Abstract

Background

Hypoxia is associated with the evasion of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) from immune surveillance. Hypoxia increases the subpopulation of putative TNBC stem-like cells (TNBCSCs) through activating Wnt/β-Catenin signaling. The shedding of MHC class I-related chain A (MICA) is particularly noteworthy in cancer stem cells (CSCs), promoting the resistance of CSCs to natural killer (NK) cell cytotoxicity. To reestablish MICA/NKG2D-mediated immunosurveillance, we proposed the design of a fusion protein (SHH002-hu1-MICA) which consists of Frizzled-7 (Fzd7)-targeting antibody and MICA, serving as an engager retargeting NK cells against TNBCs, especially TNBCSCs.

Methods

Opal multicolor immunohistochemistry staining was used to validate the expression of membrane MICA (mMICA) and existence of NK cells in TNBC tumors; flow cytometry (FCM) assay was used to detect the expression of Fzd7/mMICA on TNBCs. Biolayer interferometry (BLI) and surface plasmon resonance (SPR) assays were executed to assess the affinity of SHH002-hu1-MICA towards rhFzd7/rhNKG2D; near-infrared imaging assay was used to evaluate the targeting capability. A cytotoxicity assay was conducted to assess the effects of SHH002-hu1-MICA on NK cell-mediated killing of TNBCs, and FCM assay to analyze the effects of SHH002-hu1-MICA on the degranulation of NK cells. Finally, TNBC cell-line-derived xenografts were established to evaluate the anti-tumor activities of SHH002-hu1-MICA in vivo.

Results

The expression of mMICA is significantly downregulated in hypoxic TNBCs and TNBCSCs, leading to the evasion of immune surveillance exerted by NK cells. The expression of Fzd7 is significantly upregulated in TNBCSCs and exhibits a negative correlation with the expression of mMICA and infiltration level of NK cells. On accurate assembly, SHH002-hu1-MICA shows a strong affinity for rhFzd7/rhNKG2D, specifically targets TNBC tumor tissues, and disrupts Wnt/β-Catenin signaling. SHH002-hu1-MICA significantly enhances the cytotoxicity of NK cells against hypoxic TNBCs and TNBCSCs by inducing the degranulation of NK cells and promotes the infiltration of NK cells in CD44high regions within TNBC xenograft tumors, exhibiting superior anti-tumor activities than SHH002-hu1.

Conclusions

SHH002-hu1-MICA maintains the targeting property of SHH002-hu1, successfully activates and retargets NK cells against TNBCs, especially TNBCSCs, exhibiting superior antitumor activities than SHH002-hu1. SHH002-hu1-MICA represents a promising new engager for NK cell-based immunotherapy for TNBC.

Keywords: MHC class I-related chain A, Natural killer - NK, Breast Cancer, Immunotherapy, Antibody

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

There is a deficiency in effective immunotherapy approaches for triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). TNBC stem-like cells (TNBCSCs) exhibit a heightened propensity to evade tumor immune surveillance.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

The novel fusion protein SHH002-hu1-MHC class I-related chain A (MICA) specifically targets Fzd7+ TNBC, disrupts Wnt/β-Catenin signaling and effectively enhances the level of membrane MICA on TNBCSCs, thereby facilitating natural killer (NK) cell infiltration and inducing immune surveillance mediated by NKG2D.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

SHH002-hu1-MICA represents a promising new engager for NK cell-based immunotherapy for TNBC, enriching the design concepts of antibody drugs and providing diverse functionalities for monoclonal antibodies that specifically target tumor markers.

Background

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is the most aggressive breast cancer subtype, lacking specific targets for effective therapeutic agents. Immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) directed against programmed death-1 (PD-1) or programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) has shown promising results in TNBC.1,3 Paradoxically, despite strong immunogenicity and a higher prevalence of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in TNBC, TNBC exhibits resistance to ICB treatments due to the presence of TNBC stem-like cells (TNBCSCs), consequently resulting in postsurgical relapse and a dismal prognosis.4

Natural killer (NK) cells, which display rapid and potent immunity to metastasis or hematological cancers, are poised to become key components of multipronged therapeutic strategies for cancer.5,7 As a key activating receptor, NKG2D was shown to play an important role in tumor cell rejection and tumor immunosurveillance through binding to MHC class I-related chain A (MICA), MICB, and UL16-binding proteins (ULBPs).8 9 However, the efficacy of NK cells is dramatically limited by immune evasion resulting from the reduced expression of MICA/B on cancer stem cells (CSCs).10 Advanced cancers, including TNBC, frequently escape this immune mechanism via shedding of MICA/B.7 11 12

Hypoxia, a common trait of the tumor microenvironment (TME), has been demonstrated to facilitate the evasion of tumors from immune surveillance and immunotherapy.13 14 In breast cancer, hypoxia is more evident in TNBC than in other breast cancer subtypes.15 16 Hypoxia contributes to immune escape in a hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1)-dependent manner.17 Furthermore, HIF-1α increases the subpopulation of TNBCSCs in response to hypoxia through the activation of Akt/Wnt/β-Catenin signaling.18 19 Compared with non-stem cells (NSCs), the shedding of MICA/B is increased significantly in breast CSCs (BCSCs), promoting the resistance of BCSCs to NK cell cytotoxicity.4 10 Therefore, the treatment approach capable of effectively activating NK cell-mediated immune surveillance in hypoxic conditions represents a promising immunotherapeutic strategy for TNBC.

Wnt/β-Catenin signaling pathway is aberrantly activated in TNBC. Fzd7, one of the major receptors, shows the greatest difference in expression as compared with other members of the Fzd protein family.20 21 Wnt/β-Catenin signaling has been demonstrated to assume a pivotal regulatory function in the self-renewal of CSCs, and Fzd7 has also been confirmed to play a crucial role in stem cell biology, cancer development, and progression.22,24 The expression of Fzd7 was found to be significantly up-regulated in the hypoxic regions of TNBC.18 Hence, Fzd7, which is abnormally highly expressed in the hypoxic region of tumors and serves as a potential marker for CSCs, represents a promising drug target.25 26

SHH002-hu1, a high-affinity antibody specifically targeting the cysteine-rich domains domain of Fzd7 generated by our group, was demonstrated to be a potential therapeutic agent for TNBC.18 27 To stimulate NKG2D-mediated immunosurveillance, we proposed the design of a novel fusion protein (SHH002-hu1-MICA) which consists of SHH002-hu1 and MICA. SHH002-hu1-MICA selectively binds to Fzd7+ tumor cells, and MICA protein was displayed on the surface of tumor cells, further recruiting and activating NK cells via MICA-NKG2D pathway to strengthen the immunosurveillance. The novel fusion protein effectively circumvents tumor immune evasion in conventional antibody therapies, particularly within hypoxic environments, thereby significantly augmenting the antitumor efficacy of SHH002-hu1. The design represents a pioneering approach by integrating Wnt/β-Catenin signaling-targeted therapy with immune activation, thus introducing an innovative aspect to the field of related research.

Methods

Cell culture and transfection of siRNA

The cell culture method of MDA-MB-231/MDA-MB-468/MCF-10A can be referenced from the prior research conducted by us.18 The human TNBC cell line BT-20 was obtained from Dcell Biologics and cultured in MEM medium (Dcell Biologics), supplemented with 5% (v/v) FBS (Dcell Biologics). The human NK cell line NK92MI (express IL-2 and the high affinity CD16 allele) was obtained from Dcell Biologics and cultured in MEM-α medium (Gibco, Grand Island, USA), supplemented with 0.2 mM inositol+0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol+0.02 mM folic acid (SigmaAldrich)+12.5% horse serum (Gibco, Auckland, New Zealand) + 12.5% FBS. The Chinese hamster ovary cell line ExpiCHO-S was obtained from Gibco and cultured in ExpiCHO expression medium. The human peripheral blood mononuclear cells were obtained by density gradient centrifugation from the whole blood of healthy donors. The EasySep Human NK Cell Enrichment Kit (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) was used for the isolation of primary NK cells (negative selection).

Homo NKG2D-specific siRNA was synthesized by Genepharma (Shanghai, China). The nucleotide target sequence for NKG2D (siNKG2D) was: 5’-CACUCUGUCAGUUGGUUUATT-3’. Then, the transfection was performed using Lipofectamine RNA iMAX reagent (Invitrogen, California, USA).

Construction and expression of SHH002-hu1-MICA

The human MICA extracellular 1–3 domain (GenBank accession number: NM_001289153.1) was fused to the carboxy terminus of the heavy chain of SHH002-hu1 with a flexible pentapeptide (Gly-Gly-Gly-Gly-Ser). Subsequently, the recombinant plasmids were introduced into ExpiCHO-S cells for the expression of SHH002-hu1-MICA. The fusion protein was purified from culture supernatants using protein A affinity chromatography (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) and characterized by reducing and non-reducing SDS-PAGE/Western blot, followed by SEC-HPLC assay.

Binding affinity and kinetic analysis

The binding kinetics of SHH002-hu1-MICA to rhFzd7-His (SANGON, Shanghai, China)/rhNKG2D-Fc (R&D Systems, USA) was measured with Fortebio Octet Red96 (PALL, USA). First, SHH002-hu1-MICA was captured by the anti-Human Fab-CH1 second Generation Sensor (PALL, USA). Then, rhFzd7-His/rhNKG2D-Fc was injected at different concentrations into running buffer (KB buffer: 0.1% BSA+0.05% Tween 20 dissolved in PBS, pH 7.2), and capture was done. Sensorgrams were obtained at each concentration, and the association rate constant (ka) and dissociation rate constant (kd) were calculated. Finally, the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) was calculated from the ratio of rate constants kd/ka. To demonstrate whether SHH002-hu1-MICA could bind with rhFzd7-His and rhNKG2D-Fc, the SPR assay was executed using the Biacore T200 (Cytiva). rhFzd7 was injected after SHH002-hu1-MICA was flowed over the rhNKG2D-immobilized CM5 sensor chip (Cytiva).

Flow cytometry

For the detection of MICA protein located on the cell membrane, 3×105 MDA-MB-231/MDA-MB-468/BT-20 cells were cultured in 6-well plates under normoxic/hypoxic conditions with different treatments (100 nM SHH002-hu1/SHH002-hu1-MICA). After that, cells were incubated with the anti-MICA (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and FITC-conjugated Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (SANGON, Shanghai, China) before being analyzed by flow cytometry (FCM).

Degranulation of NK cells and cytotoxicity assay

Cyto Tox 96 non-radioactive cytotoxicity assay (Promega, Madison, USA) was performed based on the detection of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) released from target TNBCs. The normoxia TNBCs or hypoxia TNBCs (37℃, 5%CO2, 1%O2, 24 hours) were used as target cells, and normoxia NK cells were used as effect cells. The co-incubation was conducted in normoxic conditions for 4 hour. Controls were set as groups of spontaneous LDH release in effector or target (E/T) cells, as well as groups of target maximum release. The percentage of cell lysis was calculated as 100×([experimental−effector spontaneous−target spontaneous]/[target maximum−target spontaneous]). For the detection of NK cell degranulation, NK cells were co-incubated with TNBCs for 4 hours at an E/T ratio of 2.5:1. After the incubation of APC-conjugated Mouse anti-Human CD107a and FITC-conjugated Mouse anti-Human CD56 (BD Pharmingen), the degranulated NK cells were detected via FCM based on the release of lysosome-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP-1, CD107a).

Detection and sorting of CD44+/CD24- TNBCs

To detect the subpopulation of TNBCSCs, MDA-MB-231/MDA-MB-468/BT-20 cells cultured under normoxic (21% O2)/hypoxic (1% O2) conditions were incubated with APC-conjugated Mouse anti-Human CD44 and FITC-conjugated Mouse anti-Human CD24 (BD Pharmingen). After incubation, TNBCs were analyzed by FCM. For the sorting of TNBCSCs, CD24 Microbead Kit and CD44 Microbead Kit (Miltenyi Biotec) were used.

In vivo dynamics and targeting capability by near-infrared imaging

Female BALB/c-nude mice aged 5 weeks old were purchased from Shanghai Lab. Animal Research Center, China. MDA-MB-231 cells were injected into the mammary fat pads of mice to form transplanted tumors. The following can be referenced from the prior research conducted by us.18

Xenograft model and administration

The xenograft tumors were established as described above. When the average tumor volume reached 100 mm3 (MDA-MB-231/MDA-MB-468)/50 mm3 (BT-20), mice were randomized into five groups (n=5 for each group), and the administration began: (1) PBS control; (2) 5 mg/kg SHH002-hu1; (3) 5 mg/kg SHH002-hu1-MICA; (4) anti-Asialo GM1+5 mg/kg SHH002-hu1-MICA. SHH002-hu1/SHH002-hu1-MICA was administered intravenously every 3 days. Anti-Asialo GM1 (WAKO, Neuss, Germany) was administered intraperitoneally 100 µL per mouse at the beginning of the administration. Tumors were measured by digital calipers periodically, and the tumor volume was determined as V=(length×width2/2. At the end of drug treatment, the mice were humanely euthanized, and tumors were harvested for further studies.

Immunohistochemistry and IF analysis for TNBC tumor tissues

Paraffin sections were cut into 5 µm sections and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. For immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining, the sections were incubated with anti-c-Myc (CST, MA, USA)/anti-VEGFA (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and HRP-labeled secondary antibody (SANGON, Shanghai, China), and analyzed through Vectastain ABC Kit (Dako, Copenhagen, Denmark). For IF staining, the sections were incubated with anti-β-Catenin (CST, MA, USA), and followed by FITC-conjugated secondary antibody.

Multicolor IHC

The human TNBC tissue microarray (TMA) was obtained from OUTDO BIOTECH CO. (Shanghai, China). The antibodies used in this section were: anti-HIF-1α (CST, Massachusetts, USA), anti-MICA, and anti-NCAM-1 (CD56, Novus, Canada). The antigenic binding sites were visualized using the Opal 7-Color Manual IHC Kit (PerkinElmer, NEL811001KT) according to the protocol of the manufacturer. After each antigen retrieval, slides were stained with antigen-specific primary antibodies followed by Opal Polymer (secondary antibody). Application of the Opal tyramide signal amplification created a covalent bond between the fluorophore and the tissue at the site of the HRP. After all seven sequential reactions, sections were counterstained with DAPI and mounted with Vectashield fluorescence mounting medium (Vector Labs, Burlingame, California, USA). For multicolor IHC of the transplanted TNBC tumor tissues, the specimens were collected and prepared for the formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections as previously mentioned. The antibodies used in this section were anti-Fzd7, anti-MICA, anti-HIF-1α, anti-CD44 and anti-NK1.1 (CD161, CST, USA).

Statistics and reproducibility

All the quantitative data were expressed as the mean±SD, and all experiments were independently repeated at least three times. Student’s t-test and analysis of variance were used to determine significant differences. GraphPad Prism (V.10) was used to analyze statistical differences in data, p<0.05 represented that the difference was statistically significant

Results

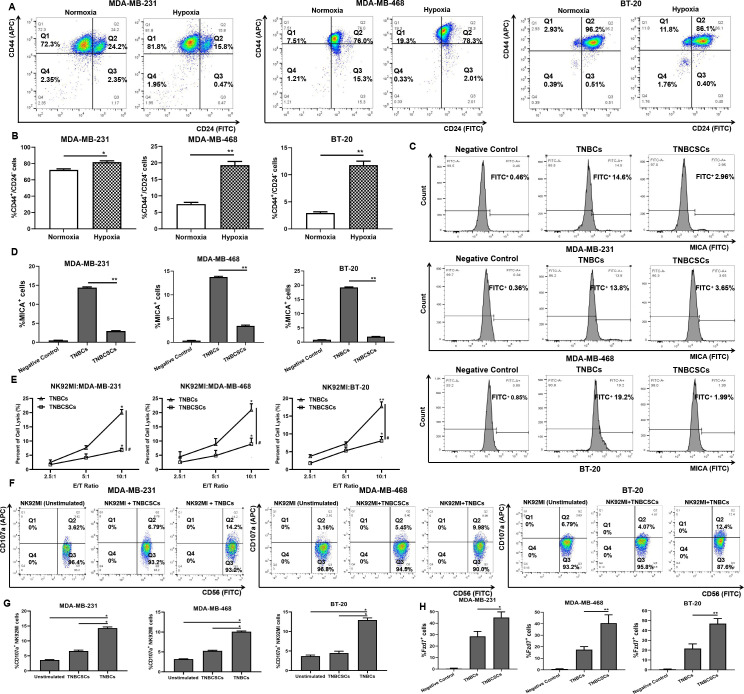

The level of membrane MICA is downregulated under hypoxic conditions, leading to impaired killing of TNBCs by NK cells

The tumor tissue of TNBC is frequently characterized by significant hypoxia, and the hypoxic microenvironment facilitates tumor immune evasion through various regulatory mechanisms, including decreasing the expression of membrane MICA (mMICA).28 Here, Opal multicolor IHC staining of TNBC TMA indicated that, in the hypoxic region of tumor tissue, there was a significant downregulation in the expression of mMICA, leading to a notable reduction in the infiltration of NK cells (figure 1A). Subsequently, mMICA expression of TNBC cell lines was confirmed to be significantly reduced under hypoxic conditions via FCM (figure 1B,C). The NK92MI cells were co-cultured with normoxic/hypoxic TNBCs, then the Cyto Tox 96 non-radioactive cytotoxicity assay was conducted to assess the NK92MI cells-mediated killing of TNBCs. Assessing NK92MI cell-mediated killing at different E/T ratios exhibited that, compared with TNBCs under normoxic condition, the cellular cytotoxicity triggered by NK92MI cells toward TNBCs under hypoxic condition was remarkably diminished (figure 1D). Moreover, NK cell degranulation detected by FCM after co-incubation revealed that TNBCs under hypoxia significantly suppressed the activation of NK92MI cells compared with those under normoxia (figure 1E,F). In addition, online supplemental figure 1A–C showed that primary NK cells exhibited similar behavior with NK92MI.

Figure 1. Hypoxia downregulates the level of mMICA and impairs the killing of TNBCs by NK cells. (A) Opal multicolor IHC staining to validate the existence of NK cells in normoxic/hypoxic areas of human TNBC tumors (exemplified by 18S27111 and 18S28408). Staining showed HIF-1α (green), MICA (red) and CD56 (orange) merged with DAPI-stained nuclei (blue), bar=20 µm. (B) FCM assay to detect the expression level of mMICA on TNBCs cultured under hypoxic/normoxic conditions. (C) Quantitative analysis of the percentage of MICA+ TNBCs. Data were presented as the mean±SD, n=3, *p<0.05, **p<0.01. (D) Cytotoxicity assay to assess the NK92MI cells-mediated killing of TNBCs cultured under hypoxic/normoxic condition. The normoxia/hypoxia TNBCs were used as target cells, and normoxia NK92MI cells were used as effect cells, the co-incubation was sustained for a duration of 4 hours in normoxic conditions. Data were presented as the mean±SD, n=3, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, vs the previous E/T ratio; #p<0.05, ##p<0.01, hypoxia group vs normoxia group. (E) FCM analysis of CD107a expression on NK92MI cells after exposure to TNBCs cultured under hypoxic/normoxic condition. The E/T ratio was 2.5:1. (F) Quantitative analysis of the percentage of CD107a+ NK92MI cells. Data were presented as the mean±SD, n=3, *p<0.05, **p<0.01. E/T, effector-target; FCM, flow cytometry; IHC, immunohistochemistry; NK, natural killer; TNBC, triple-negative breast cancer.

TNBCSCs demonstrate an enhanced capacity to evade the immune surveillance exerted by NK cells

Hypoxia has been shown to be a key regulator of CSCs.29 Increasing evidence indicated that immunosuppressive TME and immunoevasion are considered the culprits in the occurrence of CSCs.30 31 Here, FCM was used to determine the proportion of CSCs in TNBCs under hypoxic conditions. CD44+/CD24− breast cancer CSCs are associated with a mesenchymal-like phenotype, and ALDH1+ breast cancer CSCs exhibit an epithelial-like phenotype.32 33 Figure 2A,B and online supplemental figure 2 indicate that, after cultured under hypoxic conditions, both the proportion of CD44+/CD24− TNBCs and the proportion of ALDH1+ TNBCs were significantly increased. Then, the CD44+/CD24− TNBCs were sorted out. The FCM assay revealed that the expression of mMICA was markedly reduced on TNBCSCs (figure 2C,D). Subsequently, NK92MI cells and primary NK cells were confirmed to mediate inferior cytotoxicity to TNBCSCs through the Cyto Tox 96 non-radioactive cytotoxicity assay (figure 2E and online supplemental figure 1D). In addition, compared with TNBCs, TNBCs significantly suppressed NK cell degranulation, thereby substantially impairing NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity (figure 2F,G and online supplemental figure 1E,F).

Figure 2. TNBCSCs exhibit a higher propensity to evade the immune surveillance of NK cells. (A) FCM assay to detect the proportion of CD44+/CD24− MDA-MB-231/MDA-MB-468/BT-20 cells cultured under hypoxic/normoxic conditions. (B) Quantitative analysis of the percentage of CD44+/CD24− TNBCs. Data were presented as the mean±SD, n=3, *p<0.05, **p<0.01. (C) FCM assay to detect the expression level of mMICA on TNBCs and TNBCSCs. (D) Quantitative analysis of the percentage of MICA+ TNBCs/TNBCSCs. Data were presented as the mean±SD, n=3, **p<0.01. (E) Cytotoxicity assay to assess the NK92MI cells-mediated killing of TNBCs/TNBCSCs. Data were presented as the mean±SD, n=3, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, vs the previous E/T ratio; #p<0.05, TNBCs group vs TNBCSCs group. (F) FCM analysis of CD107a expression on NK92MI cells after exposure to TNBCs/TNBCSCs. The E/T ratio was 2.5:1. (G) Quantitative analysis of the percentage of CD107a+ NK92MI cells. Data were presented as the mean±SD, n=3, *p<0.05. (H) FCM assay to detect the percentage of Fzd7+ cells. Data were presented as the mean±SD, n=3, *p<0.05, **p<0.01. E/T, effector-target; FCM, flow cytometry; NK, natural killer; TNBCSCs, triple-negative breast cancer stem-like cells.

The expression of Fzd7 is upregulated in TNBCSCs and the infiltration rate of NK cells decreases in Fzd7high tumor regions

FCM analysis confirmed the expression of Fzd7 was significantly increased in TNBCSCs relative to TNBCs (figure 2H and online supplemental figure 3). Through multicolor immunofluorescence analysis of Fzd7, MICA, and CD56 in TNBC TMA, we have observed that, in tumor regions characterized by high Fzd7 expression, the expression level of mMICA was diminished accompanied by a compromised infiltration of NK cells; in contrast, the expression of mMICA was higher in tumor regions with low Fzd7 expression, accompanied by a moderate infiltration of NK cells (online supplemental figure 4), indicating Fzd7 is a promising target involved in Wnt/β-Catenin signaling for tumor immunotherapy.

Generation and identification of SHH002-hu1-MICA

The cDNA sequences of the heavy chain of SHH002-hu1 and human MICA extracellular 1–3 domain were synthesized using GGGGS (G4S) as a linker, and the newly acquired fusion gene was named H’-chain. The light chain of SHH002-hu1-MICA (L’-chain) retained the same gene as that of SHH002-hu1. Figure 3A shows the structure diagram of SHH002-hu1-MICA. SDS-PAGE analysis of the purified SHH002-hu1-MICA showed H’-chain (80 KD) and L’-chain (25 KD) of the expected molecular weight were expressed correctly (figure 3Bii) and assembled into complete fusion protein of 210 KD (theoretical molecular weight, figure 3Bi). Western blot analysis using anti-human IgG (H+L) (figure 3Ci,Cii) and anti-human MICA antibody (figure 3Ciii,Civ) confirmed that the complete fusion protein is indeed composed of two distinct components, SHH002-hu1 and MICA. BLI assay indicated that SHH002-hu1-MICA exhibits extremely high affinity with rhFzd7 (KD (M)<1.0×10−12), similar to that of SHH002-hu1 (KD (M)<1.0×10−12) (figure 3D). Meanwhile, SHH002-hu1-MICA shows a high affinity for rhNKG2D (KD (M): 4.52×10−8), which is slightly lower than that of rhMICA (KD (M): 1.26×10−9) (figure 3E and online supplemental table 1). Whether SHH002-hu1-MICA could effectively elicit NKG2D-mediated cytotoxicity toward TNBCs depends on the simultaneous binding to Fzd7 and NKG2D. Therefore, the SPR assay was carried out. As shown in figure 3F, when the concentration of flow analyte (rhFzd7) was 500 nM, a significant binding signal was observed, indicating the ability of rhFzd7 to bind to the protein complex SHH002-hu1-MICA-rhNKG2D.

Figure 3. Generation and identification of the fusion protein SHH002-hu1-MICA. (A) Structure diagram of SHH002-hu1-MICA. (B) SDS-PAGE analysis of SHH002-hu1-MICA. ⅰ: Non-reducing, Lane 1/2: SHH002-hu1; Lane 3/4: SHH002-hu1-MICA; ⅱ: Reducing, Lane 1/2: SHH002-hu1-MICA; Lane 3/4: SHH002-hu1. (C) Western blot analysis for the assembling of SHH002-hu1-MICA. i: anti-Human IgG (H+L) under non-reducing condition; ⅱ: anti-Human IgG (H+L) under reducing condition; ⅲ: anti-MICA under non-reducing condition; ⅳ: anti-MICA under reducing condition. Lane 1: SHH002-hu1, Lane 2: SHH002-hu1-MICA. (D) Set of sensorgrams of rhFzd7-His binding with SHH002-hu1-MICA and SHH002-hu1. The concentration of rhFzd7-His (from bottom to top), ranged from 15.625 to 1000 nM. (E) Set of sensorgrams of rhNKG2D-Fc binding with SHH002-hu1-MICA and rhMICA-His. For SHH002-hu1-MICA, the concentration of rhNKG2D-Fc (from bottom to top), ranged from 33.3 to 300 nM. For rhMICA-His, rhNKG2D-Fc was captured by the anti-Human IgG Fc Capture (AHCSensor), and rhMICA-His was injected at different concentrations (1.23, 3.69, 11.1 nM) into running buffer. (F) rhFzd7-His was injected after SHH002-hu1-MICA was flowed over the rhNKG2D-immobilized sensor chip. (G) NIRB imaging assay to evaluate the bio-distribution of NIRB-SHH002-hu1-MICA in MDA-MB-231 bearing nude mice. In blocking experiments, free SHH002-hu1-MICA inhibited the probes from binding to the tumor sites. (H) Quantitative analysis of tumor fluorescence signal. Data were given as the mean±SD (n=5). (I) Tumor/normal tissue ratios calculated at 12 hours postinjection of probe groups into MDA-MB-231-bearing nude mice from the region of interest. Data were given as the mean±SD (n=5), **p<0.01.

SHH002-hu1-MICA selectively binds Fzd7+ TNBCs and specifically targets Fzd7+ TNBC tumor tissues

Western blot assay revealed minimal expression of Fzd7 on human mammary epithelial cell line MCF-10A, and the expression of Fzd7 protein is significantly elevated in TNBC cell lines (online supplemental figure 5A). Subsequently, IF assay demonstrated the selective binding of SHH002-hu1-MICA to MDA-MB-231/MDA-MB-468/BT-20 cells, rather than MCF-10A cells (online supplemental figure 5B). Next, near-infrared (NIR) imaging was used to assess the targeting capability of NIRB-SHH002-hu1-MICA in vivo. After the administration of NIRB-SHH002-hu1-MICA, fluorescent signals rapidly disseminated throughout the entire organism. Six hours later, the MDA-MB-231 xenograft was distinguished by fluorescence. The fluorescence signal was sustained for a duration of 36 hours. Meanwhile, the blocking group showed no intense fluorescent signals at the tumor site, indicating that tumor targeting was mediated by SHH002-hu1-MICA (figure 3G,H). The fluorescent signals were significantly different, with a maximal tumor/normal tissue ratio at 12 hours of 8.56 and 0.14 for the NIRB-SHH002-hu1-MICA treated group and its blocking group, respectively (figure 3I).

SHH002-hu1-MICA augments the cytotoxicity of NK cells against TNBCs cultured under hypoxic condition

Cyto Tox 96 non-radioactive cytotoxicity assay indicated that the killing effect of NK92MI cells on hypoxic TNBCs was significantly enhanced by both SHH002-hu1 and SHH002-hu1-MICA. Assessing NK92MI cell-mediated killing showed SHH002-hu1-MICA exerts stronger cytotoxicity than SHH002-hu1 (figure 4A). The lysis rate of MDA-MB-231 cells in the SHH002-hu1-MICA group exhibited a significant difference compared with the control (##p<0.01)/SHH002-hu1 group (##p<0.01). As anticipated, SHH002-hu1-MICA also demonstrated a potent ability to induce the cytotoxic effect of NK92MI cells on normoxic TNBCs, surpassing the efficacy of SHH002-hu1 (online supplemental figure 5C). Figure 4B shows that the expression of mMICA was significantly upregulated following the addition of SHH002-hu1-MICA in TNBC cell lines under hypoxic conditions. The MICA+ MDA-MB-231 cells were 30.3% for the SHH002-hu1-MICA group, while it was 4.39% and 4.88% for the control/SHH002-hu1 group, respectively (figure 4C). Additionally, following incubation of NK92MI cells with hypoxic TNBCs, FCM was employed to assess the degranulation of NK92MI cells. The proportion of activated NK92MI cells in the SHH002-hu1-MICA group was remarkably increased compared with the control group or SHH002-hu1 group (figure 4D,E). Furthermore, in online supplemental figure 6, primary NK showed similar cytotoxicity of NK92MI against TNBCs. In conclusion, SHH002-hu1-MICA enhances the cytotoxicity of NK cells against hypoxic TNBCs by increasing mMICA levels in TNBCs.

Figure 4. SHH002-hu1-MICA enhances the cytotoxicity of NK92MI cells against TNBCs cultured under hypoxic conditions. (A) Cytotoxicity assay to assess the effects of SHH002-hu1-MICA on NK92MI cells-mediated killing of TNBCs. Data were presented as the mean±SD, n=3, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, vs the previous E/T ratio; #p<0.05, ##p<0.01, group comparison. (B) FCM assay to detect the effects of SHH002-hu1-MICA on the level of TNBCs mMICA. (C) Quantitative analysis of the percentage of MICA+ TNBCs. Data were presented as the mean±SD, n=3, **p<0.01. (D) FCM assay to analyze the effects of SHH002-hu1-MICA on CD107a expression of NK92MI cells co-incubated with TNBCs. The E/T ratio was 2.5:1. (E) Quantitative analysis of the percentage of CD107a+ NK92MI cells. Data were presented as the mean±SD, n=3, *p<0.05, **p<0.01. E/T, effector-target; FCM, flow cytometry; TNBC, triple-negative breast cancer.

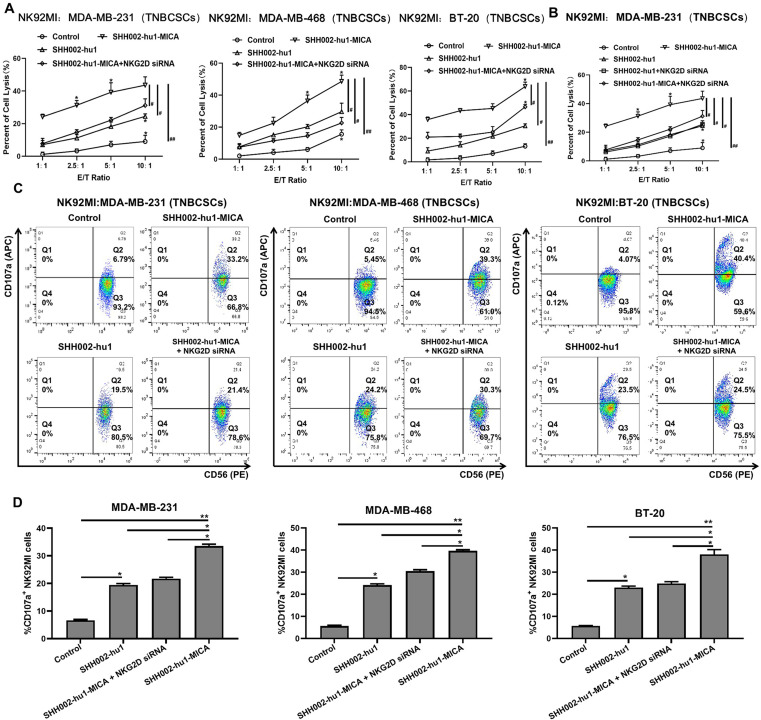

SHH002-hu1-MICA enhances the cytotoxicity of NK cells against TNBCSCs via MICA-NKG2D axis

The tumor tissues of TNBC often exhibit significant hypoxia, leading to the activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, thereby augmenting the proportion of TNBCSCs.34 The shedding of MICA by TNBCSCs is comparatively higher than that of NSCs, facilitating the compromised functionality of MICA-NKG2D, rendering them more susceptible to immune escape.4 Therefore, it is crucial to investigate whether SHH002-hu1-MICA can reinstate the immune surveillance of NK cells against TNBCSCs. Cyto Tox 96 non-radioactive cytotoxicity assay indicated that both SHH002-hu1 and SHH002-hu1-MICA significantly enhance the cytotoxicity of NK92MI cells and primary NK cells against TNBCSCs in an E/T ratio-dependent manner (from 1:1 to 10:1), with the effect of SHH002-hu1-MICA being more pronounced (figure 5A,B and online supplemental figure 7A,B). Taking MDA-MB-468 cells as an example, the TNBCSCs lysis rate of the SHH002-hu1-MICA group significantly differed from that of the control (##p<0.01)/SHH002-hu1 group (#p<0.05), suggesting that the inclusion of MICA semimolecule plays a crucial regulatory role for NK cell-mediated immune surveillance. When the expression of NKG2D was suppressed by NKG2D-specific siRNA in NK cells, the cytotoxicity of NK cells toward TNBCSCs exhibited a significant reduction compared with that observed in the SHH002-hu1-MICA group. Furthermore, the NK cell degranulation assay demonstrated that, compared with SHH002-hu1, SHH002-hu1-MICA exhibited superior efficacy in stimulating the activation of NK92MI/primary NK cells, and this effect was significantly attenuated when the NKG2D expression of NK92MI/primary NK cells was knocked down. NKG2D-silenced NK92MI/primary NK cells exhibit significantly reduced sensitivity to SHH002-hu1-MICA compared with NK cells (figure 5C,D and online supplemental figure 7C,D), indicating that the fusion protein significantly enhances the immune surveillance of NK cells against TNBCSCs through the MICA-NKG2D axis.

Figure 5. SHH002-hu1-MICA enhances the cytotoxicity of NK92MI cells against TNBCSCs. (A) Cytotoxicity assay to assess the effects of SHH002-hu1-MICA on NK92MI cells-mediated killing of TNBCSCs. NKG2D siRNA was set to verify the MICA-NKG2D axis mediated cytotoxicity. Data were presented as the mean±SD, n=3, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, vs the previous E/T ratio; #p<0.05, ##p<0.01, group comparison. (B) Cytotoxicity assay to assess whether blocking MICA-NKG2D interaction could affect the ADCC function of SHH002-hu1. Data were presented as the mean±SD, n=3, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, vs the previous E/T ratio; #p<0.05, ##p<0.01, group comparison. (C) FCM assay to analyze the effects of SHH002-hu1-MICA on CD107a expression of NK92MI cells co-incubated with TNBCSCs. (D) Quantitative analysis of the percentage of CD107a+ NK92MI cells. Data were presented as the mean±SD, n=3, *p<0.05, **p<0.01. ADCC, antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity; E/T, effector-target; TNBCSCs, triple-negative breast cancer stem-like cells.

We further checked whether wtNK92, which lacks the expression of CD16, could perform SHH002-hu1-MICA-mediated cytotoxicity against TNBCs. The results showed that SHH002-hu1-MICA enhanced the cytotoxicity of wtNK92 cells against TNBCs, whereas SHH002-hu1 did not exhibit such enhancement (online supplemental figure 8A–C). Moreover, wtNK92 cell degranulation was detected by FCM after co-incubation with MDA-MB-231 cells. As shown in online supplemental figure 8D,E, TNBCs treated by SHH002-hu1-MICA significantly increased the activation of wtNK92 cells compared with the control/SHH002-hu1 group. The above further demonstrates that SHH002-hu1-MICA enhances the cytotoxicity of wtNK92 cells against TNBCs mainly depending on the NKG2D pathway. On refocusing on NK92MI as the effector, we observed that SHH002-hu1-MICA-mediated cytotoxicity was stronger compared with that of wtNK92 cells (online supplemental figure 5C), indicating that the Fc fragment is also involved in mediating the physiological effect of SHH002-hu1-MICA via antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC).

SHH002-hu1-MICA maintains the blocking effect of SHH002-hu1 on Wnt/β-Catenin signaling and exhibits superior antitumor activities than SHH002-hu1 in human TNBC xenografts

SHH002-hu1-MICA, as well as SHH002-hu1, significantly inhibited Wnt3a-induced migration and invasion of MDA-MB-231/MDA-MB-468 cells (online supplemental figure 9). Western blot assay demonstrated that SHH002-hu1-MICA/SHH002-hu1 not only impaired the nuclear translocation and accumulation of β-Catenin, but also suppressed the phosphorylation of LRP6 induced by Wnt3a. In addition, c-Myc, VEGFA and CD44, crucial downstream targets of Wnt/β-Catenin signaling pathway, were also markedly downregulated by SHH002-hu1-MICA/SHH002-hu1 (online supplemental figure 10A). Online supplemental figure 10B reveals that the stimulated epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) of TNBCs induced by Wnt3a was significantly weakened, along with the attenuated Wnt/β-Catenin pathway caused by SHH002-hu1-MICA.

The integrated antitumor activities in vivo of SHH002-hu1-MICA were assessed using human TNBC xenografts in nude mice. The treatment of 5 mg/kg SHH002-hu1-MICA or 5 mg/kg SHH002-hu1 resulted in significant inhibition of growth in MDA-MB-231/MDA-MB-468/BT-20 xenografts, compared with the PBS control. Notably, SHH002-hu1-MICA exhibited stronger anti-TNBC effects than SHH002-hu1 (figure 6A,B). The antitumor efficacy of SHH002-hu1-MICA was significantly attenuated on depletion of mouse NK cells using anti-Asialo GM1, suggesting the enhanced anti-tumor efficacy of SHH002-hu1-MICA is dependent on the activity of NK cells (figure 6A,B). Figure 6C and online supplemental figure 11A show that SHH002-hu1-MICA/SHH002-hu1 not only effectively impaired the nuclear translocation of β-Catenin, but also downregulated the expression of total β-Catenin, accompanied by a notable decrease in c-Myc/VEGFA staining (figure 6D and online supplemental figure 11B).

Figure 6. SHH002-hu1-MICA exhibits superior antitumor activities than SHH002-hu1 in human TNBC-bearing nude mice model. (A) Representative images of isolated tumors from MDA-MB-231/MDA-MB-468/BT-20 tumor-bearing nude mice. The anti-Asialo GM1 was administered to deplete NK cells in mice. (B) MDA-MB-231/MDA-MB-468/BT-20 tumor growth curves. Data were given as the mean ± SD (n=5), *p<0.05, **p<0.01. (C) IF staining of β-Catenin (green fluorescence) on paraffin sections of MDA-MB-231/MDA-MB-468 xenografted tumors, bar=20 µm. (D) IHC staining of c-Myc and VEGFA (brown staining) on paraffin sections of MDA-MB-231/MDA-MB-468 xenografted tumors, bar=100 µm. IHC, immunohistochemistry; NK, natural killer; TNBC, triple-negative breast cancer.

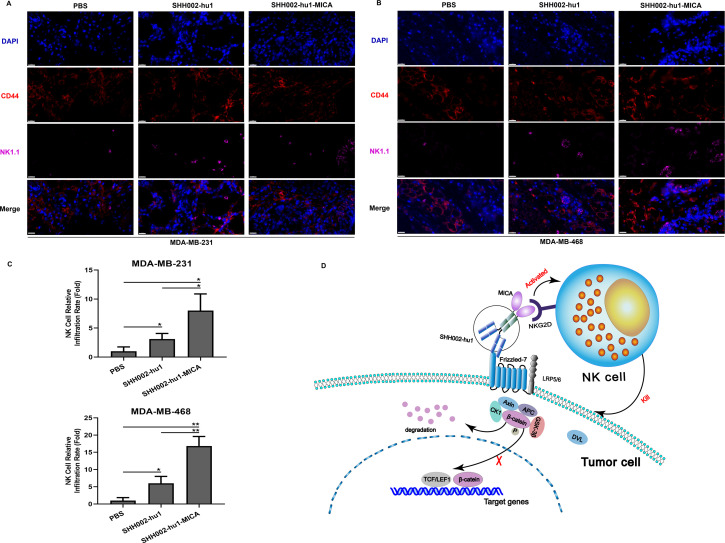

SHH002-hu1-MICA significantly promotes the infiltration of NK cells in CD44high regions within TNBC xenograft tumors

Opal multicolor IHC staining assay revealed that MDA-MB-231/MDA-MB-468/BT-20 xenograft tumors displayed multiple areas of intense hypoxia as determined by HIF-1α staining. Further assessing the spatial relationship between Fzd7+ cells and areas of hypoxia within TNBC tumors, we observed high-density areas of Fzd7+ cells within hypoxic regions. The expression level of Fzd7 in the normoxic regions of TNBC was markedly diminished, presenting a notable contrast (online supplemental figure 12A and 13A). Besides, the mesenchymal-like CSCs, strongly implicated in tumor invasion and immunoevasion, are characterized by the CD44+ phenotype. Online supplemental figures 12A and 13A indicate that CD44 staining exhibited co-localization with HIF-1α/Fzd7 staining. Online supplemental figures 12B and 13B show that, in TNBC tumor regions characterized by high CD44 expression, TNBCs exhibited elevated Fzd7 and diminished mMICA expression; conversely, in regions with low CD44 expression, the expression of Fzd7 was correspondingly decreased, while the mMICA expression was significantly heightened. The above results were consistent with the previous FCM assay, further demonstrating that the Fzd7-targeting antibody fused with MICA has the capability to enhance the mMICA level on TNBCSCs.

The infiltration of NK cells in TNBC transplanted tumor tissues was subsequently detected in each group. Figure 7A–C and online supplemental figure 13C,D show that both SHH002-hu1-MICA and SHH002-hu1 significantly enhance the infiltration of NK cells in the TNBC tumor regions with high CD44 expression. Moreover, the infiltration rate of NK cells induced by SHH002-hu1-MICA was significantly higher compared with that of SHH002-hu1. Chemokines C-C motif ligand 5 (CCL5) and C-X-C motif ligand 9 (CXCL9) are crucial for tumor infiltration of NK cells.35 The results of the cytokine test (online supplemental figure 14A,B) indicate that SHH002-hu1-MICA markedly increased the secretion level of CCL5 and CXCL9 in the co-incubation system. Furthermore, online supplemental figure 14C,D show that SHH002-hu1-MICA significantly enhanced the release of granzyme B and perforin of NK cells. To sum up, SHH002-hu1-MICA functions as an effective NK cell engager, facilitating the interaction between NK cells and TNBCs, especially TNBCSCs, and inducing the cytotoxicity of NK cells.

Figure 7. SHH002-hu1-MICA remarkably induces the infiltration of NK cells in CD44high areas of MDA-MB-231/MDA-MB-468 xenografted tumors. (A, B) Opal multicolor IHC staining to detect the infiltration of NK cells in CD44high areas of MDA-MB-231/MDA-MB-468 xenografted tumors. Staining showed CD44 (red) and NK1.1 (purple) merged with DAPI-stained nuclei (blue), bar=20 µm. (C) Quantitative analysis of NK cell relative infiltration rate. Data were presented as the mean±SD, n=3, *p<0.05, **p<0.01. (D) Schematic illustration delineating the role of SHH002-hu1-MICA in TNBC. IHC, immunohistochemistry; TNBC, triple-negative breast cancer.

Discussion

MICA and MICB are poorly expressed on normal cells but become upregulated on the surface of damaged, transformed, or infected cells.36 37 Theoretically, it is challenging for MICA+ tumor cells to evade the immune mechanism. The significantly elevated level of soluble MICA (sMICA) in serum has been observed to impair the function of NK cells. Further studies have revealed that sMICA is generated through the shedding of surface-bound MICA on tumor cells, enabling tumor immune evasion.38,40 The regulation of NKG2D/NKG2DL axis to enhance tumor immune surveillance is currently a prominent research focus in the field of tumor immunotherapy.41,44 The anti-MICA antibodies can enhance the ADCC and antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis effects, thereby augmenting tumor immune surveillance.11 45 46 Moreover, NGK2D/NKG2DL axis-based adoptive cell therapy has exhibited promising efficacy against hematological malignancies and solid tumors in numerous clinical trials.47,49 Despite the significant advancements in targeting the NKG2D-NKG2DL axis in immunotherapy, certain limitations persist, including inadequate specificity, off-target effects, exhaustion, and dysfunction of engineered NK cells. Therefore, employing a tumor-specific antibody as a carrier to link the MICA protein with a flexible oligopeptide for the construction of a bifunctional protein is proposed. On one hand, the antibody component can selectively target tumor tissues and inhibit the oncogenic pathway; on the other hand, the MICA protein can be immobilized on the surface of tumor cells to stimulate NKG2D-mediated immunosurveillance (figure 7D). By considering both tumor targeting and enhanced immune surveillance aspects, this approach exhibits distinctive advantages and shows promising prospects for clinical translation.

Numerous studies have consistently demonstrated that the Wnt/β-Catenin pathway is significantly upregulated in TNBC, with Fzd7 exhibiting the most pronounced differential expression among other members of the Fzd protein family. In this study, Fzd7 was demonstrated to be upregulated in hypoxic regions and co-localized with HIF-1α via multicolor IHC (online supplemental figures 12A and 13A). The expression of Fzd7 was significantly upregulated in TNBCSCs, as demonstrated by FCM (figure 2H) and IHC (online supplemental figures 12B and 13B). Furthermore, the expression of Fzd7 exhibited a negative correlation with the expression of mMICA and the infiltration level of NK cells in human TNBC tissues (online supplemental figure 4), which suggested that Fzd7 is also associated with the immunosuppressive microenvironment and immune evasion. SHH002-hu1, a humanized antibody targeting Fzd7 generated by us, with selectivity towards Fzd7+ TNBC and the potential of disrupting Wnt/β-Catenin signaling is indicated as a good candidate for fusion with MICA protein. The novel fusion protein, which exhibits the potential to precisely target TNBC, particularly the hypoxic regions, could effectively enhance the expression of MICA on the surface of TNBCSCs, thereby facilitating NK cell infiltration and inducing immune surveillance mediated by NKG2D. After conducting prediction screening, we opted for the G4S flexible oligopeptide as the linker in this study.50

On accurate assembly, SHH002-hu1-MICA was demonstrated to show a strong affinity for rhFzd7 and rhNKG2D proteins. SHH002-hu1-MICA selectively binds Fzd7+ TNBCs, effectively suppresses EMT of TNBCs via blocking Wnt/β-Catenin signaling pathway, and augments the cytotoxicity of NK cells against TNBCs. SHH002-hu1-MICA, however, deserves greater scrutiny due to its potential to significantly enhance the cytotoxicity of NK cells against hypoxic TNBCs and TNBCSCs through increasing the mMICA level and inducing the degranulation of NK cells via the MICA-NKG2D axis. In vivo, SHH002-hu1-MICA specifically targets TNBC tumor tissues and promotes the infiltration of NK cells in CD44high regions within TNBC xenograft tumors, exhibiting superior antitumor activities than SHH002-hu1. The bifunctional protein designed based on the pivotal receptor of the Wnt/β-Catenin signaling pathway and the crucially activated receptor NKG2D that regulates the immune surveillance function of NK cells effectively addresses the issue of immune evasion in TNBCs, particularly TNBCSCs, by restoring the immune surveillance function mediated by the MICA-NKG2D axis. SHH002-hu1-MICA elicits an enhanced cytotoxicity when NK92MI functions as effector cells, compared with wtNK92, indicating that the Fc fragment also plays a crucial role in SHH002-hu1-MICA-mediated immune surveillance. In addition, the enhanced cytotoxicity of NK cells induced by SHH002-hu1-MICA against TNBCs cultured in hypoxic conditions, and significantly upregulation of Fzd7 in hypoxic regions of TNBC tissues, suggest the potential of SHH002-hu1-MICA to target the immunosuppressive TME, exert antitumor and NKG2D-mediated immunosurveillance effects within it.

In summary, the novel fusion protein SHH002-hu1-MICA maintains the targeting property and oncogenic signaling pathway blockade effect of SHH002-hu1,18 successfully activates and retargets NK cells against resistant TNBCs, especially TNBCSCs, via MICA-NKG2D axis, exhibiting superior antitumor activities than SHH002-hu1 against TNBC. SHH002-hu1-MICA represents a promising new engager for NK cell-based immunotherapy for TNBC. The generation of SHH002-hu1-MICA establishes the theoretical foundation and technical framework for the integration of Wnt/β-Catenin signaling targeting and NKG2D-mediated immunosurveillance activation for tumor treatment, enriching the design concepts of antibody drugs and providing diverse functionalities for monoclonal antibodies that specifically target tumor markers.

Supplementary material

Acknowledgments

Thanks all support from Shanghai Key Laboratory of Molecular Imaging, Jiading District Central Hospital Affiliated Shanghai University of Medicine and Health Sciences.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (23ZR1427400); Key Clinical Program of Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (20214Y0516); Construction project of Shanghai Key Laboratory of Molecular Imaging (18DZ2260400) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (82127807).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: This study involves human participants and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Outdo Biotech Company (YB M-05-02) and the Medical Ethics Committee Shanghai First Maternity and Infant Hospital (KS22174). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it was first published online. The corresponding authorship has been updated.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1.Schmid P, Cortes J, Dent R, et al. Event-free Survival with Pembrolizumab in Early Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:556–67. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2112651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yi M, Zheng X, Niu M, et al. Combination strategies with PD-1/PD-L1 blockade: current advances and future directions. Mol Cancer. 2022;21:28. doi: 10.1186/s12943-021-01489-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yi M, Wu Y, Niu M, et al. Anti-TGF-β/PD-L1 bispecific antibody promotes T cell infiltration and exhibits enhanced antitumor activity in triple-negative breast cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 2022;10:e005543. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2022-005543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gong Y, Chen W, Chen X, et al. An Injectable Epigenetic Autophagic Modulatory Hydrogel for Boosting Umbilical Cord Blood NK Cell Therapy Prevents Postsurgical Relapse of Triple‐Negative Breast Cancer. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2022;9:e2201271. doi: 10.1002/advs.202201271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guillerey C, Huntington ND, Smyth MJ. Targeting natural killer cells in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:1025–36. doi: 10.1038/ni.3518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shimasaki N, Jain A, Campana D. NK cells for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020;19:200–18. doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kyrysyuk O, Wucherpfennig KW. Designing Cancer Immunotherapies That Engage T Cells and NK Cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2023;41:17–38. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-101921-044122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diefenbach A, Jensen ER, Jamieson AM, et al. Rae1 and H60 ligands of the NKG2D receptor stimulate tumour immunity. Nature New Biol. 2001;413:165–71. doi: 10.1038/35093109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morimoto Y, Yamashita N, Daimon T, et al. MUC1-C is a master regulator of MICA/B NKG2D ligand and exosome secretion in human cancer cells. J Immunother Cancer. 2023;11:e006238. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2022-006238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang B, Wang Q, Wang Z, et al. Metastatic consequences of immune escape from NK cell cytotoxicity by human breast cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2014;74:5746–57. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrari de Andrade L, Tay RE, Pan D, et al. Antibody-mediated inhibition of MICA and MICB shedding promotes NK cell–driven tumor immunity. Science. 2018;359:1537–42. doi: 10.1126/science.aao0505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zingoni A, Vulpis E, Loconte L, et al. NKG2D Ligand Shedding in Response to Stress: Role of ADAM10. Front Immunol. 2020;11:447. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pietrobon V, Marincola FM. Hypoxia and the phenomenon of immune exclusion. J Transl Med. 2021;19:9. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02667-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ni J, Wang X, Stojanovic A, et al. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing of Tumor-Infiltrating NK Cells Reveals that Inhibition of Transcription Factor HIF-1α Unleashes NK Cell Activity. Immunity. 2020;52:1075–87. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chaturvedi P, Gilkes DM, Takano N, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-dependent signaling between triple-negative breast cancer cells and mesenchymal stem cells promotes macrophage recruitment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:E2120–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1406655111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma S, Zhao Y, Lee WC, et al. Hypoxia induces HIF1α-dependent epigenetic vulnerability in triple negative breast cancer to confer immune effector dysfunction and resistance to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. Nat Commun. 2022;13:4118. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-31764-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barsoum IB, Hamilton TK, Li X, et al. Hypoxia induces escape from innate immunity in cancer cells via increased expression of ADAM10: role of nitric oxide. Cancer Res. 2011;71:7433–41. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xie W, Zhao H, Wang F, et al. A novel humanized Frizzled-7-targeting antibody enhances antitumor effects of Bevacizumab against triple-negative breast cancer via blocking Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2021;40:30. doi: 10.1186/s13046-020-01800-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conley SJ, Gheordunescu E, Kakarala P, et al. Antiangiogenic agents increase breast cancer stem cells via the generation of tumor hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:2784–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018866109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang L, Wu X, Wang Y, et al. FZD7 has a critical role in cell proliferation in triple negative breast cancer. Oncogene. 2011;30:4437–46. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang J, Dang MN, Day ES. Inhibition of Wnt signaling by Frizzled7 antibody-coated nanoshells sensitizes triple-negative breast cancer cells to the autophagy regulator chloroquine. Nano Res. 2020;13:1693–703. doi: 10.1007/s12274-020-2795-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nusse R, Clevers H. Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling, Disease, and Emerging Therapeutic Modalities. Cell. 2017;169:985–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flanagan DJ, Barker N, Costanzo NSD, et al. Frizzled-7 Is Required for Wnt Signaling in Gastric Tumors with and Without Apc Mutations. Cancer Res. 2019;79:970–81. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Riley RS, Day ES. Frizzled7 Antibody-Functionalized Nanoshells Enable Multivalent Binding for Wnt Signaling Inhibition in Triple Negative Breast Cancer Cells. Small. 2017;13:10. doi: 10.1002/smll.201700544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li G, Su Q, Liu H, et al. Frizzled7 Promotes Epithelial-to-mesenchymal Transition and Stemness Via Activating Canonical Wnt/β-catenin Pathway in Gastric Cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 2018;14:280–93. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.23756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Y, Zhao G, Condello S, et al. Frizzled-7 Identifies Platinum-Tolerant Ovarian Cancer Cells Susceptible to Ferroptosis. Cancer Res. 2021;81:384–99. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li K, Mao S, Li X, et al. Frizzled-7-targeting antibody (SHH002-hu1) potently suppresses non-small-cell lung cancer via Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Cancer Sci. 2023;114:2109–22. doi: 10.1111/cas.15721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duan S, Guo W, Xu Z, et al. Natural killer group 2D receptor and its ligands in cancer immune escape. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:29. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-0956-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang L, Shi P, Zhao G, et al. Targeting cancer stem cell pathways for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5:8. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-0110-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mai Y, Su J, Yang C, et al. The strategies to cure cancer patients by eradicating cancer stem-like cells. Mol Cancer. 2023;22:171. doi: 10.1186/s12943-023-01867-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bayik D, Lathia JD. Cancer stem cell-immune cell crosstalk in tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2021;21:526–36. doi: 10.1038/s41568-021-00366-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park SY, Lee HE, Li H, et al. Heterogeneity for stem cell-related markers according to tumor subtype and histologic stage in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:876–87. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ginestier C, Hur MH, Charafe-Jauffret E, et al. ALDH1 is a marker of normal and malignant human mammary stem cells and a predictor of poor clinical outcome. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:555–67. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu X, Xie P, Hao N, et al. HIF-1–regulated expression of calreticulin promotes breast tumorigenesis and progression through Wnt/β-catenin pathway activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2021;118:e2109144118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2109144118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Santana-Hernández S, Suarez-Olmos J, Servitja S, et al. NK cell-triggered CCL5/IFNγ-CXCL9/10 axis underlies the clinical efficacy of neoadjuvant anti-HER2 antibodies in breast cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2024;43:10. doi: 10.1186/s13046-023-02918-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fuertes MB, Domaica CI, Zwirner NW. Leveraging NKG2D Ligands in Immuno-Oncology. Front Immunol. 2021;12:713158. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.713158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nausch N, Cerwenka A. NKG2D ligands in tumor immunity. Oncogene. 2008;27:5944–58. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Groh V, Rhinehart R, Secrist H, et al. Broad tumor-associated expression and recognition by tumor-derived gamma delta T cells of MICA and MICB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:6879–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu JD, Higgins LM, Steinle A, et al. Prevalent expression of the immunostimulatory MHC class I chain-related molecule is counteracted by shedding in prostate cancer. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:560–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI22206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee YS, Choi H, Cho H-R, et al. Downregulation of NKG2DLs by TGF-β in human lung cancer cells. BMC Immunol. 2021;22:44. doi: 10.1186/s12865-021-00434-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cornel AM, Dunnebach E, Hofman DA, et al. Epigenetic modulation of neuroblastoma enhances T cell and NK cell immunogenicity by inducing a tumor-cell lineage switch. J Immunother Cancer. 2022;10:e005002. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2022-005002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xia C, He Z, Cai Y, et al. Vorinostat upregulates MICA via the PI3K/Akt pathway to enhance the ability of natural killer cells to kill tumor cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2020;875:173057. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.173057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raeeszadeh-Sarmazdeh M, Do LD, Hritz BG. Metalloproteinases and Their Inhibitors: Potential for the Development of New Therapeutics. Cells. 2020;9:1313. doi: 10.3390/cells9051313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Camodeca C, Nuti E, Tepshi L, et al. Discovery of a new selective inhibitor of A Disintegrin And Metalloprotease 10 (ADAM-10) able to reduce the shedding of NKG2D ligands in Hodgkin’s lymphoma cell models. Eur J Med Chem. 2016;111:193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferrari de Andrade L, Kumar S, Luoma AM, et al. Inhibition of MICA and MICB Shedding Elicits NK-Cell-Mediated Immunity against Tumors Resistant to Cytotoxic T Cells. Cancer Immunol Res. 2020;8:769–80. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-19-0483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alves da Silva PH, Xing S, Kotini AG, et al. MICA/B antibody induces macrophage-mediated immunity against acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2022;139:205–16. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021011619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sallman DA, Kerre T, Havelange V, et al. CYAD-01, an autologous NKG2D-based CAR T-cell therapy, in relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukaemia and myelodysplastic syndromes or multiple myeloma (THINK): haematological cohorts of the dose escalation segment of a phase 1 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2023;10:e191–202. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(22)00378-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leivas A, Valeri A, Córdoba L, et al. NKG2D-CAR-transduced natural killer cells efficiently target multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 2021;11:146. doi: 10.1038/s41408-021-00537-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gong Y, Klein Wolterink RGJ, Wang J, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor natural killer (CAR-NK) cell design and engineering for cancer therapy. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14:73. doi: 10.1186/s13045-021-01083-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zettlitz KA, Salazar FB, Yamada RE, et al. 89Zr-ImmunoPET Shows Therapeutic Efficacy of Anti-CD20-IFNα Fusion Protein in a Murine B-cell Lymphoma Model. Mol Cancer Ther. 2022;21:607–15. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-21-0732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.