ABSTRACT

Objective

This single‐arm effectiveness study explored changes in trauma‐related symptoms—including dissociation, depression, anxiety, sexual issues and sleep disturbances—throughout a multimodal, phased trauma intervention, to explore treatment response in real‐world settings with varied populations and complex clinical presentations, as well as varied degrees of clinician experience.

Method

Symptom change was assessed among participants undergoing a triphasic trauma therapy called trauma practice. Data were collected at five time points: pretreatment (n = 41), Phase 1 (n = 37), Phase 2 (n = 25), Phase 3 (n = 20) and follow‐up (n = 16). Participants completed self‐report measures at the start of therapy, after each therapy phase and 6 months post treatment. The average age of participants was 37.6 years (SD = 12.5). Approximately 63.8% identified as female, 55% were born in Canada and 47.5% identified as Caucasian.

Results

The findings revealed statistically and clinically significant reductions in symptoms across all measured domains. On average, participants transitioned from clinically elevated levels of dissociation, anxiety, depression, sexual difficulties and sleep disturbances at baseline to non‐clinical levels by the end of therapy. Moderate to large effect sizes, clinically significant reliable change indices and sustained treatment gains were demonstrated at follow‐up.

Conclusion

These results suggest that trauma practice holds promise as an effective intervention for trauma in community clinical settings.

Keywords: anxiety, depression, dissociation, sexual problems, sleep, trauma, trauma practice, TSC‐40

Traumatic experiences—including physical, sexual and emotional abuse, acute or prolonged exposure to domestic violence, neglect and various forms of victimization—remain a significant public health issue (Basu et al. 2017; Downey et al. 2017). The 2012 Canadian Community Health Survey: Mental Health (Statistics Canada 2013) noted that one in three Canadians report previously experiencing child abuse, with 26.1% having experienced direct or indirect physical abuse, 10.1% sexual abuse and 7.9% intimate partner violence (Afifi et al. 2014). Additionally, a national survey in the United States found that approximately 80% of people reported experiencing at least one traumatic event in their lifetime (Rizeq et al. 2020; Finkelhor et al. 2013).

The experience of repeated traumatic events has been linked to challenges in various areas of functioning, including interpersonal relationships, emotion regulation, attention and memory, as well as disturbances in self‐concept/perception (Cook et al. 2005; van der Kolk et al. 2005). The cumulative effects of continued exposure to traumatic experiences have been associated with both greater symptom complexity and severity, resulting in individuals potentially experiencing varying levels of different symptoms simultaneously (Briere et al. 2008; Cloitre et al. 2009; Rizeq et al. 2020). Comorbid presentations following traumatic experiences often include symptoms related to dissociation (Boyer et al. 2022; Lebois et al. 2022; Fung et al. 2023), depression (Hankerson et al. 2022; Zheng et al. 2022; Humphreys et al. 2020), anxiety (Fernandes and Osório 2015; Kalin 2021; Peeters et al. 2022), relationship difficulties (Godbout et al. 2020; Pulverman and Meston 2020; O'Driscoll and Flanagan 2016) and sleep/somatic disturbances (Socci et al. 2020; Werner et al. 2024; Alter et al. 2021).

A significant body of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) has demonstrated the effectiveness of trauma‐focused treatments for post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (e.g., Foa et al. 2005; Rothbaum et al. 2005; Blanchard et al. 2003; Sloan et al. 2012; Stenmark et al. 2013). These studies have reported substantial effect sizes in reducing PTSD symptoms across various therapeutic modalities. In addition to robust evidence‐supported, manualized, trauma‐focused therapies such as prolonged exposure (PE), eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) and cognitive processing therapy (CPT), other approaches, including cognitive‐behavioural therapy for PTSD (CBT for PTSD), narrative exposure therapy (NET) and written exposure therapy, have also shown promising results in alleviating PTSD symptoms (Schrader and Ross 2021). Relative to RCT studies, there is still limited evidence on the effectiveness of such treatment programmes in routine clinical settings (Ehlers et al. 2013), with several factors potentially restricting the extent to which treatment effects observed in RCTs translate to practice in day‐to‐day community mental health settings.

Although most RCTs include clinically relevant samples with mild to moderate PTSD and commonly seen comorbid conditions (in most cases only anxiety or depression), their generalizability to a wider range of clinical settings or work with different populations is limited due to specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. These often include a focus on specific acute traumas (e.g., motor vehicle accidents, Blanchard et al. 2003; Sloan et al. 2012), specific populations (e.g., asylum seekers and refugees, Stenmark et al. 2013; military service members, Sloan et al. 2020), specific genders (e.g., female rape survivors, Rothbaum et al. 2005; Resick et al. 2012) or the necessary presence of a PTSD diagnosis. Moreover, in the vast majority of these studies, treatment is typically provided by therapists who undergo extensive and specialized training tailored to the specific modality under investigation, which is provided within a highly structured, controlled environment and prescriptive delivery of the intervention. Clinicians with less training and resources in a community setting, as well as clients with less time, willingness or general capability to follow a highly structured intervention protocol, may struggle to achieve comparable results (Ehlers et al. 2013).

Studies that do examine the effectiveness of treating trauma in more naturalistic settings often focus on discrete unimodal treatments such as TF‐CBT (Webb et al. 2014) or EMDR (Ironson et al. 2002) and report trauma symptoms as an overall PTSD symptomatology (usually accompanied by a diagnosis), instead of considering the specific effects of the intervention on domains of trauma‐related symptomatology. This, in turn, leaves less understanding of the applicability of interventions on more nuanced and complex presentations of trauma which are commonly seen in clinical practice.

Further research is required to evaluate how well multimodal approaches apply to real‐world settings with varied populations and clinical presentations, as well as varied degrees of clinician experience. There is a pressing need for treatments tailored to individual clients that combine evidence‐based modalities with greater flexibility to address the diverse and complex nature of trauma and its treatment in community‐based care settings (Harmsen et al. forthcoming).

This study aims to bridge that gap by examining the effectiveness of trauma practice (TP), a flexible and multimodal trauma intervention, in treating various trauma‐related symptoms within a real‐world community sample, delivered by practitioners as they would see clients in their day‐to‐day practice.

Summary.

Trauma practice (a multimodal, phasic trauma intervention) was shown to be effective in addressing several key trauma‐related symptoms commonly encountered in clinical work with trauma populations (dissociation, anxiety, depression, sexual problems and sleep disturbances).

Trauma practice can be effectively learned and implemented by clinicians with varying levels of training and theoretical backgrounds.

Trauma practice showed high levels of ecological validity and ease of implementation in community‐based mental health practice.

Treatment gains were demonstrated for patients with diverse clinical presentations, comorbidities and backgrounds.

1. What is TP?

TP (Baranowsky and Gentry 2015; Harmsen et al. forthcoming; Norton et al. 2024) is a manualized, integrative and phasic therapeutic approach to trauma work with adults (Herman 1997). The TP intervention package guides the implementation of numerous strategies which target key areas of mental health and well‐being affected by exposure to trauma (cognition, body, behaviour and emotion/relation). Guides for work in each area are accompanied by specific worksheet‐supplemented techniques and organized by phase of intervention (Norton et al. 2024). Unlike traditional, unimodal therapies, that employ a more rigid and standardized, step‐by‐step approach to treatment, TP is not organized in terms of predetermined sequences, number of sessions or specific session content. Rather, TP integrates a range of innovative and clinically established evidence‐based therapeutic techniques from multiple modalities, including CBT, behavioural therapy (BT), emotion‐focused therapies, narrative therapy approaches and somatic interventions (Baranowsky and Gentry 2015; Harmsen et al. forthcoming). The approach is designed as a clinical toolbox from which practitioners can tailor techniques and intervention modalities based on their client's specific and real‐time needs, with each intervention accompanied by indications and counterindications to inform decisions on when to utilize them. This allows the clinician to balance model flexibility with clinical judgement and guidance through a continued collaboration with the client to assess and support the individual client's preparedness and readiness to work through the therapy phases (Norton et al. 2024). TP is organized into three distinct phases:

Phase 1, safety and stabilization, focuses on five key objectives aimed at developing the client's safety and stabilization skills. The first goal is to address any immediate environmental and physical threats, ensuring that clients are no longer in real, active danger. The second goal helps clients differentiate between ‘am safe’ and ‘feel safe’, recognizing the contrast between environmental and internal threats. The third goal involves the therapist teaching the client self‐soothing and self‐rescue techniques, enabling them to support themselves when triggered. The fourth goal is to practice self‐rescue during flashbacks when recounting a trauma narrative. The final step provides the client with a positive prognosis and an agreement to proceed with processing the trauma in question, designed to strengthen the therapeutic alliance and foster hope.

Phase 2, working through trauma, integrates relaxation, exposure and cognitive processing techniques. These methods aim to transform the anxious response to a traumatic event into a more relaxed one. The relaxation skills developed in Phase 1 are crucial here, as they enable clients to explore traumatic memories without eliciting a strong negative emotional response that could hinder processing.

Phase 3, reconnection, involves practical, behavioural steps for clients to start re‐engaging with their community and daily life. Therapy concludes when the client demonstrates a dependable ability to ensure their own safety, has alleviated much of the distress related to their trauma and feels reconnected with their loved ones and community (Norton et al. 2024).

2. The Current Study

TP has gained significant popularity since the early 2000s and is widely utilized by practitioners across various settings, with more than 150,000 clinicians having received TP training through virtual sessions and workshops. It has been implemented worldwide, primarily in Canada, the United States, Australia and the United Kingdom, and is currently in its fourth edition of the manual (Harmsen et al. forthcoming; Norton et al. 2024).

While TP has been widely used in clinical and community settings in the past decade, there is little empirical evidence to date to support its effectiveness. A recent TP study by Norton et al. (2024) demonstrated compelling results regarding the effects of TP on depression symptoms over time, showing a significant reduction in symptomatology both during and post therapy on a partial data set. In addition, our team previously examined changes in general post‐traumatic symptom scores over time within this sample. We observed significant and clinically meaningful reductions in post‐traumatic symptoms and distress from baseline to the end of therapy, with improvements being sustained at 6‐month follow‐up (Wyers 2021). Analysis of the phase‐based approach revealed that the most substantial reduction in post‐traumatic symptoms occurred after Phases 1 and 2, while symptom reduction levelled off during Phase 3, the reconnection phase (Wyers 2021; Norton et al. 2024; Harmsen et al. forthcoming).

The current study expands on previous findings by examining treatment response for TP on several symptom areas known to be problematic in trauma work (dissociation, anxiety, sleep disturbances, sexual problems and sexual trauma). We also re‐examined Norton et al.'s (2024) findings on the effectiveness of TP in the reduction of depression symptoms, now with the full completed dataset. We predicted symptom reduction, for all symptom areas, over the course of treatment, with the maintenance of treatment gains at follow‐up. Treatment response in a community sample was examined using measures of statistical and clinical significance, along with reliable change indices. We looked at the clinical usefulness of the treatment from the perspective of a broad array of symptoms and presentations that are commonly seen in day‐to‐day clinical practice.

Further, research on treatment outcomes differentiates between treatment efficacy and treatment effectiveness. Studies focusing on treatment efficacy emphasize methodological design to maximize internal validity, ensuring that participants have the specific condition the therapeutic model targets and that therapists are skilled in delivering the intervention being examined (Hunsley 2007; Konanur et al. 2015), often with an underrepresentation of minority population groups and exclusion of patients with comorbidities and psychosocial stressors (Cook et al. 2017). Research of this type, while aimed at ensuring high quality implementation of a specific intervention, introduces concerns related to ecological validity (the extent to which the findings can be generalized to real‐world settings; Staines and Cleland 2007) rendering the efficacy research on certain therapeutic modalities less applicable in clinical practice. In addition to this, RCTs often use highly skilled or specialized therapists that may deliver an intervention with a level of proficiency that is unlikely to be replicated in community practice, failing to account for the variability in therapist skill and training more commonly present in real‐world settings, which may leave the effectiveness of the therapy inflated (Staines and Cleland 2007). Finally, a large number of evidence‐based interventions focus on cognitive‐behavioural models based on their effectiveness on groups of subjects, with limited attention to the impact of individual factors that impact patients' health (Cook et al. 2017), whereas a wide range of practitioners often use interpersonal, systemic, psychodynamic, humanistic and/or integrative models and focus on individual patients' specific needs (Emmelkamp et al. 2014). These combined factors make drawing definitive conclusions about meaningful impacts various interventions may have on clinical practice challenging.

In contrast, community‐based settings often involve more diverse populations and have fewer resources for implementing interventions compared to programmes conducted in efficacy trials (Marchand et al. 2011; Konanur et al. 2015). Our study aims to enhance the external and ecological validity of the TP model by assessing its effectiveness within a demographically diverse population, implemented by therapists with varying theoretical backgrounds and clinical experience, with a particular emphasis on the practical and clinical usefulness of this trauma intervention in community practice. TP emphasizes the need for a balanced approach, combining evidence‐based methods with adaptability to real‐world patient contexts.

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author (Robert T. Muller; rmuller@yorku.ca). The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions. The authors of this study have no conflict of interest to disclose.

3. Methods

This study utilized data gathered from a collaborative clinical‐research project conducted by the Trauma and Attachment Lab at York University and Trauma Practice for Healthy Communities, based in Toronto, Canada. Data collection took place from May 2016 to June 2024. Ethical approval was obtained from York University's Human Participants Review Sub‐Committee. There were no conflicts of interest or external funding to disclose.

3.1. Participants

This study included 41 clients seeking therapy for trauma‐related symptoms. The average age of participants was 37.6 years (SD = 12.5). Approximately 63.8% identified as female, 55% were born in Canada and 47.5% identified as Caucasian. Additionally, 30% reported a combined household income exceeding $81,000 CAD, while 27.5% indicated that they lived below Canada's combined low‐income threshold of $42,101 (Wyers 2021; Harmsen et al. forthcoming).

Patients at the participating clinics seeking therapy for trauma‐related symptoms were eligible for the study if they were at least 16 years old, were fluent in English and provided their consent to participate. Participants were required to have stable mental health medications for a minimum of 3 months. An average of five traumatic experiences was reported in the sample, with the most common being physical assault, unwanted sexual encounters and vehicle incidents. Individuals were excluded if they reported active suicidal thoughts or urges, had ongoing substance abuse issues, were diagnosed with a personality or developmental disorder, exhibited signs of active psychosis or had previously undergone trauma therapy. A formal diagnosis of PTSD was not necessary for inclusion, and there was no differentiation between simple and complex trauma for the purposes of this study; however, based on the Trauma Symptom Checklist‐40 (TSC‐40), the average baseline PTSD scores were observed to fall within the clinical range (Whiffen et al. 1997).

This study included 15 clinicians from various Canadian outpatient settings in Ontario, Alberta and Nova Scotia. Clinicians were required to possess at least a master's degree in counselling and have some experience in psychotherapy and trauma therapy. On average, the clinicians in the study had 10 years of therapy experience, with 4 years specifically focused on trauma. Additionally, clinicians were required to complete a 14‐credit hour online training course in TP developed by the founders of TP (Baranowsky and Gentry 2015).

To ensure clinicians were adhering to the TP model during sessions with participants, every clinician was required to attend monthly supervision meetings with the clinical supervisor (and founder of TP) and the Trauma & Attachment lab research team. These meetings, along with the TP online course, assisted clinicians in tailoring suitable treatment techniques to specific client issues and in assessing client readiness to transition between treatment phases. The education levels of the clinicians varied: one registered clinical psychologist (PhD), five doctoral candidates in clinical psychology, eight registered psychotherapists (MA) and one registered social worker (MSW). As this was a naturalistic study, the intervention was not altered in any way for the purposes of research. Our objective was to evaluate how change occurs as clinicians implement the TP model in their daily practices and experiences with clients.

3.2. Procedure

Data collection occurred at five key time points: T0 (preintervention and demographics, during the first or second therapy session), T1 (following Phase 1), T2 (following Phase 2), T3 (following Phase 3) and T4 (6 months post intervention). The research team provided each clinician with questionnaire packages, which were administered to clients at T0, T1, T2 and T3.

Participants filled out questionnaires independently in the waiting room before their therapy sessions. Upon completion, they placed the questionnaires in a prepaid envelope, sealed and signed it to ensure confidentiality, and the envelopes were then sent to the research team.

For T4, follow‐up questionnaires were sent directly to participants by the research team. Participants were invited to complete these follow‐ups at 6 months, but due to challenges and delays in contacting some individuals, the timeframe for T4 varied. Average timeframe for participants was approximately 9 months.

Clinicians did not have access to their clients' research questionnaire responses at any point. Following the triphasic model outlined by Herman (1997), the number of therapy sessions and duration varied among clients across the phases. On average, participants attended nine 50‐min sessions during Phase 1 (approximately 7.5 h/client), 14 sessions in Phase 2 (approximately 11.5 h/client) and 11 sessions in Phase 3 (approximately 9 h/client), totalling an average of 28 therapy hours over a 65‐week period per client. Treatment adhered to the triphasic model, with each phase incorporating interventions focused on body, cognition, behaviour and emotion/relationship (Herman 1997; Norton et al. 2024).

In May 2020, all data collection and storage were transitioned to REDCap software, a HIPAA‐compliant, secure web‐based database, in response to the COVID‐19 pandemic. All therapy sessions moved from in‐person meetings to virtual platforms. During this period, four participants who had completed therapy before March 2020 filled out their follow‐up questionnaires using REDCap, six participants began online data collection while still undergoing therapy (two in Phase 1, three in Phase 2 and one in Phase 3) and eight new participants were recruited. Previous analyses revealed no significant differences in baseline TSC‐40 scores between those who started services during or before the COVID‐19 pandemic (Wyers 2021; Norton et al. 2024; Harmsen et al. forthcoming).

3.3. Participant Attrition

Baseline data (T0) were gathered from all 41 initial participants. At T1, data were collected from 37 participants; two withdrew for personal or financial reasons, and two opted out of the study. At T2, 25 completed questionnaire packages were collected, with eight participants withdrawing due to financial constraints; three ceased therapy, and one left the country. For T3, data included 20 completed questionnaires, as five participants had withdrawn from therapy. At T4, the 6‐month follow‐up stage, we were able to collect 16 completed questionnaire packages, as some participants were harder to reach and/or were nonresponsive after completing therapy. No significant differences were observed between participants who withdrew and those who completed the therapy regarding age, gender, income or education level of their clinicians.

3.4. Measures

3.4.1. TSC‐40

The TSC‐40 (Briere and Runtz 1989; Elliott and Briere 1992) is a concise and user‐friendly self‐report measure that draws items from a broad range of literature on a number of trauma‐related symptoms. These include more direct post‐traumatic stress symptoms (such as nightmares, flashbacks, dissociation and sleep disturbances), as well as mood‐related issues (like depression and anxiety), interpersonal challenges and sexual problems (Elliott and Briere 1992; Rizeq et al. 2020). The questionnaire consists of six defined subscales: (a) dissociation, (b) anxiety, (c) depression, (d) sexual trauma index (SATI), (e) sexual problems and (f) sleep disturbances, through which participants rate the frequency of their symptoms over the past month using a 4‐point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (often), without information regarding specific traumatic events. Higher scores reflect a greater severity of general trauma‐related symptoms.

The TSC‐40 is widely utilized in clinical and research practice to evaluate various trauma‐related symptoms linked to childhood and adulthood experiences of traumatic events in both clinical (Cinamon et al. 2014; Harris et al. 2016; Murphy et al. 2017; Pec et al. 2014) and non‐clinical populations (Clemmons et al. 2007; Fortier et al. 2009; Rosenthal and Freyd 2017; Schaefer and Nooner 2017; Smith and Freyd 2013), underscoring the prevalence of trauma‐related symptoms within the general population (Briere and Elliott 2003).

More recently, Rizek et al. (2020) examined the psychometric properties of the TSC‐40, providing strong empirical support for the reliability and validity of the instrument in its ability to effectively measure complex trauma‐related symptoms such as dissociation, anxiety, depression, sleep disturbances and sexual problems. The overall trauma composite score shows very high reliability (Ω = 0.93), with the anxiety, depression and sexual problems subscales showing higher reliability (Ω = 0.76, 0.77 and 0.78, respectively) than the dissociation, sleep disturbance and SATI subscales (Ω = 0.69, 0.68 and 0.51, respectively). The authors concluded that the TSC‐40 can be utilized to index complex trauma symptomatology in clinical research on varying types of trauma exposure.

3.5. Analyses

Trau subscale scores were evaluated using discrete mixed‐effects models, which were nested by participant to account for a repeated measures design. Preliminary models were fitted from baseline to T4 (follow‐up), followed by separate models for each of the six subscales. Assumptions were tested prior to analyses, and the model met all necessary criteria for normality, linearity and homoscedasticity. To address moderate client attrition, separate mixed‐effects models were employed for each analysis to manage missing data, utilizing the restricted maximum likelihood estimate. Effect sizes were examined and reported as unstandardized, reflecting the average change in measures by phase, in line with Wilkinson's (1999) mixed‐effects model analysis recommendations.

To determine whether the changes in symptoms were greater than what could be attributed to measurement error, we calculated reliable change indices (RCIs; Jacobson and Truax 1992; Zahra and Hedge 2010) using the formula outlined by Zahra and Hedge (2010). RCIs offer a standardized approach to assessing the magnitude of change within a dataset, with values exceeding 1.96 (positively or negatively) regarded as statistically significant at the p < 0.05 level. RCI calculations typically rely on pretreatment standard deviation and normative estimates of a given measure's reliability. We used previously reported test–retest reliability coefficients to compute RCI values for the TSC‐40 (refer to reliability coefficients in the Measures section). Individual RCIs were calculated for each participant and subscale over the course of treatment.

All analyses were conducted as two‐tailed tests, using a nominal Type‐I error rate of 0.05, with a significance threshold of +1.96 to determine statistical significance (Jacobson and Truax 1992).

4. Results

Overall outcome analyses assessing the changes in each subscale from baseline (T0) to final follow‐up (T4) indicated a statistically significant reduction in symptoms for all six subscales at p < 0.01 (dissociation, anxiety, depression, SATI, sleep disturbances and sexual problems) through 6 months following treatment (see Table 1), with most notable differences seen following Phase 1 (safety and stabilization).

TABLE 1.

TSC‐40 subscale changes from baseline to 6‐month follow‐up.

| T0–T4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSC‐40 subscales | B | t | df | p | 95% CI |

| Dissociation | −4.46 | −5.25 | 86 | < 0.001 | −6.15, −2.77 |

| Anxiety | −5.25 | −6.10 | 86 | < 0.001 | −6.96, −3.54 |

| Depression | −7.99 | −7.18 | 88 | < 0.001 | −10.21, −5.78 |

| SATI | −3.89 | −3.98 | 86 | < 0.001 | −5.81, −1.94 |

| Sleep disturbances | −5.75 | −5.72 | 88 | < 0.001 | −7.74, −3.76 |

| Sexual problems | −3.45 | −3.10 | 86 | < 0.01 | −5.64, −1.24 |

Note: The table represents changes in specific TSC‐40 subscale scores from baseline to final follow‐up (6 months post completion of therapy).

On average, participants demonstrated a reduction of 4.46 points for dissociation, 5.25 for anxiety, 7.99 for depression, 3.89 for SATI, 5.75 for sleep disturbances and 3.45 for sexual problems between baseline and final follow‐up. To determine if reductions in symptomology were clinically significant, clinical cut‐offs were calculated using the average TSC‐40 score in Whiffen et al.'s (1997) outpatient clinical sample (see Norton et al. 2024 for more details). These average scores were used as indicators of clinically significant levels of symptomatology for each subscale (7.45 for dissociation, 9.75 for anxiety, 11.75 for depression, 9.4 for SATI, 9.9 for sleep disturbances and 9.45 for sexual problems, respectively). Average scores for all subscales that were above the clinically significant line at baseline, moved under the line by the end of Phase 1 or 2 of therapy, remaining under the line at 6‐month follow‐up (see Figure 1). Results from baseline to immediately post therapy were virtually the same as baseline to 6‐month follow‐up (i.e., treatment gains were maintained; no significant changes were observed during the post‐therapy follow‐up period at p > 0.05).

FIGURE 1.

Average trajectory of change in participant TSC‐40 subscale scores from baseline to follow‐up. Note: (A–F) The x axis indicates data collection time points (0 = preintervention [baseline]; 1 = post Phase 1 of therapy; 2 = post Phase 2 of therapy; 3 = post Phase 3 of therapy; 4 = 6 months following therapy). The y axis indicates TSC‐40 scores for each subscale. The black line represents the average trajectory of change, with the grey area surrounding the line representing the 95% confidence interval. The red line represents the clinically significant cut‐off line for each subscale (with values above the line being in the clinically significant range).

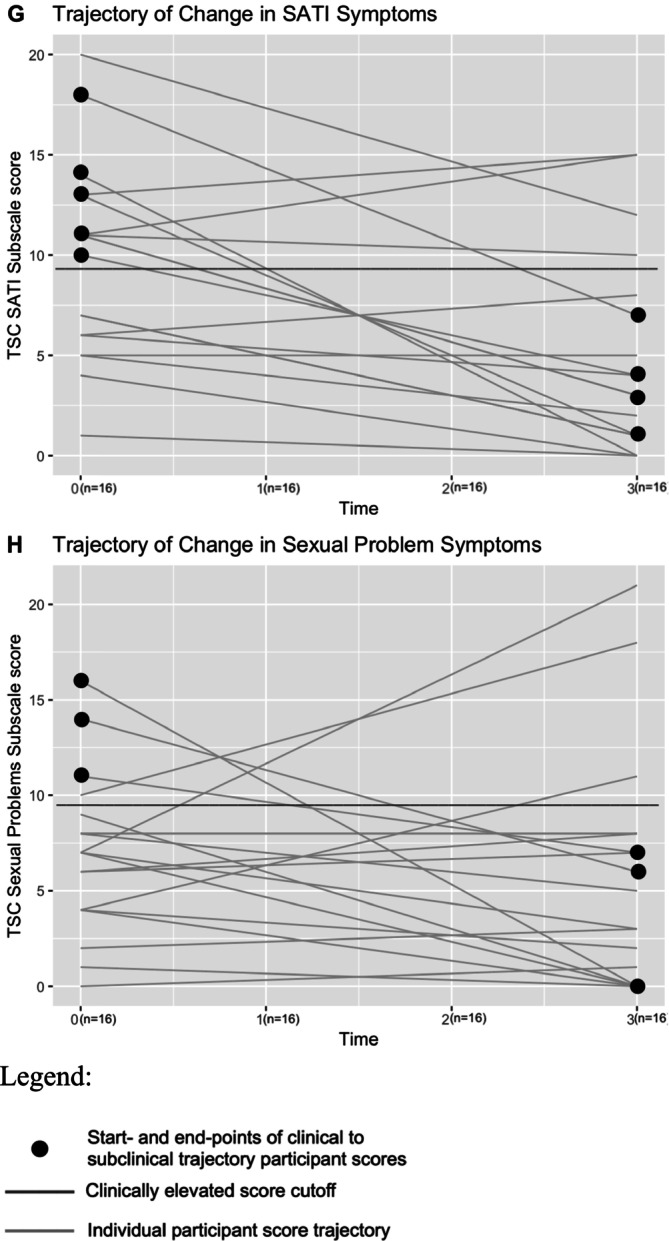

While the SATI and sexual problem subscale average scores were not above the clinically significant threshold at baseline, further analyses still indicated that 5 out of 9 (56%) participants that started above the clinical line ended below it for SATI, and 3 out of 4 (75%) for sexual problems (see Figure 2), demonstrating a clinically significant trajectory for these subscales as well.

FIGURE 2.

Individual participant trajectory of change in SATI and sexual problem subscale scores from baseline to end of therapy. Note: (G,H) The x axis indicates data collection time points (0 = preintervention [baseline]; 1 = post Phase 1 of therapy; 2 = post Phase 2 of therapy; 3 = post Phase 3 of therapy). The y axis indicates TSC‐40 scores for each subscale. The grey lines represent each individual participants' trajectory of change. The red line represents the clinically significant cut‐off line for each subscale (with values above the line being in the clinically significant range). The black dots represent the start point and end‐point of participants who began therapy above the clinical threshold and ended below.

4.1. Reliable Change

Reliable change indices varied across the subscales, with 38.88% of participants demonstrating a reliable decrease (i.e., showing a negative RCI with an absolute value greater than 1.96) in dissociation symptoms, 50% in anxiety symptoms, 55.56% in depression symptoms, 33.34% in SATI, 42.11% in sleep disturbances and 16.67% in sexual problems (see Table 2). Three participants demonstrated a reliable increase in sexual problems at conclusion of therapy. The remainder of participants did not demonstrate a reliable change in either direction over the course of treatment, although an overall trend of reduction in symptoms was observed.

TABLE 2.

Reliable change index from baseline to conclusion of therapy.

| T0–T3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant ID | Dissociation | Anxiety | Depression | SATI | Sleep disturbance | Sexual problems |

| 01 | −1.142 | −0.856 | −0.856 | −0.571 | −0.571 | −0.856 |

| 02 | −1.998 | −0.285 | −2.569 | −0.856 | −1.427 | −0.571 |

| 03 | −1.712 | −2.283 | −1.998 | −1.142 | −1.427 | −1.998 |

| 04 | −0.571 | −0.856 | −1.142 | 0.571 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 05 | −2.569 | −2.854 | −2.283 | −3.139 | −2.854 | −1.142 |

| 06 | −0.285 | −0.856 | −1.142 | −0.285 | −1.142 | −0.285 |

| 07 | −3.139 | −2.283 | −3.425 | −3.996 | −3.710 | −4.566 |

| 08 | −3.425 | −2.569 | −4.281 | −2.283 | −3.996 | 0.285 |

| 09 | −1.712 | −0.856 | −2.283 | −0.285 | −1.712 | 1.998 |

| 10 | −3.425 | −2.354 | −4.281 | −2.283 | −3.710 | 0.571 |

| 11 | −1.712 | −0.285 | −1.142 | 1.142 | −0.571 | 2.283 |

| 12 | −3.996 | −3.996 | −5.993 | −3.425 | −2.854 | −2.569 |

| 13 | −1.712 | −0.571 | −0.856 | −1.712 | −1.998 | 0.285 |

| 14 | −0.571 | −1.998 | −0.571 | −1.712 | −1.712 | −1.142 |

| 15 | −1.427 | −3.710 | −3.139 | −1.712 | −2.283 | −1.142 |

| 16 | −1.427 | 0.285 | −0.285 | N/A | −0.285 | 0.285 |

| 17 | −3.139 | −2.569 | −3.139 | 0.571 | −1.998 | 3.996 |

| 18 | −2.596 | −1.427 | −1.712 | −2.283 | −0.571 | −0.571 |

| 19 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | −0.285 | N/A |

Note: The table represents change indices for each participant, per subscale from baseline to conclusion of therapy. Values highlighted in green represent a statistically reliable decrease in symptoms (with an absolute value greater than 1.96 in the negative direction, p < 0.05). Values highlighted in red represent a statistically reliable increase in symptoms (with an absolute value greater than 1.96 in the positive direction, p < 0.05).

5. Discussion

This study examined the effectiveness of a triphasic trauma therapy, TP, at reducing trauma‐related symptoms in a community‐based sample. A naturalistic method was used to include more diverse clinical presentations in research and to increase generalisability of findings, with TP as the modality of interest.

TP has previously been shown to reduce post‐traumatic scores (Wyers 2021; Harmsen et al. forthcoming) and depression symptoms (Norton et al. 2024) in a portion of this sample. The current study builds on these initial findings, revealing both statistically and clinically significant reductions in trauma symptoms from baseline to therapy termination, with the maintenance of treatment gains over time, along with moderate to large effect sizes and robust reliable change indices.

Notable clinical improvements were observed throughout the course of therapy. On average, participants' symptoms were clinically elevated at baseline for four of the scales (dissociation, anxiety, depression and sleep problems). By the end of therapy, these symptoms were well below the clinical threshold. All average scores fell beneath the clinical threshold after Phase 2 (when taking into consideration 95% confidence intervals), with the most significant changes for all scales occurring after Phase 1, emphasizing the importance of incorporating a stabilization phase before processing trauma (Herman 1997; Muller 2010, 2018; Harmsen et al. forthcoming).

Although average scores for two subscales (SATI and sexual problems) were not above the clinical threshold at baseline, analyses still indicated a significant reduction in symptoms for both, with many participants who started above the clinical threshold finishing below it by the end of therapy. While three participants showed a clinically significant increase in the sexual problem scale, it is important to note that this same minority of participants still showed significant improvements in all other subscales (i.e., decrease in all other symptoms). At this point, it is not clear why this small percentage of participants showed an increase in one particular subscale. One might consider if there are aspects of certain items on the TSC‐40 measure that some people react to differently based on their personal and trauma history. Further qualitative analyses would be required to determine possible reasoning behind this finding, if it goes beyond random error.

Results demonstrated substantial improvement and the maintenance of treatment gains at follow‐up. They speak to the effectiveness of TP in relation to important domains of trauma‐related symptomatology.

Additionally, our findings indicate that TP can address the complexities of trauma presentations seen in community practice, effectively treating patients with a range of symptom presentations, comorbidities and personal characteristics. Moreover, TP was shown to be trainable and administrable by a variety of clinicians with different degrees of training and theoretical backgrounds. This is of particular importance due to previous research on RCTs noting that the utilization of only highly trained experts in research limits the generalizability of findings, potentially biasing an intervention's outcomes (Cook et al. 2017). By focusing only on experienced therapists, such research may not reflect how the intervention may work in real‐world settings, because it fails to account for variability in therapist skill and training present in community clinical practice, creating a concern regarding ecological validity (Staines and Cleland 2007). The current study has demonstrated the utility of TP in treating trauma symptoms when delivered by therapists with a wide range of experience levels that are more applicable to the diverse conditions of everyday clinical practice.

5.1. Limitations and Future Directions

This study has several limitations that should be considered. A primary limitation is the relatively small sample size, particularly in the later stages. A moderately high level of participant attrition observed over the course of the study was primarily contributed to its naturalistic design. The majority of participants that did not complete the study in its entirety were unable to do so due to cessation of therapy, with most common reasons being of a personal or financial nature. Other reasons included a move out of the country or unresponsiveness at follow‐up. This, while limiting the generalisability of findings, was an unavoidable reality of conducting research in private, community‐based clinical practice. Notably, the use of naturalistic methodology with a community‐based outpatient sample was also one of the primary strengths of the study, significantly enhancing external validity by reflecting real‐world treatment conditions. However, this approach also introduces factors, such as variations in session length, treatment phase duration and session frequency. Future research might consider using efficacy models to better control these variables, strengthening the findings and ensuring a consistent treatment model for clients. Although these findings on the effectiveness of TP for various trauma‐related symptoms are encouraging, further research with larger sample sizes in clinical settings is needed to more thoroughly evaluate TP's effectiveness.

Further, it is possible that some variation in participant outcomes was, in part, influenced by comprehensive training and ongoing guidance the clinical team received directly from one of the founders of TP. Considering the depth of training and reinforcement provided, this factor warrants careful consideration when interpreting the study's findings, given that a therapist's proficiency and confidence in a specific therapeutic method can have a meaningful impact on a treatment's effectiveness.

Another possible limitation is the shift to online data collection and therapy due to the COVID‐19 pandemic. While no significant differences in baseline symptoms were found between COVID and non‐COVID data (Harmsen et al. forthcoming), future research may consider the impact of COVID on levels of complex trauma symptoms in community settings.

Also, this study did not distinguish between simple and complex trauma and did not have a control group, which could have increased sample heterogeneity and limited our ability to attribute the effects solely to TP.

Finally, trauma symptoms were measured through subscales of one measure (TSC‐40; Briere and Runtz 1989; Elliott and Briere 1992). While these subscales were found to be reliable in measuring the targeted symptoms (Rizeq et al. 2020), future studies should examine symptoms using more comprehensive, symptom specific measures to solidify the validity of these findings.

6. Conclusion

The findings of this study provide support for the use of phase‐based trauma therapy in addressing a variety of symptoms commonly seen in individuals with a history of trauma. These results suggest that integrated treatment approaches, responsive to client needs, may be a valuable addition to a clinician's toolkit. Because TP combines a range of therapeutic techniques shown to be effective in treating trauma, the study's outcomes lend support to a flexible, client‐centred treatment model that can effectively address the diverse manifestations of trauma symptoms in community mental health settings.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data Availability Statement

The data collected and analyzed in this study are not publicly accessible as they contain sensitive information that could compromise the privacy of the research participants. The data may be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Correspondence regarding this study should be sent to the last author, Robert T. Muller PhD, Professor, Department of Psychology, Faculty of Health, York University, 4700 Keele St., Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M3J 1P3. Email: (rmuller@yorku.ca).

References

- Afifi, T. O. , MacMillan H. L., Boyle M., Taillieu T., Cheung K., and Sareen J.. 2014. “Child Abuse and Mental Disorders in Canada.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 186: E324–E332. 10.1503/cmaj.131792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alter, S. , Wilson C., Sun S., et al. 2021. “The Association of Childhood Trauma With Sleep Disturbances and Risk of Suicide in US Veterans.” Journal of Psychiatric Research 136: 54–62. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranowsky, A. B. , and Gentry J. E.. 2015. Trauma Practice: Tools for Stabilization and Recovery. 3rd ed. Hogrefe Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Basu, A. , McLaughlin K. A., Misra S., and Koenen K. C.. 2017. “Childhood Maltreatment and Health Impact: The Examples of Cardiovascular Disease and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Adults.” Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 24, no. 2: 125. 10.1037/h0101742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard, E. B. , Hickling E. J., Devineni T., et al. 2003. “A Controlled Evaluation of Cognitive Behaviorial Therapy for Posttraumatic Stress in Motor Vehicle Accident Survivors.” Behaviour Research and Therapy 41, no. 1: 79–96. 10.1016/S0005-7967(01)001310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer, S. M. , Caplan J. E., and Edwards L. K.. 2022. “Trauma‐Related Dissociation and the Dissociative Disorders: Neglected Symptoms With Severe Public Health Consequences.” Delaware Journal of Public Health 8, no. 2: 78–84. 10.32481/djph.2022.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere, J. , and Elliott D. M.. 2003. “Prevalence and Psychological Sequelae of Self‐Reported Childhood Physical and Sexual Abuse in a General Population Sample of Men and Women.” Child Abuse & Neglect 27, no. 10: 1205–1222. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere, J. , Kaltman S., and Green B. L.. 2008. “Accumulated Childhood Trauma and Symptom Complexity.” Journal of Traumatic Stress 21: 223–226. 10.1002/jts.20317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere, J. N. , and Runtz M. G.. 1989. “The Trauma Symptom Checklist (TSC‐33): Early Data on a New Scale.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 4: 151–163. 10.1177/088626089004002002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cinamon, J. S. , Muller R. T., and Rosenkranz S. E.. 2014. “Trauma Severity, Poly‐Victimization, and Treatment Response: Adults in an Inpatient Trauma Program.” Journal of Family Violence 29: 725–737. 10.1007/s10896-014-9631-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clemmons, J. C. , Walsh K., DiLillo D., and Messman‐Moore T. L.. 2007. “Unique and Combined Contributions of Multiple Child Abuse Types and Abuse Severity to Adult Trauma Symptomatology.” Child Maltreatment 12, no. 2: 172–181. 10.1177/1077559506298248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre, M. , Stolbach B. C., Herman J. L., et al. 2009. “A Develop‐Mental Approach to Complex PTSD: Childhood and Adult Cumulative Trauma as Predictors of Symptom Complexity.” Journal of Traumatic Stress 22: 399–408. 10.1002/jts.20444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook, A. , Spinazzola J., Ford J., et al. 2005. “Complex Trauma in Children and Adolescents.” Psychiatric Annals 35: 390–398. 10.3928/00485713-20050501-05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cook, S. C. , Schwartz A. C., and Kaslow N. J.. 2017. “Evidence‐Based Psychotherapy: Advantages and Challenges.” Neurotherapeutics 14: 537–545. 10.1007/s13311-017-0549-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey, J. C. , Gudmunson C. G., Pang K. L., and Lee K.. 2017. “Adverse Childhood Experiences Affect Health Risk Behaviors and Chronic Health of Iowans.” Journal of Family Violence 32: 557–564. 10.1007/s10896-017-9909-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers, A. , Grey N., Wild J., et al. 2013. “Implementation of Cognitive Therapy for PTSD in Routine Clinical Care: Effectiveness and Moderators of Outcome in a Consecutive Sample.” Behaviour Research and Therapy 51, no. 11: 742–752. 10.1016/j.brat.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, D. M. , and Briere J.. 1992. “Sexual Abuse Trauma Among Professional Women: Validating the Trauma Symptom Checklist‐40 (TSC‐40).” Child Abuse & Neglect 16, no. 3: 391–398. 10.1016/01452134(92)90048-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmelkamp, P. M. , David D., Beckers T. O. M., et al. 2014. “Advancing Psychotherapy and Evidence‐Based Psychological Interventions.” International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 23, no. S1: 58–91. 10.1002/mpr.1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, V. , and Osório F. L.. 2015. “Are There Associations Between Early Emotional Trauma and Anxiety Disorders? Evidence From a Systematic Literature Review and Meta‐Analysis.” European Psychiatry 30, no. 6: 756–764. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor, D. , Turner H. A., Shattuck A., and Hamby S. L.. 2013. “Violence, Crime, and Abuse Exposure in a National Sample of Children and Youth: An Update.” JAMA Pediatrics 167, no. 7: 614–621. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa, E. B. , Hembree E. A., Cahill S. P., et al. 2005. “Randomized Trial of Prolonged Exposure for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder With and Without Cognitive Restructuring: Outcome at Academic and Community Clinics.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 73, no. 5: 953. 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortier, M. A. , DiLillo D., Messman‐Moore T. L., Peugh J., DeNardi K. A., and Gaffey K. J.. 2009. “Severity of Child Sexual Abuse and Revictimization: The Mediating Role of Coping and Trauma Symptoms.” Psychology of Women Quarterly 33, no. 3: 308–320. 10.1111/j.14716402.2009.01503.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fung, H. W. , Geng F., Yuan D., Zhan N., and Lee V. W. P.. 2023. “Childhood Experiences and Dissociation Among High School Students in China: Theoretical Reexamination and Clinical Implications.” International Journal of Social Psychiatry 69, no. 8: 1949–1957. 10.1177/00207640231181528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godbout, N. , Bakhos G., Dussault É., and Hébert M.. 2020. “Childhood Interpersonal Trauma and Sexual Satisfaction in Patients Seeing Sex Therapy: Examining Mindfulness and Psychological Distress as Mediators.” Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy 46, no. 1: 43–56. 10.1080/0092623X.2019.1626309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankerson, S. H. , Moise N., Wilson D., et al. 2022. “The Intergenerational Impact of Structural Racism and Cumulative Trauma on Depression.” American Journal of Psychiatry 179, no. 6: 434–440. 10.1176/appi.ajp.21101000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmsen, C. R. W. , Salisbury M., Cordeiro K., Rependa S., Baranowsky A., and Muller R. T.. Forthcoming. “Posttraumatic Symptom Improvement in Trauma Practice Tri‐Phasic Therapy: Preliminary Findings From a Multi‐Site Community‐Based Setting.” Psychological Trauma Theory Research Practice and Policy. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, L. S. , Block S. D., Ogle C. M., et al. 2016. “Coping Style and Memory Specificity in Adolescents and Adults With Histories of Child Sexual Abuse.” Memory 24, no. 8: 1078–1090. 10.1080/09658211.2015.1068812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman, J. L. 1997. Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence—From Domestic Abuse to Political Terror (rev ed.). Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys, K. L. , LeMoult J., Wear J. G., Piersiak H. A., Lee A., and Gotlib I. H.. 2020. “Child Maltreatment and Depression: A Meta‐Analysis of Studies Using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire.” Child Abuse & Neglect 102: 104361. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunsley, J. 2007. “Addressing Key Challenges in Evidence‐Based Practice in Psychology.” Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 38, no. 2: 113–121. 10.1037/07357028.38.2.113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ironson, G. , Freund B., Strauss J. L., and Williams J.. 2002. “Comparison of Two Treatments for Traumatic Stress: A Community‐Based Study of EMDR and Prolonged Exposure.” Journal of Clinical Psychology 58, no. 1: 113–128. 10.1002/jclp.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, N. S. , and Truax P.. 1992. “Clinical Significance: A Statistical Approach to Defining Meaningful Change in Psychotherapy Research.” In Methodological Issues & Strategies in Clinical Research, edited by Kazdin A. E., 631–648. American Psychological Association. 10.1037/10109042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalin, N. H. 2021. “Trauma, Resilience, Anxiety Disorders, and PTSD.” American Journal of Psychiatry 178, no. 2: 103–105. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20121738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konanur, S. , Muller R. T., Cinamon J. S., Thornback K., and Zorzella K. P.. 2015. “Effectiveness of Trauma‐Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in a Community‐Based Program.” Child Abuse & Neglect 50: 159–170. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebois, L. A. , Kumar P., Palermo C. A., et al. 2022. “Deconstructing Dissociation: A Triple Network Model of Trauma‐Related Dissociation and Its Subtypes.” Neuropsychopharmacology 47, no. 13: 2261–2270. 10.1038/s41386-022-01468-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchand, E. , Stice E., Rohde P., and Becker C. B.. 2011. “Moving From Efficacy to Effectiveness Trials in Prevention Research.” Behaviour Research and Therapy 49, no. 1: 32–41. 10.1016/j.brat.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller, R. T. 2010. Trauma and the Avoidant Client: Attachment‐Based Strategies for Healing. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Muller, R. T. 2018. Trauma and the Struggle to Open Up: From Avoidance to Recovery and Growth. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, S. , Elklit A., Murphy J., Hyland P., and Shevlin M.. 2017. “A Cross‐Lagged Panel Study of Dissociation and Post‐Traumatic Stress in a Treatment‐Seeking Sample of Survivors of Childhood Sexual Abuse.” Journal of Clinical Psychology 73, no. 10: 1370–1381. 10.1002/jclp.22439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton, L. G. , Harmsen C. R., Corderio K., Baranowsky A., and Muller R. T.. 2024. “Depression Symptom Changes in Triphasic Trauma Therapy: Initial Findings From a Community‐Based Observational Study.” Journal of Psychotherapy Integration 34, no. 4: 484–501. 10.1037/int0000335. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O'Driscoll, C. , and Flanagan E.. 2016. “Sexual Problems and Post‐Traumatic Stress Disorder Following Sexual Trauma: A Meta‐Analytic Review.” Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice 89, no. 3: 351–367. 10.1111/papt.12077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pec, O. , Bob P., and Raboch J.. 2014. “Dissociation in Schizophrenia and Borderline Personality Disorder.” Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment: 487–491. 10.2147/NDT.S57627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters, N. , Van Passel B., and Krans J.. 2022. “The Effectiveness of Schema Therapy for Patients With Anxiety Disorders, OCD, or PTSD: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda.” British Journal of Clinical Psychology 61, no. 3: 579–597. 10.1111/bjc.12324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulverman, C. S. , and Meston C. M.. 2020. “Sexual Dysfunction in Women With a History of Childhood Sexual Abuse: The Role of Sexual Shame.” Psychological Trauma Theory Research Practice and Policy 12, no. 3: 291. 10.1037/tra0000506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick, P. A. , Williams L. F., Suvak M. K., Monson C. M., and Gradus J. L.. 2012. “Long‐Term Outcomes of Cognitive–Behavioral Treatments for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Among Female Rape Survivors.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 80, no. 2: 201–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizeq, J. , Flora D. B., and McCann D.. 2020. “Construct Validation of the Trauma Symptom Checklist‐40 Total and Subscale Scores.” Assessment 27, no. 5: 1016–1028. 10.1177/1073191118791042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, M. N. , and Freyd J. J.. 2017. “Silenced by Betrayal: The Path From Childhood Trauma to Diminished Sexual Communication in Adulthood.” Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 26, no. 1: 3–17. 10.1080/10926771.2016.1175533. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbaum, B. O. , Astin M. C., and Marsteller F.. 2005. “Prolonged Exposure Versus Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) for PTSD Rape Victims.” Journal of Traumatic Stress 18, no. 6: 607–616. 10.1002/jts.20069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer, L. M. , and Nooner K. B.. 2017. “Brain Function Associated With Cooccurring Trauma and Depression Symptoms in College Students.” Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 26, no. 2: 175–190. 10.1080/10926771.2016.1272656. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schrader, C. , and Ross A.. 2021. “A Review of PTSD and Current Treatment Strategies.” Missouri Medicine 118, no. 6: 546. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan, D. M. , Marx B. P., Bovin M. J., Feinstein B. A., and Gallagher M. W.. 2012. “Written Exposure as an Intervention for PTSD: A Randomized Clinical Trial With Motor Vehicle Accident Survivors.” Behaviour Research and Therapy 50, no. 10: 627–635. 10.1016/j.brat.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan, D. M. , Marx B. P., Resick P. A., et al. 2020. “Study Design Comparing Written Exposure Therapy to Cognitive Processing Therapy for PTSD Among Military Service Members: A Noninferiority Trial.” Contemporary Clinical Trials Communications 17, no. 1: 100507. 10.1016/j.conctc.2019.100507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C. P. , and Freyd J. J.. 2013. “Dangerous Safe Havens: Institutional Betrayal Exacerbates Sexual Trauma.” Journal of Traumatic Stress 26, no. 1: 119–124. 10.1002/jts.21778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socci, V. , Rossi R., Talevi D., Crescini C., Tempesta D., and Pacitti F.. 2020. “Sleep, Stress and Trauma.” Journal of Psychopathology 26, no. 1: 92–98. 10.36148/2284-0249-375. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Staines, G. L. , and Cleland C. M.. 2007. “Bias in Meta‐Analytic Estimates of the Absolute Efficacy of Psychotherapy.” Review of General Psychology 11, no. 4: 329–347. 10.1037/10892680.11.4.329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada . 2013. Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS): Mental Health User Guide. Statistics Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Stenmark, H. , Catani C., Neuner F., Elbert T., and Holen A.. 2013. “Treating PTSD in Refugees and Asylum Seekers Within the General Health Care System. A Randomized Controlled Multicenter Study.” Behaviour Research and Therapy 51, no. 10: 641–647. 10.1016/j.brat.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kolk, B. A. , Roth S., Pelcovitz D., Sunday S., and Spinazzola J.. 2005. “Disorders of Extreme Stress: The Empirical Foundation of a Complex Adaptation to Trauma.” Journal of Traumatic Stress 18: 389–399. 10.1002/jts.20047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb, C. , Hayes A. M., Grasso D., Laurenceau J. P., and Deblinger E.. 2014. “Trauma‐Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Youth: Effectiveness in a Community Setting.” Psychological Trauma Theory Research Practice and Policy 6, no. 5: 555–562. 10.1037/a0037364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner, G. G. , Göhre I., Takano K., Ehring T., Wittekind C. E., and Stefanovic M.. 2024. “Temporal Associations Between Trauma‐Related Sleep Disturbances and PTSD Symptoms: An Experience Sampling Study.” Psychological Trauma Theory Research Practice and Policy 16, no. 5: 846. 10.1037/tra0001386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiffen, V. E. , Benazon N. R., and Bradshaw C.. 1997. “Discriminant Validity of the TSC‐40 in an Outpatient Setting.” Child Abuse & Neglect 21, no. 1: 107–115. 10.1016/S0145-2134(96)001342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, L. 1999. “Statistical Methods in Psychology Journals: Guidelines and Explanations.” American Psychologist 54, no. 8: 594–604. 10.1037/0003-066X.54.8.594. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wyers, C. 2021. Examining the Effectiveness of the Trauma Practice Approach for Adults in Treatment [Unpublished Manuscript]. Psychology Department, York University. [Google Scholar]

- Zahra, D. , and Hedge C.. 2010. “The Reliable Change Index: Why Isn't It More Popular in Academic Psychology.” Psychology Postgraduate Affairs Group Quarterly 76, no. 76: 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, K. , Chu J., Zhang X., et al. 2022. “Psychological Resilience and Daily Stress Mediate the Effect of Childhood Trauma on Depression.” Child Abuse & Neglect 125: 105485. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data collected and analyzed in this study are not publicly accessible as they contain sensitive information that could compromise the privacy of the research participants. The data may be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Correspondence regarding this study should be sent to the last author, Robert T. Muller PhD, Professor, Department of Psychology, Faculty of Health, York University, 4700 Keele St., Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M3J 1P3. Email: (rmuller@yorku.ca).