Abstract

Aims: Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) immortalises B cells in vitro and is associated with several malignancies. Most phenotypic effects of EBV are mediated by latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1), which interacts with tumour necrosis factor receptor associated factors (TRAFs) to activate NF-κB. This study examines TRAF1 and LMP1 expression in EBV associated lymphoproliferations.

Methods: TRAF1 expression was investigated in 26 Hodgkin lymphomas (HL; 18 EBV+, eight EBV−), seven EBV+ Burkitt lymphomas (BL), two infectious mononucleosis (IM) tonsils, and lymphoreticular tissue from eight chronic virus carriers. Seven anaplastic large cell lymphomas and 10 follicular B cell lymphomas were also studied. Colocalisation of TRAF1 and LMP1 was studied by immunofluorescent double labelling and confocal laser microscopy.

Results: TRAF1 colocalises with LMP1 in EBV infected cells in IM. EBV positive lymphocytes from chronic virus carriers were negative for TRAF1 and LMP1. In HL biopsies, TRAF1 was strongly expressed independently of EBV status, whereas all BL cases were TRAF1−. In EBV+ HL cases, TRAF1 colocalised with LMP1. Eight of 10 follicular lymphomas expressed TRAF1 in centroblast-like cells. Four of seven anaplastic large cell lymphomas weakly expressed TRAF1.

Conclusions: These results suggest that in non-neoplastic lymphocytes, TRAF1 expression is dependent on the presence of LMP1, and that in IM B cells in vivo, LMP1 associated signalling pathways are active. In HL, TRAF1 is expressed independently of EBV status, probably because of constitutive NF-κB activation. The function of TRAF1 in HL remains to be determined.

Keywords: Epstein-Barr virus, tumour necrosis factor receptor associated factor 1, latent membrane protein 1, infectious mononucleosis, Hodgkin lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma

The Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) can infect human B cells in vitro, transforming them into permanently growing lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs).1 In LCL cells, the virus is present mainly as a latent infection and a limited set of latent viral gene products is expressed. These include two non-polyadenylated small nuclear RNAs (EBER1 and EBER2), six nuclear antigens (EBNA1, EBNA2, EBNA3A, EBNA3B, EBNA3C, and EBNA-LP), and three latent membrane proteins (LMP1, LMP2A, and LMP2B).1 This type of latent EBV infection is termed latency III.1 Although several of these viral proteins are required for B cell immortalisation, LMP1 has attracted most attention because of its ability to transform rodent fibroblasts.2 In addition, LMP1 mediates several phenotypic effects in B cells and epithelial cells, including upregulation of activation markers (for example, CD21, CD23, CD30, and CD40), adhesion molecules (for example, intercellular adhesion molecule 1, leucocyte function antigen 1 (LFA1), and LFA3), and antiapoptotic factors (for example, Bcl2 and A20).3–9 LMP1 aggregates constitutively at the cytoplasmic membrane and mimics a ligand independent member of the tumour necrosis factor (TNF) receptor family, similar but not identical to CD40.10–13 The effects of LMP1 are dependent on two regions located at the C-terminal intracytoplasmic region of the protein, termed C-terminal activating regions (CTAR1 and CTAR2).14 CTAR1 activates nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) signalling through interaction with the TNF receptor associated factors (TRAF1, TRAF2, and TRAF5), whereas TRAF3 appears to be a negative regulator of this effect.12,15 CTAR2 interacts with the TNF receptor associated death domain (TRADD) protein, also inducing NF-κB activation.16 Other signalling cascades activated by LMP1 are the Jun N-terminal kinase and the p38 mitogen activated kinase pathways.17–20 In B cells in vitro, most TRAF1 and TRAF3 molecules and approximately 5% of TRAF2 molecules are associated with LMP1.15 Importantly, in B cells CTAR1 appears to recruit TRAF2 largely through TRAF1, as a TRAF1–TRAF2 heterodimer.21 TRAF1 and TRAF3 do not interact with CTAR2, whereas TRAF2 appears to be indirectly recruited to CTAR2 through TRADD.16 Interestingly, TRAF1 is also an NF-κB target gene, being upregulated by LMP1 and CD40 signalling.21,22

In addition to EBV immortalised B cells in vitro, LMP1 expression has been detected in several EBV associated human diseases. These include infectious mononucleosis (IM) and immunosuppression related lymphoproliferations that express a latency III pattern of viral latent genes as seen in LCLs.1 In addition, tumour cells of EBV associated cases of Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) express LMP1 in the context of a latency II pattern (EBNA1 positive, other EBNAs negative, and LMP positive), whereas the tumour cells of endemic Burkitt lymphoma (BL) usually display a latency I pattern (EBNA1 positive, other EBNAs negative, LMP negative).1 These findings suggest that LMP1 associated signalling pathways may be important for the pathogenesis of some EBV associated tumours. In keeping with this notion, Liebowitz has shown that LMP1 colocalises and coimmunoprecipitates with TRAF1 and TRAF3 in immunosuppression related lymphoproliferations.23 Several groups have recently demonstrated the expression of TRAF1 in the Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg (HRS) cells of HL.24–27 In addition, Murray et al have demonstrated colocalisation of TRAF1 and TRAF2 with LMP1 in EBV associated HL.27

“In addition to EBV immortalised B cells in vitro, latent membrane protein 1 expression has been detected in several EBV associated human diseases”

Here, we have used newly generated monoclonal antibodies to study the expression of TRAF1 in EBV associated disorders with different types of viral latency. Double labelling immunofluorescence and confocal laser microscopy were used to find out whether TRAF1 and LMP1 colocalise in these lesions. Furthermore, we have used the RNase protection assay to investigate the expression of TRAF family members in HL derived cell lines.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tissues

Formalin fixed and paraffin wax embedded biopsy specimens from 26 cases of classic HL were retrieved from the files of the Institute for Pathology, Erlangen. These included 12 patients with nodular sclerosis and 14 patients with mixed cellularity. Eighteen cases of HL were EBV positive and LMP1 positive.28 In addition, paraffin wax blocks from seven cases of EBV positive endemic BL,29 seven cases of anaplastic large cell (ALC) lymphoma, and 10 cases of follicular B cell lymphoma were also available. Finally, tissue blocks from two tonsils taken from patients with acute IM and from seven lymph nodes and one tonsil from chronic virus carriers were analysed.

Monoclonal antibodies, immunohistochemistry, and in situ hybridisation

Monoclonal antibodies against TRAF1 were generated by injecting the TRAF1–GST (glutathione-S-transferase) fusion protein into LOU/C rats. Fusion of the myeloma cell line P3X63–Ag8.653 with rat immune spleen cells was performed according to a standard procedure. Hybridoma supernatants were tested in a solid phase immunoassay using the TRAF1–GST fusion protein. A TRAF2–GST fusion protein was used as a negative control. TRAF1-1F3 (rat IgG2a) and TRAF1-1H11 (rat IgG2a) reacted selectively in western blot analysis with TRAF1 and were therefore used in our study. The monoclonal antibodies CS1–4, specific for LMP1, were obtained from Dako (Glostrup, Denmark). The TRAF1 specific monoclonal antibody, H-3, was purchased from Santa Cruz, Heidelberg, Germany.

Paraffin wax embedded sections were subjected to microwave antigen retrieval using citrate buffer as described previously.30 After incubation with appropriately diluted primary antibodies, sections were subjected to immunohistochemistry using biotin labelled rabbit antirat or rabbit antimouse immunoglobulins, as appropriate, followed by incubation with a streptavidin biotinylated alkaline phosphatase complex (ABC-AP; Dako). Alkaline phosphatase was developed using fast red (Sigma, Steinheim, Germany) as a chromogen. The detection of bound H-3 antibody required the application of tyramide signal amplification, as described previously.30

In situ hybridisation for the detection of the EBERs was carried out as described previously using 35S labelled or digoxigenin labelled RNA probes.30 Double labelling with anti-TRAF1 antibodies and 35S labelled EBER specific probes was carried out as described previously.31

For colocalisation of LMP1 and TRAF1, LMP1 was detected using fluorescein isothiocyanate labelled goat antimouse immunoglobulins (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany). TRAF1 was visualised with a biotin labelled rabbit antirat immunoglobulin, followed by incubation with Cy5 labelled streptavidin (Dianova). Stained sections were evaluated by confocal laser microscopy.

Cell lines

The HL derived cell lines, L428 and HDLM2, were obtained from Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen, Braunschweig, Germany.

RNase protection assay

Total RNA was extracted from two HL derived cell lines, L428 and HDLM2, using the RNeasy midi kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The RNase protection assay (RPA) was carried out using a Riboquant multiprobe template set (hAPO-5b; BD Pharmingen, Heidelberg, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The template set consisted of DNA templates specific for TRAF1, TRAF2, TRAF3, TRAF4, TRAF5, TRAF6, I-TRAF, and TRAF interacting protein (TRIP). HeLa RNA was supplied by the manufacturer as a control. A 10 μg aliquot of total RNA and 6 × 105 counts/minute of labelled probe were used for hybridisation. 33P labelled protected fragments were resolved by electrophoresis in 5% polyacrylamide Tris/acetate/EDTA/urea gels. Gels were dried and exposed to a phosphoroimaging screen and hybridisation signals were quantified using the Tina program (Raytest Isotopenmessgeräte, Straubenhardt, Germany).

RESULTS

TRAF1 expression in primary and persistent EBV infection

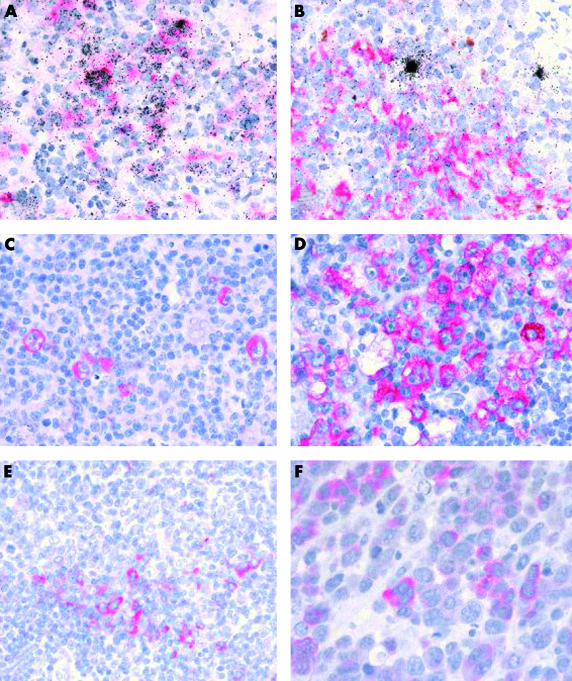

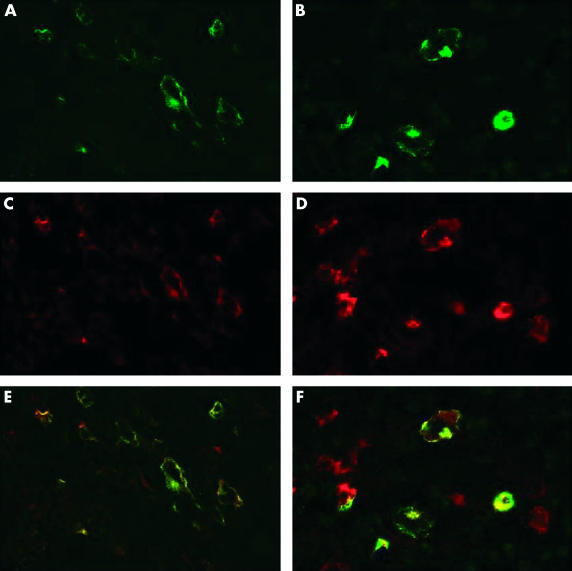

In agreement with a previous report, staining of paraffin wax embedded sections from hyperplastic tonsils revealed the expression of TRAF1 in interdigitating reticulum cells (IDC) and in scattered germinal centre centroblasts (not shown).32 Moreover, both TRAF1 specific antibodies showed identical staining patterns (as in all other experiments). EBER specific in situ hybridisation revealed numerous EBV infected lymphoid cells in two tonsils from patients with acute IM, as reported previously (fig 1A ▶).33 In comparison, few EBV positive cells were detected in lymphoid tissues from chronic virus carriers (fig 1B ▶). TRAF1 immunostaining of the two IM tonsils resulted in the staining of numerous extrafollicular lymphoid blasts in addition to IDCs. Double staining experiments revealed that this reactivity was restricted to the EBV infected cells, as demonstrated by EBER specific in situ hybridisation (fig 1A ▶). Quantitative enumeration showed that 36% and 39% of EBER positive cells coexpressed TRAF1. Double immunofluorescence and confocal laser microscopy revealed that, with the exception of IDC, the TRAF1 expressing cell population was largely identical to the LMP1 positive population (fig 2A,B ▶). Moreover, overlaying the images showed colocalisation of the TRAF1 and the LMP1 specific signals (fig 2C ▶). In contrast, most EBER expressing cells detected in tissues from chronic virus carriers were LMP1 negative and also did not express TRAF1 (fig 1B ▶). However, there were isolated EBER positive cells coexpressing TRAF1 even in tissues from chronic virus carriers. Fifteen EBER positive cells coexpressing TRAF1 were identified in all eight cases out of a total of 670 EBER positive cells (2.2%) counted.

Figure 1.

(A) Double labelling immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridisation show tumour necrosis factor receptor associated factor 1 (TRAF1) expression (red staining) in numerous Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) positive (black grains over nuclei of infected cells) cells in infectious mononucleosis, whereas (B) isolated EBV positive cells in chronic virus carriers are TRAF1 negative. (C, D) Immunohistology reveals TRAF1 expression (red labelling) in Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg cells in cases of Hodgkin lymphoma. (E) In follicular lymphomas, scattered cells at the margin of the neoplastic follicles express TRAF1. (F) Anaplastic large cell lymphomas show weak expression of TRAF1 in a proportion of tumour cells. Note that C, D, E, and F illustrate immunohistochemical staining without simultaneous EBV specific in situ hybridisation.

Figure 2.

Immunofluorescence staining for (A, B) latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1; green) and for (C, D) tumour necrosis factor receptor associated factor (TRAF1; red) shows similar patterns of labelling and overlaying the images reveals colocalisation of the signals (yellow) in most cells in (A, C, E) infectious mononucleosis and (B, D, F) an Epstein-Barr virus positive case of Hodgkin lymphoma. Some additional red staining is probably caused by the expression of TRAF1 in interdigitating reticulum cells.

TRAF expression in HD and non-Hodgkin lymphoma

Using immunohistochemistry with the monoclonal antibodies TRAF1-1F3 and TRAF1-1H11, TRAF1 expression was detected in the HRS cells from all classic HL cases (fig 1C,D, both illustrated cases were EBV positive). Between 20% and, in most cases, over 80% of tumour cells were labelled. The expression of TRAF1 in HRS cells was independent of EBV infection and LMP1 expression, both with regard to the staining intensity and to the number of labelled cells. In addition to HRS cells, variable numbers of interdigitating cells were stained. The patterns of reactivity seen with both TRAF1 specific antibodies were virtually identical. In comparison, staining with the commercially available TRAF1 specific reagent, H-3, yielded positive staining of HRS cells in 17 of the 24 cases analysed (not shown). In four cases, labelling of HRS cells could not be assessed because of excessive background labelling, and in three cases HRS cells were negative, although TRAF1 specific labelling was detected using the monoclonal antibodies TRAF1-1F3 and TRAF1-1H11 (not shown).

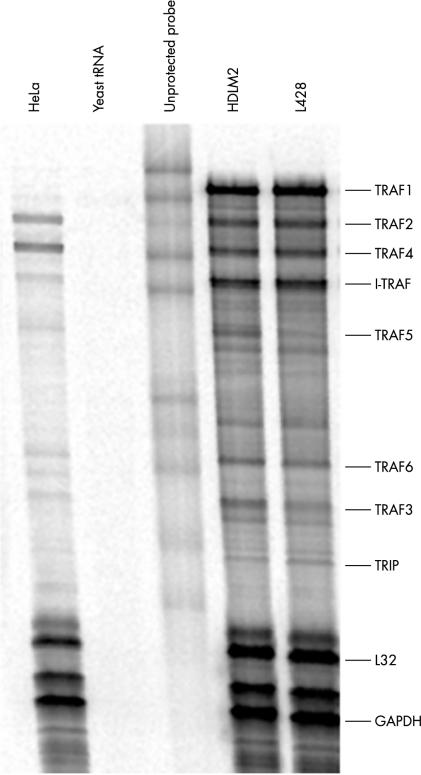

Double staining immunofluorescence revealed colocalisation of TRAF1 with LMP1 in EBV positive HL cases (fig 2D–F ▶). RPA analysis revealed a high degree of TRAF1 expression in both HL derived cell lines. All other members of the TRAF family were expressed to a lower degree (fig 3 ▶; table 1 ▶).

Figure 3.

Ribonuclease protection assay analysis of TRAF expression in cell lines derived from Hodgkin lymphoma. The cell lines analysed were HeLa (cervical carcinoma), HDLM2 (Hodgkin lymphoma), and L428 (Hodgkin lymphoma). Each unprotected probe band migrates more slowly than its corresponding protected band because of flanking sequences in the probe that are not protected by mRNA.

Table 1.

TRAF expression in cell lines derived from Hodgkin lymphoma determined by the RNA protection assay

| Cell line | TRAF1 | TRAF2 | TRAF3 | TRAF4 | TRAF5 | TRAF6 | TRIP | I-TRAF |

| HDLM2 | 0.665 | 0.264 | 0.111 | 0.247 | 0.144 | 0.107 | 0.035 | 0.403 |

| L428 | 0.721 | 0.297 | 0.074 | 0.279 | 0.087 | 0.089 | 0.043 | 0.436 |

The values indicate the relative degree of expression compared with the GAPDH house keeping gene. For explanation of the cell lines see legend to fig 3 ▶.

GADPH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; TRAF, tumour necrosis factor receptor associated factor; TRIP, tumour necrosis factor receptor associated factor interacting protein.

Immunohistochemical staining of seven EBV positive BL cases revealed a complete lack of detectable TRAF1 expression (not shown). In agreement with a previous report, follicular lymphomas showed weak to moderate expression of TRAF1 in centroblast-like cells in the neoplastic follicles in eight of 10 cases (fig 1E ▶).32 Only weak expression of TRAF1 was seen in four of seven CD30 positive anaplastic large cell lymphomas, as reported previously (fig 1F ▶).24

DISCUSSION

Ours is the first study to show that in IM EBV infected immunoblasts express TRAF1. Moreover, the LMP1 and TRAF1 expressing cell populations were largely identical and TRAF1 was shown to colocalise with LMP1. The fact that TRAF1 is upregulated by LMP1 and CD40 signalling through NF-κB and, on the other hand, itself associates with CTAR1 of LMP1,21,22,34 is consistent with the notion that LMP1 associated signalling pathways are active during primary EBV infection. In contrast, most EBV positive cells in tissues from chronic virus carriers were negative for LMP1 and TRAF1. This is in agreement with previous studies showing that normal resting lymphocytes are TRAF1 negative and that TRAF1 expression in lymphocytes is upregulated by mitogens.35 Thus, the absence of LMP1 and TRAF1 from EBV positive lymphocytes in persistent infection is in keeping with the idea that these cells are mainly resting B cells expressing a very limited number of viral proteins, if any.36 Therefore, it appears that in non-neoplastic EBV infected lymphocytes the expression of TRAF1 is correlated with the detection of LMP1. This conclusion is in agreement with the known ability of LMP1 to upregulate TRAF1 expression in B cells.21 Moreover, endemic BL cells, which usually lack detectable LMP1 expression, also displayed a lack of detectable TRAF1 expression. BL cells consistently express CD40 and respond to CD40 signalling with NF-κB activation.34 Thus, the absence of detectable TRAF1 in BL biopsies suggests that CD40 signalling is not active in BL in vivo.

“By means of RNase protection assay analysis, we showed that tumour necrosis factor receptor associated factor 1 (TRAF1) is the most abundantly expressed TRAF family member in Hodgkin lymphoma derived cell lines”

By means of RPA analysis, we showed that TRAF1 is the most abundantly expressed TRAF family member in HL derived cell lines. Previous studies have demonstrated the expression of TRAF1 RNA and protein in HRS cells of HL,24–27 a finding confirmed here both in vitro and in vivo using newly generated TRAF1 specific monoclonal antibodies. Using RPA analysis, we showed that HL derived cell lines express TRAF1, TRAF2, TRAF3, TRAF4, TRAF5, TRAF6, I-TRAF, and low amounts of TRIP RNA, largely confirming previous studies.37 Dürkop et al reported the expression of TRAF1 mRNA in HRS cells of all classic HL cases,24 and the degree of TRAF1 expression was reported to correlate with EBV infection. Using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction of microdissected HRS cells, Messineo et al detected TRAF1 RNA transcripts in HRS cells from four of five patients with classic HL.25 Using immunohistochemistry, Murray et al demonstrated the expression of TRAF1 in HRS cells in approximately 40% of HL cases and of TRAF2 in approximately 50% of cases.27 The expression of TRAF1, but not of TRAF2, correlated with EBV infection of the HRS cells in this study, in that 61% of EBV positive HL cases but only 33% of EBV negative cases were reported to show TRAF1 expression in the HRS cells.27 In addition, colocalisation of LMP1 and TRAF1 was demonstrated in six LMP1 positive patients, and LMP1 expression was shown to upregulate the expression of TRAF1 in an HL derived cell line, L428.27 Finally, Izban et al reported the expression of TRAF1 and TRAF2 in HRS cells of all HL cases, regardless of the EBV status of the tumour cells.26 In agreement with this last study, we did not find a correlation between TRAF1 expression and EBV infection in HL because in our study all cases, regardless of EBV status, showed TRAF1 expression in the HRS cells. The differences between our current study and earlier studies may result from the higher sensitivity of our monoclonal antibodies, combined with a lower background staining, compared with the commercially available reagents used previously. The detection of TRAF1 in HRS cells regardless of EBV status is in keeping with several features of HRS cells. HRS cells express CD40 and upregulation of TRAF1 expression by CD40 signalling has been demonstrated.22,38 Moreover, constitutive activation of NF-κB in HRS cells has been reported. It has been shown that the proliferation and survival of HRS cells depend on NF-κB activation and that NF-κB inhibition can cause a decline in the expression of several genes, including TRAF1.37,39

In contrast to other members of the TRAF family, TRAF1 shows a restricted expression pattern in normal tissues, where it is mainly confined to activated lymphocytes and dendritic cells.32 In addition, it is the only TRAF molecule lacking the “really interesting new gene” (RING) domain. TRAF1 binds to various intracellular proteins, including the TRADD protein, TRAF associated and NF-κB activator protein, TRIP, NF-κB inducing kinase, TRAF2, and A20.35 This would seem to suggest that TRAF1 is functionally important. Indeed, several studies have suggested an antiapoptotic function of TRAF1.35 Whether this is functionally relevant in HL remains to be established.

Take home messages.

The expression of tumour necrosis factor receptor associated factor 1 (TRAF1) is dependent on the presence of latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) in Epstein-Barr infected non-neoplastic lymphocytes

LMP1 associated signalling pathways are probably active in infectious mononucleosis B cells in vivo

In Hodgkin lymphoma, TRAF1 is expressed independently of Epstein-Barr virus status, probably because of constitutive activation of nuclear factor κB

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB466) to GN. We are grateful to Dr F Schrödel for help with confocal microscopy.

Abbreviations

ALC, anaplastic large cell

BL, Burkitt lymphoma

CTAR, C-terminal activating region

EBER, Epstein-Barr virus encoded non-polyadenylated small nuclear RNA

EBNA, Epstein-Barr virus encoded nuclear antigen

EBV, Epstein-Barr virus

GST, glutathione-S-transferase

HL, Hodgkin lymphoma

HRS, Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg

IDC, interdigitating reticulum cells

IM, infectious mononucleosis

LCL, lymphoblastoid cell line

LFA, leucocyte function antigen

LMP, latent membrane protein

NF-κB, nuclear factor κB

RPA, RNase protection assay

TNF, tumour necrosis factor

TRADD, tumour necrosis factor receptor associated death domain

TRAF, tumour necrosis factor receptor associated factor

TRIP, tumour necrosis factor receptor associated factor interacting protein

REFERENCES

- 1.International Agency for Research on Cancer. Epstein-Barr virus and Kaposi’s sarcoma herpesvirus/human herpesvirus 8. Lyon, France: World Health Organisation, 1997.

- 2.Wang D, Liebowitz D, Kieff E. An EBV membrane protein expressed in immortalized lymphocytes transforms established rodent cells. Cell 1985;43:831–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang D, Leibowitz D, Wang F, et al. Epstein-Barr virus latent infection membrane protein alters the human B-lymphocyte phenotype: deletion of the amino terminus abolishes activity. J Virol 1988;62:4173–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang F, Gregory CD, Sample C, et al. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein (LMP-1) and nuclear proteins 2 and 3C are effectors of phenotypic changes in B lymphocytes: EBNA2 and LMP-1 cooperatively induce CD23. J Virol 1990;64:2309–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dawson CW, Rickinson AB, Young LS. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein inhibits human epithelial cell differentiation. Nature 1990;344:777–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peng M, Lundgren E. Transient expression of the Epstein-Barr virus LMP1 gene in human primary B cells induces cellular activation and DNA synthesis. Oncogene 1992;7:1775–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rowe M, Peng-Pilon M, Huen DS, et al. Upregulation of bcl-2 by the Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein LMP1: a B-cell specific response that is delayed relative to NF-κb activation and to induction of cell surface markers. J Virol 1994;68:122–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laherty CD, Hu HM, Opipari AW, et al. Epstein-Barr virus LMP1 gene product induces A20 zinc finger protein expression by activating nuclear factor κB. J Biol Chem 1992;267:24157–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fries KL, Miller WE, Raab-Traub N. The A20 protein interacts with the Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) and alters the LMP1/TRAF1/TRADD complex. Virology 1999;264:159–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mosialos G, Birkenbach M, Yalamanchili R, et al. The Epstein-Barr virus transforming protein LMP1 engages signaling proteins for the tumour necrosis factor receptor family. Cell 1995;80:389–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kilger E, Kieser A, Baumann M, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-mediated B-cell proliferation is dependent upon latent membrane protein 1, which simulates an activated CD40 receptor. EMBO J 1998;17:1700–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eliopoulos AG, Stack M, Dawson CW, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-encoded LMP1 and CD40 mediate IL-6 production in epithelial cells via an NF-kB pathway involving TNF receptor-associated factors. Oncogene 1997;14:2899–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Floettmann JE, Eliopoulos AG, Jones M, et al. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein-1 (LMP1) signalling is distinct from CD40 and involves physical cooperation of its two C-terminus functional regions. Oncogene 1998;17:2383–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rowe M. The EBV latent membrane protein-1 (LMP1): a tale of two functions. Epstein-Barr Virus Report 1995;2:99–104. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Devergne O, Hatzivassiliou E, Izumi KM, et al. Association of TRAF1, TRAF2, and TRAF3 with an Epstein-Barr virus LMP1 domain important for B-lymphocyte transformation: role in NF-κB activation. Mol Cell Biol 1996;16:7098–7108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sylla BS, Hung SC, Davidson DM, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-transforming protein latent infection membrane protein 1 activates transcription factor NF-κB through a pathway that includes the NF-κB-inducing kinase and the IκB kinases IKKα and IKKβ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998;95:10106–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eliopoulos A, Young LS. Activation of the cJun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway by the Epstein-Barr virus-encoded latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1). Oncogene 1998;16:1731–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kieser A, Kilger E, Gires O, et al. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein-1 triggers AP-1 activity via the c-jun N-terminal kinase cascade. EMBO J 1997;16:6478–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roberts ML, Cooper NR. Activation of a Ras–MAPK-dependent pathway by Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 is essential for cellular transformation. Virology 1998;240:93–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eliopoulos AG, Gallagher NJ, Blake SMS, et al. Activation of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway by Epstein-Barr virus-encoded latent membrane protein 1 coregulates interleukin-6 and interleukin-8 production. J Biol Chem 1999;274:16085–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Devergne O, McFarland EC, Mosialos G, et al. Role of TRAF binding site and NF-kB activation in Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1-induced cell gene expression. J Virol 1998;72:7900–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Craxton A, Shu G, Graves JD, et al. p38 MAPK is required for CD40-induced gene expression and proliferation in B lymphocytes. J Immunol 1998;161:3225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liebowitz D. Epstein-Barr virus and cellular signaling pathway in lymphomas from immunosuppressed patients. N Engl J Med 1998;338:1413–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dürkop H, Foss H-D, Demel G, et al. Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 1 is overexpressed in Reed-Sternberg cells of Hodgkin disease and Epstein-Barr virus transformed lymphoid cells. Blood 1999;93:617–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Messineo C, Jamerson MH, Hunter E, et al. Gene expression by single Reed-Sternberg cells: pathways of apoptosis and activation. Blood 1998;91:2443–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Izban KF, Ergin M, Martinez RL, et al. Expression of the tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factors (TRAFs) 1 and 2 is a characteristic feature of Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg cells. Mod Pathol 2000;13:1324–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murray PG, Flavell JR, Baumforth KRN, et al. Expression of the tumour necrosis factor receptor-associated factors 1 and 2 in Hodgkin disease. J Pathol 2001;194:158–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beck A, Päzolt D, Grabenbauer GG, et al. Expression of cytokine and chemokine genes in Epstein-Barr virus-associated nasopharyngeal carcinoma and Hodgkin disease. J Pathol 2001;194:145–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niedobitek G, Agathanggelou A, Rowe M, et al. Heterogeneous expression of Epstein-Barr virus latent proteins in endemic Burkitt lymphoma. Blood 1995;86:659–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niedobitek G, Herbst H. In situ detection of Epstein-Barr virus DNA and of viral gene products. In: Wilson JB, May GHW, eds. Epstein-Barr virus protocols. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press, 2001:79–91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Herbst H, Niedobitek G. Phenotype determination of Epstein-Barr virus infected cells in tissue sections. In: Wilson JB, May GHW, eds. Epstein-Barr virus protocols. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press, 2001:93–102. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Zapata JM, Krajewska M, Krajewski S, et al. TNFR-associated factor family protein expression in normal tissues and lymphoid malignancies. J Immunol 2000;165:5084–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Niedobitek G, Agathanggelou A, Herbst H, et al. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection in infectious mononucleosis: virus latency, replication and phenotype of EBV-infected cells. J Pathol 1997;182:151–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Henriquez NV, Floettmann E, Salmon M, et al. Differential response to CD40 ligation among Burkitt lymphoma lines that are uniformly responsive to Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein. J Immunol 1999;162:3298–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zapata JM, Reed JC. TRAF1: lord without a RING. Science’s STKE 2002;2002 (133):PE27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Thorley-Lawson DA, Babcock GJ. A model for persistent infection with Epstein-Barr virus: the stealth virus of human B cells. Life Sci 1999;14:1433–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hinz M, Löser P, Mathas S, et al. Constitutive NF-κB maintains high expression of a characteristic gene network, including CD40, CD86, and a set of antiapoptotic genes in Hodgkin/Reed-Sternberg cells. Blood 2001;97:2798–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carbone A, Gloghini A, Gattei V, et al. Expression of functional CD40 antigen on Reed-Sternberg cells and Hodgkin disease cell lines. Blood 1995;85:780–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bargou RC, Emmerich F, Krappmann D, et al. Constitutive nuclear factor-κB–RelA activation is required for proliferation and survival of Hodgkin disease tumor cells. J Clin Invest 1997;100:2961–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]