Abstract

C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12), often referred to as stromal cell–derived factor 1 (SDF-1), is a crucial factor for musculoskeletal biology. SDF-1 is a powerful chemokine that has been shown to have a significant impact on a variety of physiological functions, including tissue repair, homeostasis maintenance, and embryonic development. SDF-1 plays a dominant role in bone and cartilage metabolism. It directs mesenchymal stem cell migration, controls osteogenesis and chondrogenesis, promotes angiogenesis, and modifies the inflammatory environment. SDF-1 also acts as an inflammatory chemokine during joint inflammation, recruiting inflammatory mediators to act and cause bone and cartilage degradation, thus causing osteoarthritis. Age-related bone loss and osteoporosis is exacerbated by SDF-1, which is elevated in the peripheral circulation due to a phenomenon known as “senescence associated secretory phenotype” of SDF-1. SDF-1 is also implicated in cancer metastasis causing the spread of secondary malignancies. Thus, the aim of this review is to explore the complex methods by which SDF-1 affects the fine equilibrium of bone and cartilage metabolism, providing insight into its importance in both healthy and diseased conditions.

Keywords: SDF-1, CXCL12, Bone, Cartilage, Metabolism

Introduction

Chemokines are small, highly charged molecules that are either membrane-bound or released and have a molecular weight of 6–14 kDa (Baggiolini et al. 1997). Chemokines are proinflammatory cytokines because they can express themselves in inflammatory environments and attract leukocytes that mediate inflammatory reactions. They are not strictly pro inflammatory but also participate in cell/tissue homeostasis by regulating immune surveillance. One of these functions is the trafficking (circulation, recruitment, and dissemination) of immature lymphocytes and blood cells (Bajetto et al. 2001; Kim and Broxmeyer 1999). According to their structure, chemokines are categorized into four primary categories, CXC, CC, C, and CX3C, which can also be represented by Greek symbols such as α, β, γ, and δ (Bajetto et al. 2001). C chemokines have only two conserved cysteines and the others, CXC, CC, and CX3C, all have four. The first two cysteines in CC chemokines are near each other. In CXC, the first and second cysteines are separated by one amino acid. In CX3C, the first and second cysteines are separated by three amino acids. Specific receptors that belong to the seven-transmembrane receptor superfamily and interact with one another through coupled heterotrimeric G proteins mediate the activity of chemokines (Fig. 1). There are currently 18 known chemokine receptors: 6 CXC (CXCR 1–6), 10 CC (CCR 1–10), 1 CX3C (CX3CR1), and 1 C (XCR1) receptors (Bajetto et al. 2001; Horuk 2001).

Fig. 1.

Classification of the chemokine family by structure. Dots denote various amino acids; C stands for cysteine; X is an amino acid that is not cysteine

The CXC or alpha family, which includes stromal cell–derived factor‑1 (SDF-1), is identified by the single amino acid that separates the first two cysteines (Juarez et al. 2004). The stromal cell line ST2 generated from bone marrow (BM) was first used to clone SDF-1 (Shirozu et al. 1995; Tashiro et al. 1993). It was subsequently discovered to be a pre-B cell growth-stimulating factor (Nagasawa et al. 1994).

SDF-1 influences a number of physiological processes, including embryonic development and organ homeostasis. It is secreted by various organs such as the lungs, liver, bone marrow, and skin. SDF-1 is a powerful chemokine that has been shown to have a significant impact on a variety of physiological functions, including tissue regeneration and repair, chemotaxis and homeostasis maintenance, and embryonic development and organogenesis. It is crucial for the attraction, localization, maintenance, growth, and differentiation of musculoskeletal system progenitor stem cells as well as in various pathological conditions such as osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, sarcopenia, and cancer. Thus, the aim of this review is to discuss the various functions and roles of SDF-1 and CXCR4. Additionally, it provides evidence linking the SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling pathway to several physiological and pathological events related to the body.

Structure

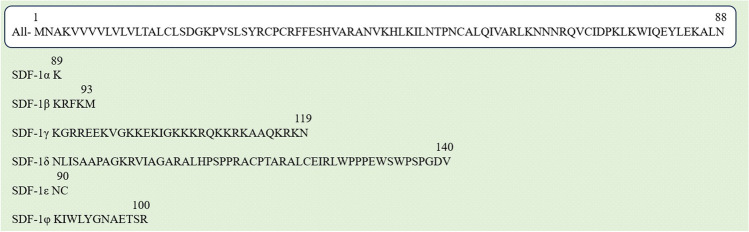

The structure of SDF-1, also known as C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12), refers to its molecular composition and arrangement. CXCL12 is a small protein composed of 89 amino acid residues. Human SDF-1 has six subtypes, i.e., SDF-1α (89 amino acids), SDF-1β (93 amino acids), SDF-1γ (119 amino acids), SDF-1δ (140 amino acids), SDF-1ε (90 amino acids), and SDF-1φ (100 amino acids), as shown in Fig. 2 (Döring et al. 2014). They have a common N-terminal amino acid sequence, but a different C-terminus amino acid sequence.

Fig. 2.

Six isoforms of SDF-1. They have a common N-terminal amino acid sequence (1–88), but a different C-terminus amino acid sequence. Letters indicate the specific amino acids. (glycine, G; alanine, A; leucine, L; methionine, M; phenylalanine, F; tryptophan, W; lysine, K; glutamine, Q; glutamic acid, E; serine, S; proline, P; valine, V; isoleucine, I; cysteine, C; tyrosine, Y; histidine, H; arginine, R; asparagine, N; aspartic acid, D; threonine, T)

There are two primary isoforms of SDF-1: SDF-1α, which is the most common and comprises 89 amino acids, and SDF-1β, which differs by 4 additional amino acids due to alternate splicing at the C-terminal end (Juarez et al. 2004; Shirozu et al. 1995). The structure of SDF-1 is characterized by its folding pattern, which gives rise to its three-dimensional conformation. The protein adopts a three-dimensional compact structure with an arrangement of alpha helices and beta strands (Crump et al. 1997; Dealwis et al. 1998; Thomas et al. 2017). These secondary structural elements contribute to the overall stability and function of the protein. Notably, while the primary structure of SDF-1 is well defined, the specific tertiary structure (the 3D arrangement of the protein) may vary depending on the experimental conditions and the presence of other molecules, such as ions or receptors, that interact with SDF-1. Many tissues, such as the brain, heart, kidney, thymus, liver, lung, lymph nodes, bone marrow, pancreas, spleen, ovary, and small intestine, constitutively express SDF-1 (Nagasawa et al. 1994; Shirozu et al. 1995; Tashiro et al. 1993; Thomas et al. 2017). SDF-1 only possesses one receptor, C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4), which was initially discovered to be a coreceptor for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) strains that are T cell line-tropic (Jazin et al. 1997). SDF-1 interaction with CXCR4 results in a variety of biological effects, some of which depend on the cell type and include an increase in integrin-mediated adhesion, chemotaxis, migration, enhanced survival, proliferation, and apoptosis (Horuk 2001).

Functions

Some of the known functions of SDF-1 are described as follows. They are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

A summary of the various functions and roles of SDF-1 according to various authors

| Functions of SDF-1 gene | Function | Authors |

|---|---|---|

| Chemotaxis | SDF-1 acts as a chemoattractant, guiding the migration of cells toward areas with higher SDF-1 concentrations | Dar et al. 2006; Ito 2011; Shyu et al. 2006 |

| Hematopoiesis | The survival, growth, and differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells into distinct blood cell lineages are all regulated by SDF-1 | Fröbel et al. 2021; Sugiyama et al. 2006; Wang and Wagers 2011 |

| Angiogenesis | SDF-1 attracts nucleus pulposus cells (NPCs) to sites of tissue injury or hypoxia, facilitating the growth of blood vessels and revascularization | Zhang et al. 2020 |

| Development and organogenesis | SDF-1 contributes to the development and organogenesis of various tissues and organs | Katsumoto and Kume 2013; Nagasawa et al. 1996; Sapède et al. 2005; Tachibana et al. 1998; Zou et al. 1998 |

| Tissue repair and regeneration | SDF-1 aids tissue healing and regeneration by helping to recruit stem and progenitor cells to the area of damage | Yuan et al. 2013 |

| Immune response | SDF-1 helps regulate the trafficking and positioning of immune cells within tissues | Isaacson et al. 2017; Schiwon et al. 2014 |

| Bone remodeling, repair, osteogenesis, and chondrogenesis | The regulatory chemokines SDF-1 (CXCL12) and CXCR4 are crucial for the attraction, localization, maintenance, growth, and differentiation of musculoskeletal system progenitor stem cells | Gilbert et al. 2019 |

| Cancer metastasis | While the SDF-1-CXCR7 axis is involved in angiogenesis and tumor formation, the SDF-1-CXCR4 axis stimulates the homing process by controlling cellular secretion and cell adhesion molecules | Burns et al. 2006 |

| Musculoskeletal diseases | Senescence-associated secretory phenotype causes SDF-1 levels to increase in plasma and decrease in bone marrow further causing osteoporosis | Gilbert et al. 2019 |

| Therapeutic application and future perspective | Scaffolds containing SDF-1 were engineered to provide a regulated release of this chemokine, which would draw in circulating or transplanted CD34 + stem cells and promote in situ tissue regeneration | Lau and Wang 2011 |

SDF-1 and chemotaxis

SDF-1 acts as a chemoattractant, guiding the migration of cells toward areas with higher SDF-1 concentrations (Dar et al. 2006; Ito 2011; Shyu et al. 2006). It primarily attracts stem cells, immune cells, and progenitor cells. Sperm can be drawn toward a single bovine cumulus-oocyte complex (COC), indicating that the COC releases sperm chemoattractants to draw them toward it. SDF-1 is seen in COCs, and its receptor, CXCR4, is seen in sperm, which has proven to be a potential chemoattractant (Umezu et al. 2020). Neural crest cells infiltrate inhibitor-free extracellular matrix corridors where Eph-ephrins group these cells into subpopulations. Once neural crest cells enter the extracellular matrix, they are ultimately activated by attractants such as SDF-1 or vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) (Bajanca et al. 2019). In the central nervous system (CNS), stem cells are present throughout life in the prosencephalon region and continue to produce neurons and glia in the hippocampal dentate gyrus and the subventricular zone (SVZ). Different kinds of CNS cell migration have been linked to SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling. Immunohistochemistry of the SVZ revealed that SDF-1 is expressed by ependymal cells and by the vasculature, two critical SVZ niches, thus causing the migration of CNS cells (Kokovay et al. 2010). SDF-1 also controls how multiple myeloma cells are directed to the bone marrow (Azab et al. 2009). Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 (Rac1) and Ras homolog gene family, member A (RhoA) GTPases, cause multiple myeloma cell adhesion, and their chemotaxis is affected by SDF-1. Thus, both Rac1 and RhoA play important roles in the SDF-1-induced adherence of multiple myeloma cells. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that SDF-1 promotes multiple myeloma cell proliferation by upregulation of very late activation antigen-4 (VLA-4) and mediates cell adhesion to fibronectin and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1). This enhances chemotaxis, invasion, and actin polymerization in multiple myeloma cells (Parmo-Cabañas et al. 2004).

SDF-1 and hematopoiesis

The production of new blood cells, or hematopoiesis, is regulated in part by SDF-1. The survival, growth, and differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells into distinct blood cell lineages are all supported by this process. Hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) interact with bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) to determine their fate (Bessy et al. 2021). HSPCs polarize in contact with BMSCs in response to SDF-1. The primary chemoattractant for murine hematopoietic stem cell homing and maintenance is the chemokine CXCL12 (SDF-1), which is the ligand of CXCR4 (Fröbel et al. 2021; Sugiyama et al. 2006; Wang and Wagers 2011). The vascular network and the bone matrix in the bone marrow function as local niches that transmit unique signals through SDF-1 that control the quiescence, proliferation, and differentiation of HSPCs. Elevation of SDF-1 levels in the blood causes VEGF-A-mediated increase in megakaryocytes which causes an increase in platelet formation. It is one of the first chemokines associated with the megakaryocyte-mediated platelet formation (Thon 2014).

SDF-1 and angiogenesis

The process of angiogenesis, or the development of new blood vessels, is greatly aided by SDF-1 (Petit et al. 2007). SDF-1 attracts nucleus pulposus cells (NPCs) to sites of tissue injury or hypoxia, facilitating the growth of blood vessels and revascularization. It causes the proliferation and angiogenesis of vascular endothelial cells (VECs), causing their migration and invasion to form new blood vessels. In degenerated discs, the SDF-1/CXCR4 axis in primary NPCs increases angiogenesis. It is done by regulating the PTEN/phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/AKT pathway (Zhang et al. 2020). Ischemia increases SDF-1 levels. This leads to increased endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) leading to angiogenesis via a heme oxygenase 1–dependent mechanism in the injured tissue (Deshane et al. 2007).

SDF-1 and development and organogenesis

SDF-1 contributes to the development and organogenesis of various tissues and organs. It guides the migration of cells during embryonic development, ensuring proper tissue patterning and organ formation. SDF-1 plays a significant role in developing the central nervous system, cardiovascular system, and vascular system, among other structures. FGF regulates expression of SDF-1α and its receptors CXCR4a, CXCR4b, and CXCR7. Through this expression, SDF-1 aids in tissue regeneration (Bouzaffour et al. 2009). It also plays a very important role in embryonic development. Mutations in the SDF-1 or CXCR4 genes are lethal in response to defects in neurogenesis, angiogenesis, cardiogenesis, myelopoiesis, lymphopoiesis, and germ cell development (Katsumoto and Kume 2013; Nagasawa et al. 1996; Sapède et al. 2005; Tachibana et al. 1998; Zou et al. 1998). During pancreas development, the CXCL12-CXCR4 signaling pathway is responsible for spatiotemporal repositioning of hemangioblasts. It has the function of stimulating the pancreas. CXCL12-CXCR4 signaling does not directly affect pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1 (PDX1) (pancreatic tissue) expression in the early pancreas. It acts indirectly by directing the migration of hemangioblasts during pancreatic development (Katsumoto and Kume 2013). During the development of the heart, coronary arteries arise from the peripheral truncal nerve plexus. It has a ring-shaped network of capillaries that penetrate the aortic wall. SDF-1 levels were elevated in the aortic duct. Peripheral truncal endothelial cells express CXCR4. Therefore, it plays an important role in the development of nerves (Ivins et al. 2015).

SDF-1 and tissue repair and regeneration

SDF-1 plays a role in tissue repair and regeneration. It aids tissue healing and regeneration by helping to recruit stem and progenitor cells to the area of damage (Fig. 3). Low-level stress increases the release of SDF-1, which in turn causes human mesenchymal stem cells (HMSCs) to express its receptor CXCR4 until the cells completely cover the wound, thus promoting regeneration and repair (Yuan et al. 2013). Tissue repair occurs through a complex series of therapeutic actions involving growth factors/cytokines.

Fig. 3.

Mechanism of tissue repair and regeneration. In response to cell injury, chemokine SDF-1 is released which attracts stem cells, and immune and progenitor cells, to the site of injury to aid tissue repair and regeneration

SDF-1 and CXCR4 interaction is essential for homeostatic regulation of white blood cell trafficking, blood cell production, organ development, cell differentiation, and tissue repair in response to molecules causing inflammation. The mechanism of high mobility group box-1 (HMGB1)–mediated stem cell mobilization is like recruitment of inflammatory cells to wounded tissues for white blood cell trafficking and homing. HMGB1 inhibits SDF-1 degradation by causing molecular interactions that are both functional and physical (Haque et al. 2020). Thus, the CXCR4-SDF-1-HMGB1 pathway causes directional migration of cells and regeneration of affected organs by working in conjugation with one another.

The regulation of muscle repair by CXCR4/SDF-1 is dependent on Matrix metalloproteinases (MMP)-10 activity (Bobadilla et al. 2014). Thus, effective skeletal muscle renewal depends on the modulation of CXCR4/SDF-1 communication, which is governed by MMP-10 activity. SDF-1 binding to the CXCR4 receptor enhances skeletal muscle regeneration. It increases cluster of differentiation (CD)9 expression. Thus, it influences stem cell recruitment to damaged muscles (Brzoska et al. 2015). An increase in the production of key trophic factors such as SDF-1, CXCL12, fibroblast growth factor (FGF), hepatocyte growth factor, insulin-like growth factor (IGF), nerve growth factor (NGF), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in the muscle after VEGF injection is what causes the organ repair mechanism. Induction of muscle-derived trophic factors appears to affect the skeletal and myocardial compartments by activating myeloid progenitor cells and expanding progenitor cells, both of which are important for myocardial regeneration (Zisa et al. 2011). The overall effects of SDF-1 gene in tissue regeneration and repair are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

A summary of the effects of SDF-1/CXCR4 in tissue repair and regeneration according to various authors

| Effect of SDF-1/CXCR4 in tissue repair and regeneration | Reference |

|---|---|

| Recruitment of stem and progenitor cells to damaged area | Yuan et al. 2013 |

| Homeostatic regulation of white blood cell trafficking, organ development, and tissue repair | Haque et al. 2020 |

| Promotion of directional migration of cells and organ regeneration | Haque et al. 2020 |

| Modulation of muscle repair dependent on MMP-10 activity | Bobadilla et al. 2014 |

| Enhancement of skeletal muscle regeneration and stem cell recruitment to damaged muscles with increase CD9 expression | Brzoska et al. 2015 |

| Increase in production of key trophic factors like FGF, HGF, IGF, NGF, and VEGF for tissue repair | Zisa et al. 2011 |

SDF-1 and the immune response

SDF-1 plays a role in immune responses. It attracts immune cells to sites of inflammation or infection. SDF-1 helps regulate the trafficking and positioning of immune cells within tissues. In addition to its role as a T cell chemoattractant, SDF-1 may also have more basic immunoregulatory functions, such as promoting T cell proliferation and cytokine production and preventing activation-induced T cell apoptosis (Dunussi-Joannopoulos et al. 2002). During a urinary tract infection caused by Escherichia coli (E. coli), inflammatory sites contain a range of signaling molecules, including various cytokines and chemokines. Immediately after infection, bladder epithelial cells secrete SDF-1, which initiates immune cell accumulation at the site of infection. It has been demonstrated to have a role in the recruitment of phagocytic cells to the bladder infection site (Isaacson et al. 2017; Schiwon et al. 2014).

SDF-1 and bone remodeling, repair, osteogenesis, and chondrogenesis

The regulatory chemokines SDF-1 (CXCL12) and CXCR4 are crucial for the attraction, localization, maintenance, growth, and differentiation of musculoskeletal system progenitor stem cells (Gilbert et al. 2019). Multipotent stem cells (MSCs) are used to differentiate bone, cartilage, fat, and tendon and muscle. During bone repair or remodeling, SDF-1 is produced by MSCs and osteoblasts in response to injury. It acts as a chemoattractant, recruiting MSCs and other cells to the site of injury. MSCs have CXCR4 receptors on their surface, and when SDF-1 binds to CXCR4, it triggers signaling pathways that promote the migration and differentiation of MSCs into osteoblasts, which are responsible for bone formation as shown in Fig. 4. The expression of CXCL12 and its receptor CXCR4 are two chemical signals that are used by MSCs to attract them to their target area. MSCs are crucial for the formation of scaffolds prior to accessing groups of tissues of the musculoskeletal system, making them particularly significant in this regard.

Fig. 4.

SDF-1 in osteogenesis. SDF-1 is released to differentiate mesenchymal stem cells into bone precursors (osteogenic differentiation) and vascular precursors (angiogenic differentiation) which aid in mature bone formation

Local administration of SDF-1 considerably increases bone marrow stem cell recruitment, promotes greater bone repair, and increases the expression of osteocalcin and Runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) (Liu et al. 2020). Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and SDF-1 promote endogenous cell recruitment and cartilage matrix synthesis (Guo et al. 2023).

In tests on the regulation of chondrocyte proliferation, SDF-1 yielded varying outcomes (Li et al. 2021). Some in vitro studies have shown that impeding SDF-1 expression and upregulation could promote the proliferation of chondrocytes. Through various pathways, inhibition of SDF-1 promoted an increase in cartilage and chondrocyte proliferation and chondrocyte development and maturation. MicroRNA (miR) miR-3 and miR-211–3p directly targeted and inhibited SDF-1 to enhance chondrocyte proliferation, viability, and migration (Dai et al. 2019; Zheng et al. 2017). Through the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) MAPK/p381 and all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) pathways, high concentrations of SDF-1 induce chondrocyte apoptosis and necrosis (Wei et al. 2006; Hu et al. 2017). All these pathways showed a negative correlation between SDF-1 and chondrogenesis.

In vivo studies have demonstrated a positive correlation between cartilage proliferation and SDF-1 expression (Li et al. 2021). Through the nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-kB) and extracellular signal–regulated kinase (Erk)1/2 pathways, SDF-1 promoted the overexpression of cyclin D1. Two key transitions occur during the endochondral ossification process: the entry of chondrocytes into the hypertrophy phase from the proliferative phase and the passage of chondrocytes from the hypertrophic phase to the ossification phase. In contrast to proliferating chondrocytes, hypertrophic chondrocytes have a much greater expression of CXCR4, and SDF-1 is detected in the growth plate. SDF-1 controls chondrocyte hypertrophy to promote bone development (Li et al. 2021).

Synovial membranes close to articular cartilage contain the chemokine SDF-1, which is linked to inflammation (Thomas et al. 2017). Osteoarthritis is an aseptic inflammation of bone. Studies have demonstrated the ability of SDF-1 to control osteogenic differentiation (Yang et al. 2020). SDF-1 was found to be mostly expressed in the bone marrow, while CXCR4 was found in the hypertrophic layer of cartilage. Continuous force on the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) caused from overloaded functional orthopedics of the joint with mandibular advancement appliance causes cartilage to degrade with increased release of the tissue-destructive enzyme MMP13 and decreased expression of collagen II. It also enhanced the microRNA (mRNA) and protein expression of SDF-1 and CXCR4. These findings suggest that enhanced osteoblast-derived SDF-1 expression may improve osteogenic differentiation as well as the ability of SDF-1 to bind CXCR4 and degrade cartilage (Yang et al. 2020).

The use of stem cells in therapy holds promise for the healing of damaged tissue. Under the control of the SDF-1/CXCR4 axis, stem cells have homing properties and can be recruited to damage sites after activation (Wang et al. 2022). Several combinations, such as SDF-1 and polylactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) microspheres loaded with Kartogenin (KGN); immobilized bone morphogenic protein (BMP)-7 with SDF-1 in polylactic acid (PLA) cylinder; gel/HA copolymer combined with hydroxyapatite (HAP), hyaluronic acid (HA), and SDF-1 (Gel/HA-HAP-SDF-1); or platelet-rich fibrin scaffold containing SDF-1 were used for bone and cartilage regeneration to aid in recruiting stem cells to the injected sites (Bahmanpour et al. 2016; Chang et al. 2021; Dong et al. 2021; Lauer et al. 2020). This could promote cartilage regeneration. SDF-1 supplementation has an osteoinductive effect, causing new bone to develop with greater strength. All these studies may open up new possibilities for its use in regenerating bone tissue.

Studies have also shown that SDF-1/CXCR4 and regulated upon activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES)/C–C chemokine receptor type 1 (CCR1), mediate the recruitment of exogenous BMSCs to osteoarthritic lesion sites where the recruited BMSCs differentiate into chondrocytes to repair osteoarthritic-like lesions (Lu et al. 2015a, b). SDF-1 levels increase in patients with disordered occlusion (Kuang et al. 2013, 2019). Chondrocytes might express more pro-osteoclastic factors when mechanically stimulated, which leads to condylar subchondral bone resorption by encouraging osteoclastogenesis (Kuang et al. 2019). The middle and posterior thirds of the condylar cartilage displayed local pathologic alterations in the experimentally induced disordered occlusion group. Moreover, uneven cellular disposition, cell-free regions, and a loss of cartilage surface integrity are degenerative alterations. The expression of SDF-1 increases in the hypertrophic layers of the cartilage and bone marrow regions. SDF-1 was less abundant in the condylar cartilage than in the bone marrow region next to the hypertrophic layer of the normal mandibular condyle.

The SDF-1/CXCR4 axis is activated when aberrant tensile stress occurs because SDF-1 has the ability to upregulate a particular CXCR4 receptor, which improves the binding efficiency of the receptor (Bin et al. 2014). Cartilage tissue is directly damaged by this condition, which also increases the expression of interleukin (IL)-6 and other inflammatory factors. This harm directly promotes chondrocyte hypertrophy, which increases collagen X expression, promoting repair. In contrast, a study by Rapp et al. (2015) showed that systemically injected MSCs attracted and supported bone development only in cases of injury and not under mechanical loading to induce bone formation. Cells close to the injury site significantly express SDF-1 or CXCL-12, but when noninvasive mechanical loading was applied, mesenchymal stem cell recruitment was not detected, suggesting an inactive role of SDF-1. Studies have also shown that mechanical stresses cause periodontal ligament (PDL) tissues to secrete SDF-1. Thus, SDF-1 may play a significant role in the maintenance of alveolar bone metabolism by binding to its receptor CXCR4 in mesenchymal stem cells in the bone marrow and stimulating osteoblast development, thus promoting bone and PDL regeneration (Goto et al. 2021; Xu et al. 2019).

Thus, SDF-1 is strongly expressed in cartilage and bone. It acts as an inflammatory chemokine during joint inflammation, recruiting inflammatory mediators to act and cause bone and cartilage degradation (Bragg et al. 2019; Kanbe et al. 2002, 2004; Wang et al. 2015, 2018, 2020). Owing to its chemotactic properties, it also recruits mesenchymal cartilage and bone stem cells to enhance bone development and promote chondrogenic and osteogenic differentiation (He et al. 2018; Huang et al. 2022; Lu et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2017a, b; Zhang et al. 2014; Zhang et al. 2023). However, the role of SDF-1 is more involved in bone formation than in cartilage formation. The overall effects of SDF-1 gene on the musculoskeletal system are summarized in Table 3. Thus, the SDF-1-CXCR4 axis promotes osteogenesis and the rapid formation of bone from cartilage.

Table 3.

A summary of the effects of SDF-1/CXCR4 in skeletal system according to various authors

| Effect of SDF-1/CXCR4 in skeletal system | Reference |

|---|---|

| Increased bone marrow stem cell recruitment, greater bone repair, increased expression of osteocalcin, and RUNX2 | Liu et al. 2020 |

| Promotion of endogenous cell recruitment and cartilage matrix synthesis | Guo et al. 2023 |

| Regulation of chondrocyte proliferation with varying outcomes | Li et al. 2021 |

| Inhibition of SDF-1 expression promoting chondrocyte proliferation and maturation | Dai et al. 2019; Zheng et al. 2017 |

| Induction of chondrocyte apoptosis and necrosis at high concentrations | Wei et al. 2006; Hu et al. 2017 |

| Promotion of cartilage proliferation and bone development | Li et al. 2021 |

| Control of chondrocyte hypertrophy to promote bone development | Li et al. 2021 |

| Link to inflammation in synovial membranes | Thomas et al. 2017 |

| Control of osteogenic differentiation and osteoarthritis | Yang et al. 2020 |

| Recruitment of exogenous BMSCs to osteoarthritic lesion sites for repair | Lu et al. 2015a, b |

| Role in disordered occlusion and chondrocyte hypertrophy | Kuang et al. 2013; Kuang et al. 2019 |

| Upregulation in response to aberrant tensile stress | Bin et al. 2014 |

| Role in alveolar bone metabolism and PDL regeneration | Goto et al. 2021; Xu et al. 2019 |

| Inflammatory chemokine role during joint inflammation | Bragg et al. 2019; Kanbe et al. 2002; Kanbe et al. 2004; Wang et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2020 |

SDF-1 and cancer metastasis

SDF-1 is implicated in cancer metastasis, the progression of secondary malignant growth away from the primary cancer site. It attracts cancer cells expressing the CXCR4 receptor, which is the receptor for SDF-1, to tissues expressing high levels of SDF-1. This interaction promotes the migration and invasion of cancer cells, contributing to metastasis. A crucial transcription factor called nanog homeobox protein (h-NANOG) which contains a homeodomain is needed to maintain pluripotency in embryonic stem cells. By controlling CXCR4 expression to mediate glioblastoma, Sánchez-Sánchez et al. (2021) demonstrated that h-NANOG was a mediator of cellular migration via the SDF-1/CXCR4 pathway. Many different forms of human malignancies, including those of the lung, mouth, prostate, stomach, breast, and brain, have been shown to have elevated NANOG expression. While the SDF-1-CXCR7 axis is involved in angiogenesis and tumor formation, the SDF-1-CXCR4 axis stimulates the homing process by controlling cellular secretion and cell adhesion molecules (Burns et al. 2006). CXCR4 antagonists (AMD3100, T140, and TN14003) have been shown to effectively block the SDF-1/CXCR4 axis. They block this axis by competing with CXCR4 for its ligand SDF-1. They are being utilized to treat HIV infection in addition to numerous malignancies (Burger et al. 2011; Tamamura et al. 2001; Green et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2017a, b).

SDF-1 and musculoskeletal diseases

The most common musculoskeletal conditions in the world are osteoporosis and sarcopenia. These conditions are the primary cause of disability globally. Increased blood levels of inflammatory cytokines are linked to aging, and these levels can have a variety of pleiotropic impacts on cellular processes, including a reduction in MSC viability for differentiation and regeneration. In particular, SDF-1 plays a critical role in bone and muscle BMSC recruitment, survival, and engraftment. However, with aging, the levels of SDF-1 were elevated in plasma and not bone marrow. Increased plasma levels may accelerate bone deterioration and lower bone marrow density, raising the risk of osteoporosis because SDF-1 is also associated with osteoclast recruitment. Thus, the impact of aging-related inflammation on SDF-1 levels may be involved in the pathological alterations associated osteoporosis. Chronic diseases including osteoporosis and higher mortality have been linked to the “senescence-associated secretory phenotype” (SASP). Consequently, a rise in SASP cells may result in a drop in SDF-1 levels in the bone marrow (Gilbert et al. 2019). Similarly in osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis, serum levels of SDF-1 increase causing an increase in concentration of inflammatory mediators like MMP-1, 3, 9, and 13 (Gilbert et al. 2019).

Sarcopenia is a progressive, age-related decrease of muscle mass that is widespread and linked to compromised muscle function. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT-3) signaling pathway that mediates cytokines and growth factors promotes the myogenic lineage of cells by faster differentiation of satellite cells. By promoting satellite cell self-renewal, SDF-1 may prevent constitutive activation of STAT-3 and slow the onset of sarcopenia (Gilbert et al. 2019).

Therapeutic application and future perspective

In order to offer more effective treatment options, therapeutic techniques utilizing SDF-1 have emerged. These strategies involve the regulation of signaling pathways to enable the use of biomaterials and multipotent stem/progenitor cells. Bone marrow CD34 + stem cells are activated by SDF-1. The SDF-1-CXCR4 axis uses a chemotactic gradient to guide stem cells to specific targets or damaged areas (Lau and Wang 2011). Stem cell regeneration therapy has a lot of potential when it comes to bone marrow MSC transplantation into tissue. The donor cell’s inability to live long enough to integrate into tissue is a significant obstacle. It is believed that factors like hypoxia, free radical oxidation, and inadequate nutrition leading to cellular death are to blame for the poor survival of transplanted cells. It is interesting to note that MSCs exposed to high SDF-1 levels show enhanced cellular growth potential, apoptosis prevention, and transplanted MSC survival (Herberg et al. 2013). Degradation of the mitochondrial membrane and subsequent release of cytochrome c, two powerful inducers of apoptosis, were greatly reduced after SDF-1 was administered (Yin et al. 2011). Owing to its angiogenic properties, it can also indirectly influence the vascularity of the MSCs. These results point to the potential application of SDF-1 to improve current stem cell therapy, and concrete developments include the creation of genetically modified MSC with conditional expression of SDF-1. Scaffolds containing SDF-1 were engineered to provide a regulated release of this chemokine, which would draw in circulating or transplanted CD34 + stem cells and promote in situ tissue regeneration (Lau and Wang 2011). SDF-1 can be delivered as direct injections, in the form of scaffolds with microdelivery system; gelatin hydrogels; polylactide ethylene oxide fumarate (PLEOG) hydrogels, in the form of gene modification using adenoviral, retroviral, or lentiviral vector; and polyethylene glycolated fibrin patches (Lau and Wang 2011). Regenerative medicine utilizing SDF-1 has already started to be explored. It is therefore possible that in the near future, its application in a clinical context may become widely accepted.

Conclusion

In summary, it is indisputable that stromal cell–derived factor 1 (SDF-1) plays a critical role in the metabolism of bone and cartilage. SDF-1 has become an important regulator in preserving musculoskeletal homeostasis, controlling everything from the migration of mesenchymal stem cells to the regulation of osteogenesis, chondrogenesis, and angiogenesis as well as the modulation of the inflammatory response. Its complex roles highlight its importance in pathological disorders like osteoporosis and osteoarthritis as well as physiological processes like development and tissue regeneration. Aiming for the restoration of musculoskeletal health and the prevention of related illnesses, targeting this chemokine pathway offers promise as research into the complex processes underlying SDF-1’s activities continues. This chemokine has influenced a wide range of tailored regenerative medicine procedures. SDF-1 incorporated scaffolds and gene modifications using viral vectors have been designed to gain a controlled release of SDF-1 to attract and stabilize MSCs during tissue regeneration. Understanding the complexity of SDF-1’s influence opens new avenues for clinical interventions, fostering a deeper understanding of musculoskeletal biology and paving the way for enhanced patient care and treatment outcomes.

Author contribution

A.P. contributed to the study conception and design and critically revised the work. Data collection and drafting of the manuscript was performed by S.B. V.S. revised the manuscript text. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Disclosure

Data for the preparation of this manuscript utilizes thorough research and reading of articles and is a compilation of well-integrated citations. However, we intend to disclose that ChatGPT and QuillBot paraphrasing tool were utilized to generate synonyms and lightly edit the writing of the manuscript without altering the information that has been provided in this review. Also, all diagrams are drawn using Microsoft PowerPoint.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Azab AK, Azab F, Blotta S, Pitsillides CM, Thompson B, Runnels JM, Roccaro AM, Ngo HT, Melhem MR, Sacco A, Jia X, Anderson KC, Lin CP, Rollins BJ, Ghobrial IM (2009) RhoA and Rac1 GTPases play major and differential roles in stromal cell-derived factor-1-induced cell adhesion and chemotaxis in multiple myeloma. Blood 114:619–629. 10.1182/blood-2009-01-199281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggiolini M, Dewald B, Moser B (1997) Human chemokines: an update. Annu Rev Immunol 15:675–705. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahmanpour S, Ghasemi M, Sadeghi-Naini M, Kashani IR (2016) Effects of platelet-rich plasma and platelet-rich fibrin with and without stromal cell-derived factor-1 on repairing full-thickness cartilage defects in knees of rabbits. Iran J Med Sci 41:507–517. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5106566/. Accessed 24 Sept 2024 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bajanca F, Gouignard N, Colle C, Parsons M, Mayor R, Theveneau E (2019) In vivo topology converts competition for cell-matrix adhesion into directional migration. Nat Commun 10:1–17. 10.1038/s41467-019-09548-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajetto A, Bonavia R, Barbero S, Florio T, Schettini G (2001) Chemokines and their receptors in the central nervous system. Front Neuroendocrinol 22:147–184. 10.1006/frne.2001.0214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessy T, Candelas A, Souquet B, Saadallah K, Schaeffer A, Vianay B, Cuvelier D, Gobaa S, Nakid-Cordero C, Lion J, Bories JC, Mooney N, Jaffredo T, Larghero J, Blanchoin L, Faivre L, Brunet S, Théry M (2021) Hematopoietic progenitors polarize in contact with bone marrow stromal cells in response to SDF-1. J Cell Biol 220:1–14. 10.1083/jcb.202005085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bin K, Qingyu W, Rong S, Yanyan S, Zhiguo C, Yinzhong D, Juan D (2014) Changes in chemokine receptor 4, interleukin-6, and collagen X expression in the ATDC5 cell line stimulated by cyclic tensile strain and stromal cell-derived factor-1. West China J Stomat 32:592–595. 10.7518/hxkq.2014.06.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobadilla M, Sainz N, Abizanda G, Orbe J, Rodriguez JA, Páramo JA, Prósper F, Pérez-Ruiz A (2014) The CXCR4/SDF-1 axis improves muscle regeneration through MMP-10 activity. Stem Cells Dev 23:1417–1427. 10.1089/scd.2013.0491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouzaffour M, Dufourcq P, Lecaudey V, Haas P, Vriz S (2009) Fgf and Sdf-1 pathways interact during zebrafish fin regeneration. PLoS ONE 4:1–8. 10.1371/journal.pone.0005824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bragg R, Gilbert W, Elmansi AM, Isales CM, Hamrick MW, Hill WD, Fulzele S (2019) Stromal cell-derived factor-1 as a potential therapeutic target for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Ther Adv Chronic Dis 10:1–10. 10.1177/2040622319882531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzoska E, Kowalski K, Markowska-Zagrajek A, Kowalewska M, Archacki R, Plaskota I, Stremińska W, Jańczyk-Ilach K, Ciemerych MA (2015) Sdf-1 (CXCL12) induces CD9 expression in stem cells engaged in muscle regeneration. Stem Cell Res Ther 6:1–15. 10.1186/s13287-015-0041-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger JA, Stewart DJ, Wald O, Peled A (2011) Potential of CXCR4 antagonists for the treatment of metastatic lung cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 11(621):630. 10.1586/era.11.11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns JM, Summers BC, Wang Y, Melikian A, Berahovich R, Miao Z, Penfold ME, Sunshine MJ, Littman DR, Kuo CJ, Wei K, McMaster BE, Wright K, Howard MC, Schall TJ (2006) A novel chemokine receptor for SDF-1 and I-TAC involved in cell survival, cell adhesion, and tumor development. J Exp Med 203:2201–2213. 10.1084/jem.20052144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang YL, Hsieh CY, Yeh CY, Chang CH, Lin FH (2021) Fabrication of stromal cell-derived factor-1 contained in gelatin/hyaluronate copolymer mixed with hydroxyapatite for use in traumatic bone defects. Micromachines 12:1–20. 10.3390/mi12070822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crump MP, Gong JH, Loetscher P, Rajarathnam K, Amara A, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Virelizier JL, Baggiolini M, Sykes BD, Clark-Lewis I (1997) Solution structure and basis for functional activity of stromal cell-derived factor-1; dissociation of CXCR4 activation from binding and inhibition of HIV-1. Embo J 16:6996–7007. 10.1093/emboj/16.23.6996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y, Liu S, Xie X, Ding M, Zhou Q, Zhou X (2019) MicroRNA31 promotes chondrocyte proliferation by targeting CXC motif chemokine ligand 12. Mol Med Rep 19:2231–2237. 10.3892/mmr.2019.9859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dar A, Kollet O, Lapidot T (2006) Mutual, reciprocal Sdf-1/Cxcr4 interactions between hematopoietic and bone marrow stromal cells regulate human stem cell migration and development in Nod/Scid chimeric mice. Exp Hematol 34:967–975. 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dealwis C, Fernandez EJ, Thompson DA, Simon RJ, Siani MA, Lolis E (1998) Crystal structure of chemically synthesized [N33A] stromal cell-derived factor 1alpha, a potent ligand for the HIV-1 “fusin” coreceptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:6941–6946. 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshane J, Chen S, Caballero S, Grochot-Przeczek A, Was H, Li Calzi S, Lach R, Hock TD, Chen B, Hill-Kapturczak N, Siegal GP (2007) Stromal cell–derived factor 1 promotes angiogenesis via a heme oxygenase 1–dependent mechanism. J Exp Med 204:605–618. 10.1084/jem.20061609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y, Liu Y, Chen Y, Sun X, Zhang L, Zhang Z, Wang Y, Qi C, Wang S, Yang Q (2021) Spatiotemporal regulation of endogenous MSCs using a functional injectable hydrogel system for cartilage regeneration. NPG Asia Mater 13:1–17. 10.1038/s41427-021-00339-3 [Google Scholar]

- Döring Y, Pawig L, Weber C, Noels H (2014) The CXCL12/CXCR4 chemokine ligand/receptor axis in cardiovascular disease. Front Physiol 5:88349. 10.3389/fphys.2014.00212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunussi-Joannopoulos K, Zuberek K, Runyon K, Hawley RG, Wong A, Erickson J, Herrmann S, Leonard JP (2002) Efficacious immunomodulatory activity of the chemokine stromal cell–derived factor 1 (SDF-1): local secretion of SDF-1 at the tumor site serves as T-cell chemoattractant and mediates T-cell–dependent antitumor responses. Blood Am J Hematol 100:1551–1558. 10.1182/blood.V100.5.1551.h81702001551_1551_1558 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fröbel J, Landspersky T, Percin G, Schreck C, Rahmig S, Ori A, Nowak D, Essers M, Waskow C, Oostendorp RAJ (2021) The hematopoietic bone marrow niche ecosystem. Front Cell Dev Biol 9:1–19. 10.3389/fcell.2021.705410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert W, Bragg R, Elmansi AM, McGee-Lawrence ME, Isales CM, Hamrick MW, Hill WD, Fulzele S (2019) Stromal cell-derived factor-1 (CXCL12) and its role in bone and muscle biology. Cytokine 123:1–24. 10.1016/j.cyto.2019.154783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto KT, Kajiya H, Tsutsumi T, Maeshiba M, Tsuzuki T, Ohgi K, Kawaguchi M, Ohno J, Okabe K (2021) The stromal cell-derived factor-1 expression protected in periodontal tissues damage during occlusal traumatism. J Hard Tissue Biol 30:63–68. 10.2485/jhtb.30.63 [Google Scholar]

- Green MM, Chao N, Chhabra S, Corbet K, Gasparetto C, Horwitz A, Li Z, Venkata JK, Long G, Mims A, Rizzieri D (2016) Plerixafor (a CXCR4 antagonist) following myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation enhances hematopoietic recovery. J Hematol Oncol 9:1–10. 10.1186/s13045-016-0301-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Xi L, Yu M, Fan Z, Wang W, Ju A, Liang Z, Zhou G, Ren W (2023) Regeneration of articular cartilage defects: therapeutic strategies and perspectives. J Tissue Eng 14:1–27. 10.1177/20417314231164765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haque N, Fareez IM, Fong LF, Mandal C, Abu Kasim NH, Kacharaju KR, Soesilawati P (2020) Role of the CXCR4-SDF-1-HMGB1 pathway in the directional migration of cells and regeneration of affected organs. World J Stem Cells 12:938–951. 10.4252/wjsc.v12.i9.938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Z, Jia M, Yu Y, Yuan C, Wang J (2018) Roles of SDF-1/CXCR4 axis in cartilage endplate stem cells mediated promotion of nucleus pulposus cells proliferation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 506:94–101. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.10.069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herberg S, Shi X, Johnson MH, Hamrick MW, Isales CM, Hill WD (2013) Stromal cell-derived factor-1β mediates cell survival through enhancing autophagy in bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. PLoS ONE 8:e58207. 10.1371/journal.pone.0058207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horuk R (2001) Chemokine receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 12:313–335. 10.1016/S1359-6101(01)00014-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu QX, Li XD, Xie P, Wu CC, Zheng GZ, Lin FX, Xie D, Zhang QH, Liu DZ, Wang YG, Chang B (2017) All-transretinoic acid activates SDF-1/CXCR4/ROCK2 signaling pathway to inhibit chondrogenesis. Am J Transl Res 9:2296–2305. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5446512/. Accessed 24 Sept 2024 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Huang J, Liu Q, Xia J, Chen X, Xiong J, Yang L, Liang Y (2022) Modification of mesenchymal stem cells for cartilage-targeted therapy. J Transl Med 20:1–15. 10.1186/s12967-022-03726-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacson B, Hadad T, Glasner A, Gur C, Granot Z, Bachrach G, Mandelboim O (2017) Stromal cell-derived factor 1 mediates immune cell attraction upon urinary tract infection. Cell Rep 20:40–47. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.06.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito H (2011) Chemokines in mesenchymal stem cell therapy for bone repair: a novel concept of recruiting mesenchymal stem cells and the possible cell sources. Mod Rheumatol 21:113–121. 10.3109/s10165-010-0357-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivins S, Chappell J, Vernay B, Suntharalingham J, Martineau A, Mohun TJ, Scambler PJ (2015) The CXCL12/CXCR4 axis plays a critical role in coronary artery development. Dev Cell 33:455–468. 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.03.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jazin EE, Soderstrom S, Ebendal T, Larhammar D (1997) Embryonic expression of the mRNA for the rat homologue of the fusin/CXCR4 HIV-1 co-receptor. J Neuroimmunol 79:148–154. 10.1016/S0165-5728(97)00117-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juarez J, Bendall L, Bradstock K (2004) Chemokines and their receptors as therapeutic targets: the role of the SDF-1/CXCR4 axis. Curr Pharm Des 10:1245–1259. 10.2174/1381612043452640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanbe K, Takemura T, Takeuchi K, Chen Q, Takagishi K, Inoue K (2004) Synovectomy reduces stromal-cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1) which is involved in the destruction of cartilage in osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 86:296–300. 10.1302/0301-620X.86B2.14474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanbe K, Chen Q, Takagishi K (2002) Stromal cell-derived factor-1 induces cartilage destruction in osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis via cxc chemokine receptor 4 through stimulation of matrix metalloproteinase 3 release. Trans Orthop Res Soc 316. https://www.ors.org/transactions/48/0316.pdf. Accessed 24 Sept 2024

- Katsumoto K, Kume S (2013) The role of CXCL12-CXCR4 signaling pathway in pancreatic development. Theranostics 3:11–17. 10.7150/thno.4806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CH, Broxmeyer HE (1999) Chemokines: signal lamps for trafficking of T and B cells for development and effector function. J Leukoc Biol 65:6–15. 10.1002/jlb.65.1.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokovay E, Goderie S, Wang Y, Lotz S, Lin G, Sun Y, Roysam B, Shen Q, Temple S (2010) Adult SVZ lineage cells home to and leave the vascular niche via differential responses to SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling. Cell Stem Cell 7:163–173. 10.1016/j.stem.2010.05.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang B, Dai J, Wang QY, Song R, Jiao K, Zhang J, Tian XG, Duan YZ, Wang MQ (2013) Combined degenerative and regenerative remodeling responses of the mandibular condyle to experimentally induced disordered occlusion. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop 143:69–76. 10.1016/j.ajodo.2012.08.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang B, Zeng Z, Qin Q (2019) Biomechanically stimulated chondrocytes promote osteoclastic bone resorption in the mandibular condyle. Arch Oral Biol 98:248–257. 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2018.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau TT, Wang DA (2011) Stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1): homing factor for engineered regenerative medicine. Expert Opin Biol Ther 11:189–197. 10.1517/14712598.2011.546338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauer A, Wolf P, Mehler D, Götz H, Rüzgar M, Baranowski A, Henrich D, Rommens PM, Ritz U (2020) Biofabrication of SDF-1 functionalized 3D-printed cell-free scaffolds for bone tissue regeneration. Int J Mol Sci 21:1–17. 10.3390/ijms21062175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Chen H, Zhang D, Xie J, Zhou X (2021) The role of stromal cell-derived factor 1 on cartilage development and disease. Osteoarthr Cartil 29:313–322. 10.1016/j.joca.2020.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Wen Y, Qiu J, Zhang Z, Jin Z, Cao M, Jiao Y, Yang H (2020) Local SDF-1α application enhances the therapeutic efficacy of BMSCs transplantation in osteoporotic bone healing. Heliyon 6:1–8. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Zhang X, Zhang M, Shen B, Zhang H, Liao L, Yang T, Zhang J, Jing L, Xian L, Chen D (2015) Enhanced SDF-1 and RANTES attract the locally injected bone marrow stromal cells to remedy dental biomechanically induced temporomandibular joint osteoarthritic lesions. Osteoarthr Cartil 23:295. 10.1016/j.joca.2015.02.535 [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Zhang X, Zhang M, Zhang H, Liao L, Yang T, Zhang J, Xian L, Chen D, Wang M (2015) RANTES and SDF-1 are keys in cell-based therapy of TMJ osteoarthritis. J Dent Res 94:1601–1609. 10.1177/0022034515604621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, Lin Z, Yang Z, Chen M, Zhang K (2016) Inhibition of RUNX2 expression promotes differentiation of MSCs correlated with SDF-1 up-regulation in rats. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 9:11388–11395. https://e-century.us/files/ijcep/9/11/ijcep0035145.pdf. Accessed 24 Sept 2024

- Nagasawa T, Kikutani H, Kishimoto T (1994) Molecular cloning and structure of a pre-B-cell growth-stimulating factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91:2305–2309. 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagasawa T, Hirota S, Tachibana K, Takakura N, Nishikawa SI, Kitamura Y, Yoshida N, Kikutani H, Kishimoto T (1996) Defects of B-cell lymphopoiesis and bone-marrow myelopoiesis in mice lacking the CXC chemokine PBSF/SDF-1. Nature 382:635–638. 10.1038/382635a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmo-Cabañas M, Bartolome RA, Wright N, Hidalgo A, Drager AM, Teixido J (2004) Integrin alpha4beta1 involvement in stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha-promoted myeloma cell transendothelial migration and adhesion: role of cAMP and the actin cytoskeleton in adhesion. Exp Cell Res 294:571–580. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2003.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petit I, Jin D, Rafii S (2007) The SDF-1-CXCR4 signaling pathway: a molecular hub modulating neo-angiogenesis. Trends Immunol 28:299–307. 10.1016/j.it.2007.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp AE, Bindl R, Heilmann A, Erbacher A, Müller I, Brenner RE, Ignatius A (2015) Systemic mesenchymal stem cell administration enhances bone formation in fracture repair but not load-induced bone formation. Eur Cell Mater 29:22–34. 10.22203/ecm.v029a02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Sánchez AV, García-España A, Sánchez-Gómez P, Font-de-Mora J, Merino M, Mullor JL (2021) The embryonic key pluripotent factor NANOG mediates glioblastoma cell migration via the SDF-1/CXCR4 pathway. Int J Mol Sci 22:1–15. 10.3390/ijms221910620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapède D, Rossel M, Dambly-Chaudière C, Ghysen A (2005) Role of SDF-1 chemokine in the development of lateral line efferent and facial motor neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:1714–1718. 10.1073/pnas.0406382102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiwon M, Weisheit C, Franken L, Gutweiler S, Dixit A, Meyer-Schwesinger C, Pohl JM, Maurice NJ, Thiebes S, Lorenz K, Quast T (2014) Crosstalk between sentinel and helper macrophages permits neutrophil migration into infected uroepithelium. Cell 156:456–468. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirozu M, Nakano T, Inazawa J, Tashiro K, Tada H, Shinohara T, Honjo T (1995) Structure and chromosomal localization of the human stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) gene. Genomics 28:495–500. 10.1006/geno.1995.1180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyu WC, Lee YJ, Liu DD, Lin SZ, Li H (2006) Homing genes, cell therapy and stroke. Front Biosci 11:899–907. 10.2741/1846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama T, Kohara H, Noda M, Nagasawa T (2006) Maintenance of the hematopoietic stem cell pool by CXCL12-CXCR4 chemokine signaling in bone marrow stromal cell niches. Immunity 25:977–988. 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachibana K, Hirota S, Iizasa H, Yoshida H, Kawabata K, Kataoka Y, Kitamura Y, Matsushima K, Yoshida N, Nishikawa SI, Kishimoto T (1998) The chemokine receptor CXCR4 is essential for vascularization of the gastrointestinal tract. Nature 393:591–594. 10.1038/31261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamamura H, Omagari A, Hiramatsu K, Kanamoto T, Gotoh K, Kanbara K, Yamamoto N, Nakashima H, Otaka A, Fujii N (2001) Synthesis and evaluation of bifunctional anti HIV agents based on specific CXCR4 antagonists AZT conjugation. Bioorg Med Chem 9(2179):2187. 10.1016/S0968-0896(01)00128-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashiro K, Tada H, Heilker R, Shirozu M, Nakano T, Honjo T (1993) Signal sequence trap: a cloning strategy for secreted proteins and type I membrane proteins. Sci 261:600–603. 10.1126/science.8342023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas NP, Wu WJ, Fleming BC, Wei F, Chen Q, Wei L (2017) Synovial inflammation plays a greater role in post-traumatic osteoarthritis compared to idiopathic osteoarthritis in the Hartley guinea pig knee. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 18:1–10. 10.1186/s12891-017-1913-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thon JN (2014) SDF-1 directs megakaryocyte relocation. Blood, Am J Hematol 124:161–163. 10.1182/blood-2014-05-571653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umezu K, Hara K, Hiradate Y, Numabe T, Tanemura K (2020) Stromal cell-derived factor 1 regulates in vitro sperm migration towards the cumulus-oocyte complex in cattle. PLoS ONE 15:1–25. 10.1371/journal.pone.0232536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang LD, Wagers AJ (2011) Dynamic niches in the origination and differentiation of haematopoietic stem cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 12:643–655. 10.1038/nrm3184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Zhao F, LI Y, YU Y, Gao H, Xiao Y, LI L, Yan X, Jia D (2015) The study of targeted blocking SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling pathway in vivo with T140 on SDF-1 and MMPs levels. J Pract Med 24:3133–3136. https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/resource/pt/wpr-481137. Accessed 24 Sept 2024

- Wang K, Li Y, Han R, Cai G, He C, Wang G, Jia D (2017) T140 blocks the SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling pathway and prevents cartilage degeneration in an osteoarthritis disease model. PLoS ONE 12:1–11. 10.1371/journal.pone.0176048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Sun X, Lv J, Zeng L, Wei X, Wei L (2017) Stromal cell-derived factor-1 accelerates cartilage defect repairing by recruiting bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and promoting chondrogenic differentiation. Tissue Eng Part A 23:1160–1168. 10.1089/ten.tea.2017.0046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Ha C, Lin T, Wang D, Wang Y, Gong M (2018) Celastrol attenuates pain and cartilage damage via SDF-1/CXCR4 signalling pathway in osteoarthritis rats. J Pharm Pharmacol 70:81–88. 10.1111/jphp.12835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Li Y, Meng X, Yang X, Xiang Y (2020) The study of targeted blocking SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling pathway with three antagonists on MMPs, type II collagen, and aggrecan levels in articular cartilage of guinea pigs. J Orthop Surg Res 15:1–7. 10.1186/s13018-020-01646-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Han X, Qiu Y, Sun J (2022) Magnetic nano-sized SDF-1 particles show promise for application in stem cell-based repair of damaged tissues. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 10:1–11. 10.3389/fbioe.2022.831256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei L, Sun X, Kanbe K, Wang Z, Sun C, Terek R, Chen Q (2006) Chondrocyte death induced by pathological concentration of chemokine stromal cell-derived factor-1. J Rheumatol 33:1818–1826. https://www.jrheum.org/content/33/9/1818.short. Accessed 24 Sept 2024 [PubMed]

- Xu M, Wei X, Fang J, Xiao L (2019) Combination of SDF-1 and bFGF promotes bone marrow stem cell-mediated periodontal ligament regeneration. Biosci Rep 39:1–12. 10.1042/BSR20190785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Li Y, Liu Y, Zhang Q, Zhang Q, Chen J, Yan X, Yuan X (2020) Role of the SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling pathway in cartilage and subchondral bone in temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis induced by overloaded functional orthopedics in rats. J Orthop Surg Res 15:330–341. 10.1186/s13018-020-01860-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Q, Jin P, Liu X, Wei H, Lin X, Chi C, Liu Y, Sun C, Wei Y (2011) SDF-1α inhibits hypoxia and serum deprivation-induced apoptosis in mesenchymal stem cells through PI3K/Akt and ERK1/2 signaling pathways. Mol Biol Rep 38:9–16. 10.1007/s11033-010-0071-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan L, Sakamoto N, Song G, Sato M (2013) Low-level shear stress induces human mesenchymal stem cell migration through the SDF-1/CXCR4 axis via MAPK signaling pathways. Stem Cell Dev 22:2384–2393. 10.1089/scd.2012.0717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Zhang L, Chen L, Li W, Li F, Chen Q (2014) Stromal cell-derived factor-1 and its receptor CXCR4 are upregulated expression in degenerated intervertebral discs. Int J Med Sci 11:240–245. 10.7150/ijms.7489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Wang P, Zhang X, Zhao W, Ren H, Hu Z (2020) SDF-1/CXCR4 axis facilitates the angiogenesis via activating the PI3K/AKT pathway in degenerated discs. Mol Med Rep 22:4163–4172. 10.3892/mmr.2020.11498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Zhang C, Wang G, An Y (2023) Achieving nasal septal cartilage in situ regeneration: focus on cartilage progenitor cells. Biomol 13:1–22. 10.3390/biom13091302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X, Zhao FC, Pang Y, Li DY, Yao SC, Sun SS, Guo KJ (2017) Downregulation of miR-221-3p contributes to IL-1betainduced cartilage degradation by directly targeting the SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling pathway. J Mol Med (Berl) 95:615–627. 10.1007/s00109-017-1516-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zisa D, Shabbir A, Mastri M, Taylor T, Aleksic I, McDaniel M, Suzuki G, Lee T (2011) Intramuscular VEGF activates an SDF-1-dependent progenitor cell cascade and an SDF-1-independent muscle paracrine cascade for cardiac repair. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 301:2422–2432. 10.1152/ajpheart.00343.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou YR, Kottmann AH, Kuroda M, Taniuchi I, Littman DR (1998) Function of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 in haematopoiesis and in cerebellar development. Nature 393:595–599. 10.1038/31269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.