth.

SMS4baba intervention phase findings

Socio-demographic characteristics

Table 4 summarizes the fathers’ sociodemographic characteristics at the intervention phase baseline assessment. A total of 72 fathers completed the baseline assessment. The average age of fathers was 30.70 (SD = 6.80), ranging from 21 to 48 years. Of the 72 fathers, 23.6% (n = 17) were expecting their first child. Most of the fathers were Kenyans (n = 66, 91.7%), Christians (n = 68, 94.4%), lived with their partners 66 (91.7%), were married (n = 66, 91.7%), and had a secondary level of education (n = 43, 59.7%). Less than one-quarter of the fathers were either smoking or taking alcohol (n = 13, 18.1%). The demographic characteristics of first-time and non-first-time fathers were mostly similar, except for differences in age, where first-time fathers were relatively younger (mean 25.4, p < 0.001).

Table 4.

Baseline sociodemographic characteristics for fathers in the SMS4baba intervention phase

| Expecting first child | Overall (N = 72) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (N = 17) | No (N = 55) | |||

| Age | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 25.40 (3.37) | 32.40 (6.75) | 30.70 (6.80) | < 0.001 |

| Median [Min, Max] | 25.0 [21.0, 32.0] | 31.0 [22.0, 48.0] | 30.0 [21.0, 48.0] | |

| Nationality | ||||

| Kenyan | 15 (88.2%) | 51 (92.7%) | 66 (91.7%) | 0.842 |

| Immigrant | 2 (11.8%) | 4 (7.3%) | 6 (8.3%) | |

| Religion | ||||

| Christian | 17 (100%) | 51 (92.7%) | 68 (94.4%) | 0.860 |

| Islam | 0 (0%) | 2 (3.6%) | 2 (2.8%) | |

| Traditional | 0 (0%) | 2 (3.6%) | 2 (2.8%) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single/never married | 3 (17.6%) | 1 (1.8%) | 4 (5.6%) | 0.126 |

| Single but cohabiting | 1 (5.9%) | 1 (1.8%) | 2 (2.8%) | |

| Currently married | 13 (76.5%) | 53 (96.4%) | 66 (91.7%) | |

| Lives with partner | ||||

| Yes | 13 (76.5%) | 53 (96.4%) | 66 (91.7%) | - |

| No | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Not applicable | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Missing | 4 (23.5%) | 2 (3.6%) | 6 (8.3%) | |

| Occupation | ||||

| Skilled worker | 4 (23.5%) | 14 (25.5%) | 18 (25.0%) | 0.978 |

| Casual labourer/unskilled worker | 12 (70.6%) | 35 (63.6%) | 47 (65.3%) | |

| Unemployed/other | 1 (5.9%) | 6 (10.9%) | 7 (9.7%) | |

| Highest education level | ||||

| Primary and below | 2 (11.8%) | 19 (34.5%) | 21 (29.2%) | 0.462 |

| Secondary | 12 (70.6%) | 31 (56.4%) | 43 (59.7%) | |

| Tertiary | 3 (17.6%) | 5 (9.1%) | 8 (11.1%) | |

| Taking alcohol/smoke | ||||

| No | 14 (82.4%) | 45 (81.8%) | 59 (81.9%) | 0.999 |

| Yes | 3 (17.6%) | 10 (18.2%) | 13 (18.1%) | |

| Number of children | - | |||

| None | 17 (100%) | 1 (1.8%) | 18 (25.0%) | |

| One | 0 (0%) | 28 (50.9%) | 28 (38.9%) | |

| Two | 0 (0%) | 16 (29.1%) | 16 (22.2%) | |

| Three | 0 (0%) | 7 (12.7%) | 7 (9.7%) | |

| Four | 0 (0%) | 2 (3.6%) | 2 (2.8%) | |

| Five | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.8%) | 1 (1.4%) | |

SMS4baba programme experience and intervention impact

Quantitative findings

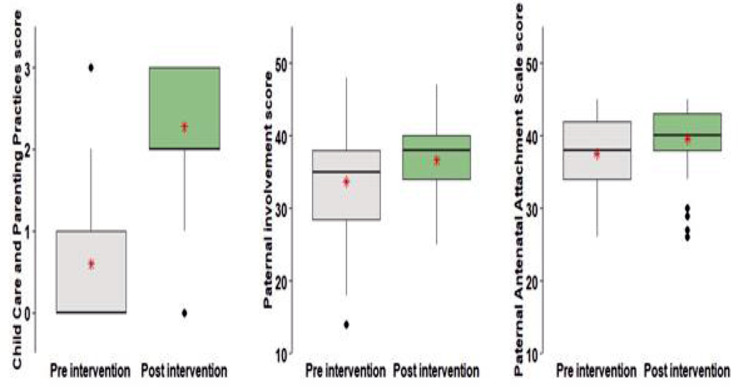

At baseline 72 fathers were enrolled in the SMS4baba programme, and by the endline evaluation 58 (80.5%) fathers were still with the programme, suggesting a good retention in the intervention. Table 5 highlights trends in scores of primary measures at baseline and endline evaluation. The findings indicate exposure to the SMS4baba intervention resulted to improvements in childcare and parenting practices for fathers at the endline assessment (Cohen’s d = 2.17, 95% CI [1.7, 2.62]). Similarly, there was improvement in paternal involvement (Cohen’s d = 0.5, 95% CI [0.13, 0.87]) pre-post intervention. Improvements were observed in the paternal antenatal attachment however this was not statistically significant.

Table 5.

Mean and standard deviation of SMS4baba measures pre and post intervention

| Measure | Pre intervention Mean ± SD | Post intervention Mean ± SD | Paired T test (p value) | Cohen’s d (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Childcare and parenting practices | 0.6 ± 0.781 | 2.28 ± 0.74 | < 0.001 | 2.17 (1.7–2.62) |

| Paternal involvement | 33.67 ± 6.92 | 36.64 ± 4.81 | 0.004 | 0.5 (0.13–0.87) |

| Paternal Antenatal Attachment* | 33.78 ± 14.74 | 37.5 ± 5.28 | 0.053 | 0.33 (-0.03–0.69) |

*NOTE: This pre-post analysis is based on 9 out of 13 PAAS items included in the post-intervention assessment, while taking account of the psychometric properties of the scale items retained

Figure 3 represents boxplots of the childcare and parenting practices, paternal involvement, and paternal attachment measures. The red star represents the mean value, the line in the center represents the median, the upper side of the box is the third quartile, and the lower side of the box is the first quartile.

Fig. 3.

Boxplots of SMS4baba pre-post intervention measures

Paternal involvement, childcare and parenting practices outcomes and their associations with baseline assessment predictors

Table 6 summarizes estimates and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) obtained from the random intercept model. The random intercept model for paternal involvement (r = 0.20) and childcare and parenting practices (r = 0.23) showed observations within fathers were positively correlated. Overall, there was improvement in paternal involvement post-intervention by 2.96 units when compared to pre-intervention (β = 2.96, 95% CI [1.06–4.87], p = 0.004). Paternal attachment was the only significant predictor for paternal involvement. That is, a unit increase in the paternal antenatal attachment corresponded to a 0.11 unit increase in paternal involvement (β = 0.11, 95% CI [0.05–0.18], p = 0.002).

Table 6.

Parameter estimates and 95% confidence interval from the random intercept model

| Level | Variables | Paternal involvement score | Childcare and parenting practices score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (95% CI) | P value | Estimate (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Fixed | |||||

| Individual | Socio-demographic characteristics | ||||

| Age | -0.04 (-0.26, 0.18) | 0.725 | 0.01 (-0.02, 0.04) | 0.522 | |

| Occupation | |||||

| Skilled worker | Reference | ||||

| Casual labourer/unskilled worker | -1.89 (-4.66, 0.86) | 0.182 | -0.25 (-0.61, 0.10) | 0.171 | |

| Unemployed/other | -3.82 (-8.84, 1.22) | 0.145 | -0.68(-1.32, -0.03) | 0.045 | |

| Highest education level | |||||

| Primary and below | Reference | ||||

| Secondary | 0.46 (-2.42, 3.33) | 0.758 | -0.18 (-0.55, 0.19) | 0.348 | |

| Tertiary | 3.16 (-1.68, 8.01) | 0.208 | -0.25 (-0.87, 0.37) | 0.433 | |

| Taking alcohol/smoke | |||||

| No | Reference | ||||

| Yes | -1.00 (-3.94, 1.94) | 0.508 | -0.17 (-0.54, 0.20) | 0.382 | |

| Expecting first child | |||||

| Yes | Reference | ||||

| No | 0.3 (-3.77, 4.37) | 0.885 | -0.71 (-1.23, -0.19) | 0.011 | |

| Number of children | 0.26 (-1.57, 2.1) | 0.781 | 0.06 (-0.17, 0.30) | 0.592 | |

| Paternal antenatal attachment scale (PAAS) | 0.11(0.05, 0.18) | 0.002 | 0.01(0.00, 0.02) | 0.007 | |

| Mental health status | |||||

| Depression score | -0.01 (-0.47, 0.45) | 0.951 | 0.01 (-0.05, 0.07) | 0.723 | |

| Anxiety score | -0.28 (-0.92, 0.36) | 0.395 | 0.04 (-0.04, 0.12) | 0.317 | |

| Intervention Effect | |||||

| Pre-intervention | Reference | ||||

| Post-intervention | 2.96(1.06, 4.87) | 0.004 | 1.69(1.46, 1.92) | < 0.001 | |

| Random | |||||

| Individual | σ2ϵ0 | 2.56 | - | 0.34 | - |

| Group | σ2µ0 | 5.08 | - | 0.62 | - |

Similarly, there was observed improvements in the childcare and parenting practices post-intervention by 1.69 units when compared to pre-intervention (β = 1.69, 95% CI [1.46 – 1.92], p < 0.001). Paternal attachment remained a significant predictor for childcare and parenting practices. That is, a unit increase in paternal antenatal attachment corresponded to a 0.01 unit increase in childcare and parenting practices (β = 0.01, 95% CI [0.00 – 0.02], p = 0.007). However, there was an inverse relation in childcare and parenting practices outcome with the following baseline predictor variables: a 0.71 reduction in scores for first-time fathers when compared to non-first time fathers (β=-0.71, 95% CI [-1.23 – -0.19], p = 0.011); lower scores for unemployed fathers than fathers in skilled employment (β=-0.68, 95% CI [-1.32 – -0.03], p = 0.045). There were no significant associations between paternal involvement, childcare and parenting practices outcomes with other baseline predictors such as father’s mental health status, alcohol and/or smoking status, educational level, and number of children.

Qualitative findings

The overarching themes presented in this section are broadly categorized as: (i) perceptions around fathers’ level of engagement in the SMS4baba programme; and (ii) the perceived impact of SMS4baba on father-child relations, father well-being, and parenting experiences. Data is drawn from four post-intervention FGDs with 22 fathers and their characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Acceptability - fathers’ reaction to SMS4baba

Fathers expressed that they liked the messages because the content was educational and encouraging. Fathers found each message content different, which made the messages interesting, and they looked forward to reading more. The language used in the messages was easy to understand and kept the father’s attention.

Participant 1: …what I was happy about was the [messages] were written in an understandable and good language. I liked that…the messages were short and that was encouraging because when you have lengthy messages you may read and get to a point and get tired of reading…[FGD01_father_34years_post-intervention].

A father also shared that he liked the messages because he felt they encouraged male inclusion in childcare matters.

Participant 6: what I liked was that even us men were included in the care of our children, because you see most of the times men are not included in [programmes] it is only women…[FGD01_newfather_26years_post-intervention].

Narratives also highlighted how father’s first reacted to being approached to enrol in the mobile-based programme. Some fathers expressed scepticism over the messages and doubted the legitimacy of the programme.

Participant 3: I can attest the time you enrolled my partner in the programme [integrated ECD intervention], I had many doubts and did not know if this was real or false. So, I had to share with my partner and she reassured me this programme [SMS4baba] is genuine.[FGD02_newfather_29years_post-intervention].

Participant 4: When I was first contacted, I wondered are these fraudsters, because nowadays it is common to get such calls…but after talking to my friend I came later to learn this is a good programme[FGD02_father_34years_post-intervention].

Some fathers were puzzled and curious about what the messages communicated about their baby’s development.

Participant 2: …when I received the first messages they were surprising and from the things I read, I later came to see they were true as the baby was growing. I then realized I will need to continue reading the messages…and so I continued learning…[FGD02_newfather_31years_post-intervention].

Participant 4: …I was trying to follow closely the messages, the moment I received I would try and check if what was written in the messages was happening to my baby…the [messages] have really helped me…[FGD04_father_43years_post-intervention].

Feasibility - father’s engagement with SMS4baba

All fathers in the post-intervention FGDs confirmed receiving and reading messages sent to their phones. Reasons for motivating them to read messages included being first time parents or to learn more how to care for their baby.

Participant 6: I read all the messages. The child I was expecting was my first born so I wanted to know more about my child and how I can care for him as a parent.[FGD01_newfather_26years_post-intervention].

Participant 3: I read all the messages because this was my first time as a parent…so I had the desire to know more what to anticipate as my baby develops. So, I was very keen with the messages. I used to go through the [messages] to learn more.[FGD02_newfather_29years_post-intervention].

Participant 1: I read all [messages] and I continued to review them later. I have not deleted any of the [messages] because they were mind-opening. As I continued reading how the baby is developing, I was able to learn more…[FGD02_newfather_37years_post-intervention].

A father spoke of how despite having a busy schedule, he created time to review and catch up with all sent messages because they were educational.

Participant 1: I read all the messages. At times I was busy at work, so I used to find time and go through the [SMS], or when I was idle with my phone, I would look up the messages and I was able to learn a lot through these messages.[FGD03_newfather_42years_post-intervention].

Sharing SMS4baba messages and reasons

Fathers had opportunities to share with other people including spouses, male friends/peers, which involved discussions about the learnings from the SMS or exchanging the messages through text, especially those that were about their partners or babies. Spouses/partners to the fathers were intrigued by the change in the father-child interaction, which on inquiry led to a realization that this was attributed to the SMS4baba messages.

Participant 5: I used a different [approach] of narrating stories to my baby. So, my wife asked me, ‘how come you are telling the baby stories?’ I showed her the messages and when she read, she was happy that I was reading these messages.[FGD01_newfather_22years_post-intervention].

Participant 8: I didn’t share with her [partner] but eventually she saw the messages coming to my phone…when I used to share with her it was through actions, and the messages changed my behaviour. She noticed there is a way these messages were helping me to change…and she started having more affection towards me.[FGD01_father_38years_post-intervention].

Participant 1: I share with her [partner] those [messages] that were about us. For example, one of the messages …asked if I hear the baby playing in the mother’s womb. In that case I had to ask…and she would tell me…the [messages] that were about me I did not see the point of sharing.[FGD03_newfather_43years_post-intervention].

Reasons fathers shared SMS4baba messages with other people such as family members, male friends/peers, neighbours, and other community members were to increase awareness about how to care for babies, as well as change the pre-existing myths and perceptions about male involvement in childcare.

Participant 8: …in my community…most men have the habit of saying parenting is a responsibility for women…but when you share [SMS4baba messages] with such men, they will move away from such mentality and see that the child also belongs to them…[FGD01_father_38years_post-intervention].

Participant 1: …my brother is the type who hardly related with his children, because where we grew up we were told by our elders that you wait for the baby until they reach 10 years so you can carry them…and men are not supposed to enter into the kitchen…I shared with my brother and tried to explain to him the value of these messages, my lessons and changes I have experienced. He started supporting his wife…after work and while relaxing he plays with his children…[FGD03_newfather_42years_post-intervention].

Fathers highlighted the need to share and support other men. This was done during social interactions and some fathers took the initiative of organizing meetings with men to disseminate these messages. For those with expectant partners, messages were shared to help learn and cope with the pregnancy situation. Fathers also saw the value of sharing these messages to increase the knowledge on childcare and parenting tips.

Participant 3: I shared with one of my neighbours…who transports goods with his van and his wife operates a food stall. The wife gave birth to pre-term triplets; two passed on and one survived. So, I shared with him what I learnt [from SMS4baba] and he started reforming. Even now he uses his van to help fetch water to take home and they closed the food stall but worried about what he should do now…I advised him his wife cannot be stressed operating the food stall, having lost two babies…and let her rest for three months, they can continue paying rent for the stall.[FGD03_father_46years_post-intervention].

Participant 4: …the [messages] really helped a lot; I ended up looking for fellow men who did not have a chance to…get the messages. At my workplace I used to share with my male workmates because I felt they were important for fathers. I used to tell them even if they are not married these messages may be helpful in the future…[FGD04_father_43years_post-intervention].

Fathers also had reservations about sharing the messages with others as they felt that the messages they received were personal or that others may disagree.

Participant 2: …I had the stance that these [messages] were meant to be mine alone and my family and so I had no interest in sharing besides to my immediate family…[FGD02_newfather_31years_post-intervention].

Participant 8: …the thing that may cause men not to share the [SMS4baba] messages with others, is the fact that there are those who may think that we are encouraging women not to meet their obligations. You may find if you approach a [male] person, he will tell you that you are trying to get them into women affairs.[FGD01_father_38years_post-intervention].

SMS4baba perceived impact on father-child relation

Fathers emphasized they found the messages helped improve their awareness and the need to strengthen the bond with their child, while in the womb and after they were born. Fathers felt the messages made them look forward to the birth of their child. The messages motivated and prompted fathers to spend more time with their child by setting time aside and having shared engagement e.g. playing games and taking walks together.

Participant 7: It [SMS4baba] was effective since I could focus on work and still get the messages, the information brought me closer to my child[FGD01_father_26years_post-intervention].

Participant 2: Communicating with the baby in the womb. I used to tell the baby, ‘my baby, when you come I will carry you with joy.’ During that time, I used to talk and touch the mother’s womb…[FGD01_father_40years_post-intervention].

Participant 4: the [SMS4baba messages] changed my mind because through playing with the baby I discovered it helps with his brain development…I learnt by playing with the baby…the baby can communicate…if I sing…the baby utters sounds because they are still small but can smile…[FGD04_father_43years_post-intervention].

The messages with the ‘baby’s voice’ were perceived as fun, entertaining, and felt as if the baby was talking to the father, which encouraged them to practice what was communicated through the SMS4baba messages.

Participant 1: …through the messages I learnt a child communicates; when they utter the sounds you may not understand what they are saying but you should imitate and the baby can hear you conversing. This helps nurture the bond between me [parent] and the baby and have close relations. It is not good to just stare when a baby utters sound; when you engage you notice this strengthens your relation and friendship…[FGD02_newfather_37years_post-intervention].

Participant 2: there was a message, ‘dad when you see me approaching you, touching you, it is because I want to play with you. Please do not move away…,’ it read something like that and I imagined that. When I read that message, I discovered the baby wanted to play and I did what the chid wanted[FGD02_newfather_31years_post-intervention].

Fathers also reported the SMS4baba programme empowered them with more knowledge and practical skills in handling babies. For instance, how to feed and bath babies, soothing the baby, learning about the importance of exclusive breastfeeding, early identification of a sick child and seeking medical attention through monitoring changes in child breastfeeding. For non-first-time fathers, they reported observing a difference in the knowledge and parenting approach for their expectant child when compared to their other children.

Participant 3: …where I was brought up children are breastfed for two to three months…and then given [solid] food. I am grateful I received the messages…I have learnt babies breastfeed and start food after six months…[FGD02_newfather_29years_post-intervention].

Participant 3: …from these SMS we get new ideas that I never used to know before…even my partner starts wondering about the increased level of affection for the [young] child compared with the others…I just want to spend my time with them, while she does other things.[FGD03_father_46years_post-intervention].

Through SMS4baba, fathers had improved understanding of their children’s growth and development. Since messages were synchronised to the baby’s gestation age, fathers reported learning and being more aware of what to anticipate in their child’s developmental milestones.

Participant 1: …these messages made me aware of changes to anticipate in my baby…I learnt new things, that babies can sleep for five minutes wake up, ten minutes and wake up crying…this is a stage they are going through. After a week or two I notice there was something happening to the baby…[FGD02_newfather_37years_post-intervention].

Participant 2: The messages since if I compare the baby at 2 and 4 months I could see differences…if it is communication…and the child now knows me better…when I get in the house the baby comes to me…and when the baby cries and points at a thing I know the baby wants me to do something…our relationship is growing and we understand each other better…[FGD03_father_25years_post-intervention].

SMS4baba perceived impact on couple relations and co-parenting

A recognized challenge by fathers was the strained communication and relations with their partners during pregnancy. Narratives revealed how the SMS4baba messages helped revive spousal relations, improve communication, and understanding towards their partners. Fathers reported the messages inspired them to spend more time with their partners through shared activities such as taking walks, exercising, and visiting clinics together.

Participant 1: …I used to think clinic matters are for women but when I started receiving the [SMS4baba] messages for the first time, I attended the clinic with my [expectant] partner. I learnt a lot and became informed that the mother, father, and baby are one…and got motivated…we are more united and I don’t worry about escorting her to clinics…[FGD01_father_34years_post-intervention].

A consistent theme was the way SMS4baba messages helped transform their attitudes and break the gender norms and cultural stereotypes. For instance, fathers assisted in household chores, which, in some Kenyan communities are roles perceived to be for women. Other examples mentioned were childcare related, carrying their babies in public, assisting in feeding, bathing and changing clothes/diapers.

Participant 3: the [message] I remember mentioned about helping your partner because childcare responsibilities can be overwhelming and the mother can get stressed up…so if you leave all the responsibilities with her she may get depressed …so I read the message and if I do not have something to do outside I don’t even leave the house; I stay at home the whole day just to assist her…[FGD03_father_46years_post-intervention].

Participant 4: they [SMS4baba messages] helped change our mind-sets because I used to think we leave all the work for women to do…I came to learn I need to help with work; when she is washing clothes I could take the baby, and if the baby is hungry I help out with feeding the baby and saw this was a good thing…[FGD01_father_30years_post-intervention].

SMS4baba perceived impact on father wellbeing

Fathers reported through the messages they learnt more about self-control and managing emotions associated with stressors of pregnancy and fatherhood. They also found the messages instilled hope and encouragement, which they felt helped immensely to deal with livelihood challenges and as they transitioned into fatherhood.

Participant 2: I have learnt many things that I never knew before. I used to go out and spend time with friends. Now I tell them I have to go home because I have a baby and my wife who delivered through CS [caesarean section] I need to focus on home…[FGD01_father_40years_post-intervention].

Participant 5: I learnt if angry or have come from work angry, do not carry the anger with you home …[FGD01_newfather_22years_post-intervention].

Participant 1: I remember the message that was about the baby that read, ‘if the baby cries a lot and starts to make me feel angry, I put the baby somewhere safe I first calm down and later carry the baby’…the message made me know how to stay with the baby when in distress and know how to act. You know for a small baby if you say you will cane a small baby, they will not understand why…instead you go look for the mother and look for a place to put the baby as long as they don’t get injured as I think of what to do next…[FGD03_newfather_42years_post-intervention].

Some messages were reported to help encourage fathers to take care of themselves; exercising, quitting smoking or drinking, and other lifestyle related changes as well. The messages were motivational and inspired them to be hardworking and supportive of their family.

Participant 3: …regarding exercise, when my wife was expectant, I personally enforced this because I understand even as she works, I don’t just sit…I used to exercise…[FGD02_newfather_29years_post-intervention].

Participant 1: …One way of exercising is to help out with household chores like fetching water, washing clothes…even helping with cooking. When engaged in house chores I find I am exercising, and this is something I am doing through this [SMS4baba] programme.[FGD02_father_43years_post-intervention].

Discussion

Summary of findings

In this feasibility study, the Australian SMS4dads text-only programme was adapted and contextualised for use in the Kenyan setting (SMS4baba), where collectively in all study phases, almost 100 fathers in Nairobi’s informal settlements interacted with the intervention. Using a multi-phased mixed-methods design, this study is the first of its kind within the African context to assess the acceptability and feasibility of a text-only intervention with parenting messages targeting expectant fathers during pregnancy and through the baby’s first year of life.

Qualitative reports demonstrate SMS4baba was perceived as informative, helped fathers cope with fatherhood challenges, and messages strengthened father-child relations, and support for their partners in taking up responsibilities, which challenged gendered norms. Pre-post evaluation of the SMS4baba intervention demonstrated positive effects on father-child attachment and father involvement in childcare. Here we reflect on the implication of the study findings on father inclusion in maternal newborn and child health interventions or programmes in low-resource settings.

Implication of findings for research, policy, and practice

Our study highlights the successful adaptation of an mHealth intervention for fathers focusing on the perinatal and postpartum periods, by ensuring that the adapted program was contextually appropriate and involved the end-users, in this case fathers, in the process [36]. Feedback from fathers helped shape the message content and guided the delivery format in frequency, timing of messaging and language (Swahili or English). For instance, emphasising cues for fathers’ actions directed to self, baby, and in supporting their expectant partners/mothers. The high retention rate and the indications of behaviour change in the father’s descriptive responses also suggests a practical approach to changing gender norms, based on a father’s investment in his infant’s wellbeing, utilising widely available, low-cost technology.

The SMS4baba programme was positively appraised by both first-time fathers and non-first time fathers, with qualitative and quantitative findings confirming the intervention was acceptable and feasible for implementation in a low-resource setting. This was attributed to the design features including the specific targeting of fathers, modest frequency of messages based on fathers preferred time to receive text, utilising familiar language, and the brevity of the texts. The level of engagement with the program is another indication of acceptability [37, 38]. Our findings show 80% retention over almost a one-year period, and based on fathers’ self-reports, all received and consistently read and retained messages, shared with others including spouses, males/peers to pass on the learnings from the intervention.

Importantly, SMS4baba messages were viewed as educational, instilling new knowledge and connecting with fathers’ experiential knowledge. The messages were instrumental in navigating through the various phases of fatherhood, building participants’ competency, and providing a supportive resource for coping with fatherhood challenges [39]. By synchronizing messages to the baby’s gestational age precision in the content was ensured and fathers were able to relate the information shared with their child’s development. Fathers frequently enacted the actions communicated through the messages. For instance, qualitative reports showed the messages prompted fathers to spend more time with their baby through shared engagement such as playing games, communicating with the baby, taking walks together, which can potentially improve father-child attachment and provide an important precursor to promoting a nurturing and thriving environment for these young children [40, 41]. The positively styled messages ‘just for fathers’ provided validation for an engaged role and innovations such as crafting messages with the voice of the baby intrigued fathers and provided visual imagery of the developing baby, which also may help strengthen father-child attachment. Findings from the Australian SMS4dads intervention indicate this approach encourages fathers to have a virtual conversation with their baby, leading to taking up more responsibilities and involvement in the care for their child, thereby increasing support for the mother [42].

Findings from the pre-post evaluation of the SMS4baba programme show exposure to the intervention had positive effects on father-infant attachment and father involvement in childcare. These findings extend the evidence from the Australian context where, although increased paternal involvement was reported, the programme emphasised paternal mental health detection and referral [43]. Paternal antenatal attachment was a positive predictor for improvement in both outcomes. Being a first-time father was associated with improved parenting practices, though not statistically significant. However, when compared to non-first time fathers, first-time fathers had lower scores on childcare and parenting practices. Plausible explanations to this finding could be first-time fathers were navigating and orienting themselves to the father role, a phase characterised by oscillations in role and identity normalisation [44]. There is also the possibility being first-time fathers, may have prompted them to take up tasks such as taking the infant to the clinic and helping their partner more readily as confirmed in our qualitative findings. Fathers who lack employment were more vulnerable compared to those in stable jobs, which may have an influence on their childcare and parenting practices. A plausible explanation to this finding is that fathers with stable jobs or regular income within this setting may not necessarily worry about meeting their family needs and may have more time to participate in childcare, whereas the unemployed father, getting or securing a job in an informal settlement context may present as a priority and take him away from home for long periods. The small size of this study may limit the interpretation of these findings, and these are areas needing further exploration in future studies.

The SMS4baba text-only intervention serves to bridge an important gap through advancing father’s proactive involvement in child matters especially through expanding their knowledge on child development, nutrition and health, as well as promoting early stimulation through play and communication, which other African studies have identified as important aspects in father involvement in childcare within these settings [18, 21, 45, 46]. An important contribution of this intervention is the demonstration of a low-cost intervention, which can engage fathers across the perinatal period relying on positive messaging to change gendered behaviour [47]. While the perinatal period has been recognised as a time when fathers may be ready to address gendered relationship behaviours which are damaging to the mother and the infant, digital technologies have not been recognised and interventions have relied on group-based, face-to-face delivery models where the gender-inequitable definitions of manhood are explicitly acknowledged [48]. In addition, the ability to reach fathers through their mobile phones may overcome barriers of distance and proximity to facility-based services. Scaling up, and scaling out to other population groups utilising digital technologies may be possible in low-resource settings [49].

Strengths and limitations

This is the first study in the African context to specifically target fathers using digital technology and one of the few fatherhood interventions anywhere recruiting men from communities where basic services are so limited. The SMS4dads materials was adapted to the Kenyan context by engaging fathers from the informal settlements in co-designing the wording of the messages and indicating frequency and timing of the texts. Apart from the retention rate, the qualitative reports capture features of SMS4baba, such as the use of the ‘baby voice’, which makes the programme acceptable, while the quantitative measures for attachment, childcare and parenting practices and paternal involvement provide evidence of changes arising from the program. The strength of this study lies in the triangulation of findings from both quantitative and qualitative sources on the impact of the novel SMS4baba programme. The methodological approach used to evaluate SMS4baba programme acceptability and feasibility may have had its shortcomings and we therefore recommend future research to consider the use of robust measures informed by implementation science frameworks [50, 51]. The modest sample size and the limited data collected at enrolment prevented exploring the factors which may influence uptake and outcomes in any detail. Future research could consider the inclusion of a control group in the evaluation of such an intervention, incorporate larger samples to ensure there is sufficient power to assess outcomes and conduct multiple repeated assessments, as well as opportunities to validate father-specific measures such as the paternal antenatal and post-natal attachment scales for use in similar settings.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated that a text-based intervention from a high-income setting targeting fathers across the perinatal period can be adapted to be acceptable to fathers from a setting where resources are severely constrained. SMS4baba’s educational and informative messages with specific actions to fathers offer opportunities to enhance fathers’ knowledge, increase male inclusion in childcare and parenting, as well as transform gendered parenting attitudes and practices.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank all study participants for their contribution to this research. We acknowledge the support from Dagoretti sub-county Ministry of Health team during the implementation of this research. We extend gratitude to the teams and individuals involved in various phases of this research design and implementation: the SMS4dads team, University of Newcastle-Australia; the Aga Khan University SMS4KF investigators; and the CDMC investigators in Kenya and Canada including Prof. Kofi Marfo, Prof. Steve Lye, Prof Greg Moran, Dr. Marie-Claude Martin, Dr. Kerrie Proulx, and Dr. Derrick Ssewanyana.

Abbreviations

- CCD

Care for child development

- ECD

Early childhood development

- FGD

Focus group discussion

- GAD-7

Generalized anxiety disorder

- IDI

In-depth interview

- MNCH

Maternal, newborn and child health

- PAAS

Paternal antenatal attachment scale

- PHQ-9

Patient health questionnaire

- SSA

Sub-Saharan Africa

- WHO

World Health Organisation

Author contributions

RF contributed to the design of the intervention. RF and AA contributed to the conception and design of the study. AA contributed to funding acquisition. VA, RF, AA, and MK contributed to the methodology and protocol development. Data collection and curation was supported by VA, MK, RO, SM, JM, EKO, EN, EO, MMM, MW, and AA. VA, PM, RF, and AA were involved in various phases of data analysis. VA wrote the first draft and received contributions from RF, PM, AA, SM, MK, RO, SM, JM, EKO, EN, EO, MMM, MW in subsequent drafts of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Aga Khan University ethics review committee (004-ERC-SSHA-19-EA) and received clearance from the National Commission for Science Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI/P/1950782/31710), and by the Mount Sinai Hospital’s Research Ethics Board (20-0061-E). Additional approvals were obtained from the Nairobi County Directorate of Health, and the sub-county Ministry of Health Dagoretti sub-county. Study participants in the qualitative component of the study provided written informed consent, while telephonic consent was obtained for fathers involved in the intervention phase. All study participants were provided with a detailed description of the study, its benefits, risks, confidentiality, data storage, and management plans. All participants had a chance to ask questions and seek clarifications prior to their involvement. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants and their legal guardians.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Alemann C, Garg A, Vlahovicova K. The role of fathers in Parenting for gender equality. Promundo ed Promundo. 2020:1–14.

- 2.World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on health promotion interventions for maternal and newborn health 2015. [PubMed]

- 3.Ayebare E, Mwebaza E, Mwizerwa J, Namutebi E, Kinengyere AA, Smyth R. Interventions for male involvement in pregnancy and labour: a systematic review. Afr J Midwifery Women’s Health. 2015;9(1):23–8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boltena MT, Kebede AS, El-Khatib Z, Asamoah BO, Boltena AT, Tyae H, et al. Male partners’ participation in birth preparedness and complication readiness in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):1–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yargawa J, Leonardi-Bee J. Male involvement and maternal health outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69(6):604–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barker PM, Reid A, Schall MW. A framework for scaling up health interventions: lessons from large-scale improvement initiatives in Africa. Implement Sci. 2015;11(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Audet CM, Blevins M, Chire YM, Aliyu MH, Vaz LM, Antonio E, et al. Engagement of men in antenatal care services: increased HIV testing and treatment uptake in a community participatory action program in Mozambique. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(9):2090–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Odeny B, McGrath CJ, Langat A, Pintye J, Singa B, Kinuthia J, et al. Male partner antenatal clinic attendance is associated with increased uptake of maternal health services and infant BCG immunization: a national survey in Kenya. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tewabe T. Prelacteal feeding practices among mothers in Motta town, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2018;28(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Jeong J, Sullivan EF, McCann JK, McCoy DC, Yousafzai AK. Implementation characteristics of father-inclusive interventions in low‐and middle‐income countries: A systematic review. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2023;1520(1):34–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin SL, McCann JK, Gascoigne E, Allotey D, Fundira D, Dickin KL. Mixed-methods systematic review of behavioral interventions in low-and middle-income countries to increase family support for maternal, infant, and young child nutrition during the first 1000 days. Curr Developments Nutr. 2020;4(6):nzaa085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin SL, McCann JK, Gascoigne E, Allotey D, Fundira D, Dickin KL. Engaging family members in maternal, infant and young child nutrition activities in low-and middle‐income countries: A systematic scoping review. Matern Child Nutr. 2021;17:e13158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luoto JE, Garcia IL, Aboud FE, Singla DR, Fernald LC, Pitchik HO, et al. Group-based parenting interventions to promote child development in rural Kenya: a multi-arm, cluster-randomised community effectiveness trial. Lancet Global Health. 2021;9(3):e309–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World health Organisation. mHealth: new horizons for health through mobile technologies: second global survey on eHealth 2011 [ https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44607/9789241564250_eng.pdf?sequence=1

- 15.Communications Authority of Kenya. Mobile Subscriptions Hit 66m as at March 2023 2023 [ https://www.ca.go.ke/mobile-subscriptions-hit-66m-march-2023

- 16.Kazi AM, Carmichael J-L, Hapanna GW, Wang’oo PG, Karanja S, Wanyama D, et al. Assessing mobile phone access and perceptions for texting-based mHealth interventions among expectant mothers and child caregivers in remote regions of northern Kenya: a survey-based descriptive study. JMIR public health surveillance. 2017;3(1):e5386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sowon K, Maliwichi P, Chigona W. The influence of design and implementation characteristics on the use of maternal Mobile health interventions in Kenya: Systematic literature review. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2022;10(1):e22093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]