Abstract

Fine particulate matter has been linked with acute coronary syndrome. Nevertheless, the key constituents remain unclear. Here, we conduct a nationwide case-crossover study in China during 2015–2021 to quantify the associations between fine particulate matter constituents (organic matter, black carbon, nitrate, sulfate, and ammonium) and acute coronary syndrome, and to identify the critical contributors. Our findings reveal all five constituents are significantly associated with acute coronary syndrome onset. The magnitude of associations peaks on the concurrent day, attenuates thereafter, and becomes null at lag 2 day. The largest effects are observed for organic matter and black carbon, with each interquartile range increase in their concentrations corresponding to 2.15% and 2.03% increases in acute coronary syndrome onset, respectively. These two components also contribute most to the joint effects, accounting for 31% and 22%, respectively. Our findings highlight tailored clinical management and targeted control of carbonaceous components to protect cardiovascular health.

Subject terms: Cardiology, Environmental impact, Risk factors, Epidemiology

Fine particulate matter has been linked to acute coronary syndrome, but the key constituents remain unclear. Here, the authors show that organic matter and black carbon have the largest effects on acute coronary syndrome onset, and contributed most to the joint impacts.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) has long stood as a predominant cause of morbidity and mortality around the world1,2. According to the World Heart Report 2023, around 20.5 million deaths were attributable to CVD globally in 2021, which was equivalent to around one-third of all deaths3. Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is one of the most fatal CVD subtypes and can significantly impair the life quality of survivors4. Thus, identifying modifiable risk factors of ACS is important for mitigating the disease burden. Epidemiological evidence has shown that ambient air pollution, particularly fine particulate matter (PM2.5), is the leading environmental risk factor for CVD5,6.

PM2.5 is a complex mixture comprising of various organic and inorganic components, mainly including black carbon, organic matter, sulfate, nitrate, and ammonium7. Although relationships between PM2.5 total mass and CVD have been well-documented8–11, the differential effects of its components remain to be fully elucidated. Toxicological research reported variations of physicochemical properties of PM2.5 constituents, which may potentially influence human health in different ways12. Therefore, quantifying and identifying the crucial toxic PM2.5 components can add knowledge to the cardiovascular effects of PM2.5 for better CVD early prevention and management13. Such knowledge can also provide valuable clues and support for future research on source-specific effects of PM2.5.

In the past decades, only a few researches have evaluated the associations of PM2.5 constituents with CVD and yielded mixed results13–16. Heterogeneity might stem from factors including study design, health outcomes, exposure assessment, and statistical methods. Previous time-series studies and aggregate-level case-crossover studies often used daily pollutant concentrations and daily counts of CVD hospitalization or death in specific cities14,15,17, rather than individual-level data, which can lead to apparent ecological fallacy18. Accordingly, utilizing the individual-level time-stratified case-crossover study design could significantly reduce this concern. Additionally, disease onset is more sensitive and immediate than hospital admissions or deaths, which provides earlier opportunities for public health interventions. Owing to data unavailability, most of previous studies were confined to single or a few cities19–21, which compromised the extrapolation of study results to broader populations. Exposure data extracted from fixed-site monitoring stations further contributed to exposure misclassification22,23. Furthermore, most studies investigated the effect of individual constituent one by one without accounting for their multi-collinearity14,20. Weighted quantile sum (WQS) regression is an emerging statistical technique for evaluating the joint effects of correlated co-exposures and identifying the crucial contributors; however, few studies have utilized WQS to explore the relationships between PM2.5 components and ACS onset.

In this work, we conduct a time-stratified case-crossover study using a nationwide registry database of China to comprehensively quantify associations between different PM2.5 constituents and ACS onset, both overall and by subtypes. We also evaluate the joint effects and individual contributions of all components and identify potential effect modifiers. Our findings indicate that all five constituents examined in the present study (i.e., organic matter, black carbon, nitrate, sulfate, and ammonium) are significantly associated with ACS onset, among which organic matter and black carbon contribute most to the joint effects.

Results

Descriptive results

There were 2,539,922 patients diagnosed with ACS between January 1, 2015, and December 31, 2021, in the Chinese Cardiovascular Association (CCA) Database-Chest Pain Center. After excluding patients with no information on symptom onset date and those being transferred from other hospitals, a total of 2,113,728 cases from 2096 hospitals were finally included in the analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1). Among them, 758,464 (35.9%) were diagnosed with ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), 449,161 (21.2%) non-ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), and 906,103 (42.9) unstable angina (UA) (Supplementary Table 1). Half of the patients were older than 65 years and 67.7% were male. The average concentrations of PM2.5 total mass, organic matter, black carbon, nitrate, sulfate, and ammonium at lag 0 day were 38.6, 9.3, 1.8, 8.1, 6.7, and 5.3 μg/m3, respectively (Table 1). Strong and positive correlations were observed between PM2.5 total mass and each of the five main constituents (Spearman correlation coefficient r = 0.88‒0.93) and among different constituents (Spearman r = 0.70‒0.98) (Supplementary Table 2).

Table 1.

Distributions of air pollutants and meteorological factors at lag 0 day during the study period

| Variable | Mean | SD | Minimum | P25 | Median | P75 | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM2.5 (μg/m3) | 38.6 | 25.5 | 7.0 | 20.0 | 32.0 | 50.0 | 135.0 |

| Organic matter (μg/m3) | 9.3 | 6.1 | 1.6 | 4.8 | 7.7 | 11.9 | 33.1 |

| Black carbon (μg/m3) | 1.8 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 2.3 | 6.1 |

| Nitrate (μg/m3) | 8.1 | 7.0 | 0.8 | 2.9 | 5.9 | 11.1 | 34.9 |

| Sulfate (μg/m3) | 6.7 | 4.3 | 1.2 | 3.5 | 5.6 | 8.7 | 23.1 |

| Ammonium (μg/m3) | 5.3 | 4.3 | 0.6 | 2.1 | 4.0 | 7.2 | 21.6 |

| Temperature (°C) | 15.0 | 10.6 | −22.4 | 7.6 | 16.7 | 23.8 | 32.8 |

| Humidity (%) | 63.2 | 19.6 | 3.5 | 48.8 | 66.7 | 79.2 | 99.9 |

SD standard deviation, P25 the 25th percentile, P75 the 75th percentile, PM2.5 fine particulate matter.

Effects of single exposures

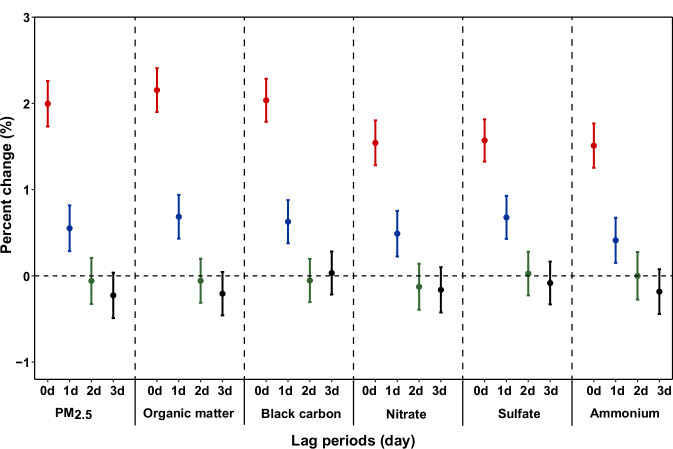

Significant associations were found between PM2.5 total mass as well as constituents and ACS onset (Table 2). The lag patterns were similar, but the magnitudes of effects varied across different constituents (Fig. 1). Generally, the associations occurred immediately on the concurrent day of exposure, attenuated thereafter, and became null at lag 2 day. Thus, we reported results on lag 0 day in the subsequent analyses. Organic matter and black carbon had the strongest associations with ACS onset, followed by sulfate, nitrate, and ammonium. Specifically, an interquartile range (IQR) increase of PM2.5, organic matter, black carbon, nitrate, sulfate, and ammonium concentrations at lag 0 day was associated with 2.00% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.73%‒2.26%), 2.15% (95%CI: 1.90‒2.41%), 2.03% (1.78%‒2.28%), 1.54% (1.28%‒1.80%), 1.57% (1.32%‒1.81%), and 1.51% (1.25%‒1.77%) increase in ACS onset, respectively. The corresponding risk estimates with each 10 μg/m3 increase of total PM2.5 and 1 μg/m3 increase for chemical constituents were presented in Supplementary Table 3.

Table 2.

Percent changes in the risk of onset of ACS and its subtypes per interquartile range increase in concentrations of PM2.5 total mass and its chemical constituents during different lag periods

| Pollutants | Lag | ACS | AMI | STEMI | NSTEMI | UA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM2.5 | 0 d | 2.00 (1.73, 2.26) | 2.40 (2.06, 2.74) | 2.29 (1.85, 2.73) | 2.74 (2.17, 3.31) | 1.36 (0.96, 1.76) |

| 1 d | 0.55 (0.29, 0.82) | 0.76 (0.42, 1.10) | 0.69 (0.25, 1.13) | 0.93 (0.36, 1.51) | 0.23 (−0.17, 0.63) | |

| 2 d | −0.06 (−0.33, 0.21) | 0.20 (−0.15, 0.54) | 0.26 (−0.18, 0.71) | 0.10 (−0.47, 0.68) | −0.15 (−0.56, 0.27) | |

| 3 d | −0.23 (−0.49, 0.04) | 0.00 (−0.34, 0.34) | −0.01 (−0.45, 0.43) | 0.01 (−0.56, 0.58) | −0.01 (−0.43, 0.41) | |

| Organic matter | 0 d | 2.15 (1.90, 2.41) | 2.63 (2.30, 2.97) | 2.42 (1.99, 2.85) | 3.01 (2.45, 3.56) | 1.51 (1.13, 1.90) |

| 1 d | 0.69 (0.43, 0.94) | 0.93 (0.60, 1.27) | 0.84 (0.41, 1.26) | 1.10 (0.55, 1.65) | 0.34 (−0.04, 0.73) | |

| 2 d | −0.06 (−0.31, 0.20) | 0.24 (−0.10, 0.58) | 0.28 (−0.15, 0.71) | 0.16 (−0.38, 0.72) | −0.15 (−0.55, 0.25) | |

| 3 d | −0.21 (−0.46, 0.04) | −0.07 (−0.40, 0.26) | −0.02 (−0.44, 0.40) | −0.17 (−0.71, 0.37) | 0.09 (−0.31, 0.48) | |

| Black carbon | 0 d | 2.03 (1.78, 2.28) | 2.45 (2.12, 2.78) | 2.23 (1.81, 2.65) | 2.88 (2.34, 3.43) | 1.47 (1.09, 1.85) |

| 1 d | 0.63 (0.38, 0.88) | 0.86 (0.53, 1.19) | 0.71 (0.29, 1.13) | 1.11 (0.57, 1.65) | 0.32 (−0.06, 0.71) | |

| 2 d | −0.05 (−0.30, 0.20) | 0.26 (−0.07, 0.60) | 0.35 (−0.07, 0.77) | 0.12 (−0.42, 0.66) | −0.20 (−0.59, 0.20) | |

| 3 d | 0.03 (−0.22, 0.28) | −0.02 (−0.35, 0.30) | −0.02 (−0.43, 0.40) | −0.04 (−0.57, 0.50) | −0.04 (−0.43, 0.35) | |

| Nitrate | 0 d | 1.54 (1.28, 1.80) | 1.95 (1.61, 2.29) | 1.77 (1.34, 2.21) | 2.26 (1.70, 2.83) | 1.00 (0.60, 1.40) |

| 1 d | 0.49 (0.22, 0.75) | 0.63 (0.28, 0.97) | 0.60 (0.16, 1.04) | 0.67 (0.11, 1.24) | 0.29 (−0.12, 0.69) | |

| 2 d | −0.13 (−0.39, 0.14) | 0.16 (−0.19, 0.51) | 0.13 (−0.32, 0.57) | 0.22 (−0.36, 0.79) | −0.34 (−0.77, 0.09) | |

| 3 d | −0.16 (−0.42, 0.10) | 0.16 (−0.19, 0.50) | 0.26 (−0.17, 0.70) | −0.03 (−0.59, 0.54) | −0.15 (−0.58, 0.28) | |

| Sulfate | 0 d | 1.57 (1.32, 1.81) | 1.90 (1.57, 2.22) | 1.71 (1.31, 2.13) | 2.21 (1.68, 2.74) | 1.13 (0.76, 1.51) |

| 1 d | 0.68 (0.43, 0.93) | 0.83 (0.50, 1.16) | 0.66 (0.24, 1.08) | 1.13 (0.59, 1.67) | 0.46 (0.08, 0.84) | |

| 2 d | 0.03 (−0.23, 0.28) | 0.27 (−0.07, 0.60) | 0.29 (−0.14, 0.71) | 0.23 (−0.31, 0.78) | −0.30 (−0.68, 0.09) | |

| 3 d | −0.08 (−0.33, 0.16) | 0.00 (−0.33, 0.33) | −0.05 (−0.46, 0.37) | 0.07 (−0.46, 0.61) | −0.19 (−0.57, 0.19) | |

| Ammonium | 0 d | 1.51 (1.25, 1.77) | 1.85 (1.51, 2.19) | 1.68 (1.25, 2.11) | 2.16 (1.60, 2.71) | 1.05 (0.66, 1.44) |

| 1 d | 0.41 (0.15, 0.67) | 0.55 (0.20, 0.89) | 0.52 (0.08, 0.95) | 0.60 (0.04, 1.17) | 0.21 (−0.19, 0.61) | |

| 2 d | 0.00 (−0.28, 0.28) | 0.11 (−0.23, 0.46) | 0.11 (−0.33, 0.55) | 0.12 (−0.45, 0.69) | −0.38 (−0.77, 0.01) | |

| 3 d | −0.18 (−0.44, 0.08) | 0.05 (−0.29, 0.40) | 0.10 (−0.33, 0.53) | −0.03 (−0.59, 0.53) | −0.04 (−0.47, 0.38) |

ACS acute coronary syndrome, AMI acute myocardial infarction, STEMI ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction, NSTEMI non-ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction, UA unstable angina, PM2.5 fine particulate matter.

Fig. 1. Percent changes in the risk of ACS onset per interquartile range increase in concentrations of PM2.5 total mass and its chemical constituents.

Dots are the estimated percent changes of ACS onset associated with an interquartile range increase in concentrations of PM2.5 total mass and its chemical constituents, and error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. The x-axis labels specify the corresponding lag days (0, 1, 2, and 3 days) for each estimate. A total of 2,113,728 participants were included in the analysis. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Abbreviations: ACS, acute coronary syndrome; PM2.5, fine particulate matter.

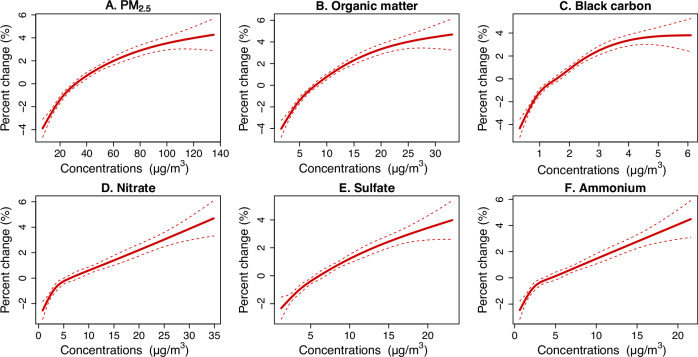

Fig. 2 demonstrates the exposure-response relationships on lag 0 day. All curves increased monotonically with increasing concentrations and were almost linear without any discernible thresholds.

Fig. 2. Exposure-response curves for the associations of PM2.5 total mass and its chemical constituents with ACS onset over lag 0 day.

The solid lines represent the point estimates of percent change in the risk of ACS onset associated with an interquartile range increase in concentrations of PM2.5 total mass (A), organic matter (B), black carbon (C), nitrate (D), sulfate (E), and ammonium (F). The dashed lines indicate the corresponding 95% confidence intervals. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. ACS acute coronary syndrome, PM2.5 fine particulate matter.

The associations varied slightly by different ACS subtypes, with stronger associations found for NSTEMI compared to the other subtypes (Table 2). This pattern was consistent across PM2.5 total mass and its constituents. For example, an IQR increase of organic matter on lag 0 day was associated with 3.01% (95%CI: 2.45%‒3.56%) increase in NSTEMI onset, while smaller effect estimates were observed for acute myocardial infarction (AMI) (2.63%, 95%CI: 2.30%‒2.97%), STEMI (2.42%, 95%CI: 1.99%‒2.85%), and UA (1.51%, 95%CI: 1.13%‒1.90%). Exposure-response relationships of PM2.5 and its constituents with ACS subtypes were similar to those observed for ACS, which were almost linear without discernible thresholds (Supplementary Fig. 2–5).

Stratification analyses indicate that the associations of PM2.5 total mass and constituents with ACS onset were stronger among patients aged over 65 (Table 3 and Supplementary Table 4). The associations were comparable between female and male patients. Stronger associations were found during cold season for all exposures, while significant effect modification of season was found for organic matter (p for interaction = 0.05) and sulfate (p = 0.02). In addition, generally higher effects were found among residents living in the south, with significant effect modifications for PM2.5 (p = 2.39×10-3), organic matter (p = 0.04), black carbon (p = 2.69×10-3), and sulfate (p = 1.23 × 10-5).

Table 3.

Percent changes in the risk of onset of ACS per interquartile range increase in concentrations of PM2.5 total mass and its chemical constituents during lag 0 day, stratified by age, sex, and season

| Subgroups | PM2.5 | Organic matter | Black carbon | Nitrate | Sulfate | Ammonium |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||||

| <65 | 1.83 (1.46, 2.21) | 1.97 (1.61, 2.33) | 1.84 (1.49, 2.20) | 1.41 (1.05, 1.78) | 1.39 (1.04, 1.73) | 1.24 (0.88, 1.60) |

| ≥ 65 | 2.15 (1.78, 2.52) | 2.33 (1.97, 2.69) | 2.22 (1.86, 2.57) | 1.67 (1.30, 2.04) | 1.74 (1.40, 2.09) | 1.78 (1.41, 2.14) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 2.00 (1.69, 2.32) | 2.23 (1.92, 2.54) | 2.11 (1.80, 2.41) | 1.50 (1.19, 1.81) | 1.63 (1.33, 1.93) | 1.48 (1.17, 1.79) |

| Female | 1.90 (1.43, 2.37) | 1.98 (1.53, 2.43) | 1.87 (1.43, 2.32) | 1.63 (1.16, 2.09) | 1.44 (1.01, 1.87) | 1.57 (1.11, 2.03) |

| Season | ||||||

| Warm | 1.40 (1.03, 1.78) | 1.78 (1.43, 2.14) | 1.71 (1.36, 2.05) | 1.03 (0.68, 1.39) | 0.94 (0.58, 1.29) | 1.02 (0.66, 1.38) |

| Cold | 2.52 (2.13, 2.92) | 2.60 (2.21, 2.98) | 2.39 (2.02, 2.77) | 2.02 (1.62, 2.42) | 2.06 (1.71, 2.42) | 1.94 (1.56, 2.33) |

| Region | ||||||

| South | 2.14 (1.75, 2.53) | 2.21 (1.82, 2.60) | 2.32 (1.93, 2.71) | 1.57 (1.18, 1.96) | 2.12 (1.73, 2.51) | 1.61 (1.21, 2.01) |

| North | 1.88 (1.53, 2.22) | 2.14 (1.79, 2.48) | 1.87 (1.54, 2.21) | 1.53 (1.19, 1.88) | 1.31 (0.99, 1.64) | 1.49 (1.15, 1.83) |

ACS acute coronary syndrome, PM2.5 fine particulate matter.

As shown in the Supplementary Table 5, reducing total PM2.5 concentrations by an IQR could have prevented 1.96% of ACS cases, equivalent to 41,348 cases in the present database. If reducing different constituents of PM2.5 by an IQR, the preventable fractions of ACS cases range from 1.49% for ammonium to 2.11% for organic matter, corresponding to a reduction of 31,436 to 44,566 cases.

Effects of joint exposures

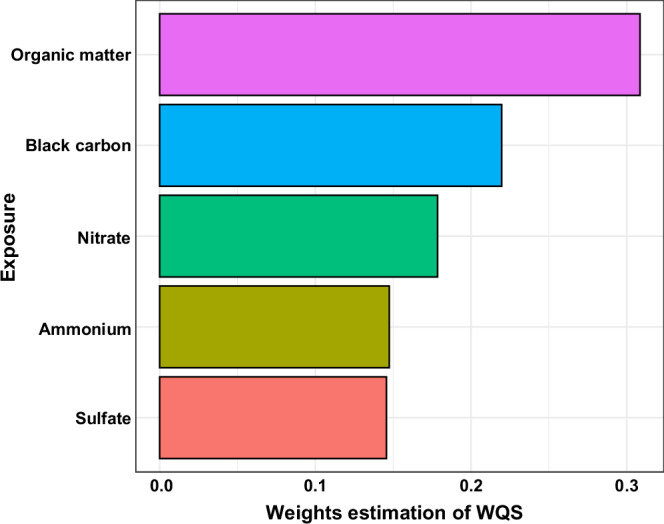

In the analysis of joint exposure to five constituents of PM2.5, ACS onset increased by 1.09% (95%CI: 0.86%–1.32%) per quartile increase of the WQS mixture index. As shown in Fig. 3, among the five constituents, organic matter had the highest weight (i.e., 0.31), followed by black carbon (i.e., 0.22), while the rest three ions were all below 0.20.

Fig. 3. The importance of PM2.5 chemical constituents in the associations with ACS onset.

Each bar represents a specific component, with the bar length indicating its relative weight derived from the WQS regression. The weight values are shown along the x-axis, while the components are listed on the y-axis. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. PM2.5 fine particulate matter, ACS acute coronary syndrome, WQS weighted quantile sum.

Results of sensitivity and supplementary analyses

Sensitivity analyses of controlling for PM2.5 total mass in the main models show that the associations for organic matter, black carbon, and ammonium remained stable, while those of nitrate and sulfate became null (Supplementary Table 6). When restricting the analysis to participants with complete onset addresses, the results were little affected by using air pollutant concentrations matched by the addresses of the event onset versus hospitals (Supplementary Table 7). When further matching control days based on the temperature of the case days, we observed slightly weaker but significant effects, and the overall pattern for the differential effects of constituents remained consistent (Supplementary Table 8). Quantile-based g computation (QGC) analysis shows that a quartile increase in mixture of the five constituents was significantly associated with an increase of 0.92% (95%CI: 0.75%–1.09%) in the risk of ACS onset. Organic matter and black carbon had higher weights, which was consistent with our initial findings (Supplementary Fig. 6). Results of the supplementary analysis are presented in Supplementary Table 9 and Supplementary Fig. 7. The effects of the remaining components were weaker than organic matter and black carbon, and comparable to nitrate, sulfate, and ammonium. Including the remaining components in WQS regression also yielded similar results, with a quartile increase in the WQS index associated with a 1.01% (95%CI: 0.76%–1.25%) increase in ACS onset.

Discussion

This individual-level time-stratified case-crossover study comprehensively differentiated the associations of PM2.5 constituents with increased risk of ACS onset. Similar patterns were observed in lagged effects and exposure-response curves for all five constituents, while the estimated effects varied. Organic matter and black carbon might contribute the most to the observed relationship. The adverse effects were more evident for patients above age 65, residents in the south, and during the cold season. This study provides valuable evidence for informed and targeted public health strategies on air pollution control in the future.

Prior evidence mainly stems from studies exploring the relationships of PM2.5 constituents with CVD hospitalization or mortality, with inconclusive findings. A time-series study conducted in the Denver metropolitan area of the U.S. only observed significant effects of elemental carbon and organic carbon on CVD hospitalization15. A case-crossover study in southern China also revealed significant associations between carbonaceous components and myocardial infarction deaths, with null associations identified for other components24. In contrast, another two multi-city studies in the U.S. and China reported significant results for both carbonaceous and ionic constituents (e.g., sulfate, nitrate, and ammonium) with CVD hospitalization16,17. Besides, a time-series study in China showed exposure to organic carbon, sulfate, and ammonium was significantly associated with increased ischemic heart disease mortality, while non-significant associations were found for elemental carbon and nitrate25. Most studies reported the strongest associations on the concurrent day or 1 day after exposure15,17,23–25. However, some studies found varying lag patterns for different constituents16,26. Inconsistency in these previous findings might be explained by differences in study design, geographical coverage, sample size, exposure assessment, and health outcomes. Based on a national database covering 2.11 million patients in China, this case-crossover study provides first-hand and compelling evidence that five main constituents (i.e., organic matter, black carbon, nitrate, sulfate, and ammonium) of PM2.5 could significantly trigger the onset of ACS and its subtypes, with the most pronounced effects observed on the concurrent day.

Existing studies typically explored the key components by comparing the effects of specific constituents derived from single-pollutant models14,16,20, which did not account for potential collinearity across these simultaneous exposures. In this study, we used WQS regression to address this concern13,27. Results suggest that organic matter and black carbon are the main contributors to the PM2.5-related ACS onset. The two components predominantly originate from the combustion process and traffic emissions21, and have been suggested to interact with multiple pathological pathways associated with CVD, including systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system, and atherosclerosis development28–31. Our findings were consistent with prior studies, which also observed higher cardiovascular impacts of carbonaceous components than secondary constituents such as sulfate and nitrates15,21,24. Analyses based on QGC revealed similar results with WQS, except that the estimated weight for nitrate became negative. Setting a negative effect direction ensured convergence of QGC32. The negative weight for nitrate does not necessarily indicate a significant negative association. This may be explained by high correlations among these constituents, which can lead to some constituents being non-significant in QGC and ultimately result in the overall negative effect being close to zero and negative weights being substantive33. Similar patterns have also been observed in other studies33–35. Although carbonaceous components showed relatively stronger effects, other components (e.g., sulfate, nitrate, and ammonium) should not be overlooked. Specifically, we observed that sulfate, which is mainly in the form of ammonium sulfate, exhibited a stronger health effect per unit increase in concentration compared to that of total PM2.5 mass in the single-pollutant models. Besides, it should also be noted that these five constituents do not account for all of PM2.5 total mass, and the weights derived from WQS and QGC only represent each component’s contribution to the health effects of the mixture of the five measured constituents. The supplementary analysis based on the remaining components also reveals that there may be important unmeasured constituents in PM2.5 that warrant further investigation.

In our analysis, most PM2.5 components exhibited linear exposure-response relationships with ACS onset. However, the exposure-response curves of some components, such as black carbon, flattened slightly at higher concentrations, indicating a lower health impact per unit increase of the components on highly polluted days. One possible explanation for this flattening is the limited number of data points at higher concentrations, which may lead to less stable estimates. Another possible explanation is that the sources of these components may vary with concentration levels. For instance, a time-series study conducted in Dhaka, Bangladesh, observed a similar plateau in the exposure-response curve at higher PM2.5 levels36. Their findings suggest that at lower concentrations, PM2.5 is primarily from fossil fuel combustion, while at higher concentrations, biomass burning, which has lower cardiovascular toxicity, may become more dominant. However, due to the lack of nationwide PM2.5 source data with high spatiotemporal resolution in China, future research on source-specific effects is warranted to fully elucidate this issue.

In the models adjusted for total PM2.5 mass, we observed robust effect estimates for organic matter, black carbon, and ammonium, but not for nitrate and sulfate. However, this finding does not necessarily imply that the effects of nitrate and sulfate are completely dependent on the total PM2.5 mass due to the following reasons. First, constituent-PM2.5 models may mask the effects of specific components due to overadjustment related to the high collinearity with PM2.5, leading to an underestimation of associations37. Second, the impacts of exposure measurement errors usually become more complicated in multi-pollutant models, adding to the statistical uncertainty of results. Furthermore, ammonium is often correlated with nitrate and sulfate17, which complicates the interpretation of the results, as the observed health effects may be attributed to nitrate and sulfate rather than ammonium itself. Therefore, results on ammonium should be interpreted with caution and warrant future elucidation.

Our results show that stronger associations were observed for NSTEMI, followed by STEMI, and UA, which was consistent across different PM2.5 constituents. Evidence on the associations between specific constituents of PM2.5 and ACS subtypes is limited, making direct comparisons with previous studies difficult. However, previous findings on the associations between total PM2.5 mass or other air pollutants and AMI provide some support for our results. For example, a few studies reported stronger associations of air pollution with NSTEMI than STEMI38–40. Nevertheless, another study in the U.S. found statistically significant associations between PM2.5 and STEMI, rather than NSTEMI41. Mechanistically, STEMI mainly results from coronary artery occlusion following plaque rupture, and can lead to complete blood flow cessation and ischemic necrosis of the myocardial region. In contrast, NSTEMI usually involves plaque erosion and less severe coronary artery obstruction41,42. The observed stronger association with NSTEMI than STEMI suggests that acute exposure to PM2.5 and its constituents is more likely to trigger plaque erosion and less severe obstructions, compared to complete coronary artery occlusion40. UA usually results from various causes, including coronary artery spasm, transient increases in myocardial oxygen demand, and partial blockages of coronary artery43. The diverse causes may make UA influenced by multiple factors beyond acute PM2.5 exposure, which helps explain its weaker association with PM2.5 and constituents. Nevertheless, given the mixed findings and scarce existing evidence, further research is urgently warranted to corroborate our results and fully elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

Stratification analyses show the associations were stronger among the elderly patients, which was echoed by previous studies14,16,44. Elderly individuals are more susceptible to air pollution exposure due to the degradation of their cardiovascular function and immune system. Additionally, the increased likelihood of having comorbidities, such as hypertension and hyperlipidemia, may further elevate CVD risk among them. Higher ACS risks associated with PM2.5 and its constituents were observed during cold season, which was expected as biomass and fossil fuel combustion, major sources of PM2.5 pollution, usually increase during winter24. In addition, low temperature during the cold season may increase the burden on the cardiovascular system, which can also lead to higher vulnerability to cardiovascular events. Residents living in the south had higher risk of ACS. This finding was supported by another study reporting higher CVD incidence associated with PM2.5 constituents among southern Chinese people44. The regional heterogeneity could be attributed to various factors, including emission source apportionment, exposure concentrations, climate, and population characteristics25,45.

Our results have important implications for patients, clinicians, and policymakers. Individuals at risk of CVD should be educated about the detrimental effects of short-term exposure to PM2.5 and its constituents. They should adopt necessary lifestyle adjustments such as reducing outdoor activity and using indoor air purifiers during episodes of air pollution, and promptly seek medical assistance if needed46. Clinicians need to place greater emphasis on air pollution exposure when interacting with patients, and make sufficient medical preparations during heavily-polluted days. Integration of environmental factors into clinical practice can enhance precision in prevention and treatment of CVD, and facilitate personalized care. For policymakers, it is critical to consider implementing stringent strategies to reduce PM2.5 pollution, with specific attention to carbonaceous components which are primarily originated from biomass and fossil fuel combustion process. Additionally, targeted protective measures should be taken for vulnerable populations.

There were several strengths of this study. First, this nationwide health database with more than 2 million ACS patients from all major cities and hospitals across China is a representative sample of ACS patients in China, and ensures high data quality and adequate statistical power for this analysis. Second, our constituent data were from a high spatial and temporal resolution model, which can substantially reduce exposure misclassification compared to exposure data from fixed-site monitoring stations. Last, this study used WQS regression to address collinearity of multiple PM2.5 constituents and to estimate the joint effects of PM2.5 constituents as well as their relative contributions.

Several limitations should also be acknowledged. First, exposure misclassifications are possible. Even though we used high-resolution exposure assessment model to measure PM2.5 and its constituents among our study population, exposure in indoor environment was not captured. Second, in the main analysis, we matched exposure data for each patient based on hospital addresses rather than the specific addresses of symptom onset, as more than 50% of patients did not provide complete onset addresses. However, this would not be a major concern because: 1) ACS patients in China are always sent to the nearest hospital for timely care, and we had further excluded those transferred from other hospitals; 2) the median distance between hospitals and the onset address was 6.2 kilometers among participants who provided complete onset addresses; and this distance is generally acceptable in epidemiological studies on short-term exposures, in which the temporal variations of exposures are more important than spatial variations; and 3) our sensitivity analysis based on addresses of disease onset yielded comparable results to those estimated using hospital addresses. Third, given the high correlation between different constituents, our results only reflect statistical associations rather than causal relationships, and the strength of their health effects was evaluated primarily based on statistical findings. Therefore, the findings should be interpreted with caution, and future researches, such as toxicological studies and randomized controlled trials, are warranted to validate the true effects of the components and better understand their individual contributions. Fourth, WQS assumes linearity for these relationships. Although most components exhibited a linear relationship with ACS onset, some of the exposure-response curves flattened slightly at higher concentrations, which could affect the stability of our estimates. Fifth, both WQS and QGC provide fixed index weights without confidence intervals, which is a shortcoming in this field as it prevents estimating the statistical significance of the weights. Sixth, due to data unavailability, we failed to consider the health impacts of metallic elements as well as the PM2.5 sources that were shown previously47. Last, residual confounding from time-varying lifestyle factors, which could not be collected from patient’s medical records, might still introduce bias to our results. Nevertheless, we believe that this would not significantly influence our results as these factors are unlikely to undergo substantial changes within one month in such a large population.

In summary, this nationwide case-crossover study, based on 2.11 million ACS patients from 2096 hospitals in China, provides compelling evidence on differential effects of various PM2.5 constituents on the onset of ACS and its subtypes. Our findings underscore the critical roles played by carbonaceous components (i.e., organic matter and black carbon) in the observed relationships. This information holds significant implications for clinical management, public health interventions, and environment policies in the future.

Methods

The Institutional Review Board at the School of Public Health, Fudan University approved the study protocol (IRB#2021-04-0889), and waived the requirement for informed consent because the study involved analysis of deidentified data. None of the authors were involved in the collection of data from the participants. Our study adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Study design

The time-stratified case-crossover study design was used to investigate the associations between daily PM2.5 constituents and ACS onset. This design has been widely used to quantify the associations between short-term exposure to environmental risk factors and acute health events9,48. The case day was defined as the day of ACS onset and were matched with 3 or 4 control days, which were selected from the days that were in the same year, month, and day of the week with the case day to control for time trends and seasonality. Because each patient serves as his or her own control, variables that are time-invariant or can remain stable within one month (e.g., age, sex, socioeconomic status) are not considered as confounders. Specifically, if an ACS event occurred on Wednesday, September 12, 2018, we defined September 12, 2018 as the case day, and all other Wednesdays in September 2018 (i.e., September 5, 19, and 26) were defined as the control days.

Health data

ACS cases were extracted from the CCA Database-Chest Pain Center. The database was a national registry established in China since 2015 covering all patients visiting chest pain centers in Chinese mainland. Information on demographic characteristics such as age and sex, date of ACS onset, clinical diagnosis, test results, and treatments of each patient was recorded. The Expert Committee and the Executive Committee of the China Chest Pain Center implemented a standardized registry system to ensure stringent data quality control. Details on CCA database have been published previously40,49,50.

In the present analysis, we included patients diagnosed with STEMI, NSTEMI, and UA in the CCA Database-Chest Pain Center between January 1, 2015 and December 31, 2021, and identified them as ACS patients. The distribution of the hospitals where the patients were treated was provided in a previous publication51. STEMI and NSTEMI patients were further combined into AMI. All diagnoses were made by cardiologists or clinicians based on symptoms, electrocardiographic results, and biochemical examinations, following the Chinese Society of Cardiology guidelines52,53. Patients with no information on symptom onset date and those being transferred from other hospitals were excluded to ensure proper matching with environmental exposure data.

Environmental exposure assessment

Daily concentrations of PM2.5 and its constituents, including organic matter, black carbon, nitrate, sulfate, and ammonium during the study period were extracted from Tracking Air Pollution in China (TAP) dataset (http://tapdata.org.cn)54,55. Details could be found in Supplementary Methods. In brief, by combining the Weather Research and Forecasting–Community Multiscale Air Quality modeling system, ground observations, a machine learning algorithm, and multisource-fusion PM2.5 data, TAP dataset provides a full-coverage daily PM2.5 and its constituents in China at a 10×10 km resolution. Concentrations of PM2.5 constituents predicted from the TAP dataset have been shown to demonstrate high correlations with actual observations (correlation coefficients ranging from 0.67 to 0.80)54. To avoid the potential influence of extreme values in air pollutants concentrations, the highest and lowest 2.5% of daily concentrations during the study period were trimmed before formal analyses49,56. Daily temperature and relative humidity data over the same period were extracted from the fifth-generation European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts atmospheric reanalysis (ERA5) of the global climate57. To measure each patient’s environmental exposure, we matched the geocoded hospital address where the patient was admitted with the nearest grid cells in the TAP and ERA5 dataset, and used estimates in these grids during the corresponding periods to represent exposures. For each case or control day, exposure to PM2.5, PM2.5 constituents, temperature, and relative humidity were measured for up to 3 days prior.

Statistical analyses

Effects of individual constituents

Conditional logistic regression models were applied to investigate the associations of daily exposure to PM2.5 and its constituents with the onset of ACS and its subtypes, including AMI, STEMI, NSTEMI, and UA. Consistent with previous studies on air pollution and cardiovascular health8,9,49, we first fitted regression models using a linear term for PM2.5 total mass and its constituents, respectively, assuming linear exposure-response relationships. Different lag periods of exposure (i.e., lags of 0, 1, 2, 3 day) before the case and control day were applied. Then we replaced the linear term with a natural cubic spline with 4 degrees of freedom to explore possible non-linear exposure‒response relationships. To control for potential confounding from time-varying factors, we included a binary variable for public holidays and natural cubic spline functions with 6 and 3 degrees of freedom for 3-day average temperature and humidity, respectively, in the covariates8,49.

To identify potential effect modifiers, subgroup analyses stratified by age (<65 vs. ≥ 65 years), sex (male vs. female), season (warm: April–September, vs. cold: October–March), and geographic region (south vs. north) were performed. Potential effect modifications were examined by including interaction terms between the grouping factor (i.e., age, sex, season, and region) and PM2.5 constituents in the models.

To convey the public health significance more clearly, we further calculated the fraction () and number () of ACS cases that could be prevented in the present database if the level of each constituent is reduced by an IQR using the following equations:

| 1 |

| 2 |

where is the regression coefficient of the ith constituent from the conditional logistic regression; is the interquartile range of the ith constituent concentrations; and is the total ACS cases recorded in the present database.

Effects of joint exposure to different constituents

Joint effects of simultaneous exposure to all constituents were estimated using WQS regression. This is a multi-step modeling approach that can address collinearity across multiple correlated exposures58, and has been widely used in environmental health studies to explore the health effects of air pollutants mixtures, including PM2.5 chemical constituents13,27,59–61. The main principle is to combine multiple correlated predictors into a single index that represents the overall mixture. The original data is randomly split into a training dataset and a validation dataset. Each of the constituent is converted into a categorical variable representing the quantiles (quartiles in our case). The model first estimates the empirical weight index of each exposure among bootstrapping samples from the training dataset based on the association between quantiles (quartiles in our case) of each exposure component and the health outcome. The weights are scaled to sum to one. The final weights are defined as average weights across the bootstrap samples. Then a weighted index is constructed by using these final weights and subsequently incorporated into the regression model using the validation dataset to estimate the joint effects of components mixture on the health outcome. In the present analysis, the data were divided into 40% of the dataset for training and 60% for validation, and the bootstrap was set as 100 times. The direction of association was assumed positive for all the constituents according to existing evidence13,16. Since WQS regression cannot address the correlation within the clusters (i.e., the self-controlled pairs), we adjusted for age and sex in addition to all covariates included in the conditional logistic models when estimating the weights62. Results of the WQS regression include estimated weights for each constituent, which can be interpreted as the relative contributions of these constituents to the overall effect, and estimates for the joint effects of five PM2.5 constituents on ACS onset. The threshold for the key components was defined as weight > (1/number of species). More details on WQS regression were provided in Supplementary Methods.

Sensitivity and supplementary analyses

We conducted several sensitivity analyses. First, to control for the potential confounding from PM2.5 total mass on constituents, we built “constituent-PM2.5 models” as a sensitivity analysis by adding the present-day PM2.5 total mass to the constituent models63. Second, we restricted the analysis to participants who provided complete addresses of their location at the time of ACS onset, and reran the main model using air pollution data matched according to the address of disease onset and reporting hospital, respectively. Third, we re-performed the main analysis by selecting control days by matching temperatures64,65: (1) control days were chosen from the same year and month as the case days; (2) control days and case days had to be at least 3 days apart from each other to avoid short-term autocorrelation; (3) the difference in daily average temperature between control days and case days was less than 2 °C. Fourth, we explored the joint effects of five constituents by using QGC. This method maintains the simple inferential framework of WQS without assuming directional homogeneity32, and the weights may go in either direction. The sum of positive and negative weights is both equal to 1. The weights are only compatible with other weights in the same (i.e., positive or negative) direction, whereas positive and negative weights should not be compared with each other.

To explore the potential effects of the remaining unmeasured components, we conducted a supplementary analysis. Specifically, we subtracted the concentrations of the five measured constituents from the total PM2.5 mass to obtain the remaining unmeasured components, and reran the main models based on these remaining components.

All statistical analyses were performed using R software (Version 4.0.0, R Project for Statistical Computing) and “survival”, “splines”, “gWQS”, and “qgcomp” packages. All tests were two-sided with an α of 0.05. Percent changes and 95%CIs in the disease onset associated with each IQR increase in exposure were calculated by the following formulas:

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

where is the regression coefficient, and is the corresponding standard error. To better facilitate comparisons of the results with other literature, the risk of ACS onset associated with each 10 μg/m3 increase in total PM2.5 and 1 μg/m3 increase in chemical constituents was also reported.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Source data

Acknowledgements

We thank all professionals in the Expert Committee and the Executive Committee of the China Chest Pain Center (https://www.chinacpc.org/home/auth/orgdesc) for their valuable contributions to the present study. This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFC3702701, R.C.), the Shanghai 3-year Public Health Action Plan (GWVI-11.1−39, H.K.), the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF (GZB20230148, Y.J.), the Shanghai Committee of Science and Technology (21TQ015, R.C.), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (92043301, H.K.).

Author contributions

Y.J., C.D., and R.C. contributed equally and are joint first authors. J.G., Y.H., and H.K. contributed equally to the correspondence work. J.G., Y.H. and H.K. contributed to the conceptualization of the study, methodology, validation, review, editing, and supervision of the manuscript. Y.J., C.D., and R.C. contributed to the data curation, formal analysis, methodology, visualization, drafting of the original manuscript, and review and editing of the manuscript. J.H., X.Z., X.X., Q.H. and J.L. contributed to data curation, and review and editing of the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final manuscript. The corresponding authors attest that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jean-François Argacha, and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings described in this manuscript are available in the article and in the Supplementary Information. The disease onset data was obtained from the Chinese Cardiovascular Association (CCA) Database-Chest Pain Center. Due to data management requirements and patients’ privacy considerations, access to the disease onset data can be obtained by contacting the corresponding authors, Junbo Ge (ge.junbo@zs-hospital.sh.cn), Yong Huo (huoyong@263.net.cn), and Haidong Kan (kanh@fudan.edu.cn), and requests will be addressed within 12 weeks. The air pollution data were obtained from Tracking Air Pollution in China (TAP) dataset, accessible at http://tapdata.org.cn. Meteorological data were sourced from the fifth generation atmospheric reanalysis product (ERA5), accessible at https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/search?type=dataset. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

R codes for statistical analysis are available upon request from the corresponding authors, Junbo Ge (ge.junbo@zs-hospital.sh.cn), Yong Huo (huoyong@263.net.cn), and Haidong Kan (kanh@fudan.edu.cn). We will respond to the requests within 2 weeks.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Yixuan Jiang, Chuyuan Du, Renjie Chen.

Contributor Information

Junbo Ge, Email: ge.junbo@zs-hospital.sh.cn.

Yong Huo, Email: huoyong@263.net.cn.

Haidong Kan, Email: kanh@fudan.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-024-55080-6.

References

- 1.Vos, T. et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet396, 1204–1222 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Long, Z. et al. Mortality trend of heart diseases in China, 2013–2020. Cardiology7, 111–117 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Heart Federation. World Heart Report 2023: Confronting the World’s Number One Killer. (Geneva, Switzerland, 2023).

- 4.Bergmark, B. A., Mathenge, N., Merlini, P. A., Lawrence-Wright, M. B. & Giugliano, R. P. Acute coronary syndromes. Lancet399, 1347–1358 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray, C. J. L. et al. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet396, 1223–1249 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mustafić, H. et al. Main Air Pollutants and Myocardial Infarction: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA307, 713–721 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Donkelaar, A., Martin, R. V., Li, C. & Burnett, R. T. Regional Estimates of Chemical Composition of Fine Particulate Matter Using a Combined Geoscience-Statistical Method with Information from Satellites, Models, and Monitors. Environ. Sci. Technol.53, 2595–2611 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, R. et al. Hourly Air Pollutants and Acute Coronary Syndrome Onset in 1.29 Million Patients. Circulation145, 1749–1760 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu, Y. et al. Short-Term Exposure to Ambient Air Pollution and Mortality From Myocardial Infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.77, 271–281 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kan, H., Li, T. & Zhang, Z. Air pollution and cardiovascular heath in a changing climate. Cardiology8, 69–71 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ban, J. et al. Ambient PM2.5 and acute incidence of myocardial infarction in China: a case-crossover study and health impact assessment. Cardiology8, 111–117 (2023).36515976 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu, F. et al. Investigation of the chemical components of ambient fine particulate matter (PM(2.5)) associated with in vitro cellular responses to oxidative stress and inflammation. Environ. Int136, 105475 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li, J. et al. Ambient PM2.5 and its components associated with 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in Chinese adults. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.263, 115371 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu, Y. et al. Assessing the association between fine particulate matter (PM(2.5)) constituents and cardiovascular diseases in a mega-city of Pakistan. Environ. Pollut.252, 1412–1422 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim, S. Y. et al. The temporal lag structure of short-term associations of fine particulate matter chemical constituents and cardiovascular and respiratory hospitalizations. Environ. Health Perspect.120, 1094–1099 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang, Y. et al. Assessing short-term impacts of PM(2.5) constituents on cardiorespiratory hospitalizations: Multi-city evidence from China. Int J. Hyg. Environ. Health240, 113912 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peng, R. D. et al. Emergency admissions for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases and the chemical composition of fine particle air pollution. Environ. Health Perspect.117, 957–963 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duque, J. C., Artís, M. & Ramos, R. The ecological fallacy in a time series context: evidence from Spanish regional unemployment rates. J. Geogr. Sci.8, 391–410 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ito, K. et al. Fine particulate matter constituents associated with cardiovascular hospitalizations and mortality in New York City. Environ. Health Perspect.119, 467–473 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang, Y. et al. Differential associations of particle size ranges and constituents with stroke emergency-room visits in Shanghai, China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.232, 113237 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang, W. et al. Particulate air pollution and ischemic stroke hospitalization: How the associations vary by constituents in Shanghai, China. Sci. Total Environ.695, 133780 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen, S. Y., Lin, Y. L., Chang, W. T., Lee, C. T. & Chan, C. C. Increasing emergency room visits for stroke by elevated levels of fine particulate constituents. Sci. Total Environ.473-474, 446–450 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cao, J., Xu, H., Xu, Q., Chen, B. & Kan, H. Fine particulate matter constituents and cardiopulmonary mortality in a heavily polluted Chinese city. Environ. Health Perspect.120, 373–378 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mo, S. et al. Short-term effects of fine particulate matter constituents on myocardial infarction death. J. Environ. Sci. (China)133, 60–69 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang, J. et al. Fine particulate matter constituents and cause-specific mortality in China: A nationwide modelling study. Environ. Int143, 105927 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nayebare, S. R. et al. Association of fine particulate air pollution with cardiopulmonary morbidity in Western Coast of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J.38, 905–912 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu, S. et al. Metal mixture exposure and the risk for immunoglobulin A nephropathy: Evidence from weighted quantile sum regression. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res Int30, 87783–87792 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu, J. et al. Fine particulate matter constituents and heart rate variability: A panel study in Shanghai, China. Sci. Total Environ.747, 141199 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siponen, T. et al. Source-specific fine particulate air pollution and systemic inflammation in ischaemic heart disease patients. Occup. Environ. Med72, 277–283 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu, S. et al. Chemical constituents of ambient particulate air pollution and biomarkers of inflammation, coagulation and homocysteine in healthy adults: a prospective panel study. Part Fibre Toxicol.9, 49 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grady, S. T. et al. Indoor black carbon of outdoor origin and oxidative stress biomarkers in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Environ. Int115, 188–195 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keil, A. P. et al. A Quantile-Based g-Computation Approach to Addressing the Effects of Exposure Mixtures. Environ. Health Perspect.128, 47004 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou, H. et al. Associations of Long-Term Exposure to Fine Particulate Constituents With Cardiovascular Diseases and Underlying Metabolic Mediations: A Prospective Population-Based Cohort in Southwest China. J. Am. Heart Assoc.13, e033455 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao, N., Smargiassi, A., Chen, H., Widdifield, J. & Bernatsky, S. Systemic autoimmune rheumatic diseases and multiple industrial air pollutant emissions: A large general population Canadian cohort analysis. Environ. Int174, 107920 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhao, N. et al. Fine particulate matter components and interstitial lung disease in rheumatoid arthritis. Eur. Respir. J.60(2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Rahman, M. M. et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associations with biomass- and fossil-fuel-combustion fine-particulate-matter exposures in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Int J. Epidemiol.50, 1172–1183 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cai, J. et al. Prenatal Exposure to Specific PM(2.5) Chemical Constituents and Preterm Birth in China: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Environ. Sci. Technol.54, 14494–14501 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ho, A. F. W. et al. Time-Stratified Case Crossover Study of the Association of Outdoor Ambient Air Pollution With the Risk of Acute Myocardial Infarction in the Context of Seasonal Exposure to the Southeast Asian Haze Problem. J. Am. Heart Assoc.8, e011272 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Milojevic, A. et al. Short-term effects of air pollution on a range of cardiovascular events in England and Wales: case-crossover analysis of the MINAP database, hospital admissions and mortality. Heart100, 1093–1098 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiang, Y. et al. Hourly Ultrafine Particle Exposure and Acute Myocardial Infarction Onset: An Individual-Level Case-Crossover Study in Shanghai, China, 2015-2020. Environ. Sci. Technol.57, 1701–1711 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gardner, B. et al. Ambient fine particulate air pollution triggers ST-elevation myocardial infarction, but not non-ST elevation myocardial infarction: a case-crossover study. Part Fibre Toxicol.11, 1(2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Libby, P., Pasterkamp, G., Crea, F. & Jang, I. K. Reassessing the Mechanisms of Acute Coronary Syndromes. Circ. Res124, 150–160 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fuster, V. & Chesebro, J. H. Mechanisms of unstable angina. N. Engl. J. Med315, 1023–1025 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu, L., Zhang, Y., Yang, Z., Luo, S. & Zhang, Y. Long-term exposure to fine particulate constituents and cardiovascular diseases in Chinese adults. J. Hazard Mater.416, 126051 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang, Y., Cai, J., Wang, S., He, K. & Zheng, M. Review of receptor-based source apportionment research of fine particulate matter and its challenges in China. Sci. Total Environ.586, 917–929 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang, Y. et al. Risk of Cardiovascular Hospital Admission After Exposure to Fine Particulate Pollution. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.78, 1015–1024 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weichenthal, S. et al. Association of Sulfur, Transition Metals, and the Oxidative Potential of Outdoor PM2.5 with Acute Cardiovascular Events: A Case-Crossover Study of Canadian Adults. Environ. Health Perspect.129, 107005 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Di, Q. et al. Association of Short-term Exposure to Air Pollution With Mortality in Older Adults. JAMA318, 2446–2456 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xue, X. et al. Hourly air pollution exposure and the onset of symptomatic arrhythmia: an individual-level case-crossover study in 322 Chinese cities. Cmaj195, E601–e611 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xiang, D. et al. Management and Outcomes of Patients With STEMI During the COVID-19 Pandemic in China. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.76, 1318–1324 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhu, X. et al. Stock volatility may trigger the onset of acute coronary syndrome: A nationwide case-crossover analysis. Innov. Med.1, 100038 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chinese Society of Cardiology of Chinese Medical Association and Editorial Board of Chinese Journal of Cardiology. [2019 Chinese Society of Cardiology (CSC) guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction]. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi47, 766-783 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Chinese Society of Cardiology of Chinese Medical Association and Editorial Board of Chinese Journal of Cardiology. [Guideline and consensus for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome (2016)]. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi45, 359-376 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Liu, S. et al. Tracking Daily Concentrations of PM(2.5) Chemical Composition in China since 2000. Environ. Sci. Technol.56, 16517–16527 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Geng, G. et al. Tracking Air Pollution in China: Near Real-Time PM(2.5) Retrievals from Multisource Data Fusion. Environ. Sci. Technol.55, 12106–12115 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hu, J. et al. The acute effects of particulate matter air pollution on ambulatory blood pressure: A multicenter analysis at the hourly level. Environ. Int157, 106859 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q J. R. Meteorol. Soc.146, 1999–2049 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carrico, C., Gennings, C., Wheeler, D. C. & Factor-Litvak, P. Characterization of Weighted Quantile Sum Regression for Highly Correlated Data in a Risk Analysis Setting. J. Agric Biol. Environ. Stat.20, 100–120 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhuo, H. et al. A nested case-control study of serum polychlorinated biphenyls and papillary thyroid cancer risk among U.S. military service members. Environ. Res212, 113367 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang, Q. et al. Association between manganese exposure in heavy metals mixtures and the prevalence of sarcopenia in US adults from NHANES 2011-2018. J. Hazard Mater.464, 133005 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li, S. et al. Long-term Exposure to Ambient PM2.5 and Its Components Associated With Diabetes: Evidence From a Large Population-Based Cohort From China. Diabetes Care46, 111–119 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rahbar, M. H. et al. Interaction between manganese and GSTP1 in relation to autism spectrum disorder while controlling for exposure to mixture of lead, mercury, arsenic, and cadmium. Res Autism Spectr. Disord.55, 50–63 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mostofsky, E. et al. Modeling the association between particle constituents of air pollution and health outcomes. Am. J. Epidemiol.176, 317–326 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Scheers, H. et al. Does air pollution trigger infant mortality in Western Europe? A case-crossover study. Environ. Health Perspect.119, 1017–1022 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Casas, L. et al. Does air pollution trigger suicide? A case-crossover analysis of suicide deaths over the life span. Eur. J. Epidemiol.32, 973–981 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings described in this manuscript are available in the article and in the Supplementary Information. The disease onset data was obtained from the Chinese Cardiovascular Association (CCA) Database-Chest Pain Center. Due to data management requirements and patients’ privacy considerations, access to the disease onset data can be obtained by contacting the corresponding authors, Junbo Ge (ge.junbo@zs-hospital.sh.cn), Yong Huo (huoyong@263.net.cn), and Haidong Kan (kanh@fudan.edu.cn), and requests will be addressed within 12 weeks. The air pollution data were obtained from Tracking Air Pollution in China (TAP) dataset, accessible at http://tapdata.org.cn. Meteorological data were sourced from the fifth generation atmospheric reanalysis product (ERA5), accessible at https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/search?type=dataset. Source data are provided with this paper.

R codes for statistical analysis are available upon request from the corresponding authors, Junbo Ge (ge.junbo@zs-hospital.sh.cn), Yong Huo (huoyong@263.net.cn), and Haidong Kan (kanh@fudan.edu.cn). We will respond to the requests within 2 weeks.