Abstract

Lunaria annua is an underexplored crop with promising potential for use in various industries: food, oil etc. It grows rapidly, has low maintenance and high resistance to pathogens, which makes it a promising crop for sustainable cultivation. Herein, we investigated nutritional value, phenolic profile, and bioactive properties of L. annua seeds collected in the wild. The results we obtained indicate that seeds of L. annua have high energy value (406.6 kcal/100 g dw), with high share of carbohydrates (65.2 g/100 g dw), followed by proteins (26.47 g/100 g dw) and fat (4.46 g/100 g dw). Free sugar analysis showed presence of fructose, glucose and sucrose (0.77 g, 0.189 g and 3.85 g/100 g dw, respectively). Oxalic and malic acid were quantified <1.0 g/100 g dw and fumaric acid only in trace. Monounsaturated fatty acids were predominant over polyunsaturated and saturated fatty acids (erucic, nervonic and oleic acid were dominant). The content of flavonoid compounds was several times higher than the content of phenolic acids (58.5 vs 9.4 mg/g). Methanolic extract showed better antioxidant potential than dichloromethane extract (EC50 = 0.32 vs. 1.25 mg/mL, in TBARS test). The antibacterial activity ranged from 0.50 to 2.00 mg/mL, with E. coli showing the highest susceptibility to the methanolic extract (MIC: 0.25 mg/mL, MBC: 0.50 mg/mL). The other tested microorganisms showed quite uniform susceptibility to the extracts, but better than the positive controls E211 and E224. The tested samples demonstrated encouraging antifungal/anticandidal properties, and no cytotoxic effects onto spontaneously immortalized keratinocytes cell line HaCaT, indicating its safe application in terms of dermal exposure. Overall, our results indicate that L. annua seeds may be considered as source of compounds used in food and pharmaceutical industry and a candidate for functional ingredient that provides additional health benefits beyond basic nutritional requirements.

Keywords: Honesty plant, Nutritional value, Organic acids, Fatty acids, Phenolic profile, Sugar profile, Bioactive properties

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Lunaria annua seeds demonstrate high energy value.

-

•

L. annua seeds are rich in sucrose and monounsaturated fatty acids.

-

•

The content of flavonoids is higher than of phenolics.

-

•

Extracts exhibit strong antibacterial, antifungal and anticandidal activity.

-

•

Possible application in food and pharmaceutical industry.

1. Introduction

Many plants belonging to the Brassicaceae family are highly valued crops widely consumed across the globe, not only for their distinctive flavors but also for their health beneficial properties, which are associated to their phytochemical composition. Among these compounds, phenolics, isothiocyanates, carotenoids, minerals, and vitamins are most often recognized as bioactive constituents, used to enhance daily requirements for nutrients and biologically active compounds [1]. Given the rising demand for functional food ingredients that provide additional health benefits, there is an increasing interest within the underexplored species of the Brassicaceae family and their potential for larger-scale cultivation and utilization.

Lunaria annua L. (aka honesty or money plant) is one of the most underrated members of Brassicaceae family, even though it offers great potential for industrial-scale cultivation. It grows rapidly widespread across Asia and Europe, thrives with minimal maintenance, and is quite resistant to pathogenic microorganisms [2]. The ability of money plant to self-seed further reduces labor costs, thus enhancing profitability upon cultivation. Given its low maintenance requirements, high abundance of oils in seeds and their versatile application in the food and oil industries, L. annua can be considered a sustainable, underexplored crop that could be efficiently cultivated on abandoned land [3]. Estimates suggest that agricultural abandonment led to creation of 120 million hectares of unused land, especially in remote locations in Europe [4], which presents a significant opportunity for L. annua cultivation given the fact it does not require farmland of the highest quality and offers revenue without directly competing with other crops in the market. Through repurposing of this farmland, we can create opportunities for cultivation of this underutilized species in unfavorable conditions.

This seems to be of particular interest, given that research data on chemical profile and bioactive properties of L. annua are quite scarce. To this date, chemical analyses have shown that seeds contain 30–35 % oil, of which 67 % consists of long-chain fatty acids. The fatty acid profile comprises 44 % erucic acid (C22:1) and 23 % nervonic acid (C24:1), both of which offer various potential applications in the pharmaceutical and oil industries [3]. In addition, the aerial parts of L. annua were found to contain 12 glucosinolates, with glucohesperin, glucoalyssin, glucobrassicanapin, glucoputranjivin, and hex-5-enyl glucosinolate being the most abundant, along with anthocyanins [5,6]. As for the bioactive properties, Katanić Stanković et al. (2022) demonstrated anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities of L. annua herba [2], while Blazevic et al. (2013; 2019) showed cytotoxic potential against lung and breast tumor cell lines [5,6].

Even though seeds are mostly used as a food ingredient, detailed analyses of their nutritional value, chemical profile and bioactive properties are still lacking. Knowing this may reveal whether honesty plant can be considered a sustainable energy source in the diet or a candidate for functional food. This study aimed to chemically characterize the seeds of L. annua, with a focus on their nutritional and energy value, as well as their content of free sugars, organic acids, and fatty acids. We also analyzed phenolic profile, given the well-known bioactive properties of these compounds [7]. Furthermore, we assessed antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, and cytotoxic properties of L. annua as to explore its pharmaceutical potential to provide additional health benefits beyond basic nutritional requirements. This selected metabolite analysis and exploration of honesty plant biological activities could possibly allow prioritization of its cultivation and end-user application in food and pharmaceutical industry, supporting sustainable and economically feasible principles of bio-based industry as well agriculture.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Collection of plant material

Aerial parts of L. annua plants were collected in Mionica, Serbia, in August 2021, when pods (siliques containing seeds) were dried. Authentication was carried out by dr Dejan Stojković at the Institute for Biological Research “Siniša Stanković,” National Institute of the Republic of Serbia, University of Belgrade. A voucher specimen, labeled La-IBRSS-2021, has been deposited in the Plant Collection Unit of the Mycological Laboratory at IBISS. Following collection, the pods were cleaned of the central membrane and debris, ground into a fine powder, and stored at 4 °C for further analysis.

2.2. Preparation of methanolic and dichloromethane extracts

Powdered L. annua seeds (10 g) were extracted by stirring with 250 mL of methanol or dichloromethane at −20 °C overnight, following the method of Vaz et al. [8]. The extraction solvents were selected to investigate potential bioactive compounds across solvents with different polarities. The extract was sonicated for 15 min, centrifuged at 4000 g for 10 min, and filtered through Whatman No. 4 paper. The residue was re-extracted twice with 150 mL portions of methanol or dichloromethane. The combined extracts were evaporated to dryness at 40 °C using a Büchi R-210 rotary evaporator and re-dissolved in 30 % ethanol.

2.3. Standards and reagents

Acetonitrile (99.9 %), n-hexane (95 %), and ethyl acetate (99.8 %) of HPLC grade were sourced from Fisher Scientific (Lisbon, Portugal). Methanol and other analytical-grade chemicals were obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). FAME reference standard mixture (47885-U) and various individual standards for fatty acids, tocopherols, sugars, organic acids, and phenolic compounds were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Additional reagents and media, including Mueller-Hinton agar (MH), malt agar (MA), and cell culture components, were acquired from Torlak Institute (Belgrade, Serbia) and HyClone (Logan, USA). Water was purified using a Milli-Q system (TGI Pure Water Systems, USA).

2.4. Chemical characterization of L. annua

2.4.1. Nutritional value

The seed powder was analyzed for its protein, fat, carbohydrate, and ash content following the procedures outlined by the Association of Official Analytical Chemists [9]. Crude protein content (conversion factor: 6.25) was determined using the macro-Kjeldahl method, which involves digestion, distillation, and titration. Crude fat content was measured by extracting the powdered sample with petroleum ether using a Soxhlet apparatus. Ash content was determined by incinerating the sample at 500 ± 15 °C for 5 h in a muffle furnace. Total carbohydrates were calculated by difference, and energy was estimated using the following equation.

| Energy (kcal) = 4 x (gprotein + gcarbohydrate) + 9 x (gfat). |

2.4.2. Sugars composition

To extract free sugars, mixture of ethanol:water (80:20, 40 mL) solution and Internal Standard (IS, melezitose, 25 mg/mL,1 mL) was added to the powdered seeds (1 g). Using a water bath, extraction was performed for 1 h and 30 min at 80 °C, as described previously by Spréa et al. [10]. Subsequently, ethanol was evaporated, and the obtained aqueous portion was washed successively with 10 mL of ethyl ether (3 x). After concentration at 40 °C, the residue was re-dissolved in distilled water to a final volume of 5 mL and filtered through 0.2 μm nylon filters into vials. The analysis was conducted using a High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) system, which included a pump (Knauer Smartline 1000), a degasser (Smartline Manager 5000), and an auto-sampler (AS-2057 Jasco), coupled with a refractive index detector (Knauer Smartline 2300 RI detector), operating under the same conditions as previously described by the authors [10]. Sugar identification was performed by comparing the relative retention times of sample peaks with those of standards. The resulting data were analyzed using Clarity 2.4 Software (DataApex 1.7 Prague, Czech Republic). Quantification was carried out based on the RI signal response of each standard, using the internal standard (IS, melezitose, 25 mg/mL) method and calibration curves derived from commercial standards of each compound. The results were expressed in grams per 100 g of dry weight (g/100g dw).

2.4.3. Organic acids composition

To evaluate organic acids, 1 g of powdered L. annua seeds was extracted with 25 mL of metaphosphoric acid for 25 min with magnetic stirring at room temperature, then filtered through Whatman No. 4 paper, following the procedure of Barros et al. [11]. The solutions were filtered through 0.2 μm nylon filters into vials and analyzed using an Ultra-Fast Liquid Chromatography system with a reverse phase C18 SphereClone column (Phenomenex, 5 μm, 250 × 4.6 mm), maintained at 35 °C, and coupled to a diode array detector (UFLC-DAD; Shimadzu Coperation, Kyoto, Japan). Quantification of organic acids was performed by comparison of the area of their peaks (at 215 nm) with calibration curves obtained from commercial standards of each compound, including: oxalic, quinic, malic, ascorbic, citric and fumaric acids. All were purchased from SigmaAldrich, St. Louis, USA. Obtained results were analyzed using the LabSolutions Multi LCPDA (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan), and expressed as g per 100 g of dry weight.

2.4.4. Fatty acids composition

Fatty Acid Methyl Esters (FAMEs) were determined from the lipid fraction obtained through Soxhlet extraction. The lipid portion of the sample was derivatized via a transesterification reaction, following the method of Obodai et al. [12]. The procedure consisted of following: addition of a methanol:sulfuric acid:toluene solution (2:1:1, v/v/v, 5 mL) to the lipid fraction previously extracted and incubating for 12 h at 50 °C. After incubation, 3 mL of distilled water and 3 mL of diethyl ether were added to the sample and mixed thoroughly using a vortex. The organic phase (which contained FAMEs) was removed, dehydrated with anhydrous sodium sulfate and filtered with nylon filters (0.2 μm) for chromatographic analysis. Profile of fatty acids was determined using Gas Chromatography (GC) with Flame Ionization Detection (FID), and YOUNG IN Chromass 6500 GC System instrument containing a split/splitless injector. Identification and quantification of fatty acids was made after comparing relative retention times of FAME peaks obtained from samples with those of standards (standard mixture 47885-U, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). Obtained results were recorded and processed using Clarity 4.0.1.7 Software (DataApex, Prague, Czech Republic). They were further expressed as the relative percentage (%) of each fatty acid.

2.4.5. Phenolic compounds composition

Profiles of the phenolic acids in extracts were determined using High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) on a Dionex Ultimate 3000 UPLC (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA) equipped with a Diode Array Detector (DAD), as was previously published [13]. For the separation, we used a Waters Spherisorb S3 ODS-2 C18 column (3 μm, 150 × 4.6 mm, Watersm Milford, MA, USA), operating at 35 °C. For the mobile phase 0.1 % formic acid (A) and acetonitrile (B) were used. The elution gradient was 15 % B (5 min), 15–20 % B (5 min), 20–25 % B (10 min), 25–35 % B (10 min), and 35–50 % B (10 min). Mass detection was carried out using a LTQ Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA), with an ESI electrospray ionization source, with system operating at 325 °C, and a spray voltage of 5 kV with a capillary voltage of −20 V. The spectra were recorded in negative ion mode between 100 and 1500 m/z. Obtained results were further analyzed with Xcalibur® program (version 2.2.0.48; Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, California, USA). The phenolic compounds in the samples were characterized by comparing their UV–vis spectra, mass spectra, and retention times with those of standards and literature sources, when available. For quantitative analysis, a calibration curve was created by injecting known concentrations of various standards, and the compounds were quantified based on the UV–Vis signal of the commercial standards at their λ maximum. When standards were unavailable, other compounds with the same phenolic group were used. The results were expressed in mg per g of extract.

2.5. Antimicrobial activity

2.5.1. Antibacterial activity

Antibacterial activity assay was performed using microdilution method described by Soković et al. [14]. We tested following Gram (+) bacteria: Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 11632), Bacillus cereus (food isolate) and Listeria monocytogenes (NCTC 7973) as well as Gram (−) bacteria Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922), Enterobacter cloacae (ATCC 35030) and Salmonella Typhimurium (ATCC 13311). Bacterial strains were cultured overnight at 37 °C in Tryptic Soy Broth and then adjusted to a concentration of 1.0 × 10⁵ CFU/mL using sterile saline. Samples dissolved in a 30 % ethanol solution were added to Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB, 100 μL) medium with 1.0 × 10⁴ CFU of bacterial inoculum per well. After incubation at 37 °C, 24 h, p-iodonitrotetrazolium chloride (0.2 mg/mL, 40 μL) was added to each well, and the plate was further incubated for 60 min at 37 °C to allow color development. The lowest concentration showing a noticeable reduction in color intensity (light red compared to the intense red in the control well, which had no extract) or no color at all, was defined as the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC). The minimal bactericidal concentration (MBC) was determined by serial sub-cultivation of 2 μL into wells with 100 μL of broth, followed by a further 24-h incubation at 37 °C. The lowest concentration with no visible growth was identified as the MBC, indicating a 99.5 % kill of the original inoculum. Commercial preservatives E211 and E224 served as positive controls.

2.5.2. Antifungal activity

Antifungal assay was performed using a protocol previously described in a study by Petrović et al. (2022) [15]. For antifungal activity assay we used: Aspergillus fumigatus (ATCC 9197), Aspergillus niger (ATCC 6275), Aspergillus versicolor (ATCC 11730), Penicillium funiculosum (ATCC 36839), Penicillium verrucosum var. cyclopium (food isolate), Trichoderma viride (IAM 5061). The microorganisms are deposited at Mycological laboratory, Department of Plant Physiology, Institute for Biological research “Siniša Stanković”, National Institute of Republic of the Serbia, University of Belgrade, Serbia. Before performing microdilution method, fungal spores were washed off the surface of agar plates using sterile 0.85 % saline containing 0.1 % Tween 80 (v/v). Samples dissolved in a 30 % ethanol solution were added to Malt broth medium, which was followed by the addition of the fungal inoculum, and further 5-days incubation at 25 °C. The lowest concentrations showing a significant reduction in mycelial growth (observed under a binocular microscope) were defined as MICs. The minimal fungicidal concentrations (MFC) were determined by serial sub-cultivation of the tested sample dissolved in medium (sample volume 2 μL), followed by further incubation for 72 h at 25 °C. The lowest concentration with no visible growth was identified as the MFC, indicating 99.5 % killing of the original inoculum. Commercial preservatives E211 and E224 were used as positive controls.

2.5.3. Anticandidal activity

For anticandidal assay, following isolates were used: Candida albicans 475/15, C. albicans 13/15, C. albicans 17/15, C. parapsilosis ATCC 22019, C. tropicalis ATCC 750 and C. krusei H1/16. Clinical isolates were obtained from the ENT Clinic, Clinical Hospital Centre Zvezdara, Belgrade, Serbia. Strains of Candida spp. were identified on CHROMagar plates (Biomerieux, France) and maintained on Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (Merck, Germany). Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) and minimum fungicidal concentrations (MFC) were determined using a microdilution method with modifications described by Smiljkovic et al., 2018 [16]. Microplates, containing serially diluted samples, broth, and fungal inoculum, were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The MIC values were determined after incubation as the lowest concentrations showing no visible growth under a microscope. MFC values were determined by serial sub-cultivation of broth (10 μL) with no visible fungal growth into wells containing fresh broth (100 μL), followed by overnight incubation at 37 °C. Ketoconazole (1 μg/mL), a commercial antifungal drug, was used as a positive control.

2.6. Antioxidant activity

2.6.1. TBARS

Inhibition of Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances (TBARS) was performed following the procedure described by Reis et al. (2012) [17]. Porcine (Sus scrofa) brains, obtained from slaughterhouse, were dissected and homogenized using a Polytron in an ice-cold Tris–HCl buffer (20 mM, pH 7.4) to create a 1:2 w/v brain tissue homogenate. The sample was subsequently centrifuged at 3000 g for 10 min and the aliquot of supernatant (100 μL) was incubated with different concentrations of sample solutions (200 μL), FeSO₄ (10 mM, 100 μL) and ascorbic acid (0.1 mM, 100 μL) at 37 °C for an hour. After stopping the reaction with trichloroacetic acid (28 % w/v, 500 μL) the solution of thiobarbituric acid (2 % w/v, 380 μL) was added and the mixture was heated for 20 min at 80 °C. Precipitated protein was removed after centrifuging the sample at 3000 g for 10 min, and the color intensity of the malondialdehyde (MDA)-TBA complex in the supernatant was measured at 532 nm. The inhibition ratio (%) was calculated according to the following: inhibition ratio (%) = [(A - B)/A] × 100 %, where A and B are the absorbance of the control (mixture without extract) and the sample solution, respectively.

2.7. Cytotoxicity towards HaCaT cell line

Crystal violet test was applied to evaluate cytotoxicity towards spontaneously immortalized keratinocytes (HaCaT cell line) as described in a study by Petrović et al. (2021) [18]. HaCaT cells were cultured in an incubator with 5 % CO2 at 37 °C using high-glucose Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), which was supplemented with fetal bovine serum (10 %, FBS), 2 mM l-glutamine, and antibiotic-antimycotic (1 %, Invitrogen). Cells (10⁴) were seeded in a 96-well microtiter plate with an adhesive bottom. After 48 h, the media was removed, and the cells were treated overnight (in triplicate) with varying concentrations of the tested samples. The cells were further washed twice with PBS and then stained with a crystal violet solution (0.4 %) for 20 min. The stain was then removed and the cells were rinsed with tap water and allowed to air dry at room temperature. Methanol was then added to dissolve the bound crystal violet residues. The resulting absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a plate reader (Multiskan™ FC Microplate Photometer, Thermo Scientific). Potassium dichromate (K2Cr2O7) was used as a positive control and PBS as a negative one. The results were expressed as the IC50 (%) value in μg/mL, indicating the concentration required for 50 % cell viability in comparison to the untreated control. The cytotoxic activity of the extracts on the HaCaT cell line was categorized using the following criteria: IC50 ≤ 20 μg/mL = highly cytotoxic, IC50 ranging between 21 and 200 μg/mL = moderately cytotoxic, IC50 ranging between 201 and 400 μg/mL = weakly cytotoxic, and IC50 > 401 μg/mL = no cytotoxicity [19].

2.8. Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate, and the results are presented as mean values with the corresponding standard deviations (SD). The data were analyzed using a Student's t-test to assess the significance of differences between two samples at a 5 % significance level (Version 25, IBM Corp., New York, NY, USA), except for antimicrobial activity.

3. Results and discussion

Until recently, L. annua has primarily been cultivated for its distinctive silique seed pods, commonly used in dried floral arrangements and for home decoration. However, recent studies revealed that this low-maintenance plant also possesses an unusual chemical profile, which has potential applications in various industries. This data offer promising new uses for honesty plant that go far beyond its decorative use. Thus, herein we present a comprehensive nutritional characterization of L. annua seeds, including analyses of free sugars, fatty acids, and a detailed profile of phenolic compounds, along with their associated bioactive properties.

Results regarding selected hydrophilic compounds of L. annua samples are presented in Table 1. They indicate that seeds are valuable source of carbohydrates (65.2 g/100 g dw) followed by proteins (26.47 g/100 g dw) and fat (4.46 g/100 g dw). This is quite important given that seeds are used as a food ingredient, but so far, their nutritional profile has been poorly investigated. Our analysis indicates that seeds are valuable source of macronutrients, which along with other beneficial chemical constituents make them good candidate for functional food. Due to their high carbohydrate content, seeds can serve as an excellent primary source of energy in the diet. Furthermore, since rich source of protein, they are particularly valuable in vegetarian and vegan diets that depend exclusively on plant-based protein sources. Total fat content in the sample is generally considered low, but the high abundance of beneficial fatty acids makes the seeds desirable in specialized diets with limited lipid intake.

Table 1.

Nutritional, energetic value and hydrophilic compounds of Lunaria annua seeds (mean ± SD, n = 3).

| Nutritional value | (g/100g dw) | Student t-Test |

|---|---|---|

| Fat | 4.46 ± 0.06 | <0.001 |

| Proteins | 26.47 ± 0.04 | <0.001 |

| Ash | 3.9 ± 0.1 | <0.001 |

| Carbohydrates | 65.2 ± 0.1 | <0.001 |

| Energy (Kcal/100g dw) | 406.6 ± 0.1 | <0.001 |

| Free sugars | (g/100g dw) | |

| Fructose | 0.77 ± 0.07 | <0.001 |

| Glucose | 0.189 ± 0.001 | <0.001 |

| Sucrose | 3.85 ± 0.03 | <0.001 |

| Total | 4.8 ± 0.1 | <0.001 |

| Organic acids | (g/100g dw) | |

| Oxalic acid | 0.23 ± 0.01 | <0.001 |

| Malic acid | 0.48 ± 0.03 | <0.001 |

| Fumaric acid | trace | <0.001 |

| Total | 0.70 ± 0.03 | <0.001 |

Mean statistical differences obtained by t-Student test.

Regarding free sugar analysis, disaccharide sucrose was present in highest amount 3.85 g/100 g dw. While this amount is not particularly high, one should be cautious upon consummation of L. annua, as elevated sucrose intake has been linked with a higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes and elevated plasma triglyceride levels [20]. As for the organic acid profile, our results revealed low share of oxalic and malic acid (<1.00 g/100 g dw), with traces of fumaric acid. Even though organic acids have been connected to various health benefits [21], their low concentration in L. annua does not diminish the potential health benefits provided by other bioactive compounds present in the plant. The results of fatty acid analysis are presented in Table 2. They show a higher prevalence of monounsaturated fatty acids compared to polyunsaturated and saturated fatty acids, with erucic (C22:1n9), nervonic (C24:1) and oleic (C18:1n9c) being the most prevalent fatty acids found in the seeds of the honesty plant: 38.10 %, 26.73 % and 21.12 %, respectively. Their high content is significant, as plant-based foods are preferred sources of MUFAs for preventing coronary heart disease [[22], [23]]. Previously published data indicated that honesty plant has been explored as source of oils used as lubricants in industry, due to relatively high oil yield from seeds. From 1000 to 2000 kg/ha, oil yield from seeds was ∼30–35 %, with nervonic (C24:1) and erucic acid (C22:1) as the main constituents (23 % and 44 % respectively) [23,24]. Results on MUFA abundance align with our results; however, additional research is necessary to fully elucidate potential of these fatty acids in pharmaceutical industry. So far, research showed that high abundance of nervonic acid in the L. annua seeds has re-myelinating properties, which may be significant in treating neurological disorders accompanied with loss of myelin [25]. As for the erucic acid, even though data suggest it has adverse effects in experimental animals [26], they lack confirmation in humans. Furthermore, people who consume food rich in this compound had no signs of intoxication. Thus, the use of L. annua seeds in cuisine as a substitute for mustard consistently showed no toxic effects on humans.

Table 2.

Fatty acids profile of the Lunaria annua seeds (mean ± SD, n = 3).

| Fatty acids | Relative percentage (%) | Student t-Test |

|---|---|---|

| C14:0 | 0.124 ± 0.003 | <0.001 |

| C15:0 | 0.109 ± 0.002 | <0.001 |

| C16:0 | 3.12 ± 0.01 | <0.001 |

| C16:1 | 0.220 ± 0.001 | <0.001 |

| C18:0 | 0.79 ± 0.01 | <0.001 |

| C18:1n9c | 21.12 ± 0.04 | <0.001 |

| C18:2n6c | 6.3 ± 0.09 | <0.001 |

| C18:3n3 | 0.721 ± 0.06 | <0.001 |

| C20:1 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | <0.001 |

| C20:5n3 | 0.108 ± 0.001 | <0.001 |

| C22:0 | 0.434 ± 0.001 | <0.001 |

| C22:1n9 | 38.10 ± 0.07 | <0.001 |

| C22:2 | 0.183 ± 0.001 | <0.001 |

| C24:0 | 0.393 ± 0.001 | <0.001 |

| C24:1 | 26.73 ± 0.05 | <0.001 |

| SFA | 4.97 ± 0.02 | <0.001 |

| MUFA | 87.76 ± 0.05 | <0.001 |

| PUFA | 7.27 ± 0.03 | <0.001 |

C14:0 - Myristic acid, C15:0 - Pentadecanoic acid, C16:0 - Palmitic acid, C16:1 - Palmitoleic acid, C18:0 - Stearic acid, C18:1n9c - Oleic acid, C18:2n6c - Linoleic acid, C18:3n3 - α-Linolenic acid, C20:1 - Eicosenoic acid, C20:5n3 - Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), C22:0 - Behenic acid, C22:1n9 - Erucic acid, C22:2 - Docosadienoic acid, C24:0 - Lignoceric acid, C24:1 - Nervonic acid, SFA - saturated fatty acids, MUFA - monounsaturated fatty acids, PUFA - polyunsaturated fatty acids. Mean statistical differences obtained by t-Student test.

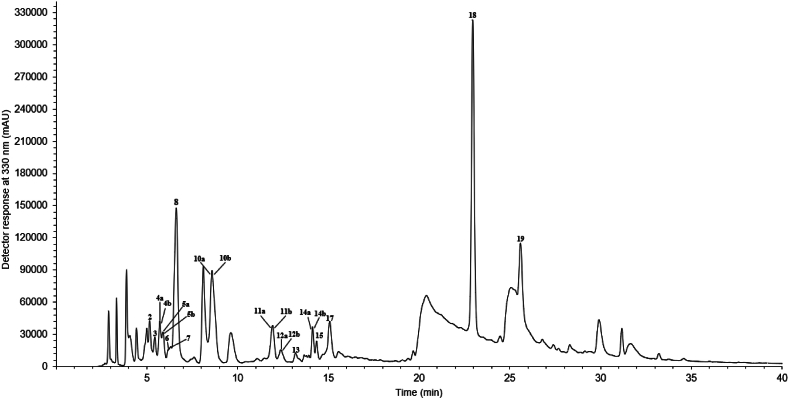

Results of the phenolic compounds profile by LC-DAD-ESI-MSn are presented in Table 3. The phenolic compounds were detected in methanolic extract (Fig. 1, Fig. 2), whereas dichloromethane extract showed no traces of phenolic compounds. The variation in profiles of phenolic compounds in the examined extracts can be attributed to the differing polarities of the solvents used in the extraction. Organic solvents with higher polarity, such as methanol, are more effective at extracting more polar compounds, resulting in the extraction of higher content of phenolic compounds (polar compounds) than dichloromethane, a solvent with lower polarity [27]. Results presented in Table 3 show the compounds identified in sample based on their chromatographic behavior, UV–Vis data, and comparison of fragmentation patterns with those previously reported in the literature. The MS2 spectral data for each compound are presented in the Supplementary Material of this article.

Table 3.

Phenolic composition of L. annua seeds oil extracts (mean ± SD).

| Peak n.° | Rt (min) | λmax (nm) | [M − H] (m/z) | MS2 fragments (m/z) | Tentative identification |

L. annua (MeOH) (mg/g of extract) |

Student t-Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4.97 | 285 | 465 | MS2 [465]: 285 (100), 125 (33), 177 (14), 303 (14) | Taxifolin hexoside [[28], [29], [30], [31]] | 2.73 ± 0.08 | <0.001 |

| 2 | 5.15 | 267/327 | 787 | MS2 [369]: 463 (100), 301 (98), 179 (44), 151 (37), 625 (3) | Quercetin trihexoside [63,64] | 1.4 ± 0.07 | <0.001 |

| 3 | 5.43 | 271/312 | 1095 | MS2 [1095]: 463 (100), 301 (58), 609 (31), 771 (18), 625 (13), 179 (1) | Quercetin tetrahexoside-rhamnoside [36] | 0.85 ± 0.02 | <0.001 |

| 4aa | 5.71 | 272/319 | 369 | MS2 [369]: 249 (100), 189 (80), 145 (76), 369 (75), 207 (72), 163 (56), 119 (50), 223 (35) | p-Coumaric acid derivative [56] | 0.4 ± 0.03 | <0.001 |

| 4ba | 5.71 | 272/319 | 325 | MS2 [325]: 145 (100), 163 (7), 161 (2), 119 (1) | p-Coumaric acid glucoside [[53], [54], [55]] | 0.4 ± 0.03 | <0.001 |

| 5aa | 5.87 | 273/315 | 1125 | MS2 [1125]: 463 (100), 301 (69), 639 (21), 625 (17), 801 (6), 477 (1) | Quercetin tetrahexoside-glucoronide | 1.09 ± 0.05 | <0.001 |

| 5ba | 5.87 | 273/315 | 1155 | MS2 [1155]: 463 (100), 301 (67), 625 (21), 669 (17), 831 (4), 151 (1) | Quercetin derivative | 1.09 ± 0.05 | <0.001 |

| 6 | 6.15 | 271/302 | 1139 | MS2 [1139]: 815 (100), 653 (69), 301 (43), 463 (42), 977 (18), 695 (15), 625 (5) | Quercetin trihexoside-diglucoronide | 1.16 ± 0.06 | <0.001 |

| 7 | 6.53 | 267/304 | 917 | MS2 [917]: 300 (100), 301 (14), 917 (51), 179 (5), 771 (1) | Quercetin p-coumaroyl-rutinoside-hexoside [[33], [34], [35]] | 7.2 ± 0.2 | <0.001 |

| 8 | 6.63 | 231/304 | 369 | MS2 [369]: 189 (100), 207 (59), 145 (59), 369 (41), 163 (15), 119 (11) | p-Coumaric acid derivative [56] | 2.59 ± 0.06 | <0.001 |

| 9aa | 8.27 | 289 | 475 | MS2 [475]: 167 (100), 135 (69), 125 (51), 443 (16), 247 (7), 143 (7) | Vanillic acid rutinoside [51,52] | 5.71 ± 0.01 | <0.001 |

| 9ba | 8.27 | 289 | 521 | MS2 [521]: 167 (100), 125 (62), 443 (40), 135 (39), 247 (20), 143 (12) | Vanillic acid derivative | 5.71 ± 0.01 | <0.001 |

| 10aa | 8.59 | 265/352 | 755 | MS2 [755]: 300 (100), 901 (75), 755 (19), 301 (10), 609 (1) | Quercetin rutinoside-rhamnoside [[37], [38], [39]] | 8.2 ± 0.5 | <0.001 |

| 10ba | 8.59 | 265/352 | 901 | MS2 [901]: 284 (100), 285 (25), 737 (7), 179 (6), 755 (2), 593 (1) | Kaempferol dirutinoside [45,46] | 8.2 ± 0.5 | <0.001 |

| 11aa | 11.94 | 264/356 | 463 | MS2 [463]: 301 (100), 463 (36), 151 (10), 179 (5), 341 (5), 300 (6) | Quercetin hexoside [31,[40], [41], [42]] | 2.7 ± 0.1 | <0.001 |

| 11ba | 11.94 | 264/356 | 739 | MS2 [739]: 284 (100), 739 (24), 285 (18), 575 (4), 179 (3), 593 (1) | Kaempferol rutinoside-rhamnoside [38,47] | 2.7 ± 0.1 | <0.001 |

| 12aa | 12.35 | 268/344 | 769 | MS2 [639]: 314 (100), 315 (19), 769 (22), 299 (10) | Isorhamnetin rutinoside-rhamnoside [48,49] | 1.06 ± 0.03 | <0.001 |

| 12ba | 12.35 | 268/344 | 1099 | MS2 [1099]: 463 (100), 625 (25), 301 (43), 567 (7), 300 (2) | Quercetin derivative | 1.06 ± 0.03 | <0.001 |

| 13 | 13.19 | 259/351 | 609 | MS2 [609]: 300 (100), 301 (54), 609 (29) | Quercetin rutinoside (Rutin) (Std) | 0.78 ± 0.01 | <0.001 |

| 14aa | 14.11 | 273/321 | 1361 | MS2 [1361]: 301 (100), 463 (75), 669 (65), 625 (16), 831 (6), 300 (6), 1037 (2) | Quercetin derivative | 1.4 ± 0.1 | <0.001 |

| 14ba | 14.11 | 273/321 | 755 | MS2 [755]: 285 (100), 755 (25), 284 (24), 593 (1) | Kaempferol rutinoside-hexoside [50 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | <0.001 |

| 15 | 14.33 | 274/319 | 463 | MS2 [463]: 300 (100), 301 (27), 463 (1) | Quercetin-3-O-glucoside (Std) | 0.65 ± 0.01 | <0.001 |

| 16 | 14.83 | 300 | 303 | MS2 [303]: 125 (100), 285 (45), 177 (16) | Taxifolin (Std) | 1.00 ± 0.02 | <0.001 |

| 17 | 15.08 | 298 | 207 | MS2 [207]: 119 (100), 207 (16), 163 (10) | p-Coumaric acid derivative | 0.7 ± 0.1 | <0.001 |

| 18 | 22.95 | 264/314 | 901 | MS2 [901]: 300 (100), 301 (12), 755 (45), 179 (4), 609 (1) | Quercetin dirhamnoside-rutinoside [43] | 14.4 ± 0.6 | <0.001 |

| 19 | 25.59 | 315 | 885 | MS2 [885]: 284 (100), 739 (69), 285 (21), 575 (6), 179 (3), 593 (2) | Kaempferol dirhamnoside-rutinoside [43,50] | 8.0 ± 0.4 | <0.001 |

| Total phenolic acids | 9.4 ± 0.1 | <0.001 | |||||

| Total flavonoids | 58.5 ± 1 | <0.001 | |||||

| Total phenolic compounds | 68 ± 1 | <0.001 | |||||

– Correspond to coeluted compounds in the peak of the same number; Std – Standard; Mean statistical differences obtained by t-Student test.

Fig. 1.

Chromatogram of phenolic compounds present in the methanolic extract of L. annua seeds at 280 nm. Information regarding peak numbers and respective compounds is presented in Table 3.

Fig. 2.

Chromatogram of phenolic compounds present in the methanolic extract of L. annua seeds at 330 nm. Information regarding peak numbers and respective compounds is presented in Table 3.

Twenty-six compounds were determined in the methanolic extract. Flavonoids were the compounds found in the greatest amount (total of 58.5 mg/g of extract). The total phenolic acids content was 9.4 mg/g of extract, with vanillic acid rutinoside and a vanillic acid derivative being the most representative compounds (5.71 mg/g of extract each, coeluted in the same peak). Peak 1 was assigned as taxifolin hexoside (λmax = 285 nm; [M − H]‾ m/z 465) due to the neutral loss of 162 Da (indicating the loss of a hexose moiety) that yielded m/z 303 as the aglycone ([M-H-162]‾), and the characteristic fragments at m/z 285 ([M-H-162-18]‾), m/z 177 and m/z 125, both corresponding to the ring fission of taxifolin [[28], [29], [30]]. Taxifolin (peak 16; λmax = 300 nm; [M − H]‾at m/z 303) was confirmed using authentic standards.

Thirteen compounds were tentatively identified as quercetin derivatives. Among them, quercetin-3-O-rutinoside (Rutin) (peak 13; λmax = 259/351 nm; [M − H]‾ at m/z 609), and quercetin-3-O-glucoside (peak 15; λmax = 274/319 nm; [M − H]‾ at m/z 463), were identified by comparison with an authentic standard. Quercetin-O-glycosides were characterized by the presence of the aglycone at m/z 301 as main fragment ion, which was attributed to quercetin [31,32]. In addition, they had fragmentation patterns that indicated the presence of sugar moieties linked to the aglycone due to the neutral losses of 146 Da, 162 Da, 324 Da (162 Da +162 Da), 308 Da (162 Da +146 Da) and 176 Da, ascribed as rhamnose, hexose, dihexoses, rutinoses and glucoronide moieties, respectively [31,[33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43]]. The presence of rutinose group was inferred, as molecules containing this sugar typically exhibit a less fragmented mass spectrum compared to those of neohesperidose [27,32,44]. Rhamnose was tentatively assigned as the deoxyhexose group in the molecules due to its abundance in nature [44]. Therefore, these peaks were assigned as quercetin trihexoside (Peak 2; λmax = 267/327 nm; [M − H]‾ m/z 787), quercetin tetrahexoside-rhamnoside (peak 3; λmax = 271/312 nm; [M − H]‾ m/z 1095), quercetin tetrahexoside-glucoronide (peak 5a; λmax = 273/315 nm; [M − H]‾ m/z 1125), quercetin derivative (peak 5b; λmax = 273/315 nm; [M − H]‾ m/z 1155), quercetin trihexoside-diglucoronide (peak 6; λmax = 271/302 nm; [M − H]‾ m/z 1139), quercetin rutinoside-rhamnoside (peak 10a; λmax = 265/352 nm; [M − H]‾ m/z 755), quercetin hexoside (Peak 11a; λmax = 264/356 nm; [M − H]‾ m/z 463), quercetin derivative (peak 12b; λmax = 268/344 nm; [M − H]‾ m/z 1099), quercetin derivative (peak 14a; λmax = 273/321 nm; [M − H]‾ m/z 1361) and quercetin dirhamnoside-rutinoside (peak 18; λmax = 264/314 nm; [M − H]‾ m/z 901) [18,[24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31],33,34]. Peak 7 (λmax = 267/304 nm; [M − H]‾ m/z 917) gave deprotonated molecule at m/z 917 and fragment ions at m/z 300, 301 and 771, and was tentatively designated as quercetin p-coumaroyl-rutinoside-hexoside [[33], [34], [35]].

Four kaempferol derivatives were tentatively identified due to the presence of the aglycone ions at m/z 285 and 284, and the characteristic losses of sugar moieties (162 Da, 146 Da and 308 Da). The compounds were assigned as kaempferol dirutinoside (peak 10b; λmax = 265/352 nm); deprotonated ion at m/z 901 and diagnostic fragments at m/z 593 and 285 [M-H-308-308]‾), kaempferol rutinoside-rhamnoside (peak 11b; λmax = 264/356 nm; with [M − H]‾ at m/z 739 and main fragment at m/z 285 [M-H-308-146]‾), kaempferol rutinoside-hexoside (peak 14b; λmax = 273/321 nm; molecular ion at m/z 755 giving ion fragment at m/z 285 ([M-H-308-162]‾), and kaempferol dirhamnoside-rutinoside (peak 19; λmax = 268/315 nm) showing deprotonated molecule at m/z 885 and main fragment at m/z 284 and 285 ([M-H-146-146-308]‾) [38,[45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50]].

Compound 12a showed fragment molecular ion at m/z 769 and m/z 314, 315 and 299 as main fragment ions, representing the aglycone isorhamnetin after the loss of 454 Da due to the cleavage of a rutinoside (308 Da) and a rhamnoside (146 Da) [48,49]. Hence, peak 12a was named as isorhamnetin rhamnoside-rutinoside (λmax = 268/344 nm). Compounds 9a (λmax = 289 nm; [M − H]‾ m/z 475) and 9b (λmax = 289 nm; [M − H]‾ m/z 521) were tentatively identified as vanillic acid rutinoside and vanillic acid derivative, respectively, due to the presence of the main fragment at m/z 167 (vanillic acid), indicating the loss of a rutinoside moeity (308 Da), in addition to other characteristic fragments such as m/z 125, 443, and 135 [51,52]. Derivatives of p-coumaric acid were also observed, showing typical aglycone ion at m/z 163, and characteristic fragments such as at m/z 145 and 119, being assigned as p-coumaric acid derivative (peak 4a; λmax = 272/319 nm; [M − H]‾ m/z 369), p-coumaric acid glucoside (peak 4b; λmax = 272/319 nm; [M − H]‾ m/z 325), p-coumaric acid derivative (peak 8; λmax = 231/304 nm; [M − H]‾ m/z 369), p-coumaric acid derivative (peak 17; λmax = 298/369 nm; [M − H]‾ m/z 207) [[53], [54], [55], [56]].

Both tested extracts displayed good antimicrobial activity towards tested microorganisms (Table 4). Among bacteria, E. coli showed the highest susceptibility to dichloromethane and methanolic extracts activity (MIC 0.25 mg/mL, MBC 0.50 mg/mL), whereas rest of the tested bacteria showed quite uniform susceptibility to the tested extracts. In comparison with positive controls E211 and E244, extracts displayed comparable or better activity which may be of importance in the food technology sector. The observed pattern of antibacterial values also refers to our antifungal results, since MIC value for fungi ranged from 0.50 to 1.00 mg/mL, whereas range of MFC values was in 1.00–2.00 mg/mL. Tested Candida spp. showed approximately the same sensitivity to the tested samples.

Table 4.

Antimicrobial activity of L. annua extracts (mg/mL).

| Antibacterial activity | S. aureus (ATCC 11632) | B. cereus (clinical isolate) | L.monocytogenes (NCTC 7973) | S.Typhimurium (ATCC 13311) | E. coli (ATCC 5922) | E. cloacae (ATCC 35030) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dichloromethane extract | MIC | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 |

| MBC | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | |

| Methanol extract | MIC | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.25 | 1.00 |

| MBC | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 2.00 | |

| E211 | MIC | 4.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 |

| MBC | 4.00 | 0.50 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 4.00 | |

| E224 | MIC | 1.00 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| MBC | 1.00 | 4.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.50 |

| A.fumigatus (ATCC 9197) | A.versicolor (ATCC 11730) | A.ochracues (ATCC 6275) | P.funiculosum (ATCC 36839) | P.verrucosum var. cyclopium (food isolate) | T.viride (IAM 5061) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dichloromethane extract | MIC | 0.50 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.50 |

| MFC | 1.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | |

| Methanol extract | MIC | 1.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 |

| MFC | 2.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | |

| E211 | MIC | 1.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 |

| MFC | 2.00 | 4.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 2.00 | |

| E224 | MIC | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.50 |

| MFC | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.50 |

| C. albicans 475/15 |

C. albicans 13/15 |

C. albicans 17/15 | C. parapsilosis ATCC 22019 | C. tropicalis ATCC 750 |

C. krusei H1/16 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dichloromethane extract | MIC | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.50 |

| MFC | 1.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | |

| Methanol extract | MIC | 1.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 |

| MFC | 2.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | |

| Ketoconazole (x 10−3) | MIC | 3.20 | 1.60 | 1.60 | 3.20 | 1.60 | 1.60 |

| MFC | 6.40 | 51.20 | 51.20 | 6.40 | 6.40 | 3.20 |

Strong antimicrobial potential observed in tested samples can be attributed to the presence of both phenolic compounds and fatty acids in our extracts, given that Khadke et al. [57] previously showed that fatty acids may be responsible for this type of activity. Thus, erucic acid showed antibacterial activity towards some Borrelia species [58], while oleic and nervonic acid (all abundantly present in seeds of L. annua) showed effects on biofilm formation in MDR Acinetobacter baumanii. Along with fatty acids, various phenolic compounds (identified in our extract) were associated with antimicrobial activity as well, i.e. flavonoids emerged as effective antimicrobial agents, with structural modifications influencing their efficacy [59]. Furthermore, synergistic interactions of phenolic compounds with antibiotics enhanced their overall antimicrobial potential, highlighting their potential in development of effective therapeutic strategies towards antibiotic-resistant pathogens [60]. Future research should include investigation of underlying mechanisms of action, as to choose wisely the most suitable candidates for development of antimicrobial drugs [61].

Results of TBARS assay are presented in Table 5. They demonstrate better antioxidant activity for methanol extract than dichloromethane: EC50 = 0.32 mg/mL and 1.25 mg/mL, in that order. Even so, results were ∼100 fold lower than we obtained for the positive control Trolox (0.0054 mg/mL). Previously published data suggested that aerial parts and roots of L. annua have antioxidant properties as well. For aerial parts total antioxidant activity was 215.56 mg AAE/g, DPPH activity was 578.9 μg/mL, ABTS+ was 648.3 μg/mL, while inhibition of lipid peroxidation was 558.3 μg/mL [2]. Roots of L. annua showed app. twice the value of aerial parts: total antioxidant activity 110.07 μg/mL, DPPH activity was 1294.1 μg/mL, ABTS+ was 1072.5 μg/mL, and inhibition of lipid peroxidation 342.7 μg/mL [2]. We tested lipid peroxidation using TBARS assay and found better activity in case of methanolic extract (0.32 mg/mL) than the one demonstrated by Katanić Stanković et al. (2022) [2]. Better results obtained with methanolic extract than with dichloromethane can be explained with higher polarity of methanol, and consequently extraction of phenolic compounds responsible for the antioxidant potential, which we also demonstrated by analysing the phenolic compounds.

Table 5.

Antioxidant activity of L. annua seeds oil extracts (mean ± SD).

| TBARS (IC50, mg/mL) | Student t-Test | |

|---|---|---|

| Dichloromethane | 1.25 ± 0.02 | <0.001 |

| Methanol | 0.32 ± 0.01 | <0.001 |

| Trolox | 0.0054 ± 0.0003 | <0.001 |

Mean statistical differences obtained by t-Student test.

Cytotoxic activity results of L. annua extracts are presented in Table 6. They suggest that the tested extracts have no cytotoxic effect on spontaneously immortalized HaCaT cell line (IC50 > 400 μg/mL).

Table 6.

Cytotoxic activity of L. annua seeds oil extracts (mean ± SD).

| L. annua extracts | IC50 value |

|---|---|

| Dichloromethane | >400 μg/mL |

| Methanol | >400 μg/mL |

| K2Cr2O7 | 83.40 μg/mL |

Based on results regarding bioactive potential of L. annua, we can conclude that this plant exhibits great versatility and may have applications in both food and pharmaceutical industries, providing natural solutions for a variety of purposes. Thus, results we obtained in antioxidant assay regarding lipid peroxidation as well as those demonstrating antimicrobial potential towards food borne pathogens, suggest that L. annua has the potential to enhance safety of food ingredients, address public concerns related to spoilage and rancidity, and decrease use of synthetic preservatives [62].

Moreover, given the results of antibacterial activity observed towards human pathogens that cause skin infections, we further showed that L. annua has no toxic effects on HaCaT cells, suggesting potential application of L. annua extracts in development of skincare products.

4. Conclusion

This study investigated the untapped potential of L. annua, an understudied yet versatile species with a range of applications in agriculture, ecology and medicine. Despite its prominence as an ornamental plant L. annua, could offer significant benefits as a sustainable crop, contributing to agricultural diversification, soil health, and pollinator support. Its edible parts and potential medicinal properties further enhance its appeal. This research uncovered new insights into its versatile applications, while also highlighting its connection to sustainable farming practices, ultimately aiming to promote its integration into modern agricultural systems. The results suggest L. annua has a favorable nutritional/chemical profile, with significant antioxidant and antibacterial potential while displaying no cytotoxic effects. These features highlight its potential to be regarded as functional food and expand its possible applications in both food and pharmaceutical industries. Furthermore, given the low cultivation requirements and possibility to grow it on abandoned farmlands, our primary goal is to establish Lunaria annua as a cultivated crop which will allow extensive use of this underutilized plant, ensuring a sustainable and consistent supply of its bioactive compounds, thus facilitating the cosmopolitan use of this versatile plant.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jovana Petrović: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Daiana Almeida: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Ângela Fernandes: Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Dejan Stojković: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Conceptualization. Dragana Robajac: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Data curation. Tayse F.F. da Silveira: Methodology, Formal analysis. Lillian Barros: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, [J.P.].

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Corresponding author Dejan Stojković serves as Associate Editor of the journal Heliyon. If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

This study has been supported by the Serbian Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation [Contract No. 451-03-66/2024-03/200007 and 451-03-66/2024-03/200019] as well as FCT/MCTES (PIDDAC): CIMO, UIDB/00690/2020 (DOI: 10.54499/UIDB/00690/2020) and UIDP/00690/2020 (DOI: 10.54499/UIDP/00690/2020); and SusTEC, LA/P/0007/2020 (DOI: 10.54499/LA/P/0007/2020); and national funding by FCT, P.I., through the institutional and individual scientific employment program contract for L. Barros and A. Fernandes contracts.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2025.e42248.

Contributor Information

Jovana Petrović, Email: jovana0303@ibiss.bg.ac.rs.

Dejan Stojković, Email: dejanbio@ibiss.bg.ac.rs.

Appendix ASupplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Ramirez D., Abellán-Victorio A., Beretta V., Camargo A., Moreno D.A. Functional ingredients from Brassicaceae species: overview and perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21(6):1998. doi: 10.3390/ijms21061998. 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katanić Stanković J.S., Nikles S., Pan S.P., Matić S.L., Srećković N., Mihailović V., Bauer R. The qualitative composition and comparative biological potential of Lunaria Annua L. (Brassicaceae) extracts. Kragujevac J. Sci. 2022;44:75–89. doi: 10.5937/KgJSci2244075K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mastebroek H.D., Marvin H.J.P. Breeding prospects of Lunaria annua L. Ind. Crops Prod. 2000;11:139–143. doi: 10.1016/S0926-6690(99)00056-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zavalloni M., D'Alberto R., Raggi M., Viaggi D. Farmland abandonment, public goods and the CAP in a marginal area of Italy. Land Use Pol. 2021;107 doi: 10.1016/J.LANDUSEPOL.2019.104365. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blazevic I., Males T., Ruscic M. Glucosinolates of Lunaria annua: thermal, enzymatic, and chemical degradation. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2014;49:1154–1157. doi: 10.1007/S10600-014-0847-6/TABLES/2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blažević I., Đulović A., Čikeš Čulić V., Popović M., Guillot X., Burčul F., Rollin P. Microwave-assisted versus conventional isolation of glucosinolate degradation products from Lunaria annua L. And their cytotoxic activity. Biomolecules. 2020;10(2):215. doi: 10.3390/biom10020215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rahman M.M., Rahaman M.S., Islam M.R., Rahman F., Mithi F.M., Alqahtani T., Almikhlafi M.A., Alghamdi S.Q., Alruwaili A.S., Hossain M.S. Role of phenolic compounds in human disease: current knowledge and future prospects. Molecules. 2022;27:233. doi: 10.3390/molecules27010233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaz J.A., Heleno S.A., Martins A., Almeida G.M., Vasconcelos M.H., Ferreira I.C.F.R. Wild mushrooms clitocybe alexandri and lepista inversa: in vitro antioxidant activity and growth inhibition of human tumour cell lines. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2010;48:2881–2884. doi: 10.1016/J.FCT.2010.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Latimer G., editor. AOAC Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International. 2016. ISBN 0-935584-87-0. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spréa R.M., Fernandes Â., Calhelha R.C., Pereira C., Pires T.C.S.P., Alves M.J., Canan C., Barros L., Amaral J.S., Ferreira I.C.F.R. Chemical and bioactive characterization of the aromatic plant levisticum officinale W.D.J. Koch: a comprehensive study. Food Funct. 2020;11:1292–1303. doi: 10.1039/C9FO02841B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barros L., Pereira C., Ferreira I.C.F.R. Optimized analysis of organic acids in edible mushrooms from Portugal by ultra-fast Liquid Chromatography and photodiode array detection. Food Anal. Methods. 2013;6:309–316. doi: 10.1007/S12161-012-9443-1/TABLES/4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Obodai M., Narh Mensah D., Fernandes Â., Kortei N., Dzomeku M., Teegarden M., Schwartz S., Barros L., Prempeh J., Takli R. Chemical characterization and antioxidant potential of wild ganoderma species from Ghana. Molecules. 2017;22:196. doi: 10.3390/molecules22020196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bessada S.M.F., Barreira J.C.M., Barros L., Ferreira I.C.F.R., Oliveira M.B.P.P. Phenolic profile and antioxidant activity of Coleostephus Myconis (L.) Ch.B.: an underexploited and highly disseminated species. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016;89:45–51. doi: 10.1016/J.INDCROP.2016.04.065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soković M., Glamočlija J., Marin P.D., Brkić D., Griensven L.J.L.D. Antibacterial effects of the essential oils of commonly consumed medicinal herbs using an in vitro model. Molecules. 2010;15:7532–7546. doi: 10.3390/molecules15117532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petrović J., Fernandes Â., Stojković D., Soković M., Barros L., Ferreira I.C.F.R., Shekhar A., Glamočlija J. A step forward towards exploring nutritional and biological potential of mushrooms: a case study of Calocybe gambosa (Fr.) donk wild growing in Serbia, Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2022;72(1):17–26. doi: 10.31883/pjfns/144836. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smiljkovic M., Matsoukas M.T., Kritsi E. Nitrate esters of heteroaromatic compounds as novel Candida albicans CYP51 enzyme inhibitors. ChemMedChem. 2018;13:251–258. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.20170060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reis F.S., Martins A., Barros L., Ferreira I.C.F.R. Antioxidant properties and phenolic profile of the most widely appreciated cultivated mushrooms: a comparative study between in vivo and in vitro samples. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012;50:1201–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petrovic J., Kovalenko V., Svirid A., Stojković D., Ivanov M., Kostic M. Individual stereoisomers of verbenol and verbenone express bioactive features. J. Mol. Struct. 2021;1251 doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.131999. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geran R.I., Greenberg N.H., Macdonald M.M., Schumacher A.M. Protocols for screening chemical agents and natural products against animal tumors and other biological systems. Cancer Chemother. Rep. 1972;3:59–61. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amin K., Safwat G., Srirajaskanthan R. In: Dietary Sugars: Chemistry. Preedy Victor R., editor. Royal Society of Chemistry; 2012. High sucrose diet and antioxidant defense; pp. 770–787. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi Y., Pu D., Zhou X., Zhang Y. Recent progress in the study of taste characteristics and the nutrition and health properties of organic acids in foods. Foods. 2022;11:3408. doi: 10.3390/foods11213408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zong G., Li Y., Sampson L., Dougherty L.W., Willett W.C., Wanders A.J., Alssema M., Zock P.L., Hu F.B., Sun Q. Monounsaturated fats from plant and animal sources in relation to risk of coronary heart disease among US men and women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018;107(3):445–453. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqx004. 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mukherjee D., Kiewitt I. Lipids containing very long chain monounsaturated acyl moieties in seeds of Lunaria annua. Phytochem. 1986;25:401–404. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)85488-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walker R.L., Walker K.C., Booth E.J. Adaptation potential of the novel oilseed crop, honesty (Lunaria annua L.), to the scottish climate. Ind. Crops Prod. 2003;18:7–15. doi: 10.1016/S0926-6690(03)00014-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goyal A., Dubey N., Verma A., Agrawal A. Erucic acid: a possible therapeutic agent for neurodegenerative diseases. Curr. Mol. Med. 2024;24:419–427. doi: 10.2174/1566524023666230509123536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galanty A., Grudzińska M., Paździora W., Paśko P. Erucic acid—both sides of the story: a concise review on its beneficial and toxic properties. Molecules. 2023;28:1924. doi: 10.3390/MOLECULES28041924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cuyckens F., Claeys M. Mass spectrometry in the structural analysis of flavonoids. J. Mass Spectrom. 2004;39:1–15. doi: 10.1002/JMS.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hashim S.N.N.S., Schwarz L.J., Boysen R.I., Yang Y., Danylec B., Hearn M.T.W. Rapid solid-phase extraction and analysis of resveratrol and other polyphenols in red wine. J. Chromatogr., A. 2013;1313:284–290. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2013.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patyra A., Dudek M.K., Kiss A.K. LC-DAD–ESI-MS/MS and NMR analysis of conifer wood specialized metabolites. Cells. 2022;11:3332. doi: 10.3390/cells11203332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spínola V., Llorent-Martínez E.J., Gouveia-Figueira S., Castilho P.C. Ulex europaeus: from noxious weed to source of valuable isoflavones and flavanones. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016;90:9–27. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2016.06.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vukics V., Guttman A. Structural characterization of flavonoid glycosides by multi‐stage mass spectrometry. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2010;29:1–16. doi: 10.1002/mas.20212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rojas-Garbanzo C., Winter J., Montero M.L., Zimmermann B.F., Schieber A. Characterization of phytochemicals in Costa Rican guava (Psidium friedrichsthalianum -nied.) fruit and stability of main compounds during juice processing - (U)HPLC-DAD-ESI-TQD-MSn. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2019;75:26–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2018.09.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dou J., Lee V.S.Y., Tzen J.T.C., Lee M.R. Identification and comparison of phenolic compounds in the preparation of oolong tea manufactured by semifermentation and drying processes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007;55:7462–7468. doi: 10.1021/JF0718603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simirgiotis M.J., Caligari P.D.S., Schmeda-Hirschmann G. Identification of phenolic compounds from the fruits of the mountain papaya vasconcellea pubescens A. DC. Grown in Chile by Liquid chromatography–UV detection–mass spectrometry. Food Chem. 2009;115:775–784. doi: 10.1016/J.FOODCHEM.2008.12.071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mariani C., Braca A., Vitalini S., De Tommasi N., Visioli F., Fico G. Flavonoid characterization and in vitro antioxidant activity of Aconitum anthora L. (Ranunculaceae) Phytochem. 2008;69:1220–1226. doi: 10.1016/J.PHYTOCHEM.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bakr R.O., El Bishbishy M.H. Profile of bioactive compounds of Capparis spinosa var. Aegyptiaca growing in Egypt. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2016;26:514–520. doi: 10.1016/J.BJP.2016.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miguel M., Barros L., Pereira C., Calhelha R.C., Garcia P.A., Castro Á., Santos-Buelga C., Ferreira I.C.F.R. Chemical characterization and bioactive properties of two aromatic plants: Calendula officinalis L. (Flowers) and Mentha cervina L. (Leaves) Food Funct. 2016;7:2223–2232. doi: 10.1039/c6fo00398b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ghareeb M., Saad A., Ahmed W., Refahy L., Nasr S. HPLC-DAD-ESI-MS/MS characterization of bioactive secondary metabolites from Strelitzia nicolai leaf extracts and their antioxidant and anticancer activities in vitro. Pharmacogn. Res. 2018;10:368–378. doi: 10.4103/pr.pr_89_18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang G., Lai M., Xu C., He S., Dong L., Huang F., Zhang R., Young D.J., Liu H., Su D. Novel catabolic pathway of quercetin-3-O-Rutinose-7-O-α-L-Rhamnoside by Lactobacillus plantarum GDMCC 1.140: the direct fission of C-ring. Front. Nutr. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/FNUT.2022.849439/BIBTEX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zheng W.H., Bai H.Y., Han S., Zhang K.X., Sun L.L., Du H., Yang Z.G. Analysis on the constituents of branches, berries, and leaves of Hippophae rhamnoides L. By UHPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS and their anti-inflammatory activities. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2019;14 doi: 10.1177/1934578X19871404. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lobo Roriz C., Barros L., Carvalho A.M., Santos-Buelga C., Ferreira I.C.F.R., Tridentatum Pterospartum. Gomphrena globosa and Cymbopogon citratus: a phytochemical study focused on antioxidant compounds. Int. Food Res. 2014;62:684–693. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2014.04.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guimarães R., Barros L., Dueñas M., Carvalho A.M., João M., Queiroz R.P., Santos-Buelga C., Ferreira I.C.F.R. Characterization of phenolic compounds in wild fruits from northeastern Portugal. Food Chem. 2013;141(4):3721–3830. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.06.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carvalho A.A., dos Santos L.R., de Freitas J.S., de Sousa R.P., de Farias R.R.S., Vieira Júnior G.M., Rai M., Chaves M.H. First report of flavonoids from leaves of Machaerium acutifolium by DI-ESI-MS/MS. Arab. J. Chem. 2022;15 doi: 10.1016/J.ARABJC.2022.103765. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Rijke E., Out P., Niessen W.M.A., Ariese F., Gooijer C., Brinkman U.A. The analytical separation and detection methods for flavonoids. J. Chromatogr. A. 2006;1112:31–63. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2006.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mirali M., Purves R.W., Vandenberg A. Profiling the phenolic compounds of the four major seed coat types and their relation to color genes in lentil. J. Nat. Prod. 2017;80:1310–1317. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.6b00872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bazghaleh N., Prashar P., Purves R.W., Vandenberg A. Polyphenolic composition of lentil roots in response to infection by Aphanomyces euteiches. Front. Plant Sci. 2018;9 doi: 10.3389/FPLS.2018.01131/BIBTEX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Llorent-Martinez E.J., Spinola V., Gouveia S., Castilho P.C. HPLC-ESI-MSn characterization of phenolic compounds, terpenoid saponins, and other minor compounds in Bituminaria bituminosa. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015;69:80–90. doi: 10.1016/J.INDCROP.2015.02.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lyubchyk S., Shapovalova O., Lygina O., Oliveira M.C., Appazov N., Lyubchyk A., Charmier A.J., Lyubchik S., Pombeiro A.J.L. Integrated green chemical Approach to the medicinal plant Carpobrotus edulis processing. Sci. Rep. 2019;9(1):1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-53817-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kuś P.M., Jerković I., Aladić K., Jokić S. Supercritical CO2 and ultrasound extraction and characterization of lipids and polyphenols from Phacelia tanacetifolia benth. Pollen, Ind. Crops Prod. 2023;206 doi: 10.1016/J.INDCROP.2023.117646. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang W., Zhang S., Lv L., Sang S. A new method to prepare and redefine black tea thearubigins. J. Chromatogr. A. 2018;1563:82–88. doi: 10.1016/J.CHROMA.2018.05.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Katayama S., Ohno F., Yamauchi Y., Kato M., Makabe H., Nakamura S. Enzymatic synthesis of novel phenol acid rutinosides using rutinase and their antiviral activity in vitro. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013;61:9617–9622. doi: 10.1021/JF4021703/SUPPL_FILE/JF4021703_SI_001.PDF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.El Gendy S.M., Ezzat M.I., EL Sayed A.M., Saad A.S., Elmotayam A.K. HPLC-PDA-ESI-MS-MS analysis of acids content of Lantana camara L. Flower extract and its anticoagulant activity, Egypt. J. Chem. 2023;66:249–256. doi: 10.21608/EJCHEM.2022.129350.5715. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bystrom L.M., Lewis B.A., Brown D.L., Rodriguez E., Obendorf R.L. Characterisation of phenolics by LC–UV/vis, LC–MS/MS and sugars by GC in Melicoccus bijugatus Jacq. ‘Montgomery’ fruits. Food Chem. 2008;111:1017–1024. doi: 10.1016/J.FOODCHEM.2008.04.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.López-Cobo A., Gómez-Caravaca A.M., Pasini F., Caboni M.F., Segura-Carretero A., Fernández-Gutiérrez A. HPLC-DAD-ESI-QTOF-MS and HPLC-FLD-MS as valuable tools for the determination of phenolic and other polar compounds in the edible part and by-products of avocado. LWT. 2016;73:505–513. doi: 10.1016/J.LWT.2016.06.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang R.T., Lu J.F., Inbaraj B.S., Chen B.H. Determination of phenolic acids and flavonoids in Rhinacanthus nasutus (L.) Kurz by high-performance-liquid-chromatography with photodiode-array detection and tandem mass spectrometry. J. Funct.Foods. 2015;12:498–508. doi: 10.1016/J.JFF.2014.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen J., Ge Z.Z., Zhu W., Xu Z., Li C.M. Screening of key antioxidant compounds of longan (Dimocarpus longan lour.) seed extract by combining online fishing/knockout, activity evaluation, fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry, and high-performance Liquid Chromatography electrospray ionization mass spectrometry methods. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014;62:9744–9750. doi: 10.1021/JF502995z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Khadke S.K., Lee J.H., Kim Y.G., Raj V., Lee J. Assessment of antibiofilm potencies of nervonic and oleic acid against Acinetobacter baumannii using in vitro and computational approaches. Biomedicines. 2021;9:1133. doi: 10.3390/BIOMEDICINES9091133/S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Goc A., Niedzwiecki A., Rath M. Anti-borreliae efficacy of selected organic oils and fatty acids. BMC Complement Altern. Med. 2019;19:40. doi: 10.1186/S12906-019-2450-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shamsudin N.F., Ahmed Q.U., Mahmood S., Ali Shah S.A., Khatib A., Mukhtar S., Alsharif M.A., Parveen H., Zakaria Z.A. Antibacterial effects of flavonoids and their structure-activity relationship study: a comparative interpretation. Molecules. 2022;27:1149. doi: 10.3390/molecules27041149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Manso T., Lores M., de Miguel T. Antimicrobial activity of polyphenols and natural polyphenolic extracts on clinical isolates. Antibiotics. 2021 Dec 30;11(1):46. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11010046. PMID: 35052923; PMCID: PMC8773215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Casillas-Vargas G., Ocasio-Malavé C., Medina S., Morales-Guzmán C., Del Valle R.G., Carballeira N.M., Sanabria-Ríos D.J. Antibacterial fatty acids: an update of possible mechanisms of action and implications in the development of the next-generation of antibacterial agents. Prog. Lipid Res. 2021;82 doi: 10.1016/J.PLIPRES.2021.101093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Silva D., Nunes P., Melo J., Quintas C. Microbial quality of edible seeds commercially available in southern Portugal. AIMS Microbiol. 2022;8:42. doi: 10.3934/MICROBIOL.2022004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hassan S.A., Hagrassi A.M., Hammam O., Soliman A.M., Ezzeldin E., Aziz W.M. Brassica juncea L. (Mustard) extract silver NanoParticles and knocking off oxidative stress, ProInflammatory cytokine and reverse DNA genotoxicity. Biomolecules. 2020;10:1650. doi: 10.3390/BIOM10121650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ramazzina I., Lolli V., Lacey K., Tappi S., Rocculi P., Rinaldi M. Fresh-cut Eruca sativa treated with plasma activated water (PAW): evaluation of antioxidant capacity, polyphenolic profile and redox status in Caco2 cells. Nutrients. 2022;14:5337. doi: 10.3390/NU14245337/S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, [J.P.].