“I seek a method by which teachers teach less and learners learn more.”

Johann Comenicus, writer of the first illustrated textbook (1630)

Attitudes towards and expectations of careers have changed. Portfolio careers and changing needs in the medical workforce have led, for example, to increasing numbers of postgraduate entrants to medical school, greater movement between specialties, and an influx of qualified doctors from overseas.1–3 Learners with substantial previous experience and knowledge may provide a challenge to trainers to maximise their learning.

Recognising the individuality of the learner is the hallmark of good teaching.4 We explore particular attributes of experienced adult learners and for each attribute propose an educational model that may help the trainer develop an approach to achieve maximum growth. Raised awareness of an individual's learning needs and potential contribution, combined with greater use of these models, will promote a movement away from didactic teaching, which is characterised by an unequal status of teacher and learner, to one of coaching and partnership between learner and trainer, with additional benefit to both.5

To illustrate our points we have used examples taken from the real lives of postgraduate learners in medicine —people who have a substantial amount of previous experience and have changed the direction of their career. The examples illustrate some of the attributes we describe and the relevance of the educational model. As all learners have relevant previous experience and prior understandings that may pass unrecognised, the attributes and related frameworks we describe are, in practice, relevant to all adult learners.6

Summary points

Changes in careers have led to increasing numbers of experienced learners in the workforce

Experienced adult learners clearly display attributes that are present to some extent in all adult learners: maturity, independence, self direction, a desire to contribute, and well developed individuality

The trainer must have a flexible and reflective educational style that is tailored to the individual learner

Relevant educational models emphasise partnership between learner and trainer

The learner brings maturity

Changing career paths and encouragement of lifelong learning have resulted in a wider age range for learners in medicine.2,7,8 Adult learners often bring maturity, which may become evident in greater confidence, self awareness, and problem solving skills.

Education needs to be “learner centred,” and educational models need to be relevant to adult learning. This requires a fundamental change in the role of the educator from that of a didactic teacher to that of a facilitator of learning.9 Box B1 illustrates an approach that is applicable to the education of adults.

Box 1.

The adult learner

- Adults need to know why they need to learn something

- Adults maintain the concept of responsibility for their own decisions, their own lives

- Adults enter the educational activity with a greater volume and more varied experiences than children

- Adults have a readiness to learn those things that they need to know in order to cope effectively with real life situations

- Adults are life centred in their orientation to learning

- Adults are more responsive to internal motivators than external motivators

- Designed for teaching children

- Assigns to the teacher full responsibility for all decision making about the learning content, method, timing, and evaluation

- Learners play a submissive part in the educational dynamics

The learner brings substantial professional and life experience

As well as maturity, experienced learners can bring specialist skills that are transferable between specialties, core skills common to all specialties, and an “outside perspective” drawn from other cultures which is useful to the development of empathy.11

The transferable learning experience of health professionals includes:

Increased self awareness, and experience of working in teams

Life experience and knowledge of other cultures

Consultation techniques and relevant specialist knowledge

Management experience and knowledge of the NHS.

Our stories of two postgraduate entrants to medical school illustrate the substantial amount of relevant experience they both acquired beforehand and differences in the way this was valued in their subsequent medical education (box B2).

Box 2.

Experiences of two postgraduate entrants to medical school

Experience is at the heart of adult learning, both in the sense of a property of the individual (“he has bags of experience”) and in the sense of the process of enactment by which one learns (“you won't understand what I mean until you experience it for yourself”).12

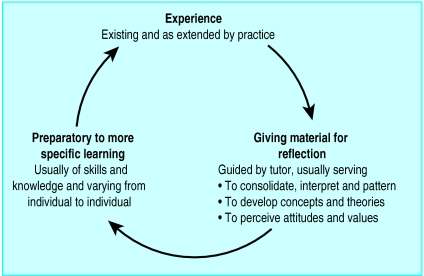

The central importance of learning through experience is illustrated in figure 1. The learning cycle has three phases. It starts with the experience of the learner and leads to the specific learning that occurs on the basis of that experience and the reflective activities, guided by the tutor, that are needed to extract specific learning from the overall experience.13

Figure 1.

Experience as the driving force for reflection and learning (Further Education Unit model13)

The learner is self directed

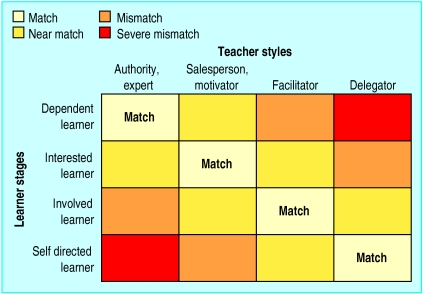

Experienced adult learners are likely to have a self directed learning style. The development of independent learners is well grounded theoretically.14 The style of the trainer needs to be matched to that of the learner to ensure confidence and enthusiasm for learning.

Gerald Grow has proposed a model that allows teachers to develop and adapt their style to match that of the learner.15 The model illustrates how the expert, authoritative style is severely mismatched with that of the self directed learner (fig 2).

Figure 2.

Matching learner stages to teacher styles (Gerald Grow, 1991)15

The model should be seen as dynamic rather than static. Neither learner nor teacher should be trapped at any stage: as the learner moves the teacher must likewise change gear. Valuing learners' expertise as it accumulates and supporting them taking responsibility for identifying their own educational needs add to a process of empowerment that is recognised as important for promoting lifelong learning.5,9

The learner makes a positive contribution

Learners can often make an active and positive contribution to their organisations, as illustrated by both Laura and Sara, and learners may be an untapped resource (box B3). If encouraged, learners can enrich the “educator's” experience, as well as providing additional skills that, for example, may help develop the trainer's own practice.

Box 3.

Learners making a contribution to their organisations

A career portfolio does not always follow the path of upward progression.16 Learners may move from a position of seniority and competence to one of greater dependency and increased vulnerability as new skills are learnt. Laura and Sara illustrate a contrasting reaction from trainers in moving between general practice and public health. For the teacher to be learner centred, it is crucial to engender in the learner a feeling of being valued.5

Didactic teaching is, by definition, characterised by giving instruction. It depends on according a status to the teacher that is at a different level from that of the learner. Almost implicit in the term is a transaction from parent to child, rather than from adult to adult.17

All learners are individuals

The examples of real case scenarios show the great variety of skills, knowledge, and experience that mature learners present. A critical task is to help the learner in constructing a personal learning plan, a process that entails formative appraisal and rigorous assessment of educational needs.18 This is the foundation of individual learning, but it may be at odds with the learning of a peer group.

Applying a different approach

The people in our vignettes illustrate attributes of maturity, experience, independence, untapped resource, and individuality. We believe that these are attributes of all adult learners, and an awareness of these requires a flexible and reflective approach from the educator.

Much is made of “paternalism” in the relationship between doctor and patient.19 Paternalism in the educational relationship between student and trainer is likely to cause adult learners great discomfort. It may affect their learning, motivation, and effectiveness and reduce their overall contribution.20 Trainers may lose out in the learning and satisfaction offered by a two way educational relationship.

Just as input from patients can modify paternalistic consulting behaviours so feedback from learners can help teachers.21 Determinants of a positive partnership between learner and trainer are based on each party valuing the contribution of the other and a flexible interaction from adult to adult that is determined by the needs of the learner and his or her personal learning plan. Reflection by both the learner and the trainer is key.22 It is how the learner learns rather than what the trainer teaches that is important (table).

Conclusions

We recognise that the NHS workforce has many experienced learners, and they will assume greater importance in the context of the NHS Plan.23 If the target for additional doctors is to be achieved it will be essential to encourage doctors to return to practice; these doctors will, by definition, be mature.

Appropriate models of adult education are models that emphasise a facilitative approach, guided reflection, learning from experience, and an adult to adult relationship between learner and trainer. In addition to education focused on groups, the learning needs of individuals need to be catered for and their wider experience acknowledged and used. Paternalism in an adult educational relationship is rarely appropriate.

Any move towards common standards in education must not obscure the need for medical educators to remain flexible and agile in responding to different learners' needs. Educators need to improve their skills in facilitation, judicious application of educational theory, and mentoring. We believe that moving in this direction makes the educator's job more rewarding and the learner's more fruitful.

Table.

Adult learners and relevant educational models

| Learner's attributes

|

Determinants of a positive partnership

|

Models to help

|

|---|---|---|

| Maturity | Mutual respect independent of age | Adult learning |

| Experience | The learner brings a breath of relevant experience | Further education unit model |

| Self directed learning | The learner is responsible for their own learning with the teacher's support | Matching learner stages to teacher styles |

| Positive contribution | Both teacher and learner enjoy learning from each other | Transactional analysis in adult to adult mode |

| Individuality | The teacher's approach can be adapted | Personal development planning |

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the contribution that learners and their experiences have made to our thinking—some of these are described in our vignettes with altered identities. We thank Philippa Moreton and Richard Stott for their support and encouragement.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Hutchinson L, Hughes P, McCrorie P. Graduate entry programmes in medicine. BMJ. 2002;324:28. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ebrahim S. Demographic shifts and medical training. BMJ. 1999;319:1358–1360. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7221.1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welsh C. Training overseas doctors in the United Kingdom. BMJ. 2000;321:253–254. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7256.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jonassen D, Grabowski B. Handbook of individual differences: learning and instruction. Hillsdown, NJ: Erlbaum; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen N. Mentoring adult learners: a guide for educators and trainers. Melbourne, FL: Krieger; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brookfield S. Adult Learning: an overview. In Tuinjman A, ed. International encyclopedia of education. Oxford: Pergamon; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lambert T, Goldacre M, Evans J. Views of junior doctors about their work: survey of qualifiers of 1993 and 1996 from United Kingdom medical schools. Med Educ. 2000;34:348–354. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woodall A, Pickard M. Mature entrants to medicine. BMJ. 1997;315:2. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spencer J, Jordan R. Learner centred approaches in medical education. BMJ. 1999;318:1280–1283. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7193.1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knowles S, Holton E, Swanson R. The adult learner: the definitive classic in adult education and human resource development. 5th ed. Houston: Gulf Publishing; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charon R. Narrative medicine: a model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. JAMA. 2001;286:1897–1902. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.15.1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brookfield S. Understanding and facilitating adult learning. San Francisco: Josey Bass; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 13.British Further Education Council. Experience, reflection, learning. London: Further Education Unit, Curriculum and Development Unit; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engestrom Y. Development as breaking away and opening up: a challenge to Vygotsky and Piaget. San Diego: University of California; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grow G. Teaching learners to be self-directed. Adult Educ Q. 1991;41:125–149. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allen I. Doctors and their careers. London: Policy Studies Institute; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berne E. Transactional analysis in psychotherapy. New York: Grove; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bahrami J, Rogers M, Singleton C. Personal education plan: a system of continuing medical education for general practitioners. Educ Gen Pract. 1995;4:342–345. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coulter A. Paternalism or partnership? Patients have grown up—and there's no going back. BMJ. 1999;319:719–720. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7212.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Langford F. Successful international adult education programs. Annual Meeting of the American Association for Adult and Continuing Education, Washington, DC, October 1987.

- 21.Elwyn G, Edwards A, Gwyn R, Grol R. Towards a feasible model for shared decision making: focus group study with general practice registrars. BMJ. 1999;319:753–756. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7212.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peile E, Easton G, Johnson N. The year in a training practice: what has lasting value? Grounded theoretical categories and dimensions from a pilot study. Med Teacher. 2000;23:205–211. doi: 10.1080/01421590020031138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Department of Health. The NHS Plan. A plan for investment. A plan for reform. London: Stationery Office; 2000. www.doh.gov.uk/nhsplan/ (accessed 3 Jul 2002). [Google Scholar]