Abstract

Ammonium and the analogue methylammonium are taken into the cell by active transport systems which constitute a family of transmembrane proteins that have been identified in fungi, bacteria, plants, and animals. Two genes from Aspergillus nidulans, mepA and meaA, which encode ammonium transporters with different affinities have been characterized. The MepA transporter exhibits the highest affinity for methylammonium (Km0, 44.3 μM); in comparison, the Km for MeaA is 3.04 mM. By use of targeted gene replacement strategies, meaA and mepA deletion mutants were created. Deletion of both meaA and mepA resulted in the inability of the strain to grow on ammonium concentrations of less than 10 mM. The single meaA deletion mutant exhibited reduced growth at the same concentrations, whereas the mepA deletion mutant displayed wild-type growth. Interestingly, multiple copies of mepA were found to complement the methylammonium resistance phenotype conferred by the deletion of meaA. The expression profiles for mepA and meaA differed; the mepA transcript was detected only in nitrogen-starved cultures, whereas meaA was expressed under both ammonium-sufficient and nitrogen starvation conditions. Together, these results indicate that MeaA constitutes the major ammonium transport activity and is required for the optimal growth of A. nidulans on ammonium as the sole nitrogen source and that MepA probably functions in scavenging low concentrations of ammonium under nitrogen starvation conditions.

Members of the ammonium transporter (AMT)/methylammonium permease (MEP) superfamily have been identified in fungi, bacteria, plants, and animals, although many of these sequences have not been functionally characterized. Recently, sequences of members of the Rhesus protein family were also shown to have similarity to AMT/MEP sequences (23). While Escherichia coli contains a single AMT/MEP gene, amtB (40), multiple ammonium permeases with different kinetic properties within an organism are common. For example, the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 has three AMT/MEP genes, encoding one high-affinity and two low-affinity transporters which are regulated by the nitrogen control transcription factor NtcA (29). Arabidopsis thaliana contains six AMT genes (16, 30, 44), including the divergent AtAMT2;1 (38). The AtAMT1;1, AtAMT1;2, and AtAMT1;3 genes exhibit both nitrogen and diurnal regulation (14). The presence of at least two ammonium transport systems with different affinities has been reported for Neurospora crassa (37), and genomic sequencing has identified four putative genes in this fungus (assembly version 1, Neurospora Sequencing Project, Whitehead Institute/MIT Center for Genome Research, http://www-genome.wi.mit.edu). Genome database screening has also identified four putative AMT/MEP genes in Caenorhabditis elegans and three in Schizosaccharomyces pombe (10). Generally, AMT/MEP transporters appear to be ammonium uniporters which are fueled by membrane electrical potential and which can take up the substrate against a concentration gradient, and maximum transport activity is observed when cells are limited for ammonium (18, 37, 44).

Detailed studies have characterized three AMT/MEP permeases: Mep1p, Mep2p, and Mep3p from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (12, 24, 26, 34). These proteins are predicted to contain 11 transmembrane domains (22, 41), and each permease exhibits distinct kinetic properties (24). The Mep1p transporter constitutes the majority of ammonium uptake (Km, 5 to 10 μM), and MEP1 mutants are resistant to the toxic ammonium analogue methylammonium. The N-glycosylated Mep2p permease has the highest affinity for ammonium (Km, 1 to 2 μM) and is highly expressed in ammonium-limiting conditions (22, 24). Mep2p has also been proposed to act as an ammonium sensor generating a signal to regulate pseudohyphal growth in response to ammonium starvation (21). Mep3p is a low-affinity, high-capacity ammonium permease (Km, 1.4 to 2.1 mM). Deletion of all three MEP genes renders the cell unable to grow on media containing less than 5 mM ammonium as a sole nitrogen source, whereas no phenotypic effects have been noted for single-deletion strains (24). Expression of the MEP genes requires the GATA transcription factors Gln3p and Nil1p (24).

While no ammonium transporters have yet been characterized at the molecular level for Aspergillus nidulans, previous studies established the presence of a specific ammonium transport system (4, 9, 15, 32, 33). A. nidulans meaA mutants which displayed resistance to toxic levels of methylammonium were isolated and found to be defective in ammonium transport (2, 4). Using a wild-type strain, Cook and Anthony (9) characterized a single high-affinity (methyl)ammonium transport system operating over a low concentration range of 2 to 100 μM methylammonium in conidia germinated on glutamate (Km of methylammonium, 13 μM; Vmax, 4 μmol/min/g of dry weight). Significantly, this high-affinity system was present in an meaA mutant (9). These results indicate the presence of at least two independent ammonium transport proteins in A. nidulans: MeaA, which constitutes the majority of ammonium uptake, as indicated by mutants conferring methylammonium resistance, and a high-affinity permease which may function in scavenging low concentrations of ammonium during nitrogen starvation or growth on other nitrogen sources.

Using complementation and degenerate PCR strategies, we have isolated two genes, meaA and mepA, which are proposed to encode the two ammonium transport activities previously suggested for A. nidulans (4, 9). MeaA and MepA are predicted to contain 11 transmembrane domains and display high sequence similarity to known ammonium transporters. Kinetic analysis showed that MepA is a higher-affinity permease than MeaA. The meaA and mepA genes were inactivated in A. nidulans. The mepA meaA double-deletion mutant was shown to be unable to grow on ammonium concentrations of less than 10 mM; however, the mepA and meaA single-deletion mutants exhibited wild-type and reduced growth under these conditions, respectively. The expression of mepA and meaA differed; the mepA transcript was detected only in nitrogen-starved cultures, whereas meaA was also expressed under ammonium-sufficient conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A. nidulans strains, media, and transformation.

The A. nidulans strains used in this study are shown in Table 1. A. nidulans media (ANM) and growth conditions were as described previously (11). Unless stated otherwise, nitrogen sources were used at a final concentration of 10 mM and the carbon source was 1% (wt/vol) glucose. Genetic analysis was carried out by using techniques described previously (8). Strains of A. nidulans were transformed by the method of Andrianopoulos and Hynes (1). Cotransformants were selected by using the selectable marker plasmid pI4 (PyroA+) on media lacking pyridoxine (28, 31).

TABLE 1.

A. nidulans strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype |

|---|---|

| MH1 | biA1 |

| MH9233 | biA1 wA3 argB::trpCΔB pyroA4 riboB2 |

| MH9288 | yA2 meaA8 pyroA4 |

| MH9828 | biA1 wA3 argB::trpCΔB meaA::argB pyroA4 mepA::riboB riboB2 |

| MH9829 | biA1 meaA::argB pyroA4 mepA::riboB riboB2 |

| MH9861 | biA1 pyroA4 mepA::riboB riboB2 |

| MH9961 | biA1 wA3 argB::trpCΔB meaA::argB pyroA4 riboB2 |

| MH9965 | biA1 meaA::argB pyroA4 riboB2 |

Molecular techniques.

Standard methods for the manipulation of E. coli cells and DNA were those described by Sambrook et al. (36). The E. coli strain used in this study was NM522. Restriction enzymes (Promega) were used according to manufacturer recommendations. Blunt-ended restriction fragments were created by end filling with the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I (Promega). DNA fragments were recovered from agarose gels by using a BresaClean DNA purification kit (Geneworks). DNA fragments were subcloned into plasmid vector pBluescript SK(+) (Stratagene) or pGEM-T (Promega). A. nidulans genomic DNA was isolated by the method of Lee and Taylor (20). Total A. nidulans RNA was obtained by using an RNA Red Fast Prep kit (Bio 101). Southern and Northern gels were transferred to Hybond N+ membranes (Amersham) by using 0.4 and 0.04 M NaOH, respectively. [α-32P]dATP (Bresatec) radioactively labeled DNA probes for hybridization were created by using the random hexanucleotide priming method (36). Automated DNA sequencing was performed at the Australian Genome Research Foundation with plasmid DNA prepared by using a High Pure Plasmid kit (Roche).

Degenerate PCR.

PCR with JOHE876 (5′-CARTGGTAYTTYTGGGGITAYTC-3′) and JOHE881 (5′-TAYTTIARYTTIGTIGCRAARTTRCA-3′) was performed with 100 ng of A. nidulans genomic DNA, 200 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 1× Taq reaction buffer, 10 pmol of each primer, a 1 to 3 mM MgCl2 concentration gradient, and 2 U of Taq polymerase (Promega) in a final volume of 100 μl. The cycling conditions were 94°C for 2 min; 35 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 50°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min; and a final cycle at 72°C for 10 min. A single 0.8-kb band was observed for the 2 mM MgCl2 reaction and, at a reduced intensity, also for the 1.5 and 2.5 mM MgCl2 reactions. The product was cloned into pGEM-T, creating pBJM4476, and was sequenced.

cDNA isolation.

cDNA clones of mepA and meaA were isolated from an A. nidulans λgt10 cDNA library (a kind gift from Greg May, Baylor College, Houston, Tex.). Plaque lifts were probed with the 0.8-kb PCR product from pBJM4476 (mepA) and the 3.5-kb XbaI fragment from pBJM4792 (meaA). A 2-kb EcoRI fragment encompassing the mepA cDNA was subcloned (pBJM5281). A 2.2-kb meaA cDNA was amplified from a hybridizing λgt10 clone by PCR with the λgt10 forward (5′-AGCAAGTTCAGCCTGGTTAAG-3′) and reverse (5′-CTTATGAGTATTTCTTCCAGGGTA-3′) primers and was cloned into pGEM-T to create pBJM5280.

Creation of meaA and mepA deletion mutants.

The meaA deletion construct pBJM4799 was made by inserting a blunted XbaI 3.2-kb argB fragment into end-filled NcoI sites of pBJM4792 (Fig. 1). This construct was transformed into the argB− strain MH9233, and transformants were selected for complementation of arginine auxotrophy. Transformants were screened for methylammonium resistance, and Southern analysis confirmed MH9961 as an meaA deletion mutant. This strain was outcrossed to create the final meaA deletion strain, MH9965.

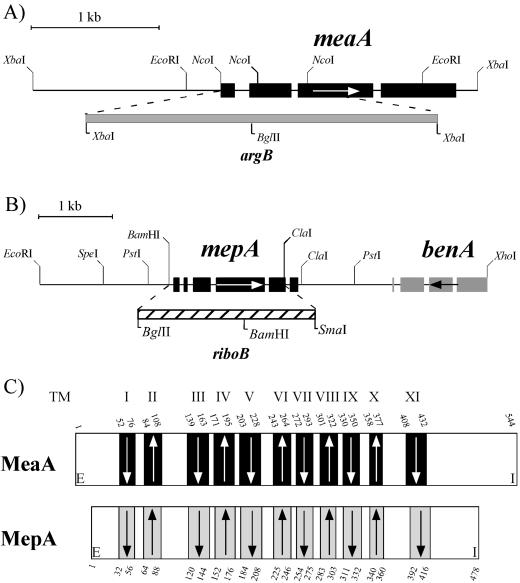

FIG. 1.

mepA and meaA have different gene structures but similar predicted protein secondary structures. (A and B) Exon-intron structures, restriction maps, and gene replacement strategies for meaA (A) and mepA (B) are shown. Black boxes represent exons, and the direction of transcription is indicated by an arrow. The positions in meaA and mepA of the argB and riboB selectable markers, respectively, used for targeted gene replacement are indicated. The portion of the benA gene located on the mepA clone is also shown. (C) meaA and mepA are both predicted to encode an 11-transmembrane-domain protein. The positions of putative transmembrane (TM) helices (shaded boxes numbered above with Roman numerals) and topology were assigned by using the prediction programs HMMTOP (43) and TMHMM (39). These programs gave the same numbers of transmembrane domains and very similar positions, although the helix-to-tail transition coordinates did vary slightly. The coordinates given here for each transmembrane helix are from the HMMTOP output. Arrows represent the direction of each transmembrane helix. The putative extracellular (E) and intracellular (I) locations of the N-terminal and C-terminal tails, respectively, are indicated.

The mepA deletion construct pBJM4798 was made by inserting a BglII/SmaI 2.5-kb riboB fragment into the BamHI and end-filled ClaI sites of pBJM4878, which contains the SpeI/XhoI 5.2-kb mepA fragment (Fig. 1; the 3′ ClaI site is methylated in E. coli). To aid selection and enhance the phenotype of an mepA deletion mutant, transformations were performed with the meaA deletion strain MH9961. Protoplasts were regenerated on nitrate as the sole nitrogen source, and transformants were selected for complementation of riboflavin auxotrophy. Transformants were screened for reduced growth on 2 mM ammonium and for increased resistance to 300 mM methylammonium chloride on media containing 10 mM alanine. Southern analysis identified MH9828 as an mepA deletion mutant. This strain was outcrossed from the meaA deletion background to create the final mepA deletion strain, MH9831.

[14C]methylammonium uptake assays.

Assays were based on previously described methods (15, 33, 34). Cells were grown in liquid ANM (pH 6.5) with 20 mM ammonium at 25°C for 16 h, harvested, washed with nitrogen-free medium, and either assayed immediately (ammonium-sufficient sample) or transferred to nitrogen-free medium and incubated for a further 4 h (nitrogen-starved sample). Mycelium was added to a 250-ml flask containing 50 ml of prewarmed nitrogen-free medium and was incubated with shaking at 30°C for 2 min before the addition of methylammonium (containing 0.5 μCi of [14C]methylamine hydrochloride; Amersham) to a final concentration of 2 μM, 20 μM, 200 μM, 500 μM, 1 mM, 2.5 mM, 5 mM, or 10 mM. At 1-min intervals, 5-ml samples were collected under suction on preweighed Whatman no. 1 filter paper and were washed immediately with 20 ml of cold water. Samples were collected for the first 7 min in the first replicate and then for the first 5 min in the second and third replicates. Samples were dried overnight, and the dry weights of the mycelia were determined. Samples were placed in microcentrifuge tubes, and 1.2 ml of PCS liquid scintillation fluid (Amersham) was added. Tubes were left at room temperature overnight, and then counts were determined for 2 min with a 1121 Rackbeta (LKB, Wallac) liquid scintillation counter. Results were analyzed and kinetic parameters were determined by using GraphPad Prism3 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, Calif.).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The GenBank accession numbers of the A. nidulans meaA and mepA genes are AY049706 and AY049707, respectively.

RESULTS

Cloning of meaA and mepA.

Studies have established that methylammonium uptake occurs via the ammonium system (reviewed in reference 18). At high concentrations (greater than 10 mM; typically 100 mM is used), methylammonium is toxic to A. nidulans. The meaA locus has been implicated in ammonium transport, as the methylammonium-resistant meaA8 mutant was shown to be defective in methylammonium uptake (2, 4). meaA was mapped at 4 to 6 map units from gdhB on linkage group IV (2, 7). An A. nidulans genomic BAC clone which hybridized to a gdhB-containing fragment from pMJH1719 (J. R. Kinghorn and M. J. Hynes, unpublished data) was isolated and used to screen a chromosome IV-specific cosmid library (6). Hybridizing cosmids (W14B12, W22F05, W29E07, W29H04, W1C07, W2G03, W2H03, W4D05, W6G11, W5C12, L5A12, L7C10, L23B01, and L29B05) were cotransformed in pairs into meaA8 mutant MH9288. Complementation of the meaA8 mutation was observed for the cosmid combination of W1C07 and W2G03 by screening for methylammonium sensitivity on ANM containing 100 mM methylammonium and 10 mM alanine. Transformation with individual cosmids showed that W2G03 and not W1C07 complemented the meaA8 mutation. Transformation of a variety of W2G03 restriction digests and subsequently cloned fragments identified a complementing 8.2-kb ClaI clone (pJAF5279). Further subcloning of this fragment produced a final 3.5-kb XbaI clone (pBJM4792) able to complement meaA8. The putative meaA open reading frame was isolated from the meaA8 mutant and sequenced; this procedure identified a single nucleotide substitution predicted to alter the Gln231 codon to a stop codon, producing a truncated protein (S. E. Unkles, personal communication). The presence of such a mutation indicated that the complementing gene isolated was indeed meaA.

Concurrently, PCR with degenerate primers designed on the basis of conserved AMT/MEP sequences was used to isolate similar sequences from A. nidulans. A single 804-bp product which displayed significant sequence identity to MEP/AMT sequences was isolated from A. nidulans wild-type genomic DNA by using primers JOHE876 and JOHE881 (see Materials and Methods for details). Low-stringency Southern hybridization of the cloned PCR product to A. nidulans genomic DNA revealed two distinct hybridization patterns, the fainter of which was identical to that observed for meaA (data not shown). This result indicated that the putative AMT/MEP gene isolated by degenerate PCR (named mepA) and meaA were two different genes. A 6.2-kb EcoRI/XhoI genomic fragment which hybridized to mepA was subcloned from BAC clone 28 M15 to create pBJM4868.

Database analysis of the sequence from the XhoI end of pBJM4868 showed that this region contains a portion of the A. nidulans benA gene (GenBank accession number M17519; Fig. 1). Southern blot hybridization of benA and mepA to A. nidulans genomic DNA verified this association (data not shown), confirming that mepA is located on the same linkage group (VIII) as benA.

meaA and mepA exhibit significant similarity to MEP/AMT sequences.

Comparison of genomic and cDNA sequences showed that the mepA gene is comprised of six exons and five introns and is predicted to encode a 478-amino-acid protein (Fig. 1). The meaA gene structure is quite different; there are only four exons, and the positions of the three introns are not conserved relative to those of mepA (Fig. 1). meaA contains two possible in-frame translation initiation codons and therefore is predicted to encode either a 544- or a 539-amino-acid protein. All coordinates given are from the first ATG codon. MepA and MeaA exhibit 55% amino acid identity (73% similarity) to each other. Eleven putative transmembrane helices were identified for both MeaA and MepA (Fig. 1C) by using prediction programs HMMTOP (43) and TMHMM (39), in agreement with predictions made for other AMT/MEP transporters (22, 41). This analysis showed that the size, spacing, and topology of the putative transmembrane helices were very similar between MepA and MeaA and that the significant size difference between the two proteins was attributable to a larger intracellular C-terminal tail for MeaA (112 amino acids) than for MepA (62 amino acids). MeaA is the largest of the fungal ammonium transporters, although the putative ammonium transporters AMT2, AMT3, and AMT4 from C. elegans are larger (554, 609, and 558 amino acids, respectively; Fig. 2 shows GenBank accession numbers). As the S. cerevisiae Mep2p protein is N glycosylated at a single site in the extracellular N terminus (22), glycosylation of MepA and MeaA also may occur, as an N-glycosylation motif is present at similar locations (N9 and N17, respectively) in both proteins.

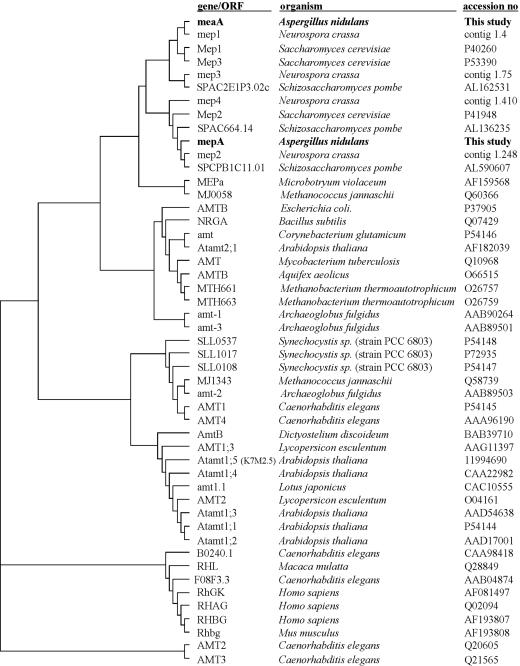

FIG. 2.

Relatedness of MepA and MeaA to known MEP/AMT and rhesus protein sequences. The tree was constructed by the neighbor-joining method (35) with ClustalX (42). Data were corrected for multiple substitutions, and gaps in the alignment were ignored for the tree building. The name of the gene or open reading frame (ORF), the organism, and the GenBank accession number are indicated. N. crassa sequences were identified by database screening, and the contig in which the nucleotide sequence was present is indicated (assembly version 1, Neurospora Sequencing Project, Whitehead Institute/MIT Center for Genome Research, http://www-genome.wi.mit.edu).

The MepA and MeaA protein sequences contain the ammonium transporter motif (Pfam domain PF00909) and display overall similarity to known ammonium transporter sequences. MeaA is 52% identical (73% similar) to Mep1p from S. cerevisiae, 35% identical (61% similar) to E. coli AmtB, and 28% identical (54% similar) to A. thaliana AtAmt1;1. MepA is 50% identical (70.2% similar) to Mep2p from S. cerevisiae, 39% identical (65% similar) to E. coli AmtB, and 30% identical (55% similar) to A. thaliana AtAmt1:1. A neighbor-joining tree (35) of MEP/AMT-related proteins (Fig. 2) revealed that the protein sequences generally clustered in accordance with phylogenies, including a clear cluster of fungal MEP/AMT sequences which consisted of two main subclasses. In one subclass, MeaA groups with the S. cerevisiae Mep1p and Mep3p permeases, and in the other, MepA groups with Mep2p (Fig. 2). Based on this analysis, mepA may be predicted to encode a high-affinity ammonium transporter similar to Mep2p and meaA may be predicted to encode a Mep1p-like permease which constitutes the major ammonium uptake system of the cell. Consistent with these notions, both meaA and MEP1 mutants display a methylammonium resistance phenotype.

Phenotypic analysis of meaA and mepA deletion mutants.

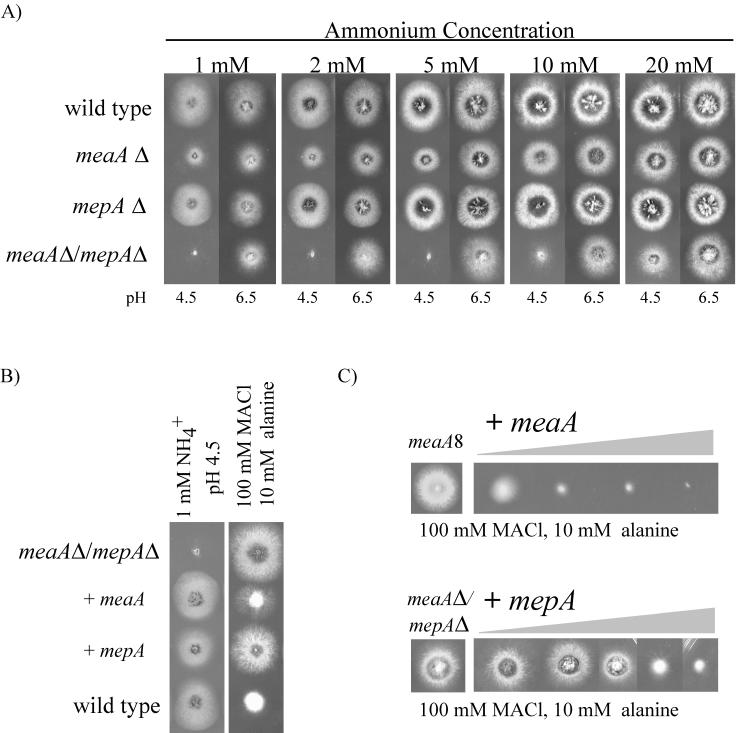

meaA and mepA deletion mutants (MH9965 and MH9831, respectively) were created by the gene replacement strategies outlined in Fig. 1 and described in Materials and Methods. The mepA meaA double-deletion mutant MH9829 was generated by genetic crosses. To assess the role of these genes in ammonium uptake, the growth of the mutants on a range of ammonium concentrations was examined (Fig. 3). As the ammonium ion (NH4+) is thought to be the substrate for AMT/MEP permeases whereas ammonia (NH3) can freely diffuse across biological membranes (reviewed in references 18 and 44), growth tests were also performed with low-pH media to reduce NH3 diffusion as a mechanism of uptake (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Phenotypic analysis of meaA and mepA single- and double-deletion mutants. (A) Growth on a range of ammonium concentrations. At each ammonium concentration, tests were performed at pH 4.5 and pH 6.5. (B) Complementation analysis of the meaA mepA double-deletion mutant. Transformants were tested for both growth on ammonium and sensitivity to methylammonium (MACl). (C) Multiple-copy analysis of the meaA and mepA genes. An increase in the sensitivity of the transformants to methylammonium (MACl), depending on the copy number of the gene, is shown. The increase in copy number is represented by the grey triangle.

Deletion of both putative ammonium permease genes eliminated growth on media containing 1 to 5 mM ammonium at pH 4.5, but at pH 6.5 reduced growth compared to that of the wild type was seen (Fig. 3). As the wild-type and single-deletion strains grow on ammonium at pH 4.5, this growth difference was not an effect of low pH but was an NH4+ transport-specific phenotype, a finding which is also indicated by wild-type growth of the mepA meaA double-deletion mutant on nitrogen sources other than ammonium at pH 4.5 (data not shown). Growth at pH 4.5 was observed for the mepA meaA double-deletion mutant on 10 mM ammonium and higher concentrations, a finding which may be attributable to nonspecific ammonium uptake at higher concentrations or other uptake systems that may be present in A. nidulans. The S. cerevisiae MEP1 MEP2 MEP3 triple-deletion mutant exhibited a similar growth pattern on ammonium (24).

The single-deletion mutants showed contrasting phenotypes. On all ammonium concentrations tested and at either pH, the mepA deletion mutant displayed wild-type growth whereas the meaA deletion mutant exhibited substantially poorer growth, which was particularly evident at pH 4.5. These results indicate that MeaA constitutes the major ammonium uptake system, a notion consistent with meaA mutants displaying methylammonium resistance due to reduced uptake of the toxic substrate. Deletion of the mepA gene did not confer methylammonium resistance, although the meaA mepA double-deletion mutant exhibited slightly greater resistance than the meaA deletion mutant in the presence of high methylammonium concentrations (data not shown).

Complementation of the ammonium growth defect and effects of multiple gene copies.

Introduction of meaA (pBJM4792) into the mepA meaA double-deletion mutant conferred wild-type growth on 1 mM ammonium (pH 4.5) and methylammonium sensitivity, as observed for the mepA deletion mutant (Fig. 3B). When mepA (pBJM4868) was introduced into the double-deletion mutant, growth and methylammonium resistance consistent with the meaA deletion phenotype were seen (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, cotransformation of meaA (pBJM4792) and pI4 (PyroA+) into the meaA8 single-deletion mutant and into the mepA meaA double-deletion mutant resulted in a number of transformants with hypersensitivity to methylammonium toxicity (Fig. 3C). Southern blot analysis showed that increased sensitivity was dependent on the copy number of the transformed gene (data not shown). As the copy number of meaA increased, growth on medium containing 100 mM methylammonium and 10 mM alanine decreased, with the highest-copy-number transformant displaying no growth on this medium (Fig. 3C). Growth in the absence of methylammonium was not affected. This hypersensitivity to methylammonium was consistent with increased uptake of the toxic ammonium analogue due to multiple copies of the meaA gene resulting in overexpression of the protein. There was, however, no apparent increase in the growth of the cells on medium containing ammonium as the sole nitrogen source (data not shown). Multiple copies of mepA (pBJM4868) conferred wild-type methylammonium sensitivity to the mepA meaA double-deletion mutant parent, indicating that, when overexpressed, mepA is capable of complementing the meaA deletion mutant (Fig. 3C). However, it should be noted that methylammonium hypersensitivity was not observed for mepA multicopy transformants.

[14C]methylammonium uptake analysis.

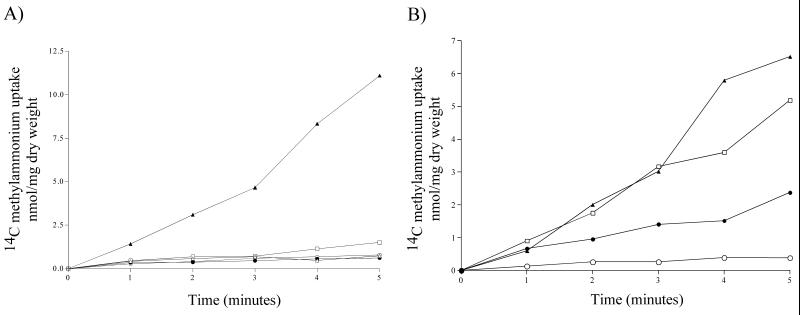

To confirm that meaA and mepA encode functional (methyl)ammonium transporters and to determine their relative affinities, [14C]methylammonium uptake in the wild-type strain and in the respective deletion mutant strains was measured. These assays (described in Materials and Methods) were based on those previously used to investigate methylammonium uptake in A. nidulans (9, 15, 33).

When grown in 20 mM ammonium, the wild-type sample displayed minimal methylammonium transport activity compared to samples which were subjected to a 4-h nitrogen starvation period (Fig. 4A). This result is in agreement with previous results obtained for A. nidulans and other organisms (9, 18, 32, 44). The meaA and mepA single- and double-deletion mutants also showed very low activity in ammonium-grown mycelium, although uptake in the meaA deletion mutant appeared slightly elevated (Fig. 4A).

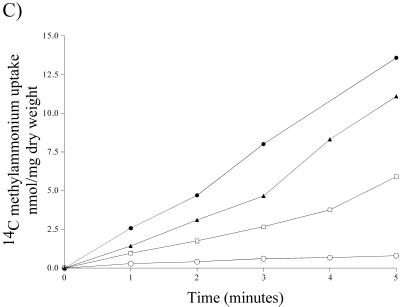

FIG. 4.

[14C]methylammonium uptake of meaA and mepA single- and double-deletion mutants. (A) [14C]methylammonium transport activity of the wild type (▵), meaA deletion mutant (□), mepA deletion mutant (•), and meaA mepA double-deletion mutant (○) grown in 20 mM ammonium compared to that of the wild type subjected to a 4-h nitrogen starvation period (▴). The final methylammonium concentration was 1 mM. (B and C) Methylammonium transport activity of nitrogen-starved samples at final methylammonium concentrations of 0.2 mM (B) and 1 mM (C). The symbols for the strains are the same as those for panel A.

The meaA and mepA single-deletion mutant samples which were nitrogen starved for 4 h displayed different methylammonium uptake patterns depending on the methylammonium concentration used in the assay (Fig. 4B and C). At low concentrations (0.2 mM methylammonium), the meaA deletion mutant (expressing only MepA activity) had methylammonium transport activity similar to that of the wild type, in contrast to the mepA deletion mutant (expressing only MeaA activity), which had reduced activity (Fig. 4B); these results indicated that MepA has a higher affinity than MeaA. At 1 mM methylammonium, the opposite was observed, with the transport activity of the mepA deletion mutant exceeding that of the meaA deletion mutant (Fig. 4C). A similar pattern is seen for S. cerevisiae, with the sum of the individual Mep ammonium transport activities being higher than the activity observed for the wild type, and it was recently proposed that there is cross regulation between S. cerevisiae Mep proteins (25). The elevation of MeaA activity seen in the mepA deletion mutant may suggest that modulation of MeaA activity by MepA occurs. As shown in Fig. 5, the uptake rates and capacities for the two permeases are quite different. The curve for the meaA deletion strain flattens at methylammonium concentrations of greater than 1 mM, indicating that MepA displays optimal activity at low substrate concentrations (Fig. 5A), whereas the mepA deletion strain displays a steady curve and a final velocity about 10-fold greater than that observed for the meaA deletion strain (Fig. 5B).

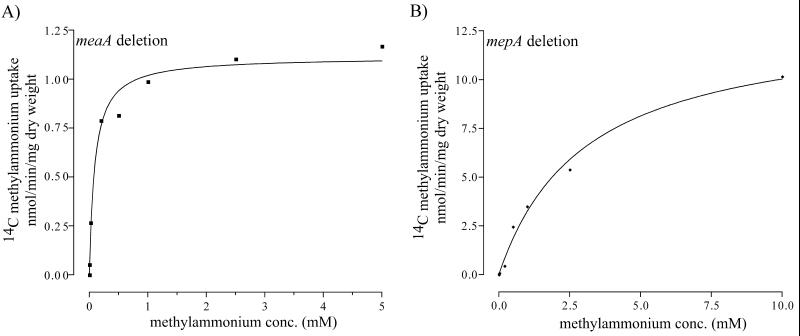

FIG. 5.

Velocity-substrate concentration curves for MepA and MeaA. [14C]methylammonium uptake rates measured at the substrate concentrations (conc.) indicated (see Materials and Methods) are shown for the meaA and mepA deletion mutants.

The mepA meaA double-deletion mutant did not display significant methylammonium transport activity at any concentration tested. Transport rates of 0.175 ± 0.010 and 0.249 ± 0.021 nmol/min/mg of dry weight at 1 and 2.5 mM methylammonium, respectively, had errors similar to those calculated for the uptake rates for the mepA deletion strain at the same concentrations, 2.88 ± 0.155 and 5.38 ± 0.179 nmol/min/mg of dry weight, respectively. The basal levels of methylammonium uptake measured for the meaA mepA deletion strain may have been due to diffusion, as similar rates were seen for the ammonium-sufficient sample and were comparable to those observed for the wild type when competed with 5 mM ammonium (data not shown).

The kinetic parameters for [14C]methylammonium transport were determined for both MepA and MeaA. In the meaA deletion mutant, MepA had an apparent Km of 44.3 ± 0.008 μM methylammonium and a Vmax of 0.917 ± 0.035 nmol/min/mg of dry weight. The MepA Km is similar to that of the high-affinity methylammonium transporter (Km, 13 μM) characterized previously for A. nidulans (9) and about sixfold lower than that of the S. cerevisiae Mep2p permease (Km, 250 μM) (12, 24). The apparent Km for MeaA was 3.04 ± 0.49 mM methylammonium, and the Vmax was 13.09 ± 0.8578 nmol/min/mg of dry weight, values which are similar to those of the S. cerevisiae Mep1p permease (Km, 2 mM; Vmax, 50 nmol/min/mg) (12, 26).

meaA and mepA display different expression profiles.

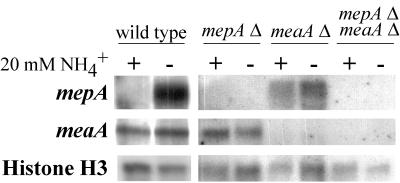

The expression of mepA and meaA was investigated by using Northern blot analysis (Fig. 6). The expression of mepA was not detected for cells grown in ammonium-sufficient conditions but was observed for cells which were nitrogen starved for 4 h (Fig. 6). The expression of mepA only in ammonium-limiting conditions is consistent with a role for the high-affinity ammonium transporter in scavenging low concentrations of ammonium. As shown by the ammonium growth defect of the meaA deletion mutant, meaA is required for optimal growth in ammonium-sufficient conditions. Therefore, in contrast to that of mepA, the expression of meaA was readily detected in cells grown on ammonium and increased only slightly when the cells were starved for nitrogen (Fig. 6). The presence of the meaA transcript in ammonium-sufficient conditions contrasts with the results of the [14C]methylammonium uptake analysis, which indicated no significant MeaA transport activity in ammonium-sufficient conditions. These results indicate that high intracellular ammonium levels may inhibit permease activity.

FIG. 6.

Northern blot analysis of meaA and mepA expression. RNA was isolated from wild-type (MH1), mepA single-deletion (MH9861), meaA single-deletion (MH9965), and mepA meaA double-deletion (MH9829) strains. Mycelium was grown in ANM with 20 mM ammonium at 37°C for 16 h (+) and then transferred to nitrogen-free medium for 4 h (−). Northern blots were hybridized with probes specific for mepA, meaA, or A. nidulans histone H3 as a loading control (13).

As mepA was not expressed under ammonium-sufficient conditions but growth on ammonium was observed for the meaA deletion mutant, the expression of mepA in an meaA mutant background was investigated (Fig. 6). This analysis revealed that mepA was now also expressed in ammonium-sufficient conditions when MeaA function was absent. No noticeable difference in meaA expression compared to wild type was seen in the mepA deletion mutant, and no expression of either gene was detected for the mepA meaA double-deletion mutant (Fig. 6).

DISCUSSION

This article reports the isolation and characterization of two genes, meaA and mepA, which are proposed to encode the two ammonium transport activities previously suggested for A. nidulans (4, 9). MeaA and MepA show significant sequence identity to each other and to ammonium transporters from other organisms and represent two new members of the MEP/AMT family. MeaA appears to be the major ammonium transporter for the cell, as the meaA deletion mutant shows substantially reduced growth on media containing less than 10 mM ammonium as the sole nitrogen source. Consistent with a significant reduction of substrate influx, the meaA deletion mutant also displays methylammonium resistance. The residual growth of the meaA deletion mutant on ammonium was shown to be due to MepA activity, although deletion of mepA alone did not affect growth on the ammonium concentrations tested and did not confer methylammonium resistance.

The growth of the mepA meaA double-deletion mutant and the meaA single-deletion mutant improved as the pH of the ammonium growth media was raised from 4.5 to 6.5. These results are probably due to diffusion of NH3, which is prevented at pH 4.5 because of protonation, and are in agreement with similar data obtained for other organisms. The doubling time of an E. coli amtB mutant at low ammonium concentrations was greatly increased at pH 5 compared to pH 7, while the growth of the wild type was unaffected (40). Growth of the S. cerevisiae MEP triple mutant was observed on 1 mM NH4+ at pH 7.1 but not at pH 6.1 (40). Contrary to the conclusions of Soupene et al. (40), these results indicate that NH4+ is the substrate for the transporters. Electrophysiological studies with fungi, bacteria, and plants have shown that ammonium uptake is related to strong depolarization of the membrane potential, indicating that NH4+ and not NH3 (because diffusion is not associated with depolarization) is transported (18, 37, 44). Experiments with S. cerevisiae and Corynebacterium glutamicum revealed that the Km for methylammonium was not altered with a change in pH, indicating that methylammonium and not methylamine is transported (5, 27).

The lack of growth of the mepA meaA double-deletion mutant on ammonium concentrations of less than 10 mM (at pH 4.5) implies that MepA and MeaA are the only ammonium transport activities which function under these conditions in A. nidulans. However, even at pH 4.5, some growth of the mepA meaA double mutant is observed at 10 and 20 mM ammonium. This growth could be due to nonspecific uptake of ammonium at high ammonium concentrations; alternatively, other uptake systems may be present in A. nidulans. The lack of growth of the mepA meaA double-deletion mutant on low ammonium concentrations indicates that if any other ammonium transporters are present in A. nidulans, they have a very low affinity. This notion is consistent with the kinetic analysis, which did not detect significant [14C]methylammonium uptake for the mepA meaA double-deletion mutant. The S. cerevisiae Mep3p transporter has such a low affinity for ammonium that it is unable to transport [14C]methylammonium (24).

Consistent with the ammonium growth phenotypes, MepA and MeaA display different affinities for methylammonium, with MepA being a higher-affinity permease (Km, 44.3 μM) than MeaA (Km, 3.04 mM). Ammonium competition experiments for A. nidulans have indicated that the Km for ammonium (assuming Km ☰ Ki) is approximately 20% that for methylammonium (9). Therefore, the Kms (ammonium) may be estimated to be 9 μM for MepA and 610 μM for MeaA. The velocity-substrate plots and the apparent Vmax values for MeaA (13.09 nmol/min/mg of dry weight) and MepA (0.917 nmol/min/mg of dry weight) show that MeaA has a higher rate of (methyl)ammonium transport than MepA. However, differences in the actual relative amounts of active MepA and MeaA would influence the apparent maximum velocities of the two transporters, as shown by our analysis of multicopy transformants. When overexpressed in the mepA meaA deletion strain, MepA is able to complement the methylammonium resistance phenotype conferred by the absence of MeaA activity. Similarly, meaA8 or mepA meaA deletion strains with a high copy number for the meaA gene display hypersensitivity to methylammonium due to increased uptake of the toxic analogue.

Together, these results indicate that MeaA and MepA have different physiological roles. MeaA appears to be the major source of ammonium influx for the cell; accordingly, the expression of meaA is seen in both ammonium-sufficient and nitrogen-starved samples. In contrast, MepA is a higher-affinity transporter which is expressed only in nitrogen-limiting conditions and probably acts to scavenge ammonium. The expression profile for mepA is typical of that for genes subject to nitrogen metabolite repression which, in A. nidulans, is mediated by the GATA transcription factor AreA (3, 17, 19). Analysis of a 1-kb 5′ untranslated region of mepA identified six putative AreA binding sites (HGATAR). The expression of mepA in ammonium-sufficient conditions was observed for the meaA deletion mutant. This result is consistent with the results of previous studies in which other nitrogen-regulated activities, such as nitrate reductase, are partially derepressed in meaA mutants because of reduced ammonium uptake (2).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Australian Research Council and the awards of a Melbourne Research Scholarship to B.J.M. and an Australian Postgraduate Award to J.A.F.

We thank Joseph Heitman (Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Durham, N.C.) for kindly providing the degenerate PCR primers.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andrianopoulos, A., and M. J. Hynes. 1988. Cloning and analysis of the positively acting regulatory gene amdR from Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8: 3532–3541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arst, H. N., Jr., and D. J. Cove. 1969. Methylammonium resistance in Aspergillus nidulans. J. Bacteriol. 98: 1284–1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arst, H. N., Jr., and D. J. Cove. 1973. Nitrogen metabolite repression in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Gen. Genet. 126: 111–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arst, H. N., Jr., and M. M. Page. 1973. Mutants of Aspergillus nidulans altered in the transport of methylammonium and ammonium. Mol. Gen. Genet. 121: 239–245. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bogonez, E., A. Machado, and J. Satrustegui. 1983. Ammonia accumulation in acetate-growing yeast. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 733: 234–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brody, H., J. Griffith, A. J. Cuticchia, J. Arnold, and W. E. Timberlake. 1991. Chromosome-specific recombinant DNA libraries from the fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Nucleic Acids Res. 19: 3105–3109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clutterbuck, A. J. 1997. The validity of the Aspergillus nidulans linkage map. Fungal Genet. Biol. 21: 267–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clutterbuck, A. J. 1974. Aspergillus nidulans genetics, p. 447–510. In R. C. King (ed.), Handbook of genetics, vol. 1. Plenum Publishing Corp., New York, N.Y.

- 9.Cook, R. J., and C. Anthony. 1978. The ammonia and methylamine transport system of Aspergillus nidulans. J. Gen. Microbiol. 109: 265–274. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costanzo, M. C., M. E. Crawford, J. E. Hirschman, J. E. Kranz, P. Olsen, L. S. Robertson, M. S. Skrzypek, B. R. Braun, K. L. Hopkins, P. Kondu, C. Lengieza, J. E. Lew-Smith, M. Tillberg, and J. I. Garrels. 2001. YPD™, PombePD™, and WormPD™: model organism volumes of the BioKnowledge™ library, an integrated resource for protein information. Nucleic Acids Res. 29: 75–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cove, D. J. 1966. The induction and repression of nitrate reductase in the fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 113: 51–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dubois, E., and M. Grenson. 1979. Methylamine/ammonia uptake systems in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: multiplicity and regulation. Mol. Gen. Genet. 175: 67–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ehinger, A., S. H. Denison, and G. S. May. 1990. Sequence, organization and expression of the core histone genes of Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Gen. Genet. 222: 416–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gazzarrini, S., L. Lejay, A. Gojon, O. Ninnemann, W. B. Frommer, and N. von Wiren. 1999. Three functional transporters for constitutive, diurnally regulated, and starvation-induced uptake of ammonium into Arabidopsis roots. Plant Cell 11: 937–948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hackette, S. L., G. E. Skye, C. Burton, and I. H. Segel. 1970. Characterization of an ammonium transport system in filamentous fungi with methylammonium-14C as the substrate. J. Biol. Chem. 245: 4241–4250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howitt, S. M., and M. K. Udvardi. 2000. Structure, function and regulation of ammonium transporters in plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1465: 152–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hynes, M. J. 1975. Studies on the role of the areA gene in the regulation of nitrogen catabolism in Aspergillus nidulans. Aust. J. Biol. Sci. 28: 301–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kleiner, D. 1981. The transport of NH3 and NH4+ across biological membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 639: 41–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kudla, B., M. X. Caddick, T. Langdon, N. M. Martinez-Rossi, C. F. Bennett, S. Sibley, R. W. Davies, and H. N. Arst, Jr. 1990. The regulatory gene areA mediating nitrogen metabolite repression in Aspergillus nidulans. Mutations affecting specificity of gene activation alter a loop residue of a putative zinc finger. EMBO J. 9: 1355–1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee, S., and J. Taylor. 1990. Isolation of DNA from fungal mycelia and single spores, p. 282–287. In M. A. Innis, D. H. Gelfand, and T. J. White (ed.), PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, Calif.

- 21.Lorenz, M. C., and J. Heitman. 1998. The MEP2 ammonium permease regulates pseudohyphal differentiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 17: 1236–1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marini, A. M., and B. Andre. 2000. In vivo N-glycosylation of the Mep2 high-affinity ammonium transporter of Saccharomyces cerevisiae reveals an extracytosolic N-terminus. Mol. Microbiol. 38: 552–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marini, A. M., G. Matassi, V. Raynal, B. Andre, J. P. Cartron, and B. Cherif-Zahar. 2000. The human Rhesus-associated RhAG protein and a kidney homologue promote ammonium transport in yeast. Nat. Genet. 26: 341–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marini, A. M., S. Soussi-Boudekou, S. Vissers, and B. Andre. 1997. A family of ammonium transporters in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17: 4282–4293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marini, A. M., J. Y. Springael, W. B. Frommer, and B. Andre. 2000. Cross-talk between ammonium transporters in yeast and interference by the soybean SAT1 protein. Mol. Microbiol. 35: 378–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marini, A. M., S. Vissers, A. Urrestarazu, and B. Andre. 1994. Cloning and expression of the MEP1 gene encoding an ammonium transporter in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 13: 3456–3463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meier-Wagner, J., L. Nolden, M. Jakoby, R. Siewe, R. Kramer, and A. Burkovski. 2001. Multiplicity of ammonium uptake systems in Corynebacterium glutamicum: role of Amt and AmtB. Microbiology 147: 135–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mohana, K., and E. R. Shanmugasundaram. 1978. Pyridoxine and its relation to lipids. Studies with pyridoxineless mutants of Aspergillus nidulans. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 24: 397–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Montesinos, M. L., A. M. Muro-Pastor, A. Herrero, and E. Flores. 1998. Ammonium/methylammonium permeases of a Cyanobacterium. Identification and analysis of three nitrogen-regulated amt genes in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. J. Biol. Chem. 273: 31463–31470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ninnemann, O., J. C. Jauniaux, and W. B. Frommer. 1994. Identification of a high affinity NH4+ transporter from plants. EMBO J. 13: 3464–3471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Osmani, A. H., G. S. May, and S. A. Osmani. 1999. The extremely conserved pyroA gene of Aspergillus nidulans is required for pyridoxine synthesis and is required indirectly for resistance to photosensitizers. J. Biol. Chem. 274: 23565–23569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pateman, J. A., E. Dunn, J. R. Kinghorn, and E. C. Forbes. 1974. The transport of ammonium and methylammonium in wild type and mutant cells of Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Gen. Genet. 133: 225–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pateman, J. A., J. R. Kinghorn, E. Dunn, and E. Forbes. 1973. Ammonium regulation in Aspergillus nidulans. J. Bacteriol. 114: 943–950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roon, R. J., H. L. Even, P. Dunlop, and F. L. Larimore. 1975. Methylamine and ammonia transport in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Bacteriol. 122: 502–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saitou, N., and M. Nei. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4: 406–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 37.Slayman, C. L. 1977. Energetics and control of transport in Neurospora, p. 69–86. In A. M. Jungreis, T. K. Hodges, A. Kleinzeller, and S. G. Schultz (ed.), Water relations in membrane transport in plants and animals. Academic Press, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 38.Sohlenkamp, C., M. Shelden, S. Howitt, and M. Udvardi. 2000. Characterization of Arabidopsis AtAMT2, a novel ammonium transporter in plants. FEBS Lett. 467: 273–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sonnhammer, E. L., G. von Heijne, and A. Krogh. 1998. A hidden Markov model for predicting transmembrane helices in protein sequences. Proc. Int. Conf. Intell. Syst. Mol. Biol. 6: 175–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soupene, E., L. He, D. Yan, and S. Kustu. 1998. Ammonia acquisition in enteric bacteria: physiological role of the ammonium/methylammonium transport B (AmtB) protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95: 7030–7034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thomas, G. H., J. G. Mullins, and M. Merrick. 2000. Membrane topology of the Mep/Amt family of ammonium transporters. Mol. Microbiol. 37: 331–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22: 4673–4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tusnady, G. E., and I. Simon. 1998. Principles governing amino acid composition of integral membrane proteins: application to topology prediction. J. Mol. Biol. 283: 489–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.von Wiren, N., S. Gazzarrini, A. Gojon, and W. B. Frommer. 2000. The molecular physiology of ammonium uptake and retrieval. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 3: 254–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]