Abstract

Background

During the COVID-19 pandemic, youth in Ontario, Canada experienced a steep rise in mental health concerns. Preventative intervention programs can address the psychological impact of the pandemic on youth and build resiliency. Co-design approaches to developing such programs actively involve young people, resulting in solutions tailored to their unique needs. The current paper details the co-design approach to creating a Preventative Online Mental Health Program for Youth (POMHPY)—a virtually delivered program designed for Ontario youth ages 12 to 25 that promotes mental, physical, and social wellbeing.

Methods

The Participatory Action Research (PAR) framework guided the development of the initiative. Literature reviews were conducted to identify existing evidence-based programs targeting youth. Youth perspectives were primarily gathered via the Youth Advisory Group, comprising a Youth Resilience Coordinator and a Youth Engagement Lead, who contributed to a literature review, surveys, focus groups, and program assets. Community insights were gathered through Community Reference Group (CRG) meetings, which engaged participants from local and provincial organizations, as well as individuals either directly representing or affiliated at arm's length with youth.

Results

A review of the current literature highlighted the importance of regular physical activity, social connectedness, good sleep hygiene, and healthy family relationships to emotional wellbeing. Survey findings informed program session length, duration, delivery, and activities. Focus groups expanded on the survey findings and provided an in-depth understanding of youth preferences for program delivery. CRG meetings captured community insights on program refinements to better meet the needs of youth. As such, the development of POMHPY was a collaborative effort among researchers, youth, and community partners.

Conclusions

The findings highlight the value of co-design and PAR-informed approaches in developing youth-targeted online wellbeing programs, providing actionable insights for iterative improvements and future pilot testing. The resulting 6-week program, led by youth facilitators, will focus on teaching mental, social, and physical wellness strategies and skills through various evidence-based, interactive activities.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12913-024-12101-w.

Keywords: Youth mental health, Youth prevention program, Co-design, Participatory action research, Quality improvement project, Youth wellbeing, Online program

Background

Results of a global study illustrate that mental health disorders most commonly emerge during youth, with the peak age of onset typically between 14 and 24 years old [1]. The mental burden influenced by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated this risk, leading to a noticeable rise in symptoms of anxiety and depression, as well as a decrease in physical activity and social interactions [2–4]. The self-perceived mental health of Canadian youth declined by 20% from 2019 to 2020 [5].

Accordingly, there is an increasing demand for equitable and targeted preventative mental health programs for youth to mitigate risks, enhance coping skills, and foster resilience [6–8]. Research from past mass traumas and natural disasters indicates that resiliency and social connectivity are vital for community recovery [9–12]. Consequently, implementing preventative programs may help reduce the psychological impact of the pandemic on youth by promoting these essential characteristics [13].

In the wake of the pandemic, more online programs emerged in response to the lockdown and social distancing laws that prevented in-person options [14]. Online mental health interventions offer improved efficiency, accessibility, and effectiveness in addressing mental health concerns among young people, reaching individuals who might not otherwise seek in-person help [15]. These programs cross geographic boundaries, improve reach among youth, and are more accessible than their in-person counterparts [16]. The flexible nature of these programs caters to youth unable or reluctant to attend face-to-face programs and may provide a sense of community and connection for those experiencing social isolation [17]. However, these advantages may be influenced by program development methodologies, particularly those that guide how the program will address the nuanced needs of diverse youth.

Over the past decade, there has been a steady shift towards employing collaborative, bottom-up frameworks for developing mental health programs by and for youth [18]. This evolving trend seeks to create more inclusive and contextually relevant interventions that better address the diverse needs and experiences of the population served, including youth [19, 20]. Bottom-up approaches prioritize grassroots involvement from community members and acknowledge end-user needs, values, and priorities [21, 22]. Co-design is one such approach used in developing and implementing youth mental health services [23]. This method collaboratively engages users as partners to create solutions, products, or services tailored to their unique needs [24, 25].

The following project used a co-design approach that emphasized collaborating with youth in Ontario, Canada throughout all project stages to develop the Preventative Online Mental Health Program for Youth (POMHPY). The non-clinical program aimed to provide youth across the developmental spectrum with skills and strategies to address mental health challenges arising from and following the COVID-19 pandemic. The development process highlights the importance of considering the perspectives of youth and the community in online mental wellbeing program design.

Methods

Co-design and participatory action research

The study used co-design to ensure program development was driven by youth and community member input. Youth were actively involved in all stages including design, outreach, and data collection. Community meetings offered additional insights to ensure a diverse range of perspectives shaped the program’s design. This approach aligns with co-design principles, emphasizing collaborative involvement in program development [26, 27].

Traditional co-design approaches, while valuable for incorporating user preferences, can sometimes overlook the deeper social and environmental factors that contribute to a target population's challenges [23, 28, 29]. Recognizing the necessity of incorporating young people's perspectives, strengths, and skills in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic [30, 31], the project used Participatory Action Research (PAR) to guide youth engagement practices [32, 33]. The PAR framework aims to improve health and reduce inequities by involving individuals in reflection, data collection, and action [32].

PAR is a collaborative research approach that engages both researchers and community members as co-researchers, focusing on creating knowledge to address social issues and drive change. It prioritizes the lived experiences of those directly affected by these issues, integrating their insights to develop practical, action-oriented solutions. Key components of PAR include relationship-building, shared understanding of the problem, collaborative analysis, and taking action [34]. The method empowers communities through local ownership of the research process, addressing power imbalances and supporting equitable, emancipatory social change.

In the current project, youth engagement was characterized by meaningful participation and sustained involvement in developing POMHPY [35, 36]. By centring youth voices throughout the process, PAR ensured the program directly captured youth voices on pandemic-related factors, such as social isolation, environmental pressures, or lack of access to mental health resources, that may influence program design [37]. Therefore, PAR strengthens co-design by fostering a holistic exploration of youth mental health and its social determinants, aligning with youth empowerment and social justice principles [38, 39].

The project applied the three main principles of PAR [33]: (1) promote co-learning and mutual capacity building while also acknowledging and valuing community members’ lived experiences; (2) power-sharing through shared decision-making and co-ownership of the knowledge produced within the project team; and (3) consistent dialogue and collaboration with the project team and community to integrate positive change. The framework enabled active engagement with partners and emphasized youth input and collaboration throughout all stages of POMHPY development [40].

Setting and objectives

The project was based at Waypoint Centre for Mental Health Care (Waypoint), a psychiatric hospital with an embedded research institute in Ontario, Canada. The hospital provides an extensive range of mental health and substance use inpatient and outpatient services, including those supporting youth. Using co-design approaches, this quality improvement (QI) project aimed to (1) use existing evidence-based programs to inform the development of POMHPY, a preventative, online, wellbeing program for youth between the ages of 12 and 25; and (2) leverage the perspectives, lived experiences, input, and collaborations from youth and community partners to co-design POMHPY.

Consultation with Waypoint’s Research Ethics Board (REB) determined that the study was exempt from formal ethical review as this was a QI project focused on adapting existing evidence-based programs for youth in Ontario, Canada. Consultation with the REB was critical since ethical exemption for QI projects is not to be determined by project investigators, but by an ethics committee [41]. Informed consent was required to ensure that participants were aware of the project details and any identifying information was redacted from the findings.

Youth project team

Given that POMHPY was developed by and for young people between the ages of 12 and 25, youth comprised a large portion of the project team to ensure representativeness. Specifically, the project team included a Youth Advisory Group, consisting of a Youth Resilience Coordinator and Youth Engagement Lead who were both over 18 years of age and identified as white. These team members were undergraduate and graduate psychology and counselling students who were responsible for leading various components of the project, particularly community outreach and facilitating partnerships with other youth and relevant organizations across Ontario, Canada. The Youth Advisory Group’s primary responsibility was to interact with diverse youth participants to gather their feedback. The Youth Advisory Group also contributed to developing the program website and material, presentations, data collection and analysis, and promotional materials. Ad-hoc youth members of the team included a Knowledge Translation and Implementation Coordinator and undergraduate research students who provided additional youth perspectives in their respective roles. A detailed overview of all groups involved in this project is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of roles, responsibilities and contributions of group involved in POMHPY development

| Group Involved | Group Description | Key responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| Researchers | PhD research scientists leading project | Oversaw the project and supervised the project team, including the Youth Advisory Group, guided data collection and analysis, and managed overall study design and administration |

| Research coordinator | PhD-level team member | Managed administrative tasks, organized data and community meetings, and coordinated between stakeholders |

| Youth Advisory Group | Youth Resilience Coordinator and Youth Engagement Lead | Played a leadership role, facilitated community outreach, co-developed data collection materials and presentations, led focus groups, and developed the project website |

| Ad-hoc youth project members | Knowledge Translation and Implementation Coordinator and undergraduate research students | Provided youth perspectives and led knowledge translation throughout development, including summarizing findings for community meetings and website |

| Community partners | Parents, youth advisors, schoolteachers, principals, mental health professionals, and service agencies | Provided feedback on program content during community meetings, particularly regarding inclusivity and credibility |

| Youth participants | Youth ages 12–25 years from different regions in Ontario, Canada | Participated in surveys and focus groups, informing program development by sharing lived experiences |

Development stages and timeline

Development: Stage 1

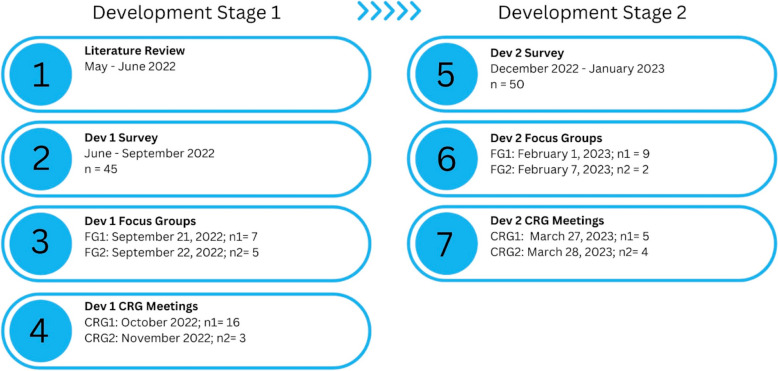

The first development stage (Fig. 1) collected data to inform program structure. Initially, a literature review of systematic and narrative review papers was conducted on articles published between 2020 and 2022 to explore youth mental health experiences since the onset of the pandemic. The review findings informed the 45-item Dev1 Survey (Additional file 1), which was available to Ontario youth between June and September 2022. The survey captured basic demographics, use of free time, physical health and screen time, sleeping habits, effects of the pandemic on wellbeing, elements youth wanted to see in the program, and whether they preferred online or in-person delivery. Recruitment posters were circulated through local and provincial partner organizations. After providing written consent, the survey was administered to volunteer participants via REDcap, an online survey platform. Youth who completed the survey received a $25 e-gift card for their time.

Fig. 1.

Development stages project workflow outlining details of the POMHPY program’s development stages 1 and 2

To expand on the survey findings, two virtual focus groups (Dev1 Focus Groups) led by the Youth Advisory Group were held on September 21 and 22, 2022. The questions aimed to capture youths’ program preferences, needs, and barriers to participation. The 90-min focus groups were conducted on Zoom, and questions were presented on Mentimeter, a virtual survey platform. Participants had the opportunity to respond either verbally, or through text via Zoom chat and Mentimeter. Focus group data were captured by facilitators using field notes of verbal responses, Zoom chats, and responses provided on Mentimeter. To prevent redundancy in data collection and considering the various methods used for gathering focus group information, interviews were not recorded. Focus group participants received a $40 e-gift card for their time. A summary of the focus group findings was used to inform program development.

In line with a community-focused approach [42], local and provincial partners, whom the Youth Resilience Coordinator previously identified, were invited via a standardized email script to join a 60-min Community Reference Group (CRG) discussion on October 3, 2022 (Dev1 CRG 1). Three one-to-one CRG meetings (Dev1 CRG 2) were organized on November 18, 24, and 25, 2022, with partners who were unable to attend Dev1 CRG 1. Community partners included parents, youth advisors, schoolteachers and principals, researchers, mental health professionals, and service agencies. The core project team presented a slide deck detailing the project background and program milestones at the beginning of the meeting, followed by findings from the Dev1 Survey and Dev1 Focus Groups. The subsequent discussion captured community partner perspectives on the relevancy of program activities and delivery format and how to actively engage youth. Meeting minutes were recorded by the project Research Coordinator, reviewed by the team, and applied to program development.

Development: Stage 2

In the second stage (Fig. 1), the core program structure was created, and program implementation was discussed. A second survey (Dev2 Survey; Additional file 1) was developed using Stage 1 data. The survey focused on basic demographics, preferences on focusing on social, psychological, and physical wellbeing, activities to include, integration of a discussion board, opinions on youth facilitators, collaborations with community centres, program logistics, and modalities to access course material. The 32-item survey and corresponding consent form were uploaded onto REDCap. The survey was available from December 5, 2022 to January 5, 2023, and recruitment advertisements were shared through community partners and the research team’s personal networks. Participants received a $10 e-gift card for their time.

Subsequently, youth were engaged to pilot the first session in a 90-min virtual focus groups (Dev2 Focus Group). Held on February 1 and 7, 2023, the focus groups included screenshots of the program and participants were guided through a pilot run of Session 1. The focus group questions centred on participants’ experiences with the session, and they were able to share their responses verbally or through Mentimeter. Similar to Dev1 Focus Group, field notes were recorded. Recommendations were discussed with the project team and used to refine the program and address barriers to participation where possible and feasible.

Lastly, two 60-min CRG discussions (Dev2 CRG) were held with community partners on March 27 and 28, 2023. Meeting minutes were recorded and the project team presented a slide deck highlighting the proposed program delivery format, auxiliary components, and prospective implementation initiatives. The discussions centred on sustainable program implementation and strategies to enhance participant recruitment.

Data analysis

Descriptive survey data was analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Mac, version 24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA). No missing data were observed in the survey responses. Each item was assessed individually, and the reported count percentages were relative to the total responses of the specific item. Categorical variables were reported using the frequency of responses and percentages, and continuous variables were reported as medians, means, ranges, and standard deviations. Qualitative data were analyzed using a qualitative description approach that remained close to participant accounts [43]. A narrative report summarizing participant responses was then developed. The Youth Advisory Group conducted the analysis, and the findings were presented to the project team for discussion.

Results

Review of COVID-19 impact on youth mental health

Eight reviews (n = 6 systematic reviews and n = 2 narrative reviews) focused on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on youth mental health [44–51]. A marked increase in rates of stress/anxiety and depression was reported in youth since the onset of the pandemic [44, 46, 47, 50, 51]. Risk factors included gender and sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, and mental health status [44, 48, 50, 51]. Conversely, social connectedness, healthy family relationships, regular physical activity, and good sleep hygiene were key areas associated with improved mental wellbeing [45, 49].

Survey and focus group participants

In the first development stage, N = 45 youth across various regions in Ontario responded to the Dev1 Survey. The average age of participants was 21 (SD = 3.64), with a range of 12 to 25 years. The majority of participants (75.6%; 34/45) were over the age of 18. Most identified as girl/woman (64%; 29/45), 42% self-identified as non-marginalized (19/45), and 22% (10/45) were part of the 2SLGBTQQIA + community (Additional file 2: Table S1). Subsequently, participants were re-engaged to take part in one of two Dev1 Focus Groups (n1 = 7, n2 = 5).

In the second stage of development, N = 50 youth from across Ontario participated in Dev2 Survey (Additional file 2: Table S2). The average age of participants was 20.6 years (SD = 3.22), with a range of 15 to 25 years. Most participants (64%; 32/50) were over the age of 18 and identified as girl/women (66%; 33/50). Similar to the first development stage, two Dev2 Focus Groups (n1 = 9, n2 = 2) were held.

Program preferences

Program preferences of Dev1 Survey respondents were influenced by the impact of COVID-19 on their mental health. Notably, participants experienced feelings of isolation (33.3%; n = 15/45), loneliness (22.2%; n = 10/45), social and general anxiety (17.8%; n = 8/45), reduced social skills (13%; n = 6/45), concentration issues (11%; n = 5/45), feeling depressed (8.9%; 4/45), lack of motivation (6.7%; n = 3/45), self-harm (4.4%; = 2/45), and poor self-image (2.2%; n = 1/45).

With respect to the program, respondents preferred self-directed drop-in sessions, with both virtual (37.8%; n = 17/45) and in-person (42.2%; n = 19/45) delivery formats being acceptable. Additionally, most participants preferred attending sessions twice per month (37.8%; n = 17/45), followed by once per week (26.7%; n = 12/45). More than half of the participants (53.3%; n = 24/45) opted for one-hour sessions. Lastly, the most requested program elements included peer-support groups (33.3%; n = 15/45), artistic/creative programming (31.1%; n = 14/45), mindfulness activities (24.4%; n = 11/45), and resources for stress and anxiety (24.4%; n = 11/45) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Program elements Dev1 Survey findings highlighting key elements participants preferred to be integrated into the POMHPY program

Dev1 Focus Group participants viewed virtual programs as highly accessible to youth, but barriers included privacy concerns and suitable learning environments. Participants indicated that the program should be led by youth facilitators and comprise groups of 5 to 10 individuals. In terms of potential psychological wellbeing activities for the program, participants reported being at least somewhat likely to participate in activities related to culinary arts (100%; n = 12/12), stress release journaling (50%; n = 6/12), mindfulness (50%; n = 6/12), affirmations and positive self-talk (67%; n = 8/12), and creative arts (58%; n = 7/12). Few participants were interested in meditation (25%; n = 3/12), with youth proposing a limit of no more than five minutes per session. There was also a willingness to participate in physical wellbeing activities (58% willing; n = 7/12 and 42% somewhat willing; n = 5/12), with high interest expressed in engaging in light to vigorous aerobic exercises and developing personalized activity routines. Primary motivations for physical activity included the desire to remain healthy (35%; 7/20 responses) and to socialize (20%; 4/20 responses).

In line with developing a program that addressed equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI), participants were asked to identify possible barriers to participation. While 92% (11/12) of participants noted they and their peers had reliable access to a laptop and internet, lack of privacy (58%, n = 7/12) and poor access to stable Wi-Fi and electronic devices (50%, n = 6/12) were the two most suggested barriers to consider. Participants were also asked about ways in which the program developers could engage with underrepresented and marginalized youth. Participants found it important to connect with community organizations and schools that support these populations. Inviting participants to share their preferred pronouns and names was also suggested.

Community feedback on program design

In the first CRG meeting (Dev 1 CRG 1), the Youth Resilience Coordinator invited n = 32 community partners. From those engaged, n = 11 partners and n = 5 project team members attended the meeting, representing organizations local to Simcoe County (n = 7) and other regions across Ontario (n = 4). Partners noted the importance of highlighting the non-clinical nature of the program—that is, program facilitators are peer supporters, not mental health professionals, and that the program is not a form of counselling or therapy. Some also proposed having one youth and one adult ally, such as a trained mental health peer support staff, to co-facilitate the sessions. The first session was viewed as critical to building trust and developing connections with youth. Partners also proposed creating student placement positions for students in undergraduate psychology or closely related programs to fill the roles of youth facilitators. Lastly, connections with community partners were seen as an important way to refer participants to other programs that could further benefit their wellbeing.

Subsequent one-on-one CRG meetings (Dev 1 CRG 2) were conducted with a pediatrician, registered psychotherapist, and development psychologist who were unable to attend Dev 1 CRG 1. These clinicians supported virtual programming and maintaining interpersonal participant engagement in between sessions using a youth-approved digital platform. Clinicians emphasized the importance of highlighting the preventative nature of the program, increasing psychoeducational opportunities, and managing participant safety and engagement through small cohorts grouped by age and interests (i.e., 12 to 17 vs. 18 to 25; culinary vs. art).

Learnings from the CRG meetings helped identify, adapt, and integrate evidence-based interventions that addressed youth wellbeing [52–57]. These included short mindfulness exercises [52], art therapy including drawing and music [53, 55], physical activity guidelines and low-intensity exercises like qigong [54, 57], and the Thayer Matrix to understand stress, energy, and tension [56].

Likelihood of participating in POMHPY

When asked about the likelihood of participating in different activities, most Dev2 Survey respondents were at least somewhat likely to participate in artistic and creative activities (72%; n = 36/50), followed by self-guided low-intensity physical exercise (72%; n = 36/50), culinary activities (68%; n = 34/50), self-guided high-intensity exercises (64%; n = 32/50), journaling (66%; 33/50), music-based activities (66%; 33/50), practicing positive self-talk (60%; n = 30), mindfulness breathing exercises (56%; n = 28/50), performing wellness check-ins (56%; n = 28/50), self-massage techniques to calm and self-regulate (54%; n = 27/50), and vocal activities (28%; n = 14/50) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Likelihood of participation Dev2 Survey findings indicating the likelihood of participation in potential POMHPY program activities

With respect to incorporating peer facilitators, 90% of participants (n = 45/50) supported incorporating a youth peer support worker. When asked about the age of facilitators, 43% of responses (23/54) indicated a preference for someone 25 or younger, 20% (11/54) preferred someone older than 25, and 37% (20/54) reported having no preference. Ten participants (20%) also preferred peer facilitators from underrepresented groups. When asked about accessibility, 88% (n = 44/50) reported they would access the program by phone, and 62% (n = 31/50) preferred electronic course material. The large majority of participants (90%; n = 45/50) also reported that they would find an email reminder before each session to be helpful.

Pilot session feedback

The findings from the first stage of development were used to co-design POMHPY. Each session included a check-in activity, a review of confidentiality and safe space guidelines, an icebreaker activity, a review of the previous week’s activities, a brief mindfulness practice, psychoeducation and a main activity related to the session’s theme, instructions on optional after-session activities, and a check-out. A program guide, which included the session details and activities, was also provided to participants. A list of the topics covered in each of the six sessions can be found in Additional file 2: Figure S1. To test the co-designed program, a Session 1 pilot was hosted by the Youth Advisory Group.

Session 1 pilot was positively received. When asked what aspects of the pilot they liked, participants noted that they enjoyed the activities and found the session to be engaging. With respect to session activities, the music-based activities were most preferred, and the mindfulness activity was the least popular part of the session, alongside the icebreaker. Suggestions to improve the program included working with schools for implementation, more activity options, and more time on the session’s main activity. Overall, it was clear to most participants that the program was preventative in nature (57.1%; n = 4/7 responses “yes” and 42.9%; n = 3/7 responses “somewhat”).

Regarding program guides, many participants indicated a preference to be called “Youth Wellness Guides” (82%, n = 9/11). Participants found the guides easy to read, visually appealing, and engaging, and the visual aids within the books were reported as helpful. Suggestions to improve the guides were to provide additional space for typing/filling in the books, make the PDFs editable, and make them more user-friendly, with suggestions including adding a table of contents, adding timestamps to correspond with the session agenda items, and further distinguishing activities from information within the books.

To address EDI, participants were consulted on potential barriers to program-specific elements. For example, feedback on the culinary activity included being mindful of dietary restrictions, access to a kitchen and utensils, and offering food allergen substitutes where possible. These barriers may have contributed to most participants preferring artistic activities (88.9%; n = 8/9 responses) over culinary ones (11.1%; n = 8/9 responses). Participants also believed it was important to work with schools for recruitment as many students could benefit from this program.

Community input on implementation and recruitment

From the N = 45 partners invited, n = 9 partners (n1 = 5, n2 = 4) and n = 6 project team members attended. Within the partners, n = 8 represented organizations local to Simcoe County and n = 1 represented an organization within the province of Ontario. Key takeaways from the meeting were program sustainability and implementation feasibility initiatives. Partners suggested offering community service hours and compensation for participants, training and implementing the program within provincial organizations, and using feasible recruitment strategies such as social media, schools, community youth counsellors and programs, and youth events.

Discussion

The current QI project used a co-design approach to develop POMHPY, a wellbeing program for Ontario youth ages 12 to 25 years. Guided by the PAR framework [58, 59], the stepped approach to program development involved continual collaborations with youth and community partners. This approach resulted in a program tailored to young people’s unique needs. Further, many of the participants identified with marginalized groups, highlighting the importance of inclusivity and accessibility of the online program. Taken together, the findings highlight the significance of the co-design process when developing POMHPY.

Having youth occupy leadership roles on the program team was a unique element of this project and was critical to gathering the perspectives of young people. Members of the Youth Advisory Group led community engagement and outreach efforts, and supported program development and dissemination of study findings. Not only did this strategy co-construct important perspectives to program design, but it also equipped youth team members with valuable skill sets and professional development opportunities. Similar to previous studies, it is important for project teams to integrate training for youth members and provide opportunities to apply their learnings to various components of the project [60]. In line with the PAR framework, the project ensured that youth benefit from participation, are credited for their work, and are remunerated beyond monetary compensation [61].

In the process of program development, it was important to triangulate data, including findings from the literature review, as well as perspectives of youth and community members gathered through surveys, focus groups, and CRG meetings. The literature review highlighted existing evidence-based programs that could be adapted [52–57]. Surveys supported program adaptation by providing a general overview of requested program components, and the focus groups added depth and a fulsome understanding of why these elements were significant and how they could be integrated into POMHPY. For instance, although mindfulness was positively viewed by participants, and there is substantial evidence outlining its positive impact on youth [62, 63], the current data indicates that activities beyond meditation are preferred. Furthermore, there is evidence that youth prefer programs with activities that enable them to put learning into practice rather than those that solely focus on psychoeducation. These findings further support the importance of collaborative approaches in program design.

The inclusion of CRG meetings provided insights into the local context; clinician, parent, and partner organization perspectives and buy-in; and important feasibility and practicality considerations. For example, infrastructure, costs, legalities, and practicality are important considerations that may be beyond the knowledge scope of the youth involved [25, 64]. Many of the suggestions from youth-focused community members reflect the persistent issues organizations have with program access and system fragmentation [65, 66]. A notable example was suggestions to clarify that the program targets wellbeing and is not a clinical program or treatment. Indeed, mental health has had a longstanding rehabilitative stance on programming, and it is only recently that preventative mental health programs have burgeoned [67, 68].

As demonstrated in this project and others, mental health interventions can help reduce mental health disparities among marginalized populations by overcoming traditional barriers to care and providing accessible and quality mental health services through digital platforms [69].

To enhance EDI, the implementation of preventative programs like POMHPY may need to consider current public views on mental health programming and promote availability to all youth, including those within non-clinical populations. Schools were strongly suggested as important areas to integrate the program. Although race and ethnicity were not discussed in the context of barriers, youth involved in the co-design of POMHPY shed light on the importance of considering access. For instance, given that participants were dispersed across the province, variable access to the internet was not uncommon. Although access to the internet is beyond the scope of the POMHPY project, factors like technology options for participation, digital literacy and privacy, and strategies to deal with access difficulties can help mitigate some of the challenges that are inherent in digital programs [70, 71]. Furthermore, other barriers, such as limited kitchen access expressed by participants, highlight the necessity for all program activities to address and provide suitable alternatives for individuals unable to participate in the conventional manner.

POMHPY program content and format

The first iteration of POMHPY was co-designed and refined by integrating the voices and perspectives of youth and youth-focused individuals and organizations. The six-week program comprises weekly one-hour sessions facilitated by youth peer leaders trained in wellbeing program delivery. The program will be delivered via Zoom, and a corresponding participant portal with the program material and discussion board will be available through the project website. POMHPY’s structure will be based on three main pillars identified during the literature review: mental, physical, and social wellbeing [16, 72]. Based on the provided feedback, the program draws on music, culinary and fine arts, physical activity, and mindfulness to support wellbeing. Addressing the need for safe spaces, the sessions open with a land acknowledgement [73, 74], a check-in, and a description of safe spaces and confidentiality expectations while on online platforms. Participants will also be encouraged to add their preferred pronouns and names. The sessions will commence with a short icebreaker, a review of the previous week’s activities, and a brief mindfulness practice. The week’s theme will be explored, followed by two activities that put the learnings into practice. The session will then close with a check-out and available resources for additional support. All participants will receive a program guide that details the sessions and includes question prompts to further facilitate their engagement with the program in between sessions.

Given that this is a QI project, the program will continue to gather feedback through a pilot phase and incorporate it into program delivery. Notably, the first iteration of POMHPY was intentionally designed to offer skills and strategies that are inclusive for all youth across the developmental spectrum. The program is expected to go through several iterations after piloting POMHPY in various youth age groups. The pilot findings are anticipated to reveal age-specific nuances, which will help further tailor the program.

Limitations

While the study had many benefits, discussion on its limitations is also warranted. QI projects commonly involve gathering data in small samples, making frequent adjustments to protocols and interventions, discarding ineffective ideas, and advancing those that prove successful. One challenge in classifying QI projects as traditional research lies in the dynamic nature of their framework. Unlike traditional research with its established methodologies, QI methodologies adapt to the specific context and needs of the project [75]. This adaptability often results in smaller sample sizes compared to traditional research. At the same time, the process of data collection, as well as the feedback and ideas presented, can be considered in other youth wellbeing initiatives and projects. Additionally, the majority of participants, including those within the Youth Advisory Group, were older youth who identified as white girls/women. While it is important to focus on methods to enhance engagement across all genders and marginalized groups, the findings align with current trends. Specifically, girls/women are more likely to seek help for their mental health concerns [76]. Moreover, older youth are more likely to participate since mental health diagnoses tend to appear between ages 15 and 18 and this age group typically have a greater understanding of their health concerns and help-seeking compared to their younger counterparts [77, 78]. Although there is ongoing debate about eliminating the division of youth programs into older and younger subgroups [14], pilot testing of the POMHPY program will provide valuable insights into how such programs impact younger youth, especially when predominantly co-designed with older youth participants. Moreover, it is noted that although over 50% of the participants self-identified as being part of an equity-denied group an equity-denied group and provided their input in surveys and focus groups, the project’s Youth Advisory Group comprised non-minoritized university students. Future studies and iterations of the POMHPY program will benefit from investigating methods to encourage diverse youth participation, including those from ethnoculturally minoritized populations.

The identified limitations draw attention to the importance of prioritizing methods of equitable engagement in the next steps of program implementation, ensuring that the program supports a broad range of youth demographics and experiences.

Lessons learned

The development of POMHPY underscored the critical importance of human resources, funding, and supportive infrastructure. Equitable compensation plays a key role in involving members of the target population, as recognized in previous research [79, 80]. This project highlighted the need for adequate budgeting, particularly the allocation of sufficient funds to allow youth members to take on paid roles, further empowering them to assume leadership responsibilities. Moreover, projects like POMHPY require significant coordination among community partners, youth participants, the advisory group, and host hospital. These cross-functional collaborations necessitate adherence to a variety of policies and procedures across different sectors. Flexibility in timelines and strong communication strategies proved essential in meeting the diverse needs of those involved in the project and navigating the complexity of working with multiple groups.

Safeguarding also emerged as a key takeaway throughout the project, especially given the involvement of youth as peer researchers and advisory group members [81]. In accordance with hospital policies, all hired team members were youth aged 18 years or older. This approach ensured alignment with both project goals and institutional regulations, maintaining the safety of participants while achieving meaningful youth engagement. Although the broad age range of participants (12–25 years) was not explicitly discussed as a limitation—likely due to the primary focus being on program content—it is an important factor to consider during program implementation. Procedures will be established to ensure the safety of all individuals involved, with specific measures to protect minors and provide age-appropriate engagement opportunities.

Conclusion

The current QI study provides insight into the various methods to engage youth and the community, triangulate data, and collect data that informs rapid improvements and modifications to a youth-targeted online wellbeing program. Focusing on POMHPY, the findings support a co-design approach informed by PAR for program development. A future pilot of the program will guide its next iteration.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

SK obtained funding for the project. SK, KB, and EM designed the project. EM, KB, SF, SS, and SK wrote the main manuscript text. SF and SS prepared Figs. 1–3. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

The project was funded by the TD Ready Commitment grant.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The quality improvement project was exempt from formal ethical review by Waypoint Centre for Mental Health Care’s Research Ethics Board. All participants provided written informed consent prior to their involvement. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Solmi M, Radua J, Olivola M, Croce E, Soardo L, Salazar de Pablo G, et al. Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27:281–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cost KT, Crosbie J, Anagnostou E, Birken CS, Charach A, Monga S, et al. Mostly worse, occasionally better: impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of Canadian children and adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021;31:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Mahboubi P, Higazy A. Lives put on hold: The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Canada’s Youth. CD Howe Inst Comment. 2022;624:1–25. https://www.cdhowe.org/sites/default/files/2022-07/Commentary_624_R4.pdf.

- 4.McCoy K, Kohlbeck S. Intersectionality in pandemic youth suicide attempt trends. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2022;52:983–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Statistics Canada. Canadians report lower self-perceived mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. 2020. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2020001/article/00003-eng.htm. Accessed 18 Mar 2024.

- 6.Colizzi M, Lasalvia A, Ruggeri M. Prevention and early intervention in youth mental health: is it time for a multidisciplinary and trans-diagnostic model for care? Int J Ment Health Syst. 2020;14:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGorry PD, Mei C, Chanen A, Hodges C, Alvarez-Jimenez M, Killackey E. Designing and scaling up integrated youth mental health care. World Psychiatry. 2022;21:61–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murphy J, Sawula E, Pavkovic M, Vandervoort S. Identifying areas of focus for mental health promotion in children and youth. 2015.

- 9.Heymann DL, Shindo N. COVID-19: what is next for public health? Lancet. 2020;395:542–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Polizzi C, Lynn SJ, Perry A. Stress and coping in the time of covid-19: pathways to resilience and recovery. Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2020;17:59–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Shaw SC. Hopelessness, helplessness and resilience: The importance of safeguarding our trainees’ mental wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nurse Educ Pract. 2020;44:102780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Smith GD, Ng F, Li WHC. COVID‐19: Emerging compassion, courage and resilience in the face of misinformation and adversity. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29:1425–1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Djalante R, Shaw R, DeWit A. Building resilience against biological hazards and pandemics: COVID-19 and its implications for the Sendai Framework. Prog Disaster Sci. 2020;6:100080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.van Doorn M, Nijhuis LA, Egeler MD, Daams JG, Popma A, van Amelsvoort T, et al. Online Indicated Preventive Mental Health Interventions for Youth: A Scoping Review. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:580843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Piers R, Williams JM, Sharpe H. Can digital mental health interventions bridge the ‘digital divide’for socioeconomically and digitally marginalised youth? A systematic review. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2023;28:90–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clarke AM, Kuosmanen T, Barry MM. A systematic review of online youth mental health promotion and prevention interventions. J Youth Adolesc. 2015;44:90–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prescott J, Hanley T, Ujhelyi GK. Why do young people use online forums for mental health and emotional support? Benefits and challenges. Br J Guid Couns. 2019;47:317–27. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masterson D, Areskoug Josefsson K, Robert G, Nylander E, Kjellström S. Mapping definitions of co-production and co-design in health and social care: A systematic scoping review providing lessons for the future. Health Expect. 2022;25:902–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akiva T, Petrokubi J. Growing with youth: A lifewide and lifelong perspective on youth-adult partnership in youth programs. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2016;69:248–58. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alvarez-Jimenez M, Rice S, D’Alfonso S, Leicester S, Bendall S, Pryor I, et al. A novel multimodal digital service (moderated online social therapy+) for help-seeking young people experiencing mental ill-health: pilot evaluation within a national youth e-mental health service. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e17155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katapally TR. Smart indigenous youth: The smart platform policy solution for systems integration to address indigenous youth mental health. JMIR Pediatr Parent. 2020;3:e21155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singer J, Bennett-Levy J, Rotumah D. “You didn’t just consult community, you involved us”: transformation of a ‘top-down’Aboriginal mental health project into a ‘bottom-up’community-driven process. Australas Psychiatry. 2015;23:614–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tindall RM, Ferris M, Townsend M, Boschert G, Moylan S. A first-hand experience of co-design in mental health service design: Opportunities, challenges, and lessons. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2021;30:1693–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanders EB-N, Stappers PJ. Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. Co-Des. 2008;4:5–18. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thabrew H, Fleming T, Hetrick S, Merry S. Co-design of eHealth Interventions With Children and Young People. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:00481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Vargas C, Whelan J, Brimblecombe J, Allendera S. Co-creation, co-design and co-production for public health: a perspective on definitions and distinctions. Public Health Res Pract. 2022;32:3222211. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Robert G, Locock L, Williams O, Cornwell J, Donetto S, Goodrich J. Co-producing and co-designing. Cambridge University Press; 2022.

- 28.Singh DR, Sah RK, Simkhada B, Darwin Z. Potentials and challenges of using co-design in health services research in low- and middle-income countries. Glob Health Res Policy. 2023;8:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Slattery P, Saeri AK, Bragge P. Research co-design in health: a rapid overview of reviews. Health Res Policy Syst. 2020;18:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allemang B, Cullen O, Schraeder K, Pintson K, Dimitropoulos G. Recommendations for youth engagement in Canadian mental health research in the context of COVID-19. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021;30:123–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rivera A, Okubo Y, Harden R, Wang H, Schlehofer M. Conducting virtual youth-led participatory action research (YPAR) during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Particip Res Methods. 2022;3. https://jprm.scholasticahq.com/article/37029-conducting-virtual-youth-ledparticipatory-action-research-ypar-during-the-covid-19-pandemic.

- 32.Baum F, MacDougall C, Smith D. Participatory action research. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2006;60:854–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iwasaki Y, Springett J, Dashora P, McLaughlin A-M, McHugh T-L, Youth 4 YEG Team. Youth-guided youth engagement: Participatory action research (PAR) with high-risk, marginalized youth. Child Youth Serv. 2014;35:316–42. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cornish F, Breton N, Moreno-Tabarez U, Delgado J, Rua M, de-Graft Aikins A, et al. Participatory action research. Nat Rev Methods Primer. 2023;3:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dunne T, Bishop L, Avery S, Darcy S. A review of effective youth engagement strategies for mental health and substance use interventions. J Adolesc Health. 2017;60:487–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramey HL, Mahdy SS, Lawford HL, Rose-Krasnor L, Lakman Y, Ross M, et al. Youth engagement and mental health preliminary report. Centre of Excellence for Youth Engagement; 2018.

- 37.Smith KE, Acevedo-Duran R, Lovell JL, Castillo AV, Cardenas Pacheco V. Youth Are the Experts! Youth participatory action research to address the adolescent mental health crisis. MDPI; 2024. p. 592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Doucet M, Pratt H, Dzhenganin M, Read J. Nothing about us without us: Using participatory action research (PAR) and arts-based methods as empowerment and social justice tools in doing research with youth ‘aging out’of care. Child Abuse Negl. 2022;130:105358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Powers C, Allaman E. How Participatory Action Research Can Promote Social Change and Help Youth Development (December 17, 2012). Berkman Center Research Publication No. 2013-10, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2199500 or 10.2139/ssrn.2199500. [DOI]

- 40.Bevan Jones R, Stallard P, Agha SS, Rice S, Werner-Seidler A, Stasiak K, et al. Practitioner review: Co-design of digital mental health technologies with children and young people. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2020;61:928–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oermann MH, Barton A, Yoder-Wise PS, Morton PG. Research in nursing education and the institutional review board/ethics committee. J Prof Nurs. 2021;37:342–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Porche MV, Folk JB, Tolou-Shams M, Fortuna LR. Researchers’ Perspectives on Digital Mental Health Intervention Co-Design With Marginalized Community Stakeholder Youth and Families. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:867460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Sandelowski M. Using qualitative research. In: Qualitative Health Research. 2004. p. 1366–86. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Cost KT, Crosbie J, Anagnostou E, Birken CS, Charach A, Monga S, et al. Mostly worse, occasionally better: impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of Canadian children and adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022;31:671–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferguson KN, Coen SE, Tobin D, Martin G, Seabrook JA, Gilliland JA. The mental well-being and coping strategies of Canadian adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative, cross-sectional study. CMAJ Open. 2021;9:E1013–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gadermann AC, Thomson KC, Richardson CG, Gagné M, McAuliffe C, Hirani S, et al. Examining the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on family mental health in Canada: findings from a national cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e042871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hawke LD, Barbic SP, Voineskos A, Szatmari P, Cleverley K, Hayes E, et al. Impacts of COVID-19 on youth mental health, substance use, and well-being: a rapid survey of clinical and community samples: Répercussions de la COVID-19 sur la santé mentale, l’utilisation de substances et le bien-être des adolescents : un sondage rapide d’échantillons cliniques et communautaires. Can J Psychiatry. 2020;65:701–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hawke LD, Sheikhan NY, MacCon K, Henderson J. Going virtual: youth attitudes toward and experiences of virtual mental health and substance use services during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21:340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kiss O, Alzueta E, Yuksel D, Pohl KM, de Zambotti M, Műller-Oehring EM, et al. The pandemic’s toll on young adolescents: prevention and intervention targets to preserve their mental health. J Adolesc Health. 2022;70:387–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Salmon S, Taillieu TL, Fortier J, Stewart-Tufescu A, Afifi TO. Pandemic-related experiences, mental health symptoms, substance use, and relationship conflict among older adolescents and young adults from Manitoba. Canada Psychiatry Res. 2022;311:114495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Turna J, Zhang J, Lamberti N, Patterson B, Simpson W, Francisco AP, et al. Anxiety, depression and stress during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results from a cross-sectional survey. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;137:96–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Wit EE, Bunders-Aelen J, Regeer BJ. Reducing stress in youth: A pilot-study on the effects of a university-based intervention program for university students in Pune. India J Educ Dev Psychol. 2016;6:53. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hui HM, Ma’rof AM. Improving undergraduate students’ positive affect through mindful art therapy. Int J Acad Res Progress Educ Dev. 2019;8:757–77. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roberts KC, Yao X, Carson V, Chaput J-P, Janssen I, Tremblay MS. Meeting the Canadian 24-hour movement guidelines for children and youth. Health Rep. 2017;28:3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rodríguez-Carvajal R, Lecuona O. Mindfulness and music: A promising subject of an unmapped field. Int J Behav Res Psychol. 2014;2:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thayer RE. The origin of everyday moods: Managing energy, tension, and stress. USA: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Waechter RL, Wekerle C. Promoting resilience among maltreated youth using meditation, yoga, tai chi and qigong: A scoping review of the literature. Child Adolesc Soc Work J. 2015;32:17–31. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gibbs L, Kornbluh M, Marinkovic K, Bell S, Ozer EJ. Using technology to scale up youth-led participatory action research: A systematic review. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67:S14–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Raanaas RK, Bjøntegaard H, Shaw L. A scoping review of participatory action research to promote mental health and resilience in youth and adolescents. Adolesc Res Rev. 2020;5:137–52. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Clark AT, Ahmed I, Metzger S, Walker E, Wylie R. Moving from co-design to co-research: engaging youth participation in guided qualitative inquiry. Int J Qual Methods. 2022;21:16094069221084792. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cullen O, Walsh CA. A narrative review of ethical issues in participatory research with young people. Young. 2020;28:363–86. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Filipe MG, Magalhães S, Veloso AS, Costa AF, Ribeiro L, Araújo P, et al. Exploring the effects of meditation techniques used by mindfulness-based programs on the cognitive, social-emotional, and academic skills of children: A systematic review. Front Psychol. 2021;12:660650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Porter B, Oyanadel C, Sáez-Delgado F, Andaur A, Peñate W. Systematic review of mindfulness-based interventions in child-adolescent population: A developmental perspective. Eur J Investig Health Psychol Educ. 2022;12:1220–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Malloy J, Partridge SR, Kemper JA, Braakhuis A, Roy R. Co-design of digital health interventions with young people: A scoping review. Digit Health. 2023;9:20552076231219116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Henderson JL, Chiodo D, Varatharasan N, Andari S, Luce J, Wolfe J. Youth wellness hubs Ontario: development and initial implementation of integrated youth services in Ontario. Canada Early Interv Psychiatry. 2023;17:107–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Settipani CA, Hawke LD, Cleverley K, Chaim G, Cheung A, Mehra K, et al. Key attributes of integrated community-based youth service hubs for mental health: a scoping review. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2019;13:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bani M, Zorzi F, Corrias D, Strepparava M. Reducing psychological distress and improving student well-being and academic self-efficacy: the effectiveness of a cognitive university counselling service for clinical and non-clinical situations. Br J Guid Couns. 2022;50:757–67. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fusar-Poli P, Correll CU, Arango C, Berk M, Patel V, Ioannidis JP. Preventive psychiatry: a blueprint for improving the mental health of young people. World Psychiatry. 2021;20:200–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schueller SM, Hunter JF, Figueroa C, Aguilera A. use of digital mental health for marginalized and underserved populations. Curr Treat Options Psychiatry. 2019;6:243–55. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Spicer Z, Goodman N, Olmstead N. The frontier of digital opportunity: Smart city implementation in small, rural and remote communities in Canada. Urban Stud. 2021;58:535–58. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Strudwick G, Sockalingam S, Kassam I, Sequeira L, Bonato S, Youssef A, et al. Digital interventions to support population mental health in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic: rapid review. JMIR Ment Health. 2021;8:e26550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Das JK, Salam RA, Lassi ZS, Khan MN, Mahmood W, Patel V, et al. Interventions for adolescent mental health: an overview of systematic reviews. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59:S49–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Finegan C. Reflection, acknowledgement, and justice: A framework for indigenous-protected area reconciliation. Int Indig Policy J. 2018;9. https://ojs.lib.uwo.ca/index.php/iipj/article/view/7550.

- 74.Herrera S. Land Acknowledgement Guide. 2020.

- 75.Varkey P, Reller MK, Resar RK. Basics of quality improvement in health care. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:735–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Haavik L, Joa I, Hatloy K, Stain HJ, Langeveld J. Help seeking for mental health problems in an adolescent population: the effect of gender. J Ment Health. 2019;28:467–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kim-Cohen J, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Milne BJ, Poulton R. Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: developmental follow-back of a prospective-longitudinal cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:709–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Radez J, Reardon T, Creswell C, Lawrence PJ, Evdoka-Burton G, Waite P. Why do children and adolescents (not) seek and access professional help for their mental health problems? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021;30:183–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Vaughn LM, Jacquez F, Zhen-Duan J. Perspectives of community co-researchers about group dynamics and equitable partnership within a community-academic research team. Health Educ Behav. 2018;45:682–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chaffee R, Todd KT, Gupta P, May S, Abouelkheir M, Lagodich L, et al. Methods for co-researching with youth: a cross-case analysis of centering anti-adultist frameworks. Int J Qual Methods. 2024;23:16094069241286844. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hawke LD, Relihan J, Miller J, McCann E, Rong J, Darnay K, et al. Engaging youth in research planning, design and execution: Practical recommendations for researchers. Health Expect. 2018;21:944–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.