Abstract

Kawasaki disease (KD), characterized by systematic vasculitis, is a leading cause of pediatric heart disease. Although recent studies have highlighted the critical role of deubiquitinases in vascular pathophysiology, their specific contribution to KD remains largely unknown. Herein, we investigated the function of the deubiquitinase USP7 in both KD patients and a CAWS-induced KD murine model. USP7 expression level is increased both in HCAECs induced by KD sera and cardiac CD31+ endothelial cells of KD mice. Whereas knockout of USP7 increases the cellular proportion of endothelial cells and potentially attenuates the elevated EndoMT, fibrosis, and inflammation in cardiac tissue of KD mice, consistently with the in vitro experiment observed in HCAECs induced by TGF-β2. Mechanistically, USP7 interacts with SMAD2/3, enhancing their protein stability by removing the K48 ubiquitin chain from both proteins and preventing their proteasome degradation, thus increasing the p-SMAD2 levels and nuclear entry. Importantly, intraperitoneal injection of USP7 inhibitor, P22077 elicited a robust anti-EndoMT and anti-vascular inflammation effect in KD model mice. Therefore, our study uncovered a previously unrecognized function of increased USP7 in KD by augmenting TGFβ2/SMAD2/SMAD3 signaling, thus facilitating the transcription of genes implicated in the EndoMT, cardiac fibrosis, and vascular remodeling. Our finding suggests that USP7 could serve as a potential therapeutic target for the prevention and treatment of coronary artery lesions in KD and related vascular diseases.

Keywords: Kawasaki disease, Coronary artery lesions, Endothelial cells, USP7, TGFβ2-SMAD pathway

1. Introduction

Kawasaki disease (KD) is an acute febrile disease and systematic vasculitis of unknown etiology that predominantly affects young children and frequently complicates coronary artery lesions (CALs) or aneurysms (CAAs), which can eventually lead to myocardial infarction, ischemic heart disease, and even death [1–3]. The incidence of KD has markedly increased in recent years, and KD is the leading cause of acquired heart disease among children in developed countries [2,4]. The standard treatment of acute KD is intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) plus aspirin. Although high-dose IVIG plus aspirin and alternative drugs, including etanercept and infliximab, could alleviate inflammation and symptoms and yield beneficial organ-protective effects in KD patients, these treatment approaches cannot completely reverse KD-related vascular injury and cardiovascular adverse events [2], implying that other unknown mechanisms remain to be investigated. Notably, approximately 20 % of KD patients are IVIG resistant, and these types of IVIG-resistant patients has increased recently, thus greatly increasing the risk of developing CALs or CAAs [2,5,6]. Moreover, coronary artery tissue, as one of the main targets of KD-induced damage in organs, undergoes pathological vascular remodeling under various stimuli including inflammation, ultimately leading to endothelial dysfunction and vascular fibrosis, which can persist long after the acute phase [7,8]. Thus, it has been increasingly recognized that KD is not a self-limited disease and is often accompanied by late and long-term cardiovascular complications, including coronary artery lesions, shortening fractions, increased end-systolic and end-diastolic dimension strain abnormalities [9–13], and endothelial dysfunction that even might persist for several years [14–16].

This ultimate pathological event in patients with KD is closely associated with endothelial dysfunction, notably through the process of the endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndoMT). EndoMT represents as a critical pathogenic trigger of endothelial dysfunction, characterized by the progressive transformation of endothelial cells into mesenchymal cells. This transition is frequently accompanied with significant alterations in cellular morphology, function, and molecular expression, thus extensively implicating in various diseases [17]. A hallmark of EndoMT is the reduction in the expression of endothelial-specific proteins coupled with an increase in mesenchymal-like protein expression, which result in remodeling of the arterial wall with myointimal proliferation and stenosis of the arterial lumen [18]. Recently, emerging evidence has demonstrated that inflammation, hypoxia, shear stress, and metabolic products can effectively induce the EndoMT in the vascular endothelium [19,20]. Furthermore, during morphological or functional alternations in endothelial cells, activated EndoMT cells acquire motility and exhibit increased paracellular permeability. This facilitates the recruitment, infiltration, and accumulation of endothelial-derived mesenchymal cells and inflammatory-related immune cells within the arterial intima, which are key features of coronary artery remodeling pathogenesis in patients with KD [7]. Activated endothelial cells further release proinflammatory cytokines that stimulate vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), neutrophils, and macrophages [17,20]. Therefore, the EndoMT is implicated in the proliferation of VSMCs and the recruitment and adhesion of leukocytes to endothelial cells, which jointly aggravate vascular damage. However, although the mechanism and pathological role of the EndoMT in cardiovascular diseases have been broadly recognized [20], the molecular mechanism and pathways regulating the EndoMT during KD pathogenesis remain inadequately understood.

Ubiquitination, as a protein modification characterized by intricate mechanisms and regulated by E3 ubiquitin ligases and deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), is broadly involved in various physiological and pathophysiological processes [21,22]. In the present study, we observed that the ubiquitin–proteasome system is extensively associated with KD pathogenesis by reanalyzing the protein expression profile in the leukocytes of KD patients we published previously [23]. More specifically, we observed an increased expression level of the deubiquitinating enzyme ubiquitin-specific peptidase 7 (USP7) in the leukocytes of KD patients by reanalyzing the protein expression profile of DUBs. Another reason we focused on USP7 is that USP7 has been shown to deubiquitinate NF-κB, thus promoting TNFα-mediated signaling [24], which is a critical therapeutic target of the monoclonal antibody infliximab used to treat KD [2]. Additionally, USP7 is highly expressed in cardiac and myocardial tissues according to the data from the BioGPS database; hence, USP7 is implicated in hypoxia-induced cardiomyocyte injury, ischemia/reperfusion injury [25,26], myocardial injury, and cardiomyocyte proptosis [27]. Moreover, recent research has linked USP7 to various physiological processes, cancer, and cardiovascular diseases [28,29]. Although USP7 imparts a partial epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) state in colorectal cancer by stabilizing DDX3 [30], whether USP7 is involved in the EndoMT and vascular pathophysiology during KD pathogenesis remains unexplored.

In this study, we investigated the effects of USP7 on the EndoMT, fibrosis, and coronary artery remodeling using human KD samples and a KD mouse model with USP7 knockout. USP7 deficiency attenuates the EndoMT both in vivo and in vitro. By screening and validating EndoMT-related proteins potentially regulated by USP7, we revealed that USP7 facilitates the EndoMT by deubiquitinating and stabilizing SMAD2 and SMAD3 in human coronary artery endothelial cells (HCAECs), thereby promoting TGFβ2-induced EndoMT-related genes expression. Moreover, a USP7 inhibitor was administered to KD model mice to examine the cardiac EndoMT, inflammation, and fibrotic changes. Thus, our study revealed that increased USP7 expression in individuals with KD has detrimental effects on the cardiac EndoMT, fibrosis, and coronary artery remodeling. The development and use of USP7 inhibitors could serve as a candidate strategy to treat KD and related vascular diseases.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Human samples

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients and healthy control children are detailed in Supplemental Table S1. The age range for both KD patients and healthy controls was approximately 1–5 years. The healthy control group consisted of children who had undergone routine health examinations and were free from infections. In accordance with the 2017 criteria established by the American Heart Association (AHA) [2], patients were diagnosed with KD based on a fever lasting between 4 and 7 days and the presence of at least four of five principal clinical symptoms of KD, which included rash, conjunctivitis, oral changes, palmar, plantar erythema, and cervical adenopathy. KD patients are often complicated by CALs, such as dilatation, localized stenosis, segmental stenosis, and aneurysms, as documented by echocardiography [23]. Serum samples from healthy controls, and KD patients with CALs or without CALs were respectively isolated and analyzed. All samples were collected at the Children’s Hospital of Soochow University (Suzhou, Jiangsu Province, China). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Children’s Hospital of Soochow University.

2.2. Induction of a murine model of KD

Male wild-type (C57BL/6J background) and Usp7+/− mice at 4 weeks of age were intraperitoneally injected with a Candida albicans water-soluble (CAWS) complex that was prepared from the C. albicans strain NBRC1385, as described previously [32,33], to mimic KD. Briefly, C. albicans was grown in a C-limited medium for 48 h at 27 °C. Following culture, an equivalent volume of ethanol was added to the culture medium, and the mixture was left to stand overnight, after which the precipitate was collected. This precipitate was subsequently dissolved in distilled water, followed by the addition of ethanol, and the mixture was again allowed to stand overnight. The resulting precipitate was collected and dried using acetone to produce CAWS. The male wild-type and Usp7+/− mice allocated to the PBS and CAWS groups were administrated equal volumes of PBS or CAWS (4 mg per mouse per day) daily for five consecutive days, and regular feeding was continued for 3–60 days. The mice were then sacrificed under anesthesia, and their spleens and hearts were isolated for subsequent experiments. All the experimental procedures and protocols were approved by the Animal Research Ethics Committee of Soochow University (SUDA20220906A01) and were conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.3. USP7 KO mice

Usp7+/− mice on a C57BL/6J background purchased from Cyagen Biosciences Inc. (Suzhou, China) were used to determine the role of USP7 in KD. Heterozygous USP7 mice were bred to produce both heterozygous USP7 knockout mice and their wild-type littermates. Because homozygous USP7 knockout is embryonically lethal in mice [31], heterozygous USP7 knockout and wild-type male sibling mice were used. Four guide RNA sequences (TGATGTGCCACACCTAAGGTTGG, CTCTTCATAATGTTCGGGAGAGG, AGGCTGATGTGCCACACCTAAGG, and TTCATAATGTTCGGGAGAGGAGG) were designed to produce heterozygous knockout mice via the CRISPR/Cas9 technique. All the mice were housed in a specific-pathogen-free environment at the animal experimental center of Soochow University, with a 12 h light/dark cycle, a temperature of 20–25 °C, and a humidity of 60 ± 5 %. The sequences of the primers used to identify Usp7+/− mice are listed in Supplemental Table S2.

2.4. H&E and Elastica van Gieson staining of murine cardiac tissue

For the histological analysis, murine hearts were perfused with PBS, fixed with 10 % formalin, processed conventionally, embedded in paraffin, and cut at 5 μm transversely through the aortic root. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)- and Elastica van Gieson (EvG)-stained sections were prepared by board-certified veterinary pathologists blinded to the grouping. All the sections were investigated by using routine histological techniques and examined for the presence of arteritis by light microscopy. The inflammatory score of murine cardiac tissue was calculated according to the criteria described previously [35].

2.5. Masson’s blue and Sirius red staining

The cardiac slices were dewaxed, rehydrated, and stained with Weigert’s Iron Hematoxylin and Masson’s blue solution according to the manufacturers’ instructions (C0189S, Beyotime, China). Similarly, tissue sections were stained with modified Sirius Red staining kit (G1472, Solarbio, China). The slices were then scanned to measure the area of confluent fibrosis surrounding the coronary arteries using a tissue section digital scanner (3DHISTECH, Panoramic, MIDI) and Case View 2.4 software (3DHISTECH).

2.6. Isolation of cardiac CD31-positive endothelial cells

The heart tissue from the mice in each group was cut into pieces and digested with collagenase. CD31 microbeads (no.130–097–418, Miltenyi, Biotechnology) were used to separate ECs from the tissue homogenates. First, CD31-positive cells were magnetically labeled with CD31 microbeads. Then, the cell suspension was loaded onto a MACS column, which was placed in the magnetic field of a MACS separator. The magnetically labeled CD31-positive cells were retained within the column. After removing the column from the magnetic field, the magnetically retained CD31-positive cells were eluted as the positively selected cell fraction. CD31 microbead-labeled cells were subsequently cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10 % FBS and used for expression analyses.

2.7. Preparation and sequencing of single cells in murine cardiac tissue

ScRNA sequencing of heart tissues from the WT-PBS, WT-CAWS, Usp7+/− PBS, and Usp7+/− CAWS groups was conducted. For each group, fresh heart tissue isolated from two mice was mixed. For each mixed sample prepared for scRNA-seq, the cardiac tissue was digested with an enzyme mixture (0.8 mg/mL pancreatin, 120 unit/mL collagenase, and 1 % antibiotics/antimycotics) at 37 °C. Single cells were encapsulated in droplets using the 10×Genomics platform; this and subsequent procedures were performed by Capital Bio-Technology (Beijing, China). Briefly, every cell and each transcript were barcoded using a unique molecular identifier, and cDNA was prepared using single-cell 3 reagent kits v2 (10×Genomics). The libraries were sequenced using an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 sequencer with a sequencing depth of at least 100,000 reads per cell and paired end reads of 150 bp.

2.8. scRNA sequencing data analysis

The sequencing data were first analyzed using CellRanger software (version 2.9.1). The reads were then aligned to the mouse UCSCmm10 reference genome. The alignment results were used to quantify the expression levels of mouse genes and to generate a gene–barcode matrix. Next, t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE), clustering and comparison analyses were conducted using the Seurat and Monocle packages. A correlation analysis was performed using the corrplot package. The cell types of single cells were annotated using the single R package based on two mouse databases (ImmGenData and MouseR-NAseqData). After the bioinformatic removal of doublets, dead cells, and cell debris, 67,926 cells passed quality control, including 19,434 cells from the WT-PBS group, 19,966 cells from the WT-CAWS group, 14,034 cells from the Usp7+/− PBS group, and 14,492 cells from the Usp7+/CAWS group, which were used for subsequent bioinformatic analyses. Different types of cells were subsequently clustered across samples using the Seurat package and visualized in two-dimensional space. The shared and divergent cell types were revealed using scRNA-seq data from each group by aligning and integrating the datasets using a graph-based and canonical correlation analysis method. The cell clusters among each group were annotated with an R package and rectified with the expression of canonical marker genes.

2.9. Immunofluorescence (IF) staining

Rabbit monoclonal anti-USP7 (1:100, 4833S, CST), rabbit monoclonal anti-CD31 (1:50, ab281583, Abcam), rabbit monoclonal anti-FN1 (1:50, ab268020, Abcam), rabbit monoclonal anti phosphorylated SMAD2(Ser465/467, 1:1000, 18338S, CST) and mouse monoclonal anti-VE-cadherin (1:100, 14–1449–82, Thermo) antibodies were used for the immunofluorescence assays. Immunoreactivity was visualized via an incubation with Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (CST, 1:500) or Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies (CST, 1:500), and the nuclei were counterstained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Fluorescence images were captured with an Olympus FV1000 (IX81) confocal microscope.

2.10. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs)

A human TGFβ2 ELISA Kit (DB250, R&D Systems, USA) and a human TNFα ELISA Kit (E-EL-H0109c, Elabscience, USA) were used in this study. Briefly, 2 μL of human serum was added to 98 μL of dilution buffer and incubated with capture and secondary antibodies according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The color intensity was measured at 450 nm.

2.11. Cell culture and transfection

Human coronary artery endothelial cells (HCAECs) were cultured in endothelial basal medium-2 (EBM-2) supplemented with an EGM-2MV Bullet Kit (CC-3202, Lonza) at 37°C in a humidified 5 % CO2 incubator. Human 293 T cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen) and penicillin–streptomycin (Beyotime, Biotechnology). The cells were transfected with plasmids using jetPRIME (Cat#: 101000046, Polyplus, France) or LongTrans (Cat#: TF07; Ucallm) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Recombinant human TGFβ2 (HZ-1092, Proteintech), cycloheximide (CHX), the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (M7449), and other chemicals were purchased from Sigma.

2.12. DNA plasmids and lentivirus packaging

Recombinant Myc-SMAD2, Myc-SMAD3, Flag-SMAD2, and Flag-SMAD3 plasmids were generated using the pcDNA3.1 plasmid. The Flag-USP7, HA-Ub, and HA-K48-Ub plasmids were gifts from Professor Zheng Hui (Soochow University). USP7 (C223A) and SMAD2 mutant plasmids (K39R, K420R, K156R and K383R) were generated with a Quick-Change Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit from Stratagene (Agilent Technologies Inc., CA). All recombinant lentiviruses were obtained from Genechem Company (Shanghai, China). The packaged lentiviruses were constructed using the hU6-MCS-CBh-gcGFP-IRES-puromycin vector, and the lentivirus targeting USP7 (sh-USP7#1-59527, sh-USP7#2-59528, Sh-USP7#3-59529) and the scrambled control (sh-CON) were used. The USP7-RNAi sequences are listed in Supplemental Table S3.

2.13. RNA isolation and real-time quantitative PCR

Total RNA was isolated from different cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, United States). cDNA was subsequently synthesized with 5 × all-in-one RT master mix (Abm, Canada) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantitative real-time reverse transcription PCR (qRT–PCR) was performed with 2x SYBR Green qPCR master mix (Bimake, United States) and a LightCycler®480 instrument (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). The primer sequences are listed in Supplemental Table S2. The expression levels of each target gene were normalized by subtracting the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) threshold cycle (CT) values; expression levels were normalized using the ΔΔCT comparative method. The results were analyzed from three independent experiments and are presented as the means ± standard deviations (s.d.s).

2.14. Western blotting and antibodies

The cells were lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (RIPA buffer, P0013C; Beyotime, Shanghai, China) supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail from Selleck Chemicals, and protein was extracted. Alternatively, the cells were lysed with NP-40 buffer containing 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 1 % Nonidet P-40, 0.5 mM EDTA, PMSF (50 μg/ml) and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). N-Ethylmaleimide (10 mM) was added to the above lysis buffer when protein ubiquitination was assessed. Heart tissues were homogenized in RIPA buffer (Cat#: P0013B, Beyotime) containing a protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Cat#: P1051, Beyotime). Protein concentrations were measured using a quick start Bradford kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Equivalent protein quantities were subjected to SDS–PAGE, and the separated proteins were subsequently transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, 0.45 μm). The membranes were blocked with 5 % nonfat milk in phosphate-buffered saline with Tween-20 (PBST) for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were then probed with various antibodies diluted with primary antibody dilution buffer (P0023A, Beyotime) at 4 °C overnight. Chemiluminescence measurements were conducted using SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Densitometric analysis of the Western blots was performed using the ImageJ (https://imagej.net/ij/download.html) program.

The following antibodies were used: anti-USP7 (4833S, CST), anti-SMAD1 (1:1000, Cell Signaling, 6944 T), anti-SMAD2 (1:1000, Cell Signaling, 5339), anti-SMAD3 (1:1000, Cell Signaling, 9523S), anti-SMAD4 (1:1000, Cell Signaling, 46535 T), anti-SMAD5 (1:1000, Cell Signaling, 9517 T), anti-SMAD2/3 (1:1000, Cell Signaling, 8685S), anti-SMAD6 (1:1000, ab273106, Abcam), anti-phosphorylated SMAD2 (Ser465/467,1:1000, 18338S, CST), anti-phosphorylated SMAD3 (Ser423/425, 1:1000, 9520S, CST), anti-Myc (1:1000, A02060, Abbkine), anti-Flag (1:5000, Sigma, F1804), anti-HA (1:2000, sc-7392, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-ubiquitin (1:1000, Santa Cruz, sc-8017), anti-β-actin (1:5000, Proteintech,#78), anti-Myc (Abmart, M20002L, 1:2000), anti-SNAIL1(1:1000, 3879S, CST), anti-Vimentin (1:1000, 5741S, CST), anti-COL1A1(1:1000, 72026 T, CST), anti-K48 ubiquitin (1:1000, 4289S, CST), and anti-K63-ubiquitin (1:1000, 5621S, CST). Additional reagents were also used, including anti-Myc magnetic beads (HY-K0206, MCE), anti-Flag beads (A2220, Sigma–Merck), anti-GAPDH (1:5000, 2188S, CST) and the small- molecule inhibitor P22077 (HY-13865, MCE).

2.15. CHX chase assay

The half-life of SMAD2/3 or Flag-SMAD2/3 was determined using a CHX pulse-chase assay. The cells were transfected with Flag-SMAD2 or Flag-SMAD3 for 48 h. The cells were then treated with DMSO or CHX (50 μg/ml) for the indicated times. The cells were harvested, and equal amounts of boiled lysates were analyzed via Western blotting. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

2.16. Immunoprecipitation (IP)

The cells were lysed in lysis buffer containing a protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma) for 30 min on ice. After centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 15 min, the supernatant was harvested and subjected to immunoprecipitation with specific antibodies overnight on a rotator at 4 °C. Twenty microliters of Protein G agarose beads (Millipore, #16–266) were washed three times and then added to the supernatant samples, followed by incubation for an additional 3 h on a rotator at 4 °C. After five washes with lysis buffer, the immunoprecipitates were eluted by boiling the beads in a loading buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol for 10 min and analyzed by SDS–PAGE.

2.17. In vivo deubiquitination assay

The cells were transfected with Flag-USP7 or sh-USP7 and Myc-SMAD2 or Myc-SMAD3 plasmids with or without HA-ubiquitin. After transfection for 36–48 h, the cells were harvested on ice and lysed with NP-40 lysis buffer. SMAD2, Myc-SMAD2, or Myc-SMAD3 was immunoprecipitated using an anti-Myc antibody and then subjected to Western blotting to examine the effect of USP7 on SMAD2 or SMAD3 ubiquitination. Ubiquitinated SMAD2/3 was immunoprecipitated using anti-Myc or SMAD2/3 antibodies, and 1 % of the total cell lysate was prepared as an input control.

2.18. Wound healing and trans-well migration assays

HCAECs stably expressing sh-CON or sh-USP7 were treated with or without TGFβ2 for 36 h. HCAEC migration was assessed using a wound-healing assay, and transwell migration assays were performed according to a previously described method [36]. Wound images were acquired using a light microscope (Nikon, Japan).

2.19. In vitro permeability assessment

HCAECs stably expressing sh-CON or sh-USP7 were treated with or without TGFβ2 (10 ng/ml) for 36 h. Then, HCAECs from different groups were seeded into a transwell chamber (Corning Costar, Corning, NY, USA) at a density of 1 × 105 cells/chamber and cultured for 36 h. Following cell adhesion, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled dextran at a concentration of 1 mg/ml was introduced into the upper chamber. The permeability of HCAECs was quantified by measuring the fluorescence intensity of FITC-dextran in the lower chamber using a microplate reader (Synergy HTX, USA). Based on the relative fluorescent units in the upper and lower chambers, the permeability coefficient was determined using a previously reported formula [37]. All independent experiments were performed in triplicate.

2.20. USP7 inhibitor treatment of the murine KD model induced by CAWS

Adult mice were injected with 4 mg of CAWS to evaluate the in vivo efficacy of the USP7 inhibitor P22077 [34]. Five days post-injection, the mice were treated with either P22077 (at a dosage of 10 mg/kg) or vehicle. P22077 was diluted in 2 % DMSO and administered intraperitoneally three times per week for four weeks. At 28 days following the CAWS injection, murine cardiac tissues from each group were subjected to histological and immunofluorescence analyses, as previously described.

2.21. Statistical analyses

The data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism (version 8; San Diego, CA), and all the values are presented as the means ± standard errors of the means (SEMs). Significant differences between the mean values were determined using the Student’s t-test or a two-tailed Mann–Whitney test (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001). Differences for which p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. USP7 expression is upregulated both in KD patients and CD31+ endothelial cells from KD mice

Our prior proteomic profiling of the ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS) indicated that the protein levels of several DUBs, including FAM105A, OTUD6B, USP4, USP7, USP14, USP19, and USP32 were increased in the leukocytes of KD patients compared with those in healthy controls (Supplemental Fig. S1 A–B). Among these DUBs, the USP7 was markedly increased and mainly expressed in human cardiomyocytes and heart tissue (http://biogps.org/) (Supplemental Fig. S1C). The expression level of USP7 in leukocytes of KD patients was further verified to be increased by using more additional samples (Fig. 1A), and the USP7 mRNA level was also upregulated in the leukocytes of KD model mice at 14 and 28 days following the final CAWS injection (Fig. 1B, Supplemental Fig. S2A–D). Consistent with this observation, a significant upregulation of USP7 protein expression was detected in both HCAECs after 72-hour exposure to acute KD sera (Fig. 1 C&D), and CD31+ endothelial cells from the cardiac tissue of KD mice compared to the controls (Fig. 1. E&F). Moreover, the positive expression signaling of USP7 is mainly distributed in the overall cardiac tissue, particularly within the intimal and adventitial layers of the diseased coronary artery in KD mice, compared to PBS control mice (Fig. 1 G–I). Immunofluorescence staining further confirmed a co-localization of USP7 with CD31, with a notably higher expression of USP7-positive signaling surrounding the coronary arteries in the KD model mice relative to the control group (Fig. 1 J–L). Additionally, we found elevated expression levels of N-cadherin, Vimentin, and Snail along with decreased expression levels of VE-cadherin in the cardiac CD31+ endothelial cells of KD mice, suggesting that fibrosis or the EndoMT occurred in the cardiac tissue of KD mice (Supplemental Fig. S2E–F). These findings together indicate that USP7 levels increase in HCAECs following incubation with serum from patients with acute KD, as well as in CD31+ endothelial cells of the aortic root in KD mice, suggesting that USP7 plays a critical role in the progression of KD.

Fig. 1.

USP7 expression is upregulated in KD patients and cardiac endothelial cells from a CAWS-induced mouse model. (A) RT-qPCR analyses of USP7 mRNA expression levels in the leukocytes of KD patients and healthy controls. (B) RT-qPCR analyses of USP7 mRNA expression levels in leukocytes from KD mice and control mice at different time points. (C) Immunoblot analyses of USP7 protein levels in HCAEC treated with serum from patients with KD or healthy controls. (D) The USP7 protein expression level shown in Graph C was calculated by using the image J program. (E) Immunoblot analyses of USP7 protein levels in CD31+ endothelial cells from the cardiac tissue of KD model mice and control mice. (F) The relative USP7 protein expression level shown in graph E was calculated as indicated by using the image J program. (G) Representative graphs of H&E staining showing cellular infiltration in KD model mice. (H) Representative pictures of immunohistochemical (IHC) staining for USP7 in the aortic root sections of mice in CAWS and PBS groups. The cells positive for USP7 proteins in PBS and CAWS groups were indicated by red and green arrows, respectively as shown in graph H. The images of HE and immunofluorescence (IF) staining further validate that USP7 expression is increased in the coronary artery tissue of KD mice compared with that in the control group (J&K). The relative optical density value of USP7 shown in H and K were also calculated by using the Image J program as indicated (I&L). ca, coronary artery; ao, aorta.

3.2. USP7 inhibition attenuates the TGFβ2-mediated EndoMT, migration rate, and permeability of HCAECs

Given that the serum from KD patients can induce a USP7 expression level increase in endothelial cells, we then questioned whether USP7 affects the physiological functions of endothelial cells under the stimulation of various cytokines in the serum of KD patients. Thus, we first measured the expression level of cytokines including TGF-β2 and TNFα in the sera of KD patients. These two cytokines were validated to increase in KD patients, and those KD patients with CALs presented significantly higher expression levels of TGF-β2 and TNFα than did those without CALs (Supplemental Fig. S3A). Moreover, TGF-β2 treatment caused the morphological transformation changes of HCAECs from a paving stone-like appearance to a long spindle-shaped form, akin to that observed for myofibroblasts (Supplemental Fig. S3B). At the molecular level, TGF-β2 treatment leads to EndoMT by increasing the mesenchymal markers FN1, SNAIL, COL1A1, and Vimentin and decreasing the expression level of the endothelial marker gene VE-cadherin (Supplemental Fig. S3 C–F), whereas USP7 deficiency remarkably alleviated TGF-β2-induced EndoMT in HCAECs by up-regulating the mRNA expression levels of VE-cadherin, and down-regulating the mRNA expression levels of FN1, COL1A1 and Vimentin (Fig. 2 A–D). Consistently, USP7 deficiency reduced the up-regulated protein level of FN1, Vimentin, N-cadherin, and SNAIL, and partially restored the decreased protein level of VE-cadherin during TGF-β2 treatment in HCAECs (Fig. 2E). And this observation was further validated by the fluorescence assay of FN1 and VE-cadherin (Supplemental Fig. S3G & H). Additionally, USP7 inhibition significantly decreased both the number of migrating cells, the horizontal and vertical migration rate of HCAECs, and the permeability of HCAECs revealed by fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-dextran assay during TGF-β2 treatment (Fig. 2F–I). These results thus indicate that the inhibition of USP7 impedes the EndoMT and the migration of HCAECs during TGFβ2 treatment, thereby alleviating the endothelial barrier dysfunction caused by activated TGFβ signaling in patients with KD.

Fig. 2.

Knockdown of USP7 suppresses the TGFβ2-mediated EndoMT, migration, and permeability of HCAECs. (A-D) HCAECs infected with the ShCON or ShUSP7 lentivirus were cultured in the absence or presence of 10 ng/mL of TGF-β2, followed by qRT–PCR analyses of the expression of VE-cadherin, COL1A1, FN1, and Vimentin genes. (E) Immunoblot analysis of the protein expression levels of VE-cadherin, FN1, Vimentin, N-cadherin, and SNAIL in HCAECs infected with the ShCON or ShUSP7 lentivirus and cultured in the absence or presence of 10 ng/mL TGF-β2. (F) HCAECs infected with the ShCON or ShUSP7 lentivirus were cultured in the absence or presence of TGF-β2 and then subjected to wound healing and transwell migration assays. The number of migrated cells and the migration rate were calculated (G&H). The effect of USP7 inhibition on the barrier function of HCAECs was determined via a FITC-DX penetration assay, and the relative permeability coefficient of each group was calculated (I).

3.3. USP7 deficiency protects mice from CAWS-induced cardiac inflammation and EndoMT

Next, to further investigate the role of USP7 during the pathogenesis of KD in vivo,Usp7+/− knockout mice generated via the CRISPR/Cas9 system were used and the successful deletion of USP7 in heart homogenates was verified by immunoblotting (Fig. 3A&B). Four-week-old male wild-type (WT) and Usp7+/− knockout mice were selected and intraperitoneally injected with either PBS or CAWS for consecutive 5 days, resulting in the following four groups: WT-PBS, WT-CAWS, Usp7+/−-PBS and Usp7+/−-CAWS (Fig. 3C). Compared to the control mice developing minor or no sign of coronary inflammation, the WT mice injected with CAWS showed a profound infiltration of inflammatory cells in the tissue surrounding the aortic root, the frequent disruption of elastic fibers and vasculitis of the coronary arteries which extends well into the mid portion of the mouse heart, whereas these pathogenetic symptoms were partially mitigated upon USP7 deletion as demonstrated by the HE and EVG staining (Fig. 3 D–E). Moreover, USP7 deletion significantly alleviated the increased collagen fiber content and percentage of the collagen fiber area induced by CAWS, as demonstrated by using Masson and Sirius Red staining (Fig. 3F&G). Immunofluorescence assay of murine cardiac tissue demonstrated that the deletion of USP7 prevents the coronary artery cells from EndoMT in KD mice by upregulating the VE-cadherin positive signaling and downregulating the FN1 positive signaling (Fig. 3H–K). Moreover, USP7 deletion, at least in part, mitigated the EndoMT state by increasing the VE-cadherin protein level and decreasing Vimentin levels simultaneously in the CD31+ endothelial cells of murine cardiac tissue (Fig. 3L). These results together indicate that USP7 deficiency protects mice from CAWS-induced EndoMT, fibrosis, and systematic vasculitis, which are characterized by reduced leukocyte infiltration in the aortic artery and the overall cardiac tissues of KD mice.

Fig. 3.

USP7 deficiency attenuates inflammation, fibrosis and the EndoMT in murine heart and coronary artery tissues. (A) Schematic of the mouse USP7 gene knockout strategy. (B) Immunoblot analysis of the USP7 protein level in CD31+ endothelial cells from the cardiac tissues of wild-type and USP7+/−mice. (C) Schematic showing wild-type or USP7 knockout mice injected with PBS or CAWS, and the cardiac tissues from the four groups were harvested and analyzed after 4 weeks. (D) Representative images showing H&E and Elastica van Gieson (EVG) staining of the mouse aorta (ao) and coronary artery (ca) in wide-type or USP7+/− mice 28 days after CAWS injection. (E) The vascular inflammation score indicates the severity of coronary arteritis, as indicated in D. (F) Representative images showing Masson’s and Sirius red staining of the mouse aorta (ao) and coronary artery (ca) in wide-type or USP7+/− mice injected with PBS or CAWS at 28 days. (G) The area positive for Sirius-red staining collagen fibers shown in F was calculated for each group. (H & I) Immunofluorescence staining for CD31 together with VE-cadherin or FN1 in murine cardiac tissue of the four groups. (J&K) The relative fluorescence intensities of VE-cadherin and FN1 were calculated. (L) Immunoblot analysis of VE-cadherin, Vimentin, USP7 and GAPDH protein expression level in CD31+ endothelial cells from the murine cardiac tissues of the four groups.

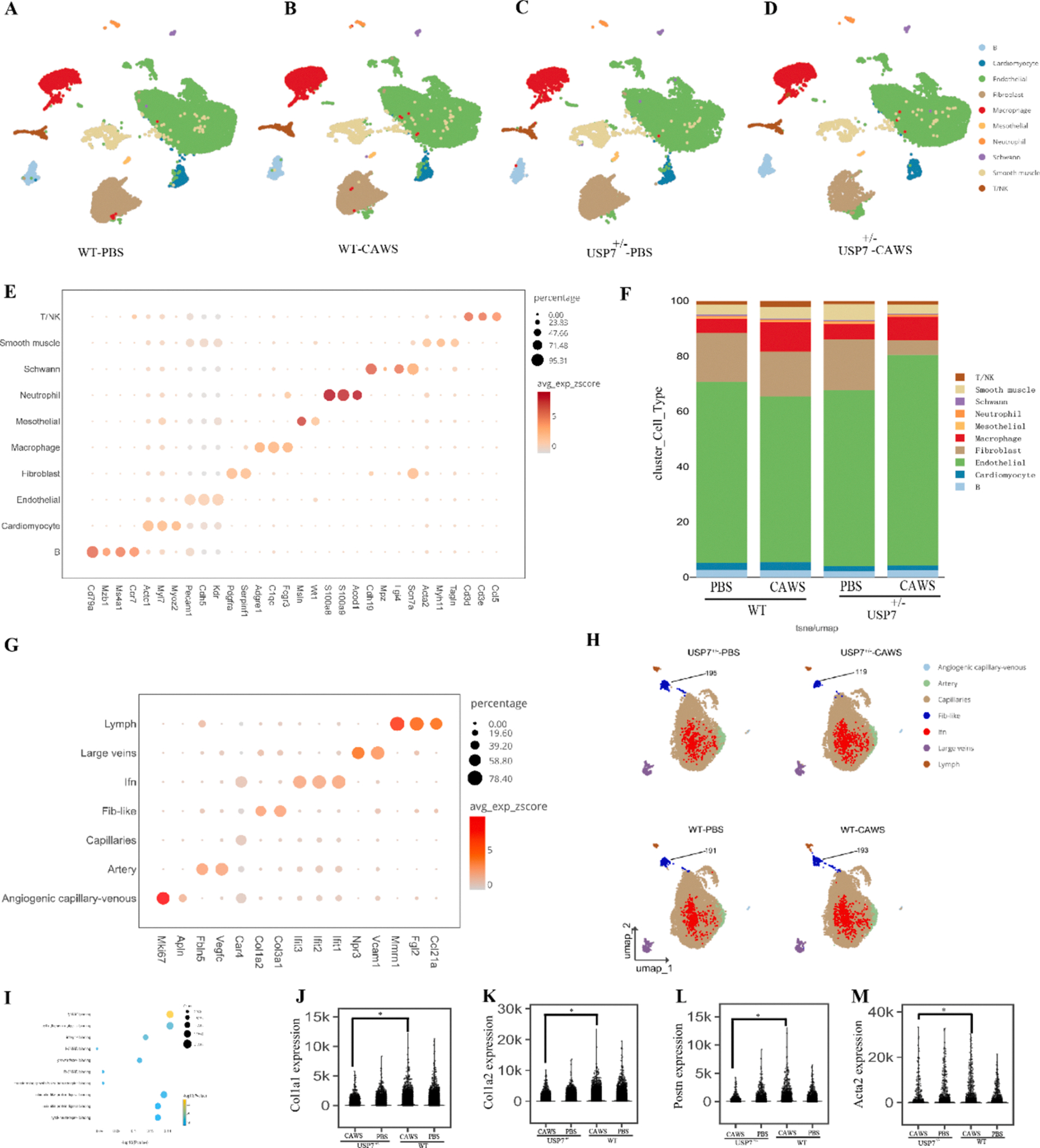

3.4. USP7 deficiency augments the proportion of endothelial cells but decreases the proportion of macrophages and fibroblasts in the murine cardiac tissue

Because USP7 deficiency alleviated the EndoMT and the overall cardiac vasculitis by decreasing leukocyte infiltration in the cardiac tissue of KD mice, we next sought to determine which cell type in the cardiac tissue are largely affected by USP7 deletion. Thus, single cell RNA sequencing of murine cardiac tissue from each group, including WT-PBS, WT-CAWS, Usp7+/−-PBS, and Usp7+/−-CAWS was conducted. Based on the expression levels of well-established maker genes [38,39], our results identified a total of ten cell types in murine cardiac tissue, including B cells (Cd79a, Ms4a1, and Mcr7), cardiomyocytes (Myoz2, Myl7, and Actc1), endothelial cells (Cdh5, Pecam1, and Kdr), fibroblasts (Serpinf1, Pdgfra, and Scn7a), macrophages (Fcgr3, C1qc, and Adgre1), mesothelial cells (Wt1 and Msln), neutrophils (S100a9, S100a8 and Acod1), Schwann cells (Cdh19, Lgi4, and Scn7a), smooth muscle cells (Acta2, Myh11, and Tagln), and T/NK cells (Ccl5, Cd3e, and Cd3d) (Fig. 4A–E). Among all the cell types identified in murine cardiac tissue, we found that endothelial cells represented the largest proportion, and KD mice had a significantly decreased proportion of endothelial cells compared with that of control mice. Interestingly, CAWS-challenged mice lacking USP7 showed a significant increase in the percentage of endothelial cells and concomitant decreases in the proportions of fibroblasts and macrophages in cardiac tissue (Fig. 4F), indicating that USP7 deficiency, at least in part, restored the dysregulated proportion of endothelial cells, fibroblast and macrophages to a relatively normal levels in KD mice. However, USP7 deficiency do not greatly affect the proportion of other cell types including neutrophils, B cells, and T/NK cells, although these cells might also contribute to cardiovascular pathology by infiltrating cardiac tissue and releasing proinflammatory cytokines.

Fig. 4.

USP7 deficiency altered the cellular landscape in the cardiac tissue of KD model mice. Two-dimensional representation of cell types identified by scRNA-seq in heart tissues of wild-type and USP7+/− mice injected with either PBS or CAWS. The dimensional reduction was performed via the uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP). Each dot represents a cell, which is colored according to cell type. The cells were pooled across all samples and separated by different treatments: (A) wild-type mice injected with PBS; (B) wild-type mice injected with CAWS; (C) USP7+/− mice injected with PBS; and (D) USP7+/−-mice injected with CAWS. (E) A total of ten different types of cells were identified in murine heart tissue according to the expression of the indicated marker genes. (F) The percentages of the ten types of cells among the four groups are shown in the histogram. (G) Marker genes were used to distinguish seven subtypes of endothelial cells in murine cardiac tissue among each group. (H) UMAP analysis of endothelial cells and the number of fibroblast-like cells in each group. (I) GO enrichment analyses of differentially expressed genes in KD mice are correlated with TGFβ-SMAD signaling. (J-M) Significance of differences in Col1a1, Col1a2, Postn, and Acta2 gene expression levels among the different groups.

More specifically, to ascertain how USP7 deficiency affects the phenotypic and functional changes in endothelial cells, we further analyzed 14 endothelial cell clusters and categorized them into 7 different subtypes based on their gene expression signatures [40,41]. The endothelial cell clusters in each group included interferon-rich endothelial cells (Ifn), lymphatic endothelial cells (lymph), arterial cells, fibroblast-like cells (fib-like), venous cells, capillary cells, and angiogenic capillary-venous cells (Fig. 4G). Notably, USP7 deletion caused fewer number of fib-like cells in murine cardiac tissue compared to wild-type mice (Fig. 4H). Furthermore, to identify the genes regulated by USP7 in murine KD heart tissue, we performed a differential expression analysis using DESeq2 [42]. Gene Ontology (GO) analyses of the DEGs between the WT-CAWS and Usp7+/− CAWS groups revealed that the upregulated genes were mainly enriched in the regulation of metal ion transport and cell morphogenesis (Supplemental Fig. S41A). The downregulated genes were enriched mainly in protein folding, muscle contraction, and leukocyte cell–cell adhesion (Supplemental Fig. S4B). Certain specific DEGs were enriched in the TGFβ/SMAD pathway, which is closely associated with EndoMT and fibrosis (Fig. 4I). Consistent with the results aforementioned, in the CAWS-challenged mice lacking USP7, the expression level of fibrillar-forming collagen or vascular remodeling genes, including Col1a1, Col1a2, Postn, and Acta2, was markedly decreased in murine cardiac tissue compared to the control group (Fig. 4J–M). Taken together, USP7 deletion not only altered the cellular landscape, especially increased the proportion of endothelial cells, and decreased the proportion of macrophages, but also dramatically affected the expression level of genes related to immune cell responses and TGFβ/SMAD signaling in the cardiac tissue of KD model mice.

3.5. USP7 modulates the EndoMT by increasing SMAD2 and SMAD3 protein turnover

Based on the above findings, we investigated the mechanisms through which USP7 regulates the EndoMT. To this end, we first assessed whether USP7 affects the expression levels of SMADs, which are the main mediators of TGF-β signaling. We found that USP7 overexpression significantly increased the protein level of SMAD2 and SMAD3 but had little or no effect on the expression levels of SMAD1 and SMAD4–6 in 293 T cells (Fig. 5A). Consistently, USP7 knockdown decreased the expression levels of SMAD2 and SMAD3 in HCAECs (Fig. 5B). Moreover, the mRNA levels of SMAD2 and SMAD3 were not affected by the overexpression or knockdown of USP7 whether in HCAECs or 293 T cells (Supplemental Fig. S5A&B), indicating that USP7 likely exerts its regulatory effects on SMAD2/3 at the protein level rather than at the mRNA level. In addition, increasing amounts of USP7 increased the protein levels of SMAD2 and SMAD3 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5C&D). To further validate that SMAD2/3 proteins are regulated at the posttranslational level, we treated HCAECs with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 with or without the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX) for the indicated durations. Our results showed that the half-life of the SMAD2/3 protein was approximately 4 h, and treatment of HCAECs with MG132 significantly decreased the degradation rate of SMAD2 and SMAD3 induced by CHX (Fig. 5E & Supplemental Fig. S5C&D). The ectopic overexpression of USP7 not only increased the SMAD2 and SMAD3 protein levels but also attenuated their degradation rate induced by CHX (Fig. 5F–I). Conversely, the knockdown of USP7 led to the expression levels of the endogenous SMAD2/3 proteins decreasing and thus accelerated their degradation induced by CHX in HCAECs (Fig. 5J–L). Similarly, this decrease in the SMAD2/3 protein levels was further validated in CD31+ cardiac endothelial cells isolated from USP7-deficient mice (Fig. 5M). These findings collectively suggest that USP7 modulates the EndoMT by regulating the expression levels and stability of the SMAD2/3 proteins.

Fig. 5.

USP7 enhances the turnover and stability of SMAD2 and SMAD3 proteins. (A) Immunoblot analysis of SMAD proteins after overexpression of the Flag-USP7 plasmid in 293 T cells. (B) Immunoblot analysis of SMAD proteins after endogenous USP7 was knocked down with a lentivirus in HCAECs. (C&D) Immunoblot analysis of Flag-SMAD2 and SMAD3 proteins in 293 T cells co-transfected with a constant amount of SMAD2 or SMAD3 and increasing amounts of the Flag-USP7 plasmid. (E) Immunoblot analysis of SMAD2 and SMAD3 levels in HCAEC cells after treatment with CHX and MG132. (F&G) 293 T cells were transfected with Myc-SMAD2 or Myc-SMAD3, with or without Flag-USP7. Then, the cells were treated with CHX (50 μg/ml) for different durations and analyzed by immunoblotting with the indicated Abs. (H & I) The intensity of the protein bands in F & G was quantified via Image J, and the quantification of the normalized SMAD2 and SMAD3 band intensity is shown in the right panel. (J) Immunoblot analysis of the endogenous SMAD2 and SMAD3 proteins in HCAEC stably expressing ShCON or ShUSP7 lentivirus were treated with CHX for different durations. (K&L) The intensity of the SMAD2 and SMAD3 protein bands in J was quantified using Image J software. (M) Immunoblot analysis of SMAD2, SMAD3, and USP7 protein expression levels in CD31+ cells in murine cardiac tissue from each group.

3.6. USP7 interacts with SMAD2/3 and deubiquitinates both polyubiquitinated proteins

To elucidate how USP7 modulates the turnover of the SMAD2/3 proteins, we subsequently conducted a co-IP experiment, the results of which showed that immunoprecipitation with an anti-Flag antibody coprecipitated not only Flag-USP7 but also Myc-SMAD2 and Myc-SMAD3 in 293 T cells (Fig. 6A&B). Further bioinformatic analyses calculated by PyMOL software revealed that multiple groups of residues facilitate the formation of hydrogen bonds between USP7 and SMAD2, as exemplified by the hydrogen bond between ARG846 of USP7 and ASP262 of SMAD2 (Supplemental Fig. S5E). In addition, USP7 interacted with SMAD2/3 in physiological conditions, as validated by endogenous USP7 coimmunoprecipitating with endogenous SMAD2/3, and vice versa, indicating that the three proteins form a complex in HCAECs (Fig. 6C&-D). Moreover, ectopic overexpression of USP7 significantly decreased the polyubiquitin levels of both the exogenous and endogenous SMAD2 and SMAD3 proteins (Fig. 6E&-F, Supplemental Fig. S6 A&B), whereas USP7 knockdown markedly increased the polyubiquitin levels of endogenous SMAD2/3 in HCAECs (Fig. 6G). Congruently, P22077 treatment led to increased polyubiquitination of SMAD2/3 in 293 T cells (Supplemental Fig. S6C&D), indicating that USP7 deubiquitinates SMAD2/3 relied on its catalytic cysteine residue. Furthermore, the overexpression of wild-type USP7 but not the catalytically inactive mutant of USP7 (USP7C223A) largely decreased the polyubiquitination level of SMAD2/3 (Fig. 6H and Supplemental Fig. S6E), demonstrating that the enzymatic activity of USP7 is essential for its function in regulating SMAD2/3 deubiquitination level. In addition, overexpression of USP7 decreased both the exogenous and endogenous K48-linked polyubiquitination level of SMAD2 and SMAD3 (Fig. 6I&J and Supplemental Fig. S6F&G), whereas USP7 knockdown increased the K48-linked polyubiquitination of both proteins (Fig. 6K and Supplemental Fig. S6H).

Fig. 6.

USP7 interacts with and deubiquitinates SMAD2 and SMAD3 proteins. (A &B) Flag-USP7 plasmids along with Myc-SMAD2 or Myc-SMAD3 plasmids were co-transfected into 293 T cells for 36 h. Then, the cells were harvested and lysed, and the lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag beads followed by immunoblotting analysis with anti-Myc Abs. (C & D) The interaction between SMAD2/3 and USP7 was assessed in HCAEC. WCLs were subjected to IP with an anti-SMAD2/3 antibody or anti-USP7 antibody, followed by IB analysis with indicated Abs. (E & F) 293 T cells were transfected with Flag-USP7, and Myc-SMAD2 with or without HA-ubiquitin plasmid. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were lysed and immunoprecipitated with an anti-Myc antibody, followed by an anti-HA or anti-ubiquitin antibody. WCLs were subjected to IB with anti-Flag, anti-Myc, and GAPDH antibodies. (G) Knockdown of USP7 increases the poly-ubiquitination of endogenous SMAD2/3 in HCAECs. (H) Overexpression of wild-type USP7, but not the C223A mutant, decreases the polyubiquitination of SMAD2 in 293 T cells. (I) 293 T cells were transfected with HA-R48K ubiquitin plasmid together with My-SMAD2 in the presence or absence of USP7. The Myc-SMAD2 protein was subsequently immunoprecipitated with anti-myc beads, followed by immunoblot analysis with anti-HA Abs. (J) Overexpression of USP7 decreases the level of K48 ubiquitin in endogenous SMAD2 in 293 T cells. (K) Knockdown of USP7 increases the K48 polyubiquitin level of SMAD2 in 293 T cells. (L) 293 T cells were transfected with HA-ubiquitin and plasmids for WT SMAD2, SMAD2K39R, SMAD2K420R, and SMAD2K156R/K383R along with Flag-USP7 or empty vector. Equal amounts of protein were immunoprecipitated with an antibody against Myc and immunoblotted with an anti-HA-ubiquitin chain antibody. (M) 293 T cells were transfected with the Flag-USP7 plasmid. After 36 h, the cells were immune stained with mouse anti-Flag antibodies, followed by staining with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibodies. The cell nuclei were stained with DAPI, and fluorescence images were captured. (N) HCAECs transfected with or without the ShUSP7 lentivirus were treated with TGFβ2 for 0, 0.5, 1 or 2hrs. The levels of the p-SMAD2 (Ser465/Ser467), p-SMAD3(Ser423/425), USP7, SMAD2, SMAD3 and GAPDH proteins were measured by immunoblotting.

Furthermore, we constructed several mutants to identify the specific lysine (K) residue by which USP7 mediates the deubiquitination of SMAD2 by replacing lysine (K) with arginine (R), such as K13R, K19R, K39R, K46R, K63R, K420R, K156R and K383R. By cotransfecting these mutant plasmids or wild-type SMAD2 together with or without USP7, we determined that USP7 modulated the polyubiquitination of SMAD2 specifically at lysine 156 and lysine 383, as evidenced by the inability of USP7 to decrease the polyubiquitination of mutant SMAD2 (K156R and K383R) (Fig. 6L). Additionally, given the expression level of EndoMT-related genes is affected by both the nuclear entry and expression levels of phosphorylated SMAD2/3 [49], we then explored whether USP7 could modulate the levels of p-SMAD2 and p-SMAD3. Our results revealed that USP7 overexpression facilitated the nuclear entry of p-SMAD2 induced by TGF-β2 in 293 T cells (Fig. 6M), whereas USP7 knockdown in HCAECs decreased the amount of p-SMAD2 and p-SMAD3 mediated by TGF-β2 (Fig. 6N). Taken together, these findings indicate that USP7 modulates TGFβ2 signaling by stabilizing SMAD2 and SMAD3 and deubiquitinates their K48-linked polyubiquitination, thereby leading to the activation of the TGF-β2/p-SMAD signaling-mediated EndoMT or cardiac fibrosis during KD pathogenesis.

3.7. The USP7 inhibitor P22077 attenuates the EndoMT and inflammation in vitro and in vivo

Finally, to intervene in the EndoMT triggered by an increased level of USP7 in KD, we first treated HCAECs with USP7 inhibitor P22077 in the presence or absence of TGF-β2. As illustrated in Fig. 7A, P22077 treatment decreased the expression levels of FN1, Vimentin, N-cadherin, and SNAIL, but increased the endothelial marker protein VE-cadherin during TGF-β2 stimulation. Moreover, the P22077 treatment alleviated the increased migration rate of HCAECs caused by TGF-β2 (Fig. 7B &C). Importantly, we also evaluated the in vivo efficacy of P22077 treatment in reducing EndoMT and inflammation in KD mice. Four-week-old male WT mice were injected with either PBS or CAWS, and a subset of CAWS-injected mice was treated with P22077 three times a week, and 4 weeks later, cardiac tissues were collected and analyzed (Fig. 7D). The results showed that KD mice presented an increased level of cell infiltration, an expanded collagen fiber area, and the onset of intimal hyperplasia, compared with control mice, however, whereas these symptoms were significant reduced in P22077-treated mice (Fig. 7E–H). This phenomenon was further confirmed by Western blotting analysis, which shows that P22077 administration markedly reduced the levels of Vimentin and N-cadherin and partially restored the decreased level of the VE-cadherin protein in CD31+ endothelial cells from KD mice (Fig. 7I). In conclusion, pharmacological treatment with the USP7 inhibitor P22077 can reduce inflammation, EndoMT, vascular remodeling and dysfunction in cardiac tissue of KD murine model.

Fig. 7.

The administration of P22077 alleviated inflammation, the EndoMT and fibrosis in a KD mouse model. (A) HCAECs treated with DMSO or 10 μM P22077 were cultured in the absences or presences of 10 ng/mL TGF-β2, followed by immunoblot analyses of FN1, Vimentin, N-cadherin, VE-cadherin, and SNAIL. (B) Migration of HCAECs pretreated with or without P22077 followed by stimulation with or without TGF-β2 (10 ng/mL) for 24 h was determined using a wound-healing assay. (C) The migration rate of HCAECs shown in B was calculated. (D) Schematic showing the timeline for the in vivo administration of P22077 to the CAWS-induced KD mouse model. (E) H&E- and EVG-stained heart tissue sections from PBS- and CAWS-injected mice treated with or without P22077. (F) Masson- and Sirius Red-stained heart tissue sections from PBS- and CAWS-injected mice treated with or without P22077. (G&H) The graphed data depict the scores of vascular inflammations in E and the collagen fiber area in F among the different groups. (I) Immunoblot analysis of USP7, N-cadherin, VE-cadherin, and Vimentin protein expression levels in CD31+ endothelial cells isolated from PBS-injected mice or CAWS-injected mice treated with or without P22077.

4. Discussion

This study uncovered the pivotal role of USP7 in regulating cardiac inflammation and vascular remodeling in KD using both in vivo and in vitro models. Several key findings are as follows: (i) USP7 promotes TGFβ2-mediated vascular remodeling and fibrosis by exacerbating the EndoMT. (ii) USP7 deficiency leads to cellular landscape changes by increasing the proportion of endothelial cells and decreasing the proportion of macrophages and fibroblasts in the cardiac tissues of KD mice. (iii) USP7 interacts with SMAD2 and SMAD3 and removes the K48-linked ubiquitination of both proteins in endothelial cells. (iv) USP7 increases the stability of both the SMAD2 and SMAD3 proteins and this process leads to the accumulation of p-SMAD2 in the nucleus, thus facilitating the transcription of EndoMT-related genes and ultimately contributing to vascular dysfunction and remodeling in KD mice. (v) Genetic knockout or pharmacological inhibition of USP7 alleviates inflammation and the EndoMT in cardiac tissue of a KD mouse model. The main findings of this study are schematically presented in Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Schematic illustration of the main finding of this study. The up-regulated USP7 in KD sustains the protein turnover of SMAD2 and SMAD3 via deubiquitinating their K48-linked polyubiquitination, thereby facilitating p-SMAD2 nuclear entry and TGF-β2 signaling-mediated EndoMT and vascular remodeling. Pharmacological or genetic inhibition of USP7 markedly mitigates inflammation, the EndoMT and fibrosis in the endothelium and cardiac tissue of KD model mice.

Deubiquitinating enzymes function as key mediators of posttranslational modification and are broadly involved in the regulation of vascular diseases [43,44]. Although miR-483 [45] and circRNA-3302 [46] have been shown to regulate the EndoMT in individuals with KD, whether deubiquitinating enzymes are involved in vascular remodeling during KD pathogenesis remains largely unexplored. Previously, we found that the ubiquitin–proteasome system plays an important role in KD, and several DUBs show different expression levels in the leukocytes of KD patients relative to the healthy controls [23]. Among these DUBs, we reported that USP5 promotes endothelial inflammation via TNFα-mediated signaling in KD patients [47]. Herein, USP7 was selected as another critical DUB involved in KD. One of the reasons is that USP7 was also shown to promote TNFα signaling that is increased in KD patients, and in clinical, the alternative drugs infliximab and etanercept were used to treat KD by blocking TNFα signaling [2,24]. USP7 deficiency attenuates TGF-β2-induced EndoMT in HCAECs and fibrosis and EndoMT in cardiac tissues of KD model mice. Mechanistically, USP7 interacts with the SMAD2/SMAD3 complex and deubiquitinates both proteins in a K48-linked manner, which is mainly involved in proteasomal degradation. Interestingly, SMAD2 and SMAD3 can be deubiquitinated simultaneously in a K48-linked manner via a DUB USP7. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to identify the lysine 156 and lysine 383 residues of SMAD2 are simultaneously catalyzed by USP7, albeit the specific lysine residues in SMAD3 regulated by USP7 remain to be investigated.

USP7 regulates different substrates under different physiological or pathogenetic conditions [48]. For example, USP7 was previously shown to modulate the deubiquitination and stabilization of p53/MDM2, N-Myc, PTEN, and NEDD4L [49,50] and catalyze the mono-ubiquitination of SMAD3 in p53-deficient lung cancer [51] and stabilize SMAD3 by cleaving its K63-linked ubiquitin chains, thereby implicating in EndoMT in mice with heart failure [52]. Additionally, USP7 suppresses TGFβ signaling by negatively regulating SMAD-mediated transcriptional activity [50]. However, different from these observations, our study proved that USP7 promotes TGFβ signaling by increasing the expression level of both the SMAD2 and SMAD3 proteins in endothelial cells during KD pathogenesis. USP7 functioned as an upstream regulator of SMAD2/3 in modulating the TGFβ2-mediated EndoMT, vascular injury, and remodeling. Importantly, these findings could also explain why the activated TGFβ signaling is activated in KD patients, as evidenced by the fact that increased expression levels of the TGF-β2 receptor (TGFBR2) and phosphorylated SMAD3, which contribute to cardiac remodeling and coronary artery stenosis, were indeed observed in the thickened intima and adventitia of arteries in KD patients [18,53,54]. Moreover, genetic variations and dysfunctions of the TGFBR2, SMAD3, and SMAD5 proteins are associated with the development of coronary artery aneurysms and aortic root dilatation in KD patients [55,56], demonstrating the pivotal role of TGF-β/SMAD signaling in regulating vascular homeostasis and endothelial function during KD pathogenesis.

Notably, in addition to TGF-β2, several other cytokines including TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, and IFN-γ known to promote mesenchymal transition [57–59], are also upregulated in the serum of KD patients [60], indicating that they might cooperatively induce the endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition and coronary artery remodeling during KD pathogenesis. Since in vitro cultivation of HCAECs with serum obtained from patients with KD could stimulate EndoMT [54], this effect might represent a close clinical association between EndoMT and KD. Because the TGF-β/SMAD signaling is a key driver of the vascular EndoMT and inflammation, which in turn influences the homeostasis of endothelial cells [57,61]. Consequently, the increased EndoMT mediated by the USP7/SMAD complex might destroy endothelial junction integrity and increase the endothelial migration rate, vascular permeability, and leukocyte infiltration within the cardiac tissue of KD patients and murine models. As demonstrated here and in previous studies, the KD murine model largely recapitulates the primary immunopathologic characteristics observed in KD patients, with neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages, and T cells infiltrating into the arterial walls of the cardiac tissue [62–67]. In addition, a less extensive EndoMT caused by USP7 deficiency was further validated by the increased proportion of endothelial cells and decreased proportion of fibroblasts and macrophages in the cardiac tissues of KD mice, albeit USP7 deficiency had little or no effect on the proportion of other types of immune cells detected in the murine cardiac tissue, which still deserves further research. Whereas treatment with P22077, which is a potent inhibitor of USP7 [34] not only suppresses the TGF-β2-induced EndoMT in HCAECs, but also protects mice from CAWS-induced EndoMT, fibrosis and inflammation in cardiac tissue. These phenomena suggest that alternative therapies involving the administration of USP7 inhibitor may offer enhanced protective effects and minimize the risk of coronary artery remodeling in IVIG-resistance patients. Further studies concerning the development of novel compounds targeting USP7 activity and the exploration of the related mechanisms that enable robust therapeutic efficiency by concurrently inhibiting EndoMT and inflammation will be important and strengthen the impact of our present work. It is undeniable that the current study has limitations. First, we used global USP7 knockout mice to investigate the role of USP7 in KD and thus could not exclude the effects of USP7 from other cell types. The utilization of mice with conditional USP7 knockout in endothelial cells might strengthen the present findings. Second, although USP7 deficiency or USP7 inhibitor treatment significantly mitigates CAWS-induced vascular inflammation, EndoMT, and fibrosis in experimental models, including human cell lines and mice, whether and how USP7 regulates other signaling pathways, including the Wnt, BMP, and FGF pathways, during KD pathogenesis remain unknown. In addition, the specific lysine residues of SMAD3 that are deubiquitinated by USP7 remain unknown. Although the sera of KD patients can induce USP7 expression levels in HCAECs, the precise trigger remains unclear, which is another important aspect that deserves further research.

In conclusion, our study provides the first experimental evidence that coronary artery remodeling and inflammation in patients with KD are associated with increased levels of USP7 and are sensitive to USP7 inhibition in a relevant KD model. Mechanistically, USP7 functions as a DUB by sustaining TGFβ-SMAD signaling pathways that promote EndoMT and fibrosis, thereby exacerbating cardiovascular lesions in patients with KD. These findings increase our understanding of the effects of DUBs on inflammation and vascular remodeling in KD and demonstrate the importance of the development of innovative drugs that target USP7 for treating SMAD-mediated vascular diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the members in the department of pediatric cardiology, and colleagues in the institute of pediatric research for the support of this study.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number nos. 82171797, 82371806, 81971477, 82070512, 82,470,523 and 82270529, the Jiangsu Provincial Social Development Project (grant number BE2021655), and the Gusu Health Talent Program (grant number GSWS2020038), and the National Institute of Health grant (R01HL166327, to HY).

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

6. Availability of data and materials

Data supporting the present study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Guanghui Qian: Writing – original draft, Project administration, Data curation. Yan Wang: Methodology, Data curation. Hongwei Yao: Writing – review & editing, Resources. Zimu Zhang: Software. Wang Wang: Validation, Data curation. Lei Xu: Data curation. Wenjie Li: Resources. Li Huang: Investigation, Data curation. Xuan Li: Visualization, Methodology, Data curation. Yang Gao: Visualization, Methodology, Data curation. Nana Wang: Software, Resources. Shuhui Wang: Visualization, Investigation, Formal analysis. Jian Pan: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Haitao Lv: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2024.113823.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- [1].Burns JC, The etiologies of Kawasaki disease, J. Clin. Invest. 134 (5) (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].McCrindle BW, Rowley AH, Newburger JW, Burns JC, Bolger AF, Gewitz M, Baker AL, Jackson MA, Takahashi M, Shah PB, Kobayashi T, Wu MH, Saji TT, Pahl E, American E Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Y. Kawasaki Disease Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the, C. Council on, N. Stroke, S. Council on Cardiovascular, Anesthesia, E. Council on, Prevention, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Long-Term Management of Kawasaki Disease: A Scientific Statement for Health Professionals From the American Heart Association, Circulation 135(17) (2017) e927–e999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Tsuda E, Hamaoka K, Suzuki H, Sakazaki H, Murakami Y, Nakagawa M, Takasugi H, Yoshibayashi M, A survey of the 3-decade outcome for patients with giant aneurysms caused by Kawasaki disease, Am. Heart J. 167 (2) (2014) 249–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Watts RA, Hatemi G, Burns JC, Mohammad AJ, Global epidemiology of vasculitis, Nat Rev Rheumatol 18 (1) (2022) 22–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Li X, Chen Y, Tang Y, Ding Y, Xu Q, Sun L, Qian W, Qian G, Qin L, Lv H, Predictors of intravenous immunoglobulin-resistant Kawasaki disease in children: a meta-analysis of 4442 cases, Eur J Pediatr 177 (8) (2018) 1279–1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Skochko SM, Jain S, Sun X, Sivilay N, Kanegaye JT, Pancheri J, Shimizu C, Sheets R, Tremoulet AH, Burns JC, Kawasaki Disease Outcomes and Response to Therapy in a Multiethnic Community: A 10-Year Experience, J Pediatr 203 (2018) 408–415 e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Noval Rivas M, Arditi M, Kawasaki disease: pathophysiology and insights from mouse models, Nat Rev Rheumatol 16 (7) (2020) 391–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Stock AT, Parsons S, D’Silva DB, Hansen JA, Sharma VJ, James F, Starkey G, D’Costa R, Gordon CL, Wicks IP, Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin Inhibition Prevents Coronary Artery Remodeling in a Murine Model of Kawasaki Disease, Arthritis Rheumatol 75 (2) (2023) 305–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Crystal MA, Syan SK, Yeung RS, Dipchand AI, McCrindle BW, Echocardiographic and electrocardiographic trends in children with acute Kawasaki disease, Can. J. Cardiol. 24 (10) (2008) 776–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Printz BF, Sleeper LA, Newburger JW, Minich LL, Bradley T, Cohen MS, Frank D, Li JS, Margossian R, Shirali G, Takahashi M, Colan SD, I. , Pediatric Heart Network, Noncoronary cardiac abnormalities are associated with coronary artery dilation and with laboratory inflammatory markers in acute Kawasaki disease, J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 57 (1) (2011) 86–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ding YY, Ren Y, Feng X, Xu QQ, Sun L, Zhang JM, Dou JJ, Lv HT, Yan WH, Correlation between brachial artery flow-mediated dilation and endothelial microparticle levels for identifying endothelial dysfunction in children with Kawasaki disease, Pediatr Res 75 (3) (2014) 453–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Altman CA, Clinical assessment of coronary arteries in Kawasaki disease: Focus on echocardiographic assessment, Congenit Heart Dis 12 (5) (2017) 636–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Manlhiot C, Niedra E, McCrindle BW, Long-term management of Kawasaki disease: implications for the adult patient, Pediatr Neonatol 54 (1) (2013) 12–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Pinto FF, Laranjo S, Parames F, Freitas I, Mota-Carmo M, Long-term evaluation of endothelial function in Kawasaki disease patients, Cardiol Young 23 (4) (2013) 517–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Dhillon R, Clarkson P, Donald AE, Powe AJ, Nash M, Novelli V, Dillon MJ, Deanfield JE, Endothelial dysfunction late after Kawasaki disease, Circulation 94 (9) (1996) 2103–2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gordon JB, Kahn AM, Burns JC, When children with Kawasaki disease grow up: Myocardial and vascular complications in adulthood, J Am Coll Cardiol 54 (21) (2009) 1911–1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Chen PY, Schwartz MA, Simons M, Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition, Vascular Inflammation, and Atherosclerosis, Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine 7 (2020) 53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Shimizu C, Oharaseki T, Takahashi K, Kottek A, Franco A, Burns JC, The role of TGF-beta and myofibroblasts in the arteritis of Kawasaki disease, Hum Pathol 44 (2) (2013) 189–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Zhu X, Wang Y, Soaita I, Lee HW, Bae H, Boutagy N, Bostwick A, Zhang RM, Bowman C, Xu Y, Trefely S, Chen Y, Qin L, Sessa W, Tellides G, Jang C, Snyder NW, Yu L, Arany Z, Simons M, Acetate controls endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition, Cell metabolism 35(7) (2023) 1163–1178 e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hall IF, Kishta F, Xu Y, Baker AH, Kovacic JC, Endothelial to mesenchymal transition: at the axis of cardiovascular health and disease, Cardiovasc Res 120 (3) (2024) 223–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Liu J, Jin J, Liang T, Feng XH, To Ub or not to Ub: a regulatory question in TGF-beta signaling, Trends Biochem. Sci 47 (12) (2022) 1059–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Rape M, Ubiquitylation at the crossroads of development and disease, Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 19 (1) (2018) 59–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Qian G, Xu L, Qin J, Huang H, Zhu L, Tang Y, Li X, Ma J, Ma Y, Ding Y, Lv H, Leukocyte proteomics coupled with serum metabolomics identifies novel biomarkers and abnormal amino acid metabolism in Kawasaki disease, J Proteomics 239 (2021) 104183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Colleran A, Collins PE, O’Carroll C, Ahmed A, Mao X, McManus B, Kiely PA, Burstein E, Carmody RJ, Deubiquitination of NF-kappaB by Ubiquitin-Specific Protease-7 promotes transcription, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110 (2) (2013) 618–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Xue Q, Yang D, Zhang J, Gan P, Lin C, Lu Y, Zhang W, Zhang L, Guang X, USP7, negatively regulated by miR-409–5p, aggravates hypoxia-induced cardiomyocyte injury, APMIS 129 (3) (2021) 152–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Tang LJ, Zhou YJ, Xiong XM, Li NS, Zhang JJ, Luo XJ, Peng J, Ubiquitin-specific protease 7 promotes ferroptosis via activation of the p53/TfR1 pathway in the rat hearts after ischemia/reperfusion, Free Radic. Biol. Med. 162 (2021) 339–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Gong X, Li Y, He Y, Zhou F, USP7-SOX9-miR-96–5p-NLRP3 Network Regulates Myocardial Injury and Cardiomyocyte Pyroptosis in Sepsis, Hum Gene Ther 33 (19–20) (2022) 1073–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Bhattacharya S, Chakraborty D, Basu M, Ghosh MK, Emerging insights into HAUSP (USP7) in physiology, cancer and other diseases, Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 3 (2018) 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Yuan Y, Miao Y, Zeng C, Liu J, Chen X, Qian L, Wang X, Qian F, Yu Z, Wang J, Qian G, Fu Q, Lv H, Zheng H, Small-molecule inhibitors of ubiquitin-specific protease 7 enhance type-I interferon antiviral efficacy by destabilizing SOCS1, Immunology 159 (3) (2020) 309–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Basu B, Karmakar S, Basu M, Ghosh MK, USP7 imparts partial EMT state in colorectal cancer by stabilizing the RNA helicase DDX3X and augmenting Wnt/beta-catenin signaling, Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 1870 (4) (2023) 119446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kon N, Kobayashi Y, Li M, Brooks CL, Ludwig T, Gu W, Inactivation of HAUSP in vivo modulates p53 function, Oncogene 29 (9) (2010) 1270–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Murata H, Experimental candida-induced arteritis in mice, Relation to Arteritis in the Mucocutaneous Lymph Node Syndrome, Microbiol Immunol 23 (9) (1979) 825–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Jia C, Zhang J, Chen H, Zhuge Y, Chen H, Qian F, Zhou K, Niu C, Wang F, Qiu H, Wang Z, Xiao J, Rong X, Chu M, Endothelial cell pyroptosis plays an important role in Kawasaki disease via HMGB1/RAGE/cathespin B signaling pathway and NLRP3 inflammasome activation, Cell Death Dis 10 (10) (2019) 778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Altun M, Kramer HB, Willems LI, McDermott JL, Leach CA, Goldenberg SJ, Kumar KG, Konietzny R, Fischer R, Kogan E, Mackeen MM, McGouran J, Khoronenkova SV, Parsons JL, Dianov GL, Nicholson B, Kessler BM, Activity-based chemical proteomics accelerates inhibitor development for deubiquitylating enzymes, Chem Biol 18 (11) (2011) 1401–1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Suganuma E, Sato S, Honda S, Nakazawa A, A novel mouse model of coronary stenosis mimicking Kawasaki disease induced by Lactobacillus casei cell wall extract, Exp. Anim. 69 (2) (2020) 233–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Justus CR, Marie MA, Sanderlin EJ, Yang LV, Transwell In Vitro Cell Migration and Invasion Assays, Methods Mol Biol 2644 (2023) 349–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Price GM, Tien J, Methods for forming human microvascular tubes in vitro and measuring their macromolecular permeability, Methods Mol Biol 671 (2011) 281–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Miranda AMA, Janbandhu V, Maatz H, Kanemaru K, Cranley J, Teichmann SA, Hubner N, Schneider MD, Harvey RP, Noseda M, Single-cell transcriptomics for the assessment of cardiac disease, Nat Rev Cardiol 20 (5) (2023) 289–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Porritt RA, Zemmour D, Abe M, Lee Y, Narayanan M, Carvalho TT, Gomez AC, Martinon D, Santiskulvong C, Fishbein MC, Chen S, Crother TR, Shimada K, Arditi M, Noval Rivas M, NLRP3 Inflammasome Mediates Immune-Stromal Interactions in Vasculitis, Circ. Res. 129 (9) (2021) e183–e200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kalucka J, de Rooij L, Goveia J, Rohlenova K, Dumas SJ, Meta E, Conchinha NV, Taverna F, Teuwen LA, Veys K, Garcia-Caballero M, Khan S, Geldhof V, Sokol L, Chen R, Treps L, Borri M, de Zeeuw P, Dubois C, Karakach TK, Falkenberg KD, Parys M, Yin X, Vinckier S, Du Y, Fenton RA, Schoonjans L, Dewerchin M, Eelen G, Thienpont B, Lin L, Bolund L, Li X, Luo Y, Carmeliet P, Single-Cell Transcriptome Atlas of Murine Endothelial Cells, Cell 180 (4) (2020) 764–779 e20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Bondareva O, Rodriguez-Aguilera JR, Oliveira F, Liao L, Rose A, Gupta A, Singh K, Geier F, Schuster J, Boeckel JN, Buescher JM, Kohli S, Kloting N, Isermann B, Bluher M, Sheikh BN, Single-cell profiling of vascular endothelial cells reveals progressive organ-specific vulnerabilities during obesity, Nat Metab 4 (11) (2022) 1591–1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Love MI, Huber W, Anders S, Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2, Genome Biol 15 (12) (2014) 550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Majolee J, Kovacevic I, Hordijk PL, Ubiquitin-based modifications in endothelial cell-cell contact and inflammation, J Cell Sci 132 (17) (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Wang B, Cai W, Ai D, Zhang X, Yao L, The Role of Deubiquitinases in Vascular Diseases, J Cardiovasc Transl Res 13 (2) (2020) 131–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].He M, Chen Z, Martin M, Zhang J, Sangwung P, Woo B, Tremoulet AH, Shimizu C, Jain MK, Burns JC, Shyy JY, miR-483 Targeting of CTGF Suppresses Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition: Therapeutic Implications in Kawasaki Disease, Circ. Res. 120 (2) (2017) 354–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Ni C, Qiu H, Zhang S, Zhang Q, Zhang R, Zhou J, Zhu J, Niu C, Wu R, Shao C, Mamun AA, Han B, Chu M, Jia C, CircRNA-3302 promotes endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition via sponging miR-135b-5p to enhance KIT expression in Kawasaki disease, Cell Death Discov 8 (1) (2022) 299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Huang C, Wang W, Huang H, Jiang J, Ding Y, Li X, Ma J, Hou M, Pu X, Qian G, Lv H, Kawasaki disease: ubiquitin-specific protease 5 promotes endothelial inflammation via TNFalpha-mediated signaling, Pediatr Res 93 (7) (2023) 1883–1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Pozhidaeva A, Bezsonova I, USP7: Structure, substrate specificity, and inhibition, DNA Repair 76 (2019) 30–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Nie L, Wang C, Liu X, Teng H, Li S, Huang M, Feng X, Pei G, Hang Q, Zhao Z, Gan B, Ma L, Chen J, USP7 substrates identified by proteomics analysis reveal the specificity of USP7, Genes Dev 36 (17–18) (2022) 1016–1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Zhang T, Periz G, Lu YN, Wang J, USP7 regulates ALS-associated proteotoxicity and quality control through the NEDD4L-SMAD pathway, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117 (45) (2020) 28114–28125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Huang YT, Cheng AC, Tang HC, Huang GC, Cai L, Lin TH, Wu KJ, Tseng PH, Wang GG, Chen WY, USP7 facilitates SMAD3 autoregulation to repress cancer progression in p53-deficient lung cancer, Cell Death Dis 12 (10) (2021) 880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Yuan S, Wang Z, Yao S, Wang Y, Xie Z, Wang J, Yu X, Song Y, Cui X, Zhou J, Ge J, Knocking out USP7 attenuates cardiac fibrosis and endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition by destabilizing SMAD3 in mice with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, Theranostics 14 (15) (2024) 5793–5808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Lee AM, Shimizu C, Oharaseki T, Takahashi K, Daniels LB, Kahn A, Adamson R, Dembitsky W, Gordon JB, Burns JC, Role of TGF-beta Signaling in Remodeling of Noncoronary Artery Aneurysms in Kawasaki Disease, Pediatr Dev Pathol 18 (4) (2015) 310–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Shimizu C, Kim J, He M, Tremoulet AH, Hoffman HM, Shyy JY, Burns JC, RNA Sequencing Reveals Beneficial Effects of Atorvastatin on Endothelial Cells in Acute Kawasaki Disease, J Am Heart Assoc 11 (14) (2022) e025408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]