Abstract

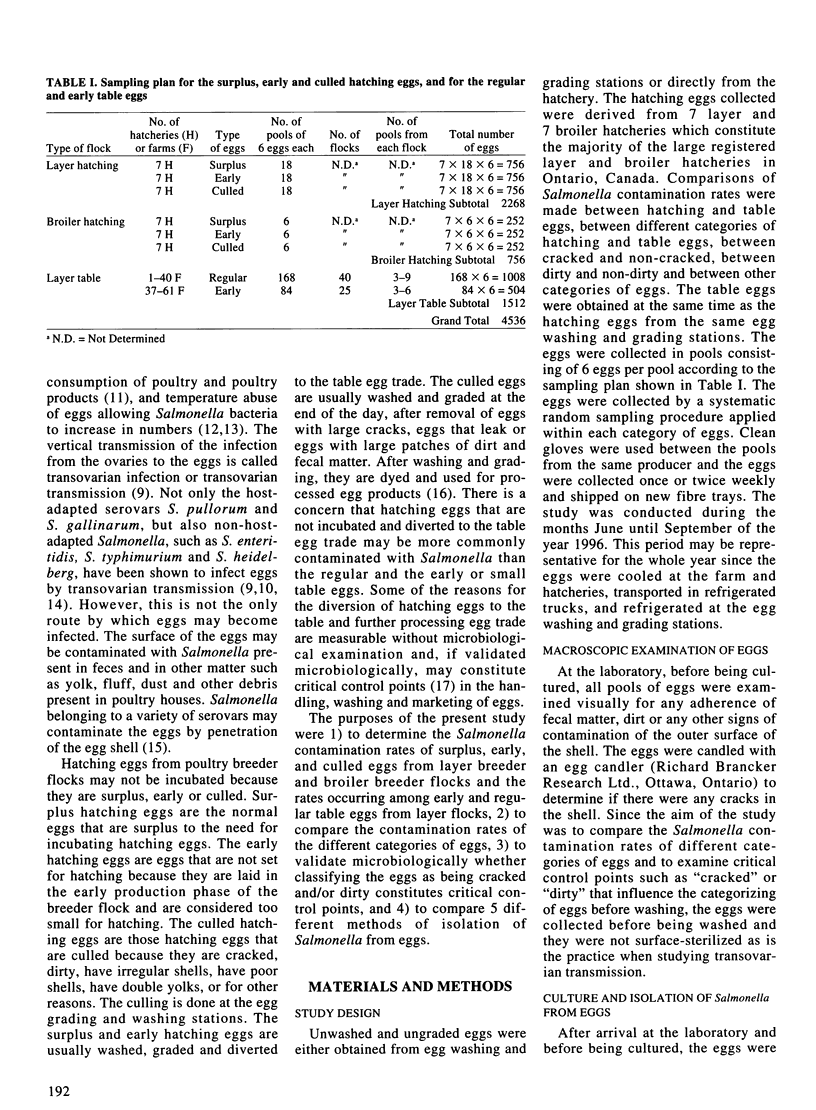

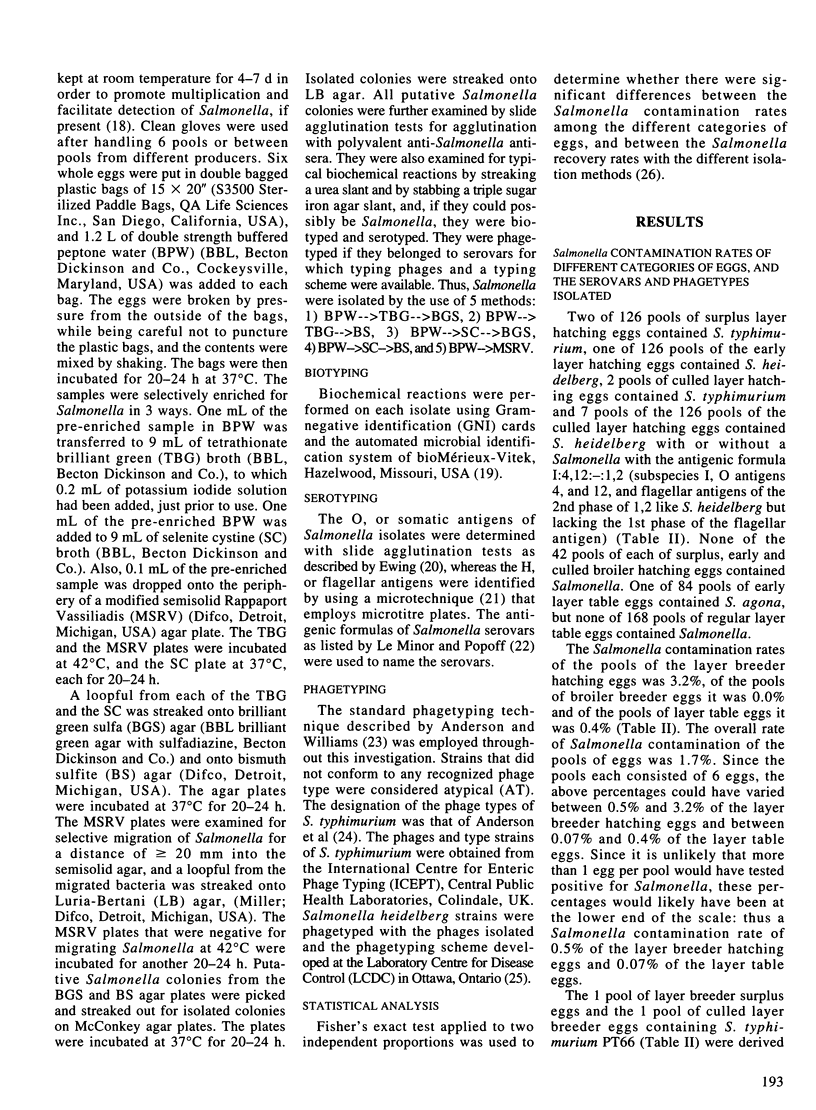

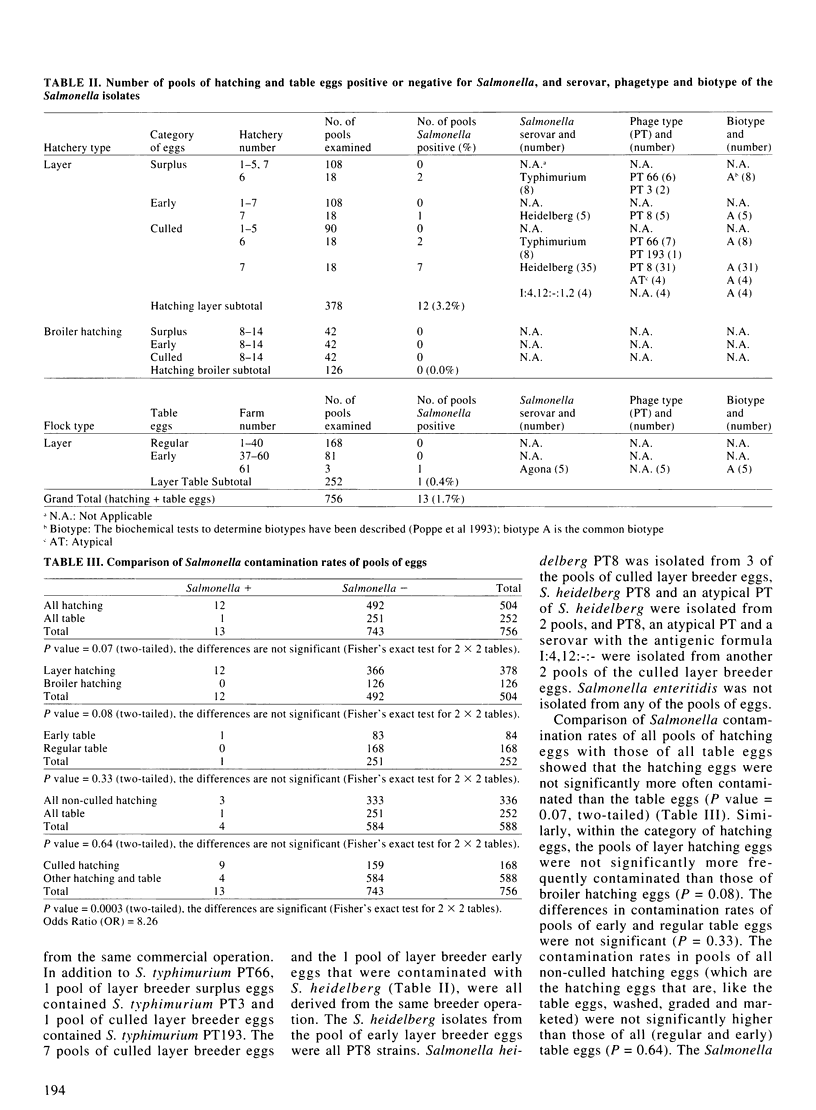

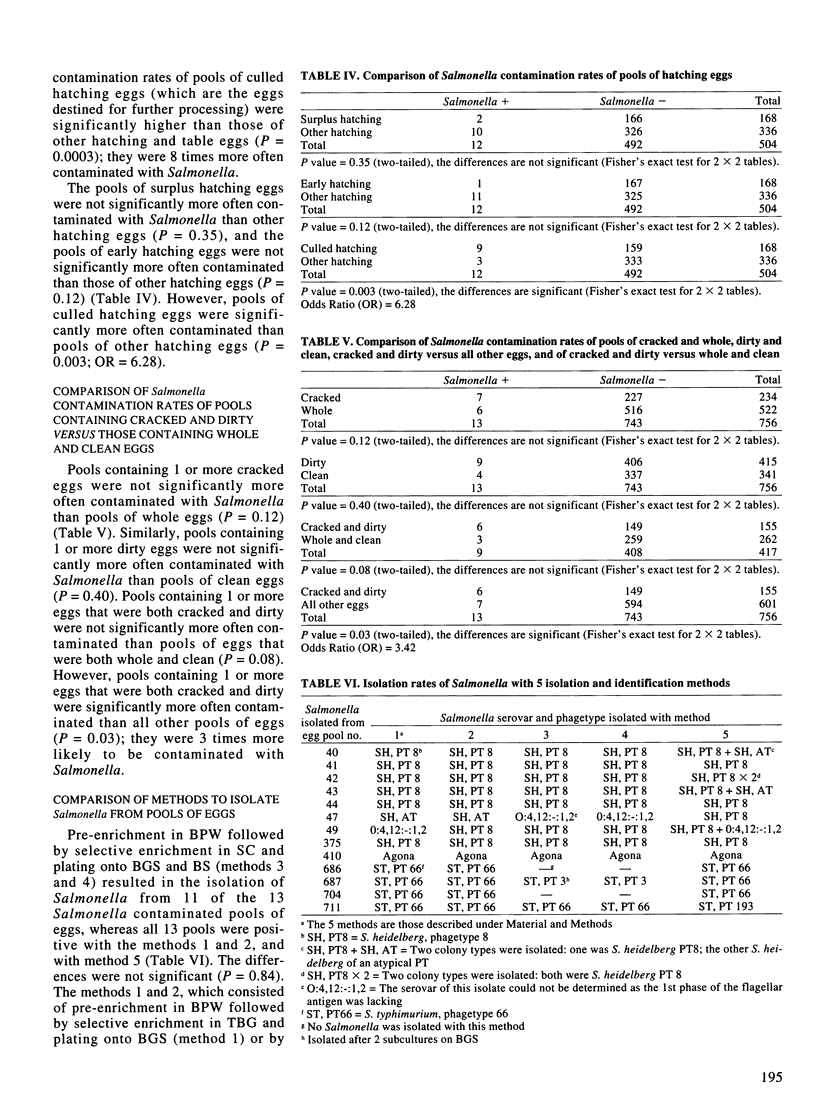

This study determined and compared Salmonella contamination rates of pools of surplus, early and culled hatching eggs from layer and broiler breeder flocks, and of pools of early and regular table eggs from layer flocks. Each pool contained 6 eggs. Five methods were used for the isolation of Salmonella. Nine of 126 pools of culled layer hatching eggs, 2 of 126 pools of surplus layer hatching eggs, and one of 126 pools of early layer hatching eggs were contaminated with Salmonella. All 126 pools of broiler breeder surplus, and early and culled hatching eggs tested negative for Salmonella. All 168 pools of regular table eggs tested negative for Salmonella, whilst one of 84 pools of early table eggs contained Salmonella agona. The pools of culled layer hatching eggs and surplus layer hatching eggs that contained S. typhimurium were derived from the same breeder operation. Similarly, the pools of culled and early layer hatching eggs that contained S. heidelberg were derived from one breeder operation. Pools of culled hatching eggs were more frequently contaminated with Salmonella than other hatching or table eggs. Pools containing eggs that were both cracked and dirty were more frequently contaminated with Salmonella than all other pools of eggs. The overall Salmonella contamination rate of the table eggs was 0.07 to 0.4%. Critical control points (macroscopic classification of the eggs as cracked and dirty) were validated microbiologically.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- ANDERSON E. S., WILLIAMS R. E. Bacteriophage typing of enteric pathogens and staphylococci and its use in epidemiology. J Clin Pathol. 1956 May;9(2):94–127. doi: 10.1136/jcp.9.2.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E. S., Ward L. R., Saxe M. J., de Sa J. D. Bacteriophage-typing designations of Salmonella typhimurium. J Hyg (Lond) 1977 Apr;78(2):297–300. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400056187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspinall S. T., Hindle M. A., Hutchinson D. N. Improved isolation of salmonellae from faeces using a semisolid Rappaport-Vassiliadis medium. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1992 Oct;11(10):936–939. doi: 10.1007/BF01962379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman P. A., Rhodes P., Rylands W. Salmonella typhimurium phage type 141 infections in Sheffield during 1984 and 1985: association with hens' eggs. Epidemiol Infect. 1988 Aug;101(1):75–82. doi: 10.1017/s095026880002923x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clay C. E., Board R. G. Growth of Salmonella enteritidis in artificially contaminated hens' shell eggs. Epidemiol Infect. 1991 Apr;106(2):271–281. doi: 10.1017/s095026880004841x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edel W., Kampelmacher E. H. Salmonella isolation in nine European laboratories using a standardized technique. Bull World Health Organ. 1969;41(2):297–306. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargrett-Bean N. T., Pavia A. T., Tauxe R. V. Salmonella isolates from humans in the United States, 1984-1986. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ. 1988 Jun;37(2):25–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey T. J. Growth of salmonellas in intact shell eggs: influence of storage temperature. Vet Rec. 1990 Mar 24;126(12):292–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khakhria R., Woodward D., Johnson W. M., Poppe C. Salmonella isolated from humans, animals and other sources in Canada, 1983-92. Epidemiol Infect. 1997 Aug;119(1):15–23. doi: 10.1017/s0950268897007577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine W. C., Buehler J. W., Bean N. H., Tauxe R. V. Epidemiology of nontyphoidal Salmonella bacteremia during the human immunodeficiency virus epidemic. J Infect Dis. 1991 Jul;164(1):81–87. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin F. Y., Morris J. G., Jr, Trump D., Tilghman D., Wood P. K., Jackman N., Israel E., Libonati J. P. Investigation of an outbreak of Salmonella enteritidis gastroenteritis associated with consumption of eggs in a restaurant chain in Maryland. Am J Epidemiol. 1988 Oct;128(4):839–844. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- László V. G., Csórián E. S., Pászti J. Phage types and epidemiological significance of Salmonella enteritidis strains in Hungary between 1976 and 1983. Acta Microbiol Hung. 1985;32(4):321–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIlroy S. G., McCracken R. M., Neill S. D., O'Brien J. J. Control, prevention and eradication of Salmonella enteritidis infection in broiler and broiler breeder flocks. Vet Rec. 1989 Nov 25;125(22):545–548. doi: 10.1136/vr.125.22.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poppe C., McFadden K. A., Brouwer A. M., Demczuk W. Characterization of Salmonella enteritidis strains. Can J Vet Res. 1993 Jul;57(3):176–184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rampling A., Anderson J. R., Upson R., Peters E., Ward L. R., Rowe B. Salmonella enteritidis phage type 4 infection of broiler chickens: a hazard to public health. Lancet. 1989 Aug 19;2(8660):436–438. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90604-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigue D. C., Tauxe R. V., Rowe B. International increase in Salmonella enteritidis: a new pandemic? Epidemiol Infect. 1990 Aug;105(1):21–27. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800047609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipp C. R., Rowe B. A mechanised microtechnique for salmonella serotyping. J Clin Pathol. 1980 Jun;33(6):595–597. doi: 10.1136/jcp.33.6.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snoeyenbos G. H., Smyser C. F., Van Roekel H. Salmonella infections of the ovary and peritoneum of chickens. Avian Dis. 1969 Aug;13(3):668–670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telzak E. E., Budnick L. D., Greenberg M. S., Blum S., Shayegani M., Benson C. E., Schultz S. A nosocomial outbreak of Salmonella enteritidis infection due to the consumption of raw eggs. N Engl J Med. 1990 Aug 9;323(6):394–397. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199008093230607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timoney J. F., Shivaprasad H. L., Baker R. C., Rowe B. Egg transmission after infection of hens with Salmonella enteritidis phage type 4. Vet Rec. 1989 Dec 9;125(24):600–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd E. C. Risk assessment of use of cracked eggs in Canada. Int J Food Microbiol. 1996 Jun;30(1-2):125–143. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(96)00995-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wierup M., Engström B., Engvall A., Wahlström H. Control of Salmonella enteritidis in Sweden. Int J Food Microbiol. 1995 May;25(3):219–226. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(94)00090-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]