Abstract

Pulmonary surfactant (PS) is one of the main treatment for neonates with respiratory distress syndrome (RDS). Budesonide has recently been studied as an additional treatment in such cases, but there is limited evidence supporting this. This study was implemented to determine the efficacy of PS combined with budesonide in premature infants. To achieve this, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials by searching PubMed, Scopus, Embase, and the Cochrane Library from inception until July 12, 2024. We utilized a random-effects model to calculate the risk ratio and mean differences (MDs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the clinical outcomes of PS with budesonide versus PS alone. We used the GRADE approach to assess the quality of the evidence. We included 26 randomized controlled trials with a total of 2701 patients in the analysis. Treatments of PS with budesonide and PS alone were compared in all trials. PS with budesonide reduced bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) incidence (risk ratio, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.51, 0.73), duration of mechanical or invasive mechanical ventilation (MD, −2.21 days; 95% CI, −2.72, −1.71), duration requiring oxygen (MD, −5.86 days; 95% CI, −8.44, −3.29), and hospitalization time (MD, −5.61 days; 95% CI, −8.65, −2.56). These results were based on low to very low evidence certainty. Only moderate-to-severe BPD or severe BPD showed a significant reduction when PS was used in conjunction with budesonide, a finding supported by moderate evidence certainty. Our study showed that the administration of PS with budesonide significantly improved respiratory outcomes, including the incidence of BPD, duration of mechanical or invasive mechanical ventilation, duration requiring oxygen, and hospitalization time in preterm infants, without short-term adverse drug events. However, the evidence certainty was mostly low to very low.

Introduction

Preterm infants are particularly prone to respiratory problems and complications due to their undeveloped lungs [1, 2]. Some respiratory diseases can recover spontaneously, but such conditions may still have an impact on infants’ growth and development [1, 3]. Extremely premature newborns are at risk of respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) [1]. It is caused by low production of pulmonary surfactant (PS) [4, 5] which may result in bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) [6].

Pulmonary surfactant is a complex protein–lipid mixture produced by type II alveolar cells. It reduces alveolar surface tension, improves gas exchange, and prevents alveolar collapse [7]. The lack of PS in neonates results in respiratory distress, alveolar damage, and cytokine release [8]. Although multiple factors are known to cause BPD, research has indicated that inflammation plays an important role in its pathogenesis [9, 10]. This suggests that the use of steroids to decrease lung inflammation could be beneficial against BPD. Indeed, steroids have been introduced for premature infants with RDS or prolonged ventilation to help prevent further complications such as BPD [11]. Steroids can be administered systemically or via inhalation [12], with the former of these being particularly beneficial for treating these patients. Evidence has shown that systemic steroids can facilitate the successful extubation of patients [13] and reduce the rates of mortality and BPD at 36 weeks [14].

However, concerns have been raised regarding the systemic side effects associated with the use of systemic steroids, such as dexamethasone. It was, therefore, hypothesized that local steroid introduction to the lung would enhance efficacy and minimize adverse effects [15]. Budesonide, a locally high potency corticosteroid, is considered a supplementary treatment to be used in conjunction with PS for this vulnerable population. It is anticipated that the anti-inflammatory properties of steroids could reduce the respiratory morbidity associated with BPD and the severity of the condition [10]. The use of budesonide to supplement treatment with PS in infants with RDS to improve respiratory outcomes has been extensively explored [16, 17]. The study showed that administering budesonide with PS improved the rate of newborn BPD-free survival [17]. However, not all studies show a significant improvement in respiratory outcomes [18]. Despite the common use of dexamethasone and hydrocortisone systemically in preterm infants for the treatment and prevention of BPD, a thorough research has also investigated the potential benefit of local steroids in this regard. Certain side effects of inhaled corticosteroids, such as oral candida and dysphonia [19], are a limitation of using this type of steroids.

In our study, we focused on the effects of budesonide. This is particularly warranted, as conflicting results on the benefits of budesonide have been reported in terms of whether it is efficacious in conjunction with PS or can be administered using PS as a vehicle in the first few days of life in preterm infants [18]. Therefore, our systematic review and meta-analysis were performed to evaluate whether budesonide and PS affect respiratory and other clinical outcomes in preterm infants. We hypothesized that budesonide with PS improves preterm outcomes.

Materials and methods

Study protocol, registration, and ethical approval

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). We registered the research protocol (CRD42023438989) with PROSPERO. This research has received a certificate of exemption from the Research Ethics Committee of the Princess Srisavangavadhana College of Medicine, Chulabhorn Royal Academy (No.055/2566).

Data sources and search strategy

A comprehensive and methodical search was conducted on PubMed (National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD, USA), Scopus, Embase, and the Cochrane Library from their inception until July 12, 2024. The search terms were (“preterm” OR “premature”) AND [“surfactant” OR (“pulmonary surfactant”) OR (“exogenous surfactant”)] AND “budesonide.” The references of the identified papers were reviewed to find additional relevant studies.

Eligibility criteria

The review included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and human studies comparing PS plus budesonide to PS alone in preterm infants. There were no restrictions on the language in which the report was published.

Study selection

Two researchers (NP and MN) reviewed the scientific literature separately and independently by reviewing the relevance, study design, methods, and outcomes in accordance with the inclusion criteria. Conflicts were resolved through discussions with the third researcher (BT).

Data extraction and quality assessment

The reports on all included studies contained the following information: the first author’s name, study year, study design, participants’ country of origin, intervention type, and respiratory outcomes, including PS administrations, ventilation duration, and BPD incidence. Data on other preterm complications and side effects of corticosteroid were also extracted. When data were missing or unreported, or if we required additional data, we sent enquiries to the researchers via email. Bias was investigated using the revised Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment for Randomized Trials. This classification defines studies as having low or high bias or having some concerns about bias based on the RoB2 algorithm. The RoB2 assessment results were visually represented using robvis.

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

We used a random-effects model to compute risk ratios (RRs) for categorical variables and weighted mean differences (MDs) for continuous variables. We provided a 95% confidence interval (CI) for each estimate. An intervention-based subgroup analysis was used to identify the source of heterogeneity. In Q-statistic and heterogeneity assessments, values of 25%, 50%, and 75% were considered to represent low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively. A funnel plot was used to assess publication bias. P-values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. RevMan software was used for all meta-analyses.

The GRADE method with degradation criteria was used to categorize each outcome’s evidentiary certainty as high, moderate, low, or very low [20, 21]. This classification incorporated the risk of bias [22], inconsistency [23], indirectness [24], imprecision [25], and publication bias [26]. A GRADE evidence profile table was generated using the GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool (http://gradepro.org).

Definitions

Respiratory distress syndrome was diagnosed using radiographic and clinical evidence. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia was defined for infants with respiratory distress at birth who required oxygen (> 21%) at a postmenstrual age of 36 weeks or > 28 days old. Mental Development Index (MDI) and Psychomotor Development Index (PDI) scores of ≤ 69 were considered to represent developmental delay [15, 27].

Results

Search results

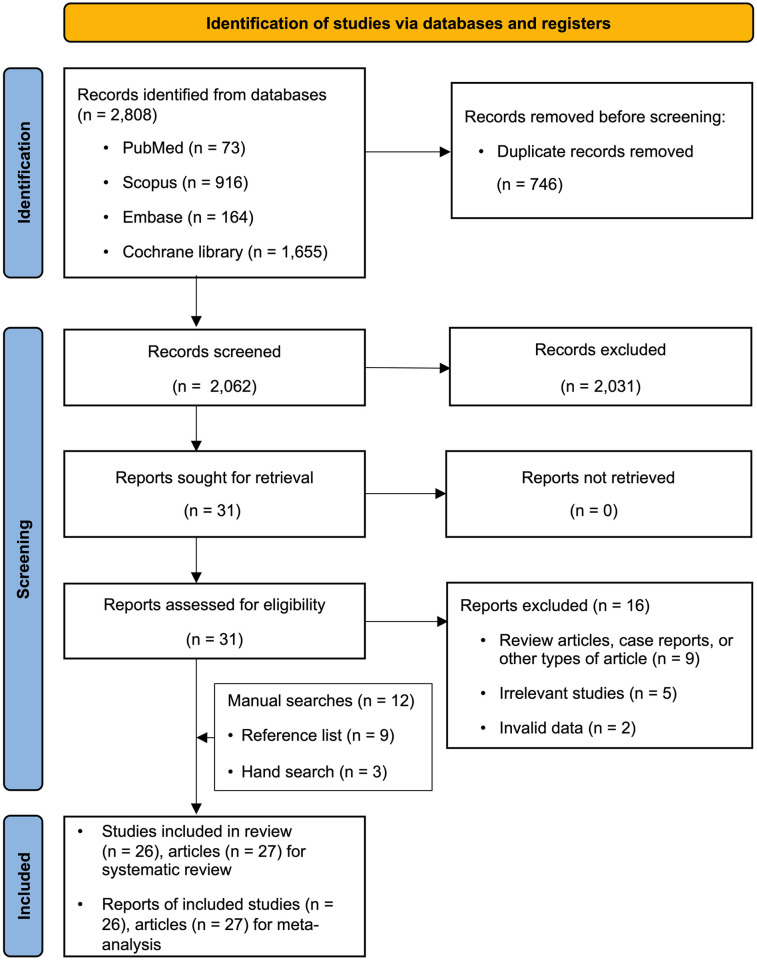

The database search yielded 2808 citations. After evaluating the titles and abstracts, we reviewed the full text of 31 articles. Fourteen studies (15 articles) met our inclusion and meta-analysis criteria. Twelve additional publications were retrieved from the reference lists of the included studies and other sources. A total of 16 studies were excluded from the analysis (S5 Table), of which nine were non-randomized controlled trials, five were irrelevant, and two contained invalid data (Fig 1).

Fig 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

Selection of studies for systematic review and meta-analysis.

Study characteristics

A meta-analysis of 26 RCTs (27 articles) [15–18, 27–49] with 2701 subjects was conducted. Among the subjects, 1343 received PS with budesonide, while 1358 received PS alone. Each clinical trial compared PS with budesonide to PS alone. In 19 RCTs [15–18, 28, 29, 31, 32, 37, 38, 40–44, 46–49], budesonide was administered by intratracheal (ITT) instillation with PS via an endotracheal tube or thin catheter, which was compared to PS alone administered by the same procedure. Meanwhile, in five RCTs, budesonide nebulization or inhalation with PS ITT was compared to PS ITT alone [33–36, 39]. In addition, one study [30] compared the use of nebulized PS and budesonide to nebulized PS alone. Finally, one study [45] evaluated PS alone (administration route and dosage unidentified) compared with nebulized or inhaled budesonide with PS (same as the control). Table 1 and S1 Table summarize the characteristics of the studies and participants. Overall, 19 trials were conducted in China, 1 in Taiwan [16, 27], and 5 in Iran [18, 33, 43, 48, 49]. One multicenter trial was conducted in China, Taiwan, and the United States [15]. The reports on these studies were published between 2008 and 2024. In total, 16 studies (17 articles) were reported in 2008–2019, while 10 were reported in 2020–2024.

Table 1. Characteristics of the included studies.

| Study | Type of study | Location | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Randomizationmethod | Study period | Comparator | N comparator | Control | N control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yeh 2008 | RCT | Taiwan | • BW < 1500 g • Severe RDS • Required MV with FiO2 ≥ 0.6 shortly after birth |

• Severe congenital anomalies • Lethal cardiopulmonary disorder |

Computer with permuted blocks | Sep 2004–Feb 2006 | PS 100 mg/kg ITT with budesonide 0.25 mg/kg ITT q 8 h | 60 | PS 100 mg/kg ITT q 8 h | 56 |

| Kuo 2010 | RCT (follow-up study) | Taiwan | • BW < 1500 g • Severe RDS • Required MV with FiO2 ≥ 0.6 shortly after birth • Survivor at 2 years old |

• Severe congenital anomalies • Lethal cardiopulmonary disorder |

Computer with permuted blocks | Sep 2004–Feb 2006 | PS 100 mg/kg ITT with budesonide 0.25 mg/kg ITT q 8 h | 35 | PS 100 mg/kg ITT q 8 h | 32 |

| Wan 2010 | RCT | China | • Preterm • RDS |

NR | NR | Dec 2006–Feb 2009 | PS 100 mg/kg ITT with budesonide 0.25 mg/kg ITT | 31 | PS 100 mg/kg ITT | 31 |

| Ke 2016 | RCT | China | • GA < 32 wks • BW < 1500 g • RDS required MV or CPAP with FiO2 ≥ 0.6 |

• Severe congenital anomalies • Severe CHD |

NR | Mar 2012–Sep 2014 | PS 200 mg/kg ITT with budesonide 0.25 mg/kg ITT | 46 | PS 200 mg/kg ITT | 46 |

| Yeh 2016 | RCT | Taiwan, China, and USA | • BW < 1500 g • Severe RDS (grades III–IV) required MV with FiO2 ≥ 0.5 |

• Severe congenital anomalies • Lethal cardiopulmonary disorder |

Computer with permuted blocks | Apr 2009–Mar 2013 | PS 100 mg/kg ITT with Pulmicort 0.25 mg/kg ITT | 131 | PS 100 mg/kg ITT | 134 |

| Pan 2017 | RCT | China | • GA < 32 wks • BW < 1500 g • RDS grades III–IV • Intrauterine infection |

• Severe CHD • Congenital anomalies • CDH • Respiratory malformations • Chromosomal abnormalities |

NR | Jun 2015–Mar 2016 | PS 70 mg/kg ITT with budesonide 0.25 mg/kg ITT | 15 | PS 70 mg/kg ITT | 15 |

| Cao 2018 | RCT | China | • GA < 32 wks • RDS • Required MV |

• Asphyxia • Severe congenital cardiopulmonary abnormalities |

Random number table | Jan 2014–Feb 2015 | PS 100 mg/kg inhalation with budesonide 0.25 mg/kg inhalation | 40 | PS 100 mg/kg inhalation | 40 |

| Deng 2018 | RCT | China | • BW < 1500 g • AGA • RDS grades III–IV |

• CHD • Congenital anomalies • CNS abnormalities • Severe congenital genetic metabolic disease • Pulmonary hemorrhage • ICH • Shock • Age > 8 h on admission • Mortality during treatment |

NR | Jan 2014–Dec 2015 | PS 150 mg/kg ITT with budesonide 0.25 mg/kg ITT | 18 | PS 150 mg/kg ITT | 28 |

| Luo 2018 | RCT | China | • GA ≤ 32 wks • BW ≤ 1500 g • RDS • On MV or noninvasive respirator |

• Severe CHD • Severe congenital anomalies • Shock • ICH • Sepsis |

NR | Aug 2016–Aug 2017 | PS 100 mg ITT with budesonide 0.25 mg ITT | 75 | PS 100 mg ITT | 75 |

| Sadeghnia 2018 | RCT | Iran | • GA 23–28 wks • RDS • Required CPAP with FiO2 > 0.4 |

• Congenital malformations • Prenatal asphyxia |

Odd/even document numbers | Jun 2014–Apr 2016 | PS 100 mg/kg ITT (LISA) with budesonide 0.5 mg q 12 h NB (max. 7 days) | 35 | PS 100 mg/kg ITT (LISA) | 35 |

| Wang 2018 | RCT | China | • RDS • Required MV |

• CHD • Lung malformation |

Random number table | Feb 2016– Aug 2017 | PS 100 mg/kg ITT with budesonide 0.25 mg/kg inhalation (continuous for 3 days) for budesonide | 72 | PS 100 mg/kg ITT | 72 |

| Yu 2018 | RCT | China | • RDS | • CHD • Congenital lung malformations • Severe systemic diseases |

Random number table | Jan 2015– May 2017 | PS 70 mg/kg ITT with budesonide 0.2–0.3 mg/kg inhalation (suspension) giving budesonide for 7 days | 18 | 1) PS 70 mg/kg ITT (with NSS as a placebo) |

16 |

| Du 2019 | RCT | China | • GA ≤ 32 wks • BW ≤ 1500 g • RDS |

• Written informed consent not provided | NR | Oct 2013–Feb 2015 | PS 100 mg/kg ITT with budesonide 0.25 mg/kg inhalation | 30 | PS 100 mg/kg ITT | 30 |

| Ping 2019 | RCT | China | • GA ≤ 34 wks • BW < 1500 g • Severe RDS • Required MV |

• Respiratory malformation • Air leak syndrome • Infection • Paralysis of respiratory muscle • CHD • Genetic metabolic disease • CNS abnormalities • Incomplete clinical data |

Random number table | Aug 2015–Dec 2017 | PS 150 mg/kg ITT with budesonide 0.25 mg/kg ITT | 64 | PS 150 mg/kg ITT | 64 |

| Su 2019 | RCT | China | • GA < 28 wks • Required FiO2 > 0.3 |

• Major congenital anomalies • Severe uterine infection |

Random number table | Dec 2016–Feb 2018 | PS 200 mg/kg ITT with budesonide 0.25 mg/kg ITT | 48 | PS 200 mg/kg ITT | 50 |

| Wang 2019 | RCT | China | • GA ≤ 32 wks • BW < 1500 g • RDS grades III–IV • Required invasive MV |

• Severe congenital malformations • Inherited metabolic disease • Abnormalities of the CNS • ICH • Massive pulmonary hemorrhage • Shock • GBS infection |

Random number table | Dec 2016–Feb 2018 | PS 70 mg/kg ITT with budesonide 0.5 mg inhalation | 28 | PS 70 mg/kg ITT | 28 |

| Zhou 2019 | RCT | China | • GA < 37 wks • BW < 1500 g • Severe RDS |

• Congenital respiratory tract malformations • Respiratory muscle paralysis • GBS infection • Air leak syndrome • Aspiration pneumonia • Congenital genetic metabolic disease • CHD • Shock • Severe neurological abnormalities |

Random number table | Aug 2015– Dec 2017 | PS 150 mg/kg ITT with budesonide 0.25 mg/kg ITT | 55 | PS 150 mg/kg ITT | 55 |

| Chen 2020 | RCT | China | • GA ≤ 32 wks • BW ≤ 1500 g • RDS |

NR | NR | Dec 2017–Jan 2018 | PS 100 mg/kg ITT with budesonide 0.25 mg/kg ITT | 30 | PS 100 mg/kg ITT | 30 |

| Chuanlong 2021 | RCT | China | • GA < 35 wks • BW < 2500 g • RDS |

NR | NR | Jan 2017– Jun 2019 | PS 70 mg/kg ITT with budesonide 0.25 mg/kg ITT | 39 | PS 70 mg/kg ITT | 39 |

| Gharehbaghi 2021 | RCT | Iran | • GA < 30 wks • BW < 1250 g • RDS • Required FiO2 > 40% • Required surfactant |

• Major congenital anomalies • Birth asphyxia (Apgar score < 4 at 5 min after birth) • Lethal cardiopulmonary disorder |

Block randomization | Oct 2017–Jun 2018 | PS 200 mg/kg ITT with budesonide 0.25 mg/kg ITT | 64 | PS 200 mg/kg ITT | 64 |

| Yang 2021 | RCT | China | • GA < 33 wks • BW ≤ 1500 g • RDS • Needed surfactant • Required respiratory support with FiO2 > 0.3 |

• Severe congenital abnormalities • Fatal cardiopulmonary diseases • Complex congenital heart diseases, • Congenital malformations in the respiratory system |

Random number table | Oct 2016–Oct 2019 | PS 70–140 mg ITT with budesonide 0.25 mg/kg ITT (if BW < 1.4 kg, 70 mg given; if BW ≥ 1.4 kg, 140 mg given ITT) | 97 | PS 70–140 mg ITT (if BW < 1.4 kg, 70 mg given; if BW ≥ 1.4 kg, 140 mg given) | 101 |

| Yao 2021 | RCT | China | • GA ≥ 28 but < 32 weeks • BW < 1500 g • Required MV |

• Hormone therapy within 28 days after birth • Congenital heart disease • Severe infectious diseases • Liver and kidney failure • Pneumothorax • Pulmonary infection |

Random number table | Dec 2017– Dec 2019 | PS, dosage, and route not reported (same as for control) with budesonide 0.5 mL inhalation twice a day for 2 wks | 47 | PS, dosage and route not reported | 47 |

| Zheng 2021 | RCT | China | RDS | • Asphyxia • CHD • Genetic disorders • Moderate-to-severe bronchiectasis |

Random number table | Jun 2018–Dec 2019 | PS 100 mg/kg ITT with budesonide 0.25 mg/kg ITT | 43 | PS 100 mg/kg ITT | 43 |

| Liu 2022 | RCT | China | • GA < 32 wks • BW < 1500 g • RDS • Respiratory support and PS required in 4 h after birth |

• Severe congenital malformations • Fatal cardiopulmonary diseases • Congenital genetic metabolic diseases and immunodeficiency diseases • Early i.v. use of glucocorticoids due to hypotension or hypoglycemia |

Random number table | Jan 2021– Jul 2021 | PS 200 mg/kg ITT with budesonide 0.25 mg/kg ITT | 60 | PS 200 mg/kg ITT | 62 |

| Armanian 2023 | RCT | Iran | • GA < 30 wks • Required NCPAP with FiO2 ≥ 30% |

• Congenital malformation • Asphyxia • Sepsis |

Permuted block randomization of size 6 | Mar 2020– Oct 2021 | PS 200 mg/kg 100 mg/kg for subsequent doses ITT if required, with budesonide once 0.25 mg/kg ITT | 95 | PS 200 mg/kg ITT | 95 |

| Safa 2023 | RCT | Iran | • GA < 37 wks • BW 800–1500 g • Moderate-to-severe RDS • Required mechanical ventilation |

• Severe congenital anomalies • Lethal cardiopulmonary disorder • Asphyxia • Sepsis |

NR | Dec 2020–Jan 2022 | PS 200 mg/kg ITT, with budesonide 0.25 mg/kg ITT | 35 | PS 200 mg/kg ITT | 35 |

| Marzban 2024 | RCT | Iran | • GA < 37 wks • BW > 700 g • RDS • GA < 37 wks and BW < 2500 g, with requirement for mechanical ventilation within 4 h after birth • GA > 28 wks with requirement for FiO2 > 40% • GA < 28 wks with requirement for FiO2 > 30% |

• BW < 700 g • Severe congenital anomalies • Fatal cardiopulmonary disease • Other causes of respiratory distress, such as CDH |

Covariate adaptive randomization | 2021 | PS 200 mg/kg ITT, with budesonide 0.25 mg/kg ITT | 67 | PS 200 mg/kg ITT | 67 |

Abbreviations: BW: birth weight; CDH: congenital diaphragmatic hernia; CHD: congenital heart disease; CNS: central nervous system; CPAP: continuous positive airway pressure; g: gram; FiO2: fraction of inspired oxygen; GA: gestational age; GBS: Group B Streptococcus; h: hour; ICH: intracranial hemorrhage; ITT: intratracheal; IV: intravenous; LISA: less invasive surfactant administration; MV: mechanical ventilation; NB: nebulization; NCPAP: nasal continuous positive airway pressure; NR: not reported; PS: pulmonary surfactant; RDS: respiratory distress syndrome; RCT: randomized controlled trial; wk: week

Risk of bias assessment

Six studies (seven articles) [15, 16, 18, 27, 30, 48, 49], in which the randomization processes were described and defined as having a low risk. Two studies involved deviations from the intended interventions. Loss to follow-up and selective reporting were adequate. According to the revised Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment, 5 studies had a low risk of bias, 1 had a high risk, and 20 had some concerns regarding risk of bias (S1 Fig).

Efficacy of PS with budesonide compared to PS alone on clinical outcomes

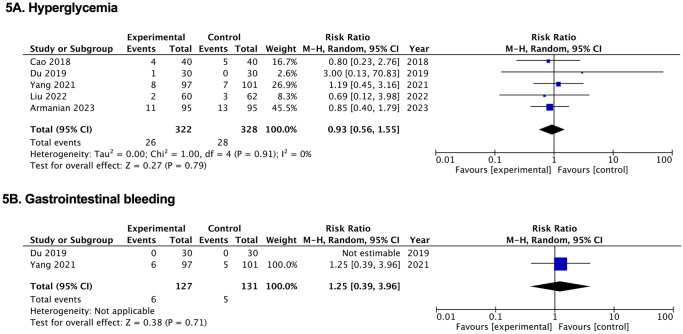

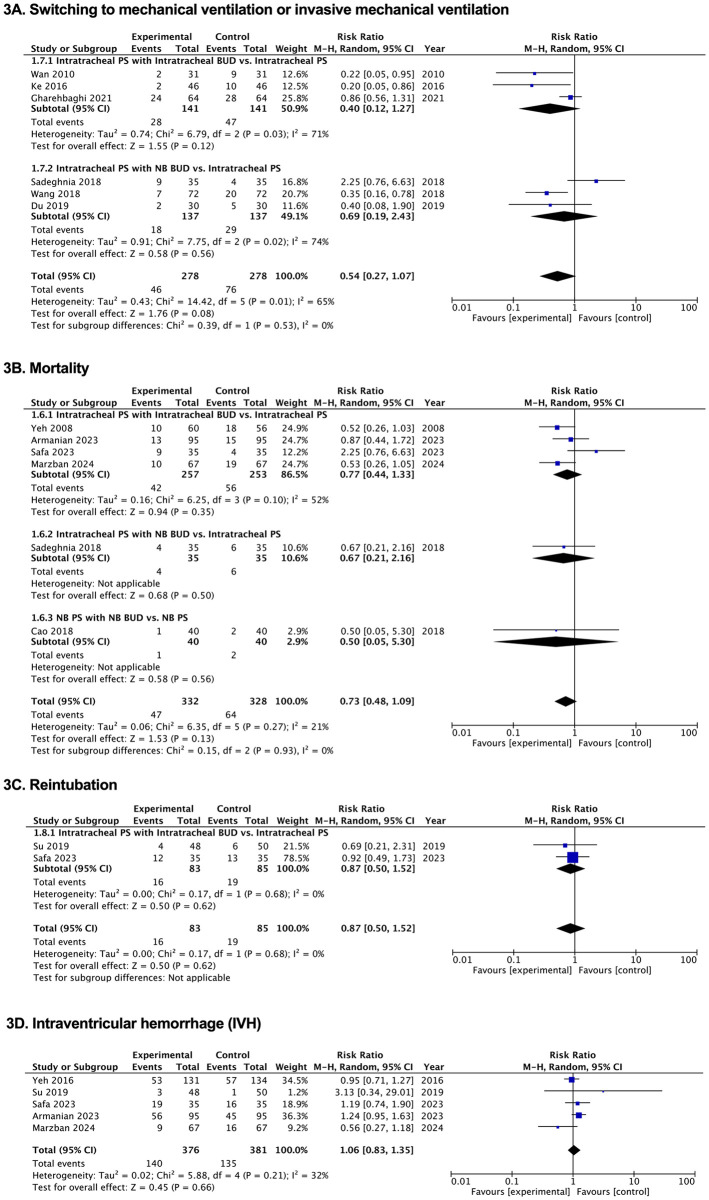

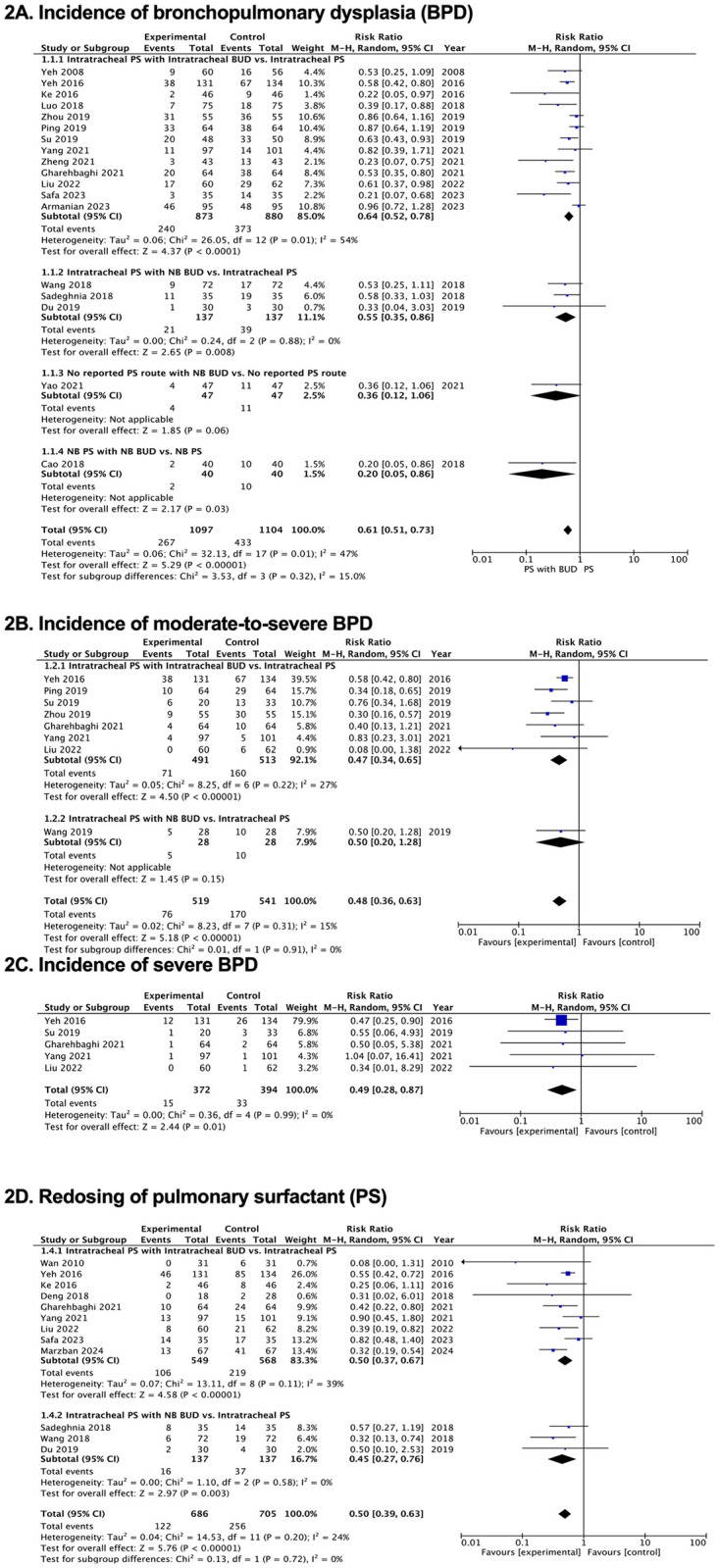

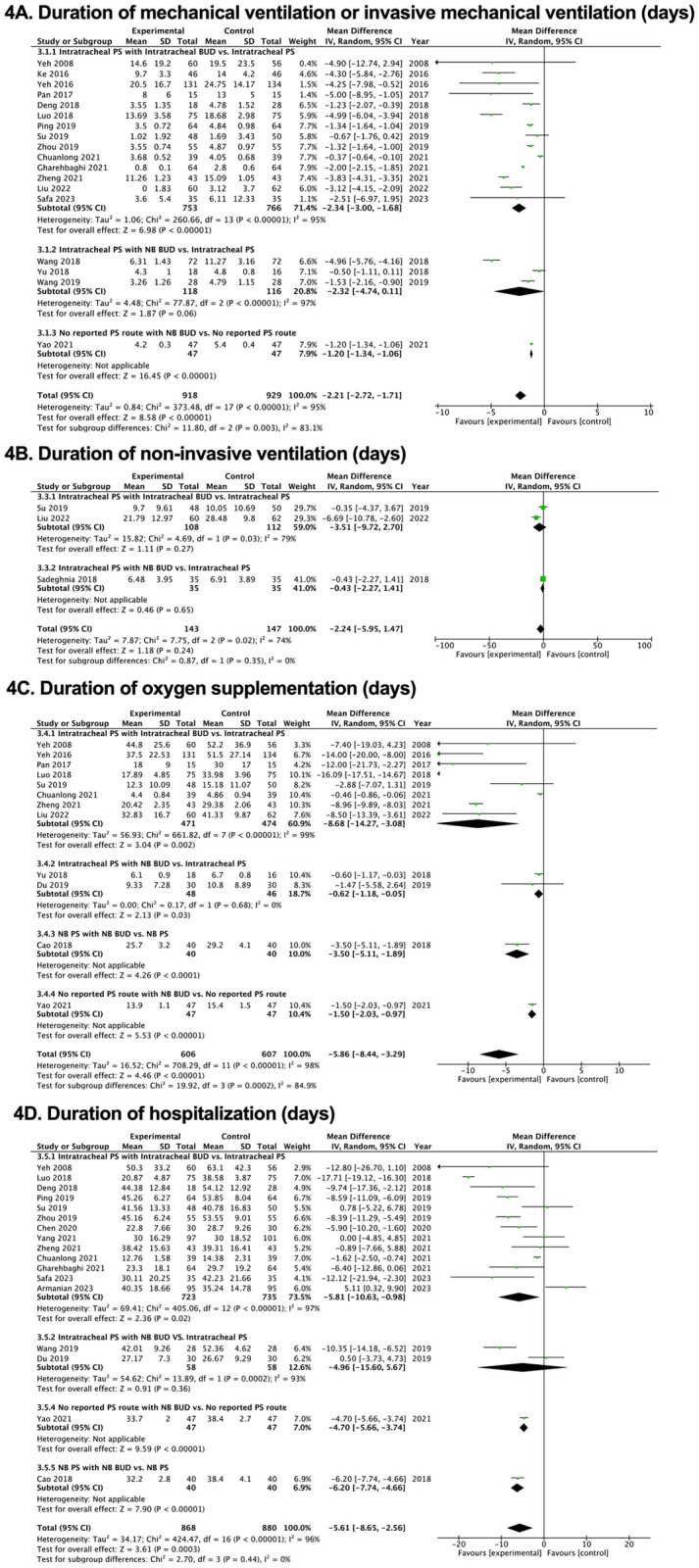

Figs 2–5, S2–S4 Tables and S2 and S3 Figs illustrate how PS and budesonide affect clinical outcomes and adverse effects in premature infants. Table 2 presents a GRADE summary of the findings on the efficacy of pulmonary surfactant with budesonide in premature infants.

Fig 2. Forest plots of effects of pulmonary surfactant with budesonide on clinical outcomes in neonates.

(A) Incidence of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD). (B) Incidence of moderate-to-severe BPD. (C) Incidence of severe BPD. (D) Redosing of pulmonary surfactant (PS). BUD, budesonide; NB, nebulization; PS, pulmonary surfactant.

Fig 5. Forest plots of the effects of pulmonary surfactant with budesonide on adverse effects in neonates.

(A) Hyperglycemia. (B) Gastrointestinal bleeding. BUD, budesonide; NB, nebulization; PS, pulmonary surfactant.

Table 2. GRADE summary of the findings on the efficacy of pulmonary surfactant with budesonide in premature infants.

| Patient or population: Preterm | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention: Pulmonary surfactant with budesonide | ||||||||||||

| Comparison: Pulmonary surfactant | ||||||||||||

| Study design | No. of studies | Certainty assessment | No. of participants | Effect | ||||||||

| Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | PS with Budesonide | PS | Estimation of absolute effects | Certainty | ||||

| Risk (95% CI) | Absolute (95% CI) | |||||||||||

| Duration of mechanical ventilation or invasive mechanical ventilation (days) | ||||||||||||

| RCT | 18 | serious a | serious b | not serious | not serious | none | 918 | 929 | - | MD 2.21 lower (2.72 lower to 1.71 lower) |

⨁⨁◯◯ Low |

|

| Duration of non-invasive ventilation (days) | ||||||||||||

| RCT | 3 | serious a | serious b | not serious | serious d | none | 143 | 147 | - | MD 2.24 lower (5.95 lower to 1.47 higher) |

⨁◯◯◯ Very low |

|

| Duration of oxygen supplementation (days) | ||||||||||||

| RCT | 12 | serious a | serious b | not serious | not serious | publication bias strongly suspected | 606 | 607 | - | MD 5.86 lower (8.44 lower to 3.29 lower) |

⨁◯◯◯ Very low |

|

| Duration of hospitalization (days) | ||||||||||||

| RCT | 17 | serious a | serious b | not serious | not serious | none | 868 | 880 | - | MD 5.61 lower (8.65 lower to 2.56 lower) |

⨁⨁◯◯ Low |

|

| Respiratory outcomes | ||||||||||||

| Incidence of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) | ||||||||||||

| RCT | 18 | serious a | not serious | not serious | not serious | publication bias strongly suspected | 267/1097 (24.3%) | 433/1104 (39.2%) |

RR 0.61 (0.51 to 0.73) |

153 fewer per 1,000 (from 192 fewer to 106 fewer) |

⨁⨁◯◯ Low |

|

| Incidence of moderate-to-severe BPD | ||||||||||||

| RCT | 8 | serious a | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | 76/519 (14.6%) | 170/541 (31.4%) |

RR 0.48 (0.36 to 0.63) |

163 fewer per 1,000 (from 201 fewer to 116 fewer) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

|

| Incidence of severe BPD | ||||||||||||

| RCT | 5 | serious a | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | 15/372 (4.0%) | 33/394 (8.4%) |

RR 0.49 (0.28 to 0.87) |

43 fewer per 1,000 (from 60 fewer to 11 fewer) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

|

| Redosing of pulmonary surfactant (PS) | ||||||||||||

| RCT | 12 | serious a | not serious | not serious | not serious | publication bias strongly suspected | 122/686 (17.8%) | 256/705 (36.3%) |

RR 0.50 (0.39 to 0.63) |

182 fewer per 1,000 (from 222 fewer to 134 fewer) |

⨁⨁◯◯ Low |

|

| Mortality | ||||||||||||

| RCT | 6 | serious a | not serious | not serious | serious d | none | 47/332 (14.2%) | 64/328 (19.5%) |

RR 0.73 (0.48 to 1.09) |

53 fewer per 1,000 (from 101 fewer to 18 more) |

⨁⨁◯◯ Low |

|

| Switching to mechanical ventilation or invasive mechanical ventilation | ||||||||||||

| RCT | 6 | serious a | serious b | not serious | serious d | none | 46/278 (16.5%) | 76/278 (27.3%) |

RR 0.54 (0.27 to 1.07) |

126 fewer per 1,000 (from 200 fewer to 19 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ Very low |

|

a Downgraded by one level for risk of bias due to unblinded outcome assessment

b Downgraded by one level for inconsistency due to substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 50%).

c Downgraded by one level due to indirect effects; potential influence from other factors

d Downgraded by one level for imprecision as the 95% confidence interval includes both potential benefit and harm.

Abbreviation: CI: confidence interval; PS: Pulmonary surfactant; RCTs: Randomized controlled trials; RR: risk ratio

Respiratory outcomes

Incidence of BPD

We analyzed the results from 18 RCTs [15–18, 30, 32–34, 36–38, 40, 43–48] involving 2,201 participants. Budesonide with PS reduced the incidence of BPD compared with that in the control group (RR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.51, 0.73), with low-quality evidence certainty. Eight studies [15, 37–40, 43, 44, 47] found a significant difference in the incidence of moderate-to-severe BPD for budesonide with PS compared with the rate for the control group (RR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.36, 0.63), with moderate evidence certainty. Five studies [15, 38, 43, 44, 47] demonstrated that budesonide with PS reduced the incidence of severe BPD compared with that in the control group (RR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.28, 0.87), with moderate-quality evidence certainty (Table 2, Fig 2A–2C, S2 and S4 Tables and S3 Fig).

Redosing of PS

Twelve RCTs [15, 17, 28, 31, 33, 34, 36, 43, 44, 47–49] showed a statistically significant difference in the incidence of redosing PS in the intervention group compared with that in the control group (RR, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.39, 0.63), with low-quality evidence certainty (Table 2, Fig 2D, S2 and S4 Tables and S3 Fig).

Incidence of switching to mechanical ventilation (MV) or invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) and MV or IMV duration

The findings regarding the need to switch to either MV or IMV as well as the duration of ventilators, were based on the terms used in each study. There was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of needing to switch to MV or IMV when budesonide was given with PS compared with that in the control group (RR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.27, 1.07) in six RCTs [17, 28, 33, 34, 36, 43] with very low-quality evidence certainty. In 18 studies [15–17, 29, 31, 32, 34, 35, 37–40, 42, 43, 45–48], the length of MV or IMV significantly decreased when budesonide was given with PS (MD, −2.21 days; 95% CI, −2.72, −1.71), with low-quality evidence certainty (Table 2, Figs 3A and 4A, S2–S4 Tables and S3 Fig).

Fig 3. Forest plots of the effects of pulmonary surfactant with budesonide on clinical outcomes in neonates.

(A) Switching to mechanical ventilation or invasive mechanical ventilation. (B) Mortality. (C) Reintubation. (D) Intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH). BUD, budesonide; NB, nebulization; PS, pulmonary surfactant.

Fig 4. Forest plots of the effects of pulmonary surfactant with budesonide on clinical outcomes in neonates.

(A) Duration of mechanical ventilation or invasive mechanical ventilation (days). (B) Duration of non-invasive ventilation (days). (C) Duration of oxygen supplementation (days). (D) Duration of hospitalization (days). BUD, budesonide; NB, nebulization; PS, pulmonary surfactant.

Reintubation

Compared with the rate in the control group, budesonide with PS did not significantly lower the number of reintubations in two RCTs [38, 48] (RR 0.87; 95% CI 0.50, 1.52) with low-quality evidence certainty (Fig 3C, S2 and S4 Tables).

Duration of non-invasive ventilation and oxygen supplementation

Three RCTs [33, 38, 47] showed that budesonide with PS did not significantly shorten the noninvasive ventilation time (MD, −2.24 days; 95% CI, −5.95, 1.47) with very low-quality evidence certainty. In 12 studies [15, 16, 29, 30, 32, 35, 36, 38, 42, 45–47], there was a substantial reduction in the duration of oxygen supplementation in the intervention group compared with that in the control group (MD, −5.86 days; 95% CI, −8.44, −3.29 days), with very low-quality evidence certainty (Table 2, Fig 4B and 4C, S2, S3 Tables and S3 Fig).

Respiratory complications

Ventilator-associated pneumonia or respiratory infection, pneumothorax, and pulmonary hemorrhage

There was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia or respiratory infection, pneumothorax, and pulmonary hemorrhage when budesonide was administered with PS compared with that in the control group [(RR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.27, 1.10), (RR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.49, 2.57), and (RR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.40, 1.02), respectively], with low to very low-quality evidence certainty (S2 and S4 Tables and S2(A)–S2(C) Fig).

Neurological outcomes

Intraventricular hemorrhage, periventricular leukomalacia, and cerebral hemorrhage

There was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of intraventricular hemorrhage between budesonide with PS and the control group (RR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.83, 1.35) in five RCTs [15, 18, 38, 48, 49], with very low-quality evidence certainty. The incidences of periventricular leukomalacia and cerebral hemorrhage were not significantly different between the two groups in two RCTs [38, 47] and four RCTs [30, 37, 40, 47] [(RR, 1.72; 95% CI, 0.42, 7.12) and (RR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.89, 1.42), respectively], also with very low-quality evidence certainty (Fig 3D, S2 and S4 Tables and S2(D) and S2(E) Fig).

MDI ≤ 69 and PDI ≤ 69 scores and MDI and PDI scores at 2–3 years

Two RCTs [15, 27] comparing budesonide with PS to a control group found no significant difference in the incidences of MDI ≤ 69 (RR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.57, 1.36) and PDI ≤ 69 (RR, 0.86; 95%, 0.58, 1.26), with low-quality evidence certainty. The MDI and PDI scores exhibited no significant differences in the intervention group compared with those in the control group [(MD, 2.38; 95% CI, −1.33, 6.10) and (MD, 1.83; 95%, −3.11, 6.76), respectively], with low-quality evidence certainty (S3 and S4 Tables and S2(F)–S2(I) Fig).

Other preterm outcomes

The incidence of mortality was not significantly different between the group receiving budesonide with PS and the control group (RR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.48, 1.09), with low-quality evidence certainty in six studies [16, 18, 30, 33, 48, 49]. Duration of hospitalization was significantly shortened in the budesonide with PS group (MD, −5.61 days; 95% CI, −8.65, −2.56), with low-quality evidence certainty from 17 RCTs [16, 18, 30–32, 36–46, 48] (Table 2, Figs 3B and 4D, S2–S4 Tables and S3 Fig).

There was no significant difference in the outcomes of retinopathy of prematurity, necrotizing enterocolitis, or sepsis when using PS with budesonide compared with the levels in the control, with very low-quality evidence certainty (S2 and S4 Tables, S2(J)–S2(L) and S3 Figs).

In 12 studies [15, 16, 18, 30, 33, 38, 43–48], the incidence of patent ductus arteriosus was significantly reduced in the PS with budesonide group (RR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.72, 0.94), with very low-quality evidence certainty (S2 and S4 Tables, S2(M) and S3 Figs).

Adverse effects

No significant differences in the incidence of hyperglycemia or gastrointestinal bleeding were observed between the groups [(RR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.56, 1.55) and (RR, 1.25; 95% CI, 0.39, 3.96), respectively] (Fig 5A and 5B, S2 and S4 Tables).

Discussion

Pulmonary surfactant lowers surface tension and optimizes lung function. As PS deficits worsen in premature newborns with RDS, there is an increase in the shear force of alveolus opening, which could lead to the development of BPD. Research has shown that steroids prevent BPD and enhance lung function. In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we compared the effects of PS with budesonide administered by any route to PS alone on BPD and respiratory outcomes, such as PS redosing and ventilation time. Other clinical outcomes included hospitalization time and preterm complications, such as intraventricular hemorrhage, retinopathy of prematurity, and necrotizing enterocolitis. Adverse effects, including hyperglycemia and gastrointestinal bleeding, were also monitored.

There has been long-standing discussion regarding the benefits of using posnatal steroids for respiratory outcomes and other complications associated with preterm birth. Early systemic dexamethasone and hydrocortisone have demonstrated beneficial effects in reducing death or BPD at 36 weeks [14, 50]. However, concerns were raised regarding an association between dexamethasone and cerebral palsy [51, 52]. The administration of steroids via inhalation or ITT instillation has been extensively investigated in the last few years. The use of PS as a vehicle for budesonide was also comprehensively studied by Yeh et al., who calculated the optimal ratio of PS to budesodine for use. There were studies that used budesonide in conjunction with PS (i.e., without mixing but administered at the same time) and may continue budesonide later on. In our study, we showed the benefits on BPD when PS and budesonide were coadministered compared with PS alone by either route (RR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.51, 0.73). In a subgroup analysis of 13 trials, BPD decreased significantly when PS and budesonide were given intratracheally (RR, 0.64; 95% CI 0.52, 0.78), while in 3 studies, budesonide was given as an aerosol along with PS given intratracheally (RR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.35, 0.86). One study on PS with budesonide as an aerosol (albeit without details on the route and dosage) revealed no significant decrease in the incidence of BPD compared with that in a control group (RR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.12, 1.06). In one study comparing PS and budesonide as an aerosol with PS alone as an aerosol, the former was found to reduce the incidence of BPD (RR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.05, 0.86). Overall, these studies show that, when PS was given with budesonide, the incidence of BPD decreased considerably compared with that when PS alone was administered. Notably, only the results on the incidence of moderate-to-severe BPD or severe BPD were supported by moderate-quality evidence certainty. Otherwise, the quality of evidence certainty was low to very low, including for other respiratory outcomes, such as redosing of PS, even the incidence of which was reduced for PS and budesonide compared with that for PS alone.

Administering PS and budesonide did not reduce the need to switch to MV or IMV. This means that the incidence of patients requiring escalation of respiratory support, such as a mechanical ventilator or invasive ventilation, was not decreased by this treatment combination, but the duration of MV or invasive MV decreased, as was the duration requiring oxygen. Although the duration of MV or IMV was shorter by 2.21 days in the group for which PS and budesonide were administered than in the group administered with PS alone, the main reduction occurred in the group for which PS and budesonide were administered intratracheally.

The overall need for non-invasive ventilation did not significantly decrease in the intervention group compared with the control group. Whether or not noninvasive treatment or oxygen therapy were used may depend on the practices at particular institutions. Variation in this regard could involve certain institutions continuing continuous positive airway pressure or oxygen supplement for a while, based on different criteria. However, the overall incidence of oxygen therapy decreased in the group for which combined therapy was administered, as did the overall hospitalization time by 5.61 days.

In a pooled estimate of studies, budesonide with PS did not reduce the reintubation rate or respiratory complications, such as pneumothorax and pulmonary hemorrhage, according to our meta-analysis. In addition, no increase in sepsis, ventilator-associated pneumonia, or respiratory infection was found compared with the rates in the control group. Therefore, administering budesonide may not improve, but it may also not increase the risk of these outcomes.

Tang et al. in 2021 [53] and Yi et al. in 2022 [54] conducted meta-analyses of 17 and 10 articles, respectively, to compare PS alone with PS and budesonide co-administration. In these studies and our own meta-analysis, PS with budesonide was found to significantly reduce the incidence of BPD, mechanical ventilation time, and hospital stay compared with PS alone but did not reduce the incidence of retinopathy of prematurity. The study by Tang et al. [53] and our study revealed significantly lower rates of PS redosing and patent ductus arteriosus when using PS with budesonide compared with the rates when using PS alone. However, this treatment combination did not reduce the incidence of intraventricular hemorrhage and did not significantly affect the MDI or PDI scores. Additionally, the results of our meta-analysis agreed with those of Yi et al. [54] regarding sepsis, necrotizing enterocolitis, and mortality, with these outcomes showing no significant reductions with the treatment combination.

As neurodevelopmental evaluation tools, the MDI examines adaptive behaviors, hand–eye coordination, visual and auditory perception, language abilities, cognitive ability, and exploratory activities [55, 56] whereas the PDI measures gross and fine motor movements [56]. In both of these tools, a score of ≤ 69 points is considered to reflect developmental delay [57]. The results of this study showed that PS plus budesonide had no impact on the MDI or PDI score, or on the incidence of cerebral hemorrhage or periventricular leukomalacia.

Our meta-analysis was conducted using the most recently published evidence. For inclusion in this systematic review and meta-analysis, the studies were mostly required to include subjects with a birth weight of less than 1500 g. There were 3 studies in which the subjects’ mean birth weight was less than 1000 g, 19 in which the mean birth weight was greater than 1000 g, and 4 studies in which there was no mean birth weight available but recruited the participants with the birth weight of 1500 g or less. The mean gestational age (GA) in the studies included here also correlated with birth weight; in the three studies with a lower mean birth weight, the mean GA was less than 28 weeks. The authors assumed that mean birth weight, or mean GA, may influence the effect of budesonide administration in conjunction with PS. These results suggest the need for further studies that consider the GA of the included subjects and their birth weight as variables to determine whether budesonide with PS exerts significant effects. Infants born extremely prematurely might benefit less from this therapeutic combination than those born at a later GA, as their lungs are more underdeveloped.

Currently, intensive research is ongoing worldwide; some of the studies are focusing on those born at less than 28 weeks, aimed at determining whether they will benefit from combining PS and budesonide. However, our study has demonstrated the benefits of administering budesonide in conjunction with PS to preterm populations, mostly in those with a GA of more than 28 weeks or a birth weight exceeding 1000 g, the evidence certainty for these findings is low to very low. Only results regarding the incidence of moderate-to-severe BPD or severe BPD were supported by moderate-quality evidence certainty.

Strengths and limitations

We performed a meta-analysis of the outcomes of preterm infants following the administration of PS with budesonide or PS alone. This work involved a large pooled-estimate meta-analysis that included 26 RCTs (27 articles). However, this work has some limitations that should be mentioned here. For example, neonatal care, PS types, dosages, and administration routes may have varied across the analyzed trials. Second, most RCTs were conducted in China and thus involved ethnically similar subject groups. Thus, well-designed large-scale RCTs with consistent, homogeneous protocols should be performed to investigate the value of PS with budesonide in premature infants.

Conclusions

The early administration of budesonide and PS may improve respiratory outcomes in premature infants. This combination significantly reduces the duration of mechanical ventilation or invasive mechanical ventilation, oxygen requirements, hospitalization, and incidences of BPD, patent ductus arteriosus, and PS redosing, with low to very low evidence certainty. Our findings suggest that these benefits come without significantly serious short-term side effects.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Chulabhorn Royal Academy, Bangkok, Thailand. There was no additional external funding received for this study.

References

- 1.Abiramalatha T, Ramaswamy VV, Bandyopadhyay T, Somanath SH, Shaik NB, Pullattayil AK, et al. Interventions to Prevent Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia in Preterm Neonates: An Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176(5):502–16. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.6619 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doyle LW, Carse E, Adams AM, Ranganathan S, Opie G, Cheong JLY. Ventilation in Extremely Preterm Infants and Respiratory Function at 8 Years. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(4):329–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1700827 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doyle LW, Anderson PJ. Long-term outcomes of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;14(6):391–5. Epub 20090919. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2009.08.004 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Claireaux AE. Hyaline membrane in the neonatal lung. Lancet. 1953;265(6789):749–53. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(53)91451-2 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Luca D. Respiratory distress syndrome in preterm neonates in the era of precision medicine: A modern critical care-based approach. Pediatr Neonatol. 2021;62 Suppl 1:S3–s9. Epub 20201205. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2020.11.005 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidt AR, Ramamoorthy C. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Paediatr Anaesth. 2022;32(2):174–80. Epub 20211215. doi: 10.1111/pan.14365 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akella A, Deshpande SB. Pulmonary surfactants and their role in pathophysiology of lung disorders. Indian J Exp Biol. 2013;51(1):5–22. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sweet DG, Carnielli V, Greisen G, Hallman M, Ozek E, Te Pas A, et al. European Consensus Guidelines on the Management of Respiratory Distress Syndrome—2019 Update. Neonatology. 2019;115(4):432–50. Epub 20190411. doi: 10.1159/000499361 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hwang JS, Rehan VK. Recent Advances in Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia: Pathophysiology, Prevention, and Treatment. Lung. 2018;196(2):129–38. doi: 10.1007/s00408-018-0084-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jensen EA, Watterberg KL. Postnatal Corticosteroids To Prevent Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. Neoreviews. 2023;24(11):e691–e703. doi: 10.1542/neo.24-11-e691 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olaloko O, Mohammed R, Ojha U. Evaluating the use of corticosteroids in preventing and treating bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm neonates. Int J Gen Med. 2018;11:265–74. Epub 20180703. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S158184 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shah SS, Ohlsson A, Halliday HL, Shah VS. Inhaled versus systemic corticosteroids for preventing bronchopulmonary dysplasia in ventilated very low birth weight preterm neonates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;10(10):Cd002058. Epub 20171017. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002058.pub3 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doyle LW, Davis PG, Morley CJ, McPhee A, Carlin JB. Low-dose dexamethasone facilitates extubation among chronically ventilator-dependent infants: a multicenter, international, randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2006;117(1):75–83. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2843 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doyle LW. Postnatal Corticosteroids to Prevent or Treat Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. Neonatology. 2021;118(2):244–51. doi: 10.1159/000515950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yeh TF, Chen CM, Wu SY, Husan Z, Li TC, Hsieh WS, et al. Intratracheal Administration of Budesonide/Surfactant to Prevent Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(1):86–95. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201505-0861OC . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yeh TF, Lin HC, Chang CH, Wu TS, Su BH, Li TC, et al. Early intratracheal instillation of budesonide using surfactant as a vehicle to prevent chronic lung disease in preterm infants: A pilot study. Pediatr. 2008;121(5):e1310–8. Epub 20080421. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1973 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ke H, Li Z, Yu X, Guo J. Efficacy of different preparations of budesonide combined with pulmonary surfactant in the treatment of neonatal respiratory distress syndrome: A comparative analysis. Chin J Contemp Pediatr. 2016;18(5):400–4. doi: 10.7499/j.issn.1008-8830.2016.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Armanian AM, Iranpour R, Lotfi A, Amini R, Kahrizsangi NG, Jamshad A, et al. Intratracheal Administration of Budesonide-instilled Surfactant for Prevention of Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Iranian Journal of Neonatology. 2023;14(4):1–7. doi: 10.22038/IJN.2023.72572.2406 rayyan-1262676199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dubus JC, Marguet C, Deschildre A, Mely L, Le Roux P, Brouard J, et al. Local side-effects of inhaled corticosteroids in asthmatic children: influence of drug, dose, age, and device. Allergy. 2001;56(10):944–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2001.00100.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, Kunz R, Vist G, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):383–94. Epub 20101231. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: An emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist G, Kunz R, Brozek J, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE guidelines: 4. Rating the quality of evidence-study limitations (risk of bias). J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):407–15. Epub 20110119. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.017 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Woodcock J, Brozek J, Helfand M, et al. GRADE guidelines: 7. Rating the quality of evidence-inconsistency. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(12):1294–302. Epub 20110731. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.03.017 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Woodcock J, Brozek J, Helfand M, et al. GRADE guidelines: 8. Rating the quality of evidence-indirectness. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(12):1303–10. Epub 20110730. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.04.014 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Brozek J, Alonso-Coello P, Rind D, et al. GRADE guidelines 6. Rating the quality of evidence-imprecision. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(12):1283–93. Epub 20110811. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.01.012 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Montori V, Vist G, Kunz R, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 5. Rating the quality of evidence-publication bias. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(12):1277–82. Epub 20110730. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.01.011 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuo HT, Lin HC, Tsai CH, Chouc IC, Yeh TF. A follow-up study of preterm infants given budesonide using surfactant as a vehicle to prevent chronic lung disease in preterm infants. J Pediatr. 2010;156(4):537–41. Epub 20100206. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.10.049 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wan J, Li H, Ling L, Lin SX. Study on combining budesonide suspension, pulmonary surfactant Curosurf and nasal continuous positive airway pressure in treatment of respiratory distress syndrome of premature. Pharmaceutical Biotechnology. 2010;17(5):434–7. rayyan-1262676807. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pan J, Chen M, Ni W, Fang T, Zhang H, Chen Y, et al. Clinical efficacy of pulmonary surfactant combined with budesonide for preventing bronchopulmonary dysplasia in very low birth weight infants. Chin J Contemp Pediatr. 2017;19(2):137–41. doi: 10.7499/j.issn.1008-8830.2017.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cao Y, Yao G, Wang Y, Shi B, Liu J, Li G. Aerosol inhalation of budesonide and pulmonary surfactant for the prevent bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Pediatr Pharm. 2018;24(3):25–9. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deng L, Peng H, Gong X. Efficacy of intracheal of budesonide using surfactant as a vehicle to treatment respiratory distress syndrome of preterm infants. Med Sci J Cent South China. 2018;46(1):91–4. doi: 10.15972/j.cnki.43-1509/r.2018.01.022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo L, Chen K, Cao B. Observation on curative effect of budesonide combined with pulmonary surfactant in preventing bronchopulmonary dysplasia in premature infants. Zhejiang Clin Med. 2018;20(5):796–7. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sadeghnia A, Beheshti BK, Mohammadizadeh M. The Effect of Inhaled Budesonide on the Prevention of Chronic Lung Disease in Premature Neonates with Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Int J Prev Med. 2018;9:15. Epub 20180208. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_336_16 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Y, Zhang D. Effect of budesonide inhalation combined with pulmonary surfactant on newborns with RDS. Mod Med J. 2018;46(11):1243–6. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu J, Yu T. Effects of different forms of budesonide combined with pulmonary surfactant in improving blood gas indicators and bronchopulmonary dysplasia in children with neonatal respiratory distress syndrome. Chin J Lung Dis. 2018;11(04):416–20. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Du FL, Dong WB, Zhang C, Li QP, Kang L, Lei XP, et al. Budesonide and Poractant Alfa prevent bronchopulmonary dysplasia via triggering SIRT1 signaling pathway. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2019;23(24):11032–42. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201912_19811 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ping L, Zhang S, Zhai S. Influence of combined drug therapy by intratracheal infusion on clinical prognosis of premature infants with severe RDS. Chin J Postgrad Med. 2019;42(2):154–7. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Su J, Yang Y, Yang L, Ding L, Zhong G, Liu L, et al. The clinical study of budesonide combined with pulmonary surfactant to prevent bronchopulmonary dysplasia in premature infants Int J of Pediatr. 2019;6:61–5. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Y, Yang M, Han P. Effect of budesonide suspension oxygenation atomization inhalation on prevention and treatment of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in premature infants. J Clin Exp Med. 2019;19:2121–4. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou X, Zhou J, Hu B, Wang X. Effects of budesonide combined with pulmonary surfactant on short-term efficacy, blood oxygen index, and risk of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm infants with severe respiratory distress syndrome. J Pediatr Pharm. 2019;25(11):27–30. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen A, Cheng Y, Yang H. Effect of budesonide on pulmonary surfactant in treating neonatal respiratory distress syndrome. Pharm Biotechnol. 2020;27(3):252–6. doi: 10.19526/j.cnki.1005-8915.20200314 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chuanlong Z. Evaluation of the Efficacy of Budesonide Combined with Pulmonary Surfactants on the Neonatal Respiratory Distress Syndrome by Pulmonary Ultrasonography. Sci Program. 2021;2021(2329524):6. doi: 10.1155/2021/2329524 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gharehbaghi MM, Mhallei M, Ganji S, Yasrebinia S. The efficacy of intratracheal administration of surfactant and budesonide combination in the prevention of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Res Med Sci. 2021;26:31. Epub 20210527. doi: 10.4103/jrms.JRMS_106_19 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang B, Lei H, Ren Z, Li L, Wang H, Huang D, et al. Pulmonary surfactant in combination with intratracheal budesonide instillation for treatment of respiratory distress syndrome in preterm infants: A randomized controlled trial. Chin J Neonatology. 2021;36(2):33–7. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yao Y, Zhang G, Wang F, Wang M. Efficacy of budesonide in the prevention and treatment of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in premature infants and its effect on pulmonary function. Am J Transl Res. 2021;13(5):4949–58. Epub 20210515. . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zheng J, Yan H. Effect of calf pulmonary surfactant for injection combined with budesonide on prevention and treatment of neonatal bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Chin J Pract Med. 2021;48(16):102–6. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn115689-20210519-01751 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu M, Ji L, Dong M, Zhu X, Wang H. Efficacy and safety of intratracheal administration of budesonide combined with pulmonary surfactant in preventing bronchopulmonary dysplasia: A prospective randomized controlled trial. Chin J Contemp Pediatr. 2022;24(1):78–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Safa FB, Noorishadkam M, Lookzadeh MH, Mirjalili SR, Ekraminasab S. Budesonide and surfactant combination for treatment of respiratory distress syndrome in preterm neonates and evaluation outcomes. J Clin Neonatol. 2023;12(4):135–41. doi: 10.4103/jcn.jcn_52_23 rayyan-1262789039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marzban A, Mokhtari S, Tavakkolian P, Mansouri R, Jafari N, Maleki A. The impact of combined administration of surfactant and intratracheal budesonide compared to surfactant alone on bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) and mortality rate in preterm infants with respiratory distress syndrome: a single-blind randomized clinical trial. BMC Pediatr. 2024;24(1):262. Epub 20240420. doi: 10.1186/s12887-024-04736-9 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morris IP, Goel N, Chakraborty M. Efficacy and safety of systemic hydrocortisone for the prevention of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm infants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Pediatr. 2019;178(8):1171–84. Epub 20190529. doi: 10.1007/s00431-019-03398-5 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rocha G, Calejo R, Arnet V, de Lima FF, Cassiano G, Diogo I, et al. The use of two or more courses of low-dose systemic dexamethasone to extubate ventilator-dependent preterm neonates may be associated with a higher prevalence of cerebral palsy at two years of corrected age. Early Hum Dev. 2024;194:106050. Epub 20240520. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2024.106050 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shinwell ES, Karplus M, Reich D, Weintraub Z, Blazer S, Bader D, et al. Early postnatal dexamethasone treatment and increased incidence of cerebral palsy. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2000;83(3):F177–81. doi: 10.1136/fn.83.3.f177 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tang W, Chen S, Shi D, Ai T, Zhang L, Huang Y, et al. Effectiveness and safety of early combined utilization of budesonide and surfactant by airway for bronchopulmonary dysplasia prevention in premature infants with RDS: A meta-analysis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2022;57(2):455–69. Epub 20211125. doi: 10.1002/ppul.25759 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yi Z, Tan Y, Liu Y, Jiang L, Luo L, Wang L, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of pulmonary surfactant combined with budesonide in the treatment of neonatal respiratory distress syndrome. Transl Pediatr. 2022;11(4):526–36. doi: 10.21037/tp-22-8 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Duan Y, Sun FQ, Li YQ, Que SS, Yang SY, Xu WJ, et al. Prognosis of psychomotor and mental development in premature infants by early cranial ultrasound. Ital J Pediatr. 2015;41:30. Epub 20150409. doi: 10.1186/s13052-015-0135-5 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang X, Carroll X, Wang H, Zhang P, Selvaraj JN, Leeper-Woodford S. Prediction of Delayed Neurodevelopment in Infants Using Brainstem Auditory Evoked Potentials and the Bayley II scales. Front Pediatr. 2020;8:485. Epub 20200821. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.00485 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jia W, Wang X, Chen G, Cao H, Yue G, Luo M, et al. The relationship between late (≥ 7 days) systemic dexamethasone and functional network connectivity in very preterm infants. Heliyon. 2023;9(12):e22414. Epub 20231119. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e22414 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting information files.