Abstract

Cryptococcus neoformans is an opportunistic fungal pathogen with a defined sexual cycle involving fusion of haploid MATα and MATa cells. Virulence has been linked to the mating type, and MATα cells are more virulent than congenic MATa cells. To study the link between the mating type and virulence, we functionally analyzed three genes encoding homologs of the p21-activated protein kinase family: STE20α, STE20a, and PAK1. In contrast to the STE20 genes that were previously shown to be in the mating-type locus, the PAK1 gene is unlinked to the mating type. The STE20α, STE20a, and PAK1 genes were disrupted in serotype A and D strains of C. neoformans, revealing central but distinct roles in mating, differentiation, cytokinesis, and virulence. ste20α pak1 and ste20a pak1 double mutants were synthetically lethal, indicating that these related kinases share an essential function. In summary, our studies identify an association between the STE20α gene, the MATα locus, and virulence in a serotype A clinical isolate and provide evidence that PAK kinases function in a MAP kinase signaling cascade controlling the mating, differentiation, and virulence of this fungal pathogen.

Cryptococcus neoformans is a pathogenic fungus that infects the central nervous system in immunocompromised individuals (7). This heterothallic basidiomycete is distributed worldwide and has evolved into four distinct serotypes (A, B, C, and D), all of which infect humans and which have been classified into three different varieties. Serotypes A (Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii) and D (Cryptococcus neoformans var. neoformans) are distributed worldwide in association with pigeon droppings; cause the majority of infections in human immunodeficiency virus-infected and other immunocompromised hosts; and, based on population genetics studies, diverged from a common ancestor ∼18.5 million years ago (56).

C. neoformans has a defined sexual life cycle involving haploid cells of MATα and MATa mating types (20, 21). Mating involves cell fusion and leads to the production of heterokaryotic hyphal filaments. The tips of the hyphal filaments differentiate to form basidia, in which nuclear fusion and meiosis occur, and long chains of basidiospores are then produced by budding from the basidia (2). In response to nitrogen starvation and mating pheromone, MATα strains, but not MATa strains, can also form filaments and sporulate by a process known as haploid or monokaryotic fruiting (53, 55). The basidiospores produced by mating or fruiting may represent the infectious propagules (47), which are inhaled and then spread as yeast cells via the bloodstream to infect the brain.

The MATα mating type has also been linked to virulence in C. neoformans. MATα strains are more prevalent in the environment, most clinical isolates are MATα, and MATα strains are more virulent than congenic MATa strains in animal models (22, 23).

The MATα locus was previously identified and found to contain two mating-type-specific genes: MFα1 and STE12α. The MFα1 gene encodes a mating pheromone that stimulates conjugation tube formation, cell fusion, and mating (11, 37; W.-C. Shen, R. C. Davidson, G. M. Cox, and J. Heitman, submitted for publication). The STE12α gene encodes a homolog of the Ste12/Cph1 transcription factor that regulates mating, filamentation, or virulence in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida albicans (31-33, 54). Recent studies have revealed that the MAP kinase cascade that controls mating in C. neoformans is composed of both mating-type-specific and nonspecific components. For example, the G protein β subunit Gpb1 (52, 53) and the MAP kinase Cpk1 (R. C. Davidson, G. M. Cox, J. R. Perfect, and J. Heitman, submitted for publication) are not mating type specific, whereas mating-type-specific elements include the MEK kinase Ste11α (9) and the recently identified p21-activated protein kinase (PAK) homologs Ste20α and Ste20a (30).

The PAK family of protein kinases is conserved from yeast to humans, and its members play central roles in cell signaling and development as effectors of Rho-type p21 GTPases (10, 14, 24, 34). PAK kinases share a highly conserved C-terminal catalytic domain and a CRIB (for Cdc42-Rac interactive binding) regulatory domain. In addition, the Cla4 and Cla4-like kinases contain an amino-terminal pleckstrin homology (PH) domain. PH domains mediate binding to membrane phosphoinositides and may also interact with proteins (29). In the ascomycetous yeasts S. cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe, the PAK kinases Ste20 and Cla4 (Shk1/Pak1 and Shk2/Pak2 in S. pombe) act as effectors of the Cdc42 GTPase and regulate mating, the cell cycle, and morphogenesis, in part by activating MAP kinase signaling (12, 17). In other fungi, PAK kinases have been linked to virulence (C. albicans), hyphal maturation (Ashbya gossypii), and filamentation (C. albicans and Yarrowia lipolytica) (5, 18, 25, 27, 48).

We have identified three PAK kinase homologs, Ste20α, Ste20a, and Pak1, in C. neoformans. Interestingly, we recently showed that the STE20 genes reside in the mating-type loci; therefore, the STE20 gene exists as two mating-type-specific alleles, STE20α and STE20a, which are related but divergent (30). In contrast, we find that the third PAK kinase homolog, Pak1, is not mating type specific. Mutations in the serotype A STE20α gene resulted in a modest defect in mating, defects in cytokinesis and growth at 39°C, and attenuated virulence. Serotype D ste20α and ste20a mutants exhibited a similar cytokinesis defect; however, they grew normally at 37°C and were fully virulent. ste20 mutants were sterile in bilateral crosses. Mutations in the PAK1 gene also conferred defects in mating and haploid differentiation but did not affect growth or cytokinesis. pak1 mutant strains of both serotypes A and D were attenuated for virulence. ste20α pak1 and ste20a pak1 strains were inviable, indicating that these mutant combinations are synthetically lethal. Taken together, our studies reveal that the Ste20 and Pak1 kinases share an overlapping essential function but also have distinct roles in mating, differentiation, cytokinesis, and virulence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, media, and biolistic transformation of C. neoformans.

The C. neoformans serotype A strains H99 (MATα), M049 (H99 ade2), and F99 (H99 ura5) and the congenic serotype D MATa and MATα strains JEC20 and JEC21 and their auxotrophic derivatives have been described (37, 46, 53) and are listed in Table 1. Yeast-peptone-dextrose (YPD) and yeast nitrogen base media, synthetic (SD) medium, V8 agar for mating, filament agar, Niger seed for melanin production, low-iron medium plus 56 μM ethylenediamine-di(o-hydroxyphenylacetic acid), and serum-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium for capsule induction were prepared as previously reported (3, 15, 50). Biolistic transformations were conducted using established methods (49). Transformants were selected on SD medium lacking adenine or uracil and containing 1 M sorbitol.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Serotype A | ||

| H99 | MATα | 42 |

| M049 | MATα ade2 | 42 |

| F99 | MATα ura5 | 51 |

| PPW54 | ste20α::ADE2 ade2 | This study |

| PPW55 | ste20α::ADE2 ade2 ura5 | This study |

| PPW63 | ste20α::ADE2 ura5 STE20α + URA5 | This study |

| PPW91 | ste20α::URA5 ura5 | This study |

| PPW96 | ste20α::ura5 ura5 | This study |

| PPW151 | ste20α::ura5 STE20α + URA5 | This study |

| CSB1 | pak1::URA5 ura5 | This study |

| CSB2 | pak1::ura5 ura5 | This study |

| CSB3 | PAK1 ura5 ura5 | This study |

| Serotype D | ||

| JEC20 (B-4476) | MATa | 23 |

| JEC21 (B-4500) | MATα | 23 |

| JEC34 | MATaura5 | J. Edman |

| JEC43 | MATα ura5 | J. Edman |

| JEC50 | MATα ade2 | J. Edman |

| JEC155 | MATα ura5 ade2 | J. Edman |

| JEC156 | MATaura5 ade2 | J. Edman |

| CSB5 | MATaste20a::ADE2 ade2 | This study |

| CSB7 | MATα ste20α::URA5 ura5 | This study |

| CSB8 | MATα pak1::URA5 ade2 ura5 | This study |

| CSB9 | MATα pak1::URA5 ura5 | This study |

| CSB10 | MATapak1::URA5 ura5 | This study |

| CSB12 | MATα ste20α::URA5 ade2 ura5 | This study |

| CSB23 | MATα pak1::ura5 ura5 | This study |

| CSB48 | MATα ste20α::ura5 ura5 | This study |

| KBL156-1 | MATaste20a::ADE2 ade2 ura5 | This study |

Molecular biology and microscopy.

C. neoformans genomic DNA for Southern hybridization analysis was isolated as described previously (42). Rapid DNA extraction from multiple samples for PCRs were done by the methods of Hoffman and Winston (16). Standard PCR amplification reactions were performed with either ExTaq polymerase (Takara Shuzo Co., Ltd.) or PCR Supermix High Fidelity (Gibco BRL) using the following parameters: 94°C, 30 s; 55°C, 30 s; 72°C, 4 min. All nucleic acid manipulations were performed using standard procedures (45). DNA sequences were analyzed with Editseq (DNA Star), Align (DNA Star), or MacVector (Oxford Molecular).

Differential interference contrast (DIC) and fluorescence microscopy were performed on a Nikon Optiphot-2 microscope, and images were captured using a Diagnostic Instruments Spot RT digital camera and documented with Adobe Photoshop software. For F-actin staining, cells were fixed in 1/4 volume 37% formaldehyde for 20 min, washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), permeabilized with 1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min, and washed three times with PBS. To visualize F-actin, aliquots of fixed cells were incubated in rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin (P-1951; Sigma) for 2 h to overnight. Capsules were visualized by staining cells with India ink. All other images were captured using a Nikon digital camera (Coolpix 990).

Isolation of the C. neoformans STE20/PAK genes.

Degenerate primers, 5′-GTNGCNATTAARCARATG (2090) and 5′-YTCNGGNGCCATCCARTA (2092), were used to amplify a partial clone of the STE20 kinase gene by PCR using the following parameters: 94°C, 40 s; 39°C, 1 min; 72°C, 1 min; 40 cycles. C. neoformans cDNA from H99 (200 ng) was used as the template. A 420-bp PCR product of the expected sizes was excised, cloned, verified by sequencing, and used as a probe to isolate the corresponding genomic locus. Genomic DNA from strains H99, JEC20, and JEC21 was also used in touchdown PCR amplification with the same primer set and the following parameters: 94°C, 30 s; 60°C with a temperature increment of −1°C every cycle for 20 cycles, 1 min; 72°C, 45 s; and an additional 20 cycles of 94°C, 30 s; 40°C, 1 min; and 72°C, 45 s (see also reference 30).

Open reading frames containing the serotype A STE20α and PAK1 genes were isolated on 9-kb HindIII and 11-kb EcoRI-PstI fragments, respectively, from serotype A (H99) size-selected DNA libraries. Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR and 5′ and 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) (Gibco BRL) were performed to verify predicted intron-exon junctions and to determine transcription initiation and polyadenylation sites. Similar methods were employed to isolate and characterize the serotype D STE20α gene from a serotype D (JEC21) size-selected DNA library. The STE20a gene was previously isolated as a 2.5-kb PstI fragment from a partial library of the serotype D JEC20 strain (30). The serotype D PAK1 gene was identified in sequence traces generated by the Stanford Genome Technology Center Cryptococcus neoformans Genome Project. Primers based on the predicted sequence were used to amplify and sequence the PAK1 open reading frame from serotype D JEC21 genomic DNA. Predicted intron-exon junctions were confirmed by amplification of the PAK1 sequence from a JEC21 cDNA library.

Generation of STE20 and PAK1 disruption mutants.

To disrupt the STE20α gene in serotype A, two different disruption alleles, ste20α::ADE2 and ste20α::URA5, were constructed by inserting the ADE2 or URA5 gene at a unique HpaI site within the coding region. Primers 5′-AGGACATCTATAGCAGAT (2578) and 5′-CGTAAAGGTAACTAACTT (2579) were used to amplify the ste20α disruption allele, which was used to transform strain M049, or following SnaBI digestion to transform strain F99, generating strains PPW54 (ste20α::ADE2) (6 out of 132 Ade+ isolates) and PPW91 (ste20α::URA5) (5 out of 32 Ura+ isolates). To disrupt the serotype D STE20α gene, the URA5 gene was inserted at a unique BglII site within the coding region to generate a ste20α::URA5 disruption allele. Similarly, the ADE2 gene was inserted at a unique EcoRV site within the coding region of the serotype D STE20a gene. The ste20α::URA5 and ste20a::ADE2 alleles were transformed into strain JEC155 (MATα ura5 ade2) or JEC156 (MATa ura5 ade2), respectively, generating strains CSB12 (MATα ste20α::URA5 ura5 ade2) (16%) and KBL156-1 (MATa ste20a::ADE2 ade2 ura5) (8 out of 79).

pak1 mutant strains in serotypes A (CSB1) and D (CSB8) were generated by inserting the URA5 marker gene into a conserved and unique NcoI site in the N-terminal region. The resulting pak1::URA5 serotype A and D disruption alleles were transformed into the serotype A ura5 strain F99 and the serotype D ura5 ade2 strain JEC155 to yield pak1 mutant strains at 12.5 and 5%, respectively.

Reconstitution of the serotype A ste20α mutant strains was accomplished by first generating ura5 mutant versions by selection on 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) medium. These ura5 strains were then transformed with the STE20α gene physically linked to the C. neoformans URA5 gene, generating strain PPW151 (ste20α::ura5 STE20α URA5). Similarly, the ste20α::ADE2 ura5 STE20α URA5 reconstituted strain (strain PPW63) was also constructed. Reconstitution of the serotype A pak1::URA5 mutant strain was achieved by transformation with the wild-type PAK1 gene and incubation on 5-FOA medium, selecting for integration of PAK1 at the endogenous locus. Finally, the newly reconstituted PAK1 ura5 strain (CSB2) was transformed with the URA5 gene to restore Ura+ protrophy, generating strain CSB3. For all deletions and reconstitutions, transformants were screened by PCR and confirmed by Southern hybridization analysis.

Mating, haploid differentiation, melanin, and capsule formation.

The mating competence of the PAK mutant strains was determined by crossing each strain to a tester strain of the opposite mating type. Crosses were prepared by growing the strains overnight in YPD medium at 30°C to 107 cells/ml, mixing together 200 μl of each mating pair, and spotting 5 μl of each mating mixture onto V8 agar medium. Similarly, mutant strains were tested for filamentation; the strains were grown in YPD medium overnight at 30°C to 107 cells/ml, 1 ml was washed and resuspended in 500 μl of H2O, and 5 μl of cells was spotted onto filament agar medium with 0.5% glucose (55). In confrontation tests, strains were streaked in a single straight line with the opposite mating partner in proximity without physical contact (53). For each assay, the plates were incubated at ambient temperature for a period of 2 (confrontation assays) to 14 (haploid fruiting) days in the dark and examined microscopically for basidiospore formation or filaments. Melanin production was examined by inoculating the strains onto Niger seed agar medium with incubation at 37°C for 3 days. Capsule was induced by incubating the strains in low-iron medium plus 56 μM ethylenediamine-di(o-hydroxyphenylacetic acid) for 1 week (50) or in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (15) for 3 days at 30°C.

Overexpression analysis and two-hybrid interactions.

C. neoformans plasmids expressing the GPB1 (pGAL7-GPB1), CPK1-1 (pGAL7-CPK1-1), and activated STE11α (pGPD-STE11α-1) genes were transformed into the serotype A ste20α::ADE2 ura5 (PPW55) mutant. The CPK1-1 allele is missing the final exon of 15 amino acids that spans sequences not conserved in other MAP kinases. ste20α::ADE2 ura5 GPB1, ste20α::ADE2 ura5 CPK1-1, and ste20α::ADE2 ura5 STE11α-1 transformants were mated to the ste20a::URA5 strain CSB5 on V8 mating agar medium for 7 days. C. neoformans plasmids expressing the STE12α (pGAL7-STE12), CPK1 (pGPD1-CPK1), and activated STE11α (pGPD1-STE11α-1) genes were transformed into serotype D MATα ste20::ura5 ura5 (CSB48) and pak1::ura5 ura5 (CSB23) strains. To test for filamentation, transformants were inoculated on filament agar containing 2% galactose or 0.5% glucose and incubated for 14 days at 24°C in the dark.

For two-hybrid interactions, the S. cerevisiae reporter strain PJ69-4A was cotransformed with plasmids pGBD-CDC42 and pGAD-STE20α, pGBD-CDC42 and pGAD-PAK1, pGBD-CDC42 and pGAD424, pGBT9 and pGAD-STE20α, pGBT9 and pGAD-PAK1, and pGBT9 and pGAD424. Transformants were selected on SD-Trp-Leu medium, and the transformed strains were tested on SD-Leu-Trp-Ade and SD-Trp-Leu-His plus 3-aminotriazol media. The C. neoformans CDC42 homolog was identified during sequencing of the 11-kb EcoRI fragment containing the serotype A PAK1 gene. Primers 5′-CAACTTAAGAGATCTTGCAG (5072) and 5′-ATATATGTCGACTAGAGGATC (5073) were used to amplify CDC42 cDNA by RT-PCR. The CDC42 cDNA was subcloned in frame to the 3′ end of GBD (pGBT9), which encodes the DNA binding domain of Gal4. Primers 5′-CGGGATCCACGACATCTATAGCAGATC (7339) and 5′-CGGGATCCCCAAAAGCTGATGCTGTGG (7340) were used to amplify cDNA containing the CRIB domain (corresponding to amino acids 164 to 327) of STE20α by RT-PCR. The Ste20α CRIB domain was subcloned in frame to the 3′ end of the Gal4 activation domain in plasmid pGAD424. Primers 5′-CGACCGCGGGGATCCAAAAGGGG (7242) and 5′-CTTCATCTCTGCAGATATTTCCTC (7243) were used to amplify cDNA containing the CRIB domain (amino acids 1 to 139) of PAK1 by RT-PCR. The PAK1 CRIB domain was subcloned in frame with the Gal4AD in plasmid pGAD424.

Genetic crosses.

To construct an ste20a::ADE2 prototrophic strain, strain KBL156-1 (MATa ste20a::ADE2 ura5 ade2) was crossed to JEC50 (MATα ade2), generating strain CSB5 (MATa ste20a::ADE2 ade2). ste20a::ADE2 URA5 recombinants were selected by plating the mating mixture onto SD-Ura-Ade medium. The presence of the ste20a::ADE2 mutation was detected by PCR analysis, by a mating defect, and by phenotype at 37°C. Similarly, a ste20α::URA5 prototrophic strain was constructed by crossing strain CSB12 (MATα ste20α::URA5 ade2 ura5) with JEC34 (MATa ura5), generating strain CSB7 (MATα ste20α::URA5 ura5).

MATα pak1::URA5 (CSB9) and MATa pak1::URA5 (CSB10) strains were constructed by crossing strain CSB8, the original MATα pak1::URA5 ade2 ura5 deletion strain, to strain JEC34 (MATa ura5) and selecting for MATa and MATα prototrophic meiotic segregants. The pak1::URA5 mutation in each of these strains was confirmed by PCR analysis.

The synthetic lethality of the ste20 and pak1 mutations was tested by analyzing basidiospores from crosses between strains CSB8 (MATα pak1::URA5 ade2 ura5) and KBL156-1 (MATa ste20a::ADE2 ade2 ura5) or strains CSB7 (MATα ste20α::URA5 ura5) and CSB10 (MATa pak1::URA5 ura5). After incubation on V8 mating medium for 7 to 14 days, the basidiospores were dissected by micromanipulation onto YPD agar medium and allowed to germinate at 25°C. The resulting colonies from the pak1::URA5 ade2 × ste20a::ADE2 ura5 cross were replica plated onto SD-Ura, SD-Ade, SD-Ura-Ade, and YPD media at 25 and 37°C to follow the segregation of ura5, ade2, and the ste20a mutation by its cytokinesis defect. Similarly, colonies from the ste20α::URA5 × pak1::URA5 cross were replica plated onto SD-Ura and YPD media at 25°C and onto YPD medium at 37°C. Genomic DNA was isolated from the progeny, and STE20α-, STE20a-, and PAK1-specific primers were used to determine the segregation of the STE20α, ste20α::URA5, PAK1, pak1::URA5, STE20a, and ste20a::ADE2 alleles by PCR. Additionally, each germinated colony was tested for mating type by crossing it to the tester strains JEC21 (MATα) and JEC20 (MATa) and the ste20 mutant strains.

Animal models of cryptococcal meningitis.

Virulence tests were performed using established rabbit and murine models of cryptococcal meningitis (3, 36, 39, 41, 53). Three or four male New Zealand White rabbits weighing 2.5 to 3 kg were administered either hydrocortisone acetate (2.5 mg/kg of body weight) or betamethasone acetate (0.15 mg/kg) intramuscularly 1 day prior to inoculation and then daily for the entire test period. One day after the initial steroid treatment, the animals were anesthetized with xylazine and ketamine intramuscularly and inoculated intracisternally with 0.3 ml of cell suspension (3 × 108/ml) for each strain. Rabbits were anesthetized on days 4, 7, and 10 following infection, and 500 μl of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was withdrawn, serially diluted, and plated onto YPD medium. The colonies were counted, and the mean number of CFU was plotted with the standard error of the mean indicated. A standard Student T test was performed to establish P values. The virulence test was performed twice and yielded similar results.

In the murine inhalation model, 50 μl containing 5 × 104 serotype A yeast cells was used to infect 10 4- to 6-week-old female A/Jcr mice (10 mice per strain) by nasal inhalation. The mice were anesthetized by phenobarbital injection, and yeast cells were then pipetted directly into the nostrils.

In the tail vein injection model, groups of 10 4- to 6-week-old female DBA mice obtained from National Cancer Institute/Charles River laboratories were directly injected in the lateral tail vein with 107 cells of the serotype D strains to be tested. The mice were monitored twice daily, and those that appeared to be sick or in pain were sacrificed by CO2 inhalation. The number of surviving mice was plotted against time, and P values were calculated by the Kruskal-Wallis test.

In addition, to examine cell morphology and capsule formation in vivo, mice infected with the serotype A strains H99, PPW91 (ste20α::URA5), PPW151 (ste20α STE20α), CSB1 (pak1::URA5), and CSB3 (reconstituted PAK1) were sacrificed 10 days after infection. Brain samples were harvested and examined microscopically for C. neoformans.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The GenBank accession numbers are as follows: STE20α (A), AF162330; STE20α (D), AF315635; STE20a (A), AF315636; STE20a (D), AF315638; PAK1 (A), AF391150; and PAK1 (D), AF391151.

RESULTS

Identification of C. neoformans PAK kinase homologs.

As previously described, the mating-type-specific PAK kinase homologs Ste20α and Ste20a were identified in C. neoformans by low-stringency PCR using primers designed for conserved catalytic regions (VAIKQM and YWMAPE). Here, we used the same PCR-based approach to identify a third PAK kinase homolog, which was named Pak1. The corresponding genes were cloned from both serotype A and serotype D strains (30) (see Materials and Methods). In total, six PAK kinase genes have been identified from four C. neoformans strains encompassing two varieties and both mating types.

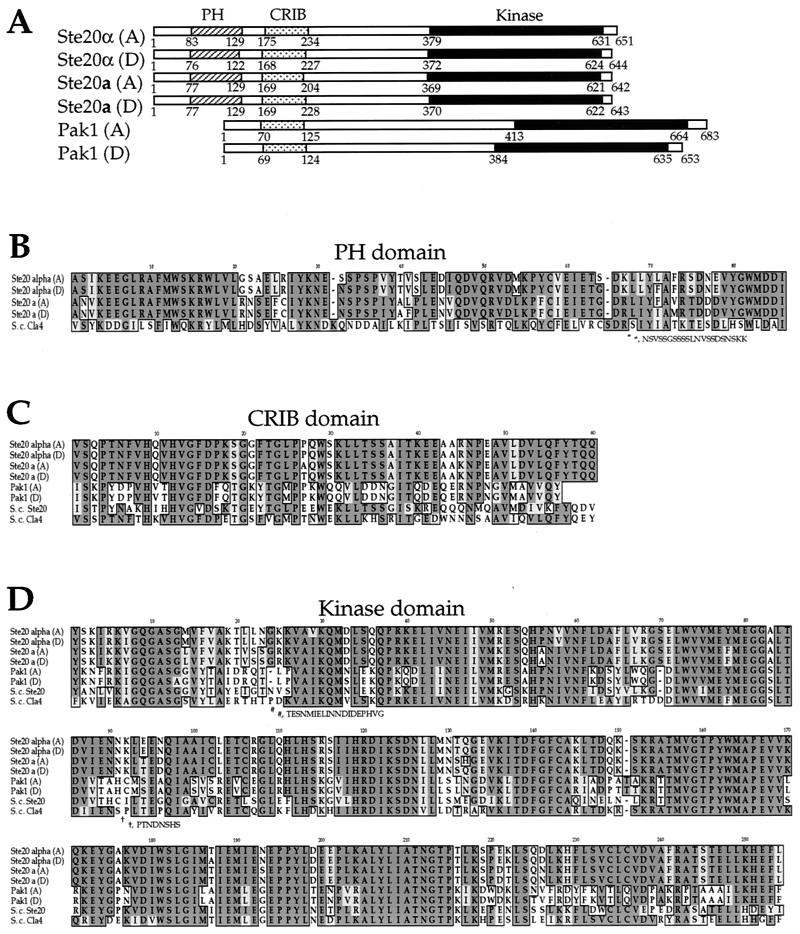

The PAK kinases are defined by two conserved domains: an N-terminal regulatory CRIB domain and a C-terminal catalytic domain. The Cryptococcus PAK kinases also contain these conserved domains (Fig. 1A, C, and D). For example, the serotype A Ste20α homolog has 48 to 53% identity in the CRIB domains and 57 to 61% identity in the catalytic domains with those of human PAK1, S. pombe Shk1p/Pak1p, and S. cerevisiae Cla4 and Ste20. As noted earlier, a subgroup of PAK kinases also contain a PH domain in the N terminus. Members of this subgroup include Cla4 from S. cerevisiae and Shk2p/Pak2p from S. pombe. In contrast to the previously described C. neoformans Ste20 kinases, the C. neoformans Pak1 kinase does not contain a PH domain (Fig. 1A and B).

FIG. 1.

C. neoformans PAK kinase homologs. (A) Predicted domain structures of the C. neoformans serotype A and D PAK kinases. Both the Ste20 and Pak1 kinases contain a CRIB domain (stippled boxes) and a kinase domain (solid boxes). In addition, the Ste20 kinases have an N-terminal PH domain (hatched boxes). (B) Amino acid sequence alignment of the C. neoformans Ste20 PH domains. S.c., S. cerevisiae. (C) Amino acid sequence alignment of the CRIB domains of the C. neoformans Ste20 and Pak1 kinases with S. cerevisiae Ste20 and Cla4 kinase CRIB domains. (D) Amino acid sequence alignment of the kinase domains of C. neoformans and S. cerevisiae PAK kinase catalytic domains. For panels B to D, identical amino acids are boxed and darkly shaded, and conservative substitutions are lightly shaded.

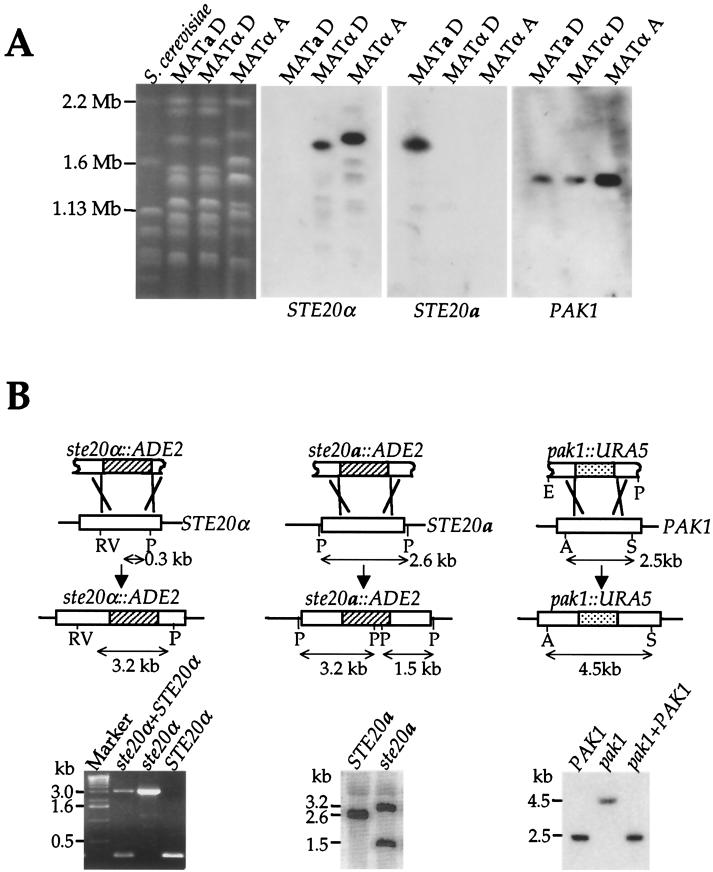

In contrast to the STE20 genes, the PAK1 gene is present in both MATα and MATa cells and is located on a different chromosome than the mating-type locus. First, in Southern blotting, a PAK1 gene probe hybridized to identical DNA fragments from the congenic serotype D strains JEC20 and JEC21 (not shown). When chromosomes from MATα and MATa strains were separated by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, the STE20 gene-specific probes hybridized to the 1.8-Mb chromosome from their respective mating types (Fig. 2A), as reported previously (30). In contrast, PAK1 gene probes hybridized to a smaller, ∼1.4-Mb chromosome, indicating the PAK1 gene is not linked to the mating-type locus (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

Mapping and disruption of the STE20α, STE20a, and PAK1 genes. (A) Chromosomes from the serotype A wild-type MATα (H99) and serotype D wild-type MATa and MATα (JEC20 and JEC21) strains were separated on CHEF gels (30). The gels were stained with ethidium bromide (left), transferred to nitrocellulose, and sequentially probed with the STE20α, STE20a, and PAK1 genes. S. cerevisiae chromosomes served as size markers. (B) Schematic representation of the STE20α, STE20a, and PAK1 gene disruptions. Gene-specific primers flanking the inserted ADE2 and URA5 marker genes were used to amplify genomic DNA from the wild-type (H99), ste20α mutant (PPW54), and ste20α STE20α reconstituted (PPW63) strains. Southern hybridization analysis with the STE20a and PAK1 genes as probes was used to verify the genotypes of the STE20a wild-type and ste20a mutant strains (JEC20 and KBL156-1) and of the PAK1 wild-type (H99), pak1 mutant (CSB1), and PAK1 reconstituted (CSB3) strains. The pak1 mutant strain was reconstituted by replacing the pak1::URA5 allele with the wild-type PAK1 gene, resulting in the reappearance of the 2.5-kb wild-type PAK1 fragment. Restriction sites are as follows: A, ApaI; RV, EcoRV; P, PstI; E, EcoRI; S, SmaI.

Disruption of the C. neoformans STE20α, STE20a, and PAK1 genes.

To establish the respective functions of the PAK kinase homologs Ste20α, Ste20a, and Pak1 in C. neoformans, serotype- and/or mating-type-specific disruption mutations were generated for each gene by inserting the ADE2 or URA5 marker gene into a unique restriction site in the N-terminal half of the gene (Fig. 2B) (see Materials and Methods). Linear DNA containing each gene disruption allele was biolistically transformed into auxotrophic serotype A or D recipient strains, and the efficiency of obtaining mutant strains was within the range of 5 to 16%. By this approach, ste20α and pak1 mutations were obtained in the serotype A strain H99, and ste20α, ste20a, and pak1 mutations were isolated in the congenic serotype D strains (JEC21 and JEC20). Thus, neither Ste20 nor Pak1 is essential in C. neoformans in either serotype or mating type.

We took three approaches to ensure that the observed phenotypes resulted from the introduced gene disruptions. First, reconstituted strains were constructed by two methods. Either a wild-type copy of the original gene with a physically linked marker (e.g., STE20α URA5) was introduced ectopically, or the disrupted allele was replaced with the wild-type gene at the endogenous locus by recombination and replacement of the integrated URA5 marker and selection for growth on 5-FOA medium (PAK1). Second, in all cases, multiple independent mutants were obtained and tested to ensure common phenotypes. Third, for serotype D strains, genetic crosses were conducted to establish whether the mutant phenotypes were linked to the gene disruption.

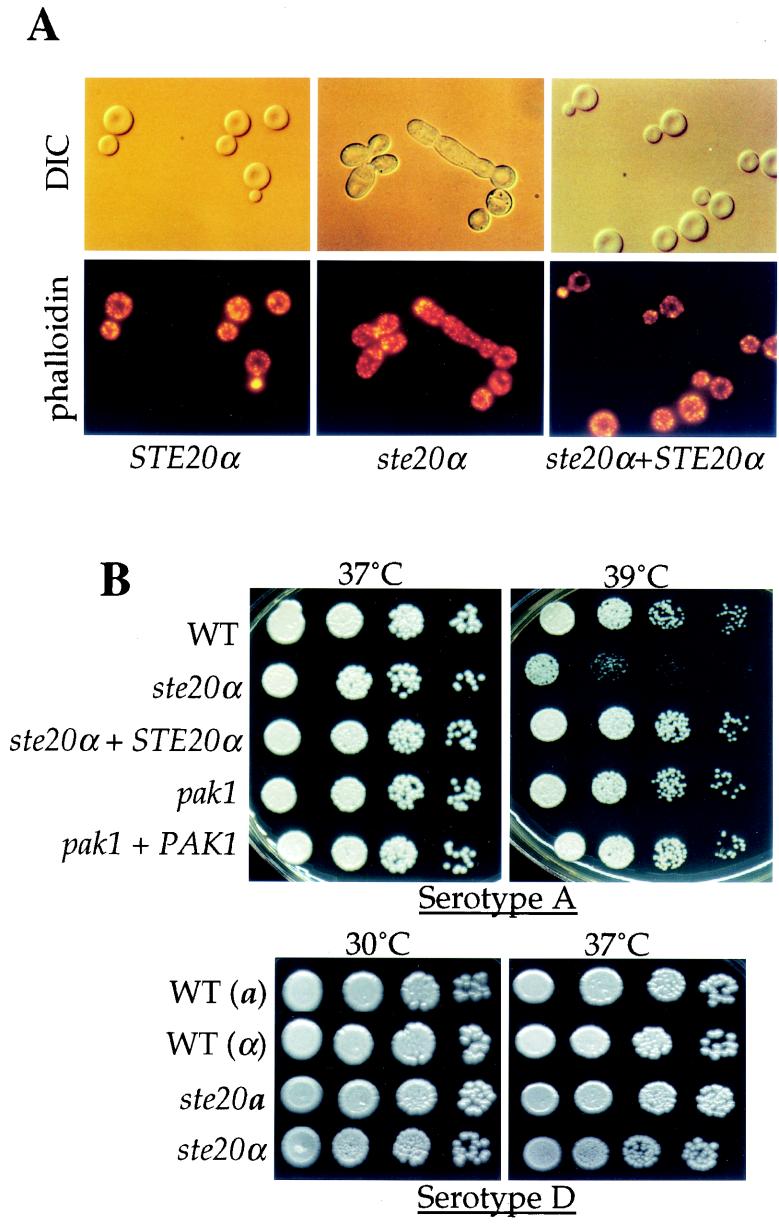

ste20 mutants exhibit cytokinesis and temperature-sensitive growth defects.

Because S. cerevisiae mutants lacking the PAK kinase Cla4 exhibit a cytokinesis defect, we examined whether ste20 or pak1 mutations confer a similar phenotype in C. neoformans. Whereas pak1 mutants showed no obvious cytokinesis defect, microscopic examination revealed that cells from each of the ste20 mutants exhibited an altered cell morphology at elevated temperature, consistent with defects in polarity establishment and cytokinesis. Wild-type C. neoformans strains typically grow as budding yeast. In contrast, ste20 mutant cells formed elongated buds that failed to separate, and abnormally wide mother-bud necks were frequently observed (Fig. 3A). Cell shape in C. neoformans is maintained by an actin cytoskeleton, and F-actin dynamics are similar in S. cerevisiae and C. neoformans (19). F-actin localization was compared in wild-type, ste20α mutant, and ste20α STE20α reconstituted strains grown at 39°C. In cells from each strain, the F-actin cytoskeleton was visualized as discrete patches and cables, culminating in the formation of a cap structure in small buds that had not yet undergone the apical-to-isotropic growth switch. However, F-actin remained polarized to the tips of elongated ste20α mutant buds, indicating a defect in the switch from polar to isotropic growth (Fig. 3A). Similar cytokinesis defects were observed with the serotype D ste20α and ste20a mutants (not shown). Taken together, these results suggest that, similar to Cla4 in S. cerevisiae, the C. neoformans Ste20 PAK kinases have a conserved role in cell polarity and cytokinesis.

FIG. 3.

ste20α mutants exhibit defects in cytokinesis and a serotype-specific growth defect at 39°C. (A) Mutation of the STE20α kinase gene confers a cytokinesis defect. Serotype A MATα STE20α wild-type (H99), ste20α mutant (PPW54), and ste20α STE20α reconstituted (PPW63) strains were grown in YPD medium for 24 h at 30°C and then shifted to 39°C for 4 h. The cells were fixed and stained with rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin to visualize actin (bottom row) or visualized by DIC microscopy (top row). The cells were photographed at ×1,000 magnification. (B) Serotype A ste20 mutants (top) but not serotype D ste20 mutants (bottom) exhibit temperature-sensitive growth. The wild-type (H99) (WT), ste20α mutant (PPW54), ste20α STE20α reconstituted (PPW63), pak1 mutant (CSB1), and PAK1 reconstituted (CSB3) strains were grown overnight at 30°C, counted, serially diluted (10-fold), inoculated as 5-μl aliquots on YPD medium, and incubated at 30, 37, or 39°C for 60 h. The isogenic serotype D strains were JEC20 [WT (a)], JEC21 [WT (α)], CSB5 (ste20a), and CSB7 (ste20α).

The ste20α mutation was also found to confer a temperature-sensitive growth defect in serotype A strains. Because the cytokinesis and cell polarity defects of the ste20 mutants were more severe at higher growth temperatures, we tested whether these defects had an impact on cell viability. The serotype A and D ste20 and pak1 mutants and reconstituted strains were analyzed by serial dilution spotting assays at different temperatures. This analysis revealed that the serotype A ste20α mutants are viable at 30 or 37°C but inviable at 39°C (Fig. 3B). This temperature-sensitive growth defect was observed in multiple independent mutants with two different ste20α disruption alleles and was complemented by reintroduction of the wild-type STE20α gene (Fig. 3B and not shown). No growth defect was observed for the serotype A pak1 mutant at 39°C (Fig. 3B). Similarly, no growth defect was observed with the serotype D ste20α, ste20a, and pak1 mutants at 37°C, the maximal growth temperature for these congenic serotype D strains (Fig. 3B). Differences in the sequence or function of Ste20 could be one mechanism that contributes to the higher maximal growth temperature of the serotype A strain H99 compared to the congenic serotype D strains.

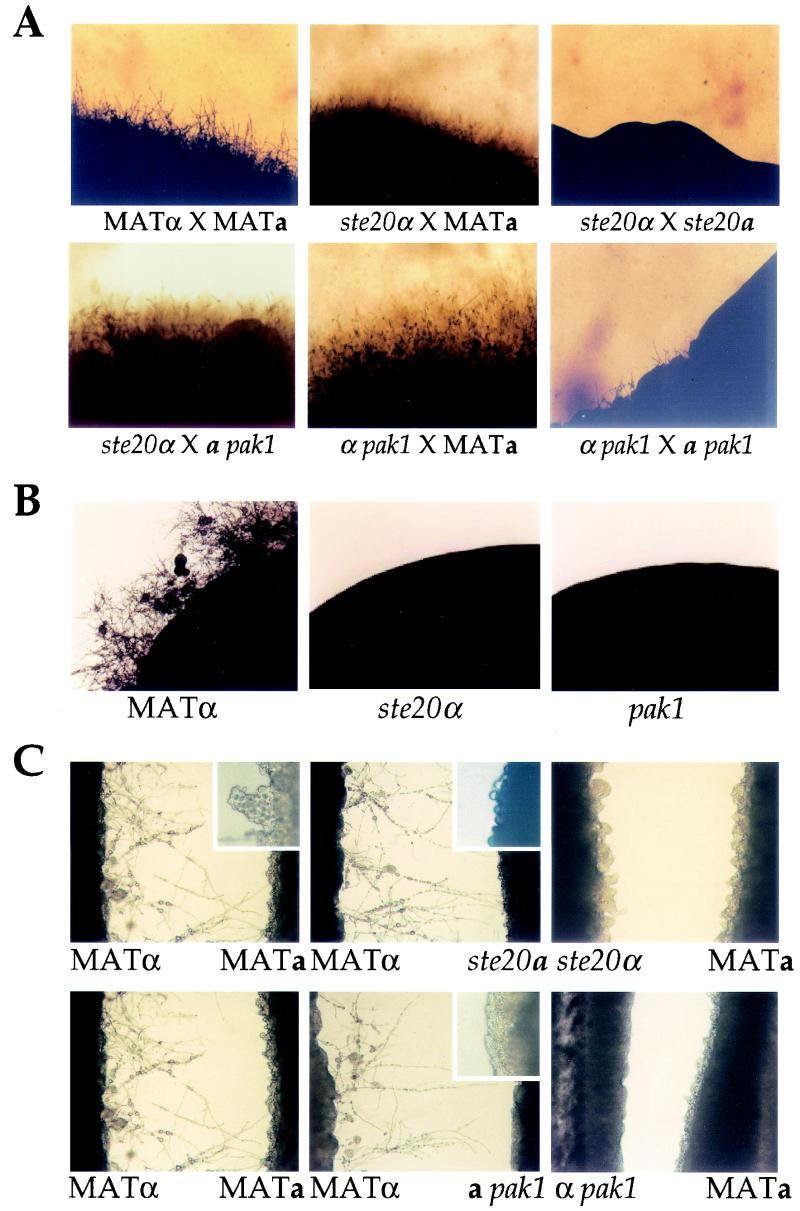

PAK kinases function in C. neoformans mating.

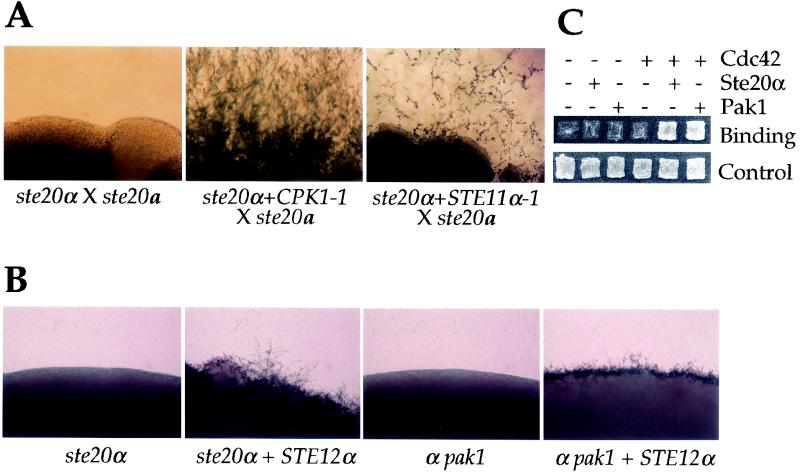

Based on previous studies of model yeasts, we hypothesized that the C. neoformans PAK kinases would have a role in mating and filamentation. Mating assays were conducted by coincubating prototrophic serotype D wild-type and mutant strains of opposite mating types on V8 mating medium. Under these conditions, wild-type mating partner cells fuse, and the resulting heterokaryons produce abundant heterokaryotic filaments, basidia, and basidiospores within 2 to 3 days (Fig. 4A). Similarly, abundant filamentation and basidiospore production were also observed when ste20 or pak1 mutants were crossed to wild-type strains (unilateral crosses) (Fig. 4 and data not shown). In contrast, in bilateral crosses (ste20α × ste20a and α pak1 × a pak1) no filamentation was observed after 3 days and only the α pak1 × a pak1 mating exhibited residual filaments at 7 days (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, in the ste20 bilateral mutant matings, some filaments could be observed 1 day after mating. However, these filaments were much shorter (“stubby”) than those observed in wild-type matings, exhibited extensive branching, and were quickly overgrown by vegetative cells (not shown). Although ste20α and ste20a mutants were mating defective with each other, both mated normally with pak1 mutant strains (Fig. 4A and data not shown). These findings implicate Ste20 and Pak1 as playing important roles in mating, most likely involving filamentation following cell fusion.

FIG.4.

Ste20α and Pak1 kinases function in mating and haploid fruiting. (A) Isogenic serotype D MATα wild-type (JEC21), ste20α mutant (CSB7), and α pak1 mutant (CSB9) strains were each mixed with a wild-type MATa (JEC20), ste20a mutant (CSB5), or MATa pak1 (CSB10) strain and incubated on V8 mating medium for 7 days at 24°C. The edges of mating patches were photographed at ×40 final magnification in all images. (B) Isogenic serotype D MATα wild-type (JEC21), ste20α (CSB7), and α pak1 (CSB9) mutant strains were incubated on filament agar for 14 days at 24°C in the dark, and the edges of growth patches were photographed at ×40 final magnification. (C) Congenic serotype D wild-type, ste20α, ste20a, and pak1 mutant strains of opposite mating types (JEC21, JEC20, CSB7, CSB5, CSB9, and CSB10) were grown in confrontation as lines of cells ∼2 mm apart on filament agar for 72 h at 24°C in the dark. The opposing interfaces were photographed at ×100 final magnification (×200 final magnification for the inserts).

PAK kinases are necessary for haploid fruiting.

In response to nitrogen deprivation and desiccation, haploid MATα strains undergo asexual filamentation and sporulation (haploid fruiting). We tested whether the C. neoformans PAK kinases play a role in haploid fruiting. The wild-type serotype D MATα strain underwent robust haploid fruiting when incubated on filament agar for 14 days, whereas the congenic ste20α and α pak1 mutant strains failed to form filaments and produced no basidia or basidiospores (Fig. 4B), indicating roles for both Ste20α and Pak1 in haploid fruiting.

Because haploid fruiting of MATα cells is enhanced by mating pheromones, one possible explanation for the inability of ste20α and α pak1 mutant strains to haploid fruit is a defect in pheromone sensing or response. To test this, confrontation assays were conducted by placing strains of opposite mating types in close proximity on filament agar. In response to MFa pheromone, MATα cells produce conjugation tubes and then haploid fruit, whereas MATa cells respond to MFα pheromone by producing abundant round and enlarged cells and relatively fewer conjugation tubes (Fig. 4C). These assays allow us to determine whether mutant strains produce and respond to mating pheromone. Wild-type MATα cells formed filaments and fruited in response to ste20a and a pak1 mutants (Fig. 4C), indicating that both mutants produce MFa pheromone. Similarly, wild-type MATa cells responded to ste20α or α pak1 mutant cells, indicating that both mutants produce MFα pheromone (Fig. 4C). With respect to the response of mutant cells to pheromone, neither ste20α nor α pak1 mutant strains formed filaments in response to wild-type MATa cells, indicating that these mutants fail to respond to MFa pheromone (Fig. 4C). a pak1 mutant cells also failed to respond to wild-type MATα cells, whereas ste20a mutant cells responded (Fig. 4C; compare the higher-magnification panels). These results demonstrate that Ste20α and Pak1 are required for haploid fruiting in response to pheromone, that the PAK kinases are not essential for pheromone production, and that Pak1 but not Ste20a is required for morphological responses to MFα pheromone.

PAK kinases function in a conserved MAP kinase cascade.

Epistasis experiments were conducted to establish the point of action of Ste20α with respect to the MAP kinase cascade known to control mating. Overexpression of the G protein β subunit Gpb1, which activates mating, did not restore mating of ste20α mutants, suggesting Ste20α may function downstream of Gpb1. On the other hand, overexpression of the MAP kinase Cpk1-1 allele or of a dominant-active Ste11α-1 MEK kinase mutant restored mating of ste20α mutants (Fig. 5A). These findings support a model in which Ste20α functions downstream of the Gβ subunit Gpb1 and upstream of the Ste11α and Cpk1 kinases in the MAP kinase pathway required for mating.

FIG. 5.

Ste20α kinase functions in a MAP kinase pathway for mating. (A) Plasmids expressing the GAL7-CPK1-1 fusion gene or the constitutively active STE11α-1 allele were transformed into the serotype A MATα ste20α ura5 mutant strain PPW96. Prototrophic GAL7-CPK1-1 and STE11α-1 transformants were mated with the serotype D ste20a mutant (CSB5) on V8 medium for 1 to 3 weeks at 24°C and photographed at ×40 final magnification. (B) ste20α::ura5 ura5 (CSB48) and α pak1::ura5 ura5 (CSB23) mutant strains with or without the STE12α gene expressed from the GAL7 promoter were inoculated on filament agar containing 0.5% galactose. The plates were incubated for 7 days in the dark at 24°C and photographed at ×40 final magnification. (C) Cdc42 interacts with Ste20α and Pak1 in the two-hybrid system. Two-hybrid protein-protein interaction assays were conducted with strain PJ69-4A containing plasmids expressing the Gal4 activation and DNA binding domains either alone or fused to Cdc42 or to regions of Ste20α or Pak1 encompassing the CRIB domains. The cells were grown on SD-Leu-Trp synthetic medium (Control) or SD-Leu-Trp-His plus 3-AT medium (Binding) to monitor protein-protein interaction-dependent expression of the Gal4-driven GAL-HIS3 reporter gene. The cells were grown for 72 h at 30°C. Similar results were obtained with the GAL-ADE2 reporter gene (not shown). β-Galactosidase expressed from the GAL-lacZ reporter was assayed in Miller units and yielded 667 units for Cdc42 and Pak1, 141 units for Cdc42 and Ste20α, and 40 to 55 units in control strains. +, present; −, absent.

We also examined the roles of these components during haploid fruiting. In this case, overexpression of the Cpk1-1 MAP kinase or the Ste11α-1 activated kinase did not restore haploid fruiting of MATα ste20α and pak1 mutant strains (not shown), whereas overexpression of the Ste12α transcription factor homolog did restore fruiting of both ste20α and MATα pak1 mutants (Fig. 5B).

We also found that both Ste20α and Pak1 physically interact with the small GTPase Cdc42. In other organisms, Ste20 is localized to areas of polarized growth by virtue of the ability to associate with Cdc42 via the CRIB regulatory domain (26). Interestingly, we found that the CDC42 and PAK1 genes are adjacent in C. neoformans. To determine if the Ste20α and Pak1 proteins interact with Cdc42, the Cdc42 protein was fused to the Gal4 DNA binding domain and portions of the Ste20α (amino acids 164 to 327) and Pak1 (amino acids 1 to 139) proteins encompassing the CRIB domains were fused to the Gal4 activation domain. Coexpression of the resulting GAL4BD-Cdc42 and GAL4AD-Ste20α or GAL4AD-Pak1 fusion proteins activated Gal4-dependent expression of the ADE2, HIS3, and lacZ reporter genes (Fig. 5C). Thus, Cdc42 physically interacts with both Pak1 and Ste20α, supporting a model in which the PAK kinases are activated by Cdc42.

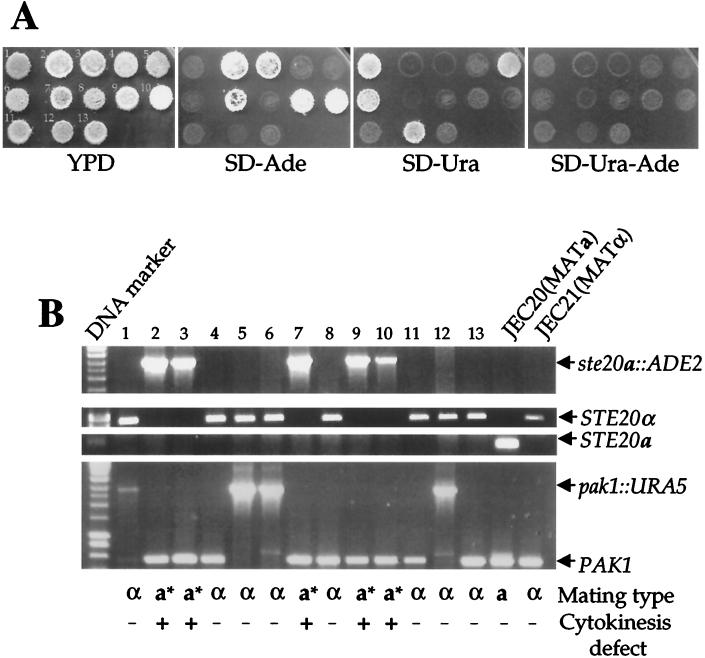

Ste20 and Pak1 have a shared role essential for viability.

In S. cerevisiae, cla4 and ste20 mutations are synthetically lethal, indicating that the two kinases share an overlapping essential function. We took two approaches to test if the Ste20 and Pak1 kinases have a similar shared essential function in C. neoformans. First, we attempted to delete the serotype A PAK1 gene in a ste20α::ADE2 ura5 strain using a pak1::URA5 disruption allele. No pak1 mutants were identified from ∼400 Ura+ colonies. Because gene disruptions typically occur at 2 to 16% in C. neoformans, we would have expected to isolate between 8 and 64 pak1 mutants if the ste20α pak1 double mutant were viable.

To further test this hypothesis, genetic crosses were performed with the C. neoformans serotype D ste20 and pak1 mutants. The ste20a::ADE2 ura5 mutant strain KBL156-1 and the MATα pak1::URA5 ade2 mutant strain CSB8 were crossed, and basidiospores were micromanipulated and germinated on YPD medium at 24°C. The resulting meiotic segregants were then replica plated onto selective medium to follow segregation of the ste20a and pak1 mutations (Fig. 6A). In addition, DNA was isolated and analyzed by PCR with primers specific to the STE20α, STE20a, and PAK1 genes (Fig. 6B). From several ste20a × α pak1 crosses, a total of 60 viable basidiospores were obtained and yielded similar results. One such mating that gave rise to 13 viable meiotic segregants out of 18 spores is depicted in Fig. 6A. Of the 13 segregants, five were MATa ste20a::ADE2, four were MATα pak1::URA5, and four were wild type MATα (Fig. 6A). No ste20a pak1 colonies were recovered, indicating that these mutations are synthetically lethal. A similar analysis was performed with the ste20α and a pak1 mutant strains. No ste20α pak1 progeny were obtained, indicating that the ste20α pak1 mutant combination is also synthetically lethal. We note that the inability to recover these double mutants is not attributable to linkage, because the genes are located on different chromosomes (Fig. 2A). In conclusion, both Ste20α and Ste20a share an essential function with Pak1.

FIG. 6.

ste20 and pak1 mutations exhibit synthetic lethality. (A) pak1 mutant CSB8 (MATα pak1::URA5 ade2) was crossed to the ste20a mutant KBL156-1 (MATa ste20a::ADE2 ura5) on V8 medium for 7 days. Basidiospores were dissected and germinated on YPD medium. Meiotic segregants were replica plated onto YPD medium and synthetic medium lacking adenine (SD-Ade), uracil (SD-Ura), or uracil and adenine (SD-Ura-Ade) to score the ste20a::ADE2 and the pak1::URA5 mutations and markers. (B) Genomic DNA from the meiotic segregants and wild-type strains JEC20 and JEC21 was analyzed by PCR with primers specific to the STE20α, STE20a, and PAK1 genes. Mating-type tests were conducted, and segregants were scored as MATα, MATa, or MATa* (the asterisk indicates a bilateral mating defect with ste20α mutant cells [Fig. 4]). Meiotic segregants were grown on YPD medium at 37°C, and those exhibiting a cytokinesis defect were designated +.

STE20α plays a serotype-specific role in virulence.

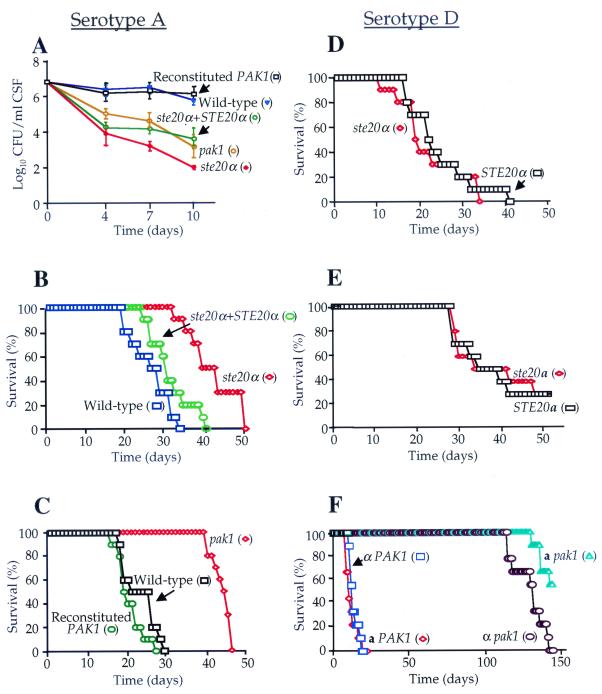

The virulence of C. neoformans has been linked to growth at 37 and 39°C and mating type. We tested the role of the C. neoformans PAK kinases in virulence in two animal models of cryptococcosis (3, 39, 41). First, the serotype A wild-type strain H99, the ste20α mutant, and the ste20α STE20α reconstituted strains were inoculated intrathecally into steroid-immunosuppressed rabbits. The survival of cryptococcal cells in the central nervous system was determined by serially diluting and plating CSF onto YPD agar medium. While wild-type cells persisted in the central nervous system at similar levels over the 10-day course of infection (106 cells/ml), the persistence of the ste20α mutant was significantly reduced (102 cells/ml) (Fig. 7A). In comparison, the reconstituted ste20α STE20α strain was partially restored for virulence (104 cells/ml) (Fig. 7A).

FIG. 7.

Virulence of C. neoformans ste20α, ste20a, and pak1 mutant strains. (A) Isogenic serotype A wild-type (H99), ste20α mutant (PPW91), ste20α STE20α reconstituted (PPW151), pak1 mutant (CSB1), and PAK1 reconstituted (CSB3) strains were inoculated intracisternally into immunosuppressed rabbits. CSF was withdrawn on days 4, 7, and 10 postinfection, and the number of surviving yeast cells was determined by plating serially diluted CSF on YPD medium. The mean value of cell counts for each strain was plotted (the error bars indicate the standard error of the mean). (B and C) Serotype A strains used for panel A were also inoculated into A/Jcr mice (10 mice per strain) by inhalation, and survival was monitored daily and plotted. (D, E, and F) Similarly, wild-type (JEC21 and JEC20) and ste20α (CSB7), ste20a (CSB5), α pak1 (CSB9), and a pak1 (CSB10) mutant serotype D strains were inoculated by tail vein injection into DBA mice (10 mice per strain), and survival was plotted against time.

Similar results were obtained in the murine inhalation model. The average survival of A/Jcr mice infected with the wild-type serotype A strain H99 was 28 days, and 100% lethality occurred by day 34 (Fig. 7B). Virulence was attenuated in the ste20α mutant (P < 0.001 versus the wild type); 80% of infected mice survived to day 37, the average survival was 42 days, and 100% lethality occurred by day 51. Virulence was largely restored to wild type in the ste20α STE20α reconstituted strain in the murine model (P = 0.082 versus the wild type), and the average survival was 31 days, with 100% lethality occurring by day 40 (Fig. 7B).

We also examined the virulence of serotype D ste20α and ste20a mutants in a murine tail vein injection model of cryptococcosis in DBA mice lacking the C5 component of the complement system. In contrast to the serotype A ste20α mutant strains in the A/Jcr murine inhalation model, three independent serotype D ste20α mutants and the ste20a mutant strain were fully virulent in the DBA murine tail vein injection model. Mice infected with the wild-type MATα JEC21 strain survived an average of 22 days, whereas those infected with the ste20α mutant survived on average 19 days, with 80% lethality occurring by day 31 with both the wild type and the ste20α mutant (Fig. 7D) (P = 0.59). Similarly, the survival curves for mice infected with the MATa wild-type strain JEC20 and the congenic ste20a mutant were essentially superimposable (Fig. 7E) (P = 0.44). Thus, neither Ste20 kinase is required for virulence in the congenic serotype D laboratory strains, whereas the Ste20α kinase contributes to virulence in the serotype A strain H99.

Pak1 kinase is required for virulence.

We next examined the role of the Pak1 kinase in virulence. In the rabbit model of cryptococcal meningitis, survival of the serotype A pak1 mutant in CSF was significantly reduced by day 10 following infection (103 cells/ml), while the PAK1 reconstituted strain was fully virulent (106 cells/ml) (Fig. 7A). Similarly, in the murine model, the pak1 mutant strains were significantly attenuated (Fig. 7C and F) (P < 0.001). With the serotype A pak1 mutant strain, 100% lethality was delayed until day 46 compared to day 30 for the wild-type strain (Fig. 7C). All mice infected with serotype D pak1 mutant strains were still alive 114 days postinfection, indicating that these strains are nearly avirulent (Fig. 7F) (P < 0.001). Fifty percent lethality of mice infected with the MATα pak1 and the MATa pak1 mutant strains occurred by days 132 and 144 postinfection, respectively. These virulence defects were attributable to the pak1 mutation; virulence was restored to the wild-type level in the serotype A PAK1 reconstituted strain (Fig. 7C) (P = 0.32 compared to the wild type), and independent pak1 mutants in both mating types in the serotype D strains were dramatically attenuated (Fig. 7F). In summary, the Pak1 kinase is required for virulence in both serotypes of C. neoformans.

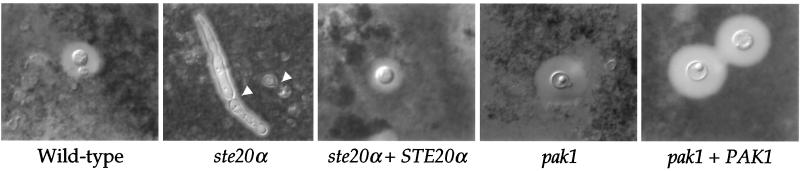

The ste20α mutation impairs capsule production in vivo.

A large polysaccharide capsule and the pigment melanin are two well-established virulence factors of C. neoformans. We examined whether the effects of the ste20α or pak1 mutation on virulence in serotype A are attributable to defects in capsule or melanin production. Capsule size was found to be reduced in animals infected with the serotype A ste20α mutant, but not in those infected with the pak1 mutant. This capsule defect was apparent in both CSF yeast cells stained with India ink from infected rabbits (day 3 postinfection) (not shown) and India ink-stained brain smears from mice (day 10 postinfection) (Fig. 8). The capsule defect was not complemented in all cells of the ste20α STE20α reconstituted strain (Fig. 8), which may explain why virulence was not fully restored (Fig. 7A and B).

FIG. 8.

STE20α gene promotes capsule formation in vivo. The brains of mice infected with the wild-type (H99), ste20α (PPW91), and pak1 (CSB1) mutants and the ste20α STE20α (PPW151) and PAK1 (CSB3) reconstituted serotype A strains were recovered at 10 days postinfection and homogenized, and the fungal cells were stained with India ink. Capsules were observed by DIC microscopy and photographed at ×1,000 final magnification. The arrowheads indicate ste20α mutant cells exhibiting a cytokinesis defect.

Interestingly, a significant proportion of the serotype A ste20α mutant cells isolated from infected animals exhibited a non-yeast cell morphology in that the cells were elongated and encapsulated. These “filaments” lacked clamp connections associated with mating and haploid fruiting. In addition, the filamented cells contained complete septa but failed to separate. These results suggest that the ste20α mutant cells have adopted a pseudohypha-like growth mode in vivo (Fig. 8). Normal budding yeast cell morphology was restored in the ste20α STE20α reconstituted strain (Fig. 8). In summary, ste20α mutant strains exhibited defects in two known cryptococcal virulence factors, capsule and high-temperature growth, and exhibited an interesting filamentous morphology in vivo. By comparison, the ste20 and pak1 mutant strains exhibited no melanin defect, and the pak1 mutant strains had no capsule defect and grew normally at elevated temperature, failing to provide a clear link between these factors and the attenuated phenotype of pak1 mutants.

DISCUSSION

In summary, we have functionally characterized the STE20α, STE20a, and PAK1 genes, which encode homologs of the Ste20/PAK kinase family in C. neoformans. Importantly, the STE20α and STE20a genes are mating type specific and reside in the MATα and MATa mating-type loci, whereas the PAK1 gene is not mating type specific and is present on a different chromosome. Genetic studies of kinase mutant strains reveal that these kinases play overlapping roles in mating, fruiting, and virulence. The Ste20 kinases also play a unique role in cytokinesis and, in serotype A, growth at elevated temperature. Finally, the observation that ste20 and pak1 mutations are synthetically lethal further indicates that these kinases share an essential function required for viability. These studies illustrate how mating-type-specific and nonspecific components of a conserved MAP kinase pathway contribute to cell-type-specific signaling.

Ste20 kinases have similarities to both Ste20 and Cla4 of S. cerevisiae.

In the yeast S. cerevisiae, the Ste20 and Cla4 kinases have partially overlapping functions in the regulation of morphogenesis and mating (10). The Ste20 and Cla4 kinases both interact with and are activated by the Cdc42 GTPase (26, 43), but the Ste20 kinase is uniquely adapted to associate with the Gβγ subunit complex during responses to pheromone and mating (28). Interactions between Cdc42 and Ste20 are necessary for pseudohyphal differentiation (26), and the small GTPase Ras2 promotes filamentous growth, in part by signaling upstream of Cdc42 and Ste20 (38). Similarly, the Ras1 homologs function in pheromone signaling in S. pombe and C. neoformans (1, 35).

The C. neoformans Ste20α, Ste20a, and Pak1 kinases have levels of amino acid sequence identity and structural and functional properties similar to those of both yeast kinases. C. neoformans ste20α, ste20a, and pak1 mutants are mating impaired, a phenotype exhibited by ste20 mutants in many but not all S. cerevisiae strains (10, 24). The STE20α and STE20a genes are contained within the MATα and MATa loci that determine mating type (30). On the other hand, the Ste20α and Ste20a kinases contain a PH domain that is a unique feature of the Cla4 kinases of both S. cerevisiae and C. albicans, and the C. neoformans ste20α and ste20a mutants both exhibit cytokinesis defects similar to those of S. cerevisiae cla4 mutants. We have designated the Ste20α and Ste20a kinases Ste20 homologs based on the links to MAP kinase signaling and the MAT loci, but given a role in cytokinesis and the presence of a PH domain, they also share features with Cla4-related kinases.

Ste20α and Pak1 kinases function in MAP kinase signaling.

Epistasis tests indicate that the Ste20α and Pak1 kinases function in the MAP kinase pathway regulating mating. Overexpression of the G protein β subunit Gpb1 failed to suppress the mating defect of ste20α mutant strains. These findings are consistent with a model in which Ste20α functions downstream of Gpb1. Overexpression of the MAP kinase Cpk1 or the dominant-active Ste11α-1 mutant restored mating of ste20α and pak1 mutant strains, indicating that Ste11α and Cpk1 may function downstream of the PAK kinases.

Overexpression of the MAP kinase Cpk1 or an activated form of the Ste11α kinase failed to restore haploid fruiting of the pak1 and ste20α mutant strains. In contrast, overexpression of the Ste12α transcription factor homolog did restore fruiting of α pak1 and ste20α mutants. Our interpretation is that partial activation of the MAP kinase cascade is insufficient to bypass the upstream components for fruiting, whereas overexpression of Ste12α can bypass the requirement for Ste20α or Pak1, either because the action of Ste12 is more robust or because it functions in more than one pathway. Our findings support models in which the Ste20α and Pak1 kinases have partially redundant roles in activating the MAP kinase pathway. We also found that the Cdc42 GTPase physically interacts with the CRIB domain of the Ste20α kinase. These findings provide evidence that a Cdc42-Ste20α/Pak1-Ste11α-Cpk1 pathway functions in mating and fruiting. Further genetic and biochemical studies will be required to define the point of action of the Ste20 and Pak1 kinases in the MAP kinase and other signaling and morphogenesis pathways and to establish the mechanisms by which these related kinases are activated to phosphorylate their substrates.

The Ste20α kinase plays divergent roles in the virulence of serotype A and D strains.

The findings that MATα strains (i) are significantly more prevalent in both environmental and clinical isolates, (ii) are more virulent than MATa strains, and (iii) undergo haploid fruiting have focused interest on the genes encoded by the MATα locus and their association with pathobiology in cryptococcosis. Our studies have identified the STE20α gene as a novel component of the MATα locus that is associated with virulence in serotype A strains, and STE20α represents the first gene in the MATα locus to be linked to virulence in serotype A strains. The Ste20α kinase controls production of the polysaccharide capsule, a known virulence factor, and also contributes to virulence by regulating growth at mammalian body temperatures.

Most interestingly, the ste20α mutant exhibited a pseudohypha-like morphology in vivo (Fig. 8), suggesting that a role in normal budding yeast growth may be important for virulence. Our observations may also be related to a recent report of an unusual C. neoformans isolate that produced hypha-like extensions and was obtained from a feline nasal granuloma (6). This unusual serotype A MATα isolate also exhibited a temperature-sensitive growth defect and produced elongated cells at 37°C in vitro (6), strikingly similar to our findings with the ste20α mutant serotype A isolate reported here. These findings suggest that this clinical isolate may harbor a mutation in the Ste20α kinase or another element of the signaling cascade.

In contrast to the functions of the Ste20α kinase in the virulence of serotype A strains, serotype D strains lacking Ste20α were fully virulent. Strains lacking the second PAK kinase homolog, Pak1, were attenuated for virulence in both serotypes. Although the STE20 and PAK1 genes share some functions in both serotypes, the Pak1 kinase may have evolved to supplant the role of the Ste20α kinase in virulence during the divergence of serotype A and D strains from a common progenitor. Alternatively, this difference in the role of the Ste20α kinase in virulence in serotype A compared to serotype D strains may be attributable to divergent roles of other signaling cascades. In previous studies, the Ste12α transcription factor encoded by the MATα locus was found to be required for virulence in the serotype D strain JEC21 but not for virulence in the serotype A strain H99 (8, 57). The protein kinase A pathway plays a central role in the virulence of serotype A strains of C. neoformans (3, 4, 13) but is largely dispensable for pathogenesis of congenic serotype D strains (C. A. D'Souza and J. Heitman, unpublished data). Taken together, these observations suggest that the relative contributions of different signaling cascades to virulence may change as pathogens evolve into closely related but distinct varieties or species.

PAK kinases play conserved roles in morphogenesis and virulence.

From studies of model yeasts, it is clear that PAK kinases are required for morphogenic events, such as bud emergence and apical growth. Cla4 has an additional role in the switch from apical to isotropic growth in S. cerevisiae (reviewed in reference 44), and the Ste20 homolog Shk1/Pak1 is essential for polar growth in S. pombe (35, 40). However, recent studies have shown that PAK kinases also play an important role in morphogenesis in other fungi. In Y. lipolytica and C. albicans, PAK kinase homologs are required for the dimorphic transition from budding yeast to filamentous growth (18, 25, 27, 48). In C. albicans, this switch is also associated with virulence, and both Cst20 (a Ste20 homolog) and CaCla4 (a Cla4 homolog) are required for virulence in mouse models. However, while cst20/cst20 mutants are only partially attenuated for virulence and can still switch from yeast to hyphae in vivo, cla4/cla4 mutants are completely avirulent and are unable to switch in vivo. In addition, cla4/cla4 mutants exhibit morphological defects. These results parallel our findings that deletion of the STE20 and PAK1 genes confers different phenotypes with respect to the virulence and morphology of C. neoformans.

Recently, a Cla4 homolog in the cotton pathogen A. gossypii was found to be required for hyphal maturation and septation (5). In A. gossypii, early filaments switch from a slow- to a fast-growing form in a poorly understood process called hyphal maturation (5). cla4 mutant strains are unable to switch to the fast-growing form, and as a consequence, the filaments produced are short and undergo premature apical branching. Interestingly, this phenotype is strikingly similar to our observations of the stubby mating filaments produced by an ste20α × ste20a bilateral mutant cross in C. neoformans. It is possible that Ste20 is required for a similar process in C. neoformans and that dikaryotic filaments lacking both ste20α and ste20a are unable to properly signal to the growing hyphal tip to accelerate growth.

Organization of the mating-type locus and links to virulence.

Our studies reveal that the MAT locus in C. neoformans is organized in a specialized and unique fashion in which components of the MAP kinase signaling cascade itself, the Ste20α and Ste20a kinases, are encoded by the MATα and MATa alleles. These studies and others of the structure of the mating-type loci in C. neoformans may provide insight into the evolution of virulence and asexual and sexual reproduction. We propose that the components of the MAP kinase cascade encoded by the MATα locus are evolving to play specialized roles in haploid fruiting and virulence, properties known to be associated with the MATα locus. Because other components of the MAP kinase cascade are encoded by genes present in both MATα and MATa cells, the specialization of MATα-encoded components to regulate fruiting and virulence may have resulted in an incompatibility with non-mating-type-specific signaling components such that mating of MATα strains became impaired. As a consequence, MATα strains would become sexually isolated and restricted to asexual reproduction, which may favor virulence by preventing outcrossing events. Our studies provide tools to address this and other models at the molecular level.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lora Cavallo and Cristl Arndt for technical assistance.

This work was supported by NIAID R01 grants AI39115 and AI42159 to J. Heitman, NIAID P01 grant AI44975 to the Duke University Mycology Research Unit, and NCI K01 award CA77075 to Maria E. Cardenas. Gary Cox is a Burroughs Wellcome New Investigator in Molecular Pathogenic Mycology. Joseph Heitman is an associate investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and a Burroughs Wellcome Scholar in Molecular Pathogenic Mycology.

P.W. and C.B.N. made equal contributions to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alspaugh, J. A., L. M. Cavallo, J. R. Perfect, and J. Heitman. 2000. RAS1 regulates filamentation, mating and growth at high temperature of Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Microbiol. 36:352-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alspaugh, J. A., R. C. Davidson, and J. Heitman. 2000. Morphogenesis of Cryptococcus neoformans. Contrib. Microbiol. 5:217-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alspaugh, J. A., J. R. Perfect, and J. Heitman. 1997. Cryptococcus neoformans mating and virulence are regulated by the G-protein α subunit GPA1 and cAMP. Genes Dev. 11:3206-3217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alspaugh, J. A., R. Pukkila-Worley, T. Harashima, L. M. Cavallo, D. Funnell, G. M. Cox, J. R. Perfect, J. W. Kronstad, and J. Heitman. 2002. Adenylyl cyclase functions downstream of the Gα protein GPA1 and controls mating and pathogenicity of Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot. Cell 1:75-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ayad-Durieux, Y., P. Knechtle, S. Goff, F. Dietrich, and P. Philippsen. 2000. A PAK-like protein kinase is required for maturation of young hyphae and septation in the filamentous ascomycete Ashbya gossypii. J. Cell Sci. 113:4563-4575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bemis, D. A., D. J. Krahwinkel, L. A. Bowman, P. Mondon, and K. J. Kwon-Chung. 2000. Temperature-sensitive strain of Cryptococcus neoformans producing hyphal elements in a feline nasal granuloma. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:926-928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casadevall, A., and J. R. Perfect. 1998. Cryptococcus neoformans. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 8.Chang, Y. C., B. L. Wickes, G. F. Miller, L. A. Penoyer, and K. J. Kwon-Chung. 2000. Cryptococcus neoformans STE12α regulates virulence but is not essential for mating. J. Exp. Med. 191:871-882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clarke, D. L., G. L. Woodlee, C. M. McClelland, T. S. Seymour, and B. L. Wickes. 2001. The Cryptococcus neoformans STE11α gene is similar to other fungal mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase (MAPKKK) genes but is mating type specific. Mol. Microbiol. 40:200-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cvrckova, F., C. D. Virgilio, E. Manser, J. R. Pringle, and K. Nasmyth. 1995. Ste20-like protein kinases are required for normal localization of cell growth and for cytokinesis in budding yeast. Genes Dev. 9:1817-1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davidson, R. C., T. D. E. Moore, A. R. Odom, and J. Heitman. 2000. Characterization of the MFα pheromone of the human fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dohlman, H. G., and J. W. Thorner. 2001. Regulation of G protein-initiated signal transduction in yeast: paradigms and principles. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70:703-754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D'Souza, C. A., J. A. Alspaugh, C. Yue, T. Harashima, G. M. Cox, J. R. Perfect, and J. Heitman. 2001. Cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase controls virulence of the fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:3179-3191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faure, S., S. Vigneron, M. Doree, and N. Morin. 1997. A member of the Ste20/PAK family of protein kinases is involved in both arrest of Xenopus oocytes at G2/prophase of the first meiotic cell cycle and in prevention of apoptosis. EMBO J. 16:5550-5561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Granger, D. L., J. R. Perfect, and D. T. Durack. 1985. Virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans: regulation of capsule synthesis by carbon dioxide. J. Clin. Investig. 76:508-516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffman, C. S., and F. Winston. 1987. A ten-minute DNA preparation from yeast efficiently releases autonomous plasmids for transformation of Escherichia coli. Gene 57:267-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson, D. I. 1999. Cdc42: an essential Rho-type GTPase controlling eukaryotic cell polarity. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63:54-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Köhler, J. R., and G. R. Fink. 1996. Candida albicans strains heterozygous and homozygous for mutations in mitogen-activated protein kinase signalling components have defects in hyphal development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:13223-13228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kopecka, M., M. Gabriel, K. Takeo, M. Yamaguchi, A. Svoboda, M. Ohkusu, K. Hata, and S. Yoshida. 2001. Microtubules and actin cytoskeleton in Cryptococcus neoformans compared with ascomycetous budding and fission yeasts. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 80:303-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwon-Chung, K. J. 1976. Morphogenesis of Filobasidiella neoformans, the sexual state of Cryptococcus neoformans. Mycologia 68:821-833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kwon-Chung, K. J. 1975. A new genus. Filobasidiella, the perfect state of Cryptococcus neoformans. Mycologia 67:1197-1200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwon-Chung, K. J., and J. E. Bennett. 1978. Distribution of α and a mating types of Cryptococcus neoformans among natural and clinical isolates. Am. J. Epidemiol. 108:337-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwon-Chung, K. J., J. C. Edman, and B. L. Wickes. 1992. Genetic association of mating types and virulence in Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect. Immun. 60:602-605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leberer, E., D. Dignard, D. Harcus, D. Y. Thomas, and M. Whiteway. 1992. The protein kinase homologue Ste20p is required to link the yeast pheromone response G-protein βγ subunits to downstream signalling components. EMBO J. 11:4815-4824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leberer, E., D. Harcus, I. D. Broadbent, K. L. Clark, D. Dignard, K. Ziegelbauer, A. Schmidt, N. A. R. Gow, A. J. P. Brown, and D. Y. Thomas. 1996. Signal transduction through homologs of the Ste20p and Ste7p protein kinases can trigger hyphal formation in the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:13217-13222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leberer, E., C. Wu, T. Leeuw, A. Fourest-Lieuvin, J. E. Segall, and D. Y. Thomas. 1997. Functional characterization of the Cdc42p binding domain of yeast Ste20p protein kinase. EMBO J. 16:83-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leberer, E., K. Ziegelbauer, A. Schmidt, D. Harcus, D. Dignard, J. Ash, L. Johnson, and D. Y. Thomas. 1997. Virulence and hyphal formation of Candida albicans require the Ste20p-like protein kinase CaCla4p. Curr. Biol. 7:539-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leeuw, T., C. Wu, J. D. Schrag, M. Whiteway, D. Y. Thomas, and E. Leberer. 1998. Interaction of G-protein β-subunit with a conserved sequence in Ste20/PAK family protein kinases. Nature 391:191-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lemmon, M. A., and K. M. Ferguson. 2000. Signal-dependent membrane targeting by pleckstrin homology (PH) domains. Biochem. J. 350:1-18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lengeler, K. B., P. Wang, G. M. Cox, J. R. Perfect, and J. Heitman. 2000. Identification of the MATa mating type locus of Cryptococcus neoformans reveals a serotype A MATa strain thought to have been extinct. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:14455-14460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu, H., J. Köhler, and G. R. Fink. 1994. Suppression of hyphal formation in Candida albicans by mutation of a STE12 homolog. Science 266:1723-1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu, H., C. A. Styles, and G. R. Fink. 1993. Elements of the yeast pheromone response pathway required for filamentous growth of diploids. Science 262:1741-1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lo, H.-J., J. R. Köhler, B. DiDomenico, D. Loebenberg, A. Cacciapuoti, and G. R. Fink. 1997. Nonfilamentous C. albicans mutants are avirulent. Cell 90:939-949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manser, E., T. Leung, H. Salihuddin, Z. S. Zhao, and L. Lim. 1994. A brain serine/threonine protein kinase activated by Cdc42 and Rac1. Nature 367:40-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marcus, S., A. Polverino, E. Chang, D. Robbins, M. H. Cobb, and M. H. Wigler. 1995. Shk1, a homolog of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ste20 and mammalian p65PAK protein kinases, is a component of a Ras/Cdc42 signaling module in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:6180-6184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McDade, H. C., and G. M. Cox. 2001. A new dominant selectable marker for use in Cryptococcus neoformans. Med. Mycol. 39:151-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moore, T. D. E., and J. C. Edman. 1993. The α-mating type locus of Cryptococcus neoformans contains a peptide pheromone gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:1962-1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mösch, H. U., R. L. Roberts, and G. R. Fink. 1996. Ras2 signals via the Cdc42/Ste20/mitogen-activated protein kinase module to induce filamentous growth in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:5352-5356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Odom, A., S. Muir, E. Lim, D. L. Toffaletti, J. Perfect, and J. Heitman. 1997. Calcineurin is required for virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. EMBO J. 16:2576-2589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ottilie, S., P. J. Miller, D. I. Johnson, C. L. Creasy, M. A. Sells, S. Bagrodia, S. L. Forsburg, and J. Chernoff. 1995. Fission yeast pak1+ encodes a protein kinase that interacts with Cdc42p and is involved in the control of cell polarity and mating. EMBO J. 14:5908-5919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perfect, J. R., S. D. R. Lang, and D. T. Durack. 1980. Chronic cryptococcal meningitis: a new experimental model in rabbits. Am. J. Pathol. 101:177-194. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perfect, J. R., D. L. Toffaletti, and T. H. Rude. 1993. The gene encoding phosphoribosylaminoimidazole carboxylase (ADE2) is essential for growth of Cryptococcus neoformans in cerebrospinal fluid. Infect. Immun. 61:4446-4451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peter, M., A. M. Neiman, H. O. Park, M. van Lohuizen, and I. Herskowitz. 1996. Functional analysis of the interaction between the small GTP binding protein Cdc42 and the Ste20 protein kinase in yeast. EMBO J. 15:7046-7059. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pruyne, D., and A. Bretscher. 2000. Polarization of cell growth in yeast. J. Cell Sci. 113:571-585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 46.Sudarshan, S., R. C. Davidson, J. Heitman, and J. A. Alspaugh. 1999. Molecular analysis of the Cryptococcus neoformans ADE2 gene, a selectable marker for transformation and gene disruption. Fungal Genet. Biol. 27:36-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sukroongreung, S., K. Kitiniyom, C. Nilakul, and S. Tantimavanich. 1998. Pathogenicity of basidiospores of Filobasidiella neoformans var. neoformans. Med. Mycol. 36:419-424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Szabo, R. 2001. Cla4 protein kinase is essential for filament formation and invasive growth of Yarrowia lipolytica. Mol. Genet. Genomics 265:172-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Toffaletti, D. L., and J. R. Perfect. 1994. Biolistic DNA delivery for Cryptococcus neoformans transformation, p. 303-308. In B. Maresca and G. S. Kobayashi (ed.), Molecular biology of pathogenic fungi: a laboratory manual. Telos Press, New York, N.Y.

- 50.Vartivarian, S. E., E. J. Anaissie, R. E. Cowart, H. A. Sprigg, M. J. Tingler, and E. S. Jacobson. 1993. Regulation of cryptococcal capsular polysaccharide by iron. J. Infect. Dis. 167:186-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang, P., M. E. Cardenas, G. M. Cox, J. Perfect, and J. Heitman. 2001. Two cyclophilin A homologs with shared and distinct functions important for growth and virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. EMBO Rep. 2:511-518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang, P., and J. Heitman. 1999. Signal transduction cascades regulating mating, filamentation, and virulence in Cryptococcus neoformans. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2:358-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang, P., J. R. Perfect, and J. Heitman. 2000. The G-protein β subunit GPB1 is required for mating and haploid fruiting in Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:352-362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wickes, B. L., U. Edman, and J. C. Edman. 1997. The Cryptococcus neoformans STE12α gene: a putative Saccharomyces cerevisiae STE12 homologue that is mating type specific. Mol. Microbiol. 26:951-960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wickes, B. L., M. E. Mayorga, U. Edman, and J. C. Edman. 1996. Dimorphism and haploid fruiting in Cryptococcus neoformans: association with the α-mating type. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:7327-7331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xu, J., R. J. Vilgalys, and T. G. Mitchell. 2000. Multiple gene genealogies reveal dispersion and hybridization in the human pathogenic fungus Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Ecol. 9:1471-1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yue, C., L. M. Cavallo, J. A. Alspaugh, P. Wang, G. M. Cox, J. R. Perfect, and J. Heitman. 1999. The STE12α homolog is required for haploid filamentation but largely dispensable for mating and virulence in Cryptococcus neoformans. Genetics 153:1601-1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]