Abstract

We here introduce a novel bioreducible polymer-based gene delivery platform enabling widespread transgene expression in multiple brain regions with therapeutic relevance following intracranial convection-enhanced delivery. Our bioreducible nanoparticles provide markedly enhanced gene delivery efficacy in vitro and in vivo compared to non-biodegradable nanoparticles primarily due to the ability to release gene payloads preferentially inside cells. Remarkably, our platform exhibits competitive gene delivery efficacy in a neuron-rich brain region compared to a viral vector under previous and current clinical investigations with demonstrated positive outcomes. Thus, our platform may serve as an attractive alternative for intracranial gene therapy of neurological disorders.

Keywords: brain gene therapy, bioreducible polymer, brain extracellular matrix, intracranial administration, polymeric nanoparticle

Graphical Abstract

We previously demonstrated that gene delivery nanoparticles (NPs) composed of polyethylene glycol (PEG) surface coating and branched polyethylenimine (bPEI)/plasmid DNA (pDNA) complex core provided widespread transgene expression in healthy and tumor-bearing rodent brains following intracranial administration via convection enhanced delivery (CED).1, 2 Such a performance was attributed to the ability of PEGylated NPs to resist adhesive interactions with negatively charged brain extracellular matrix (ECM) and to retain small particle diameters in the physiological brain environment, thereby enabling their efficient penetration through the sticky brain ECM pores.1–4 In contrast, un-PEGylated bPEI/pDNA NPs were unable to do so despite the pressure-driven flow provided by CED which essentially facilitates particle dispersion in the brain.5 Nevertheless, we note that the high molecular weight (MW) bPEI included in PEG/bPEI/pDNA NPs harbors safety concerns due to its highly positive charge content and non-biodegradable nature which potentially result in long-term brain residency and cytotoxicity.6, 7

To this end, we sought to develop brain-permeable gene delivery NPs based on polymers providing timely and controlled degradation and clearance in physiological environments. Specifically, we here engineered PEG-coated brain-permeable NPs based on bioreducible polymers. Conventional hydrolytic polymers degrade in any aqueous environment over time, likely leading to premature or delay payload release.8, 9 In contract, bioreducible polymers or other carrier materials degrade preferentially in reducing environments, such as inside cells, to facilitate intracellular release of pDNA payloads to enhance transgene expression while minimizing cytotoxicity.10–13 Bioreducible PEI (rPEI) polymers were newly synthesized and utilized to formulate un-PEGylated and PEGylated pDNA-loaded NPs, rPEI/pDNA and PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs, respectively. We then carefully characterized these NPs and investigated their ability to mediate transgene expression in rodent brains following CED, in comparison to our first-generation non-biodegradable NPs (i.e., PEG/bPEI/pDNA NPs) and adeno-associate virus serotype 2 (AAV2).

The rPEI was synthesized by Michael addition reaction between 2.5 kDa linear PEI hydrochloride and N,N-cystaminebisacrylamide at a PEI-to-linker molar ratio of 4:1, and PEG-conjugated PEI (PEG-PEI) was synthesized by coupling reaction between 2.5 kDa linear PEI hydrochloride and 5 kDa methoxy PEG N-hydroxysuccinimide at a PEG-to-PEI molar ratio of 3:1 (Figure S1). The polymer solutions were extensively dialyzed, lyophilized, dissolved in DNase-free ultrapure water, and stored at −20 °C until use. The MW of rPEI was determined by size exclusion chromatography to be 10–12 kDa with a low polydispersity index value of 1.23, and we confirmed the degradation of rPEI in a reducing environment (Figure S2). To engineer un-PEGylated bioreducible NPs carrying pDNA, pDNA was mixed with the newly synthesized rPEI at a nitrogen-to-phosphate (N/P) ratio of 18. PEGylated bioredubicle NPs carrying pDNA were prepared at an identical N/P ratio by mixing pDNA and a mixture of rPEI and PEG-PEI where 25% and the rest of the amines (i.e., nitrogens) were contributed by rPEI and PEG-PEI, respectively. Non-biodegradable bPEI/pDNA and PEG/bPEI/pDNA NPs were prepared as previously described.2

We next conducted physicochemical characterization of NPs. rPEI/pDNA and PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs exhibited spherical morphology with hydrodynamic diameters of 72.1 ± 3.9 nm and 54.4 ± 4.3 nm, respectively (Figure 1A and Table S1). While the ζ-potential of rPEI/pDNA was 36 ± 0.6 mV, that of PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs was 5.2 ± 0.4 mV, indicating that PEG effectively shielded the highly positive surface charge of rPEI/pDNA NPs (Figure 1A and Table S1). Importantly, we confirmed that physicochemical properties of PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs were retained at non-reducing environment and room temperature at least up to 2 weeks (Table S1). Physicochemical properties of PEG/bPEI/pDNA NPs were comparable to those of PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs, with hydrodynamic diameter and ζ-potential of 56.5 ± 6.2 nm and 3.3 ± 1.3 mV, respectively (Table S1). We then confirmed with gel electrophoretic migration assay that pDNA payloads were successfully compacted into rPEI/pDNA and PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs (Figure 1B). Similar to our previous observation with PEG/bPEI/pDNA NPs,2 PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs showed excellent colloidal stability in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) at 37 °C at least up to 8 hours, but rPEI/pDNA NPs exhibited instantaneous increases in their diameters to and beyond 1 μm upon initiating the incubation (Figure 1C). We next investigated whether pDNA payloads were preferentially released from PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs in a reducing environment. We found that incubation of PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs in 3 mg/mL 1,4-dithiothreitol (DTT) facilitated the payload releases in presence of heparin at 30–100 μg/mL (Figure 1D and 1E). In contrast, the payload release from bPEI/pDNA NPs was virtually identical regardless of the presence of DTT, underscoring that the perturbation of redox balance did not affect the payload release from the non-biodegradable NPs (Figure S3). Collectively, PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs provided near-neutral surface charge, robust physiological colloidal stability, and preferential pDNA payload release in a reducing environment.

Figure 1. PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs retain colloidal stability in a physiologically relevant condition and release pDNA payloads preferentially in a reducing environment.

(A) Representative transmission electron micrographs of rPEI/pDNA (top) and PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs (bottom). Scale bar = 200 nm. (B) Electrophoretic migration assay showing the compaction of pDNA by rPEI or PEG/rPEI NPs. Lane 1:DNA ladder; 2:pDNA; 3:rPEI/pDNA NPs; 4:PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs. (C) Colloidal stability of rPEI/pDNA and PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs incubated in aCSF at 37 °C for up to 8 hours. (D) Electrophoretic migration assay showing the decompaction of pDNA from PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs after a one-hour incubation in heparin solutions at different concentrations supplemented with or without 3 mg/mL DTT at 37 °C. Lane 1:pDNA; 2:PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs; 3–8:PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs incubated in 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, and 100 μg/mL heparin solution; 9:PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs in 3 mg/mL DTT; 10–15:PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs in 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, and 100 μg/mL heparin solution supplemented with 3 mg/mL DTT. (E) Image-based analysis of the pDNA fluorescence intensity profile on lanes 1, 2, 7, and 14 in Figure 1D. Pixels of 0 – 100 represent the location of wells of the gel.

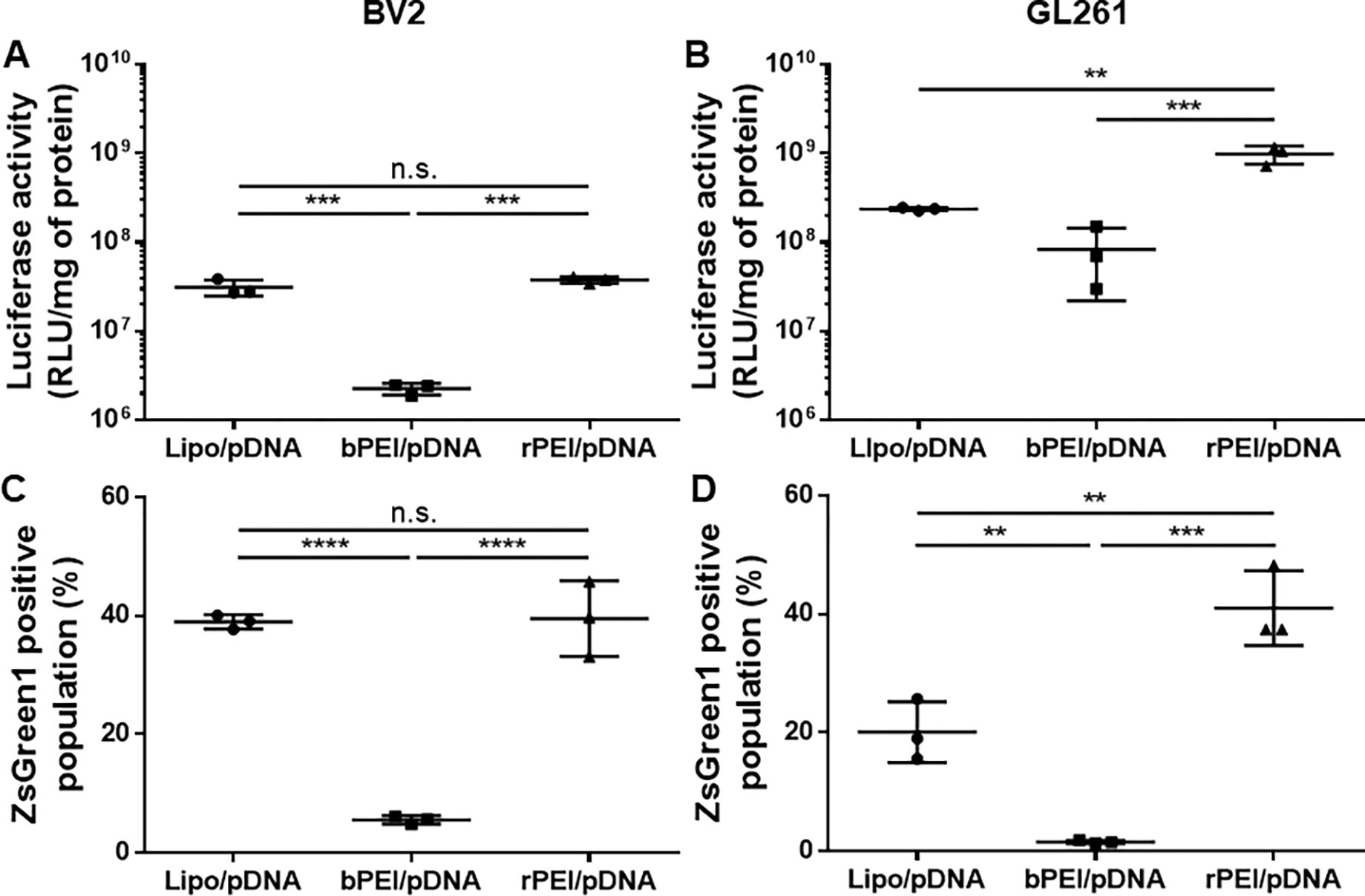

We then tested whether the bioreducible property of rPEI/pDNA NPs, due to their ability to promote intracellular payload release, resulted in enhanced in vitro transfection in BV2 microglial and GL261 glioma cells in comparison to bPEI/pDNA. rPEI/pDNA NPs carrying luciferase-expressing pDNA provided at least one order of magnitude greater luciferase activity, a measure of luciferase transgene expression, compared to bPEI/pDNA NPs carrying the same payload in both cell types (Figure 2A and 2B). Likewise, rPEI/pDNA NPs carrying ZsGreen1-expressing pDNA provided markedly greater ZsGreen1-positive cell percentages of BV2 (39.7% ± 6.4%) and GL261 (41.0% ± 6.3%) compared to bPEI/pDNA NPs carrying the same payload which exhibited the ZsGreen1-positive cell percentages of 5.7% ± 0.7% and 1.5% ± 0.3% in the respective cells (Figure 2C and 2D). Of note, rPEI polymers previously synthesized to possess different chemical structures and MWs were shown to provide significantly increased transfection efficiency compared to 25 kDa bPEI in various non-brain human cell lines.14, 15 Interestingly, rPEI/pDNA NPs showed significantly greater transfection efficiency compared to Lipofectamine™ 2000 in GL261 cells, but not in BV2 cells. The difference observed in GL261 and BV2 cells may reflect the upregulation of intracellular reducing agents in glioblastoma, including glutathione.16, 17 To this end, inherent intracellular redox status of individual cells may serve as a predictive factor for the performance of bioreducible gene delivery NPs, such as rPEI/pDNA NPs.

Figure 2. rPEI/pDNA NPs provide significantly greater in vitro transfection efficiency compared to bPEI/pDNA NPs in BV2 and GL261 cells.

Luciferase activity measured in (A) BV2 and (B) GL261 cells at 48-hour post-treatment of with various gene delivery NPs carrying luciferase-expressing pDNA. Percentage of ZsGreen1-positive cell population measured in (C) BV2 and (D) GL261 cells at 48-hour post-treatment with various gene delivery NPs carrying ZsGreen1-expressing pDNA. Data represent mean ± S.D (n = 3). **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 (One-way ANOVA).

To compare the ability of rPEI/pDNA and PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs to distribute in brain parenchyma in vivo, we prepared NPs carrying Cy3-labeled pDNA for microscopic observation. We infused either NPs into C57BL/6 mouse brain striatum via CED and harvested the brain tissues 30 minutes after the administration. As shown by the representative 3D-rendered images, PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs provided markedly greater striatal distribution compared to rPEI/pDNA (Figure 3A). Quantitatively, the volumetric distribution of rPEI/pDNA and PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs was 2.6 ± 0.8 mm3 and 12.7 ± 1.9 mm3, respectively (Figure 3B). The finding underscores that shielding of the positively charged particle surfaces with PEG resulted in reduced particle adhesive interactions with, and thus enhanced particle penetration through, the brain ECM, as demonstrated in previous studies.1, 2, 18

Figure 3. PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs exhibit markedly greater volumetric distribution of NPs and transgene expression compared to rPEI/pDNA NPs and overall levels of transgene expression compared to rPEI/pDNA and non-biodegradable PEG/bPEI/pDNA NPs in healthy mouse striatum following CED.

Cy3-labeled pDNA, ZsGreen1- or luciferase-expressing pDNA was packaging in gene delivery NPs. (A) Representative 3D images showing volumetric distribution of Cy3-labeled rPEI/pDNA (left) and PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs (right) in healthy mouse striatum following intracranial infusion via CED. Cy3-labeled pDNA (red) was packaged in gene delivery NPs for microscopic observation. Scale bar = 500 μm. (B) Volume of NP distribution in mouse striatum. Data represent mean ± S.D (n ≥ 4 mice). (C) Representative 3D images showing volumetric distribution of ZsGreen1 transgene expression (green) in healthy mouse striatum 48 hours after the local infusion via CED of rPEI/pDNA (left), PEG/rPEI/pDNA (middle), or PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs stored for 2 weeks at room temperature (right). Scale bar = 500 μm. (D) Volume of ZsGreen1 transgene expression in mouse striatum. (E) Luciferase activity in the mouse striatum treated with rPEI/pDNA, PEG/bPEI/pDNA, or PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs. Data represent mean ± S.D. (n ≥ 4 mice), **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 (Student’s t-test or One-way ANOVA).

We next tested whether the increase in the volumetric distribution of PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs led to more widespread reporter transgene expression in mouse striatum. Animals were identically treated with NPs carrying ZsGreen1-expressing pDNA to determine the volumetric distribution of transgene expression at 48-hour post-administration. Similar to the particle distribution pattern, PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs exhibited markedly greater volume of ZsGreen1 transgene expression compared to rPEI/pDNA (Figure 3C). Our quantitative analysis revealed the volume of ZsGreen1 transgene expression mediated by rPEI/pDNA and PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs to be 3.6 ± 0.6 mm3 and 9.2 ± 2.1 mm3, respectively (Figure 3D). As expected from the unperturbed particle characteristics (Table S1), a 2-weeks incubation at room temperature did not compromise the ability of PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs to mediate widespread striatal transgene expression (Figure 3C and 3D). Remarkably, the volume of transgene expression mediated by PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs was over 70% of the volumetric NP distribution in mouse striatum (Figure 3B and 3D). The relative coverage of transgene expression shown here was markedly greater than our previous observations with brain-permeable gene delivery NPs formulated with bPEI (i.e., PEG/bPEI/pDNA NPs) or biodegradable poly(β-amino ester) that exhibited the fractional coverages spanning 30 – 45%.1, 19 Noting that all these NPs possess excellent brain-permeating properties, the ability of PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs to facilitate intracellular payload release and thus to enhance transgene expression may have yielded greater fractional coverage of transgene expression in mouse striatum.

To investigate whether more widespread transgene expression yielded greater overall level of transgene expression, we repeated the in vivo gene transfer study with NPs carrying luciferase-expressing pDNA. We found that the ability of PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs to provide enhanced volumetric transgene expression resulted in more than two orders of magnitude greater luciferase activity compared to rPEI/pDNA NPs in mouse striatum (Figure 3E). In agreement with our in vitro observation (Figure 2), PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs showed ~3.6-fold greater luciferase activity compared to PEG/bPEI/pDNA NPs (Figure 3E). Given that particle properties were virtually identical (Table S1), the superiority was attributed to the bioreducible property of PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs. Importantly, we confirmed the safety of intracranially administered PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs with a blinded histopathological evaluation of the brain slices conducted by a board-certified neuropathologist (C.G.E.) in a blinded manner. Specifically, histological scorings of hemorrhage, inflammation, and calcification in saline- and PEG/rPEI/pDNA NP-treated brains were comparable without statistical significant differences (Figure S4).

Given the robust striatal transgene expression mediated by PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs, we expanded our study to evaluate the ability of PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs to transfect neuron-rich brain regions relevant to the onset of neurodegenerative disorders. We first compared the volumetric distribution of transgene expression mediated by intracranial CED of PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs or AAV2, as a clinical control, in hippocampus (HC), the therapeutic target site for Alzheimer’s disease (AD).20, 21 Remarkably, PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs provided at least comparable volume of reporter transgene expression at 48-hour post-administration compared to AAV2 at 2-week post-administration, with a greater average volumetric distribution (Figure 4). The times of assessments were determined based on the well-established gene expression kinetics of pDNA controlled by the cytomegalovirus promoter (packaged in NPs) and AAV2.22, 23 We also confirmed that intracranial CED of PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs in substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpC), the therapeutic target site for Parkinson’s disease (PD) where dopaminergic neurons reside,24 resulted in widespread transgene expression at 48-hour post-administration (Figure S5). Of note, AAV2 is one of the leading viral vectors widely explored for neurological applications due to its safety, neuronal tropism, and long-lasting gene expression.25–27 A recently reported AD gene therapy clinical study that tested AAV2 revealed tolerability and long-term transgene expression, but the vector spread was limited presumably due to the use of stereotactic injection rather than CED, and inaccurate injection was observed.28 On the other hand, PD patients received magnetic resonance image (MRI)-guided CED of AAV2 carrying a gene encoding a neurotrophic factor exhibited long-term safety and improved and targeted therapeutic coverage.29 Likewise, MRI-guided CED of AAV2 carrying a gene encoding aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) achieved target coverage of 98% of SNpc with meaningful therapeutic outcomes among patients with AADC deficiency.30 Accordingly, there is an ongoing AD gene therapy exploring MRI-guided intracranial CED of AAV2 carrying a gene encoding a neurotrophic factor (NCT05040217).

Figure 4. PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs provide at least comparable distribution of reporter transgene expression compared to AAV2 in healthy mouse hippocampus (HC) following CED.

Expression cassette or pDNA encoding ZsGreen1 is packaged in AAV2 or PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs, respectively. (A) Representative 3D images showing volumetric distribution of ZsGreen1 transgene expression (green) in mouse HC 2 weeks or 48 hours after the local infusion via CED of AAV2 (left) or PEG/rPEI/pDNA NPs (right), respectively. Scale bar = 500 μm. (B) Volume of ZsGreen1 transgene expression in mouse HC. Data represent mean ± S.D. (n = 3 and 4 mice for AAV2 and PEG/rPEI/pDNA groups, respectively).

In conclusion, we newly engineered bioreducible polymer-based non-viral gene delivery platform capable of mediating widespread transgene expression in multiple therapeutically relevant brain regions following intracranial CED. We confirmed that our bioreducible gene delivery NPs provided enhanced gene delivery efficacy in vitro and in vivo compared to non-biodegradable NPs due to the ability to facilitate intracellular release of pDNA payloads. Remarkably, our platform exhibited the ability to transfect neuron-rich brain regions on par with one of the leading viral vectors being tested in previous and ongoing clinical trials, if not better, with excellent safety profile and potential of long-term storage. To this end, our platform may constitute an attractive alternative to viral vectors for intracranial gene therapy if the optimized clinical practice (i.e., MRI-guided CED) applied to viral vectors is employed.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The work was supported by the National Institute of Health (R01NS111102, R01NS119609, and P30EY01765).

Footnotes

Supporting Information.

Supporting Information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org. Supporting Information includes Materials and Methods and Supplementary Figures and Table.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mastorakos P; Zhang C; Berry S; Oh Y; Lee S; Eberhart CG; Woodworth GF; Suk JS; Hanes J, Highly PEGylated DNA Nanoparticles Provide Uniform and Widespread Gene Transfer in the Brain. Adv Healthc Mater 2015, 4 (7), 1023–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Negron K; Khalasawi N; Lu B; Ho CY; Lee J; Shenoy S; Mao HQ; Wang TH; Hanes J; Suk JS, Widespread gene transfer to malignant gliomas with In vitro-to-In vivo correlation. J Control Release 2019, 303, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolak DJ; Thorne RG, Diffusion of macromolecules in the brain: implications for drug delivery. Mol Pharm 2013, 10 (5), 1492–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mastorakos P; Zhang C; Song E; Kim YE; Park HW; Berry S; Choi WK; Hanes J; Suk JS, Biodegradable brain-penetrating DNA nanocomplexes and their use to treat malignant brain tumors. J Control Release 2017, 262, 37–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jahangiri A; Chin AT; Flanigan PM; Chen R; Bankiewicz K; Aghi MK, Convection-enhanced delivery in glioblastoma: a review of preclinical and clinical studies. J Neurosurg 2017, 126 (1), 191–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaczmarek JC; Kowalski PS; Anderson DG, Advances in the delivery of RNA therapeutics: from concept to clinical reality. Genome Med 2017, 9 (1), 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meleshko AN; Petrovskaya NA; Savelyeva N; Vashkevich KP; Doronina SN; Sachivko NV, Phase I clinical trial of idiotypic DNA vaccine administered as a complex with polyethylenimine to patients with B-cell lymphoma. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2017, 13 (6), 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahapatro A; Singh DK, Biodegradable nanoparticles are excellent vehicle for site directed in-vivo delivery of drugs and vaccines. J Nanobiotechnology 2011, 9, 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Makadia HK; Siegel SJ, Poly Lactic-co-Glycolic Acid (PLGA) as Biodegradable Controlled Drug Delivery Carrier. Polymers (Basel) 2011, 3 (3), 1377–1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee YS; Kim SW, Bioreducible polymers for therapeutic gene delivery. J Control Release 2014, 190, 424–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim TI; Kim SW, Bioreducible polymers for gene delivery. React Funct Polym 2011, 71 (3), 344–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kozielski KL; Tzeng SY; De Mendoza BA; Green JJ, Bioreducible cationic polymer-based nanoparticles for efficient and environmentally triggered cytoplasmic siRNA delivery to primary human brain cancer cells. ACS Nano 2014, 8 (4), 3232–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu Z; Wang Q; Zhong H; Jiang Y; Shi X; Yuan B; Yu N; Zhang S; Yuan X; Guo S; Yang Y, Carrier strategies boost the application of CRISPR/Cas system in gene therapy. Exploration (Beijing) 2022, 2 (2), 20210081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nam K; Jung S; Nam JP; Kim SW, Poly(ethylenimine) conjugated bioreducible dendrimer for efficient gene delivery. J Control Release 2015, 220 (Pt A), 447–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nam JP; Kim S; Kim SW, Design of PEI-conjugated bio-reducible polymer for efficient gene delivery. Int J Pharm 2018, 545 (1–2), 295–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kudo H; Mio T; Kokunai T; Tamaki N; Sumino K; Matsumoto S, Quantitative analysis of glutathione in human brain tumors. J Neurosurg 1990, 72 (4), 610–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salazar-Ramiro A; Ramirez-Ortega D; Perez de la Cruz V; Hernandez-Pedro NY; Gonzalez-Esquivel DF; Sotelo J; Pineda B, Role of Redox Status in Development of Glioblastoma. Front Immunol 2016, 7, 156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nance EA; Woodworth GF; Sailor KA; Shih TY; Xu Q; Swaminathan G; Xiang D; Eberhart C; Hanes J, A dense poly(ethylene glycol) coating improves penetration of large polymeric nanoparticles within brain tissue. Sci Transl Med 2012, 4 (149), 149ra119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Negron K; Zhu C; Chen SW; Shahab S; Rao D; Raabe EH; Eberhart CG; Hanes J; Suk JS, Non-adhesive and highly stable biodegradable nanoparticles that provide widespread and safe transgene expression in orthotopic brain tumors. Drug Deliv Transl Res 2020, 10 (3), 572–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anand KS; Dhikav V, Hippocampus in health and disease: An overview. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2012, 15 (4), 239–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Setti SE; Hunsberger HC; Reed MN, Alterations in Hippocampal Activity and Alzheimer’s Disease. Transl Issues Psychol Sci 2017, 3 (4), 348–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boshart M; Weber F; Jahn G; Dorsch-Hasler K; Fleckenstein B; Schaffner W, A very strong enhancer is located upstream of an immediate early gene of human cytomegalovirus. Cell 1985, 41 (2), 521–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aschauer DF; Kreuz S; Rumpel S, Analysis of transduction efficiency, tropism and axonal transport of AAV serotypes 1, 2, 5, 6, 8 and 9 in the mouse brain. PLoS One 2013, 8 (9), e76310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sonne J; Reddy V; Beato MR, Neuroanatomy, Substantia Nigra. In StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL), 2023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hadaczek P; Eberling JL; Pivirotto P; Bringas J; Forsayeth J; Bankiewicz KS, Eight years of clinical improvement in MPTP-lesioned primates after gene therapy with AAV2-hAADC. Mol Ther 2010, 18 (8), 1458–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bartlett JS; Samulski RJ; McCown TJ, Selective and rapid uptake of adeno-associated virus type 2 in brain. Hum Gene Ther 1998, 9 (8), 1181–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Royo NC; Vandenberghe LH; Ma JY; Hauspurg A; Yu L; Maronski M; Johnston J; Dichter MA; Wilson JM; Watson DJ, Specific AAV serotypes stably transduce primary hippocampal and cortical cultures with high efficiency and low toxicity. Brain Res 2008, 1190, 15–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Castle MJ; Baltanas FC; Kovacs I; Nagahara AH; Barba D; Tuszynski MH, Postmortem Analysis in a Clinical Trial of AAV2-NGF Gene Therapy for Alzheimer’s Disease Identifies a Need for Improved Vector Delivery. Hum Gene Ther 2020, 31 (7–8), 415–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rocco MT; Akhter AS; Ehrlich DJ; Scott GC; Lungu C; Munjal V; Aquino A; Lonser RR; Fiandaca MS; Hallett M; Heiss JD; Bankiewicz KS, Long-term safety of MRI-guided administration of AAV2-GDNF and gadoteridol in the putamen of individuals with Parkinson’s disease. Mol Ther 2022, 30 (12), 3632–3638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pearson TS; Gupta N; San Sebastian W; Imamura-Ching J; Viehoever A; Grijalvo-Perez A; Fay AJ; Seth N; Lundy SM; Seo Y; Pampaloni M; Hyland K; Smith E; de Oliveira Barbosa G; Heathcock JC; Minnema A; Lonser R; Elder JB; Leonard J; Larson P; Bankiewicz KS, Gene therapy for aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency by MR-guided direct delivery of AAV2-AADC to midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Nat Commun 2021, 12 (1), 4251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.