Abstract

Chronic itch which is primarily associated with dermatologic, systemic, or metabolic disorders is often refractory to most current antipruritic medications, thus highlighting the need for improved therapies. Oxidative damage is a novel determinant of spinal pruriceptive sensitization and synaptic plasticity. The resolution of oxidative insult by molecular hydrogen has been manifested. Herein, we strikingly report that both hydrogen gas (2 %) inhalation and hydrogen-rich saline (5 mL/kg, intraperitoneal) injection prevent and alleviate persistent dermatitis-induced itch, diabetic itch and cholestatic itch. Hydrogen therapy reverses the decrease of spinal SIRT1 expression and antioxidant enzymes (SOD, GPx and CAT) activity after dermatitis, diabetes and cholestasis. Furthermore, hydrogen reduces spinal ROS generation, oxidation products (MDA, 8-OHdG and 3-NT) accumulation, β-catenin acetylation and dendritic spine density in persistent itch models. Spinal SIRT1 inhibition eliminates antipruritic and antioxidative effects of hydrogen, while SIRT1 agonism attenuates chronic itch phenotype, spinal β-catenin acetylation and mitochondrial damage. β-catenin inhibitors are effective against chronic itch via reducing β-catenin acetylation, blocking ERK phosphorylation and elevating antioxidant enzymes activity. Hydrogen treatment suppressed dermatitis and cholestasis mediated spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents in vitro. Additionally, hydrogen impairs cholestasis-induced the enhancement of cerebral functional connectivity between the right primary cingulate cortex and bilateral sensorimotor cortex, as well as bilateral striatum. Taken together, this study uncovers that molecular hydrogen protects against chronic pruritus and spinal pruriceptive sensitization by reducing oxidative damage via up-regulation of SIRT1-dependent β-catenin deacetylation in mice, implying a promising strategy in translational development for itch control.

Keywords: β-catenin, Chronic itch, Hydrogen, Oxidative stress, SIRT1, Synaptic plasticity

1. Introduction

Itch (pruritus) is a common uncomfortable sensation which causes the reflex to scratch [1,2]. Acute itch serves as a warning and self-defense mechanism against irritants that could be hazardous, whereas chronic itch is a debilitating clinical issue that affects approximately 8 %−25.5 % of the population and mainly results from dermatologic diseases (allergic contact dermatitis, psoriasis), systemic disorders (cholestasis, chronic renal failure), and metabolic etiologies (diabetes) [[3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8]]. Although scratching behaviors temporarily alleviate pruritus, the persistent “itch-scratch-itch” cycle usually leads to severe skin lesion, sleep disturbance, neurocognitive dysfunction and psychiatric comorbidities (anxiety and depression) [[9], [10], [11], [12], [13]]. In spite of its clinical importance, substantially less is elucidated about the pathogenesis and therapeutic regimens of pruritus, unlike other somatosensory modalities such as pain.

Recent advances in experimental research have increased our understanding of neurocircuits and neuromodulators in itch perception and conveyance at the spinal level [[14], [15], [16]]. The initiation and maintenance of chronic itch can arise from spinal pruriceptive sensitization which represents considerable neural plasticity of dorsal horn neurons and circuits [[17], [18], [19]]. Oxidative damage has been identified to be a novel determinant of spinal nociceptive and pruriceptive sensitization, as well as excitatory sensory synaptic plasticity [[20], [21], [22], [23]]. Yet, the detailed molecular mechanisms underlying chronic pruritus is still lacking. Nicotinamide adenosine dinucleotide (NAD+)-dependent histone deacetylases sirtuins (SIRTs) 1–7 are characterized as cardinal signaling molecules for the regulation of diverse pathophysiologic processes including oxidative stress, inflammation, autophagy, aging, and apoptosis by deacetylating a range of histone and nonhistone proteins [[24], [25], [26], [27], [28]]. In chronic pain settings, the decreased expression of SIRT1 is a key feature of calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II alpha (CaMKIIa) acetylation in the development of nerve injury-induced pain with vulnerable emotional disorders [29]. Spinal SIRT2 deacetylates forkhead box class O3a (FoxO3a) in the alleviation of bone cancer pain [30]. Also, spinal activation of SIRT3 controls carrageenan-induced inflammatory pain via the deacetylation of manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) in rodent animals [31]. Since pain and itch share certain similar neurocircuits, we explored whether and how SIRTs modification is involved in chronic itch with different etiologies.

Over the past decade, significant progress has been made in the reduction and elimination of oxidative insult and inflammation by medical gas molecular hydrogen with little toxicity [32,33]. Intriguingly, hydrogen gas exhibits excellent neuroprotection and therapeutic potential in multitudinous neurological diseases, including ischemic stroke, traumatic brain injury, multiple sclerosis, postoperative delirium, Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, anxiety, and depression [34,35]. Furthermore, molecular hydrogen therapy is effective against sensory neuronal excitability and spinal nociceptive sensitization in animals with opioid-induced hyperalgesia [36,37], postsurgical pain after plantar incision [38], chemotherapy-induced neuropathic allodynia [39], and morphine-induced antinociceptive tolerance [40]. Nevertheless, whether and how hydrogen gas reduces chronic itch remains unclarified.

In this preclinical study, we identified the anti-pruritic effects and therapeutic targets of molecular hydrogen in chronic itch using three mouse models, including allergic contact dermatitis-induced itch, diabetic itch, as well as cholestatic itch. Since the brain is ultimately responsible for the conscious feeling of pruritus [9,12,13,19], evaluating the anti-itch effects of molecular hydrogen on the brain during a chronic itch condition may provide more insights into how successful anti-itch therapy is. We hereby utilized resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to assess whole-brain functional connectivity in cholestatic itch. Overall, our findings may provide promising avenues for pruritus control and elucidate novel neurobiology of itch chronification.

2. Results

2.1. Allergic contact dermatitis induces chronic itch and reduces SIRT1 expression in the spinal dorsal horn

To investigate the potential involvement of SIRTs in chronic itch, the model of allergic contact dermatitis was employed (Fig. 1A). Firstly, animals undergoing DNFB intervention exhibited the severe skin lesion, which included skin erythema, edema, ulceration and scab (Fig. 1B). Moreover, as compared to olive oil-treated control mice, DNFB application evoked a quick (<3 days) and prolonged (>9 days, the final day of observation) increase in scratching activities (F [1,70] = 1267, P < 0.0001, n = 8, two-way ANOVA, Fig. 1C), demonstrating that chronic itch was successfully caused and persisted following dermatitis. Interestingly, among SIRTs 1–7, we only observed the significant decrease of SIRT1 expression in the spinal dorsal horn of dermatitis-treated mice as compared to naïve mice (F [2,12] = 96.48, P < 0.0001, n = 5, one-way ANOVA, Fig. 1D and E). Spinal SIRT1 activity was also down-regulated following DNFB exposure (F [2,12] = 111.9, P < 0.0001, n = 5, one-way ANOVA, Fig. 1F). Simultaneously, to characterize the cell types for SIRT1 location in the spinal dorsal horn, immunohistochemistry was utilized for examining the colocalization of SIRT1 with a neuronal marker NeuN, microglial marker IBA-1 and astrocytic marker GFAP, respectively. Double staining revealed that SIRT1 greatly co-localized with NeuN but not IBA-1 and GFAP, thus indicating the predominant expression of SIRT1 by the spinal dorsal horn neurons (Fig. 1G). These data imply that spinal SIRT1 may play pivotal roles in chronic itch via neuronal modulation.

Fig. 1.

Allergic contact dermatitis induces chronic pruritus and reduces spinal SIRT1 expression and activity in mice. (A) Protocol of experimental design for the mouse model of DNFB-induced dermatitis itch. The figure was made by BioRender. (B) Images of neck skin appearance on 3 and 7 days after DNFB intervention. (C) Scratching bouts after DNFB exposure. n = 8 mice/group. ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001 vs. group Control. (D and E) Western blot showed the expressions of SIRTs 1–7 in the spinal dorsal horn on 3 and 7 days after DNFB intervention. n = 5 mice/group. ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001 vs. group Naïve. (F) The activity of SIRT1 in the spinal dorsal horn was inhibited on 3 and 7 days after DNFB intervention. n = 5 mice/group. ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001 vs. group Naïve. (G) Double staining of SIRT1 (red) with markers (green) of different cells in the spinal dorsal horn—neuron (NeuN), microglia (IBA-1), and astrocyte (GFAP). Scale bar, 100 μm. Data are expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test (C), and one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test (E, F).

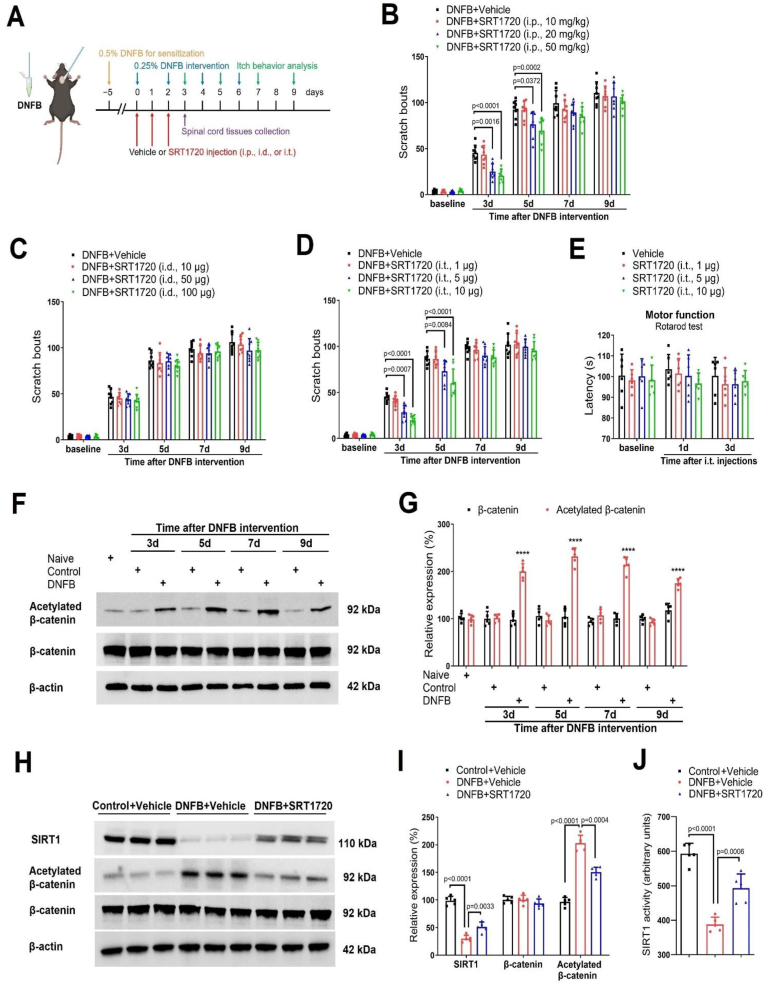

2.2. Spinal SIRT1 cascades are required for dermatitis-induced chronic itch

To determine whether and where SIRT1 activation would impair persistent itch, a specific SIRT1 activator SRT1720 was repeatedly administered daily from days 0–2 after DNFB exposure via intraperitoneal (i.p.), intradermal (i.d.), and intrathecal (i.t.) routes, respectively (Fig. 2A). We first discovered that three injections of SRT1720 (i.p., 10, 20, and 50 mg/kg) reduced DNFB-induced scratching behaviors in a dose-dependent manner (F (3, 140) = 18.45, P < 0.0001, n = 8, two-way ANOVA, Fig. 2B), which its robust anti-itch persisted for 3 days following the third treatment. However, repeated exposures to SRT1720 (i.d., 10, 50, 100 μg) failed to ameliorate itch-like scratch (F (3, 140) = 2.538, P = 0.0591, n = 8, two-way ANOVA, Fig. 2C). Strikingly, mice received repetitive injections of SRT1720 (i.t., 1, 5, and 10 μg) exhibited the decreased scratching activities (F (3, 140) = 23.14, P < 0.0001, n = 8, two-way ANOVA, Fig. 2D). Also, repeated injections of SRT1720 following i.t. route did not affect locomotor activity in dermatitis mice (Fig. 2E), suggesting that the prevention of itch by spinal administration of SRT1720 was not on account of the deficiency in motor function. These detailed data demonstrate that spinal SIRT1 activation is sufficient to reduce chronic itch perception.

Fig. 2.

Spinal SIRT1 activation reduces dermatitis-induced chronic itch and spinal β-catenin acetylation in mice. (A) Experimental design to test the anti-pruritus effect of SIRT1 activator SRT1720 via intraperitoneal (i.p.), intradermal (i.d.), intrathecal (i.t.) injections in the mouse model of DNFB-induced itch. The figure was made by BioRender. (B) i.p. pre-administration of SRT1720 attenuated dermatitis-induced scratching behaviors in a dose-dependent manner. n = 8 mice/group. (C) i.d. pre-administration of SRT1720 did not attenuate dermatitis-induced scratching behaviors. n = 8 mice/group. (D) i.t. pre-administration of SRT1720 attenuated dermatitis-induced scratching behaviors in a dose-dependent manner. n = 8 mice/group. (E) Locomotor function, assessed by Rotarod test, was not impaired by three i.t. injections of SRT1720. n = 6 mice/group. (F and G) Western blot showed the dynamic changes of β-catenin expression and acetylation in the spinal dorsal horn on 3, 5, 7, and 9 days after DNFB intervention. n = 5 mice/group. ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001 vs. group Naïve. (H and I) Western blot showed that i.t. injections of SRT1720 (10 μg) increased SIRT1 expression and reduced β-catenin acetylation on 3 days after DNFB intervention. n = 5 mice/group. (J) The decreased activity of SIRT1 on 3 days after DNFB intervention was increased by SRT1720. n = 5 mice/group. Data are expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test (B–E), and one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test (G, I, J).

2.3. Spinal SIRT1 activation inhibits dermatitis-induced β-catenin acetylation and oxidative stress

The activation of WNT/β-catenin signaling in the spinal dorsal horn has been gradually recognized as critical steps for neuronal excitability and synaptic plasticity in the development of pathologic pain [41,42]. Moreover, hyperactivity of β-catenin depends on its acetylation/deacetylation modification [43,44]. Given that β-catenin is a key downstream target for deacetylation by SIRT1 [[45], [46], [47]], we further explored the possible interaction of SIRT1 and β-catenin in itch neurocircuits. Intriguingly, we detected the rapid and persistent increase of β-catenin acetylation (but not expression) after dermatitis (F [8,36] = 103.8, P < 0.0001, n = 5, one-way ANOVA, Fig. 2F and G), which well-matched the time course of chronic itch behaviors. More importantly, spinal administration of SRT1720 (i.t., 10 μg) increased the expression and activity of SIRT1, and decreased the acetylation levels of β-catenin (Fig. 2H–J). Simultaneously, SRT1720 inhibited reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation (Fig. 3A and B), reduced oxidatively modified molecules (MDA, 8-OHdG and 3-NT) accumulation (Fig. 3C–E), and up-regulated the activity of antioxidant enzymes (CAT, SOD and GPx, Fig. 3F–H) in the spinal dorsal horn after DNFB intervention. Additionally, transmission electron microscopy was utilized to detect ultrastructural alternations in neuronal mitochondria of the dorsal horn (Fig. 3I). The mitochondrial structure of control animals was intact. The neuronal mitochondria after dermatitis were obviously swollen and disintegrated, which was ameliorated by SRT1720 therapies. These findings all suggested that spinal down-regulation of SIRT1 expression and activity contributes to dermatitis-induced chronic itch by increasing β-catenin acetylation, inhibiting antioxidant enzymes activity, and causing oxidative damage.

Fig. 3.

Spinal SIRT1 activation reduces dermatitis-induced spinal oxidative stress in mice. Three intrathecal injections of SRT1720 (10 μg) were performed daily from day 0 to day 2 following DNFB exposure. The dorsal horns of spinal cord were collected on day 3 following DNFB exposure. (A and B) DHE staining detected that SRT1720 reduced spinal ROS generation. n = 5 mice/group. Scale bar, 50 μm. (C–E) ELISA assay showed that SRT1720 reduced spinal oxidation products (MDA, 8-OHdG and 3-NT) accumulation. (F–H) SRT1720 reversed the decreased activity of CAT, SOD and GPx in the spinal dorsal horn. n = 5 mice/group. (I) Transmission electron microscopy was utilized to examine ultrastructural alternations in neuronal mitochondria of the dorsal horn. The mitochondrial structure of control animals was intact (green arrows). The neuronal mitochondria in dermatitis mouse were obviously swollen and disintegrated (blue arrows), which was improved by SRT1720 therapies. Data are expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test (B–H).

2.4. Molecular hydrogen prevents and attenuates dermatitis-induced chronic itch via spinal SIRT1-dependent β-catenin deacetylation

Based on multiple advantages of molecular hydrogen, including selective antioxidant property [32,48], effectively enhancing SIRT1 activity [49,50], as well as cheap and no side-effect for application [33], we then explored the effects of hydrogen on itch phenotype and SIRT1-β-catenin axis. A low concentration (2 %) of hydrogen gas was inhaled for 1 h daily for three days after DNFB exposure (Fig. 4A). Although hydrogen gas therapy did not improve DNFB-caused severe skin lesion (Fig. 4B) and the increased epidermis thickness of the involved skin (Fig. 4C and D), pre-treatment with hydrogen gas (in the initial phase) drastically prevented the dermatitis-induced scratching behaviors for more than five days (F [1,70] = 50.29, P < 0.0001, n = 8, two-way ANOVA, Fig. 4E). Further, we tested the therapeutic potential of post-treatment with hydrogen gas at existing itch. Intriguingly, single inhalation of hydrogen gas on day 7 (in the late phase) following DNFB intervention exhibited a rapid and robust attenuation of the established chronic pruritus (P = 0.0002, n = 8, two-tailed Student's t-test, Fig. 4F). However, we observed no sex differences in DNFB-induced scratching behaviors and anti-pruritic effects of hydrogen between male and female mice (Fig. S1).

Fig. 4.

Hydrogen gas inhalation reduces dermatitis-induced chronic itch but not dermatitis in mice. (A) Experimental design to test the anti-pruritus effect of hydrogen gas in the mouse model of DNFB-induced itch. The figure was made by BioRender. (B) Images of neck skin appearance on 3 days after DNFB intervention and hydrogen inhalation. (C and D) H&E staining showed that the epidermis (↓) thickness of the dermatitis skin after DNFB intervention was not affected by hydrogen inhalation. Scale bar, 50 μm. n = 5 mice/group. ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001 vs. group Control. (E) pre-treatment with hydrogen gas inhalation inhibited the generation of dermatitis-induced scratching behaviors. n = 8 mice/group. (F) One hour inhalation of hydrogen gas on day 7 after DNFB exposure attenuated the existing persistent itch. n = 8 mice/group. Data are expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test (D), two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test (E), and unpaired two-tailed t-test (F).

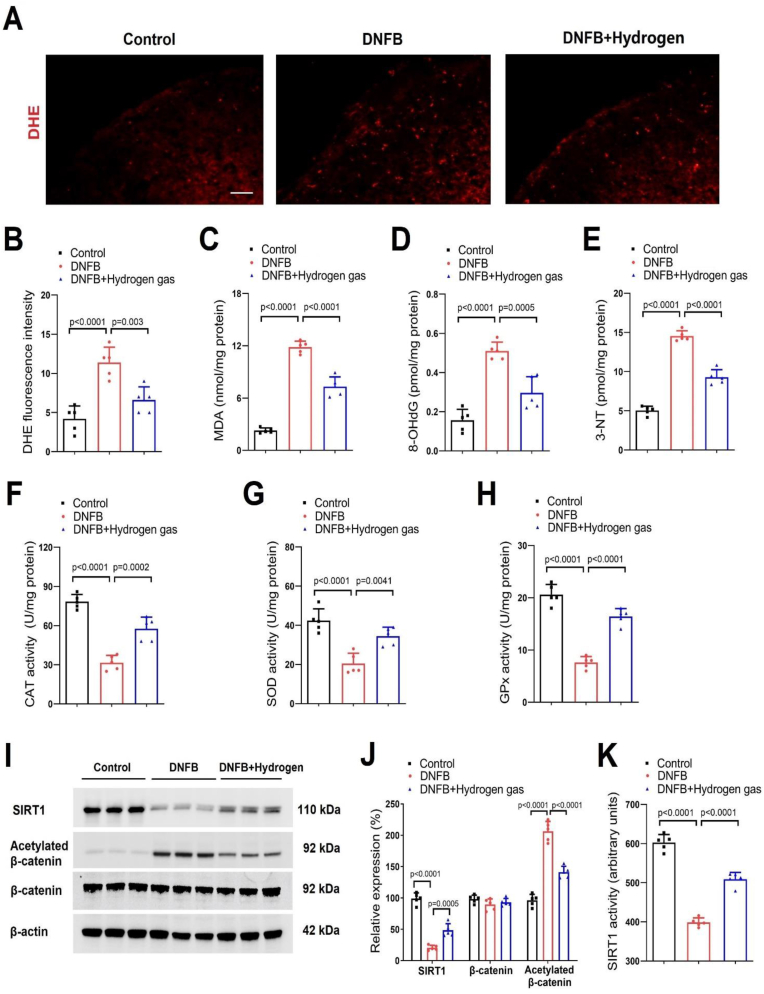

More strikingly, our biochemical experiments (Fig. 5A–K) found that dermatitis-induced decrease of spinal antioxidant enzymes (CAT, SOD, and GPx) activity, and SIRT1 expression and activity on day 3 after DNFB exposure was elevated by hydrogen gas inhalation (Fig. 5F–K). As parallel, the increased production of ROS (Fig. 5A and B), accumulation of oxidation products (MDA, 8-OHdG and 3-NT) (Fig. 5C–E) and acetylation of β-catenin (Fig. 5I and J) in dermatitis mice was inhibited by hydrogen gas inhalation. These detailed results imply that molecular hydrogen therapy may control dermatitis-induced chronic itch via regulating spinal SIRT1-β-catenin-mediated oxidative stress.

Fig. 5.

Hydrogen gas inhalation reduces SIRT1-dependent β-catenin acetylation and oxidative stress in the spinal dorsal horn of mice with dermatitis. Hydrogen gas (2 %) was repeatedly inhaled for 1 h daily from days 0–2 after DNFB exposure. Spinal cord tissues were collected on 3 days after DNFB intervention for biochemical experiments. (A and B) DHE staining detected that hydrogen gas reduced spinal ROS generation. Scale bar, 50 μm. (C–E) ELISA assay showed that hydrogen reduced spinal oxidation products (MDA, 8-OHdG and 3-NT) accumulation. (F–H) Hydrogen gas reversed the decreased activity of CAT, SOD and GPx in the spinal dorsal horn. (I and J) Western blot showed that hydrogen gas increased SIRT1 expression and reduced β-catenin acetylation after DNFB intervention. (K) The decreased activity of SIRT1 after DNFB intervention was reversed by hydrogen gas. n = 5 mice/group. Data are expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test (B–H, J and K).

2.5. Molecular hydrogen reduces chronic itch, increases spinal SIRT1 expression and β-catenin deacetylation in diabetic mice

The prevalence of chronic itch in the diabetic patients is 18.4–43.0 %, which is 2.7 times that of nondiabetic population [23,51], thus emphasizing that the in-depth studies on the specific pathogenesis and therapeutic strategies for diabetic itch are urgently required. Given that more than 90 % diabetes cases are T2DM [52], we further examined the beneficial effects of hydrogen on diabetic itch using a mouse model of HFD-fed/STZ-injection-induced T2DM.

As compared to control mice, FBG (fasting blood glucose) level was considerably increased in STZ-treated mice (Table S1), demonstrating the successful establishment of T2DM model. Then, 2 % hydrogen gas was inhaled for 1 h daily for three days after STZ injections (Fig. 6A). We did not detect any change of FBG level after hydrogen inhalation when compared with T2DM mice (Table S1), implying that hydrogen exerts no beneficial effects on T2DM. However, T2DM-induced scratching activities were dramatically reduced by pre-treatment with hydrogen gas (F [1,70] = 35.06, P < 0.0001, n = 8, two-way ANOVA, Fig. 6B). As parallel, post-treatment with 2 % hydrogen gas on 3 weeks following STZ injections exhibited a statistically significant decrease of the established chronic pruritus (P = 0.0016, two-tailed Student's t-test, Fig. 6C). Also, the therapeutic effect of hydrogen gas on diabetic itch behaviors was indistinguishable between sexes (Fig. S2).

Fig. 6.

Hydrogen gas inhalation reduces diabetic itch, SIRT1-dependent β-catenin acetylation and oxidative stress in the spinal dorsal horn of mice. (A) Experimental design to test the anti-pruritus effect of hydrogen gas in the mouse model of STZ-induced diabetic itch. The figure was made by BioRender. (B) pre-treatment with hydrogen gas inhalation inhibited the generation of diabetes-induced scratching behaviors. n = 8 mice/group. (C) One hour inhalation of hydrogen gas on day 21 after STZ exposure attenuated the existing persistent itch. n = 8 mice/group. (D and E) DHE staining detected that hydrogen gas reduced spinal ROS generation. Scale bar, 50 μm. (F–H) ELISA assay showed that hydrogen reduced spinal oxidation products (MDA, 8-OHdG and 3-NT) accumulation. (I–K) Hydrogen gas reversed the decreased activity of CAT, SOD and GPx in the spinal dorsal horn. (L and M) Western blot showed that hydrogen gas increased SIRT1 expression and reduced β-catenin acetylation after STZ intervention. (N) The decreased activity of SIRT1 after STZ intervention was reversed by hydrogen gas. n = 5 mice/group. Data are expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test (B), unpaired two-tailed t-test (C), and one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test (E-K, M and N).

Intriguingly, hydrogen pretreatment inhibited the spinal increase of ROS generation (Fig. 6D and E) and oxidation products (MDA, 8-OHdG and 3-NT) accumulation (Fig. 6F–H) in diabetic mice. Meanwhile, spinal down-regulations of antioxidant enzymes (CAT, SOD, and GPx) activity, as well as SIRT1 expression and activity in mice with diabetic itch were effectively reversed following hydrogen gas inhalation (Fig. 6I–N). The increase of β-catenin acetylation in the spinal dorsal horn of T2DM mice was also suppressed by hydrogen gas (Fig. 6L and M). These suggest the involvement of SIRT1-β-catenin cascades in the anti-pruritic effect of hydrogen therapy in T2DM-induced peripheral neuropathy (diabetic itch).

2.6. Molecular hydrogen therapy is effective against cholestatic itch via spinal SIRT1-dependent β-catenin deacetylation

Chronic itch was also experienced by around 80%–100 % of patients with cholestatic jaundice, which is a common comorbidity and manifestation of cholestatic liver diseases [3,6]. To subsequently assess the protective role of molecular hydrogen in cholestatic itch, 2 % hydrogen gas was inhaled for 1 h daily from days 11–13 after BDL surgeries (Fig. 7A). The successful development of cholestasis model was verified by increased serum level of total bilirubin, and yellow ear, skin, rear claw as well as liver tissue on day 14 following BDL surgery (Fig. 7B and C). H&E staining also showed the fibrosis, dilatation and neogenesis of small bile ducts, as well as hepatocyte swelling following BDL surgeries (Fig. 7D). Surprisingly, hydrogen gas inhalation generated a long-lasting and robust inhibition of cholestasis-induced scratching activities, which persisted for more than one week (F [1,70] = 50.58, P < 0.0001, n = 8, two-way ANOVA, Fig. 7E). Simultaneously, we observed no sex differences in cholestatic pruritus and anti-itch of hydrogen gas between both sexes (Fig. S3). Moreover, a single inhalation of hydrogen gas on day 21 after BDL significantly restrained the existing scratching behaviors (P = 0.0008, two-tailed Student's t-test, Fig. 7F). In addition, Spinal ROS and oxidation products (MDA, 8-OHdG and 3-NT) accumulation in cholestatic itch was reversed after hydrogen pretreatment (Fig. 8A–E). Mice exhibited the spinal suppression of antioxidant enzymes (CAT, SOD, and GPx) activity, β-catenin deacetylation and SIRT1 expression and activity on day 14 after BDL intervention, which was elevated by pre-administration of hydrogen gas (Fig. 8F–K).

Fig. 7.

Hydrogen gas inhalation reduces cholestatic itch. (A) Experimental design to test the anti-pruritus effect of hydrogen gas in the mouse model of BDL-induced cholestatic itch. The figure was made by BioRender. (B) Serum levels of total bilirubin were measured after sham and BDL surgery. n = 5 mice/group. (C) Images of jaundice on 14 days after BDL surgery. (D) H&E staining showed the fibrosis (→), dilatation and neogenesis of small bile ducts (▲), as well as hepatocyte swelling (black circle) in liver sections following BDL surgery. Scale bar, 20 μm. (E) pre-treatment with hydrogen gas inhalation inhibited the generation of cholestasis-induced scratching behaviors. n = 8 mice/group. (F) One hour inhalation of hydrogen gas on day 21 after BDL surgery attenuated the existing persistent itch. n = 8 mice/group. Data are expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test (B), two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test (E), and unpaired two-tailed t-test (F).

Fig. 8.

Hydrogen gas inhalation reduces SIRT1-dependent β-catenin acetylation and oxidative stress in the spinal dorsal horn of mice with cholestatic itch. Hydrogen gas (2 %) was repeatedly inhaled for 1 h daily from days 11–13 after BDL surgeries. Spinal cord tissues were collected on 14 days after BDL intervention for biochemical experiments. (A and B) DHE staining detected that hydrogen gas reduced spinal ROS generation. Scale bar, 50 μm. (C–E) ELISA assay showed that hydrogen reduced spinal oxidation products (MDA, 8-OHdG and 3-NT) accumulation. (F–H) Hydrogen gas reversed the decreased activity of CAT, SOD and GPx in the spinal dorsal horn. (I and J) Western blot showed that hydrogen gas increased SIRT1 expression and reduced β-catenin acetylation after BDL surgeries. (K) The decreased activity of SIRT1 after BDL surgeries was reversed by hydrogen gas. n = 5 mice/group. Data are expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test (B–H, J and K).

2.7. Spinal SIRT1 inhibition eliminates the anti-pruritic and antioxidant effects of hydrogen in chronic itch conditions

Then, to assess the potential roles of SIRT1 cascades in hydrogen therapy and itch phenotype, a selective SIRT1 inhibitor (EX527) was injected intrathecally and immediately after hydrogen gas inhalation in different mouse models of chronic itch. Biochemical experiments detected that EX527 (10 μg but not 1 μg) effectively down-regulated the enhanced activity of SIRT1 and antioxidant enzymes (CAT, SOD, and GPx) following hydrogen treatment in the spinal dorsal horn of mice with dermatitis (Fig. 9A–D), diabetes (Fig. 9E–H) and cholestasis (Fig. 9I–L), implying that EX527 is sufficient to inhibit SIRT1 activity and antioxidation. Meanwhile, EX527 (10 μg but not 1 μg) significantly inhibited the reduction of oxidation products (MDA, 8-OHdG and 3-NT) by hydrogen treatment after dermatitis (Fig. S4), diabetes (Fig. S5) and cholestasis (Fig. S6). Also, we observed that EX527 (10 μg but not 1 μg) dose-dependently abrogated the therapeutic effects of hydrogen gas on dermatitis-induced itch (Fig. 9M), diabetic itch (Fig. 9N), and cholestatic itch (Fig. 9O). These data all demonstrate that SIRT1-dependent antioxidative response is an important step for the attenuation of persistent pruritus by molecular hydrogen therapy.

Fig. 9.

Spinal inhibition of SIRT1 impairs the anti-itch and antioxidant effects of hydrogen gas in chronic itch conditions. A selective SIRT1 inhibitor (EX527) was injected intrathecally and immediately after 2 % hydrogen gas inhalation in different mouse models of chronic itch. (A–L) EX527 (10 μg) was sufficient to diminish the increased activity of SIRT1, CAT, SOD and GPx in the spinal dorsal horn by hydrogen therapy in mice with dermatitis (A–D), diabetes (E–H) and cholestasis (I–L). n = 5 mice/group. (M–O) EX527 (10 μg) compensated the pruritic alleviation by hydrogen therapy in three mouse models of DNFB-induced itch (M), STZ-induced itch (N), and BDL-induced itch (O). n = 8 mice/group. Data are expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test.

2.8. Pharmacological inhibition of β-catenin signaling attenuates chronic itch after dermatitis, diabetes and cholestasis via reducing spinal pruriceptive sensitization

Next, we examined the direct contribution of β-catenin to central pruriceptive sensitization in chronic itch states. To address this, β-catenin inhibitors XAV939 (i.t., 10 μg) and iCRT14 (i.t., 10 μg) were utilized. Herein, we discovered that both XAV939 and iCRT14 administrations effectively alleviated dermatitis-induced persistent itch (F [2,21] = 53.44, P < 0.0001, n = 8, one-way ANOVA, Fig. 10A), diabetic itch (F [2,21] = 25.88, P < 0.0001, n = 8, one-way ANOVA, Fig. 10B), and cholestatic itch (F [2,21] = 9.429, P = 0.0012, n = 8, one-way ANOVA, Fig. 10C). As parallel, XAV939 and iCRT14 reduced spinal hyperacetylation of β-catenin in mice with dermatitis (Fig. 10D), diabetes (Fig. 10E) and cholestasis (Fig. 10F), suggesting that the beneficial and anti-pruritic effects of XAV939 and iCRT14 might be via the suppression of β-catenin acetylation. Moreover, the phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) in the spinal dorsal horn is an indispensable indicator of central pruriceptive sensitization in pathological itch development [9,[53], [54], [55]]. Strikingly, β-catenin inhibitor XAV939 decreased the spinal up-regulation of phosphorylated ERK after dermatitis (F [2,12] = 37.5, P < 0.0001, n = 5, one-way ANOVA, Fig. 10G), diabetes (F [2,12] = 45.25, P < 0.0001, n = 5, one-way ANOVA, Fig. 10H) and cholestasis (F [2,12] = 28.98, P < 0.0001, n = 5, one-way ANOVA, Fig. 10I). Additionally, β-catenin inhibitor XAV939 exhibited a dramatic increase in the activity of antioxidant enzymes (CAT, SOD, and GPx) following dermatitis (Fig. S7), diabetes (Fig. S8) and cholestasis (Fig. S9). These results therefore imply that pharmacological blockade of β-catenin acetylation is protective against chronic pruritus by spinal control of ERK phosphorylation and oxidative stress.

Fig. 10.

β-catenin signaling inhibitors alleviate chronic itch and spinal ERK phosphorylation after dermatitis, diabetes and cholestasis. β-catenin inhibitors XAV939 (10 μg) and iCRT14 (10 μg) were injected intrathecally in three mouse models of chronic itch conditions. (A–C) Both XAV939 and iCRT14 attenuated the existing DNFB-induced itch (A), STZ-induced itch (B), and BDL-induced itch (C). n = 8 mice/group. (D–F) Western blot showed that both XAV939 and iCRT14 reduced β-catenin acetylation after dermatitis (D), diabetes (E) and cholestasis (F). n = 5 mice/group. (G–I) Western blot showed that XAV939 inhibited spinal phosphorylation of ERK after dermatitis (G), diabetes (H) and cholestasis (I). n = 5 mice/group. Data are expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test.

2.9. Molecular hydrogen inhibits dendritic spine morphogenesis and synaptic functional plasticity in the spinal dorsal horn of mice with chronic itch

Given the cardinal requirement of spinal synaptic plasticity for chronic itch conditions [[17], [18], [19],53], we tested if hydrogen could regulate excitatory synaptic transmission in spinal itch sensation. First, the frequency but not the amplitude of spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSCs) in lamina II neurons of cervical spinal cord slices on day 3 after topical application of DNFB was elevated (P = 0.0071, Fig. 11A–C). Similarly, cholestasis increased the frequency of sEPSCs in lamina II neurons of lumbar spinal cord slices on day 14 after BDL surgery (P = 0.0014, Fig. 11D–F). Moreover, both dermatitis- and cholestasis-caused increases of sEPSCs frequency were impaired by hydrogen gas inhalation (P = 0.0244 and P = 0.0127, Fig. 11A–F), manifesting the suppression of synaptic functional plasticity in chronic itch by molecular hydrogen therapy.

Fig. 11.

Synaptic plasticity in chronic itch was inhibited by pre-treatment with hydrogen gas. Hydrogen gas (2 %) was repeatedly inhaled for 1 h daily from days 0–2 after DNFB application, days 7–9 after STZ injection, and days 11–13 after BDL surgery, respectively. (A) Traces of sEPSCs in lamina IIo neurons of spinal cord slices on day 3 following DNFB intervention in three groups. (B) Frequency and (C) amplitude of sEPSC after DNFB exposure and hydrogen treatment were shown. (D) Traces of sEPSCs in lamina IIo neurons of spinal cord slices on day 14 following BDL surgery in three groups. (E) Frequency and (F) amplitude of sEPSC after BDL surgery and hydrogen treatment were shown. (G–I) Representative photomicrographs showed the spine morphology in the dorsal horn on day 3 after DNFB application, day 10 after STZ injection, and day 14 after BDL surgery, respectively. Scale bar = 5 μm. The density of dendritic spines was evaluated. n = 5 mice/group. Data are expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test.

Recent literatures have emphasized the unique contribution of dendritic spine morphogenesis in sensory synaptic functional plasticity in central sensitization and pain transduction [[56], [57], [58]]. Yet, whether the involvement of dendritic spine morphogenesis in chronic itch remains unknown. Our biochemical results from Golgi staining detected the remarkable increase of spine density following dermatitis (Fig. 11G), diabetes (Fig. 11H) and cholestasis (Fig. 11I). More significantly, hydrogen gas inhalation restrained the elevated number of dendritic spines in mice with dermatitic itch (F [2,12] = 19.01, P = 0.0002, one-way ANOVA, Fig. 11G), diabetic itch (F [2,12] = 43.00, P < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA, Fig. 11H) and cholestatic itch (F [2,12] = 29.96, P < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA, Fig. 11I), demonstrating the impairment of spine structural plasticity by hydrogen gas. Collectively, these findings all imply that molecular hydrogen may control chronic itch through reducing synaptic (structural and functional) plasticity in the spinal dorsal horn.

2.10. Hydrogen-rich saline confers protection against chronic itch following dermatitis, diabetes and cholestasis

Hydrogen-rich solution has recently manifested safety profile and positive efficacy in a number of clinical trials [33]. Since that the inconvenience of hydrogen gas inhalation limits its translational significance in clinics, we also looked into the possibility that hydrogen-rich saline (HRS) could have comparable therapeutic effects in chronic pruritus (Fig. 12). Mice received three injections of HRS (i.p., 5 mL/kg) daily in the early phase after DNFB intervention, STZ injection, and BDL surgery, respectively. As expected, HRS mimicked the anti-pruritic characteristics of hydrogen gas inhalation, reducing the scratching activities in dermatitis-induced itch (F [1,70] = 22.85, P < 0.0001, n = 8, two-way ANOVA, Fig. 12A and B), diabetic itch (F [1,70] = 18.74, P < 0.0001, n = 8, two-way ANOVA, Fig. 12C and D) and cholestatic itch (F [1,70] = 44.03, P < 0.0001, n = 8, two-way ANOVA, Fig. 12E and F). Similarly, post-treatment with single injection of HRS (i.p., 5 mL/kg) dramatically ameliorated the established pruritus with different etiologies, including dermatitis, diabetes and cholestasis (Fig. 12G–I).

Fig. 12.

Hydrogen-rich saline reduces the generation and maintenance of chronic itch in mice. (A, C and E) Experimental design for intraperitoneal (i.p.) therapy of pre-treatment with hydrogen-rich saline (HRS, 5 mL/kg) in three mouse models of DNFB-induced itch (A), STZ-induced itch (C), and BDL-induced itch (E). (B, D and F) Pre-administration of HRS prevented dermatitis-induced scratching behaviors (B), diabetes-induced scratching behaviors (D) and cholestasis-induced scratching behaviors (F). (G–I) Single injection of HRS (i.p., 5 mL/kg) attenuated the existing persistent itch after dermatitis (G), diabetes (H) and cholestasis (I), respectively. n = 8 mice/group. Data are expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test (B, D and F), and unpaired two-tailed t-test (G–I).

2.11. Molecular hydrogen impairs the alternations of brain functional connectivity between region of interest in cholestatic itch

fMRI-based neuroimaging is a highly useful and noninvasive method for determining how the human brain functions under physiological and pathological situations [59]. There is growing interest in applying this method to basic animal research to acquire mechanistic insights into the genesis of dermatitis-induced itch by examining whole-brain activity and functional connectivity (FC) in vivo [54]. Additionally, fMRI is crucial for assessing therapeutic potential following medication delivery, which can improve the success rate of drugs development in studies pertaining to central nervous system [60]. We hereby employed resting-state fMRI to evaluate brain activity and responses to hydrogen therapy in cholestatic itch model (Fig. 13). Intriguingly, we first found the considerable increase of amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation (ALFF) in the right primary cingulate cortex (RPCC) on 14 days after BDL surgery, which was impaired by hydrogen gas inhalation (F [2,18] = 24.33, P < 0.0001, n = 7, one-way ANOVA, Fig. 13A and B). For the FC analysis, we defined the seed region as the cluster of RPCC that showed a significant alteration in ALFF among three groups. Strikingly, we detected the enhanced FC between RPCC and bilateral sensorimotor cortex in mice with cholestatic itch, which was reduced by hydrogen therapy (Fig. 13C and D). Similarly, we also observed the increase of cerebral FC between RPCC and bilateral striatum following BDL surgeries, which these functional network changes were drastically prevented by hydrogen gas inhalation (Fig. 13C and D).

Fig. 13.

Hydrogen gas prevents the changes of cerebral functional connectivity in cholestatic pruritus in mice. Hydrogen gas (2 %) was repeatedly inhaled for 1 h daily from days 11–13 after BDL surgery. Resting-state fMRI was utilized to evaluate brain activity and responses to hydrogen therapy on day 14 after BDL surgery. (A and B) fMRI showed the differences of amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation (ALFF) in the right primary cingulate cortex (RPCC) between three groups. (C and D) The differences of functional connectivity (FC) between RPCC and regions of interest (sensorimotor cortex and striatum) were examined between groups on day 14 following BDL surgery. Color bar in A and C shows the F values. n = 7 mice/group. Data are expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test.

3. Discussion

The unidentified mechanisms underlying chronic itch impede the advancement of anti-pruritic therapies [9,10,14,20]. In this present investigation, initial characterization of three mouse models (dermatitis, diabetes, and cholestasis) recapitulates the development of chronic itch behaviors concomitantly with the decreased expression and activity of SIRT1, and the increased acetylation of β-catenin in the spinal dorsal horn neurons, as well as the occurrence of hallmarks of central pruriceptive sensitization including ERK phosphorylation, morphological alterations of dendritic spines, and the increase of sEPSCs frequency. The central findings of this research are that molecular hydrogen therapy confers protection against chronic pruritus by inhibiting oxidative insults and synaptic plasticity through SIRT1-β-catenin axis in the dorsal horn of spinal cord (Fig. 14). Collectively, our results uncover a previously unrecognized advantage of molecular hydrogen in the management of itch with different etiologies.

Fig. 14.

Schematic illustration of the proposed antipruritic mechanism of molecular hydrogen in chronic itch in mice. The itch-specific neuropeptides released from the central terminal of pruriceptive primary afferent after dermatitis, diabetes and cholestasis cause the hyperexcitability of postsynaptic neurons in the spinal dorsal horn, inhibiting neuronal SIRT1 expression and activity. Inactivated SIRT1 facilitates β-catenin hyperacetylation, which drives ERK phosphorylation, ROS accumulation, as well as the reduction of antioxidant enzymes (SOD, GPx and CAT) activity. These may aggravate neuronal oxidative stress and promote dendritic spines morphogenesis and excitatory synaptic transmission, which all contribute to the development of dermatitis-induced itch, diabetic itch and cholestatic itch. More importantly, molecular hydrogen gas enhances SIRT1-dependent β-catenin deacetylation to impair oxidative stress, spinal pruriceptive sensitization and synaptic plasticity, thereby achieving itch-relief. The figure was made by BioRender.

Post-translational protein modification during oxidative stress is a basic process in excitatory neurotoxicity and synaptic plasticity in the dorsal horn of spinal cord, which is further implicated in central sensitization-mediated somatosensory modalities (pain and itch) [[20], [21], [22], [23],36]. The deacetylation of β-catenin by SIRT1 is gradually recognized as the therapeutic targets for oxidation-associated neurological disorders, such as ischemic stroke [61], manganese-induced developmental neurotoxicity [46], and spinal cord injury [62]. Yet, little is known about the link among SIRT1, β-catenin and oxidation in spinal neurocircuits of itch. In our present study, one of the most intriguing findings is that β-catenin cascade is an important downstream effector of SIRT1 activation for controlling chronic itch. Specifically, the decreased expression and activity of SIRT1 in the spinal dorsal horn neurons are highly correlated with the hyper-acetylation of β-catenin in mice with dermatitis, diabetes and cholestasis. Intraperitoneal administration of SIRT1 activator is effective in preventing dermatitis-induced chronic itch. Moreover, we, for the first time, demonstrate that intrathecal (but not intradermal) treatment with SIRT1 activator recapitulated all anti-pruritic effects of systemic therapy with SIRT1 activator. Simultaneously, SIRT1 agonism decreases spinal β-catenin acetylation, ROS generation, oxidation products (MDA, 8-OHdG and 3-NT) accumulation, as well as mitochondria damage in dermatitis-induced chronic itch. In addition, SIRT1 activation increases the activity of antioxidant enzymes (CAT, SOD and GPx) in the spinal dorsal horn of mice with dermatitis. Finally, this is the first research in which β-catenin inhibitors reduce chronic itch phenotypes, the acetylation of β-catenin, the phosphorylation of ERK and neuronal oxidative stress in the spinal dorsal horn following dermatitis, diabetes and cholestasis. Mechanistically, all of these findings in our study are consistent with previous reports regarding the role of SIRT1 and β-catenin in the pathogenesis of chronic pain with different etiologies [41,42,63], further verifying that pain and itch share some striking neurocircuits. Our findings have also shed new light on neuromodulation of chronic pruritus by oxidative insult from a molecular perspective. While our results strongly imply that SIRT1 activation could be a useful strategy for blocking β-catenin acetylation to regulate persistent pruritus states, further investigation is still necessary to determine the precise mechanisms underlying these molecular alterations, behavioral patterns, and malfunctioning neurocircuits in pruritus.

Molecular hydrogen is well identified to be safe with few adverse effects in experimental and clinical trials [[32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40]]. Furthermore, our previous studies confirmed that 2 % hydrogen inhalation for 1 h is safe and has no effect on lung histological changes and oxygenation index in mice [64,65]. Hydrogen is a selective antioxidant which eliminates cytotoxic oxygen radicals more effectively than other ROS scavengers, such as vitamin E and SOD [32]. Inhaling hydrogen gas, injecting HRS, drinking hydrogen-rich water, and directly incorporating hydrogen through diffusion via eye drops are the primary methods to absorb or consume molecular hydrogen [33]. A recent literature by Li and colleagues has validated the alleviation of postoperative pain by HRS via scavenging ROS in a mouse model of plantar incision surgery [38]. Another report has revealed that HRS reduces mechanical allodynia via inhibiting the expressions of myeloperoxidase, protein carbonyl, and maleic dialdehyde in a rat model of chronic constriction injury [66]. Consistently, our previous studies have highlighted that HRS attenuates remifentanil-induced post-surgical hyperalgesia through suppressing spinal peroxynitrite production and MnSOD nitration [36,37]. Herein, we provided several lines of evidence to emphasize the therapeutic effect and underlying targets of molecular hydrogen therapy in chronic itch with multiple etiologies. First, both hydrogen gas inhalation and HRS injection are sufficient to prevent and attenuate dermatitis-induced chronic itch, diabetic itch, and cholestatic itch. Second, hydrogen exposure up-regulates the expression and activity of SIRT1, down-regulates the acetylation of β-catenin, enhances the activity of antioxidant enzymes, and reduces the generation of ROS and oxidation products in the spinal dorsal horn of mice with chronic itch conditions. Third, hydrogen treatment diminishes dermatitis- and cholestasis-induced the increase in spinal sEPSCs frequency in vitro. Fourth, hydrogen mitigates spinal generation of dendritic spines in chronic itch following dermatitis, diabetes and cholestasis. Fifth, the enhancement of cerebral functional connectivity between the right primary cingulate cortex and bilateral sensorimotor cortex/striatum in cholestasis model are impaired by hydrogen. Sixth, anti-pruritic and anti-oxidative characteristics of hydrogen are all compromised and abolished by spinal inhibition of SIRT1. Taken together, these behavioral, biochemical, and electrophysiological findings, for the first time, identify that molecular hydrogen protects against the initiation and maintenance of chronic pruritus by increasing spinal SIRT1-dependent β-catenin deacetylation to inhibit oxidative insult, spine morphogenesis and synaptic plasticity (Fig. 14). Supporting these data, the enhancement of SIRT1 activity by hydrogen treatment has been recently recapitulated in several pathological process [32,49,50]. Nevertheless, we did not elucidate how hydrogen increases spinal SIRT1 expression and activity in itch-responsive neurons. Actually, DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) and transcription factor P53 are reported to be important epigenetic modulators that regulates SIRT1 expression [25,67]. The NAD+/NADH ratio and post-translational modifications (such as ubiquitination, phosphorylation and S-nitrosylation) are critical for the regulation of SIRT1 activity [25,67]. Therefore, it will be interesting to explore the specific mechanism how hydrogen regulates spinal SIRT1 cascades in chronic itch conditions in further mechanistic studies. Additionally, our previous report has indicated the powerful inhibitory control of morphine-induced acute itch and dermatitis-induced chronic itch by STING (stimulator of interferon genes) agonism and IFN-I (type I interferon) activation via down-regulating neuroinflammation-dependent neuronal excitotoxicity [54]. Given the special anti-neuro-inflammatory function of hydrogen gas in the treatment for pain [34,35,38,40], it will be of great interest to explore the possibility that STING-dependent IFN-I response is potential therapeutic targets for the anti-itch and anti-inflammation of hydrogen in future.

One advance in the characteristics of spinal cord itch-coding neurons is the discovery that the interaction between a key itch-specific neuropeptide gastrin-releasing peptide (GRP) and its receptor GRPR in the spinal dorsal horn activates GRPR-expressing pruriceptive neurons that accounts for spinal sensation and transduction of peripheral itch information [14,15,18,68]. In addition to GRPR-expressing excitatory neurons, another primary component of spinal pruriceptive circuitry has been elucidated [10,19,53]. Pharmacologic and chemogenetic activation of spinal inhibitory neurons expressing gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) abolishes acute and chronic itch-like scratching behaviors, representing the dramatic inhibition of pruriceptive neurocircuits by GABAergic interneurons [19,69]. Similarly, pharmacogenetic activation of spinal dynorphin-expressing inhibitory neurons considerably ameliorates pruritogen-evoked pruritic behaviors, emphasizing the critical roles of dynorphin-expressing neurons in gating pruriceptive processing [19,70]. Our present study revealed the predominant distribution of SIRT1 by dorsal horn neurons, but not astrocytes and microglial cells. However, one main limitation of our work is inability to determine whether spinal SIRT1 is expressed on GRPR-expressing excitatory neurons and GABAergic inhibitory neurons and test the functional interaction between SIRT1, GRPR and GABA in our itch models. Moreover, at the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) level, a subpopulation of Mas-related G protein–coupled receptor A3 (MrgprA3)–expressing primary sensory neurons are considered to be selectively transmit itch signals to the spinal cord, supporting the existence of itch-specific neurons and the selectivity theory of anti-itch therapies [16,71]. Accordingly, additional research may be required to evaluate whether these itch-specific neurotransmitters and neurons in the DRG are potential targets for anti-pruritus of hydrogen. Another possible limitation is that we failed to investigate how spinal oxidative insult mediates spine morphogenesis and synaptic plasticity in the pathogenesis of chronic itch. We previously highlighted that oxidative stress facilitates neuronal iron accumulation to induce and sustain synaptic plasticity in pathological pain [37], Given the contribution of spinal iron overload to dermatitis-induced itch and cholestatic itch [72], it is possible that neuronal iron accumulation emerges as critical components in facilitating oxidation-associated central pruriceptive sensitization in the development of chronic itch. Finally, these positive findings may not be representative for alloknesis (mechanical itch) [19,53,54] and lymphoma-induced neuropathic itch [17,53], which should be addressed by future prospective investigations.

4. Conclusion

In summary, utilizing three validated murine models of chronic itch, this preclinical research underscores an unexplored pharmacological characteristic of molecular hydrogen in the attenuation of itch by targeting SIRT1-β-catenin pathway to modulate spinal oxidative stress and synaptic plasticity, and subsequent cerebral functional connectivity. Consequently, hydrogen therapy, SIRT1 activation and β-catenin inhibition may represent promising options to alleviate itch with different etiologies.

5. Experimental section

Animals: Male and female adult C57BL/6J mice, aged 8–10 weeks, were housed in a 12-h light-dark cycle that was artificially controlled and provided with unlimited access to food and water. Every animal was acquired from the Chinese Academy of Military Medical Science's experimental animal center. Approved by the Tianjin Medical University General Hospital's Animal Ethical and Welfare Committee (Tianjin, China), all experimental research and protocols were carried out strictly in compliance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The behavioral data was gathered by researchers who were blind to the treatments. Prior to any baseline testing, the animals had a minimum of two days of daily acclimation to the testing conditions. Throughout every trial, the room temperature and humidity stayed constant.

Drug and Administration: The 1-Fluoro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (DNFB; Cat. D1529) and streptozotocin (STZ; Cat. 572201) were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). A specific SIRT1 agonist SRT1720 (Cat. ab273598) and a selective SIRT1 inhibitor EX527 (ab141506), were from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). β-catenin inhibitors XAV939 (HY15147) and iCRT14 (HY16665) were from MedChemExpress (Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA). Intrathecal injection involves puncturing the spinal cord with a 30-gauge needle between the L4 and L5 levels to provide medicines (5 μl) into the cerebral spinal fluid [54,58,72].

Molecular hydrogen therapy: For hydrogen gas inhalation, the animals were placed in a sealed Plexiglas box with inflow and outflow outlets. Hydrogen gas was introduced into the air at a rate of 4 L/min using a TF-1 gas flow meter (Yutaka Engineering Corp.,Tokyo, Japan). The oxygen was administered and kept at 21 % in the box, which was continuously monitored with a gas analyzer (Medical Gas Analyzer LB-2, Model 40 M; Beckman Coulter, Inc, Fullerton, CA, USA). Using a HY-ALERTA Handheld Detector Model 500 (H2Scan, Valencia, CA, USA), the content of hydrogen gas was continuously monitored in the box and kept at 2 % throughout the duration of the therapy. Baralyme was used to extract the carbon dioxide from the box. Animals without hydrogen gas treatment were kept in the same box with the air at a rate of 4 L/min. The concentration and duration of hydrogen inhalation in current study were selected based on previous reports [34,48,64,65] and our preliminary investigations.

The process of preparing HRS was followed by our previous reports [36,37,40]. Briefly, using a hydrogen-rich water generating system (YUTAKA Engineering Co., Tokyo, Japan), hydrogen was dissolved in normal saline for 6 h at high pressure (0.4 MPa) until it reached a supersaturated level. Saturated HRS was kept in an aluminum bag at 4 °C under atmospheric pressure, sanitized with gamma radiation, and freshly manufactured every time to maintain a consistent concentration of greater than 0.6 mmol/L.

Mouse models of chronic itch

Dermatitis-induced chronic itch: Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) model of chronic itch was produced by applying DNFB to the neck skin, as previously documented [72]. In particular, DNFB was dissolved using a 4:1 ratio of acetone to olive oil. The skin of the shaved abdomen in mice was topically administered with 50 μl of 0.5 % DNFB to make them sensitive. Following a 5-day period, animals were painted 30 μl of 0.25 % DNFB to the shaved nape of their necks. This was subsequently administered on days 2, 4, and 6. After applying DNFB to the neck skin, the impulsive scratching behaviors were monitored for 60 min on days 3, 5, 7, and 9. A scratch was defined as elevating the hind paw and scratching the applied neck before dropping it to the ground. Scratching bouts were blindly counted for an hour.

Diabetes-induced chronic itch: Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) model was generated by high-fat diet (HFD) feeding and STZ injections [73]. Specifically, the mice were fed with HFD (60 % fat, 20 % protein and 20 % carbohydrates) for 8 weeks. Then, STZ (65 mg/kg, dissolved in 0.1 mol/L citrate buffer [pH 4.5]) was intraperitoneally injected for 3 consecutive days. After three days, fasting blood glucose (FBG, 12-h fasting) ≥ 7.8 mmol/L or postprandial blood glucose (PBG) ≥ 11.1 mmol/L was diagnosed as diabetic and proceeded to feed with HFD. Control mice received a normal diet and injections with an equivalent volume of vehicle solution. Body weights and blood glucose levels were measured weekly after STZ injection. After the T2DM model was established, scratching bouts were blindly counted for an hour. A scratch was defined as lifting the hind paw to scratch any region of body before returning the paw to the floor.

Cholestasis-induced chronic itch: A mouse model of bile duct ligation (BDL) surgically leads to cholestasis and induces chronic itch [72]. In brief, animals were sevoflurane-anesthetized (induction, 3.0 %; operation, 1.5 %) through a nose mask on the operating table at a controlled temperature of 37 °C. Following abdominal shaving, disinfection and 2-cm midline laparotomy, the common bile duct was revealed and ligated using 4-0 braided silk sutures between the right and caudate lobes. Sham operation was carried out identically with no BDL. On day 14 after BDL surgery, the unbroken ligature, increasing blood total bilirubin levels, and proximal dilatation of the common bile duct all confirmed cholestasis. Scratching bouts were blindly counted for an hour.

Western blot: Animals were sacrificed under deep anesthesia with sevoflurane. The cervical (for dermatitis model) and lumbar (for diabetes and cholestasis model) segments of spinal cord was quickly removed and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Samples were mechanically homogenized in ice-cold radioimmune precipitation assay buffer with phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). The bicinchoninic acid assay test was utilized to assess the amount of protein. The loading and blotting of an identical quantity of total proteins were validated using a membrane coated with a monoclonal mouse anti-β-actin antibody (1:5000; Sigma-Aldrich). After being separated on a 10 % SDS-PAGE gel, samples were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, probed with rabbit antibodies against SIRT1 (1:1000, Cat. ab12193, Abcam), SIRT2 (1:1000, Cat. ab67299, Abcam), SIRT3 (1:1000, Cat. ab189860, Abcam), SIRT4 (1:1000, Cat. ab231137, Abcam), SIRT5 (1:1000, Cat. ab105040, Abcam), SIRT6 (1:1000, Cat. ab62739, Abcam), SIRT7 (1:1000, Cat. ab259968, Abcam), β-catenin (1:1000, Cat. ab32572, Abcam), and acetyl Lysine (1:1000, Cat. ab80178, Abcam), then incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (1:2000, Jackson Immuno Research). The secondary antibodies bound to the membrane were quantified using Image-Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics Inc.) and observed with enhanced chemiluminescence (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA).

Immunohistochemistry: Sevoflurane was used to deeply anesthetize the animals before they were perfused with PBS (phosphate-buffered saline) into the ascending aorta, followed by 4 % paraformaldehyde (PFA) with 0.1 % picric acid in 0.16 M phosphate buffer. The spine chord (30 μm, free-floating) was cut using a cryostat. The sections were first blocked with 1 % BSA and 0.1 % Triton X 100 for 1 h at room temperature before being treated with the primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. The primary antibodies used were: anti- SIRT1 (1:100), anti-NeuN (1:200, Abcam), anti-GFAP (1:200, Cell Signaling Technology), and anti-IBA-1 (1:200, Abcam). After three rinses with PBS, the sections were incubated with a fluorescence-labeled secondary antibody for 1 h. Images were captured with a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Japan).

SIRT1 deacetylase activity: SIRT1 deacetylase activity was measured using the SIRT1 Fluorometric Drug Discovery Kit (Enzo Life Sciences; BML-AK555). Immunoprecipitation was utilized for SIRT1 protein extraction. The reaction was done at 37 °C after adding assay buffer, SIRT1, and substrate sequentially. Ultimately, this procedure was ended by using Developer II. The microplate reader continually monitored the fluorescence intensity at 360 nm excitation and 460 nm emission wavelengths.

ROS Measurement: Dihydroethidium (DHE, S0063, Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) was utilized to measure spinal ROS generation in situ. To be more precise, OCT-embedded spinal cord samples were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Using a cryostat, tissues were sectioned at a thickness of 14 μm and arranged on glass slides. After that, samples were kept out of the light for 15 min at 37 °C while being incubated with 5 μmol/L DHE. Following PBS washing, a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Japan) was used to take pictures. Image J was employed to quantify DHE fluorescence intensity in spinal dorsal horn sections.

Oxidative stress biomarkers: An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was utilized for measuring the contents of classical oxidation products, including malondialdehyde (MDA) as an indicator of lipid peroxidation, 8-hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) as a product of DNA oxidation, and 3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT) as a marker of peroxynitrite-mediated protein nitration. Experiments were performed with the commercial ELISA kits: MDA (A003-1, Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Jiangsu, China), 3-NT (EKF57991, Biocat, Heidelberg, Germany) and 8-OHdG (CSB-E10527 m, Cusabio, Hertfordshire, UK). Spinal tissues were homogenized, centrifuged and then the supernatant was collected. After determination of protein concentrations by BCA Protein Assay (Pierce), 100 μg of proteins of samples were used for each reaction in a 96-well plate. All ELISA experiments followed the manufacturer's protocol. The optical densities of samples were measured using an ELISA plate reader (Bio-Rad) and the contents of these biomarkers were calculated using the standard curves.

Antioxidant enzymes activity: Essential antioxidants like CAT (catalase), SOD (superoxide dismutase) and GPx (glutathione peroxidase) scavenge free radicals and hence reduce the severity of oxidative stress. The activity of CAT, SOD and GPx was evaluated using commercial kits (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology), including Catalase Assay Kit (S0051), Total Superoxide Dismutase Assay Kit with NBT (S0109) and Glutathione Peroxidase Assay Kit (S0056). Experiments were determined in accordance with the instructions of manufacturer.

Transmission Electron Microscopy: Utilizing Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM), the morphology of the spinal mitochondria was examined. Under deep anesthesia, mice were perfused with 0.1 M PBS, 4 % PFA, and 2 % glutaraldehyde, and then their cervical spinal cords were removed. Samples of spinal tissue were sliced into 100 nm-thick ultrathin slices, and then stained with lead citrate and uranyl acetate. A JEM1400 TEM (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) was used to investigate ultrathin slices.

Golgi staining: The freshly dissected spinal dorsal horns were submerged in 20 mL of a Golgi-Cox solution at room temperature for two weeks, as previously mentioned [[56], [57], [58]]. To improve the pliability, the dorsal horns were then submerged in 30 % sucrose for at least two days. Sections measuring 100 μm were positioned on 2 % gelatinized microscope slides, followed by a 1-min rinsing in distilled water, a 30-min dark soak in ammonium hydroxide, another 1-min rinsing in distilled water, and a 30-min picture capture period in Kodak Fix. The slides were then rinsed for 1 min with distilled water, 1 min with 50 % alcohol, 1 min with 70 % alcohol, 1 min with 95 % alcohol, twice with 100 % alcohol for 5 min, and 15 min with a solution of 100 % alcohol and xylene. Permount was used to cover-slip the slides. An Olympus Eclipse 80i microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was used to acquire the pictures. Each dendritic spine was individually counted and traced in order to study its morphologies.

Patch-clamp recordings in Spinal cord slices: Preparing spinal cord slices and patch-clamp recordings was done in accordance with earlier reports [17,56,58]. In short, the mice were euthanized with 3 % sevoflurane, then the spinal cord segment and maintained in pre-oxygenated, refrigerated artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF). A vibrating microslicer was utilized for cutting transverse slices ranging from 400 to 600 μm. Before the experiment, the slices were perfused with an oxygen-containing aCSF at 36 °C for 1 h. Whole cell patch-clamp recordings were made from lamina II neurons using voltage-clamp mode. Neurons were set at −70 mV to capture sEPSCs after the whole-cell setup was established. A micropipette's resistance ranged from 3 to 8 MΩ. Membrane currents were amplified in voltage-clamp mode using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments). 2 kHz filtration and 5 kHz digitization were applied to the signals. pCLAMP 10 software was used for storing the data, and Mini Analysis (Synaptosoft Inc.) was used for analysis.

Resting-state fMRI: MRI data were collected using a 9.4 T Biospec 94/30 preclinical system (Bruker, Ettlingen, Germany), equipped with a gradient coil with a 12-cm inner diameter, a maximum gradient strength of 660 mT/m, and a 4-channel mouse head coil.

For MRI data acquisition, mice were initially anesthetized with 3–5% isoflurane in an oxygen-rich environment and given an intraperitoneal bolus injection of dexmedetomidine at a dose of 0.03 mg/kg. Then, mice were placed prone with their head fixed with a tooth bar and ear bars. Their physiological conditions, including respiration rate, heart rate and pulse oxygen saturation, were monitored (SA Instruments, Stony Brook, NY, USA), and their core body temperature was controlled to 37 ± 0.5 °C using a controlled warm water system (Thermo Scientific SC100, Waltham, MA, USA). During MRI scanning, dexmedetomidine was continuously infused intraperitoneally at a dose of 0.015 mg/kg/h and isoflurane was reduced to 0.5–0.75 %. High-resolution T2-weighted images were acquired using 2D TurboRARE sequence with the following parameters: repetition time (TR) = 2900 ms; echo time (TE) = 33.0 ms; slice thickness = 0.5 mm; slices = 15; flip angle = 90°; field of view (FOV) = 20 mm × 20 mm; matrix = 256 × 256. fMRI data were acquired using 2D T2star.FID.EPI sequence with the following parameters: TR = 1500.0 ms; TE = 18.0 ms; slice thickness = 0.50 mm; slices = 43; flip angle = 90°; FOV = 18 mm × 18 mm; matrix = 256 × 256; and 300 vol

The fMRI data were preprocessed by SPM8 (www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm), MATLAB (Version 2015b, MathWorks, USA), and data processing and analysis of brain imaging (DPABI) V6.0. Briefly, fMRI data were converted to NIFTI format, and the voxel size was scaled up by a factor of 10 to fit standard neuroimaging software packages designed for human brain imaging. After removing the first 10 vol, slice timing and realignment were performed by DPABI. The realigned fMRI images were co-registered to their corresponding T2-weighted images and were then normalized to The Turone Mouse Brain Template and Atlas (TMBTA) in standard space. Finally, spatial smoothing (FWHM = 6 mm), regression of motion parameters and the signals of white matter and cerebrospinal fluid, and bandpass filtering (0.01–0.1 Hz) were carried out by DPABI.

Previous preprocessed results were used for the amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation (ALFF) analysis. For a given voxel, we performed a fast Fourier transform so that the time sequences were transformed to the frequency series, and then calculated the power spectrum's square root. The ALFF value was defined as the average square root. We subtracted the average ALFF value from each voxel's ALFF value and then divided the result by the whole-brain ALFF map's standard deviation; in this way, the standard ALFF value was obtained in order to reduce individual differences among the mice. These analyses were performed using the DPABI software.

Per the ALFF results, the region of interest (ROI) was the region that was significantly different among groups. Subsequently, Pearson's correlation coefficients between the time courses for each ROI and the signal time series for each voxel across the whole brain were calculated to generate ROI-FC map for each mouse. A Fisher's r-to-z transformation was conducted for the said map to generate a z-score FC map for an improved normality of correlation coefficients. The DPABI software was used for these analyses.

Quantification and Statistics: Sample sizes were estimated based on earlier research for analogous types of behavioral and biochemical assessments [54,55,72]. The animals were divided into several experimental groups at random. Each group contained both males and females in a sex-matched manner. Since no sex differences were identified in crucial behavioral assays, data from both sexes were merged and used equally throughout this research (Supplemental Figs. S1–S3). All data were presented as mean with standard deviation (SD), and with no data removed for observation and statistics. Differences between groups were examined utilizing a two-tailed Student's t-test, one-way or two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test. P-values less than 0.05 were the threshold for statistical significance.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Linlin Zhang: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Project administration, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Conceptualization. Fangshi Zhao: Writing – original draft, Validation, Methodology, Investigation. Yize Li: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Investigation. Zhenhua Song: Software, Methodology, Investigation. Lingyue Hu: Validation, Software, Methodology. Yuanjie Li: Visualization, Validation, Software, Methodology, Data curation. Rui Zhang: Visualization, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation. Yonghao Yu: Validation, Supervision, Formal analysis, Data curation. Guolin Wang: Supervision, Formal analysis, Data curation. Chunyan Wang: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

L. Zhang, F. Zhao, and Y. Li contributed equally to this work. This work was supported by research grants of National Natural Science Foundation of China to Linlin Zhang (Grant no. 82171205 and 81801107).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2024.103472.

Contributor Information

Linlin Zhang, Email: linlinzhang@tmu.edu.cn.

Chunyan Wang, Email: 0208wcy@163.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.LaMotte R.H., Dong X., Ringkamp M. Sensory neurons and circuits mediating itch. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2014;15:19–31. doi: 10.1038/nrn3641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bautista D.M., Wilson S.R., Hoon M.A. Why we scratch an itch: the molecules, cells and circuits of itch. Nat. Neurosci. 2014;17:175–182. doi: 10.1038/nn.3619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roh Y.S., Choi J., Sutaria N., Kwatra S.G. Itch: epidemiology, clinical presentation, and diagnostic workup. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2022;86:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.07.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Furutani K., Chen O., McGinnis A., Wang Y., Serhan C.N., Hansen T.V., Ji R.R. Novel proresolving lipid mediator mimetic 3-oxa-PD1n-3 docosapentaenoic acid reduces acute and chronic itch by modulating excitatory and inhibitory synaptic transmission and astroglial secretion of lipocalin-2 in mice. Pain. 2023;164:1340–1354. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tseng P.Y., Hoon M.A. Oncostatin M can sensitize sensory neurons in inflammatory pruritus. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021;13 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abe3037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Y., Wang Z.L., Yeo M., Zhang Q.J., López-Romero A.E., Ding H.P., Zhang X., Zeng Q., Morales-Lázaro S.L., Moore C., Jin Y.A., Yang H.H., Morstein J., Bortsov A., Krawczyk M., Lammert F., Abdelmalek M., Diehl A.M., Milkiewicz P., Kremer A.E., Zhang J.Y., Nackley A., Reeves T.E., Ko M.C., Ji R.R., Rosenbaum T., Liedtke W. Epithelia-sensory neuron cross talk underlies cholestatic itch induced by lysophosphatidylcholine. Gastroenterology. 2021;161:301–317.e16. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.03.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng R.X., Feng Y., Liu D., Wang Z.H., Zhang J.T., Chen L.H., Su C.J., Wang B., Huang Y., Ji R.R., Hu J., Liu T. The role of Nav1.7 and methylglyoxal-mediated activation of TRPA1 in itch and hypoalgesia in a murine model of type 1 diabetes. Theranostics. 2019;9:4287–4307. doi: 10.7150/thno.36077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li S., Andoh T., Zhang Q., Uta D., Kuraishi Y. β2-Microglobulin, interleukin-31, and arachidonic acid metabolites (leukotriene B4 and thromboxane A2) are involved in chronic renal failure-associated itch-associated responses in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019;847:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2019.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mu D., Deng J., Liu K.F., Wu Z.Y., Shi Y.F., Guo W.M., Mao Q.Q., Liu X.J., Li H., Sun Y.G. A central neural circuit for itch sensation. Science. 2017;357:695–699. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf4918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong X., Dong X. Peripheral and central mechanisms of itch. Neuron. 2018;98:482–494. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang T.B., Kim B.S. Scratching beyond the surface of itchy wounds. Immunity. 2020;53:235–237. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li J.N., Wu X.M., Zhao L.J., Sun H.X., Hong J., Wu F.L., Chen S.H., Chen T., Li H., Dong Y.L., Li Y.Q. Central medial thalamic nucleus dynamically participates in acute itch sensation and chronic itch-induced anxiety-like behavior in male mice. Nat. Commun. 2023;14:2539. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-38264-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang S., Wang Y.S., Zheng X.X., Zhao S.L., Wang Y., Sun L., Chen P.H., Zhou Y., Tin C., Li H.L., Sui J.F., Wu G.Y. Itch-specific neurons in the ventrolateral orbital cortex selectively modulate the itch processing. Sci. Adv. 2022;8 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abn4408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Z.F. A neuropeptide code for itch. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2021;22:758–776. doi: 10.1038/s41583-021-00526-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barry D.M., Liu X.T., Liu B., Liu X.Y., Gao F., Zeng X., Liu J., Yang Q., Wilhelm S., Yin J., Tao A., Chen Z.F. Exploration of sensory and spinal neurons expressing gastrin-releasing peptide in itch and pain related behaviors. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:1397. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15230-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cui L., Guo J., Cranfill S.L., Gautam M., Bhattarai J., Olson W., Beattie K., Challis R.C., Wu Q., Song X., Raabe T., Gradinaru V., Ma M., Liu Q., Luo W. Glutamate in primary afferents is required for itch transmission. Neuron. 2022;110:809–823.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2021.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen O., He Q., Han Q., Furutani K., Gu Y., Olexa M., Ji R.R. Mechanisms and treatments of neuropathic itch in a mouse model of lymphoma. J. Clin. Invest. 2023;133 doi: 10.1172/JCI160807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pagani M., Albisetti G.W., Sivakumar N., Wildner H., Santello M., Johannssen H.C., Zeilhofer H.U. How gastrin-releasing peptide opens the spinal gate for itch. Neuron. 2019;103:102–117.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen X.J., Sun Y.G. Central circuit mechanisms of itch. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:3052. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16859-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ding Z., Liang X., Wang J., Song Z., Guo Q., Schäfer M.K.E., Huang C. Inhibition of spinal ferroptosis-like cell death alleviates hyperalgesia and spontaneous pain in a mouse model of bone cancer pain. Redox Biol. 2023;62 doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2023.102700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang L., Zhao Y., Gao T., Zhang H., Li J., Wang G., Wang C., Li Y. Artesunate reduces remifentanil-induced hyperalgesia and peroxiredoxin-3 hyperacetylation via modulating spinal metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 in rats. Neuroscience. 2022;487:88–98. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2022.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou F.M., Cheng R.X., Wang S., Huang Y., Gao Y.J., Zhou Y., Liu T.T., Wang X.L., Chen L.H., Liu T. Antioxidants attenuate acute and chronic itch: peripheral and central mechanisms of oxidative stress in pruritus. Neurosci. Bull. 2017;33:423–435. doi: 10.1007/s12264-016-0076-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fang X.X., Wang H., Song H.L., Wang J., Zhang Z.J. Neuroinflammation involved in diabetes-related pain and itch. Front. Pharmacol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.921612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katsyuba E., Romani M., Hofer D., Auwerx J. NAD+ homeostasis in health and disease. Nat. Metab. 2020;2:9–31. doi: 10.1038/s42255-019-0161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu Q.J., Zhang T.N., Chen H.H., Yu X.F., Lv J.L., Liu Y.Y., Liu Y.S., Zheng G., Zhao J.Q., Wei Y.F., Guo J.Y., Liu F.H., Chang Q., Zhang Y.X., Liu C.G., Zhao Y.H. The sirtuin family in health and disease. Signal Transduct. Targeted Ther. 2022;7:402. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-01257-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Callahan S.M., Hancock T.J., Doster R.S., Parker C.B., Wakim M.E., Gaddy J.A., Johnson J.G. A secreted sirtuin from Campylobacter jejuni contributes to neutrophil activation and intestinal inflammation during infection. Sci. Adv. 2023;9 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.ade2693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perico L., Remuzzi G., Benigni A. Sirtuins in kidney health and disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2024;20:313–329. doi: 10.1038/s41581-024-00806-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu X., Su Q., Xie H., Song L., Yang F., Zhang D., Wang B., Lin S., Huang J., Wu M., Liu T. SIRT1 deacetylates WEE1 and sensitizes cancer cells to WEE1 inhibition. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2023;19:585–595. doi: 10.1038/s41589-022-01240-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou C., Wu Y., Ding X., Shi N., Cai Y., Pan Z.Z. SIRT1 decreases emotional pain vulnerability with associated CaMKIIα deacetylation in central Amygdala. J. Neurosci. 2020;40:2332–2342. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1259-19.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang C., Kang F., Huang X., Wu W., Hou G., Zheng K., Han M., Kan B., Zhang Z., Li J. Spinal sirtuin 2 attenuates bone cancer pain by deacetylating FoxO3a. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Basis Dis. 2024;1870 doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2024.167129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou C., Zhang Y., Jiao X., Wang G., Wang R., Wu Y. SIRT3 alleviates neuropathic pain by deacetylating FoxO3a in the spinal dorsal horn of diabetic model rats. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2021;46:49–56. doi: 10.1136/rapm-2020-101918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang J.H., Matei N., Camara R. Emerging mechanisms and novel applications of hydrogen gas therapy. Med. Gas Res. 2018;8:98–102. doi: 10.4103/2045-9912.239959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]