Highlights

This study explores the multifaceted determinants of childhood obesity (CO) in Iran through stakeholder perspectives. It identifies key local, national, and international factors, including family and school environments, governance issues, social structures, and global influences like WHO’s ECHO program and political sanctions. The study emphasizes the need for comprehensive policy reforms, stakeholder collaboration, and cultural and environmental changes to control CO in Iran effectively.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-024-21221-1.

Keywords: Childhood, Obesity, Weight control, Policy, Qualitative study, Low-and-middle income countries

Abstract

Background

Despite significant global efforts to control childhood obesity (CO), its prevalence continues to rise, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. This study aims to identify the determinants of CO in Iran.

Methods

This qualitative study employed a purposive snowball sampling method to interview 30 stakeholders from various specialities and disciplines. They included scientists, government and industry authorities, representatives from international organizations, and members of civil society. The data analysis was conducted using MAXQDA 2020, employing inductive content analysis. The credibility and dependability of the data were ensured by using Lincoln and Guba’s criteria. We used the consolidating criteria for reporting qualitative studies.

Results

The main determinants of childhood obesity control in Iran can be categorized into three levels: local, national, and international. At the local level, home and school environments are influential in shaping unhealthy lifestyles and energy imbalances. The national determinants are the triad of governance, dominant social structure, and national policies/regulations. Governance factors such as inappropriate policy-making processes, Low responsiveness and accountability, and Low collaboration and parallel working between stakeholders; impact childhood obesity control. Dominant social structures including cultural norms, urban design, air pollution, social transitions, and inequalities also contribute to the issue. National policies and regulations exhibit shortcomings in fiscal and food promotion aspects. At the international level, the World Health Organization’s approach to Ending Childhood Obesity (ECHO), trade policies, political sanctions, climate change, and the COVID-19 pandemic have significant implications for childhood obesity control.

Conclusion

This study provides valuable insights into the determinants of childhood obesity (CO) in Iran. It can inform evidence-based policymaking not only in Iran but also in other countries with similar socio-economic statuses.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-024-21221-1.

Background

The global prevalence of childhood obesity (CO) is on the rise. World Health Organization (WHO) reported that in 2000, 33.3 million children (5.4%) under five were overweight. This number had risen to 38.9 million (5.7%) in 2020. Additionally, in 2020, 150 million children aged 5–19 years were obese [1, 2]. Projections estimate that by 2030, 39.8 million children under five and 254 million children aged 5–19 years will be obese. Alarmingly, nearly 50% of overweight children live in Asia, and 25% are in Africa [1]. The prevalence of obesity in children showed a 1.5-fold increase from 2012 to 2023 [3].The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the prevalence of obesity in children, intensifying these challenges. This could be attributed to reduced physical activity resulting from school closures and prolonged periods spent at home due to quarantine [4, 5].

Excessive weight gain during childhood significantly increases the risk of developing infections and chronic conditions such as cancer and cardiovascular disease [6–9]. Additionally, overweight children are more prone to bone and joint problems and experience a decreased quality of life. They also face social discrimination, leading to lower self-esteem and a higher risk of depression [10, 11]. What’s more, overweight children tend to exhibit lower academic achievements and reduced economic productivity later in life [10]. As a result, it is of utmost importance to prioritize initiatives aimed at controlling CO during these difficult times [4, 5].

Reliable national data on the prevalence of CO in low- and middle-income countries are limited. However, the available evidence suggests a significant and concerning increase in recent years [10, 12]. Iran, a middle-income country in the Middle East, has undergone a notable nutritional transition over the past few decades. According to the “Childhood and Adolescence Surveillance and Prevention of Adult Non-communicable Disease” (CASPIAN VI) study, more than 9.7% of Iranian school-age children are classified as overweight, with 11.9% classified as obese [13]. It is noteworthy that excess Body Mass Index has been estimated to contribute to 39.5% of total deaths in Iran [14].

Numerous efforts have been undertaken in Iran to address CO. The country has implemented action plans recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO), such as the Global Action Plan to Combat Non-communicable Diseases [15], as well as the Ending Childhood Obesity (ECHO) recommendations [16]. Furthermore, reforms are being pursued in food labelling, taxes, and subsidies to promote healthier food choices [17]. However, the persistent increase in obesity rates across various socioeconomic and geographic contexts [18] highlights the failure to effectively manage CO in Iran. To bring about substantial change in this issue, it is crucial to investigate the underlying causes of CO and identify the obstacles hindering its control [19].

Indeed, obesity is a critical challenge to achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and hinders global health and development. A better understanding of the local context is needed for better policy development and implementation of CO control. Unfortunately, there is a scarcity of data on successful policies targeting CO in low- and middle-income countries [20]. Moreover, policies cannot be blindly extrapolated from high-income countries or even countries with similar economic conditions to another nation [10]. Therefore, it is imperative to have a profound understanding of the local environment and identify barriers and facilitators specific to each country, before developing interventions. Furthermore, studies indicate that despite the increasing recognition of CO as a public health threat, our understanding of several factors, particularly environmental risk factors, remains limited [20, 21].

Given the aforementioned, it is clear that a thorough understanding of the determinants of CO is essential for improving CO management in Iran. Moreover, it is crucial to consider the viewpoints of diverse stakeholders, as this increases the likelihood of better policy development and implementation. While a limited number of studies have explored the barriers and facilitators of healthy lifestyles and weight management from the perspectives of parents or children [22–25], there is currently no study that comprehensively investigates this issue from the standpoint of all stakeholders across the country. Conducting such a study would serve as a valuable resource in addressing why Iranian efforts to control CO have not yielded tangible outcomes.

Methods

Participants and data collection

This qualitative study used an inductive thematic content analysis approach to investigate contextual factors’ interaction with CO in Iran. We used purposive snowball sampling to interview 30 stakeholders from different specialities and disciplines. These stakeholders were considered important for childhood obesity control based on the WHO Ending Childhood Obesity initiative and other reviewed programs and reports. We applied the purposive snowball sampling method, where each interviewee guided us to the next. We aimed to interview subjects with more than ten years of experience who were well-integrated into the system and had up-to-date data. They were involved in national programs related to children’s health across various areas such as schools, city environments, family and home environments, industries, and markets. The participants included university experts, government members, civil society representatives, industry professionals, and members from international organizations. The complete profile of the interviewees is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristic of interviewees

| Group | # | Organization | age | sex | Years of experiences | Position | Specialty | Code1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academic member | 1 | University A in Tehran | 50–60 | Male | 20+ | Full professor | Epidemiology | AE |

| 2 | University A in Tehran | 80–90 | Male | 50+ | Full professor | Community Nutrition | AN1 | |

| 3 | University B in Tehran | 60–70 | Female | 30+ | Full professor | Community Nutrition | AN2 | |

| 4 | Research Institute A in Tehran | 40–50 | Female | 20+ | Researcher | Community Nutrition | AN3 | |

| 5 | University A in Tehran | 70–80 | Male | 40+ | Full professor | Health management | AM | |

| 6 | University B in Tehran | 60–70 | Male | 20+ | Assistant professor | Food science and technology | AF | |

| 7 | University A in Tehran | 50–60 | Male | 10+ | Associate professor | Sociology | AS1 | |

| 8 | University C in Tehran | 50–60 | Male | 20+ | Associate professor | Sociology | AS2 | |

| 9 | Research Institute B in Tehran | 40–50 | Female | 10+ | Assistant professor | Physical education | AP | |

| 10 | University A in Isfahan | 60–70 | Female | 30+ | Full professor | Pediatrics and clinician | AC | |

| 11 | university A in Tehran | 40–50 | Female | 10+ | Associate professor | Health economy | AEC | |

| State organization | 12 | Institute of Standards and Industrial Research | 60–70 | Female | 30+ | Administrator in a province | Food Technology | ISIR |

| 13 | Ministry of Education | 40–50 | Female | 20+ | An expert in health administers | Education | Edu1 | |

| 14 | 50–60 | Male | 30+ | An administrator in Mazandaran province | Education | Edu2 | ||

| 15 | 50–60 | Male | 20+ | An administrator in Kerman province | Education | Edu3 | ||

| 16 | 40–50 | Female | 10+ | A health worker in Tehran province | Nutrition Science | Edu4 | ||

| 17 |

Secretariat of the Supreme Council for Health and Food Security |

50–60 | Female | 20+ | An expert | Physician | SSCHF | |

| 18 | Ministry of Health and Medical Education (MoHME) | 50–60 | Female | 30+ | An administrator | Community Nutrition | MoHME1 | |

| 19 | 50–60 | Female | 20+ | An administrator | Physician | MoHME2 | ||

| 20 | 50–60 | Female | 20+ | An administrator | Pediatrician | MoHME3 | ||

| 21 | Food and Drug Administration | 40–50 | Female | 10+ | A clerk | Food technology | FD | |

| 22 | Health administers in the Municipality | 40–50 | Female | 20+ | A clerk | Management | M | |

| 23 | Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting | 50–60 | Male | 20+ | administrator A | Physician | IRIB1 | |

| 24 | 50–60 | Female | 20+ | administrator B | Paediatrician | IRIB2 | ||

| 25 | Ministry of Interior | 40–50 | Male | 10+ | An administrator of a health program | Urban planning | MN | |

| Industrial company | 26 | Food Industry | 50–60 | Male | 20+ | Manager A | Food industry | FI1 |

| 27 | 60–70 | Male | 30+ | Manager B | Management | FI2 | ||

| Non-profit organization | 28 | A nonprofit organization on health education | 70–80 | Female | 40+ | Manager | Nutrition | NPO |

| International organization | 29 | International organization A | 40–50 | Female | 10+ | An expert in the Iran office | Public health in nutrition | INO1 |

| 30 | International organization B | 50–60 | Male | 20+ | An expert in the Iran office | NCD control | INO2 |

1codes have been assigned using the first letter of each interviewee’s group and specialty

The main investigator drafted the interview guide after reviewing other countries’ studies and CO control programs. Then, other team members discussed and modified the guide in several meetings. The revised guide was tested in two pilot interviews with two academic members other than the original research team. After approving the interview guide, 30 semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted between November 25, 2019, and August 5, 2020. The main investigator contacted various stakeholders to explain the purpose and process of the project. A specified time was scheduled if they agreed to participate in the interview. Only two stakeholders refused to be interviewed.

The interviewer has over 14 years of experience as a researcher, with a background in community nutrition. She was a PhD candidate in food policy at the time of the interviews. She is trained in qualitative research and skilled in conducting interviews. The interviews lasted between 30 and 90 min. These interviews were conducted using a semi-structured interview guide, including open and follow-up questions based on the participants’ answers and positions. Most interviews were conducted privately and in person at the participants’ offices. Due to the quarantine caused by COVID-19 in the middle of the study, five telephone interviews and one Skype interview were conducted. None of the interviews were repeated. During the in-depth interviews, the interviewee’s non-verbal signs, reactions, and main points of view were noted by the interviewer and included in the data analysis. All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. The consolidating criteria for reporting Qualitative Study were applied to performed and reporting findings [26]. The COREQ-32 item checklist is provided in the supplementary Table S1.

Data analysis

We used inductive thematic content analysis. Before the new interview, the previous interviews were reviewed, and, if necessary, the interview guide was modified to explore the newly raised issues in more depth [27]. Interviews continued until at least one representative from all stakeholder categories was included, and new interviews did not provide additional information on the topic under investigation [27]. We tried to interview several stakeholders with different perspectives to understand all the unknown determinants of CO control in Iranian children.

The primary researcher read the text and notes of the interviews and listened to the audio tape several times. Further analyses were performed using MAXQDA 2020 for the open, axial, and selective coding phases. The corresponding author (PA) reviewed one-third of the interviews to control the coding. In case of any disagreement, the research team discussed emerging themes and, after the agreement, began to categorize the open codes into subgroups. Finally, the conceptual model of the main determinants of CO in Iran has been developed. The entire team discussed and modified the conceptual framework in several meetings. It was then presented in two discussion sessions, in the presence of the interviewees, new participants from universities, and representatives from related organizations. These and the subsequent steps of the project were fully reported elsewhere [28].

Data trustworthiness

To ensure validity, we applied a valid qualitative study approach [29]. In this way, a detailed description of the study process is provided at each stage. Also, the validity and consistency of the data were confirmed by long and in-depth interactions with the participants and review by faculty members. Interviews with all stakeholders, including faculty members, food industry managers, various government executives, and civil society, provide the maximum diversity of the participants. It increases the relevance and validity of the results and enhances the potential to clarify the research question from multiple perspectives. The continuous presence of the primary interviewer in all interviews and spending enough time to collect detailed data can guarantee validity to some extent. Expert validation of the interview guide improved the accuracy of the study. The researchers’ characteristics are shown in Table 2. Five faculty members reviewed the study’s methods and findings to demonstrate trustworthiness and reliability. The main results were reviewed by stakeholders who did not participate in the interviews, and they confirmed the validity of the findings.

Table 2.

Characteristic of the researchers

| Initial of authors | Occupation at the time of study | Credentials | Experience and training | Establishment of the relationship before the study | Role in Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FT | Researcher | Ph.D. | Food policy | Yes | Designing the study, Interviewing, conducting data analysis, drafting the manuscript |

| PA | Full Professor, Director of the research center | Ph.D. | Health education and promotion | Yes | Supervising the thematic analysis, re-illustrating the visual figures, and critically revising and finalizing the manuscript |

| HP | Associate Professor | Ph.D. | Community Nutrition | Yes | Consulting the study and editing the article |

| AT | Full Professor, Dean of the department | MD MPH PhD | Health policy | Yes | Designing the study, supervised the study and the extraction of themes and model |

Results

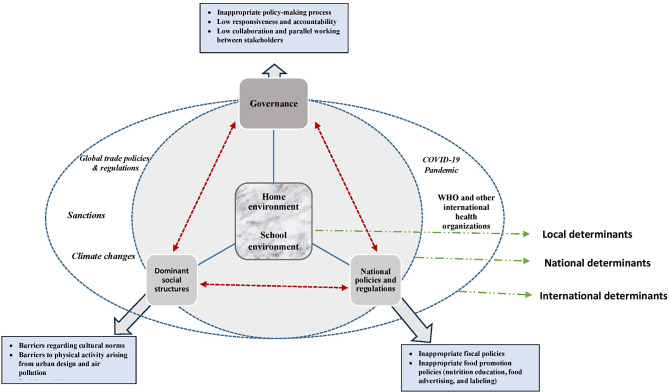

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual framework highlighting the key determinants of CO control in Iran from the stakeholders’ perspective. This study identifies determinants at three distinct levels: local, national, and international. At the local level, the study shows the influence of family and schools and their interplay in contributing to energy imbalance among children and adolescents. Additionally, it recognizes governance, social structure, and national policies/laws as fundamental factors at the national level, which are closely interconnected and mutually influential. Furthermore, the findings show the partial impact of the international environment on the overall structure.

Fig. 1.

Interrelation of local, national and international barriers predisposing children to excessive weight gain in Iran

In the following sections, we explain the framework in depth. A brief introduction to the participants is shown in Table 1, and we have referred to them in the text and tables with their assigned codes. The characteristics of the research team are described in Table 2. The structure of themes, sub-themes, codes, and representative quotes from participants, are provided in Supplementary Tables S2–S4.

Level 1. Local determinants

Nearly all participants emphasized that children cannot shape their behavior in isolation and are significantly influenced by their surroundings. They highlighted the detrimental impact of excessive exposure to advertisements and various environmental constraints on children’s behavior. The participants also noted that children today experience significant stress due to school pressure and unstable environments, which affects their food choices and weight status. Most local factors can be categorized as home and school environments, which will be discussed in detail in the subsequent sections. Some examples of participants’ quotes related to local environment determinants are presented in Supplementary Table S2.

Home environment

Stakeholders emphasized the crucial role of the family as the primary determinant of a child’s behavior during the early years, shaping their preferences and attitudes. Parents were highlighted as significant in providing food and influencing a child’s nutritional status through their knowledge of healthy eating and economic access. Several participants observed a prevailing belief in Iranian families that an obese child is considered healthy, and being overweight is sometimes deemed desirable, particularly in disadvantaged areas. Additionally, active children are sometimes viewed as abnormal. Some participants expressed that the low level of physical activity within families is not due to limited access to equipment, as activities such as walking or running can be done without any equipment. They further noted that families limit children’s physical activity from infancy, preventing them from running or engaging in any physical activity due to fear of injury. Furthermore, parents often prioritize academic performance and preparing children for university entrance exams, neglecting the importance of sports. The excessive emphasis on entrance exams was identified as a significant barrier to children’s health in Iran.

School environment

Participants highlighted the significance of ensuring access to nutritious food and appropriate physical activity equipment within schools by effective interventions, recognizing that children spend a significant portion of their active hours there. However, they expressed disappointment over the insufficient physical activity equipment in many schools and the tendency of teachers to restrict physical activity due to concerns about potential injuries. Additionally, several participants said that teachers prioritize theoretical lessons and focus on preparing students for university entrance exams, reflecting the primary concerns of parents.

Academic experts highlighted the influence of peers on children, particularly teenagers, within the school setting. Therefore, they emphasized the importance of comprehensive health education in schools to shape children’s behavior effectively. Participants noted that healthy lifestyle education is not effectively integrated into the curriculum in Iranian schools. Furthermore, they highlighted the easy accessibility of unhealthy junk food within school premises.

Health experts pointed out the critical role of kindergartens and childcare centers in the control of CO. However, they expressed concern that Iranian children primarily remain at home until the age of six, which limits opportunities for health education and monitoring of their health status.

Level 2. National determinants

Based on interviews, national determinants influencing the physical and cultural structures of society are the second set of factors affecting CO in our study. These determinants, considered fundamental by the participants, can be categorized into three main areas: (1) governance, (2) dominant social structures, and (3) national policies and regulations. Social structures significantly shape the behavior of parents and other adults, who in turn directly impact children’s lifestyles. Participants noted that social structures are predominantly influenced by governance and national policies and regulations. Conversely, social structures can also affect government and national policies and regulations, creating a triangular relationship that fundamentally impacts children’s weight management in Iran.

It is important to note that governance and national policies and regulations can directly influence individual behavior, as depicted in our model (Fig. 1). Our participants emphasized that significant improvements in children’s health, including the control of CO, cannot be achieved without substantial modifications to these determinants. Detailed descriptions of these three national determinants are provided in the following sections. Examples of quotes related to themes, sub-themes, and codes for national determinants are provided in Supplementary Table S3.

Governance

Some stakeholders, particularly scientists, have indicated some underlying deficits in governance in Iran as obstacles to obesity control. We have categorized their concerns into three subcategories: I) Inappropriate policy-making process, ii) low responsiveness and accountability, and iii) low collaboration and parallel working between stakeholders.

Inappropriate policy-making process

According to participants, high-level policymakers do not recognize obesity as a significant health problem. They consider obesity the disease of the affluent social class caused by overeating. Therefore, obesity control is an individual responsibility in their opinion. Scientists and other stakeholders thought policymakers had a stronger will to fight undernutrition. They promote policies to increase energy intake without considering protein and other nutrients, which increase the likelihood of obesity.

Some participants, experts in social science or health policy, indicated that in Iran, health problems generally do not receive high priority. The healthcare system predominantly focuses on treatment rather than preventive measures. Participants noted that prevention, being complex and multifaceted, faces low chances of success and is often avoided by policymakers, especially in politically unstable systems. Moreover, medicalization emerged as a concern among some stakeholders, contributing to these conflicts. This indicates that both society and the healthcare system lack a comprehensive approach to addressing health problems, including obesity. Instead of adopting a lifestyle-based approach, there is a prevalent inclination towards medication or surgical interventions. They emphasized that the missing piece in obesity management lies in targeting upstream solutions, such as modifying the obesogenic environment.

Several interviewees raised concerns about significant conflicts of interest within Iran’s health system. The lucrative nature of obesity treatments creates notable conflicts when prioritizing obesity prevention policies. Furthermore, certain conflicts of interest hinder the implementation of fiscal policies aimed at reducing the consumption of unhealthy foods.

Despite some efforts to enhance the policy-making process in Iran, stakeholders stated that health-related policies are primarily formulated and approved using a top-down approach. Stakeholders such as school staff, parents, civil society organizations, and health workers are not adequately involved in the policy-making process. Participants mentioned that these stakeholders possess valuable perspectives and solutions for controlling CO, and their inclusion in the policy-making process is crucial. Their involvement can lead to better-informed policies, foster greater acceptance of the adopted policies, and enhance the likelihood of successful implementation. Moreover, when executives are not involved in the policy-making process, they cannot understand the importance and aims of a policy. Therefore, they do not feel responsible for its implementation.

Low responsiveness and accountability

Participants expressed concerns that many policies in Iran have been implemented without considering their feasibility. Additionally, the monitoring and evaluation of these policies are not comprehensive, and most organizations fail to report their evaluation results. Interviewees recommended using monitoring results to adjust policies and improve their effectiveness.

Low collaboration and parallel working between stakeholders

Stakeholders have highlighted significant policy fragmentation among relevant organizations. Each ministry and organization tend to operate independently, developing its programs without considering the efforts of others. While some collaborations have been established in recent years, the prevailing trend is for each sector to pursue separate actions and seek recognition and benefits solely in its name.

Dominant social structures

Dominant social structures represent the second category of national determinants relevant to the control of CO in Iran. As previously mentioned, these structures significantly influence children’s lifestyles. This category can be further divided into four subcategories: I) Barriers regarding cultural norms, ii) Barriers to physical activity arising from urban design and air pollution, iii) Social transitions, and iv) Social inequalities.

Barriers regarding cultural norm

As mentioned earlier, a chubby child is considered healthy in Iran. Additionally, our society does not value physical activity, especially for older girls. Participants said parents also do not believe in the necessity of physical activity. They place a high emphasis on theory classes and believe that studying hard is the primary responsibility of all young people.

Barriers to physical activity arising from urban design and air pollution

Several stakeholders point out that urban design is a significant barrier to physical activity in Iran. Additionally, they mentioned that our cities are not safe for walking or cycling. Air pollution, both industrial and climate-related, further limits the possibilities for physical activity in most of Iran.

Social transitions

Many scientists have pointed out that Iran is experiencing economic and cultural transitions that have changed the lifestyle. This transition, along with a sharp increase in urbanization, has altered physical activity and energy intake, contributing to an increase in obesity.

Social inequalities

Several interviewees cited social inequalities as a significant determinant of child health, including weight status. They mentioned that inequality in access to health education and healthcare could increase the risk of malnutrition, which in turn could elevate the risk of obesity now or in the future. Most participants noted the existence of inequality in Iran in terms of both physical and economic access to healthy foods.

National policies and regulations

From the perspective of our stakeholders, national policies and regulations define social structures and can effectively determine the lifestyles of families. Good governance can create better social structures through policies and regulations. Several attempts have been made to modify regulations, particularly those related to food standards and labelling, to enable better food choices in Iran. However, participants pointed out flaws in Iran’s policies and regulations, classifying them as inappropriate fiscal and food promotion policies.

Inappropriate fiscal policies

Participants unanimously agreed on the shortcomings of the country’s fiscal policies that reinforce unhealthy eating patterns. They stated that Iranian food policy mainly focuses on providing energy and does not consider obesity control. Participants repeatedly noted that unhealthy foods are cheap and readily available. They suggested that subsidizing healthy foods and taxing unhealthy foods could promote healthier eating habits. However, stakeholders emphasized the need for modifications in subsidy policies to guide better food choices and allocate more resources to healthy foods and education for children.

Inappropriate food promotion policies

Participants indicated that while there are several regulations for food advertising on social media, these regulations are not adequately enforced. Stakeholders mentioned that although regulations have been passed to provide healthier foods in schools, implementation remains poor. They also noted that selling junk food in children’s areas such as parks, cinemas, and sports clubs is not prohibited. Although nutrition labels are mandatory in Iran, families do not base their food choices on these labels. Participants highlighted that families lack adequate training to use nutrition labels effectively. Additionally, food prices play a more significant role in determining families’ food choices.

Level 3. International determinants

Participants in this study indicated that international communication has transformed our planet into a global village. In this environment, the laws and actions of international organizations and powerful governments can partially determine the conditions in other countries. The global approach to ending CO, worldwide trade and international regulations; political sanctions, climate change, and the COVID-19 pandemic were identified as international determinants. The interviewees believed that the WHO positively impacts Iran’s health promotion programs. The Commission to End Childhood Obesity (ECHO) is a key player in CO control in Iran. Global trade policies and regulations determine most developing countries’ access to food. Additionally, several sanctions against Iran restrict the government’s business activities, significantly reducing Iranians’ access to healthy foods by limiting the ability to purchase livestock and agricultural inputs. These issues were exacerbated by climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to a significant increase in food prices, particularly healthy food. Prolonged quarantines, especially school closures, have aggravated the obesity crisis. Although the widespread use of improperly refined fossil fuels is the main cause of air pollution in Iran, climate change contributes to air pollution from suspended particles, especially in southern Iran, which hinders physical activity.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the primary factors contributing to CO in Iran, considering the perspectives of diverse stakeholders. we used an inductive thematic content analysis approach to obtain a comprehensive and profound understanding of participants’ beliefs and experiences regarding excessive weight gain in childhood. The findings revealed three distinct levels of determinants involved in this process: local, national, and international. At the local level, both the home and school environments were identified as crucial influencers of children’s weight status. However, it was found that these local factors are intricately intertwined with broader national determinants including governance, dominant social structures; and national policies and regulations; which significantly impact the development of an obesogenic environment. Additionally, international factors such as global trade policies and regulations, a global approach to addressing CO, sanctions, climate changes and the COVID-19 pandemic were identified as potential influences on Iranian children.

Childhood obesity determinants at the local level

The local environment could heavily affect a child’s weight status. The results of this study accept the pivotal role of home and school environments which are in line with the previous findings from Iran and other countries [30–35]. Parents play a pivotal role in children’s access to healthy lifestyles and are the first and most important role models for them [36, 37]. The significant role of socioeconomic factors in the food security of Iranian children is a consistent finding. Factors correlated with food insecurity (FI) in both urban and rural areas include the education level of the family head, parents’ occupations, family head’s occupation, occupational diversity, number of working family members, marital status of the family head, family size, number of children, household economic status, house area, home ownership, and living facilities [38].

Children spend most of their active time in school. Participants in this study point out that Iranian schools do not support a healthy lifestyle. Other studies in Iran have revealed a lack of practical programs to support healthy living in schools and kindergartens. The school’s cafeteria provides unhealthy foods [39] and school staff skip physical activity programs and classes. Additionally, low collaboration between stakeholders, insufficient financial resources, and inadequate monitoring of schools exacerbate the situation [40]. The Health Promoting Schools program was launched in Iran in 2013. However, schools are free to implement this program at their discretion, and even in those that do, unhealthy behaviors remain common [41]. Stakeholders noted that Iranian schools do not provide practical and effective health education. Additionally, unhealthy foods are easily accessible from school canteens, and children’s physical activity is not taken seriously. These findings align with several previous observational studies [40–44].

Childhood obesity is common in low and middle-income countries and is associated with barriers to physical activity such as unsafe environments and lack of access to parks. Other factors include female gender, history of undernutrition, unhealthy school foods, high pressure from school programs, and low nutrition knowledge [45–47]. Studies have provided sufficient evidence for the effectiveness of school-based programs in controlling obesity in low and middle-income countries. Programs that target both food intake and physical activity are more successful, especially when health education is included in the school curriculum [48].

A long-standing finding in our study is that schools pay too much attention to theoretical subjects necessary for the university entrance exam. This is mainly due to parental pressure on school staff. This pattern has been reported by some other Asian countries with intense competition in university entrance exams. Several studies have shown that significant physical activity decreases and dangerous energy intake increases occur around these exams. This unhealthy lifestyle is significantly associated with weight gain at this age [49, 50]. However, the local environment is significantly influenced by national-level factors, which will be discussed below.

Childhood obesity determinants at the national level

As mentioned before, national determinants could be classified into three groups. The first group is issues related to national governance. Stakeholders pointed out some structural problems in Iran’s health system. Medicalization is a major problem in our approaches to combating CO. Not surprisingly, several scientific articles discuss that medicalizing and ignoring environmental reform is a reductionist approach that quickly fails and harms children’s health, especially their mental health [51, 52].

The participants unanimously declared that the increasing prevalence of CO necessitated reforms in the cultural and physical environment of our society. Society and most health professionals seem to understand the need for urgent action. However, some stakeholders pointed out that the lack of political will to combat CO creates several obstacles, mainly from a budgetary and organizational perspective. An effective advocacy program targeting high-level politicians should be considered. In addition, the policy-making process in Iran requires more bottom-up design and the participation of all stakeholders. There is strong evidence that an advocacy collation framework [53] and an evidence-informed policy-making approach [54] increase the chance of feasible and acceptable policies [55].

The second group of national determinants is classified as dominant social structures. Some scientists in our study cited cultural and financial development as contributing factors to obesity in our society. Several other studies have identified rapid urbanization and social and demographic changes as causes of nutritional transition. The available data confirm fundamental changes in the food basket of Iranian families, showing a shift towards a higher-energy, lower-quality diet [56, 57]. The increase in obesity due to higher energy intake and the consumption of unhealthy foods during the early stages of economic development has also been reported in other countries [58].

This study revealed several cultural and physical barriers to physical activity. Other studies showed that the built environment including access to sidewalks, biking paths, green areas, groceries or fast-food restaurants, and the traffic and safety of the local areas all can determine the lifestyle and weight status of habitats [31]. Participants in our study mentioned that parents worry about their children walking or cycling to school, preferring instead to drive them by private car. These concerns are more pronounced for girls and negatively impact their physical activity. A review of 15 studies from various countries reveals common parental concerns about the inadequate infrastructure and safety for children walking to school. The studies indicate that the safety of walking paths and neighbourhood security significantly impacts the likelihood of children walking to school [59, 60].An interventional study in Irland showed that increasing the safety of walking paths, especially in streets close to school, can increase physical activity or the chance of walking to school [61].

The impact of the built environment on health, particularly child health, has been studied extensively. Research shows that various characteristics of the built and social environment significantly affect weight through food intake and physical activity levels. Factors such as neighbourhood safety, walkability, access to fast food restaurants, recreational facilities, parks or other green areas, perceived safety, rates of violent crime, and social cohesion can influence the prevalence of childhood obesity in society [62]. However, most studies are cross-sectional, and more long-term research is needed to clarify these associations more robustly.

One important social structure is cultural beliefs, which can affect health-related behaviours. For example, in several African and Asian countries, higher body weight is preferred, particularly for children and young women [63, 64]. In Sri Lanka [65] and Iran, chubby children are considered healthier. Generally, in the Mediterranean region, it is widely believed that fat girls are more attractive and have better fertility [58]. Generally, in low and middle-income countries, especially in rural areas, being overweight is considered a sign of wealth and health [64]. These beliefs pose a barrier to obesity control, which is identified as a cultural barrier to obesity control in Iran in our study.

The stakeholders endorsed that health education is essential to CO control in any context. However, they argue that education cannot significantly improve people’s lifestyles without creating a health-promoting environment. In agreement with our findings, Mirmiran et al. found that while the majority of adolescents in the TLG study (82% of girls and 75% of boys) had high nutritional knowledge, only a few (15% of girls and 25% of boys) had good dietary practices [66]. Other studies on Iranian families have concluded that nutrition education is insufficient for lifestyle modification [25]. Several stakeholders have indicated that nutritional education in Iranian schools and mass media is ineffective and has not resulted in major improvements in lifestyle. It seems that effective behaviour-changing education strategies were not applied. Moreover, the built environment does not support healthier choices, making changes more difficult. Other studies have shown that well-designed educational programs, when combined with a supportive environment, result in better weight management [67–69].

Most participants in this study cited the higher price of healthy foods as a barrier to following a healthy diet. They said that national improper fiscal policies are a significant obstacle to a healthy diet. They insist on implementing tax and subsidy policies to guide families’ choices of healthy foods. Stakeholders ranked proper fiscal food policies as the third important policy to control CO in Iran just after healthy school and healthy kindergartens in another study by our group [28]. In other studies, Iranian parents mentioned the high price of healthy foods as an obstacle to a healthy diet [22, 24]. Similar to our findings, comprehensive research has shown that low- and middle-income countries primarily subsidize food items that provide high energy. These fiscal policies are significantly related to the population’s body weight, as they often lead to increased consumption of calorie-dense foods. This, in turn, contributes to higher rates of obesity and related health issues in these countries [70].

There are several taxing policies in Iran but taxes are equally added to healthy and unhealthy foods which cannot decrease the consumption of unhealthy foods [71]. Studies have shown that taxing sugary drinks can reduce their consumption and overall energy intake, particularly in lower social classes in low-income countries. However, the long-term effects of this policy need to be studied in more depth [72, 73].

Childhood obesity determinants at the international level

This study pointed out that international factors mainly the World Health Organization’s approach to Ending CO, global trade policies, political sanctions, climate change, and the COVID-19 pandemic could affect CO. Iran started implementing Iran ECHO in six provinces in 2015 [16]. This program has been proposed by the World Health Organization and was supervised in several countries including Iran [16]. The recent assessment of this program showed an increase in students’ health knowledge but their practice was not enhanced meaningfully [74]. Moreover, the program was not implemented in most Iranian provinces and mainly focused on educational and screening programs in schools.

Several international factors mainly climate change, COVID-19 pandemic, and global trade policies affect food accessibility around the world. Some studies showed that globalization if not controlled by proper strategies could increase the risk of obesity in low and middle-income countries [75, 76] In Iran, all these factors reduced the food security of families in recent years which is exacerbated by political sanctions [77–79]. The price of a healthy food basket has risen over three times in 2018 compared to 2017 and vegetables, fruits and meat prices have risen more than other food groups [77] which all increases the risk of obesity.

The COVID-19 pandemic reduced the level of physical activity and increased the consumption of unhealthy foods in all age groups, but the effects were more adverse in children. Online schooling dramatically decreased the level of physical activity. Moreover, it reduced access of some children mainly from lower socioeconomic classes to school meals and health programs [4, 5, 80, 81]. In Iran, schools were closed for nearly two years which resulted in a fundamental decrease in children’s physical activity and an increase in obesity prevalence [82]. Unfortunately, even after the pandemic, Iranian schools are still online on some days due to high levels of air pollution which endanger the physical and psychological health of students.

Participants identified determinants of CO at local, national, and international levels. The effects at the local level are more noticeable, which is why several studies focus on them. However, recent research has highlighted the importance of upstream factors at the national level. Our participants noted that national-level determinants can significantly shape local determinants. Additionally, good governance at the national level can modify the effects of international determinants.

Children’s health is greatly influenced by the dual burden of malnutrition, encompassing both obesity and undernutrition. This issue is prevalent worldwide, especially in low and middle-income countries. To effectively address this, a comprehensive approach is necessary, one that tackles both forms of malnutrition simultaneously. Policies should be designed to promote balanced diets, improve food security, and enhance access to healthcare. By addressing the various environmental, social, and economic factors that contribute to malnutrition, we can create a supportive environment that ensures children’s well-being and promotes healthier communities [83, 84].

Unfortunately, most Iranian efforts to control CO have focused on health education programs and obesity treatment, stemming from the dominant belief that obesity is an individual responsibility. This pattern is common in many low-income countries [85]. For better control of CO, we need to advocate strongly for the ratification and implementation of upstream policies and monitor their enforcement [20, 85, 86]. This effort may require involving civil societies, which have proven to be powerful advocates for health policy ratification but are often overlooked in low-income countries [87, 88].

Limitation and strength of study

This study is a qualitative study that can have several weaknesses related to this method. First, the findings of this qualitative study are based on the participant’s point of view, which means there is no strong empirical evidence. Additionally, qualitative studies often have smaller sample sizes, which can limit the generalizability of the findings. The researcher’s subjectivity can influence the data collection and analysis process, potentially introducing bias. On the other hand, qualitative studies address important aspects that cannot be captured by quantitative methods. We applied several strategies to increase the validity and trustworthiness of results which were reported in the method part.

We followed Lincon and Guba’s criteria closely to ensure the validity [29]. Moreover, we applied the consolidating criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies [26]. The main strength of this study is the interviews with various stakeholders involved in CO control. Our participants include faculty members from different perspectives, industry executives, members of the heads of several government agencies, and civil societies, providing maximum sample diversity. It confirms to a sum extent the relevance and validity of our results. This is the first study investigating the determinants of CO control in Iran. Furthermore, limited studies worldwide have looked at the issue through the lens of a wide range of stakeholders.

Conclusion

This study investigated the underlying factors contributing to obesity in Iranian children and adolescents, as perceived by stakeholders. The main determinants of obesity control in Iran were categorized into three levels: local, national, and international. While home and school environments significantly influence unhealthy lifestyles and energy imbalances in children, governance, social structure, and national policies/regulations critically shape the local environment. Advocacy is essential to initiate changes in governance, facilitating modifications in social structures and national policies/regulations to make healthier choices more accessible. Addressing obesity requires a multi-faceted approach involving various stakeholders at different levels of the socio-ecological model, encompassing cultural, social, political, and economic contexts. The study emphasizes the need for comprehensive policy reforms, stakeholder collaboration, and cultural and environmental changes to control CO in Iran effectively.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the stakeholders and experts who patiently participated in this study. Unfortunately, we could not disclose their names for the sake of confidentiality.

Author contributions

AT and FT designed the study. FT conducted the interviews and their initial analysis. PA reviewed the analysis and coding process. FT drafted the manuscript under the close supervision of PA. HA supervised the sampling process and reviewed the conceptual framework. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript, including the conceptual model. PA and AT are guarantors.

Funding

This study was supported by the Tehran University of Medical Science (no. 97-03-161-40986).

Data availability

For confidentiality, we cannot give access to raw interviews. Other data, including coded segments, are available through an email to A.T.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences approved the protocol of this project (no. 97-03-161-40986). All parts of the study were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research. After explaining the study objectives and protocol, informed consent was obtained from all participants. Interviewees were assured of data confidentiality, anonymity, and their right to withdraw at any stage.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

None of the authors declared conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Parisa Amiri, Email: amiri@endocrine.ac.ir.

Amirhossein Takian, Email: takian@tums.ac.ir.

References

- 1.Organization WH. Draft recommendations for the prevention and management of obesity over the life course, including potential targets [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2023 May 17].

- 2.Bhutta ZA, et al. The global challenge of childhood obesity and its consequences: what can be done? Lancet Global Health. 2023;11(8):e1172–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang X, et al. Global prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA pediatrics; 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Browne NT, et al. When pandemics collide: the impact of COVID-19 on childhood obesity. J Pediatr Nurs. 2021;56:90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Storz MA. The COVID-19 pandemic: an unprecedented tragedy in the battle against childhood obesity. Clin Experimental Pediatr. 2020;63(12):477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tahergorabi Z, et al. From obesity to cancer: a review on proposed mechanisms. Cell Biochem Funct. 2016;34(8):533–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piché M-E, et al. Overview of epidemiology and contribution of obesity and body fat distribution to cardiovascular disease: an update. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2018;61(2):103–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou Y, et al. Obesity and diabetes as high-risk factors for severe coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid‐19). Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews; 2020. p. e3377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Maccioni L, et al. Obesity and risk of respiratory tract infections: results of an infection-diary based cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lobstein T, et al. Child and adolescent obesity: part of a bigger picture. Lancet. 2015;385(9986):2510–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lancet T. Managing the tide of childhood obesity. Lancet. 2015;385:2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ng M, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384(9945):766–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelishadi R, et al. Methodology and early findings of the fourth survey of childhood and adolescence surveillance and prevention of adult non-communicable disease in Iran: the CASPIAN-IV study. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4(12):1451. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Djalalinia S, Moghaddam SS, Peykari N, Kasaeian A, Sheidaei A, Mansouri A, Mohammadi Y, Parsaeian M, Mehdipour P, Larijani B, Farzadfar F. Mortality attributable to excess body mass index in Iran: implementation of the comparative risk assessment methodology. Int J Prevent Med. 2015 Jan 1;6(1):107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.World Health Organization. Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013–2020. 2013.

- 16.Sayyari AA, Abdollahi Z, Ziaodini H, Olang B, Fallah H, Salehi F, Heidari-Beni M, Imanzadeh F, Abasalti Z, Fozouni F, Jafari S. Methodology of the comprehensive program on prevention and control of overweight and obesity in Iranian children and adolescents: the IRAN-Ending childhood obesity (IRAN-ECHO) program. Int J Prevent Med. 2017 Jan 1;8(1):107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Zargaraan A, Dinarvand R, Hosseini H. Nutritional traffic light labeling and taxation on unhealthy food products in Iran: health policies to prevent non-communicable diseases. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2017;19(8):18. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Esmaili H et al. Prevalence of general and abdominal obesity in a nationally representative sample of Iranian children and adolescents: the CASPIAN-IV study. Iran J Pediatr, 2015. 25(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Kleinert S, Horton R. Rethinking and reframing obesity. Lancet. 2015;385(9985):2326–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swinburn BA, et al. The global syndemic of obesity, undernutrition, and climate change: the Lancet Commission report. Lancet. 2019;393(10173):791–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stevenson C, et al. Adolescents’ views of food and eating: identifying barriers to healthy eating. J Adolesc. 2007;30(3):417–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amiri P, et al. Barriers to a healthy lifestyle among obese adolescents: a qualitative study from Iran. Int J Public Health. 2011;56(2):181–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roudsari AH, et al. Psycho-socio-cultural determinants of food choice: a qualitative study on adults in social and cultural context of Iran. Iran J Psychiatry. 2017;12(4):241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farahmand M, et al. Barriers to healthy nutrition: perceptions and experiences of Iranian women. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farahmand M, et al. What are the main barriers to healthy eating among families? A qualitative exploration of perceptions and experiences of tehranian men. Appetite. 2015;89:291–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flick U. An introduction to qualitative research. Sage Publications Limited; 2018.

- 28.Toorang F, et al. Setting and prioritizing evidence-informed policies to control childhood obesity in Iran: a mixed Delphi and policy dialogue approach. BMC Pediatr. 2022;22(1):724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lincoln YS. Naturalistic inquiry. The Blackwell encyclopedia of sociology; 2007.

- 30.Gable S, Lutz S. Household, parent, and child contributions to childhood obesity. Fam Relat. 2000;49(3):293–300. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jia P. Obesogenic environment and childhood obesity. Obes Rev. 2021;22:e13158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lindsay AC, et al. The role of parents in preventing childhood obesity. The Future of children; 2006. pp. 169–86. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Baygi F et al. Determinants of childhood obesity in representative sample of children in North East of Iran. Cholesterol, 2012. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Bahreynian M, et al. Association between obesity and parental weight status in children and adolescents. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2017;9(2):111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mohammadpour-Ahranjani B, et al. Contributors to childhood obesity in Iran: the views of parents and school staff. Public Health. 2014;128(1):83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bassul C, Corish CA, Kearney JM. Associations between the home environment, feeding practices and children’s intakes of fruit, vegetables and confectionary/sugar-sweetened beverages. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(13):4837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khashayar P, et al. Childhood overweight and obesity and associated factors in Iranian children and adolescents: a multilevel analysis; the CASPIAN-IV study. Front Pead. 2018;6:393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Narmcheshm S, et al. Socioeconomic determinants of food insecurity in Iran: a systematic review. J Asian Afr Stud. 2024;59(6):1908–60. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Esfarjani F, et al. Schools’ Cafeteria Status: does it affect snack patterns? A qualitative study. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4(10):1194. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Omidvar N, et al. Enabling food environment in kindergartens and schools in Iran for promoting healthy diet: is it on the right track? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(8):4114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yazdi-Feyzabadi V, et al. Is an Iranian health promoting School status associated with improving school food environment and snacking behaviors in adolescents? Health Promot Int. 2018;33(6):1010–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nazari H, et al. School Physical Education Curriculum of Iran from experts’ perspective: what it is and should be. Int J Environ Sci Educ. 2017;12(5):971–84. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hanieh Hashemi S et al. A comparative study of physical education curriculum in Iranian high schools with selected countries (USA, Germany, Australia, Japan). 2021.

- 44.Pour MJ, Esmaeeli MR, Ali M, Soltani H. Comparative study of the elementary physical education curriculum in Iran and some selected countries. Adv Environ Biol. 2013 Jul 1:1265–71.

- 45.Gupta N, et al. Childhood obesity in developing countries: epidemiology, determinants, and prevention. Endocr Rev. 2012;33(1):48–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kiranmala N, Das MK, Arora NK. Determinants of childhood obesity: need for a trans-sectoral convergent approach. Indian J Pediatr. 2013;80:38–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ranjani H, et al. Determinants, consequences and prevention of childhood overweight and obesity: an Indian context. Indian J Endocrinol Metabol. 2014;18(Suppl 1):S17–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Verstraeten R, et al. Effectiveness of preventive school-based obesity interventions in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96(2):415–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yoshinaga M, et al. Prevalence of childhood obesity from 1978 to 2007 in Japan. Pediatr Int. 2010;52(2):213–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim DM, Ahn CW, Nam SY. Prevalence of obesity in Korea. Obes Rev. 2005;6(2):117–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Swinburn BA, et al. The global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet. 2011;378(9793):804–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Katz D. Health: the medicalization of fat. Nature. 2014;510(7503):34–34. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pierce JJ, Osei-Kojo A. The Advocacy Coalition Framework, in Handbook on theories of Governance. Edward Elgar Publishing; 2022.

- 54.Tudisca V, et al. Development of measurable indicators to enhance public health evidence-informed policy-making. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16(1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Haynes E, Palermo C, Reidlinger DP. Modified policy-Delphi study for exploring obesity prevention priorities. BMJ open. 2016;6(9):e011788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ghassemi H, Harrison G, Mohammad K. An accelerated nutrition transition in Iran. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5(1a):149–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abdi F et al. Surveying global and Iranian food consumption patterns: A review of the literature. 2015.

- 58.Gonçalves H, et al. Adolescents’ perception of causes of obesity: unhealthy lifestyles or heritage? J Adolesc Health. 2012;51(6):S46–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Saelens BE, Handy SL. Built environment correlates of walking: a review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(7 Suppl):S550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eyler AA, et al. Policies related to active transport to and from school: a multisite case study. Health Educ Res. 2008;23(6):963–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hayes C, et al. Barriers and facilitators to adoption, implementation and sustainment of obesity prevention interventions in schoolchildren–a DEDIPAC case study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Daniels KM, et al. The built and social neighborhood environment and child obesity: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Prev Med. 2021;153:106790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pradeilles R, et al. Body size preferences for women and adolescent girls living in Africa: a mixed-methods systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2022;25(3):738–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Manafe M, Chelule PK, Madiba S. The perception of overweight and obesity among South African adults: implications for intervention strategies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(19):12335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wickramasinghe V. Childhood obesity: socio-cultural determinants. Sri Lanka J Child Health. 2018;47(3):193–203. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mirmiran P, Azadbakht L, Azizi F. Dietary behaviour of Tehranian adolescents does not accord with their nutritional knowledge. Public Health Nutr. 2007;10(9):897–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Worsley A. Nutrition knowledge and food consumption: can nutrition knowledge change food behaviour? Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2002;11:S579–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vio F, et al. Prevention of children obesity: a nutrition education intervention model on dietary habits in basic schools in Chile. Food Nutr Sci. 2015;6(13):1221. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pérez-Rodrigo C, Aranceta J. School-based nutrition education: lessons learned and new perspectives. Public Health Nutr. 2001;4(1a):131–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Abay KA, Ibrahim H, Breisinger C. Food policies and obesity in low-and middle-income countries. World Dev. 2022;151:105775. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ghodsi D, et al. Why has the taxing policy on sugar sweetened beverages not reduced their purchase in Iranian households? Front Nutr. 2023;10:1035094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nakhimovsky SS, et al. Taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages to reduce overweight and obesity in middle-income countries: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(9):e0163358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Itria A, et al. Taxing sugar-sweetened beverages as a policy to reduce overweight and obesity in countries of different income classifications: a systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2021;24(16):5550–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Abdollahi Z, et al. Effect of an educational intervention on healthy lifestyle in Iranian children and adolescents: the Iran-ending childhood obesity (IRAN-ECHO) program. Journal of nutritional sciences and dietetics; 2019.

- 75.Obasuyi OC. Globalisation and rising obesity in Low-Middle Income Countries. Adv Res. 2022;23(6):21–9. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Goryakin Y, et al. The impact of economic, political and social globalization on overweight and obesity in the 56 low and middle income countries. Soc Sci Med. 2015;133:67–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hejazi J, Emamgholipour S. The effects of the re-imposition of US sanctions on food security in Iran. Int J Health Policy Manage. 2022;11(5):651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mohammadi-Nasrabadi F, et al. Economic sanctions affecting household food and nutrition security and policies to cope with them: a systematic review. Int J Health Policy Manage. 2023;12(1):1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zamanialaei M, et al. Weather or not? The role of international sanctions and climate on food prices in Iran. Front Sustainable Food Syst. 2023;6:998235. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jenssen BP et al. COVID-19 and changes in child obesity. Pediatrics, 2021. 147(5). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 81.Stavridou A, et al. Obesity in children and adolescents during COVID-19 pandemic. Children. 2021;8(2):135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bagherian S, et al. Physical activity behaviors and overweight status among Iranian school-aged students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a big data analysis. Iran J Public Health. 2022;51(3):676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Popkin BM, Corvalan C, Grummer-Strawn LM. Dynamics of the double burden of malnutrition and the changing nutrition reality. Lancet. 2020;395(10217):65–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Organization WH. The double burden of malnutrition: policy brief. World Health Organization; 2016.

- 85.Sunguya BF, et al. Strong nutrition governance is a key to addressing nutrition transition in low and middle-income countries: review of countries’ nutrition policies. Nutr J. 2014;13:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Harkin T. Preventing childhood obesity: the power of policy and political will. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(4):S165–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mozaffarian D, Angell SY, Lang T, Rivera JA. Role of government policy in nutrition—barriers to and opportunities for healthier eating. BMJ. 2018 Jun 13;361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 88.Holdsworth M, et al. Developing national obesity policy in middle-income countries: a case study from North Africa. Health Policy Plann. 2013;28(8):858–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

For confidentiality, we cannot give access to raw interviews. Other data, including coded segments, are available through an email to A.T.