Abstract

Background

A pregnant woman's psychological health is a significant predictor of postpartum outcomes. The Antenatal Psychosocial Health Assessment (ALPHA) form incorporates 15 risk factors associated with poor postpartum outcomes of woman abuse, child abuse, postpartum depression and couple dysfunction. We sought to determine whether health care providers using the ALPHA form detected more antenatal psychosocial concerns among pregnant women than providers practising usual prenatal care.

Methods

A randomized controlled trial was conducted in 4 communities in Ontario. Family physicians, obstetricians and midwives who see at least 10 prenatal patients a year enrolled 5 eligible women each. Providers in the intervention group attended an educational workshop on using the ALPHA form and completed the form with enrolled women. The control group provided usual care. After the women delivered, both groups of providers identified concerns related to the 15 risk factors on the ALPHA form for each patient and rated the level of concern. The primary outcome was the number of psychosocial concerns identified. Results were controlled for clustering.

Results

There were 21 (44%) providers randomly assigned to the ALPHA group and 27 (56%) to the control group. A total of 227 patients participated: 98 (43%) in the ALPHA group and 129 (57%) in the control group. ALPHA group providers were more likely than control group providers to identify psychosocial concerns (odds ratio [OR] 1.8, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.1–3.0; p = 0.02) and to rate the level of concern as “high” (OR 4.8, 95% CI 1.1–20.2; p = 0.03). ALPHA group providers were also more likely to detect concerns related to family violence (OR 4.8, 95% CI 1.9–12.3; p = 0.001).

Interpretation

Using the ALPHA form helped health care providers detect more psychosocial risk factors for poor postpartum outcomes, especially those related to family violence. It is a useful prenatal tool, identifying women who would benefit from additional support and interventions.

The psychosocial health of a pregnant woman and her family is a significant predictor of intrapartum, newborn and postpartum outcomes.1,2,3,4 A critical review of the literature has identified an association between antenatal psychosocial risk factors and the poor postpartum outcomes of woman abuse, child abuse, postpartum depression and couple dysfunction.5

Clinicians have indicated that a practical tool to help them systematically collect and record prenatal psychosocial information would be helpful.6Although specific and often well-validated tools are available to predict or detect child abuse, woman abuse or depression,7,8,9,10 clinicians are unlikely to use them because of time constraints.1 Other forms aid in collecting more comprehensive antenatal psychosocial data,11,12,13,14 but they are not evidence-based, and were developed to predict obstetric or newborn rather than psychosocial outcomes.

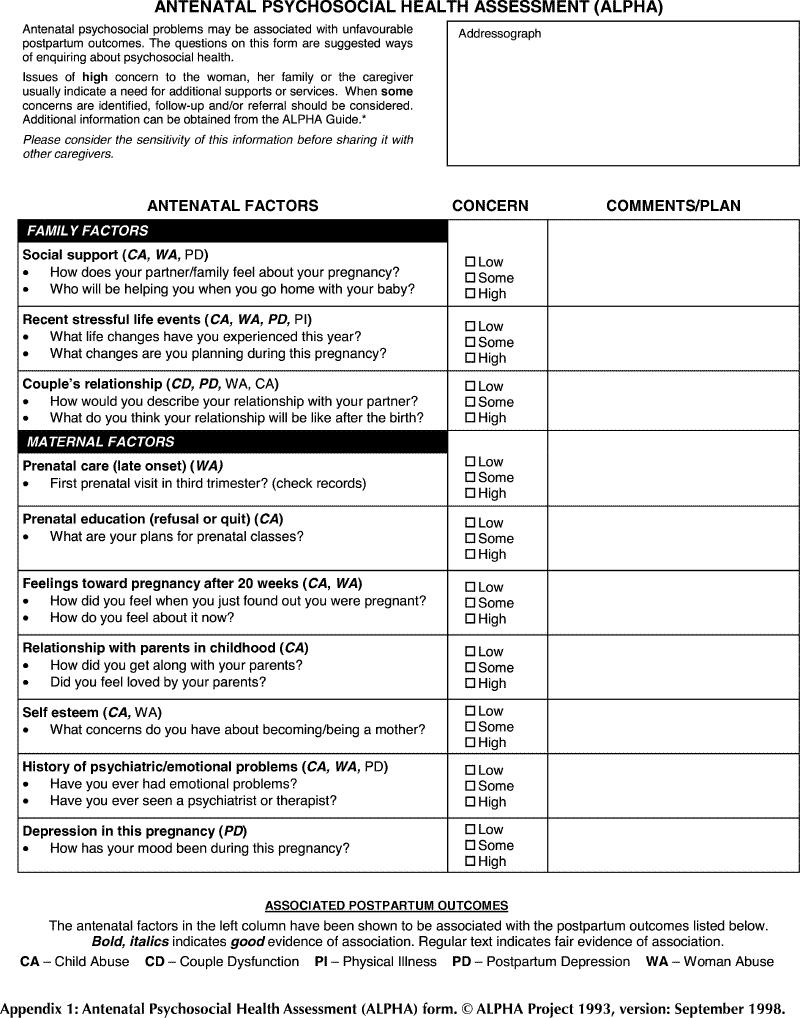

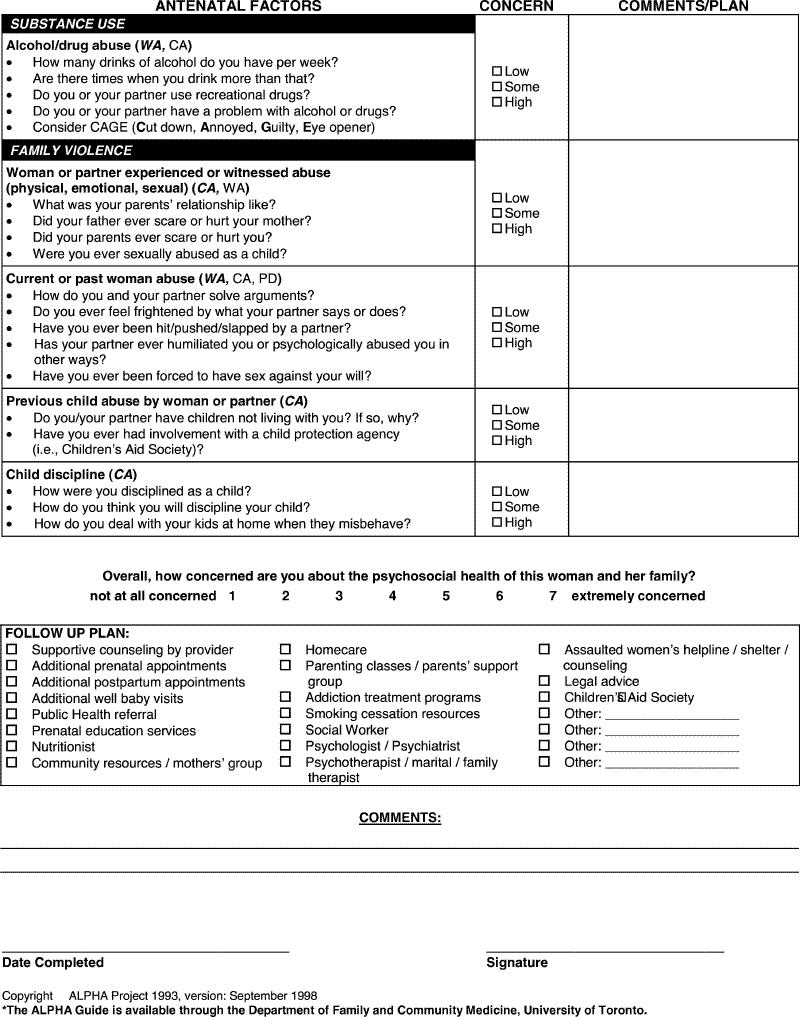

In contrast, the Antenatal Psychosocial Health Assessment (ALPHA) form (Appendix 1) was designed to identify antenatal psychosocial risk factors for poor postnatal psychosocial outcomes. It incorporates 15 risk factors found through critical literature review5 to be associated with woman abuse, child abuse, postpartum depression and couple dysfunction.15 These risk factors are grouped intuitively by topic, with suggested questions, into 4 categories: family factors, maternal factors, substance use and family violence. The ALPHA form has been field-tested by obstetricians, family physicians, midwives and nurses,15,16 who have found using it to be feasible and useful.15 Pregnant women appreciate and feel comfortable with the psychosocial enquiry.15 The ALPHA form was developed as a screening tool to help providers systematically identify areas of psychosocial concern. Once feasibility was established,15 the next step was to determine whether using it in regular practice would increase the number of concerns identified.

We sought to determine whether health care providers using the ALPHA form detected more antenatal psychosocial concerns in their pregnant patients than clinicians practising usual prenatal care. A secondary objective was to determine women's and providers' satisfaction with the ALPHA form.

Methods

Four communities in Ontario were chosen as study sites, including urban, suburban and small-town practices, with patients from diverse socioeconomic and ethnic backgrounds. Family physicians, obstetricians and midwives were approached at rounds with information about the study and invited to participate. Interested health care providers were sent an introductory letter with a fax-back form, which was followed by a telephone call from 1 of the investigators to determine whether they would participate. Practitioners were eligible if they practised prenatal and intrapartum care or prenatal care with transfer of care for delivery after 28 weeks, provided care for 10 or more prenatal patients per year, and were not currently using any prenatal psychosocial screening tool other than the standard Ontario Antenatal Record.

To obtain a balanced sample, each participating provider was paired to the greatest extent possible with another provider by practice location, type of provider, sex and age. One member of each pair was randomly assigned to the ALPHA or control group by a biostatistician using computer-generated random numbers.

Providers were asked to enroll 5 consecutive pregnant women who were between 12 and 30 weeks' gestation, able to read and write English and give consent. Women were excluded if they were at high obstetric risk as defined by the Ontario Antenatal Record, such as those with pre-existing diabetes, renal disease, severe hypertension or heart disease.

Interested women received an explanatory brochure and consent form from their provider and a phone call from the study nurse to further explain the study and secure consent. Participants completed a questionnaire on demographic and obstetric details along with several psychosocial instruments (not reported in this paper).8,17,18,19,20,21,22

Intervention group providers attended a 1-hour workshop on the ALPHA form given by 1 or more of the investigators. This interactive session included a review of the evidence for the ALPHA form, specific interview questions, role play, management strategies for partner violence and a summary of community resources for psychosocial problems. Once trained, providers completed the ALPHA form with enrolled women at a prenatal visit of the provider's choice between 20 and 32 weeks' gestation. Risk factors were rated as being of concern if they raised concern in the woman, her family or the provider. Women whose providers were in the control group continued to receive usual care.

All of the providers completed a data collection sheet entitled “Psychosocial concerns” on each of the enrolled women within 1 month after the last woman delivered. They were asked whether they had any concerns about the women, with specific reference to the psychosocial risk factors on the ALPHA form. For each patient, providers identified whether each of the 15 risk factors raised concern and, using their clinical judgment, rated the level of concern as “low,” “some” or “high.” Providers were advised that concerns rated as “high” would be those they were more likely to act on. For the study, issues were considered to be of concern if the level of concern was rated as “some” or “high.” Both groups could refer to their antenatal records to fill out the form, and the intervention group could also refer to their antenatal ALPHA forms. Providers in the intervention group were also given a questionnaire about their experience using the ALPHA form.

At 4 months postpartum, the study nurse contacted all women in the trial to again complete a number of psychosocial instruments.17,18,19,20,21,22,23 Women with providers in the ALPHA group were asked to give feedback about the ALPHA form.

At completion of the study, ALPHA group providers received $50 per woman and control group providers $20 per woman for time spent completing the documentation. Women received $25 to help defray their expenses. The study took place between 1998 and 2002, with staggered participation by each site. Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Toronto Research Ethics Board and the McMaster University Research Ethics Board.

The intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) in primary care settings for process variables is of the order of 0.05– 0.15,24 whereas the ICCs for outcome variables are generally lower than 0.05. We assumed an estimate of the ICC of 0.05 for the outcome variables. From previous work, it was estimated that a significant psychosocial concern would be detected in 5% of women. A 10% increase in detection (from baseline of 5%–15%) was considered clinically significant. A sample of 33 providers and 5 women per provider, which translates into 165 women in each group, was chosen to detect a 10% difference between the 2 groups (type I error = 0.05, power = 0.80) after adjustment for clustering of women by provider.25

We limited the analysis to patients who completed the study. However, we also did a sensitivity analysis by intention to treat to account for the 9 providers in the ALPHA group and the 3 providers in the control group who dropped out. Each missing provider was imputed with 5 patients, each with 0 psychosocial concerns.

All of the available data are reported for each question. χ2 tests were used to compare proportions, and t tests and nonparametric tests were used to compare means of continuous variables between the 2 groups. For the analysis of the primary study question and the response to ALPHA categories, a 2-sided p value less than 0.05 was taken to indicate a statistically significant finding, but for the analysis of the 15 risk factors, significance was set at 0.01. Hierarchical logistic regression was used to control for clustering of women per provider.

Results

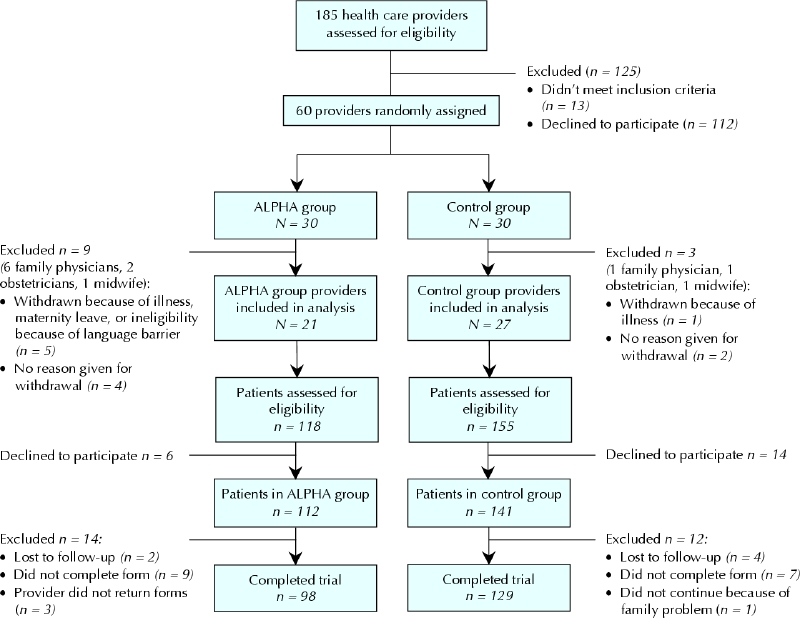

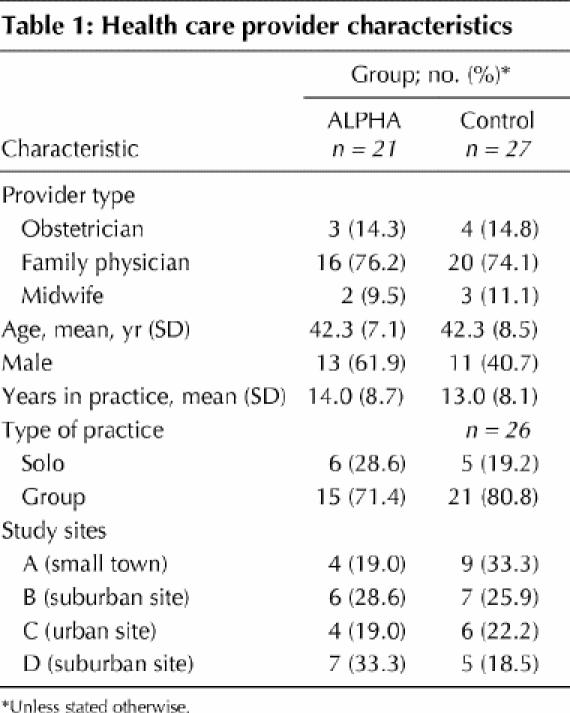

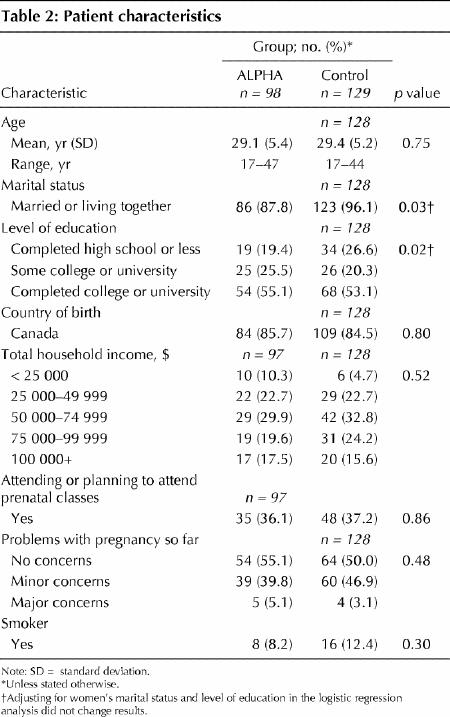

A total of 21 (44%) health care providers in the ALPHA group and 27 (56%) in the control group were included in the analysis (Fig. 1). There was a greater loss to follow-up of providers and patients in the intervention arm. If reasons likely unrelated to completing the ALPHA form are omitted, there were 4 provider dropouts in the ALPHA group and 2 in the control group. If provider-driven reasons are omitted (e.g., did not complete or return data collection forms), the number of patient dropouts was similar (9.8% in the ALPHA group, 8.5% in the control group). There were no significant differences in characteristics between the 2 groups of providers (Table 1). Each provider recruited an average of 5 women (range 1–7). Of 273 patients enrolled, 118 (43%) received the intervention and 155 (57%) received standard care. The only significant differences in characteristics between the 2 groups of patients were marital status and level of education (Table 2).

Fig. 1: Flow of health care providers and patients through the trial.

Table 1

Table 2

ALPHA group providers identified 115 psychosocial concerns in 98 women, whereas control group providers identified 96 concerns in 129 women (odds ratio [OR] 1.8, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.1–3.0; p = 0.02). Of the 115 concerns identified by ALPHA group providers, 23 were rated as high; of 96 concerns identified by control group providers, 7 were rated as high (OR 4.8, 95% CI 1.1–20.2; p = 0.03). The intracluster correlation based on the fitted model was 0.16.

ALPHA group providers identified at least 1 psychosocial concern in 38 of 98 (39%) women, and control group providers identified at least 1 psychosocial concern in 38 of 129 (29%) women (p = 0.14). Providers indicated a high level of concern about psychosocial issues in 11 (11.2%) women in the ALPHA group and 3 (2.3%) in the control group (p = 0.006). In the ALPHA group, 18 of 21 (86%) providers found at least 1 issue of concern in 1 of their patients compared with 22 of 27 (81%) providers in the control group. For continuous variables, nonparametric tests gave the same conclusions as t tests.

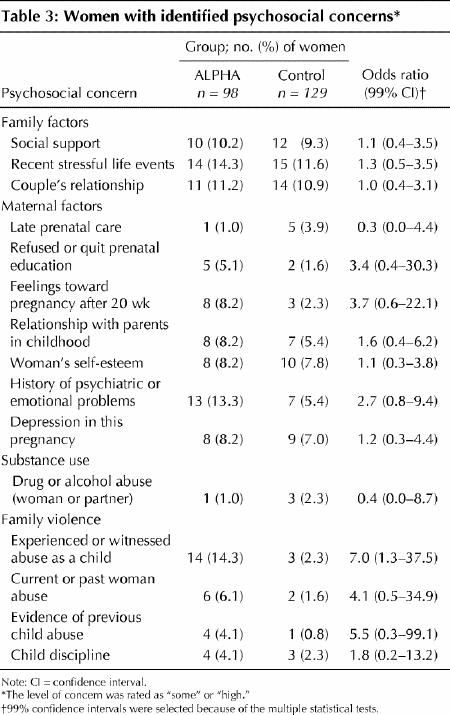

Table 3 shows the number of women in the 2 groups identified as having an antenatal risk factor of concern for each of the 15 items on the “Psychosocial concerns” form.

Table 3

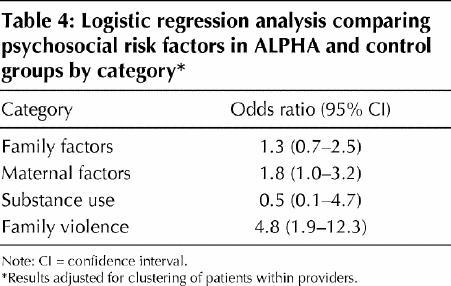

When data for the 15 risk factors were grouped into the 4 categories of the ALPHA form (family factors, maternal factors, substance use and family violence), the only category that was significant was family violence (Table 4). Women with providers in the ALPHA group were almost 5 times as likely to be identified with risk factors related to family violence than women with providers in the control group. Adjusting for marital status and education did not change the results.

Table 4

Women with providers in the ALPHA group were asked for feedback on their experience with the ALPHA form. The majority of women felt comfortable discussing personal issues (72.7%) and felt that this was part of their provider's job (76.3%).

Only 14 of 21 (67%) of the ALPHA group providers completed the feedback form. Most found the ALPHA form easy to use (64%) and would use it if recommended as standard practice (86%). They all reported finding at least “a little” new psychosocial information using the ALPHA form; 86% reported uncovering “a lot” or a “moderate amount.” When asked if they would prefer to use the ALPHA form or have women complete a “self-report” version that our group has developed and evaluated,16 the provider-completed ALPHA was preferred by 28%, a woman self-report by 36% and a choice of either by 36%.

Interpretation

The results of this study demonstrate that health care providers who used the ALPHA form detected almost twice as many antenatal psychosocial concerns as providers who did not use the form. The ALPHA form appears to have functioned effectively in practice situations with different providers. The results also show that pregnant women valued psychosocial enquiry and that providers found it useful. Particularly important was the increased detection of risk factors associated with family violence, an area that results of previous studies have shown to be problematic, given providers' discomfort with the subject.6 Whether a woman had experienced or witnessed abuse as a child, a risk factor associated with child abuse and woman abuse, was detected 7 times more often by those using the ALPHA form.

Our study has limitations. Use of the ALPHA form resulted in detection of more psychosocial concerns overall but did not show striking results for each factor. Small numbers limited the strength of the analysis, and provider dropout may have played a factor. A sensitivity analysis, performed to account for provider dropouts, changed the odds ratio for identifying a concern to 1.005 (95% CI 0.6–1.7, p = 0.98) and for identifying an issue with a high level of concern to 2.8 (95% CI 0.7–11.7, p = 0.16). Family violence remained significant as a category (OR 2.7, 95% CI 1.1–6.9, p = 0.04) in this “worst case” scenario. Participating providers were potentially those who were willing to enquire about psychosocial issues and may not reflect most caregivers; this may have diminished the differences in outcomes. The majority of participants were family physicians, and therefore the results are more reflective of their practice style and may not be generalizable to midwives and obstetricians. The greater loss to follow-up of providers and patients in the intervention group may be the result of the increased time involved completing the form. A self-report version of the ALPHA form has been developed in response to providers' concerns about time constraints and has been found to be acceptable to women and providers, and effective in gathering information.16

The ALPHA form has been demonstrated to increase detection of the antenatal psychosocial risk factors that are associated with woman abuse, child abuse, postpartum depression and couple dysfunction. It was well accepted by women and clinicians. Studies are underway to demonstrate the reliability of the ALPHA form, and future studies are needed to show whether using the form leads to improved psychosocial outcomes. We suggest that the ALPHA form is a useful addition to routine prenatal care.

β See related article page 267

Acknowledgments

We thank the many family physicians, obstetricians, midwives and women who helped us with this study. We would also especially like to thank the site coordinators, Gerda Halliday, Myrna Henry, Mary Ann Van Os and Debbie Sheehan. We also thank Dr. Rahim Moinnedin and Dr. Preeti Prakash for their help with the analysis. This study was funded by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care and the Ontario Women's Health Council.

Appendix 1.

Appendix 1. Continued.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: June Carroll, Anthony Reid, Anne Biringer, Deana Midmer, Donna Stewart, Lynn Wilson, Beverley Chalmers, Patricia Pugh and Freda Seddon contributed substantially to the conception and design of the study. June Carroll, Anthony Reid, Anne Biringer and Patricia Pugh were responsible for the acquisition of data. June Carroll, Anthony Reid, Anne Biringer, Rick Glazier, Deana Midmer, Joanne Permaul and Donna Stewart were responsible for the analysis and interpretation of the data and drafting of the article. All of the authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and approved the final version.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. June Carroll, Mount Sinai Hospital, 600 University Ave., Suite 413, Toronto ON M5G 1X5; jcarroll@mtsinai.on.ca

References

- 1.Haglund LJ, Britton JR. The perinatal assessment of psychosocial risk. Clin Perinatol 1998;25:417-52. [PubMed]

- 2.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Psychosocial risk factors: Perinatal screening and intervention. ACOG Educational Bulletin 255. Washington, DC: The College; 1999. [PubMed]

- 3.Health Canada. Family-centred maternity and newborn care: National guidelines. Ottawa: Minister of Public Works and Government Services; 2000.

- 4.Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. Guidelines for care during pregnancy and childbirth. SOGC clinical practice guidelines — policy statement no. 71. Toronto: The Society; 1998.

- 5.Wilson LM, Reid AJ, Midmer DK, Biringer A, Carroll JC, Stewart DE. Antenatal psychosocial risk factors associated with adverse postpartum family outcomes. CMAJ 1996;154:785-99. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Carroll JC, Reid AJ, Biringer A, Wilson LM, Midmer DK. Psychosocial risk factors during pregnancy: What do family physicians ask about? Can Fam Physician 1994;40:1280-9. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Sherin KM, Sinacore JM, Li XQ, Zitter RE, Shakil A. HITS: a short domestic violence screening tool for use in a family practice setting. Fam Med 1998;30:508-12. [PubMed]

- 8.Brown JB, Lent B, Brett PJ, Sas G, Pederson LL. Development of the woman abuse screening tool for use in family practice. Fam Med 1996;28:422-8. [PubMed]

- 9.Posner NA, Unterman RR, Williams DN, Williams GH. Screening for postpartum depression. An antepartum questionnaire. J Reprod Med 1997;42: 207-15. [PubMed]

- 10.MacMillan HL, MacMillan JH, Offord DR. Periodic Health Examination, 1993 update: 1. Primary prevention of child maltreatment. The Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination. CMAJ 1993;148:151-63. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Forde R, Malterud K, Bruusgaard D. Antenatal care in general practice. 1: A questionnaire as a clinical tool for collection of information on psychosocial conditions. Scand J Prim Health Care 1992;10:266-71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Curry MA, Campbell RA, Christian M. Validity and reliability testing of the prenatal psychosocial profile. Res Nurs Health 1994;17:127-35. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Orr ST, James SA, Casper R. Psychosocial stressors and low birth weight: development of a questionnaire. J Dev Behav Pediatr 1992;13:343-7. [PubMed]

- 14.Norwood SL. The social support APGAR: instrument development and testing. Res Nurs Health 1996;19:143-52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Reid AJ, Biringer A, Carroll JC, Midmer D, Wilson LM, Chalmers B, et al. Using the ALPHA form in practice to assess antenatal psychosocial health. CMAJ 1998;159(6):677-84. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Midmer D, Bryanton J, Brown R. Assessing antenatal psychosocial health. Randomized controlled trial of two versions of the ALPHA form. Can Fam Physician 2004;50:80-7. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Bavolek SJ. Handbook for the adult–adolescent parenting inventory. Eau Claire, WI: Family Development Resources Inc.; 1984. p. 1-71.

- 18.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br J Psychiatry 1987;150:782-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Spainer GB. Manual for the dyadic adjustment scale. New York: Multi-Health Systems Inc.; 1989. p. 1-43.

- 20.Stewart AL, Hays RD, Ware JE Jr. The MOS short-form general health survey. Reliability and validity in a patient population. Med Care 1988;26:724-35. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Veit CT, Ware JE Jr. The structure of psychological distress and well-being in general populations. J Consult Clin Psychol 1983;51:730-42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Stewart AL, Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB. Psychological distress/well-being and cognitive functioning measures. In: Stewart AL, Ware JE Jr, editors. Measuring functioning and well-being: The medical outcomes study approach. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 1992. p.102-42.

- 23.Cutrona CE. Causal attributions and perinatal depression. J Abnorm Psychol 1983;92:161-72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Campbell MK, Mollison J, Steen N, Grimshaw JM, Eccles M. Analysis of cluster randomized trials in primary care: a practical approach. Fam Pract 2000; 17:192-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Donner A, Klar N. Design and analysis of cluster randomization trials in health research. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000.