Abstract

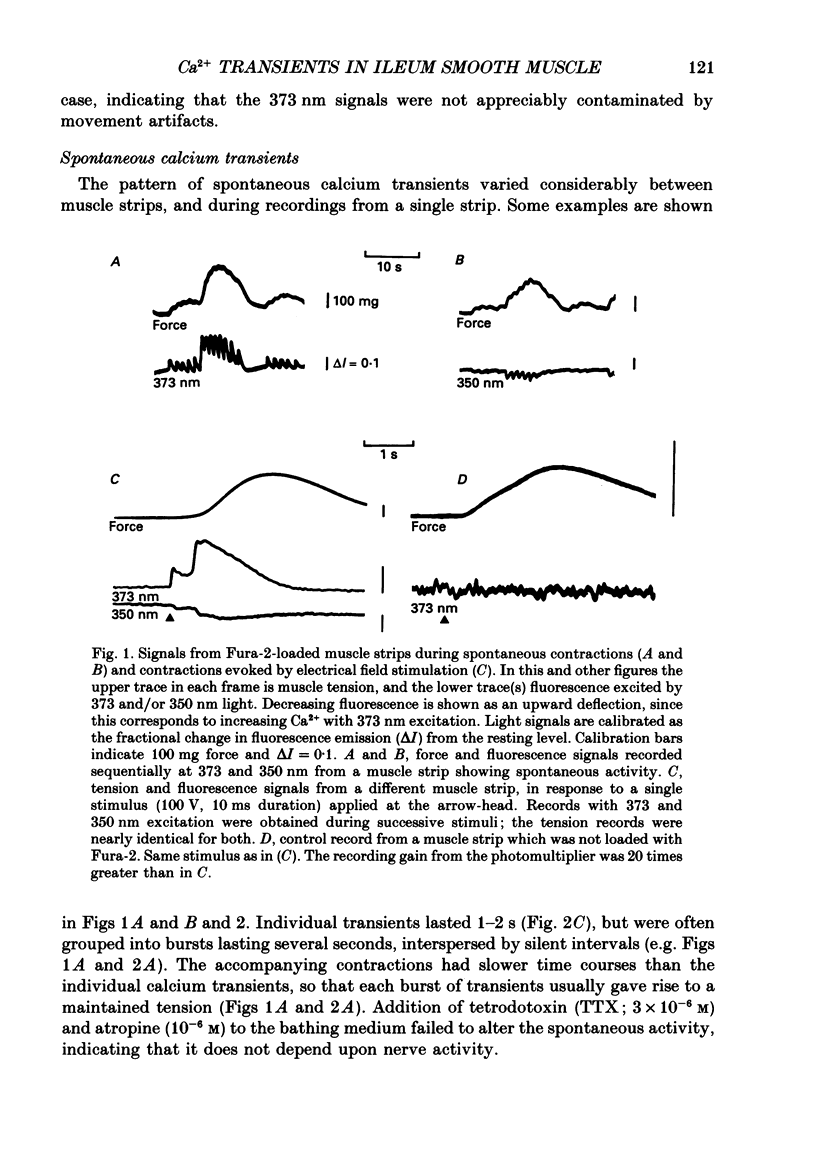

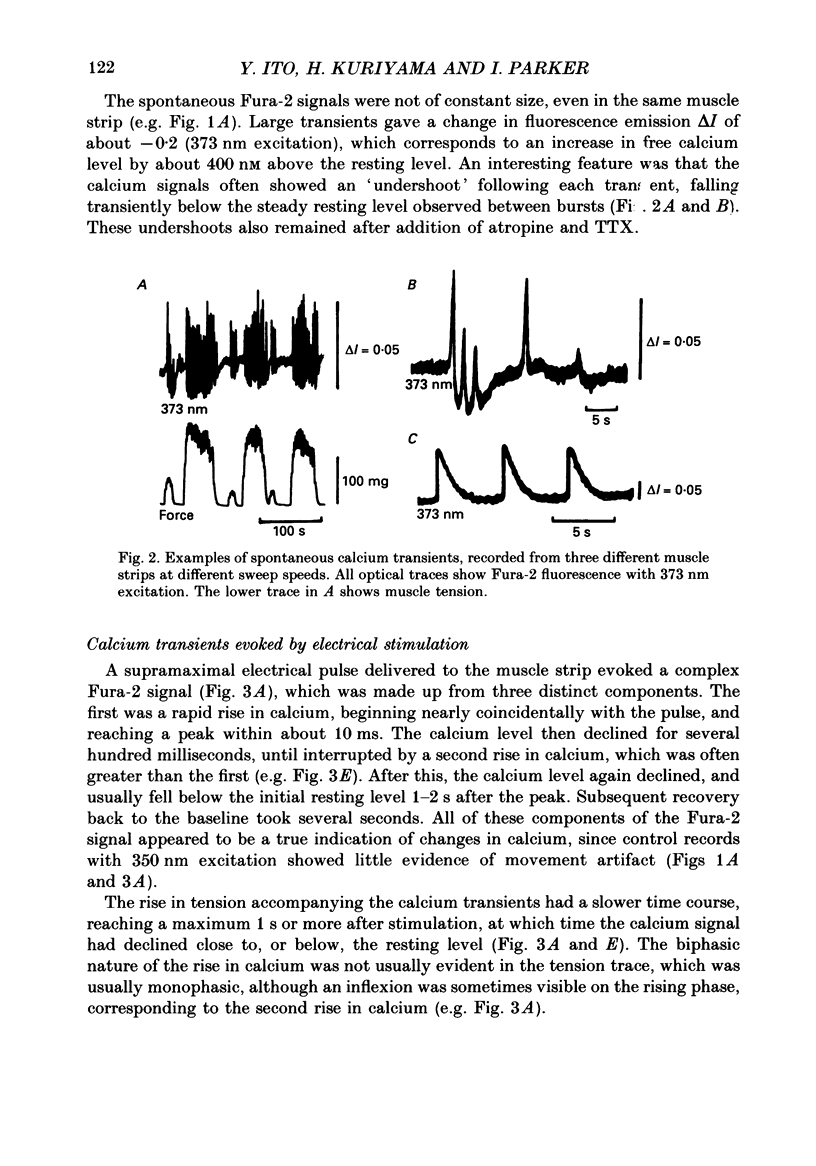

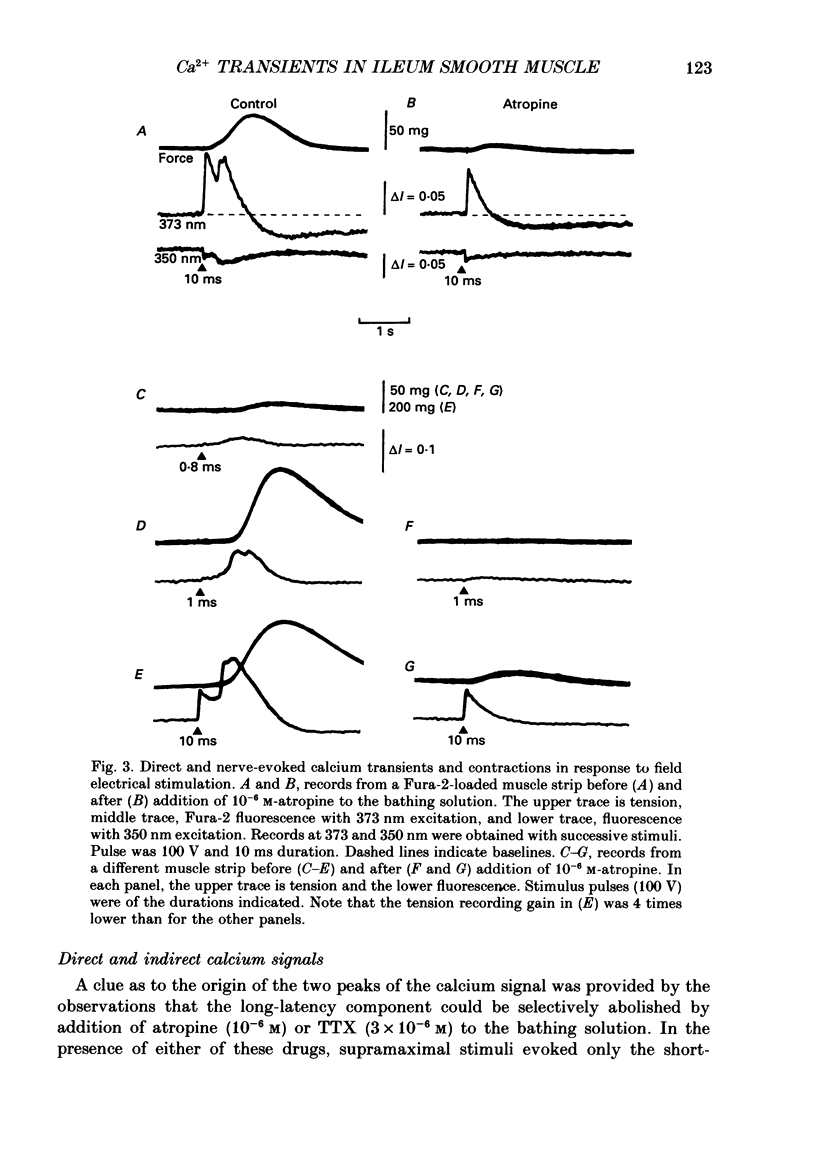

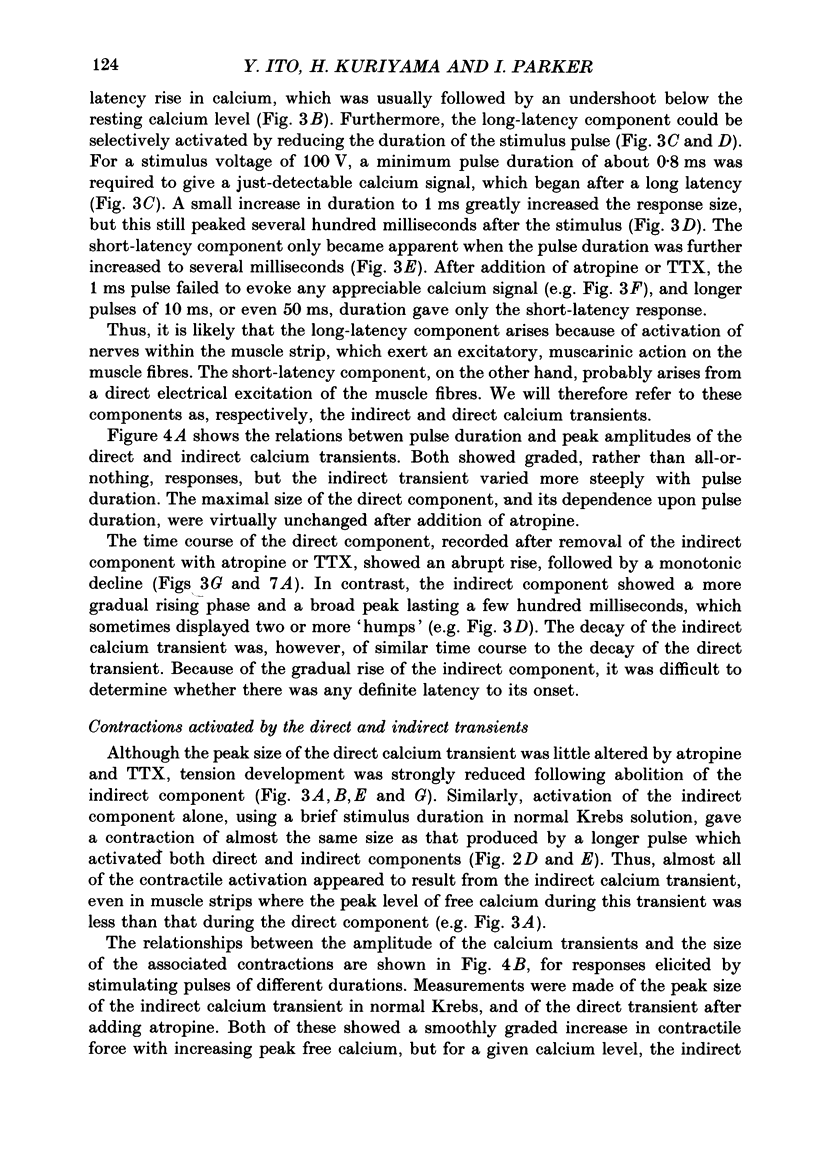

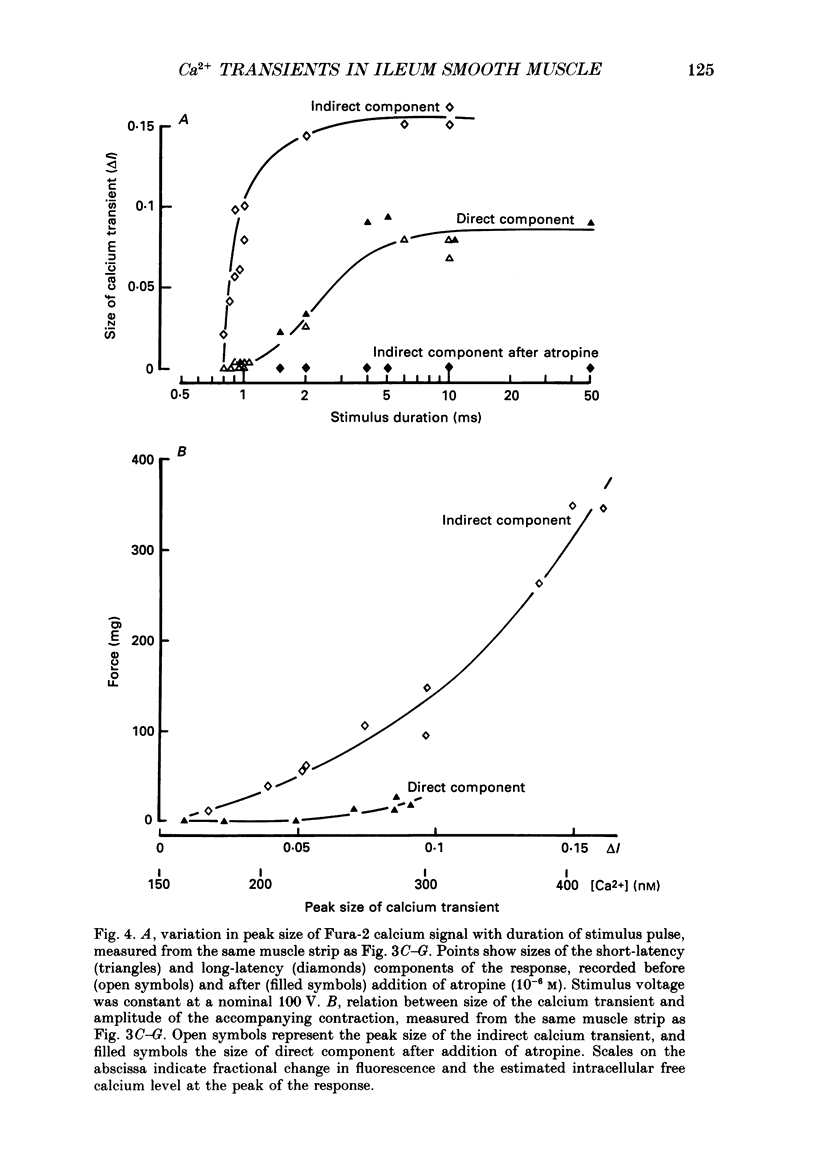

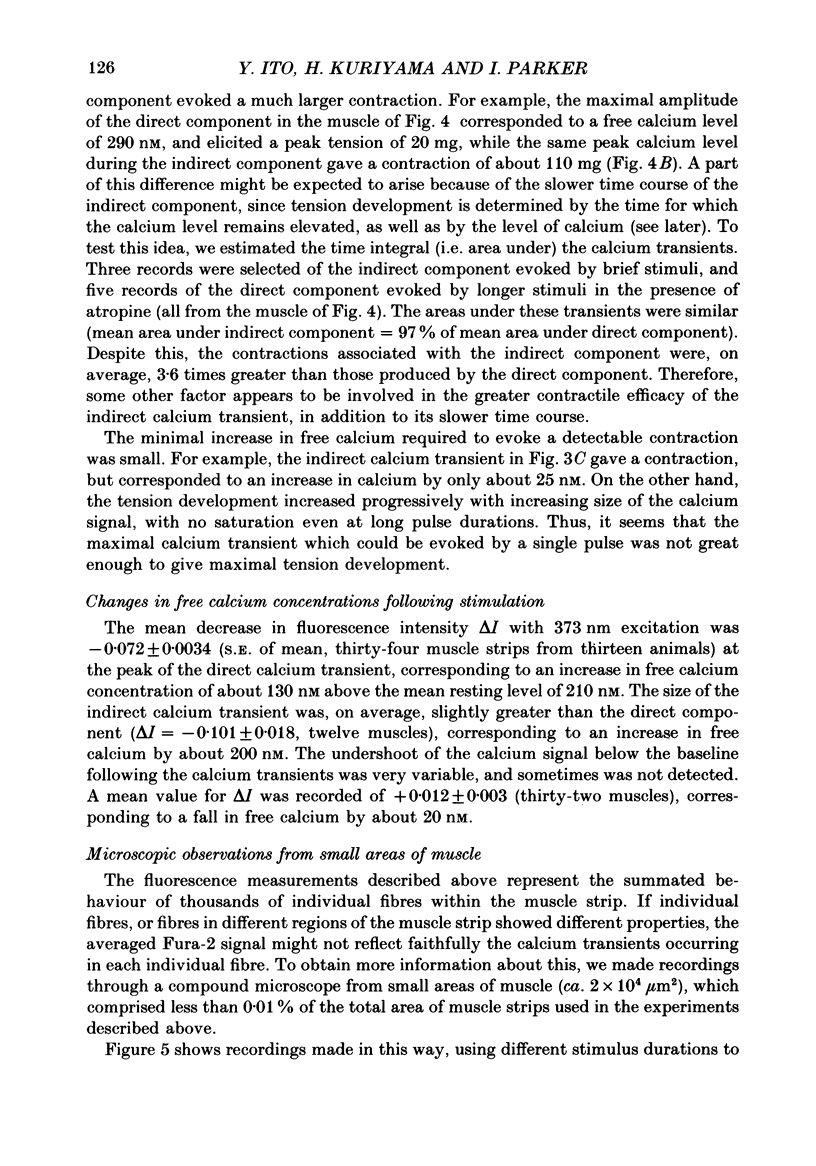

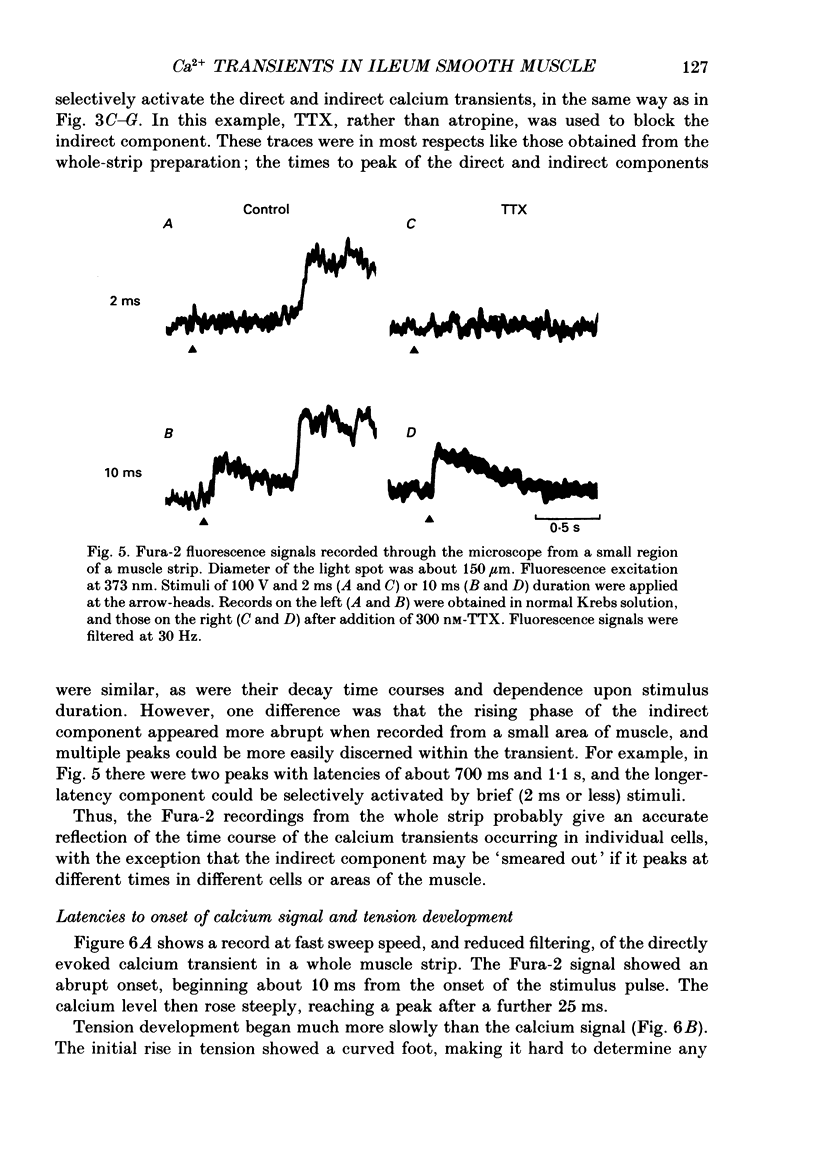

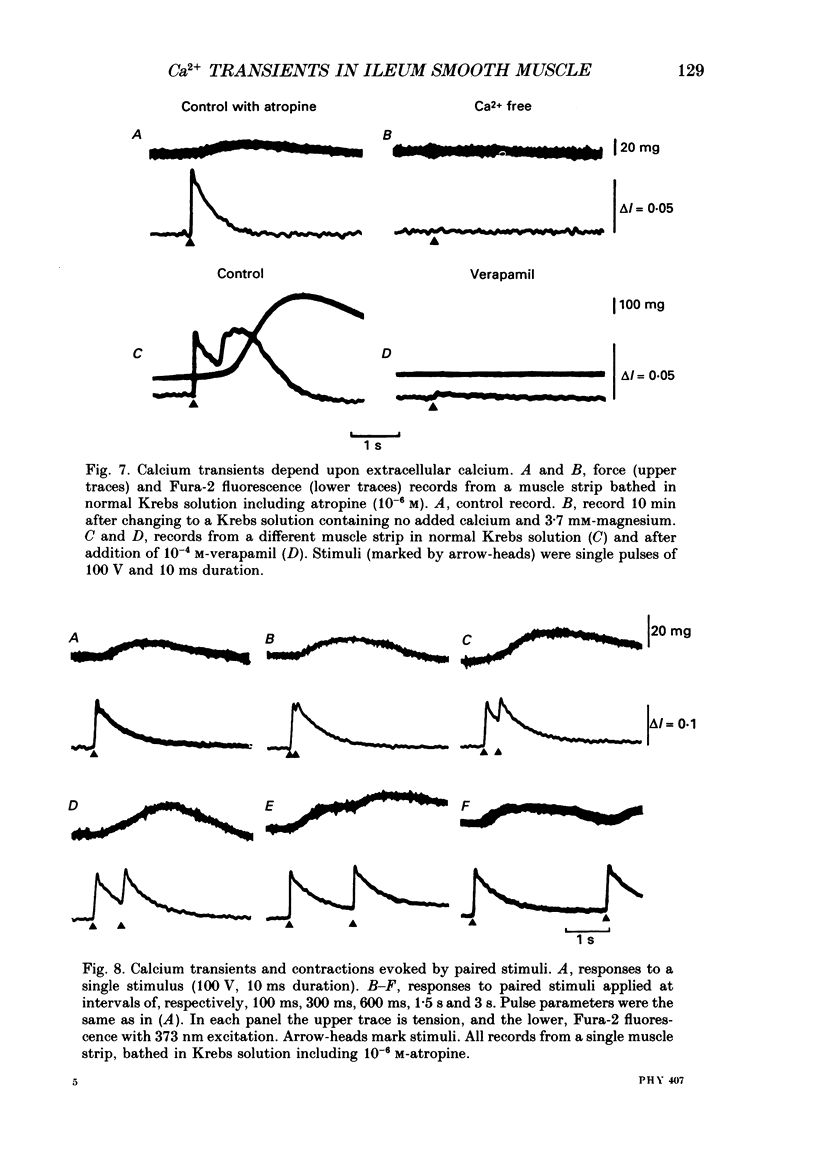

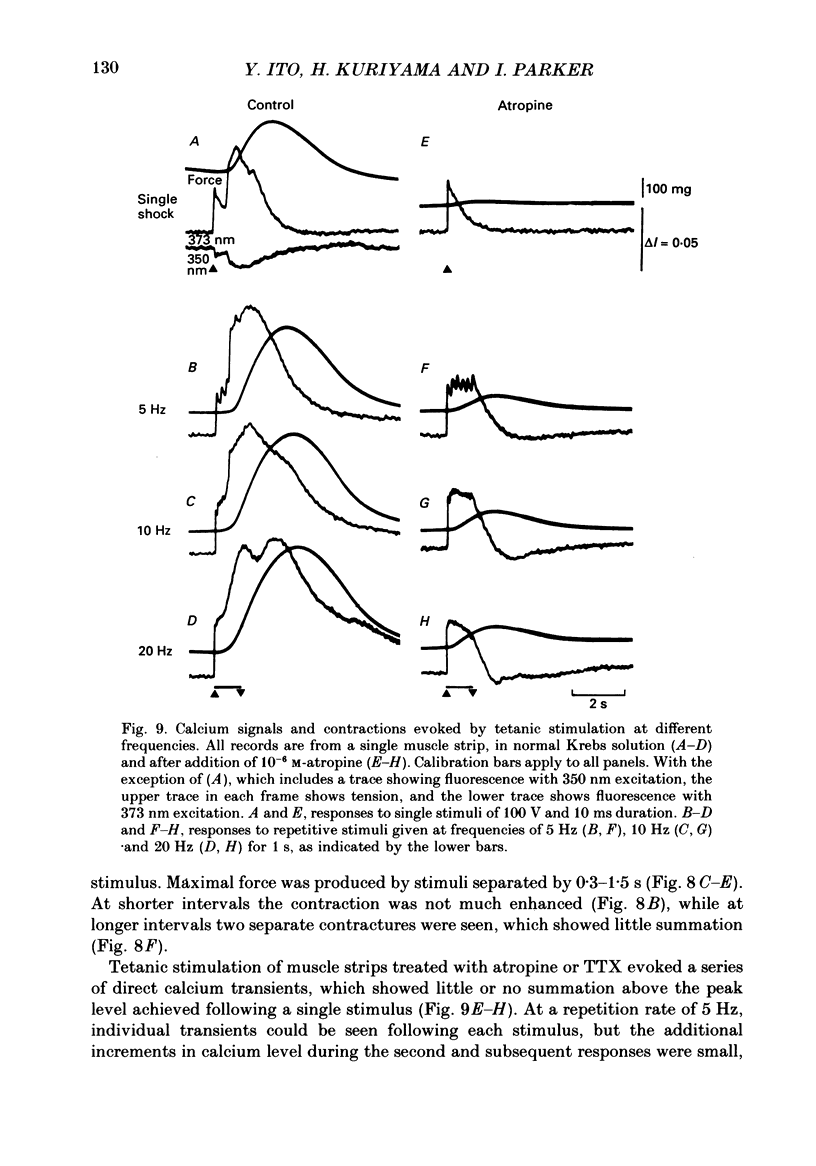

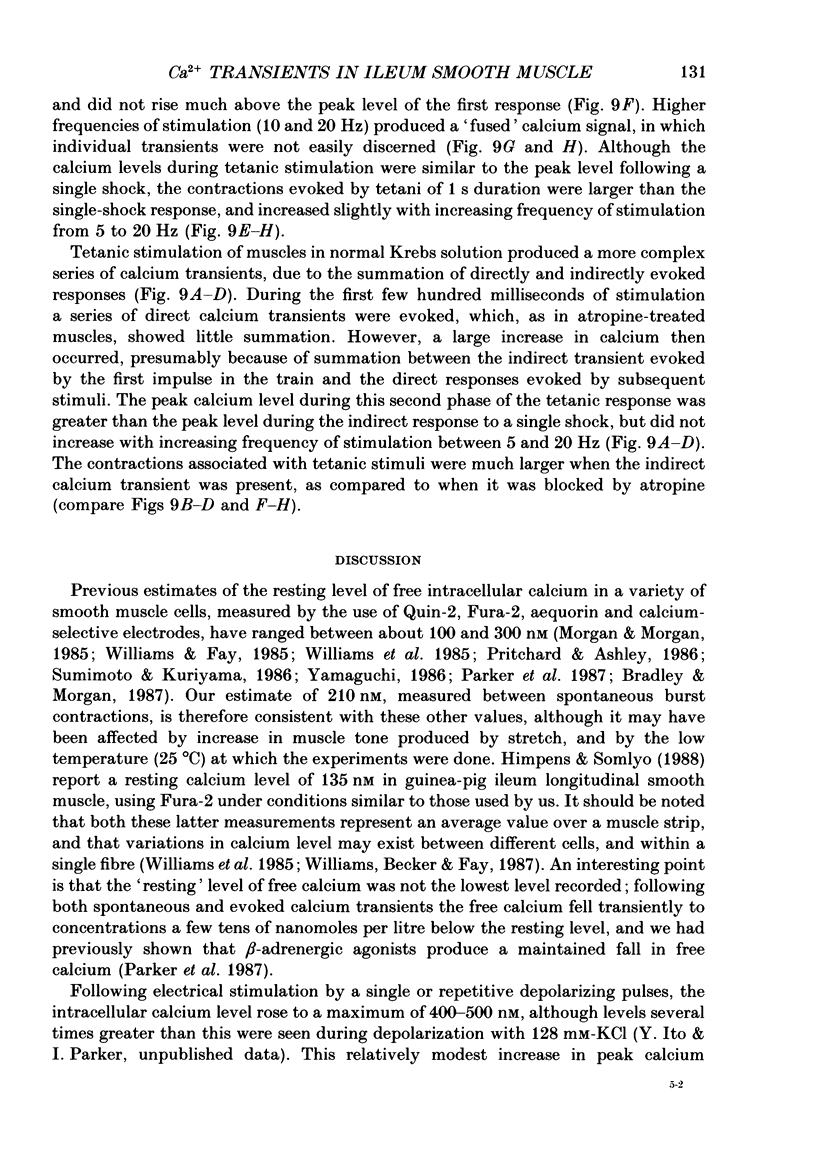

1. Intracellular free calcium levels were recorded in strips of longitudinal smooth muscle from guinea-pig ileum, by the use of the fluorescent calcium indicator Fura-2. 2. The resting intracellular free calcium concentration was estimated to be 210 nM. Many muscle strips showed spontaneous bursts of contractions, accompanied by bursts of calcium transients. Following these the calcium level often fell transiently below the resting level. The spontaneous transients were unaffected by tetrodotoxin (TTX) and atropine. 3. Field electrical stimulation of muscle strips evoked a series of calcium transients comprising: (i) an initial rise in free calcium, reaching a peak within 20-30 ms of stimulation, (ii) a second rise in calcium, beginning after a few hundred milliseconds, and finally (iii) a decline in calcium to below the resting level, persisting for a few seconds. The mean peak increase in free calcium above the resting level during components (i) and (ii) was, respectively, 130 and 200 nM. The mean decrease in free calcium during the third component was to 20 nM below the resting level. 4. The short-latency calcium transient required relatively long stimuli for activation, and was not blocked by TTX and atropine. The long-latency transient was selectively activated by brief stimuli, and was abolished by TTX and atropine. Thus, the short-latency component probably arose because of direct electrical stimulation of muscle fibres, while the long-latency component was due to stimulation of muscarinic nerves. 5. The first detectable increase in tension began about 100 ms after the peak of the initial calcium transient. Contractions associated with the long-latency calcium transient were much larger than those associated with the short-latency transient, even in muscle strips where the calcium levels were similar for both transients. 6. Removal of calcium in the bathing solution caused the resting intracellular calcium level to fall, following an initial rise accompanied by increased spontaneous transients. Electrically evoked contractions and calcium transients were abolished in calcium-free solution, and by the addition of verapamil or diltiazem to normal Krebs solution.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bauer V., Kuriyama H. Evidence for non-cholinergic, non-adrenergic transmission in the guinea-pig ileum. J Physiol. 1982 Sep;330:95–110. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge M. J. Inositol trisphosphate and diacylglycerol: two interacting second messengers. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56:159–193. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.001111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blinks J. R., Wier W. G., Hess P., Prendergast F. G. Measurement of Ca2+ concentrations in living cells. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1982;40(1-2):1–114. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(82)90011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley A. B., Morgan K. G. Alterations in cytoplasmic calcium sensitivity during porcine coronary artery contractions as detected by aequorin. J Physiol. 1987 Apr;385:437–448. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFeo T. T., Morgan K. G. A comparison of two different indicators: quin 2 and aequorin in isolated single cells and intact strips of ferret portal vein. Pflugers Arch. 1986 Apr;406(4):427–429. doi: 10.1007/BF00590948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFeo T. T., Morgan K. G. Calcium-force relationships as detected with aequorin in two different vascular smooth muscles of the ferret. J Physiol. 1985 Dec;369:269–282. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fay F. S., Shlevin H. H., Granger W. C., Jr, Taylor S. R. Aequorin luminescence during activation of single isolated smooth muscle cells. Nature. 1979 Aug 9;280(5722):506–508. doi: 10.1038/280506a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewicz G., Poenie M., Tsien R. Y. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem. 1985 Mar 25;260(6):3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartzell H. C. Mechanisms of slow postsynaptic potentials. Nature. 1981 Jun 18;291(5816):539–544. doi: 10.1038/291539a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto T., Hirata M., Itoh T., Kanmura Y., Kuriyama H. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate activates pharmacomechanical coupling in smooth muscle of the rabbit mesenteric artery. J Physiol. 1986 Jan;370:605–618. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp015953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himpens B., Somlyo A. P. Free-calcium and force transients during depolarization and pharmacomechanical coupling in guinea-pig smooth muscle. J Physiol. 1988 Jan;395:507–530. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp016932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh T., Kanmura Y., Kuriyama H., Sumimoto K. A phorbol ester has dual actions on the mechanical response in the rabbit mesenteric and porcine coronary arteries. J Physiol. 1986 Jun;375:515–534. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maylie J., Irving M., Sizto N. L., Chandler W. K. Calcium signals recorded from cut frog twitch fibers containing antipyrylazo III. J Gen Physiol. 1987 Jan;89(1):83–143. doi: 10.1085/jgp.89.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miledi R., Parker I., Zhu P. H. Calcium transients evoked by action potentials in frog twitch muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1982 Dec;333:655–679. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan J. P., Morgan K. G. Alteration of cytoplasmic ionized calcium levels in smooth muscle by vasodilators in the ferret. J Physiol. 1984 Dec;357:539–551. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan J. P., Morgan K. G. Stimulus-specific patterns of intracellular calcium levels in smooth muscle of ferret portal vein. J Physiol. 1984 Jun;351:155–167. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan J. P., Morgan K. G. Vascular smooth muscle: the first recorded Ca2+ transients. Pflugers Arch. 1982 Oct;395(1):75–77. doi: 10.1007/BF00584972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neering I. R., Morgan K. G. Use of aequorin to study excitation--contraction coupling in mammalian smooth muscle. Nature. 1980 Dec 11;288(5791):585–587. doi: 10.1038/288585a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker I., Ito Y., Kuriyama H., Miledi R. Beta-adrenergic agonists and cyclic AMP decrease intracellular resting free-calcium concentration in ileum smooth muscle. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1987 Mar 23;230(1259):207–214. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1987.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poenie M., Alderton J., Tsien R. Y., Steinhardt R. A. Changes of free calcium levels with stages of the cell division cycle. Nature. 1985 May 9;315(6015):147–149. doi: 10.1038/315147a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard K., Ashley C. C. Na+/Ca2+ exchange in isolated smooth muscle cells demonstrated by the fluorescent calcium indicator fura-2. FEBS Lett. 1986 Jan 20;195(1-2):23–27. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(86)80122-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RANG H. P. STIMULANT ACTIONS OF VOLATILE ANAESTHETICS ON SMOOTH MUSCLE. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1964 Apr;22:356–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1964.tb02040.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somlyo A. V., Bond M., Somlyo A. P., Scarpa A. Inositol trisphosphate-induced calcium release and contraction in vascular smooth muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 Aug;82(15):5231–5235. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.15.5231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumimoto K., Kuriyama H. Mobilization of free Ca2+ measured during contraction-relaxation cycles in smooth muscle cells of the porcine coronary artery using quin2. Pflugers Arch. 1986 Feb;406(2):173–180. doi: 10.1007/BF00586679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien R. Y., Rink T. J., Poenie M. Measurement of cytosolic free Ca2+ in individual small cells using fluorescence microscopy with dual excitation wavelengths. Cell Calcium. 1985 Apr;6(1-2):145–157. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(85)90041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker J. W., Somlyo A. V., Goldman Y. E., Somlyo A. P., Trentham D. R. Kinetics of smooth and skeletal muscle activation by laser pulse photolysis of caged inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate. Nature. 1987 May 21;327(6119):249–252. doi: 10.1038/327249a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. A., Becker P. L., Fay F. S. Regional changes in calcium underlying contraction of single smooth muscle cells. Science. 1987 Mar 27;235(4796):1644–1648. doi: 10.1126/science.3103219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. A., Fogarty K. E., Tsien R. Y., Fay F. S. Calcium gradients in single smooth muscle cells revealed by the digital imaging microscope using Fura-2. Nature. 1985 Dec 12;318(6046):558–561. doi: 10.1038/318558a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi H. Recording of intracellular Ca2+ from smooth muscle cells by sub-micron tip, double-barrelled CA2+-selective microelectrodes. Cell Calcium. 1986 Aug;7(4):203–219. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(86)90001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]