Abstract

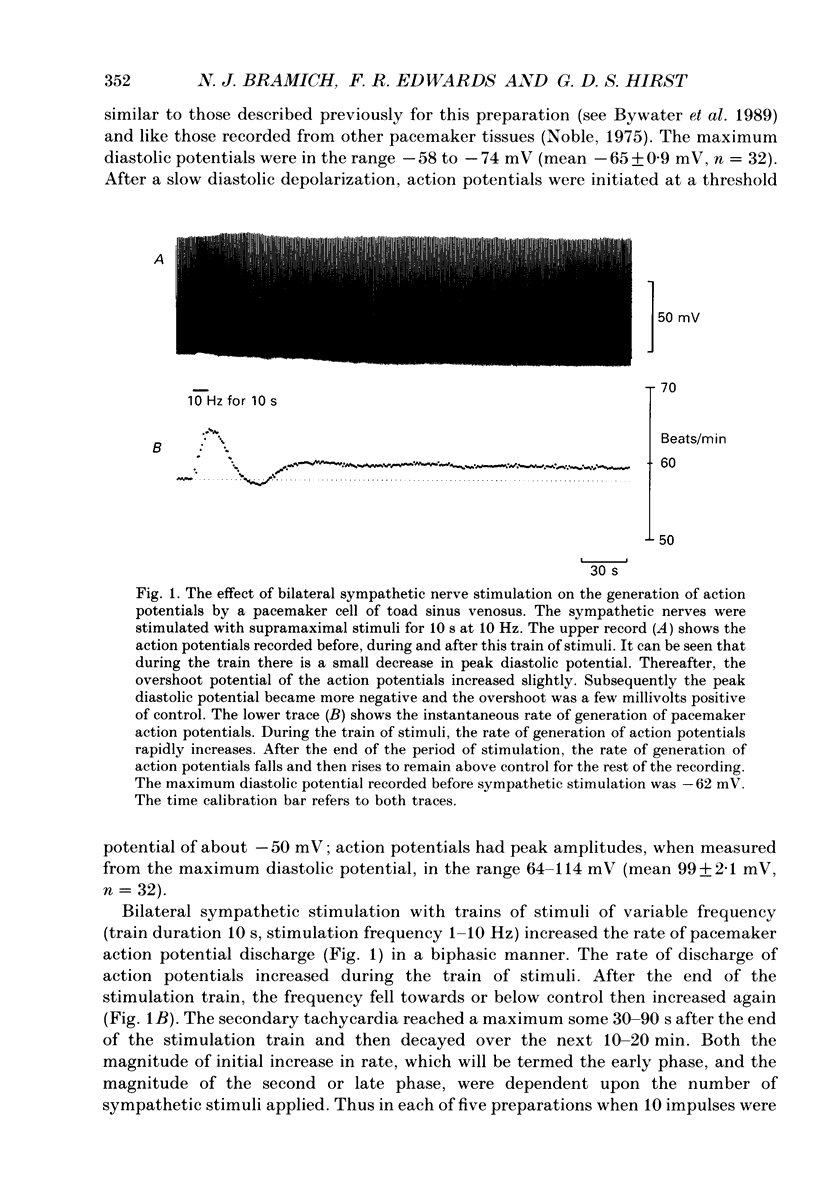

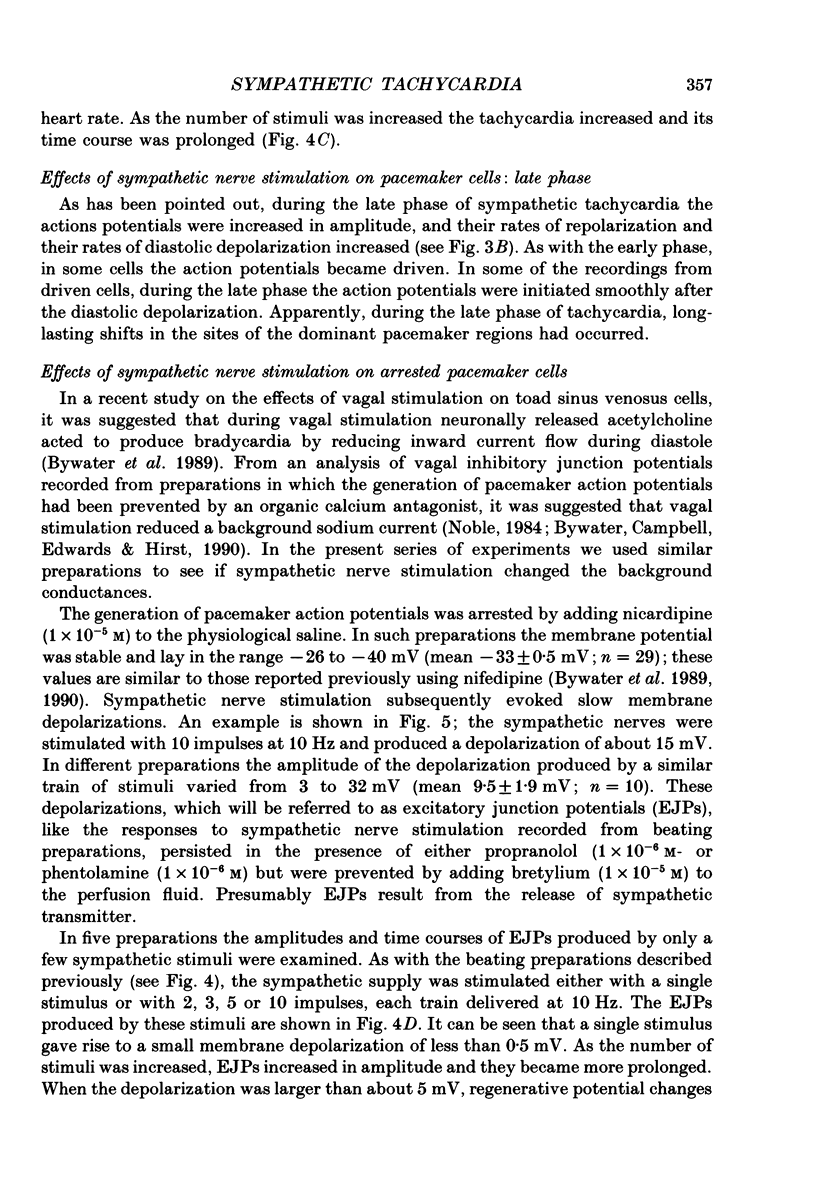

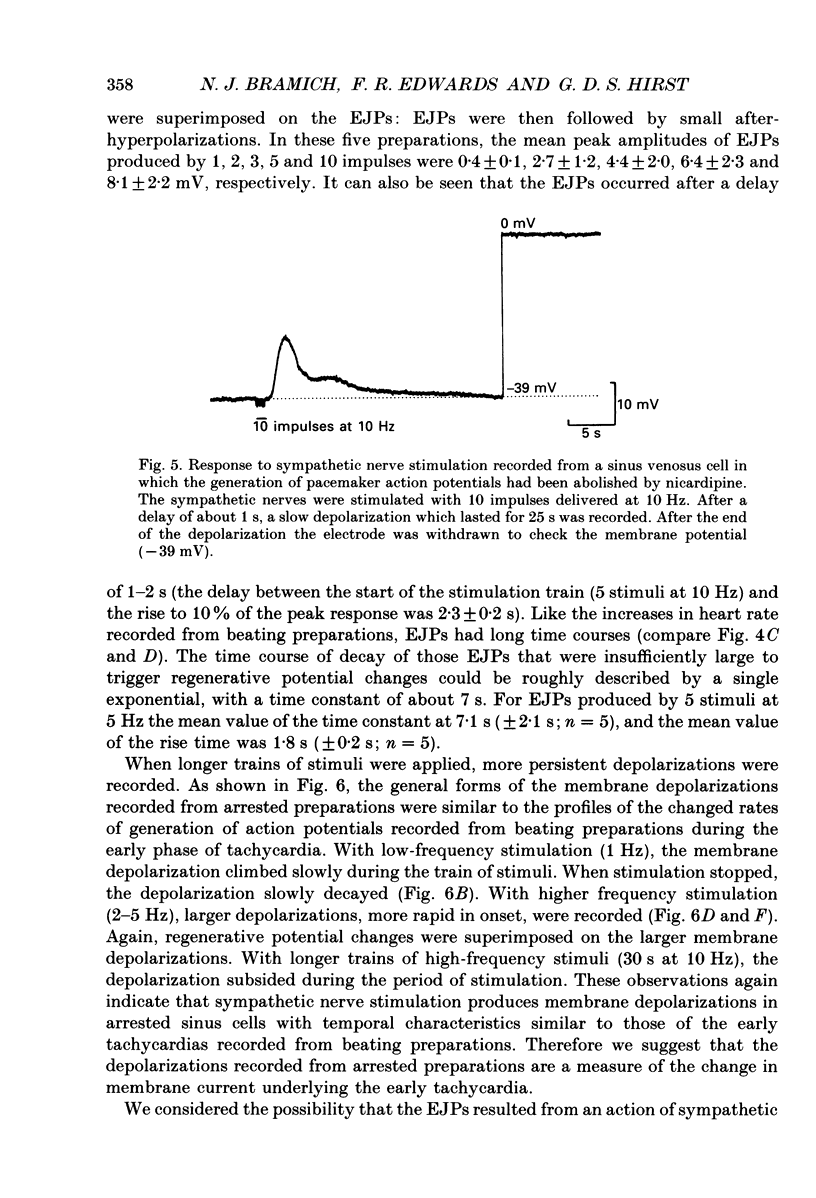

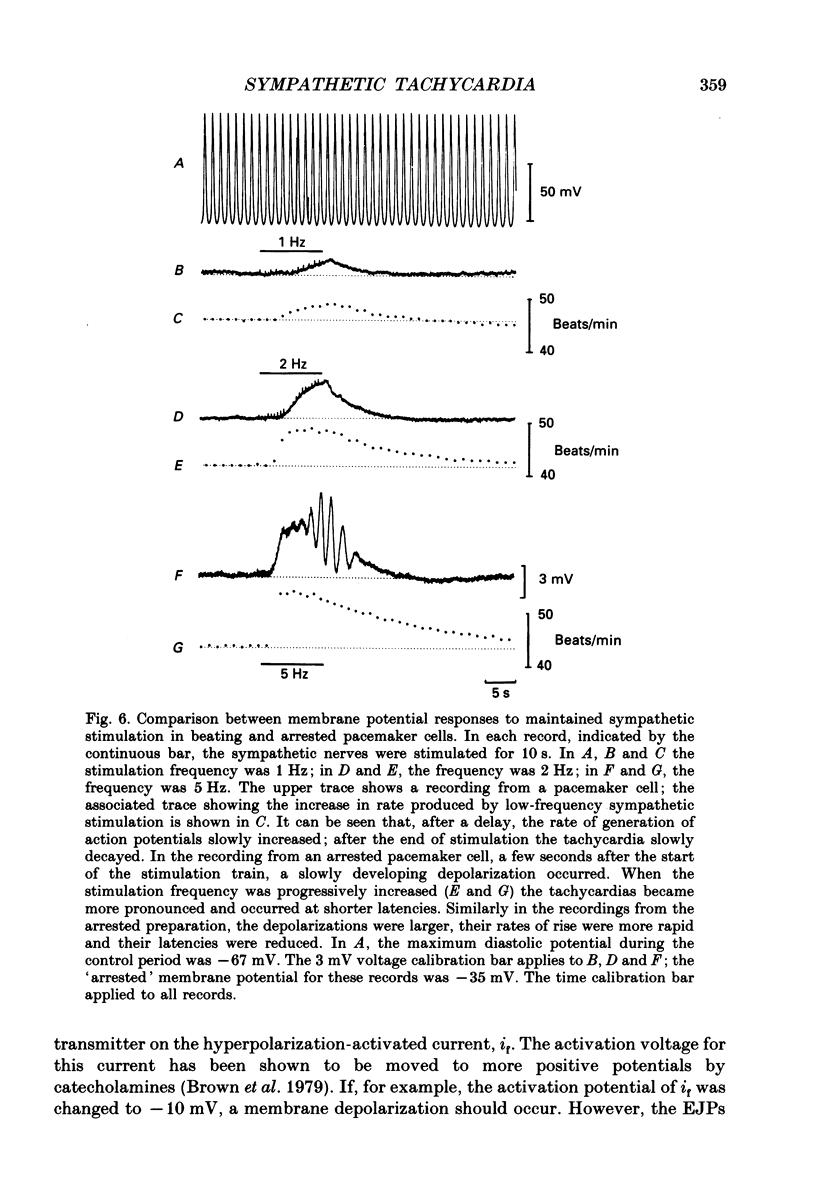

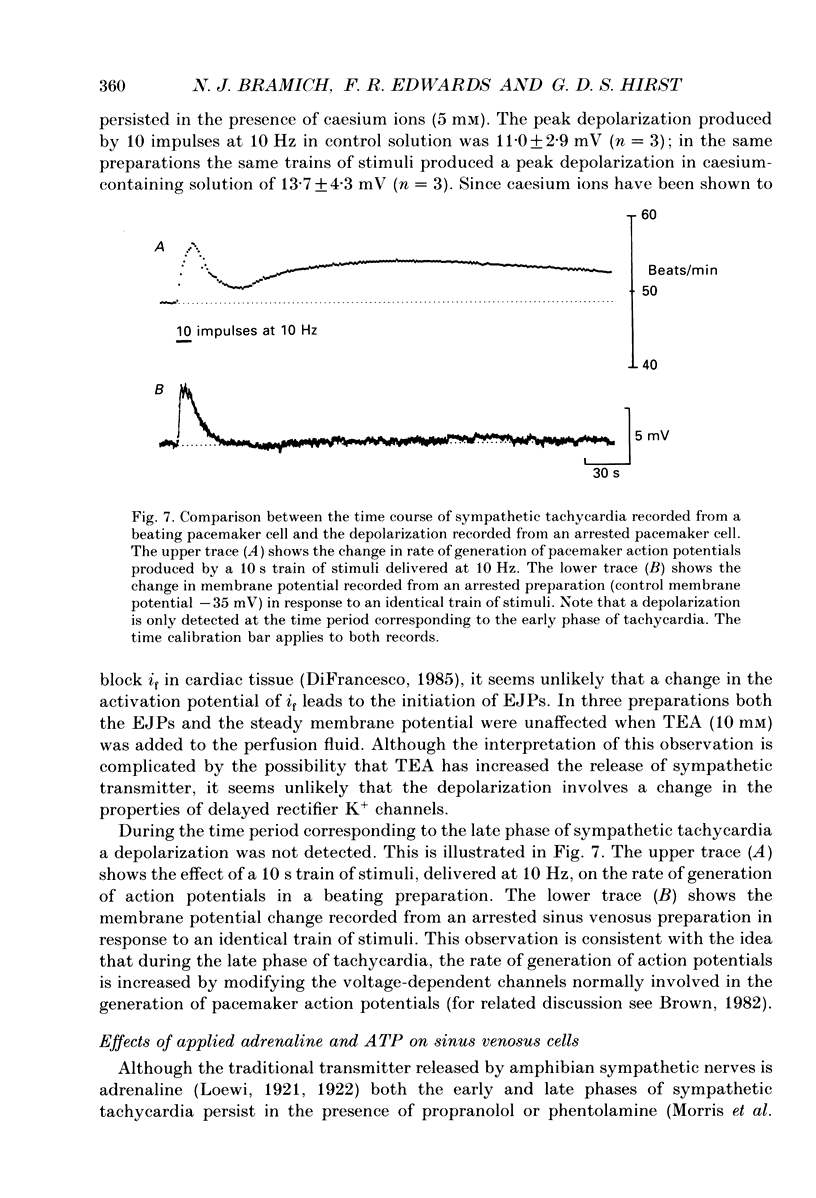

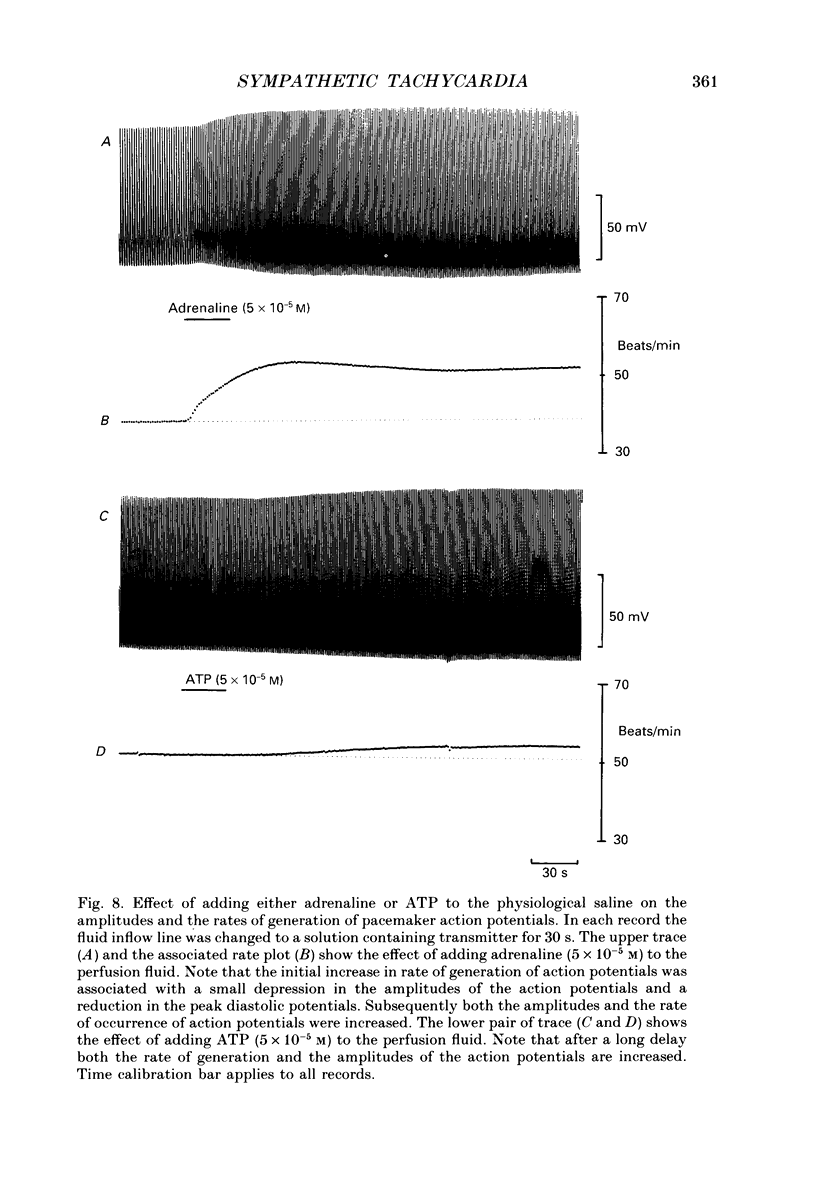

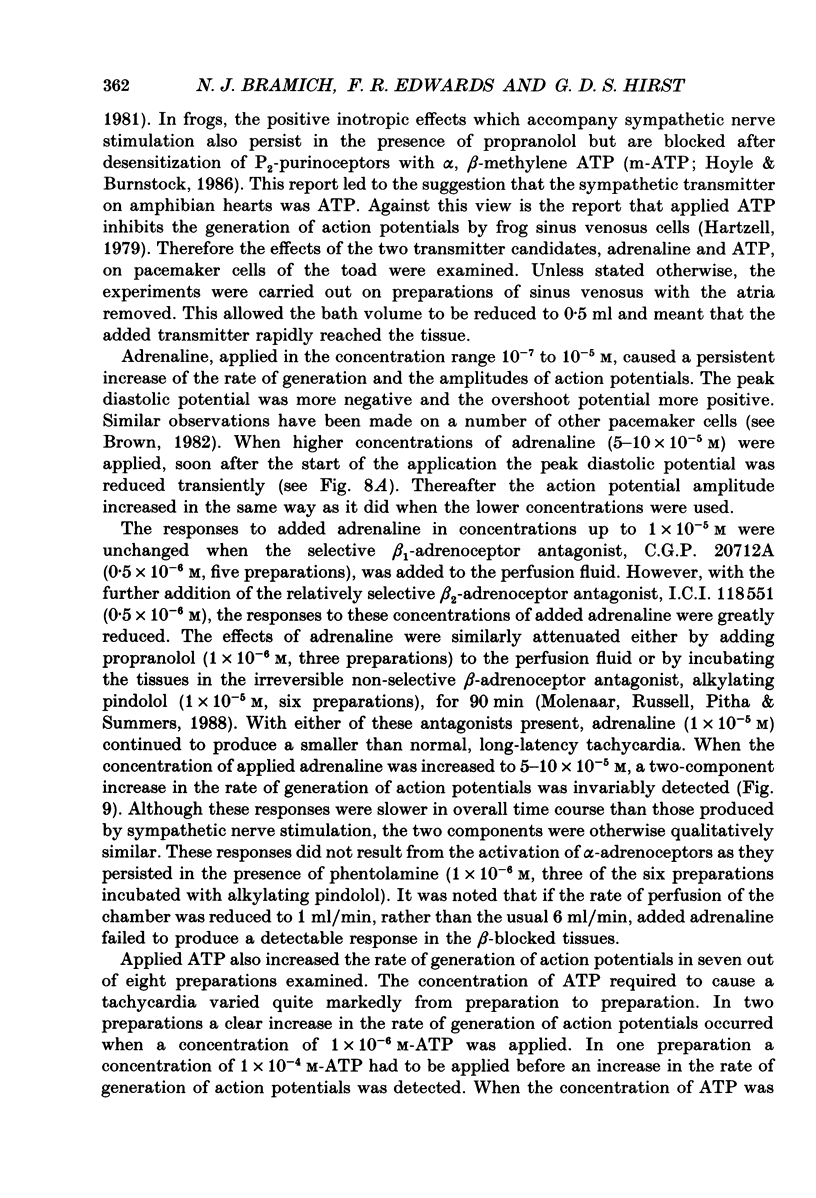

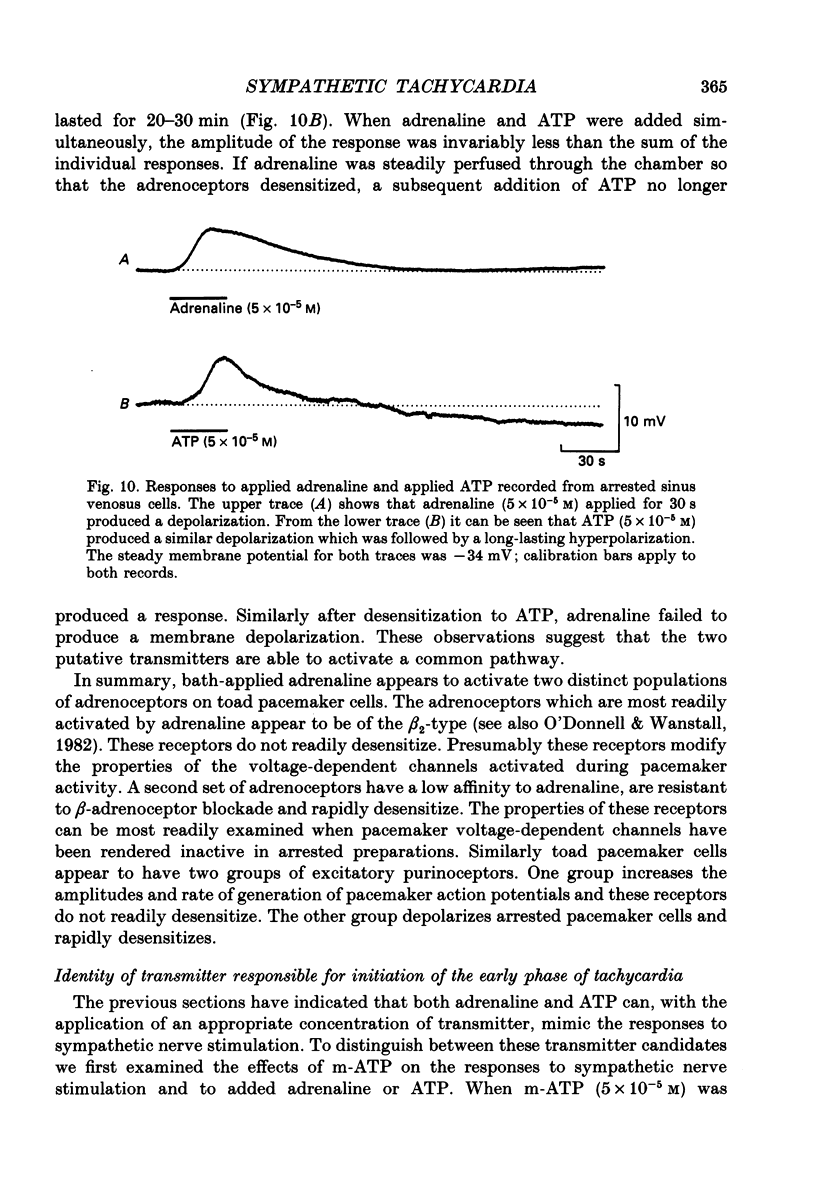

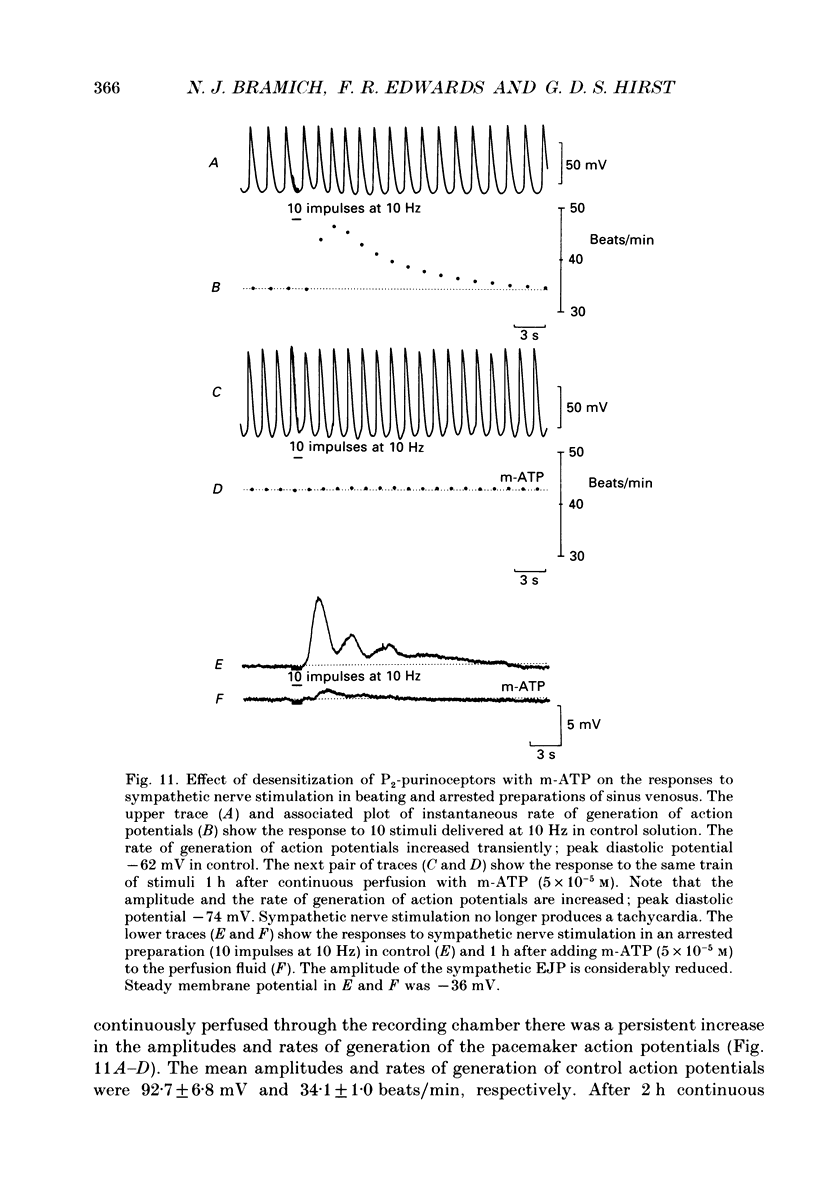

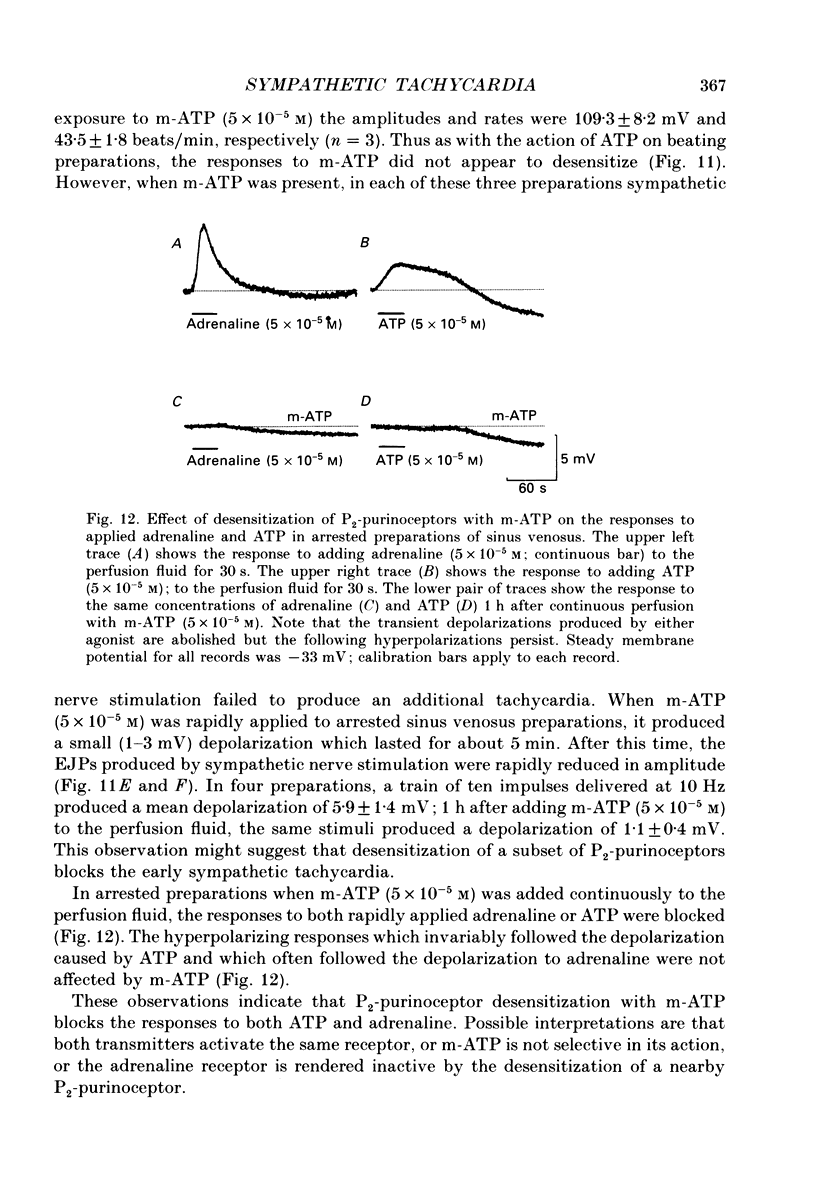

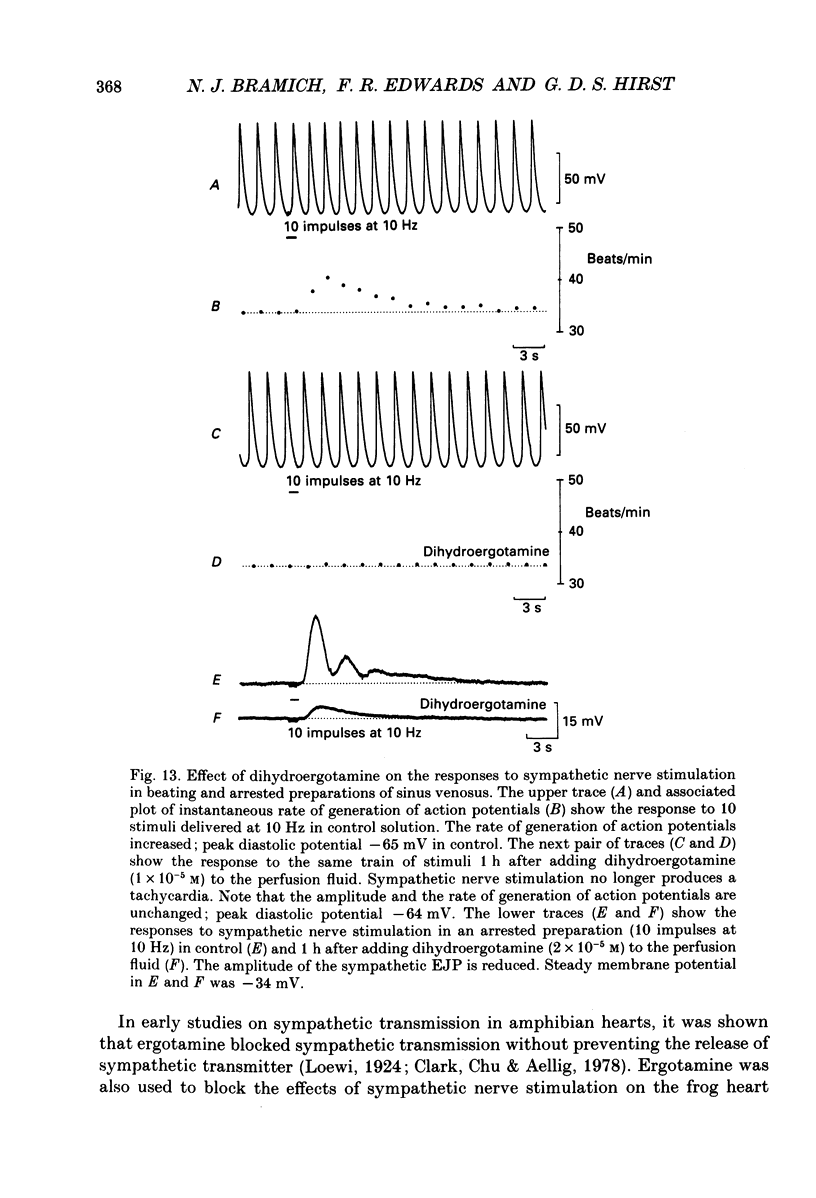

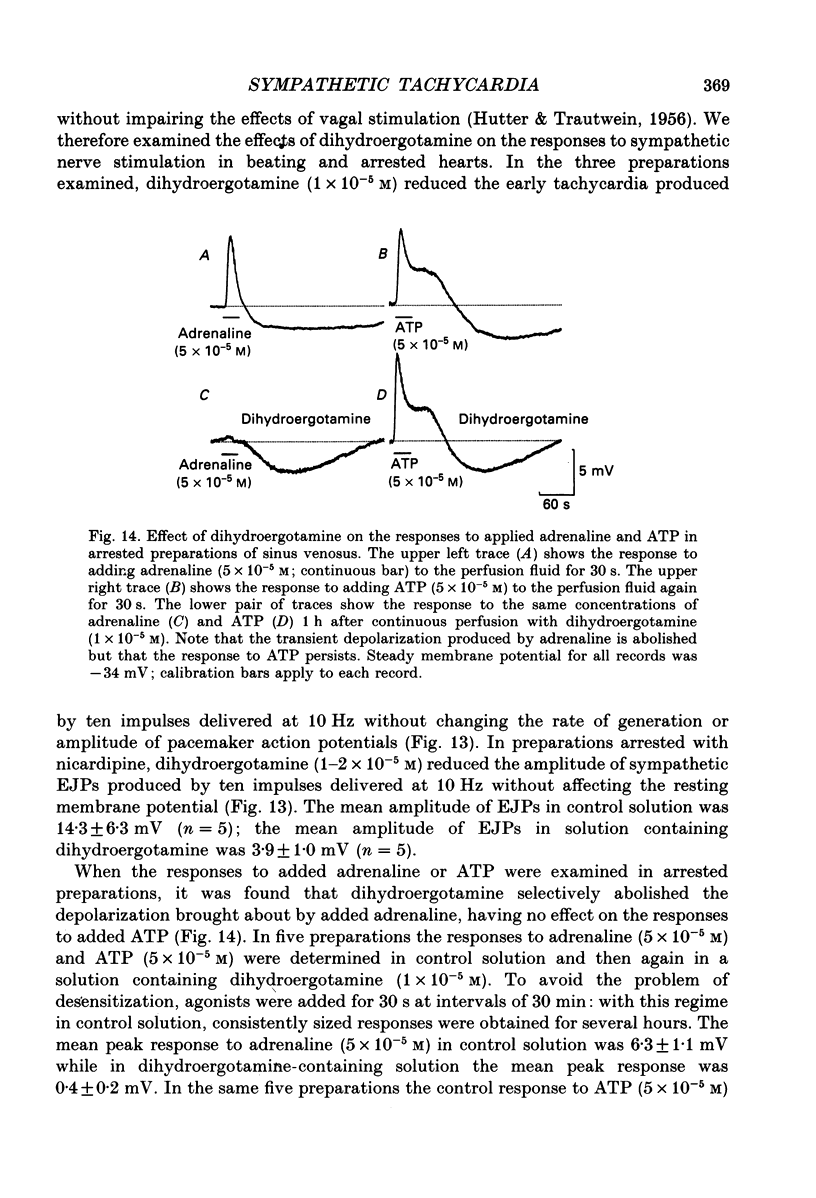

1. The effect of sympathetic nerve stimulation on pacemaker cells of the isolated sinus venosus of the toad, Bufo marinus, were examined using intracellular recording techniques. 2. Train of stimuli applied to the sympathetic outflow led to a two-component increase in heart rate. Shortly after the onset of stimulation the rate of discharge of pacemaker action potentials increased. After the end of the train of stimuli, the heart rate fell and then again increased to remain high for several minutes. 3. During the early tachycardia, the peak diastolic potential was reduced and the rate of diastolic depolarization increased. During the late tachycardia, the peak diastolic potential and rate of diastolic depolarization were increased; both the amplitude and the rate of repolarization of the action potentials were increased. 4. When membrane potential recordings were made from sinus venosus cells in which beating had been abolished by adding the organic calcium antagonist nicardipine, sympathetic nerve stimulation caused membrane depolarization. 5. The responses to sympathetic nerve stimulation, recorded from beating or arrested hearts, were abolished by bretylium but persisted in the presence of a number of beta-adrenoceptor antagonists. 6. Bath-applied adrenaline caused a tachycardia which was associated with a large increase in the amplitudes of pacemaker action potentials. These effects were largely mediated by the activation of beta 2-adrenoceptors. 7. In the presence of high concentrations of beta-adrenoceptor antagonists, applied adrenaline produced membrane potential changes that although slower in time course were similar to those produced by sympathetic nerve stimulation. 8. Many aspects of the responses to nerve stimulation could be mimicked by applied ATP. 9. The early phase of sympathetic tachycardia was abolished after P2-purinoceptor desensitization; this phase was also inhibited by dihydroergotamine. 10. The results are discussed in relation to the idea that sympathetic nerve stimulation causes the early tachycardia by increasing inward current flow during diastole, a response involving activation of specialized adrenoceptors and perhaps ATP receptors.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Brown H. F., DiFrancesco D., Noble S. J. How does adrenaline accelerate the heart? Nature. 1979 Jul 19;280(5719):235–236. doi: 10.1038/280235a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown H. F. Electrophysiology of the sinoatrial node. Physiol Rev. 1982 Apr;62(2):505–530. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1982.62.2.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G., Meghji P. Distribution of P1- and P2-purinoceptors in the guinea-pig and frog heart. Br J Pharmacol. 1981 Aug;73(4):879–885. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1981.tb08741.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bywater R. A., Campbell G. D., Edwards F. R., Hirst G. D. Effects of vagal stimulation and applied acetylcholine on the arrested sinus venosus of the toad. J Physiol. 1990 Jun;425:1–27. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bywater R. A., Campbell G., Edwards F. R., Hirst G. D., O'Shea J. E. The effects of vagal stimulation and applied acetylcholine on the sinus venosus of the toad. J Physiol. 1989 Aug;415:35–56. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell G. D., Edwards F. R., Hirst G. D., O'Shea J. E. Effects of vagal stimulation and applied acetylcholine on pacemaker potentials in the guinea-pig heart. J Physiol. 1989 Aug;415:57–68. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell G., Gibbins I. L., Morris J. L., Furness J. B., Costa M., Oliver J. R., Beardsley A. M., Murphy R. Somatostatin is contained in and released from cholinergic nerves in the heart of the toad Bufo marinus. Neuroscience. 1982;7(9):2013–2023. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(82)90116-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFrancesco D. The cardiac hyperpolarizing-activated current, if. Origins and developments. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1985;46(3):163–183. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(85)90008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dukes I. D., Vaughan Williams E. M. Effects of selective alpha 1-, alpha 2-, beta 1-and beta 2-adrenoceptor stimulation on potentials and contractions in the rabbit heart. J Physiol. 1984 Oct;355:523–546. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan T. M., Noble D., Noble S. J., Powell T., Twist V. W., Yamaoka K. On the mechanism of isoprenaline- and forskolin-induced depolarization of single guinea-pig ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 1988 Jun;400:299–320. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friel D. D., Bean B. P. Two ATP-activated conductances in bullfrog atrial cells. J Gen Physiol. 1988 Jan;91(1):1–27. doi: 10.1085/jgp.91.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUTTER O. F., TRAUTWEIN W. Effect of vagal stimulation on the sinus venosus of the frog's heart. Nature. 1955 Sep 10;176(4480):512–513. doi: 10.1038/176512a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUTTER O. F., TRAUTWEIN W. Vagal and sympathetic effects on the pacemaker fibers in the sinus venosus of the heart. J Gen Physiol. 1956 May 20;39(5):715–733. doi: 10.1085/jgp.39.5.715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara N., Irisawa H., Kameyama M. Contribution of two types of calcium currents to the pacemaker potentials of rabbit sino-atrial node cells. J Physiol. 1988 Jan;395:233–253. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp016916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartzell H. C. Adenosine receptors in frog sinus venosus: slow inhibitory potentials produced by adenine compounds and acetylcholine. J Physiol. 1979 Aug;293:23–49. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1979.sp012877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle C. H., Burnstock G. Evidence that ATP is a neurotransmitter in the frog heart. Eur J Pharmacol. 1986 May 27;124(3):285–289. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(86)90229-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C. R., Molenaar P., Summers R. J. New views of human cardiac beta-adrenoceptors. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1989 May;21(5):519–535. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(89)90791-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyahara H., Suzuki H. Pre- and post-junctional effects of adenosine triphosphate on noradrenergic transmission in the rabbit ear artery. J Physiol. 1987 Aug;389:423–440. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molenaar P., Russell F., Pitha J., Summers R. Persistent beta-adrenoceptor blockade with alkylating pindolol (BIM) in guinea-pig left atria and trachea. Biochem Pharmacol. 1988 Oct 1;37(19):3601–3607. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(88)90390-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore L. E., Clark R. B., Shibata E. F., Giles W. R. Comparison of steady-state electrophysiological properties of isolated cells from bullfrog atrium and sinus venosus. J Membr Biol. 1986;89(2):131–138. doi: 10.1007/BF01869709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris J. L., Gibbins I. L., Clevers J. Resistance of adrenergic neurotransmission in the toad heart to adrenoceptor blockade. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1981;317(4):331–338. doi: 10.1007/BF00501315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble D. The surprising heart: a review of recent progress in cardiac electrophysiology. J Physiol. 1984 Aug;353:1–50. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell S. R., Wanstall J. C. Pharmacological experiments demonstrate that toad (Bufo marinus) atrial beta-adrenoceptors are not identical with mammalian beta 2- or beta 1-adrenoceptors. Life Sci. 1982 Aug 16;31(7):701–708. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(82)90772-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata E. F., Giles W., Pollack G. H. Threshold effects of acetylcholine on primary pacemaker cells of the rabbit sino-atrial node. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1985 Jan 22;223(1232):355–378. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1985.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stene-Larsen G., Helle K. B. Cardiac beta2-adrenoceptor in the frog. Comp Biochem Physiol C. 1978;60(2):165–173. doi: 10.1016/0306-4492(78)90090-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

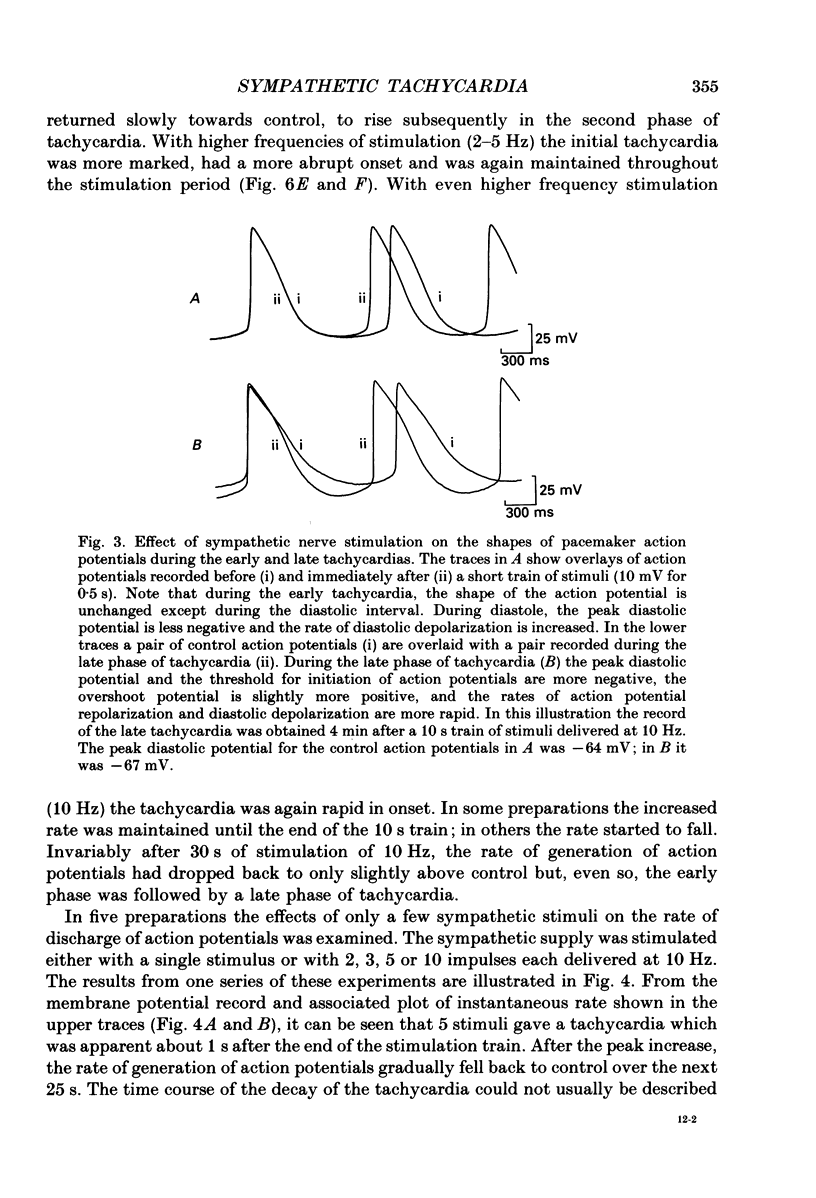

- Toda N., Shimamoto K. The influence of sympathetic stimulation on transmembrane potentials in the S-A node. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1968 Feb;159(2):298–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]