Abstract

Background

Cancer survivors may experience accelerated biological aging, increasing their risk of mortality. However, the association between phenotypic age acceleration (PAA) and mortality among cancer survivors remains unclear. This study aimed to evaluate the relationship between PAA and all-cause mortality, cancer-specific mortality, and non-cancer mortality among adult cancer survivors in the United States.

Methods

We utilized data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from 1999 to 2018, including 2,643 (unweighted) cancer patients aged ≥ 20 years. Phenotypic age was calculated using ten physiological biomarkers, and the residuals from regressing phenotypic age on chronological age (age acceleration residuals, AAR) were used to determine PAA status. Participants were divided into PAA and without PAA groups based on the sign of the residuals. Weighted Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to assess the association between PAA and mortality, adjusting for demographic characteristics, lifestyle factors, and comorbidities. Restricted cubic spline (RCS) models were employed to explore the dose-response relationship between AAR and mortality.

Results

Over a median follow-up of 9.16 years, 991 (unweighted) participants died. After adjusting for multiple covariates, PAA was significantly associated with increased risks of all-cause mortality (HR = 2.07; 95% CI: 1.69–2.54), cancer-specific mortality (HR = 2.15; 95% CI: 1.52–3.04), and non-cancer mortality (HR = 2.06; 95% CI: 1.66–2.57). Each one-unit increase in AAR was associated with a 4% increase in the risk of all-cause, cancer-specific, and non-cancer mortality (HR = 1.04; 95% CI: 1.03–1.05). RCS models indicated a linear dose-response relationship between AAR and mortality.

Conclusions

Among U.S. adult cancer survivors, PAA is significantly associated with all-cause, cancer-specific, and non-cancer mortality. PAA may serve as an important biomarker for predicting prognosis in cancer survivors.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12885-025-13760-6.

Keywords: Phenotypic age acceleration (PAA), Cancer survivors, All-cause mortality, Biological aging, NHANES

Introduction

Advancements in medical technology and the promotion of early cancer screening have significantly improved cancer survival rates, leading to a growing population of cancer survivors [1]. However, cancer survivors face multiple health challenges, including treatment-related side effects, increased comorbidities, and reduced quality of life [2, 3]. Recently, researchers have focused on the biological aging processes in cancer survivors, suggesting that they may experience accelerated biological aging, which could impact long-term health outcomes [4, 5].

Biological age refers to an individual’s physiological and functional status relative to their chronological age and reflects the degree of aging of the organism [6]. In recent years, various biomarkers have been proposed to more accurately capture biological aging, including epigenetic clocks (e.g., Horvath clock, Hannum clock, GrimAge), which measure DNA methylation patterns and have shown strong associations with mortality and other age-related outcomes [7, 8]. However, these epigenetic methods often require specialized laboratory procedures and can be expensive, limiting their feasibility in large-scale population studies. In contrast, phenotypic age (PA) integrates commonly measured clinical biomarkers (e.g., albumin, creatinine, glucose, C-reactive protein) to provide a comprehensive assessment of an individual’s biological aging [9], making it more accessible and cost-effective for broad epidemiological applications. Phenotypic age acceleration (PAA) reflects the extent to which an individual’s biological age exceeds their chronological age, with positive values indicating accelerated aging [10]. Previous studies have shown that PAA is highly correlated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with chronic diseases such as coronary artery disease and diabetes [11, 12], yet it remains unclear whether PAA is associated with mortality risk among cancer survivors.

Therefore, using nationally representative data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), this study aimed to evaluate the association between PAA and all-cause mortality, cancer-specific mortality, and non-cancer mortality among adult cancer survivors in the United States. We hypothesized that PAA would be significantly associated with these mortality outcomes and that a dose-response relationship exists. The findings will deepen our understanding of biological aging in cancer survivors and provide new prognostic assessment tools for clinical practice, ultimately improving long-term health management for this population.

Methods

Study population

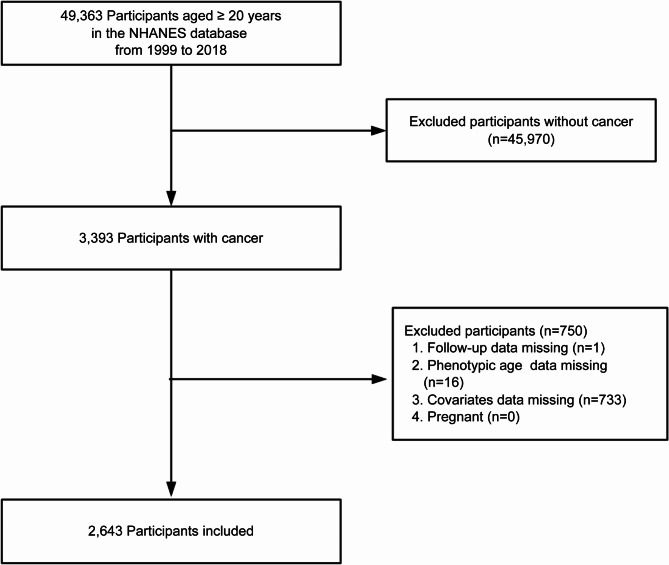

This study was based on data from NHANES conducted between 1999 and 2018. NHANES is a nationally representative survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) using a stratified, multistage probability sampling design to assess the health and nutritional status of the non-institutionalized U.S. population. We included cancer patients aged ≥ 20 years, identified by a “Yes” response to the question: “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had cancer or a malignancy of any kind?” [13]. Participants with missing follow-up data, phenotypic age data, covariate data, or who were pregnant were excluded. A total of 2,643 adult cancer patients were included (Fig. 1). All analyses were weighted to ensure national representativeness. NHANES study protocols were approved by the NCHS Research Ethics Review Board, and all participants provided written informed consent. This study adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.

Fig. 1.

Study flow chart

Measurement of phenotypic age acceleration

PA was estimated using ten aging-related variables: chronological age, albumin, creatinine, glucose, C-reactive protein (CRP), percentage of lymphocytes, mean cell volume, red cell distribution width, alkaline phosphatase, and white blood cell count [14]. PAA residuals were calculated by regressing phenotypic age on chronological age. PAA reflects the extent to which an individual’s biological age exceeds their chronological age; participants with positive residuals were classified as having PAA, while those with negative residuals were classified as without PAA [15]. Additionally, age acceleration residuals (AAR) were used as continuous variables to assess the dose-response relationship between phenotypic aging and mortality.

Ascertainment of mortality

Participants’ survival status was determined using the NHANES public-use linked mortality files, with follow-up through December 31, 2019. Causes of death were classified based on the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10), including all-cause mortality, cancer-specific mortality (ICD-10 codes C00–C97), and non-cancer mortality.

Assessment of covariates

Based on previous studies and clinical judgment [16, 17], covariates included age, gender, race, marital status, poverty income ratio (PIR), education level, body mass index (BMI), Healthy Eating Index (HEI-2015), smoking status, alcohol intake, physical activity, cardiovascular disease (CVD), hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes. Each covariate was selected for its potential to confound the relationship between PAA and mortality among cancer survivors. Specifically, age and gender are fundamental demographic factors associated with both overall mortality and biological aging processes [18, 19]. Race was included because racial disparities may contribute to differences in baseline health status, access to care, and mortality risk, as well as modulate aging biomarkers [20]. Marital status often reflects social support levels, which can affect health behaviors and prognosis in cancer patients [21]. Socioeconomic status, captured by PIR and education level, may affect both the biological aging trajectory (via chronic stress, healthcare access, and lifestyle factors) and mortality risk [22, 23]. BMI is a well-known indicator of metabolic and nutritional status and has been linked to inflammation and chronic diseases, potentially influencing both aging markers and survival [24, 25]. We included HEI-2015 as a measure of dietary quality because diet can modulate inflammation and overall health, thus affecting mortality and potentially the rate of biological aging [26]. Lifestyle factors, such as smoking status, alcohol intake, and physical activity, are crucial determinants of health: they influence inflammation, metabolic profiles, and the risk of chronic diseases, thereby potentially confounding the relationship between PAA and mortality [27]. CVD, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes were included given that these comorbidities can both accelerate biological aging and increase mortality risk [28–30]. By adjusting for these covariates, we aimed to isolate the effect of PAA from other pathways that could lead to higher mortality.

Specifically, age was treated as a continuous variable reflecting participants’ chronological age, while gender was categorized as male or female. We classified race into Non-Hispanic White versus Others (including non-Hispanic Black, Mexican American, other Hispanic, and other races). Marital status was categorized as married/living with partner or unmarried/other (widowed, divorced, or separated). The PIR was divided into three groups (1–1.3, 1.31–3.50, and > 3.50) [31], and education level was defined as less than high school, high school or equivalent, or more than high school. We calculated BMI by dividing weight (kg) by height squared (m^2). The HEI-2015 score, ranging up to 100, was used to assess overall dietary quality based on 13 components [32]. We defined smoking status as never smokers (fewer than 100 cigarettes in a lifetime), former smokers (smoked more than 100 cigarettes but no longer smoke), or current smokers (smoked more than 100 cigarettes and currently smoke) [33]. Alcohol intake was categorized as never drinkers (< 12 drinks in a lifetime), former drinkers (≥ 12 drinks/year but did not drink in the past year), or current drinkers (≥ 12 drinks/year who drank in the past year) [34]. Physical activity referred to time spent weekly on activities such as walking, cycling, work, or recreation; participants were labeled as insufficiently active (0–599 MET-min/week) or sufficiently active (≥ 600 MET-min/week)13. We defined CVD as any self-reported history of coronary heart disease, angina, stroke, heart attack, or congestive heart failure. Hypertension was determined by an average systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg, a self-reported diagnosis, or use of antihypertensive medications [33]. Hyperlipidemia was defined by any of the following criteria: use of lipid-lowering medications, hypertriglyceridemia (triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL), or hypercholesterolemia (total cholesterol ≥ 200 mg/dL, LDL ≥ 130 mg/dL, or HDL < 40 mg/dL) [35]. Lastly, diabetes was diagnosed if participants reported a physician diagnosis, or if their HbA1c was ≥ 6.5%, fasting glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L, random/ oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L, or they used diabetes medications/insulin35.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.2.3) and Free Statistics software (version 1.9.2; Beijing, China, http://www.clinicalscientists.cn/freestatistics), employing NHANES-recommended sampling weights for national representativeness. Following NHANES analytic guidelines, we incorporated the complex sampling design and mobile examination center (MEC) exam sample weights for both baseline characteristics and time-to-event outcomes (including deaths and follow-up time). Detailed information regarding the weighted analysis can be found in the Supplementary Methods. Categorical variables were expressed as weighted percentages; continuous variables as weighted means (standard deviations). Group differences were compared using weighted chi-square tests and weighted independent-samples t-tests. Survey-weighted Kaplan-Meier survival curves assessed mortality differences between PAA groups, with weighted log-rank tests.

The proportional hazards assumption was tested using Schoenfeld residuals. Weighted Cox proportional hazards regression models were employed to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between PAA and mortality. Model 1 was minimally adjusted (age, gender) to capture the crude association, Model 2 further controlled for key demographic and lifestyle factors (race, marital status, poverty income ratio, education level, HEI-2015, physical activity, smoking status, and alcohol intake), and Model 3 incorporated major clinical comorbidities (CVD, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes). This stepwise approach is frequently adopted in epidemiological research to illustrate how the observed relationship shifts as additional confounders are introduced, thereby clarifying the independent effect of PAA [36]. We then applied restricted cubic spline (RCS) models to explore potential nonlinear dose–response relationships between AAR and mortality. RCS is widely adopted in biomedical studies due to its flexibility in capturing nonlinear trends, interpretability for clinical audiences, and stability at the boundaries (as it constrains the spline to be linear in the tails). Subgroup analyses evaluated the consistency of PAA’s association with mortality across different populations.

Sensitivity analyses included: (1) excluding participants who died within 2 years of follow-up; (2) missing covariate values were imputed using multiple imputation by chained equations, resulting in 5 imputed datasets based on variables in the final statistical model. The results from all imputed datasets were combined following Rubin’s Rules [15]; (3) propensity score matching (PSM) was performed using the PAA group as the reference, with a 1:1 nearest neighbor matching algorithm and a caliper width of 0.2 to minimize bias and control for potential confounders. We used a logistic regression model in which the outcome variable was membership in the PAA group (yes/no), and the predictor variables included age, gender, race, marital status, PIR group, educational level, BMI, HEI-2015, physical activity, smoking status, alcohol intake, CVD, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes. After computing the propensity scores, we matched participants from each group based on the smallest distance within the specified caliper. We evaluated the balance of covariates between the matched groups using the standardized mean difference (SMD), with SMD < 0.1 indicating acceptable balance. Additional details on both multiple imputation procedures and PSM implementation can be found in the Supplementary Materials. Cox regression models were re-fitted to verify result robustness.

Results

Participant characteristics

Among 14,380 (in thousands) cancer patients, the mean age was 62.32 ± 14.55 years. Participants were divided based on PAA status. The PAA group had a significantly higher mean age than the without PAA group (65.53 ± 13.27 vs. 60.37 ± 14.95 years; P < 0.0001). The PAA group had a higher proportion of males (51.45% vs. 37.47%; P < 0.0001) and a lower proportion of non-Hispanic Whites (85.63% vs. 90.64%; P = 0.0013). The prevalence of CVD, hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia was significantly higher in the PAA group (all P < 0.05). Baseline characteristics differed significantly between groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of individuals with cancer in NHANES 1999–2018

| Variables | Total | without PAA | PAA | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted Population, n(in thousands) | 14380.45 | 8956.31 | 5424.14 | |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 62.32 (14.55) | 60.37 (14.95) | 65.528 (13.27) | < 0.0001 |

| Gender, n(in thousands), % | ||||

| Male | 6146.50 (42.74) | 3355.96.27 (37.47) | 2790.53 (51.45) | < 0.0001 |

| Female | 8233.95 (57.26) | 5600.35 (62.53) | 2633.60 (48.55) | |

| Race, n(in thousands), % | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 12762.72 (88.75) | 8117.89 (90.64) | 4644.83 (85.63) | 0.0013 |

| Others | 1617.73 (11.25) | 838.41 (9.36) | 779.32(14.37) | |

| Marital status, n(in thousands), % | ||||

| Married/Living with partner | 9726.69 (67.64) | 6245.89 (69.74) | 3480.80(64.17) | 0.0484 |

| Never married/Other | 4653.76(32.36) | 2710.41 (30.26) | 1943.35 (35.83) | |

| PIR, n(in thousands), % | ||||

| 1-1.3 | 2184.31 (15.19) | 1224.36 (13.67) | 959.95 (17.70) | < 0.0001 |

| 1.31–3.50 | 5139.16 (35.74) | 2901.94 (32.40) | 2237.22 (41.25) | |

| > 3.50 | 7056.98 (49.07) | 4830.00 (53.93) | 2226.98 (41.06) | |

| Education level, n(in thousands), % | ||||

| Less than high school | 2027.05 (14.10) | 1197.77 (13.37) | 829.28(15.29) | 0.0254 |

| High school or equivalent | 3438.78 (23.91) | 1996.96 (22.30) | 1441.82(26.58) | |

| Above high school | 8914.62 (61.99) | 5761.57 (64.33) | 3153.05 (58.13) | |

| BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 28.730 (6.38) | 27.367 (5.61) | 30.982 (6.93) | < 0.0001 |

| HEI-2015 score, mean (SD) | 54.69 (13.082) | 56.11 (13.278) | 52.35 (12.411) | < 0.0001 |

| Physical activity, n(in thousands), % | ||||

| Insufficiently active | 7405.54 (51.50) | 4509.00 (50.34) | 2896.54 (53.40) | 0.1859 |

| Sufficiently active | 6974.91 (48.50) | 4447.31 (49.66) | 2527.60 (46.60) | |

| Smoking status, n(in thousands), % | ||||

| Never | 6307.48 (43.86) | 4131.82(46.13) | 2175.66 (40.11) | 0.0306 |

| Former | 5786.74 (40.24) | 3488.32(38.95) | 2298.42 (42.37) | |

| Current | 2286.25 (15.90) | 1336.17 (14.92) | 950.08 (17.52) | |

| Alcohol intake, n(in thousands), % | ||||

| Never | 1380.04 (9.60) | 883.08 (9.86) | 496.96 (9.16) | < 0.0001 |

| Former | 3375.57(23.47) | 1752.81(19.57) | 1622.76(29.92) | |

| Current | 9624.84 (66.93) | 6320.41 (70.57) | 3304.43(60.92) | |

| CVD, n(in thousands), % | ||||

| No | 11552.85(80.34) | 7676.51 (85.71) | 3876.34 (71.46) | < 0.0001 |

| Yes | 2827.60 (19.66) | 1279.80 (14.29) | 1547.80 (28.54) | |

| Hypertension, n(in thousands), % | ||||

| No | 6184.40 (43.01) | 4392.60(49.04) | 1791.80 (33.03) | < 0.0001 |

| Yes | 8196.05 (56.99) | 4563.71(50.96) | 3632.34 (66.97) | |

| Hyperlipidemia, n(in thousands), % | ||||

| No | 2690.92(18.71) | 1884.34(21.04) | 806.58 (14.87) | 0.0021 |

| Yes | 11689.53 (81.29) | 7071.97 (78.96) | 4617.56 (85.13) | |

| Diabetes, n(in thousands), % | ||||

| No | 11512.16 (80.05) | 7985.72 (89.16) | 3526.44 (65.01) | < 0.0001 |

| Yes | 2868.29 (19.95) | 970.58 (10.84) | 1897.71(34.99) | |

| AAR, median [IQR] | -2.55 [-7.27, 3.26] | -6.17 [-9.17, -3.39] | 4.91 [2.34, 9.71] | < 0.0001 |

Abbreviations: PAA, phenotypic age acceleration; AAR, age acceleration residual; BMI, body mass index; HEI-2015, Healthy Eating Index-2015; PIR, poverty income ratio; CVD, cardiovascular disease

Association between PAA and mortality

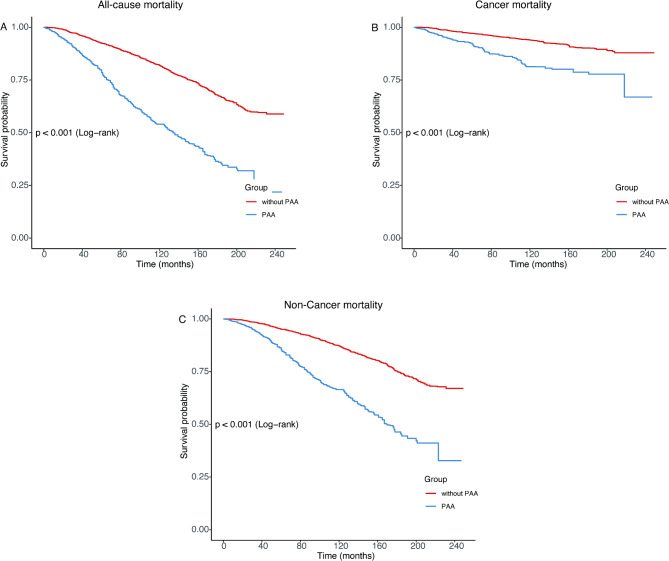

During a median follow-up of 9.16 years (IQR: 3.42–12.58 years), weighted analyses showed a total of 3,942 (in thousands) deaths, including 1,177 (in thousands) cancer-specific deaths and 2,765 (in thousands) non-cancer deaths. Survey-weighted Kaplan–Meier survival analysis showed that the PAA group had significantly higher all-cause, cancer-specific, and non-cancer mortality than the without PAA group (Fig. 2; all p < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Survey-weighted Kaplan‒Meier survival curve of all-cause mortality (A), cancer mortality (B), and non-cancer mortality (C) according to Phenotypic age acceleration among cancer adults

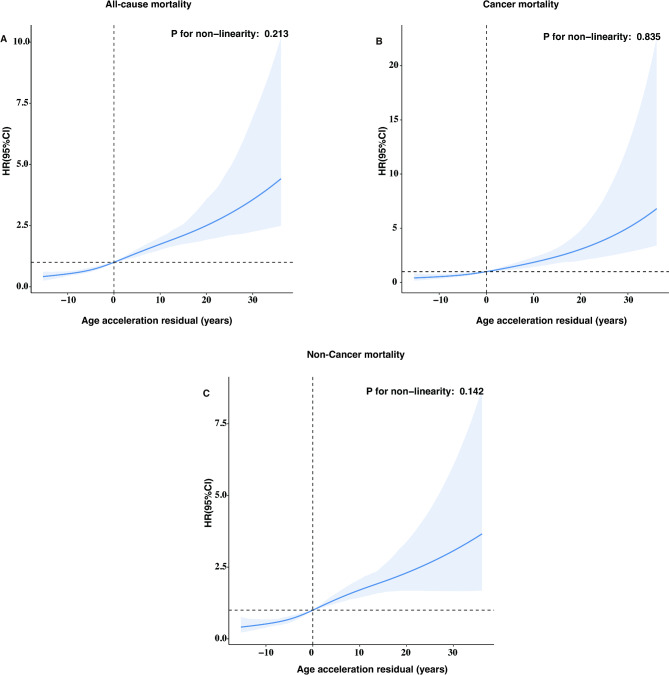

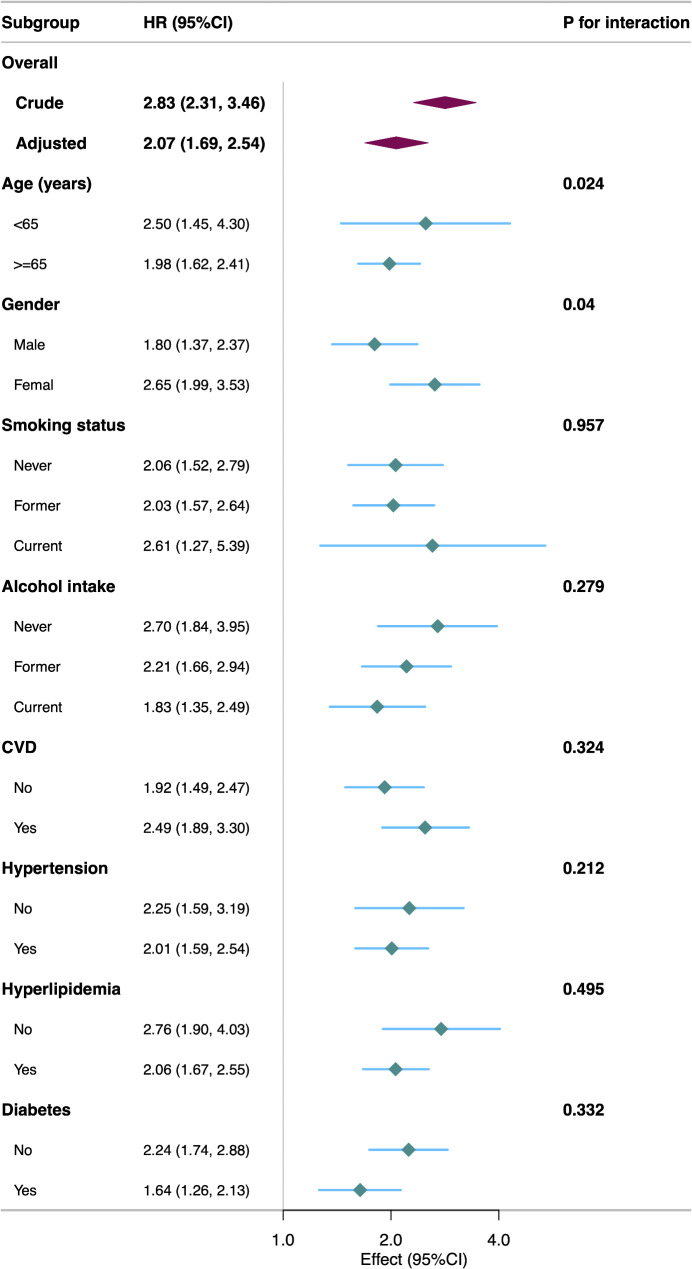

After adjusting for multiple covariates, PAA was significantly associated with increased risks of all-cause mortality (Model 3, HR = 2.07; 95% CI: 1.69–2.54; P < 0.001), cancer-specific mortality (HR = 2.15; 95% CI: 1.52–3.04; P < 0.001), and non-cancer mortality (HR = 2.06; 95% CI: 1.66–2.57; P < 0.001) (Table 2). Each one-unit increase in AAR was associated with a 4% increase in mortality risk (HR = 1.04; 95% CI: 1.03–1.05; P < 0.001). RCS models indicated a linear positive association between AAR and all-cause, cancer-specific, and non-cancer mortality (Fig. 3; all P for nonlinearity > 0.05). The association between PAA and all-cause mortality remained consistent across subgroups of age, gender, smoking status, alcohol intake, CVD, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes (Fig. 4). A significant interaction was observed in the age subgroup.

Table 2.

Weighted adjusted hazard ratios of phenotypic age acceleration with risk of all-cause mortality and cause-specific mortality

| Characteristics | Age acceleration residual | P-value | Phenotypic age acceleration | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||||

| All-cause mortality | |||||

| Model 1 | 1.04 (1.03–1.05) | < 0.001 | 1 (reference) | 2.31 (1.93–2.77) | < 0.001 |

| Model 2 | 1.04 (1.03–1.05) | < 0.001 | 1 (reference) | 2.15 (1.76–2.62) | < 0.001 |

| Model 3 | 1.04 (1.03–1.05) | < 0.001 | 1 (reference) | 2.07 (1.69–2.54) | < 0.001 |

| Cancer mortality | |||||

| Model 1 | 1.04 (1.03–1.05) | < 0.001 | 1 (reference) | 2.34 (1.71–3.19) | < 0.001 |

| Model 2 | 1.04 (1.03–1.05) | < 0.001 | 1 (reference) | 2.10 (1.51–2.90) | < 0.001 |

| Model 3 | 1.04 (1.03–1.05) | < 0.001 | 1 (reference) | 2.15 (1.52–3.04) | < 0.001 |

| Non-Cancer mortality | |||||

| Model 1 | 1.04 (1.03–1.05) | < 0.001 | 1 (reference) | 2.32 (1.91–2.81) | < 0.001 |

| Model 2 | 1.04 (1.03–1.05) | < 0.001 | 1 (reference) | 2.19 (1.76–2.73) | < 0.001 |

| Model 3 | 1.04 (1.03–1.05) | < 0.001 | 1 (reference) | 2.06 (1.66–2.57) | < 0.001 |

Model 1 was adjusted for age and gender. Model 2 was additionally adjusted for race, marital status, PIR group, educational level, BMI, HEI-2015, physical active, smoking status, and alcohol intake. Model 3 was additionally adjusted for CVD, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; HEI-2015, Healthy Eating Index-2015; PIR, poverty income ratio; CVD, cardiovascular disease

Fig. 3.

The dose‒response association of the Age Acceleration Residual with all-cause mortality (A), cancer mortality (B), and non-cancer mortality (C) among cancer adults

This spline model was adjusted for age, gender, race, marital status, PIR group, educational level, BMI, HEI-2015, physical active, smoking status, alcohol intake, CVD, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; HEI-2015, Healthy Eating Index-2015; PIR, poverty income ratio; CVD, cardiovascular disease

Fig. 4.

Subgroup analyses of the association of the Phenotypic age acceleration with all-cause mortality among cancer adults

This model was adjusted for age, gender, race, marital status, PIR group, educational level, BMI, HEI-2015, physical active, smoking status, and alcohol intake, CVD, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; HEI-2015, Healthy Eating Index-2015; PIR, poverty income ratio; CVD, cardiovascular disease

Sensitivity analysis

After excluding participants who died within 2 years, the association between PAA and all-cause mortality remained significant (HR = 1.95; 95% CI: 1.60–2.36; P < 0.001) (Table 3). Results were stable after multiple imputation and PSM (Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Table 2).

Table 3.

Weighted adjusted hazard ratios of phenotypic age acceleration with risk of all-cause mortality and cause-specific mortality after excluding deaths within 2 years

| Characteristics | Age acceleration residual | P-value | Phenotypic age acceleration | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||||

| All-cause mortality | |||||

| Model 1 | 1.04 (1.03–1.05) | < 0.001 | 1 (reference) | 2.19 (1.83–2.62) | < 0.001 |

| Model 2 | 1.04 (1.03–1.05) | < 0.001 | 1 (reference) | 2.02 (1.67–2.44) | < 0.001 |

| Model 3 | 1.04 (1.03–1.05) | < 0.001 | 1 (reference) | 1.95 (1.60–2.36) | < 0.001 |

| Cancer mortality | |||||

| Model 1 | 1.04 (1.02–1.05) | < 0.001 | 1 (reference) | 2.08 (1.51–2.87) | < 0.001 |

| Model 2 | 1.04 (1.02–1.05) | < 0.001 | 1 (reference) | 1.89 (1.37–2.62) | < 0.001 |

| Model 3 | 1.04 (1.02–1.05) | < 0.001 | 1 (reference) | 1.94 (1.37–2.74) | < 0.001 |

| Non-Cancer mortality | |||||

| Model 1 | 1.04 (1.03–1.05) | < 0.001 | 1 (reference) | 2.24 (1.84–2.74) | < 0.001 |

| Model 2 | 1.04 (1.03–1.05) | < 0.001 | 1 (reference) | 2.08 (1.66–2.61) | < 0.001 |

| Model 3 | 1.04 (1.03–1.05) | < 0.001 | 1 (reference) | 1.97 (1.57–2.46) | < 0.001 |

Model 1 was adjusted for age and gender. Model 2 was additionally adjusted for race, marital status, PIR group, educational level, BMI, HEI-2015, physical active, smoking status, and alcohol intake. Model 3 was additionally adjusted for CVD, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; HEI-2015, Healthy Eating Index-2015; PIR, poverty income ratio; CVD, cardiovascular disease

Discussion

This study, using NHANES data from 1999 to 2018, is the first to systematically evaluate the association between PAA and mortality among U.S. adult cancer survivors. We found that PAA was significantly associated with increased risks of all-cause, cancer-specific, and non-cancer mortality, even after adjusting for multiple confounders. A linear dose-response relationship between AAR and mortality was observed, indicating that higher degrees of biological age acceleration correspond to greater mortality risk. These findings underscore the potential value of PAA as a prognostic predictor for cancer survivors and enhance our understanding of the relationship between biological aging and health outcomes in this population.

Our findings align with previous research on biological age acceleration and mortality risk but provide new evidence specific to cancer survivors. Levine et al. developed the phenotypic age metric, integrating multiple physiological biomarkers to assess biological aging comprehensively, and found that acceleration in phenotypic age was significantly associated with all-cause mortality and morbidity [14]. In the general population, each one-year increase in biological age was associated with a 9% increase in all-cause mortality risk. Similarly, we found that each one-unit increase in AAR was associated with a 4% increase in all-cause mortality risk, which is comparable. However, studies focusing on cancer survivors have been limited.

Some research has explored biological aging markers in specific cancers. Kresovich et al. found that DNA methylation age acceleration was associated with increased all-cause and breast cancer-specific mortality in breast cancer patients [37]. Likewise, Kuo et al. observed that PAA was linked to poorer survival in lung cancer patients [38]. These studies, however, had smaller sample sizes and focused on single cancer types, limiting generalizability. Our study utilized nationally representative data, encompassing multiple cancer types, enhancing external validity. We found that the PAA group had a 107% increased risk of all-cause mortality, a 115% increased risk of cancer-specific mortality, and a 106% increased risk of non-cancer mortality, possibly reflecting more pronounced biological aging processes in cancer survivors, leading to higher mortality risks. Our study is the first to systematically evaluate PAA’s association with different mortality causes, providing strong evidence for its prognostic value in cancer survivors. Additionally, we confirmed the association between biological age acceleration and non-cancer mortality. Walker et al. reported that biological age acceleration was linked to increased mortality from cardiovascular and other non-cancer diseases in the general population [5]. Our results emphasize the impact of biological aging on the overall health of cancer survivors, suggesting that clinical practice should focus on comprehensive health management, not just cancer.

Moreover, PAA offers advantages over chronological age by capturing the influence of lifestyle, environment, and underlying health conditions on the aging process [39]. Unlike chronological age, which is a simple measure of time lived, PAA reflects the cumulative physiological toll arising from factors such as smoking, diet, physical inactivity, and comorbid diseases [40]. This enhanced definition and application value of PAA has led to growing interest in using it as a biomarker for various health outcomes, including mortality, chronic diseases, and functional decline, extending its relevance beyond oncology. In the cancer context specifically, PAA may help identify individuals whose underlying biology is more vulnerable to both disease progression and treatment-related toxicities, thus guiding more personalized treatment and follow-up plans.

Our study identified a linear dose-response relationship between AAR and mortality. This finding indicates that greater degrees of biological age acceleration are associated with higher mortality risk. Similar dose-response relationships have been reported in other research. For example, Perna et al. found that DNA methylation age acceleration was significantly associated with all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, and cancer incidence [41]. This further supports the validity of biological age acceleration as an effective prognostic indicator. In our subgroup analyses, we observed that the association between PAA and all-cause mortality was consistent across various subgroups, demonstrating the broad applicability of this relationship. However, a significant interaction was noted in the age subgroup. Older patients may be more sensitive to biological age acceleration, and its impact on mortality risk might be more pronounced. This could be attributed to the accumulation of physiological damage and decreased adaptability to environmental stressors in the elderly [42]. This finding aligns with the study by Li et al., who reported that the association between biological age acceleration and mortality risk was more significant in older individuals [43].

Several biological mechanisms may mediate the association between PAA and increased mortality. First, cancer and its treatments (e.g., chemotherapy and radiotherapy) can lead to DNA damage, oxidative stress, and cellular senescence, accelerating biological aging [4]. These changes may decrease tissue function and promote organ system decline, increasing mortality risk. Sehl et al. demonstrated that biological age significantly increased in breast cancer patients after chemotherapy, supporting the treatment’s impact on aging [44]. Second, PAA may reflect immune dysfunction and chronic inflammation, two key drivers of “inflammaging.” [45, 46] Persistent low-grade inflammation can hasten the senescence of immune cells (immunosenescence), impairing the immune system’s ability to surveil and eliminate malignant or pre-malignant cells [47]. Elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α) also disrupt normal tissue homeostasis and can alter the tumor microenvironment, favoring cancer progression and metastasis [48]. These pathways are especially relevant in cancer survivors, given that both the malignant process and anticancer therapies can trigger prolonged immune activation or suppression. Third, metabolic dysregulation frequently coexists with cancer or emerges post-treatment. We observed a higher prevalence of CVD, hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia in the PAA group, conditions closely linked to both aging and mortality risk [12, 49]. Metabolic syndrome features (e.g., insulin resistance and dyslipidemia) may exacerbate oxidative stress and inflammatory responses, creating a vicious cycle that further accelerates biological aging [50]. Moreover, excess adiposity and poor metabolic control can negatively impact treatment tolerance and recovery in cancer survivors, compounding risks [51]. Finally, lifestyle factors such as sedentary behavior, smoking, and suboptimal diet may amplify PAA by intensifying inflammatory and metabolic imbalances. These modifiable risk factors, when superimposed on cancer-related physiological stress, could push PAA to higher levels and portend worse survival outcomes. By examining these interconnected pathways (including immune dysfunction, chronic inflammation, and metabolic derangements), future research may better identify targeted interventions (e.g., anti-inflammatory treatments, tailored exercise programs, and metabolic control strategies) that attenuate PAA and potentially improve long-term prognoses in cancer survivors.

This study has several strengths. First, it used nationally representative NHANES data with a large, diverse sample. Second, phenotypic age, incorporating multiple physiological markers, provided a comprehensive assessment of biological aging. Third, adjusting for numerous confounders enhanced result reliability. Fourth, sensitivity and subgroup analyses verified robustness and consistency. However, limitations exist. First, although we adjusted for various demographic, lifestyle, and clinical factors, residual confounding by unmeasured or imprecisely measured variables may persist, potentially overestimating or underestimating the association between PAA and mortality. An E-value of 3.55 suggests that only a relatively strong unmeasured confounder could fully explain away our observed results. Second, certain variables (e.g., smoking, alcohol intake) are self-reported, raising the possibility of reporting bias. Underreporting of adverse behaviors, for instance, could lead us to underestimate their true impact on PAA and mortality. Finally, the data spanned multiple NHANES cycles (1999–2018), secular trends (e.g., healthcare improvements) and population aging over this period might shift baseline risks, and our models did not explicitly account for such temporal or cohort effects.

Clinically, PAA may serve as a promising prognostic tool for identifying high-risk cancer patients who could benefit from more individualized treatment strategies and closer surveillance. By integrating PAA into survivorship care, clinicians could better tailor interventions aimed at reducing accelerated aging—such as structured exercise programs, anti-inflammatory dietary patterns, and optimized management of comorbidities. Ultimately, understanding the relationship between PAA and cancer patient prognosis has crucial implications for improving long-term health outcomes and survivorship care, highlighting the need for further research into interventions that may mitigate biological age acceleration.

Conclusion

In summary, PAA is significantly associated with all-cause, cancer-specific, and non-cancer mortality among U.S. adult cancer survivors. PAA may be an important independent biomarker for predicting prognosis in this population. Our findings support incorporating biological age assessments into clinical practice and provide a foundation for developing strategies to improve long-term health in cancer survivors. Future studies should explore the longitudinal trajectory of PAA in diverse cancer populations, examine potential mechanisms more deeply, and test targeted interventions aimed at slowing or reversing biological aging to enhance survivorship outcomes.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Huanxian Liu (Department of Neurology, Chinese PLA General Hospital, Beijing, China), and Haoxian Tang (Department of Clinical Medicine, Shantou University Medical College, Shantou, Guangdong, China) for their valuable comments on the study design and manuscript.

Author contributions

X.L., Y.H. and Y.W. participated in the design of research schemes, extracted, and analyzed the data, and wrote the main manuscript text. C.L. and Y.H. collected the data. Y.Z., P.C. and B.X. participated in the design of research schemes. X.L. reviewed the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by China Scholarship Council(grant No. 201906070289), Startup Fund for Scientific Research, Fujian Medical University (grant No. 2022QH1268). The funders had no role in the study design, analysis, decision to publish, nor preparation of the manuscript.

Data availability

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. All data entered the analysis were from NHANES, which is publicly accessible to all.

Declarations

Ethics statement

Ethics approval was obtained from the NCHS Ethics Review Committee, and participants provided written informed consent.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Xiaoqiang Liu and Yubin Wang contributed to the work equally and should be regarded as co-first authors.

References

- 1.Crosby D, et al. Early detection of cancer. Science. 2022;375:eaay9040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.CAMPBELL KL, et al. Exercise guidelines for Cancer survivors: consensus statement from international multidisciplinary roundtable. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51:2375–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Firkins J, Hansen L, Driessnack M, Dieckmann N. Quality of life in chronic cancer survivors: a meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv. 2020;14:504–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang S, Prizment A, Thyagarajan B, Blaes A. Cancer Treatment-Induced accelerated aging in Cancer survivors: biology and assessment. Cancers. 2021;13:427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qin N, et al. Epigenetic age acceleration and chronic health conditions among adult survivors of childhood Cancer. JNCI: J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113:597–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beltrán-Sánchez H, Palloni A, Huangfu Y, McEniry MC. Modeling biological age and its link with the aging process. PNAS Nexus. 2022;1:pgac135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen L, Ganz PA, Sehl ME. DNA methylation, aging, and Cancer risk: A Mini-Review. Front Bioinform. 2022;2:847629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCrory C, et al. GrimAge outperforms other epigenetic clocks in the prediction of Age-Related clinical phenotypes and All-Cause mortality. Journals Gerontology: Ser A. 2021;76:741–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuo C, Pilling LC, Liu Z, Atkins JL, Levine ME. Genetic associations for two biological age measures point to distinct aging phenotypes. Aging Cell. 2021;20:e13376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu C, Hua L, Xin Z. Synergistic impact of 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations and physical activity on delaying aging. Redox Biol. 2024;73:103188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma Q et al. Association between Phenotypic Age and Mortality in Patients with Multivessel Coronary Artery Disease. Disease Markers. 2022;2022:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Liu W, et al. Oxidative stress factors mediate the association between life’s essential 8 and accelerated phenotypic aging: NHANES 2005–2018. Journals Gerontology: Ser A. 2024;79:glad240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wei X, et al. Joint association of physical activity and dietary quality with survival among US cancer survivors: a population-based cohort study. Int J Surg. 2024. 10.1097/JS9.0000000000001636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levine ME, et al. An epigenetic biomarker of aging for lifespan and healthspan. Aging. 2018;10:573–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen H, et al. Adherence to life’s essential 8 is associated with delayed biological aging: a population-based cross-sectional study. Revista Española De Cardiología (English Edition). 2024;S1885585724001427. 10.1016/j.rec.2024.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Xu X, Xu Z. Association between phenotypic age and the risk of mortality in patients with heart failure: A retrospective cohort study. Clin Cardiol. 2024;47:e24321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li X et al. Accelerated aging mediates the associations of unhealthy lifestyles with cardiovascular disease, cancer, and mortality: two large prospective cohort studies. in (2022). 10.1101/2022.05.18.22275184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Lv Y, et al. Gender differences in all-cause and cardiovascular mortality among US adults: from NHANES 2005–2018. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2024;11:1283132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hägg S, Jylhävä J. Sex differences in biological aging with a focus on human studies. eLife. 2021;10:e63425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang F, et al. Racial/Ethnic disparities in mortality related to access to care for major cancers in the united States. Cancers. 2022;14:3390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yuan R, Zhang C, Li Q, Ji M, He N. The impact of marital status on stage at diagnosis and. Survival of female patients with breast and gynecologic cancers: A Meta-Analysis. (2020) 10.21203/rs.3.rs-97311/v1 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Yogeswaran V, et al. Association of poverty-income ratio with cardiovascular disease and mortality in cancer survivors in the united States. PLoS ONE. 2024;19:e0300154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fiorito G, et al. The role of epigenetic clocks in explaining educational inequalities in mortality: A multicohort study and Meta-analysis. Journals Gerontology: Ser A. 2022;77:1750–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Giorgi U, et al. Association of body mass index and systemic inflammation index with survival in patients with renal cell cancer treated with nivolumab. JCO. 2019;37:e16077–16077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferrucci L, Fabbri E. Inflammageing: chronic inflammation in ageing, cardiovascular disease, and frailty. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2018;15:505–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jayanama K, et al. Relationship between diet quality scores and the risk of frailty and mortality in adults across a wide age spectrum. BMC Med. 2021;19:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Y, et al. Healthy lifestyle and life expectancy free of cancer, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020;l6669. 10.1136/bmj.l6669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Yang G, Zhong VW. Abstract MP34: association of biological age acceleration with incident. Type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease. Circulation 149, (2024).

- 29.Ammous F, et al. Epigenetic age acceleration is associated with cardiometabolic risk factors and clinical cardiovascular disease risk scores in African Americans. Clin Epigenet. 2021;13:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zaninotto P, Steptoe A, Shim E-J. CVD incidence and mortality among people with diabetes and/or hypertension: results from the english longitudinal study of ageing. PLoS ONE. 2024;19:e0303306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pan T, et al. The association between urinary incontinence and suicidal ideation: findings from the National health and nutrition examination survey. PLoS ONE. 2024;19:e0301553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reedy J, et al. Evaluation of the healthy eating Index-2015. J Acad Nutr Dietetics. 2018;118:1622–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tang H, Zhang X, Luo N, Huang J, Zhu Y. Association of dietary live microbes and nondietary prebiotic/probiotic intake with cognitive function in older adults: evidence from NHANES. J Gerontol Biol Sci Med Sci. 2024;79:glad175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rattan P, et al. Inverse association of telomere length with liver disease and mortality in the US population. Hepatol Commun. 2022;6:399–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mahemuti N, et al. Association between systemic Immunity-Inflammation index and hyperlipidemia: A Population-Based study from the NHANES (2015–2020). Nutrients. 2023;15:1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klanova M, et al. Prognostic impact of natural killer cell count in follicular lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients treated with immunochemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:4634–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kresovich JK, et al. Methylation-Based biological age and breast Cancer risk. JNCI: J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111:1051–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuo P-L, et al. A roadmap to build a phenotypic metric of ageing: insights from the Baltimore longitudinal study of aging. J Intern Med. 2020;287:373–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bian L et al. Associations of combined phenotypic aging and genetic risk with incident cancer: A prospective cohort study. (2023) 10.1101/2023.09.27.23296204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Yang G, et al. Association of unhealthy lifestyle and childhood adversity with acceleration of aging among UK biobank participants. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2230690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perna L, et al. Epigenetic age acceleration predicts cancer, cardiovascular, and all-cause mortality in a German case cohort. Clin Epigenet. 2016;8:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kravvariti E, et al. Geriatric frailty is associated with oxidative stress, accumulation, and defective repair of DNA Double-Strand breaks independently of age and comorbidities. Journals Gerontology: Ser A. 2023;78:603–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li X, et al. Longitudinal trajectories, correlations and mortality associations of nine biological ages across 20-years follow-up. eLife. 2020;9:e51507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sehl ME, Carroll JE, Horvath S, Bower JE. The acute effects of adjuvant radiation and chemotherapy on peripheral blood epigenetic age in early stage breast cancer patients. Npj Breast Cancer. 2020;6:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stevenson AJ, et al. Trajectories of inflammatory biomarkers over the eighth decade and their associations with immune cell profiles and epigenetic ageing. Clin Epigenet. 2018;10:159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lan YY, et al. Extranuclear DNA accumulates in aged cells and contributes to senescence and inflammation. Aging Cell. 2019;18:e12901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Salminen A. Immunosuppressive network promotes Immunosenescence associated with aging and chronic inflammatory conditions. J Mol Med. 2021;99:1553–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Florescu DN, et al. Correlation of the Pro-Inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, inflammatory markers, and tumor markers with the diagnosis and prognosis of colorectal Cancer. Life. 2023;13:2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang R-C, et al. Epigenetic age acceleration in adolescence associates with BMI, inflammation, and risk score for middle age cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metabolism. 2019;104:3012–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Šebeková K, et al. Association of inflammatory and oxidative status markers with metabolic syndrome and its components in 40-To-45-Year-Old females: A Cross-Sectional study. Antioxidants. 2023;12:1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Staley S-AM, et al. Visceral adiposity as a predictor of survival in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer receiving platinum and taxane-based chemotherapy. JCO. 2019;37:e17031–17031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. All data entered the analysis were from NHANES, which is publicly accessible to all.