Abstract

One of the most important functions of the plant hormone abscisic acid (ABA) is to induce stomatal closure by reducing the turgor of guard cells under water deficit. Under environmental stresses, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), an active oxygen species, is widely generated in many biological systems. Here, using an epidermal strip bioassay and laser-scanning confocal microscopy, we provide evidence that H2O2 may function as an intermediate in ABA signaling in Vicia faba guard cells. H2O2 inhibited induced closure of stomata, and this effect was reversed by ascorbic acid at concentrations lower than 10−5 m. Further, ABA-induced stomatal closure also was abolished partly by addition of exogenous catalase (CAT) and diphenylene iodonium (DPI), which are an H2O2 scavenger and an NADPH oxidase inhibitor, respectively. Time course experiments of single-cell assays based on the fluorescent probe dichlorofluorescein showed that the generation of H2O2 was dependent on ABA concentration and an increase in the fluorescence intensity of the chloroplast occurred significantly earlier than within the other regions of guard cells. The ABA-induced change in fluorescence intensity in guard cells was abolished by the application of CAT and DPI. In addition, ABA microinjected into guard cells markedly induced H2O2 production, which preceded stomatal closure. These effects were abolished by CAT or DPI micro-injection. Our results suggest that guard cells treated with ABA may close the stomata via a pathway with H2O2 production involved, and H2O2 may be an intermediate in ABA signaling.

The plant hormone abscisic acid (ABA) regulates many important plant developmental processes, and induces tolerance to different stresses including drought, salinity, and low temperature (Giraudat et al., 1994). ABA production is increased in tissues during these stresses, and this causes a variety of physiological effects, including stomata closure in leaves. By opening and closing stomata, the guard cells control transpiration to regulate water loss or retention. Despite the recognitions of the central role played by ABA in regulating stomatal function, the signal transduction events leading to alterations to the stomatal aperture remain incompletely understood (Schroeder et al., 2001). Previous evidence showed that an elevation of cytosolic Ca2+, an increase in pH, and a reduction in K+, Cl−, and organic solute content in both guard cells surrounding the stomatal pore, are downstream elements of ABA-induced stomatal closure (MacRobbie, 1998; Assmann and Shimazaki, 1999), although their spatiotemporal relationships are merely understood. In addition, cADP-Rib, phospholipase C, and phospholipase D have been identified as signaling molecules in the ABA response, and exerting their effects by regulating cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) and inward K+ channels (Wu et al., 1997; Leckie et al., 1998; Jacob et al., 1999; Staxen et al., 1999). Furthermore, Ca2+ channels and anion channels at the plasma membrane of stomatal guard cells are activated by hyperpolarization and ABA (Pei et al., 2000; Allen et al., 2000; Hamilton et al., 2000; Li et al., 2000), and an increase in [Ca2+]i resulting from the activation of Ca2+ channels leading to Ca2+ influx is known to inactivate inward-rectifying K+ channels, biasing the plasma membrane for solute efflux, which drives stomatal closure (Blatt and Grabov, 1997).

It is well known that utilization of molecular oxygen may be proceeded by a series of single electron transfers, which generates reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as superoxide anion (O2−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and other free radicals that react with, and thereby damage DNA, proteins, and lipids (Bowler et al., 1992; Scandalios, 1993). Earlier studies have indicated that the production of ROS is indirectly increased by stresses such as drought and chilling (Bowler et al., 1992; Fryer, 1992). It is interesting that H2O2 generated from an oxidative burst in pathogen-infected cells is thought to be a second messenger, which can both orchestrate the plant hypersensitive disease resistance by initialing a series of reactions (Levine et al., 1994) and mediate systemic signaling in the establishment of plant immunity (Neuenschwander et al., 1995; Allan and Fluhr, 1997; Alvarez et al., 1998). It has been found that O2− and other activated oxygen species are involved in the regulation of stomatal movement (Purohit et al., 1994). The oxidative stress resulting from exposure to methyl viologen (which generates O2.−) or H2O2 has a remarkable effect on stomatal aperture (Price, 1990), and exogenous H 2O2 can also induce [Ca2+]i increases in guard cells (McAinsh et al., 1996; Pei et al., 2000), comprising one or two separate transient increases, which are necessary for stomatal closure (Allen et al., 2000). Using recombinant aequorin in transgenic tobacco (Nicotiana plumbaginifolia), Price et al. (1994) have demonstrated that H2O2 stimulates a transient increase in [Ca2+]i in whole tobacco seedlings.

Although the role of H2O2 as an intermediate in ABA signaling in guard cells has been clearly examined in Arabidopsis plants (Pei et al., 2000), it was not known whether H2O2 acts as a second messenger for the induction of stomatal closure in response to ABA in other plants, and where is the source of H2O2 generation in guard cells. To further confirm the role of H 2 O 2 in the ABA signaling in other type plants, we therefore investigated the changes in stomatal behavior in response to H2O2 and ABA at the cellular level, and the relationships between ABA and H2O2 in ABA signaling cascade. Using Vicia faba plants, we provide evidence that H2O2 generation is an early event in ABA-induced stomatal closure.

RESULTS

ABA- and H2O2-Induced Changes in Stomatal Behavior

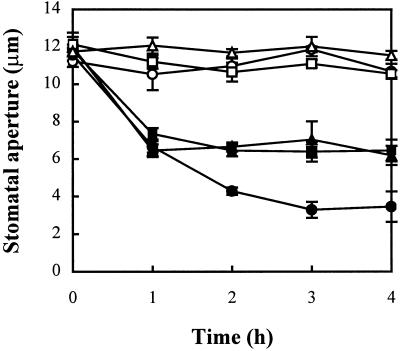

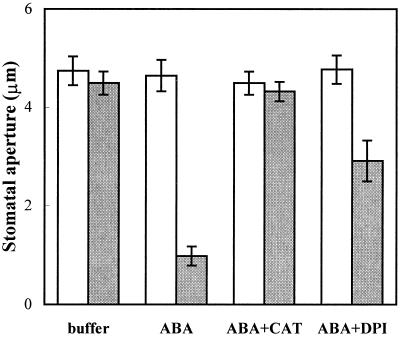

ABA, which is widely accepted as a stress signal, induces a reduction in stomatal aperture in a concentration-dependent manner (Schroeder et al., 2001). To gain insights into the mechanism of ABA-induced stomatal pore changes, we analyzed whether H2O2 might be involved in ABA effects on stomatal movements, in a manner similar to its effects in elicitor-induced defense responses. V. faba epidermal tissues were treated with 1 μm ABA in the presence of either 100 units mL−1 catalase (CAT) or 10 μm diphenylene iodonium (DPI), which either remove H2O2 or reduce the generation of H2O2, respectively (Levine et al., 1994; Alvarez et al., 1998; Lee et al., 1999). Both reagents reversed the ABA-induced stomatal closure (Fig. 1), suggesting that ABA promotes stomatal closure via a pathway involving H2O2. Treatments of the epidermis with CAT or DPI alone did not cause any changes of stomatal aperture (Fig. 1), which is the same as the results reported previously (Lee et al., 1999). It is possible that under noninducing conditions by ABA, the amount of H2O2 or the activity of NADPH oxidase is low in guard cells. It is important to keep the low level of H2O2 in the cells under optimal conditions, because the oxidative stress, resulting from ROS, is harmful to cell (Scandalios, 1993). These dangerous cascades are prevented by efficient operation of the cell's antioxidant defense (Noctor and Foyer, 1998). Therefore, the indirect evidence suggests a role for H2O2 as a common and critical intermediate for the signaling in ABA-induced stomatal closure.

Figure 1.

The effect of CAT and DPI on the ABA-induced stomatal closing. Isolated epidermis of V. faba was incubated in CO2-free MES [ 2-(N-morpholino)-ethanesulfonic acid]-KCl for 3 h under conditions promoting stomatal opening and then transferred to fresh CO2-free MES-KCl containing no ABA (○), 1 μm ABA (●), 1 μm ABA + 100 units mL−1 CAT (▪), 1 μm ABA + 10 μm DPI (▴), 100 units mL−1 CAT (□), or 10 μm DPI (Δ) only for another 4 h. Stomatal apertures were determined at 1-h intervals during the 4-h incubation. Values are the means of 120 measurements ±se.

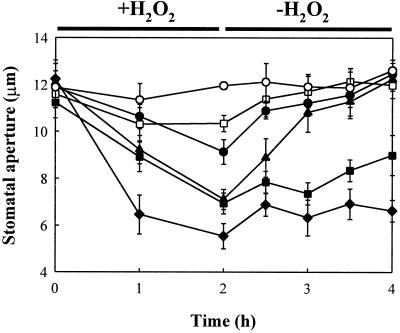

Previous studies have suggested that oxidative stress resulting from exposure to methyl viologen or H2O2 has a marked effect on stomatal aperture (Price, 1990; McAinsh et al., 1996; Allen et al., 2000; Pei et al., 2000). Exogenous application of H2O2 promoted stomatal closure (Fig. 2) in a dose-dependent manner. The effect of H2O2 on promotion of stomatal closure was significant (P < 0.05) at a concentration of H2O2 ≥ 10−5 m. The maximum promotion of stomatal closure was observed at 2 h after treatment with 10−3 m H2O2, under which conditions the stomatal apertures were 5.54 ± 0.54 μm, or 46% of the control value. However, in washout experiments, the effects of H2O2 (≤10−5 m) on stomatal aperture were completely reversible (Fig. 2). There was no significant (P < 0.05) difference between the apertures of stomata treated with H2O2 for 2 h followed by a 2-h washout and those that were incubated under the same conditions for 4 h in the absence of H2O2.

Figure 2.

Promotion of stomatal closure by H2O2 and its reversibility. Isolated epidermis of V. faba was incubated in CO2-free MES-KCl for 3 h under conditions promoting stomatal opening and then transferred to fresh CO2-free MES-KCl containing H2O2 (0 m, ○; 10−7 m, □; 10−6 m, ●; 10−5 m, ▴; 10−4 m, ▪; or 10−3 m, ♦) for 2 h under opening conditions, and stomatal apertures were determined at 1-h intervals during the 2-h H2O2 application (+H2O2), and at 30-min intervals during the 2-h H2O2 removal in “washout experiment” (−H2O2). Values are the means of 120 measurements ± se.

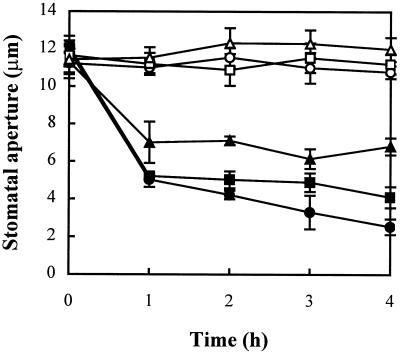

In plant cells, the most important reducing substrate for H2O2 removal is ascorbic acid (Noctor and Foyer, 1998). Ascorbate peroxidase uses two molecules of ascorbic acid to reduce H2O2 to water, with the concomitant generation of two molecules of monodehydroascorbate. The relatively high concentration of ascorbic acid in the cell ensures stable maintenance of the cellular redox state. When ascorbic acid was applied together with 10−5 m H2O2, the effects of H2O2-induced stomatal closure were partly abolished in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 3). Ascorbic acid alone induced a slight opening of stomata over untreated controls. Therefore, it appears that the interacellular redox state of cell reacts rapidly to the accumulation of H2O2 induced by ABA.

Figure 3.

Effects of ascorbic acid on the promotion of stomatal closure by H2O2. Isolated epidermis of V. faba was incubated in CO2-free MES-KCl for 3 h under conditions promoting stomatal opening and then transferred to fresh CO2-free MES-KCl containing no (○), 10−5 m H2O2 (●), 10−5 m H2O2 + 1 mm ascorbic acid (▪), 10−5 m H2O2 + 10 mm ascorbic acid (▴), 1 mm (□), or 10 mm (Δ) ascorbic acid only for another 4 h. Stomatal apertures were determined at 1-h intervals during the 4-h incubation. Values are the means of 120 measurements ± se.

ABA Induces H2O2 Production in Guard Cells

Having established that exogenous H2O2 is involved in the regulation of stomatal changes induced by ABA in the above epidermal strips bioassay experiments, we then examined whether external ABA might increase the level of H2O2 in guard cells. In this study, we used the oxidatively sensitive fluorophore dichlorofluorescein (H2DCF) to measure fast changes in intracellular H2O2 level directly. The nonpolar diacetate ester (H2DCF-DA) of H2DCF enters the cell (Allan and Fluhr, 1997) and is hydrolyzed into the more polar, nonfluorescent compound H2DCF, which therefore is trapped. Subsequent oxidation of H2DCF by H2O2, catalyzed by peroxidases, yields the highly fluorescent DCF (Cathcart et al., 1983). H2DCF-DA loads readily into guard cells, and its optical properties make it amenable to analysis using laser scanning confocal microscopy.

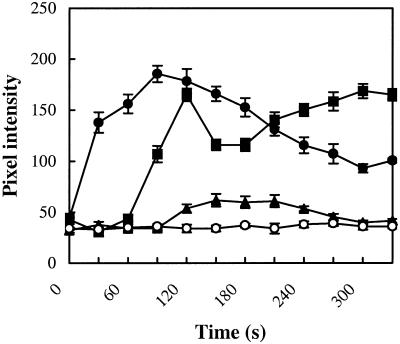

As shown in Figure 4, exogenous application of ABA enhanced the relative fluorescence intensity of DCF in guard cells, which represents as pixel intensity averaged over the entire cells, and the effects were dose dependent. A single cell assay also illustrated that 1 μm ABA significantly induced increases in DCF fluorescence intensity in guard cells, and the H2O2 elevation was observable throughout the entire surface of V. faba guard cells treated with ABA for 5 min (Fig. 5, A–F).

Figure 4.

Effects of ABA on the DCF fluorescence in guard cells. (○), 0 μm; (▴), 0.1 μm; (▪), 1 μm; and (●), 10 μm ABA. Each time point represents the mean of 10 measurements of pixel intensity of the whole cell determined in three independent experiments (±se).

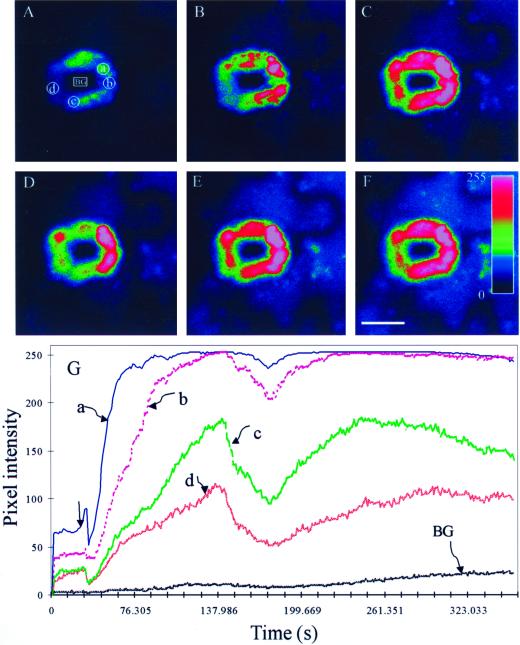

Figure 5.

Exogenous ABA-induced production of H2O2 in guard cells. A, A pair of guard cells loaded with DCFH-DA before the addition of 1 μm ABA. B through F, The same cells shown in A at 60, 120, 180, 240, and 300 s after the addition of 1 μm ABA, respectively. G, Time course changes in the pixel intensity of selected cytosolic regions as represented by the boxes in A. BG represents background fluorescence selected region of stomatal pore. The figures shows representative fluorescence image and time course from three independent experiments. The pseudocolor key is shown in the bar (F), which was applied to pixel intensity values (0–255) for all of the six fluorescence images. Scale bar represents 10 μm for all of the images. Arrow in G indicates the addition of ABA.

To determine which cellular compartments underwent increases in fluorescence intensity, subcellular regions were delineated using bright-field analysis as previously described (Allan and Fluhr, 1997). Chloroplast regions can be easily defined in bright field under microscope, whereas the cytosol was the region devoid of visible organelles, possibly including cytoplasmic and vacuolar regions. Time course quantitative analysis was performed in the chloroplast (area a), and the cytosol (areas b–d) as shown in Figure 5G. The earliest increase in ABA-induced H2O2 was in the region of chloroplast. This result is similar to the early observation that the earliest increase in DCF fluorescence induced by cryptogein was in the chloroplastic regions in guard cells (Allan and Fluhr, 1997).

It was noticed that the ABA-induced increase in H2O2 production in the presence of 10 μm ABA in guard cells for different periods exhibited a biphasic pattern of changes, whereby about 2-min incubation increased and 2.5-min incubation decreased the DCF fluorescence intensity compared with their respective control values (Fig. 4). The mean period of the biphasic pattern in the treatment of 1 μm ABA displayed slightly changes over 10 μm ABA treatment, which shows 1-min incubation increase and 1-min decrease in H2O2 generation. This was also the case when the H2O2 production in selected different cytosolic regions was measured in the presence of 1 μm ABA (Fig. 5G). It is well known that high doses of H2O2 are cytotoxic (Bowler et al., 1992; Scandalios, 1993). A state of moderately increased levels of interacellular H2O2 is referred to as oxidative stress. The biphasic pattern of H2O2 production in guard cells, acting as cell signaling messenger for H2O2, might allow all cells to tightly control their level within a very narrow range. The homeostatic modulation of oxidant levels is a highly efficient mechanism that appeared in evolution. This observation might be consistent with the early results that the cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations of differing amplitudes and frequencies induced by H2O2 (Allen et al., 2000).

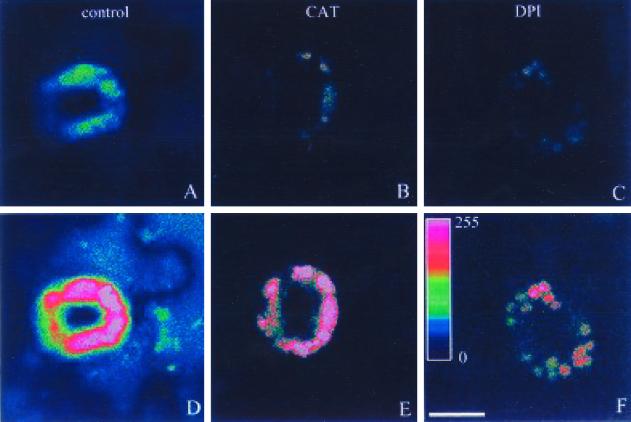

The Effects of CAT and DPI on H2O2 Generation Induced by ABA

H2O2 is extremely sensitive to CAT, and flavin-dependent enzymes, including the mammalian NADPH oxidase, are strongly inhibited by DPI (Alvarez et al., 1998; Potikha et al., 1999). As shown in Figure 5, A through F, the increase of fluorescence in guard cells treated with ABA was accompanied by an increase of fluorescence in adjacent epidermal cells. We had expected that epidermal cells treated with ABA might also produce H2O2. However, the following experiments argue against this as conclusion, and suggest that the H2O2 in the epidermal cells came from the guard cells. Addition of CAT before ABA treatment abrogated the increases in fluorescence in guard cells and their adjacent epidermal cells, and the epidermal cells were more sensitive to exogenous CAT than guard cells. A possible explanation for this phenomenon is that ABA-induced H2O2 was dissipated from guard cells to their peripheries, which was then blocked by the exogenously added CAT remaining in the apoplast. In a parallel experiment, although 10 μm DPI partly abolished ABA-induced fluorescence, the fluorescence in the chloroplasts was much more enhanced than that before ABA treatment (Fig. 6, C–F). This implies that the reduction of fluorescence intensity is due to the generation of H2O2 through flavin-dependent enzymes (including NADPH oxidase) blocked by DPI. However, the production of H2O2 from chloroplasts was not inhibited by DPI. These results further indicated that NADPH oxidase was activated by exogenous ABA treatment, and the oxidative environment of the chloroplasts was enhanced by ABA.

Figure 6.

Effects of CAT and DPI on ABA-induced H2O2 in guard cells. A through C, Guard cells loaded with DCFH-DA before the addition of 1 μ 77 ABA, in which cells (B and C0 in the presence of CAT (100 units mL−1) and DPI (10 μm), respectively. D–F, Cells shown in A through C, respectively, 300 s after the addition of 1 μm ABA. The pseudocolor key in F is shown within the bar, which was applied to pixel intensity values (0–255) for all of the six fluorescence images. Scale bar represents 10 μm for all of the images.

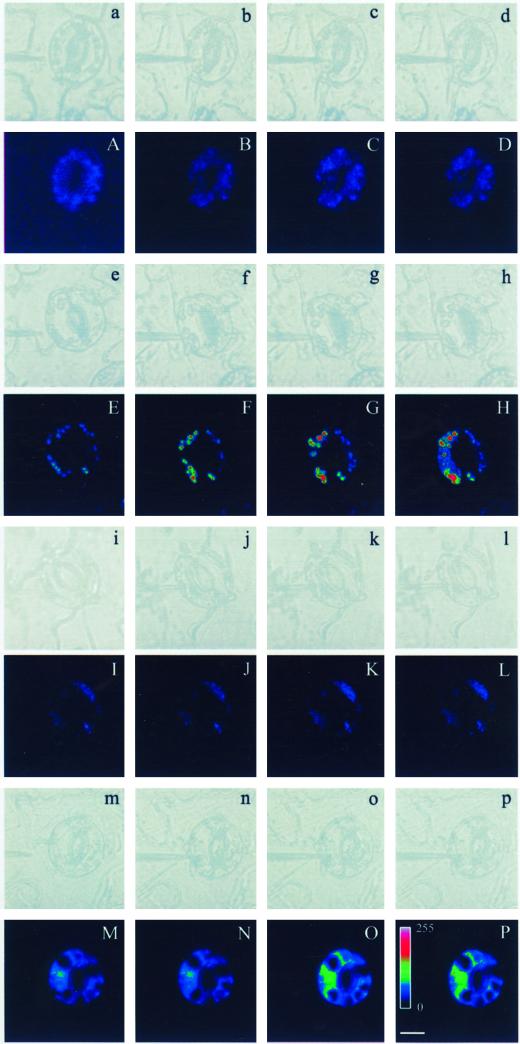

The Effects of Intracellular ABA on the Generation of H2O2 by Guard Cells and on the Stomatal Aperture

There has been no conclusive identification of an ABA receptor in plant cells. Previous work, including stomata closure induced by the ABA microinjected into guard cells, indicates an internally localized ABA reception site (Allan et al., 1994; Schwartz et al., 1994). An external reception site has also been suggested (Anderson et al., 1994), and these two possibilities are not mutually exclusive, i.e. there could be ABA reception sites both inside and outside the cell (MacRobbie, 1995). As shown in the above experiments, externally added ABA induced production of H2O2, which promoted stomatal closure. This raised the question as to whether intracellular ABA might have the same effects. To answer this question, we microinjected or comicroinjected reagents into guard cells, and examined DCF fluorescence in one of the paired guard cells at different times after microinjection. We found that ABA microinjection induced H2O2 production in the injected guard cell, and with increase of treatment time, the injected cells exhibited more rapid increase in DCF fluorescence than their uninjected counterparts (Fig. 7, E–H). CAT (100 units mL−1) completely abolished ABA-induced fluorescence increases in V. faba guard cells following microinjection (Fig. 7, I–L), which is the same as the results from the microinjection of buffer without ABA and CAT (Fig. 7, A–D). However, following comicroinjection of ABA and DPI, the cells showed DCF fluorescence increases only in the regions where chloroplasts were located (Fig. 7, M–P), which is similar to the observations that cells treated using externally added ABA in the presence of DPI (Fig. 6, C and F). It looks like the location of increase in DCF fluorescence might also be near the regions of the nucleus from the image (Fig. 7, M–P). Moreover, it is clearly observed that there are several green particles corresponding to its fluorescence images under bright-light microscope. This at least indicated that oxidized dye accumulating either in the regions of chloroplasts or in the region of the nucleus.

Figure 7.

Laser scanning confocal imaging of (co) microinjection reagents into guard cells. A, E, I, and M, Guard cell loaded with H2DCF-DA before microinjection. B through D, F through H, J through L, and M through P, Cells shown in A, E, I, and M 15, 60, and 120 s, respectively, after microinjection buffer (A–D), ABA (1 μ 77; E–H), ABA (1 μm) and CAT (100 units mL−1; I–L), and ABA (1 μm) and DPI (10 μ 77; M–P). a through p, Bright-light images corresponding to fluorescence images (A–P, respectively). The pseudocolor key in L is shown within the bar, which was applied to pixel intensity values (0–255) for all of the fluorescence images. Scale bar represents 10 μm for all of the images.

In considering the source of H2O2 in the cellular regions, care must be taken to prevent DCF sequestration into cellular compartments. Previous studies have shown that such problems cannot arise with H2DCF-DA-based assays for H2O2 production, due to relatively high levels of peroxidase activities in cytosol of guard cells (Allan and Fluhr, 1997), resulting in H2DCF-DA deacetylated to essentially non-permeate H2DCF, which is nonfluorescent but became oxidized fluorescent, and also non-permeating DCF (Cathcart et al., 1983). On the other hand, our results indicate that CAT (100 units mL−1) completely abolished ABA-induced fluorescence increases, including chloroplasts, in V. faba guard cells following microinjection (Fig. 7, I–L). CAT sensitivity rules out the possibility that DCF is sequestered into chloroplast because the exogenously injected CAT remains in the cytoplast.

It is important that 45 min after microinjection of ABA into guard cells (see “Materials and Methods”), the stomatal half-aperture displayed a significant (P < 0.05) reduction, from 4.643 ± 0.320 μm to 0.978 ± 0.192 μm. Comicro-injection of ABA and DPI resulted in a reduction in stomatal half-aperture from 4.769 ± 0.287 μm to 2.910 ± 0.417 μm, whereas comicro-injection of ABA and CAT resulted in no significant (P < 0.05) change in the half-aperture of the stomata, which is similar to the results following microinjection with buffer alone (Fig. 8) These findings suggest that H2O2 is a possible intermediate of the signal transduction pathway of ABA, and/or an ABA reception site is localized internally.

Figure 8.

Effects of reagents or buffer microinjection on stomatal aperture in V. faba. One guard cell in a pair was injected. In each case, white bars (□) represent the half-apertures of the uninjected guard cells in the pairs and gray bars (▩) represent the half-aperture of the injected guard cells in the pairs. The stomatal aperture measurements were performed at 45 min after microinjection of ABA into guard cells. Values shown are the means ± se (n = 10 for each treatment).

DISCUSSION

Under stress conditions, ABA and H2O2 are commonly generated in many biological systems (Assmann and Shimazaki, 1999; Potikha et al., 1999). It has been widely confirmed that ABA regulates stomatal movement as a stress signal (Assmann and Shimazaki, 1999), yet there remain considerable gaps in our knowledge regarding a detailed description of the events and underlying signal transduction mechanisms involved in stomatal closing (MacRobbie, 1998). ROS appear to play a crucial role in physiological and pathological processes of plants. H2O2, in particular, has been previously implicated as a second messenger in the regulation of the plant hypersensitive response (Mehdy, 1994; Low and Merida, 1996) and plays an important intermediary role in the ABA signal transduction pathway leading to the induction of the Cat1 gene (Guan et al., 2000).

Here, we provide new evidence that H2O2 is involved in ABA-induced stomatal movement in V. faba, which is consistent with recent findings in Arabidopsis plants (Pei et al., 2000). The following results support this conclusion: (a) exogenously added H2O2 induced stomatal closure, (b) scavenging of H2O2 and inhibiting H2O2 generation reversed the H2O2- or ABA-induced stomatal closure, and (c) H2O2 generation coincided with stomatal closure. In addition, our previous work using voltage clamp method has demonstrated that the stomatal closure induced by externally applied H2O2 is partially due to the inhibition of K+ uptake and the activation of K+ release through K+ channels on the plasma membrane of guard cells (An et al., 2000). McAinsh et al. (1996) have also provided evidence that oxidative stress induces stomatal closure, and an increase in cytosolic free Ca2+ concentration in guard cells of Commelina communis. The direct recording of Ca 2+ currents have resulted recently in a breakthrough (Hamilton et al., 2000; Pei et al., 2000), leading to the discovery of H2O2-activated Ca2+ channels as an important part of the mechanism for ABA-induced stomatal closure (Pei et al., 2000). It is interesting that H2O2 may play different roles during different biological processes. In plant defense responses, H2O2 functions as a signal molecule. On the other hand, their production during the environmental stresses is thought to be a byproduct of stress metabolism and is thought to induce cellular damage.

In the washout experiments, at concentrations lower than 10−5 m, the effects of H2O2 on stomatal behavior were reversible, whereas at concentrations higher than 10−5 m, the effects were irreversible (Fig. 2), which is the same as that seen in previous work (McAinsh et al., 1996). This implies that at low concentrations the effects of H2O2 may be due to the activation of a signaling cascade, whereas at high concentrations the effects of H2O2 may be due to the membrane integrity changes. The fact that H2O2 production preceded stomatal closure in guard cells challenged with externally or internally added ABA (Figs. 5 and 7, E–H), and that the ABA-induced stomatal closure was reversible by washout experiments (data not shown), indicates that ABA-stimulated H2O2 does not damage guard cells, and it can induce stomatal closing that can be reversed by other stimuli.

In higher plants, ROS can be generated by several different pathways (Allan and Fluhr, 1997; Bolwell et al., 1998). These pathways may include a cell wall-localized peroxidase (Bolwell et al., 1995), amine oxidases (Allan and Fluhr, 1997), non-flavin NADPH oxidases (Van Gestelen et al., 1997), and NADPH oxidases, which resemble the flavin-containing NADPH oxidases activated by Rac in leukocytes (Xing et al., 1997).

It is important that the highly energetic reactions of photosynthesis and an abundant oxygen supply make the chloroplast a particularly rich potential source of ROS. This involves O2 competing for electrons from photosystem I, thereby leading to the generation of ROSs through the Mehler reaction (Foyer, 1997). It has been suggested that O2 might serve as an alternative electron acceptor when NADPH availability is limited, which would result in increased O2− production (Polle, 1997). It should be noted that guard cells contain chloroplasts, which can both produce NADPH and ATP (Zeiger et al., 1981), and release O2 (Wu and Assmann, 1993) by the action of functional light reaction. However, the amount of Rubisco is very low in guard cell chloroplasts as compared with that in leaf cell chloroplasts, and the CO2 assimilation catalyzed by Rubisco through photosynthesis only provides 2% of sugar required for stomatal opening (Reckmann et al., 1990). This indicates that it may be possible for guard cells to accumulate high chemical energy products such as NADPH and ATP. The question of whether Rubisco activity actually contributes significantly to osmotic buildup associated with stomatal opening is still an open question (MacRobbie 1997). Therefore, until now, the exact function of chloroplast in guard cells remains unclear.

We have investigated the subcellular source and possible molecular events involved in H2O2 generation in guard cells challenged with ABA. Time course experiments (Fig. 5) showed that chloroplasts might be the main regions of H2O2 production. The inhibition of both ABA- or H2O2-induced stomatal closing (Figs. 1 and 3) and ABA-induced H2O2 elevation of guard cells (Fig. 6, B and E) by externally applied CAT showed that H2O2 might also act externally to the guard cell plasma membrane (Lee et al., 1999) because CAT is not likely to cross the plasma membrane. This is consistent with the high permeability of the membrane to H2O2 (Yamasaki et al., 1997). To assess ABA-induced H2O2 levels in vivo, we co-injected reagents into guard cells, finding that internally applied CAT and DPI completely or partly inhibited ABA-induced H2O2 production and half-stomatal closure (Fig. 7, I–L and M–P). This further indicated that NADPH oxidase located at plasma membrane, as well as light reaction in chloroplasts, contributes to H2O2 production, and that there might be internal ABA reception sites in guard cells. In fact, various environmental perturbations (e.g. intense light, drought, temperature stress, etc.) can induce excessive ROS, which may overwhelm the defense system and necessitate additional defense (Scandalios, 1993; Foyer et al., 1994). Therefore, guard cell generated H2O2 and O2− under different environmental conditions, which can regulate stomata closure.

In summary, the accumulated evidence suggest that H2O2 can be generated in guard cells, thereby providing new intermediates for ABA signaling. These results not only suggest the mechanism of stomatal closure under stresses such as drought and high-intensity light, during which an oxidative burst has been found in non-stomatal tissues (Legendre et al., 1993; Auh and Murphy, 1995), but also provide a possible explanation for the function of chloroplasts in guard cells. At present, the spatio-temporal relationships between H2O2 and other intracellular second messengers (Ca2+, IP3, and pH) remain unknown.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

Dichlorofluorescin diacetate (H2DCF-DA; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide to produce a 50-mm stock solution, which was aliquoted. ABA (±) and DPI was from Sigma (St. Louis). CAT (bovine liver) was from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). Unless stated otherwise, the remaining chemicals were of analytical grade from Chinese companies.

Plant Material

Broad bean (Vicia faba) was grown in a greenhouse with a humidity of about 70%, a photon flux density of 0.20 to 0.30 mmol m−2 s−1, and an ambient temperature (day/night 25°C ± 2°C/20°C ± 2°C). Immediately prior to each experiment, the epidermis was peeled carefully from the abaxial surface of the youngest, fully expanded leaves of 4-week-old plants, and cut into 5-mm lengths.

Epidermal Strip Bioassay

Stomatal bioassay experiments were performed as described (McAinsh et al., 1996) with slight modifications. To study the promotion of stomatal closure by ABA and H2O2, freshly prepared abaxial epidermis was first incubated in CO2-free 50 mm KCl/10 mm MES-Tris, pH 6.15 (MES-KCl) for 3 h under conditions promoting stomatal opening (at 22°C–25°C, under a photon flux density of 0.20–0.30 mmol m−2 s−1) to open the stomata. The epidermis was then transferred to CO2-free MES-KC in the presence of ABA (0.0, 0.1, 1.0, and 10 μm) or H2O2 (0, 10−3, 10−4, 10−5, 10−6, and 10−7 m) with and without CAT, DPI, or ascorbic acid, for another 2 h, or as indicated. In washout experiments, strips were subsequently transferred to fresh CO2-free MES-KCl for 2 h, and stomatal apertures were determined via confocal microscopy at 30-min intervals. In all cases, the strips were subsequently examined under the microscope to determine the aperture of the stomatal pores.

Dye Loading

The epidermal strips, previously incubated for 3 h under conditions promoting stomatal opening, were placed into loading buffer with 10 or 50 mm Tris-KCl (pH 7.2) containing 50 μm of H2DCF-DA. Before further experiments, peels were pre-incubated in the dark for 10 to 15 min.

Micro-injection of Stomatal Guard Cells

The peels loaded with H2DCF-DA were floated on fresh buffer (Tris-KCl at 10 or 50 mm, pH 7.2) to wash off excess dye in the apoplast, and were then affixed to a polyacrylate plastic dish with 0.5 mL of H2DCF-DA-free loading buffer. We then performed microinjection into guard cells under a TE300 (objective 40 × 0.60 Plan Fluor) inverted microscope (Nikon, Tokyo) with a micromanipulator system (188NE, Narishige Scientific Instruments, Tokyo) according to a method with slight modification of methods of Ma et al. (1999) and Perona et al. (1999). Micropipettes (tip diameter 0.5 μm) for injection were made from borosilicate glass capillaries (GD-1, Narishige Scientific Instruments) using a micropipette puller (PC-10, Narishige Scientific Instruments). Micropipetter tips were front filled with injection reagents by applying a negative pressure.

To examine the effects of microinjection on stomatal behavior, stomata with apertures of 8 to 10 μm were chosen for microinjection of different reagents (Gilroy et al., 1991; Schwartz et al., 1994). Micropipettes contained buffer (Tris-KCl, pH 7.2) as well as the treatment reagents. The microinjection tip reached no more than 3 μm into the cytoplasm. Five minutes after microinjection, the micropipette tips were slowly removed and the cells allowed to recover for approximately 10 min. Guard cells that failed to recover normally and that had any visible morphological changes, such as turgid losses and differences in organelle shape and distribution between injected guard cells and noninjected counterparts (Gilroy et al., 1991), were discarded. Epidermal strips with injected stomata that recovered (or nearly recovered) to the same aperture as those on the remaining part of the epidermal strip, and for which both the injected and uninjected cells of a single stoma exhibited the same increase in turgor, were maintained under white light at 0.20 mmol m−2 s−1 for another 30 min, and the stomatal apertures were recorded and measured. Fluorescein diacetate staining was used to further confirm cellular viability after each experiment. Criteria for cells damaged by injected were those described by Gilroy et al. (1991).

Laser Scanning Confocal Microscopy

Examinations of peel fluorescence was performed using a MicroRadiance Laser scanning confocal microscope (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), with the following settings: ex = 488 nm, em = 525 nm, power 3%, zoom 4, mild scanning, frame 512 × 512, and Timecourse and Photoshop software. To enable the comparison of changes in signal intensity, confocal images were taken under identical exposure conditions (in manual setup) for all samples. ABA or other reagents were added directly to the buffer or microinjected into guard cells during the time course. The experiments were repeated at least three times in each treatment, and the selected confocal image represented the same results from about 10 time course experiments.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Michael Deyholos and Shuhua Yuan (University of Arizona, Tucson) for critical reading of this manuscript.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 3990407021 to C.-P.S.) and by the National Key Basic Research Special Funds (grant no. G1999011700 to C.-P.S.).

LITERATURE CITED

- Allan AC, Fluhr R. Two district sources of elicited reactive oxygen species in tobacco epidermal cells. Plant Cell. 1997;9:1559–1572. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.9.1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan AC, Fricker MD, Ward JCL, Beale MH, Trewavas AJ. Two transduction pathways mediate rapid effects of abscisic acid in Commelinaguard cells. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1319–1328. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.9.1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen GJ, Chu SP, Schumacher K, Shimazaki CT, Vafeados D, Kemper A, Hawke SD, Tallman G, Tsien RY, Harper JF. Alternation of stimulus-specific guard cell calcium oscillations and stomatal closing in Arabidopsis det3mutant. Science. 2000;289:2338–2342. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5488.2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez ME, Pennell RI, Meijer PJ, Ishikawa A, Dixon RA, Lamb C. Reactive oxygen intermediates mediate a systemic signal network in the establishment of plant immunity. Cell. 1998;92:773–784. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81405-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An GY, Song CP, Zhang X, Jing YC, Yang DM, Huang MJ, Wu CH, Zhou PA. Effect of hydrogen peroxide on stomatal movement and K+ channel on plasma membrane in Vicia fabaguard cell. Acta Phytophysiol Sin. 2000;26:458–463. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson BE, Ward JM, Schroeder JI. Evidence for an extracellular reception site for abscisic acid in Commelinaguard cells. Plant Physiol. 1994;104:1177–1183. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.4.1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assmann SM, Shimazaki KI. The multisensory guard cell, stomatal responses to blue light and abscisic acid. Plant Physiol. 1999;119:809–815. doi: 10.1104/pp.119.3.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auh CK, Murphy TM. Plasma membrane redox enzyme is involved in the synthesis of O2−. and H2O2 by Phytophythoraelicitor-stimulated rose cell. Plant Physiol. 1995;107:1241–1247. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.4.1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatt MR, Grabov A. Signaling gates in abscisic acid-mediated control of guard cell ion channels. Physiol Plant. 1997;100:481–490. [Google Scholar]

- Bolwell GP, Butt VS, Davies DR, Zimmerlin A. The origin of the oxidative burst in plants. Free Radic Res. 1995;23:517–532. doi: 10.3109/10715769509065273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolwell GP, Davies DR, Gerrish C, Auh C-K, Murphy TM. Comparative biochemistry of the oxidative burst produced by rose and French bean cells reveals two distinct mechanisms. Plant Physiol. 1998;116:1379–1385. doi: 10.1104/pp.116.4.1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowler C, van Montagu M, Inze D. Superoxide dismutase and stress tolerance. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1992;43:83–116. [Google Scholar]

- Cathcart R, Schwiers E, Ames BN. Detection of picomol levels of hydroperoxides using a fluorescent dichlorifluorescein assay. Anal Biochem. 1983;134:111–116. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90270-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foyer CH. Oxygen metabolism and electron transport in photosynthesis. In: Scandalios JG, editor. Oxidative Stress and the Molecular Biology of Antioxidant Defenses. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 587–621. [Google Scholar]

- Foyer CH, Descourvieres P, Kunert KJ. Protein against oxygen radicals: an important defense mechanism studied in transgenic plants. Plant Cell Environ. 1994;17:507–523. [Google Scholar]

- Fryer MJ. The antioxidant effect of thylakoid vitamin E (a-tocopherol) Plant Cell Environ. 1992;15:381–392. [Google Scholar]

- Gilroy S, Fricker MD, Read ND, Trewavas AJ. Role of calcium on signal transduction of Commelinaguard cells. Plant Cell. 1991;3:333–344. doi: 10.1105/tpc.3.4.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraudat J, Parcy F, Bertauche N, Gosti F, Leung J. Current advances in abscisic acid action and signaling. Plant Mol Biol. 1994;26:1557–1577. doi: 10.1007/BF00016490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan L, Zhao J, Scandalios JG. Cis-elements and trans-factors that regulate expression of the maize Cat1 antioxidant gene in response to ABA and osmotic stress: H2O2is the likely intermediary signaling molecule for the response. Plant J. 2000;22:87–95. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton D, Hills A, Kohler B, Blatt MR. Ca2+channels at the plasma membrane of stomatal guard cells are activated by hyperpolarization and abscisic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4967–4972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.080068897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob T, Ritchie S, Assmann SM, Gilroy S. Abscisic acid signal transduction in guard cells is mediated by phospholipase D activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12192–12197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.12192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leckie CP, McAinsh MR, Allen GJ, Sanders D, Hetherington AM. Abscisic acid-induced stomatal closure mediated by cyclic ADP-ribose. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15837–15842. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Choi H, Suh S, Doo I-S, Oh K-Y, Choi EJ, Taylor SAT, Low PS, Lee Y. Oligogalacturonic acid and chitosan reduce stomatal aperture by inducing the evolution of reaction oxygen species from guard cells of tomato and Commelina communis. Plant Physiol. 1999;121:147–152. doi: 10.1104/pp.121.1.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legendre L, Rueter S, Heinstein PF, Low PS. Characterization of the oligogalacturonide-induced oxidative burst in cultured soybean (Glycine-max) cells. Plant Physiol. 1993;102:233–240. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.1.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine A, Tenhaken R, Dixon RA, Lamb C. H2O2from the oxidative burst orchestrates the plant hypersensitive response. Cell. 1994;79:583–593. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90544-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Wang XQ, Watson MB, Assmann SM. Regulation of abscisic acid-induced stomatal closure and anion channels by guard cell AAPK kinase. Science. 2000;287:300–303. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5451.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low PS, Merida JR. The oxidative burst in plant defense-function and signal transduction. Plant Physiol. 1996;96:533–542. [Google Scholar]

- Ma LG, Xu XD, Cui SJ, Sun DY. The presence of a heterotrimeric G protein and its role in signal transduction of extracellular calmodulin in pollen germination and tube growth. Plant Cell. 1999;11:1351–1363. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.7.1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacRobbie EAC. ABA-induced ion efflux in stomatal guard cells: multiple actons of ABA inside and outside the cell. Plant J. 1995;7:565–576. [Google Scholar]

- MacRobbie EAC. Signaling in guard cells and regulation of ion channel activity. J Exp Bot. 1997;48:515–528. doi: 10.1093/jxb/48.Special_Issue.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacRobbie EAC. Signal transduction and ion channels in guard cells. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B. 1998;353:1475–1488. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1998.0303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAinsh MR, Clayton H, Mansfield TA, Hetherington AM. Changes in stomatal behavior and cytosolic free calcium in response to oxidative stress. Plant Physiol. 1996;111:1031–1042. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.4.1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehdy MC. Active oxygen species in plant defense against pathogens. Plant Physiol. 1994;105:467–472. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.2.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuenschwander U, Vernooij B, Friedrich L, Uknes S, Kessmann H, Ryals J. Is hydrogen peroxide a second messenger of salicylic acid in systemic acquired resistance? Plant J. 1995;8:227–233. [Google Scholar]

- Noctor G, Foyer CH. Ascorbate and glutathione: keeping active oxygen under control. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mil Biol. 1998;49:249–279. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.49.1.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei ZM, Murata Y, Benning G, Thomine S, Klusener B, Allen GJ, Grill E, Schroeder JL. Calcium channels activated by hydrogen peroxide mediate abscisic acid signaling in guard cells. Nature. 2000;406:731–734. doi: 10.1038/35021067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perona R, Dolfi F, Feramisco J, Lacal JC. Microinjection of macromolecules into mammalian cells in culture. In: Lacal JC, Perona R, Feramisco J, editors. Microinjection. Basel: Birkauser Verlag; 1999. pp. 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Polle A. Defense against photoxidative damage in plants. In: Scandalios JG, editor. Oxidative Stress and the Molecular Biology of Antioxidant Defense. Cold Spring, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 623–666. [Google Scholar]

- Potikha TS, Collins CC, Johnson DI, Delmer DP, Levine A. The involvement of hydrogen peroxide in the differentiation of secondary walls in cotton fibers. Plant Physiol. 1999;119:849–858. doi: 10.1104/pp.119.3.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price AH. A possible role for calcium in oxidative plant stress. Free Radic Res. 1990;10:345–349. doi: 10.3109/10715769009149903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price AH, Taylor A, Ripley SJ, Griffiths A, Trewavas AJ, Knight MR. Oxidative signals in tobacco increase cytosolic calcium. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1301–1310. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.9.1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purohit S, Kumar GP, Laloraya M, Laloraya MM. Involvement of superoxide radical in signal transduction regulating stomatal movements. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;205:30–37. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reckmann U, Scheibe R, Raschke K. Rubisco activity in guard cells compared with the solute requirement for stomatal opening. Plant Physiol. 1990;92:246–253. doi: 10.1104/pp.92.1.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scandalios JG. Oxygen stress and superoxide dismutases. Plant Physiol. 1993;101:7–12. doi: 10.1104/pp.101.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder JI, Kwak JM, Allen GJ. Guard cell abscisic acid signaling and engineering drought hardiness in plants. Nature. 2001;410:327–330. doi: 10.1038/35066500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz A, Wu W-H, Tucker EB, Assmann SM. Inhibition of inward K+channels and stomatal response by abscisic acid: an intracellular locus of phytohormone action. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4019–4023. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.4019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staxen I, Pical C, Montgomery L, Gray J, Hetherington AM, McAinsh MR. Abscisic acid induces oscillations in guard-cell cytosolic free calcium that involve phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:1779–1784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gestelen P, Asard H, Caubergs RJ. Solubilization and separation of a plant plasma membrane NADPH-O2synthase from from other NAD(P) H oxidoreductases. Plant Physiol. 1997;115:543–550. doi: 10.1104/pp.115.2.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W, Assmann SM. Photosynthesis by guard cell chloroplasts of Vicia fabaL.: effects of factors associated with stomatal movements. Plant Cell Physiol. 1993;34:1015–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Kuzma J, Marechal E, Graeff R, Lee HC, Foster R, Chua NH. Abscisic acid signaling through cyclic ADP-Ribose in plants. Science. 1997;278:2054–2055. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5346.2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing T, Higgins VJ, Blumwald E. Race-specific elicitors of Cladosporium fulvumpromote translocation of cytosolic components of NADPH oxidase to the plasma membrane of tomato cells. Plant Cell. 1997;9:249–259. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.2.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki H, Sakihama Y, Ikehara N. Flavonoid-peroxidase reaction as a detoxification mechanism of plant cells against H2O2. Plant Physiol. 1997;115:1405–1412. doi: 10.1104/pp.115.4.1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeiger E, Armond P, Melis A. Fluorescence properties of guard cell chloroplasts: evidence for linear electron transport and light harvesting pigments of photosystems I and II. Planta. 1981;67:17–20. doi: 10.1104/pp.67.1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]