Abstract

Improving dietary intake during pregnancy can mitigate adverse consequences for women and their children. The effective techniques and features for supporting and sustaining dietary change during pregnancy and postpartum are minimally reported. The primary aims of this systematic review and meta-analysis were to summarise the effectiveness of dietary interventions for pregnant woman, identify which behaviour change techniques (BCTs) and intervention features were most frequently used and determine which were most effective at improving dietary intake. Six databases were searched to identify randomised control trials (RCTs) reporting on dietary intake in pregnant women over the age of sixteen, with an active intervention group compared to a control group receiving usual care or less intensive interventions. The Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool 1 was used to assess study validity. BCTs were coded by two authors using Michie et al.’s BCT taxonomy V1. A random effect model assessed intervention effects on indices of dietary quality and food groups (fruit, vegetables, grains and cereals, meat, and dairy) in relation to the use of BCTs and intervention features. Thirty- seven RCTs met the inclusion criteria. High heterogeneity was observed across intervention characteristics and measures of fidelity. Only half of the available BCTs were used, with eleven used once. The BCT category Reward and threat was successful in improving dietary quality and vegetable intake, whilst 'Action planning’ (1.4) from the category Goals and planning significantly improved dietary quality. Interventions delivered by a nutrition professional and those that included group sessions improved dietary quality more than those delivered by other health professionals, research staff, or application-delivered interventions and delivered via other modalities. Future dietary interventions during pregnancy should incorporate and report on BCTs used in the intervention. Successful design elements for improving antenatal dietary intake may include multimodal interventions delivered by nutrition professionals and the use of Rewards and Goal setting.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12884-025-07185-z.

Keywords: Pregnancy, Diet, Behaviour, Meta-analysis, Antenatal interventions, Behaviour change techniques

Key messages

Defining the behaviour change techniques (BCTs) used within interventions allows them to be replicated, for the links between BCTs and mechanisms of action to be identified and for efficient intervention design.

Interventions delivered by a nutrition professional and those that include group sessions were significantly more effective at improving dietary quality compared with other health professionals (i.e., midwives, nurses, gynaecologists), research staff, and application-delivered interventions and via other modalities.

Reward was the most comparatively promising BCT category for improving dietary quality and vegetable intake, whilst the individual BCT 'Action planning’ (1.4) from the category Goals and planning was the most comparatively promising for improving dietary quality.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12884-025-07185-z.

Background

Optimising maternal diet during pregnancy can enhance short- and long-term health of the mother and has intergenerational benefits [1–6]. Following pregnancy, maternal dietary behaviour continues to be important to reduce postpartum weight retention and reduce long-term chronic disease risk and optimise maternal and infant health outcomes in subsequent pregnancies [7].

Pregnancy and breastfeeding-specific dietary guidelines provide recommendations on intakes of foods, food groups, and dietary patterns to meet increased nutritional requirements to support fetal growth and development for a healthy pregnancy and breastfeeding [8, 9]. Current alignment with pregnancy dietary guidelines is low [10, 11]. Across the last decade, 1 to 4% of pregnant women were estimated to meet recommended daily intakes of grains and cereals, 50 to 56% met fruit intakes, 2 to 26% met recommended vegetable intakes, 10 to 18% met recommended intakes of meat and alternatives, and 13 to 22% met dairy and alternatives intakes [8–14]. Instead, pregnant women’s dietary patterns were characterised by high intakes of energy-dense and nutrient-poor foods— contributing up to one-third of dietary energy intakes [10, 15]. Observational and intervention studies reported a decline in fruit and vegetable intakes and an overall decline in dietary quality during the transition from pregnancy to postpartum [15]. With few pregnant women following dietary patterns that align with dietary recommendations, there is a need for interventions that are effective at improving the dietary behaviours of women during pregnancy.

Pregnant women1 [16] report many reasons for not consuming dietary intakes consistent with dietary guidelines during pregnancy and postpartum. Women’s dietary behaviours are influenced by an interplay of intrinsic and extrinsic factors that can positively or negatively influence behaviour change depending on the individual [17]. A common theme that arises from the literature is the focus on women’s motivation, which can have a dual impact on behaviour, underpinned by a desire to improve their own and their baby’s health, and a resistance to conforming to beauty standards [12, 17]. Solely emphasising motivation during pregnancy and postpartum overlooks the influence of other crucial elements in behaviour change [18]. Limited access to essential pregnancy-related knowledge and information for women is exacerbated by time constraints, financial barriers, access to core foods, familial responsibilities, work commitments and the absence of flexible, multimodal healthcare options, hindering their capability and opportunity to make sustained behaviour change [12, 18–20]. These barriers can be grouped within capability and opportunity, and together with motivation, form the COM-B model, a theoretical framework that can be used to understand and influence behaviour [18].

A deeper understanding of the active components and intervention features used in pregnancy dietary interventions is needed to inform the design and delivery of effective interventions in research and clinical practice. Behaviour change techniques (BCTs) are defined as ‘active ingredients’ of interventions designed to change behaviour [21]. To date, clear documentation and delivery of interventions underpinned by effective BCTs have been hampered by poorly defined and/or understood components for achieving behaviour change [21]. Efforts to standardise the reporting of BCT interventions and their theoretical underpinnings to overcome this deficit have resulted in the identification of 93 separate BCTs (within 16 categories), specified within an updated validated taxonomy: the BCT taxonomy version 1 (BCTTv1) [21]. BCTs have been identified in systematic reviews and meta-analyses examining behaviour change in pregnancy for gestational weight gain (GWG) [22] and physical activity [23]. They have also been identified for improving dietary intake in other population groups [24]. No systematic reviews have examined the effectiveness of BCTs in improving women’s dietary intake in pregnancy. Identifying the most effective BCTs used in interventions to improve dietary intakes of pregnant women could inform evidence-based pregnancy guidelines, policies, and translation to antenatal care practices.

The primary aims of this systematic review and meta-analysis were to summarise the effectiveness of dietary interventions for pregnant woman, identify which BCTs and intervention features were most frequently used in these interventions and determine which were most effective at improving dietary intake. Secondary aims were to determine the impact of dietary interventions on Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM), GWG and maintenance of dietary change postpartum, we also aimed to determine which BCTs were effective for supporting a maintenance of dietary changes beyond pregnancy.

Methods

This systematic review protocol was prospectively registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; CRD42022350505) and is reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020; supplementary material 1) [25]. Minor changes were made to the initial protocol prior to full-text review; these are recorded in PROSPERO with explanations for the amendments.

Eligibility criteria

The eligibility criteria for study inclusion is listed below in Table 1.

Table 1.

Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes and Study (PICOS) criteria for included studies

| Study component | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Pregnant women over 16 years of age | Pregnant women in specialist care for a medical diagnosis including physical and mental health conditions and women experiencing pregnancy complications |

| Intervention | Interventions including one or more BCTs aimed at improving dietary intake | Interventions claiming to change dietary intake without describing specific BCTs or with insufficient detail provided for BCT codinga |

| Comparators | Usual care or a less intensive intervention | No reported control |

| Outcome |

Primary: Between group change in the following dietary measures: fruits, vegetables, grains and cereals, meat and alternatives, dairy, discretionary foods and dietary quality measure scores (providing an indication of overall intake pattern of an individual’s diet—encompassing both quality and variety [26]) Secondary: GWG (according to pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI)), GDM diagnosis and maintenance of dietary change post pregnancy |

- |

| Study designs |

Published, peer reviewed RCTs, cluster RCTs and pilot RCTs No limitations were placed on country of origin, language of publication, or length of follow up |

All other study designs |

BCTs Behaviour change techniques, RCT Randomised control trials

aWhilst BCTs were coded by the research team (described below), a minimum level of description was necessary to identify and categorise BCTs accurately

Search strategy

Six electronic databases were searched: MEDLINE (via Pubmed), CINAHL (via EBSCOhost), EMBASE (via Elsevier), Psychinfo (via EBSCOhost), CENTRAL (via Wiley) via Cochrane Library and Web of Science (Core collection all editions 1900—present) from inception to 24 July 2022. Keywords included search strings relating to: (Pregnancy) AND (behaviour change/techniques/areas of change) AND (diet) AND (intervention). Terms were generated with the assistance of a research librarian. Search terms and search procedures are detailed in full in supplementary file 1.

Screening

Search results were combined into Covidence systematic review software (www.covidence.org) and duplicates were removed. Titles and abstracts of all identified records were screened against eligibility criteria individually, and in parallel, by two reviewers (HO, NM, AR, JH, and SdJ). Conflicts were resolved by a third reviewer, where uncertainty remained the full paper was examined. Full text screening was likewise conducted independently and in parallel by two reviewers (HO, NM, LV, AR) with disputes resolved by a third reviewer (SdJ). Manual searches were conducted on the reference list of eligible articles following screening to identify additional studies.

Data extraction

Data from each included study was dual extracted in Covidence™ (HO, NM, LV, BW, SG), where discrepancies arose, consensus was reached through discussion with a third reviewer resolving disputes not resolved through discussion (SW). The data extraction template was developed based on the Workgroup for Intervention Development and Evaluation Research (WIDER) framework for reporting on the content of behaviour change interventions [27]. Extracted data included detailed description of the intervention (participant information, sample size, intervention features and reported fidelity/ engagement measures), detailed description of control group (participant information, sample size and intervention features) and BCTs included in control and intervention groups. Extracted intervention features included: duration of intervention (weeks); setting (e.g., clinical, community, academic); delivery format (e.g. in-person, telephone calls, mobile application); delivery personnel (e.g. nutrition professional—dietitian or nutritionist, researcher, midwife, other); and the explicit theoretical model mentioned to underpin the intervention. Dietary measures pre-intervention, at the latest reported gestation in pregnancy and postpartum, where possible, were extracted from studies. Missing values of standard deviation (SD) were calculated from standard error (SE), t and p-values, using the Cochrane guidelines [28]. Where data were normally distributed and reported as median (IQR), it was converted to mean (SD) using Hozo’s Formula using range [29]. Where data are missing, original study authors were contacted for further details. We also extracted GDM diagnosis reported according to the International Association of the Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Group (IADPSG) criteria [30] at 24 to 28 weeks and GWG. Where studies employed more than one intervention arm, the most active intervention and the most passive comparison were selected. This approach was chosen to avoid a unit-of-analysis problem or combining interventions, which would have complicated the interpretation of the effective BCTs. The most active intervention was defined as the one that applied the highest number of BCTs. The 'most passive' comparison was defined as the control or usual care group with the least BCTs.

Behaviour change technique coding

The BCTs in the intervention and control arms of the study were identified using the BCTTv1 [21], a validated taxonomy consisting of 93 BCTs in 16 categories. Two reviewers (HO and SD) independently coded the BCTs from pre-extracted BCT phrases from the intervention descriptions and supplementary materials/protocol papers where available. Both reviewers had completed the BCTTv1 online training (www.bct-taxonomy.com). A BCT was only coded if there was unequivocal evidence of its existence and that the BCT applied directly to the target behaviour of changing dietary behaviour. If available and required, study development papers and protocols were retrieved for this purpose. BCTs targeted at increasing exercise were not included given the focus on assessing a change in dietary intake given dietary interventions (or mixed) have been more consistently shown to impact pregnancy outcomes compared with physical activity interventions alone [31, 32]. BCTs in the intervention and control groups were identified separately and only those exclusively applied to the intervention were included in the analysis. Where studies employed more than one intervention arm, BCTs from the most active dietary intervention and the most passive comparison were selected as defined by the largest number of BCTs included in the intervention. Inter-rater reliability was calculated in R using Cohen’s Kappa [33]. Discrepancies were discussed to reach consensus, if no consensus could be reached a third reviewer was consulted (SW). The frequency of individual BCTs in each intervention was not coded.

Risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias of each included study was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool 1 [34]. Risk of Bias Tool 1 was chosen in preference to Tool 2 as it allows for the assessment of biases arising from study funding and conflicts of interest. The risk of bias was dual-assessed (HO, NM, LV, BW, SG), in the case of uncertainty, consensus was reached through discussion. Where consensus could not be reached through discussion a third reviewer was consulted (SW). Key methodological domains assessed by this tool include random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other sources of bias.

Data synthesis

Where outcome data were sufficient, as defined by three or more studies reporting on the same outcome, a meta-analysis was undertaken using Review Manager (v.5.4.1) on the primary outcome measures of dietary quality, the five core food groups, and the secondary outcomes of GDM diagnosis and GWG. In studies that reported on a dietary pattern (e.g. Mediterranean diet), only those where a high diet quality score related to a positive improvement in dietary quality were combined in a meta-analysis: henceforth referred to as dietary quality. Diet quality scores where a high score reflected a decrease in diet quality were not combined. Risk ratios were used for dichotomous outcomes (the number of individuals with an event) or rate ratios for the results reporting the number of events only. Continuous outcomes were reported using mean difference or standardised mean difference, as appropriate. A random effects model was used. The I2 and p-value, determined by Chi-squared (Cochran’s Q) statistic were used to measure heterogeneity among the included studies. When multiple time points were collected during pregnancy the last measure before birth was used, however it was excluded from the meta-analysis if this was before the third trimester of pregnancy (< 27 weeks' gestation), as nutritional requirements differ across pregnancy trimesters. Sensitivity analyses were performed as a deviation from the protocol. This was done for risk of bias, by excluding studies with three or more and two or more high risk of bias scores and for participant weight status by excluding studies that included women with a pre-pregnancy BMI between 25–29.9 kg/m2 or ≥ 30 kg/m2. Sub-group analysis was conducted for each dietary outcome to determine category and individual BCT effectiveness. Studies were classified based on whether they included each specific BCT or BCT category, with two subgroups formed: those using the BCT and those not using the BCT. A random effects model was applied, and the standardised mean difference was reported for each sub-group. Sub-grouping was only done when there were at least two studies per sub-group. Chi-squared statistics and p-values for subgroup differences were reported. Where meta-analysis was not feasible; the results are reported narratively.

Results

Study selection

Thirty-seven studies met inclusion criteria, yielding a pooled population of 17,300 participants (see Fig. 1), from five pilot RCTs [35–39], 28 RCTs [40–67] and four cluster RCTs [68–71]. Out of the 37 studies, six focused solely on dietary behaviours [38, 42, 44, 48, 58, 65], 28 studies addressed dietary and physical activity behaviours, whilst the remaining three studies also targeted stress management [47, 56] and smoking cessation [57]. Summary of the characteristics of included studies are outlined in Table 2.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Table 2.

Summary table of intervention characteristics of included studies

|

Author, Year

Country |

Study design |

Intervention type

Number of participants randomised |

Control | Intervention | Target behaviour | Duration (weeks) | Setting | Explicit theoretical model/theory/framework of behaviour change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Guelinckx, et al. 2010 [51] Belgium |

RCT (three arm) |

Mixed (PA + diet) n = 195 |

Standard Antenatal Care |

3 × 1 hr F2F group Delivered by: Nutritionist (trained in counselling) |

Limit intake energy-dense foods (e.g. fast food and sweets), increasing low-fat dairy products, increasing whole-wheat grains, and reducing saturated fatty acids | 17 | Clinical | NA |

|

Jackson, et al. 2011 [54] HIP United States |

RCT |

Mixed (PA + diet) n = 321 |

Standard Antenatal Care |

2 × 10–15 min Computer program Delivered by: Video doctor program |

Improve women’s diet and PA behaviours during pregnancy | 6 | Clinical | NA |

|

Hui, et al. 2012 [53] Canada |

RCT |

Mixed (PA + diet) n = 224 |

Standard Antenatal Care (including information on PA and nutrition in pregnancy from Health Canada) |

2 × individualised F2F visits Delivered by: Dietitian |

Improve dietary habit, increase PA and achieve recommended GWG | 16 | Community | NA |

|

Wilkinson and McIntyre. 2012 [66] Australia |

RCT |

Mixed (PA + diet) n = 360 |

Standard Antenatal Care (including a booklet with behaviours influencing maternal and infant health outcomes) |

1 × 60 min F2F group ± partners Delivered by: Dietitian |

Improve dietary behaviours (change in meeting fruit and vegetable pregnancy guidelines), improve diet quality index, improve GWG guideline awareness | 12 | Clinical | Social Cognitive theory* |

|

Kieffer, et al. 2014 [56] United States |

RCT |

Mixed: (PA, diet, stress management) n = 278 |

Other: minimal intervention group (3 group pregnancy education sessions) |

2 × individualised F2F home visits, 9 × optional group activities such as healthy cooking demonstrations Delivered by: Community health workers |

Decrease added sugars, total fat and saturated fat, increase fruit, vegetables and fibre | 11 | Community | NA |

|

Kinnunen, et al. 2014 [69] Finland |

Cluster RCT |

Mixed (PA + diet) 14 sites n = 442 |

Standard Antenatal Care |

1 × 20–30 min and 3 × 10–15 min individualised F2F visits Delivered by: Public health nurses |

Achieve a diet with energy intake from < 10% saturated fat, 5–10% polyunsaturated fat, 25–30% total fat, and < 10% saccharose and 25–35 g fibre per day | 29 | Clinical | PRECEDE-PROCEED model and Transtheoretical Model of Health Behaviour Change* |

|

Dodd, et al. 2014 [49] LIMIT Australia |

Multicentre RCT |

Mixed (PA + diet) n = 2212 |

Standard Antenatal Care |

3 × individualised F2F visits and 3 × telephone calls Delivered by: Dietitian (F2F) or research assistants (calls) |

Healthy eating as per ADG (maintain balance of CHO, fat, and protein, reduce high refined CHO and saturated fats, increase fibre, 2 serves of fruit and 5 serves of vegetables and 3 serves dairy daily) | 26 | Clinical | Stage Theories of Health Decision Making |

|

Phelan, et al. 2014 [59] United States |

RCT |

Mixed (PA + diet) n = 401 |

Standard Antenatal Care, included standard nutrition counselling and F2F visit at study entry with the study interventionist, study newsletters at 2-mo intervals providing general information about pregnancy-related issues |

1 × individualised F2F visit and 3 x (10–15 min) follow up telephone call, provided with scales, food records, pedometers and received weekly postcards Delivered by: Dietitian |

Achieve recommended GWG, PA and healthy eating (decrease intake high fat foods) | NA | Academic and community | Social Learning Theory* |

|

Pollak, et al. 2014 [37] United States |

Pilot RCT |

Mixed (PA + diet) n = 35 |

Text4Baby (free mobile information service, limited number of texts related to healthy eating or PA) |

2 SMS three times a week Delivered by: NA |

Achieve recommended GWG by walking 10,000 steps/day, avoid sweetened drinks, eat at least five fruit and vegetables per day, eliminate fast food intake | 16 | Community | Social Cognitive Theory* |

|

Flynn, et al. 2015 [35] UPBEAT UK |

Pilot RCT |

Mixed (PA + diet) n = 183 |

Standard Antenatal Care |

1 × Individualised F2F visit and 8 × group sessions Delivered by: Study health trainer |

Reduce dietary glycaemic load, saturated fat intake and increase PA | 8 | Clinical and community | Control Theory and Social Cognitive Theory* |

|

Jing, et al. 2015 [55] China |

RCT |

Mixed (PA + diet) n = 262 |

Standard Antenatal Care |

3 × 20 min individualised F2F visits, optional feedback via telephone or smartphone app Delivered by: Graduate student |

Improve pregnant women’s behaviour about dietary intake, PA to lower the frequency of excessive GWG and GDM | 8 | Clinical | Health Belief Model |

|

Flynn, et al. 2016 [50] UPBEAT UK |

RCT |

Mixed (PA + diet) n = 1555 |

Standard Antenatal Care |

1 × individualised F2F and 8 × group sessions Delivered by: Study health trainer |

Reduce dietary glycaemic load and saturated fat and increase PA | 8 | Clinical | Control Theory and Social Cognitive Theory* |

|

Asci and Rathfisch. 2016 [41] Turkey |

RCT |

Mixed (PA + diet) n = 102 |

Standard Antenatal Care |

4 × 1 hr individualised F2F visit Delivered by: Researcher |

Adapting to a healthy lifestyle, developing dietary habits, for recommended GWG | 25 | Family health centre | Pender’s health promotion model |

|

Hillesund, et al. 2016 [52] NFFD Norway |

RCT |

Mixed (PA + diet) n = 606 |

Standard Antenatal Care |

2 × 20 min telephone calls and option cooking class Delivered by: Clinical nutritionist or public health nutrition masters students |

Meal regularity, fruit and vegetable intake, consumption of water (over sugar sweetened beverages, awareness of frequency and portion size of discretionary foods) | 12 | Clinical | NA |

|

Mauriello, et al. 2016 [57] United States |

RCT |

Lifestyle (PA, diet, smoking cessation, stress management) n = 335 |

Standard Antenatal Care |

3 × iPad sessions Delivered by: Healthy pregnancy: step by step iPad delivered intervention |

Smoking cessation and relapse prevention, effective stress management, and consumption of fruits and vegetables |

24 | Clinical | Transtheoretical Model of Behaviour Change* |

|

Tussing-Humphreys, et al. 2016 [62] United States |

Randomized, comparative impact trial |

Mixed (PA + diet) n = 82 |

Parents as Teachers (PAT) control group |

Monthly 90–120 min F2F home visits Delivered by: Community based parent educators |

Not clear (achieve appropriate GWG, improve dietary intake and health behaviours) | 72 | Community | NA |

|

Assaf-Balut, et al. 2017 [43] Spain |

RCT |

Mixed (PA + diet) n = 1000 |

Standard Antenatal Care (Included basic Med diet advice and instructions to restrict consumption of dietary fat provided by Midwives) |

1 × 1 hr group session and 2 individualised F2F visits, provided with EVOO and pistachios Delivered by: Dietitian |

Adherence to Mediterranean style diet including daily consumption of > 40 ml EVOO | 24 | Clinical | NA |

| Bruno, et al. 2017 [45] Italy | RCT |

Mixed (PA + diet) n = 191 |

1 h counselling session and 4 follow ups with dietitian with general advice on diet and PA, and a nutritional booklet according to Italian Guidelines for healthy diet and PA in pregnancy |

1 × 1 hr initial and 4 × follow up individualised F2F sessions Delivered by: Dietitian |

Avoid high GI foods, reduce high saturated fat foods, increase low GI vegetable, and fruit consumption, total intake of 1500 kcal/day | 25 | Clinical | NA |

|

Sewell, et al. 2017 [38] Scotland |

Pilot RCT |

Dietary n = 30 |

Standard Antenatal Care |

1 × 15 min F2F and 3 follow up telephone calls, provided with shopping voucher to purchase EVOO Delivered by: Dietitian or researcher |

Adherence to Mediterranean style diet | 26 | Clinical | NA |

|

Simmons, et al. 2017 [64] DALI 9 European countries (UK, Ireland, Netherlands, Austria, Poland, Italy, Spain, Denmark, Belgium) |

RCT (four arm) |

Mixed (PA + diet) n = 436 |

Standard Antenatal Care |

5 X 30–45 min individualised F2F visits, ≤ 4 x ≤ 20 min telephone calls Delivered by: Lifestyle coach |

Improve diet quality (replace sugar sweetened beverages, eat more vegetables, increase fibre, watch portion size, eat protein, reduce fat intake, eat less CHO), increase PA | 18 | Clinical & community | Health Action process approach |

|

Wilcox, et al. 2017 [39] txt4two Australia |

Pilot RCT |

Mixed (PA + diet) n = 100 |

Standard Antenatal Care (including brochure with diet and PA advice) |

1 × individualised F2F visit, 4–5 tailored SMS per week, assess to study website with short videos and social media page Delivered by: SMS, videos by Dietitian/ obstetrician + researcher |

Promote healthy diet (increase fruit and vegetable intake, decrease discretionary foods and sugar sweetened beverages), PA and GWG | 26 | Clinical and community | Social Cognitive Theory* |

|

Asiabar, et al. 2018 [42] Iran |

RCT (three arm) |

Dietary n = 150 |

Standard Antenatal Care |

2 × 90 min individualised F2F visit with partners and 3–5 × text messages Delivered by: Trained midwife |

Improve diet quality: decrease intake of energy dense food and high fat foods by replacing with low fat and or sugar substitutes and increase fruit, vegetables, and dairy, improve fat quality, and recommended serving sizes | 5 | Clinical | NA |

|

Rönö, et al. 2018 [60] Finland |

RCT |

Mixed (PA + diet) n = 293 |

Standard Antenatal Care (included leaflets on healthy diet and PA) |

Individualised F2F visits every 3 months prior to and during pregnancy, and 4 × 1 hr F2F group (enrolment, 1st trimester pregnancy, 6 and 12 months PP) Delivered by: Dietitian and study nurse |

Achieve total energy intake 1600–1800 kcal/day, with total energy intake coming from 40–50% carbohydrates, 30–40% fats and 20–25% protein. Increase intake of vegetables, legumes, fruits and berries, wholegrains and fibre, low-fat dairy and vegetable fats | 22 | Clinical | NA |

|

Van Horn, et al. 2018 [63] MOMFIT United States |

RCT |

Mixed (PA + diet) n = 281 |

Standard Antenatal Care (including asses to MOMFIT website and biweekly e-newsletters) |

3 individualised F2F visits, 6 × 30 min group sessions, 9 × coaching calls, emails, SMS, access to MOMFIT website, and access to LOSEIT Delivered by: Dietitian |

Achieve recommended GWG through healthier diet (adherence to modified DASH diet), increased PA, and increased sleep | 20 | Clinical and community | NA |

|

Günther, et al. 2019 [68] Gelis Germany |

Cluster RCT |

Mixed (PA + diet) n = 2102 |

Standard Antenatal Care |

4 × 30–45 min individualised F2F (3 during pregnancy) Delivered by: Midwives, gynaecologists, or medical personnel |

General healthy eating, according to the “Healthy Start-young family network” for recommended GWG | 34 | Clinical | NA |

|

Buckingham-Schutt, et al. 2019 [46] United States |

RCT |

Mixed (PA + diet) n = 56 |

Standard Antenatal Care (received IOM chart of GWG) |

Minimum 6 × 15–30 min individualised F2F visits, weekly emails and wearable fitness tracker Delivered by: Dietitian |

Increasing PA and modifying carbohydrate intake, for recommended GWG (IOM guidelines) | 26 | Clinical | Self Determination Theory* |

|

Rissel, et al. 2019 [70] Australia |

Cluster RCT |

Mixed (PA + diet) n = 326 |

1 × 20–30 min information only telephone call on GWG and provided with written resources on healthy eating, GWG and PA |

Up to 10 health coaching calls (8 in pregnancy), journey booklet and written resources Delivered by: Dietitian or exercise physiologist |

Achieve recommended GWG | 24 | Clinical, community (phone) | NA |

|

Wattar, et al. 2019 [65] ESTEEM UK |

RCT |

Dietary n = 1252 |

Standard Antenatal Care (Including dietary advice as per UK national recommendations for antenatal care and weight management in pregnancy) |

1 × individualised F2F visits, 2 × group sessions and 2 × telephone calls, provided with EVOO and mixed nuts Delivered by: Dietitian and researchers |

Adherence to a Mediterranean style diet | 14 | Clinical | NA |

|

Adam, et al. 2020 [40] Finland |

RCT (three arm) |

Mixed (PA + diet) n = 78 |

Standard Antenatal Care |

2 individualised F2F visits and 2 × Supportive telephone calls Delivered by: Dietitian trained in healthy conversation skills |

Adopt and maintain healthy behaviours, for recommended GWG | 18 | University | NA |

|

Bianchi, et al 2020 [44] France |

RCT |

Dietary n = 80 |

1 × 30–45 min F2F appointment; 2 × 30 min telephone call, 3 × emails. Generic advice provided as per French Institute for Health Promotion and Health Education |

1 × 30–45 min individualised F2F visit and 2 × telephone calls providing computer based tailored dietary counselling program, followed by 3 × email summaries and 3 × email reminders Delivered by: Dietitian |

Improve nutrient adequacy (PANDiet) | 12 | Clinical | NA |

|

Huang, et al 2020 [36] Australia |

Pilot RCT |

Mixed (PA + diet) n = 57 |

Standard Antenatal Care |

Web based program, 1 × individualised F2F and weekly SMS Delivered by: Dietitian |

Dietary education on low glycaemic index, low saturated fat, increased omega- 3 fatty acids, increased fibre, healthy portion sizes and take out options and snack substitution to achieve recommended GWG | 12 | Clinical | NA |

|

Melero, et al. 2020 [58] St Carlos Spain |

RCT (three arm) |

Diet n = 285 |

2 × F2F visits (advised to restrict fat intake, limit EVOO to 40 ml/day, and < 3 day/week nuts) |

1 × initial individualised F2F visit and 1 × 2 hr follow up F2F visit, provided with EVOO and pistachios Delivered by: Dietitian |

Increase adherence to Med diet and increase EVOO consumption to ≥ 40 ml/day and handful of pistachios ≥ 3 days/week | 28 | Clinical | NA |

|

Crovetto, et al. 2021 [47] IMPACT- BCN Spain |

RCT (three arm) |

Diet OR stress reduction program n = 1221 |

Standard Antenatal Care |

1 hr monthly Individualised F2F visit, 1 hr monthly group session, monthly telephone calls and provided with EVOO and walnuts Delivered by: Dietitian |

Adherence to a Mediterranean style diet | 17 | Clinical | NA |

|

Dawson, et al. 2021 [48] Australia |

RCT |

Diet n = 45 |

Standard Antenatal Care |

1 × half day F2F group and 2 × follow up telephone calls Delivered by: Nutritionist/ researcher |

Eating for the gut microbiota (improve diet quality) | 10 | Academic (Food and Mood Centre) | Theory of Constructive Alignment |

|

Sandborg, et al. 2021 [61] Sweden |

RCT |

Mixed (PA + diet) n = 305 |

Standard Antenatal Care (including optional lecture on a healthy lifestyle) |

HealthyMoms App Delivered by: App |

Healthy diet and PA in alignment with Nordic nutrition recommendations to achieve recommended GWG | 26 | Online (app) | Social Cognitive Theory* |

|

Simpson, et al. 2021 [71], [72] HELP UK |

Cluster RCT |

Mixed (PA + diet) 20 sites n = 614 |

Standard Antenatal Care (including leaflets on healthy eating and PA) |

Weekly 1.5 hr group (until 6 weeks PP) and 2 × telephone calls 3- and 6-weeks PP Delivered by: Midwife or slimming world consultant |

Enhance motivation and equip women with knowledge and skills to make healthier choices and manage their weight during pregnancy and PP |

36 | Clinical | Control Theory and Social Cognitive Theory* |

|

Zhao, et al. 2022 [67] China |

RCT |

Mixed (PA + diet) n = 560 |

3 × Individualised, with Mediterranean style diet but restrict dietary fats |

3 × individualised F2F visits Delivered by: Dietitian |

Adherence to Mediterranean style diet and consume ≥ 40 ml EVOO and 25–30 g pistachios daily | 26 | Clinical | NA |

Where intervention includes three arms most active and least active groups are reported. Only dietary interventions have been extracted

RCT Randomised control trial, EVOO Extra Virgin Olive Oil, PA Physical activity, GI Glycemic Index, hr hour, SMS Short messaging Service, F2F Face to face, PP Postpartum

Twenty-nine studies described their control as receiving standard antenatal care. The definition of standard care varied: they either provided no additional information [35, 36, 38, 40–42, 47–52, 54, 55, 57, 64, 68, 69]; provided additional information on diet (n = 2) [43, 65], diet and physical activity (n = 6) [39, 53, 60, 61, 66, 71], or GWG (n = 1) [46]; provided access to an educational website with biweekly newsletters with pregnancy and infant care materials (n = 1) [63]; or provided standard nutrition counselling accompanied by study newsletters containing general information on pregnancy related issues (n = 1) [59]. Eight studies described their control group as receiving another intervention which included: the same intervention structure providing generic (not tailored) advice (n = 3) [44, 45, 58], less intensive dietary interventions (n = 4) [37, 56, 62], different dietary recommendations (n = 1) [67] or less intensive and generic information provision (n = 1) [70].

Population characteristics

Five studies included pregnant women with a pre-pregnancy BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 [37, 39, 45, 49, 63], six included women with a pre-pregnancy BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 [35, 50, 51, 60, 64, 71] and one study included women with a pre-pregnancy BMI 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2 [44]. Two studies enrolled only nulliparous women [42, 52] and one study only included women with at least one risk factor for GDM [69].

Intervention characteristics

On average, intervention duration was 20 weeks with initiation in the second trimester of pregnancy: at 15 weeks. Intervention initiation ranged from 8 weeks [41] to 26 weeks [48]. Almost three-quarters (71%, n = 27) of the interventions were shorter than 25 weeks, ranging from 5 to 72 weeks, with five studies including an intervention component postpartum [60, 62, 68, 70]. Twenty-seven studies were delivered in the clinical setting through public or private antenatal care [36, 38, 42–47, 49–52, 54, 55, 57, 58, 60, 65–69, 71]. Interventions were delivered in-person (n = 14) [41, 43, 45, 51–53, 56, 58, 60, 62, 66–69], via telephone calls only (n = 1) [70], via text messages (n = 1) [37], via mobile application (n = 3) [54, 57, 61], or through a different combination of these modalities (n = 18) [35, 36, 38–40, 42, 44, 46–50, 52, 55, 63–65, 71].

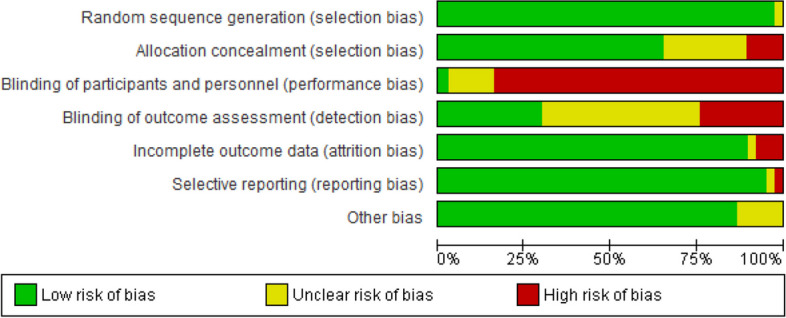

Risk of bias assessment

None of the studies received a low risk of bias in all the areas assessed (Fig. 2). Six RCTs were judged to have only one high risk of bias across all the assessed areas [47, 52, 53, 58, 64, 65]. All studies received an unclear or high risk of performance bias, which is an inherent limitation of dietary behaviour change studies [28]. Over one third of studies (n = 13; 35%) had an unclear to high risk of selection bias, with the majority of these being unclear due to a lack of reporting on how sequence allocation was concealed [35, 37, 42, 44, 46, 51, 55, 59, 62, 68–71]. Conversely, 97% of the studies received a low risk of bias in random sequence generation, with only one study receiving an unclear rating due to a lack of clarity on how participants were allocated to intervention or control groups [37]. Of the included studies, three received a high risk of attrition bias (attrition ranging from 30 to 77%) [57, 66, 70], and one study received an unclear risk of attrition bias [57, 63, 66, 70]. Five studies did not report conflicting interests and were given an unclear risk of bias in the ‘other’ category [51, 56, 57, 67, 70]. One study received a high risk of bias across four categories [71].

Fig. 2.

Risk of Bias graph: review author’s judgement about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across included studies

Interventions effectiveness on dietary intake

A wide variety of tools were used to measure dietary outcomes, the most common was a Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) (n = 20) [35, 37–39, 43, 45, 48–50, 52, 54–56, 58, 59, 67–71] of which two FFQs have been validated for use in pregnancy [73, 74] and were used in two studies [49, 60]. The next most common measures were diet diaries (n = 5) [36, 41, 44, 51, 53], 24 h diet recalls (n = 3) [61–63], a combination of FFQ and diet diaries (n = 3) [60, 64], diet histories or checklist (n = 3) [10, 40, 67], a combination of FFQ and diet recalls (n = 3) [42, 47, 65], or weighed food records (n = 1) [46]. The method used to capture dietary outcomes was unclear in one study [57]. Six studies reported using tools specifically validated for pregnancy [43, 44, 46, 49, 58, 60]. Dietary data was presented differently across the studies including in serves/day, grams/day, cups/day, and a-priori dietary quality scores (with the most common including the Healthy Eating Index (HEI) scores 2005, HEI-2010, Swedish HEI, nutrition score, and the Mediterranean diet score). Eighty-nine percent (n = 33) reported dietary intake in the third trimester of pregnancy (28 + weeks gestation).

Dietary quality was significantly higher for pregnant women receiving dietary intervention, compared to pregnant women receiving control (16 trials, 7,829 participants in aggregate, SMD 0.49, 95% CI 0.23, 0.75, p = 0.0002), although heterogeneity was very high (I2 = 98%, Q = 393.7, Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Dietary intervention verse control: impact on dietary quality

HEI scores were significantly higher for participants receiving dietary intervention, compared to control participants (6 trials, 4337 participants, SMD 0.22, 95% CI 0.16,0.28, p < 0.00001) and heterogeneity was low (I2 = 0%, Q = 1.3). Mediterranean diet score was significantly higher for participants receiving dietary intervention, compared to those receiving control (6 trials, 2,818 participants, SMD 1.05, 95% CI 0.59,1.51 p < 0.00001), however heterogeneity was very high (I2 = 97%, Q = 145.93). Nutrition scores were significantly higher for participants receiving the dietary intervention, compared to those receiving control (3 trials, 1,634 participants, SMD 0.63, 95% CI 0.32, 0.94, p < 0.00001) and heterogeneity was high (I2 = 88%, Q = 17.12).

A significant between group difference was observed for vegetable intake (15 trials, 5915 participants, SMD 0.22 95% CI 0.13,0.31, p < 0.00001, I2 = 52%), fruit intake (14 trials, 5727 participants, SMD 0.15 95% CI 0.05, 0.24, p = 0.002, I2 = 55%) and dairy intake (6 trials, 4,359 participants, SMD 0.23 95% CI 0.03, 0.43, p = 0.03, I2 = 55%) with higher intakes observed in intervention groups. Due to insufficient data and high heterogeneity in the components that composed these food groups across studies, we were unable to pool the studies reporting the effect of the interventions on intake of meat and alternatives, grains and cereals, and discretionary foods.

Sensitivity analysis excluding studies with three or more high risk of bias scores had little effect on effect sizes. Sensitivity analysis excluding studies that only included women with a pre-pregnancy BMI between 25–29.9 kg/m2 or ≥ 30 kg/m2 significantly reduced heterogeneity for both vegetable (I2 = 52% to I2= 29%) and fruit intake (I2 = 55% to I2= 0%).

Behaviour change techniques

Inter-rater agreement on BCT implementation was 0.72 (Cohen’s kappa). As shown in Table 3, 46 of the available 93 BCTs (49.5%) were used in the studies. Eleven (11.9%) were only used once, with 35 being used between two [54, 70] and 29 [48] times (Median 9, IQR 8–13). Two categories (Goals and planning and Social support) had all BCTs used (n = 9 and n = 3, respectively). An additional four categories (Feedback and monitoring, Self-belief, Comparison of behaviour, and Comparison of outcomes) had over two-thirds of their BCTs used (85.7% (n = 6/7), 75% (n = ¾), 66.7% (n = 2/3), and 66.7% (n = 2/3), respectively). None of the 10 BCTs from the category Scheduled consequences were used in any study. The most common category used was Social support (89%, n = 33 studies), followed by Goals and planning (84%, n = 31 studies) and Comparison of outcomes (84%, n = 31 studies). Individually, the BCTs most used were ‘Social support (unspecified)’ (3.1) (81%, n = 30 studies), ‘Credible source’ (9.1) (78%, n = 29 studies) and ‘Instruction on how to perform a behaviour’ (4.1) (76%, n = 26 studies). The studies that reported the highest number of BCTs used are those that specified which BCTs they had included according to either the BCTTv1 (n = 29) [48] or the CALO-RE taxonomy (n = 20) [62].

Table 3.

Behaviour Change Techniques present in the intervention group of dietary interventions of pregnancy

| BCT Category | BCT No | BCT Label | Intervention | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | Total | |||

| Goals and planning | 1.1 | Goal setting (behaviour) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 25 | ||||||||||||

| 1.2 | Problem solving | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 16 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1.3 | Goal setting (outcome) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 16 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1.4 | Action planning | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 21 | |||||||||||||||||

| 1.5 | Review behaviour goal(s) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 16 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1.6 | Discrepancy between current behaviour and goal | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 10 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1.7 | Review outcome goal(s) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1.8 | Behavioural contract | ✓ | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1.9 | Commitment | ✓ | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Feedback and monitoring | 2.1 | Monitoring of behaviour by others without feedback | ✓ | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2.2 | Feedback on behaviour | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 16 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2.3 | Self-monitoring of behaviour | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 16 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2.4 | Self-monitoring of outcome(s) of behaviour | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 9 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2.5 | Monitoring outcome(s) of behaviour by others without feedback | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2.7 | Feedback on outcome(s) of behaviour | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 14 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Social support | 3.1 | Social support (unspecified) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 30 | |||||||

| 3.2 | Social support (practical) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 17 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 3.3 | Social support (emotional) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shaping knowledge | 4.1 | Instruction on how to perform a behaviour | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 28 | |||||||||

| Natural consequences | 5.1 | Information about health consequences | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 11 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5.6 | Information about emotional consequences | ✓ | ✓ | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Comparison of behaviour | 6.1 | Demonstration of the behaviour | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6.2 | Social comparison | ✓ | ✓ | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Associations | 7.1 | Prompts/cues | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 9 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Repetition and substitution | 8.1 | Behavioural practice/ rehearsal | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8.2 | Behaviour substitution | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 9 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8.3 | Habit formation | ✓ | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8.4 | Habit reversal | ✓ | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8.7 | Graded tasks | ✓ | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Comparison of outcomes | 9.1 | Credible source | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 29 | ||||||||

| 9.2 | Pros and cons | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reward and threat | 10.1 | Material incentive (behaviour) | ✓ | ✓ | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10.3 | Non-specific reward | ✓ | ✓ | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10.4 | Social reward | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10.6 | Non-specific incentive | ✓ | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10.7 | Self-incentive | ✓ | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10.9 | Self-reward | ✓ | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Regulation | 11.2 | Reduce negative emotions | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Antecedents | 12.1 | Restructuring the physical environment | ✓ | ✓ | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12.5 | Adding objects to the environment | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 19 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Identity | 13.1 | Identification of self as role model | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13.2 | Framing/reframing | ✓ | ✓ | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Self-belief | 15.1 | Verbal persuasion about capability | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15.3 | Focus on past success | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15.4 | Self-talk | ✓ | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covert learning | 16.2 | Imaginary reward | ✓ | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total | 9 | 13 | 10 | 8 | 12 | 7 | 11 | 13 | 29 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 13 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 14 | 10 | 9 | 6 | 11 | 8 | 2 | 5 | 14 | 10 | 19 | 18 | 11 | 16 | 8 | 9 | 20 | 6 | 380 | ||

Behaviour change techniques identified in included interventions. Behaviour change techniques (BCT) were identified using Behaviour Change Taxonomy Version 1. A BCT is defined as ‘systematic procedure included as an active component of an intervention designed to change behaviour’ [21]

Studies are listed in alphabetical order: 1, [40]; 2, [41]; 3, [42];4, [43];5, [44] α; 6, [45]; 7, [46], 8, [47]*; 9, [48] α; 10, [49]*; 11, [35]*; 12, [50]*; 13, [51]*; 14, [68]; 15, [52]*; 16, [36]α; 17, [53]; 18, [54]*; 19, [55]; 20, [56]; 21, [69]*; 22, [57]; 23, [58]; 24, [59]; 25, [37]; 26, [70]; 27, [60]; 28, [61]*; 29, [38]; 30, [64]*; 31, [72]*; 32, [62]; 33, [63]; 34, [65]*; 35, [66]α; 36, [39]α; 37, [67]

*BCTs were extracted from protocol paper or supplementary material

αRepresents papers that have defined some or all of the BCTs used in the intervention using CALORE or BCTv1

Interventions using BCTs from the Reward and threat category were associated with greater vegetable intake (4 trials, 1,048 participants, SMD 0.38 95%CI 0.21,0.55) and a higher dietary quality, (2 trials, 730 participants, SMD 1.43, 95%CI 0.44,2.42), compared to interventions that did not include any BCTs from this category (vegetable: 11 trials, 4,867 participants, SMD 0.16 95%CI 0.09–0.23, p = 0.02; and dietary quality: 14 trials, 7,101; SMD 0.38 95%CI 0.20–0.56, p = 0.04). Importantly, no BCTs were coded that constituted Threats within this category.

Interventions that included the BCT ‘Action planning’ (1.4) from Goals and planning were significantly associated with a higher dietary quality score (10 trials, 4,826 participants, SMD 0.65 95%CI 0.25–1.04, p = 0.03), compared with interventions that did not include this BCT (6 trials, 3,003, SMD 0.21 95%CI 0.14- 0.29).

Conversely, interventions that did not include the BCT ‘Discrepancy between current behaviour and goal’ (1.6) (10 trials, 5,489 participants, SMD 0.66 CI 0.30–1.01) from Goals and planning were associated with a higher dietary quality compared with interventions that did include it (6 trials, 2,340 participants, SMD 0.18 CI 0.02–0.035, p = 0.02). Interventions that did not include the BCT ‘Feedback on behaviour’ (2.2) from the category Feedback and monitoring (8 trials, 2,892 participants, SMD 0.32 95% CI 0.17–0.47) were significantly associated with a greater vegetable intake compared with interventions that did include it (7 trials, 3,023 participants, SMD 0.14 95% CI 0.07–0.21). Effect sizes for BCT categories and individual BCTs can be seen in supplementary file 2.

Intervention features

Data were sufficient to subgroup studies by the professional who delivered the intervention. In studies where the dietary intervention was delivered by a nutrition professional, the difference between the groups receiving the intervention and the control in their dietary quality scores was significant (13 trials, 5,624 participants, SMD 0.57 95% 0.25, 0.88, p = 0.0005, I2 = 96%, Fig. 4). In studies where the dietary intervention was delivered by other health professionals (midwives, nurses, gynaecologists), research staff, and application-delivered interventions, the difference in dietary quality scores between the groups receiving the dietary interventions and those in the control group was still significant but smaller (3 trials, 2,205 participants, SMD 0.20 95% CI 0.11, 0.28, p < 0.00001, I2 = 0%, Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Impact of the dietary intervention versus control on dietary quality: subgrouped by personnel delivering the intervention (nutrition professional, other)

In studies where the dietary intervention delivery included group sessions, the difference between groups receiving the intervention and the control across all measures of dietary intake was significant, including dietary scores (5 trials, 2,287 participants, SMD 0.97 95% CI 0.41, 1.53, p = 0.0007, I2 = 97%), fruit intake (3 trials, 1,002 participants, SMD 0.33 95% CI 0.20,0.45, p < 0.00001, I2 = 0%), and vegetable intake (3 trials, 1,005 participants, SMD 0.43 95% CI 0.31, 0.56, p < 0.00001, I2 = 0%). In studies where the intervention did not include group sessions the difference between intervention and control groups was no longer significant for fruit intake (11 trials, 4,724 participants, SMD 0.09 95% CI −0.00, 0.19, p = 0.05, I2 = 44%) and was significantly smaller for dietary scores (11 trials, 5,542 participants, SMD 0.28 95% CI 0.14, 0.43, p < 0.0001, I2 = 77%) and vegetable intake (12 trials, 4910 participants, SMD 0.15 95% CI0.09, 0.21, p < 0.0001). This was also observed in studies where the intervention was delivered through a combination of group (online or face-to-face) and individualised delivery for dietary quality scores (5 trials, 2,287 participants, SMD 0.97 95% CI 0.41, 1.53, p = 0.0007, I2 = 97%), independent of individualised session delivery mode. In studies where the dietary intervention was delivered through other modalities such as individual face-to-face alone, group sessions alone, or those delivered by application or text message, the difference between the groups receiving the dietary interventions and those in the control group was still significant but significantly smaller (11 trials, 5,542 participants, SMD 0.28 95% CI 0.14, 0.43, p < 0.0001, I2 = 77%). No impact on effectiveness was seen from all other intervention characteristics including the mention of the underlying theory, the number of included BCTs, other forms of intervention delivery (individualised, individualised face to face, individual face-to-face only), frequency of intervention delivery, setting, or duration.

Secondary outcomes

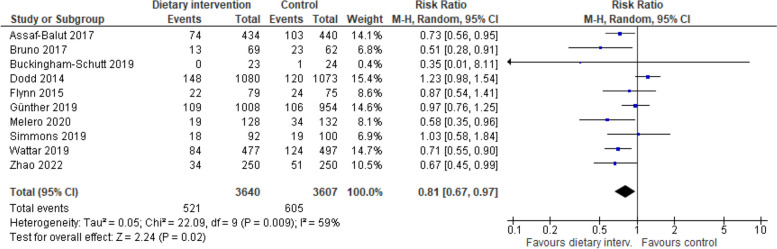

Ten studies reported on GDM incidence diagnosed according to IADPSG criteria and were meta-analysed. Compared with the control group, the incidence of GDM was significantly lower in dietary intervention groups (10 trials, 7,247 participants, RR 0.81 95% CI:0.67,0.97, p = 0.02, I2 = 59%, Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Impact of included interventions on GDM incidence, diagnosed according to IADPSG criteria

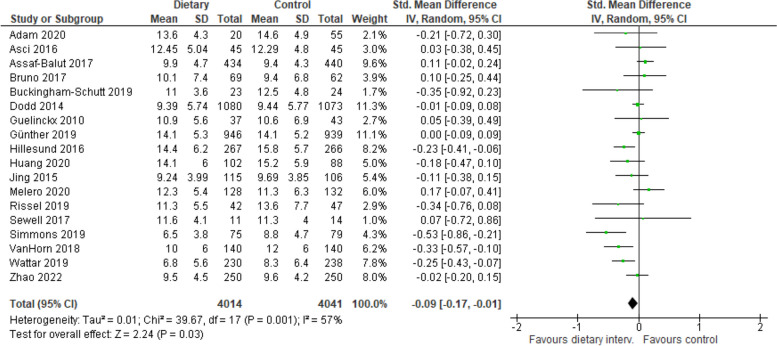

Eighteen studies reported on GWG according to IOM criteria and were combined in a meta-analysis. GWG was significantly reduced among those in the dietary intervention group compared with those in the control group (e.g., receiving standard antenatal care, generic advice, and a tailored intervention aimed at restricting fat intake [58, 67]) (18 trials, 8,055 participants, SMD −0.09 95% CI: −0.17 to −0.01, p = 0.03, Fig. 6). Heterogeneity was moderate for both GDM and GWG (I2 = 62% and I2 = 59%, respectively). Eighty percent of studies that reported on GWG and GDM incidence were mixed interventions (combining both physical activity and diet interventions). Eight studies reported on dietary intake postpartum, despite 16 interventions with postpartum follow up [48, 49, 57, 59, 60, 62, 68, 71]. Due to high heterogeneity in dietary measures and timeframes the BCTs used to sustain dietary change postpartum were unable to be meta-analysed.

Fig. 6.

Impact of included interventions on gestational weight gain (according to Institute of Medicine criteria)

Fidelity and engagement

A diverse range of fidelity measures were reported by a fifth of the included studies (Table 4). These measures included adherence to protocols and random sample reviews. Engagement was measured by tracking participant dropout, session attendance, lost to follow up and those receiving allocated intervention. These engagement measures ranged widely from 0 to 66%. Quantitative usage measures were reported by 68% of included studies, with studies using biomarkers (e.g., urinary hydroxytyrosol) to assess dietary adherence, while others relied on self-reported measures like satisfaction surveys and dietary implementation reports. Table 4 summarises fidelity and engagement measures used.

Table 4.

Fidelity and engagement measures used in included studies

| Author, Year | Fidelity measure | Training provided | Engagement measure | Engagement rate Intervention (control) |

Total % not completed | ITT | Quantitative usage measure | Quantitative result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adam, et al. [40] |

Randomly allocated audio-recordings sessions, semi-structured interviews with intervention dietitian and participants, and participant completion of a modified ‘quality of Prenatal care Questionnaire’ |

Yes | Drop out | 5/40 (4/55) | 38% | No | ||

| Asci and Rathfisch [41] | Lost to follow up | 6/51 (4/51) | 11% | No | ||||

| Asiabar, et al. [42] | Discontinued | 5/50 (7/50) | 16% | |||||

| Assaf-Balut, et al. [43] | Lost to follow up | 66/500 (60/500) | 13% | Yes | MED Diet Score, Urinary Hydroxytyrosol levels (marker of EVOO compliance) and serum γ-tocopherol levels (marker of pistachio compliance) at 24–28 GW in 10% of participants | |||

| Bianchi, et al. [44] | Lost to follow up | 0/40 (2/40) | 3% | No |

Read booklet Women’s report of implementing dietary advice |

< 5% did not read booklet in intervention and control groups; 29% in control read booklet 5 + times Intervention group largely reported implemented dietary advice (5.7 (1.4)/9) |

||

| Bruno, et al. [45] | Lost to follow up | 27/96 (33/95) | 31% | No | Missed follow up visits | 3% of women in intervention missed one follow up vs 15% of control | ||

| Buckingham-Schutt, et al. [46] | Received allocated intervention | 25/27 (26/29) | 16% | No | Number of sessions received by intervention group | All participants in intervention received ≥ 6 sessions. Average attendance was 6.8 ± 0.7 sessions | ||

| Crovetto, et al. [47] | Attendance of baseline and final visit | 89.3% | 3% | Yes |

Blood sample and urine aliquots demonstrating intake of EVOO and nuts (α- linolenic acid and hydroxytyrosol) Mean session attendance adherence to MedDiet |

Significant increase in blood and urinary biomarkers Mean session attendance was 1.8 (1.2) by 38% of participants High adherence to MedDiet observed in 62% of participants, as defined by an improvement of 3 points in final MED diet score |

||

| Dawson, et al. [48] | Received intervention | 22/23 (22/22) | 4% | No | ||||

| Dodd, et al. [49] | Yes | 15% | Yes | |||||

| Flynn, et al. [35] | 16% | No | Attendance at group | 82 (88% attended at least one group, 60 (64%) attended four or more | ||||

| Flynn, et al. [50] | 2% | Yes | ||||||

| Günther, et al. [68] | 87% of monitored sessions used presenter binder with specific counselling content, 70% of cases all predefined counselling content discussed | Yes | Dropout prior to primary analysis | 82/1139 (76/1122) | 9% | No | Attendance | 88% attended all sessions; 3% did not attend any sessions |

| Guelinckx, et al. [51] | Dropout | 0/65 (2/65) | 35% | No | ||||

| Hillesund, et al. [52] | Attrition | 28 /303 (26 /303) | 16% | No | Attendance | 90% received both sessions, 9% received one, 1% received none | ||

| Huang, et al. [36] |

Retention to birth Withdrew |

63% (67%) 23% (25%) |

26% | Yes | Attendance | 90% of all scheduled appointments were attended. 75% at 28GW appointment; 87% attendance at 36GW appointment and 92% at 3-month appointment | ||

| Hui, et al. [53] | Lost to follow up | 6/112 (13/112) | 15% | No | ||||

| Jackson, et al. [54] | Lost to follow up | 24/158 (10/163) | 10% | Yes | Satisfaction | 98% intervention group reported they liked the program overall; 27% of intervention vs 4%of control felt it was too long | ||

| Jing, et al. [55] | Loss to follow up | 2/131 (9/131) | 16% | No | ||||

| Kieffer, et al. [56] | Yes | Did not complete follow up | 22/139 (18/139) | 14% | Yes | Attendance | 98% of intervention participants attended 1 meeting and 12% attended all 11 meetings. Of control, 85% attended 1 meeting and 13% attended all 3 meetings | |

| Kinnunen, et al. [69] | FFQ data available at 36-37GW | 74% (80%) | 10% | No | ||||

| Mauriello, et al. [57] | Retention to third trimester | 69% (73%) | 29% | No | Completion of all three intervention sessions | 70% | ||

| Melero, et al. [58] | Lost to follow up | 15/142 (10/142) | 9% | No | Adherence to MedDiet (defined by MEDAS score) | Significantly higher in intervention group at 24-28GW and 36-38GW in intervention compared to control (p = 0.001, 0.034, respectively) | ||

| Phelan, et al. [59] | Lost to follow up | 36/201 (34/200) | 5% | Yes | Completed 12-month postpartum assessment | 80% intervention and 78% control | ||

| Pollak, et al. [37] | Completion rate | 14/23 (9/12) | 34% | Yes | Read and response to text messages | 86% responded to texts; 86% reported reading the texts | ||

| Rönö, et al. [60] | Yes | Lost to follow up | 6/249 (7/243) | 8% | No | Completion of food diaries | 63% of intervention and 59.3% of control completed baseline and follow up food diaries | |

| Rissel, et al. [70] | Duration of phone calls was in line with protocol | Withdrawals | 440/482 (395/441) | 66% | No | Received all calls during pregnancy | 64% received all 8 calls | |

| Sandborg, et al. [61] | NA | Lost to follow up | 18/152 (16/153) | 0% in imputed analysis (11% complete analysis) | Yes | App usage and satisfaction |

83% reported using the app at least once/week; Dietary registration used 0.2 (SD 0.3) times/week; 77.6% (104/134) fully or largely agreed they were satisfied with the app |

|

| Sewell, et al. [38] | Used an agreed protocol and booklet for consistency | Lost to follow up | 2/14 (0/16) | 7% | Completion of trial |

93% Qualitative evaluation via interviews (n = 9) reported the intervention was highly acceptable to interviewees |

||

| Simpson, et al. [71], [72] | Agreement between raters assessing fidelity was 85%. Key intervention components were discussed in 75–100% of observed sessions | Study completion | 70% (85%) | 7% | yes | Attendance |

50% intervention participants attended between 26–100% of available sessions, 27% attended ≤ 25% of sessions, 23% did not attend any sessions Follow-up phone calls completed as planned for 2/3 of participants |

|

| Tussing-Humphreys, et al. [62] | Yes | retention rates | 67% (77%) | 28% | No | Compliance rates for GM 6 and GM 8 visits |

67 and 51% intervention 88 and 84% control |

|

| Van Horn, et al. [63] | A 10% random sample reviewed by trained study personnel for fidelity with a 10-point rubric determined a 100% alignment with criteria | Yes | Lost to follow up | 0/140 (1/141) | 0% | Yes | Weekly weight self-monitoring | 70.1% |

| Simmons, et al. | Yes | Lost to follow up | 10/108 (5/105) | 11% | Yes | |||

| Wattar, et al. [65] | Pre-piloted presentations used in group | Yes | Lost to follow up | 40/593 (27/612) | 9% | Yes | ||

| Wilkinson and McIntyre [66] | Lost to follow up | 65/178 (53/182) | 33% | Yes (and PP) | Received allocated intervention | 47% in intervention group | ||

| Wilcox, et al. [39] | Delivery to protocol was determined and occurred in all but 2 events | Completion | 45/50 (46/50) | Yes | Goal setting and having read booklet |

78% set PA goals, 40% chose weekly goal review text, 38% a weight review text weekly At 3 GW 40/42 participants reported setting regular behaviour change goals. All women reported having read booklet |

||

| Zhao, et al. [67] | Drop out | 30/280 (30/280) | 11% | No | Urinary hydroxytyrosol levels (EVOO biomarker) and serum gamma-tocopherol levels (biomarker of pistachio intake) | Statistically significant increase in intervention group compared with control (p = 0.02, p = 0.03, respectively) |

Fidelity and engagement measures reported in included studies

GW Gestational Weeks, GM Gestational Month, EVOO Extra virgin Olive Oil, SD Standard Deviation, FFQ Food Frequency Questionnaire, PA Physical Activity

aPercentage represents the number of participants randomised who were not included in final data analysis

Discussion

This is the first review to systematically summarise the BCTs used in dietary interventions and to determine the effective components associated with changing and maintaining dietary behaviours in pregnancy. Despite few intervention designers specifying a theory to plan their intervention or specifying the BCTs used, behaviour change interventions in pregnancy were effective at improving dietary intake. The systematic coding of BCTs found that interventions in pregnancy used only half of the available BCTs and the number and type of BCTs varied widely across included interventions. This review identified BCTs more effective at improving dietary behaviours than others. Further, interventions delivered by a nutrition professional and those that included group delivery were associated with more favourable dietary behaviours compared with other professions and other delivery modalities. In line with other reviews [24, 75], high heterogeneity was observed in included behavioural interventions regarding intervention characteristics and reported dietary outcome measures.

In this review, we found that the categories most frequently applied in dietary interventions during pregnancy were Social support, Goals and planning, and Feedback and monitoring. These findings are consistent with behaviour change interventions across various other population groups and intervention types, including nutrition intervention in adults post bariatric surgery [76], interventions to increase alignment with Mediterranean dietary principles in older adults [77], diet and physical activity interventions in adults with type 2 diabetes [78], and for physical activity promotion and maintenance during pregnancy [79]. Goal setting, feedback and monitoring and social support have been proposed to contribute to behaviour change by enhancing self-efficacy [80], a central tenet of social cognitive theory. Social cognitive theory is one of the most applied theories in wider behavioural interventions in the literature [81–83] and accounted for 63% of the theories that underpinned behavioural interventions included in this review. Less than a third of intervention designers delivered programs underpinned by an evidence-based behaviour change theory and less than one-fifth of interventions were designed using specific BCTs [36, 39, 44, 48, 61, 66]. Potentially more common and familiar BCTs are being applied, with intervention designers overlooking other available and more relevant or effective strategies. It may also be that the most applied BCTs are more consistently and clearly reported in intervention descriptions, leading to more frequent coding. Clearer reporting of intervention components to support behaviour change would strengthen the ability to replicate and implement interventions [21]. Effective BCTs could be better and more consistently integrated into interventions by informing intervention design with a theory-driven approach, applying frameworks such as the Theoretical Domains Framework [84] and using the Behaviour Change Wheel/ COM-B model [84].

Reward relates to the anticipation of a direct reward benefit and uses incentives and rewards to motivate a change in behaviour [21] and was significantly associated with higher intake of fruit and vegetables, and high dietary quality scores compared to interventions without this category. This category accounted for only 2% of the applied BCTs, with none in the top 10 most frequently used BCTs, aligning with previous research suggesting this category comprises some of the most underused BCTs [85]. Six of eleven BCTs from this category were used, all constituting BCTs from Rewards, through positive reinforcement of target dietary behaviour, by praising and encouraging women, graduation ceremonies following completion of the program and through gift incentives after attendance at each intervention meeting for mother and baby. Reward underpins the principles of operant conditioning, where beliefs about consequences and social influences drive behaviour [86]. In pregnancy, extrinsic motivators such as social influences and the health of the baby are large influences on maternal behaviour [17]. With suggestions that the inclusion of BCTs from Reward are associated with a higher intervention cost-effectiveness [85], more studies are needed to test and corroborate this finding.

A significant association was observed between the BCT ‘Action planning’ (1.4) from Goals and planning and higher measures of dietary quality, aligning with previous research for its positive impact on Dietary intake [78, 87, 88]. Action planning assists with translating intentions into specific plans to provide a clear roadmap of behaviour change that bridges the action-intention gap. It has been identified as a construct within the Health Action Process Approach and Self-regulation Theory when grouped with other BCTs [89]. Healthcare professionals involved in the delivery of nutrition care should consider the inclusion of ‘Action planning’ (1.4) to improve Dietary intake in pregnancy where appropriate.

Interventions that did not include ‘Discrepancy between current behaviour and goal’(1.6) or ‘Feedback on behaviour’(2.2) were associated with a higher dietary quality and greater vegetable intake. A recent systematic literature review and meta-analysis reported that over twice as many BCTs from Goals and planning and Feedback and monitoring were observed in effective digital interventions during pregnancy for improving diet, physical activity and achieving recommended GWG [90]. This may suggest a potentially additive effect of certain BCTs in pregnancy interventions. BCT effectiveness may depend on the context of the intervention, the intervention provider and the BCTs they are combined with. Michie et al., reported that interventions that combined self-monitoring with one or more techniques pertaining to self-regulation, including ‘Feedback on behaviour’ (2.2) were found to be significantly more effective at increasing healthy eating in adults [24]. Unfortunately, a limited number of reviews combining these BCTs restricted our ability to assess the effect of multiple BCTs on intervention effectiveness.

Consistent with previous studies with pregnant women [91] and adults [83, 92], interventions provided by a nutrition professional and those delivered combining group sessions with individualised care were associated with increased intervention effectiveness. A core competency of dietitians is tailoring dietary advice to patient’s knowledge, needs and preferences to support behaviour change [93]. This supports practice recommendations that women who require nutrition care, such as those with weight gain outside of recommendations, with GDM or poor dietary intake are referred to a dietitian [94]. Furthermore, the addition of group sessions with individual care enhances the development of self-efficacy through the enabling vicarious experience, verbal persuasion and (reduction of arousal of) physiological state; three of the four influences on self-efficacy [80].

This systematic review was rigorous in its scope and search strategy, was reported according to the PRISMA statement and identified a comprehensive collection of relevant RCTs. This study was conducted according to a pre-defined protocol. A strength of this study was the application of an internationally validated taxonomy (BCTTv1) by independent coding from two researchers who had completed online education and certification [21]. This resulted in substantial inter-rater reliability despite poorly described interventions with limited BCT detail.

The findings of this review need to be considered in the context of several limitations. The attribution of BCTs to dietary improvement is exploratory and the results may be biased by the size of the study, the number of studies reporting that BCT and other active features of intervention design. The use of the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool 1 is noted as a limitation as it is not as rigorous as the more updated tool two. Tool 1 was chosen as it allows for the assessment of biases arising from study funding and conflicts of interest. Additionally, findings relating to effective BCTs are likely to be conservative as more BCTs are likely to be effective and potentially even applied in studies. Only two studies explicitly listed all BCTs used in the intervention and control groups [39, 48]; and less than one in five studies [38–40, 63, 68, 70, 71] reported measures of intervention fidelity, with high heterogeneity observed in the measures that were reported. Potential discrepancies exist between features that may have been applied in the intervention compared to what was planned and reported. Future interventions should report intervention features and fidelity using relevant taxonomies and checklists, such as the BCTTv1 and TIDerR checklist [21, 95]. Furthermore, the assessment of certain dietary behaviours (discretionary foods, grains and cereals, and meat and alternatives) was limited by the lack of consistency and high heterogeneity in tools used to assess intake. Additionally, only studies where high diet quality scores reflected improvements in dietary quality were included in the meta-analysis. Studies where a high score indicated reduced diet quality were excluded potentially limiting generalisability. While not a limitation of this review, the lack of overall promotion in interventions of the intake of sufficient grains and cereals during pregnancy is a shortcoming of this area of health promotion as evidenced by low alignment of women’s reported intake and pregnancy dietary guidelines for this food group [11, 41, 55, 59, 61]. Furthermore, we were unable to determine the role of dietary intake in GDM diagnosis and GWG as most included studies reporting on these outcomes provided mixed interventions that combined both diet and physical activity.

Substantial heterogeneity in dietary outcome measures and period of postpartum follow up precluded further meta-analysis into the effectiveness of dietary interventions in pregnancy for achieving longer-term dietary change. Even small changes in dietary behaviours in pregnancy can have substantial effects on population health outcomes, especially if these behaviours can be maintained longer term and into the next pregnancy [96]. More dietary intervention studies are needed that report on long term dietary maintenance to determine effective BCTs during the postpartum period.

Conclusion

Overall, certain features of dietary interventions in pregnancy show promise for enhancing behaviour change, including delivery by a nutrition professional and interventions delivered via a combination of group and individualised care. The category Reward and the individual BCT ‘Action planning’ (1.4) both appear to be integral in supporting behaviour change. Such techniques can be simple and inexpensive to deliver. Health professionals should be trained in integrating effective BCTs into research and routine care. These findings are exploratory and should be experimentally tested through additional interventions that clearly define their component BCTs, intervention characteristics and delivery fidelity. Intervention design should incorporate a theory driven approach, where frameworks such as the Theoretical Domains Framework (85) are used to identify the determinants of dietary behaviours the Behaviour Change Wheel/ COM-B model [84] are used to map to evidenced-based BCTs to overcome barriers to behaviour change with the target population. Evidence for the sustainability of dietary intake change in response to interventions is limited. More research is needed that reports on dietary intake after pregnancy to assist with determining if changes in dietary intake initiated in pregnancy can be maintained post-partum.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Natalie Barker for her assistance with initial search development.

Abbreviations

- BCT

Behaviour Change Techniques

- BCTTv1

BCT taxonomy version 1

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- GWG

Gestational Weight Gain

- GDM

Gestational Diabetes Mellitus

- HEI

Healthy Eating Index

- IADPSG