Abstract

Objective To determine variability in interpretation of chest radiographs among tuberculosis specialists, radiologists, and respiratory specialists.

Design Observational study.

Setting Tuberculosis and respiratory disease services, Samara region, Russian Federation.

Participants 101 clinicians involved in the diagnosis and management of pulmonary tuberculosis and respiratory diseases.

Main outcome measures Interobserver and intraobserver agreement on the interpretation of 50 digital chest radiographs, using a scale of poor to very good agreement (κ coefficient: ≤ 0.20 poor, 0.21-0.40 fair, 0.41-0.60 moderate, 0.61-0.80 good, and 0.81-1.00 very good).

Results Agreement on the presence or absence of an abnormality was fair only (κ = 0.380, 95% confidence interval 0.376 to 0.384), moderate for localisation of the abnormality (0.448, 0.444 to 0.452), and fair for a diagnosis of tuberculosis (0.387, 0.382 to 0.391). The highest levels of agreement were among radiologists. Level of experience (years of work in the specialty) influenced agreement on presence of abnormalities and cavities. Levels of intraobserver agreement were fair.

Conclusions Population screening for tuberculosis in Russia may be less than optimal owing to limited agreement on interpretation of chest radiographs, and may have implications for radiological screening programmes in other countries.

Introduction

Clinical interpretation of chest radiographs is important in the control of tuberculosis.1 Studies have examined intraobserver and interobserver agreement in interpretation of chest radiographs,2-4 and significant disagreement between observers has been reported.5-9

Radiological examination plays an important part in the diagnosis and monitoring of tuberculosis, particularly in countries of the former Soviet Union such as the Russian Federation. The control of tuberculosis in Russia remains a challenge and an economic burden10 (incidence 86.0 per 100 000 population and mortality 21.5 per 100 000 population in 200211,12). Case finding is based on fluorographic screening of the population, and diagnosis may be made on the basis of radiological abnormalities without bacteriological confirmation.13,14 The monitoring of treatment, the definition of cure, and the granting of permission for patients with tuberculosis to return to work after therapy largely depend on the resolution of radiological abnormalities.15 In Russia the validity of interpretation of chest radiographs is essential if the benefits of screening and monitoring of treatment are to be realised. In public health terms, false positive diagnoses will result in inefficient use of resources, and false negative diagnoses may pose a threat to public health through spread of tuberculosis. Misdiagnosis of active tuberculosis as latent infection and subsequent use of single drug chemoprophylaxis may result in drug resistance.

We determined interobserver and intraobserver variability in interpretation of chest radiographs among a group of Russian clinicians from the disciplines of radiology, respiratory medicine, and tuberculosis.

Methods

Our study was carried out in Samara, a Russian city about 1000 km south east of Moscow (population 1.2 million). We invited to take part in our study all specialists in tuberculosis, respiratory physicians from the two main local general hospitals, radiologists specialising in tuberculosis, and general radiologists.

The study material consisted of 50 high resolution digital posterior-anterior chest radiographs, selected from the archives at King's College Hospital, London, which had a diagnosis—that is, they were interpretable. Thirty seven of the radiographs showed an abnormality and 13 were reported as normal. The 37 abnormal radiographs comprised 20 (54%) reported as tuberculosis, 7 (19%) reported as lung cancer, 5 (14%) reported as pneumonia, 4 (11%) reported as sarcoid, and 1 (3%) reported as fibrosing alveolitis. Twenty patients who were described as having tuberculosis on the basis of the chest radiograph were culture positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The remaining 17 people had culture negative results for tuberculosis.

To assess intraobserver agreement, we randomly repeated 10 pairs of radiographs in the set. The participants were familiar with the digital format, as both conventional film radiographs and digital radiographs are used in Russia. For general population screening, however, a small radiograph (fluorogram) is used, which has much poorer resolution than digital radiographs. We converted these series of digital images into a high resolution slide presentation (Microsoft Powerpoint), which was reviewed by each participant in a darkened room during a single viewing session, independently from the other participants. The participants were given unlimited time to familiarise themselves with images on the computer before they reviewed the radiographs. Abnormal and normal images were randomly mixed and each participant reviewed them in the same order. Each image was reviewed for two minutes, a period determined from a pilot study. This time also approximates to that spent reviewing images in population screening. No clinical information was provided, reflecting the normal situation of population screening. The participants were not allowed to review images they had already seen.

The participants recorded their interpretation of each radiograph on a structured questionnaire, using a five point scale16: 1 = normal; 2 = abnormal but not clinically important; 3 = not certain, warrants further diagnostic evaluation; 4 = abnormal diagnosis uncertain, warrants further diagnostic evaluation; and 5 = abnormal—diagnosis apparent but warrants appropriate clinical management.

The questionnaire also included categorical questions requiring yes or no answers on the localisation of an abnormality and the presence of cavities. The participants were asked whether the radiographic findings were consistent with a diagnosis of tuberculosis and, if so, which form (according to the Russian classification system) and whether it was likely to be active. If observers suspected another diagnosis, they were asked to state the most likely diagnosis as free text.

Statistical analysis

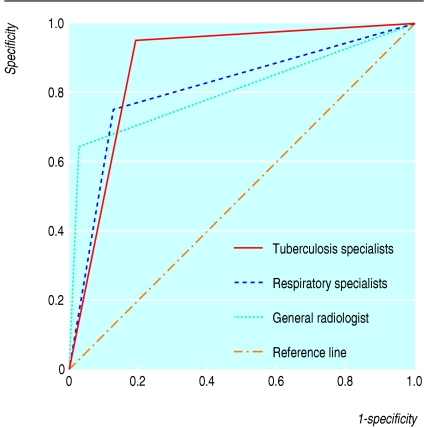

We generated a receiver operating curve for three subgroups: tuberculosis specialists, general radiologists, and respiratory specialists. To decrease the subjectivity of a single expert decision (for example, the UK radiologist or specialist who reported on the original chest radiograph) and to limit bias due to differences in professional practice between UK and Russian clinicians, we took a reference standard from a majority decision of the specialist radiologists on the question of whether the findings were consistent with tuberculosis. We used this standard to compare the performance of the other participants with that of the specialist radiologists. The participants were blind to the reference standard.

To assess interobserver agreement among the participants and within the three subgroups, we used κ statistics for multiple observers (κm), which is a measure of agreement beyond the level of agreement expected by chance alone. We also used κ statistics to measure intraobserver agreement between the two reports of radiographs that had been repeated. We adopted the guidelines for interpretation of κ coefficients from Altman: < 0.20, poor agreement; 0.21-0.40, fair agreement; 0.41-0.60, moderate agreement; 0.61-0.80 good agreement; and 0.81-1.00 very good agreement17; we also calculated 95% confidence intervals.18 By averaging the κ values of each lung zone, we calculated the mean interobserver and intraobserver κ statistics for localisation of an abnormality.

We analysed the data using Stata8, SAS release 8.2, and SPSS12.

Results

Overall, 61 of 80 (76%) tuberculosis specialists agreed to participate in our study, as did 15 of 18 (83%) respiratory specialists, all 12 specialist radiologists, and all 13 general radiologists (see table on bmj.com).

Overall agreement on the presence or absence of an abnormality on chest radiographs was fair only (κm = 0.380). Interobserver agreement was highest when we compared both normal findings and abnormal but not clinically important findings with the other responses (not certain, warrants further diagnostic evaluation; abnormal diagnosis uncertain, warrants further diagnostic evaluation; and abnormal—diagnosis apparent but warrants appropriate clinical management), although even then agreement was only moderate (0.479).

Agreement on localisation of abnormalities was moderate only (0.448; range 0.351-0.547) and agreement on determining a diagnosis of tuberculosis was fair only (0.387). For each of the 50 radiographs reviewed, tuberculosis was offered as a diagnosis by at least one participant. Agreement was highest among the radiologists, but still only moderate (0.448; table 1).

Table 1.

Agreement among Russian clinicians on evaluation of chest radiographs. Values are κ (95% confidence intervals)

| Radiographic finding | All participants | Tuberculosis specialists | Radiologists | Respiratory specialists |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinically important abnormality: | ||||

| Normal (category 1) versus any abnormality (categories 2-5)* | 0.380 (0.376 to 0.384) | 0.368 (0.361 to 0.374) | 0.497 (0.483 to 0.514) | 0.284 (0.257 to 0.311) |

| Categories 1 and 2 versus categories 3-5* | 0.479 (0.475 to 0.482) | 0.466 (0.459 to 0.472) | 0.564 (0.548 to 0.580) | 0.493 (0.466 to 0.520) |

| All five categories* | 0.217 (0.215 to 0.220) | 0.225 (0.221 to 0.229) | 0.252 (0.244 to 0.260) | 0.198 (0.187 to 0.209) |

| Localisation of abnormality†: | 0.448 (0.444 to 0.452) | 0.285 (0.278 to 0.291) | 0.503 (0.487 to 0.519) | 0.342 (0.315 to 0.369) |

| Left upper zone | 0.518 (0.514 to 0.522) | 0.168 (0.161 to 0.174) | 0.496 (0.480 to 0.512) | 0.458 (0.431 to 0.485) |

| Right upper zone | 0.547 (0.523 to 0.551) | 0.441 (0.434 to 0.447) | 0.525 (0.509 to 0.541) | 0.532 (0.504 to 0.559) |

| Left middle zone | 0.355 (0.351 to 0.359) | 0.567 (0.560 to 0.573) | 0.343 (0.327 to 0.359) | 0.283 (0.225 to 0.310) |

| Right middle zone | 0.351 (0.347 to 0.355) | 0.347 (0.340 to 0.353) | 0.331 (0.315 to 0.347) | 0.342 (0.315 to 0.369) |

| Left lower zone | 0.425 (0.421 to 0.429) | 0.356 (0.349 to 0.362) | 0.495 (0.479 to 0.512) | 0.265 (0.238 to 0.292) |

| Right lower zone | 0.378 (0.374 to 0.382) | 0.401 (0.395 to 0.408) | 0.510 (0.493 to 0.526) | 0.226 (0.199 to 0.253) |

| Presence of cavity | 0.433 (0.428 to 0.438) | 0.427 (0.420 to 0.435) | 0.565 (0.545 to 0.583) | 0.244 (0.213 to 0.275) |

| Radiographic findings consistent with tuberculosis | 0.387 (0.382 to 0.391) | 0.377 (0.367 to 0.385) | 0.448 (0.429 to 0.467) | 0.386 (0.355 to 0.416) |

| Form of tuberculosis‡ | 0.272 (0.264 to 0.280) | 0.272 (0.260 to 0.284) | 0.323 (0.301 to 0.345) | 0.199 (0.164 to 0.234) |

| Tuberculosis process active | 0.153 (0.124 to 0.164) | 0.119 (0.103 to 0.136) | 0.244 (0.195 to 0.293) | 0.041 (−0.029 to 0.110) |

Categories 1 and 2 reflect certainty that no clinically important abnormality present; categories 3 to 5 reflect some abnormality with clinical importance.

κ produced by averaging κ values for each radiological zone.

According to Russian classification: military, focal, caseous pneumonia, cavernous, cirrhotic, tuberculosis of mediastinal lymph nodes, infiltrative, disseminated, tuberculoma, fibrocavernous, pleuritis.

When we combined normal findings with abnormal but not clinically important findings, the more experienced participants showed greater agreement on presence or absence of abnormalities (0.388, 95% confidence interval 0.383 to 0.393 v 0.355, 0.316 to 0.353) and detection of cavities (0.450, 0.444 to 0.456 v 0.354, 0.331 to 0.376), but not when we took all five responses into account. Level of experience made little difference to agreement on localisation of an abnormality and tuberculosis as a diagnosis.

We analysed agreement between the general radiologists and the specialist radiologists separately. The specialist radiologists showed higher levels of agreement on the four main questions posed: is a clinically important abnormality present, is a cavity present, are radiographic findings consistent with tuberculosis, and is the tuberculosis active? Based on this finding the “majority decision” of the tuberculosis radiologists on the question of whether the chest radiographs were consistent with tuberculosis or not was recorded and taken as a reference standard against which we created a receiver operating curve to compare the performance of other participants against the performance of tuberculosis radiologists (figure). The areas under the receiver operating curve were: tuberculosis specialists, 0.88 (95% confidence interval 0.78 to 0.98); respiratory specialists, 0.81 (0.68 to 0.94); and general radiologists, 0.81 (0.67 to 0.95), illustrating no statistically significant variation in the performance of respiratory specialists or general radiologists from the reference opinion of whether the chest radiograph showed possible tuberculosis. The majority opinion of tuberculosis specialists was significantly closer to the opinion of the reference group than to the opinions of the other two groups.

Figure 1.

Receiver operating curve for the question “Are findings consistent with tuberculosis?”

Intraobserver agreement for all responses on repeated radiographs was fair to moderate only (table 2). The radiologists had the highest levels of agreement (moderate to good; κ range 0.529-0.627).

Table 2.

Intraobserver agreement among Russian clinicans on evaluation of chest radiographs. Values are κ (95% confidence intervals)

| Radiographic finding | All participants | Tuberculosis specialists | Radiologists | Respiratory specialists |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of clinically important abnormality all five categories | 0.457 (0.004 to 0.911) | 0.456 (−0.036 to 0.949) | 0.604 (0.347 to 0.861) | 0.292 (−0.141 to 0.725) |

| Localisation of abnormality* | 0.477 (−0.009 to 1.044) | 0.473 (−0.081 to 1.026) | 0.627 (0.143 to 1.110) | 0.277 (−0.280 to 0.834) |

| Presence of cavity | 0.358 (−0.595 to 1.311) | 0.443 (−0.202 to 1.089) | 0.594 (−0.205 to 1.393) | 0.448 (−0.244 to 1.140) |

| Radiographic findings consistent with tuberculosis | 0.493 (−0.03 to 1.016) | 0.481 (−0.019 to 0.981) | 0.529 (−0.042 to 1.100) | 0.483 (−0.078 to 1.044) |

| Form of tuberculosis† | 0.488 (−0.073 to 1.050) | 0.448 (−0.074 to 0.970) | 0.611 (0.021 to 1.220) | 0.449 (−0.144 to 1.042) |

| Tuberculosis process active | 0.490 (−0.098 to 1.078) | 0.471 (−0.097 to 1.039) | 0.546 (−0.158 to 1.250) | 0.470 (0.015 to 0.927) |

Average of κ values for each radiological zone.

According to Russian classification: military, focal, caseous pneumonia, cavernous, cirrhotic, tuberculosis of mediastinal lymph nodes, infiltrative, disseminated, tuberculoma, fibrocavernous, pleuritis.

Between doctors with less than five years' experience and those with five or more years' experience, the largest difference in intraobserver agreement was in assessing whether an abnormality was present (0.423 v 0.465). Experience did not seem to play an important part in interobserver agreement for presence of abnormalities (0.215 v 0.219), being low overall.

Discussion

The interpretation of chest radiographs by Russian clinicians involved in the screening for and treatment of tuberculosis in Samara region is highly subjective and agreement was often low.

As Samara is a typical Russian city we believe that our findings may be generalisable throughout the Russian Federation. Levels of agreement were similar to other reports,2,5,8,19-23 but these studies were not carried out in settings where mass population screening is routine practice, nor in a post-Soviet environment. Moreover, these studies included radiologists whose opinion may have been influenced by that of work colleagues.

In our study, professional experience had some influence on the ability to detect abnormalities, including cavities, which may be a prerequisite for any successful method for screening populations. In general, the effect of professional professional seniority on levels of diagnostic agreement was limited. Intraobserver agreement was not high overall, with radiologists showing most consistency in agreeing with their previous opinions on chest radiographs.

The effectiveness of the Russian model of screening (general population screening is mandatory and annual targets are set) depends highly on the validity of the tools used (radiology) and the interpretation of findings. Given the relatively low intraobserver and interobserver agreement we found in the interpretation of chest radiographs by Russian clinicians, the implications are profound. A significant number of the general population may be wrongly told that they have tuberculosis, as the probability is extremely low. This has repercussions both for the individual and for the tuberculosis programme, as considerable scarce resources (budget expenditure and professionals' time) may be used to exclude a diagnosis of tuberculosis. Under-capacity in microbiological laboratory services (the case in much of Russia, but not in Samara) means that refuting a putative diagnosis of tuberculosis is prone to error. It seems likely that many people are potentially wrongly diagnosed as having tuberculosis. Moreover, many patients with tuberculosis may not be identified.

Our study was limited in two ways. Firstly, owing to the small number of chest radiographs selected for second review, the κ values for intraobserver agreement had wide and statistically insignificant confidence intervals. Secondly, the presence and type of abnormality was based on only one plain posterior-anterior chest radiograph. Therefore care should be taken in extrapolating results to routine clinical practice if clinical history, results of physical examination, and other radiographs are available. In practice, people being screened are likely to be asymptomatic and therefore radiographs would be interpreted with little supporting clinical information.

What is already known on this topic

Radiological screening is an important tool in diagnosing tuberculosis

What this study adds

The interpretation of chest radiographs among health professionals is limited

In the absence of symptoms, population screening programmes for tuberculosis have a low positive predictive value

Given the limited resources of the Russian health system and for tuberculosis in particular, economic studies that assessed the cost effectiveness of screening using digital radiographs compared with no screening or screening of risk groups would be of value. We did not compare the performance of Russian radiologists with that of British radiologists.

Our study highlights the subjective nature of interpreting radiographs and the problems that such subjectivity has on management decisions for patients and on the effectiveness of an active post-Soviet screening programme. Clinical diagnoses and monitoring of progress should, whenever possible, be supported by the submission of pathological material for bacteriological or molecular examination.

We assessed the effectiveness of a screening programme provided by radiologists in Samara region. This region has an adult population of two million and an estimated prevalence of tuberculosis of 80 per 100 000. The positive predictive value (assuming sensitivity of 63% and specificity of 97%) is likely to be in the order of 1.7%; a maximum of 60 000 people without tuberculosis potentially would be subjected to unnecessary further investigations.

Our findings are relevant for developed countries. Although population screening programmes in countries such as the United Kingdom and United States have been largely abandoned, they are now considering screening certain at risk groups (for example, prisoners, homeless asylum seekers). The recent introduction of a mobile x ray unit in London means that the United Kingdom may have embarked on a resource intensive method, which requires careful evaluation if, as with the Russian system, it is not to divert resources from more established strategies for the diagnosis of tuberculosis. The Russian government should be strongly advised to revise their screening policy and make better use of limited healthcare resources.

Supplementary Material

Table showing levels of experience is on bmj.com

Table showing levels of experience is on bmj.com

We thank Ekaterina Dodonova for statistical advice and R D Barker for help in selecting radiographs.

Contributors: FD and RC developed the original concept. FD, RC, and YB designed the study. YB, IF, SZ, NK, and FD implemented the study. YB collected the data. YB, RC, SP, and FD analysed the data. YB, RC, and FD drafted the paper and all authors contributed to the interpretation, editing, and final draft of the paper. FD is guarantor.

Funding: UK Department for International Development and a European Respiratory Society fellowship to YB.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Not required.

References

- 1.Pillay V, Swingler G, Matchaba R, Volmink J. Evidence for action? Patterns of clinical and public health research on tuberculosis in South Africa, 1994-1998. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2001;5: 946-51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albaum MN, Hill LC, Murphy M, Li YH, Fuhrman CR, Britton CA, et al. Interobserver reliability of the chest radiograph in community-acquired pneumonia. PORT Investigators. Chest 1996;110: 343-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brealey S. Measuring the effects of image interpretation: an evaluative framework. Clin Radiol 2001;56: 341-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tudor GR, Finlay D, Taub N. An assessment of inter-observer agreement and accuracy when reporting plain radiographs. Clin Radiol 1997;52: 235-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alland D, Kalkut GE, Moss AR, McAdam RA, Hahn JA, Bosworth W, et al. Transmission of tuberculosis in New York city. An analysis by DNA fingerprinting and conventional epidemiologic methods. N Engl J Med 1994;330: 1710-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaw NJ, Hendry M, Eden OB. Inter-observer variation in interpretation of chest X-rays. Scott Med J 1990;35: 140-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quekel LG, Kessels AG, Goei R, van Engelshoven JM. Detection of lung cancer on the chest radiograph: a study on observer performance. Eur J Radiol 2001;39: 111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coblentz CL, Babcook CJ, Alton D, Riley BJ, Norman G. Observer variation in detecting the radiologic features associated with bronchiolitis. Invest Radiol 1991;26: 115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coker R. Migration, public health and compulsory screening for TB and HIV. Asylum and migration working paper 1. London: Institute for Public Policy Research, 2003.

- 10.WHO, Division of emerging and other communicable diseases surveillance and control strategic plan 1996-2000. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- 11.Erokhin VV, Demikhova OV, Punga VV, Putova EV. [New organizational forms of antituberculosis care under present conditions. Results and experience exchange of work in pilot regions. Scientific and practical conference, Moscow, Sept 25-27, 2002]. Probl Tuberk 2003: 48-50. [PubMed]

- 12.Drobniewski F, Balabanova Y, Ruddy M, Fedorin I, Melentyev A, Mutovkin E, et al. Medical and social analysis of prisoners with tuberculosis in a Russian prison colony: an observational study. Clin Infect Dis 2003;36: 234-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drobniewski F, Tayler E, Ignatenko N, Paul J, Connolly M, Nye P, et al. Tuberculosis in Siberia 2. Diagnosis, chemoprophylaxis and treatment. Tuber Lung Dis 1996;77: 297-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coker RJ, Dimitrova B, Drobniewski F, Samyshkin Y, Balabanova Y, Kuznetsov S, et al. Tuberculosis control in Samara Oblast, Russia: institutional and regulatory environment. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2003;7: 920-32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prikaz (Order). On improvement of TB control activities in the Russian Federation. Moscow, Russia: Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, 21 March 2003. (No 109.)

- 16.Potchen EJ, Cooper TG, Sierra AE, Aben GR, Potchen MJ, Potter MG, et al. Measuring performance in chest radiography. Radiology 2000;217: 456-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Altman D. Practical statistics for medical research. London: Chapman and Hall, 1991.

- 18.Brealey S, Scally AJ. Bias in plain film reading performance studies. Br J Radiol 2001;74: 307-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Du Toit G, Swingler G, Iloni K. Observer variation in detecting lymphadenopathy on chest radiography. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2002;6: 814-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tudor GR, Finlay DB. Error review: can this improve reporting performance? Clin Radiol 2001;56: 751-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kwong JS, Carignan S, Kang EY, Muller NL, FitzGerald JM. Miliary tuberculosis. Diagnostic accuracy of chest radiography. Chest 1996;110: 339-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dhingsa R, Finlay DB, Robinson GD, Liddicoat AJ. Assessment of agreement between general practitioners and radiologists as to whether a radiation exposure is justified. Br J Radiol 2002;75: 136-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zitting AJ. Prevalence of radiographic small lung opacities and pleural abnormalities in a representative adult population sample. Chest 1995;107: 126-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.