Abstract

Uptake and translocation of cationic nutrients play essential roles in physiological processes including plant growth, nutrition, signal transduction, and development. Approximately 5% of the Arabidopsis genome appears to encode membrane transport proteins. These proteins are classified in 46 unique families containing approximately 880 members. In addition, several hundred putative transporters have not yet been assigned to families. In this paper, we have analyzed the phylogenetic relationships of over 150 cation transport proteins. This analysis has focused on cation transporter gene families for which initial characterizations have been achieved for individual members, including potassium transporters and channels, sodium transporters, calcium antiporters, cyclic nucleotide-gated channels, cation diffusion facilitator proteins, natural resistance-associated macrophage proteins (NRAMP), and Zn-regulated transporter Fe-regulated transporter-like proteins. Phylogenetic trees of each family define the evolutionary relationships of the members to each other. These families contain numerous members, indicating diverse functions in vivo. Closely related isoforms and separate subfamilies exist within many of these gene families, indicating possible redundancies and specialized functions. To facilitate their further study, the PlantsT database (http://plantst.sdsc.edu) has been created that includes alignments of the analyzed cation transporters and their chromosomal locations.

Transport of metals and alkali cations across plant plasma and organellar membranes is essential for plant growth, development, signal transduction, nutrition, and also for use of plants in toxic metal phytoremediation. Alkali cation and metal transporters have been analyzed traditionally in great depth as models for understanding plant membrane transport. This tradition dates back to the classical studies of Epstein and colleagues, who analyzed potassium (K+) influx as a model for understanding nutrient uptake into roots (Epstein et al., 1963). These early studies suggested that plants utilize at least two pathways with different kinetics for nutrient uptake. This was a first glimpse at the complexity of transporters in plants that now, nearly 40 years later, is fully realized by the analysis of the complete genomic sequence of the plant Arabidopsis.

The first isolated plant transporter cDNAs were a phosphate translocator from spinach (Spinacia oleracea) chloroplasts (Flügge et al., 1989), a hexose transporter from Chlorella kessleri (Sauer and Tanner, 1989) followed by three proton ATPases (Boutry et al., 1989; Harper et al., 1989; Pardo and Serrano, 1989). Within 5 years, the use of heterologous expression in yeast and functional characterization in Xenopus laevis oocytes led to the identification of genes encoding a number of physiologically important plant transporters. In the past few years, the number of recognized membrane transporter families and homologous family members has exploded in large part due to heterologous complementation screens and sequencing of both plant expressed sequence tags (ESTs) and the Arabidopsis genome. The completion of the Arabidopsis genome now allows analysis of a complete set of transporter gene families in a single plant species.

In the present study, we have analyzed the sequences of known Arabidopsis plant cation transporter families, for which individual members have been previously functionally characterized. The reported analyses represent a starting point for functional genomic studies. Furthermore, our analyses provide an insight into the evolution of various cation transporter subfamilies within the genome. In addition, considering the large number of Arabidopsis membrane proteins with no known or presumed function, we expect that many new cation transporters will be identified in the future.

Uptake of cations into plant cells is driven by ATP-dependent proton pumps that catalyze H+ extrusion across the plasma membrane. The resulting proton motive force typically comprises a membrane potential of about −150 mV, and a pH difference of 2 units (which contributes another −120 mV to the proton motive force). Cation uptake can then be powered both through H+ symport and/or as a result of the negative membrane potential (Maathuis and Sanders, 1994; Schroeder et al., 1994; Hirsch et al., 1998). The plasma membrane H+-ATPases belong to a large family of so-called P-type ATPases of which there are 45 members in the Arabidopsis genome (analyzed in Axelsen and Palmgren, 2001).

Research on K+ transport has shown that transport of an essential cationic nutrient is often mediated by more than one family of partially redundant transporters. It has been proposed that functionally overlapping but structurally distinct transporters could provide plants with the ability to transport nutrients under various conditions, including differing energetic conditions, genetic defects, and the presence of toxic blocking cations (Schroeder et al., 1994). In the present article, we focus on transporters for plant nutrients including zinc (Zn2+), iron (Fe; two families), K+ (four families), and calcium (Ca2+; two families). Uptake of these nutrients is not only important for plant growth, but also for human nutrition. For example, Fe deficiencies are widespread (Guerinot, 2000a).

Cation transporters also play important roles in plant signaling. For example, Ca2+ and K+ channels are essential for transducing many hormonal and light signals in plants. Patch clamp studies have provided direct and “biochemical characterizations” demonstrating the diverse regulation and channel properties of multiple distinct classes of plant Ca2+ channels. However, it is surprising that the unequivocal identification of genes encoding Ca2+ influx channels in plants is still lacking. Among candidate genes that have been implicated in Ca2+ influx are the cyclic nucleotide-gated channel (CNGC) family (Schuurink et al., 1998; Köhler et al., 1999; Sunkar et al., 2000), a single Arabidopsis gene homologous to voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels (accession no. AF071527) and the wheat (Triticum aestivum) LCT1 transporter (Clemens et al., 1998). No LCT1 homologs are found in the Arabidopsis genome database or in genomes from non-plant species, indicating the need for genome sequences of other plant types. Note that LCT1 has repetitive sequences, which renders genomic sequencing difficult. Given the physiological complexity and importance of Ca2+ channels, genes and gene families encoding these signaling proteins will hopefully soon emerge.

Plant transporters also play important roles in shuttling potentially toxic cations across plant membranes. The cation selectivity filters of plant transporters often allow toxic cations to be transported, along with cationic nutrients. Powerful genetic approaches have been developed that allow high-throughput selection of point mutations that reduce or block transport of toxic cations, while maintaining nutrient transport (Rubio et al., 1995; Nakamura et al., 1997; Ichida et al., 1999; Rogers et al., 2000). Several of the transporters analyzed in the present article have been shown to transport toxic cations. Cadmium, for example, is transported by members of the Zn-regulated transporter (ZRT) Fe-regulated transporter (IRT)-like proteins (ZIP), natural resistance-associated macrophage proteins (NRAMP), and cation diffusion facilitator (CDF) families that are analyzed here (Guerinot, 2000b; Thomine et al., 2000; Persans et al., 2001). In addition, ATP-binding cassette transporters represent a large gene family, with members contributing to vacuolar sequestration of glutathione- and phytochelatin-complexed heavy metals (Rea et al., 1998; Theodoulou, 2000) and a complete analysis of ATP binding cassette transporter homologs in the Arabidopsis genome will be completed shortly (P. Rea and R. Sánchez-Fernández, personal communication; Sánchez-Fernández et al., 2001). Furthermore, several plant cation transporters have been reported to mediate transport of sodium (Na+), which is toxic at high concentrations leading to salinity stress. Of the transporters analyzed here, the HKT, KUP/HAK/KT, NHX, and salt overly sensitive (SOS1) transporters have all been shown to mediate Na+ transport and additional Na+ permeable transporters are certain to emerge. Genetic and physiological analyses will be needed to determine the functions and relative contributions of different transporters to nutrient and toxic metal transport in plants.

Computer-assisted analyses of the completed Arabidopsis genome sequence will be invaluable for assigning members to gene families (Ward, 2001) and several initial web sites displaying information on predicted Arabidopsis transporter families have been created. Accession nos. of Arabidopsis transporters belonging to known families are shown at http://www.biology.ucsd.edu/∼ipaulsen/transport/. The Arabidopsis Membrane Protein Library (http://www.cbs.umn.edu/arabidopsis/) displays information for each predicted membrane protein, including transporters, clustered into families based on homology. A PlantsT database has been assembled that will provide the results from functional genomic analyses of all Arabidopsis transporters (http://plantst.sdsc.edu/).

The presented analyses provide the first genome-wide study and discussion of important cation transporters in a plant, and will serve as a reference for future functional dissection of these membrane proteins. Furthermore, the presented phylogenetic analyses should aid in understanding the evolution of plant cation transport proteins.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Potassium Transporter Family

The alkali metal potassium (K+) is a major plant macronutrient and K+ is the most abundant cation in plants. Potassium transporters are required for the accumulation of potassium ions (K+) from soil and for their distribution throughout diverse plant tissues, for root and shoot growth, tropisms, cell expansion, enzyme homeostasis, salinity stress, stomatal movements, and osmoregulation. Therefore, it is not surprising to find a large number of genes in Arabidopsis encoding K+ transporters, which fall into either of four to five families (Fig. 1): two distinct K+ channel families (Fig. 2; 15 genes), Trk/HKT transporters (one gene), KUP/HAK/KT transporters (Fig. 3; 13 genes), and K+/H+ antiporter homologs (six genes). K+ channels are perhaps the best understood transporter family in plants in terms of gating, second messenger regulation, transport properties, and predicted functions in different plant cells and membranes. However, relatively little is known about the physiology of the K+ permeases and nothing at all about the K+/H+ antiporter homologs.

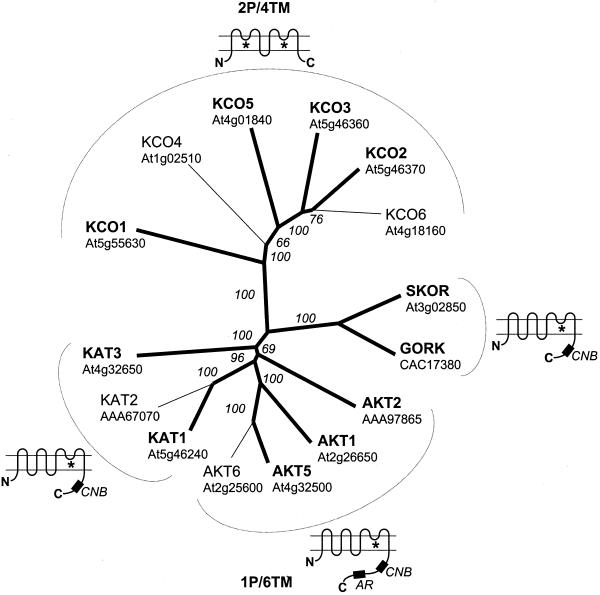

Figure 1.

Overview of Arabidopsis K+ transporters. A tree of all K+ transporters from Arabidopsis has five major branches: a, KUP/HAK/KT transporters (13 genes); b, Trk/HKT transporters (Na+ transporter; one gene); c, KCO (2P/4TM) K+ channels (six genes); d, Shaker-type (1P/6TM) K+ channels (nine genes); and e, K+/H+ antiporter homologs (six genes). Predicted membrane topologies for each branch are shown. The apparent absence of K+ channels of the 2P/8TM family is remarkable as is the diversity in the AtKUP/HAK/KT transporters. Proteins for which a complete cDNA sequence is available are indicated by bold letters and lines. Arabidopsis Genome Initiative (AGI) genome codes are given except for AtKUP3 = AtKUP4, AtHAK5, AtHKT1, GORK, KAT2, and AKT2 (GenBank accession nos.) because of errors in the sequences predicted by AGI. Programs used were HMMTOP (Tusnady and Simon, 1998) for topology predictions of the KEA and AtKUP/HAK/KT families, ClustalX (Thompson et al., 1997) for alignments, and graphical output produced by Treeview (Page, 1996). Values indicate the number of times of 1,000 bootstraps that each branch topology was found during bootstrap analysis.

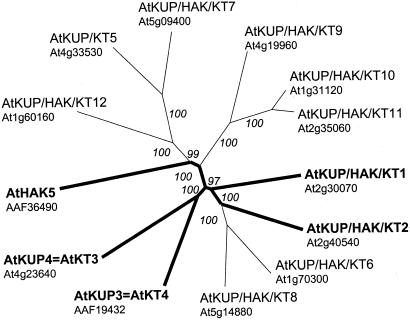

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree of Arabidopsis K+ channels. A non-rooted tree reflects the structural and functional properties of Arabidopsis K+ channels. The two major branches are the 2P/4TM-type and the 1P/6TM (Shaker)-type channels, as depicted by the sketches. For KAT1 the proposed topology has been confirmed experimentally (Uozumi et al., 1998). The 1P/6TM (Shaker-type) channels are further subdivided into the depolarization-activated SKOR and GORK and the KATs and AKTs. All the 1P/6TM channels possess a putative cyclic nucleotide-binding site (CNB), and AKT channels also have an ankyrin repeat consensus site (AR; see sketches). P-loops are labeled with asterisks. Proteins for which a complete cDNA sequence is available are indicated by bold letters and lines. Programs used were pfscan (http://www.isrec.isb-sib.ch/software/PFSCAN form.html) for motif searches, ClustalX (Thompson et al., 1997) for alignments, and Treeview (Page, 1996) for graphical output. Values indicate the number of times (in percent) that each branch topology was found during bootstrap analysis.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic tree of Arabidopsis KUP/HAK/KT (POT) transporters. Proteins for which the complete cDNA has been sequenced are printed in bold and are marked with bold lines. We are using the name AtKUP/HAK/KT except for four cases with conflicting numbers: The names AtKT5 (Quintero and Blatt, 1997) and AtHAK5 (Rubio et al., 2000) have been given to different genes, whereas AtKUP3 (Kim et al., 1998) and AtKT4 (Quintero and Blatt, 1997) have been used for the same gene, and so were AtKUP4 and AtKT3. Furthermore, AtKUP4 = AtKT3 corresponds to the TRH1 gene (Rigas et al., 2001). Programs used were ClustalX (Thompson et al., 1997) for alignments and Treeview (Page, 1996) for graphical output. Values indicate the number of times (in percent) that each branch topology was found during bootstrap analysis.

K+ Channels

Analysis and classification of K+ channel genes has been advanced by patch clamp studies characterizing their properties in plant cells (for review, see Schroeder et al., 1994; Maathuis et al., 1997), by functional characterization of K+ channel-encoding genes, and by the elucidation of a K+ channel structure (Doyle et al., 1998). The selectivity for K+ is structurally defined by four highly conserved pore-forming (P-) loops on the outer surface of the channel, each P-loop being embedded between two transmembrane (TM) domains. The functional channel is either a tetramer of α-subunits with one P-loop per subunit (Doyle et al., 1998) or possibly a dimer of α-subunits carrying two P-loops (the “two-pore” K+ channels; Goldstein et al., 1998; see insets in Fig. 2). Furthermore, α-subunits differ in the number of TM domains, with either two, four, six, or eight (Goldstein et al., 1998). K+ channel families thus can be categorized by the numbers of P-loops and TM domains per monomer. Typical examples are the Shaker-type 1P/6TM (Tempel et al., 1987), the 1P/2TM K+ channels (Suzuki et al., 1994), the ORK-like 2P/4TM (Goldstein et al., 1996), and the Tok-like 2P/8TM (Ketchum et al., 1995; see insets in Fig. 2: 1P/6TM and 2P/4TM).

The first K+ channels cloned from Arabidopsis were KAT1 (Anderson et al., 1992) and AKT1 (Sentenac et al., 1992). KAT1 and AKT1 have a 1P/6TM structure (Shaker type; Fig. 2). KAT1 was functionally characterized by heterologous expression in X. laevis oocytes (Schachtman et al., 1992). In contrast to the depolarization-activated Shaker channels, KAT1 and AKT1 were found to be activated by hyper-polarization (“inward-rectifying;” Schachtman et al., 1992; Bertl et al., 1994), with properties similar to the K+in channels described in guard cells (Schroeder et al., 1987) and other cell types. KAT1 and AKT1 have been shown to be expressed in the plasma membrane of plant cells (Ichida et al., 1997; Bei and Luan, 1998; Hirsch et al., 1998). Disruption of the AKT1 K+ channel gene causes reduced K+ uptake into roots from micromolar K+ concentrations when other K+ transporters are blocked by ammonium (Hirsch et al., 1998). In X. laevis oocytes, KAT and AKT K+ channels have been reported to form hetero-oligomers, e.g. AKT1/KAT1 (Dreyer et al., 1997), AKT2/KAT1 (Baizabal-Aguirre et al., 1999), or KAT1/KAT2 (Pilot et al., 2001). However, no AKT1/KAT1 hetero-oligomers were detected when the two channel genes were co-expressed in insect cells (Urbach et al., 2000).

A second class of Arabidopsis Shaker-like (1P/6TM) K+ channels consists of SKOR (Gaymard et al., 1998) and GORK (Ache et al., 2000). These channels are depolarization activated (“outward-rectifying”). Outward-rectifying K+ channels in plant cells have been proposed to mediate long-term K+ efflux and membrane potential regulation (Schroeder et al., 1994). SKOR is expressed in root stelar tissues and is thought to mediate K+ release into the xylem sap (Gaymard et al., 1998). GORK is expressed in guard cells and predicted to mediate K+out currents during stomatal closure (Ache et al., 2000). All of the Arabidopsis Shaker-type K+ channels possess a putative cyclic nucleotide-binding site (see Table I). KAT1-mediated K+ currents were shown to be modulated by cGMP in excised patches of X. laevis oocytes (Hoshi, 1995), which might be related to this consensus site.

Table I.

Arabidopsis K+ channels

| Name | AGI Genome Codes | GenBank Accession No. | Other Names | Predicted Topography | Motifs | Introns |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AKT1 | At2g26650 | AAB95299 | – | 1P/6TM | CNB, AR | 10 |

| AKT2 | At4g22200 | AAA97865 | AKT3 | 1P/6TM | CNB, AR | 9 |

| AKT5 | At4g32500 | CAB79967 | – | 1P/6TM | CNB, AR | 11 |

| AKT6 | At2g25600 | AAD31377 | – | 1P/6TM | CNB, AR | (11) |

| KAT1 | At5g46240 | AAA32824 | – | 1P/6TM | CNB | 8 |

| KAT2 | At4g18290 | CAA16801 | – | 1P/6TM | CNB | (10) |

| KAT3 | At4g32650 | CAB05669 | AKT4, KC1 | 1P/6TM | CNB | 12 |

| SKOR | At3g02850 | CAA11280 | – | 1P/6TM | CNB, AR | 10 |

| GORK | At5g37500 | AAF26975 | – | 1P/6TM | CNB, AR | 11 |

| KCO1 | At5g55630 | BAB09230 | KCO | 2P/4TM | EF | 1 |

| KCO2 | At5g46370 | BAB11092 | KCO | 2P/4TM | EF | 1 |

| KCO3 | At5g46360 | BAB11091 | – | 1P/4TM (?) | EF | 1 |

| KCO4 | At1g02510 | AAG10638 | – | 2P/4TM | – | (1) |

| KCO5 | At4g01840 | CAB80677 | – | 2P/4TM | – | 1 |

| KCO6 | At4g18160 | CAB53657 | – | 2P/4TM | EF | (1) |

The superfamily of Arabidopsis K+ channels, their AGI genome codes and GenBank accession nos., other names found in GenBank, protein consensus motifs, and no. of introns (in parentheses if no full-length cDNA sequence is available). Sequences previously named AKT4 and AtKC1 in GenBank are here named to KAT3 due to the absence of an ankyrin repeat motif. Two sequences, both previously named KCO, here are named KCO1 and KCO2. AKT3 is a truncated but otherwise an identical version of AKT2 (Lacombe et al., 2000). Motif searches were performed with pfscan (http://www.isrec.isb-sib.ch/software/PFSCAN_form.html) against the PROSITE (Hofmann et al., 1999) and Pfam databases (Bateman et al., 2000). P, Pore loop; AR, ankyrin repeat; EF, EF-hand motif.

The outward rectifier KCO1 from Arabidopsis was the first member of the “two-pore” K+ channel superfamily identified from plants (Czempinski et al., 1997). Having four predicted TM domains KCO1 belongs to the 2P/4TM family (Fig. 2). KCO1 also has calcium-binding EF hand motifs and was reported to be activated by elevated cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations when expressed in insect cells (Czempinski et al., 1997).

Searching the Arabidopsis genome we found 15 genes containing conserved K+ channel P-loops, 11 of which are available as full-length cDNA clones (bold lines in Fig. 2). All predicted proteins belong to either the 1P/6TM (Shaker-type) or to the 2P/4TM (ORK-type) family. Other families such as the 1P/2TM or the 2P/8TM channels appear to be absent in Arabidopsis. A non-rooted phylogenetic tree of all 15 proteins reveals two major branches: the 1P/6TM K+ channels and the 2P/4TM K+ channels (Fig. 2). Thus, the channels have segregated according to the number of their P-loops. The only exception is KCO3, which groups to the 2P/4TM K+ channels based on sequence similarity (Fig. 2) as well as gene structure (Table I), but has only one P-loop. Whether KCO3 encodes a functional K+ channel remains to be investigated. The 1P/6TM (Shaker-type) channels are again subdivided into two branches. The first consists of GORK and SKOR, whereas the second harbors AKTs and KATs (Fig. 2). According to previous conventions (Sentenac et al., 1992; Cao et al., 1995) we are using the name AKT for all proteins in the second branch with an ankyrin binding motif, and KAT for those lacking ankyrin domains (Table I). The phylogenetic tree of Arabidopsis K+ channels reflects their structural and functional characteristics. The major boundary is that between the “two-pore” KCOs and the “single-pore” channels; and the latter branch appears to be subdivided into the AKTs and KATs for which several have been demonstrated to show enhanced open probability upon hyperpolarization, and the depolarization-activated SKOR and GORK.

Trk/HKT Transporters

Trk/HKT transporters are reminiscent of K+ channels in that they possess in a single polypeptide chain four domains resembling P-loops (see inset in Fig. 1; Durell and Guy, 1999). These P-loop-like domains are only weakly conserved to K+ channel P loops. The high-affinity K+ transporters Trk1 (Gaber et al., 1988) and Trk2 (Ramos et al., 1994) from yeast share 49% similarity on the level of amino acids with each other, and 17% and 28%, respectively, with HKT1 from wheat (Schachtman and Schroeder, 1994). Wheat HKT1 was shown to function as a high-affinity Na+/K+ cotransporter when expressed in yeast and in X. laevis oocytes (Rubio et al., 1995), which correlates to high-affinity Na+-coupled K+ uptake found in aquatic plants (Maathuis et al., 1996). In wheat, Na+/K+ cotransport is likely to contribute a minor portion to K+ uptake into roots.

Ion selectivity mutants in HKT1 were genetically selected and showed reduced Na+ uptake. These mutants carried point mutations in predicted P-loop-like domains of HKT1 (Rubio et al., 1995, 1999). This finding supports the structural model suggesting that Trk/HKT transporters have cation selectivity filter P-loops that are related to K+ channels.

The Trk/HKT family is represented by a single member in Arabidopsis, AtHKT1 (Fig. 1). It is interesting that AtHKT1 does not transport K+ but Na+ when expressed in yeast and in X. laevis oocytes (Uozumi et al., 2000). Therefore, AtHKT1 might function in Na+ transport in Arabidopsis, and plant Trk/HKT genes have been proposed to contribute to Na+ transport and sensitivity in plants (Rubio et al., 1995; Golldack et al., 1997; Uozumi et al., 2000).

KUP/HAK/KT Transporters

Bacterial K+ uptake permeases named KUPs (Schleyer and Bakker, 1993) and fungal high-affinity K+ transporters named HAKs (Banuelos et al., 1995) form an additional family of K+ transporters that was identified independently by several laboratories in plants. The plant genes were named AtKT (Quintero and Blatt, 1997), AtHAK (Santa-Maria et al., 1997; Rubio et al., 2000), or AtKUP (Fu and Luan, 1998; Kim et al., 1998). Here, we name the Arabidopsis members of this transporter family AtKUP/HAK/KT (unless conflicting GenBank-deposited gene nos. would cause ambiguity; see Fig. 3). The transporters alternatively could be named AtPOT1 through AtPOT13 (potassium transporter) using the corresponding numbering of the published names shown in Figure 3 (special cases: AtKT3/AtKUP4/TRH1 named AtPOT3/TRH1; AtKT4/AtKUP3 named AtPOT4; AtHAK5 named AtPOT5; and AtKT5/KUP5 named AtPOT13). The 13 AtKUP/HAK/KTs form the tightest and most distinct branch in the phylogenetic tree of Arabidopsis K+ transporters (Figs. 1 and 3), reflecting the high degree of similarity within those genes. For instance, AtKUP/HAK/KT10 (AtPOT10) and AtKUP/HAK/KT11 (AtPOT11) share 89% homology at amino acid level (Fig. 3). There appear to be no major subfamily branches within the AtKUP/HAK/KTs (Fig. 3). However, prediction of coding sequences is dependent on full-length cDNA sequences, which are only available for AtKUP/HAK/KT1 (AtPOT1), AtKUP/HAK/KT2 (AtPOT2), AtKT3 = AtKUP4 (ATPOT3/TRH1), AtKT4 = AtKUP3 (AtPOT4), and AtHAK5 (AtPOT5; bold lines in Fig. 3). For the remaining transporters, amino acid sequences were predicted based on partial cDNA sequences and gene structure analysis programs. These sequences might contain errors, because the programs tested (Grail, GeneFinder, and NetGene2) did not accurately predict the splicing of known AtKUP/HAK/KT open reading frames (ORFs).

Knowledge on the function of KUP/HAK/KTs remains limited. K+ transport was experimentally demonstrated for AtKUP/HAK/TK1 (AtPOT1) in Escherichia coli and transgenic plant cells (Kim et al., 1998), and for AtKUP/HAK/KT2 (AtPOT2; Quintero and Blatt, 1997), AtKUP/HAK/KT1 (AtPOT1; Fu and Luan, 1998), and AtKT3 = AtKUP4 (AtPOT3/TRH1; Rigas et al., 2001) in yeast. In other reports, AtKUP/HAK/KT1 did not function in yeast (Quintero and Blatt, 1997; Kim et al., 1998). It is important that high-affinity K+ transport mediated by the barley (Hordeum vulgare) homolog HvHAK1 (HvPOT1) in yeast was blocked by ammonium, which correlates to block of K+ uptake in plants (Santa-Maria et al., 1997). Given the size of the AtKUP/HAK/TK gene family it is possible that expression of particular members is confined to specific tissues, cells, or organellar membranes, or that they are only expressed under specific conditions. Expression of AtKT4 = AtKUP3 (AtPOT4) in roots is induced by K+ starvation (Kim et al., 1998). Disruption of another family member, AtKT3 = AtKUP4 (AtPOT3/TRH1), abolishes root hair elongation, resulting in a “tiny root hair” (trh1) phenotype, illustrating the importance of these transporters in development and cell elongation (Rigas et al., 2001). The semidominant shy3-1 mutation causes a short hypocotyl and small leaves (Reed et al., 1998), and changes one amino acid in AtKUP/HAK/KT2 (ATPOT2; J. Reed, personal communication). Null mutations in AtKUP/HAK/KT2 do not have a short hypocotyl, suggesting that shy3-1 is an interfering or gain-of-function allele. Determination of the membrane localization of individual AtKUP/HAK/KT (AtPOT) transporters will be important for determining their physiological functions.

K+/H+ Antiporter Homologs

K+/H+ antiporters have first been described from gram-negative bacteria, where they are gated by glutathione-S conjugates and inactivated by glutathione. These antiporters provide a means for acidification of the cytosol as a defense to toxic electrophiles such as methylglyoxal (Munro et al., 1991). The Arabidopsis genome contains six putative K+ efflux antiporters (Fig. 1), herein named KEA1 through KEA6; a cDNA sequence is available only for KEA1 (GenBank accession no. AF003382; W. Yao, N. Hadjeb, and G.A. Berkowitz, unpublished data). The KEAs belong to the monovalent cation:proton antiporter family 2 (CPA2 family). See Figure 4 for a phylogenetic tree of all Arabidopsis H+-coupled antiporters. None of the plant KEAs has been experimentally characterized. In principal, they could also sequester K+ into acidic compartments. For example, vacuolar K+ loading is mediated by H+/K+ exchange and is driven by the vacuolar proton pumps. Therefore, elucidation of the subcellular localization of the KEAs will be pivotal to the understanding of their physiological roles.

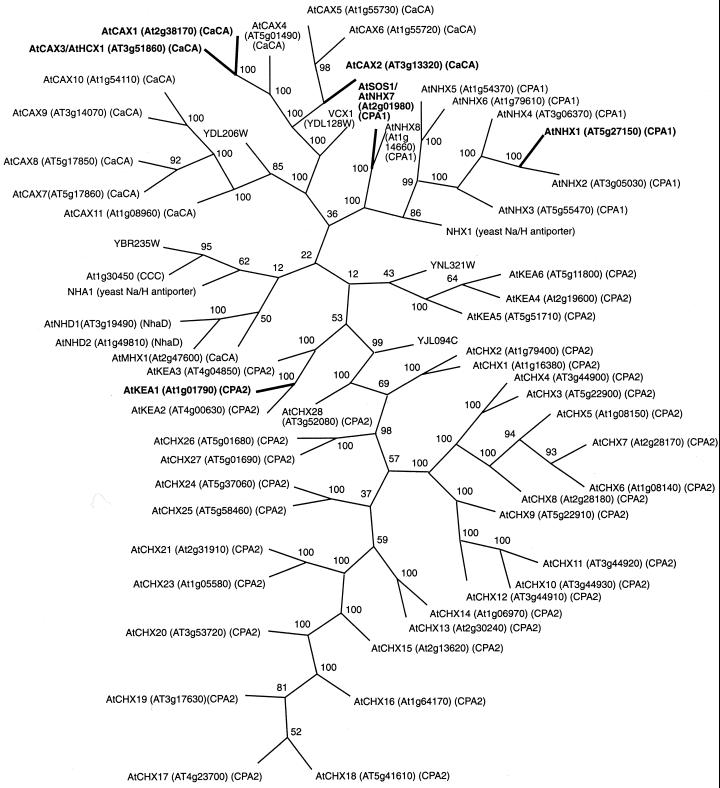

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic tree of Arabidopsis cation antiporters. Members of the families CPA1, CPA2, CaCA, NhaD, and CCC are presented (http://www.biology.ucsd.edu/∼ipaulsen/transport/) with homologous protein sequences from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene names, accession nos., and family assignment are shown for each Arabidopsis sequence. Alignments of full-length sequences were performed using ClustalW (Thompson et al., 1994). The tree was constructed using the neighbor joining function of Paup 4.0 (Swofford, 1998). Values indicate the number of times (in percent) that each branch topology was found during bootstrap analysis.

Cation/H+ Antiporter Family

Most cations are transported against their electrochemical gradient using proton-coupled transporters rather than primary ion pumps. With proton pumps at the PM and endomembranes of plant cells, we can predict that cation/proton antiporters extrude cations from the cytosol to the outside across the PM or into intracellular compartments, including the vacuole (Sze et al., 1999). The best examples of these are cotransporters that extrude Ca2+ and Na+ from the cytosol to maintain low cytosolic concentrations. At the vacuole membrane, Ca2+/H+ and Na+/H+ antiporters transport Ca2+ and Na+, respectively, into the vacuole. The properties of Ca2+/H+ transporters have been well characterized through biochemical analysis (Blumwald and Poole, 1985; Schumaker and Sze, 1986) In addition, similar transport activities are present in the plasma membrane and the chloroplast thylakoid (Ettinger et al., 1999; Sanders et al., 1999; Blumwald et al., 2000). Ca2+/H+ and Na+/H+ antiporter cDNAs have been isolated from plants (Gaxiola et al., 1999; Hirschi, 2001); however, the completion of the Arabidopsis genome indicates that a large number of homologs to these transporters (Fig. 4; Table II) exist within the CaCA and CPA families (http://www.biology.ucsd.edu/∼ipaulsen/transport/). The predicted proteins in general have 10 to 14 TM domains with about 400 to <900 residues. Yet, the substrate specificity, regulation, and membrane localization of these antiporters cannot be predicted with certainty from phylogenetic relationships. Therefore, the functional characterization of these large families is only beginning.

Table II.

Selected cation/proton antiporters found in Arabidopsis

| Family | Gene Name | AGI Genome Codes | Residues | Topology | Substrate | Cellular Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CaCA | CAX1 | At2g38170 | 459 | 9–11 TM | Ca2+/H+ | EM |

| CAX2 | At3g13320 | 439 | 7–11 TM | Cd2+, Ca2+, Mn2+/H+ | VM | |

| CAX3/HCX1 | At3g51860 | 448 | 8–10 TM | – | ? | |

| CAX7 | At5g17860 | 570 | 9–15 TM | – | ? | |

| MHX1 | At2g47600 | 539 | 10 TM | Mg2+, Zn2+/H+ | VM | |

| CPA1 | NHX1 | At5g27150 | 538 | 12 TM | Na+/H+ | VM |

| SOS1/NHX7 | At2g01980 | 1,162 | 12 TM | Na+/H+ | VM | |

| NHX8 | At1g14660 | 697 | 9 TM | – | PM? | |

| CPA2 | CHX6 | At1g08140 | 1,536 | 24 TM | – | – |

| CHX7 | At2g28170 | 617 | 12 TM | – | – | |

| CHX17 | At4g23700 | 820 | 10–13 TM | – | – | |

| CHX23 | At1g05580 | 1,193 | 12 TM | – | – | |

| KEA1 | At1g01790 | 618 | 10 TM | K+/H+ | – | |

| NhaD | NHD2 | At1g49810 | 420 | 6–10 TM | – | – |

EM, Endomembrane; VM, vacuolar membrane; PM, plasma membrane.

Yeast has been an excellent model system for studying plant vacuolar antiporters for Ca2+ and Na+; thus, homologous proteins or ORFs from yeast are included in Figure 4 (Sze et al., 2000). Molecular and biochemical studies have shown that high-capacity H+ exchange activity in yeast is important for Na+ and Ca+ homeostasis (Cunningham and Fink, 1996; Nass et al., 1997). In yeast, NHX1, a vacuolar Na+/H+ exchanger, is required for vacuolar Na+ sequestration and contributes to Na+ tolerance in certain strains. Another yeast Na+/H+ antiporter, NHA1, appears to function in Na+ transport across the plasma membrane. The yeast genome sequencing project has identified a third ORF, YJL094C similar to Na+/H+ exchangers from Enterococcus hirae, as well as Lactococcus lactis. The function of this ORF in Na+ or K+ homeostasis is currently unknown. In yeast, vacuolar H+/Ca2+ exchange is accomplished by VCX1, a member of the CaCA gene family. It is interesting that a single point mutation in this gene causes increased manganese transport (Del Poza et al., 1999). This type of observation underscores how difficult it is to determine transport properties from primary sequence information. That said, there are three other CaCA genes in the yeast genome whose function in ion homeostasis is unknown.

Two plant H+/Ca2+ exchangers were cloned from Arabidopsis by suppression of yeast mutants defective in vacuolar Ca2+ transport (Hirschi, 2001). These genes have been termed CAX1 and CAX2 for calcium exchangers. At the deduced amino acid level, these gene products are 47% identical and are both similar to VCX1; however, they appear to have different ion specificities. Transgenic tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) plants expressing the Arabidopsis CAX1 gene display altered calcium levels and are perturbed in stress responses (Hirschi, 2001). Transgenic tobacco plants expressing CAX2 accumulate cadmium, calcium, and manganese ions and have increased tolerance to Mn2+ stress. An additional CAX homolog recently was cloned from Arabidopsis. The protein is 77% identical to CAX1, and the gene has been tentatively termed AtHCX1 [= CAX3] for Arabidopsis homolog of CAX1. Unlike CAX1 and CAX2, this gene fails to suppress yeast mutants defective in vacuolar Ca2+ transport. There are four other closely related CAX homologs and there are a total of 12 CaCA family members in Arabidopsis (Fig. 4). Given the potentially diverse function and localization of these 12 CaCA gene products, we propose that in the future “CAX” should serve as the standard abbreviation for cation exchanger.

The Arabidopsis vacuolar Na+/H+ antiporter AtNHX1 (538 residues) was identified by its similarity to the yeast vacuolar antiporter NHX1 (633 residues; Gaxiola et al., 1999; Quintero et al., 2000). Ectopic expression of this gene causes dramatic salt tolerance in Arabidopsis plants (Apse et al., 1999). AtNHX1 is localized to plant vacuoles and is expressed in all plant organs. Its role as an Na+/H+ antiporter was demonstrated by Na+ dissipation of a pH gradient (acid inside) in vacuoles from plants overexpressing AtNHX1. An Arabidopsis NHA1 homolog, SOS1 is a putative plasma membrane Na+/H+ antiporter (Zhu, 2001). The predicted SOS1 protein of 1,162 residues (127 kD) is larger than most cation/proton antiporters because it has 12 TM domains in the N-terminal half and a long C-terminal cytoplasmic tail. Arabidopsis mutants of sos1 are salt sensitive; furthermore, ectopic expression of the gene causes salt tolerance in Arabidopsis. These findings certainly pique enthusiasm in elucidating the function of other putative Na+ transporters in Arabidopsis (Zhu, 2000).

It is surprising that more than 40 genes encode homologs of Na+/H+ antiporters in Arabidopsis. Given that Na+ is not an essential nutrient for plants, we need to consider that these homologs may have other functions in plants. An informative example is the characterization of AtMHX1, which was cloned via homology to mammalian Na+/Ca2+ exchangers (Shaul et al., 1999). This gene encodes an H+-coupled antiporter that transports Mg2+ and Zn2+ into plant vacuoles. It is interesting that AtMHX1 is expressed in the vascular tissue. In Arabidopsis, there are eight members of the CPA1 subfamily, including AtNHX1, and SOS1/AtNHX7 (Zhu, 2001). The CPA2 subfamily with 33 members includes five homologs of a K+/H+ antiporter, AtKEA1. In addition, there are two members of the NhaD family (Na+/H+ antiporter), previously only found in bacteria and one member of the CCC family (NaCl and/or KCl symport; Fig. 4). Most of the gene products in the CPA2 family have not been characterized; thus, we have named them CHX# for cation/H+ exchangers. Because K+ is the major osmoticum in the cytosol and the vacuole, it is likely that the CHXs transport monovalent and divalent cations with varying specificities. For instance, K+/H+ antiport is needed to move K+ into the vacuole against an electrical gradient (positive inside +25 mV). Furthermore, active extrusion of cations from the xylem parenchyma into xylem vessels could depend on H+-coupled antiporters at the plasma membrane, or exocytosis of small “vacuoles” loaded with ions. Several of the CAX and CHX homologs contain organellar-targeting sequences, consistent with the idea that cation cotransporters are also localized in mitochondria and chloroplasts.

CNGC Transporter Family

A family of CNGCs, first discovered in barley (Schuurink et al., 1998), is characterized by the presence at the C terminus of both cyclic nucleotide and calmodulin binding domains. Membrane-associated domains strongly resemble those of the Shaker super-families, of which the KAT and AKT families are a part. Biochemical studies with a CNGC orthologue from tobacco and CNGC1 from Arabidopsis have elegantly demonstrated that the cyclic nucleotide-binding domain overlaps with that of calmodulin (Arazi et al., 2000; Köhler and Neuhaus, 2000), thereby suggesting that cyclic nucleotides and calmodulin interact in regulation of channel activity.

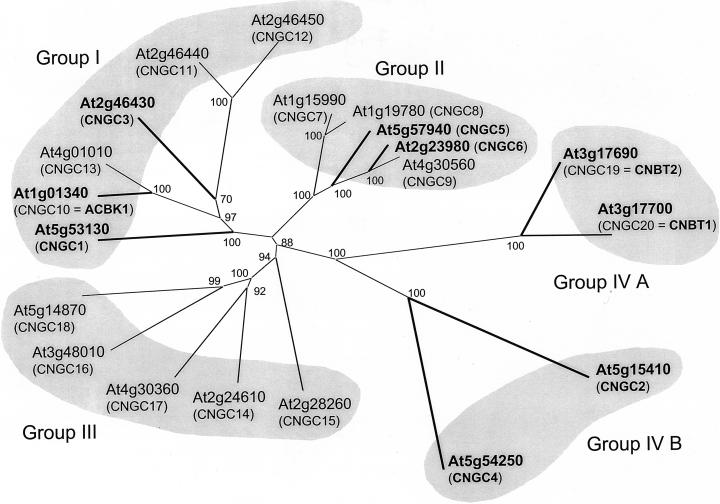

The CNGC gene family of Arabidopsis comprises 20 members with overall sequence similarities ranging between 55% and 83%. Alignment of the predicted amino acid sequences results in the tree shown in Figure 5. According to this tree, CNGCs can be divided into four groups, each of them containing between four and six genes. Whereas groups I, II, and III are closely related, group IV genes are more distantly related to the other CNGCs as well as to each other. Within group IV, two subgroups can be distinguished, each of them containing two genes (CNBT1 and CNBT2 in group IVA and CNGC4 and CNGC2 in group IVB). We evaluated the relevance of this group assignment, which was based on comparing entire sequences, by creating trees for two functional domains within the CNGC sequences. Alignment of the putative P-region resulted in identical grouping of the genes, but group IVA and IVB genes were situated even further away from the other groups as well as from each other. A similar result was obtained when comparing putative calmodulin-binding domains (CaMDs). Here, a clear distinction between groups I, II, and III is no longer apparent. However, the CaMD of one group I gene (At2g46450) has very low homology to CaMDs of other CNGCs. This is particularly interesting because At2g46450 is the last gene within a tandem arrangement of three CNGC genes on chromosome 2 (At2g46430, At2g46440, and At2g46450). Other CNGCs have also been subjects of gene duplication events. Group IVA genes At3g1769 and At3g1770 are in tandem arrangement on chromosome 3. Inter-chromosome duplication between chromosomes 2 and 4 was found for At2g23980 and At4g30560 (group II) and between chromosomes 1 and 4 for At1g01340 and At4g01010. A co-alignment of the Arabidopsis CNGC family with CNGCs from tobacco (NtCBP4 and NtCBP7; Arazi et al., 1999) and barley (HvCBT1; Schuurink et al., 1998) shows that these protein sequences are closely related to At5g53130 (group I), suggesting that they share a common ancestor.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic tree of the Arabidopsis CNGC transporters. Entries in the Munich Information Center for Protein Sequences Arabidopsis database (MATDB) were compared with available corresponding cDNA entries in the National Center for Biotechnology Information database, to minimize errors for each predicted protein sequence. By default, the MATDB predicted protein sequences were used for final alignment. Exceptions are: accession no. AAF97331.1 for At1g01340, accession no. CAB40128.1 for At2g46430, accession no. AAF73129.1 for At3g17690, and accession no. AAF73128.1 for At3g17700. Bold lines indicate that protein sequences predicted from cDNAs are available. Final protein alignment, tree drawing, and bootstrap analysis were done with ClustalX (Higgins and Sharp, 1988), and the tree was drawn using Treeview. CNGCs 1 through 6 have already been named in the literature (Köhler et al., 1999). To generate a uniform nomenclature, ACBK1, CNBT1, and CNBT2 are assigned the names CNGC10, 20, and 19, respectively, and the remaining genes are also assigned systematic names. Values indicate the number of times (in percent) that each branch topology was found during bootstrap analysis.

Functional heterologous expression of CNGCs has so far been difficult to achieve. Phenotypic characterization of K+ uptake-deficient yeast expressing various CNGCs has suggested that some family members might form K+-permeable channels (Köhler et al., 1999; Leng et al., 1999), and these findings are supported by work with CNGC2, which, when expressed in X. laevis oocytes, appears to form K+-permeable channels (Leng et al., 1999). An Arabidopsis mutant in pathogen defense responses was found to have a mutation in CNGC2 (Clough et al., 2000). In addition, a knockout mutant in CNGC1 has been identified which shows a Pb2+-resistant phenotype (Sunkar et al., 2000), in accord with the possibility that CNGCs are permeable to divalent cations. Two complications emerge in studies of CNGCs. First, the existence of an extensive gene family raises the possibility that redundancy will preclude accurate functional characterization using reverse genetic approaches. Second, in mammalian systems, CNGC isoforms have been shown to be differentially capable of generating functional ion channels when expressed heterologously (Finn et al., 1996). These findings must be viewed against the notion that functional channels are probably tetrameric (Finn et al., 1996). Thus, some isoforms are competent in forming channels when expressed alone, whereas hetero-oligomeric expression is required for functioning of other isoforms.

CDF Metal Transporter Family

The CDF family, first identified by Nies and Silver (1995), is a diverse family with members occurring in bacteria, fungi, plants, and animals. All of these proteins have six putative TM domains and a signature N-terminal amino acid sequence (Paulsen and Saier, 1997). These proteins also share a characteristic C-terminal cation efflux domain (Pfam 01545). Eukaryotic family members also contain a His-rich region between TM domains four and five, which is predicted to be within the cytoplasm (Paulsen and Saier, 1997). The significance of this His-rich region is not known. However, changes in this region in CDF family members identified from the Ni hyperaccumulator Thlaspi goesingense appear to affect metal specificity, suggesting these sequences may be involved in metal binding (M.W. Persans, K. Nieman, and D.E. Salt, unpublished data). Because of the lack of basic information about the energetics of the CDF transporters, and the known efflux function of the characterized family members, we propose that a more accurate name for the family is the cation efflux family (CE), as used to classify these proteins in the Pfam protein domain database (http://pfam.wustl.edu/). Therefore, throughout the rest of this discussion, we will refer to the CDF family as the CE family.

Several eukaryotic members of the CE family have been functionally characterized. The plasma membrane-localized ZnT1 protein from mammals is known to efflux Zn from rat cells (Palmiter and Findley, 1995). ZnT2 is very similar to ZnT1 in that it has six membrane-spanning domains, an intracellular His-rich loop, and a long C-terminal tail (Palmiter et al., 1996). However, unlike ZnT1, which is localized to the plasma membrane, ZnT2 is localized in intracellular vesicular membranes and is involved in the sequestration of Zn into these vesicles. Another ZnT homolog, ZnT3 is localized to synaptic vesicles, and it is proposed that ZnT3 pumps Zn into synaptic vesicles as a storage pool of Zn to be released upon excitation of the neuron (Wenzel et al., 1997). A fourth ZnT homolog (ZnT4) has also been isolated from mice that are defective in Zn transport into milk (Huang and Gitschier, 1997). This ZnT4 transporter is responsible for effluxing Zn from the mammary cells into the milk, and it is expressed at high levels in mammary tissue. Therefore, all the ZnT family members are involved in effluxing Zn out of cells or into intracellular compartments. Two related proteins, COT1 (Conklin et al., 1992) and ZRC1 (Conklin et al., 1994), have been characterized in yeast. These genes share the six putative membrane-spanning domains of the ZnT genes and the His-rich region. COT1 is involved in Co resistance, whereas ZRC1 is involved in Zn and Cd resistance. Yeast deletion mutants of either gene show increased sensitivity to Co (COT1 deletion), or Zn and Cd (ZRC1 deletion) and overexpression in yeast leads to increased resistance to Co and Zn. COT1 and ZRC1 are localized to the yeast vacuolar membrane (Li and Kaplan, 1998), suggesting these proteins are involved in effluxing Co, Zn, and Cd into the vacuole.

A plant member of the CE family recently was characterized in Arabidopsis (Van der Zaal et al., 1999), and designated Zinc transporter of Arabidopsis (ZAT). As the other proteins described previously, ZAT has six putative TM domains and a His-rich region between the predicted TM spanning helices 4 and 5. This represents the first full-length CE family member to be identified and shown to be involved in heavy metal tolerance in plants. Although ZAT holds prior authority, to allow for expansion of the CE family in Arabidopsis and plants in general we propose that metal tolerance protein (MTP) would be a better base name for ZAT-related proteins. Under such a system, ZAT would be renamed AtMTP1, with the two-letter prefix identifying the species. Closely related proteins would be named AtMTPn (where n > 1), and more distantly related proteins would be named AtMTPx (where x = a–z). Such a system would allow for more systematic naming as the plant CE family expands. This nomenclature would also be more applicable to naming future plant CE family members that may have different metal transport characteristics compared with ZAT.

A search of the completed Arabidopsis genome reveals the existence of eight genes (Table III) encoding proteins with homology to members of the CE family. ZAT (AT2g46800 or AtMTP1) is located on chromosome II, AtMTPa1 (AT3g61940) and AtMTPa2 (AT3g58810) on chromosome III, AtMTPb (At2g29410) on chromosome II, AtMTPc1 (At2g47830) on chromosome II, AtMTPc2 (At3g12100) and AtMTPc3 (At3g58060) on chromosome III, and AtMTPc4 (At1g51610) on chromosome I. ESTs are available for ZAT (AtMTP1; gi nos. 2763071, 8691041, 8720027, 8720035, and 5842768), AtMTPc1 (gi nos. 906769, 2749524, 5841145, and 8683092), AtMTPc2 (gi no. 5844377) and numerous other CE family members from Medicago truncatula, Glycine max, Lycopersicon esculentum, Sorghum bicolor, Brassica campestris, rice (Oryza sativa), barley, Triticum aestivum, and maize (Zea mays).

Table III.

Full-length ORFs and cDNA sequences of plant cation efflux family members

| Species | Gene Name | EST's GenBank gi No. | GenBank gi No. | AGI Genome Codes | Introns | Motif |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis | AtMTPc1 | 906769, 2749524, 5841145, 8683092 | 3738295 | At2g47830 | (11) | CE, CSS, 5-TM |

| Arabidopsis | AtMTPc2 | 5844377 | 10092478 | At3g12100 | (8) | CE, PSS, 5-TM |

| Arabidopsis | AtMTPc3 | na | 6729549 | At3g58060 | (6) | CE, PSS, 4-TM |

| Arabidopsis | AtMTPc4 | na | 10092347 | At1g51610 | (11) | PSS, 5-TM |

| Arabidopsis | AtMTPb1 | na | 3980394 | At2g29410 | (0) | CE, CSS, 6-TM, HRR |

| Arabidopsis | AtMTPa2 | na | 7630076 | At3g58810 | (0) | CE, CSS, 6-TM, HRR |

| Arabidopsis | AtMTPa1 | na | 6899892 | At3g61940 | (0) | CE, CSS, 6-TM, HRR |

| Arabidopsis | ZAT (AtMTP1) | 2763071, 8691041, 8720027, 8720035, 5842768 | 4206640 | At2g46800 | 0 | CE, CSS, 6-TM, HRR |

| 2Thlaspi montanum var fendlerib | TmMTP1a | na | 1 | na | (0) | CE, CSS, 6-TM, HRR |

| 2T. goesingenseb | TgMTP3a | na | 1 | na | 0 | CE, CSS, 6-TM, HRR |

| 2T. goesingenseb | TgMTP2a | na | 1 | na | na | CE, CSS, 6-TM, HRR |

| 2T. goesingenseb | TgMTP1a | na | 1 | na | na | CE, CSS, 6-TM, HRR |

| Brassica juncea | BiMTP1a | na | 1 | na | (0) | CE, CSS, 6-TM, HRR |

| Thlaspi arvense | TaMTP1a | na | 1 | na | (0) | CE, CSS, 6-TM, HRR |

Genes in bold sequence derived from cDNAs. No. of introns in parentheses not confirmed from cDNAs. CE, C-terminal Cation Efflux motif (Pfam 01545, http://pfam.wustl.edu/); CSS, conserved N-terminal signature sequence SX(ASG)(LIVMT)2(SAT)(DA)(SGAL)(LIVFYA)(HDH)X3D (Paulsen and Saier, 1997); PSS, partial N-terminal signature sequence; TM (TMpred; http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/TMPRED_form.html); HRR, cytoplasmic His-rich region between transmembrane regions 4 and 5; na, not available.

M.W. Persans, K. Nieman, and D.E. Salt, unpublished data.

Metal hyperaccumulator plants.

Comparison of the genomic, cDNA, and EST sequences of ZAT (AtMTP1) reveals that this gene contains no introns (Table III). This analysis also revealed an error in the reported cDNA sequence of ZAT (Van der Zaal et al., 1999). Insertion of an extra C after nucleotide 769 and deletion of a C after nucleotide 793 leads to a short frame shift, producing the amino acid sequence (187)-PQSWTWAW-(194) instead of (187)-HSHGHGHG-(194). It is unknown whether this is a sequencing error or the cDNA actually contains this incorrect sequence. The AtMTPa1, AtMTPa2, and AtMTPb genes also appear to contain no introns (Table III). However, the more distantly related AtMTPc1, AtMTPc2, AtMTPc3, and AtMTPc4 genes contain between six and 11 predicted introns (Table III).

Based on the presence of the N-terminal signature sequence SX(ASG)(LIVMT)2(SAT) (DA)(SGAL)(LIVFYA)(HDH) X3D (Paulsen and Saier, 1997), the C-terminal cation efflux domain, and the six conserved TM domains (Paulsen and Saier, 1997), these sequences were confirmed to be members of the CE family. The Arabidopsis CE family members appear to cluster into four subfamilies: groups I, II, III, and IV (Fig. 6), with the group I, II, and III subfamilies being more closely related to the yeast CE family members COT1 and ZRC1 than to the group IV subfamily (Fig. 6). All members of the group I, II, and III subfamilies contain a fully conserved N-terminal signature sequence, a C-terminal cation efflux domain, and six TM domains. For comparison, the yeast CE family members COT1 and ZRC1 also show all these features. However, only subsets of these features are present in the group IV subfamily, demonstrating its more distant relationship to the other subfamilies. None of the group IV subfamily members show the characteristic six TM domains. Only AtMTPc1 contains both a fully conserved N-terminal signature sequence and a recognizable C-terminal cation efflux domain. AtMTPc2, AtMTPc3, and AtMTPc4 only show weak conservation of the N-terminal signature sequence and only AtMTPc2 and AtMTPc3 contain a recognizable C-terminal cation efflux domain.

Figure 6.

Phylogenetic tree of plant CDF transporters. The phylogenetic tree of the CE protein family was drawn using PHYLIP (Felsenstein, 1989) after alignment of the sequences with CLUSTAL W (Thompson et al., 1994). For ZAT (AtMTP1; At2g46800), TgMTP1, TgMTP2, TgMTP3, TmMTP1, TaMTP1, BjMTP1, and the yeast sequences ZRC1 (gi no. 736309) and COT1 (gi no. 171263), the protein sequences were predicted from cDNAs, and these branches of the tree are in bold. For AtMTPa1 (At3g61940), AtMTPa2 (At3g58810), AtMTPb (At2g29410), AtMTPc1 (At2g47830), AtMTPc2 (At3g12100), AtMTPc3 (At3g58060), and AtMTPc4 (At1g51610) protein sequences were translated from the ORFs predicted from genomic sequences, and these branches are represented by thin lines. Values indicate the number of times (in percent) that each branch topology was found during bootstrap analysis.

We also include in the Arabidopsis CE family tree recently sequenced genes encoding CE family members from T. goesingense (TgMTP1, TgMTP2, and TgMTP3), T. montanum var fendleri (TmMTP1), T. arvense (TaMTP1), and B. juncea (BjMTP1; Table III; Fig. 6). All these members cluster with ZAT (AtMTP1) in the group I subfamily, and also contain no introns. It is interesting that we note that the CE family members from the metal-hyperaccumulating Thlaspi spp. (T. goesingense and T. montanum) appear to cluster as a separate subgroup within the group I subfamily. Whereas the TaMTP1 protein from the nonaccumulator Thlaspi spp., T. arvense clusters with the CE family members from other nonaccumulator species, including B. juncea and Arabidopsis.

Functional data on the plant MTP proteins is limited; however, a role in metal tolerance has been demonstrated both in planta and by heterologous expression in yeast. Overexpression of ZAT (AtMTP1) conferred increased Zn resistance and root Zn accumulation in Arabidopsis (Van der Zaal et al., 1999). This suggests a role for ZAT (AtMTP1) in Zn homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Yeast strains deficient in COT1 or ZRC1 and proteins involved in vacuolar sequestration of heavy metals (Li and Kaplan, 1998) are Co, Zn, and Cd sensitive (Conklin et al., 1992, 1994). In such yeast, expression of the COT1 and ZRC1 homologs TgMTP1, TgMTP2, and TgMTP3 complements the mutant metal-sensitive phenotype, imparting increased resistance to Cd2+, Co2+, Ni2+, and Zn2+ (M.W. Persans, K. Nieman, and D.E. Salt, unpublished data). Complementation of yeast strains deficient in vacuolar metal sequestration by the TgMTP proteins suggests that these proteins play a role in the vacuolar sequestration of metals in planta. Based on northern and EST analysis, expression of ZAT (AtMTP1) occurs in whole seedlings, flower buds, inflorescence, and root tissue. However, the steady-state levels of ZAT (AtMTP1) mRNA in Arabidopsis seedlings are not regulated in response to elevated concentration of Zn (Van der Zaal et al., 1999). Steady-state levels of TgMTP's mRNA are also unregulated by Ni exposure (Persans et al., 2001). Based on the analysis of ESTs, expression of CE family members in various other species is also found in numerous tissues including the cotyledons, root, shoot, flowers, and fruit.

To further understand the role of the CE family in heavy metal homeostasis in plants a more detailed analysis of the different members is required. This analysis should include determination of the proteins expression patterns, membrane localization, metal specificity, and transport mechanisms, including structure/function analyses.

NRAMP Metal Transporter Family

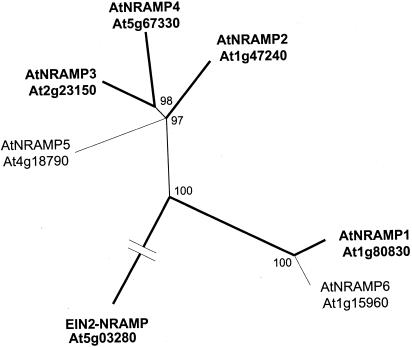

Genes encoding members of the NRAMP family of integral membrane proteins have been identified in bacteria, fungi, plants, and animals. Scanning through the completed Arabidopsis genome sequence, we find six genes encoding proteins with high homology to NRAMPs (Fig. 7). AtNRAMP1, 2, and 6 are located on chromosome I (AC01713, 10092406, and AC010924), AtNRAMP3 on chromosome II (AC002391), AtNRAMP5 on chromosome IV (AL035526), and AtNRAMP4 on chromosome V (AB007645). ESTs are also available for three of these genes: AtNRAMP1 (Z30530, AI998720, T04467, Z32611, and AA585940), AtNRAMP2 (N38346), AtNRAMP3 (AV563322), and AtNRAMP4 (AV551675 and AI618748). Many additional ESTs indicate that genes from the NRAMP family are present in other dicots (Gossypium hirsutum, Lycopersicon esculentum, G. max, and M. truncatula) and in monocots (rice and maize). The proteins encoded by AtNRAMP genes cluster in two subfamilies: one including AtNRAMP1 and 6 and the other including AtNRAMP2 through 5 (Fig. 7). In addition, the ethylene insensitivity gene EIN2 that functions in transduction of multiple stress signals contains an NRAMP homologous domain but its homology with other members of the NRAMP family is much lower (Alonso et al., 1999).

Figure 7.

Phylogenetic tree of Arabidopsis NRAMP transporters. The phylogenetic tree of AtNRAMP protein sequences was drawn using Treeview program after alignment of the sequences with ClustalX program. For AtNRAMP1, 2, 3, 4, and EIN2 protein sequences predicted from cDNA translation were used (AAF36535, AAD41078, AAF13278, AAF13279, and AAD41077, bold lines). For AtNRAMP5 and 6, protein sequences translated from the ORFs predicted from genomic sequences (CAB37464 and AAF18493, thin lines) were used because cDNA sequences are not available for these genes. Note that for EIN2, only the sequence of the NRAMP homologous domain of the protein was taken into account to construct the tree. Values indicate the number of times (in percent) that each branch topology was found during bootstrap analysis.

NRAMP genes originally were identified through very diverse genetic screens: mouse NRAMP1 determines sensitivity to bacteria and led to the gene family name, NRAMP (natural resistance-associated macrophage protein; Cellier et al., 1995). It was shown later that the yeast NRAMP homologs SMFs and DCT1/Nramp2 in mammals can mediate the uptake of a broad range of metals (Supek et al., 1996; Gunshin et al., 1997; Chen et al., 1999). cDNAs corresponding to Arabidopsis NRAMP1, 2, 3, and 4 genes have been cloned (Fig. 7, bold lines).

The functions of AtNRAMP proteins in metal transport have been demonstrated both in the heterologous yeast expression system and in planta (Alonso et al., 1999; Curie et al., 2000; Thomine et al., 2000). Yeast strains that are deficient in iron and manganese uptake (Eide et al., 1996; Supek et al., 1996) were analyzed. In yeast, expression of AtNRAMP1, 3, and 4 can complement the phenotype of yeast strains deficient for manganese or iron uptake (Curie et al., 2000; Thomine et al., 2000). In contrast, expression of EIN2 does not complement those phenotypes (Alonso et al., 1999; Thomine et al., 2000). In addition, expression of AtNRAMP1, 3, and 4 in yeast increases their Cd2+ sensitivity and Cd2+ accumulation (Thomine et al., 2000). This indicates that these AtNRAMP genes encode multispecific metal transporters. In Arabidopsis, AtNRAMP1, 2, 3, and 4 are expressed both in roots and aerial parts. In Arabidopsis roots, AtNRAMP1, 3, and 4 mRNA levels are up-regulated under Fe starvation (Curie et al., 2000; Thomine et al., 2000). The observations that AtNRAMP3 overexpressing plants can accumulate higher levels of Fe, upon Cd2+ treatment (Thomine et al., 2000) and that AtNRAMP1 overexpressing plants confer resistance to toxic levels of Fe (Curie et al., 2000) provide further evidence for a role of AtNRAMPs in Fe transport in planta. The cellular and subcellular/membrane expression patterns of AtNRAMP transporters has not yet been analyzed and possible roles in organellar transport have been discussed (Thomine et al., 2000). Data on AtNRAMPs suggest that in addition to the IRT family of Fe transporters, AtNRAMPs may contribute to Fe homeostasis in plants (Eide et al., 1996; Curie et al., 2000; Thomine et al., 2000). In Arabidopsis, AtNRAMP3 disruption leads to an increase in Cd2+ resistance, whereas overexpression of this gene confers increased Cd2+ sensitivity (Thomine et al., 2000) indicating that this metal transporter gene plays a role in plant Cd2+ transport and sensitivity.

To further understand the roles of this transporter gene family in metal homeostasis in plants, a more systematic characterization of the different members of the AtNRAMP family will be required. Efforts should be made to determine their substrate specificity by heterologous expression in yeast, their cell and tissue-specific expression, the cell membrane in which they reside, together with extensive functional characterization of AtNRAMP-disrupted mutants. Due to possible partial redundancies double or multiple mutants may be required, although cadmium and iron transport-related phenotypes for AtNRAMP3 overexpression and gene disruption have been identified (Thomine et al., 2000).

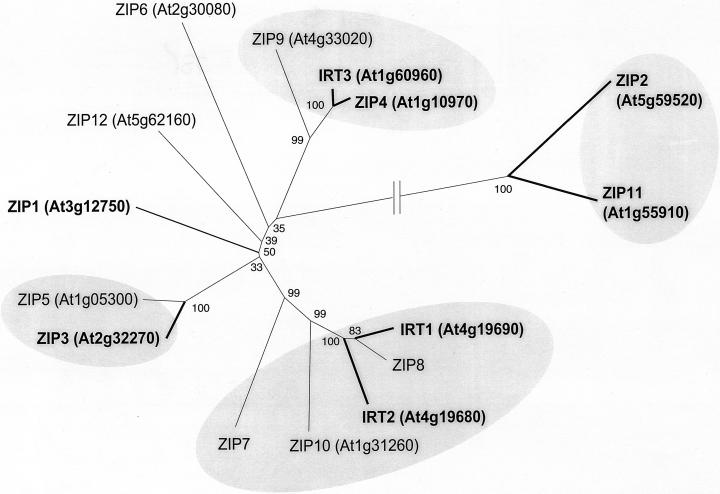

ZIP Metal Transporter Family

Members of the ZIP gene family, a novel metal transporter family first identified in plants, are capable of transporting a variety of cations including Cd, Fe, Mn, and Zn (Guerinot, 2000). The family takes its name from the founding members, ZRT1, ZRT2, and IRT1. ZRT1 and ZRT2 are, respectively, the high- and low-affinity Zn transporters of S. cerevisiae (Zhao and Eide, 1996a, 1996b). IRT1 is an Arabidopsis transporter that is expressed in the roots of Fe-deficient plants (Eide et al., 1996) and is believed to be responsible for the uptake of Fe from the soil. The ZIP family of Arabidopsis contains 14 other members in addition to IRT1, with overall amino acid sequence similarities ranging between 38% and 85%. Alignment of the predicted amino acid sequences shows that the ZIP proteins can be divided into four groups, with one of the groups clearly being more distantly related (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Phylogenetic tree of Arabidopsis ZIP transporters. Gene names and accession nos. are shown for each Arabidopsis sequence. Proteins for which a full-length cDNA is available are indicated by bold letters and lines. Alignments of full-length sequences were performed using ClustalW (Higgins and Sharp, 1988). The tree and bootstrap analyses were performed using the neighbor-joining algorithm implemented in MEGA version 2.0 (Kumar et al., 2000). Values indicate the number of times (in percent) that each branch topology was found during bootstrap analysis.

The presence of 15 different ZIP genes raises the question: Why does Arabidopsis need so many ZIP transporters? Metal ions need to be transported from the soil solution into the plant and then distributed throughout the plant, crossing both cellular and organellar membranes. It is presumed that some of the ZIP proteins will be found to localize to different membranes. For example, S. cerevisiae has three ZIP family members, two of which, ZRT1 and ZRT2, function in uptake of Zn across the plasma membrane and one of which, ZRT3, functions in the transport of Zn from the vacuole into the cytoplasm (MacDiarmid et al., 2000). Furthermore, we know that some Arabidopsis ZIP family members have different substrate specificities and affinities. At this time, we have functional information for five Arabidopsis ZIP members based on yeast complementation. ZIP1, ZIP2, and ZIP3 can rescue a Zn uptake mutant of yeast and have been shown to mediate Zn uptake (Grotz et al., 1998). When expressed in yeast, IRT1 mediates uptake of Fe, Zn, and Mn (Eide et al., 1996; Korshunova et al., 1999). Cadmium inhibits uptake of these metals by IRT1 and expression of IRT1 in yeast results in increased sensitivity to Cd (Rogers et al., 2000), suggesting that Cd is also transported by IRT1. IRT2 can complement both the Fe and Zn uptake mutants of yeast but, unlike IRT1, it does not appear to mediate the transport of Mn or Cd in yeast (Vert et al., 2001). Both IRT1 (Eide et al., 1996) and IRT2 (Vert et al., 2001) are expressed in the roots of Fe-deficient plants. We also know that ZIP1, ZIP3, and ZIP4 are expressed in the roots of Zn-deficient plants and that ZIP4 is expressed in the shoots of Zn-deficient plants (Grotz et al., 1998). We are currently characterizing each of the ZIP family members as to whether they are transcriptionally responsive to levels of Fe, Zn, and/or Mn. We are also identifying lines that carry T-DNA insertions in specific ZIP genes as well as examining the effect of overexpression of each family member on metal uptake by the plant. We predict that some ZIP functions may be redundantly specified so overexpression phenotypes may be more informative than loss-of-function phenotypes.

The ZIP family includes proteins from bacteria, archaea, fungi, protozoa, insects, plants, and animals. At this time, over 85 ZIP family members have been identified and grouped into four main subfamilies (Gaither and Eide, 2001). Subfamily I includes all of the ZIP genes discussed here in addition to members from other plant species including pea (Pisum sativum), tomato, rice, and the metal-hyperaccumulating plant Thlaspi caerulescens. It has been suggested that a ZIP gene homolog, ZNT1, may be involved in the zinc hyperaccumulation seen in this species. Unlike the non-hyperaccumulating species T. arvense, T. caerulescens expresses ZNT1 at high levels regardless of the Zn status of the plant (Pence et al., 2000).

All of the functionally characterized ZIP proteins are predicted to have eight TM domains and a similar membrane topology in which the amino- and carboxy-terminal ends of the protein are located on the outside surface of the plasma membrane. This orientation has been confirmed for several family members. Arabidopsis ZIP proteins range from 326 to 425 amino acids in length; this difference is largely due to the length between TM domains III and IV, designated the “variable region.” In most cases, the variable region contains a potential metal-binding domain rich in His residues that is predicted to be cytoplasmic. For example, in IRT1, this motif is HGHGHGH. Although the function of this motif is unknown, such a His-rich sequence is a potential metal-binding domain and its conservation in many of the ZIP proteins suggests a role in metal transport or its regulation. Similar potential metal-binding domains have also been found in efflux proteins belonging to the CDF family (Paulsen and Saier, 1997).

The most conserved portion of the ZIP family proteins occurs in TM domain IV, which is predicted to form an amphipathic helix with a fully conserved His residue. This His residue, along with an adjacent polar residue, may comprise part of an intramembraneous heavy metal binding site that is part of the transport pathway (Eng et al., 1998). Consistent with this model, mutation of the conserved histidines or adjacent polar/charged residues in TM domains IV and V of IRT1 eliminated its transport function (Rogers et al., 2000). It is interesting that residues important in determining substrate specificity of IRT1 have been mapped to the loop region between TM domains II and III. This region is predicted to lie on the surface of the membrane and could be the site of initial substrate binding during the transport process.

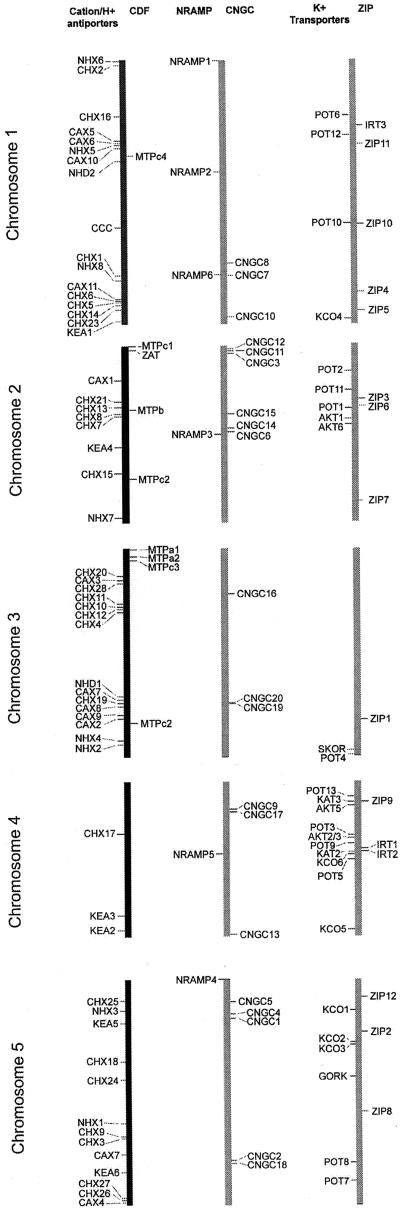

Chromosome Map and Summary

The chromosome positions of all transporters identified here are shown in Figure 9. At this time, it is unclear for most of these genes whether they provide redundant or unique functions. There are many cases in which members of a gene family are clustered with two or more closely linked genes. These gene clusters likely arose from a small regional duplication of a chromosome, originally producing two redundant copies of the same gene. Some of these clusters contain pairs of the most closely related genes (e.g. CNGC-19 and CNGC-20, group IVA), whereas others contain very distantly related homologs (e.g. CNGC2, group III and IVB, respectively; Fig. 5). This chromosomal view is of immediate practical significance to researchers considering strategies to make double and triple knockouts of selected genes.

Figure 9.

Chromosome positions of genes for selected cation transport families. Genes were arranged on chromosomes according to their locations in the genomic sequence (i.e. not the genetic map). Each chromosome is identified by its number and shown three times (black bar followed by two copies in gray). Each of the six gene families is separately mapped with all members aligned in a single column, as labeled at the top.

Phylogenetic analyses of selected cation transporter families have been synthesized and analyzed. These analyses show the number of genes, the number and constellation of sub groups, as well as the complexity of each of these gene families in the completed Arabidopsis genome. Furthermore, results from each of the analyzed gene families are described. The presented analyses should lead to testing of hypotheses by the plant membrane transport community that can be derived from the presented phylogenetic relationships. For example, new subgroups within gene families could indicate specialized functions, as already demonstrated for the SKOR and GORK outward-rectifying K+ channels, which occupy a special side branch in the K+ channel tree and are distinct in function from the related inward-rectifying K+ channels. Furthermore, duplicated and/or closely related genes could indicate partial redundancies that will be important for designing reverse genetic analyses of cation transporter functions. In addition, the presented analyses show a number of annotation errors and problems with the deposited genomic sequences. These problems are common and are a source of confusion to research on many gene families. The presented analyses and depositing of corrected annotations in public databases will be helpful for enhancing the use of the Arabidopsis genome sequence by many laboratories in the community. Furthermore, as the number of sequences from other plant species become increasingly available, evolutionary relationships among individual members in these gene families will emerge, which will lead to hypotheses and experiments testing whether related or unrelated functions are found among different species.

To further assist in the functional genomic analysis of transport genes in Arabidopsis and other plants, the Web-accessible PlantsT database (http://plantst.sdsc.edu) has been created. The initial release of the database includes the alignments and chromosome locations of the families of transporters examined in this paper. We are in the process of populating the database with the complete set of transport proteins in Arabidopsis, based on identifications of homologs to each protein family identified in the tentative consensus system of Saier (http://www.biology.ucsd.edu/∼msaier/transport). The PlantsT database will provide a curated, nonredundant view of each protein based on information extracted from the literature as well as additional information contributed by the members of this project and the plant membrane transport research community. In particular, the database will include the protein and nucleic acid sequence information, and sequence annotation from the research community, experimental information about metal concentrations in mutant lines, and additional functional information.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Transporter families were generated using several methods and details for the analysis of each family are provided in the figure legends. An overview is presented here. Inclusion of sequences from the complete Arabidopsis genome in families was based on homology and the presence of signature sequences. Blast searches (Altschul et al., 1997) were performed using protein sequences of previously characterized transporters. AGI gene codes for family members were obtained from (http://www.biology.ucsd.edu/∼ipaulsen/transport/), (http://www.cbs.umn.edu/arabidopsis), and (http://www.mips.biochem.mpg.de/proj/thal/db/index.html). Predicted protein sequences were obtained from the MATDB and compared with translated cDNA and EST sequences from GenBank. For several transporters, the protein sequence predicted from genomic DNA sequence was determined to contain errors detected by comparison with published cDNA sequences, EST sequences in GenBank, tentative consensus sequences from The Institute for Genomic Research (http://www.tigr.org/tdb/agi/), or unpublished cDNA sequence data. When possible, confirmed sequences were used for phylogenetic analysis. Multiple alignments were performed using ClustalW (Thompson et al., 1994) and ClustalX (Thompson et al., 1997). Unrooted trees were prepared by the neighbor-joining method using either Clustal, PHYLIP (Felsenstein, 1989), or Paup (Swofford, 1998), and 1,000 (or 10,000 for CNGCs) bootstrap replicates were performed. Bold lines on trees indicate protein sequences that were confirmed by cDNA sequencing or EST consensus. Where possible, gene names have been assigned to facilitate future efforts to determine functions of family members and, in several cases, conflicting gene names and numbers have been resolved.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The following authors were responsible for the analyses presented in this paper: potassium channels and transporter family, Pascal Mäser and Julian I. Schroeder (julian@biomail.ucsd.edu); NRAMP metal transporter family, Sebastien Thomine (sebastien.thomine@isv.cnrs-gif.fr) and Julian I. Schroeder; cation/H+ antiporter family, John M. Ward, Kendal Hirschi, and Heven Sze (hs29@umail.umd.edu); CNGC transporter family, Anna Amtmann, Ina N. Talke, Frans J.M. Maathuis, and Dale Sanders (ds10@york.ac.uk); bioinformatics, chromosome map, and web page design, Jeff F. Harper, Jason Tchieu, and Michael Gribskov (gribskov@sdsc.edu); CDF metal transporter family, Michael W. Persans and David E. Salt (salt@hort.purdue.edu); and ZIP metal transporter family, Sun A Kim and Mary Lou Guerinot (mary.lou.guerinot@dartmouth.edu). Please use the e-mail addresses provided to contact authors for further information.

Footnotes

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation (grant no. DBI–0077378 to M.L.G., D.E.S., J.I.S., J.F.H., and M.G.), by The Human Frontiers Science Program fellowship program (support to P.M.), and by AstraZeneca (studentship to I.N.T.). The PlantsT database is partially supported by the resources of the National Biomedical Computation Resource (grant no. NIH/NCRR P41 RR–08605).

LITERATURE CITED

- Ache P, Becker D, Ivashikina N, Dietrich P, Roelfsema MR, Hedrich R. GORK, a delayed outward rectifier expressed in guard cells of Arabidopsis thaliana, is a K(+)-selective, K(+)-sensing ion channel. FEBS Lett. 2000;486:93–98. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02248-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso JM, Hirayama T, Roman G, Nourizadeh S, Ecker JR. EIN2, a bifunctional transducer of ethylene and stress responses in Arabidopsis. Science. 1999;284:2148–2152. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5423.2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaeffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JA, Huprikar SS, Kochian LV, Lucas WJ, Gaber RF. Functional expression of a probable Arabidopsis thaliana potassium channel in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:3736–3740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.9.3736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apse MP, Aharon GS, Snedden WA, Blumwald E. Salt tolerance conferred by overexpression of a vacuolar Na+/H+ antiport in Arabidopsis. Science. 1999;285:1256–1258. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5431.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arazi T, Kaplan B, Fromm H. A high-affinity calmodulin-binding site in a tobacco plasma membrane channel protein coincides with a characteristic element of cyclic nucleotide-binding domains. Plant Mol Biol. 2000;42:591–601. doi: 10.1023/a:1006345302589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arazi T, Sunkar R, Kaplan B, Fromm H. A tobacco plasma membrane calmodulin-binding transporter confers Ni2+ tolerance and Pb2+hypersensitivity in transgenic plants. Plant J. 1999;20:171–182. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelsen KB, Palmgreen MG. Inventory of the superfamily of P-type ion pumps in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2001;126:696–706. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.2.696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baizabal-Aguirre VM, Clemens S, Uozumi N, Schroeder JI. Suppression of inward-rectifying K+channels KAT1 and AKT2 by dominant negative point mutations in the KAT1 alpha-subunit. J Membr Biol. 1999;167:119–125. doi: 10.1007/s002329900476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banuelos MA, Klein RD, Alexanderbowman SJ, Rodrigueznavarro A. A potassium transporter of the yeast Schwanniomyces Occidentalis homologous to the Kup system of Escherichia Colihas a high concentrative capacity. EMBO. 1995;14:3021–3027. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A, Birney E, Durbin R, Eddy SR, Howe KL, Sonnhammer EL. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:263–266. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bei Q, Luan S. Functional expression and characterization of a plant K+channel gene in a plant cell model. Plant J. 1998;13:857–865. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertl A, Anderson JA, Slayman CL, Sentenac H, Gaber RF. Inward and outward rectifying potassium currents in Saccharomyces cerevisiaemediated by endogenous and heterelogously expressed ion channels. Folia Microbiol. 1994;39:507–509. doi: 10.1007/BF02814074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumwald E, Aharon GS, Apse MP. Sodium transport in plant cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1465:140–151. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(00)00135-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumwald E, Poole RJ. Na+/H+ antiport in isolated tonoplast vesicles from storage tissue of Beta vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 1985;78:163–167. doi: 10.1104/pp.78.1.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutry M, Michelet B, Goffeau A. Molecular cloning of a family of plant genes encoding a protein homologous to plasma membrane H+-translocating ATPases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;162:567–574. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)92348-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao YW, Ward JM, Kelly WB, Ichida AM, Gaber RF, Anderson JA, Uozumi N, Schroeder JI, Crawford NM. Multiple genes, tissue specificity, and expression-dependent modulation contribute to the functional diversity of potassium channels in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 1995;109:1093–1106. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.3.1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cellier M, Prive G, Belouchi A, Kwan T, Rodrigues V, Chia W, Gros P. Nramp defines a family of membrane proteins. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10089–10093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.22.10089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XZ, Peng JB, Cohen A, Nelson H, Nelson N, Hediger MA. Yeast SMF1 mediates H+-coupled iron uptake with concomitant uncoupled cation currents. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:35089–35094. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.35089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemes S, Antosiewicz DM, Ward JM, Schachtman DP, Schroeder JL. The plant cDNA LCT1mediates the uptake of calcium and cadmium in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:12043–12048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.12043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough SJ, Fengler KA, Yu I, Lippok B, Smith RK, Jr, Bent AI. The Arabidopsis dnd1“defense, no death” gene encodes a mutated cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9323–9328. doi: 10.1073/pnas.150005697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin DS, Culbertson MR, Kung C. Interactions between gene products involved in divalent cation transport in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;244:303–311. doi: 10.1007/BF00285458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin DS, McMaster JA, Culbertson MR, Kung C. COT1, a gene involved in cobalt accumulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:3678–3688. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.9.3678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]