Abstract

The RPI1 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae was identified initially as a dosage suppressor of the heat shock sensitivity associated with overexpression of RAS2 (J. Kim and S. Powers, Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:3894–3904, 1991). Based on its failure to suppress mutationally activated RAS2, RPI1 was proposed to be a negative regulator of the Ras/cyclic AMP (cAMP) pathway that functions at a point upstream of Ras. We isolated RPI1 as a high-copy-number suppressor of the cell lysis defect associated with a null mutation in the MPK1 gene, which encodes the mitogen-activated protein kinase of the cell wall integrity-signaling pathway. Although the sequence of Rpi1 is not informative about its function, we present evidence that this protein resides in the nucleus, possesses a transcriptional activation domain, and affects the mRNA levels of several cell wall metabolism genes. In contrast to the previous report, we found that RPI1 overexpression suppresses defects associated with mutational hyperactivation of the Ras/cAMP pathway at all points including constitutive mutations in the cAMP-dependent protein kinase. We present additional genetic and biochemical evidence that Rpi1 functions independently of and in opposition to the Ras/cAMP pathway to promote preparations for the stationary phase. Among these preparations is a fortification of the cell wall that is antagonized by Ras pathway activity. This observation reveals a novel link between the Ras/cAMP pathway and cell wall integrity. Finally, we propose that inappropriate expression of RPI1 during log phase growth drives fortification of the cell wall and that this behavior is responsible for suppression of the mpk1 cell lysis defect.

The cell wall of the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is required to maintain cell shape and integrity (4, 24). The cell must remodel this rigid structure during vegetative growth and during pheromone-induced morphogenesis. Wall remodeling is monitored and regulated by the cell wall integrity-signaling pathway controlled by the Rho1 GTPase. Two essential functions have been identified for Rho1. First, it serves as an integral regulatory subunit of the 1,3-β-glucan synthase complex (GS) that stimulates GS activity in a GTP-dependent manner (9, 41). A pair of closely related genes, FKS1 and FKS2, encode alternative catalytic subunits of the GS complex (8, 14, 34, 42) that are the presumed targets of Rho1 activity.

A second essential function of Rho1 is to bind and activate protein kinase C (20, 35), which is encoded by PKC1 (31, 53). Loss of PKC1 function, or of any of the components of the mitogen-activated protein MAP kinase cascade under its control (30), results in a cell lysis defect that is attributable to a deficiency in cell wall construction (28, 29, 40). The MAP kinase cascade is a linear pathway (see reference 13 for a review) composed of a MEKK (BCK1 [5, 26]), a pair of redundant MEKs (MKK1/2 [15]) and a MAP kinase (MPK1 [25]). One of the consequences of signaling through the MAP kinase cascade is the activation of the serum response factor-like transcription factor, Rlm1 (7, 54). Signaling through Rlm1 regulates the expression of at least 25 genes, most of which have been implicated in cell wall biogenesis (18).

Several regulators of Rho1 activity have been identified recently. Rom1 and Rom2 comprise a redundant pair of guanine nucleotide exchange factors for Rho1 (33, 37). Additionally, Bem2 and Sac7 are GTPase-activating proteins for Rho1 (23, 38, 46). Two major cell surface sensors for the activation of cell integrity signaling have also been described. One of these, known variously as Wsc1 (32, 52), Hcs77 (11), and Slg1 (17), is dedicated to signaling wall stress during vegetative growth (43). The primary function of the other, called Mid2 (36), is to signal wall stress that results from pheromone-induced morphogenesis (43). Null mutations in WSC1 and MID2, in combination, result in a severe cell lysis defect, indicating that the functions of these genes are partially overlapping. We have shown by two-hybrid analyses that both Wsc1 and Mid2 interact with the Rom2 guanine nucleotide exchange factor and that this interaction stimulates guanine nucleotide exchange on Rho1 (39).

Cell wall integrity signaling is induced in response to several environmental stimuli. First, signaling is activated persistently in response to growth at elevated temperatures (e.g., 37 to 39°C) (19), consistent with the finding that null mutants in many of the pathway components display cell lysis defects only when cultivated at high temperature. Second, hypo-osmotic shock induces a rapid but transient activation of signaling (6, 19). Third, treatment with mating pheromone stimulates signaling at a time that is coincident with the onset of morphogenesis (2, 10). Indeed, mutants defective in cell integrity signaling undergo cell lysis during pheromone-induced morphogenesis (10). In addition to these natural environmental stimuli, chemical agents that cause cell wall stress, such as the chitin antagonist Calcofluor white, activate signaling (21).

The Ras/cyclic AMP (cAMP) pathway of yeast plays a major role in the control of cell proliferation in response to nutrient conditions (1, 49). Mutants that are deficient in cAMP production (eg. ras1/2, cdc25, and cdc35) are unable to activate the cAMP-dependent protein kinases (Tpk1, -2, and -3). As a result, such mutants arrest growth in a state that mimics stationary phase, a condition normally signaled by depletion of nutrient supplies. This state is analogous to the G0 phase described for mammalian cells. By contrast, mutants that result in constitutive cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) activity fail to respond appropriately to nutrient limitation. This causes a general failure to prepare for stationary phase (1, 49). Phenotypic consequences associated with constitutive Ras/cAMP pathway activity include (but are not limited to) the failure to produce storage carbohydrates and the failure to acquire thermotolerance as cells exhaust nutrient supplies. These and other metabolic failures result in a reduced ability of constitutive Ras/cAMP pathway mutants to survive long-term stasis.

The RPI1 gene (for “Ras pathway inhibitor 1”) was isolated initially by Kim and Powers (22) as a high-copy-number suppressor of the heat shock sensitivity resulting from overexpression of wild-type RAS2. Because these investigators failed to detect suppression of mutationally activated RAS2, they concluded that Rpi1 functions as an upstream regulator of Ras activity. Here we describe the isolation of RPI1 as a high-copy-number suppressor of the cell lysis defect associated with loss of function of the Mpk1 MAP kinase. We present evidence that RPI1 encodes a novel transcriptional activator that functions independently of both the Ras/cAMP pathway and the cell wall integrity signaling pathway in the preparation of cells for stationary phase. We show that RPI1 overexpression increases the mRNA levels of a subset of genes involved in cell wall metabolism. Additionally, we demonstrate that constitutive Ras/cAMP pathway activity inhibits the cell wall fortification normally associated with preparation for stationary phase. This finding provides a novel connection between the Ras/cAMP pathway and cell wall integrity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, growth conditions, and transformations.

The S. cerevisiae strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Yeast cultures were grown in YEPD (1% Bacto Yeast Extract, 2% Bacto Peptone, 2% glucose). Synthetic minimal (SD) medium (44) supplemented with the appropriate nutrients was used to select for plasmid maintenance and gene replacement. Yeast transformations were carried out by the lithium acetate method (16). Escherichia coli DH5α was used to propagate all plasmids. E. coli cells were cultured in Luria broth medium (1% Bacto Tryptone, 0.5% Bacto Yeast Extract, 1% NaCl) and transformed by standard methods.

TABLE 1.

S. cerevisiae strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| 1783 | MATaa | I Herskowitz |

| 1784 | MATαa | I. Herskowitz |

| 1788 | MATa/αa | I. Herskowitz |

| DL453 | MATa/αampk1Δ::TRP1/MPK1 | 25 |

| DL456 | MATa/αampk1Δ::TRP1/mpk1Δ::TRP1 | 25 |

| DL2286 | MATa/αampk1Δ::TRP1/MPK1 rpi1Δ::LEU2/RPI1 | This study |

| DL2287 | MATaampk1Δ::TRP1 rpi1Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| DL2289 | MATaarpi1Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| DL2291 | MATa/αampk1Δ::TRP1/mpk1Δ::TRP1 rpi1Δ::LEU2/rpi1Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| DL2297 | MATaaira1Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| DL2299 | MATa/αaira1Δ::LEU2/ira1Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| DL2329 | MATaarpi1Δ::LEU2 ira1Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| DL2153 | MATαbRAS2A18V19 | K. Tatchell |

| DL2154 | MATabRAS2 | K. Tatchell |

| DL2204 | MATαbras1-545::URA3 ras2-530::LEU2 SRA4-6 | J. Cannon |

| DL2226 | MATαcras1-545::URA3 ras2-530::LEU2 SRA4-6 trp1-1 | This study |

| DL2156 | MATadbcy1Δ::HIS3 | K. Tatchell |

| DL2599 | MATae AH109 | Clontech Laboratories |

| DL707 | MATafrpi1Δ::URA3 | 22 |

EG123 background: leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-52 his4 can1.

LRA27 background: leu2 ura3-52 his4-539.

mixed-strain background resulting from cross between DL2204 and 1784 to introduce trp1-1.

KT1037 background: MATa leu2 ura3-52 his3

MATa trp1-901 leu203,112 ura3-52 his3-200 gal4Δ gal80Δ LYS2::GAL1UAS-GAL1TATA-HIS3 GAL2UAS-GAL2TATA-ADE2 URA3::MEL1UAS-MEL1TATA-lacZ.

Sp1 background: leu2 ura3 his3 trp1 ade8 can1 gal2 (JHY105).

Assays for heat shock and Zymolyase sensitivity.

Yeast cultures, grown for 24 h in SD medium, were diluted 1:10 into YEPD preheated to the specified temperature to subject them to heat shock. The cultures were shaken at the elevated temperature for the duration of the heat shock. They were then diluted and plated on YEPD to assess survival. Zymolyase sensitivity was tested as described previously (7), except that Zymolyase 20T was used.

Genomic deletions of RPI1 and IRA1.

To delete the genomic copy of RPI1, 1.1 kb of sequence upstream of the start codon and 801 bp downstream of the stop codon were amplified in separate PCRs from genomic DNA of strain 1783. The upstream fragment was amplified with primers that would create an XbaI site at the end adjacent to the RPI1 coding sequence and an SphI site at the other end. The downstream fragment was amplified with primers that would create a HindIII site at the end adjacent to the RPI1 coding sequence and an SphI site at the other end. These fragments were ligated in a three-molecule reaction into the XbaI and HindIII sites of the integrative plasmid, pRS305 (47), to create a unique SphI site between the fragments. The resulting plasmid, pRS305[rpi1Δ::LEU2], was linearized with SphI and used to transform DL453 to leucine prototrophy.

To delete the genomic copy of IRA1, 622 bp of upstream sequence plus 306 bp of the IRA1 coding sequence were amplified by PCR from genomic DNA of strain 1783. In a separate PCR, 960 bp downstream of the IRA1 stop codon was amplified. The upstream fragment was amplified with primers that would create a HindIII site at the end adjacent to the IRA1 coding sequence and an XhoI site at the other end. The downstream fragment was amplified with primers that would create a HindIII site at the end adjacent to the IRA1 coding sequence and an XbaI site at the other end. These fragments were ligated in a three-molecule reaction into the XbaI and XhoI sites of pRS305 to create a unique HindIII site between the fragments. The resulting plasmid, pRS305[ira1Δ::LEU2], was linearized with HindIII and used to transform strain DL453 to leucine prototrophy. Deletion mutants were confirmed by PCR.

Fluorescence microscopy of Rpi1-GFP.

Rpi1 was tagged at its C terminus with a UV-optimized variant of green fluorescent protein (GFP), GFPuv (Clontech). A 1.4-kb fragment including RPI1 with 204 bp of 5′ noncoding sequence (amplified from YEp352[RPI1]), but without its stop codon, was blunt-end inserted into the SmaI site of pRS315[GFPuv] (43). This construct (pRPI1-GFP) expressed GFPuv fused to the C terminus of Rpi1 with an additional glycyl residue at the fusion point. The fusion was subcloned into the 2μm vector pRS425 (47), using polylinker sites PstI and NotI, for higher-level expression. Diploid strain 1788, expressing RPI1-GFP from pRS425, was grown overnight in SD medium lacking leucine, subcultured in YPD medium, and allowed to grow to log phase. Preparation of slides and microscopy of live cells were performed as described previously (43) except for the substitution of 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for Hoescht.

Transcriptional activation assays and analysis of mRNA levels.

Fusions of Rpi1 to the C terminus of the Gal4 DNA binding domain (DBD) were constructed in vector pGBT9 (Clontech) by ligation of PCR-generated fragments from BamHI to PstI in the polylinker of this vector. These plasmids were transformed into two-hybrid strain AH109 (Clontech) and tested for the ability to activate transcription of the ADE2 reporter gene under the control of the GAL2 promoter. For measurements of mRNA levels, whole-cell RNA was isolated from yeast strains grown to mid-log phase and analyses of mRNA levels were conducted as described previously (18).

RESULTS

RPI1 is a dosage-dependent suppressor of the mpk1Δ cell lysis defect.

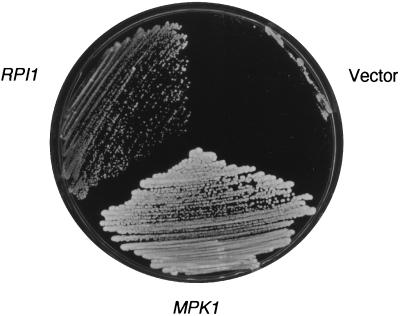

We reported previously the isolation of eight 2μm-based suppressors of the cell lysis defect associated with loss of MPK1 function (27). One of these plasmids was determined by DNA sequence analysis to contain RPI1 (YIL119c), QDR1 (YIL 120w), and two hypothetical open reading frames (YIL121w and YIL122w). Deletion analysis of this plasmid revealed that RPI1 was responsible for suppression of the mpk1Δ defect (Fig. 1 and data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Overexpression of RPI1 suppresses the growth defect of an mpk1 mutant. Transformants of yeast strain DL456 (mpk1Δ) harboring episomal vector YEp352 (12), YEp352[RPI1], or centromeric plasmid YCp50[MPK1] were streaked onto a YPD plate and incubated at 37°C for 3 days.

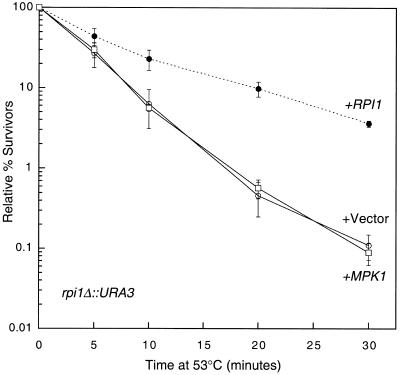

The RPI1 gene was isolated initially by Kim and Powers (22) as a dosage-dependent suppressor of the heat shock sensitivity associated with overexpression of RAS2, suggesting a role for this gene in acquired thermotolerance. Our isolation of RPI1 as a dosage suppressor of mpk1Δ suggested that it also plays a role in the maintenance of cell wall integrity. RPI1 encodes a putative 406-amino-acid protein, whose sequence is uninformative as to its function. Although loss of RPI1 function does not result in a detectable growth defect, an rpi1Δ mutant displays sensitivity to heat shock (22). Therefore, we tested for reciprocal suppression of this rpi1Δ phenotype by overexpression of MPK1. Figure 2 shows that a 2μm plasmid bearing MPK1 failed to suppress the heat shock sensitivity of rpi1Δ, suggesting that if these genes function within the same pathway, MPK1 does not function downstream of RPI1.

FIG. 2.

Overexpression of MPK1 fails to suppress the heat shock sensitivity of an rpi1 mutant. Transformants of yeast strain DL707 (rpi1Δ) harboring episomal vector YEp352, YEp352[MPK1], or centromeric plasmid pRS316[RPI1] were grown to saturation in SD medium and subjected to heat shock for the indicated times. Cultures were diluted and plated on YPD to determine survival levels. Each value represents the mean and standard deviation from at least three independent experiments.

Rpi1 is a putative novel transcriptional regulator.

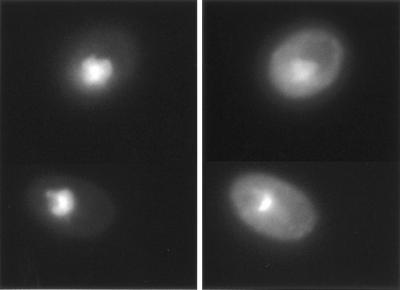

To begin to address the function of Rpi1, we examined its intracellular localization. Rpi1 was tagged at its C terminus with GFP. When expressed from a 2μm-based plasmid (pRS425[RPI1-GFP]), this fusion protein suppressed the growth defect of mpk1Δ as efficiently as Rpi1 (data not shown), indicating that it is biologically functional. Expression of the Rpi1-GFP fusion from a centromeric plasmid could not be detected by fluorescence microscopy. However, fluorescence was detected in cells harboring pRS425[RPI1-GFP], revealing that the fusion protein is localized to the nucleus (Fig. 3). By contrast, GFP expressed alone is distributed uniformly throughout the cell (52).

FIG. 3.

Rpi1 resides in the nucleus. Fluorescence micrographs of wild-type strain 1788 expressing Rpi1-GFP from episomal plasmid pRS425[RPI1-GFP] are shown. Rpi1-GFP was visualized using fluorescein isothiocyanate filter (left). Rpi1-GFP colocalized with nuclear DNA, as judged by DAPI fluorescence (right).

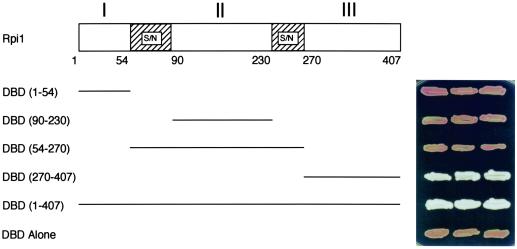

Localization of Rpi1 to the nucleus suggested the possibility that this protein is involved in transcriptional regulation. To test for the presence of a transcriptional activation domain within Rpi1, we created an N-terminal fusion of the entire RPI1 open reading frame to the DBD of the Gal4 transcription factor (DBD-Rpi1). Expression of DBD-Rpi1 activated transcription from an ADE2 reporter plasmid under the control of the GAL1 promoter (Fig. 4), indicating that Rpi1 has the capability to activate transcription. To identify the region of Rpi1 responsible for transcriptional activation, we constructed four additional Rpi1 fusions to the DBD of Gal4. Rpi1 possesses two regions that are very rich in seryl and asparagyl residues (36 to 40 amino acids; 75 to 83% Ser/Asn), which were used as guidelines for separation of the protein into three domains (Fig. 4). Only the C-terminal domain, which includes residues 270 to 407, was capable of transcriptional activation when fused to the Gal4 DBD.

FIG. 4.

The C-terminal domain of Rpi1 possesses a transcriptional activation function. Yeast strain AH109 (GAL2UAS-GAL2TATA-ADE2) was transformed with plasmids bearing fusions of RPI1 to the Gal4 DBD in the two-hybrid vector pGBT9. Transformants were patched onto YPD medium for 3 days. Failure to develop a red color is due to GAL2-driven expression of the ADE2 reporter and indicates transcriptional activation by the protein fused to the Gal4 DBD.

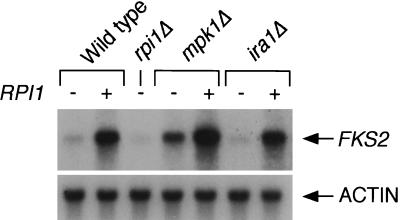

Because RPI1 overexpression suppressed the cell wall integrity defect of an mpk1Δ mutant and because RPI1 has the potential to activate transcription, we asked if its overexpression alters the mRNA levels of several genes regulated by cell wall integrity signaling. FKS2 encodes a catalytic subunit of the 1,3-β-glucan synthase complex, which is responsible for synthesis of the major structural polymer of the cell wall (14, 34, 42). Cell wall stress-induced expression of FKS2 is partly under the control of cell wall integrity signaling (57). Figure 5 shows that the FKS2 mRNA level is strikingly elevated during log-phase growth in response to RPI1 overexpression. In contrast, FKS2 mRNA was slightly diminished in an rpi1Δ mutant. As noted previously (57), FKS2 mRNA was somewhat elevated in an mpk1Δ mutant (Fig. 5). However, overexpression of RPI1 in this mutant induced a further increase in the FKS2 mRNA level, indicating that regulation of FKS2 mRNA levels by RPI1 is independent of cell wall integrity signaling. These effects were recapitulated using a lacZ reporter under the control of the FKS2 promoter (nucleotides −706 to 1 [57]), in which a six- to eightfold increase in expression was observed in response to RPI1 overexpression (data not shown). This result indicates that RPI1 overexpression exerts its effect on the FKS2 mRNA level by stimulating the transcription of this gene.

FIG. 5.

Overexpression of RPI1 enhances FKS2 mRNA levels independently of the states of the cell wall integrity and Ras/cAMP signaling pathways. Plus signs indicate overexpression of RPI1 from YEp352. Total RNA (10 μg), isolated from log-phase cultures, was probed for FKS2 mRNA. A probe for ACT1 (encoding actin) was used as a negative control.

Several additional genes known to be regulated by cell wall integrity signaling (18) followed the same pattern as FKS2, although none with as large an effect (data not shown). These included SED1 (encoding a major cell surface glycoprotein), BGL2 (encoding a cell wall glucanosyltransferase), and MLP1 (encoding a homolog of Mpk1). The mRNA levels of several additional candidate genes were unaffected by RPI1 overexpression. These included FKS1, YIL117, and CIS3 (data not shown). Thus, Rpi1 overexpression increased the mRNA levels of a subset of genes involved in cell wall metabolism in a manner that was independent of Mpk1.

RPI1 functions independently of the Ras/cAMP pathway.

Kim and Powers (22) reported that RPI1 is a negative regulator of the Ras/cAMP pathway that functions at a point upstream of Ras. They presented two lines of evidence to support this assertion. First, overexpression of wild-type RAS2 prevents cells from acquiring thermotolerance as they approach stationary phase. This defect was suppressed by overexpression of RPI1. By contrast, RPI1 overexpression failed to suppress the defect in acquired thermotolerance associated with mutationally activated RAS2. Second, overexpression of RPI1 caused a modest decrease in the cAMP levels of wild-type cells, which was interpreted to mean that RPI1 regulates the production of this second messenger through Ras. Because Ras localizes to the plasma membrane (56), our dual findings that Rpi1 localizes to the nucleus and can regulate transcription led us to reevaluate the previous findings on RPI1.

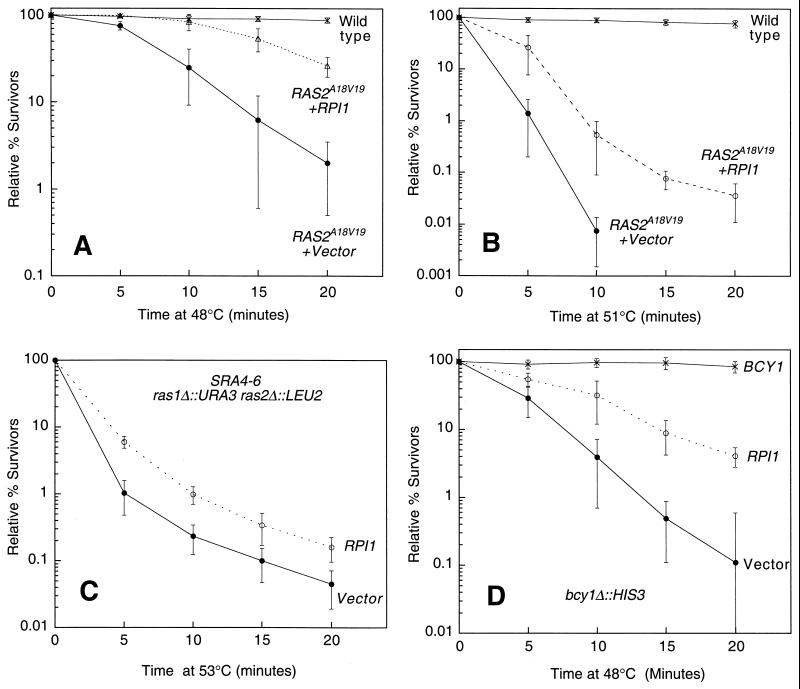

We took a quantitative approach to assessing the acquisition of thermotolerance. Rather than the binary test for growth of a patch of cells on a plate transiently exposed to high temperature used by Kim and Powers (22), we conducted heat shock experiments on liquid cultures grown to saturation (absorbance at 600 nm [A600] = 4.0) followed by measurements of viability. In contrast to the previous report, we found that overexpression of RPI1 could indeed suppress the heat shock sensitivity associated with mutationally activated Ras2 (Fig. 6A and B). Cultures of a RAS2A18V19 mutant were extremely sensitive to killing by a brief heat shock at either 48 or 51°C. In both cases, expression of RPI1 from a 2μm-based plasmid partially suppressed this defect, indicating that Rpi1 does not act upstream of Ras.

FIG. 6.

Overexpression of RPI1 suppresses the heat shock sensitivity associated with activating mutations in Ras, adenylate cyclase, and PKA. (A and B) Yeast strain DL2153 (RAS2Ala18Val19, which expresses constitutive Ras2), was transformed with either episomal vector YEp352 or YEp352[RPI1], and its congenic wild-type (DL2154) was transformed with vector only. Transformants were grown to saturation in SD medium and subjected to heat shock at 48°C (A) or 51°C (B). Cultures were diluted and plated on YPD to determine survival levels. (C) Yeast strain DL2226 (ras1Δ ras2Δ SRA4-6, which expresses constitutive adenylate cyclase) was transformed with either YEp352 or YEp352[RPI1] and tested for heat shock sensitivity as above. (D) Yeast strain DL2156 (bcy1Δ, which expresses constitutive PKA) was transformed with YEp352, YEp352[RPI1], or centromeric plasmid YCp50[BCY1] and tested for heat shock sensitivity as above. Each value represents the mean and standard deviation from at least three experiments.

To determine where in the Ras/cAMP pathway Rpi1 functions, we next examined a mutant with a constitutively active adenylate cyclase, the immediate target of Ras activity (51). The SRA4–6 mutation renders adenlyate cyclase activity independent of Ras function and thus suppresses the lethality associated with a double ras1Δ ras2Δ mutation (3). Constitutive cAMP production in a ras1Δ ras2Δ SRA4–6 mutant resulted in mild heat shock sensitivity, which was partially suppressed by overexpression of RPI1 (Fig. 6C). Therefore, Rpi1 does not function upstream of adenylate cyclase.

Finally, we examined a mutant with constitutively active PKA. PKA is the ultimate effector of cAMP signaling in yeast (51). Loss of function of its regulatory subunit, encoded by BCY1, results in constitutive PKA activity associated with extreme heat shock sensitivity (50). Figure 6D shows that overexpression of RPI1 partially suppressed the heat shock sensitivity of a bcy1Δ mutant, indicating that RPI1 does not act upstream of PKA.

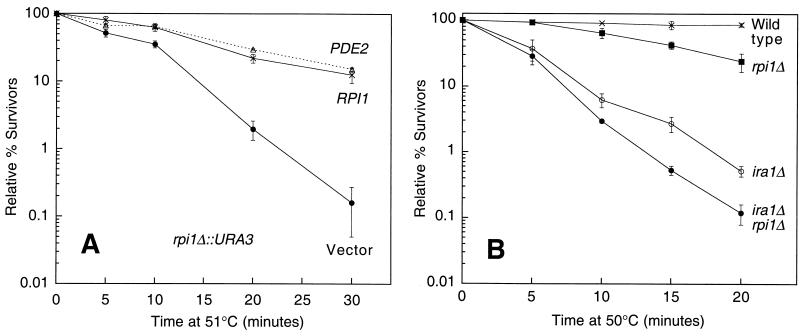

The above results suggested that prevention of acquired thermotolerance by constitutive PKA activity might occur through negative regulation of Rpi1 function. To determine if this is the case or, alternatively, if Rpi1 acts independently of the Ras/cAMP pathway to affect thermotolerance, we conducted three additional experiments. First, we asked if the heat shock sensitivity associated with rpi1Δ could be suppressed by downregulation of PKA. We investigated this by overexpression of the PDE2-encoded cAMP phosphodiesterase (45). Figure 7A shows that PDE2 expressed from a 2μm-based plasmid fully suppressed the heat shock sensitivity of an rpi1Δ mutant. This result suggests that the Ras/cAMP pathway acts independently of Rpi1 to promote acquired thermotolerance. Alternatively, if Rpi1 function is under the control of PKA, it is not the major mediator of acquired thermotolerance through this pathway.

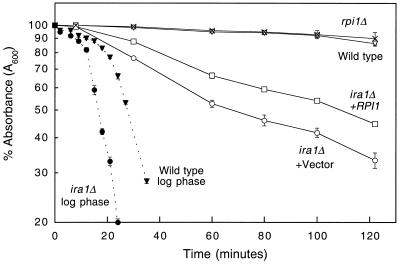

FIG. 7.

Rpi1 functions outside of the Ras/cAMP pathway. (A) Depression of cAMP levels by overexpression of PDE2 suppresses the heat shock sensitivity of an rpi1 mutant. Yeast strain DL707 (rpi1Δ) was transformed with YEp352, YEp352[PDE2], or centrometric plasmid pRS316[RPI1]. Transformants were grown to saturation in SD medium and subjected to heat shock for the indicated times. Cultures were diluted and plated on YPD to determine survival levels. (B) The heat shock sensitivities associated with rpi1 and ira1 are additive. Wild-type (1783), rpi1Δ (DL2289), ira1Δ (DL2297), and rpi1Δ ira1Δ (DL2329) strains were grown to saturation in YPD and tested for heat shock sensitivity as above. Each value represents the mean and standard deviation from at least three experiments.

Second, we asked if the heat shock sensitivity associated with hyperactivation of the Ras/cAMP pathway was additive with that of rpi1Δ. For this experiment, we used an ira1Δ mutant, which lacks one of two redundant Ras GAP proteins (48). The ira1Δ mutation results in heat shock sensitivity associated with hyperactive Ras. Figure 7B shows that the heat shock sensitivities of the ira1Δ and rpi1Δ mutants are additive in the ira1Δ rpi1Δ mutant, supporting the conclusion that Rpi1 contributes to acquired thermotolerance independently of the Ras/cAMP pathway.

Finally, we found that stimulation of FKS2 transcription by overexpression of RPI1 was not affected by loss of IRA1 (Fig. 5), further supporting the conclusion that RPI1 function is not downregulated by Ras/cAMP pathway activity.

Rpi1 functions in the preparation of cells for stationary phase.

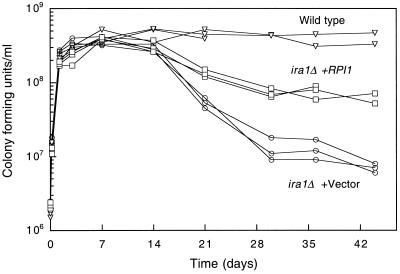

In addition to heat shock sensitivity, mutants that are hyperactivated for the Ras/cAMP pathway display several other phenotypic defects associated with their failure to respond to nutrient deprivation. These include diminished survival in stationary phase, failure to accumulate storage carbohydrates in preparation for stationary phase, and failure of diploids to sporulate on nitrogen starvation (1, 49). Therefore, to determine if RPI1 inhibits all aspects of the Ras/cAMP pathway output, we asked if RPI1 overexpression could suppress these additional defects. To assess survival in stationary phase, we cultivated cells in liquid YPD at 30°C for 6 weeks. Figure 8 shows that an ira1Δ mutant lost 2 log units of viability over the course of the experiment. Overexpression of RPI1 partially suppressed this viability loss, suggesting that Rpi1 serves a function in long-term survival of yeast cells in stasis.

FIG. 8.

Overexpression of RPI1 suppresses the inability of an ira1 mutant to survive in stationary phase. Yeast strain DL2297 (ira1Δ) was transformed with either episomal vector YEp352 or YEp352[RPI1]. Wild-type strain 1783 was transformed with YEp352 only. Transformants were inoculated into YPD medium, grown to saturation at 30°C with agitation, and maintained under the same conditions for 6 weeks. Samples were diluted and plated on YPD at the indicated times to test for viability. Experiments were conducted in triplicate. However, loss of two cultures during the course of the experiment prevented calculation of the standard deviation.

Next, we examined glycogen production qualitatively by iodine staining on YPD plates. An ira1Δ mutant, which does not accumulate glycogen, fails to stain brown by exposure to iodine vapors (1). Overexpression of RPI1 restored the ability of this strain to accumulate glycogen by this criterion (data not shown), further supporting the conclusion that Rpi1 plays a role in the preparation of cells for stationary phase.

To assess sporulation efficiency in response to nitrogen starvation, we incubated diploid cells on solid sporulation medium (44) for 6 days and then subjected them to microscopic examination of acsus formation. Wild-type diploids underwent sporulation under these conditions with an efficiency of 52%, whereas an ira1Δ mutant displayed <1% spore formation. No detectable suppression of this defect was observed when RPI1 was overexpressed, suggesting that RPI1 does not impinge on this process. Therefore, the function of RPI1 may be restricted to preparing cells for stationary phase.

An interesting but poorly understood aspect of the transition from log-phase to stationary-phase growth is a fortification of the cell wall structure, which can be detected by an acquired resistance to digestion by the cell wall-lytic enzyme, Zymolyase (55). Because cells with a hyperactive Ras/cAMP pathway are defective in many aspects of the transition to stationary phase, we asked if an ira1Δ mutant becomes resistant to Zymolyase as it approaches stationary phase. Cells were grown either to mid-log phase or to saturation and tested for senstivity to lysis by Zymolyase treatment. Figure 9 shows that an ira1Δ mutant was deficient in the acquired resistance to Zymolyase. This finding represents a novel phenotype associated with hyperactivation of the Ras/cAMP pathway. Although an rpi1Δ mutant was not deficient in acquired resistance to Zymolyase, overexpression of RPI1 partially suppressed the ira1Δ defect (Fig. 9). This result not only supports the conclusion that RPI1 assists cells in the preparation for stationary phase but also reveals a novel link between the Ras/cAMP pathway and cell wall integrity. Specifically, Ras pathway activity prevents fortification of the cell wall associated with entry into stationary phase.

FIG. 9.

Overexpression of RPI1 suppresses the deficiency of an ira1 mutant to acquire Zymolyase resistance in saturated cultures. Yeast strain DL2297 (ira1Δ) was transformed with either episomal vector YEp352 or YEp352[RPI1]. Strains 1783 (wild-type) and DL2289 (rpi1Δ) were transformed with YEp352 only. Transformants were grown to saturation in SD medium before being diluted into YPD. Cultures were grown either to mid-log phase (solid symbols) or to saturation (open symbols), washed, and resuspended in water to an initial density of A600 ≈ 0.55 prior to treatment with Zymolyase 20T (150 μg/ml). Cell lysis was assessed by A600 measurements at the indicated times.

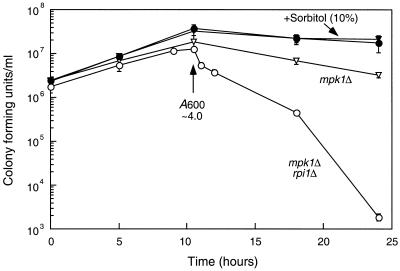

Because RPI1 overexpression may contribute to wall integrity as cells prepare for stationary phase, we examined the phenotypic effect of combining rpi1Δ with an mpk1Δ mutation. Mutants with null mutations in MPK1 undergo cell lysis when cultivated at 37°C (25). Although the rpi1Δ mutation did not exacerbate this growth defect by reducing the lethal plating temperature (data not shown), we observed that the mpk1Δ rpi1Δ double mutant suffered a severe loss of viability as cultures exited log phase (A600 ∼ 4.0 [Fig. 10]). Incubation of cultures for 14 h beyond the logarithmic growth phase resulted in a viability loss of 4 log units in the mpk1Δ rpi1Δ mutant, compared with viability loss of only 1 log unit in the mpk1Δ mutant. No viability loss was observed in the wild-type or rpi1Δ strains (data not shown). Microscopic examination of the aged mpk1Δ rpi1Δ culture revealed that these cells had lysed. Moreover, the viability loss observed in this mutant was completely suppressed by addition of 10% sorbitol to the medium for osmotic support (Fig. 10). These results further support the notion that Rpi1 serves a function in the maintenance of cell wall integrity, which appears to be restricted to preparation for the stationary phase.

FIG. 10.

An rpi1 mpk1 double mutant loses viability rapidly on exiting log-phase growth. Yeast strains DL456 (mpk1Δ) and DL2291 (mpk1Δ rpi1Δ) were cultured at 30°C in either SD medium (open symbols) or SD medium supplemented with 10% sorbitol (solid symbols), starting with identical inocula of log-phase cells. Samples were diluted and plated on YPD at the indicated times to test for viability. Culture densities were monitored during the course of the experiment to assess the growth phase. Isogenic wild-type and rpi1Δ strains did not display any loss of viability even after 48 h in culture (data not shown). Each value represents the mean and standard deviation from at least three experiments.

DISCUSSION

Rpi1 is a putative transcriptional regulator.

The RPI1 gene was identified initially as a negative regulator of the Ras/cAMP pathway (22). We isolated RPI1 in a screen for multicopy suppressors of the cell lysis defect that results from loss of function of the Mpk1 MAP kinase. The amino acid sequence of Rpi1 is not informative as to its function, and database searches have failed to detect homologs in other species. However, three lines of evidence implicate Rpi1 as a transcriptional regulator. First, we found that an Rpi1-GFP fusion protein localized to the nucleus. Second, fusions of Rpi1 to the DBD of GAL4 revealed that it possessed a transcriptional activation domain within its C-terminal 140 amino acids. Third, overexpression of RPI1 increased the level of mRNA of several genes involved in cell wall metabolism. In at least one case (i.e., FKS2), the increased mRNA level reflected increased transcriptional activity. Therefore, we propose that Rpi1 represents a novel class of transcriptional regulator. It remains to be determined if Rpi1 binds directly to DNA or mediates transcriptional regulation by associating with other regulators.

Rpi1 functions independently of the cell wall integrity MAP kinase cascade to promote cell wall biogenesis.

Although we isolated RPI1 as a dosage suppressor of the cell lysis defect of an mpk1Δ mutant, two lines of evidence suggest that Rpi1 functions independently of Mpk1 to promote cell wall integrity. First, overexpression of RPI1 increased the level of mRNA of several genes involved in cell wall metabolism independently of Mpk1 function. Second, an rpi1Δ mpk1Δ mutant displayed a much more severe defect in viability than did either single mutant as cells exited from log-phase growth. If Rpi1 function were strictly under the control of Mpk1, no defect additivity would be observed by combining null alleles in both genes. Moreover, although immunoblot analyses of Rpi1 revealed multiple forms, suggesting that this protein is modified, we have not observed changes in the band patterns in response to a loss of Mpk1 function (A. Sobering, unpublished results).

Previously, we reported two other genes (PPZ2, and BCK2) that were identified in the screen that yielded RPI1 (27). Like RPI1, PPZ2 and BCK2 were both proposed, based on the behavior of mutants with mutations in these genes, to function independently of Mpk1. The roles of PPZ2 and BCK2 in promoting cell wall integrity remain unknown. We hypothesize that overproduction of RPI1 suppresses the loss of cell wall integrity signaling by altering the transcriptional regulation of a subset of genes involved in cell wall biogenesis.

Rpi1 functions in opposition to the Ras/cAMP pathway to promote preparation for the stationary phase.

RPI1 was reported initially to function upstream of RAS in the Ras/cAMP pathway (22). However, four lines of evidence indicate that RPI1 functions independently of the Ras/cAMP pathway to oppose the output of PKA. First, overexpression of RPI1 suppressed the failure of mutants with constitutive mutations in RAS2, SRA4/CDC35 (encoding adenylate cyclase), and BCY1 (encoding the regulatory subunit of PKA) to acquire thermotolerance as they approached stationary phase. These finding indicate that Rpi1 functions either downstream of PKA or in parallel to the Ras/cAMP pathway. Second, downregulation of the Ras/cAMP pathway suppressed the heat shock sensitivity of an rpi1 null mutant. This reciprocal suppression suggests that Rpi1 function is not under the control of PKA but, instead, acts in parallel to this kinase. Third, the heat shock sensitivity resulting from hyperactivation of the Ras/cAMP pathway was additive with that of an rpi1 null mutant, further supporting an independent function for Rpi1. Fourth, we found that stimulation of FKS2 transcription by RPI1 overexpression was not affected by hyperactivation of the Ras/cAMP pathway. It remains possible that Rpi1 is a target of the Ras/cAMP pathway whose function is only partially controlled by PKA. However, we have not been able to detect any change in the protein-banding pattern of Rpi1 in response to hyperactivation of the Ras/cAMP pathway (A. Sobering, unpublished). Taken together, these results indicate that Rpi1 functions independently of the Ras/cAMP pathway to oppose the output of PKA.

RPI1 overexpression displayed some specificity for the suppression of mutant phenotypes resulting from hyperactivation of the Ras/cAMP pathway. The phenotypes associated with the failure of these mutants to prepare cells for stationary phase were all suppressed by RPI1. These included failure to acquire thermotolerance as cultures reached saturation, loss of viability during long-term culture, failure to produce glycogen as a storage carbohydrate, and failure to execute changes to the cell wall architecture as cells exited log-phase growth. By contrast, the failure of diploid cells to sporulate in response to nitrogen starvation was not suppressed by RPI1 overexpression. These results suggest that RPI1 function may be restricted to preparing cells for survival of stationary phase. This conclusion was supported by the finding that loss of RPI1 function in an mpk1 null mutant resulted in a striking loss of viability as cultures reached saturation. By contrast, loss of RPI1 function did not appear to affect the growth or viability of the mpk1 mutant during log-phase growth. Moreover, microarray data indicate that the RPI1 mRNA level increases strongly as cells exit log-phase growth (Saccharomyces Genome Database: http://genome-www.stanford.edu/yeast_stress/).

Among the many changes that cells undergo as they prepare for survival in stasis is a fortification of the cell wall (55). We have shown that overexpression of RPI1 drives this process in Ras/cAMP pathway mutants that are compromised in their ability to prepare for stationary phase. We speculate that inappropriate expression of RPI1 during log-phase growth fortifies the cell wall and that this behavior is responsible for suppression of the cell lysis defect of the mpk1 null mutant.

Acknowledgments

We thank Scott Powers, Kelly Tatchell, John Cannon, Fuyu Tamanoi, and Martha Cyert for providing yeast strains and plasmids.

This work was supported by NIH grant GM48533 to D.E.L.

REFERENCES

- 1.Broach, J. R. 1991. RAS genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: signal transduction in search of a pathway. Trends Genet. 7: 28–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buehrer, B., and B. Errede. 1997. Coordination of the mating and cell integrity mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17: 6517–6525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cannon, J. F., J. B. Gibbs, and K. Tatchell. 1986. Suppressors of a ras2 mutation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 113: 247–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cid, V. J., A. Duran, F. Rey, M. P. Snyder, C. Nombela, and M. Sanchez. 1995. Molecular basis of cell integrity and morphogenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Rev. 59: 345–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costigan, C., S. Gehrung, and M. Snyder. 1992. A synthetic lethal screen identifies SLK1, a novel protein kinase homolog implicated in yeast cell morphogenesis and cell growth. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12: 1162–1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davenport, K. R., M. Sohaskey, Y. Kamada, and D. E. Levin. 1995. A second osmosensing signal transduction pathway in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 270: 30157–30161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doduo, E., and R. Treisman. 1997. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae MADS-box transcription factor Rlm1 is a target for the Mpk1 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17: 1848–1859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Douglas, C. M., F. Foor, J. A. Marrinan, N. Morin, J. B. Nielsen, A. M. Dahl, P. Mazur, W. Baginsky, W. Li, M. El-Sherbeini, J. A. Clemas, S. M. Mandala, B. R. Frommer, and M. B. Kurtz. 1994. The Saccaharomyces cerevisiae FKS1 (ETG1) gene encodes an integral membrane protein which is a subunit of 1,3-β-d-glucan synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91: 12907–12911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drgonova, J., T. Drgon, K. Tanaka, R. Kollar, G.-C. Chen, R. A. Ford, C. S. M. Chan, Y. Takai, and E. Cabib. 1996. Rho1p, a yeast protein at the interface between cell polarization and morphogenesis. Science 272: 277–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Errede, B., R. M. Cade, B. M. Yashar, Y. Kamada, D. E. Levin, K. Irie, and K. Matsomoto. 1995. Dynamics and organization of MAP kinase signal pathways. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 42: 477–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gray, J. V., J. P. Ogas, Y. Kamada, M. Stone, D. E. Levin, and I. Herskowitz. 1997. A role for the Pkc1 MAP kinase pathway of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in bud emergence and identification of a putative upstream regulator. EMBO J. 16: 4924–4937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hill J. E., A. M. Muers, T. J. Koemer, and A. Tzagoloff. 1986. Yeast/E. coli shuttle vectors with multiple unique restriction sites. Yeast 2: 163–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gustin, M. C., J. Albertyn, M. Alexander, and K. Davenport. 1998. MAP kinase pathways in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62: 1264–1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inoue, S. B., N. Takewaki, T. Takasuka, T. Mio, M. Adachi, Y. Fujii, C. Miyamoto, M. Arisawa, Y. Furuichi, and T. Watanabe. 1995. Characterization and gene cloning of 1,3-β-d-glucan synthase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eur. J. Biochem. 231: 845–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Irie, K., M. Takase, K. S. Lee, D. E. Levin, H. Araki, K. Matsumoto, and Y. Oshima. 1993. MKK1 and MKK2, which encode Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitogen-activated protein kinase-kinase homologs, function in the pathway mediated by protein kinase C. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13: 3076–3083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ito, H., Y. Fukuda, K. Murata, and A. Kimura. 1983. Transformation of intact yeast cells treated with alkali cations. J. Bacteriol. 153: 163–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacoby, J. J., S. M. Nilius, and J. J. Heinisch. 1998. A screen for upstream components of the yeast protein kinase C signal transduction pathway identifies the product of the SLG1 gene. Mol. Gen. Genet. 258: 148–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jung, U. S., and D. E. Levin. 1999. Genome-wide analysis of gene expression regulated by the yeast cell wall integrity signaling pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 34: 1049–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamada, Y., U. S. Jung, J. Piotrowski, and D. E. Levin. 1995. The protein kinase C-activated MAP kinase pathway of Saccharomyces cerevisiae mediates a novel aspect of the heat shock response. Genes Dev. 9: 1559–1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamada, Y., H. Qadota, C. P. Python, Y. Anraku, Y. Ohya, and D. E. Levin. 1996. Activation of yeast protein kinase C by Rho1 GTPase. J. Biol. Chem. 271: 9193–9195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ketela, T., R. Green, and H. Bussey. 1999. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mid2p is a potential cell wall stress sensor and upstream activator of the PKC1-MPK1 cell integrity pathway. J. Bacteriol. 181: 3330–3340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim, J., and S. Powers. 1991. Overexpression of RPI1, a novel inhibitor of the yeast Ras-cAMP pathway, downregulates normal but not mutationally activated Ras function. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11: 3894–3904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim, Y. J., L. Francisco, G. C. Chen, E. Marcotte, and C. S. M. Chan. 1994. Control of cellular morphogenesis by the Ipl2/Bem2 GTP-activating protein: possible role of protein phosphorylation. J. Cell Biol. 127: 1381–1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klis F. M. 1994. Review: cell wall assembly in yeast. Yeast 10: 851–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee, K. S., K. Irie, Y. Gotoh, Y. Watanabe, H. Araki, E. Nishida, K. Matsumoto, and D. E. Levin. 1993. A yeast mitogen-activated protein kinase homolog (Mpk1) mediates signaling by protein kinase C. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13: 3067–3075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee, K. S., and D. E. Levin. 1992. Dominant mutations in a gene encoding a putative protein kinase (BCK1) bypass the requirement for a Saccharomyces cerevisiae protein kinase C homolog. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12: 172–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee, K. S., L. K. Hines, and D. E. Levin. 1993. A pair of functionally redundant yeast genes (PPZ1 and PPZ2) encoding type 1-related protein phosphatases function within the PKC1-mediated pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13: 5843–5853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levin, D. E., and E. Bartlett-Heubusch. 1992. Mutants in the S. cerevisiae PKC1 gene display a cell cycle-specific osmotic stability defect. J. Cell Biol. 116: 1221–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levin, D. E., B. Bowers, C. Chen, Y. Kamada, and M. Watanabe. 1994. Dissecting the protein kinase C/MAP kinase signaling pathway of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell. Mol. Biol. Res. 40: 229–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levin, D. E., and B. Errede. 1995. The proliferation of MAP kinase signaling pathways in yeast. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 7: 197–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levin, D. E., F. O. Fields, R. Kunisawa, J. M. Bishop, and J. Thomer. 1990. A candidate protein kinase C gene PKC1, is required for the S. cerevisiae cell cycle. Cell 62: 213–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lodder, A. L., T. K. Lee, and R. Ballester. 1999. Characterization of the Wsc1 protein, a putative receptor in the stress response of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 152: 1487–1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manning, B. D., R. Padmanabha, and M. Snyder. The Rho-GEF Rom2p localizes to sites of polarized cell growth and participates in cytoskeletal functions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 8: 1829–1844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Mazur, P., N. Morin, W. Baginsky, M. El-Sherbeini, J. A. Clemas, J. B. Nielsen, and F. Foor. 1995. Differential expression and function of two homologous subunits of yeast 1,3-β-d-glucan synthase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15: 5671–5681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nonaka, H. K. Tanaka, H. Hirano, T. Fujiwara, H. Kohno, M. Umikawa, A. Mino, and Y. Takai. 1995. A downstream target of RHO1 small GTP-binding protein is PKC1, a homolog of protein kinase C, which leads to activation of the MAP kinase cascade in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 14: 5931–5938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ono, T., T. Suzuki, Y. Anraku, and H. Iida. 1994. The MID2 gene encodes a putative integral membrane protein with a Ca(2+)-binding domain and shows mating pheromone-stimulated expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene 151: 203–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ozaki, K., K. Tanaka, H. Imamura, T. Hihara, T. Kamayema, H. Nonaka, H. Hirano, Y. Matsuura, and Y. Takai. 1996. Rom1p and Rom2p are small GDP/GTP exchange proteins (GEPs) for the Rho1p small GTP-binding protein in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 15: 2196–2207. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peterson, J., Y. Zheng, L. Bender, A. Myers, R. Cerione, and A. Bender. 1994. Interactions between the bud emergence proteins Bem1 and Bem2 and the Rho-type GTPases in yeast. J. Cell Biol. 127: 1395–1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Philip, B., and D. E. Levin. 2001. Wsc1 and Mid2 are cell surface sensors for cell wall integrity signaling that act through Rom2, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Rho1. Mol. Cell Biol. 21: 271–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paravicini, G., M. Cooper, L. Friedli, D. J. Smith, J.-L. Carpentier, L. S. Klig, and M. A. Payton. 1992. The osmotic integrity of the yeast cell requires a functional PKC1 gene product. Mol. Cell Biol. 12: 4896–4905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qadota, H., C. P. Python, S. B. Inoue, M. Arisawa, Y. Anraku, Y. Zheng, T. Watanabe, D. E. Levin and Y. Ohya. 1996. Identification of yeast Rho1p GTPase as a regulatory subunit of 1,3-β-glucan synthase. Science 272: 279–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ram, A. F. J., S. S. C. Brekelmans, L. J. W. M. Oehlen, and F. M. Klis. 1995. Identification of two cell cycle regulated genes affecting the β-1,3-glucan content of cell wall in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 358: 165–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rajavel, M., B. Philip, B. M. Buehrer, B. Errede, and D. E. Levin. 1999. Mid2 is a putative sensor for cell integrity signaling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19: 3969–3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rose, M. D., F. Winston, and P. Hieter. 1990. Methods in yeast genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 45.Sass, P., J. Field, J. Nikawa, T. Toda, and M. Wigler. 1986. Cloning and characterization of the high-affinity cAMP phosphodiesterase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 83: 9303–9307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schmidt, A., M. Bickle, T. Beck, and M. Hall. 1997. The yeast phosphatidylinositol kinase homolog TOR2 activates RHO1 and RHO2 via the exchange factor ROM2. Cell 88: 531–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sikorski, R. S., and P. Hieter. 1989. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 122: 19–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tanaka, K., M. Nakafuka, T. Satoh, M. Marshall, J. B. Gibbs, K. Matsumoto, Y. Kaziro, and A. Toh-e. 1990. S. cerevisiae genes IRA1 and IRA2 encode proteins that may be functionally equivalent to mammalian ras GTPase activating protein. Cell 60: 803–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thevelein, J. M., and J. H. de Winde. 1999. Novel sensing mechanisms and targets for the cAMP-protein kinase A pathway in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Microbiol. 33: 904–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Toda, T., S. Cameron, P. Sass, M. Zoller, J. D. Scott, B. McMullen, M. Hurwitz, E. G. Krebs, and M. Wigler. 1987. Cloning and characterization of BCY1, a locus encoding a regulatory subunit of the cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7: 1371–1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Toda, T., I. Uno, T. Ishikawa, S. Powers, T. Kataoka, D. Broek, S. Cameron, J. Broach, K. Matsumoto, and M. Wigler. 1985. In yeast, RAS proteins are controlling elements of adenylate cyclase. Cell 40: 27–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vema, J., A. Lodder, K. Lee, A. Vagts, and R. Ballester. 1997. A family of genes required for the maintenance of cell wall integrity and for the stress response in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94: 13804–13809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Watanabe, M., C.-Y. Chen, and D. E. Levin. 1994. Saccharomyces cerevisiae PKC1 encodes a protein kinase C (PKC) homolog with a substrate specificity similar to that of mammalian PKC. J. Biol. Chem. 269: 16829–16836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Watanabe, Y., G. Takaesu, M. Hagiwara, K. Irie, and K. Matsumoto. 1997. Characterization of a serum response factor-like protein in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Rlm1, which has transcriptional activity regulated by the Mpk1 (Slt2) mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17: 2615–2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Werner-Washburne, M., E. Braun, G. C. Johnston, and R. A. Singer. 1993. Stationary phase in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Rev. 57: 383–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Willingham, M. C., I. Pastan, T. Y. Shih, and E. M. Scolnick. 1980. Localization of the src gene product of the Harvey strain of MSV to plasma membrane of transformed cells by electron microscopic immunochemistry. Cell 19: 1005–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhao, C., U. S. Jung, P. Garrett-Engele, T. Y. Roe, M. S. Cyert, and D. E. Levin. ( 1998) Temperature-induced expression of yeast FKS2 is under the dual control of protein kinase C and calcineurin. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18: 1013–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]