Abstract

Objective To determine the effect of perioperative β blocker treatment in patients having non-cardiac surgery.

Design Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources Seven search strategies, including searching two bibliographic databases and hand searching seven medical journals.

Study selection and outcomes We included randomised controlled trials that evaluated β blocker treatment in patients having non-cardiac surgery. Perioperative outcomes within 30 days of surgery included total mortality, cardiovascular mortality, non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal cardiac arrest, non-fatal stroke, congestive heart failure, hypotension needing treatment, bradycardia needing treatment, and bronchospasm.

Results Twenty two trials that randomised a total of 2437 patients met the eligibility criteria. Perioperative β blockers did not show any statistically significant beneficial effects on any of the individual outcomes and the only nominally statistically significant beneficial relative risk was 0.44 (95% confidence interval 0.20 to 0.97, 99% confidence interval 0.16 to 1.24) for the composite outcome of cardiovascular mortality, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and non-fatal cardiac arrest. Methods adapted from formal interim monitoring boundaries applied to cumulative meta-analysis showed that the evidence failed, by a considerable degree, to meet standards for forgoing additional studies. The individual safety outcomes in patients treated with perioperative β blockers showed a relative risk for bradycardia needing treatment of 2.27 (95% CI 1.53 to 3.36, 99% CI 1.36 to 3.80) and a nominally statistically significant relative risk for hypotension needing treatment of 1.27 (95% CI 1.04 to 1.56, 99% CI 0.97 to 1.66).

Conclusion The evidence that perioperative β blockers reduce major cardiovascular events is encouraging but too unreliable to allow definitive conclusions to be drawn.

Introduction

Non-cardiac surgery is associated with an increase in catecholamines,1 which results in an increase in blood pressure, heart rate, and free fatty acid concentrations.2-4 β blockers suppress the effects of increased catecholamines and as a result may prevent perioperative cardiovascular events.

Several authors and guideline committees have advocated the use of β blockers for patients having non-cardiac surgery.5-8 The two authors of the American College of Physicians' non-cardiac surgery perioperative guidelines inserted an addendum, after the college had approved the guidelines, advocating the use of perioperative atenolol in patients with coronary artery disease.7 More recently, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on guidelines for non-cardiac surgery recommended perioperative β blockers for patients with preoperative stress test ischaemia having vascular surgery (class I recommendation) and for patients with established coronary artery disease, risk factors for coronary artery disease, or untreated hypertension having non-cardiac surgery (class IIa recommendation).8 Other authors have questioned the robustness of the evidence for perioperative β blockers and have advocated the need for a large definitive randomised controlled trial.9,10

Accurate understanding of the strength of the evidence for perioperative β blockers requires a systematic, comprehensive, and unbiased accumulation of the available evidence and methods adapted from formal interim monitoring boundaries applied to cumulative meta-analysis.11 We therefore undertook a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the effect of β blockers on cardiovascular events in patients having non-cardiac surgery.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

We included randomised controlled trials that evaluated the effect of β blocker treatment in patients having non-cardiac surgery. Randomised controlled trials were eligible regardless of their publication status, language, or primary objectives. We excluded trials in which no control group received a placebo or standard care and those in which no relevant events occurred in the treatment and control groups, as these trials provide no information on the magnitude of treatment effects.12

Study identification

Strategies to identify studies included an electronic search of two bibliographical databases (see appendix A on bmj.com); a hand search of seven anaesthesia journals (appendix A); consultation with experts; our own files; review of reference lists from eligible trials; use of the “see related articles” feature for key publications in PubMed (April 2003); and search of SciSearch (April 2003) for publications that cited key publications.

Assessment of study eligibility

Two researchers independently evaluated study eligibility (κ = 0.96). The consensus process to resolve disagreements required researchers to discuss the reasoning for their decisions; in all cases, one person recognised an error.

Data collection and quality assessment

We abstracted descriptive data (such as type of surgery, patient population) and markers of validity (such as concealment, blinding) from all trials. We abstracted data on the following perioperative outcomes: total mortality, cardiovascular mortality, non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal cardiac arrest, non-fatal stroke, congestive heart failure, hypotension needing treatment, bradycardia needing treatment, bronchospasm, and the composite outcome of major perioperative cardiovascular events (cardiovascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, or non-fatal cardiac arrest). We defined perioperative outcomes as outcomes that occurred within 30 days of surgery.

The definitions of outcomes were those used in the original trials, except when a trial did not define or report one of our main outcomes. We anticipated that three of our main outcomes would not be defined or reported in all trials. We therefore defined, a priori, cardiovascular death, bradycardia needing treatment, and hypotension needing treatment (see appendix B on bmj.com).

Teams of two researchers independently abstracted data from all trials (κ = 0.69-1.0). Disagreements were resolved by consensus according to the process described above.

Statistical analysis

For each trial we calculated the relative risks of the outcomes for patients receiving perioperative β blocker treatment compared with patients receiving placebo or standard care. For each relative risk we determined the conventional 95% confidence limit and the 99% confidence limit. When (as with small trials with few or a moderate number of events) statistical significance depends on a difference of only a handful of events, the 99% confidence interval may better convey our confidence in the estimate of the treatment effect.

We did analyses on an intention to treat basis. We pooled relative risks by using the DerSimonian and Laird random effects model.13 We calculated an I2 value as a measure of heterogeneity for each outcome analysis. An I2 value represents the percentage of total variation across trials that is due to heterogeneity rather than to chance, and we considered I2 < 25% as low and I2 > 75% as high.14 Before the analyses we specified several hypotheses related to the markers of trial validity, treatment interventions, and duration of follow-up to explain potential heterogeneity (I2 > 25%). We entered data in duplicate and used RevMan 4.2 (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford) for all analyses.

Because no reason exists why the standards for a meta-analysis should be less rigorous than those for a good single randomised controlled trial, we used methods adapted from formal interim monitoring boundaries applied to cumulative meta-analysis to assess the reliability and conclusiveness of the available evidence on perioperative β blockers,15 focusing on the composite outcome of major perioperative cardiovascular events. The sample size needed for a reliable and conclusive meta-analysis is at least as large as that for a single optimally powered randomised controlled trial, so we calculated the sample size (optimal information size) requirement for our meta-analysis. We did formal interim monitoring for meta-analyses by using the optimal information size to help to construct a Lan DeMets sequential monitoring boundary for our meta-analysis,15 analogous to interim monitoring in a randomised controlled trial. We used this monitoring boundary as a way of determining whether the evidence in our meta-analysis was reliable and conclusive.

Results

Included trials

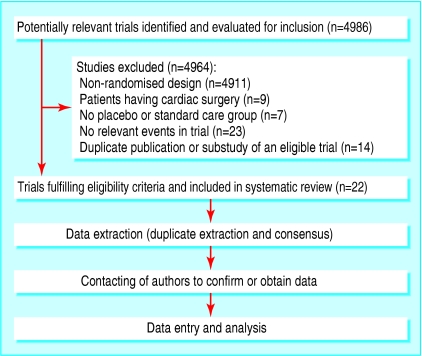

We identified 22 randomised controlled trials published between 1980 and 2004 that fulfilled our eligibility criteria (fig 1).16-37 We obtained data from or confirmed them with trialists from all included trials. Table 1 summarises the design characteristics of the included trials.16-37 The 22 trials randomised a total of 2437 patients, and the median sample size was 61 patients. The type of non-cardiac surgery was unrestricted in eight trials. Treatment interventions varied from brief intravenous β blocker just before surgery to 30 day postoperative β blocker use. The duration of follow-up was limited to the end of surgery in one trial and until discharge from the recovery room in five trials.

Fig 1.

Flowchart of randomised controlled trials through the systematic review

Table 1.

Design characteristics of randomised controlled trials included in systematic review

| Trials | Year of publication | No randomised | Type of surgery and patient population | Intervention | Length of follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coleman16 | 1980 | 42 | Inpatient elective general non-cardiac surgery | Metoprolol 2 mg or 4 mg, or placebo injection just before anaesthesia | Discharge from hospital |

| Cucchiara17 | 1986 | 74 | Inpatient carotid endarterectomy; patients with an MI in the preceding six months and CHF were excluded | Esmolol 500 μg/kg/min for 4 minutes then 300 μg/kg/min for 8 minutes or placebo infusion starting 5 minutes before anaesthesia | End of surgery |

| Jakobsen18 | 1986 | 20 | Inpatient middle ear or nasal septum surgery; patients with evidence of cardiopulmonary disease were excluded | Oral metoprolol 50 mg or placebo the day before surgery and metoprolol 100 mg or placebo 1.5-3 hours before anaesthesia | Discharge from recovery room |

| Liu19 | 1986 | 30 | Non-cardiac surgery (primarily gynaecological); unclear if restricted to inpatient surgery; patients were ASA class I | Esmolol 500 μg/kg/min for 4 minutes then 300 μg/kg/min for 8 minutes or placebo infusion starting 5 minutes before anaesthesia | Discharge from recovery room |

| Magnusson20 | 1986 | 30 | Inpatient cholecystectomy or hemia repair; patients had untreated hypertension but no prior MI or CHF | Oral metoprolol 200 mg or placebo daily for at least 2 weeks before surgery and the morning of surgery, and metoprolol 15 mg or placebo injection just before anaesthesia | Discharge from hospital |

| Gibson21 | 1988 | 40 | Inpatient neurosurgery; patients had a ≥20% increase in systolic blood pressure above ward pressure on emergence from anaesthesia | Esmolol 40 mg/min or placebo infusion for 4 minutes just before extubation and then esmolol 24 mg/min or placebo infusion for 10 minutes | Discharge from recovery room |

| Stone22 | 1988 | 128 | Inpatient major non-cardiac surgery; patients had untreated hypertension but no CAD or CHF | Oral labetalol 100 mg, atenolol 50 mg, oxprenolol 20 mg, or usual care 2 hours before surgery. | Discharge from hospital |

| Mackenzie23 | 1989 | 100 | Outpatient gynaecological surgery or dental extractions | Oral timolol 10 mg or placebo 72 minutes before anaesthesia | Discharge from hospital |

| Inada24 | 1989 | 30 | Inpatient elective non-cardiac surgery; patients with CHF, unstable angina, or ASA class IV were excluded | Labetalol 5 mg or 10 mg or placebo injection 2 minutes before anaesthesia | Discharge from recovery room |

| Leslie25 | 1989 | 60 | Inpatient elective non-cardiac surgery; patients were ASA class I or II but no prior MI or CHF | Labetalol 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, or 1 mg/kg or placebo injection just before surgery | Discharge from hospital |

| Jakobsen26 | 1990 | 98 | Inpatient elective hysterectomy or lower extremity orthopaedic surgery; patients were ASA class I or II | Oral metoprolol (slow release) 100 mg or placebo 1-3 hours before surgery | Discharge from hospital |

| Miller27 | 1990 | 45 | Inpatient elective peripheral vascular surgery; patients had known CAD or ≥2 risk factors but no history of CHF or MI within six months of surgery | Esmolol 1.5 mg/kg or 3.0 mg/kg or placebo injection just before anaesthesia | Discharge from hospital |

| Miller28 | 1991 | 548 | Inpatient elective non-cardiac surgery; patients had no history of CHF or MI within six months of surgery | Esmolol 100 mg or 200 mg or placebo injection just before anaesthesia | Discharge from recovery room |

| Davies29 | 1992 | 40 | Inpatient carotid endarterectomy | Oral atenolol 50 mg or placebo 2 hours before surgery | Day 4 post-surgery |

| Jakobsen30 | 1997 | 36 | Inpatient elective thoracotomy for lung resection; patients without cardiovascular problems | Oral metoprolol 100 mg or placebo 90 minutes before surgery and once daily thereafter until day 11 post-surgery or discharge from hospital if sooner | Day 11 post-surgery or discharge from hospital if sooner |

| Wallace31 | 1998 | 200 | Inpatient elective non-cardiac surgery; patients with or at risk for CAD | Atenolol 5 mg (for HR≥55 bpm and SBP≥100 mm Hg) or placebo injection twice 30 minutes before surgery with repeat dosing immediately after surgery; daily thereafter the study drug was given the same way twice a day, or oral atenolol 100 mg (for HR>65 bpm and SBP≥100 mm Hg) or 50 mg (for HR 55-65 bpm and SBP≥100 mm Hg) or placebo on the first postoperative morning and each day until day 7 post-surgery or discharge from hospital if sooner | Discharge from hospital |

| Bayliff32 | 1999 | 99 | Inpatient major (non-cardiac) thoracic surgery | Oral propranolol 10 mg or placebo every 6 hours, starting before surgery and continuing for 5 days post-surgery | Discharge from hospital |

| Poldermans33 | 1999 | 112 | Inpatient elective abdominal aortic or infrainguinal arterial surgery; patients had a cardiac risk factor and a positive dobutamine echocardiography study | Oral bisoprolol 5 mg daily for a least a week before surgery and then 10 mg daily if HR>60 bpm; post-surgery the study drug was continued for 30 days; patients unable to take drugs orally were given metoprolol infusions to keep HR below 80 bpm; control group received standard perioperative care | Day 30 post-surgery |

| Raby34 | 1999 | 26 | Inpatient elective vascular surgery; patients had ischaemia during preoperative Holter monitor testing | Esmolol or placebo infusion adjusted every hour to reduce HR below a predetermined ischaemic threshold starting immediately post-surgery and continuing for 48 hours | Hour 49 post-surgery |

| Zaugg35 | 1999 | 63 | Inpatient elective major non-cardiac surgery; patients with CHF were excluded | Group 1—control group received standard perioperative care. Group 2—atenolol 5 mg (for HR>54 bpm and SBP>99 mm Hg) injection twice 30 minutes before surgery, repeat dosing immediately after surgery, and twice daily thereafter for 72 hours. Group 3—atenolol 5 mg injections every 5 minutes during surgery to maintain HR<80 bpm and MAP≤20% of preoperative MAP | Discharge from hospital |

| Urban36 | 2000 | 120 | Inpatient elective total knee arthroplasty; patients had known or probably CAD | Esmolol infusion started within first hour after surgery and titrated to keep HR<80 bpm until next morning, then metoprolol 25 mg twice daily with titration to keep HR<80 bpm; study drug continued until discharge from hospital; control group received standard perioperative care | Discharge from hospital |

| Yang37 | 2004 | 496 | Inpatient elective vascular surgery (abdominal aortic, infrainguinal, or extra-anatomical); patients were ASA III or less and had no history of CHF | Oral metoprolol (50 mg for weight <75 kg or 100 mg for weight ≥75 kg) or placebo 2 hours before surgery; repeat dosing 2 hours after surgery; daily thereafter the study drug was given the same way twice a day until day 5 post-surgery or discharge from hospital if sooner; patients unable to take drugs orally were given metoprolol infusions of 0.2 mg/kg (15 mg maximum) or placebo every 6 hours | Day 30 post-surgery |

ASA=American Surgical Association classification; bpm=beats per minute; CAD=coronary artery disease; CHF=congestive heart failure; HR=heart rate; MAP=mean arterial pressure; MI=myocardial infarction; SBP=systolic blood pressure.

Quality assessment

Most randomised controlled trials fulfilled our quality measures (for example, all trials had complete patient follow-up). Table 2 reports the quality measures of the trials that failed to fulfil at least one of our markers of validity.19,22,33,35,36

Table 2.

Quality measures of randomised controlled trials that failed to fulfil any one of the markers of validity

| Trials | Concealment of randomisation | Trial stopped early | Patients blinded | Healthcare providers blinded | Data collectors blinded | Outcome assessors blinded |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liu19 | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Stone22 | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Poldermans33 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| Zaugg35 | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Urban36 | Yes | Yes | No | No, except anaesthesiologists | Yes | Yes |

Effect of perioperative β blockers

Table 3 presents the results of the meta-analyses. Overall only a moderate number of major perioperative cardiovascular events occurred (18 cardiovascular deaths, 58 non-fatal myocardial infarctions, and 7 non-fatal cardiac arrests).

Table 3.

Effect of perioperative β blockers within the first 30 days after non-cardiac surgery

| Outcome and trials | β blocker groups | Control groups | Risk reduction | 95% confidence interval | 99% confidence interval | I2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total mortality | ||||||

| Wallace31 | 4/99 | 2/101 | 2.04 | 0.38 to 10.89 | 0.23 to 18.43 | |

| Bayliff32 | 2/49 | 1/50 | 2.04 | 0.19 to 21.79 | 0.09 to 45.85 | |

| Poldermans33 | 2/59 | 9/53 | 0.20 | 0.05 to 0.88 | 0.03 to 1.41 | |

| Yang37 | 1/246 | 7/250 | 0.15 | 0.02 to 1.17 | 0.01 to 2.26 | |

| Total | 9/453 | 19/454 | 0.56 | 0.14 to 2.31 | 0.09 to 3.60 | 57% |

| Cardiovascular mortality | ||||||

| Wallace31 | 1/99 | 2/101 | 0.51 | 0.05 to 5.54 | 0.02 to 11.71 | |

| Bayliff32 | 2/49 | 1/50 | 2.04 | 0.19 to 21.79 | 0.09 to 45.85 | |

| Poldermans33 | 2/59 | 9/53 | 0.20 | 0.05 to 0.88 | 0.03 to 1.41 | |

| Yang37 | 0/246 | 1/250 | 0.34 | 0.01 to 8.27 | 0.01 to 22.59 | |

| Total | 5/453 | 13/454 | 0.40 | 0.14 to 1.15 | 0.10 to 1.60 | 0% |

| Non-fatal myocardial infarction | ||||||

| Jakobsen30 | 1/18 | 0/18 | 3.00 | 0.13 to 69.09 | 0.05 to 185.13 | |

| Poldermans33 | 0/59 | 9/53 | 0.05 | 0.00 to 0.79 | 0.00 to 1.93 | |

| Raby34 | 0/15 | 1/11 | 0.25 | 0.01 to 5.62 | 0.00 to 14.93 | |

| Zaugg35 | 0/43 | 3/20 | 0.07 | 0.00 to 1.26 | 0.00 to 3.15 | |

| Urban36 | 1/60 | 3/60 | 0.33 | 0.04 to 3.11 | 0.02 to 6.29 | |

| Yang37 | 19/246 | 21/250 | 0.92 | 0.51 to 1.67 | 0.42 to 2.01 | |

| Total | 21/441 | 37/412 | 0.38 | 0.11 to 1.29 | 0.08 to 1.88 | 45% |

| Non-fatal cardiac arrest | ||||||

| Wallace31 | 2/99 | 3/101 | 0.68 | 0.12 to 3.98 | 0.07 to 6.94 | |

| Bayliff32 | 0/49 | 2/50 | 0.20 | 0.01 to 4.14 | 0.00 to 10.67 | |

| Total | 2/148 | 5/151 | 0.50 | 0.11 to 2.29 | 0.07 to 3.70 | 0% |

| Major perioperative cardiovascular events* | ||||||

| Jakobsen30 | 1/18 | 0/18 | 3.00 | 0.13 to 69.09 | 0.05 to 185.13 | |

| Wallace31 | 3/99 | 5/101 | 0.61 | 0.15 to 2.49 | 0.10 to 3.88 | |

| Bayliff32 | 2/49 | 3/50 | 0.68 | 0.12 to 3.90 | 0.07 to 6.74 | |

| Poldermans33 | 2/59 | 18/53 | 0.10 | 0.02 to 0.41 | 0.02 to 0.64 | |

| Raby34 | 0/15 | 1/11 | 0.25 | 0.01 to 5.62 | 0.00 to 14.93 | |

| Zaugg35 | 0/43 | 3/20 | 0.07 | 0.00 to 1.26 | 0.00 to 3.15 | |

| Urban36 | 1/60 | 3/60 | 0.33 | 0.04 to 3.11 | 0.02 to 6.29 | |

| Yang37 | 19/246 | 22/250 | 0.88 | 0.49 to 1.58 | 0.41 to 1.90 | |

| Total | 28/589 | 55/563 | 0.44 | 0.20 to 0.97 | 0.16 to 1.24 | 42% |

| Non-fatal stroke | ||||||

| Wallace31 | 4/99 | 1/101 | 4.08 | 0.46 to 35.87 | 0.23 to 71.02 | NA |

| Congestive heart failure | ||||||

| Magnusson20 | 0/15 | 1/15 | 0.33 | 0.01 to 7.58 | 0.01 to 20.25 | |

| Jakobsen30 | 1/18 | 0/18 | 3.00 | 0.13 to 69.09 | 0.05 to 185.13 | |

| Wallace31 | 9/99 | 7/101 | 1.31 | 0.51 to 3.38 | 0.38 to 4.56 | |

| Bayliff32 | 8/49 | 4/50 | 2.04 | 0.66 to 6.34 | 0.46 to 9.05 | |

| Yang37 | 5/246 | 3/250 | 1.69 | 0.41 to 7.01 | 0.26 to 10.96 | |

| Total | 23/427 | 15/434 | 1.54 | 0.83 to 2.87 | 0.68 to 3.48 | 0% |

| Hypotension needing treatment | ||||||

| Colman16 | 1/27 | 0/15 | 1.71 | 0.07 to 39.65 | 0.03 to 106.39 | |

| Cucchiara17 | 5/37 | 5/37 | 1.00 | 0.32 to 3.17 | 0.22 to 4.55 | |

| Gibson21 | 1/21 | 0/19 | 2.73 | 0.12 to 63.19 | 0.04 to 169.63 | |

| Stone22 | 12/89 | 2/39 | 2.63 | 0.62 to 11.20 | 0.39 to 17.65 | |

| Miller27 | 1/30 | 0/15 | 1.55 | 0.07 to 35.89 | 0.02 to 96.36 | |

| Miller28 | 39/368 | 19/180 | 1.00 | 0.60 to 1.69 | 0.51 to 1.98 | |

| Davies29 | 6/20 | 11/20 | 0.55 | 0.25 to 1.19 | 0.20 to 1.52 | |

| Wallace31 | 13/99 | 13/101 | 1.02 | 0.50 to 2.09 | 0.40 to 2.62 | |

| Bayliff32 | 24/49 | 13/50 | 1.88 | 1.09 to 3.26 | 0.92 to 3.87 | |

| Yang37 | 114/246 | 84/250 | 1.38 | 1.11 to 1.72 | 1.03 to 1.84 | |

| Total | 216/986 | 147/726 | 1.27 | 1.04 to 1.56 | 0.97 to 1.66 | 6% |

| Bradycardia needing treatment | ||||||

| Cucchiara17 | 0/37 | 1/37 | 0.33 | 0.01 to 7.93 | 0.01 to 21.46 | |

| Liu19 | 0/16 | 1/14 | 0.29 | 0.01 to 6.69 | 0.00 to 17.86 | |

| Magnusson20 | 4/15 | 0/15 | 9.00 | 0.53 to 153.79 | 0.22 to 375.21 | |

| Stone22 | 10/89 | 0/39 | 9.33 | 0.56 to 155.41 | 0.23 to 376.09 | |

| McKenzie23 | 1/50 | 0/50 | 3.00 | 0.13 to 71.92 | 0.05 to 195.17 | |

| Jakobsen26 | 5/49 | 1/49 | 5.00 | 0.61 to 41.25 | 0.31 to 80.06 | |

| Davies29 | 12/20 | 8/20 | 1.50 | 0.79 to 2.86 | 0.64 to 3.50 | |

| Wallace31 | 2/99 | 1/101 | 2.04 | 0.19 to 22.14 | 0.09 to 46.84 | |

| Yang37 | 53/246 | 19/250 | 2.83 | 1.73 to 4.64 | 1.48 to 5.42 | |

| Total | 87/621 | 31/575 | 2.27 | 1.53 to 3.36 | 1.36 to 3.80 | 3% |

| Bronchospasm | ||||||

| Cucchiara17 | 1/37 | 0/37 | 3.00 | 0.13 to 71.34 | 0.05 to 193.10 | |

| Jakobsen18 | 1/10 | 0/10 | 3.00 | 0.14 to 65.90 | 0.05 to 173.99 | |

| MacKenzie23 | 0/50 | 1/50 | 0.33 | 0.01 to 7.99 | 0.01 to 21.69 | |

| Inada24 | 1/20 | 1/10 | 0.50 | 0.03 to 7.19 | 0.02 to 16.62 | |

| Leslie25 | 1/40 | 2/20 | 0.25 | 0.02 to 2.59 | 0.01 to 5.41 | |

| Jakobsen26 | 1/49 | 1/49 | 1.00 | 0.06 to 15.54 | 0.03 to 36.80 | |

| Miller28 | 4/368 | 2/180 | 0.98 | 0.18 to 5.29 | 0.11 to 8.99 | |

| Jakobsen30 | 1/18 | 1/18 | 1.00 | 0.07 to 14.79 | 0.03 to 34.47 | |

| Wallace31 | 3/99 | 0/101 | 7.14 | 0.37 to 136.46 | 0.15 to 344.84 | |

| Bayliff32 | 12/49 | 16/50 | 0.77 | 0.41 to 1.45 | 0.33 to 1.77 | |

| Yang37 | 4/246 | 1/250 | 4.07 | 0.46 to 36.11 | 0.23 to 71.74 | |

| Total | 29/986 | 25/775 | 0.91 | 0.55 to 1.50 | 0.47 to 1.75 | 0% |

NA=not applicable.

Composite outcome of cardiovascular death, non-fatal myocardial Infarction, and non-fatal cardiac arrest.

Perioperative β blockers did not show any statistically significant beneficial effects on any of the individual outcomes. Patients in four trials had fatal events.31-33,37 Nine deaths (five cardiovascular) occurred among the 453 patients randomised to β blocker treatment, compared with 19 deaths (13 cardiovascular) among the 454 patients randomised to placebo or standard care (relative risk 0.56, 95% confidence interval 0.14 to 2.31, 99% confidence interval 0.09 to 3.60 for total mortality; 0.40, 0.14 to 1.15, 0.10 to 1.60 for cardiovascular mortality).

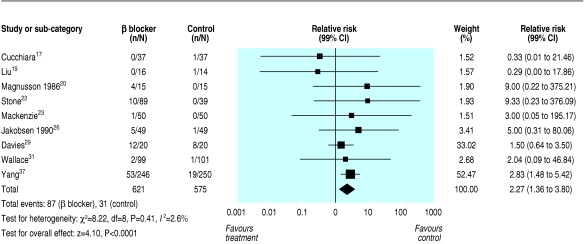

The individual safety outcomes in patients treated with perioperative β blockers showed a relative risk of 2.27 (1.53 to 3.36, 1.36 to 3.80) for bradycardia needing treatment (fig 2) and 1.27 (1.04 to 1.56, 0.97 to 1.66) for hypotension needing treatment. Both these analyses showed low heterogeneity (I2 of 3% for bradycardia needing treatment and 6% for hypotension needing treatment).

Fig 2.

Relative risks for bradycardia needing treatment

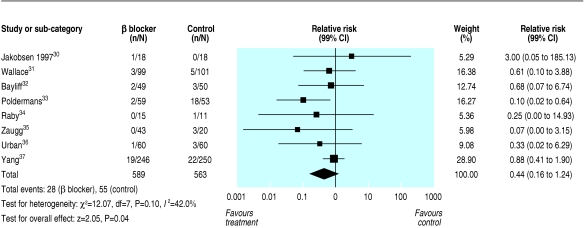

Eight trials had patients who had a major perioperative cardiovascular event (cardiovascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, or non-fatal cardiac arrest) (fig 3).30-37 Twenty eight major perioperative cardiovascular events occurred among the 589 patients randomised to β blocker treatment, compared with 55 among the 563 patients randomised to placebo or standard care (relative risk 0.44, 0.20 to 0.97, 0.16 to 1.24). Moderate heterogeneity existed across the trial results (I2 = 42%).

Fig 3.

Relative risks for major perioperative cardiovascular events (cardiovascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, or non-fatal cardiac arrest)

Exploring heterogeneity

Our a priori hypothesis related to trial validity helped to explain the heterogeneity. The three trials by Poldermans, Zaug, and Urban did not fulfil all our quality measures (these trials were stopped early after an interim analysis suggested a much larger than predicted treatment effect or there was no blinding of patients, healthcare providers, or data collectors) and their pooled relative risk for major perioperative cardiovascular events was 0.13 (0.04 to 0.38, 0.03 to 0.54) with I2 = 0%.33,35,36 The remaining five high quality trials had a pooled relative risk for major perioperative cardiovascular events of 0.82 (0.49 to 1.36, 0.42 to 1.59) with I2 = 0%.30-32,34,37

Reliability and conclusiveness of composite outcome result

To determine the optimal information size we assumed a 10% control event rate (the control event rate in our meta-analysis for the composite outcome) and a 25% relative risk reduction (the average relative risk reduction among the β blocker myocardial infarction trials38) with 80% power and a 0.01 two sided α. Our calculations indicated that the optimal information size needed to reliably detect a plausible treatment effect, for the composite outcome of major perioperative cardiovascular events, is 6124 patients. Currently, 1152 patients have been randomised in the β blocker randomised controlled trials with patients who have had a major perioperative cardiovascular event. We used the optimal information size to help to construct the Lan-DeMets sequential monitoring boundary (fig 4). The sequential monitoring boundary has not been crossed, indicating that the cumulative evidence is unreliable and inconclusive.

Fig 4.

Cumulative meta-analysis assessing the effect of perioperative β blockers on the 30 day risk of major perioperative cardiovascular events (cardiovascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, or non-fatal cardiac arrest) in patients having non-cardiac surgery. The Lan-DeMets sequential monitoring boundary, which assumes a 10% control event rate and a 25% relative risk reduction with 80% power and a two sided α=0.01, has not been crossed, indicating that the cumulative evidence is inconclusive

Discussion

Our results suggest that perioperative β blockers may decrease the risk of major perioperative cardiovascular events but increase the risk of bradycardia and hypotension needing treatment. These results, however, are based on only a moderate number of major perioperative cardiovascular events and patients with bradycardia needing treatment. A total of 1152 patients were randomised in the eight trials that had patients who had a major perioperative cardiovascular event. This number of patients randomised is much smaller than our calculated optimal information size (6124 patients, based on the 10% event rate in current trials) needed to reliably detect a plausible treatment effect of β blocker treatment in patients having non-cardiac surgery. Our use of methods adapted from formal interim monitoring boundaries applied to cumulative meta-analysis showed that the current evidence for perioperative β blocker is insufficient and inconclusive.

Strengths and weaknesses

Our systematic review has several strengths. We did a comprehensive search using seven strategies to identify randomised controlled trials, conducted eligibility decisions and data abstraction in duplicate and showed a high degree of agreement, obtained data from or confirmed them with all trialists, and evaluated the reliability and conclusiveness of the available evidence on perioperative β blockers through a method adapted from formal interim monitoring boundaries applied to cumulative meta-analysis.

Our systematic review focuses only on short term outcomes (within 30 days of surgery). It is possible that perioperative β blockers affect long term cardiovascular outcomes. Of all the randomised controlled trials we identified, only the trial by Mangano et al evaluated the effect of perioperative β blocker treatment on long term outcomes.39 This trial is the long term follow-up component of the trial by Wallace et al that is included in our review. The authors reported 30 deaths during the two year follow-up among the 200 patients randomised to atenolol or placebo for a maximum of seven postoperative days and a greater than 50% reduction in the relative risk of death among patients who received atenolol.39 These results, however, did not include the six deaths that occurred during the period when patients were receiving the study drug. When these events are appropriately included in the intention to treat analysis the reduction in the risk of death with atenolol is no longer statistically significant.10

Relation to other systematic reviews

A systematic review by Auerbach and Goldman and a systematic review and meta-analysis by Stevens et al have evaluated the effects of perioperative β blockers.40,41 The main difference between our systematic reviews is that we included a lot more trials and we used methods adapted from formal interim monitoring boundaries applied to cumulative meta-analysis to determine if the current evidence is reliable and conclusive.

Implications

Our systematic review provides encouraging evidence that perioperative β blockers may reduce the risk of major perioperative cardiovascular events but increase the risk of bradycardia and hypotension needing treatment in patients having non-cardiac surgery. Using a subset of the evidence we identified, several authors and the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines have recommended perioperative β blocker treatment for varying groups of patients having non-cardiac surgery.5-8,42 These recommendations warrant cautious interpretation.

Firstly, only a moderate number of events occurred in the perioperative β blocker trials (for example, 83 major perioperative cardiovascular events). Secondly, the evidence on perioperative β blockers from our meta-analyses suggests a large treatment effect (56% relative risk reduction in major perioperative cardiovascular events). This treatment effect, however, is inconsistent with the results of the β blocker trials in myocardial infarction and congestive heart failure that have randomised more than 50 000 patients and have shown moderate treatment effects (relative risk reductions of 15-35%).38,43-46 If perioperative β blockers prevent major perioperative cardiovascular events, they probably do so through suppressing adrenergic activity. Therefore, large treatment effects are unlikely, because a substantial number of perioperative cardiovascular pathogenic mechanisms that β blockers do not affect remain (increased platelet reactivity, plasminogen activator inhibitor I, factor VIII related antigen levels, and inflammation; decreased antithrombin III concentrations).47-50

Thirdly, the nominally statistically significant beneficial result of decreased major perioperative cardiovascular events with β blocker treatment showed moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 42%), which weakens the reliability of this finding. Furthermore, the relative risk estimate from the three trials with methodological limitations (stopped early for unexpected large treatment effects or failure to blind) was sixfold lower than that of the high quality trials that failed to show a statistically significant result. This finding is in contrast to the outcomes of bradycardia and hypotension needing treatment, which showed low heterogeneity, strengthening the reliability of these findings.

Fourthly, for a meta-analysis to provide definitive evidence it should fulfil at least the minimum standards expected of a well designed, adequately powered, and rigorously conducted single randomised controlled trial. In fact, the potential for additional biases (such as publication bias), heterogeneity in various features of the design and conduct of the included trials, and an inflated type I error rate (due to multiple looks at the data as trials are added) suggest that a higher level of scepticism is appropriate in interpreting a meta-analysis than a single randomised controlled trial. The question of whether a meta-analysis is definitive can be considered by using the logic of early stopping for a randomised controlled trial. The analogy to early stopping of a single trial would be a recommendation, on the basis of a meta-analysis, to stop doing further trials. Using this logic, criteria can be adduced for concluding that evidence is adequate to recommend that no further studies are needed.

Our calculated optimal information size needed to reliably detect a plausible treatment effect was 6124 patients, assuming a 10% event rate—with a lower event rate, which is more probable, a higher optimal information size is needed. Our meta-analysis, however, showed that the eight trials that had patients who had a major perioperative cardiovascular event included only 20% of this minimal sample size. Using the optimal information size we constructed a sequential monitoring boundary, and the cumulative meta-analysis has not crossed this monitoring boundary. If the data included in our meta-analysis were from a single randomised controlled trial at an interim analysis, insufficient evidence would exist to justify stopping the trial. The monitoring boundary therefore indicates that the cumulative evidence is inconclusive and further research is needed.

What is already known on this topic

Several authors and guidelines committees have advocated the use of β blockers in patients having non-cardiac surgery

The robustness of the evidence for this intervention has been questioned

What this study adds

Perioperative β blockers may decrease the risk of major perioperative cardiovascular events but increase the risk of bradycardia and hypotension needing treatment

The beneficial results, however, are based on only a moderate number of major events, and the findings depend on methodologically weak trials

Methods adapted from formal interim monitoring boundaries applied to cumulative meta-analysis show that the evidence for perioperative β blockers is insufficient and inconclusive

The evidence examined in our systematic review identifies the need and provides the impetus for a large adequately powered randomised controlled trial on perioperative β blockers to definitively establish the benefits and risks of such treatment. Such a trial, the perioperative ischemic evaluation (POISE) trial, which plans to recruit 10 000 patients, was recently initiated and has recruited more than 4000 patients in 18 countries to date. Clear evidence establishing the role of β blockers in patients having non-cardiac surgery awaits the results of such trials.

Supplementary Material

Appendices A and B are on bmj.com

Appendices A and B are on bmj.com

We thank all the authors of the randomised controlled trials of β blockers who confirmed and provided data related to their trials.

Contributors: PJD contributed to the concept and design, data acquisition, data analysis, and interpretation of the data; wrote the first draft of the manuscript; critically revised the manuscript; and gave final approval of the submitted manuscript. WSB, PT-LC, NHB, VMM, and C-JJ contributed to the concept and design, data acquisition, and interpretation of data; critically revised the manuscript; and gave final approval of the submitted manuscript. VMM contributed to the concept and design, data analysis, and interpretation of data; critically revised the manuscript; and gave final approval of the submitted manuscript. GHG, JCV, CSC, KL, MJJ, MB, AA, ABC, JWG, TS, HY, and SY contributed to the concept and design and interpretation of the data; critically revised the manuscript; and gave final approval of the submitted manuscript. PJD is the guarantor.

Funding: PJD is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research senior research fellowship award. WSB is the R Fraser Elliot Chair of Cardiac Anesthesia and is supported by the Toronto General and Western Foundations and the University Health Network, University of Toronto. PT-LC is supported by a Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute mentored clinician scientist award. JCV is supported by a Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada doctoral research award. VMM is a Mayo Foundation scholar. MB is supported by the Detweiler Fellowship from the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, and a Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, McMaster University, clinical scientist fellowship award. JWG is supported by a Department of Anesthesia, Oxford University, research fellowship award. SY holds an endowed chair of the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario and is a senior scientist of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Competing interests: PJD, WSB, PT-LC, NHB, GHG, JCV, CSC, KL, MJJ, VMM, AA, ABC, JWG, TS, HY, and SY are all members of the POISE trial. SY has received honorariums and research grants from AstraZeneca, which manufactures metoprolol CR.

References

- 1.Sametz W, Metzler H, Gries M, Porta S, Sadjak A, Supanz S, et al. Perioperative catecholamine changes in cardiac risk patients. Eur J Clin Invest 1999;29: 582-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parker SD, Breslow MJ, Frank SM, Rosenfeld BA, Norris EJ, Christopherson R, et al. Catecholamine and cortisol responses to lower extremity revascularization: correlation with outcome variables. Crit Care Med 1995;23: 1954-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Priebe HJ. Triggers of perioperative myocardial ischaemia and infarction. Br J Anaesth 2004;93: 9-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weissman C. The metabolic response to stress: an overview and update. Anesthesiology 1990;73: 308-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee TH. Reducing cardiac risk in noncardiac surgery. N Engl J Med 1999;341: 1838-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grayburn PA, Hillis LD. Cardiac events in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: shifting the paradigm from noninvasive risk stratification to therapy. Ann Intern Med 2003;138: 506-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palda VA, Detsky AS. Perioperative assessment and management of risk from coronary artery disease. Ann Intern Med 1997;127: 313-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eagle KA, Berger PB, Calkins H, Chaitman BR, Ewy GA, Fleischmann KE, et al. ACC/AHA guideline update for perioperative cardiovascular evaluation for noncardiac surgery—executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Update the 1996 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation for Noncardiac Surgery). J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;39: 542-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacka MJ, Schricker T, Warriner B, Boulton A, Hudson R. More conclusive large-scale trials necessary before recommending use of beta blockade in patients at risk. Anesth Analg 2004;98: 269, author reply 269-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swedberg K, Wedel H. Effect of atenolol on mortality and cardiovascular morbidity after noncardiac surgery. Evidence-Based Cardiovascular Medicine 1998;2: 33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pogue J, Yusuf S. Overcoming the limitations of current meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet 1998;351: 47-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whitehead A, Whitehead J. A general parametric approach to the meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Stat Med 1991;10: 1665-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7: 177-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327: 557-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pogue JM, Yusuf S. Cumulating evidence from randomized trials: utilizing sequential monitoring boundaries for cumulative meta-analysis. Control Clin Trials 1997;18: 580-93, discussion 661-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coleman AJ, Jordan C. Cardiovascular responses to anaesthesia: influence of beta-adrenoreceptor blockade with metoprolol. Anaesthesia 1980;35: 972-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cucchiara RF, Benefiel DJ, Matteo RS, DeWood M, Albin MS. Evaluation of esmolol in controlling increases in heart rate and blood pressure during endotracheal intubation in patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy. Anesthesiology 1986;65: 528-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jakobsen CJ, Grabe N, Christensen B. Metoprolol decreases the amount of halothane required to induce hypotension during general anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth 1986;58: 261-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu PL, Gatt S, Gugino LD, Mallampati SR, Covino BG. Esmolol for control of increases in heart rate and blood pressure during tracheal intubation after thiopentone and succinylcholine. Can Anaesth Soc J 1986;33: 556-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magnusson J, Thulin T, Werner O, Jarhult J, Thomson D. Haemodynamic effects of pretreatment with metoprolol in hypertensive patients undergoing surgery. Br J Anaesth 1986;58: 251-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gibson BE, Black S, Maass L, Cucchiara RF. Esmolol for the control of hypertension after neurologic surgery. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1988;44: 650-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stone JG, Foex P, Sear JW, Johnson LL, Khambatta HJ, Triner L. Myocardial ischemia in untreated hypertensive patients: effect of a single small oral dose of a beta-adrenergic blocking agent. Anesthesiology 1988;68: 495-500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mackenzie JW, Bird J. Timolol: a non-sedative anxiolytic premedicant for day cases. BMJ 1989;298: 363-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inada E, Cullen DJ, Nemeskal AR, Teplick R. Effect of labetalol or lidocaine on the hemodynamic response to intubation: a controlled randomized double-blind study. J Clin Anesth 1989;1: 207-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leslie JB, Kalayjian RW, McLoughlin TM, Plachetka JR. Attenuation of the hemodynamic responses to endotracheal intubation with preinduction intravenous labetalol. J Clin Anesth 1989;1: 194-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jakobsen CJ, Blom L, Brondbjerg M, Lenler-Petersen P. Effect of metoprolol and diazepam on pre-operative anxiety. Anaesthesia 1990;45: 40-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller D, Martineau R, Hull K, Hill J. Bolus administration of esmolol for controlling the hemodynamic response to laryngoscopy and intubation: efficacy and effects on myocardial performance. J Cardiothorac Anesth 1990;4: 31-6. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller DR, Martineau RJ, Wynands JE, Hill J. Bolus administration of esmolol for controlling the haemodynamic response to tracheal intubation: the Canadian multicentre trial. Can J Anaesth 1991;38: 849-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davies MJ, Dysart RH, Silbert BS, Scott DA, Cook RJ. Prevention of tachycardia with atenolol pretreatment for carotid endarterectomy under cervical plexus blockade. Anaesth Intensive Care 1992;20: 161-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jakobsen CJ, Bille S, Ahlburg P, Rybro L, Pedersen KD, Rasmussen B. Preoperative metoprolol improves cardiovascular stability and reduces oxygen consumption after thoracotomy. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1997;41: 1324-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wallace A, Layug B, Tateo I, Li J, Hollenberg M, Browner W, et al. Prophylactic atenolol reduces postoperative myocardial ischemia. Anesthesiology 1998;88: 7-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bayliff CD, Massel DR, Inculet RI, Malthaner RA, Quinton SD, Powell FS, et al. Propranolol for the prevention of postoperative arrhythmias in general thoracic surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 1999;67: 182-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poldermans D, Boersma E, Bax JJ, Thomson IR, van de Ven LL, Blankensteijn JD, et al. The effect of bisoprolol on perioperative mortality and myocardial infarction in high-risk patients undergoing vascular surgery. N Engl J Med 1999;341: 1789-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raby KE, Brull SJ, Timimi F, Akhtar S, Rosenbaum S, Naimi C, et al. The effect of heart rate control on myocardial ischemia among high-risk patients after vascular surgery. Anesth Analg 1999;88: 477-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zaugg M, Tagliente T, Lucchinetti E, Jacobs E, Krol M, Bodian C, et al. Beneficial effects from beta-adrenergic blockade in elderly patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology 1999;91: 1674-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Urban MK, Markowitz SM, Gordon MA, Urquhart BL, Kligfield P. Postoperative prophylactic administration of beta-adrenergic blockers in patients at risk for myocardial ischemia. Anesth Analg 2000;90: 1257-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang H, Raymer K, Butler R, Parlow J, Roberts R. Metoprolol after vascular surgery (MaVS). Can J Anesth 2004;51: A7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yusuf S, Peto R, Lewis J, Collins R, Sleight P. Beta blockade during and after myocardial infarction: an overview of the randomized trials. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 1985;27: 335-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mangano DT, Layug EL, Wallace A, Tateo I. Effect of atenolol on mortality and cardiovascular morbidity after noncardiac surgery. N Engl J Med 1996;335: 1713-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Auerbach AD, Goldman L. Beta-blockers and reduction of cardiac events in noncardiac surgery: scientific review. JAMA 2002;287: 1435-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stevens RD, Burri H, Tramer MR. Pharmacologic myocardial protection in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a quantitative systematic review. Anesth Analg 2003;97: 623-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Butterworth J, Furberg CD. Improving cardiac outcomes after noncardiac surgery. Anesth Analg 2003;97: 613-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.First International Study of Infarct Survival Collaborative Group. Randomised trial of intravenous atenolol among 16 027 cases of suspected acute myocardial infarction: ISIS-1. Lancet 1986;2: 57-66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lechat P, Packer M, Chalon S, Cucherat M, Arab T, Boissel JP. Clinical effects of beta-adrenergic blockade in chronic heart failure: a meta-analysis of double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trials. Circulation 1998;98: 1184-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.The cardiac insufficiency bisoprolol study II (CIBIS-II): a randomised trial. Lancet 1999;353: 9-13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Effect of metoprolol CR/XL in chronic heart failure: metoprolol CR/XL randomised intervention trial in congestive heart failure (MERIT-HF). Lancet 1999;353: 2001-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McDaniel MD, Pearce WH, Yao JS, Rossi EC, Fahey VA, Green D, et al. Sequential changes in coagulation and platelet function following femorotibial bypass. J Vasc Surg 1984;1: 261-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosenfeld BA, Beattie C, Christopherson R, Norris EJ, Frank SM, Breslow MJ, et al. The effects of different anesthetic regimens on fibrinolysis and the development of postoperative arterial thrombosis. Anesthesiology 1993;79: 435-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schillinger M, Domanovits H, Bayegan K, Holzenbein T, Grabenwoger M, Thoenissen J, et al. C-reactive protein and mortality in patients with acute aortic disease. Intensive Care Med 2002;28: 740-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Flinn WR, McDaniel MD, Yao JS, Fahey VA, Green D. Antithrombin III deficiency as a reflection of dynamic protein metabolism in patients undergoing vascular reconstruction. J Vasc Surg 1984;1: 888-95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.