Summary

Loss of the gene encoding the histone acetyltransferase KAT6B (MYST4/MORF/QKF) causes developmental brain abnormalities as well as behavioral and cognitive defects in mice. In humans, heterozygous variants in the KAT6B gene cause two cognitive disorders, Say-Barber-Biesecker-Young-Simpson syndrome (SBBYSS; OMIM:603736) and genitopatellar syndrome (GTPTS; OMIM:606170). Although the effects of KAT6B homozygous and heterozygous mutations have been documented in humans and mice, KAT6B gain-of-function effects have not been reported. Here, we show that overexpression of the Kat6b gene in mice caused aggression, anxiety, and spontaneous epilepsy. Kat6b overexpression led to an increase in histone H3 lysine 9 acetylation and upregulation of genes driving nervous system development and neuronal differentiation. Kat6b overexpression additionally promoted neural stem cell proliferation and favored neuronal over astrocyte differentiation in vivo and in vitro. Our results suggest that, in addition to loss-of-function alleles, gain-of-function KAT6B alleles may be detrimental for brain development.

Subject areas: Biological sciences, Neuroscience, Behavioral neuroscience, Molecular neuroscience

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

KAT6B overexpression causes aggression, anxiety, and epilepsy

-

•

KAT6B overexpression drives neural stem self-renewal in vitro and in vivo

-

•

KAT6B overexpression promotes neuronal gene expression

-

•

KAT6B overexpression drives neuronal differentiation in vivo and in vitro

Biological sciences; Neuroscience; Behavioral neuroscience; Molecular neuroscience

Introduction

Neural precursor cells give rise to the cellular diversity of the brain during development. In addition, the adult brain retains two populations of neural stem cells (NSCs), in the subgranular zone (SGZ) of the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus1,2 and in the subventricular zone (SVZ) of the lateral ventricles.3 While hippocampal NSCs are required for the generation of excitatory granule cells and memory formation,4,5 SVZ NSCs give rise to neuroblasts that migrate through the rostral migratory stream (RMS) to the olfactory bulbs, where they differentiate into olfactory interneurons.6,7,8,9 Consequently, the olfactory bulbs grow during adult life in mice.

The histone acetyltransferase gene, Kat6b (MYST4/QKF/MORF), is essential for neural precursor cell proliferation during mouse brain development,10 and Kat6b promoter activity correlates strongly with the adult NSC state and declines progressively during differentiation.11 Consistently, mice lacking 90% of Kat6b mRNA (Kat6bgt/gt) have a smaller cortical plate during development and a smaller cerebral cortex in adulthood.10 Their olfactory bulbs fail to grow during adult life.12 In addition, they have fewer NSCs in the SVZ and fewer migrating neuroblasts in the RMS.12 In vitro, Kat6bgt/gt NSCs show reduced self-renewal, proliferation, and neuronal differentiation,12 whereas Kat6b overexpression increases NSC neuronal differentiation,12 demonstrating that neuronal development relies on the appropriate level of KAT6B.

Consistent with a role for KAT6B in brain development and neuronal differentiation, heterozygous pathogenic variants in the KAT6B gene underlie two distinct intellectual disability syndromes, genitopatellar syndrome (GTPTS) and the Say-Barber-Biesecker-Young-Simpson variant of Ohdo syndrome (SBBYSS), as well as an intermediate syndrome or similar disorders.13,14,15,16,17,18,19 Studies in adult mice have similarly shown that Kat6b heterozygous loss results in impaired spatial and social memory and learning, impaired sociability, and anxiety behavior,20 modeling key behavioral traits of individuals with SBBYSS.

The histone acetylation activity of KAT6B has been demonstrated in a cell-free system.10 KAT6B has been found to be essential for H3 acetylation in an individual with heterozygous deletion of the KAT6B gene16 without the specific lysine residues being identified. In cell culture, KAT6B has been reported to be required for histone H3 lysine 14 acetylation (H3K14ac) in HEK293T cells21 or H3K23ac in cancer cells.22,23 In healthy tissues and cells, KAT6B is essential for normal levels of H3K9ac and to a lesser extent required for H3K23ac.20,24 In general, histone acetylation levels are positively correlated with gene expression levels,25,26 suggesting that loss or gain of a histone acetyltransferase should result in a reduction or increase in RNA levels, respectively.

Although loss of KAT6B function has previously been modeled in mice,10,12,20,24 suggesting a certain overlap with SBBYSS,13,16 the consequences of gain of KAT6B function on brain development, behavior, and cognition have not been assessed. Here, we generated mice overexpressing the Kat6b gene and assessed the effects on histone acetylation, gene expression, brain development, adult mouse behavior, NSC abundance, self-renewal, and differentiation. Our data suggest that gain of function of KAT6B drives NSC proliferation and neuronal differentiation and is detrimental to brain development and function.

Results

Kat6b overexpression causes an increase in H3K9ac in the developing mouse cerebral cortex and neural stem and progenitor cells

To determine the effects of Kat6b overexpression, we generated transgenic mice carrying seven additional copies of the wild-type Kat6b allele (Tg(Kat6b) mice24; Figures S1A–S1D), resulting in a 3- to 5-fold increase in Kat6b mRNA (FDRs <10−6; Figure 1A). The hematopoietic defects of Kat6b−/− mice are rescued by the additional presence of the Tg(Kat6b) transgene,24 indicating that the Tg(Kat6b) transgene produces functional KAT6B protein. We assessed global histone acetylation levels at previously reported KAT6B lysine targets, histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9), H3K14 and H3K2320,21,22,23,24 in the embryonic day 12.5 (E12.5) dorsal telencephalon, the E15.5 cortex, and neural stem and progenitor cells (NSPCs) derived from E12.5 dorsal telencephalon, which are tissues and cell types in which Kat6b is highly expressed.10,11 We found elevated H3K9 acetylation (H3K9ac) in all three Tg(Kat6b) cell and tissue types, relative to controls (p = 0.02–0.046; Figures 1B–1D). KAT6B overexpression had no effect on H3K14ac or H3K23ac (Figures S1E–S1P).

Figure 1.

Kat6b overexpression in mice and GTPTS mutations in human cells cause an increase in histone H3 lysine 9 acetylation

(A) Log2 fold change in Kat6b mRNA levels in Tg(Kat6b) E12.5 dorsal telencephalon, E15.5 cortex, or E12.5 neural stem and progenitor cells (NSPCs) compared to wild-type control samples assessed by RNA sequencing. The statistical analysis is described in the STAR Methods section under Analysis of RNA-sequencing data. The cutoff for significant changes is a transcriptome-wide false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05. The FDRs for each RNA source are shown above each bar.

(B–D) Western immunoblot detection and densitometry H3K9ac and pan-H3 as loading control in histones derived from NSPCs (B), E12.5 dorsal telencephalon (C), and E15.5 cortex (D) of Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) mice. Densitometry values (divided by 1,000) are indicated below each band. Each circle in the bar graphs represents one lane of the immunoblot. 500 ng histones loaded per lane.

(E) KAT6B mRNA levels assessed by RT-qPCR normalized to GAPDH in HEK293T cells modified to carry the GTPTS mutations indicated or parental control cells.

(F and G) Western immunoblot (F) detecting H3K9ac, H3K23ac, and pan-H3 as loading control in control HEK293T cells and HEK293T cells modified to carry the p.Val1287Glu∗46 mutation. Densitometry values (divided by 1,000) are indicated below each band. Quantification of immunoblots shown in (G).

(H and I) Western immunoblot (H) detecting H3K9ac or H3K23ac and pan-H3 as loading control in control HEK293T cells and HEK293T cells modified to carry the p.Lys1258Glyfs∗13 mutation. Quantification of each immunoblot shown in (I). N = 3 mice per genotype (B–D) and 3 to 5 clonal cell lines per KAT6B gene variant (E–I). Each lane in (B–D, F, and H) represents histones from NSPCs derived from an individual mouse (B–D) or from a different human cell clone (F and H); 250 ng (H3K23ac) or 500 ng (H3K9ac) protein loaded per lane. Each circle represents RNA (E) or histones (B–D, G, and I) derived from an individual mouse (B–D) or human cell clone (G and I). Data are presented as mean ± SEM (B–E, G, and I) and were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA with Dunnett post-hoc correction (E) or Student’s t test (B–D, G, and I).

Two genitopatellar syndrome mutations cause an increase in H3K9ac in human cells

Human cells with SBBYSS-causing KAT6B variants have reduced H3K9ac and/or H3K23ac.20 To determine whether KAT6B mutations occurring in individuals with GTPTS affect histone acetylation, we used CRISPR/Cas9 and homology-directed-repair (HDR) templates to introduce specific mutations in HEK293T cells validated by DNA sequencing. We chose two GTPTS mutations to model: c.3769_3772delTCTC p.Lys1258Glyfs∗13 and c.3860_3863delTAAC p.Val1287Glufs∗46 (Figure S2A; Table S1). Neither of the introduced KAT6B mutations caused significant changes in KAT6B mRNA abundance (p = 0.3 to 0.6; Figure 1E). Compared to control HEK293T cells, H3K9ac was increased 1.36-fold in p.Lys1258Glyfs∗13 cells and 1.7-fold in p.Val1287Glufs∗46 cells (p = 0.0003 and p = 0.002, respectively; Figures 1F–1I). H3K23ac was increased 1.14-fold in p.Lys1258Glyfs∗13 cells and 1.6-fold in p.Val1287Glufs∗46 cells (p = 0.0008 and p = 0.003, respectively; Figures 1F–1I). H3K14ac levels were unaffected (Figures S2B–S2E). In the absence of reliable antibodies against KAT6B, the effect of GTPTS mutations on protein abundance could not be assessed.

Tg(Kat6b) mice are underrepresented at weaning and have a reduced body weight

Tg(Kat6b) embryos and fetuses were indistinguishable from littermate controls at E12.5 and E18.5 (Figure S3A) and were present at expected Mendelian ratios in utero (Figure S3B). At 3 weeks of age, however, Tg(Kat6b) mice were 38% underrepresented compared to wild-type controls (p < 10−6; Figure 2A). Male and female Tg(Kat6b) mice developed with a reduced body weight compared to wild-type littermate controls over the first 3 weeks of life (p = 0.0003 and 0.003, respectively; Figures 2B–2D), culminating in a weight difference of 14% and 11% at 21 days of age, respectively. In contrast, body length was not different between Tg(Kat6b) mice and controls (Figures S3C and S3D). Tg(Kat6b) mice did not display patella abnormalities at E18.5 (Figure S3E). Despite weighing less than wild-type littermates, Tg(Kat6b) mice reached physical and behavioral milestones assessed as described27 at a similar age as Kat6b+/+ mice (Figures S3F–S3I).

Figure 2.

Kat6b overexpression in mice reduces survival

(A) Number of Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) offspring of Tg(Kat6b) x Kat6b+/+ matings at 3 weeks of age. The total number of mice observed is shown above the bars. The p value is shown above the graph.

(B and C) Bodyweight of male (F) and female (G) Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) mice from postnatal day 1–21.

(D) Representative images of Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) mice at postnatal day (P) 7, 14, and 21; the Tg(Kat6b) mouse is on the right in each picture.

(E) Number of ultrasonic vocalizations observed over 3 min following maternal separation in Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) mice at P4, 8, and 12.

(F) Latency (sec) to the first vocalization following maternal separation in Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) mice at P4, 8, and 12. N = 901 and 561 mice (A), 5–6 mice per sex and genotype (B and C), and 8 mice per genotype (E and F). Each circle in (E and F) represents an individual mouse. Data are displayed as mean ± SEM and were analyzed by chi-squared test (A) and two-way ANOVA with Sidak post-hoc correction (B, C, E, and F).

KAT6B deficiency resulted in reduced frequency of maternal-separation-induced ultrasonic vocalizations (USVs),20 and delayed speech development has been described in some individuals with KAT6B mutations. We assessed maternal-separation-induced USVs in Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) pups at postnatal days 4, 8, and 12 (P4, P8, P12). At P8, Tg(Kat6b) mice showed a tendency for an increase in the number of vocalizations (p = 0.05; Figure 2E) and reduced latency to the first vocalization on P8, compared to control mice (p = 0.008; Figure 2F). No major effects on USV subtype were observed (Figure S4).

Adult Tg(Kat6b) mice display anxiety, aggression, and abnormal social behavior

To assess the effects of Kat6b overexpression on brain function, we performed an extensive battery of behavioral tests. Tg(Kat6b) mice did not display motor impairment, as assessed in the rotarod test (Figure S5A), or differences in strength, based on hanging mesh and grip strength assessments (Figures S5B and S5C). Both genotypes showed similar working vision based on the proportion of time spent on the shallow side of a visual cliff (p < 10−6; Figure S5D). During a 96-h home-cage analysis, Tg(Kat6b) mice showed a normal circadian rhythm (Figure S5E); however, Tg(Kat6b) mice traveled a greater distance and underwent a greater number of transitions between detectors during the light phases (p = 0.01; Figures S5F and S5G). Other parameters assessed were not different between genotypes (Figures S5H–S5L). Based on these tests, Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) mice were considered physically capable of performing behavioral tests assessing cognition, anxiety, aggression, and social interaction.

To assess anxiety, three tests were performed, the large open field, elevated O maze, and elevated plus maze. In the open field test, Tg(Kat6b) mice spent a 1.2-fold greater proportion of time at the periphery of the arena compared to controls (p = 0.002; Figures 3A and 3B), traveled a shorter distance (p < 106; Figure 3C) at a lower speed (p < 106; Figure 3D), and spent a greater proportion of time motionless (p = 0.02; Figure 3E). Tg(Kat6b) mice spent a 10% to 17% greater proportion of testing time in the enclosed arms of the elevated O maze (p = 0.007; Figure 3F) and the elevated plus maze (p = 0.02; Figure 3G). Together, these results suggest elevated anxiety in Tg(Kat6b) mice.

Figure 3.

Kat6b overexpression causes anxiety, aggression, and abnormal social behavior

(A) Representative 5-min traces of the movement of mice in the large open field test. One example of a Kat6b+/+ mouse and two examples of Tg(Kat6b) mouse movements are shown.

(B) Proportion of time spent at the periphery of the open field by Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) mice.

(C–E) Distance traveled (C), average speed (D), and stop fraction (E) of Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) mice in the 20-min open field test.

(F and G) Proportion time spent in the enclosed arms of the elevated O maze (F) and plus maze (G) by Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) mice.

(H) Percentage of Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) males and females exhibiting aggressive behavior in the home cage. The number of mice exhibiting aggressive behavior/total number of mice assessed per sex and genotype is shown above each bar. p values for the genotype effect shown above the graph.

(I) Schematic of the tube dominance test of social aggression.

(J) Percentage of “wins” in the tube dominance test by Tg(Kat6b) vs. Kat6b+/+ mice.

(K–N) Three-chamber social tests. Discrimination index for the mouse vs. empty cage (K), novel vs. familiar mouse 1 h short-term social recognition (L) and novel vs. familiar mouse 24 h long-term social recognition (M). Time spent interacting with either empty cage or mouse during each session (N). N = 11–16 mice per genotype. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Each circle represents an individual mouse. Data were analyzed using an unpaired Student’s t test (B–G), chi-squared test, both sexes combined (H), a one-sample t test compared to a theoretical value of 50 (J) or compared to 0 (K, L, and M), or a two-way ANOVA with Sidak post hoc correction (N).

In both male and female Tg(Kat6b) mice, aggressive behavior in the home cage was observed more frequently than in sex-matched controls (p = 0.01; Figure 3H). Consistently, in a tube-dominance test of social aggression (Figure 3I), male Tg(Kat6b) mice “won” across pairwise interactions with Kat6b+/+ mice 2.8-fold more often than control mice (p = 0.002; Figure 3J), suggesting elevated aggression.

Sociability and social recognition were assessed in a three-chamber social test. Based on a discrimination index of preference, Kat6b+/+ mice showed the expected preference for a mouse over an empty cage in the sociability test (p = 0.007; Figure 3K; session 1), whereas Tg(Kat6b) mice failed to show a preference, suggesting reduced sociability (Figure 3K). Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) mice showed a preference for a novel mouse over a familiar mouse in the 1-h social recall test, demonstrating functioning short-term social recognition (p = 0.003 and 0.04; Figure 3L; session 2). In the 24-h social recall test, the preference of Tg(Kat6b) mice for a novel mouse over a familiar mouse did not reach statistical significance, whereas Kat6b+/+ mice showed the expected preference for the novel mouse (p = 0.03; Figure 3M). The total time that Tg(Kat6b) mice spent interacting with either of the two cages (empty vs. mouse, novel vs. familiar mouse) was reduced compared to wild-type mice in sessions 1 and 3 (p = 0.02–0.01; Figure 3N).

Tg(Kat6b) performed similarly to controls in tests assessing object recognition memory, working memory, and spatial recognition memory, namely the novel object recognition test, Y maze for working memory, and Y maze for spatial recognition memory (Figure S6).

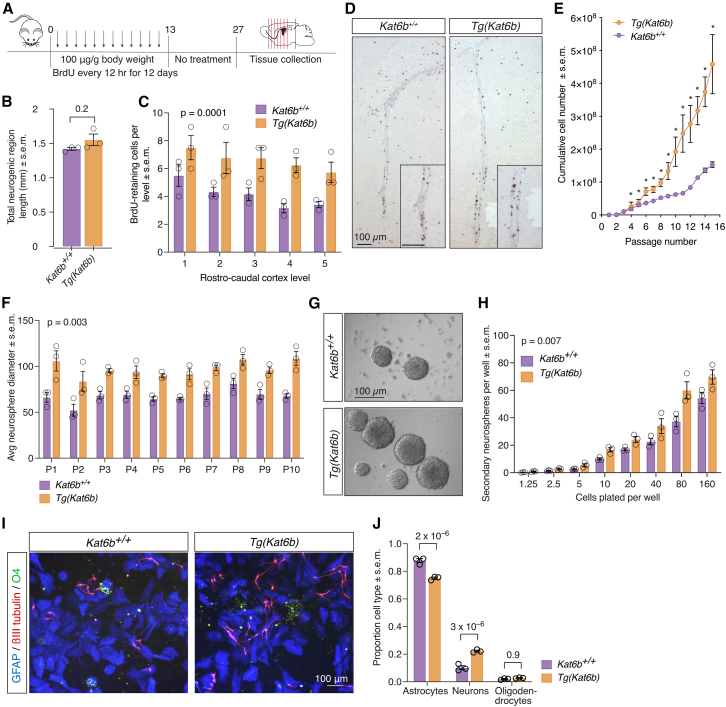

Kat6b overexpression drives NSPC self-renewal and proliferation in vitro and in vivo

In the adult brain, Kat6b is expressed at higher levels in the SVZ of the lateral ventricles, a NSC niche within the adult brain, than elsewhere in the brain.10,12 Consistent with a role for NSC function, mice deficient in Kat6b show fewer NSCs in vivo that, when cultured, show impaired self-renewal and proliferation.12

To assess the effect of KAT6B overexpression on the NSC population of the adult SVZ, Tg(Kat6b) and control mice were injected with the thymidine analogue BrdU twice daily for 2 weeks, followed by a 2-week period without treatment. Brains were harvested, serially coronally sectioned, and sections of the SVZ were stained for BrdU (Figure 4A). No difference was found between genotypes in the total length of the neurogenic region (p = 0.2; Figure 4B), defined between the rostral extremity of the anterior commissure and the rostral extremity of the fimbria hippocampi. Across five rostro-caudal levels, Tg(Kat6b) brains showed increased numbers of BrdU-retaining cells in the SVZ compared to wild-type brains (p = 0.0001; Figures 4C and 4D). When NSC ex vivo were cultured as cell colonies (neurospheres), which are composed of NSPCs, adult Tg(Kat6b) SVZ-derived NSPCs showed significantly increased proliferation over consecutive passages compared to wild-type control NSPCs (Figure 4E), Tg(Kat6b) neurospheres were consistently larger at each passage than control neurospheres (p = 0.003; Figures 4F and 4G). Across a dilution series, Tg(Kat6b) NSPCs gave rise to an increased number of secondary neurospheres compared to control NSPCs (p = 0.007; Figure 4H), demonstrating enhanced self-renewal.

Figure 4.

Kat6b overexpression drives NSPC proliferation in vivo and in vitro and promotes neuronal lineage differentiation in vitro

(A) Schematic of the experimental design for assessment of long-term BrdU retaining cells.

(B) Total length of neurogenic region between the rostral extremity of the anterior commissure and the rostral extremity of the fimbria hippocampi in Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) adult brains.

(C) Number of BrdU+ cells at five rostro-caudal levels spanning the subventricular zone (SVZ).

(D) Representative BrdU immunohistochemistry images of SVZ of Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) mice. BrdU staining appears dark brown.

(E) Cumulative growth curves of adult SVZ-derived NSPCs from Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) mice cultured as neurospheres.

(F) Average diameter of Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) neurospheres over passages (P) 1 to 10.

(G) Representative images of neurospheres at passage 5.

(H) Number of secondary neurospheres derived from Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) NSPCs over number of cells plated per 96-well plate.

(I) Representative images of differentiated Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) NSPCs stained for βIII-tubulin (red, neurons), GFAP (blue, astrocytes), and O4 (green, oligodendrocytes).

(J) Proportion of neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes observed in differentiating Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) NSPCs dissociated and cultured for 5 days in the absence of EGF and FGF2. N = 3 mice per genotype. Data are presented as mean ± SEM and were analyzed using a Student’s t test (B) or two-way ANOVA with Sidak post hoc correction (C, E, F, H, and J). Scale bars, 100 μm in (D, G, and I).

To assess their differentiation capability, SVZ-derived NSPCs were allowed to differentiate by removing the growth factors epidermal growth factor (EGF) and fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2) for 5 days and then stained for βIII-tubulin, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), and O4, markers of neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes, respectively. Tg(Kat6b) NSPCs gave rise to a greater proportion of neurons and reduced proportion of astrocytes compared to control NSPCs (p = 2 × 10−6 and 3 × 10−6; Figures 4I and 4J), whereas oligodendrocyte proportions were unaffected.

Overexpression of Kat6b increases DNA accessibility and expression of genes promoting neuronal differentiation

To assess the effects of Kat6b overexpression on gene expression, we performed RNA sequencing on E12.5 dorsal telencephalon, a time point and tissue type in which KAT6B is highly expressed,10 and on cultured NSPCs from E12.5 Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) embryos.

We found 1,405 differentially expressed genes (FDR <0.05), 779 upregulated and 626 downregulated, in Tg(Kat6b) compared to Kat6b+/+ E12.5 dorsal telencephalon (Figure 5A; Table S2). In Tg(Kat6b) vs. Kat6b+/+ NSPCs, 4,883 were differentially expressed, 2,322 upregulated and 2,561 downregulated (Figure 5B; Table S3).

Figure 5.

Kat6b overexpression drives the expression of genes required for nervous system development and neuronal differentiation

(A–G) RNA-sequencing data of Tg(Kat6b) vs. wild-type E12.5 dorsal telencephalon and NSPCs derived from E12.5 dorsal telencephalon. The statistical analysis is described in the STAR Methods section under Analysis of RNA sequencing data. The cutoff for significant changes is a transcriptome-wide false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05. N = dorsal telencephalon from 4 Tg(Kat6b) and 4 wild-type E12.5 embryos and neural stem cell isolates from 6 Tg(Kat6b) and 2 wild-type E12.5 embryos per genotype. (A and B) Mean-difference (MD) plots showing Tg(Kat6b) vs. Kat6b+/+ E12.5 dorsal telencephalon (A) or NSPC (B) samples. The total numbers of upregulated and downregulated genes at FDR <0.05 are indicated in each comparison. Upregulated genes are represented in red, downregulated in blue, and unchanged genes in black. (C and D) Top 20 Gene Ontology (GO; BP) terms enriched for genes upregulated in Tg(Kat6b) E12.5 dorsal telencephalon (C) or NSPCs (D) vs. control samples. (E) Log2 fold-change of the 30 genes most upregulated in Tg(Kat6b) vs. wild-type NSPCs. The FDR for individual genes is shown inside each bar. (F) Log2 fold-change of genes of the NEUROD gene family. The FDR for individual genes is shown inside each bar. (G) Log2 fold-change of the 30 genes most downregulated in Tg(Kat6b) vs. wild-type NSPCs. The FDR for individual genes is shown inside each bar.

(H and I) ATAC sequencing data of Tg(Kat6b) vs. wild-type NSPCs derived from E12.5 dorsal telencephalon. The statistical analysis is described in the STAR Methods section under Analysis of ATAC sequencing data. N = neural stem cell isolates from 4 Tg(Kat6b) and 4 wild-type E12.5 embryos. (H) Coverage plot of ATAC sequencing reads in NSPCs of Tg(Kat6b) and Kat6b+/+ NSPCs from −1 kb to +1 kb relative to the transcription start site (TSS). (I) Proportion ATAC sequencing reads in Tg(Kat6b) and Kat6b+/+ NSPCs mapped to genomic features: promoters, enhancers (H3K4me1), and active enhancers (H3K4me1 and H3K27ac).

The top 20 Gene Ontology (GO; BP) terms enriched for genes upregulated in Tg(Kat6b) E12.5 dorsal telencephalon compared to wild-type controls were associated with neuronal development and maturation (Figure 5C; Table S2). The top GO (BP) terms enriched for genes upregulated in Tg(Kat6b) NSPCs were associated with nervous system development and cellular respiration (Figure 5D; Table S3). GO (BP) terms downregulated in both datasets were not specific to brain development or NSPC function (Figures S7A and S7B; Tables S2 and S3).

Consistent with an in vitro bias toward the neuronal lineage at the expense of astrocyte development (Figure 4J), Tg(Kat6b) NSPCs showed significant upregulation of transcriptional regulators of neurogenesis compared to wild-type controls. The 30 genes most upregulated in Tg(Kat6b) NSPCs included Neurod1, Neurod6, and Neurog2, as well as the interneuron marker gene Gad2 and the cortical hem gene Dkk3 (Figure 5E; Table S3). Indeed, the NEUROD gene family overall appeared upregulated by overexpression of Kat6b (Figure 5F). Additional important regulators of neuron differentiation were upregulated, including Dcx and Dlx2 (Figures S7C and S7D). The 30 genes most downregulated in Tg(Kat6b) NSPCs included the astrocyte marker gene Gfap (Figure 5G; Table S3). As RNA sequencing was performed on cells grown in the presence of growth factors EGF and FGF, this suggests that even prior to induction of differentiation, Tg(Kat6b) NSPCs appear to be predisposed to differentiate into neurons rather than astrocytes.

The expression of genes encoding KAT6B protein complex members (Brpf1 and 3, Ing4 and 5, Meaf6) and other MYST family histone acetyltransferases (Kat5, Kat6a, Kat7, and Kat8) was not changed in E12.5 dorsal telencephalon, with only minor effects observed in NSPCs (Figures S7E and S7F), suggesting an absence of a compensatory mechanism by regulating these genes.

In contrast, changes in mRNA levels of these genes were observed in HEK293 cells carrying GTPTS mutations. The mRNA levels of genes encoding members of the KAT6B protein complex (BRPF1, ING5, and EAF6) were significantly upregulated in p.Val1287Glufs∗46 HEK293T cells compared to HEK293T cells targeted in a gene desert (p = 0.003 to <10−6; Figure S7G), which could allow the formation of more KAT6B complex. In addition, mRNA levels of all other MYST family genes were upregulated (KAT6A, KAT5, KAT7, and KAT8), such that the increase in histone acetylation cannot be ascribed to the KAT6B p.Val1287Glufs∗46 alone. In contrast, fewer and less prominent changes in mRNA levels were observed in p.Lys1258Glyfs∗1 cells, but even here BRPF1, KAT5, and KAT7 were moderately upregulated (p = 0.03–0.004; S7G).

Histone acetylation is associated with reduced chromatin compaction and increased gene expression,28,29,30 and H3K9ac is most commonly associated with the promoters of actively transcribed genes.25,26 Since we observed a global increase in H3K9ac (Figures 2B and 2C), one would predict an increase in chromatin accessibility. Indeed, we observed a global increase in chromatin accessibility in NSPCs by ATAC sequencing in Tg(Kat6b) compared to Kat6b+/+ NSPCs (Figure 5H; Table S4). This effect was observed at promoters (p < 10−6; Figure 5I) and at active and inactive enhancers regions marked by H3K4me1 and H3K27ac or H3K4me1 alone, respectively (p < 106; Figure 5I).

Kat6b overexpression drives neuronal differentiation and neurite outgrowth

We found no difference between Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) adult brain weight as a percentage of total body weight (Figures S8A and S8B), nor did we find a difference in total brain, cortex, lateral ventricle, or hippocampus volumes or in cortical layering or cellular density between genotypes, across the frontal, parietal, or occipital cortices, based on cresyl violet staining (Figures S8C–S8R). Furthermore, we observed no effect of genotype on cortical layering at E18.5, based on the distribution of superficial, intermediate, and deep cortical layer markers SATB2, CTIP2, and TBR1, respectively (Figures S9A–S9C) or on PAX6 and TBR2 staining in the ventricular and SVZs, respectively (Figures S9D–S9I).

Despite these similarities between the brains of Tg(Kat6b) and control mice, we observed an imbalance between neurons and astrocytes, namely a higher proportion of NEUN (RBFOX3)+ neurons (p = 0.003–0.03; Figures 6A and 6B) and a lower proportion of S100β+ astrocytes (p = 0.006–0.03; Figures 6C and 6D) in Tg(Kat6b) adult cortex compared to controls. The proportions of OLIG2+ oligodendrocytes and IBA1+ microglia cells were unaffected (Figures S10A–S10E). Neurons were also increased in absolute numbers in the adult cortex regions (p = 0.003–0.001; Figure S10E). We further assessed whether overexpression of Kat6b promoted development of specific neuronal subpopulations. We found elevated numbers of CHAT+ cholinergic neurons in the striatum of the frontal cortex (p = 0.04; Figures 6E and 6F) and increased TH+ dopaminergic neurons in the ventral midbrain (p = 0.01–0.02; Figures 6G and 6H). Glutamatergic and serotonergic populations, stained for vGLUT1 (SLC17A7) or vGLUT2 (SLC17A6) and TPH2, respectively, appeared unaffected by Kat6b overexpression (Figures S10F–S10K). While we observed a significant increase in parvalbumin+, somatostatin+, calbindin+, and calretinin+ inhibitory neuronal populations in the Tg(Kat6b) vs. wild-type parietal cortex (Figures 6J and 6K; Figure S10L), there was only a marginal increase in inhibitory neurons in the frontal cortex (Figures S10M and S10N) and no significant difference in the occipital cortex (Figures S10O and S10P).

Figure 6.

Adult Tg(Kat6b) mice have more NEUN+ neurons and fewer S100β+ astrocytes in the cortex

(A) Representative immunofluorescence images of coronal frozen sections of the frontal cortex of Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) mice stained for the neuron marker NEUN (RBFOX3), counterstained with DAPI.

(B) Quantification of the proportion NEUN+ of total DAPI+ cells in the frontal, parietal, and occipital cortices in area overlying a length of 400 μm of the ventricular surface for the full depth of the cortex.

(C) Representative immunofluorescence images of coronal frozen sections of the frontal cortex of Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) mice stained for the astrocyte marker S100β, counterstained with DAPI.

(D) Quantification of number of S100β+ as a proportion of total DAPI+ cells across the frontal, parietal, or occipital cortices in area overlying a length of 400 μm of the ventricular surface for the full depth of the cortex.

(E) Representative immunohistochemistry images of coronal paraffin sections stained for the cholinergic neuron marker choline acetyltransferase (CHAT) in Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) caudoputamen.

(F) Quantification of the number of CHAT+ cells per caudoputamen.

(G) Representative immunohistochemistry images of coronal paraffin sections stained for the dopaminergic neuron marker tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) in Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) ventral midbrain.

(H and I) Quantification of the number of TH+ cells per unit area (H) and staining intensity (I) in the ventral midbrain.

(J) Representative images of coronal vibratome sections stained for the inhibitory neuronal markers parvalbumin (PVALB, green), somatostatin (SST, magenta), calbindin (CALB1, yellow), and calretinin (CALB2, cyan) in the parietal cortex of Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) adult mice.

(K) Enumeration of the density of total inhibitory neurons, normalized to volume, at distances from the pia as specified. N = 3–4 mice per genotype. Data in are presented as mean ± SEM (B, D, F, H, I, and K). Each circle (B, D, F, H, and I) represents an individual mouse. Data were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA with Sidak post-hoc correction (B, D, and K) or an unpaired Student’s t test (F, H, I). Scale bars, 100 μm in (A, C, and J) and 500 μm in (E and G).

Neuronal morphology was assessed in vivo using Golgi-Cox staining. Upper layer neurons, sufficiently isolated to allow for accurate distinction of the neurites of an individual cell, were assessed by Sholl analysis31 for neurite complexity (Figure 7A). Tg(Kat6b) neurons showed an increased number of intersections, specifically from 30 to 60 μm from the cell body, compared to controls (p = 0.00002–0.004; Figure 7B) and a greater total neurite length (p = 0.04; Figure 7C). Similarly, in vitro, E16.5 cortical neurons cultured for 5 days in vitro showed an increase in the number of secondary neurites compared to controls, as well as quaternary neurites, which did not form at all in wild-type cultures after 5 days of culture (p = 0.001; Figures 7D and 7E).

Figure 7.

Kat6b overexpression causes spontaneous tonic-clonic seizures and epileptiform EEG brain activity before and after kindling and promotes neurite outgrowth

(A) Representative traces of Golgi-Cox-stained neurons in vibratome sections of adult cortex of Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) mice.

(B) Sholl analysis of Golgi-Cox-stained upper layer neurons from Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) mice. ∗p < 0.05.

(C) Average total neurite length of neurons from Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) adult brains following Golgi-Cox staining.

(D) Representative images of cultured E16.5 cortical neurons from Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) fetuses, stained for βIII tubulin and DAPI. Primary (white), secondary (yellow), and tertiary neurites (green) are traced (right images).

(E) Total number of primary to quaternary neurites in Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) E16.5 cortical neurons.

(F) Percentage of Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) mice with observed spontaneous tonic-clonic seizures in the home cage. The number of mice with observed seizures over total number of mice assessed per genotype is shown above each bar. The p value for the genotype effect is shown above the graph.

(G–I) Number of days on which spikes (G), spike-wave-discharges (SWDs; H), and periodic epileptiform discharges (PEDs; I) were observed in Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) mice during baseline assessment (prior to kindling).

(J) Schematic drawing of electric kindling induction of epilepsy.

(K and L) After-discharge threshold (K) and number of stimulations to the first-class V seizure (L) in Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) mice.

(M) Average seizure duration across 30 stimulations (2x stimulations per day over 15 days) in Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) mice.

(N) Average seizure class (I–V) across 30 stimulations (2x stimulations per day over 15 days) in Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) mice.

(O–Q) Number of days following kindling on which spikes (O), spike-wave-discharges (SWDs; P) and periodic epileptiform discharges (PEDs; Q) were observed in Kat6b+/+ and Tg(Kat6b) mice. N = 3 mice per genotype (A–E), 199 Kat6b+/+ and 136 Tg(Kat6b) mice (F), and 9 Kat6b+/+ and 8 Tg(Kat6b) mice (G–Q). Each circle in (C, E, G–I, K, L, O–Q) represents an individual mouse. Data are presented as mean ± SEM and were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Sidak correction (B, E, M, and N), unpaired Student’s t test (C, G–I, K, L, O–Q), or chi-squared test (F). Scale bars, 50 μm in (A) and 100 μm in (D).

Tg(Kat6b) mice have spontaneous tonic-clonic seizures and a predisposition to kindling-induced epileptogenesis

We observed spontaneous convulsive (tonic-clonic) seizures in 4% of Tg(Kat6b) mice compared to no incidences of seizures in wild-type mice (p = 0.007; Figure 7F). To formally assess epileptogenic predisposition, electroencephalogram (EEG) experiments were performed. In this baseline examination, Tg(Kat6b) compared to wild-type mice displayed more EEG activity, namely more days on which spikes, spike-wave-discharges, and periodic-epileptiform-discharges were observed (p = 0.0006, 0.05, and 0.0002, respectively; Figures 7G–7I).

To further assess epileptogenic predisposition, a kindling study was performed. Mice received twice-daily electric stimulations directed to the amygdala to induce seizures for 15 days, followed by a 20-day period of video and EEG monitoring to assess for spontaneous events (Figure 7J). During the stimulation period, no differences were observed between genotypes in the average after-discharge threshold (Figure 7K), the number of stimulations needed to achieve the first-class V seizure (Figure 7L), average seizure duration (Figure 7M), or the average seizure class over the course of kindling (Figure 7N). However, in the post-kindling monitoring period, Tg(Kat6b) mice exhibited a 4- to 18.6-fold increase in epileptiform EEG activity in the form of spikes, spike-wave-discharges, and periodic-epileptiform-discharges compared to controls (p = 0.01–<10−6; Figures 7O–7Q). Consistent with our observations of spontaneous epilepsy, this indicates a heightened sensitivity to epileptiform activities in Tg(Kat6b) mice compared to Kat6b+/+ controls.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that Kat6b overexpression in mice caused anxiety, aggression, and seizures. Tg(Kat6b) mice did not display learning and memory defects in the simple tests that we applied here. In addition to the tests described, we also attempted to test the Tg(Kat6b) mice in the more complex Barnes maze tests,32,33 which assess spatial learning, memory, and search strategy development. However, Tg(Kat6b) mice failed to explore the maze, spending much of the testing period frozen. This freezing behavior may result from the elevated anxiety of this genotype, as observed in other behavioral tests. This performance-limiting behavior precluded the assessment of Tg(Kat6b) mice in more elaborate tasks.

Consistent with our observations of elevated anxiety and aggression, combined with increases in the number of cholinergic neurons in Tg(Kat6b) mice, increased cholinergic signaling has been shown to promote anxiety (reviewed in34) and aggression.35 The neurotransmitter acetylcholine is synthesized by choline acetyltransferase (CHAT) and hydrolyzed by acetylcholinesterase (ACHE), with chemical inhibition or shRNA knockdown of the latter shown to elevate anxiety behavior.36

In contrast, the effects of dopaminergic neurons on anxiety and aggression are less clear. Although we observed increased numbers of dopaminergic neurons and increased anxiety in Tg(Kat6b) mice, dopaminergic signaling is thought to be required to overcome anxiety in risk vs. reward-type cognitive assessments (e.g., foraging despite the presence of predators).37 In addition, optogenetic depolarization of dopaminergic ventral tegmental area neurons was associated with elevated social aggression.38,39 Increased aggression was also exhibited in mice lacking the dopamine transporter, DAT,40 or specific DAT+ neurons41 and following pharmacological blockade of DAT.39

We also observed increased numbers of interneurons in adult Tg(Kat6b) mice, congruent with fewer GAD67+ interneurons in KAT6B-deficient mice.10 Consistent with our observations of elevated anxiety in Tg(Kat6b) mice, stress-induced increases in prefrontal parvalbumin expression and activity of parvalbumin+ cells correlate with increased anxiety in female mice.42,43 While acute pharmacogenetic inhibition of somatostatin-expressing neurons has been reported to increase anxiety behavior, chronic inhibition or ablation of somatostatin neurons decreases anxiety-like behavior.44

Tg(Kat6b) mice displayed cell-type imbalances, which may also underlie their seizure susceptibility. Imbalances in excitatory and inhibitory neuronal signaling have been proposed to cause epilepsy,45,46,47 including in cholinergic and dopaminergic signaling. For example, mice lacking the M1 receptor, the most abundant acetylcholine receptor in the brain, but not those lacking receptors M2-5, show resistance to seizure development after administration of the epileptogenic agent, pilocarpine.48 Conversely, reduced CHAT activity was found in the piriform cortex, amygdala, and nucleus basalis of rats in the post-kainic acid model of epilepsy,49 whereas increased dopamine levels50 and increased firing of dopaminergic neurons51 have been shown in rodent models of temporal lobe epilepsy. Many dopaminergic compounds also have anti-epileptic effects.52,53 Interestingly, loss, rather than gain, of inhibitory interneuron input to excitatory neurons is associated with epilepsy predisposition.54,55 Grafting inhibitory neuron progenitors into the hippocampus56 and optogenetic activation of parvalbumin expressing interneurons reduce seizure activity.57 However, other studies suggest that abnormally functioning somatostatin+ interneurons can contribute to seizure pathogenesis,58 parvalbumin+ inhibitory neurons contribute to seizure activity, possibly by acquiring an aberrant excitatory function after activity-dependent Cl− ion accumulation,59 and optogenetic inhibition of parvalbumin or somatostatin has been shown to decrease seizure duration.60 Hence, the increased number of interneurons in Tg(Kat6b) mice may contribute to the spontaneous seizures and predisposition to the post-kindling epilepsy.

Despite significant differences between Tg(Kat6b) and control mice in the frequency of epileptic EEG activity in the pre- and post-kindling periods, we saw no difference in the severity of seizures during the kindling process. This may be because the dynamic range of kindling-induced epileptogenesis was insufficient to detect a subtle difference between Tg(Kat6b) and control mice during the kindling period. Alternatively, amygdala kindling may not recruit the same circuits as those affected in the spontaneous seizures of Tg(Kat6b) mice. The kindling process causes an enduring state of heightened excitability. The striking observations of epileptiform activity during the pre- and post-kindling monitoring periods suggest that the epileptiform activity is magnified in Tg(Kat6b) mice. Such a phenotype is consistent with the (rare) observations of spontaneous seizures in the home cage and indicates that Kat6b overexpression causes a predisposition to seizure development.

Molecularly, we show that KAT6B promoted acetylation of H3K9 in mouse cells and H3K9 and H3K23 in human cells. This observation overlaps with previous work, where KAT6B was found to be important for H3K23ac in small-cell lung cancer,23 K562 lymphoblast, and HEK293 cells.22 Combined, these findings indicate that KAT6B directly or indirectly mediates H3K9 and/or H3K23 acetylation in a cell-type-dependent fashion, possibly depending on the availability of other KAT6 protein complex members. We also found that KAT6B promoted DNA accessibility and the expression of regulators of neuronal differentiation. Consistently, we found an increased number of neurons (and fewer astrocytes) in the brain of adult Tg(Kat6b) mice and a neuronal differentiation bias in Tg(Kat6b) NSPCs. Elevated NSC neuronal differentiation is the opposing phenotype to what has been found for mice and NSCs deficient in KAT6B,10,12 indicating that NSC neurogenesis is reliant on the level of KAT6B.

Our finding that two GTPTS-causing mutations do not affect KAT6B mRNA levels, indicating that these mutant transcripts do not undergo nonsense-mediated decay (NMD), was consistent with a previous report.19 Together with this previous study,19 our data support the hypothesis that GTPTS-causing alleles may escape NMD, enabling the production of an abnormal protein product. In addition, we observed an increase in histone acetylation at H3K9 and H3K23 in human cells carrying two GTPTS mutations, suggesting a gain in acetylation activity. Conversely, SBBYSS mutations cause a decrease in H3K9 and H3K23 acetylation,20 and KAT6B deficiency in mice has been shown to model key cognitive and behavioral aspects of SBBYSS.20 By comparison, we observed elevated H3K9ac in HEK293T cells with two GTPTS-causing variants and in Tg(Kat6b) mice and found elevated anxiety, aggression, and spontaneous epilepsy in Tg(Kat6b) mice, all traits described in some individuals with GTPTS61; however, we did not observe other clinical traits of GTPTS, including the defining skeletal abnormalities, craniofacial abnormalities, microcephaly, agenesis or hyperplasia of the corpus callosum, patellar abnormalities, or urogenital anomalies.

Limitations of the study

Genetically, the Kat6b copy-number increase that we have generated to overexpress KAT6B in Tg(Kat6b) mice does not occur in human developmental disorders. While KAT6B is the 38th most commonly amplified gene across all cancers, to date only small intragenic duplications have been described in association with genetic disorders.17,61,62 Moreover, individuals with SBBYSS or GTPTS present with cognitive impairment,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,61 whereas Tg(Kat6b) mice did not display learning and memory defects. Nevertheless, since the performance-limiting anxiety behavior precluded the assessment of Tg(Kat6b) mice in more elaborate learning and memory tasks, it is possible that Tg(Kat6b) mice have cognitive defects not revealed in our study. The discrepancies (discussed above) in the clinical presentation of GTPTS and anomalies observed in Tg(Kat6b) mice indicate that several GTPTS traits are unlikely the result of a simple gain of normal KAT6B function and are likely due to a different effect of KAT6B mutations on protein function, such as a dominant-negative or a gain of an abnormal function. For example, a truncating mutation could eliminate a reported intrinsic transactivation potential ascribed to the carboxy-terminus of KAT6B.63 Of these possibilities, dominant-negative effects are most likely, given that agenesis or hypoplasia of the corpus callosum and hindlimb skeletal anomalies were observed in mice homozygous for a Kat6b allele producing only 10% of normal Kat6b mRNA.10,16

In conclusion, this study provides an in vitro and in vivo assessment of the consequences of KAT6B overexpression in the developing and adult mouse brain. We show that overexpression of KAT6B causes molecular, cellular, and behavioral anomalies. Our assessment of a gain of KAT6B function in a mouse model suggests that GTPTS is unlikely to result from a simple increase in normal KAT6B levels, whereas other functional states are more likely, such as a dominant-negative effect or the gain of an abnormal protein function.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Requests for further information should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Anne. K Voss (avoss@wehi.edu.au).

Materials availability

Tg(Kat6b) mice generated in this study have been submitted to the Jackson Laboratory mouse archive (symbol: Tg(Kat6b)21Avo, accession number MGI:7653702). Requests for further resources should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Anne. K Voss (avoss@wehi.edu.au).

Data and code availability

High-throughput sequencing data from RNA-sequencing and ATAC-sequencing experiments are accessible at GEO with accession numbers GSE267675,64 GSE280783, 64 and GSE280784.64 Any additional information required is available from the lead contact upon request. This paper did not generate custom code.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge F. Dabrowski, L. Wilkins, N. Blasch, S. Bound, E. Boyle, J. Gilbert, L. Johnson, and S. Oliver for exceptional animal care; R. May, C. Burström, S. Wilcox, and the Walter and Eliza Hall Histology department for excellent technical support; C. Chavez for invaluable technical advice and guidance; and D. Butts for BAC purification. M.I.B. was supported by an Australian Government Postgraduate Award. H.K.V. was supported by the Al and Val Rossentraus fellowship. P.M.C.-E. was supported by an Early Career Fellowship from the National Health and Medical Research Council (APP1087172). The program of work was supported by the Pamela and Lorenzo Galli Charitable Trust and the National Health and Medical Research Council, Australia through Project Grants 1010851 to A.K.V. and T.T.; 1160517 to T.T.; Ideas Grant 2010711 to T.T.; Research Fellowships 1003435 to T.T, 575512 and 1081421 to A.K.V., and 1154970 to G.K.S.; and Investigator Grants 1176789 to A.K.V. and 1194345 to M.E.B.; through the Independent Research Institutes Infrastructure Support Scheme; by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, United States of America through grant 2021-237445 to G.K.S.; by a grant from Department of Defense USA Epilepsy Research Program (EP200022) and by the Department of Health and Aged Care, Australia through an MRFF - Stem Cell Therapies Mission grant (MRF2015957) to P.M.C.-E.; and by the Victorian Government, Australia through an Operational Infrastructure Support Grant.

Author contributions

M.I.B. designed and carried out experiments, performed data analyses, and drafted the manuscript. E.O. and P.M.C.-E. performed experiments, supervised by N.C.J. V.C.W. carried out experiments, and P.R. and L.W. performed analyses supervised by K.R. A.L.G. and W.A. performed bioinformatics data analyses supervised by G.K.S. H.K.V. carried out experiments supervised by M.E.B. and A.K.V. A.P.V. and A.J.H. contributed to the experimental design and data interpretation. A.K.V. and T.T. conceived the project, designed experiments, performed analyses, and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and contributed to the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

A.K.V. and T.T. are inventors on patent WO2016198507A1. A.K.V. and T.T. have received research funding from the CTx CRC. A.K.V. and T.T. have served on a clinical advisory board for Pfizer.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| βIII tubulin, clone 5G8 | Promega | G7121 |

| GFAP | Dako | Z0334 |

| O4, clone 81 | Millipore | MAB345 |

| NEUN | Abcam | Ab104225 |

| S100β, clone EP1576Y | Abcam | Ab52642 |

| OLIG2, EPR2673 | Abcam | Ab109186 |

| IBA1 | FUJIFILM Wako | 019–19741 |

| SATB2, SATBA4B10 | Abcam | Ab51502 |

| CTIP2, S5B6 | Abcam | Ab18465 |

| TBR1 | Abcam | Ab31940 |

| PAX6 | Merck | Ab2237 |

| TBR2 | Abcam | Ab23345 |

| ChAT, clone EPR16590 | Abcam | Ab178850 |

| TPH2, clone EPR19191 | Abcam | Ab184505 |

| Tyrosine Hydroxylase | Merck | Ab152 |

| vGLUT1, clone CL2754 | ThermoFisher | MA531373 |

| vGLUT2, clone 8G9.2 | Abcam | Ab79157 |

| Somatostatin, clone YC7 | Novus Biologicals | NOVNB10064650 |

| Calbindin | ThermoFisher | PA546936 |

| Calretinin, clone SP13 | ThermoFisher | MA514540 |

| Parvalbumin, clone PARV-19 | Sigma | P3088 |

| BrdU, clone Bu20a | Dako | M0744 |

| Donkey anti-rat Alexa Fluor 555 | Invitrogen | A48270 |

| Donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 594 | Invitrogen | A21207 |

| Donkey anti-goat Alexa Fluor 647 | Jackson ImmunoResearch | 705-605-147 |

| Donkey anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 | Invitrogen | A21202 |

| Goat anti-rabbit AMCA | Jackson ImmunoResearch | 111-156-003 |

| Goat anti-rat IgG Alexa Fluor 568 | ThermoFisher | A11077 |

| Goat anti-mouse IgG Alexa Fluor 488 | Invitrogen | A11029 |

| Goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 546 | ThermoFisher | A11035 |

| Goat anti-mouse IgM FITC | Vector Laboratories | F12020 |

| Goat anti-rabbit IgG TRITC | Jackson ImmunoResearch | 111-025-003 |

| Anti-Histone H3 Lysine 9 | Epicypher | 130033 |

| Anti-Histone H3 Lysine 14, clone EP964Y | Abcam | Ab52946 |

| Anti-Histone H3 Lysine 23 | Millipore | 07355 |

| Pan Histone H3, clone Sp2/0-Ag14 | Abcam | Ab10799 |

| Anti–rabbit secondary | Li-COR | 926–68071 |

| Anti–Mouse secondary | Li-COR | 926–32210 |

| Biological samples | ||

| Tissue samples isolated from mice | This study | |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Rapid Golgi Cox stainTM kit | FD Neuro Technologies | PK402 |

| Qiagen RNeasy mini kit | Qiagen | 74104 |

| TruSeq stranded mRNA library Construction kit | Illumina | 20020594 |

| Dako Omnis Agilent Platform | Agilent | Dako Omnis |

| Deposited data | ||

| ATAC-sequencing data of NSPCs | Bergamasco et al., 202464 and this study | GSE267675 |

| RNA-sequencing data of NSPCs | Bergamasco et al., 202464 and this study | GSE280783 |

| RNA-sequencing data of the developing cortex | Bergamasco et al., 202464 and this study | GSE280784 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| Neural stem and progenitor cells isolated from adult mouse subventricular zone or E12.5 embryonic dorsal telencephalon | This study | |

| Primary cortical neurons isolated from E16.5 cortex | This study | |

| HEK293T cells | In house | HEK293T |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Tg(Kat6b) mice | In house | Tg(Kat6b) mice |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| 5′-GGATTTGGACGGTTTCTCATTG-3′ | This study | KAT6B (human) Fwd |

| 5′-GAGATACTCCAAGATGACGCTC-3′ | This study | KAT6B (human) Rev |

| 5′-TGCACCACCAACTGCTTAGC-3′ | Wichmann et al., 202265 | GAPDH (H) Fwd |

| 5′-GGCATGGACTGTGGTCATGAG-3′ | Wichmann et al., 202265 | GAPDH (H) Rev |

| 5′-AACTAACGGTTCGAGTGAAGG-3′ | This study | KAT6A (human) Fwd |

| 5′-ACTCCATGTGAAAACCTCGG-3′ | This study | KAT6A (human) Rev |

| 5′-TTTGACCAAGTGTGACCTACG-3′ | This study | KAT5 (human) Fwd |

| 5′-GCCAAAAGACACAGGTTCTG-3′ | This study | KAT5 (human) Rev |

| 5′-AGCCCTTCCTGTTCTATGTTATG-3′ | This study | KAT7 (human) Fwd |

| 5′-CATAGCCCTGTCTCATGTACTG-3′ | This study | KAT7 (human) Rev |

| 5′-GGGAAAGAGATCTACCGCAAG-3′ | This study | KAT8 (human) Fwd |

| 5′-TCCACGTCAAAGTACAGTGTC-3′ | This study | KAT8 (human) Rev |

| 5′-TGCTCGTGGAATTGATCCG-3′ | This study | BRPF1 (human) Fwd |

| 5′-TTGCCTGTGTCCTTCTCTTG-3′ | This study | BRPF1 (human) Rev |

| 5′-AGCTGCAAGACAAGGACC-3′ | This study | BRPF2 (human) Fwd |

| 5′-TGAGCTTCTAACCGTTTCCTC-3′ | This study | BRPF2 (human) Rev |

| 5′-TCGGAAGTTGCTTTGTTTTGC-3′ | This study | ING4 (human) Fwd |

| 5′-GGTCCTCTGTTCTTTGGTCTAG-3′ | This study | ING4 (human) Rev |

| 5′-ACCTTACCACGAAACCCAAAG-3′ | This study | ING5 (human) Fwd |

| 5′-GAAGGGAAATATTGCGACACG-3′ | This study | ING5 (human) Rev |

| 5′-CCTGGAAGACACTCAGATGTATG-3′ | This study | EAF6 (human) Fwd |

| 5′-CCGAGGATTTACTGAAGAGCC-3′ | This study | EAF6 (human) Rev |

| 5′-CAACTCAATCGACAGCTGGA-3′ | This study | sacb L (in BAC backbone) |

| 5′-GGCTTTGTTTGCCGTAATGT-3′ | This study | sacb R (in BAC backbone) |

| 5′-TTGGAAGGCCATCATTCTAGG-3′ | This study | YRPT_1 (Y repeat) |

| 5′-CATCCCACTCCAGTTGTCCT-3′ | This study | YRPT_2 (Y repeat) |

| 5′-AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATC TACACCGATAGGGTCGTCGGCAG CGTCAGATGTGTAT-3′ |

Mezger et al., 201866 | V2_P5.61 (ATAC-seq) |

| 5′-CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATGCA TTAAAGTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTG-3′ | Mezger et al., 201866 | V2_P7.60 (ATAC-seq) |

| 5′-CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATATCA TCATGTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTG-3′ | Mezger et al., 201866 | V2_P7.63 (ATAC-seq) |

| 5′-CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATTGT TGTTAGTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTG-3′ | Mezger et al., 201866 | V2_P7.65 (ATAC-seq) |

| 5′-CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATGGTC GATGGTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTG-3′ | Mezger et al., 201866 | V2_P7.67 (ATAC-seq) |

| 5′-CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATAT TGGCCGGTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTG-3′ |

Mezger et al., 201866 | V2_P7.69 (ATAC-seq) |

| 5′-CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATGC ACGGCGGTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTG-3′ |

Mezger et al., 201866 | V2_P7.78 (ATAC-seq) |

| 5′-CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATTCGA AATGGTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTG-3′ |

Mezger et al., 201866 | V2_P7.80 (ATAC-seq) |

| 5′-CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATTGG CAAGCGTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTG-3′ |

Mezger et al., 201866 | V2_P7.81 (ATAC-seq) |

| 5′-AATGATACGGCGACCACCGA-3′ | Mezger et al., 201866 | Illumina P5 (ATAC-seq) |

| 5′-CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGAT-3′ | Mezger et al., 201866 | Illumina P7 (ATAC-seq) |

| 5′-GTGACCTATGAACTCAGGAGTCCAGC TCAGGTTCTGGGAGAG-3′ |

This study | Eco R1 control Fwd (CRISPR/Cas9 MiSeq) |

| 5′-CTGAGACTTGCACATCGCAGCCATCC TTAGGCCTCCTCCTT-3′ |

This study | Eco R1 control Rev (CRISPR/Cas9 MiSeq) |

| 5′-GTGACCTATGAACTCAGGAGTCGTTGC CCATGGTTATGCTTT-3′ |

This study | p.Lys1258Glyfs∗13 Fwd (CRISPR/Cas9 MiSeq) |

| 5′-CTGAGACTTGCACATCGCAGCCCACT GTTACCTGCTCGTCA-3′ |

This study | p.Lys1258Glyfs∗13 Rev (CRISPR/Cas9 MiSeq) |

| 5′-GTGACCTATGAACTCAGGAGTCAAACA AGTGTGGCCAAAAGG-3′ |

This study | p.Val1287Glufs∗46 Fwd (CRISPR/Cas9 MiSeq) |

| 5′-CTGAGACTTGCACATCGCAGCACAGG GGCACATGTTTCTTC-3′ |

This study | p.Val1287Glufs∗46 Rev (CRISPR/Cas9 MiSeq) |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| 5′-AGCCATCTCTCTCCTTGCCAGAACCTCTAA GGTTTGCTTAGAATTCCGATGGAGCCAGAG AGGATCCTGGGAGGGAGAGCTTGGCA-3′ |

This study | EcoR1 control ssHDR (CRISPR/Cas9 ssHDR template) |

| 5′-GTGACCTATGAACTCAGGAGTCGT TGCCCATGGTTATGCTTT-3′ |

This study | p.Lys1258Glyfs∗13 ssHDR (CRISPR/Cas9 ssHDR template) |

| 5′-GTGACCTATGAACTCAGGAGTCAA ACAAGTGTGGCCAAAAGG-3′ |

This study | p.Val1287Glu∗46 ssHDR (CRISPR/Cas9 ssHDR template) |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Prism Graphpad Software | Graphpad | Version 9.5.1 |

| R | R project for Statistical Computing | RRID:SCR_001905 |

| R packages Rsubread, edgeR and limma | Bioconductor | RRID:SCR-006442 |

| DAVID | david.ncifcrf.gov | ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov |

| ImageJ | Version 2.9.0/1.54f | |

| Topscan Lite version | CleverSys Inc. | |

| Mousemove | Samson et al., 201567 | |

| Odyssey® CLx analysis software | Li-Cor | |

| Avisoft SASLab Bioacoustics software | avisoft.com | |

| Actual HCA home cage analysis software | Boca Scientific | |

| Profusion 4 | Compumedics | |

| Assyst Seizure detection software | Assyst | |

| CLIJ2 | Haase et al.,202068 | |

| Ilastik | Berg et al., 201969 | |

| Trackmate | Ershov et al., 202270 | V7.11.1 |

| Python | Python Software Foundation | V3.9 |

| Other | ||

| Tissue-Tek O.C.T compound | ProSciTech | IA018 |

| Dako fluorescence mounting medium | Agilent Dako | CS703 |

| SpectrumTM Dialysis tubing 3.5 kD MWCO | Fisher Scientific | 132724 |

| 5′-CCTCTAA GGTTTGCTTACGA-3′ | This study | Eco R1 control cRNA (CRISPR/Cas9 cRNA) |

| 5′-CAAAGC GCGGTCTATCTAAG-3′ | This study | p.Lys1258Glyfs∗13 cRNA (CRISPR/Cas9 cRNA) |

| 5′-ACCCATG GAGCCTGACGAGC-3′ | This study | p.Val1287Glufs∗46 cRNA (CRISPR/Cas9 cRNA) |

Experimental model details

Human cells

HEK293T cells were used to generate and model human Genitopatellar syndrome mutations in human cells in vitro.

Mice

Mouse husbandry and experiments were conducted in accordance with the Australia Code of Practice for the Care and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes and with the approval of the Walter and Eliza Hall Animal Ethics Committee (2018.043 and 2021.058) or the approval of the Alfred Research Alliance Animal Ethics Committee (E/1865/2019/M). Mice were housed with a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle. Noon of the day of an observed vaginal copulation plug was defined as embryonic day 0.5 (E0.5). Mice were used in order of recovery or birth, including male and female mice occurring in their recovery or birth order. Behavioral tests on were performed at 8–12 weeks of age on male and female animals. Where differences in sexes were observed these are specifically stated, e.g., body weight, frequency of aggression observed. In other cases, no differences were observed between sexes. Kindling was performed on male animals at 8 months of age. Developmental milestones and ultrasonic vocalization assessment were performed on mice from P1-21.

Kat6b overexpression construct

Kat6b overexpressing mice (Tg(Kat6b)), were generated using bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) pBACe3.6 clone RP23-360F23, containing the wild-type Kat6b sequence as well as 21 kb and 42 kb upstream and downstream of the coding exons, respectively. We have previously shown that a BAC transgene, lacking the 3′ end of the Kat6b gene, was able to recapitulate the Kat6b expression pattern.11 Seven copies of the pBACe3.6 transcript inserted into the mouse genome. Mice were maintained on a FVB x BALB/c hybrid genetic background, as Tg(Kat6b) mice were not viable on inbred backgrounds. Mice were genotyped using primers amplifying the sacB gene sequence in the BAC backbone (key resources table).

Method details

Human cell culture

HEK293T cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco, 11965092) containing 5% (v/v) FCS and 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Gibco, 15140122). Cells were grown at 37°C in 10% CO2.

Genome editing and sequencing of human cells

Custom guide RNAs and homology-directed repair (HDR) donor templates were designed using the Alt-R CRISPR HDR Design Tool (IDT https://sg.idtdna.com/pages/tools/alt-r-crispr-hdr-design-tool). As a positive control, HEK293T cells that retained the wild-type KAT6B sequence but carried a silent mutation including a novel EcoR1 restriction enzyme cut site in the safe harbor locus AAVS1 were also generated. Guide RNAs and HDR template sequences can be found in the key resources table. Genome editing was performed using a ribonucleoprotein CRISPR/Cas 9 editing approach (Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 system; IDT), where reagents were electroporated into HEK293T cells a using a kit (SF Cell Line 4D-Nucleofector X Kit S; Lonza, V4XC-2032). Editing efficiency was determined on bulk-edited HEK293T cell populations by medium-throughput DNA sequencing (MiSeq; Illumina) after PCR amplification of the Cas9-targeted region and secondary PCR using overhang sequences (key resources table). MiSeq sequencing results are available in Table S1. Multiple single cell clones for each mutation were then established by limited dilution and re-sequenced.

RT-qPCR of human cells

RNA was extracted from HEK293T cell clones using an RNA extraction kit (RNeasy Mini Kit; 74104; Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instructions, including the optional DNase digestion step. 1 μg RNA, as determined using a spectrophotometer (DS-11 series; Denovix), was used to generate cDNA using a cDNA synthesis kit (SuperScript IV First-Strand Synthesis System; 18091050; Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. 2 μL cDNA per sample was used for PCR amplification with sequence-specific primers (key resources table) in technical triplicates on a PCR machine for quantitative amplification (QuantStudio qPCR; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and the following cycle conditions: Hold stage: 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min; 40x cycles: 90°C for 15 s, 60°C for 60 s, 72°C for 15 s; Final extension and Melt Curve: 72°C for 2 min, 95°C for 60 s, Cool. GAPDH was used as a housekeeping control.

Behavioral testing of mice

Behavioral tests were performed during the light phase of the light/dark cycle, except the home-cage observations, which spanned four light/dark cycles. Light levels were standardized at 100 lux using a luminometer (Lutron LM-81LX. S041136). A low level (∼60 dB) white noise sound was played throughout the testing period. The temperature maintained at 22°C. Tests were recorded using an HD WedCam C615 (Logitech; Lausanne, Switzerland). Mice were habituated to the operator prior to testing and to the testing room for 30 min prior to testing, as described.71 Behavioral apparatuses were cleaned using 80% ethanol before and after testing and between mice. Mice were returned to their home cage following testing. Only one test was performed per day.

Developmental behavioral milestones

Early postnatal behavioral and physical milestones were assessed as described27 from postnatal day 1–21 (P1 to P21).

Assessment of maternal separation-induced ultrasonic vocalization (USV)

Ultrasonic vocalizations were recorded in pups following separation from the mother at P4, P8 and P12. Vocalizations were recorded over a 3 min period in a sound-attenuated chamber as described.72

Rotarod test

Motor coordination, balance and strength were assessed using a rotating rod (Rotamex-5, Columbus Instruments) as described.73 Mice were lowered onto a 3 cm diameter rotating rod. The rotation speed in revolutions per minute (rpm) was increased between sessions from 12, 16, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40 to 45 rpm with a 1 min rest between sessions. Two trials were performed on the same day, separated by a 1 h break. The latency to fall at each rpm was assessed, with a 1 s penalty given if mice did not walk in time with the rod but instead gripped the rod and rotated with it (cartwheel).

Hanging mesh

Mice were lowered onto a square wire mesh. Once mice had gripped the mesh with all four paws, they were inverted ∼30 cm above a padded surface and allowed to hang until falling. The latency to fall was recorded.

Grip strength test

Forelimb grip strength (g) was assessed using a grip strength meter (Bioseb, BIO-GS3). Mice were suspended by the tail and lowered toward the grip-meter bar. Once mice had gripped the bar with both forepaws they were gently pulled away. The maximum force used by the mouse before releasing the bar was recorded. Mice underwent 5 trials on the same day, with a 1 min rest between trials. The best 3 of these trials per mouse were used to compare grip strength between mice.

Visual cliff test

24 h prior to visual cliff testing,74 mice had their whiskers trimmed to less than 5 mm. Mice were placed into a clear, square Perspex box with ½ its length extended beyond the edge of a table. A red and white checkered pattern was placed under the Perspex and extended to the floor to give the impression of a vertical drop (cliff). Mice were allowed to explore for a 5 min testing period, and the proportion of time spent on the visually shallow side vs. over the visual cliff was assessed.

Home cage tracking and analysis

One week prior to testing, mice were anesthetized, and an ISO RFID (BIO12.B.04V2 PLT, Biomark) identity microchip was injected subcutaneously in the region of the lower abdomen. Remaining in their home cage, mice were placed into a home cage analysis system (ActualHCA, BocaScientific). Movements were recorded for a 96-h period. Data was analyzed using a home-cage tracking software (ActualHCA, BocaScientific), assessing movement parameters at 15 min intervals.

Large open field test

The open field test was performed as described.27,67 Mice were placed in a circular 90 cm diameter arena with 0.4 m high black corrugated walls and surrounded by a white opaque curtain. Light intensity was 50 lux in the center of the arena. Mouse ambulation was recorded for a 20 min period and movements tracked and analyzed using mouse tracking software (MouseMove67).

Elevated O maze and elevated plus maze

The elevated O maze was comprised a 10 cm wide annular platform 60 cm above the floor, with two opposing open regions and two opposing enclosed regions. The enclosed regions had 20 cm high opaque walls. The elevated plus maze75 was comprised of two open arms (30 × 5 cm) and two enclosed arms (30 × 5 cm). The enclosed regions had 20 cm high opaque walls. The elevated plus maze was elevated 40 cm from the ground. In both mazes, mice were placed at the threshold between open and enclosed arms and allowed to freely explore for 5 min. The time spent within open and closed regions was assessed.

Novel object recognition test

The novel object recognition test was performed as described76 with minor modifications as described.67 The preference for the novel vs. the familiar object was assessed by calculating the discrimination index, defined as [time spent exploring the novel object minus the time spent exploring the familiar object] divided by the total exploration time.77

Y maze for working memory and spatial memory

The Y maze78 comprised three arms, 38 cm × 7 cm x 12 cm, positioned at 120° to each other. Two test arms (A and B) contained guillotine doors at the stem to block entry if required. A third arm (C) was designated the home arm and contained a 10 cm start area where mice were placed at the commencement of each test. Two tests were carried out using the Y maze.

In the working memory test mice were allowed to freely explore all three arms of the maze for a 5 min period and the sequence of entries into each arm was assessed. An alternation was defined when a mouse entered each of the three arms within three consecutive arm entries.

In the Y maze test for spatial recognition memory, visual cues were placed at the end of each arm. Mice were first placed into the Y maze with either arm A or arm B blocked off and were allowed to explore the remaining two arms for 10 min. Mice were returned to their home cage for 1 h. Upon being placed into the Y maze for the second time all arms were open. The previously blocked off arm was designated the novel arm. Mice were allowed to explore for 5 min. The proportion of time spent within each arm and discrimination index (as described under novel object recognition test) for the novel arm were assessed.

Tube-dominance test

In the tube-dominance test79 male mice were placed face to face at the ends of a 15 cm long clear acrylic cylindrical tube of 3 cm internal diameter, whereupon the mice typically approach each other. A mouse was considered to have ‘won’ when its opponent had backed out of the tube and had all four paws outside the tube. The proportion of wins across mouse pairings was assessed for all mice and compared to random levels, 0.5 (winning in half of all tests) using a one-sample t test.

Three-chamber social test

The three-chamber social test was performed as described,80 with minor modifications. The test was carried out in three sessions. Mice were habituated to the three-chamber arena for 10 min and returned to their home cage for 1 h. In session 1, mice entered the chamber with an empty small cage in one of the outer chambers and a small cage with a mouse in the other chamber. This mouse was matched in genetic background, sex, and approximate weight to the test mouse. The test mouse was allowed to freely explore for 5 min. Mice were returned to their home cage for 1 h. In session 2, test mice were placed into the chamber with one cage containing the same mouse from session 1, now a familiar mouse, and a previously unseen mouse (novel mouse). Test mice were allowed to freely explore for 5 min. All mice were returned to their home cage. In session 3, 24 h later, test mice were placed into the chamber with one cage containing the same mouse from session 1 and 2 (familiar mouse) and a new novel mouse. Test mice were allowed to freely explore for 5 min. In all sessions, the proportion of time test mice spent investigating each cage and the discrimination index (as described under novel object recognition test) for the mouse vs. empty cage (session 1) or novel vs. familiar mouse (sessions 2 and 3) were assessed.

EEG monitoring and kindling study

EEG monitoring and Kindling was performed as described.81,82 Briefly, under general anesthesia, bipolar stimulating electrodes were surgically implanted into the left basolateral amygdala of test mice. After recovery from surgery, mice were monitored for a baseline assessment. After the baseline assessment, mice received twice daily electrical stimulations (1 s train of 1 msec biphasic square waves pulses at 60 Hz frequency) for 15 days (30 total stimulations). After discharge threshold current was established on the first stimulation and used throughout as the current stimulus. Each seizure resulting from electrical stimulation was graded according to the Racine scale, and duration also noted from review of the associated EEG recording. Following completion of kindling, mice were monitored for an additional 20 days by video-EEG using Profusion 4 software (Compumedics, Australia). All video-EEG recordings were coded, and screened for seizures, spike, and wave discharges (SWD) and inter-ictal spikes using Assyst,83 an automated seizure detection software (Assyst, Australia).

Mouse cell culture

Neural stem and progenitor cells (NSPC) culture

NSPCs were isolated and cultured as described.84,85,86 Secondary neurosphere formation was performed as described.12 NSPC differentiation and staining were performed as described.11,12,87

E16.5 cortical neuron culture

E16.5 fetal cortices were dissected and digested in 200 μL trypsin/EDTA (Sigma, 10006132) for 10 min at 37°C. Excess trypsin was removed and replaced with 1 mL cortical neuron medium (DMEM/F12 (Gibco, 12500-062), 5 mM HEPES (Sigma, H-4034), 13.4 mM NaHCO3 (Sigma, G-7021), 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco, 15140-122), 25 μg/mL Insulin (Sigma, I-6634), 60 μM putrescine dihydrochloride (Sigma, P-5780), 100 μg/mL apo-transferrin (Sigma, T-2252), 30 nM selenium sodium salt (Sigma S-9133), 20 nM progesterone (Sigma, P-6149), 0.2% BSA (Sigma, A-3311) and 1% FCS). Tissue was gently triturated and passed through a 100 μm cell sieve (Corning, 431751). The cell pellet was resuspended in 1 mL cortical neuron medium and 10,000 cells/cm2, determined using an automated cell counter (Countess; Invitrogen), were plated onto chamber slides (Sigma, C6932) pre-coated with 0.1 mg/mL poly-D-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich, P4832) for 2 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were grown at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 5 days to allow neurite outgrowth.

Histology

For histological sectioning of adult brains, mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation. The cardiovascular system was flushed with PBS. The mice were perfusion-fixed using 4% (w/v) PFA (Sigma- Aldrich, P6148) in PBS. Brains were dissected and post-fixed by submersion in 2–4% PFA for 24 h at 4°C on a roller.

Cresyl violet staining of adult brains

Fixed brains were paraffin embedded and 7 μm coronal sections cut and stained with cresyl violet. Sections were imaged on a microscope (Axioplan 2; Zeiss). Cortex area, cortex length and cell density were assessed using an image analysis software (ImageJ2 version 2.9.0/1.54f). Volumetric analyses were performed by the Cavalieri method, as described in Coggeshall, 1992.88

Golgi-Cox silver staining

Adult brains were dissected and stained using a staining kit (FD Rapid Golgi Stain Kit; PK401; FD Neuro Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. 100 μm sections were cut on a vibratome (VT 1000S, Leica) and brain sections were imaged, and individual neurons analyzed using an image analysis software (Neurolucida; MBF Bioscience).

BrdU administration

Mice were intraperitoneally injected every 12 h with BrdU (Sigma-Aldrich, B5002) at a dose of 100 μg/g bodyweight, for 12 days, followed by 14 days without treatment. Perfusion-fixed brains were paraffin embedded, and 10 μm coronal serial sections were cut. Sections were stained for BrdU as described.12 Elongated cells, apoptotic cells or cells with very weak staining were not included.

Immunohistochemistry

Antibodies used for immunohistochemistry are listed in the key resources table. For CHAT, TPH2, TH, vGLUT1 and vGLUT2 staining, perfusion-fixed brains were paraffin embedded, and 7 μm coronal sections were cut. Sections were cleared of paraffin (2x HistoClear (ProSciTech), 5 min, 2 min in 100, 96, 90, 70 and 50% ethanol and 5 min in H2O). Antigen retrieval and antibody staining were automated (Dako Omnis; Agilent). Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin.

Immunofluorescent staining in adult and embryonic cortex sections

Antibodies used for immunofluorescence are listed in the key resources table.

For somatostatin, parvalbumin, calretinin and calbindin staining, perfusion-fixed brains were embedded in 3% low melting point agarose (Biorad, 1613112). 150 μm coronal serial sections were cut on a vibratome (VT 1000S; Leica), and fresh sections were stained in 24-well plates. Sections were blocked for 1 h at RT in 10% normal donkey serum (NDS) + 1% Triton X-100 in PBS and incubated with primary antibodies in 2% NDS +0.3% Triton X-100 for 60 h at 4°C on an orbital shaker. Sections were washed in PBS and incubated with secondary antibodies in 2% NDS and 0.3% Triton X-100 for 24 h at 4°C on an orbital shaker. Sections were washed in PBS and mounted onto charged slides (SuperFrost Plus; 22-037-246; Fisher Scientific) in fluorescence mounting medium (GM304; Dako). Three-dimensional image stacks were acquired using a confocal microscope (LSM 880; Zeiss) with a 25x/0.8 multi-immersion objective lens. Linear spectral deconvolution was performed using reference spectra acquired from single stained controls.

For NeuN, S100β and OLIG2 staining, perfusion-fixed adult brains were infiltrated for 24 h with 15% sucrose, then 30% sucrose and embedded in cryostat embedding matrix (O.C.T.; IA018; TissueTek). For cortical layer (TBR1, CTIP2, SATB2), ventricular (PAX6) and subventricular zone (TBR2) staining of E18.5 cortices, whole E18.5 heads without skin were dissected and embedded unfixed (O.C.T.; IA018; TissueTek). 10–20 μm sections were cut on a cryostat (Cryostat Microm HM550, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and mounted onto charged slides (SuperFrost Plus; 22-037-246; Fisher Scientific). E18.5 sections were fixed at this stage. Sections were blocked in 10% FCS +1% Triton X-100 in MQ-H2O for 1 h at RT in a humidified chamber and stained O/N at 4°C in a humidified chamber with primary antibodies in 10% FCS +0.3% Triton X-100. Sections were washed in PBS, incubated for 1 h at RT in a humidified chamber with secondary antibodies and washed in PBS mounted in mounting medium (Dako, GM304). Sections were imaged using a fluorescent microscope (Axioplan 2; Zeiss).

For IBA1 staining, mice were euthanized in CO2 and perfused with PBS followed by 4% (w/v) PFA fixative. Brains were dissected and infiltrated for 24 h with 15% (w/v) sucrose (Sigma, S0389) O/N at 4°C, followed by 30% (w/v) sucrose O/N at 4°C on a roller and embedded in cryostat embedding matrix (O.C.T; IA018; TissueTek). 20 μm sections were cut on an H550 Cryostat and mounted onto charged slides (SuperFrostPlus; 22-037-246; Fisher Scientific). Sections were blocked and permeabilized in 10% FCS +1% Triton X-100 in MQH2O for 1 h at RT in a humidity chamber and stained O/N at 4°C in a humidity chamber with anti-IBA1 antibody at 1:500 in 10% FCS. Sections were washed in PBS and incubated for 1 h at RT with secondary antibody at 1:400 in 10% FCS, washed in PBS, incubated for 5 min at RT with DAPI (1 μg/mL), washed in PBS and mounted in fluorescent mounting medium (Dako, GM304). Sections were imaged using a Zeiss fluorescent microscope.

Quantification of epifluorescence and immunostaining