Abstract

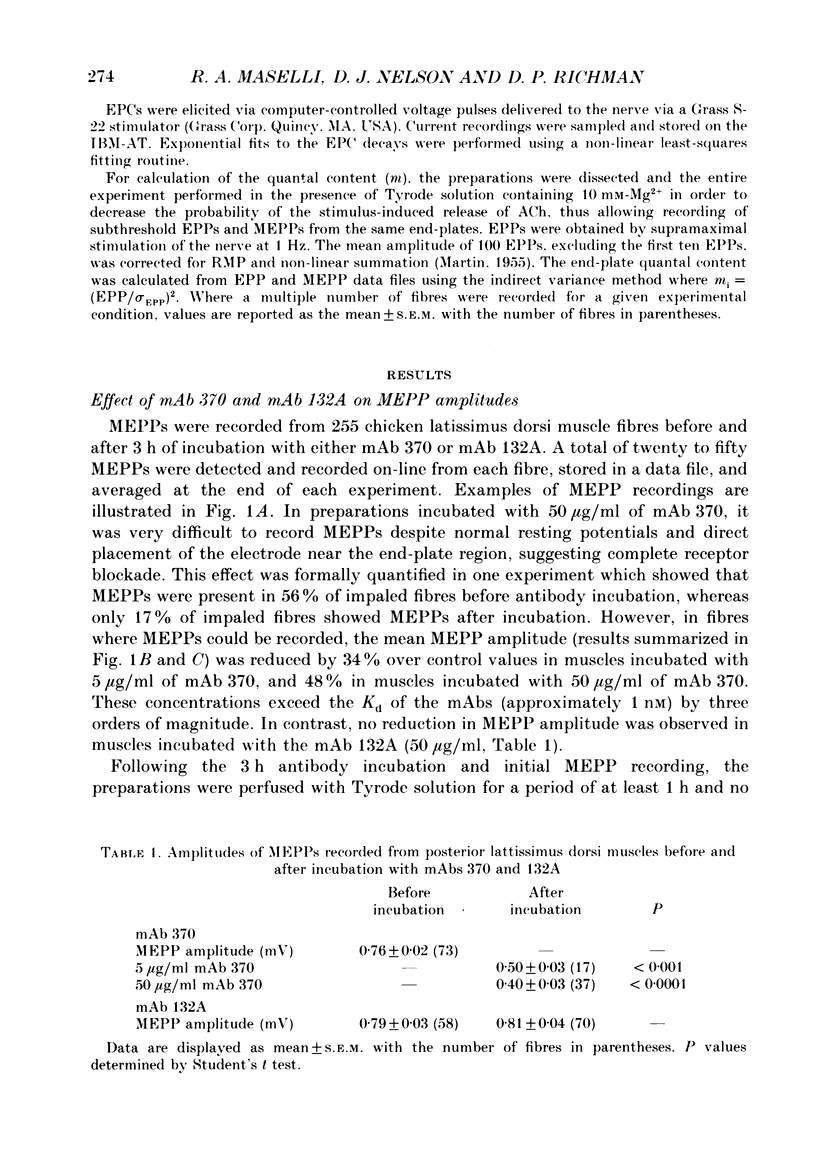

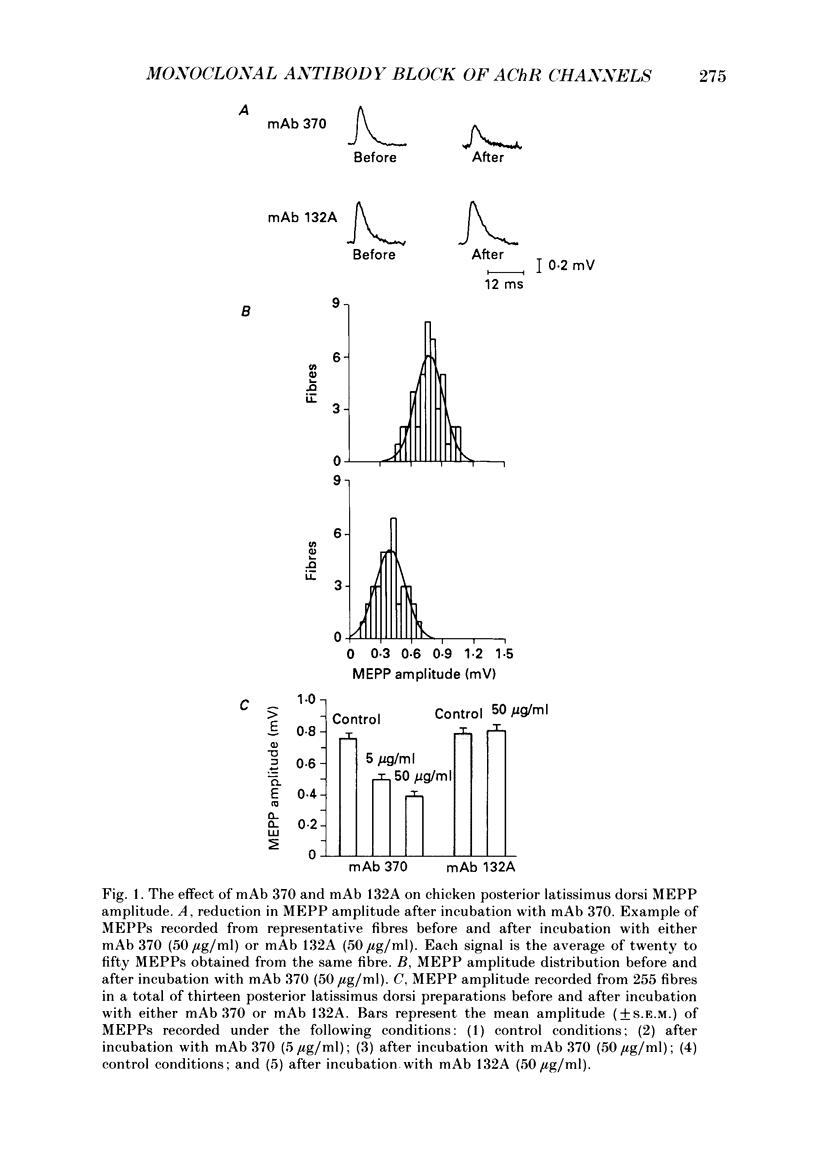

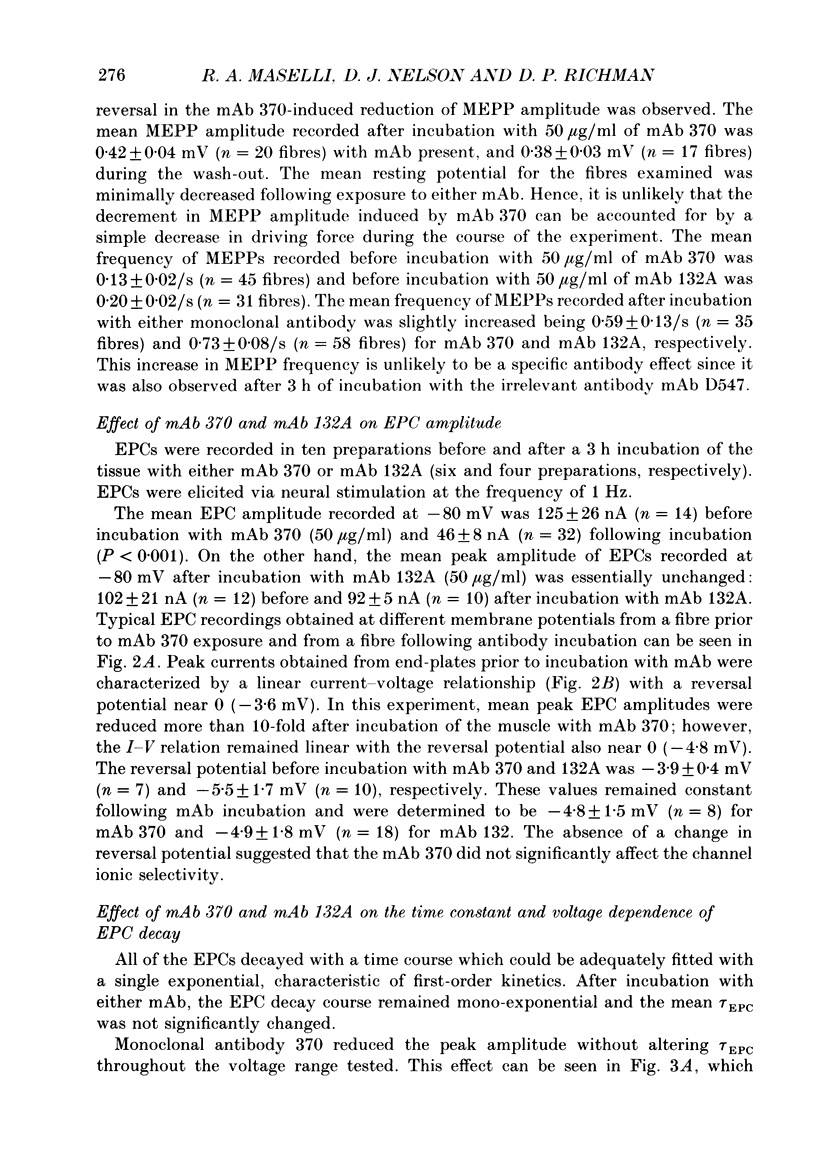

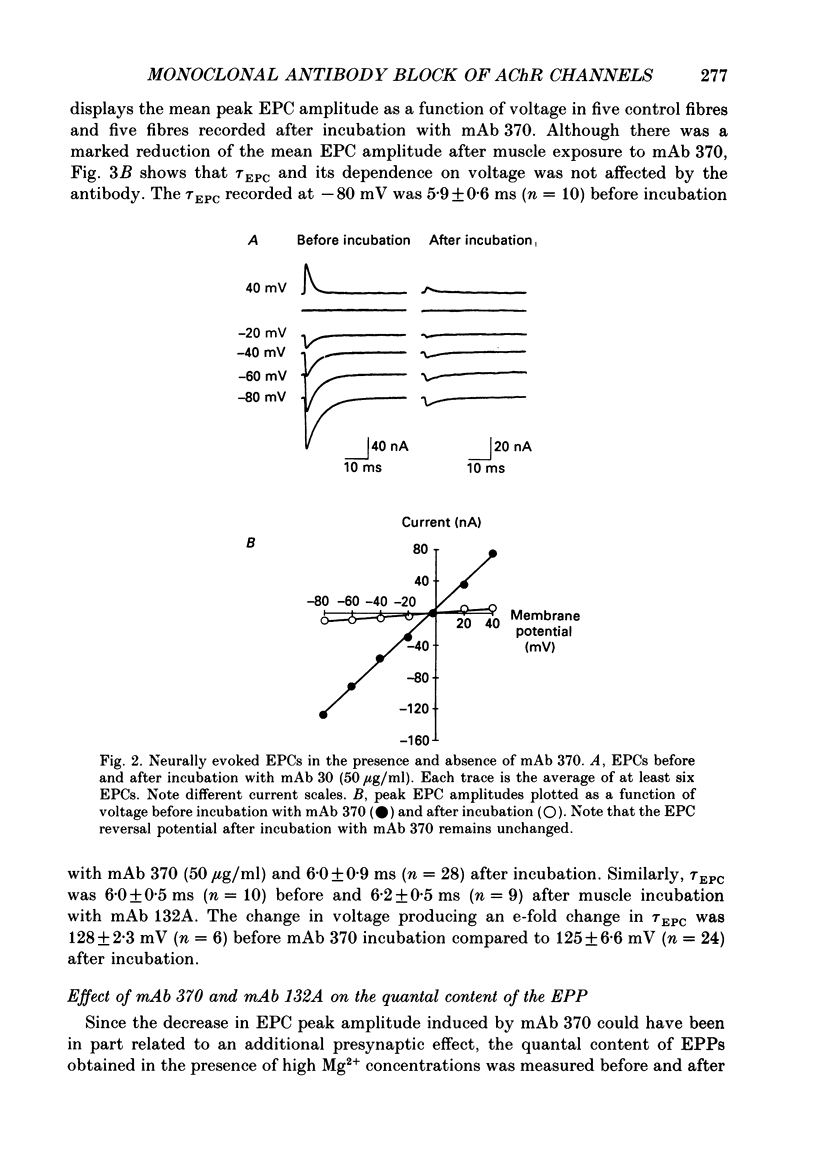

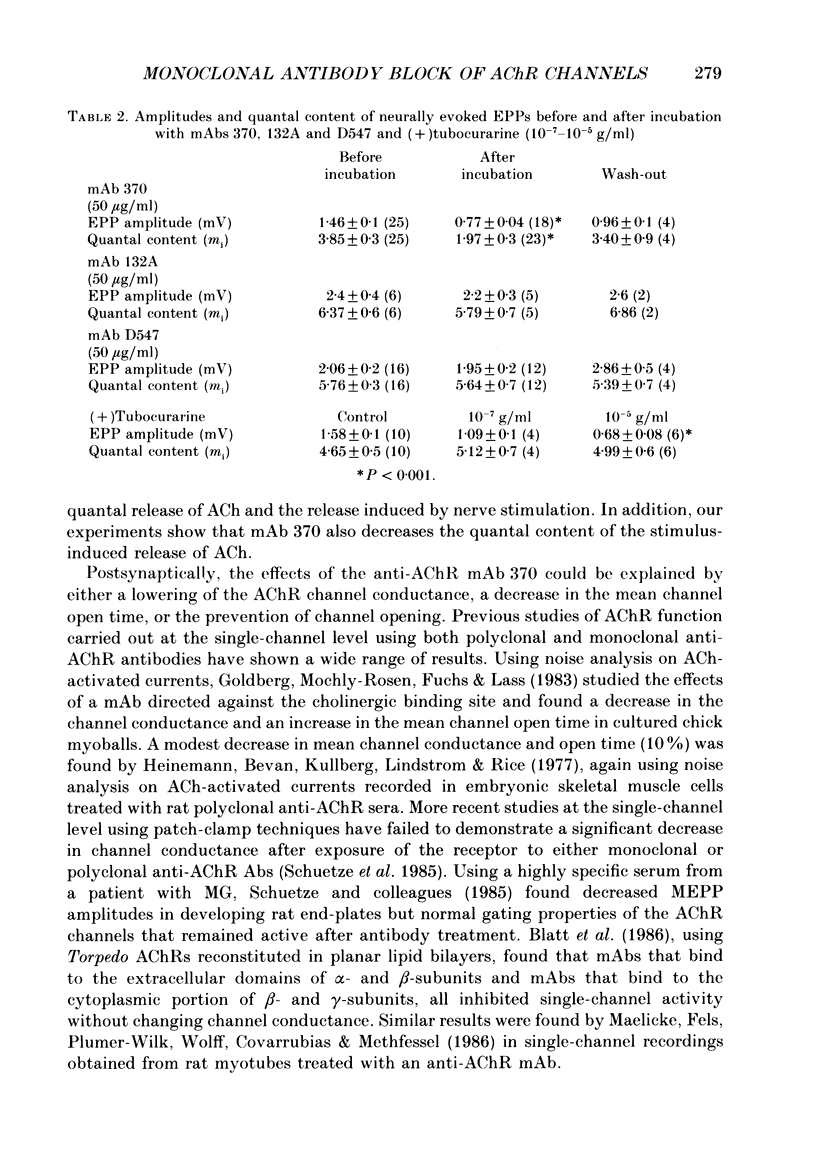

1. The effects of anti-acetylcholine receptor (AChR) monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) 370 and 132A on miniature end-plate potentials (MEPPs) and end-plate currents (EPCs) in the posterior latissimus dorsi muscle of adult chickens were investigated. 2. After incubation of the electrophysiological preparation with mAb 370 (5-50 micrograms/ml), which blocks both agonist (carbamylcholine) and alpha-bungarotoxin (alpha-BTX) binding and induces a hyperacute form of experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis (EAMG), MEPP and EPC amplitudes were irreversibly reduced. 3. This effect was not associated with any significant change in the time constant describing EPC decay (tau EPC), current reversal potential, or the voltage dependence of tau EPC. The tau EPC at -80 mV was 5.9 +/- 0.6 ms before incubation with mAb 370 (50 micrograms/ml) and 6.0 +/- 0.9 ms afterwards. Current reversal potential was -3.9 +/- 0.4 mV before mAb incubation and -4.8 +/- 1.5 mV afterwards. The change in membrane potential required to produce an e-fold change in tau EPC was 128 +/- 2.3 mV before antibody incubation compared to 125 +/- 6.6 mV after incubation. 4. A second anti-AChR mAb, 132A (50 micrograms/ml), which is capable of inducing the classically described form of EAMG without blocking agonist or alpha-BTX binding, or inducing hyperacute EAMG, produced no significant change in MEPP amplitude, EPC amplitude, tau EPC or EPC reversal potentials. 5. The mAb 370 (50 micrograms/ml) induced a partially reversible decrease of the quantal content of the neurally evoked end-plate potential (EPP). This effect was not observed with mAb 132A, (+)tubocurarine (10(-7)-10(-5) g/ml) or an irrelevant anti-oestrogen receptor mAb. 6. These data suggest that the rapid onset of weakness observed in chicken hatchlings after the injection of mAb 370 (Gomez & Richman, 1983) can be attributed to a combined effect of a block of acetylcholine (ACh)-induced ion channel activity in the postsynaptic membrane and a reduction of the neurally evoked release of acetylcholine from the nerve terminal.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Alemà S., Cull-Candy S. G., Miledi R., Trautmann A. Properties of end-plate channels in rats immunized against acetylcholine receptors. J Physiol. 1981 Feb;311:251–266. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevan S., Kullberg R. W., Heinemann S. F. Human myasthenic sera reduce acetylcholine sensitivity of human muscle cells in tissue culture. Nature. 1977 May 19;267(5608):263–265. doi: 10.1038/267263a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatt Y., Montal M. S., Lindstrom J. M., Montal M. Monoclonal antibodies specific to the beta and gamma subunits of the Torpedo acetylcholine receptor inhibit single-channel activity. J Neurosci. 1986 Feb;6(2):481–486. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-02-00481.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulter J., Connolly J., Deneris E., Goldman D., Heinemann S., Patrick J. Functional expression of two neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors from cDNA clones identifies a gene family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987 Nov;84(21):7763–7767. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.21.7763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase B. A., Holliday J., Reese J. H., Chun L. L., Hawrot E. Monoclonal antibodies with defined specificities for Torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor cross-react with Drosophila neural tissue. Neuroscience. 1987 Jun;21(3):959–976. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(87)90051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun D., Large W. A., Rang H. P. An analysis of the action of a false transmitter at the neuromuscular junction. J Physiol. 1977 Apr;266(2):361–395. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp011772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cull-Candy S. G., Miledi R., Trautmann A. End-plate currents and acetylcholine noise at normal and myasthenic human end-plates. J Physiol. 1979 Feb;287:247–265. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1979.sp012657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEL CASTILLO J., KATZ B. The effect of magnesium on the activity of motor nerve endings. J Physiol. 1954 Jun 28;124(3):553–559. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1954.sp005128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutch A. Y., Holliday J., Roth R. H., Chun L. L., Hawrot E. Immunohistochemical localization of a neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in mammalian brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987 Dec;84(23):8697–8701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.23.8697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolly J. O., Gwilt M., Lacey G., Newsom-Davis J., Vincent A., Whiting P., Wray D. W. Action of antibodies directed against the acetylcholine receptor on channel function at mouse and rat motor end-plates. J Physiol. 1988 May;399:577–589. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly D., Mihovilovic M., Gonzalez-Ros J. M., Ferragut J. A., Richman D., Martinez-Carrion M. A noncholinergic site-directed monoclonal antibody can impair agonist-induced ion flux in Torpedo californica acetylcholine receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984 Dec;81(24):7999–8003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.24.7999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drachman D. B., Adams R. N., Josifek L. F., Self S. G. Functional activities of autoantibodies to acetylcholine receptors and the clinical severity of myasthenia gravis. N Engl J Med. 1982 Sep 23;307(13):769–775. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198209233071301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel A. G., Sakakibara H., Sahashi K., Lindstrom J. M., Lambert E. H., Lennon V. A. Passively transferred experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis. Sequential and quantitative study of the motor end-plate fine structure and ultrastructural localization of immune complexes (IgG and C3), and of the acetylcholine receptor. Neurology. 1979 Feb;29(2):179–188. doi: 10.1212/wnl.29.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GINSBORG B. L. Some properties of avian skeletal muscle fibres with multiple neuromuscular junctions. J Physiol. 1960 Dec;154:581–598. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1960.sp006597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage P. W., Van Helden D. Effects of permeant monovalent cations on end-plate channels. J Physiol. 1979 Mar;288:509–528. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg G., Mochly-Rosen D., Fuchs S., Lass Y. Monoclonal antibodies modify acetylcholine-induced ionic channel properties in cultured chick myoballs. J Membr Biol. 1983;76(2):123–128. doi: 10.1007/BF02000612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez C. M., Richman D. P. Anti-acetylcholine receptor antibodies directed against the alpha-bungarotoxin binding site induce a unique form of experimental myasthenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983 Jul;80(13):4089–4093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.13.4089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez C. M., Richman D. P., Burres S. A., Arnason B. G., Berman P. W., Fitch F. W. Monoclonal hybridoma anti-acetylcholine receptor antibodies: antibody specificity and effect of passive transfer. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1981;377:97–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1981.tb33726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez C. M., Richman D. P. Chronic experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis induced by monoclonal antibody to acetylcholine receptor: biochemical and electrophysiologic criteria. J Immunol. 1987 Jul 1;139(1):73–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halvorsen S. W., Berg D. K. Affinity labeling of neuronal acetylcholine receptor subunits with an alpha-neurotoxin that blocks receptor function. J Neurosci. 1987 Aug;7(8):2547–2555. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann S., Bevan S., Kullberg R., Lindstrom J., Rice J. Modulation of acetylcholine receptor by antibody against the receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977 Jul;74(7):3090–3094. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.7.3090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera A. A. Polyneuronal innervation and quantal transmitter release in formamide-treated frog sartorius muscles. J Physiol. 1984 Oct;355:267–280. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohlfeld R., Sterz R., Kalies I., Peper K., Wekerle H. Neuromuscular Transmission in experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis (EAMG). Quantitative ionophoresis and current fluctuation analysis at normal and myasthenic rat end-plates. Pflugers Arch. 1981 May;390(2):156–160. doi: 10.1007/BF00590199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz B., Miledi R. A re-examination of curare action at the motor endplate. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1978 Dec 4;203(1151):119–133. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1978.0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz B., Miledi R. The binding of acetylcholine to receptors and its removal from the synaptic cleft. J Physiol. 1973 Jun;231(3):549–574. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1973.sp010248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebeda F. J., Albuquerque E. X. Membrane cable properties of normal and dystrophic chicken muscle fibers. Exp Neurol. 1975 Jun;47(3):544–557. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(75)90087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennon V. A., Lindstrom J. M., Seybold M. E. Experimental autoimmune myasthenia: A model of myasthenia gravis in rats and guinea pigs. J Exp Med. 1975 Jun 1;141(6):1365–1375. doi: 10.1084/jem.141.6.1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennon V. A., Seybold M. E., Lindstrom J. M., Cochrane C., Ulevitch R. Role of complement in the pathogenesis of experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis. J Exp Med. 1978 Apr 1;147(4):973–983. doi: 10.1084/jem.147.4.973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom J. M., Einarson B. L., Lennon V. A., Seybold M. E. Pathological mechanisms in experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis. I. Immunogenicity of syngeneic muscle acetylcholine receptor and quantitative extraction of receptor and antibody-receptor complexes from muscles of rats with experimental automimmune myasthenia gravis. J Exp Med. 1976 Sep 1;144(3):726–738. doi: 10.1084/jem.144.3.726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukas R. J. Interactions of anti-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antibodies at alpha-bungarotoxin binding sites across species and tissues. Brain Res. 1986 Nov;387(2):119–125. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(86)90003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARTIN A. R. A further study of the statistical composition on the end-plate potential. J Physiol. 1955 Oct 28;130(1):114–122. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1955.sp005397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magleby K. L., Stevens C. F. A quantitative description of end-plate currents. J Physiol. 1972 May;223(1):173–197. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1972.sp009840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magleby K. L., Stevens C. F. The effect of voltage on the time course of end-plate currents. J Physiol. 1972 May;223(1):151–171. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1972.sp009839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magleby K. L., Terrar D. A. Factors affecting the time course of decay of end-plate currents: a possible cooperative action of acetylcholine on receptors at the frog neuromuscular junction. J Physiol. 1975 Jan;244(2):467–495. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1975.sp010808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihovilovic M., Richman D. P. Modification of alpha-bungarotoxin and cholinergic ligand-binding properties of Torpedo acetylcholine receptor by a monoclonal anti-acetylcholine receptor antibody. J Biol Chem. 1984 Dec 25;259(24):15051–15059. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihovilovic M., Richman D. P. Monoclonal antibodies as probes of the alpha-bungarotoxin and cholinergic binding regions of the acetylcholine receptor. J Biol Chem. 1987 Apr 15;262(11):4978–4986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochly-Rosen D., Fuchs S. Monoclonal anti-acetylcholine-receptor antibodies directed against the cholinergic binding site. Biochemistry. 1981 Sep 29;20(20):5920–5924. doi: 10.1021/bi00523a041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick J., Lindstrom J. Autoimmune response to acetylcholine receptor. Science. 1973 May 25;180(4088):871–872. doi: 10.1126/science.180.4088.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahashi K., Engel A. G., Linstrom J. M., Lambert E. H., Lennon V. A. Ultrastructural localization of immune complexes (IgG and C3) at the end-plate in experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1978 Mar-Apr;37(2):212–223. doi: 10.1097/00005072-197803000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuetze S. M. The acetylcholine channel open time in chick muscle is not decreased following innervation. J Physiol. 1980 Jun;303:111–124. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1980.sp013274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuetze S. M., Vicini S., Hall Z. W. Myasthenic serum selectively blocks acetylcholine receptors with long channel open times at developing rat endplates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 Apr;82(8):2533–2537. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.8.2533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzartos S., Hochschwender S., Vasquez P., Lindstrom J. Passive transfer of experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis by monoclonal antibodies to the main immunogenic region of the acetylcholine receptor. J Neuroimmunol. 1987 Jun;15(2):185–194. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(87)90092-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watters D., Maelicke A. Organization of ligand binding sites at the acetylcholine receptor: a study with monoclonal antibodies. Biochemistry. 1983 Apr 12;22(8):1811–1819. doi: 10.1021/bi00277a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]