Abstract

We have previously reported that DNase I hypersensitive site 5 (5′HS5) of the human β-globin locus control region functions as a chromatin insulator in stable transfection assays. In this report we show that a 3.2 kb DNA fragment containing the entire 5′HS5 region can protect a position-sensitive Aγ-globin gene against position effects in transgenic mice. Bracketing is required for function of 5′HS5 as an insulator. The 5′HS5 insulator operates in adult as well as in embryonic murine erythroid cells. The insulator has no significant stimulatory effects of its own. These results indicate that 5′HS5 can function as a chromatin insulator in vivo.

INTRODUCTION

Gene loci are organized into distinct domains that are delimited by specific cis elements termed chromatin boundaries. Boundaries between active and inactive chromatin are an inevitable consequence of the nature of gene organization. The notion of boundaries was initially supported by cytological studies, which showed that chromosomes are divided into a series of looped, topologically constrained domains that are attached to the nuclear matrix or scaffold. At the molecular level elements called ‘insulators’ have been shown to be associated with boundaries and/or boundary function (reviewed in 1–4). The first insulator elements to be described were scs and scs′, which are located at the boundaries of the Drosophila hsp70 heat shock gene (5). The best characterized boundary element in vertebrates is the insulator in the chicken β-globin locus (6,7). The extent of the active chromatin in this locus was determined by measurements of DNase I sensitivity and histone hyperacetylation. In this locus, a relatively sharp transition in both DNase I sensitivity and histone hyperacetylation is observed roughly coincident with the position of a DNase I hypersensitive site (HS), 5′HS4. The transition of histone acetylation occurs at the 5′ site of HS4 while HS4 itself is highly acetylated. A 1.2 kb DNA fragment spanning 5′HS4 displays all the properties of an insulator: in human cell lines it provides a directional block to enhancer action on a promoter and it is capable of protecting a gene from position effects in Drosophila. Like other insulators, the chicken insulator is transcriptionally neutral. The enhancer-blocking activity is concentrated in a 250 bp GC-rich core fragment, which is unmethylated in its natural context. Recently, a binding site for the ubiquitous DNA-binding protein CTCF was identified in 5′HS4, and the CTCF site is both necessary and sufficient for the enhancer blocking property of the insulator (8).

It is unclear whether the human β-globin locus is demarcated by boundary elements. In contrast to the chicken β-globin locus, studies of DNase I sensitivity within 200 kb DNA surrounding the human β-globin locus have failed to find a site that clearly marks a transition from a sensitive domain to a less sensitive one (9). Recently, it was found that a transition of acetylation status of histone H3 and H4 occurs between 5′HS4 and 5′HS5 of the murine β-globin locus control region (LCR) in MEL cells (10,11). The potential insulating activity of 5′HS5 of the human β-globin locus LCR has been tested because of similarities between chicken 5′HS4 and human 5′HS5: both sites are non-erythroid specific and are located in the 5′ end of the LCR. In enhancer blocking assays, 5′HS5 shows a moderate insulating activity (6,12). When tested in a reporter gene driven by a polyoma enhancer, 5′HS5 can significantly reduce variation of expression of the gene in stably transfected cells (13). On the other hand, a marked β-globin gene can be activated when placed 5′ to 5′HS5, suggesting that 5′HS5 is unable to restrain the enhancer activity of the LCR (14).

To further delineate the function of 5′HS5, we tested its ability to protect a transgene from position effects in transgenic mice. We have previously reported a series of µLCR Aγ-globin gene constructs carrying truncations of the Aγ gene promoter. While constructs carrying a –201 Aγ or –382 Aγ promoter conferred position-independent expression, the µLCR –730 Aγ construct was subject to very strong position effects (15). Thus the µLCR –730 Aγ-globin gene, known to be highly sensitive to position effects, was used in our study. We tested whether bracketing of this construct with human 5′HS5 will confer position-independent expression to the transgene. Our results indicate that: (i) 5′HS5 is capable of protecting a position-sensitive gene against position effects; (ii) this protection requires bracketing the transgene with 5′HS5.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Constructs

The constructs used in this study were assembled by conventional molecular cloning techniques. The DNA fragments in the constructs were the human γ-globin gene (GenBank accession code humhbb, coordinates 38700–41382), 5′HS5 (accession no. L22754), 5′HS5A (0.9 kb DraI fragment), 5′HS5B (1.3 kb EcoRV–AseI fragment) and µLCR, a 2.5 kb truncated version of the β-globin LCR, containing upstream DNase I HSs 1–4 (16). The coordinates in GenBank accession code humbb are: HS1, 13062–13769; HS2, 8486–9218; HS3, 4608–5172; HS4, 1182–1702. This element is a strong erythroid-specific transcription enhancer and mimics the LCR function in many aspects. The order of the fragments in the constructs is shown in Figure 1B and all fragments are in the sense orientation. The loxP site in the construct µγ5 is located downstream of the 5′HS5 fragment.

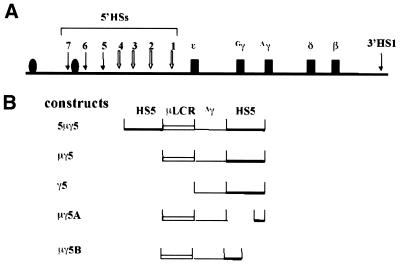

Figure 1.

Structure of the transgenes. (A) Diagram of the human β-globin locus. The locus consists of five genes (filled boxes) in the order of their developmental activation. The LCR contains four erythroid-specific DNase I HS (5′HS1–5′HS4, open arrows). The odorant receptor genes are marked as ovals. (B) The constructs used in this study. Each construct contains 5′HS5 (heavy bars), the µLCR (open bars) and the Aγ-globin gene (light lines). The names of the constructs are shown in the left column.

Transgenic mice

The construct DNA was released from the plasmid backbone by digestion with the appropriate restriction enzyme and purified by electrophoresis on an agarose gel. The purified DNA fragments were injected into fertilized mouse eggs (B6/C3F1) which were then transferred to pseudo-pregnant foster mothers (B6/D2F1). Founder animals were identified by slot blotting with a HS3 probe. F1 progeny were obtained by breeding founder animals with non-transgenic mice (B6/D2F1) and were screened for correct integration and to exclude the presence of mosaicism in the founders. To study human γ gene expression in the embryos, staged pregnancies were interrupted on day 12 of development. Samples from blood and yolk sac were collected from day 12 embryos, which contain mostly cells from primitive erythropoiesis. The samples from day 12 fetal liver and adult blood contain mostly cells from definitive erythropoiesis.

Structure analysis

DNA was isolated by standard procedures, then digested with a restriction enzyme. Aliquots of 10 µg DNA from each enzyme reaction were loaded onto a 0.8% agarose gel and DNA fragments were resolved by electrophoresis. Southern blot hybridization was performed with a 32P-labeled probe. The probe fragments used in this study were HS3 (GenBank accession code humhbb, coordinates 4348–5132), intron 2 of the γ-globin gene (coordinates 39985–40818), 5′HS5A (0.9 kb DraI fragment, accession no. L22754) and 5′HS5B (1.3 kb EcoRV–AseI fragment, accession no. L22754). Signals were quantitated on a phosphorimager. For copy number measurement, the blot was hybridized with a mixture of two probes containing intron 2 of the human γ-globin gene and the promoter region of the murine α-globin gene. The intensity of the murine α gene was used for DNA loading correction. Copy numbers were determined by comparing the signal from a given transgenic line with those of human genomic DNA.

RNA analysis

Total RNA was prepared from tissues containing primitive erythrocytes (day 12 blood and yolk sac) and tissues containing definitive erythrocytes (day 12 fetal liver and adult blood). RNA samples were separately isolated from three or more transgenic individuals from each time point. The human γ-globin was detected by RNase protection assay using an antisense RNA probe containing exon 2 of the gene. The probes for murine α- and ζ-globin mRNA were from exon 1 of the genes. The intensity of the protected bands was quantified with a phosphorimager. To minimize experimental error, samples from individual animals were quantified independently and multiple measurements were performed in RNase protection assays. Copy number-corrected globin mRNA levels were expressed as human γ mRNA/γ copy number/[(murine ζ mRNA/2) + (murine α mRNA/4)].

CMV/cre transgenic mice

The gene for cre recombinase driven by the CMV promoter was released from the plasmid backbone and purified. Transgenic mice were produced as described. The in vivo functionality of the CMV/cre transgene was assessed in mice carrying the βgeo-trapped ROSA26 locus (17). CMV/cre transgenic mice were mated with mice carrying a floxed ROSA26 allele. Pregnancy was terminated at day 15. The fetuses were dissected and stained with the β-galactosidase substrate X-gal. Results showed that all CMV/cre-positive fetuses were blue, indicating that the CMV/cre transgene is functional in mice.

RESULTS

Structural analysis of the transgene

It has been suggested that 5′HS5 of the human β-globin LCR might function as a chromosomal boundary because it is able to block communication between the enhancer and promoter, as shown by enhancer blocking assays (6,12). To test whether 5′HS5 functions as an insulator in vivo we placed a 3.2 kb 5′HS5 fragment on the 5′ and 3′ ends of a γ-globin gene construct, µLCR(–730)Aγ (Fig. 1, construct 5µγ5), and tested the new construct in transgenic mice. The Aγ gene is highly sensitive to position effects in transgenic mice (15,18,19). If 5′HS5 is a chromosomal insulator in vivo, it is expected that 5′HS5 will protect the Aγ gene against position effects.

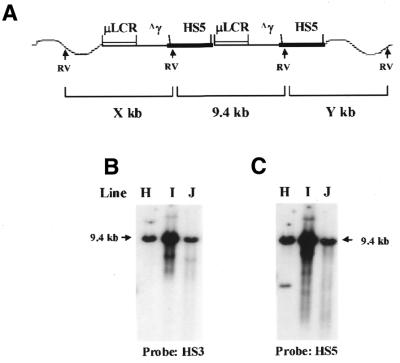

We established seven transgenic lines carrying this construct. Transgene structures and copy numbers were determined by Southern blotting (Fig. 2). When digested with EcoRV, which has a unique site in the 5′HS5 fragment (Fig. 2A), each intact copy of the transgene will release a 9.4 kb internal fragment containing the 5′ copy of 5′HS5, µLCR and the Aγ gene. Figure 2B shows a representative Southern blot of the EcoRV-digested DNA from transgenic mice, after hybridization with a HS3 probe. All seven lines have the 9.4 kb fragment, indicating the presence of intact copies of the construct. In addition to the 9.4 kb band, one or more extra bands are seen in three lines (C, D and G), indicating that rearranged copies coexist with the intact copies in these lines. When 5′HS5 is used as probe (Fig. 2C), three bands should be detected: a 9.4 kb internal fragment, a 3.2 kb conjunction fragment if the transgene is arranged as head-to-tail repeats and an end band derived from the 3′ copy of 5′HS5 and the nearby mouse DNA. Based on this information we are able to deduce the arrangement of the transgene in each line. For example, in line E, when probed with HS3, four copies of the internal fragment (9.4 kb) were detected, while when probed with 5′HS5, four copies of the internal fragment (9.4 kb), three copies of the conjunction fragment (3.2 kb) and one copy of the end fragment were detected (Fig. 2C). These results suggest that the line E transgenic mice carry four copies of the transgene, which are arranged in a head-to-tail array and are integrated in one site in the mouse genome. In line C, probing with HS3 detected one copy of the internal fragment and one rearranged copy (Fig. 2B), while probing with 5′HS5 detected one copy of the internal fragment, two copies of the end fragment and no conjunction fragment (Fig. 2C). The results suggest that in the line C mice only one copy is intact and another copy is defective due to absence of the 5′HS5 fragment and that the two copies are integrated into different sites. In line A there are seven copies of the internal fragment, six copies of the conjunction fragment and four extra bands (Fig. 2C, line A). To determine whether the four extra bands represented four different end fragments or whether some of them could be the rearranged copies, the blot was rehybridized with a γ probe (not shown). Of the four extra bands three hybridized with the γ probe but not with the HS3 probe, suggesting that these three bands represent rearranged copies. Based on this analysis, we conclude that line A contains seven intact copies arranged in a head-to-tail manner integrated in one site of the mouse genome and three rearranged fragments missing at least HS3. Similar analyses were applied to the other lines. These analyses demonstrated that the majority of the copies of the transgene were intact and integrated in the mouse genome as head-to-tail repeats.

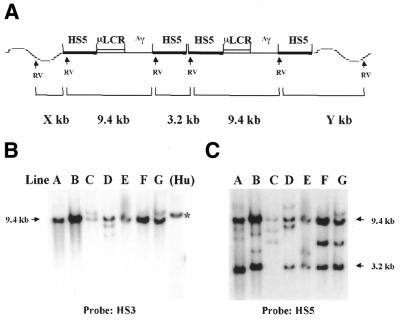

Figure 2.

Structure analysis of the construct 5µγ5 (5′HS5/µLCR/Aγ/5′HS5) in transgenic mice. (A) A diagram representing the structure of a dimer of the construct integrated in the mouse genome. The components of the construct are indicated at the top and the wavy lines represent the mouse DNA. RVs indicate the EcoRV sites in the construct and in the mouse genome. As shown by the diagram, the HS3 probe can detect the 9.4 kb internal fragment, and the 5′HS5 probe can detect the 3.2 kb conjunction fragment and the 3′-end fragment (Y), in addition to the 9.4 kb internal fragment. (B) Southern analysis of the genomic DNA of seven transgenic lines carrying the construct 5µγ5. The DNAs were digested with EcoRV and the blot was hybridized with the HS3 probe. In this Southern hybridization the HS5 probe cannot detect the fragment X from the mouse genome because digestion with EcoRV separates the fragment X from the first HS5 fragment in the construct. The lane marked (Hu) is human genomic DNA digested with EcoRI. The size of the EcoRI band is 10.4 kb (marked with an asterisk). (C) The same Southern blot was hybridized with the 5′HS5 probe. Notice that the 3.2 kb conjunction bands are present in all lines except line C.

5′HS5 protects a position-sensitive transgene from position effects

To quantitate the expression of the 5′HS5 bracketed γ-globin gene in transgenic mice, we measured the level of γ mRNA in adult blood using a quantitative RNase protection assay (Table 1 and Fig. 3A). The levels of γ-globin mRNA (ratio of human γ mRNA to murine α mRNA) are plotted against the copy number of the transgene in Figure 3B. A linear correlation between expression level and copy number is apparent (r = 0.96), indicating that the γ-globin gene escapes from the positive or negative influences of the neighboring chromatin. This is remarkably different from the parental construct, in which the Aγ gene is not bracketed by 5′HS5 and there is no correlation between level of γ gene expression and copy number (r = 0.11; Fig. 3C). The mean level of γ expression in the seven transgenic lines with the bracketed construct is 40.3% of murine α mRNA per copy. This is 5.8-fold higher than the mean in six transgenic lines carrying the non-bracketed construct (6.9% per copy). These results suggest that 5′HS5 is able to shelter a position-sensitive γ-globin gene against position effects.

Table 1. Expression of the γ-globin gene in transgenic mice carrying the construct 5′HS5/µLCR/Aγ/5′HS5.

| Line | Copy no. | Human γ as a percentage of murine α-like mRNA per copy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primitive erythropoiesis | Definitive erythropoiesis | ||||

| Blood (day 12) | Yolk sac (day 12) | Fetal liver (day 12) | Blood (adult) | ||

| A | 7 | 55.5 ± 4.1 | |||

| B | 13 | 44.4 ± 2.6 | 71.5 ± 11.4 | 48.6 ± 4.5 | 40.5 ± 6.5 |

| C | 1 | 62.4 ± 9.1 | 75.2 ± 8.1 | 78.2 ± 22.2 | 30.1 ± 10.5 |

| D | 4 | 28.3 ± 1.8 | 33.9 ± 8.8 | 39.1 ± 8.7 | 47.1 ± 4.1 |

| E | 4 | 27.3 ± 4.0 | 42.7 ± 0.6 | 40.1 ± 13.4 | 42.6 ± 3.3 |

| F | 6 | 39.5 ± 7.6 | 47.4 ± 3.6 | 26.9 ± 3.1 | 19.5 ± 5.0 |

| G | 4 | 38.8 ± 5.4 | 49.2 ± 10.1 | 75.0 ± 12.7 | 46.8 ± 1.2 |

| Mean | 40.1 ± 12.8 | 53.3 ± 16.4 | 51.3 ± 20.8 | 40.3 ± 12.0 | |

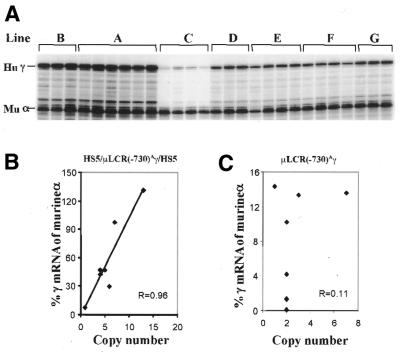

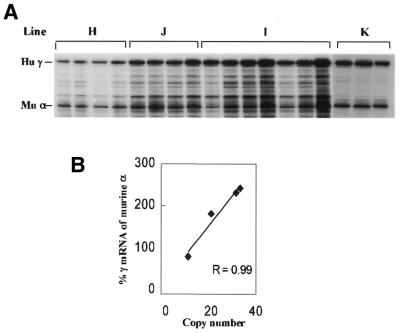

Figure 3.

Expression in the γ-globin gene in the adult blood of transgenic mice carrying the construct 5µγ5. (A) RNase protection assays to measure the levels of the γ-globin mRNA in adult mouse blood. Hu γ, the 170 bp protected fragment from exon 2 of human γ-globin mRNA; Mu α, the 134 bp protected fragment from exon 1 of murine α-globin mRNA. (B) Correlation between γ gene expression and number of transgenes in adult 5µγ5 mice. Notice the excellent correlation between the level of expression and the number of transgenes, demonstrating the copy number dependence of γ gene expression. (C) Correlation between γ gene expression and number of transgenes in mice carrying the parental construct, µLCR(–730)Aγ. The data cited are from our previous publication (15).

To examine whether 5′HS5 can also protect the position-sensitive –730 Aγ-globin gene at the embryonic stage we measured γ gene expression in day 12 blood and yolk sac of transgenic mice (Table 1). Day 12 fetal blood is composed predominantly of nucleated erythrocytes originating from the yolk sac and the day 12 yolk sac still contains large numbers of nucleated embryonic red cells. As shown in Figure 4, a linear correlation between γ mRNA and copy number is apparent (r = 0.98) in both the 12 day yolk sac and blood, indicating that the γ gene is protected from position effects at the embryonic stage.

Figure 4.

Correlation between γ gene expression and number of transgenes at the embryonic stage in adult 5µγ5 mice. (Left) γ Gene expression in day 12 blood. (Right) γ Gene expression in day 12 yolk sac.

Together, these observations suggest that when the γ-globin gene is bracketed by 5′HS5, it is protected from position effects and is expressed at higher levels compared with the non-bracketed gene in both embryonic and adult erythrocytes. These properties are expected if 5′HS5 behaves as a chromatin insulator.

Bracketing is required for function of 5′HS5 as an insulator

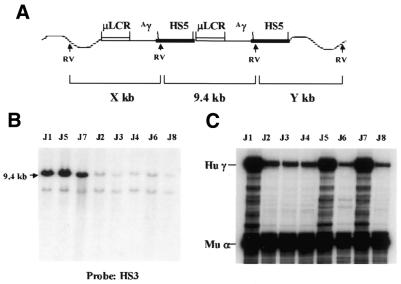

A chromosomal insulator can protect a transgene from position effects only if it is placed on both ends of the gene (5). To further test whether 5′HS5 fits this criterion of chromosomal insulators, we produced a γ-globin gene construct carrying a single copy of 5′HS5 and a loxP site (Fig 1, construct µγ5). When this construct is integrated as a head-to-tail array in the mouse genome, the 5′HS5 fragment will flank both ends of the transgene, except for the most 5′ copy. Four transgenic lines (H–K) carrying this construct were established and Southern blot hybridization was employed to analyze the structure of the transgenes.

Figure 5 shows the analysis in three lines (H–J). When the mouse DNA is digested with EcoRV and probed with 5′HS3 (Fig. 5A), the main band is 9.4 kb long, indicating that the transgene is arranged as a head-to-tail array. There is one 5′-end band in lines H and J and two (or more) extra bands in line I, indicating that the transgene was integrated in a single position in lines H and J, and two (or more) positions in line I. When the blot was probed with 5′HS5 (Fig. 5C), the main band was 9.4 kb, confirming that the transgene is inserted as a tandem repeat. This blot also showed that one 3′-end fragment was present in line H and two (or more) in line I. In line J no end band was detected, most likely because the 3′-end fragment co-migrated with the internal fragment. Copy number measurements support this conclusion. Expression of the γ-globin gene was estimated by RNase protection assays in the adult blood of transgenic mice carrying the construct µγ5 (Fig. 6A). As shown by the plot of γ gene expression versus copy number of the transgene (Fig. 6B) there is an excellent correlation between expression level and copy number in the four lines (r = 0.99). Since the γ gene is bracketed by 5′HS5, this result confirms the observations with the construct 5µγ5, showing that 5′HS5 is able to protect the γ-globin gene against position effects.

Figure 5.

Analysis of structure of the construct µγ5 integrated in the mouse genome. (A) Diagram of a dimer of the construct arranged as a head-to-tail array. The wavy lines represent the mouse DNA. RV, restriction enzyme EcoRV recognition sites. (B) Southern analysis of the genomic DNA of transgenic mice carrying the construct µγ5. The DNAs were digested with EcoRV and the blot was hybridized with the HS3 probe. (C) Southern analysis of the transgenic lines carrying the construct µγ5. The DNAs were digested with EcoRV and the blot was hybridized with the 5′HS5 probe.

Figure 6.

Expression of the γ-globin gene in the blood of adult transgenic mice carrying the construct µLCR/Aγ/5′HS5A (µγ5A). (A) RNase protection assays to measure the levels of γ-globin mRNA in adult mouse blood. Hu γ, the 170 bp protected fragment from exon 2 of human γ-globin mRNA; Mu α, the 134 bp protected fragment from exon 1 of murine α-globin mRNA. (B) Correlation between γ gene expression and number of transgenes in adult µγ5A mice. Notice the excellent correlation between the level of expression and the transgene copy number, demonstrating the copy number dependence of γ gene expression.

Because the construct contains a loxP site, we were able to produce transgenic animals that carry a γ gene linked to a single copy of 5′HS5 by crossing the µγ5 mice with a cre transgenic line. A female mouse of line J was crossed with a male mouse carrying the CMV/cre transgene. One litter with 10 pups was analyzed and the genotype of the offspring was identified by slot blot. In this litter, five animals were double hemizygous for both the CMV/cre and µγ5 constructs, while three animals carried only the µγ5 construct. Analysis of the structure of the µγ5 transgene in each animal is shown in Figure 7A. In µγ5 mice not carrying the cre gene, the copy number of the construct was as in the µγ5 parent. In the five doubly hemizygote mice one copy of the internal fragment and one copy of the end fragment were detected. This result suggests that the cre DNA recombinase reduced the copy number of the transgene from 20 to 2 and the transgene was arranged in a head-to-tail manner.

Figure 7.

Analysis of structure and expression of the γ-globin gene in a litter from a µγ5 transgenic mouse (line J) crossed with a CMV/cre mouse. (A) A schematic diagram showing the structure of a dimer of the construct µγ5 in the mouse genome. Note that only the second γ gene is flanked by the 5′HS5 fragments. (B) Southern blot analysis. Tail DNA from each individual was digested with EcoRV, electrophoresed on a 0.7% agarose gel and hybridized with the HS3 probe. The individual animals are identified as J1–J8. (C) RNase protection assay showing the level of expression of the γ-globin gene in the blood of each animal.

The µγ5/cre transgenes contain one γ gene protected by 5′HS5 and one γ gene unprotected. If the unprotected copy is subject to position effects and on average displays the low γ gene expression level characteristic of the unprotected µLCR(–730)Aγ construct, the per γ gene copy expression in the µγ5/cre transgenic mice is expected to be lower than the level in the 5µγ5 mice. The level of γ mRNA in the µγ5/cre mice fulfills these predictions: γ gene expression in the five µγ5/cre double hemizygotes was 14.5 ± 3.9% per copy, i.e. 50% of the expression in the 5µγ5 hemizygotes. This result is compatible with the interpretation that γ gene expression by the bracketed γ gene of the µγ5/cre animals was as in the bracketed γ gene of the 5µγ5 animals of line J (36.2%), while transcription from the unbracketed γ gene of line I was negligible. Similar results were obtained with line H (data not shown). Therefore, this analysis is consistent with the interpretation that, similarly to other insulators, bracketing is required for function of 5′HS5 as an insulator.

5′HS5 does not possess enhancer activity in vivo

The 5′HS5 fragment we used in the above experiments contains binding sites for multiple transcription factors, including motifs for GATA-1 and NF-E2 (20,21). It has previously been speculated that an enhancer resides in the 5′HS5 region (6). To examine whether the insulating activity of 5′HS5 or an enhancing activity of 5′HS5 is responsible for the uniform expression of the γ gene in all integration events, we tested, in transgenic mice, a construct containing the γ gene linked to 5′HS5 but lacking the µLCR cassette (Fig. 1, construct γ5). We obtained 13 founders carrying this construct (copy number of the transgene ranged from 1 to 49), but in none could we obtain any signal for the transgene as measured by RNase protection assay. Similarly, studies of peripheral blood samples of the adult transgenic mice with anti-γ-globin chain fluorescent antibodies failed to detect any red cells expressing γ globin. From the 13 founders we established five lines and examined γ gene expression in the F2 embryos and adults. No γ-globin gene signal was detected by RNase protection assay in the yolk sac or in adult blood of the five lines, nor could γ-globin be detected in a fluorescent antibody study. We conclude that 5′HS5 does not have significant enhancer capacity in vivo. The high and uniform expression of the γ-globin gene bracketed by 5′HS5 should be attributed to the insulating activity of this element.

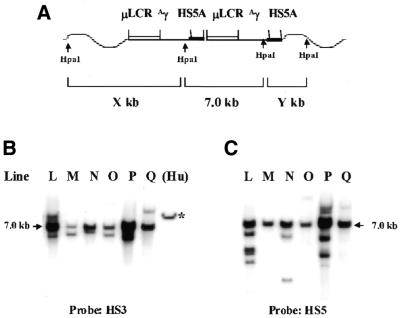

The insulating activity resides in multiple elements of 5′HS5

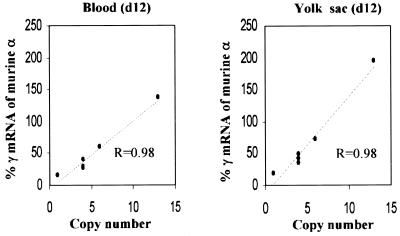

The 3.2 kb 5′HS5 fragment we used in this study contains two regions conserved between human, mouse and galago, which are designated 5′HS5A and 5′HS5B (21). GATA- and NF-E2-binding sites are conserved between the three species, as demonstrated in that study, but whether a CTCF-binding site is present and conserved in this region is still unknown. To determine if the insulating activity is located in only one of these regions or requires elements placed in both conserved regions, we linked µLCRAγ to a 0.8 kb fragment spanning the conserved region in 5′HS5A (Fig. 1, construct µγ5A). Six transgenic lines carrying this construct were established. To determine the structure of the construct in the mouse genome the DNAs were digested with HpaI to completion, blotted and hybridized with the probes HS3 and 5′HS5A, respectively (Fig. 8). From this analysis we could also deduce the copy numbers of the γ-globin gene that were flanked with 5′HS5A in each line. The results are shown in Table 2 along with the measurements of γ-globin expression in the embryos and adults. Transcription of the γ-globin gene in adult blood of the six lines had a range of 83-fold, from 0.3 to 25% of murine α-globin mRNA per copy. The degree of variation of γ expression is similar to that of a µLCR(–730)Aγ construct, indicating that 5′HS5A is unable to protect the γ-globin gene from position effects in the adult. Interestingly, the level of expression of the γ-globin gene in the embryonic stage was relatively consistent in the six lines. In the day 12 blood samples, the level of γ expression had a range of 2.8-fold and in the day 12 yolk sac 3-fold, while γ gene expression in transgenic mice carrying the µLCR(–730)Aγ construct had a range of 26-fold. Thus, in contrast to the adult stage, 5′HS5A is able to protect the γ-globin gene from position effects in the embryos. However, the correlation between γ gene expression and copy number in the 5′HS5A mice is significantly lower than that in the mice carrying full-length 5′HS5 (r = 0.62 versus 0.98).

Figure 8.

Structure analysis of the construct µγ5A in transgenic mice. (A) A diagram representing the structure of a dimer of the construct integrated in the mouse genome. The components of the construct are indicated at the top and the wavy lines represent the mouse DNA. HpaI sites in the construct and in the mouse genome are shown. (B) Southern analysis of the genomic DNA of six transgenic lines carrying the construct µγ5A. DNAs were digested with HpaI and the blot was hybridized with the HS3 probe. The lane marked (Hu) is human genomic DNA digested with EcoRI. The size of the EcoRI band is 10.4 kb (marked with an asterisk). (C) The same Southern blot was hybridized with the 5′HS5 probe.

Table 2. Expression of the γ-globin gene in transgenic mice carrying the construct µLCR/Aγ/5′HS5A or µLCR/Aγ/5′HS5B.

| Line | Copy no. | Human γ as a percentage of murine α-like mRNA per copy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primitive erythropoiesis | Definitive erythropoiesis | ||||

| Blood (day 12) | Yolk sac (day 12) | Fetal liver (day 12) | Blood (adult) | ||

| µLCR/Aγ/5′HS5A | |||||

| L | 8 | 26.4 ± 5.1 | 58.3 ± 7.7 | 44.4 ± 16.9 | 25.0 ± 2.3 |

| M | 2 | 35.6 ± 4.8 | 35.6 ± 4.4 | 23.4 ± 5.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 |

| N | 4 | 45.8 ± 5.4 | 57.0 ± 13.5 | 51.9 ± 4.8 | 19.8 ± 0.3 |

| O | 3 | 18.0 ± 3.5 | 27.6 ± 2.1 | 21.7 ± 3.5 | 0.5 ± 0.2 |

| P | 13 | 16.4 | 24.2 | 15.2 | 3.9 ± 0.7 |

| Q | 6 | 41.6 ± 8.0 | 73.7 ± 6.3 | 16.2 ± 3.5 | 1.9 ± 0.2 |

| Mean | 30.6 ± 12.3 | 46.1 ± 19.8 | 28.8 ± 15.5 | 8.6 ± 10.9 | |

| µLCR/Aγ/5′HS5B | |||||

| R | 3 | 14.0 ± 1.2 | 19.2 ± 1.9 | 15.5 ± 1.2 | 6.6 ± 0.7 |

| S | 1 | 5.9 | 7.4 | 2.2 | 1.2 |

| T | 2 | 6.8 ± 2.3 | 11.2 ± 1.8 | 14.8 ± 1.2 | 0.8 ± 0.7 |

| Mean | 8.9 ± 4.4 | 12.7 ± 5.9 | 10.8 ± 7.5 | 2.9 ± 3.2 | |

To test whether the conserved region 5′HS5B is able to function as an insulator, a 1.3 kb fragment spanning this region was linked to the µLCRAγ construct (Fig. 1, µγ5B). Three transgenic lines carrying this construct were established (Table 2, lines R–T). Structural analysis showed that line R mice carried three copies of the transgene in a head-to-tail array integrated in one site of the mouse chromosome, line S carries a single copy of the transgene and in line T mice two single copies of the transgene are integrated into two different sites (data not shown). Since the γ-globin transgene in lines S and T is not bracketed by the 5′HS5B fragment, its expression in these two mouse lines is subjected to position effects (Table 2). In line R two copies of the γ-globin gene are bracketed by 5′HS5B. γ gene expression in adult blood of this line is 6.6% per copy (Table 2), which is much lower than would be expected from a protected γ gene. Although a firm conclusion cannot be derived on the basis of the findings in these three lines, the results are consistent with the possibility that 5′HS5B is unable to protect the γ gene against position effects.

The lack of protection from position effects in adult animals carrying the 5′HS5A or 5′HS5B transgene suggests that a combination of elements located along 5′HS5 in various locations are required to achieve full insulating activity.

DISCUSSION

Insulating activity is usually detected by two kinds of assay: an enhancer blocking assay and a position effects assay. In the position effects assay insulating activity is manifested by two properties: (i) the variation in per copy expression of a transgene is much smaller among transgenic lines carrying the insulated gene compared with those carrying its uninsulated counterpart; (ii) the average expression level of an insulated transgene is higher than that of its uninsulated counterpart because the position effects in most sites of integration negatively affect gene expression. In this study we show that 5′HS5 is able to protect a position-sensitive gene against position effects. Previous studies have shown that 5′HS5 of the human β-globin LCR is able to block enhancer activity when it is placed between an enhancer and a promoter. Therefore, 5′HS5 meets the criteria that have been used to define other insulator elements (1–5).

There are two pieces of evidence that are incompatible with this conclusion. Zafarana et al. (14) have produced transgenic mice with a β-globin locus construct in which a marked β gene was placed upstream of 5′HS5 of the LCR. This gene was expressed, suggesting that 5′HS5 had failed to block the enhancing activity of the downstream LCR. Although the results of this study have not yet been reported in a peer reviewed publication, these findings have been considered as evidence against the conclusion that the human 5′HS5 site acts as a chromatin insulator. However, this evidence cannot be considered as conclusive because expression of the marked β gene could have been enhanced by an upstream placed enhancer. Indeed, such an enhancer placed upstream of 5′HS5 has been described (22), but whether this enhancer is located upstream of the marked β-globin gene in the construct used by Zafarana et al. cannot be judged from the information provided in their publication.

The second piece of information that can be considered as evidence against an insulator function of 5′HS5 has been obtained with studies in knock-out mice. The sequence of the 5′HS5 region is conserved between man, galago and mouse (20,21). Actually, 5′HS5 is part of a conserved block of ∼40 kb lying between the globin locus and the odorant receptor locus in man and mouse (20). The human and mouse β-globin loci are embedded within an array of odorant receptor genes that are expressed in the olfactory epithelium. It has been reported that knock-out of the mouse 5′HS5 and upstream region does not produce any effects on chromatin structure and expression of the downstream β-globin genes (23,24). In a study by Bender et al. (23) a 3.5 kb region including 5′HS5 and HS6 was deleted in the mouse genome. This deletion had a minimal effect on transcription and did not prevent formation of the remaining HSs of the LCR. Similar results were obtained in a study by Farrell et al. (24) in which an even larger piece of DNA (11 kb), including murine HS4.2, 5′HS5, HS6 and the 5′β1 odorant receptor gene, was knocked out. These observations raise a question: if 5′HS5 functions like an insulator in transgenic mice and in enhancer blocking assays, why does its deletion from the chromosomal mouse β locus fail to produce a phenotype? If the primary in vivo function of this element was to protect the β-globin locus from the influence of the neighboring chromatin and if the region upstream of the 5′HS5 domain is heterochromatic, as studies of thalassemia mutants (reviewed in 25) would suggest, deletion of 5′HS5 would be expected to lead to an alteration in the chromatin environment of the β locus in erythrocytes. Manifestations of this could include repression of globin gene expression in erythroid cells and/or ectopic expression in non-erythroid tissues.

One explanation of the results in the knock-out mice is that the insulating function of the LCR is redundant and multiple elements, including 5′HS5, contribute to the insulation of the locus from 5′ influences. It has been demonstrated that HS2, HS3 or HS4, similarly to the intact LCR, are capable of conferring copy number-dependent expression of a linked gene (reviewed in 26,27), implying that these elements of the LCR possess an inherent insulator-like activity. Thus, removal of 5′HS5 may not necessarily lead to phenotypic effects from the locus. Moreover, when HS2–HS5 of the β LCR are removed, the locus remains in an open chromatin conformation (28,29), indicating that there is an as yet unknown mechanism whereby an open chromatin structure can be established and maintained in the β-globin locus in erythrocytes.

A more plausible explanation of the results with the knock-out mice is that, in contrast to the human 5′HS5, the murine 5′HS5 does not function as a chromatin insulator and perhaps the insulation activity of the murine β-globin locus resides within other upstream elements. In contrast to the murine 5′HS5, the human 5′HS5 appears to be the functional homolog of chicken 5′HS4, which is the prototype of an insulator in vertebrates.

It is interesting that 5′HS5A clearly does not insulate the transgene in adult blood but seems to have insulator function in day 12 embryos. The mechanism underlying this difference is unclear. We speculate that it may reflect a variance in chromatin structure in embryonic and adult cells due to different architectural proteins and the status of histone modification (acetylation, methylation or phosphorytion), or 5′HS5 may bind distinct sets of trans factors in different developmental stages.

NOTE ADDED IN PROOF

Recently it has been shown that a conserved CTCF binding site is present in human 5′HS5 and it has insulating activity in an enhancer blocking assay (30).

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Betty Mastropaolo and Linda Scott for assessing functionality of the CMV/cre transgene using ROSA mice. This research was supported by National Institute of Health grants HL53750 and DK45365.

REFERENCES

- 1.Geyer P.K. (1997) The role of insulator elements in defining domains of gene expression. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 7, 242–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun F.-L. and Elgin,S.C.R. (1999) Putting boundaries on silence. Cell, 99, 459–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Udvardy A. (1999) Dividing the empire: boundary chromatin elements delimit the territory of enhancers. EMBO J., 18, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell A.C., West,A.G. and Felsenfeld,G. (2001) Insulators and boundaries: versatile regulatory elements in the eukaryotic genome. Science, 291, 447–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kellum R. and Schedl,P. (1991) A position-effect assay for boundaries of higher order chromosomal domains. Cell, 64, 941–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chung J.H., Whiteley,M. and Felsenfeld,G. (1993) A 5′ element of the chicken β-globin domain serves as an insulator in human erythroid cells and protects against position effect in Drosophilia. Cell, 74, 505–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bell A.C. and Felsenfeld,G. (1999) Stopped at the border: boundaries and insulators. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 9, 191–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bell A.C., West,A.G. and Felsenfeld,G. (1999) The protein CTCF is required for the enhancer blocking activity of vertebrate insulators. Cell, 98, 387–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forrester W.C., Epner,E., Driscoll,M.C., Enver,T., Brice,M., Papayannopoulou,T. and Groudine,M. (1990) A deletion of the human β-globin locus activation region causes a major alteration in chromatin structure and replication across the entire β-globin locus. Genes Dev., 4, 1637–1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forsberg E.C., Downs,K.M., Christensen,H.M., Im,H., Nuzzi,P.A. and Bresnick,E.H. (2000) Developmentally dynamic histone acetylation pattern of a tissue-specific chromatin domain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 14494–14499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sawado T., Igarashi,K. and Groudine,M. (2001) Activation of β-major globin gene transcription is associated with recruitment of NF-E2 to the β-globin LCR and gene promoter. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 10226–10231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Q. and Stamatoyannopoulos,G. (1994) Hypersensitive site 5 of the human β locus control region functions as a chromatin insulator. Blood, 84, 1399–1401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu J., Bock,J.H., Slightom,J.L. and Villeponteau,B. (1994) A 5′β-globin matrix-attachment region and the polyoma enhancer together confer position-independent transcription. Gene, 139, 139–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zafarana G., Raguz,S., Pruzina,S., Grosveld,F. and Meijer,D. (1994) The regulation of human β-globin gene expression: the analysis of hypersensitive site 5 (5′HS5) in the LCR. In Stamatoyannopoulos,G. (ed.), Hemoglobin Switching. Intercept, Hampshire, UK, pp. 39–44.

- 15.Stamatoyannopoulos G., Josephson,B., Zhang,J.-W. and Li,Q. (1993) Developmental regulation of human γ-globin genes in transgenic mice. Mol. Cell. Biol., 13, 7636–7644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forrester W.C., Novak,U., Gelinas,R. and Groudine,M. (1989) Molecular analysis of the human β-globin locus activation region. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 86, 5439–5443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mao X., Fujiwara,Y. and Orkin,S.H. (1999) Improved reporter strain for monitoring Cre recombinase-mediated DNA excisions in mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 5037–5042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dillon N. and Grosveld,F. (1991) Human γ-globin genes silenced independently of other genes in the β-globin locus. Nature, 350, 252–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Q. and Stamatoyannopoulos,J.A. (1994) Position independence and proper developmental control of γ-globin gene expression require both a 5′locus control region and a downstream sequence element. Mol. Cell. Biol., 14, 6087–6096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bulger M., van Doorninck,J.H., Saitoh,N., Telling,A., Farrell,C., Bender,M.A., Felsenfeld,G., Axe,R. and Goudine,M. (1999) Conservation of sequence and structure flanking the mouse and human β-globin loci: the β-globin genes are embedded within an array of odorant receptor genes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 5129–5134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Q., Zhang,M., Duan,Z. and Stamatoyannopoulos,G. (1999) Structural analysis and mapping of DNase I hypersensitivity of 5′HS5 of the β-globin locus control region. Genomics, 61, 183–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Long Q., Bengra,C., Li,C., Kutlar,F. and Tuan,D. (1998) A long terminal repeat of the human endogenous retrovirus ERV-9 is located in the 5′ boundary area of the human β-globin locus control region. Genomics, 54, 542–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bender M.A., Reik,A., Close,J., Telling,A., Epner,E., Fiering,S., Hardison,R. and Groudine,M. (1998) Description and targeted deletion of 5′ hypersensitive site 5 and 6 of the mouse β-globin locus control region. Blood, 92, 4394–4403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farrell C.M., Grinbery,A., Huang,S.P., Chen,D., Pichel,J.G., Westphal,H. and Felsenfeld,G. (2000) A large upstream region is not necessary for gene expression or hypersensitive site formation at the mouse β-globin locus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 14554–14559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stamatoyannopoulos G. and Grosveld,F. (2000) Hemoglobin switching. In Stamatoyannopoulos,G., Majerus,P.W., Perlmutter,R.M. and Varmus,H. (eds), Molecular Basis of Blood Diseases, 3rd Edn. W.B.Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, pp. 135–182.

- 26.Fraser P. and Grosveld,F. (1998) Locus control regions, chromatin activation and transcription. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 10, 361–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Q., Harju,S. and Peterson,K.R. (1999) Locus control regions: coming of age at a decade plus. Trends Genet., 15, 403–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reik A., Telling,A., Zitnik,G., Cimbora,D.G., Epner,E. and Groudine,M. (1998) The locus control region is necessary for gene expression in the human β-globin locus but not the maintenance of an open chromatin structure in erythroid cells. Mol. Cell. Biol., 18, 5992–6000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Epner E., Reik,A., Cimbora,D., Telling,A., Bender,M.A., Fiering,S., Enver,T., Martin,D.I.K., Kennedy,M., Keller,G. and Groudine,M. (1998) The β-globin LCR is not necessary for an open chromatin structure or developmentally regulated transcription of the native mouse β-globin locus. Mol. Cell, 2, 447–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farrell C.M., West,A.G. and Felsenfeld,G. (2002) Conserved CTCF insulator elements flanks the mouse and human β-globin loci. Mol. Cell. Biol., 22, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]