ABSTRACT

Background

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection in the first year of life has been linked with an increased risk for asthma. Some propose that RSV‐induced inflammation leads to lasting airway changes, while others contend that RSV bronchiolitis is a marker for underlying predisposition. Social distancing adopted during the COVID‐19 pandemic has led to a dramatic reduction in RSV activity, providing an unexpected opportunity to investigate this debate.

Objective

To compare the incidence of asthma‐related healthcare‐utilization (HCU) in 1–3 years of age between children born in March–June 2020 (l‐RSV) and children born during the same months in the years 2014–2017 (H‐RSV).

Study Design and Methods

This retrospective study utilized nationwide healthcare database records from Clalit‐Healthcare‐Services, the largest healthcare organization in Israel. The study analyzed asthma‐related HCU, using multivariate logistic regression and Bayesian analyses.

Results

172,463 children were included in the study: 32,927 in the l‐RSV group versus 139,536 in the H‐RSV group. The l‐RSV cohort showed insignificant changes and increased rates of asthma‐related HCU between 1 and 3 years of age in some asthma surrogates, compared to the H‐RSV group.

Conclusion

Reduction in RSV exposure during the first year of life did not correlate with a decrease in asthma‐related HCU. This may imply that RSV infection in infancy functions as an indicator of underlying predisposition rather than a direct cause of asthma.

1. Introduction

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) bronchiolitis is a viral infection that commonly affects young children, causing inflammation and narrowing of the small airways in the lungs [1]. It is a leading cause of hospitalization in infants and young children [2, 3]. Previous studies have shown that children who experience severe RSV bronchiolitis in the first year of life may be at increased risk for developing asthma later in life [4, 5, 6].

The exact cause of the link between severe RSV bronchiolitis and subsequent asthma is still a subject of ongoing debate. Some argue that the severe inflammation caused by RSV leads to permanent changes in the airways, causing airway hyperreactivity and increasing the risk of asthma [6]. Others suggest that severe RSV bronchiolitis in the first year of life is simply a marker for underlying predispositions rather than the effects of the virus [7, 8, 9].

An ideal experiment to determine the causality of the association between severe RSV bronchiolitis and subsequent asthma would involve isolating children from exposure to the virus in the first year of life and comparing their incidence of asthma later in life to that of children who were exposed to RSV during their first year. If the incidence of asthma were lower in the “isolated” group of children compared to the “exposed” group, this would support the hypothesis that severe RSV bronchiolitis causes permanent changes in the airways, increasing the risk of these conditions. Any other outcomes would lean toward the theory that severe RSV bronchiolitis in the first year of life primarily serves as an indicator of underlying lung maldevelopment, immunologic dysregulation or other predisposition.

The COVID‐19 pandemic provided an unexpected opportunity to observe the effects of limiting exposure to RSV, as the seasonal winter peak of RSV cases during 2021 was largely eliminated [10, 11, 12]. Unexpectedly, the RSV season occurred in the summer of 2021 [11, 13], therefore children born between March 2020 and June 2020, have been exposed to low RSV activity during their first year of life.

Taking advantage of the natural experiment provided by the COVID‐19 pandemic this study aimed to compare the incidence of healthcare‐utilization (HCU) for asthma in early childhood between children born during March–June 2020 (low RSV exposure in the first year of life, l‐RSV group) and children born during the same months in the years 2014–2017 (high RSV exposure in the first year of life, H‐RSV group).

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This is a population‐based retrospective study using nationwide computerized database records from Clalit‐Healthcare‐Services (CHS) that compared children born between March and June 2020 (l‐RSV) and children born during the same months in the years of 2014–2017 (H‐RSV). These months of birth were chosen to avoid exposure to the summer RSV peak of 2021 for the l‐RSV group [11, 13]. CHS is the largest state‐mandated healthcare provider in Israel with over 5 million members, constituting 52% of the population of Israel. The CHS database includes extensive demographic data, anthropometric measurements, diagnoses from community clinics and hospitals, medication dispensing information, and comprehensive laboratory data. All data were de‐identified before analysis and this study involves secondary use of already collected clinical information. The study was granted an exemption from informed consent due to the de‐identified nature of the data and was approved by the CHS Ethical Committee (approval number #0067‐23‐SOR).

2.2. Study Population

The analysis encompassed all CHS members fulfilled the above inclusion criteria, who had a comprehensive medical history on record. We excluded children with chromosomal abnormalities (e.g., trisomy 21, see Supporting Information S1: Table 1) and patients who tested positive for viral RSV‐PCR during their first year of life, despite being born between March and June, 2020.

2.3. Data Sources and Organization

We analyzed deidentified patient‐level data extracted from CHS electronic medical records (MDCLONE system). This data set comprised information such as date of birth, sex, diagnoses of allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, food allergies, mode of delivery, gestational age, birth weight, the presence of multiple births, eosinophilic counts (collected as part of the routine care between the ages of 6 and 18 months) and RSV positive PCR. Additionally, we obtained data on maternal asthma history by linking the child's file to the mother's chart.

2.4. Study Outcomes

ICD‐9 codes assigned between the ages of 1 and 3 to ascertain the child's diagnoses of asthma or wheezing by the primary doctor in community clinic visits or during hospitalizations were utilized (Supporting Information S1: Table 2). Additionally, prescriptions of short‐acting beta‐agonist (SABA) inhalers, inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and oral corticosteroids (OCS) between 1 and 3 years of age were investigated.

Due to the challenges in defining asthma in this age group, multiple surrogate markers for asthma were utilized as described above. Additionally, to establish a comprehensive definition with increasing specificity of asthma definition, a new variable was created, termed the “Integrated Asthma Diagnosis Index.” This variable was defined as follows: the presence of a SABA prescription in the second and third year of life AND at least one instance of ICS prescription (in the second or third year) AND at least one ICD‐9 code associated with asthma from either community or hospital records.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

An initial descriptive analysis included calculations of single variable distribution, central tendency and dispersion. Further univariate analysis was conducted employing the chi‐square test for dichotomous variables, the Student's t‐test for normally distributed continuous variables, and the Mann–Whitney U‐test for categorical or non‐normally distributed continuous variables. Subsequently, a multivariate logistic regression model, implementing a backward elimination technique while evaluating goodness‐of‐fit parameters was executed. For sensitivity analysis and validation of the findings, Bayesian analysis was also has been used. Using the brms package in R [14, 15] we have entered the same variables as in the original model for “Integrated Asthma Diagnosis Index,” with brms default (partially‐informed) priors. This analysis enables us to look at the sampled posterior distribution of the results. All statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.2.0.

3. Results

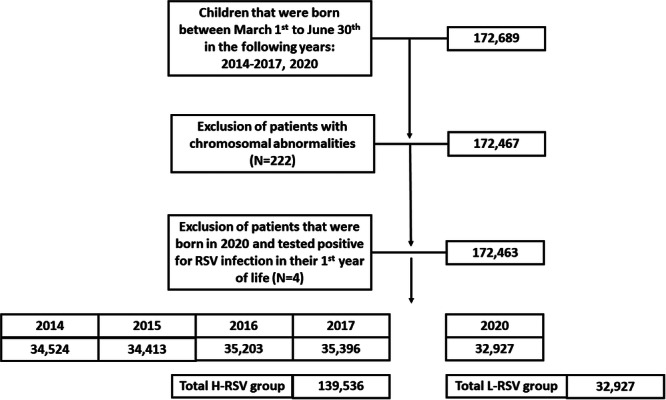

A total of 172,689 children initially met the inclusion criteria and were enrolled (Figure 1). Among them, 222 children were excluded due to chromosomal abnormalities. To confirm that the children within the l‐RSV group had only minimally been exposed to RSV in their first year of life, patients who tested positive for RSV via PCR in their first year of life and were born in 2020 were excluded. Consequently, in the final analysis included 172,463 patients, with 32,927 categorized as l‐RSV activity group and 139,536 categorized as H‐RSV activity group.

Figure 1.

Flowchart illustration detailing the enrollment process for patients in this study.

Demographic and clinical characteristics are detailed in Table 1. Gender distribution, mode of delivery, and maternal age showed no significant difference between the two groups. However, lower rates of prematurity (12.38% vs. 13.36%, p < 0.001) and multiple births (twins, triplets, etc., 4.08% vs. 4.59%, p < 0.001) were noted in the l‐RSV group versus H‐RSV group. Interestingly, higher rates of atopy were observed in the l‐RSV group compared to the H‐RSV group, as evidenced by a higher prevalence of allergic rhinitis (OR = 1.14, CI = 1.04–1.26, p = 0.007), atopic dermatitis (OR = 1.17, CI = 1.13–1.21, p < 0.001), and blood eosinophilia between 6 and 18 months of age (352 ± 2.77 cells/mcL in l‐RSV group vs. 306 ± 2.52 cells/mcL in H‐RSV group, p < 0.001). However, there was no statistically significant difference in the rates of maternal asthma between both groups (7.9% approximately in both groups, p = 0.87).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical variables—descriptive analysis.

| Variable | H‐RSV group N = 139,314 | l‐RSV group N = 32,927 | p value | Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic parameters | ||||

| Gender (male) (N, %) | 72121 (51.68) | 16969 (51.54) | 0.1 | 0.99 (0.97–1.02) |

| Mean maternal age (mean ± SD) | 30.22 ± 5.5 | 30.49 ± 5.52 | < 0.001 | — |

| Socioeconomic level score (N, %) | 123711 (88.66) | 28942 (87.89) | < 0.001 | 0.93 (0.89–0.96) |

| Pregnancy related parameters | ||||

| Birth weight (mean ± SD) | 3183.61 ± 533.49 | 3198.69 ± 517.69 | < 0.001 | — |

| Cesarean delivery (N, %) | 8,663 (6.21) | 2141 (6.5) | 0.3 | 1.06 (0.98–1.08) |

| Multiple embryos pregnancy (N, %) | 2024 (4.59) | 441 (4.08) | < 0.001 | 0.88 (0.79–0.98) |

| Premature delivery (N, %) | 6322 (13.36) | 1413 (12.38) | < 0.001 | 0.92 (0.86–0.97) |

| Number of previous birth (Median, Q1–2) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | < 0.001 | — |

| Atopic related parameters | ||||

| Eosinophilic count between 6–18 months of age (mean + SD) | 3.06 + 2.52 | 3.52 + 2.77 | < 0.001 | — |

| Allergic rhinitis (N, %) | 1970 (1.41) | 530 (1.61) | 0.007 | 1.14 (1.04–1.26) |

| Atopic dermatitis (N, %) | 23485 (16.83) | 6300 (19.13) | < 0.001 | 1.17 (1.13–1.2) |

| Food allergy (N, %) | 599 (0.43) | 127 (0.38) | 0.27 | 0.89 (0.74–1.08) |

| Maternal asthma (N, %) | 10968 (7.86) | 2597 (7.88) | 0.87 | 1 (0.96–1.05) |

Next, univariate analyses for the study outcomes were performed, as presented in Table 2 and Supporting Information S1: Table 3. Notably, most clinical outcomes measured between 1 and 3 years of age exhibited a tendency towards increased HCU for asthma among the l‐RSV group versus the H‐RSV group. Rates of ICD‐9 codes for wheezing diagnoses increased by 6% (CI = 1.02–1.08, p < 0.001), while ICD‐9 codes for diagnoses of asthma or wheezing increased by 4% (CI = 1.01–1.07, p < 0.001). Hospitalization rates due to asthma or wheezing similarly increased by 41% (CI = 1.27–1.56, p < 0.001) among the l‐RSV group compared to the H‐RSV group. Medication prescribed in 1–3 years of age also increased: SABA prescriptions rose by 8% (CI = 1.05–1.11, p < 0.001), ICS prescriptions increased by 49% (CI = 1.39–1.59, p < 0.001), and OCS prescriptions increased by 13% (CI = 1.08–1.17, p < 0.001). The only exception was the ICD‐9 code for asthma with a reduction of 7% in the l‐RSV group compared to the H‐RSV group (CI = 0.87–0.97, p < 0.001). Collectively, these findings suggest, in the univariate analysis, an increase in HCU for asthma in 1–3 years of age of 4%–49% among the l‐RSV group compared to the H‐RSV group.

Table 2.

Univariate comparison of clinical outcomes between l‐RSV and H‐RSV activity groups.

| Variable | H‐RSV group N = 139,314 | l‐RSV group N = 32,927 | Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wheezing episode (N, %) | 34123 (24.49) | 8408 (25.53) | 1.06* (1.02–1.08) |

| Asthma episode (N, %) | 7944 (5.7) | 1748 (5.3) | 0.93* (0.87–0.97) |

| Asthma or wheezing episode (N, %) | 36904 (26.48) | 8994 (27.31) | 1.04* (1.01–1.07) |

| Hospitalization (N, %) | 1473 (1.05) | 489 (1.48) | 1.41* (1.27–1.56) |

| SABA prescriptions (N, %) | 20553 (35.77) | 12374 (37.58) | 1.08* (1.05–1.11) |

| ICS prescriptions (N, %) | 27550 (11.6) | 5377 (16.3) | 1.49* (1.39–1.59) |

| OCS prescriptions (N, %) | 29450 (9.5) | 3477 (10.56) | 1.13* (1.08–1.17) |

| Any antiasthma medication (N, %) | 17893 (41.7) | 15034 (45.65) | 1.17* (1.15–1.2) |

| Asthma Integrated Diagnosis Index** (N, %) | 41593 (29.86) | 10750 (32.65) | 1.14* (1.11–1.17) |

Abbreviations: ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; OCS, oral corticosteroids; SABA, short acting beta‐agonists; any medication, ICS or SABA or OCS.

p < 0.001.

Prescription of SABA in the second and the third year AND at least once ICS (in the second or the third year) and at least one ICD code from PCP or admission.

To address the complexity of defining asthma in these age groups, multiple surrogate outcomes were employed. Furthermore, the “Integrated Asthma Diagnosis Index” was defined (as detailed in the methods section) through a combination of HCU markers for both the second and third years of life, enhancing the sensitivity of the asthma definition. In general, this marker revealed a 14% increase in the asthma rate for the l‐RSV activity group compared to the H‐RSV activity group (CI = 1.11–1.17, p < 0.001).

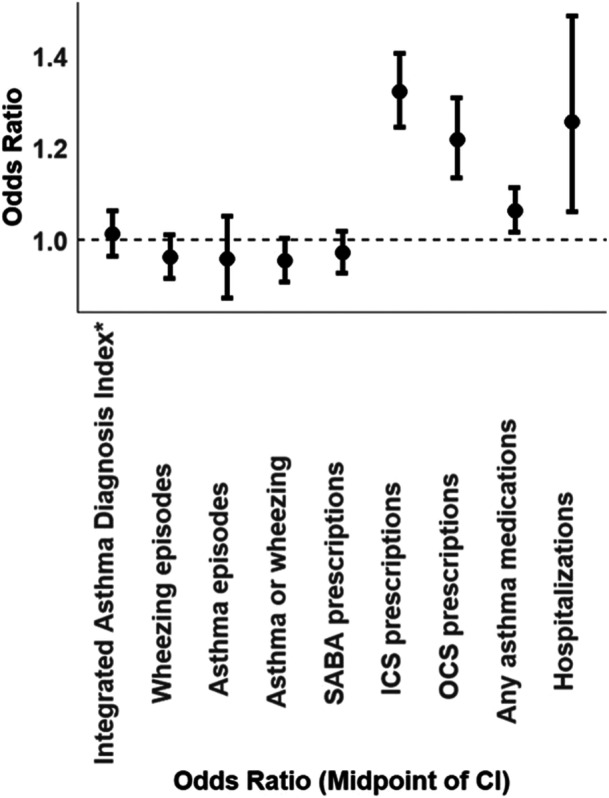

Next, multivariate analysis as depicted in Figure 2 and detailed in Supporting Information S1: Table 4 was conducted. The incidence of HCU for asthma was adjusted for evidence of atopy (including ICD‐9 codes for allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, and blood eosinophilic levels), ICD‐9 codes for asthma in maternal charts, and for the presence of prematurity. Much like the findings in the univariate analysis, the clinical outcomes did not exhibit reduced rates in the l‐RSV group compared to the H‐RSV group. Moreover, most of these outcomes did not demonstrate statistically significant differences between the two groups. For instance, the incidence of wheezing episodes (OR = 0.96, CI = 0.92–1.01, p = 0.13), the incidence of asthma (OR = 0.97, CI = 0.88–1.06, p = 0.51) and the incidence of SABA prescriptions (OR = 0.97, CI = 0.93–1.02, p = 0.25) did not show any significant differences between children in the l‐RSV activity group compared to those in the H‐RSV activity group between 1 and 3 years of age. The combined outcome “Integrated Asthma Diagnosis Index” also exhibited insignificance between the two groups (OR = 1.01, CI = 0.96–1.06, p = 0.61). Interestingly, clinical outcomes related to hospitalizations, ICS, and OCS prescriptions all demonstrated an increase in incidence among children in the l‐RSV group compared to children in the H‐RSV group.

Figure 2.

Adjusted multivariate odds ratio for comparison between l‐RSV activity and H‐RSV activity groups between 1 and 3 years of age.

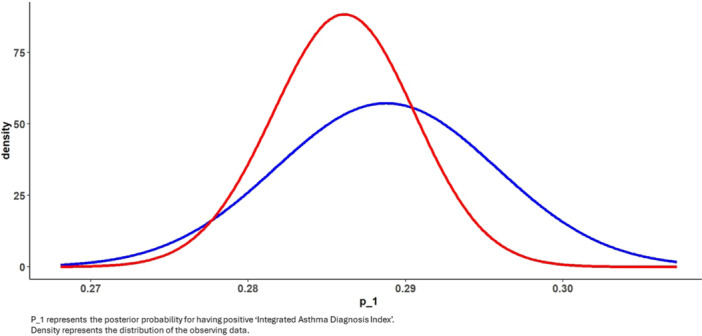

Subsequently a sensitivity analysis for multivariate logistic regression with the outcome measure “Integrated Asthma Diagnosis Index” using Bayesian analysis was demonstrated (see method section for details). This approach allowed for a comparison of the posterior distribution of results, offering us a more insightful understanding of the comparison. As depicted in Figure 3, the incidence distribution of the “Integrated Asthma Diagnosis Index” in both cohorts largely overlapped, with a slight inclination towards a higher incidence in the l‐RSV group compared to the H‐RSV group. These findings align with the results presented in Figure 2 of the multivariate logistic regression. Taken together, these models suggest that, despite the low exposure to RSV during the first year of life among children that were born at 2020 (l‐RSV group), there was no observed reduction in asthma‐related HCU within this group.

Figure 3.

Bayesian comparison between l‐RSV activity group (blue) to H‐RSV activity group (red) distributions for the logistic multivariate comparison of “Integrated Asthma Diagnosis Index.”

4. Discussion

This large‐scale data study aimed to compare the incidence of HCU for asthma in early childhood between children who were minimally exposed to RSV in their first year of life (born between March and June 2020, l‐RSV group) and children who were “normally” exposed to RSV in their first year of life (born during the same months in the years 2014–2017, H‐RSV group). Overall, the results of this study suggest an absence of reduction in asthma‐related HCU between 1 and 3 years of age in the l‐RSV exposure group compared to the H‐RSV exposure group. These findings were consistent across univariate and multivariate analyses and sensitivity analyses using Bayesian methods. Children born in 2020 entered their second year of life in 2021. Previous studies have indicated a resurgence in viral activity and a subsequent decline in asthma control during this period [11, 16, 17]. However, in the third year of life (2022 for those born in 2020), earlier research suggests that viral activity returned to a more typical pattern following the resurgence in 2021 [18].

The absence of a correlation between reduced RSV exposure during the first year of life and decreased asthma‐related healthcare utilization between ages 1 to 3 may suggest that RSV serves primarily as a marker of underlying lung development, immune dysregulation, or other predisposing factors. Both the respiratory tract and immune system undergo rapid maturation during the first year of life, and it seems that postnatal development is affected by and affects responses to viral infections [4, 19]. Associations of RSV infection with later‐onset asthma have been reported in several studies [20, 21, 22, 23]. A potential link between RSV infection, altered immune responses, and subsequent asthmatic symptoms was suggested [23]. Studies of the peripheral blood lymphocytes from these children and animal models suggested that RSV enhances allergic TH2 cytokine response and perivascular inflammation [9, 23]. Also in studies of the effects of age on responses to RSV infection in a neonatal mouse model, neonates did not have overt disease during primary infection, but when rechallenged with RSV in adult life, they showed enhanced disease, characterized by increased inflammatory cell recruitment, including TH2 cells [4, 24]. This model suggests that RSV infection at a very young age has the potential to cause long‐term alterations to the immune system.

In contrast to the evidence supporting a direct causal role of viral bronchiolitis in the pathogenesis of asthma twin studies among monozygotic pairs discordant for severe RSV bronchiolitis did not support the theory that RSV bronchiolitis causes asthma, indicating a genetic predisposition [25, 26]. Additionally, other studies propose that viral lower respiratory tract infections may serve as a marker for atopic predisposition rather than a direct cause of future wheezing and asthma [27]. Allergic sensitization to aeroallergens, beginning in the first year of life, was identified as a significant risk factor for viral‐induced wheeze, and this was significant for rhinovirus but not for RSV. However, having viral wheeze did not increase the risk of developing allergic sensitization [28]. Another birth cohort included a high‐risk cohort of infants born to mothers with asthma, which also suggested that severe bronchiolitis is a result of pre‐existing susceptibility of the airway to react to viral infections [29]. Taken together, these studies suggest that allergic sensitization and/or airway dysfunction may serve as predisposing factors that increase host susceptibility to viral bronchiolitis. The occurrence of viral bronchiolitis appears to reflect a predisposition to wheeze with viral infections rather than the viral infection serving as a causative factor for subsequent asthma. A combination of these two explanations for asthma inception is probably the reality. However, our study underscores the significance of predispositions in determining the likelihood of asthma development.

Interestingly, this study uncovered higher rates of atopy in the l‐RSV group compared to the H‐RSV group, evident in a greater prevalence of allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, and elevated blood eosinophil counts between 6 and 18 months of age. A prior study demonstrated an increased incidence of atopic dermatitis in children born during the COVID era [30], while another suggested alterations in the microbiota for children born during the same period [31]. Drawing from our cohort, it is tempting to speculate that the absence of viral exposure in the first year may lead to an increase in atopy, offering a potential explanation based on the hygiene hypothesis [32]. In this context, social measures in response to the COVID‐19 pandemic improved hygiene and reduced early exposure to bacterial and parasitic infections that were found to be crucial for the development of TH1 responses. This disruption in the balance between TH1 and TH2 responses, thought to be pivotal in regulating immune responses, could contribute to the observed increase in atopy. However, it is crucial to interpret these findings cautiously, as our cohort exclusively included children born between March and June each year, potentially introducing bias related to birth season and allergic desensitization.

This study demonstrates several strengths, including substantial sample size and nationwide distribution, with findings validated through different statistical approaches. However, several limitations have been identified. Its retrospective nature poses inherent constraints. Additionally, the absence of data on viral activity both in the hospital and the community is noteworthy, especially considering the fluctuations in viral activity in the post‐COVID‐19 era. Inherent to asthma studies in early childhood, the definition of asthma lacks solidity and is a subject of controversy. To address this, we attempted to mitigate the limitation by modeling various outcomes associated with asthma and creating a variable (“Integrated Asthma Diagnosis Index”) to consolidate the cohort of asthmatics. Furthermore, our cohort exclusively comprised patients born between March and June. While this selection was deliberate to avoid RSV exposure in the first year of life and to account for the unusual summer peak of RSV in 2021 [16], it does limit the generalizability of our conclusions to the broader population.

In summary, this extensive retrospective study leveraged the COVID‐19 pandemic as a natural experiment to investigate the relationship and causality between RSV exposure in the first year of life and subsequent asthma. Our findings indicate that low RSV exposure in the initial year of life did not lead to a reduction in the incidence of healthcare utilizations for asthma up to the age of 3 years. This may suggest that RSV infection during the first year of life functions as an indicator of underlying predispositions rather than a direct cause of asthma. The novelty of this study lies in its capacity to contribute causational insights to a topic that is an ongoing subject of debate, utilizing the unique context of the COVID‐19 pandemic. These findings are significant as they shed light on the mechanisms of asthma inception.

Author Contributions

Talia Amram: writing–original draft, data curation. Or A. Duek: writing–review and editing, formal analysis, methodology. Inbal Golan‐Tripto: writing–review and editing, conceptualization. Aviv Goldbart: conceptualization, writing–review and editing. David Greenberg: conceptualization, writing–review and editing. Guy Hazan: conceptualization, investigation, writing–original draft, formal analysis, supervision.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Supporting information.

Acknowledgments

The authors have nothing to report.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

- 1. Li Y., Wang X., Blau D. M., et al., “Global, Regional, and National Disease Burden Estimates of Acute Lower Respiratory Infections Due to Respiratory Syncytial Virus in Children Younger Than 5 Years in 2019: A Systematic Analysis,” The Lancet 399, no. 10340 (May 2022): 2047–2064, 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00478-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stockman L. J., Curns A. T., Anderson L. J., and Fischer‐Langley G., “Respiratory Syncytial Virus‐Associated Hospitalizations Among Infants and Young Children in the United States, 1997–2006,” Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 31, no. 1 (Jan 2012): 5–9, 10.1097/INF.0b013e31822e68e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tam C. C., Yeo K. T., Tee N., et al., “Burden and Cost of Hospitalization for Respiratory Syncytial Virus in Young Children, Singapore,” Emerging Infectious Diseases 26, no. 7 (Jul 2020): 1489–1496, 10.3201/eid2607.190539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hazan G., Eubanks A., Gierasch C., et al., “Age‐Dependent Reduction in Asthmatic Pathology Through Reprogramming of Postviral Inflammatory Responses,” The Journal of Immunology 208, no. 6 (Mar 2022): 1467–1482, 10.4049/jimmunol.2101094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Koponen P., Helminen M., Paassilta M., Luukkaala T., and Korppi M., “Preschool Asthma After Bronchiolitis in Infancy,” European Respiratory Journal 39, no. 1 (Jan 2012): 76–80, 10.1183/09031936.00040211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Piippo‐Savolainen E. and Korppi M., “Wheezy Babies—Wheezy Adults? Review on Long‐Term Outcome Until Adulthood After Early Childhood Wheezing,” Acta Paediatrica 97, no. 1 (Jan 2008): 5–11, 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hazan G., Sheiner E., Golan‐Tripto I., Goldbart A., Sergienko R., and Wainstock T., “The Impact of Maternal Hyperemesis Gravidarum on Early Childhood Respiratory Morbidity,” Pediatric Pulmonology 59, no. 3 (Dec 2023): 707–714, 10.1002/ppul.26817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jartti T., Bønnelykke K., Elenius V., and Feleszko W., “Role of Viruses in Asthma,” Seminars in Immunopathology 42, no. 1 (Feb 2020): 61–74, 10.1007/s00281-020-00781-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Singh A. M., Moore P. E., Gern J. E., R. F. Lemanske, Jr. , and Hartert T. V., “Bronchiolitis to Asthma: A Review and Call for Studies of Gene‐Virus Interactions in Asthma Causation,” American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 175, no. 2 (Jan 2007): 108–119, 10.1164/rccm.200603-435PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hazan G., Fox C., Eiden E., Anderson N., Friger M., and Haspel J., “Effect of the COVID‐19 Lockdown on Asthma Biological Rhythms,” Journal of Biological Rhythms 37, no. 2 (Apr 2022): 152–163, 10.1177/07487304221081730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hazan G., Fox C., Mok H., and Haspel J., “Age‐Dependent Rebound in Asthma Exacerbations After COVID‐19 Lockdown,” Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: Global 1, no. 4 (Nov 2022): 314–318, 10.1016/j.jacig.2022.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Saravanos G. L., Hu N., Homaira N., et al., “RSV Epidemiology in Australia Before and During COVID‐19,” Pediatrics 149, no. 2 (Feb 2022): e2021053537, 10.1542/peds.2021-053537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Binns E., Koenraads M., Hristeva L., et al., “Influenza and Respiratory Syncytial Virus During the COVID‐19 Pandemic: Time for a New Paradigm?,” Pediatric Pulmonology 57, no. 1 (Jan 2022): 38–42, 10.1002/ppul.25719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bürkner P. C. and Charpentier E., “Modelling Monotonic Effects of Ordinal Predictors in Bayesian Regression Models,” British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology 73, no. 3 (Nov 2020): 420–451, 10.1111/bmsp.12195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nalborczyk L., Batailler C., Lœvenbruck H., Vilain A., and Bürkner P. C., “An Introduction to Bayesian Multilevel Models Using Brms: A Case Study of Gender Effects on Vowel Variability in Standard Indonesian,” Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 62, no. 5 (May 2019): 1225–1242, 10.1044/2018_JSLHR-S-18-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Agha R. and Avner J. R., “Delayed Seasonal Rsv Surge Observed During the COVID‐19 Pandemic,” Pediatrics 148, no. 3 (Sep 2021): e2021052089, 10.1542/peds.2021-052089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Casalegno J. S., Bents S., Paget J., et al., “Application of a Forecasting Model to Mitigate the Consequences of Unexpected Rsv Surge: Experience from the post‐COVID‐19 2021/22 Winter Season in a Major Metropolitan Centre, Lyon, France,” Journal of Global Health 13 (Feb 2023): 04007, 10.7189/jogh.13.04007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Meslé M. M. I., Sinnathamby M., Mook P., and Pebody R., “Seasonal and Inter‐Seasonal Rsv Activity in the European Region During the COVID‐19 Pandemic from Autumn 2020 to Summer 2022,” Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses 17, no. 11 (Nov 2023): e13219, 10.1111/irv.13219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Krusche J., Basse S., and Schaub B., “Role of Early Life Immune Regulation in Asthma Development,” Seminars in Immunopathology 42, no. 1 (Feb 2020): 29–42, 10.1007/s00281-019-00774-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Caballero M. T., Jones M. H., Karron R. A., et al., “The Impact of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Disease Prevention on Pediatric Asthma,” Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 35, no. 7 (Jul 2016): 820–822, 10.1097/INF.0000000000001167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shi T., Ooi Y., Zaw E. M., et al., “Association Between Respiratory Syncytial Virus‐Associated Acute Lower Respiratory Infection in Early Life and Recurrent Wheeze and Asthma in Later Childhood,” Supplement, The Journal of Infectious Diseases 222, no. 7 (Oct 2020): S628–S633, 10.1093/infdis/jiz311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stein R. T., Sherrill D., Morgan W. J., et al., “Respiratory Syncytial Virus in Early Life and Risk of Wheeze and Allergy by Age 13 Years,” The Lancet 354, no. 9178 (Aug 1999): 541–545, 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10321-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sigurs N., Aljassim F., Kjellman B., et al., “Asthma and Allergy Patterns over 18 Years After Severe Rsv Bronchiolitis in the First Year of Life,” Thorax 65, no. 12 (Dec 2010): 1045–1052, 10.1136/thx.2009.121582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sorkness R., R. F. Lemanske, Jr. , and Castleman W. L., “Persistent Airway Hyperresponsiveness After Neonatal Viral Bronchiolitis in Rats,” Journal of Applied Physiology 70, no. 1 (Jan 1991): 375–383, 10.1152/jappl.1991.70.1.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Beigelman A. and Bacharier L. B., “The Role of Early Life Viral Bronchiolitis in the Inception of Asthma,” Current Opinion in Allergy & Clinical Immunology 13, no. 2 (Apr 2013): 211–216, 10.1097/ACI.0b013e32835eb6ef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thomsen S. F., van der Sluis S., Stensballe L. G., et al., “Exploring the Association Between Severe Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection and Asthma: A Registry‐Based Twin Study,” American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 179, no. 12 (Jun 2009): 1091–1097, 10.1164/rccm.200809-1471OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Poorisrisak P., Halkjaer L. B., Thomsen S. F., et al., “Causal Direction Between Respiratory Syncytial Virus Bronchiolitis and Asthma Studied in Monozygotic Twins,” Chest 138, no. 2 (Aug 2010): 338–344, 10.1378/chest.10-0365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jackson D. J., Evans M. D., Gangnon R. E., et al., “Evidence for a Causal Relationship Between Allergic Sensitization and Rhinovirus Wheezing in Early Life,” American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 85, no. 3 (Feb 2012): 281–285, 10.1164/rccm.201104-0660OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chawes B. L. K., Poorisrisak P., Johnston S. L., and Bisgaard H., “Neonatal Bronchial Hyperresponsiveness Precedes Acute Severe Viral Bronchiolitis in Infants,” Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 130, no. 2 (Aug 2012): 354–361.e3, 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.04.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hurley S., Franklin R., McCallion N., et al., “Allergy‐Related Outcomes at 12 Months in the Coral Birth Cohort of Irish Children Born During the First Covid 19 Lockdown,” Pediatric Allergy and Immunology 33, no. 3 (Mar 2022): e13766, 10.1111/pai.13766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ebrahimi S., Khatami S., and Mesdaghi M., “The Effect of COVID‐19 Pandemic on the Infants' Microbiota and the Probability of Development of Allergic and Autoimmune Diseases,” International Archives of Allergy and Immunology 183, no. 4 (2022): 435–442, 10.1159/000520510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Strachan D. P., “Hay Fever, Hygiene, and Household Size,” BMJ (London) Nov 18 299, no. 6710 (1989): 1259–1260, 10.1136/bmj.299.6710.1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.