Abstract

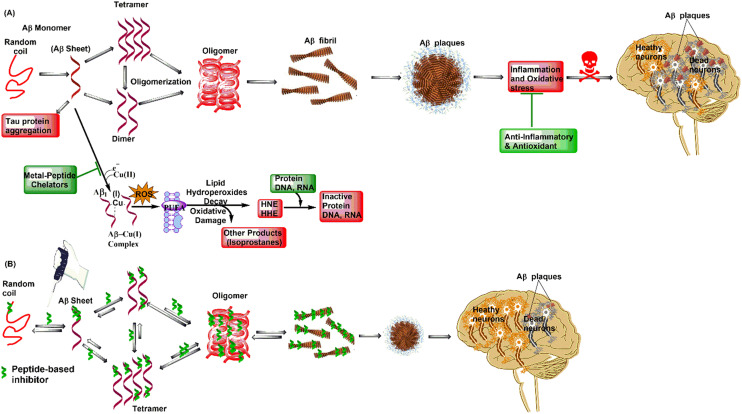

Aberrant protein misfolding and accumulation is considered to be a major pathological pillar of neurodegenerative disorders, including Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases. Aggregation of amyloid-β (Aβ) peptide leads to the formation of toxic amyloid fibrils and is associated with cognitive dysfunction and memory loss in Alzheimer's disease (AD). Designing molecules that inhibit amyloid aggregation seems to be a rational approach to AD drug development. Over the years, researchers have utilized a variety of therapeutic strategies targeting different pathways, extensively studying peptide-based approaches to understand AD pathology and demonstrate their efficacy against Aβ aggregation. This review highlights rationally designed peptide/mimetics, including structure-based peptides, metal-peptide chelators, stapled peptides, and peptide-based nanomaterials as potential amyloid inhibitors.

This review delves into the advancements in peptide-based candidates as potential treatment and management options for Alzheimer's disease.

1. Introduction

Amyloid-β misfolding is still considered a major cause of the development of Alzheimer's disease, which results in cognitive dysfunction and memory loss. Globally, AD or related dementia affects over 50 million people, with a projected increase to 152.8 million by 2050.1 There is no therapeutic treatment that can reduce or reverse AD progression. The approved drugs to date aid in maintaining or enhancing cognitive functioning, including thinking abilities, memory loss, speaking skills, and behavioral challenges, but they serve as symptomatic relief rather than treatment. The USFDA-approved symptomatic treatment includes galantamine, rivastigmine, donepezil, memantine, and combination of donepezil and memantine. Recently FDA-approved disease-modifying medications, aducanumab (marketed as Aduhelm) and lecanemab (marketed as Leqembi), raise hope but have side effects. The lack of sufficient in-field data raises concerns about their safety, primarily due to amyloid-related imaging abnormalities, such as brain swelling and bleeding.1 Due to the complex and still poorly understood biological mechanism, drug development for AD is considered arduous. According to the amyloid cascade hypothesis, one of the main features of AD is the build-up of toxic amyloid-β (Aβ) oligomers. One area of active research in the field of AD drug discovery is the rational design of anti-Aβ agents. Over the years, several therapeutic approaches such as enzyme inhibition, immunotherapy, metal chelation, neuroprotection, and tau protein regulation have been investigated in preventing amyloid and toxic oligomer formation.2,3 High-throughput screening and rational design strategies have identified a number of small molecule Aβ aggregation inhibitors. The limitation with these small molecule inhibitors is that they don't bind to Aβ in a specific way and tend to bind in the later stages of fibrillation, which helps the formation of pre-fibrillar oligomeric forms but doesn't target Aβ oligomers. To overcome this, peptide-based therapeutics have gained attention and are considered as promising candidates for amyloid-β aggregation inhibition. Peptides offer high selectivity due to their ability to establish multiple points of contact with biological targets. Peptides, due to selective interactions, tend to exhibit high specificity and low toxicity. Although peptide-based drugs may not exhibit proteolytic stability, they are gradually overcoming these challenges. Employing strategies such as N- and/or C-terminus protection, use of d- and unnatural amino acids, end group cyclization, and stapling techniques results in peptide candidates possessing drug-like properties for treating several disorders.4 Therefore, developing peptide-based therapeutics is one of the rational approaches in AD drug design and development. The main topic of this review is the rational design of peptide-based analogues, which includes structure-based peptides, metal-peptide chelators, peptide-based nanomaterials, stapled peptides, and peptide/mimetics.

2. Structure-based peptides

Studies on the Aβ aggregation kinetics identified the central hydrophobic core (CHC) and hydrophobic C-terminus of the Aβ peptide as the critical regions that are involved in amyloid oligomer formation. Oligomers play a crucial role in transforming neurotoxic protofibrils into fibrils and nanofilms.5 Structure-based peptides are peptides that are derived from their parent peptide or protein, mimicking their activity and making them more favorable for interaction. These interactions play a significant role in their inhibitory activity profiles. It is known that peptides made up of these self-recognition motifs bind more strongly to the homologous sequence of Aβ and stop it from aggregating. Structure-based peptides exhibit good in vitro activity, but their therapeutic use is questionable due to their tendency to self-aggregate and the risk of incorporation into amyloid fibril. Modifying such peptides can overcome these limitations. Some of these changes are adding bulky groups, charged sequences, or polyethylene glycol to either end, N-methylation, a backbone change, and using α-helix inducers or β-sheet breaker amino acids. Researchers are investigating a wide range of Aβ-binding peptides that block oligomer, fibril, and plaque formation for therapeutic purposes. A list of structure-based peptides from the CHC and C-terminus of Aβ is provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Structure-based peptides as Aβ inhibitors.

| S. No. | Structure-based peptide | Features | Strategic outcome/mechanism of action |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Ac-QKLVFF-NH2 | C- and N-terminus protected CHC-derived fragment | Binds with Aβ and arrests Aβ fibril formation6 |

| 2. | GQKLVFFAEDVGGaKKKKKK | CHC-based fragment attached to disruption unit KKKKKK | Inhibits Aβ1–39 aggregation and exhibits protection against Aβ1–39 aggregation-induced toxicity7 |

| 3. | KLVFF-KKKKKK | CHC-derived sequence linked to disruption unit KKKKKK | Alters Aβ aggregation kinetics and displays complete protection from aggregation-induced neurotoxicity8 |

| 4. | K(N-Me-L)V(N-Me-F)F(N-Me-A)E-NH2 | N-Methylation on a CHC fragment | Inhibits Aβ fibril formation9 |

| 5. | Ac-K(N-Me-L)V(N-Me-F)F-NH2 | N-Methylation on a CHC fragment | Inhibits Aβ fibril formation, disaggregates preformed fibrils10 |

| 6. | KKLV(N-Me-F)FA and KKLVF(N-Me-F)A | N-Methylation on a CHC fragment | Inhibits Aβ42 induced toxicity11 |

| 7. | D-(KLVFFA) | d-Amino acid substitution on a CHC sequence | Exhibits enhanced inhibitory potential on Aβ42 aggregation as compared to l-enantiomer12 |

| 8. | QKLVFFAE | CHC-derived fragment | Controls Aβ42 aggregation at acidic pH13 |

| 9. | RGKLVFFGR (OR1) and RGKLVFFGR-NH2 (OR2) | CHC-derived fragment attached to Arg on C- and N-terminus and Gly as a spacer | Inhibits fibril formation and displays protection against Aβ42-induced neurotoxicity14 |

| 10. | rGffvlkGr-NH2 | Retro-inversion of OR2 | Exhibits complete protection from Aβ42-induced neurotoxicity15 |

| 11. | Ac-rGffvlkGr-NH2 (RI-OR2) | N-Terminus protection on retro-inverso OR2 | Exhibits enhanced inhibitory potential towards Aβ42 aggregation16 |

| 12. | HHQKLV(D-F)(D-F)AED | d-Phe amino acid substitution in CHC-based sequence | Interferes and modulates Aβ42 aggregation, reduces Aβ42-mediated toxicity17 |

| 13. | KLVFFw(Aib) | Disrupting element “wAib” at C-terminus of CHC-based sequence | Inhibits Aβ42 fibrillation and exhibits complete protection of cells against Aβ42-induced-toxicity18 |

| 14. | iAβ1 or RDLPFFPVPID | CHC-derived fragment | Binds with Aβ and inhibits fibril formation, disaggregates pre-formed fibrils19 |

| 15. | iAβ5 (LPFFD), iAβ5p (Ac-LPFFD-NH2) | CHC-derived fragment | Disaggregates preformed fibrils, blocks fibril formation in rat models20 |

| 16. | Ac-LP(N-Me-F)FD-NH2 | C- and N-terminus protected CHC-based sequence | Inhibits fibrillogenesis, exhibits better neuroprotection against Aβ42-mediated toxicity compared to iAβ5p21 |

| 17. | LPYFD-NH2 | C-Terminus protected CHC-based sequence | Exhibits neuroprotective effects against Aβ42-induced toxicity at 5-fold excess22 |

| 18. | Me2Tau-LPFFD-NH2 | C- and N-terminus protected CHC-derived sequence | Exhibits improved inhibition of Aβ fibril formation, enhanced proteolytic stability as compared to iAβ5p23 |

| 19. | Cholyl-LVFFA | C-Terminus protect CHC sequence | Inhibits Aβ aggregation, lacks biochemical stability24 |

| 20. | Ac-K-Sar-VF-Sar-E-NH2 and Ac-K-Sar-VFF-Sar-E-NH2 | C- and N-terminus protected and N-methylated CHC-derived sequence | Inhibits Aβ fibrillogenesis, non-toxic, mimics pharmacophoric features of iAβ5p25 |

| 21. | Pr-IIGL-NH2 | C-Terminal hydrophobic region | Rescues astrocytes from Aβ-induced membrane depolarization, exhibits elevation of intracellular (Ca2+)26 |

| 22. | RIIGL-NH2 | C-Terminal derived sequence | Exhibits protection against Aβ-induced neurotoxicity, completely inhibits fibril formation27 |

| 23. | RVVPI and RIAPA | C-Terminal derived sequence | Exhibits high binding affinity towards Aβ monomer, inhibits Aβ aggregation, prevents conformational change from monomeric structure to aggregates28 |

| 24. | VVIA | C-Terminal sequence | Exhibits high inhibitory potential against Aβ-induced cytotoxicity compared to C-terminal sequence of varied lengths29 |

| 25. | VVIA-NH2, AIVV-NH2, AIVV | C-Terminus protected C-terminal sequence and retro-sequence | Exhibits protection against Aβ-induced neurotoxicity30 |

| 26. | V(Aib)IA | C-Terminal derived sequence | Inhibits Aβ-aggregation and exhibits complete protection against Aβ-aggregation induced toxicity31 |

| 27. | F(4-F)VIA and V(Oic)IA | C-Terminal derived fragment | Inhibits Aβ-aggregation and exhibits complete protection against Aβ-aggregation induced toxicity, proteolytically stable up to 12 h32 |

| 28. | (D-F)VIA-NH2 | C-Terminus based sequence | Exhibits neuroprotective effects against Aβ-aggregation associated toxicity, inhibits Aβ-aggregation completely33 |

| 29. | AI(Aib)V-NH2 | C-Terminus derived retro-sequence | Inhibits amyloid fibril formation, prevents conformational transition to β-sheets, exhibits neuroprotection against Aβ-induced toxicity34 |

| 30. | RVVIA-NH2 | C-Terminus protected C-terminal based fragment | Exhibits significant protection against Aβ42-induced toxicity, inhibits, aggregate formation35 |

| 31. | GFVIA | C-Terminal derived sequence | Exhibits complete protection from Aβ42-aggregation induced neurotoxicity, inhibits Aβ fibril formation36 |

| 32. | Nva-VV | C-Terminal derived ultrashort sequence | Exhibits complete neuroprotection from Aβ42-induced toxicity at 5-fold excess, inhibits Aβ fibril formation37 |

| 33. | Ac-(N-Me-I)-Sar-(N-Me-L)M(N-Me-V)-Sar-NH2 | N-Methylated C-terminal based sequence | Exhibits protective effects against Aβ-induced toxicity and displays increased life span and locomotor activity in Drosophila melanogaster flies38 |

| 34. | IGLMVG-NH2 | C-Terminus protected C-terminal sequence | Displays complete protection from Aβ40-induced toxicity, inhibits Aβ fibril formation39 |

| 35. | GLMVG | C-Terminal fragment | Interacts with C-terminal of Aβ, interferes in Aβ-aggregation40 |

2.1. Structure-based peptides derived from the central hydrophobic core (Aβ12–24)

Tjernberg et al. discussed that the peptide sequence KLVFF is capable of binding to full-length Aβ and preventing its self-accumulation. A peptide, Ac-QKLVFF-NH2, derived from β-amyloid sequence Aβ16–20, that could arrest fibril formation was identified.6 Murphy et al. identified a peptide, GQKLVFFAEDVGGaKKKKKK with disrupting units on both sides and the self-recognition fragment “QKLVFFAEDVG” that stopped Aβ1–39 from aggregating. However, the peptide did not alter the secondary structure of Aβ, indicating that complete fibril formation inhibition is not necessary to halt the toxicity.7 To make the recognition domain as long as possible, Pallitto et al. used a hybrid peptide strategy that included both a self-recognition element and a disrupting fragment.8 The study reported that the hybrid peptide KLVFF-KKKKKK altered Aβ aggregation kinetics as shown by DLS studies, completely protecting against Aβ toxicity compared to recognition motif KLVFF alone.

N-Methylation of amino acids is yet another strategy to generate Aβ inhibitors. Gordon et al. did a study that showed that a peptide with N-methyl amino acids in the alternating positions of the sequence Aβ16–22m, K(N-Me-L)V(N-Me-F)F(N-Me-A)E-NH2, is more effective against Aβ fibrillation than peptides with N-methyl amino acids in a row or peptides that are not methylated.9 In a different study, meptide Ac-K(N-Me-L)V(N-Me-F)F-NH2 or Aβ16–20m, a truncated version of the sequence Aβ16–22m, which effectively inhibited Aβ oligomerization and disaggregated preformed fibrils, was discovered.10 Cruz et al. investigated the effect of replacement of amino acids on peptides derived from the Aβ16–20 motif with N-methyl substituted amino acid residues due to the ability of N-methyl groups to block β structure assembly in peptides. The study revealed two peptides, KKLV(N-Me-F)FA and KKLVF(N-Me-F)A, with N-methyl-Phe at positions 19 and 20 of Aβ16–20 that afforded effective inhibition against Aβ42-induced toxicity in PC-12 cells. In addition, inhibitor peptides were non-toxic, as suggested by control toxicity experiments.11

A study by Chalifour et al. looked at the stereoselective interactions of inhibitors by switching out KLVFFA's l-amino acid residues for its d-isomers. They found that the d-enantiomers were more effective at stopping l-Aβ in an in vitro fibrillogenesis assay. The study confirmed that heterochiral stereoselective inhibition could be done with d-Aβ. l-KLVFFA was more effective than its d-enantiomer.12 Matsunaga et al. tested a group of eight amino acid-derived peptides from Aβ1–42 and found that peptide QKLVFFAE was very good at stopping Aβ from aggregating.13 Austen et al. designed peptide-based inhibitors containing the KLVFF fragment and added cationic Arg residues at both N- and C-terminals, resulting in RGKLVFFGR (OR1) and RGKLVFFGR-NH2 (OR2), wherein the glycine residue acts as a spacer. In the ThT fluorescence assay, both displayed effective inhibitory potential against fibril formation; however, only OR2 exhibited complete inhibition against oligomer formation. Both peptides exhibited complete inhibition against Aβ40-induced aggregation, but only OR2 exhibited complete protection against Aβ42-induced aggregation. Further, in the MTT assay, OR2 showed more than 80% cell survival compared to Aβ40 alone (approximately 40% viable cells) against aged Aβ40-induced toxicity and showed greater than 70% cell survival compared to Aβ40 alone (50% cell viability) against aged Aβ42-induced toxicity. TEM analysis corroborated the inhibitory potential of OR2 against Aβ40 aggregation. The study suggested a new approach for designing peptide inhibitors of Aβ-induced aggregation and toxicity.14 This study was further extended to designing retro-inverso versions of OR2 and reported a peptide rGffvlkGr-NH2 that exhibited complete protection against Aβ40-induced toxicity at a 1 : 2 concentration ratio of Aβ : peptide in human SHSY-5Y neuronal cells.15 Another retro-inverso version of OR2, Ac-rGffvlkGr-NH2 (RI-OR2), was designed where all l-amino acid residues were replaced by their d-counterparts; in addition, all peptide bonds were reversed. ThT fluorescence studies showed that RI-OR2 is a better inhibitor than peptide OR2, but both peptides were very good at keeping cells alive in other studies. Further stability studies showed that RI-OR2 was completely resistant to proteolytic degradation.16

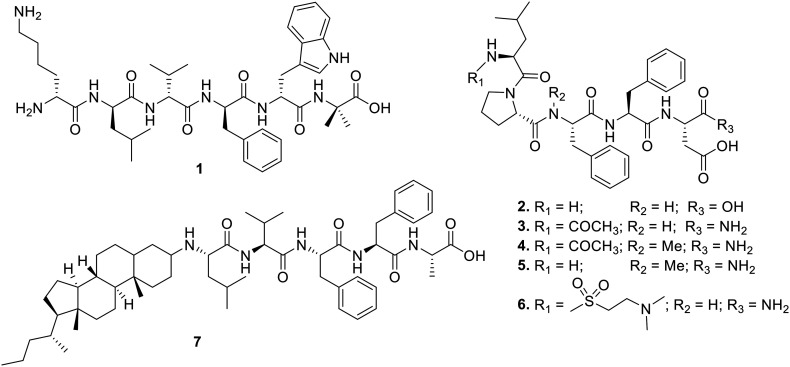

Kumar et al. reported changing the structure of the Aβ14–23 fragment by adding d-Phe residues at position 19 or positions 19 and 20. This caused steric interference with stacking in the aggregate state, which changed how Aβ42 clumped together and made it less harmful. In vitro assays showed that peptides co-incubated with Aβ42 oligomers exhibited a significant reduction in cell toxicity.17 Horsley et al. reported a rationally designed modified KLVFF-based hexapeptide 1 (Fig. 1), which contains d-amino acids to enhance specificity and conjugates with the C-terminal disrupting element “Trp-Aib”. Compared to KLVFF in the ThT fluorescence assay, 1 showed a remarkable ability to stop Aβ42 fibrillation. Complete cell restoration was observed when preformed Aβ42 was added to murine neuroblastoma Neuro-2a cells in the presence of inhibitory peptide 1 at a concentration ratio of 1 : 2 (Aβ42 : 1). The TEM analysis revealed that 1 did not form large fibrillar structures, underscoring its potential for inhibition. The study suggested that adding recognition and disrupting elements to a peptide that contains d-amino acids can work together to have a synergistic effect and a way to deal with Aβ42-induced aggregation and toxicity.18

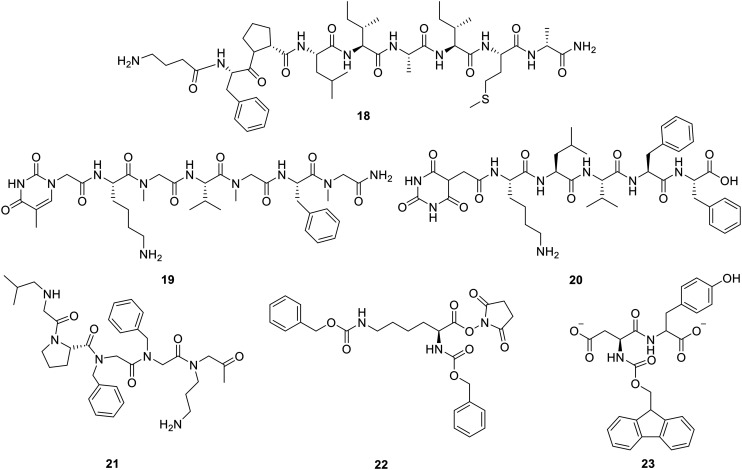

Fig. 1. Central hydrophobic core KLVFF-derived peptides and conjugates.

Based on a modified Aβ15–25 fragment, Soto et al. reported an 11-residue peptide, iAβ1 (RDLPFFPVPID), that displayed high affinity towards Aβ and inhibited Aβ fibril formation significantly. The peptide iAβ1 also showed potency towards disaggregation of preformed fibrils at a concentration of 1 : 20 (Aβ : peptide).19 Another study revealed a β-sheet breaker peptide iAβ5, LPFFD (2, Fig. 1) that disaggregates preformed Aβ fibrils at a concentration ratio of 1 : 3 (Aβ : 2) and completely blocks the formation of Aβ fibrils in rat brain models.20 In addition, iAβ5 and its derivative iAβ5p, Ac-LPFFD-NH2 (3, Fig. 1), have been studied extensively both in vivo and in vitro. Further chemical modification on iAβ5p (3) was reported by Adessi et al. The study demonstrated the rational design of iAβ5p derivatives utilizing N-methylation, N-terminal protection with a variety of groups, replacement with non-natural amino acids, and cyclization using disulfide linkage. Peptide Ac-Leu-Pro-N-Me-Phe-Phe-Asp-NH2 (4, Fig. 1) exhibited significant inhibition in the fibrillogenesis assay but less compared to iAβ5p. However, % cell viability in cellular assays of amyloid cytotoxicity was enhanced compared to iAβ5p. The study suggested that designing β-sheet breaker peptides could be a constructive solution.21 Datki et al. discovered a new peptide, LPYFD-NH2 (5, Fig. 1), that protects neurons from damage caused by Aβ. The MTT test on SH-SY5Y cells showed that peptide 5 stopped Aβ from killing the cells at a concentration of 1 : 5 (Aβ : 5). In a cell-free environment, no Congo red (CR) binding to Aβ in the presence of the inhibitory peptide was observed.22 In 2009, Giordano et al. designed analogues based on Soto's pentapeptide, iAβ5p. The study reported a peptide, Me2Tau-LPFFD-NH2 (6, Fig. 1), by substituting Leu with Me2Tau at the N-terminal that exhibits significantly higher % inhibition compared to iAβ5p. Peptide 6 also exhibited enhanced stability on juxtaposing with iAβ5p. SEM analysis showed the absence of fibrillar structures in the presence of inhibitor 6.23 Findeis et al. made a library of modified peptide inhibitors and looked into structural needs by making the Aβ peptide central domain smaller. Modifying amino terminus with a variety of chemical reagents enhanced the activity of the peptides, and the cholyl-modified analogue, cholyl-LVFFA (7, Fig. 1), showed remarkable inhibition but lacked biochemical stability.24 Recently, Moraca et al. showed that screening N-methylated peptides derived from iAβ5p revealed two peptides, Ac-K-Sar-VF-Sar-E-NH2 and Ac-K-Sar-VFF-Sar-E-NH2 (Sar = N-Me-Gly), that effectively stopped the formation of Aβ fibrils and were safe to use. In addition, the study indicated that the newly designed peptides mimicked the pharmacophoric features of iAβ5p.25

2.2. Structure-based peptides derived from the C-terminal hydrophobic region (Aβ29–42)

With the development of structure-based peptides as Aβ inhibitors, the focus shifted from Aβ's central hydrophobic core to its more hydrophobic and harmful ends. A substantial body of evidence has suggested the role of the C-terminal region in Aβ aggregation. In recent years, researchers have designed Aβ inhibitors utilizing C-terminal fragments; however, the region still remains relatively less explored.

A tetrapeptide antagonist, propionyl-IIGL-NH2 (Pr-IIGL-NH2), which comes from the sequence Aβ31–34, protected astrocytes from Aβ-induced membrane depolarization and raised intracellular Ca2+ levels for a long time in vitro, but it killed neuroblastoma cells.26 Later, Fülöp et al. designed RIIGL-NH2 based on this sequence that exhibited 84% cell survival, whereas Pr-IIGL-NH2 exhibited 40% cell viability (the same as that of Aβ42). TEM results showed that no Aβ fibrils were formed in the presence of RIIGL-NH2.27 Kaur et al. screened a library of peptides derived from RIIGL and reported two new pentapeptides, RVVPI and RIAPA, that exhibited high binding affinity towards the Aβ42 monomer, prevented conformation transition from the monomeric structure to aggregates, and reduced Aβ42-aggregation.28

Fradinger et al. and Li et al. synthesized peptides from the C-terminus based on the idea that its strong affinity for Aβ might also stop the formation of oligomers. Structural modification includes Ala-scan, retro-peptide, retro-inversion, C-terminal amidation, and N-terminal protection. The study found that short peptides based on the C-terminus “VVIA” were strong inhibitors that completely restored synaptic activity at micromolar concentration.29,30 In a different study, Bansal et al. made a library of peptides based on the sequence VVIA and reported a peptide V(Aib)IA that kept cells alive even when there was a 10-fold concentration of Aβ.31 The study was extended further by carrying out an amino acid scan of VVIA utilizing unnatural amino acids that resulted in two new peptides 8 and 9 (Fig. 2) exhibiting promising protection against Aβ42-induced cytotoxicity in PC12 cell lines at a dose concentration ranging from 10 to 0.1 μM. The serum stability studies revealed that the peptides were intact up to 12 h, followed by 25–30% degradation at 18 h and 75% degradation at 24 h.32 A sequential amino acid scan of VVIA-NH2 and its retro-analogue AIVV-NH2 was carried out that led to (d-F)VIA-NH2 and AI(Aib)V-NH2 with protection against Aβ42-induced neurotoxicity and complete inhibition against Aβ42 aggregation in the ThT fluorescence assay, and 90% of cell viability.33,34 Due to the presence of the α-helix inducer “Aib”, the designed peptide effectively stopped the conformational change to β-sheets and increased the α-helical content.

Fig. 2. Structure-based peptides derived from C-terminal region fragment VVIA of Aβ.

Hetényi et al. and Bansal et al. reported pentapeptides RVVIA-NH2 and GFVIA, respectively, based on Aβ38–42. The FTIR studies showed that RVVIA-NH2 reduced the aggregates.35,36 Peptide GFVIA protected cells from Aβ-induced toxicity in the presence of ten times concentration of Aβ and completely stopped Aβ aggregation in the ThT fluorescence assay as further confirmed by CD and TEM analyses. The amino acid scan of two very short peptide sequences, GVV and VIA, from the C-terminal region was reported by Sehra et al. The research found a tripeptide called Nva-VV that protected cells from Aβ-induced damage at a concentration of 10 μM and stopped Aβ-induced aggregation by 81.2%, as shown by the ThT fluorescence assay. Further, mechanistic investigation was carried out using CD, TEM, HRMS, and DLS studies that confirmed the inhibitory efficacy of Nva-VV.37 A study reported the effect of N-methylation of Aβ32–37 derived sequence Ac-IGLMVG-NH2 and showed that a penta-N-methylated peptide, Ac-(N-Me-I)-Sar-(N-Me-L)M(N-Me-V)-Sar-NH2, was efficient. The peptide exhibited increased life span and locomotor activity in Aβ42-expressed Drosophila melanogaster flies.38 A recent library screening showed that peptide Aβ32–37-NH2 (IGLMVG-NH2) completely protected PC12 cells from the damage caused by Aβ. CD studies revealed that mixing peptide with Aβ42 greatly decreased the number of β-sheets present. In TEM analysis, the presence of an inhibitor did not result in the formation of a mature amyloid fibrillar structure.39 Peters et al. found that the pentapeptide Aβ33–37 (GLMVG) interfered with the aggregation, joining, and opening of the plasma membrane for Aβ. The research findings indicated that the peptide displayed a reduction in synaptotoxicity induced by Aβ.40

Structure-based peptide research to find Aβ inhibitors has mostly focused on the central hydrophobic region (Aβ12–24) and the C-terminus hydrophobic region (Aβ29–42). To sum up, different peptide-based drug discovery methods have been used to find promising inhibitors, such as some very short sequences that might be able to stop Aβ from aggregating.

3. Metal-peptide chelators

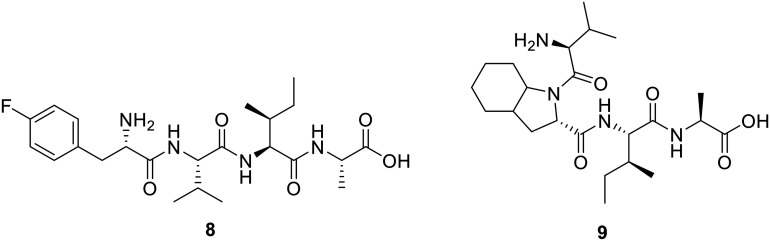

The Aβ peptide and its aggregates are very important in increasing oxidative stress and inflammatory responses in and around brain cells and microglia in the cerebral cortex. It is known that the first 16 residues of the N-terminus of the Aβ peptide have a strong ability to bind metals. These residues include Asp1/7, Glu3/11, and dynamic His6/13/14. This region demonstrates a higher affinity for coordinating with metal ions such as Cu, Zn, Fe, and Al, especially Cu2+ and Zn2+ ions that associate with the Aβ peptide to form an Aβ/metal ion [Aβ/M2+ and/or Aβ/M+] complex, leading to increased oxidative stress via Fenton-type reaction and harmful ROS formation inside the cytosol and mitochondria.41–43 Increased oxidative stress is responsible for the oxidation of lipoidal membrane polyunsaturated fatty acid chains (PUFAs) and cholesterol. This non-enzymatic lipid peroxidation occurs via reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation (Fig. 3), contributing to the formation of toxic substances 7-β-hydroxycholesterol, 4-hydroxy-trans-2-nonenal (HNE), and malondialdehyde (MDA), resulting in oxidative stress and cellular damage in AD brain.43 Additionally, the Aβ oligomeric [Aβ/Cu2+] complex radically oxidizes cholesterol to form highly neurotoxic intermediates, which are highly reactive and generate nonfunctional DNA and proteins by forming Schiff bases/Michael adducts upon reacting with the His, Lys, Arg, and Cys amino acids of active enzymes and proteins and promoting apoptosis. Protein aldehydes also act as neoepitopes and trigger immune responses contributing to chemotactic reactions and neuroinflammation.44–47 Trace metals (Cu, Zn, and Fe) are important drivers of biochemical transformation and homeostasis because they participate in various enzymes as cofactors. However, metal dyshomeostasis contributes to the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Metals Cu+/Cu2+ and Zn2+ promote Aβ-peptide aggregate-mediated ROS production. Significant attention has been paid to metal ion chelators (Cu2+, Zn2+, and Al3+), especially metal-peptide chelators (MPCs) that prevent Aβ aggregation and aggregate-mediated ROS formation in the AD brain. MPCs are the peptides that form complexes with various metals to suppress the toxicity of free metals, enhance cellular uptake, and increase bioactivity. In the case of AD, MPCs, designed to bind and extract metal ions from aggregates, are ultrashort to small peptides with an excellent ability to penetrate the blood–brain barrier (BBB). Due to their higher caliber, they have a stronger ability to bind free metal ions than amyloid peptides and toxic aggregates, resulting in a higher propensity to form enduring metallopeptide complexes by interlocking metal through peptide-assisted complexation. The amino-terminal Cu(ii)- and Ni(ii)-binding (ATCUN) motifs and the His-rich and His–Gly-rich metal-peptide ionophoric chelators bind similarly to Aβ with stronger affinity, which shows promise in stopping or reversing the harmful effects of Aβ aggregation and mediated toxicity. Researchers have published new research on the structure and framework of MPCs. For example, His residues are important for lipid peroxidation. Aβ aggregates and fibrils are much less harmful in both cell and animal models when His residues are added to the sequence of inhibitory peptides.48,49

Fig. 3. The relationship between amyloidogenesis and the oxidative lipoidal membrane damage-mediated formation of HNE and MDA was schematically inferred. They contribute to apoptosis by inactivating proteins through the formation of Schiff bases. The amyloid precursor protein (APP) is proteolytically truncated by β- and γ-secretase proteases to produce Aβ (39 to 43). In parallel, under the influence of unaggregated soluble amyloid-β (Aβs), Cu2+ is reduced to Cu+, and Cu+ has a strong affinity for the ATCUN-type motif (His6/13/14) present in the Aβ peptides, creating the [Aβ/Cu+] redox complex. This event sets off oxidative stress (Fenton-type reaction), non-enzymatic lipo-hydroperoxidation by increased ROS production, especially ·OH. This process oxidizes lipid bilayers, including PUFAs, cholesterol, and other fatty acids, resulting in the production of harmful, highly reactive HNE, MDA, and other isoprostane by-products. HNE joined with Aβ and makes an HNE/Aβ-modified adduct. This adduct then helped fibrillogenesis by changing Aβ into nanofibrillary structures and, finally, mature Aβ-fibrils (AβFs). On the other hand, HNE and MDA react with the amino acid side chains of DNA, proteins, and enzymes. This creates Schiff base/Michael adducts, which are even more harmful to cells. In short, high levels of amyloid-β cause plasma membrane lysis and apoptosis by throwing off the balance of cellular homeostasis.44,46.

3.1. ATCUN motifs and His-rich metal-peptide chelators for metal-induced amyloidogenesis

Metal ion-binding peptide motifs have a significantly higher binding affinity for Cu, Ni, Zn, Fe, and other metal ions.43 Numerous amino terminal Cu(ii)- and Ni(ii)-binding (ATCUN) motifs inspire the MPC peptide ionophores. The ultrashort and short peptides showed excellent affinity for Cu and Zn ions. Table 2 describes the metal ionophoric peptide inhibitors. These MPCs work with metal ions to stop ROS formation and toxicity caused by metals. They also stop the formation of [Aβ/M+] complexes by taking the metal out of them. Zimmeter et al. conducted an investigation into the Cu2+ ion chelation properties of the ATCUN-like motif, an ultrashort GH dipeptide. They anchored 2-picolinic acid (Pa) and 2-picoline (Pc) to the N-terminus of the GH peptide to prepare Pa-GH and Pc-GH peptides, respectively. Peptides exhibited remarkably high affinity and chelator potency for Cu2+ and were more than 1000 times more selective towards Cu2+ than Zn2+ ions. Additionally, peptides showed EDTA-like binding affinity towards Cu2+ and had a redox-silencing feature that suppressed ROS production.50 Hu et al. described the role of the GGH tripeptide in overcoming the burden of Cu2+ free ions. This tripeptide selectively destabilizes [Aβ/Cu2+] by taking Cu2+ from the [Aβ/Cu2+] complex instead of other free ions like K+, Zn2+, Mg2+, Ni2+, and Ca2+. In addition, a four-fold excess of GGH to that of Cu2+ or [Aβ/Cu2+] results in a decrease in ROS generation as well as a complete loss of catalytic activity of Cu2+ towards Cu2+-induced Aβ aggregation.51 Gonzalez et al. described an ATCUN motif-inspired peptide ligand AHH that was able to remove Cu2+ from [Aβ/Cu2+]. The study suggested that the presence of Zn2+ speeds up the removal of Cu2+ from Aβ and that the His-rich tripeptide stopped the production of ROS caused by Cu2+.52 Caballero et al. reported His-rich ATCUN motif inspired tripeptides, HAH, HWH, and HKCH (C = Ne-coumarin-tagged) as metal-peptide chelators that exhibited protection of Cu2+-mediated Aβ toxicity. The research showed that the ATCUN motif in the metal-peptide chelators had strong redox-silencing activity, which stopped the production of ROS and oxidative stress.53 The same research group published another study that found five Gly–His-rich head-to-tail cyclotides that were competitive binding inhibitors of Cu2+ ions. These ions stopped [Aβ40/Cu2+] adduct-mediated aggregation. The C-Asp, cyclo[GDWHPGHKHP], a cyclic decapeptide, exhibited significant affinity for Cu2+ ions and binds with the [Aβ/Cu2+] adduct, thereby inhibiting ROS production and release.54 Later, Guilloreau et al. synthesized ultrashort ATCUN motif-based GHK and DAHK peptides and tested how well they bound Cu2+ and turned off redox signals. It was found that GHK and DAHK were very good at removing Cu2+ from the [Aβ42/Cu2+] complex and stopping the formation of OH radicals and other ROS.55

Table 2. Metal-peptide chelator (MPC) driven approach for targeting Aβ aggregation.

| S. No. | Inhibitory MPC sequence | Features | Screening | Strategic outcome/mechanism of action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Pa-GH and Pc-GH,50 Pa = 2-picolinic acid, Pc = 2-picoline | ATCUN motif-derived peptides | In vitro | Selective Cu2+ chelator, and prevent ROS production50 |

| 2. | GGH tripeptie | In vitro | Selective scavenger of Cu2+ from [Aβ/Cu2+] complex over other ions (Zn2+, Mg2+, Ni2+, and Ca2+), catalytic loss of Cu2+ and [Aβ/Cu2+]-mediated aggregation and ROS formation51 | |

| 3. | GHH, AH and AHH | In vitro | Cu2+ ion scavengers, redox silence, and ROS formation properties52 | |

| 4. | HAH, HWH, and HKCH | In vitro | Excellent Cu2+ chelator peptides, formed albumin-like complexes, inhibited Aβ-aggregation and ROS production, and good BBB agent53 | |

| 5. | Cyclo[GDWHPGHKHP] (C-Asp) | In vitro | Competitive binding inhibitor of Cu2+ ions, binds with [Aβ/Cu2+] adduct, inhibits ROS production54 | |

| 6. | GHK and DAHK | In vitro | High affinity for Cu2+ and sequestering Cu2+ from [Aβ/Cu2+] and prevents ·OH and other ROS formation55 | |

| 7. | HWHG and HGHW | In vitro | Extracted Cu2+ from the [Aβ/Cu2+] adduct, blocked Cu2+ and [Aβ/Cu2+] complex driven ROS production56 | |

| 8. | GHKHG ([GH]2K) and HHKHH ([HH]2K) | In vitro | High affinity Cu2+ and Zn2+ ion macrochelator at physiological pH, effectively inhibits Cu2+ while efficient in Zn2+ induced Aβ aggregation57 | |

| 9. | DAHFWADR-NH2 (CP) | In vitro | Potent-chelators to Cu2+ and Zn2+, extracts metal from [Aβ-M] complex and quenches metal/[Aβ–M] complex, induced ROS formation58 | |

| 10. | MEHFPGP (Semax) | In vitro | Suppressed amyloidosis and fibrillogenesis attenuated [Aβ/Cu2+] complex formation and associated toxicity, and neuroprotective59 | |

| 11. | GHL-Sar-V-Sar-F-Sar (P6) | Chimeric ATCUN motif with Sar-V-Sar-F-Sar | In vitro | Inhibitor of Aβ aggregation, prevented Cu2+ and [Aβ/Cu2+] complex induced toxicity and DNA cleavage, protects membrane (liposomes) from ROS60 |

| 12. | FRHDSGYEVHHQK-NH2 (Aβ4–16) | (ATCUN)-type Aβ peptide Aβ4–16 | In vitro | Excellent-chelating synaptic Cu2+ scavenger for Cu2+ and ROS formation61 |

| 13. | NTA(HisNH2)3 (pseudopeptide L) | His-rich pseudopeptide | In vitro | Bind with Cu+ and Cu2+ and extract Cu ions and prevented [Aβ/Cu2+] formation and aggregation, redox silence, and ROS formation62 |

| 14. | LPFFDGNSM | iAβ5p | In silico | Multifunctional inhibitory metal peptide chelator for Zn2+ and Cd2+ ion63 |

| 15. | Cyclo-[KLVfFAE] (f = d-Phe = 19fCP), and a Lys(K) tagged (PA-19fCP and PA-19fCP-FI) peptides | Cyclic peptide [KLVFFAE] of Aβ | In vitro | Multitarget metal (Cu2+, Zn2+, and Fe2+) chelators and anti-Aβ aggregators, fibrillogenesis inhibitors, inhibits [Aβ/M] ion-induced aggregation, and theranostic agent64 |

| Fluorescent tagged PA19fCP-F1 | ||||

| 16. | Ac-LVFFARKHH-NH2 (LK7-HH) | His-rich-LK7-HH chimeric nonapeptide | In vitro | Inhibits Aβ, chelates Cu2+ ion, prevents [Aβ/Cu2+] cytotoxicity, and ROS formation65 |

| 17. | Carnosine-LVFFARK-NH2 conjugate (Car-LK7) | Carnosine-LK7 peptide conjugate | In vitro | Moderate Cu2+ chelator, potent inhibitor of [Aβ/Cu2+]-associated aggregation and ROS formation. Car-LK7 is twice potent compared to LK7, neuroprotective, biocompatible and poses the least self-cytotoxicity66 |

| 18. | RTHLVFFARK-NH2 (RK10) | Chimeric of ATCUN and motif LK7 | In vitro | Bifunctional chelator of free Cu2+ ion or [Aβ/Cu2+] adducts and arrested ROS formation. Rescued SH-SY5Y cells by eliminating Aβ aggregation induced cytotoxicity67 |

| 19. | Ac-LVFFARK-NH2-peptide-β-cyclodextrin conjugate (LK7-βCyD) | Cyclodextrin-LK7 peptide conjugate | In vitro | LK7-βCyD has superior potency to LK-7, improved lipophilic, anti-Aβ fibrillogenesis activity and reduces Aβ aggregate induced toxicity on SH-SY5Y cells68 |

| 20. | rthlvffark-NH2 (rk10) | Chimeric of ATCUN and motif LK7 d-enantiomeric | In vitro | High binding affinity for Cu2+ and [Aβ/Cu2+] adduct, mitigates [Aβ/Cu2+] associated aggregation and ROS formation, and disruptor of Aβ-protofibril69 |

| 21. | Glucose-DAHK-LPFFD glycopeptide (Glupep) | Chimeric human serum albumin ATCUN motif-LPFFD-glycopeptide | In vitro | Multifunctional glycopeptide, restricts LPFFD self-aggregation, a strong sequester of Cu and extracted Cu from [Aβ/Cu2+] species, prevents Aβ oligomers and fibrillogenesis, decreased ROS, and good BBB permeability70 |

| In vivo | ||||

| 22. | Ac-EVMEDHA-KLVFF-NH2 (τ9–16-KLVFF) and Ac-QGGYTMHQKLVFF-NH2 (τ26–33-KLVFF) | Chimera tau/Aβ | In vitro | Cu2+ and Zn2+ chelator, higher affinity to Aβ and prevent aggregation and fibrillogenesis, and artificial neuronal membrane protective71,72 |

| τ9–16/Aβ16–20 | ||||

| τ26–33/Aβ16–20 peptides | ||||

| 23. | Human lysozyme-RTHLVFFARK conjugate (RhLys-R) | Human lysozyme-RTHLVFFARK (RK10) conjugate | In vitro | Conjugate is more potent than RK10, a specific Cu2+ scavenger, arrested ROS production, anti-Aβ-aggregates, and perturbed Aβ-fibrils73 |

| 24. | GGH-RYYAAFFARR (GR) | ATCUN motif- AFFAR | In vitro | β-sheet breaker, suppressed [Aβ/Cu2+]-induced cytotoxicity by broke up Aβ-Cu fibrils into small pieces, stopped the production of ROS, AD rat model, GR peptide advanced cognitive functioning with preventing further memory loss74,75 |

| In vitro | ||||

| 25. | Ac-G(bistriazolylmethyl)-LV-OMe (DS2) | Triazole-peptide conjugates | In vitro | Inhibits Aβ aggregation, deformed preassembled fibrils, Cu2+ ion chelator, inhibits Cu2+ and [Aβ/Cu2+] associated aggregation, lowers the oxidative stress and ROS formation76 |

| 26. | HMQTNHH (PZn) | His rich phage cloned peptide | In vitro | Excellent Zn2+ chelator, sequestered Zn ions from [Aβ/Zn2+] complex and inhibited Aβ-aggregation, and ROS releases, increased stability and bioavailability, NPs enhanced the cognitive and learning potential of mice, and abbreviated-Aβ peptide accumulation was observed in histologic analysis77 |

| PZn-nanoparticles (PEG/CS-PZn NPs) | In vivo | |||

| 27. | SAQIAPH (PCu) | Phage cloned peptide | In vitro | Strong Cu2+ chelator and prevents Cu2+ induced amyloidosis, oxidative stress and ROS formation, good BBB in transgenic mice, good BBB, and prevents Aβ aggregation78 |

| In vivo |

Lefèvre et al. reported an important structural feature of Gly–His-rich ATCUN peptides, demonstrating an excellent chelating property of Cu2+ ions. Two peptides, HWHG and HGHW, sequestered Cu2+ from the [Aβ/Cu2+] complex and blocked Cu2+ and [Aβ/Cu2+] complex-induced ROS production.56 In another study, Lakatos et al. reported two His-rich MCPs, namely GHKHG ([GH]2K) and HHKHH ([HH]2K), that also contain a lysine. The designed MPCs had a very strong attraction to Cu2+ and Zn2+, forming complexes that stayed stable at physiological pH. Findings from the study showed that branching in peptides with metal-binding sites could be used as a metal chelator because it stops [Aβ/M2+] associated aggregation and ROS formation.57 Folk et al. utilized a modified version of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) Swedish mutant sequence to design a chelator peptide, Ac-EVNLDAHFWADR-NH2, which on enzymatic (BACE) cleavage releases a chelator peptide, CP (H2N-DAHFWADR-NH2), possessing the ATCUN motif. According to fluorescence titration studies, CP had a strong attraction to Cu2+ and quickly removed Cu2+ from Aβ. This stopped or reversed the formation of Aβ aggregates and protected against Cu2+-induced ROS formation. However, the prochelator peptide failed to remove Cu2+ from Aβ. The study also suggested that because the enzyme (BACE) specifically activates the prochelator to release CP, this chelating strategy is only effective when BACE activity is elevated.58

Recently, Sciacca et al. investigated the ionophoric effect of the heptapeptide Semax (MEHFPGP), composed of the ATCUN motif, mimicking an endogenous nootropic regulatory peptide ACTH (MEHFRWG), on Cu2+ ions and [Aβ40/Cu2+] complex-induced oligomerization. The research findings suggested that Semax sequestered Cu2+ ions, inhibited [Aβ40–Cu2+] complex formation, and interacted with [Aβ40–Cu2+] oligomeric species, thereby decelerating fibrillogenesis.59 Rajasekhar et al. designed and synthesized a multifunctional chimeric GHL-Sar-V-Sar-F-Sar (P6) peptide composed of Gly–His rich GHL, an ATCUN motif, and an Aβ inhibitory Sar-V-Sar-F-Sar peptide. P6 interfered in Aβ oligomerization processes, inhibited aggregation, and rescued PC12 cells. The GHL motif in P6 effectively trapped Cu2+ while stopping the formation of [Aβ/Cu2+] complexes and the harmful effects that come from them. Additionally, P6 showed synergistic effects by blocking Cu2+ ions and [Aβ/Cu2+]-mediated ROS (·OH) formation. This protected the liposomal membrane from the OH radicals, stopping membrane disruption and leakage, protecting DNA damage, and oxidative cleavage.60 Wezynfeld et al. found that an ATCUN-like peptide fragment called FRHDSGYEVHHQK-NH2 (Aβ4–16) had a higher affinity for Cu2+ ions and great chelating effects, which stopped the [Aβ/Cu2+]-complex from accumulating by scavenging Cu2+ ions. Under physiological conditions, the peptide's N-terminus binds to Cu2+ to form a complex that exhibits redox silencing and controls ROS formation.61 Conte-Daban et al. discovered that His-rich pseudopeptide L is a potent Cu+ and Cu2+ peptide chelator. Pseudopeptide L, which is made up of three His residues anchored with nitrilotriacetic acid, had a strong ability to bind to Cu+ and Cu2+. The π-nitrogen of His side chain imidazole coordinated with Cu+ and acquired tetrahedral geometry, whereas Cu2+ attained square-planar geometry. The study showed that the peptide targeted both redox states Cu+ and Cu2+, owing to the peptide's unique Cu coordination properties. It prevented [Aβ/Cu2+] complex formation, thereby inhibiting aggregation and inhibiting ROS formation. The designed pseudopeptide L can be considered a potential candidate for Zn2+-mediated Aβ toxicity.62

3.2. Chimeric metal-peptide chelators as amyloidosis inhibitors

The ATCUN motifs exhibit excellent affinity towards metal ions and selectively quench free metal ions, especially Cu/Zn ions by extracting them from [Aβ/M] ion complexes which prevents oxidative stress-mediated ROS formation. However, their vulnerability towards proteolytic stability prompted researchers to exploit chimeric and peptide-conjugate approaches.63–66 Chimeric metal-peptide chelators are made up of different kinds of peptides that have distinct chemical and drug-binding properties. They are modified and improved forms of multifunctional peptides, containing at least one metal-sequestering peptide, and other counterpart partners must be peptides or heteroelements. They are known for their anti-aggregative effects, which can significantly increase their ability to advance amyloidolysis by eliminating Aβ aggregation and fibrillogenesis, stopping [Aβ–Cu2+] adduct association, arresting ROS formation, protecting neuronal members from ROS, and disrupting Aβ-aggregates and protofibrils, along with enhanced potency, neuroprotective properties, biocompatibility, and BBB permeability.

In recent years, rationally designed chimeric peptides have emerged as promising tools towards inhibiting amyloidogenesis and in preventing ROS production via metal chelation. The CHC-inspired peptides, such as KLVFF sequence-originated peptides, effectively curtailed the self-reorganization of Aβ and exhibited excellent anti-amyloidogenic effects. Zhang et al. designed a nonapeptide utilizing an Aβ inhibitor Ac-LVFFARK-NH2 (LK7) to which two His residues were linked at its C-terminus. The newly designed peptide, LK7-HH, displayed improved inhibitory potential towards Aβ aggregation, and in addition, showed promising Cu2+ chelating potential. It prevented ROS generation by extracting Cu2+ from the Cu2+/Aβ complex and inhibited copper-induced Aβ aggregation.65 Zhang et al. crafted a bifunctional peptide, Car-LVFFARK-NH2 (Car-LK7), by linking a native chelator carnosine to LK7. The study indicated that Car-LK7 exhibited remarkable inhibitory potential towards Aβ aggregation but showed inadequate chelating affinity in extracting Cu2+ from the [Aβ40/Cu2+] complex. It formed the ternary [Aβ40/Cu2+]-Car-LK7 complex that destabilized the β-sheets, while promoting the aggregation into small, unstructured amorphous aggregates. Car-LK7 displayed higher activity in muting [Aβ40/Cu2+]-induced ROS generation compared to Car or LK7 alone. At equimolar concentration, Car-LK7 significantly reduced the toxic effect of Aβ40 and rescued SH-SY5Y cells by exhibiting 99% cell viability.66 Meng et al. designed a novel bifunctional peptide by uniting a tripeptide, RTH, possessing metal chelating properties and previously discussed LK7 to produce a decapeptide RTHLVFFARK-NH2 (RK10). The peptide RK10 displayed high selectivity towards Cu2+ over other metal ions. Additionally, RK10 sequestered Cu2+, prevented ROS production, and inhibited Cu2+-mediated Aβ aggregation and induced toxicity.67 In another study, Zhang et al. constructed the LK7-β-cyclodextrin conjugate (LK7-βCyD) that displayed superior potency towards Aβ aggregation compared with LK-7, owing to reorganization of hydrophobic residues of the LK7 peptide and making them more accessible for interaction with Aβ40. Ten-fold excess of the conjugate resulted in complete protection against Aβ aggregation-induced toxicity compared to LK7 alone.68

Liu et al. investigated the chirality effect of the d-enantiomer of RK10 on Cu2+ chelation, ROS production, Cu2+-induced Aβ aggregation, and aggregation-induced toxicity. When compared to its l-enantiomer, the d-enantiomer of the decapeptide RK10 showed a significant rise in cell viability and a remarkable drop in ROS levels caused by [Aβ/Cu2+] or Cu2+. In comparison to RK10, the d-enantiomer displayed noteworthy inhibition of Cu2+-induced Aβ aggregation and significantly reduced the [Aβ/Cu2+]-complex-induced toxicity. Additionally, RK10 showed that it could stop disaggregated species from reassembling and changed the shape of mature Cu2+–Aβ aggregates by chelating Cu2+.69 Afterwards, Roy et al. synthesized Glu-LPFFDDAHK (Glupep) by conjugating a glucose unit to a hybrid peptide consisting of a β-sheet breaker (LPFFD) and HSA-inspired tetrapeptide (DAHK) through thio-coupling. By stopping Aβ from self-assembly, Glupep limited the formation of oligomers and fibrils. It also kept Cu2+ from [Aβ42/Cu2+] species and lowered ROS production. The study also suggested that the presence of a glucose moiety enhanced BBB permeability and bioavailability.70

Sciacca et al. designed two chimera peptides from tau protein fragments, τ9–16 and τ26–33, coupled with a hydrophobic Aβ16–20 sequence to produce tau-Aβ chimeric congeners, Ac-EVMEDHAKLVFF-NH2 (τ9–16-KL) and Ac-QGGYTMHQKLVFF-NH2 (τ26–33-KL). Because they had the recognition motif KLVFF, both chimeric peptides had very high affinity and stopped aggregation/fibrillogenesis. MALDI-TOF experiments showed that these chimera peptides were not good at extracting M2+ but did form ternary complexes [Aβ42/M2+/chimera]. Overall, the results showed that peptide τ9–16-KL had a strong ability to stop the formation of amyloid fibrils and could be used as a useful scaffold. On the other hand, τ26–33-KL didn't show much inhibition because the sequence is hydrophobic, which causes the peptide to fold and form a turn-like structure that stops its Aβ binding motif.71,72 Shamloo et al. designed a multifunctional peptide LPFFDGNSM composed of iAβ5p (LPFFD) and a potent Zn chelator NSM peptide conjugated using Gly as a spacer. The researchers used an integrated approach that combined docking, molecular dynamics, and quantum mechanics simulations to study the receptor–ligand interactions between the newly designed peptide and Zn2+/Cd2+. Based on in silico analysis, the peptide showed stronger ion chelation affinity with both Zn2+ and Cd2+ and significantly inhibited Aβ aggregation.63

Li et al. developed a multifunctional modulator by conjugating metal chelator peptide (RK10) with a natural protein inhibitor of Aβ (human lysozyme, hLys) via Cys to produce RK10-Cys-hLys (R-hLys). The research showed that R-hLys was better at protecting cells from Aβ aggregation and cytotoxicity. It also stopped the production of ROS by Cu2+/[Aβ/Cu2+] and changed mature Aβ42 or Aβ42–Cu2+ aggregates into a small, amorphous form that was not structured.73 In another study, Zhang et al. constructed a bifunctional inhibitory peptide, GGH-RYYAAFFARR (GR), by attaching a sequence GGH to β-sheet breaker, RYYAAFFARR (RR). GR exhibited significant reduction in the [Aβ/Cu2+]-induced cytotoxicity. According to this study, GGH worked as a metal-specific chelating sequence, while RR was in charge of the designed peptide's Aβ-inhibitory effect.74 Wang et al. expanded on the study and showed that peptide GR broke up Aβ–Cu fibrils into small pieces, stopped the production of ROS, and effectively protected the PC12 cells against [Aβ/Cu2+]-induced cytotoxicity. Also, GR significantly reduced Aβ deposits in the AD rat model, resulting in improved cognitive functioning and preventing memory decline. The histopathological analysis illustrated that the peptide reversed hippocampal neuronal shrinkage and Aβ plaque proliferation.75

Mann et al. synthesized a series of triazole-peptide conjugates as potential modulators targeting various AD pathways. A multifunctional peptidomimetic DS2, Ac-G(ditriazolylmethyl)-LV-OMe, showed protection against Aβ42 aggregation and disaggregated preformed Aβ42 fibrils. Furthermore, DS2 moderately bonded with Cu2+ ions and stopped [Aβ42–Cu2+]-induced aggregation. DS2 exhibited neuroprotection against Aβ-induced toxicity and inhibited ROS formation. Also, an increase in helical content was observed in the presence of DS2, as indicated by secondary structural analysis.76 Zhang et al. described the neuroprotective effect of phage-cloned His-rich heptapeptide, HMQTNHH (PZn), against Zn2+ ions and [Aβ/Zn2+]-associated amylogenesis. PZn showed excellent affinity and specificity towards Zn2+ which suppressed Zn2+ load and [Aβ/Zn2+]-associated aggregation. The zinc-chelating peptide PZn was loaded onto PEG-chitosan to develop PEG/PZn-CS nanoparticles (NPs) that significantly boosted stability and bioavailability. Furthermore, these NPs improved the cognitive and learning potential of transgenic mice and reduced Aβ peptide aggregates in the mice's brains.77 In a different study, Zhang et al. described a phage-cloned peptide called SAQIAPH (PCu) that completely stopped [Aβ/Cu2+]-mediated Aβ aggregation, controlled metal ion levels to lessen their harmful effects, and lowered Cu2+-induced cell damage and oxidative stress.78

As noted in the above discussion, His-rich metal-peptide chelators and chimeric metal-peptide strategies have been very successful in identifying Aβ inhibitors. Peptide conjugates identified using structure-based approaches show promising results. Using the ATCUN motifs to get a number of metal-peptide chelators could be very useful in finding peptide-based analogues that can block Aβ.

4. Stapled peptides and other peptide/mimetics

Stapling of peptides is a macrocyclization strategy involving cross-linking of the side chain of amino acids to the side chain of another amino acid of the native peptide or its terminus. This cyclization strategy restricts the peptide conformation and improves the peptide's α-helical conformation. In recent years, stapled peptides have gained considerable attention as potential candidates for macrocyclic peptide/mimetics owing to an increase in their binding affinity with target proteins, improved cell penetration ability, and enhanced proteolytic stability. To logically build a peptide/mimetic, different stapling methods have been used, such as lactamization, ring-closing metathesis, click reaction, Cys–Cys stapling, thioether formation, N-alkylation or N-aromatization, and bisalkylation.79Table 3 illustrates several stapled peptides designed to prevent amyloid fibril formation.

Table 3. Stapled peptides and other peptides and mimetics.

| S. No. | Peptide/mimetic | Screening | Strategic outcome/mechanism of action |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | KLVFF derived stapled peptides | In vitro | Acts as modulators for Aβ40-induced self-aggregation, exhibits disruption of preformed fibrils80 |

| 2. | Cyclic 22-mer, CG3 | In vitro | Exhibits neuroprotective effects against Aβ-induced toxicity, prevents Aβ fibril formation81 |

| 3. | Stapled-GCBP | In vitro | Exhibits 10 000-fold higher inhibitory potential towards Aβ fibril formation as compared to GCBP, clears Aβ fibril deposits82 |

| 4. | d-[(Chg)Y(Chg)(Chg)(N-Me-L)]-NH2 | In vitro | Inhibits Aβ aggregation and associated neurotoxicity83 |

| 5. | NAPVSIPQ (NAP) | In vivo | Exhibits intrinsic β-sheet breaking characteristic, protects against toxic Aβ fibrils, improves cognitive functioning84 |

| 6. | d-(GABA)-FPLIAIMA | In vitro | High binding affinity towards Aβ fibrils, displays high plasma stability, inhibits Aβ aggregation85 |

| 7. | Thymine-K(N-Me-G)V(N-Me-G)F(N-Me-G) and barbiturate-KLVFF | In vitro; in vivo | Inhibits Aβ-induced aggregation, disaggregates preformed fibrils86 |

| 8 | RA-1 | In vitro; in vivo | Exhibits proteolytic stability, interferes with the hydrophobic interactions of Aβ monomers and inhibits Aβ fibril formation, exhibits improved cognitive functioning87 |

| 9. | Trehalose-conjugated peptides of iAβ5p | In vitro | Exhibits enhanced protection against Aβ-induced neurotoxicity compared to iAβ5p, inhibits fibrillogenesis89 |

| 10. | LPFFD-mPPCs | In vitro; in silico | Blocks Aβ40 aggregation by undergoing remodeling from fibril formation to amorphous aggregates90 |

| 11. | Nα,Nε-Di-Z-l-lysine hydroxysuccinimide ester, DZK | In silico | Interacts with Aβ monomer, hinders conformational transition to β-sheet structure, stabilizes α-helical structure, and inhibits oligomerization91 |

| 12. | Fmoc-DY-OH | In silico | Exhibits neuroprotective effects against Aβ-induced toxicity, inhibits Aβ aggregation92 |

| 13. | VWRLLAPPFSNRLLP (GCBP) | In vitro | Exhibits high affinity for Aβ, inhibits Aβ fibril formation, clears Aβ deposits while acting as a sweeper, suppresses neuronal cell damage93 |

4.1. Stapled peptides as amyloid-beta inhibitors

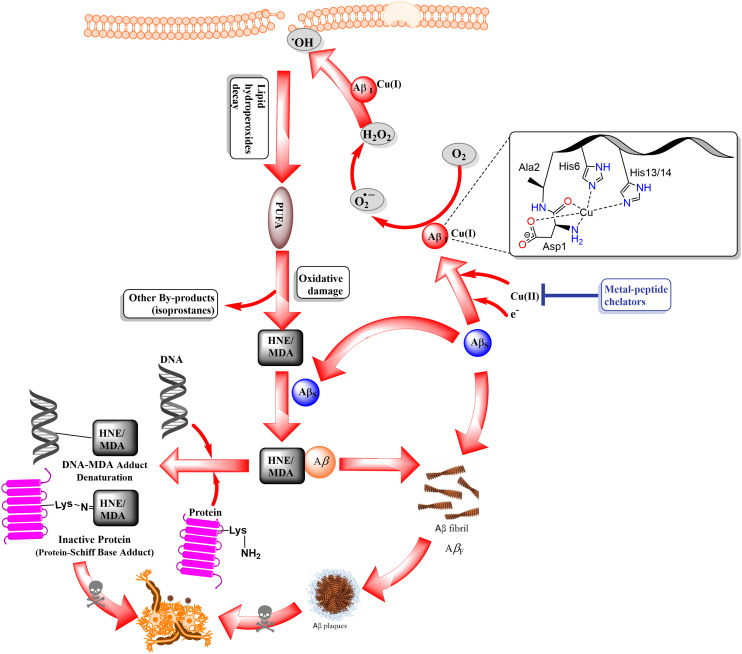

In 2021, Kalita et al. reported a library of “tail-to-side-chain” stapled peptides via lactamization, based on the KLVFF sequence (10–15, Fig. 4). All the stapled peptides acted as modulators of Aβ40 self-aggregation and exhibited disruption of preformed fibrillary aggregates into non-toxic species. The study suggested that these stapled peptides are promising amyloid aggregation inhibitors.80 Transthyretin (TTR) has shown promise in blocking Aβ aggregation and is seen as a possible model for creating and designing anti-Aβ peptides. Recently, researchers designed a series of cyclic peptides using TTR as a template, seeking peptides with enhanced efficacy. The study used TANGO as an amyloid prediction algorithm and found a cyclic peptide called CG3 (16, Fig. 4) that had a strong affinity for Aβ. The peptide has improved stability, specificity, and solubility, and is a useful lead.81 Miyamoto et al. prepared an array of stapled proteins derived from GCBP. This study incorporated Cys residues into the GCBP peptide, followed by cyclization through a disulfide bond. One of the designed stapled peptides (17, Fig. 4) had 10 000 times more inhibitory effect on the formation of Aβ fibrils than GCBP. The cyclized peptide cleared Aβ fibril deposits and suppressed toxic fibril formation.82

Fig. 4. Stapled peptides as Aβ aggregation inhibitors.

4.2. Peptide/mimetics as amyloid-beta inhibitors

Kokkoni et al. synthesized a library of N-methylated peptides (meptides) by carrying out structural manipulation on the Aβ16–20 motif and revealed a peptide SEN304, d-[(Chg)Y(Chg)(Chg)(N-Me-L)]-NH2, that significantly reduced Aβ aggregation to 43% in the ThT fluorescence assay and exhibited 90% protection against Aβ42-induced toxicity in the MTT cell viability assay.83 Octapeptide NAPVSIPQ (NAP), derived from activity-dependent neuroprotective protein, exerted a broad spectrum of neuroprotective effects on intranasal administration at femtomolar concentrations. NAP has the ability to break β-sheets on its own, which lets it work as a peptide chaperone and protects against the harmful Aβ plaques that are linked to AD. AL-108, an intranasal formulation of NAP, has shown a positive impact on memory function in patients with mild cognitive impairment.84 A recently discovered sequence d-(GABA)-FPLIAIMA (18, Fig. 5) was found to have a high binding energy and affinity for Aβ fibrils. The peptide displayed excellent plasma stability and inhibition against Aβ aggregation.85

Fig. 5. Peptide/mimetics as amyloid beta inhibitors.

In a study, Rajasekhar et al. created four new hybrid peptide–peptoid-based modulators from the Aβ motif “KLVFF” by adding several hydrogen bond donor–acceptor moieties, such as sarcosine and thymine/barbiturate. The ThT study found two KLVFF-based hybrid peptide–peptoid modulators 19 and 20 (Fig. 5) that were very good at stopping Aβ42 from aggregating, working at a concentration of 1 : 2 (Aβ42 : modulator). The time-dependent reversal assay showed significant inhibitory potential against preformed Aβ42 aggregates. TEM analysis revealed the complete absence of fibrils on incubation of monomeric Aβ42 or preformed aggregates in the presence of modulators, suggesting inhibitory potential and dissolution ability towards Aβ aggregates.86 Roy et al. recently used a backbone modification strategy on an Aβ-derived sequence, KLVFFA, and made a peptoid RA-1 that stops Aβ from aggregating. RA-1 (21, Fig. 5) was stable when proteolytic conditions were present, it kept microtubules stable, and it stopped the formation of Aβ fibrils by blocking the hydrophobic interactions between Aβ monomers. Furthermore, RA-1 significantly reduced ROS production and improved cognitive functioning in the rat model.87

Trehalose exhibits inhibitory potential against Aβ-induced aggregation and significantly reduces its toxicity.88 Using a method that involves linking trehalose to inhibitory peptides, Bona et al. created trehalose-linked peptides of the known β-sheet breaker peptide iAβ5p. They conjugated the peptides by covalently attaching the disaccharide to various sites of the peptide, including the N-terminus, C-terminus, and side chain of Asp. All peptide conjugates exhibited enhanced protection against Aβ42 toxicity compared to the peptide alone or trehalose alone. The ThT study showed that these glycopeptides effectively inhibit Aβ fibrillogenesis.89 Jiang et al. developed a range of multivalent polymer–peptide conjugates (mPPCs) by conjugating poly(HPMA-co-NHSMA) to various inhibitor ligands, such as LVFFD, LVFFN, and G(mG)L(mG)F(mG)A, resulting in the production of LD-mPPCs, LN-mPPCs, and GA-mPPCs. These formulated mPPCs were investigated for inhibitory effects against Aβ40 aggregation. The research showed that the negatively charged ligand, LPFFD-derived mPPCs (LD-mPPCs), worked better than other ligands and effectively stopped Aβ40 from aggregating by changing it from fibrils to amorphous aggregates. The MD simulations showed that all the conjugates formed globular structures, which favored ligand–ligand interactions and made them unavailable for interactions with Aβ. Therefore, a delicate harmony is achieved between ligand–ligand and ligand–Aβ to inhibit Aβ.90 Guisasola et al. designed a peptide mimetic Nα,Nε-Di-Z-l-lysine hydroxysuccinimide ester, DZK (22, Fig. 5), that interacted with the Aβ monomer and hindered the conformational transition to β-sheets while stabilizing the α-helical form, thereby preventing the oligomerization.91 Gera et al. designed a series of peptide mimetics derived from DZK. The study found a peptide 23 (Fig. 5) that significantly decreased the intensity of ThT fluorescence. TEM analysis showed that mimetic 23 altered the aggregation kinetics but was incapable of hindering the fibril formation.92 Matsubara et al. investigated the inhibitory effect of the ganglioside cluster-binding peptide VWRLLAPPFSNRLLP (GCBP) on Aβ-accumulation on neuronal (liposome) membranes and associated cytotoxicity on PC12 cells. It turned out that GCBP has a very strong affinity for Aβ. It stopped the formation of Aβ fibrils (IC50 = 12 pM) and cleaned up the harmful Aβ deposits like a scrubbing brush. The results suggested that GCBP suppressed neuronal cell damage and aggregation-induced death.93

Peptide mimetics, including peptoids and stapled peptides as inhibitors of Aβ, is a strategy that is still evolving. Despite research in this field, further efforts could yield promising candidates.

5. Peptide-based nanomaterials

Over the past few decades, the advent of nanotechnology has led to the utilization of various nanomaterial-based approaches in therapeutics development, due to their enhanced biocompatibility and stable physicochemical characteristics. This includes gold-based, carbon-based, metal oxide nanomaterials, 2D nanosheets, metal–peptide frameworks (MPFs), metal–organic frameworks (MOFs), and self-assembled nanomaterials. The size, shape, functionality, and concentration of gold-based nanoparticles (AuNPs) affect how well they pass through the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and how well they stop Aβ from aggregating. Researchers have also reported several peptide hybrid-functionalized gold nanomaterials with enhanced stability and increased delivery efficiency to the brain.94–98 Peptide-based neurotherapeutics (PBNTs) have emerged as a favorable approach to overcome CNS-associated disorders, including AD. Even though peptide-based neurotherapeutics have a lot of pharmacodynamic effects, like being strong, specific, and affinity-based for biological target proteins, they are very susceptible to proteases and have poor pharmacokinetic profiles.99 This significantly decreases their candidateship in terms of clinical applicability and significantly reduces their chances in clinical trials. The FDA has approved a number of peptides as clinical agents.100–104 However, several of them remained proteolytically unstable for proteases and had ineffective pharmacokinetic (PK) profiles (short t1/2), resulting in faster elimination.105 In the last five decades, nanomaterial-based nanomedicines have extensively gained the attention of researchers. Neuronanotechnologically manipulated peptide-based neurotherapeutics or peptide-based nano-neurotherapeutics (PBNNTs) exhibit enhanced PK/PD profiles. Nanotherapeutic approaches can improve stability by effectively binding and masking off ligands with nanocarriers or nanoparticles.106 Peptide-metal nanoparticles (AuNPs, AgNPs, WNPs, Ru/AuNPs), lipopeptides and peptide-liposomes (LPs) glycopeptides, lipoglycopeptides, and nanoconjugates improve the blood–brain barrier (BBB) permeability, lower the effect of first-pass metabolism, and stop liver damage and kidney clearance, besides target specificity.107,108 A number of PBNNTs have great anti-amyloidogenic properties. They can also stop ROS production due to oxidative stress, and are represented in Table 4. The Aβ15–21 CHC-inspired peptides such as FF, KLVFF, LK7, and RK10 have emerged as potent Aβ inhibitors. However, they also exhibit a high propensity for self-aggregation and toxicity. In order to reduce self-toxicity and enhance the PKPD of CHC-inspired and other inhibitory peptides, researchers employ nanotechnological strategies such as the nanomaterialistic peptide–metal nanoparticle approach, which involves the use of metal peptides such as W, Au, Ag, and their complexes. Metal–peptide (M@P)-NPs significantly improve anti-amylogenic effects, provide impetus in anti-Aβ-oligomerization and fibrillogenesis, fabricate complexed heterogeneous amorphous fibrillo-aggregates, and mitigate Aβ-peptide cytotoxicity. Also, NPs promote the stability and BBB penetration of peptides.

Table 4. Peptide-based nanoneurotherapeutics (PBNNTs) targeting amyloidosis.

| S. No. | Peptide-based nanoneurotherapeutics (name) | Screening | Strategic outcome/mechanism of action |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | CLVFFA–gold nanoclusters (AuNCs@CLVFFA) | In vitro | Inhibits Aβ aggregation/fibrillogenesis, prolongs mature fibril formation, promotes disaggregation at lower doses than CLVFFA inhibitory peptide109 |

| 2. | Ac-CLPFFD–gold nanoparticles (AuNPs@POMD-Pep) | In vitro, In vivo | Acts as a multifunctional anti-Aβ aggregation and anti-fibrillogenesis inhibitor, perturbated fibrils, and antioxidant activity (ROS silence and reduced ROS formation) with improved BBB penetration110 |

| 3. | K8[P2CoW17O61]-Ac-QKLVFF-NH2 nanospheres (NSs) (POM@P) | In vitro, In vivo | Improved anti-Aβ aggregation and fibrillogenesis and more neuroprotective than Aβ15–20 and K8[P2CoW17O61] alone, and destabilizes Aβ-plaques in the mice's CSF111 |

| 4. | CGGGLPFFD and CGGGGGLPFFD–gold nanoparticles (PFGNPs) | In vitro | Shows anti-Aβ aggregative/anti-fibrillatory action and rescued SH-SY5Y from Aβ and [Aβ/Cu2]-induced aggregation and Cu2+ scavenger activity112 |

| 5. | RQIKIWFQNRRMKWKK(Pen)–gold–ruthenium-fluorescent nanoparticles (Ru@Pen@PEG–AuNS) | In vitro, In vivo | Inhibits amyloidosis, high BBB permeability and exhibits high propensity to absorb NIR irradiation, showed a photothermal effect on perturbed preform fibrils and plaques, and acts as theranostic agent for AD113 |

| 6. | RΔF-selenium nanoparticles (RΔF-SeNPs) | In vitro, In vivo | Acts as anti-Aβ42 aggregator, excellent BBB penetration and improved cognitive, increases spatial memory, and learning skills by cutting Aβ load114 |

| 7. | LVFFFARKC (LK7)-black phosphorus (BP)-PEG nanosheets (PEG-LK7@BP) | In vitro | Improved anti-fibrillogenesis potential by restoring conformational changes of Aβ as compared to LK7 and decreased LK7 self-aggregation115 |

| 8. | LK7@PLGA-NPs | In vitro | Displayed anti-amyloidogenic potential, subdued conformational transition from random coil structure to β-sheets, and formed unstructured amorphous aggregates116 |

| 9. | Ac-LVFFARK-NH2 (LK7)-PIMA-DMEA (LK7@pID) | In vitro | Interfered in Aβ-co-assembly and reduced Aβ-aggregates and fibrillogenesis processes to fabricate noncytotoxic, complexed heterogeneous Aβ-fibrillo-aggregates117 |

| 10. | Ac-LVFFARKC-NH2 (LC8)-poly(carboxybetainemethacrylate-glycidyl methacrylate) [p(CBMA-GMA) or pCG] nanoparticles (LC8-pCG and LC8-pCG-fLC8) | In vitro, In vivo | Inhibits amyloidosis/fibrillogenesis, AD theragnostic, higher activity than LC8-pCG, effectively reduced Aβ accumulation, and enhanced the longevity of C. elegans by five days118 |

| 11. | KLVFF-poly(d,l-lactide-co-glycolide) acid loaded NPs (K-NPs) | In vitro | Enhanced anti-Aβ aggregation activity, bioavailability, and BBB permeability, and subside self-aggregation as compared to KLVFF peptide119 |

| 12. | Ac-rGffvlkGrrrrqrrkkrGy-NH2-PINPs | In vitro | Showed inhibition of amyloid oligomerization, high BBB permeability and protection against memory loss and neuronal damage120 |

| 13. | CS–Km–Bn@Aβ | In vitro, In vivo | Cleared Aβ aggregates, increased the cell viability of Aβ-treated cells, and increased the soluble aggregates in transgenic AD mice, resulting in improved cognitive functioning121 |

| 14. | Poly-(N-acryloyl-FF-methyl ester) poly-A-FF-ME nanoparticle | In vitro | Fibrillogenesis inhibition and neuroprotective122 |

| 15. | Cyclic d,l-α-peptide, CP-2 | In vitro | Inhibits Aβ fibrillogenesis, disaggregated preformed fibrils, and protected PC-12 cells from Aβ-induced toxicity123 |

| 16. | Cyclo[Kl-Nle-wHs] (CP2) CP-2 nanotubes [azaXaa]-1 | In vitro, In vivo | High anti-Aβ aggregation, also fibrillolytic activity on preexisting aggregates compared with the CP-2 peptide, acts like a chaperon, in transgenic C. elegans, and showed good anti-amyloidogenic activity and morbidity124 |

| 17. | Chemiluminescent Cy5, Cyclo[Kl-Nle-wHs] (CP2)-liposomes conjugated (Cy5-CP-2-LPs) | In vitro, In vivo | Rescued C. elegans from Aβ-aggregates, prevented chemotaxis reactions, good BBB penetrability, and theranostic for AD125 |

| 18. | Cyclo[CRTIGPSVC] (CTR)-PLGA-PQVGHL (S1) peptide-curcumin nanoparticles (CRT-NP-S1-Cur) | In vitro, In vivo | Good anti-Aβ action and biocompatibility, good BBB penetrability, inhibited Aβ–Ag generation and reduced inflammatory cytokines (IL-6 and TNF-α), ripped ROS formation, enhanced SOD activities, and suppressed the burden of Aβ in AD mice brains126 |

| 19. | RVG–peptide nanoparticles (RVG@Met@SNPs) | In vitro, In vivo | Anti-self-assembly activity, rescued neuronal cells from [Aβ/Cu2+] complex-induced cytotoxicity, prevents ROS formation, and improves BBB availability, in vivo, improvement in cognitive ability, behavioral skills, and spatial memory127 |

| 20. | Molecularly imprinted nanoparticles (MINPs) with Aβ40 10 residue sequences | In vitro | Showed potent Aβ inhibitory activity, and strong anti-aggregative and disassembly activity128 |

5.1. Peptide-metal-based nanomaterials as neurotherapeutics

Metal-based nanoparticles (M@NP) have notable loading capacity due to the availability of a larger surface area. Peptide–metal nanoparticles (AuNPs, WNPs, and Ru/AuNPs) were able to stop Aβ from aggregating and stopped the formation of fibrils (Table 4). Hao et al. created a nanocomposite by conjugating the central hydrophobic motif CLVFFA on the gold cluster surface, resulting in an inhibitor, AuNCs-CLVFFA. The CLVFFA-functionalized nanocluster showed Aβ40 peptide inhibitory activity, slowed down fibrillogenesis, and broke up mature fibrils that were already formed. In addition, CLVFFA-AuNCs were biocompatible in studies of cell viability and stopped the formation of β-sheets in studies of secondary structure.109 Gao et al. fabricated a hybrid nanocomposite inhibitor with gold nanoparticles that had polyoxometalate with a Well–Dawson structure (POMD) attached to their surface. They then joined it with a β-sheet breaker peptide, Ac-CLPFFD, to make AuNPs@POMD-Pep. The multifunctional inhibitor stopped Aβ aggregation, and reduced Aβ-induced peroxidase activity and cytotoxicity. The research showed that AuNPs@POMD–Pep had great BBB permeability and worked well as an inhibitor in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).110 The same group demonstrated the preparation of nanospheres decorated with polyoxometalate–peptide (POM@P) by mixing the polyoxometalate-core (K8[P2CoW17O61]) with the anti-amyloid peptide Ac-QKLVFF-NH2. The POM@P hybrid nanospheres were better at stopping Aβ from aggregation. They also protected neurons better than Aβ15–20 and (K8[P2CoW17O61]) alone, and made Aβ-plaques less stable in the CSF of mice.111 Zhou et al. designed a bifunctional inhibitor by conjugating Gly-rich polypeptides, CGGGLPFFD and CGGGGGH, onto the AuNPs through an Au–S bond to produce gold NPs. The research showed that PFGNP could stop Aβ from aggregating and protect human neuroblastoma cells from the damage that Aβ causes. PFGNP displayed a significant chelating effect towards Cu2+ and inhibited Cu2+-mediated aggregation.112 Yin et al. designed a peptide nanocomposite, Ru@Pen@PEG–AuNS, consisting of a cell-penetrating peptide, RQIKIWFQNRRMKWKK (Pen), loaded onto a PEGylated Au nanostar and modified with a Ru(ii) complex. This Au nanostar effectively arrested Aβ fibrillogenesis, dissociated preformed fibrils, and mitigated Aβ-induced neurotoxicity under NIR irradiation, owing to AuNS being characteristic of NIR absorption. In addition, Ru@Pen@PEG–AuNS demonstrated high biocompatibility and hemocompatibility, as well as enhanced BBB permeability.113 Kour et al. formulated multifunctional amphipathic Arg-α,β-dehydrophenylalanine (RΔF)-selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs). RΔF-SeNPs displayed neuroprotective effects towards Aβ aggregation-induced toxicity in neuroblastoma cells and AD-like (streptozotocin-treated) neuronal cells. RΔF-SeNPs mitigated neuronal toxicity, efficiently reduced intracellular ROS levels, and exhibited Aβ42 disaggregating potency. In in vivo studies, these multifunctional NPs showed a decrease in Aβ deposits in the brain tissues of AD rat models, resulting in improved cognitive and spatial memory.114 Yang et al. fabricated a nanosystem composed of an Aβ inhibitory peptide, LVFFARK (LK7) loaded onto black phosphorous nanosheets (BP NSs), and coupled it with PEG to obtain PEG-stabilized LK7@BP nanosheets (PEG-LK7@BP). This resulting nanoformulation suppressed the conformational change from random coil to β-sheet structure, attenuated Aβ-induced toxicity in SH-SY5Y cells, and exhibited high binding affinity towards Aβ, resulting in decreased Aβ–Aβ interactions.115 Xiong et al. designed a nanosized inhibitor, LK7@PLGA-NPs, by conjugating LK7 onto the surface of PLGA nanoparticles. This newly fabricated nanoparticle-based inhibitor exhibited potent anti-amyloidogenic activity, suppressed conformational transition from random coil structure to β-sheets, and redirected Aβ fibrillogenesis to unstructured amorphous aggregates.116 Wang et al. reported a polymer–peptide conjugate, LK7@pID, that mitigated Aβ-aggregation-induced cytotoxicity. However, an unusual behavior was observed where the LK7@pID conjugate promoted Aβ fibrillization and resulted in a higher number of fibrils compared to the Aβ system alone. The study demonstrated the ‘Trojan horse’-like behavior of the peptide conjugate, which catalyzes Aβ fibrillization by co-assembling with Aβ fibrils to form non-toxic fibrillar aggregates.117 Later, Wang et al. fabricated a bifunctional nanoparticle, LC8-pCG-fLC8, composed of Ac-LVFFARKC-NH2 (LC8) tagged with a fluorescent probe ‘f’ and further linked it to poly(carboxybetainemethacrylate-glycidyl methacrylate) [p(CBMA-GMA) or pCG] utilizing click chemistry. This self-assembled nanostructure displayed considerable inhibitory efficiency and remodeled the aggregation process. The in vivo study demonstrated that LC8-pCG-fLC8 NPs could effectively image amyloid deposits in transgenic C. elegans strain. This was due to their good binding affinity, good biostability, and excellent fluorescence responsivity towards amyloid oligomers and fibrils. These self-assembled nanoparticles are believed to possess great potential as theranostic agents for AD diagnosis.118

Polymeric nanostructures of Aβ inhibitory peptides are known to enhance their potency and stability by formulating into lipopeptides, lipoglycopeptides, and nanoconjugates using liposomes, nanosomes, nanosheets, clusters, and micelles. There have been reports of several peptide-based nanoneurotherapeutics (PBNNTs) demonstrating excellent anti-aggregation, anti-fibrillogenesis activity, and protection against Aβ-aggregation-induced neurotoxicity. Pederzoli et al. fabricated KLVFF-polymeric engineered nanoparticles (K-NPs) by loading KLVFF on poly(d,l-lactide-co-glycolide) acid (PLGA). KLVFF-loaded NPs displayed enhanced activity compared to free KLVFF, owing to the peptide's increased stability. In addition, the research findings demonstrated that K-NPs showed improved bioavailability and enhanced BBB permeability in contrast to the free peptide.119 Gregori et al. utilized click chemistry to prepare a nanoformulation composed of retro-inverso peptide, Ac-rGffvlkGrrrrqrrkkrGy-NH2, anchored to nanoliposomes. The research showed that the specially made peptide inhibitor nanoparticles (PINPs) stopped amyloid oligomerization, and exhibited protection against pre-aggregated Aβ-induced toxicity in SHSY-5Y cells. It exhibited high BBB permeability and demonstrated protection against memory loss and neuronal damage.120

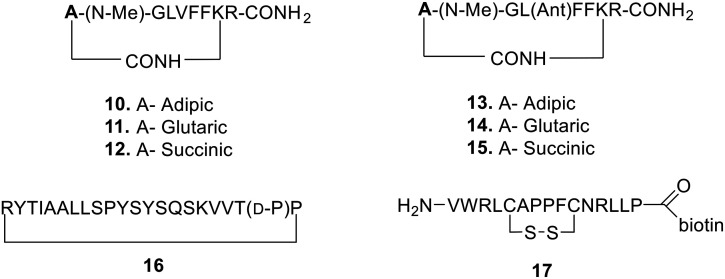

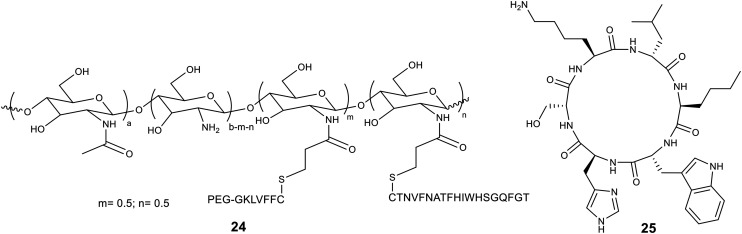

Luo et al. reported a self-destructive peptide-polymeric nanosweeper, CS–Km–Bn (24, Fig. 6). CS–Km–Bn was constructed utilizing cationic chitosan (CS) linked to PEG-GKLVFF (K) and TGFQGSHWIHFTANFVNT (Beclin-1 or B). This nanosweeper captured Aβ and co-assembled to form CS–Km–Bn@Aβ, resulting in clearance of Aβ by activating autophagy and accelerating Aβ degradation. Moreover, the nanosweeper increased the cell viability of Aβ-treated cells. The in vivo studies showed that the transgenic AD mice brains had a lot less insoluble and soluble Aβ aggregates, which improved their cognitive functioning.121 Skaat et al. reported the fabrication of amino-acid-based polymer nanoparticles, poly(N-acryloyl-l-phenyl-alanyl-l-phenylalanine methyl ester) (polyA-FF-ME), composed of hydrophobic amino acids in the side chain of the polymer. These engineered nanoparticles exhibited minimal cytotoxicity on the PC-12 and SH-SY5Y cells. ThT binding studies showed that the nanoparticles changed the nucleation of Aβ40 because Aβ40 and nanoparticles had a strong binding interaction. The CD studies showed that nanoparticles slowed down the change in structure from random coil to β-sheet. The TEM analysis showed that the built nanoparticles slowed down the fibrillation process because of how they interacted with Aβ.122

Fig. 6. Structure of nanosweeper CS–Km–Bn (24) and CP-2 (25).