Abstract

Understanding cell destiny requires unraveling the intricate mechanism of gene regulation, where transcription factors (TFs) play a pivotal role. However, the actual contribution of TFs, that is TF activity, is not only determined by TF expression, but also accessibility of corresponding chromatin regions. Therefore, we introduce BIOTIC, an advanced Bayesian model with a well-established gene regulation structure that harnesses the power of single-cell multi-omics data to model the gene expression process under the control of regulatory elements, thereby defining the regulatory activity of TFs with variational inference. We demonstrated that the TF activity inferred by BIOTIC can serve as a characterization of cell identity, and outperforms baseline methods for the tasks of cell typing, cell development tracking, and batch effect correction. Additionally, BIOTIC trained on multi-omics data can flexibly be applied to the scenario where merely single-cell transcriptome sequencing is available, to infer TF activity and annotate the cell type by mapping the query cell into the reference TF activity space, as an emerging application of cell atlases. The structure of BIOTIC has been determined to be adaptable for the inclusion of additional biological factors, allowing for flexible and more comprehensive gene regulation analysis. BIOTIC introduces a pioneering biological-mechanism-driven framework to infer TF activity and elucidate cell identity states at gene regulatory level, paving the way for a deeper understanding of the complex interplay between TFs and gene expression in living systems.

Keywords: single-cell, multi-omics, transcriptional factor, variational inference, TF activity, gene regulatory

Introduction

Gene regulation dictates the expression of genes within a cell across varying developmental stages and tissue types, thereby molding the cell’s specific attributes and functionalities [1]. This regulation is governed by a complex, hierarchical system influenced by various genomic and transcriptomic elements [2]. Among these elements, transcription factors (TFs), chromatin accessibility, and the interactions between TFs and genes collaboratively shape the unique gene expression profiles and specific phenotypes of individual cells through elaborate regulatory pathways [3, 4].

TFs play a pivotal role in gene regulation [5]; however, the complex regulatory mechanisms makes it difficult to fully characterize the contributions of TFs to gene expression regulation. Characterizing cell identity is fundamental for understanding cell functions and fates across different types and lineages [6]. TF activity, which refers to the extent of its regulatory influence on target genes within a given cell, has been proposed as a means to characterize cell identity [7]. TF activity, representing the actual contribution of TFs to gene regulation, serves as a causal factor rather than merely reflecting outcomes such as TF expression levels.

High-throughput techniques such as microarrays and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) have provided opportunities to estimate the status of molecular processes, including the activity of pathways or TFs [8]. GO-GSEA (Gene Ontology-Gene Set Enrichment Analysis) tools [9, 10] combine Gene Ontology (GO) annotations with enrichment patterns to indirectly infer activity. PROGENy [11] considers the impact of post-translational modifications when inferring pathway activity using bulk RNA-seq data, integrating data from perturbation experiments.

With the development of single-cell transcriptome sequencing (scRNA-seq) technology, tools have been developed to infer cell-type-specific TF activity from single-cell data. BITFAM [12] employs Bayesian inference to combine gene expression values with known relationships between TFs and target genes to infer TF activity and regulatory networks. VIPER [13] uses a network-based approach to infer TF activity through the expression levels of target genes. SCENIC [14] infers the activity of gene sets and TF pathways by comparing differential gene expression across various cellular states.

scRNA-seq data captures the expression levels of TFs and their corresponding target genes within cells but lacks information regarding chromatin state. Single-cell Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin sequencing (scATAC-seq) data provide evidence of the effects of TFs on chromatin, making them widely used for assessing gene activity including TF genes. MAESTRO [15] calculates the activity of TFs and genes based on the distance between genes and open regions on the chromosomes. Signac [16] assesses gene activity based on the number of open chromatin regions within gene ontology or promoter regions.

Current studies generally estimate TF activity based on single-modal omics data. However, single-omics data are insufficient to capture the complete regulatory landscape and quantify the true contribution of a TF during gene regulation. Multi-omics sequencing techniques enable the portrayal of regulatory processes by measuring various signals within individual cells [17], facilitating an in-depth exploration of the collaborative mechanisms among TFs and other regulatory elements [18]. Multiple methods have been developed for characterizing cell identity by integrating multi-omics data. Cobolt [19] and MultiVI [20] both combines probabilistic modeling with variational autoencoders to extracts co-embeddings for single cells. single-cell Multi-View Profiler (scMVP) [21] integrates multimodal variational autoencoder models with Transformer networks. scJoint [22] employs transfer learning and nearest-neighbor approaches, while Graph-Linked Unified Embedding (GLUE) [23] applies graph-linked unified embeddings to achieve multi-omics integration. However, these methods primarily focus on mathematical co-embeddings of datasets without explicitly modeling the biological regulatory mechanisms underlying gene expression, overlooking the inherent biological connections and yielding embeddings that lack clear biological implications. Currently, there is a notable absence of methods capable of estimating TF activity by deciphering gene regulation mechanisms, a complex process which is encompassed by three fundamental factors: TFs, chromatin accessibility, and the interactions between TFs and genes, based on multi-omics data.

To address these challenges, we develop BIOTIC, a Bayesian framework to integrate single-cell multi-omics for TF activity inference and improve identity characterization of cells. BIOTIC integrates TF expression levels, TF-region interactions, and chromatin accessibility from multi-omics data to construct a Bayesian framework for optimizing the estimation of TF activity. Serving as a characterization of cell identity, the TF activity inferred by BIOTIC effectively overcomes the distraction of batch effect [24] and preserves cellular heterogeneity, indicating its potential application in various downstream tasks. The experimental results indicate that TF activity inferred by BIOTIC outperforms the baseline cell representations, including embeddings on the whole transcriptome, TF expression, integration of multi-omics, TF activity obtained by other models in multiple downstream tasks, including cell typing, cell differentiation tracking and batch effect correction. Overall, BIOTIC provides novel insights by integrating regulatory mechanism into modeling, allowing for the inference of TF activity to characterize cells. Additionally, BIOTIC trained on multi-omics data can infer TF activity in scenarios where ATAC-Seq data is unavailable for the same cell type from different experiments, showing that BIOTIC captures the essential mechanism and demonstrates its broad applicability in cell mapping.

Methods

BIOTIC is a variational Bayesian method that integrates a deep generative model with a probabilistic graphical structure. In BIOTIC, the inference process learns the parameters of variational distributions of TF activity and TF-gene regulatory weight in the latent space. The model’s generative process produces gene expression levels by learning the function from TF activity and TF-gene regulatory weight to observable space. Specifically, BIOTIC employs a sophisticated framework that combines an advanced deep generative model with a probabilistic graphical structure, to facilitate the elucidation of both the inference and generative processes, where all nonlinear transformations are accomplished by neural networks.

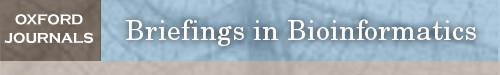

The motivation behind BIOTIC is illustrated in Fig. 1a, which is established on the mechanism of gene regulation, inferring unmeasurable TF activity from multi-omics data. The gene expression is a multifaceted process, where the accessible chromatin regions and the existence of TFs enable the binding from TFs to the target CREs (Cis-regulatory elements) [17, 25]. Chromatin regions with increased accessibility are more likely to attract TF binding [26]. Higher concentrations of TFs indicate a stronger binding affinity to target CREs [27], which signifies enhanced regulatory control and higher activity over the target genes. Gene expression levels can therefore be modeled as the result of this regulating process based on TF activity, CRE accessibility, and TF-gene regulatory relationship. This generation process produces gene expression level  of a specific cell, denoted as

of a specific cell, denoted as  , where

, where  is region accessibility score,

is region accessibility score,  is TF activity and

is TF activity and  is TF-gene regulatory weight matrix, as GRN represents gene regulatory network. Meanwhile, the inference of TF activity can be considered as solving the function

is TF-gene regulatory weight matrix, as GRN represents gene regulatory network. Meanwhile, the inference of TF activity can be considered as solving the function  when gene expression

when gene expression  , region accessibility

, region accessibility  and TF-gene regulatory relationship

and TF-gene regulatory relationship  are partly available. BIOTIC solves the function

are partly available. BIOTIC solves the function  via inference process, which is variational inference to infer the distribution parameters of the latent variables in the manifold space, denoted as

via inference process, which is variational inference to infer the distribution parameters of the latent variables in the manifold space, denoted as  . The framework of BIOTIC is implemented by a Bayesian model consisting of a generation process and a variational inference process, as shown in Fig. 1b. The inferred cell-specific TF activity can be applied to depict cell identity for the following cell typing, drug perturbation tracking, cell differentiation tracking, and batch effect correction, as shown in Fig. 1c.

. The framework of BIOTIC is implemented by a Bayesian model consisting of a generation process and a variational inference process, as shown in Fig. 1b. The inferred cell-specific TF activity can be applied to depict cell identity for the following cell typing, drug perturbation tracking, cell differentiation tracking, and batch effect correction, as shown in Fig. 1c.

Figure 1.

Framework of BIOTIC. (a) BIOTIC is constructed on the mechanism that gene expression is regulated by several key factors: TF activity, TF-gene regulatory weights, and chromatin accessibility. It infers TF activity from multi-omics data. (b) BIOTIC triggers the generation process for gene expression profile and leverages multi-omics data to learn TF activity within cells. Each distinct border color represents one factor. (c) BIOTIC is capable of being applied to a variety of downstream tasks by accurately characterizing cell states from a regulatory perspective.

The input of BIOTIC includes gene aligned-read count matrix  from scRNA-seq, region accessibility score matrix

from scRNA-seq, region accessibility score matrix  from scATAC-seq, and reference TF-gene matrix

from scATAC-seq, and reference TF-gene matrix  . The details of the pre-processing procedure of transforming raw data to the standard input can be found in Additional file 3: Content S1, and the preprocessing code are provided in the Availability of data and materials section. To avoid confusion,

. The details of the pre-processing procedure of transforming raw data to the standard input can be found in Additional file 3: Content S1, and the preprocessing code are provided in the Availability of data and materials section. To avoid confusion,  and

and  represent the variables for gene expression and region accessibility, while

represent the variables for gene expression and region accessibility, while  and

and  denote the observable matrices used in neural networks in the following sections.

denote the observable matrices used in neural networks in the following sections.

Generative process

In BIOTIC, the generation process of gene expression  integrates latent variables region accessibility score

integrates latent variables region accessibility score  , TF-gene regulatory matrix

, TF-gene regulatory matrix  , TF activity

, TF activity  , cell type

, cell type  , and library size

, and library size  .

.  is assumed to follow a Dirichlet-multinomial distribution [28]. Thus, the generation process of gene expression profile

is assumed to follow a Dirichlet-multinomial distribution [28]. Thus, the generation process of gene expression profile  can be formulated with

can be formulated with

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

where  is the distribution parameter learned by nonlinear transformation

is the distribution parameter learned by nonlinear transformation  .

.

The distributions of the corresponding latent variables, as well as their initializations, are introduced as follows:

TF activity variable  initially follows a standard normal distribution with a mean of zero and a variance of I,

initially follows a standard normal distribution with a mean of zero and a variance of I,

|

(3) |

Cell type  is introduced as the auxiliary information to deliver cell type specificity to

is introduced as the auxiliary information to deliver cell type specificity to  ,

,

|

(4) |

Gene-level region accessibility score  is derived from

is derived from  .

.  that reflects the cell type-specific TF-gene regulatory weight is primarily generated based on

that reflects the cell type-specific TF-gene regulatory weight is primarily generated based on  ,

,

|

(5) |

Additionally, the positive-valued library size  is embraced, following a Weibull distribution,

is embraced, following a Weibull distribution,

|

(6) |

where the shape parameter  influences the skewness of the Weibull distribution, and

influences the skewness of the Weibull distribution, and  is the scale parameter [29].

is the scale parameter [29].

Inference process

In the inference process, the distribution parameters used in the generation process are inferred from the observable data, including  from scRNA-seq,

from scRNA-seq,  from scATAC-seq, and cell type

from scATAC-seq, and cell type  .

.

Specifically, the constructed distribution  is learned through a nonlinear transformation

is learned through a nonlinear transformation  , as

, as  estimates parameters of

estimates parameters of  based on the observed data, where

based on the observed data, where  represents the parameter set in the constructed distributions and all neural networks in the inference process. Taking

represents the parameter set in the constructed distributions and all neural networks in the inference process. Taking  as an example: the constructed distribution

as an example: the constructed distribution  is used to infer TF activity

is used to infer TF activity  by inferring

by inferring  and

and  from gene expression profile variable 𝑒 with

from gene expression profile variable 𝑒 with  and the gene expression profile

and the gene expression profile

|

(7) |

|

(8) |

|

(9) |

Similarly, the constructed distribution  and

and  are used to infer the TF-gene regulatory weight

are used to infer the TF-gene regulatory weight  and the library size

and the library size  from gene expression profile variable

from gene expression profile variable  as follows:

as follows:

|

(10) |

|

(11) |

|

(12) |

|

(13) |

|

(14) |

|

(15) |

and

and  are used to infer the cell type labels

are used to infer the cell type labels  from

from  and

and  as follows:

as follows:

|

(16) |

|

(17) |

|

(18) |

During the inference process, the parameters of used distributions can be extracted from the observed data, providing prior support for the generation process.

Loss function and parameter optimization

BIOTIC is a Bayesian-based probability model where the parameters are optimized through variational inference with the Adam optimizer [30]. To approximate the true distribution  , the variational distribution is defined as

, the variational distribution is defined as  , which can be decomposed as follows:

, which can be decomposed as follows:

|

(19) |

Variational inference replaces the intractable marginal likelihood  with variational lower bound, and estimates the intractable integrals with low-variance Monte Carlo estimates, i.e., the reparameterization, which enables effective maximization of the evidence lower bound (ELBO). As a result, the data generated by the latent variables can be accessible to the real data by maximizing ELBO. In BIOTIC, the transformation of maximizing the log-likelihood into maximizing the ELBO through variational inference can be formulated as follows:

with variational lower bound, and estimates the intractable integrals with low-variance Monte Carlo estimates, i.e., the reparameterization, which enables effective maximization of the evidence lower bound (ELBO). As a result, the data generated by the latent variables can be accessible to the real data by maximizing ELBO. In BIOTIC, the transformation of maximizing the log-likelihood into maximizing the ELBO through variational inference can be formulated as follows:

|

|

|

(20) |

where

|

|

(21) |

LELBO is composed of expected data likelihood, i.e. the reconstruction loss, and the KL divergence between the prior distribution and the constructed posterior distribution. To reserve the cell type specificity,  , which measures the loss between known cell types and predicted cell types using cross-entropy, is added to the overall loss function of BIOTIC, as follows:

, which measures the loss between known cell types and predicted cell types using cross-entropy, is added to the overall loss function of BIOTIC, as follows:

|

|

|

|

(22) |

where γ is a hyper parameter that controls the weight of the cell type specificity loss in the overall loss.

Experiment

Datasets and baselines

Seven datasets obtained by multiple sequencing techniques are adopted to demonstrate the superior performance of TF activity inferred by BIOTIC to represent cell identity in different biological scenarios. Summaries about these datasets are given in Additional file 2: Table S1. Five multi-omics datasets were used to evaluate the performance of TF activity in characterizing cell identity by cell typing and batch effect correction. Specifically, scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq data from various tissue compartments, including Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell (PBMC) [23], Bone Marrow Mononuclear Cell (BMMC) [31], Lymph node [32], Skin [33], and Cerebral cortex [34], were analyzed. The BMMC dataset includes batch effects arising from donor variability and differences in sampling sites, while the Skin dataset contains batch effects due to variations in sampling batches. Both datasets were used to evaluate batch effect correction performance. Additionally, A549 [35], a longitudinal time-series dataset of cell evolution, and 1469 [34], a subset of the Cerebral cortex cell differentiation data, including scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq, are used to evaluate the performance of TF activity in characterizing cell identity by distinguishing between cell evolution stages and tracking cell differentiation trajectories. The PBMC-IFNB [36] dataset, which consists only scRNA-seq data from both normal Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) and PBMCs stimulated with Interferon beta (IFNB), was used to evaluate the generalization ability of BIOTIC as a pre-trained model.

The performance of TF activity inferred by BIOTIC for cell characterization was evaluated against activity inferred by two activity inference approaches based on single-omics data (MAESTRO [15] and Signac [16]), as well as embeddings derived from four multi-omics integration approaches (MultiVI [20], Cobolt [19], scMVP [21], and scJoint [22]). To further illustrate that the inferred TF activity extends beyond gene expression, TF activity was compared with the embeddings of high variability genes expression and TF expression obtained by Seurat [37], aiming to intuitively display the difference between TF activity and expression values. The Seurat method applied to gene expression data is denoted as “SeuratGene”, and the method applied to TF expression data as “SeuratTF”. Due to the absence of the required fragment files, Signac and scJoint were only applicable to the PBMC and Lymph node datasets. Additionally, scJoint requires cell type labels during the training process. Details of the performance evaluation metrics are described in Additional file 3: Content S2.

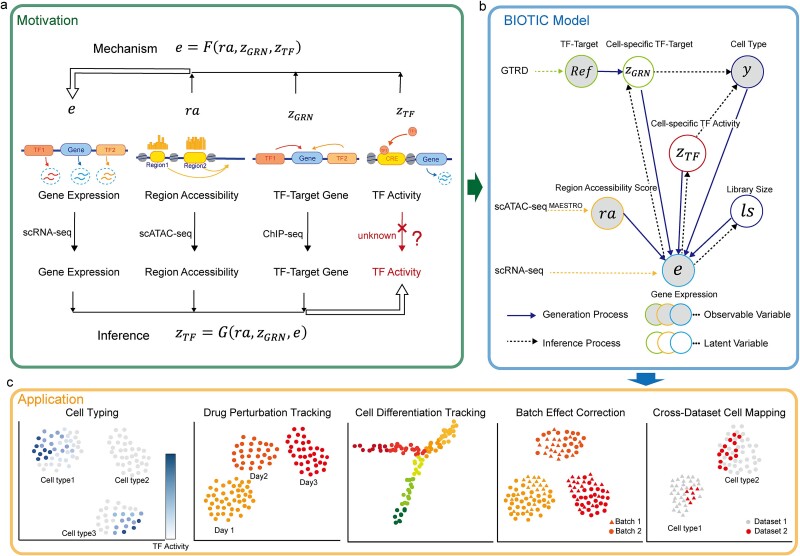

TF activity improves the characterization of cell heterogeneity

Cell typing is the most basic task to evaluate the characterization of cell identity. BIOTIC was applied to obtain TF activity on the five datasets, PBMC, Lymph node, Skin, Cerebral cortex and BMMC. Eight baseline models are included for comprehensive evaluation in cell typing task. Due to the absence of the required fragment files, Signac and scJoint were only applicable to the PBMC and Lymph node datasets. The clustering was performed by Louvain [38] according to the standard pipeline of MultiVI [20], and evaluated by Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) and Purity [39] (Additional file 2: Table S2).

The cell clustering on the PBMC dataset in Fig. 2a demonstrate that BIOTIC exhibits the most distinctive cell clusters that are consistent with cell type annotations among all the methods. Moreover, the visualization results of TF activity are similar to the results of SeuratTF, MAETRO and Signac, which disperse cells that were originally tightly grouped on result of SeuratGene, whereas MAETRO and Signac struggle to clearly differentiate between various cell types. Conversely, multi-omics integration techniques such as scMVP and MultiVI tend to enhance model classification accuracy by aggregating cells of the same type more tightly. The comparison of gene expression and TF activity of specific TFs in the PBMC dataset can be found in Additional file 1: Fig S1, which shows the association between the inferred TF activity and TF expression values. The performance of BIOTIC on the PBMC dataset under different hyperparameter settings can be found in Additional file 2: Table S4, which demonstrates the robustness of BIOTIC. The visualization results on other datasets are presented in Additional file 1: Figs S1–S3, consistently showcasing the typing ability of BIOTIC.

Figure 2.

(a) Visualization of clustering results comparing BIOTIC with baseline methods, with colors representing the true labels of the PBMC dataset. BIOTIC effectively disperses latent variables in accordance with the distributions of various cell types. (b) Comparison of ARI values and purity scores achieved by BIOTIC and baseline methods across five datasets.

Moreover, BIOTIC achieves the highest ARI and Purity among all the methods for all the testing datasets, as shown in Fig. 2b. BIOTIC outperformed the second-best methods by over 15% in both ARI and Purity on the Lymph Node dataset. However, the performance of TF activity inferred through scATAC-seq and the expression levels of TFs is limited. Regarding ARI and Purity, BIOTIC outperforms all the baseline methods across five datasets. Importantly, the significant difference between the visualizations based on TF activity and SeuratTF further indicates that TF activity has inherent biological implications compared to expressions. The result stresses that by integrating multi-omics data and regulatory mechanisms into the model, TF activity inferred by BIOTIC provides a more precise characterization of cell states by capturing regulatory changes within cells. This approach improves upon conventional expression analysis and single-omics TF inference by providing a more comprehensive view of cellular regulation.

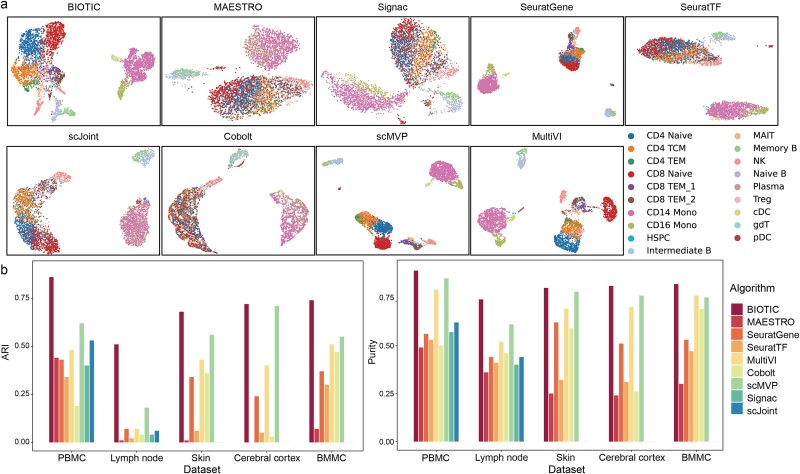

TF activity models the temporal variability among cells

Among developmental cells, the temporal dynamics of perturbed cells of the same type, along similar differentiation trajectories, are characterized as ordered and continuous processes [40]. These dynamics are subtler and more gradual than the differences observed between distinct cell types, making the evaluation of cell identity characterization more rigorous. The A549 dataset contains scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq data from the cell line of human non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), treated with Dexamethasone (DEX) and sampled at three distinct time points (0, 1, and 3 h) [35]. TF activity inferred by BIOTIC was employed to characterize cells at different time stages, to compare with the aforementioned baseline methods. As shown in Fig. 3a, BIOTIC not only effectively separates cells into distinct groups, but also reflects the order of three sampling times. In contrast, the baseline methods exhibit a mingling of cells from different time points and struggle to capture the temporal variations associated with the DEX perturbation.

Figure 3.

Performance comparison in capturing temporal variation of cells. (a) The visualization of clustering results on A549 dataset between BIOTIC and baseline methods. BIOTIC effectively clusters cells on distinct time stages after drug perturbation. (b) The boxplot of the within-cluster distance and between-cluster distance for seven methods. (c) The bar plot of the silhouette coefficients for seven methods. (d) The differentiation trajectory analysis conducted on the 1469 dataset, cells are colored according to cell type and pseudo-differentiation time.

The within-cluster and between-cluster distances among cells collected at various time points were calculated for quantitative comparison, where the within-cluster distance evaluates the gathering degree of cells collected at the same time, and the between-cluster distance measures the distinctiveness of cells collected at different time points. As illustrated in Fig. 3b, BIOTIC significantly reduces within-cluster distances and increases between-cluster distances compared to other methods. It indicates that TF activity characterizes the essential feature of cell state, allowing it to capture both the common information within cells from the same time point and the subtle differences between cells from different time points. Therefore, BIOTIC effectively groups cells collected at the same time, distinguishes cells collected at different time points, and arranges the spatial relationship among groups to reflect the order of collection. Moreover, the Silhouette coefficients bar plot in Fig. 3c consistently demonstrates that BIOTIC exhibits superiority in the cohesion of cells within their respective clusters and the separation from other clusters.

BIOTIC excels in capturing these temporal variations, maintaining within-cluster compactness, and enhancing between-cluster distinctions, showcasing BIOTIC’s capability to accurately capture time-induced nuanced dynamics while effectively mitigating the influence of unrelated signals inherent in multi-omics data.

Differentiation trajectory analysis was further performed on the 1469 dataset, a subset of the Cerebral cortex dataset [41]. It measured 1469 cells on the differentiation trajectory from intermediate progenitors to upper-layer excitatory neurons, where the expected cell trajectory is linearly going through “IP-Hmg2” → “IP-Gadd45g” → “IP-Eomes” → “Ex23-Cntn2” → “Ex23-Cux1” [42]. As shown in Fig. 3d, cells characterized by TF activity are arranged along their differentiation trajectories, while those characterized by SeuratGene and SeuratTF are inseparable. In the lower panel of Fig. 3d, cells were colored by the pseudo time orders calculated from TF activity, embeddings of SeuratGene and SeuratTF by Palantir [43], respectively. Notably, the pseudo time order of cells calculated from TF activity are consistent with the expected linear trajectory. These results indicate that TF activity can uncover the differentiation trajectories within cell lineages, better than using gene expressions or TF expressions.

The results above corroborate that by incorporating gene regulatory mechanism and technological factors into model design, TF activity inferred by BIOTIC can effectively embed the temporal variation information among cells, contributing to better trajectory analysis results.

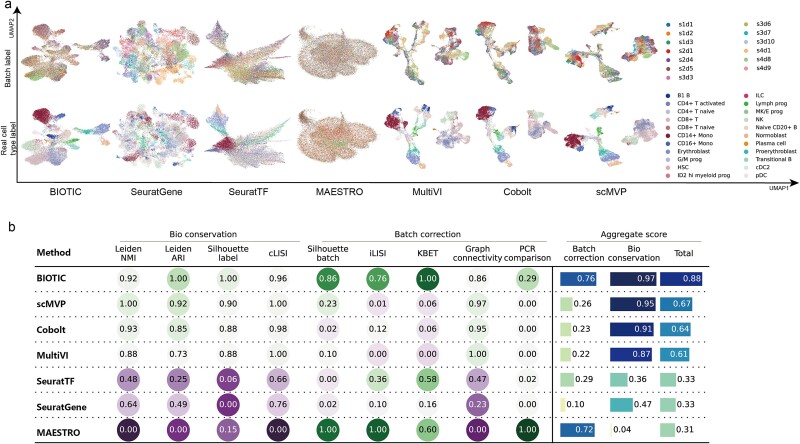

Cells depicted by TF activity are free from batch effect

We next showed that by incorporating regulatory mechanism into modeling, BIOTIC can infer TF activity free from the interference of confounding factors, the cells represented by TF activity would not be affected by batch effect. BMMC dataset is adopted to evaluate the performance of BIOTIC’s TF activity in correcting batch effect. BMMC dataset was sequenced from 12 healthy human donors, and the data generation was distributed across four sites, exhibiting a nested batch effect structure of donor and site [31]. Here, cells that originate from a singular donor and site are delineated as a “batch”, resulting in 13 distinct batches. As shown in Fig. 4a, the legend  represents the sampling site

represents the sampling site  and donor

and donor  . Batch effects are also present in the Skin dataset, but not as complex and pronounced as those in the BMMC dataset. The results of batch correction on the Skin dataset can be found in Additional file 1: Fig. S4.

. Batch effects are also present in the Skin dataset, but not as complex and pronounced as those in the BMMC dataset. The results of batch correction on the Skin dataset can be found in Additional file 1: Fig. S4.

Figure 4.

Performance comparison of batch effect correction. (a) UMAP clustering results of BIOTIC inferred TF activity and baseline methods in the BMMC dataset, cells are colored by batch and cell type, respectively. (b) Metrics of BIOTIC and baseline methods (normalized using min-max scaling), obtained through Benchmarker [44].

Fig. 4a presents the UMAP visualizations based on the embeddings obtained by BIOTIC and the baseline methods, where the upper and the lower ones are colored by batch and cell type respectively. Signac and scJoint did not participate in the benchmark analysis on BMMC dataset as they require fragment files. Significantly, TF activity inferred by BIOTIC displays a homogeneous distribution of cells from diverse batches within the clusters and clustered according to cell types. In contrast, the three multi-omics integration methods—MultiVI, Cobolt, and scMVP—exhibited significant batch-specific clustering. The other two TF-related methods, SeuratTF and MAESTRO, can also effectively integrate cells from various batches, indicating that TFs are responsible for the inherent regulation of cells. But these two TF related methods cannot cluster according to cell types.

As illustrated in Fig. 4b, BIOTIC outperforms all the other methods in most of normalized biological conservation metrics and batch correction metrics, detailed metrics are described in Additional file 2: Table S3. Among all benchmark methods, TF-based methods perform well in batch correction metrics, as BIOTIC achieves 0.76, MAESTRO achieves 0.72, and SeuratTF achieves 0.29, ranking as the top three. However, MAESTRO and SeuratTF fall short in biological conservation, as they are not able to identify cells in different cell types. Overall, BIOTIC effectively mitigates the impact of batch effects and maintains cellular heterogeneity.

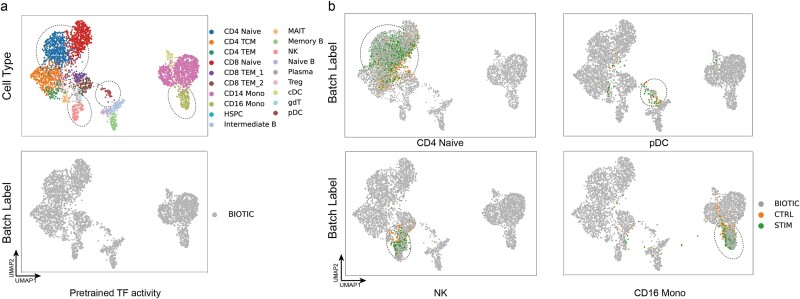

TF activity allows cell mapping across data

For the urgent demand for constructing large single-cell reference atlases, the proposal of integration methods that allows cell mapping is of great importance. However, due to the serious noises in single-cell sequencing data, most traditional integration methods may struggle when mapping cross-dataset cells within the same cell type [24, 45]. The state-of-the-art transfer learning-based methods require fine-tuning when mapping a new querying dataset [45].

However, owing to the intelligent structural design of BIOTIC, the inferred TF activity has been proven to be capable of capturing gene regulatory features of TFs. If the TF activity inferred by BIOTIC can characterize the cell type essentially by capturing the gene regulatory features of TFs, the cells with identity types from different samples should possess very similar TF activity. Therefore, their TF activity vectors would be close to each other at the same mapping space. In this experiment, an initial evaluation of BIOTIC’s potential for cell mapping across data was conducted. The model pretrained on the PBMC dataset was applied to type the cells in PBMC-IFNB dataset. The visualization of TF activity of PBMC dataset is shown in Fig. 5a. PBMC-IFNB dataset only includes scRNA-seq data and consists of two batches of scRNA-seq data from normal PBMCs and PBMCs subjected to IFNB stimulation.

Figure 5.

Performance of BIOTIC as pre-trained model on the PBMC-IFNB dataset. (a) The visualization of PBMC dataset, color by cell type label and batch label, respectively. (b) The mapping results of CD4 naive, CD16 mono, pDC, and NK cells from the PBMC-IFNB dataset onto the PBMC dataset.

We then attempted to map the cells from the PBMC-IFNB dataset to the PBMC dataset. Due to inconsistency of the annotation system between the query and the atlas, only cells with unified annotations were included, i.e. those cells whose annotations exist in both sets. As illustrated in Fig. 5b, the queried cells can be clearly approximate to the cells in the atlas with the same cell type, including CD4 Naive, CD16 Mono, pDC, and NK. Even though the queried cells of the same cell type are from different batches, the mapping results based on TF activity still show great consistency, further implying its essential cell characterization.

The results imply that the pretrained BIOTIC has excellent performance on mapping cells across data, for that the inferred TF activity refines the gene regulatory information to reveal the essential characters of cell identity. Most importantly, the generalization ability of the pretrained BIOTIC on scRNA-seq data has the potential to create a large-scale cell atlas.

Conclusions

The gene regulation study has witnessed significant advances with the advent of single-cell multi-omics sequencing. Single-cell multi-omics data offers insights into molecular components during the regulatory processes, opening avenues to explore regulatory mechanism. Previous studies generally integrated multi-omics data to map them to a common embedding vector, overlooking the underlying biological mechanisms. Therefore, we propose BIOTIC, a Bayesian model that explicitly incorporates the generative process of gene expression profiles regulated by gene accessibility, TF activity and TF-gene regulatory weight.

Our experiments demonstrate that TF activity inferred by BIOTIC remains robust against batches, signal noise and technical bias, making it a valuable tool for characterizing cell types, tracking cell development, and removing batch effects. Moreover, BIOTIC quantifies the regulatory strength of TFs on their target genes to construct a dynamic TF-gene regulatory network of single-cell resolution (Additional file 1: Fig. S5), providing valuable insights into the study of diverse regulatory patterns. Future developments for BIOTIC include incorporating additional biological factors, such as DNA methylation and TF binding sites, to enhance its modeling of gene regulation and improve the inference of regulatory elements. The BIOTIC modeling framework accounts for gene expression regulation by capturing key regulatory processes. As DNA methylation plays a critical role in modulating the binding of TFs [46], it can be systematically incorporated into current model as a latent variable in the generative process of gene expression. This integration would enable the inclusion of methylation data to refine the modeling of regulatory mechanisms. Ultimately, the goal is to enhance BIOTIC’s modeling capability by integrating additional information, such as directed reference regulatory relationships. The primary objective is not only achieving high performance in specific tasks but also unveiling valuable insights within multi-omics data at the cellular level. BIOTIC is designed to empower researchers to unravel the intricate regulatory mechanisms.

Key Points

BIOTIC introduces a Bayesian approach to integrate multi-omics data for accurate inference of TF activity and characterization of cell identity.

The framework optimizes the estimation of TF activity by considering complex gene regulatory mechanisms.

BIOTIC excels in multiple biological tasks, demonstrating superior performance in cell typing and batch effect correction compared to existing methods.

The model’s flexibility paves the way for incorporating further biological insights, enhancing comprehensive analysis of gene regulation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Shaorong Fang and Tianfu Wu from Information and Network Center of Xiamen University are acknowledged for the help with high performance computing (HPC).

Contributor Information

Lan Cao, Department of Automation, Xiamen University, Xiang'an South Road, Xiang'an, 361102, Xiamen, Fujian, China.

Wenhao Zhang, Department of Automation, Xiamen University, Xiang'an South Road, Xiang'an, 361102, Xiamen, Fujian, China.

Fan Yang, Department of Automation, Xiamen University, Xiang'an South Road, Xiang'an, 361102, Xiamen, Fujian, China; National Institute for Data Science in Health and Medicine, Xiamen University, Xiang'an South Road, Xiang'an, 361102, Xiamen, Fujian, China; Xiamen Key Laboratory of Big Data Intelligent Analysis and Decision, Xiamen University, Xiang'an South Road, Xiang'an, 361102, Xiamen, Fujian, China.

Shengquan Chen, School of Mathematical Sciences and LPMC, Nankai University, Weijing Road, Nankai, 300071,Tianjin, China.

Xiaobing Huang, Department of Medical Oncology, Fuzhou First Hospital Affiliated with Fujian Medical University, Chating Road, Taijiang, 350000, Fuzhou, Fujian, China.

Feng Zeng, Department of Automation, Xiamen University, Xiang'an South Road, Xiang'an, 361102, Xiamen, Fujian, China; National Institute for Data Science in Health and Medicine, Xiamen University, Xiang'an South Road, Xiang'an, 361102, Xiamen, Fujian, China; Xiamen Key Laboratory of Big Data Intelligent Analysis and Decision, Xiamen University, Xiang'an South Road, Xiang'an, 361102, Xiamen, Fujian, China.

Ying Wang, Department of Automation, Xiamen University, Xiang'an South Road, Xiang'an, 361102, Xiamen, Fujian, China; National Institute for Data Science in Health and Medicine, Xiamen University, Xiang'an South Road, Xiang'an, 361102, Xiamen, Fujian, China; Xiamen Key Laboratory of Big Data Intelligent Analysis and Decision, Xiamen University, Xiang'an South Road, Xiang'an, 361102, Xiamen, Fujian, China; State Key Laboratory of Mariculture Breeding, Xiamen University, Xiang'an South Road, Xiang'an, 361102, Xiamen, Fujian, China.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (62173282, 62472363) and Fuzhou Inter-institutional Science and Technology Cooperation Project (2024-Y-018).

Data availability

The PBMC dataset can be accessed at https://www.10xgenomics.com/datasets/pbmc-from-a-healthy-donor-no-cell-sorting-10-k-1-standard-2-0-0. The Lymph node dataset is accessed at https://www.10xgenomics.com/datasets/fresh-frozen-lymph-node-with-b-cell-lymphoma-14-k-sorted-nuclei-1-standard-2-0-0. The BMMC dataset can be accessed in Expression Omnibus (GEO) with the accession number GSE194122. The Skin dataset was collected from GEO with the accession number GSE140203. The Cerebral cortex and the 1469 dataset are available at GEO with the accession number GSE126074. The A549 dataset was collected from GEO with the accession number GSE117089. The PBMC-IFNB dataset is available in GEO with the accession number GSE96583. The source code and pre-processing scripts are available at https://github.com/Ying-Lab/BIOTIC, and the preprocessed datasets can be accessed on Zenodo at https://zenodo.org/records/14214592.

References

- 1. MacNeil L, Walhout A. Gene regulatory networks and the role of robustness and stochasticity in the control of gene expression. Genome Res 2011;21:645–57. 10.1101/gr.097378.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen K, Rajewsky N. The evolution of gene regulation by transcription factors and microRNAs. Nat Rev Genet 2007;8:93–103. 10.1038/nrg1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tran A, Yang P, Yang JYH. et al. scREMOTE: using multimodal single cell data to predict regulatory gene relationships and to build a computational cell reprogramming model. NAR Genom Bioinform 2022;4:lqac023. 10.1093/nargab/lqac023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arendt D, Musser JM, Baker CVH. et al. The origin and evolution of cell types. Nat Rev Genet 2016;17:744–57. 10.1038/nrg.2016.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. He H, Yang M, Li S. et al. Mechanisms and biotechnological applications of transcription factors. Synthetic Syst Biotechnol 2023;8:565–77. 10.1016/j.synbio.2023.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zeng H. What is a cell type and how to define it? Cell 2022;185:2739–55. 10.1016/j.cell.2022.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ma C, Brent M. Inferring TF activities and activity regulators from gene expression data with constraints from TF perturbation data. Bioinformatics 2021;37:1234–45. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Holland CH, Tanevski J, Perales-Patón J. et al. Robustness and applicability of transcription factor and pathway analysis tools on single-cell RNA-seq data. Genome Biol 2020;21:36. 10.1186/s13059-020-1949-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Huang DW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc 2009;4:44–57. 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pomaznoy M, Ha B, Peters B. GOnet: a tool for interactive gene ontology analysis. BMC Bioinform 2018;19:470. 10.1186/s12859-018-2533-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schubert M, Klinger B, Klünemann M. et al. Perturbation-response genes reveal signaling footprints in cancer gene expression. Nat Commun 2018;9:20. 10.1038/s41467-017-02391-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gao S, Dai Y, Rehman J. A Bayesian inference transcription factor activity model for the analysis of single-cell transcriptomes. Genome Res 2021;31:1296–311. 10.1101/gr.265595.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Alvarez MJ, Shen Y, Giorgi FM. et al. Functional characterization of somatic mutations in cancer using network-based inference of protein activity. Nat Genet 2016;48:838–47. 10.1038/ng.3593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Aibar S, González-Blas CB, Moerman T. et al. SCENIC: single-cell regulatory network inference and clustering. Nat Methods 2017;14:1083–6. 10.1038/nmeth.4463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang C, Sun D, Huang X. et al. Integrative analyses of single-cell transcriptome and regulome using MAESTRO. Genome Biol 2020;21:198. 10.1186/s13059-020-02116-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stuart T, Srivastava A, Madad S. et al. Single-cell chromatin state analysis with Signac. Nat Methods 2021;18:1333–41. 10.1038/s41592-021-01282-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Weidemüller P, Kholmatov M, Petsalaki E. et al. Transcription factors: bridge between cell signaling and gene regulation. Proteomics 2021;21:2000034. 10.1002/pmic.202000034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Conard A, Goodman N, Hu Y. et al. TIMEOR: a web-based tool to uncover temporal regulatory mechanisms from multi-omics data. Nucleic Acids Res 2021;49:W641–53. 10.1093/nar/gkab384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gong B, Zhou Y, Purdom E. Cobolt: integrative analysis of multimodal single-cell sequencing data. Genome Biol 2021;22:351. 10.1186/s13059-021-02556-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ashuach T, Gabitto MI, Koodli RV. et al. MultiVI: deep generative model for the integration of multimodal data. Nat Methods 2023;20:1222–31. 10.1038/s41592-023-01909-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li G, Fu S, Wang S. et al. A deep generative model for multi-view profiling of single-cell RNA-seq and ATAC-seq data. Genome Biol 2022;23:20. 10.1186/s13059-021-02595-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lin Y, Wu TY, Wan S. et al. scJoint integrates atlas-scale single-cell RNA-seq and ATAC-seq data with transfer learning. Nat Biotechnol 2022;40:703–10. 10.1038/s41587-021-01161-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cao Z, Gao G. Multi-omics single-cell data integration and regulatory inference with graph-linked embedding. Nat Biotechnol 2022;40:1458–66. 10.1038/s41587-022-01284-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lynch AW, Brown M. Multi-batch single-cell comparative atlas construction by deep learning disentanglement. Nat Commun 2023;14:4126. 10.1038/s41467-023-39494-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Krebs A. Studying transcription factor function in the genome at molecular resolution. Trends Genet 2021;37:798–806. 10.1016/j.tig.2021.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mansisidor A, Risca V. Chromatin accessibility: methods, mechanisms, and biological insights. Nucleus 2022;13:238–78. 10.1080/19491034.2022.2143106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kribelbauer JF, Rastogi C, Bussemaker HJ. et al. Low-affinity binding sites and the transcription factor specificity paradox in eukaryotes. Annual Rev Develop Biol 2019;35:357–79. 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100617-062719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Elkan C. Clustering documents with an exponential-family approximation of the Dirichlet compound multinomial distribution. In Proceedings of the 23rd international conference on Machine learning 2006, pp. 289–96.

- 29. Weibull W. A statistical distribution function of wide applicability. J Appl Mech 2021;18:293–7. 10.1115/1.4010337. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kingma D, Ba J. Adam: a method for stochastic optimization. In Proceedingsof 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations, 2015.

- 31. Luecken M. et al. A Sandbox for Prediction and Integration of DNA, RNA, and Proteins in Single Cells. In Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing Systems Track on Datasets and Benchmarks 13 (NeurIPS, 2021).

- 32. Li J, Bi W, Lu F. et al. Prognostic role of E2F1 gene expression in human cancer: a meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2023;23:509. 10.1186/s12885-023-10865-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ma S, Zhang B, LaFave LM. et al. Chromatin potential identified by shared single-cell profiling of RNA and chromatin. Cell 2020;183:1103–1116.e20. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chen S, Lake B, Zhang K. High-throughput sequencing of the transcriptome and chromatin accessibility in the same cell. Nat Biotechnol 2019;37:1452–7. 10.1038/s41587-019-0290-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cao J. et al. Joint profiling of chromatin accessibility and gene expression in thousands of single cells. Science 2018;361:1380–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kang H, Subramaniam M, Targ S. et al. Multiplexed droplet single-cell RNA-sequencing using natural genetic variation. Nat Biotechnol 2018;36:89–94. 10.1038/nbt.4042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Satija R, Farrell JA, Gennert D. et al. Spatial reconstruction of single-cell gene expression data. Nat Biotechnol 2015;33:495–502. 10.1038/nbt.3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Blondel V, Guillaume JL, Lambiotte R. et al. Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Experiment 2008;2008:P10008. 10.1088/1742-5468/2008/10/P10008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pedregosa F, Varoquaux G, Gramfort A. et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in python. J Mach Learn Res 2011;12:2825–30. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Trapnell C, Cacchiarelli D, Grimsby J. et al. The dynamics and regulators of cell fate decisions are revealed by pseudotemporal ordering of single cells. Nat Biotechnol 2014;32:381–6. 10.1038/nbt.2859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhu C, Yu M, Huang H. et al. An ultra high-throughput method for single-cell joint analysis of open chromatin and transcriptome. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2019;26:1063–70. 10.1038/s41594-019-0323-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhang Z, Yang C, Zhang X. scDART: integrating unmatched scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq data and learning cross-modality relationship simultaneously. Genome Biol 2022;23:139. 10.1186/s13059-022-02706-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Setty M, Kiseliovas V, Levine J. et al. Characterization of cell fate probabilities in single-cell data with Palantir. Nat Biotechnol 2019;37:451–60. 10.1038/s41587-019-0068-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Luecken M, Büttner M, Chaichoompu K. et al. Benchmarking atlas-level data integration in single-cell genomics. Nat Methods 2022;19:41–50. 10.1038/s41592-021-01336-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lotfollahi M, Naghipourfar M, Luecken MD. et al. Mapping single-cell data to reference atlases by transfer learning. Nat Biotechnol 2022;40:121–30. 10.1038/s41587-021-01001-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Moore LD, Le T, Fan G. DNA methylation and its basic function. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013;38:23–38. 10.1038/npp.2012.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The PBMC dataset can be accessed at https://www.10xgenomics.com/datasets/pbmc-from-a-healthy-donor-no-cell-sorting-10-k-1-standard-2-0-0. The Lymph node dataset is accessed at https://www.10xgenomics.com/datasets/fresh-frozen-lymph-node-with-b-cell-lymphoma-14-k-sorted-nuclei-1-standard-2-0-0. The BMMC dataset can be accessed in Expression Omnibus (GEO) with the accession number GSE194122. The Skin dataset was collected from GEO with the accession number GSE140203. The Cerebral cortex and the 1469 dataset are available at GEO with the accession number GSE126074. The A549 dataset was collected from GEO with the accession number GSE117089. The PBMC-IFNB dataset is available in GEO with the accession number GSE96583. The source code and pre-processing scripts are available at https://github.com/Ying-Lab/BIOTIC, and the preprocessed datasets can be accessed on Zenodo at https://zenodo.org/records/14214592.