Abstract

Emotional and cognitive impairments are comorbidities commonly associated with chronic inflammatory pain. To summarize the rules and mechanisms of comorbidities in a complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA)-induced pain model, we conducted a systematic review of 66 experimental studies identified in a search of three databases (PubMed, Web of Science, and ScienceDirect). Anxiety-like behaviors developed at 1- or 3-days post-CFA induction but also appeared between 2- and 4 weeks post-induction. Pain aversion, pain depression, and cognitive impairments were primarily observed within 2 weeks, 4 weeks, and 2–4 weeks post-CFA injection, respectively. The potential mechanisms underlying the comorbidities between pain and anxiety predominantly involved heightened neuronal excitability, enhanced excitatory synaptic transmission, and neuroinflammation of anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and amygdala. The primary somatosensory cortex (S1)Glu→caudal dorsolateral striatum (cDLS)GABA, medial septum (MS)CHAT→rACC, rACCGlu→thalamus, parabrachial nucleus (PBN)→central nucleus amygdala (CeA), mediodorsal thalamus (MD)→basolateral amygdala (BLA), insular cortex (IC)→BLA and anteromedial thalamus nucleus (AM)CaMKⅡ→midcingulate cortex (MCC)CaMKⅡ pathways are enhanced in the pain-anxiety comorbidity. The ventral hippocampal CA1 (vCA1)→BLA and BLA→CeA pathways were decreased in the pain-anxiety comorbidity. The BLA→ACC pathway was enhanced in the pain-depression comorbidity. The infralimbic cortex (IL)→locus coeruleus (LC) pathway was enhanced whereas the vCA1→IL pathway was decreased, in the pain-cognition comorbidity. Inflammation/neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, apoptosis, ferroptosis, gut-brain axis dysfunction, and gut microbiota dysbiosis also contribute to these comorbidities.

Keywords: Complete Freund’s adjuvant, Chronic inflammatory pain, Anxiety, Depression, Cognitive impairment, Comorbidity, Potential mechanism

Introduction

Chronic pain is a major cause of personal and economic suffering that affects > 30 % of individuals worldwide (Cohen et al., 2021). Unlike acute pain, which results in early physiological protection, chronic pain is maladaptive and non-protective. Furthermore, pain control becomes increasingly difficult as pain progresses to a chronic state. Pain is characterized by three specific dimensions: sensory-discriminative, emotional-affective, and cognitive-evaluative (Raja et al., 2020). Research has shown that chronic pain is often associated with depression, anxiety, cognitive impairment, and negative social outcomes. Recent advancements in the understanding of the neural circuit’s role regulating the psychological modulation of pain indicate that chronic pain can result in anatomical and functional alterations in the same circuit, significantly affecting not only pain but also one’s emotional state and cognitive ability (Bushnell et al., 2013). An individual’s emotional state has a significant impact on pain, with negative emotions amplifying the sensation of pain whereas positive emotions reduce it (Villemure and Bushnell, 2002). Furthermore, a vicious circle forms, whereby chronic pain triggers intense emotional changes that increase pain perception (Fonseca-Rodrigues et al., 2021).

To gain a better understanding of chronic pain and its related emotional and cognitive impairments, several animal models have been developed to simulate chronic pain and its aftereffects. Neuropathic pain is included using spinal nerve ligation-induced and chronic constriction injury-induced pain models (Fonseca-Rodrigues et al., 2021). Inflammatory pain is studied using formalin-induced, carrageenan-induced, and complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA)-induced pain models. The CFA-induced pain model is the most frequently used model in the study of chronic inflammatory pain owing to its simplicity, high level of repeatability, and measurable parameters (Coderre and Laferrière, 2020). Several studies have demonstrated the efficacy of this model in eliciting emotional and cognitive impairments related to pain (Urban et al., 2011, Zheng et al., 2017); however, the mechanisms underlying these phenomena are not fully understood, and require further investigation. A summary of the rules governing this model could facilitate the development of measures for the intervention and treatment of comorbidities, such as chronic inflammatory pain and pain-related anxiety and impaired cognition.

We conducted a systematic literature review to summarize the regulations and mechanisms used to induce and evaluate the development of emotional and cognitive impairments in the CFA model. We then used the rodent CFA model as an example to evaluate its usefulness in preclinical research and to provide guidance and suggestions.

Materials and methods

Registration

This study was registered in PROSPERO’s International Registry of Systematic Reviews under the registration number CRD42022358422 (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO).

Search strategies

This systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. We conducted a systematic literature search using PubMed, Web of Science, and ScienceDirect electronic databases. The details of our search strategy are shown in Fig. 1. Each database was searched for the following phrase from their inception through December 1, 2023: (“CFA” OR “complete Freund’s adjuvant”) AND (“anxiety” OR “anxious” OR “depressive” OR “depression” OR “cognition” OR “cognitive”) AND (“animal”). Upon completion of the search, duplicates were removed, and the abstracts of the remaining articles were assessed. The retrieved records were screened for relevance prior to inclusion in the study, and those that did not meet the inclusion criteria were noted but not analyzed further.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the search strategy. 1554 articles were identified using Pubmed, Science Direct and Web of Science databases. Articles were included/excluded based on relevance. A total of 66 articles were included for further analysis.

Inclusion criteria

Original research studies were included based on the following criteria: (1) animal CFA inflammatory pain model; (2) adult rodents injected with CFA into the hind paw; (3) studies demonstrating the presence of nociceptive behavior after the injection of CFA; and (4) outcome indicators, including the evaluation of nociception, locomotion, and emotional-like behavior or cognitive performance. All searches were limited to English-language journal articles published before December 1, 2023.

Exclusion criteria

Studies involving humans, case reports, cellular studies, and review articles were excluded, although their references were searched to identify supplementary studies that met the inclusion criteria. Conference proceedings and incomplete papers were also excluded.

Study selection

Two investigators (Naixuan Wei and Lu Guan) independently evaluated the articles identified based on the aforementioned search strategy, and potentially relevant articles were retrieved in full. A final inclusion or exclusion determination was made after a full-text review of the eligible studies. In cases of initial disagreement regarding an article’s eligibility a third investigator (Junying Du) was included in the discussion to reach a consensus on whether the article would be included or excluded.

Date extraction

The following data were extracted from the included studies: author, year of publication, species/strain of animals, age, sample size, sex, method of CFA-induced inflammation (including CFA inflammatory agent, dose, location, and side of CFA injection), duration of the model, time points at which measurements were made (hour/day post-inflammation), and all tests used to evaluate nociception, locomotion, emotion-like behavior, and cognitive performance as well as and the outcomes of these measures. The research mechanism data for pain and pain-related emotional and cognitive impairments were also extracted. In studies with multiple interventions, only data from the non-inflamed (control) and inflamed groups were analyzed.

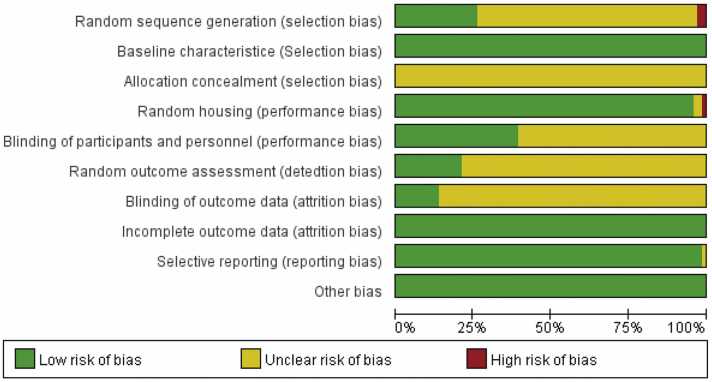

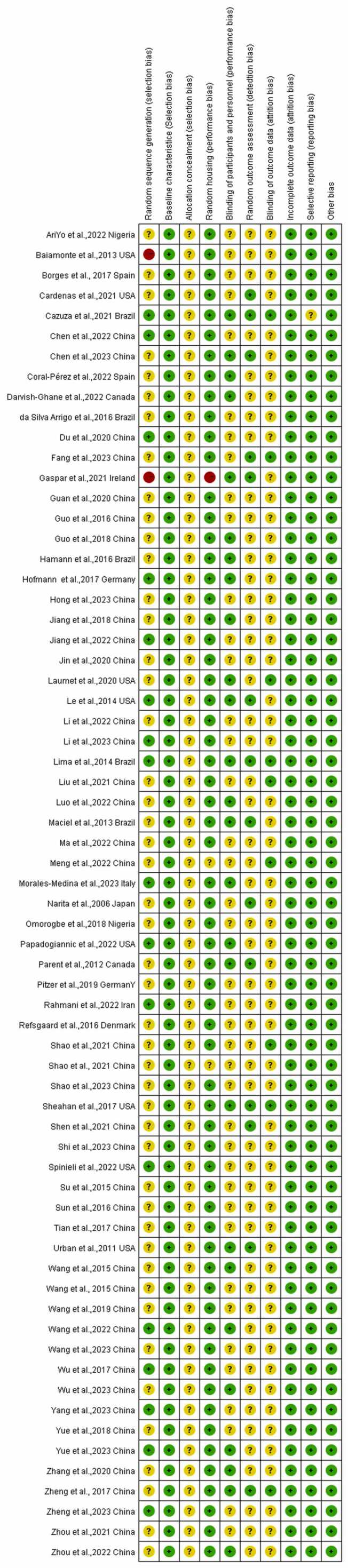

Risk of bias

Two investigators (Naixuan Wei and Zi Guo) independently reviewed the included studies and assessed the risk of bias. The risk of bias was evaluated using the Systematic Review Center (SYRCLE) checklist based on the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias (RoB) tool, which consists of ten items across six primary domains: selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias, and other sources of bias. Responses to the bias judgments were “yes” for low risk of bias, “no” for high risk of bias, and “UN” for an uncertain level of bias owing to insufficient information. We addressed these discrepancies through discussion or consultation with a third-party investigator (Junying Du).

Quality assessment

Three reviewers (Naixuan Wei, Ru Ye and Lu Guan) assessed the quality of the included literature using Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines. The details are as follows: title, abstract, background, objective, ethical statement, study design, experimental procedures, blinding, experimental animals, housing and husbandry, sample size, allocation of animals to experimental groups, experimental outcomes, statistical methods, baseline data, numbers analyzed, outcomes and estimation, individual data points, adverse events, interpretation/scientific implications, generalizability/translation, and funding. Each study was assigned a value of 1, 0.5, and 0, based on whether it was complete, incomplete, or non-applicable/absent, respectively. A fourth reviewer (Junfan Fang) resolved all disagreements.

Statistical analysis

We used EndNote and Zotero to save the articles included in this study and establish a database thereof. Microsoft Excel 2016 was used to create tables and record the extracted data, which were imported into SPSS 19.0 and SPSS modeler 14.1 for further analysis. The risk of bias was determined using RevMan 5.4.

Results

Study selection

We obtained 1554 papers from our initial search (Fig. 1). After removing duplicate articles, 1376 potential studies were identified, 1117 of which were excluded based on the screening of titles and abstracts, resulting in 259 potentially eligible studies. In total, 66 studies meet all of the eligibility criteria after reviewing the texts in full.

Characteristics of the included studies

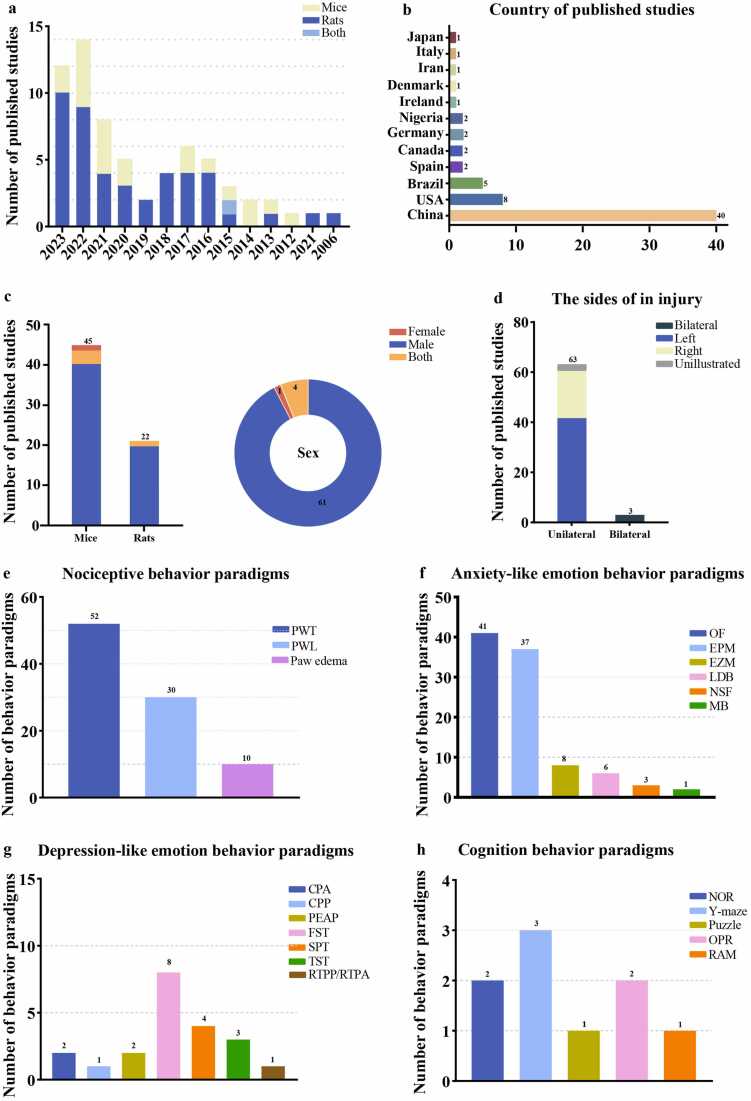

The studies included in this review were published between 2006 and 2023 (Fig. 2a). The first authors of the studies were from a diverse range of countries, including China, Europe, North America, South America, Asia, and Africa (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Characteristics of the Included Studies. a. Number of studies meeting the inclusion criteria. The X-axis represents the publication year. b. Country of published studies. c. Species and sex of the included study animals. d. Location of the CFA injection in the test animals. e-h. behavioral paradigms assessing aggressive behavior, anxiety-like behavior, depressive-like behavior, and cognitive behavior.

Among the 66 experimental studies included in the literature review (Urban et al., 2011, Zheng et al., 2017, Narita et al., 2006, Parent et al., 2012, Baiamonte et al., 2013, Maciel et al., 2013, Lee et al., 2014, Lima et al., 2014, Wang et al., 2015a, Wang et al., 2015b, Su et al., 2015, da SA et al., 2016, Guo et al., 2016, Hamann et al., 2016, Refsgaard et al., 2016, Sun et al., 2016, Hofmann et al., 2017, Sheahan et al., 2017, J et al., 2017, Wu et al., 2017, Borges et al., 2017, Guo et al., 2018, Jiang et al., 2018, Omorogbe et al., 2018, Yue et al., 2018, Pitzer et al., 2019, Wang et al., 2019, Du et al., 2020, Guan et al., 2020, Jin et al., 2020, Laumet et al., 2020, Zhang et al., 2020, Cardenas et al., 2021, Cazuza et al., 2021, Gaspar et al., 2021, Liu et al., 2021, Shao et al., 2021a, Shao et al., 2021b, Shen et al., 2020, Zhou et al., 2021, Ariyo et al., 2022, Chen et al., 2022a, Coral-Pérez et al., 2022, Darvish-Ghane et al., 2022, Jiang et al., 2022, Li et al., 2022, Luo et al., 2022, Ma et al., 2022, Meng et al., 2022, Papadogiannis and Dimitrov, 2022, Rahmani et al., 2022, Spinieli et al., 2022, Wang et al., 2022, Zhou et al., 2022, Chen et al., 2023, Fang et al., 2023, Hong et al., 2023, Li et al., 2023, Morales-Medina et al., 2023, Rong et al., 2023, Shao et al., 2023, Shi et al., 2022, Wang et al., 2023, Wu et al., 2023, Yang et al., 2023, Yue et al., 2023), mice were the most frequently used animals, with 45 studies (68.1 %) using mice as subjects and 22 studies using rats (33.3 %) (Fig. 2c). There was an imbalance in the number of male and female animals among the included studies, with 61 studies conducted on male animals, 1 on females, and 4 on both (Fig. 2c). Of the 66 included studies, 62 recorded the age and weight of the animals used, whereas 4 did not report any weight/age-related information (Table 1). Approximately 97 % of the studies used young adult rats or mice (64/66), while 1 targeted adolescent rats and 1 did not provide relevant information (Table 1). Among the 45 mouse studies included in this article, C57BL/6 J strain mice were most frequently used. Additionally, different strains of transgenic mice were used based on the specific experimental designs designed in different articles. Sprague Dawley and Wistar rats were used in the 21 included rat studies, the majority of which were Sprague Dawley (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of chronic inflammatory pain models studies.

| Article | Strain | Sex | Age (weeks) | Body weight(g) | Inflammatory agent | Side | Dosage | Injection times | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mice | |||||||||

| Narita et al.,2006 Japan | C57BL/6 J | M | Adult | 18–23 g | CFA (Sigma) | R | 50 μL | One | 9 |

| Urban et al.,2011 USA | Balb/c; C57Bl/6 | M | Adult | 7–10 weeks | CFA (Sigma) | L | 10 μL | Two | 7 |

| Maciel et al.,2013 Brazil | Swiss mice | M | Adult | 25–30 g | CFA (Sigma) | R/L | 50 μL | One | 12 |

| Wang et al.,2015 China | C57BL/6 | M | Adult | 20–25 g | CFA (Sigma) | R/L | 10 μL | One | 15 |

| Wang et al.,2015 China | C57BL/6 | M | Adult | 8 weeks | CFA (Sigma) | L | 10 μL | One | 16 |

| da Silva Arrigo et al.,2016 Brazil | C57BL/6 J | M | Adult | 20–25 g | CFA (Sigma) | R | 20 μL | One | 18 |

| Guo et al.,2016 China | C57BL/6 J | M | Adult | 8–10 weeks | CFA (Sigma) | L | 10 μL | One | 19 |

| Refsgaard et al.,2016 Denmark | C57BL/6 J | F | Adult | 18–22 g | CFA (Sigma) | R | 25 μL | One | 21 |

| Sun et al.,2016 China | C57BL/6 J | M | Adult | 6–8 weeks | CFA (Sigma) | L | 10 μL | One | 22 |

| Hofmann et al.,2017 Germany | C57BL/6 J | M | Adult | Young (3 months) and old (≥18 mounths) | CFA (Sigma) | R | 10 μL | One | 23 |

| Sheahan et al.,2017 USA | C57BL/6 J | M | Adult | 7–9 weeks | CFA (Sigma) | R/L | 20 μL | One | 24 |

| Tian et al.,2017 China | C57BL/6 | M | Adult | 8–10 weeks | CFA (Sigma) | L | 10 μL | One | 25 |

| Zheng et al., 2017 China | C57BL/6 | M | Adult | 5–8 weeks / 20–30 g | CFA (Sigma) | L | 50 μL | One | 8 |

| Guo et al.,2018 China | C57BL/6 | M | Adult | 8–12 weeks | CFA (Sigma) | R/L | 10 μL | One | 28 |

| Jiang et al.,2018 China | C57BL/6 | M | Adult | 8–10 weeks | CFA (Sigma) | L | 40 μL | One | 29 |

| Omorogbe et al.,2018 Nigeria | Swiss mice | M | Adult | 22–26 g | CFA (Sigma) | L | 100 μL | One | 30 |

| Yue et al.,2018 China | C57BL/6 | M | Adult | 6–8 weeks | CFA (Sigma) | R | 10 μL | One | 31 |

| Pitzer et al.,2019 Germany | C57BL/6 N; C57BL/6 J | M/F | Adult | 8 weeks | CFA (Sigma) | R/L | 20 μL | One | 32 |

| Wang et al.,2019 China | C57BL/6 J | M | Adult | 7–8 weeks | CFA (Sigma) | R | 10 μL | One | 33 |

| Guan et al.,2020 China | C57BL/6 J | M | Adult | 6–8 weeks | CFA (Sigma) | R | 10 μL | One | 35 |

| Jin et al.,2020 China | C57BL/6 J | M | Adult | 8–10 weeks | CFA (Sigma) | L | 20 μL | Two | 36 |

| Laumet et al.,2020 USA | C57BL/6 J | M | Adult | 9–12 weeks | CFA (Sigma) | L | 5 μL | One | 37 |

| Cardenas et al.,2021 USA | CD−1 mice | M/F | / | / | CFA (Sigma) | R | 20 μL | One | 39 |

| Cazuza et al.,2021 Brazil | C57BL/6 J | M | Adult | 8–10 weeks/ 20–25 g | CFA (Sigma) | L | 30 μL | One | 40 |

| Liu et al.,2021 China | C57BL/6 J | M | Adult | 6–8 weeks | CFA (Sigma) | L | 10 μL | One | 42 |

| Zhou et al.,2021 China | C57BL/6 J | M | Adult | 8–10 weeks | CFA (Sigma) | L | 10 μL | One | 46 |

| Chen et al.,2022 China | C57BL/6 J | M | Adult | 8 weeks/21–25 g | CFA (Sigma) | L | 10 μL | One | 48 |

| Coral-Pérez et al.,2022 Spain | C57BL/6 J | M | Adult | 6–8 weeks/25–26 g | CFA (Sigma) | R | 30 μL | One | 49 |

| Darvish-Ghane et al.,2022 Canada | C57BL/6 J | M | Adult | 6–8 weeks | CFA (Sigma) | R/L | 20 μL | One | 50 |

| Jiang et al.,2022 China | C57BL/6 J | M | Adult | 3 months old | CFA (Sigma) | L | 20 μL | One | 51 |

| Li et al.,2022 China | C57BL/6 J | M | Adult | 8–10 weeks | CFA (Sigma) | L | 20 μL | One | 52 |

| Meng et al.,2022 China | C57BL/6 J | M | Adult | 8–12 weeks | CFA (Sigma) | L | 20 μL | One | 55 |

| Papadogiannis et al.,2022 USA | CD−1 mice | M/F | Adult | / | / | L | 20 μL | One | 56 |

| Wang et al.,2022 China | C57BL/6 J | M | Adult | 8–12 weeks | CFA (Sigma) | R | 10 μL | One | 59 |

| Zhou et al.,2022 China | C57BL/6 J | M | Adult | / | CFA (Sigma) | L | 15 μl | One | 60 |

| Chen et al.,2023 China | C57BL/6 J | M | Adult | 6–7 weeks | CFA (Sigma) | R&L | 10 μL | One | 61 |

| Fang et al.,2023 China | C57BL/6 J | M | Adult | 6–8 weeks | CFA (Sigma) | L | 10 μL | One | 62 |

| Hong et al.,2023 China | C57BL/6 J | M | Adult | 20–25 g | CFA (Sigma) | L | 20 μL | One | 63 |

| Li et al.,2023 China | C57BL/6 J | M | Adult | 8–10 weeks/20–25 g | CFA (Sigma) | L | 20 μL | One | 64 |

| Rong et al.,2023 China | C57BL/6 J | M | Adult | 6–8 weeks | CFA (Sigma) | L | 10 μL | One | 66 |

| Shao et al.,2023 China | C57BL/6 J | M | Adult | 10–12weeks | CFA (Sigma) | L | 40 μL | One | 67 |

| Shi et al.,2023 China | C57BL/6 J | M | Adult | / | CFA (Sigma) | L | 10 μL | One | 68 |

| Wang et al.,2023 China | C57BL/6 J | M | Adult | 8–10 weeks | CFA (Sigma) | L | 10 μL | One | 69 |

| Wu et al.,2023 China | C57BL/6 J | M | Adult | 8 weeks | CFA (Sigma) | L | 10 μL | One | 70 |

| Yue et al.,2023 China | C57BL/6 J | M | Adult | 8–10 weeks | CFA (Sigma) | L | 50 μL | One | 72 |

| Rat | |||||||||

| Parent et al.,2012 Canada | Sprague Dawley | M | Adult | 175–225 g | CFA (Sigma) | L | 100 μL | One | 10 |

| Baiamonte et al.,2013 USA | Sprague Dawley | M | Adult | 225–350 g | CFA (Sigma) | L | 70 μL | One | 11 |

| Le et al.,2014 USA | Sprague Dawley | M | Adult | 250–300 g | CFA (Sigma) | R | 100 μL | One | 13 |

| Lima et al.,2014 Brazil | Sprague Dawley | M/F | Adolescent | / | CFA (Sigma) | L | 25 μL | One | 14 |

| Wang et al.,2015 China | Sprague Dawley | M | Adult | 200–250 g | CFA (Sigma) | R/L | 100 μL | One | 15 |

| Su et al.,2015 China | Sprague Dawley | M | Adult | 250–300 g | CFA (Sigma) | R | 100 μL | One | 17 |

| Hamann et al.,2016 Brazil | Wistar | M | Adult | 3 months old/ 250–300 g | CFA (Sigma) | R | 100 μL | One | 20 |

| Wu et al.,2017 China | Sprague Dawley | M | Adult | 250 ± 20 g | CFA (Sigma) | L | 100 μL | One | 26 |

| Borges et al., 2017 Spain | Sprague Dawley | M | Adult | 200–300 g | CFA (Sigma) | L | 50 μL | One | 27 |

| Du et al.,2020 China | Sprague Dawley | M | Adult | 180–220 g | CFA (Sigma) | L | 100 μL | One | 34 |

| Zhang et al.,2020 China | Sprague Dawley | M | Adult | 250–300 g | CFA (Sigma) | L | 50 μL | One | 38 |

| Gaspar et al.,2021 Ireland | Sprague Dawley | M | Adult | 230–250 g | CFA (Sigma) | R | 100 μL | One | 41 |

| Shao et al.,2021 China | Sprague Dawley | M | Adult | 200–220 g | CFA (Sigma) | L | 100 μL | One | 43 |

| Shao et al.,2021 China | Sprague Dawley | M | Adult | 180–240 g | CFA (Sigma) | L | 100 μL | One | 44 |

| Shen et al.,2021 China | Sprague Dawley | M | Adult | 7–8 weeks/ 250–300 g | CFA (Sigma) | L | 100 μL | One | 45 |

| Ariyo et al.,2022 Nigeria | Wistar | M | Adult | 180–220 g | CFA (Sigma) | R | 200 μL | One | 47 |

| Luo et al.,2022 China | Sprague Dawley | M | Adult | 200–250 g | CFA (Sigma) | L | 50 μL | One | 53 |

| Ma et al.,2022 China | Sprague Dawley | M | Adult | 6–8 weeks | CFA (Sigma) | L | / | One | 54 |

| Rahmani et al.,2022 Iran | Wistar | M | Adult | 90 days old/ 200–230 g | CFA (Sigma) | R | 100 μL | One | 57 |

| Spinieli et al.,2022 USA | Wistar | M | Adult | 200 g | CFA (Sigma) | R | 50 μL | One | 58 |

| Morales-Medina et al.,2023 Italy | Wistar | M | Adult | 2–3 months | CFA (Sigma) | L | 50 μL | One | 65 |

| Yang et al.,2023 China | Sprague Dawley | M | Adult | 8 weeks | CFA (Sigma) | L | 100 μL | One | 71 |

This study included 66 papers on pain-induced emotions and cognitive behaviors (Fig. 3), 54 evaluated only 1 pain-related behavioral outcome and 12 evaluated 2 pain-related behavioral outcomes. Among these studies, 52 evaluated pain and anxiety behaviors, 19 evaluated pain and depression behaviors, and 7 evaluated pain and cognitive impairment behaviors (Figure S1).

Fig. 3.

Summary of the methodological quality of included studies, assessed using the ARRIVE guidelines for the reporting of in vivo experiments. Summarized criteria: Title; Abstract; Background; Objectives; Ethical statement; Study design; Experimental procedures; Blinding; Experimental animals; Housing and husbandry; Sample size; Allocating animals to experimental groups; Experimental outcomes; Statistical methods; Baseline data; Numbers analyzed; Outcomes and estimation; Individual data points; Adverse events; Interpretation/scientific implications; Generalizability/translation; Funding. Green - Complete; Yellow - Incomplete; Orange - Non applicable or Absent.

Except for one study that did not explain the specific behavioral paradigm, the other studies used a variety of behavioral paradigms to evaluate harmful behavior, including paw withdrawal threshold (PWT), paw withdrawal latency (PWL), and paw edema (Fig. 2e). PWT was used in 52 articles, PWL in 30 and paw edema in 10.

This study utilized a variety of behavioral paradigms to assess anxiety-like emotions, including the open field (OF), elevated plus maze (EPM), elevated zero maze (EZM), light/dark box (LDB), novel suppressed feeding (NSF), and marble burying test (MBT) (Fig. 2f). A total of 41 articles used OF to assess anxiety-like emotions, 37 used EPM, 8 used EZM, 6 used LDB, 3 used NSF, and 2 used MBT.

Depression-like emotions were mainly categorized into two categories: pain-related aversion and pain-related depression. Pain-related aversion was assessed using four behavioral paradigms: conditioned place aversion (CPA), conditioned place preference (CPP), the place escape-avoidance paradigm (PEAP), and real-time location preference/real-time position aversion (RTPP/RTPA). Pain-related depression was assessed using the forced swim test (FST), sucrose preference test (SPT), and tail suspension test (TST) (Fig. 2g). The CPP and RTPP/RTPA paradigms were used in one article each, whereas the CPA and PEAP paradigms were used in two articles each. Eight studies used the FST paradigm, four used the SPT, and three used the TST.

Various paradigms were utilized for pain-related cognition, including novel object recognition (NOR), Y maze, puzzle test, object place recognition (OPR), and radial maze (RAM) (Fig. 2h). Three papers used the Y maze paradigm, the NOR and OPR paradigms were each used in two, and the puzzle test and RAM paradigm were each used in one.

Model characteristics

In all of the included studies, the animals were injected with CFA into their hind paws to establish an inflammatory pain model. There were 3 studies with double plantar injections and 63 studies with unilateral injections, including 19 studies on the right and 42 on the left. Additionally, two articles did not explain specific injection details (Fig. 2d). CFA produced by Sigma was used in all studies except for one, which did not record the source of the inflammatory agents. In some of the studies, an undiluted CFA stock solution was directly injected according to the dose; however, in most studies, emulsified forms were used. Specifically, CFA was mixed with normal saline or phosphate-buffered saline in a specific proportion, most commonly 1:1. The injection doses included in the studies ranged from 5 to 200 μL, including 10 μL and 20 μL for mice and 100 μL for rats (Table 1). Among the included studies, 64 induced chronic inflammation through a single injection, while 2 articles used double injections. The time interval for the second injection of CFA was usually 7 days after the first to prolong the duration of inflammation (Table 1).

Methodological quality

The overall mean score for methodological quality was 16.5 ± 2.0. The proportion of studies that met each criterion and the global score are presented in Fig. 3. A global rating of “strong” was attributed to studies with a mean score > 16 (59 %), “moderate” was13–16 (36 %) and “weak” was < 13 (5 %). Among the included studies, 39 had scores > 16, indicating high quality literature, while 24 were of medium quality. Three articles scored < 13, indicating low-quality literature. The overall quality of the included articles was relatively high.

Risk of bias

We used the SYRCLE RoB assessment tool for animal experiments to assess the risk of bias in the 66 included studies, the results of which are shown in Fig. 4, Fig. 5. Among the 66 included studies, 17 studies provided a description of random sequence generation, 2 did not generate random sequences, and the remaining articles did not specify. All of the studies reported baseline characteristics prior to the CFA injection; however, none reported allocation concealment. Among the included studies, 33 reported identical husbandry conditions, whereas 1 reported that the animals were not housed identically during the experiment, and 2 articles did not mention husbandry; 26 imposed blinding on animal breeders and researchers while the other articles did not mention it; and 14 studies reported that animals were randomly selected for outcome measurements while 9 were blinded to the outcome assessor. The risks of attrition bias, reporting bias, and other sources of bias were low in all of the included studies.

Fig. 4.

Risk of bias graph.

Fig. 5.

Risk of bias summary.

Nociceptive behaviors

Most studies found that CFA injections can reliably induce stable local inflammatory pain hypersensitivity, which typically lasts 3–4 weeks (Figure S2a). The significant decrease in PWT started as early as 1 hour post-injection and persisted until the fourth week post-CFA injection (Fig. 6a); however, 1 study indicated that CFA induced PWT in the first 2 weeks but had no effect in weeks 3–5 (Fig. 6a) (Pitzer et al., 2019). The PWT results were similar to those of the PWT during weeks 1–4 (Fig. 6b), and only 1 study reported that thermal pain occurred in the first week after CFA injection, which disappeared on the 10th day (Cardenas et al., 2021). Inflammatory pain was usually accompanied by paw swelling and edema for approximately 4 weeks after the CFA injection (Fig. 6c).

Fig. 6.

Heatmap summarizing of pain behavior. Green - Reporting of pain behavior; Red - No alterations in pain behavior observed; White - Not reported. a. The paw withdrawal threshold. b. The mean paw withdrawal latency. c. Paw edema evaluation.

Anxiety-like behaviors

Anxiety-like behaviors typically develop 1 or 3 days post-CFA induction, although they can also appear between 2–4 weeks post-CFA induction (Figure S3a). Of the six aforementioned tests for anxiety-like behavior, OF was used in 41 articles (Figs. 7a), 7 of which found no evidence of anxiety-like emotions post-CFA injection, while 1 only showed anxiety-like emotions but did not clarify the specific experimental time interval. One study reported anxiety at 4 hours post-CFA injection, while 10 observed anxiety-like behaviors at 1-week post-CFA, 10 at 2 weeks post-CFA, six studies at three weeks after CFA, and seven studies at four weeks after CFA (Fig. 7a). Additionally, EPM was utilized in 37 articles, with the majority focusing on the 2–4 weeks period following the CFA injection, demonstrating the consistent development of pain-related anxiety starting at 2 weeks post-injection (Fig. 7b). Similar to the OF paradigm, two articles reported the inability of CFA to induce pain-related anxiety using the EPM paradigm (Fig. 7b). EZM was used in 8 articles, with 2 articles observing anxiety-like behavior 1-week post-CFA, and the remaining 6 at week 4 (Figure S4a). LDB was utilized in 5 articles: 3 found no evidence of anxiety-like emotions post-CFA injection, 2 observed anxiety-like behavior at 1 week post-injection, and 1 observed anxiety-like behavior at 4 weeks post-injection (Figure S4b). NSF, which primarily measures the feeding latency of the experimental animals (Figure S4c), was utilized in 3 articles, and showed an increase in feeding latency at 28- and 31-day post-CFA injection, indicating anxiety-like behavior. Additionally, two studies utilized the MBT to evaluate anxiety-related behavior, specifically the burying behavior of rodents (Figure S4d). One article reported the presence of anxiety-like behavior at 5 weeks post-injection, whereas another study found no evidence of such behavior.

Fig. 7.

Heatmap summarizing of anxiety-like behavior. Green - Reporting of anxiety-like behavior; Red - No alterations in anxiety-like behavior observed; White - Not reported. a. The open field test. b. The elevated plus maze.

Depression -like behaviors

Two studies used CPA (Fig. 8a), which showed aversive behavior induced by CFA at 1–2weeks in mice, resulting in conditional place aversion (Fig. 8a). In contrast, CPP showed behavioral changes for 2 weeks post-CFA induction, indicating the presence of both conditional place preference and aversion 2 weeks post-CFA injection (Fig. 8b). Two additional articles utilized PEAP, in which the degree of pain aversion was evaluated based on the percentage of residence time in the open compartment of the testing box. Pain aversion was predominantly observed 1- and 10-days post-CFA injection (Fig. 8c). One study used the RTPP/RTPA paradigm, in which pain aversion was predominantly observed 3 days post-CFA injection (Fig. 8g).

Fig. 8.

Heatmap summarizing depressive-like behavior. Green - Reporting of depressive-like behavior; Red - No alterations in depressive-like behavior observed; White - Not reported. a. The conditioned place aversion. b. The conditioned place preference. c. The place escape-avoidance paradigm. d. The forced swim test. e. The sucrose preference test. f. The tail suspension test. g. Real-time place preference/Real-time place aversion.

The FST was used in eight studies that focused on depression-like emotions. The increased immobility time of FST post-CFA injection indicated the development of a depressive mood. Three articles did not observe pain-induced depression-like behavioral changes at the designated time points; however, 5 articles reported the presence of pain-related depression-like behavior at 7, 11, 14, 16, and 28 days (1–4weeks) post-CFA induction (Fig. 8d). Furthermore, four articles utilized the SPT to assess depression-like mood in experimental animals post-CFA injection (Fig. 8e), the results of which revealed a significant decrease in CFA-injected animals, indicating the development of depression and related anhedonia. Depression-like behavior mostly occurred within 4 weeks of CFA induction in the SPT (Fig. 8e). Two articles used the TST paradigm (Fig. 8f) with the primary parameter as immobility time, and depression-like behavior predominantly appeared within 3 weeks (Fig. 8f). Among all studies, pain aversion was primarily observed within 2 weeks, and pain depression within 4 weeks (Figure S3b).

Cognitive impairment

Among the eligible articles, two focused on the NOR paradigm, which assesses both spatial recognition and recognition memory in experimental animals (Fig. 9a). These studies revealed that impaired cognitive abilities were attributable to the pain experienced during the 1–4 weeks period post-CFA induction, and the discrimination index was used as the primary measurement in this paradigm (Fig. 9a). The Y-maze was utilized in 3 articles focusing on cognitive impairment, the results of which showed that spatial memory damage mostly occurred within 3 weeks (Fig. 9b). The puzzle test was used to assess the problem-solving abilities of the experimental animals with cognitive impairments observed 10 days post-CFA induction (Fig. 9c), two articles utilized the OPR (Fig. 9d); however, studies that utilized the RAM paradigm did not detect any cognitive deficits post-CFA induction (Fig. 9e). Overall, cognitive impairment mainly occurred within 2–4 weeks of CFA induction (Figure S2b).

Fig. 9.

Heatmap summarizing of cognitive impairment. Green - Reporting of cognitive impairment behavior; Red - No alterations in cognitive aspects observed; White - Not reported. a. The novel object recognition test. b. The Y maze test. c. The puzzle test. d. The object place recognition. e. The radial maze test.

Proposed mechanisms

Nucleus excitability

Many brain nuclei are involved in the comorbidities discussed herein including the amygdala, anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), hippocampus, medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), locus coeruleus (LC), thalamus, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), nucleus accumbens (NAc), periaqueductal gray (PAG) and rostral ventromedial medulla (RVM) (Table 2).

Table 2.

the mechanism of cerebral nuclei in comorbidity.

| Encephalic region | comorbidity | State | Mechanism | Ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amygdala | Amygdala | pain-anxiety | ↑ | 1. decreased global DNA methylation, 2. increased the NMDAR (p-GluN2B, GluN2B, GluN2A, PSD95, Synaptophysin) expressions, 3. increased the AMPAR (GluA1 p-GluA1), 4. increased the microglia activation, 5. increased the proinflammatory mediators (TNF-a, IL−1b) and NF-κB signaling pathway (p65, pIκBa) | 58, 35 |

| CeA | pain-anxiety | ↑ | 1. increased the frequency and the amplitude of mEPSC, 2. increased the GABAergic neurons (increased the PKCδ、SOM neurons). | 46, 68 | |

| BLA | pain-anxiety | ↑ | 1. increased CPEB1 expression, 2. shown in Fig10c | 8, 16, 19, 25, 31, 33, 65 | |

| pain-depression | ↑ | increased the c-Fos expression | 65 | ||

| ACC | ACC | pain-anxiety | ↑ | 1. activated the calcium homeostasis moduLator 2 (Calhm2) in pyramidal neurons, 2. shown in the Fig10b | 22, 28, 34, 43, 44, 48, 50, 52, 59 |

| rACC | pain-anxiety | ↑ |

|

54 | |

| hippocampus | hippocampus | pain-anxiety | ↑ | increased the BDNF level | 14 |

| pain-cognition | ↑ |

|

57 | ||

| pain-depression | ↓ | inhibited the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway (decreased of p-PI3K, PI3K, p-Akt, Akt proteins) →neuronal apoptosis (decreased Bcl−2 expression, increased Bax expression) | 71 | ||

| dorsal hippocampus | pain-cognition | ↑ | increased the endogenous PPAR ligands (PEA and OEA) levels | 41 | |

| vDG、dDG | pain-anxiety | ∕ | decreased the BDNF levels | 8 | |

| dDG | pain-cognition | impaired the neurogenesis | |||

| vCA1 | pain-anxiety | ↓ | pyramidal neurons showed inhibitory responses | 67 | |

| mPFC | pain-cognition | ↑ | 1. increased the dendritic spine density on pyramidal neurons in the mPFC of male mice but not in female mice, 2. increased the dendritic spine density on interneurons in the mPFC of male and female mice, 3. CFA injection decreased the expression of the glutamate transporter VGlut1 on the soma of mPFC neurons. | 56 | |

| pain-anxiety | ↑ | increased the c-Fos expression | 62 | ||

| vmPFC | pain-anxiety | ↑ | enhanced AMPAR trafficking and synaptic transmission | 61 | |

| PL | pain-anxiety | ↓ | decreased the excitatory neurons | 15 | |

| BNST | pain-anxiety | ↑ | increased the c-Fos expression | 62 | |

| LC | pain-anxiety | ↑ | increased the c-Fos expression | 39 | |

| pain-cognition | |||||

| thalamus | pain-anxiety | ↑ | increased the NR2B expression | 51 | |

| NAc | pain-depression | ↑ | increased the GluA1 expression | 17 | |

| PAG | pain-depression, pain-anxiety | ↑ | increased the c-Fos expression | 65 | |

| RVM | ↑ | ||||

The amygdala includes the central amygdala (CeA) and basolateral amygdala (BLA), and CeA contributed to pain-anxiety comorbidity by increasing the frequency and the amplitude of miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) and by shifting the excitability balance between protein kinase C-delta (PKCδ+) and somatostatin (SOM+) neurons. The BLA is involved in the pain-anxiety comorbidity through several mechanisms, including increasing neurotransmitter release, enhancing neuroplasticity, shifting the excitation/inhibition (E/I) balance, and promoting neuroinflammation. Specifically, studies have shown that the BLA is overactive in pain comorbidity, and its connections with other brain regions, such as the ACC, are strengthened. Additionally, neuroinflammation in the BLA, driven by astrocyte activation, can enhance glutamate receptor trafficking and synaptic transmission, thereby exacerbating pain-related anxiety (Fig. 10c, Table 2). It also participates in the pain-depression comorbidity by increasing c-Fos expression (Table 2).

Fig. 10.

Mechanism diagram.

The ACC is involved in pain-anxiety comorbidities, with potential mechanisms including enhanced neuronal excitability, increased excitatory transmission/excitatory presynaptic transmission, increased synaptic plasticity, increased E/I balance, increased neuroinflammation, and decreased inhibitory presynaptic transmission (Sun et al., 2016, Guo et al., 2018, Du et al., 2020, Shao et al., 2021a, Shao et al., 2021b, Chen et al., 2022a, Darvish-Ghane et al., 2022, Li et al., 2022, Wang et al., 2022, Zhou et al., 2022, Li et al., 2023) (Fig. 10b, Table 2).The Pain-anxiety comorbidity was also associated with calcium homeostasis modulator 2 in the pyramidal neurons of the ACC.

The hippocampus plays an important role in pain-anxiety, pain-depression, and pain-cognitive comorbidities. In the pain-anxiety comorbidity, brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels increased in the whole hippocampus but decreased in the ventral and dorsal dentate gyri (vDG and dDG), while pyramidal neurons in ventral hippocampal vCA1 showed inhibitory responses. In the pain-depression comorbidity, the animals exhibited inhibition of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/Akt) signaling pathway (decreased levels of p-PI3K, PI3K, p-Akt, and Akt proteins) and increased neuronal apoptosis (decreased B-cell lymphoma 2 [Bcl-2] expression and increased Bcl-2 associated X-protein [Bax] expression) in the hippocampus. In the pain-recognition comorbidity group, endogenous peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor ligand (palmitoylethanolamide and oleoylethanolamide) levels were increased in the dorsal hippocampus (Table 2).

The mPFC is involved in pain-cognition comorbidity by increasing dendritic spine density in pyramidal neurons of male, but not in female, mice, increasing dendritic spine density in the interneurons of male and female mice, and decreasing the expression of the glutamate transporter VGlut1 in the soma of mPFC neurons. Animals with pain-anxiety comorbidities showed increased c-Fos expression in the mPFC, enhanced α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor (AMPAR) trafficking and synaptic transmission in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, and decreased excitatory neurons in the prelimbic cortex (Table 2).

The LC is involved in the comorbidities of pain-anxiety and pain-recognition by increasing c-Fos expression (Table 2); the thalamus is involved in the pain-anxiety comorbidity by increasing N-methyl D-aspartate (NDMA) receptor subtype 2B expression (Table 2); BNST is involved in the pain-anxiety comorbidity by increasing c-Fos expression (Table 2); the NAc is involved in pain-depression through an increase in glutamate A1 expression (Table 2); and the PAG and RVM are involved in the comorbidity of pain anxiety and pain-depression by increasing c-Fos expression (Table 2).

Neural circuits

As shown in Fig. 10a, the primary somatosensory cortex (S1)Glu→caudal dorsolateral striatum (cDLS)GABA(Jin et al., 2020), medial septum (MS)CHAT→rACC (Jiang et al., 2018), rACCGlu→thalamus (Shen et al., 2020), parabrachial nucleus (PBN)→CeA (Zhou et al., 2021), mediodorsal thalamus (MD)→BLA, insular cortex (IC)→BLA (Meng et al., 2022), and anteromedial thalamus nucleus (AM)CaMKⅡ→midcingulate cortex (MCC)CaMKⅡ pathways (Hong et al., 2023) are enhanced in the pain-anxiety comorbidity, whereas the ventral hippocampal CA1 (vCA1)→BLA (Shao et al., 2023) and BLA→CeA pathways (Zhou et al., 2021) are decreased. The BLA→ACC pathway is enhanced in the pain-depression comorbidity. In the pain-cognition comorbidity, the infralimbic cortex (IL)→LC pathway is enhanced (Cardenas et al., 2021), whereas the vCA1→IL pathway is decreased (Shao et al., 2023).

Inflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis

Inflammation

In both the pain-anxiety and pain-depression comorbidities, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and interleukin (IL)-6 expression were increased in the joints, plasma/serum, spinal cord, and cortex. IL-1β expression was increased in hippocampus and amygdala, although it did not change in spinal cord and cortex. Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) expression increased in the joints and cortex, while nuclear factor kappa B and phospho-IkB-alpha expression increased in the paws and amygdala (Table 3).

Table 3.

inflammation, oxidative stress and apoptosis and comorbidity.

| Mechanism | Paw | Joint | Plasma/Serum |

Brain |

Liver | Spinal cord | Reference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortex | hippocampus | amygdala | Whole brain | |||||||

| Inflammation | ||||||||||

| TNF-α | / | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | / | / | / | / | ↑ | 22, 30, 35, 47, 59, 66, 69 |

| IL−6 | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | 22, 30, 47, 59, 66, 69 | |||||

| IL−1β | / | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↔ | 35, 59, 66, 57 | ||||

| / | ↔ | / | / | / | 12 | |||||

| COX−2 | ↑ | ↑ | 12, 47 | |||||||

| NF-kB | ↑ | / | / | ↑ | 33, 35, 49 | |||||

| p-IKBa | ↑ | ↑ | 49 | |||||||

| Oxidative stress | ||||||||||

| MDA | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | / | / | / | ↑ | ↑ | / | 30, 47 |

| SOD | / | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | 30, 47 | ||||

| GSH | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | 30, 47 | ||||

| Nitrite | ↑ | / | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | 47 | ||||

| MPO | ↓ | / | / | / | 47 | |||||

| 4-HNE | ↑ | ↑ | 49 | |||||||

| Apoptotic | ||||||||||

| Bcl−2-like protein 4 | ↑ | / | / | / | ↓ | ↑ | / | / | / | 49 |

| BAX | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | 49, 59 | ||||||

Oxidative stress

In both the pain-anxiety and pain-depression comorbidities, malondialdehyde (MDA) levels increased in the paws, joints, plasma/serum, liver, and whole brain. SOM levels increased in the joints and decreased in the plasma/serum, liver, and whole brain. Glutathione levels increased in the joints and decreased in the paws, plasma/serum, liver, and whole brain, whereas nitrite levels increased in the paws, plasma/serum, whole brain, and liver. Myeloperoxidase levels decreased in the paws, and 4-hydroxynonenal levels decreased in the paws and amygdala (Table 3).

Apoptosis

In both the pain-anxiety and pain-depression comorbidities, Bcl-2 like protein 4 increased in the paws and amygdala, and decreased in the hippocampus, whereas BAX levels increased in the paws, hippocampus, and amygdala (Table 3). The pain-cognition comorbidity in animals enhanced the production of hippocampal IL-1β and increased hippocampal apoptosis and necroptosis (caspase-8, caspase-3, and Rip3 increased)(Rahmani et al., 2022).

Other

Ferroptosis, the gut-brain axis, and gut microbiota dysbiosis are also involved in the aforementioned comorbidities. Animals with pain-anxiety comorbidities had increased ferroptosis mainly because of decreased ferritin heavy chain 1 mRNA and glutathione peroxidase 4 mRNA expression in the ACC and lumbar vertebrae 4–5 (L4–5) dorsal root ganglia (DRG), and increased expression of Heme oxygenase-1 mRNA and prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 mRNA in the ACC and L4–5 DRG (Chen et al., 2022a). The abnormal composition of gut microbiota plays an essential role in the chronic pain-anxiety comorbidity. At the phylum level, Campilobacterota is decreased (Wu et al., 2023); at the class level, Campylobacteria is decreased; at the order level, Campylobacterales is decreased; at the family level, Butyricicoccaceae is increased and Marinifilaceae is decreased; at the genus level, Alistipes, Christensenellaceae R 7 group, Desulfovibrio, Helicobacter, and Rikenella are decreased; and at the species level, gut metagenome g [Eubacterium] coprostanoligenes group was increased but Helicobacter hepaticus g Helicobacter was reduced. It has also been reported that jejunal villus length is decreased in the pain-anxiety comorbidity (Chen et al., 2022a). The gut–microbiota–brain axis via the subdiaphragmatic vagus nerve is crucial for the development of pain-cognition comorbidities in CFA mice (Yue et al., 2023).

Discussion

This study provides a comprehensive overview of the development of pain-related negative emotional and cognitive impairment in a CFA-induced chronic inflammatory pain model. Through this review, we observed that pain behaviors, including mechanical pain, thermal pain, and paw swelling, were evident as early as 1-hour post-CFA injection and persisted for at least 2 weeks. Anxiety-like behaviors can develop sooner, at 1- or 3-days post-CFA induction, but can also appear between 2–4 weeks post-CFA induction. While pain aversion was primarily observed within 2 weeks of induction, pain depression was primarily observed within 4 weeks, and cognitive impairment mainly occurred within the 2–4 weeks of CFA induction. Understanding the inflammatory pain induced by CFA involves the consideration of pain sensations, negative emotions, and cognitive impairments. This holistic approach enhances the clinical comprehension of pain management and facilitates the development of more effective treatment strategies.

Based on our inclusion/exclusion criteria, the overall quality of the included studies was relatively high; however, there are still some limitations. Many of the experimental studies failed to accurately describe randomization and blinding procedures for result assessment and had incomplete descriptions of the study designs, leading to unclear experimental designs. While these studies may have had influential results for their primary research questions, their limitations also increased the risk of bias and served as significant limiting factors for subsequent researchers to reference and learn from. Future studies should provide more detailed information regarding randomization, blinding, and experimental designs to provide more objective indicators for other researchers.

Male rodents are widely used as chronic inflammatory pain models; however, at present, there are few reports on female animals. In clinical practice, however, the pain-emotion and pain-cognition comorbidities are not exclusive to male patients (De Ridder et al., 2021). Therefore, future studies investigating the induction of emotional and cognitive comorbidities in patients with chronic inflammatory pain should consider sex-related confounding factors. Various doses of CFA and their different emulsions have been used to induce chronic inflammatory pain. Therefore, studies are needed to explore the effects of inflammatory agent doses and ratios to ensure reduced variability in experimental results and a better approximation of the clinical changes induced by pain. Although the studies included in this review primarily utilized well-known behavioral paradigms, the application of these paradigms varied depending on the different experimental groups and designs, such as different testing equipment, experimental environments, and testing times. To some extent, this contributed to the variability in the experimental results.

A previous systematic review quantified the effects of CFA on nine commonly used behavioral measures of pain reduction, which focused on understanding behavioral paradigms as well as the creative development of new behavioral paradigms (Burek et al., 2022). Our study, however, summarized the development of anxiety- and depression-like behaviors and the impairment of cognitive function in a CFA-based model of chronic inflammatory pain. Because a single variable can easily produce different results between tests on the same animal, the included studies were refined, that is, the refinement analysis included the animal species as well as the behavioral paradigms. Additionally, our study focused on summarizing the main mechanisms of CFA-induced pain associated with anxiety, depression, and cognitive dysfunction. It is helpful to deepen the understanding of chronic inflammatory pain and emotional-cognitive comorbidities caused by CFA, provide convenience for experimental research, and provide new ideas for the clinical comorbidities of chronic pain, mood, and cognitive disorders. Several brain regions, such as the ACC, mPFC, dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN), NAc, and CeA, have been implicated in the comorbidities of affective disorders in chronic pain (Zhou et al., 2019, Massaly et al., 2019, Koga et al., 2015, Fanton et al., 2023, Doan et al., 2015, Goffer et al., 2013). In this study, we found that the LC, BNST, PAG, and RVM were also involved in comorbidities (Fig. 10a). Multiple pathways, including DRN→CeA→lateral habenular nucleus (Zhou et al., 2019, Chen et al., 2022b), thalamus→ACC (Koga et al., 2015, Zhang et al., 2017), LC→ACC (Llorca-Torralba et al., 2022), BNST→lateral hypothalamus (Yamauchi et al., 2022), VTADA→mPFC→vlPAG, ACCGlu→VTAGABA→VTADA→ACCGlu (Song et al., 2024), and DRN5-HT→CeASOM75 have been reported to be involved in comorbid emotional changes during the development of chronic pain. In this study, we found that different neural circuits were involved in the pain-anxiety, pain-depression, and pain-cognitive comorbidities. In the pain-anxiety comorbidity, the MSchat→ACC, rACCGlu→MD, AMGlu→MCCGlu, MDGlu→BLAGlu, ICGlu→BLAGlu, PBNGlu→CeA, and S1Glu→cDLs pathways were excited, whereas BLAGlu→CeA, and vCA→BLA pathways were inhibited. In the pain-depression comorbidity, thalamus→ACC and thalamus→BLA pathways were activated. In the pain-cognitive comorbidity, the IL→LC pathway was stimulated, whereas the vCA→IL pathway was suppressed (Fig. 10a).

The ACC and BLA are pivotal nuclei involved in the comorbidities of pain-anxiety, depression, and cognition induced by CFA. In addition to their associated neural circuits, microglia are necessary for the initiation and perpetuation of comorbidities. Activated microglia release pro-inflammatory factors and chemokines, thereby activating AMPA and NMDA receptors, C-C motif chemokine receptor 2, and chemokine receptor in neurons. Additionally, microglia trigger the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Together, these processes lead to enhanced excitatory transmission, excitatory presynaptic activity, synaptic plasticity, and decreased inhibitory presynaptic activity in neurons (Fig. 10b, c).

In 1988, Stein et al. (1988). published a study on the CFA-based induction of inflammatory pain in the unilateral hind paws of rats. The advantage of this model lies in its ability to simulate inflammatory responses and pain behaviors when CFA is injected. Importantly, as the CFA is injected into the distal limb, this model does not result in severe chronic systemic diseases. Furthermore, the simplicity and ease of the intraplantar injection into the hind paw have made this model highly popular among experimental researchers. The CFA model, however, has notable limitations. Animals and humans have inherent differences in their perception of pain, and animals lack the ability to describe the intensity of their pain (MuLey et al., 2016). Therefore, they can only manifest pain sensitivity through behavioral signs of distress or withdrawal reflexes in response to harmful stimuli. In contrast, human pain encompasses various aspects including emotion, cognition, affect, and sociopsychological components. As such, comorbidities are an essential part of human disease, necessitating further exploration using the CFA model to encompass the diverse characteristics of human pain states and enrich the model’s content.

Conclusion

This review has highlighted the emergence of an anxiodepression-like phenotype accompanied by cognitive impairment in CFA-treated animals. Potential mechanisms for these comorbidities primarily involve heightened neuronal excitability, enhanced excitatory synaptic transmission, neuroinflammation, and alterations in neural circuits. Inflammation, oxidative stress, apoptosis, ferroptosis, gut-brain axis dysfunction, and gut microbiota dysbiosis also contribute to these comorbidities.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Fund of China (82374561, 82174490, 81873360), the Zhejiang Medical and Health Science and Technology Program (2021RC098), the Research Project of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University (2022JKZKTS44).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Fang Jianqiao: Supervision. Shao Xiaomei: Software. Du Jun-ying: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Conceptualization. Fang Junfan: Data curation. Ren Junhui: Visualization, Methodology. Ye Ru: Software. Liang Yi: Supervision. Guan Lu: Writing – original draft. Guo Zi: Data curation. Wei Naixuan: Writing – original draft, Data curation.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

We appreciate the technical support from the Public Platform of Medical Research Center, Academy of Chinese Medical Science, Zhejiang Chinese Medical University.

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

Contributions

Jianqiao Fang, Junfan Fang and Junying Du contributed to the study of conception and design. Zi Guo, Ru Ye, Lu Guan, Junhui Ren, Yi Liang and Xiaomei Shao contributed to the acquisition and the analysis of data. Naixuan Wei drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.ibneur.2025.02.015.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

References

- Ariyo O.O., Ajayi A.M., Ben-Azu B., Aderibigbe A.O. Morus mesozygia leaf extract ameliorates behavioral deficits, oxidative stress and inflammation in complete Freund’s adjuvant-induced arthritis in rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022;292 doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2022.115202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baiamonte B.A., Lee F.A., Gould H.J., Soignier R.D. Morphine-induced cognitive impairment is attenuated by induced pain in rats. Behav. Neurosci. 2013;127(4):524–534. doi: 10.1037/a0033027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges G., Miguelez C., Neto F., Mico J.A., Ugedo L., Berrocoso E. Activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK 1/2) in the locus coeruleus contributes to pain-related anxiety in arthritic male rats. Int J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;20(6):463. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyx005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burek D.J., Massaly N., Yoon H.J., Doering M., Morón J.A. Behavioral outcomes of complete Freund adjuvant-induced inflammatory pain in the rodent hind paw: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain. 2022;163(5):809–819. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushnell M.C., Čeko M., Low L.A. Cognitive and emotional control of pain and its disruption in chronic pain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013;14(7):502–511. doi: 10.1038/nrn3516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardenas A., Papadogiannis A., Dimitrov E. The role of medial prefrontal cortex projections to locus ceruLeus in mediating the sex differences in behavior in mice with inflammatory pain. FASEB J. 2021;35(7) doi: 10.1096/fj.202100319RR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazuza R.A., Arantes A.L.F., Pol O., Leite-Panissi C.R.A. HO-CO pathway activation may be associated with hippocampal μ and δ opioid receptors in inhibiting inflammatory pain aversiveness and nociception in WT but not NOS2-KO mice. Brain Res. Bull. 2021;169:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbuLl.2021.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W.H., Lien C.C., Chen C.C. Neuronal basis for pain-like and anxiety-like behaviors in the central nucleus of the amygdala. Pain. 2022;163(3):e463–e475. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z.J., Su C.W., Xiong S., et al. Enhanced AMPAR-dependent synaptic transmission by S-nitrosylation in the vmPFC contributes to chronic inflammatory pain-induced persistent anxiety in mice. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2023;44(5):954–968. doi: 10.1038/s41401-022-01024-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Wang J., He Z., Liu X., Liu H., Wang X. Analgesic and anxiolytic effects of gastrodin and its influences on ferroptosis and jejunal microbiota in complete Freund’s adjuvant-injected mice. Front. Microbiol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.841662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coderre T.J., Laferrière A. The emergence of animal models of chronic pain and logistical and methodological issues concerning their use. J. Neural Transm. 2020;127(4):393–406. doi: 10.1007/s00702-019-02103-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S.P., Vase L., Hooten W.M. Chronic pain: an update on burden, best practices, and new advances. Lancet. 2021;397(10289):2082–2097. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00393-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coral-Pérez S., Martínez-Martel I., Martínez-Serrat M., et al. Treatment with hydrogen-rich water improves the nociceptive and anxio-depressive-like behaviors associated with chronic inflammatory pain in mice. Antioxidants. 2022;11(11):2153. doi: 10.3390/antiox11112153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darvish-Ghane S., Lyver B., Facciol A., Chatterjee D., Martin L.J. Inflammatory pain alters dopaminergic modulation of excitatory synapses in the anterior cingulate cortex of mice. Neuroscience. 2022;498:249–259. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2022.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Ridder D., Adhia D., Vanneste S. The anatomy of pain and suffering in the brain and its clinical implications. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021;130:125–146. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doan L., Manders T., Wang J. Neuroplasticity underlying the comorbidity of pain and depression. Neural Plast. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/504691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J., Fang J., Xu Z., et al. Electroacupuncture suppresses the pain and pain-related anxiety of chronic inflammation in rats by increasing the expression of the NPS/NPSR system in the ACC. Brain Res. 2020;1733 doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2020.146719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang S., Qin Y., Yang S., et al. Differences in the neural basis and transcriptomic patterns in acute and persistent pain-related anxiety-like behaviors. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2023;16 doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2023.1185243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanton S., Menezes J., Krock E., et al. Anti-satellite glia cell IgG antibodies in fibromyalgia patients are related to symptom severity and to metabolite concentrations in thalamus and rostral anterior cinguLate cortex. Brain Behav. Immun. 2023;114:371–382. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2023.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca-Rodrigues D., Amorim D., Almeida A., Pinto-Ribeiro F. Emotional and cognitive impairments in the peripheral nerve chronic constriction injury model (CCI) of neuropathic pain: a systematic review. Behav. Brain Res. 2021;399 doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2020.113008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar J.C., Healy C., Ferdousi M.I., Roche M., Finn D.P. Pharmacological blockade of PPARα exacerbates inflammatory pain-related impairment of spatial memory in rats. Biomedicines. 2021;9(6):610. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9060610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffer Y., Xu D., Eberle S.E., et al. Calcium-permeable AMPA receptors in the nucleus accumbens reguLate depression-like behaviors in the chronic neuropathic pain state. J. Neurosci. 2013;33(48):19034–19044. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2454-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan S.Y., Zhang K., Wang X.S., et al. Anxiolytic effects of polydatin through the blockade of neuroinflammation in a chronic pain mouse model. Mol. Pain. 2020;16 doi: 10.1177/1744806919900717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo B., Wang J., Yao H., et al. Chronic inflammatory pain impairs mGluR5-mediated depolarization-induced suppression of excitation in the anterior cingulate cortex. Cereb. Cortex. 2018;28(6):2118–2130. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhx117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H.L., Xiao Y., Tian Z., et al. Anxiolytic effects of sesamin in mice with chronic inflammatory pain. Nutr. Neurosci. 2016;19(6):231–236. doi: 10.1179/1476830515Y.0000000015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann F.R., Zago A.M., Rossato M.F., et al. Antinociceptive and antidepressant-like effects of the crude extract of Vitex megapotamica in rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016;192:210–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann L., Karl F., Sommer C., Üçeyler N. Affective and cognitive behavior in the alpha-galactosidase A deficient mouse model of Fabry disease. PLOS One. 2017;12(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong J., Li J.N., Wu F.L., et al. Projections from anteromedial thalamus nucleus to the midcingulate cortex mediate pain and anxiety-like behaviors in mice. Neurochem. Int. 2023;171 doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2023.105640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- J T., Z T., Sl Q., Py Z., X J., Z T. Anxiolytic-like effects of α-asarone in a mouse model of chronic pain. Metab. Brain Dis. 2017;32(6) doi: 10.1007/s11011-017-0108-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y.Y., Zhang Y., Cui S., Liu F.Y., Yi M., Wan Y. Cholinergic neurons in medial septum maintain anxiety-like behaviors induced by chronic inflammatory pain. Neurosci. Lett. 2018;671:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.neuLet.2018.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S., Zheng C., Wen G., Bu B., Zhao S., Xu X. Down-reguLation of NR2B receptors contributes to the analgesic and antianxiety effects of enriched environment mediated by endocannabinoid system in the inflammatory pain mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2022;435 doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2022.114062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y., Meng Q., Mei L., et al. A somatosensory cortex input to the caudal dorsolateral striatum controls comorbid anxiety in persistent pain. Pain. 2020;161(2):416–428. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga K., Descalzi G., Chen T., et al. Coexistence of two forms of LTP in ACC provides a synaptic mechanism for the interactions between anxiety and chronic pain. Neuron. 2015;85(2):377–389. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laumet G., Edralin J.D., Dantzer R., Heijnen C.J., Kavelaars A. CD3+ T cells are critical for the resolution of comorbid inflammatory pain and depression-like behavior. Neurobiol. Pain. 2020;7 doi: 10.1016/j.ynpai.2020.100043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A.M., Su M., Zou C., Wang A. J. AMPAkines have novel analgesic properties in rat models of persistent neuropathic and inflammatory pain. Anesthesiology. 2014;121(5):1080–1090. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Ni K., Qi M., Li J., Yang K., Luo Y. The anterior cinguLate cortex contributes to the analgesic rather than the anxiolytic effects of duLoxetine in chronic pain-induced anxiety. Front. Neurosci. 2022;16 doi: 10.3389/fnins.2022.992130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Xiong M., Gao Y., Xu X., Ke C. UpreguLation of Calhm2 in the anterior cinguLate cortex contributes to the maintenance of bilateral mechanical allodynia and comorbid anxiety symptoms in inflammatory pain conditions. Brain Res. Bull. 2023;204 doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbuLl.2023.110808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima M., Malheiros J., Negrigo A., et al. Sex-related long-term behavioral and hippocampal celluLar alterations after nociceptive stimulation throughout postnatal development in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2014;77:268–276. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Huang X., Xu J., et al. Dissection of the relationship between anxiety and stereotyped self-grooming using the Shank3B mutant autistic model, acute stress model and chronic pain model. Neurobiol. Stress. 2021;15 doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2021.100417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorca-Torralba M., Camarena-Delgado C., Suárez-Pereira I., et al. Pain and depression comorbidity causes asymmetric plasticity in the locus coeruLeus neurons. Brain. 2022;145(1):154–167. doi: 10.1093/brain/awab239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo H., Zhang Y., Zhang J., et al. Glucocorticoid receptor contributes to electroacupuncture-induced analgesia by inhibiting Nav1.7 expression in rats with inflammatory pain induced by complete Freund’s adjuvant. NeuromoduLation. 2022;25(8):1393–1402. doi: 10.1111/ner.13499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y., Qin G.H., Guo X., et al. Activation of δ-opioid receptors in anterior cingulate cortex alleviates affective pain in rats. Neuroscience. 2022;494:152–166. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2022.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maciel I.S., Silva R.B.M., Morrone F.B., Calixto J.B., Campos M.M. Synergistic effects of celecoxib and bupropion in a model of chronic inflammation-related depression in mice. PLOS One. 2013;8(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massaly N., Copits B.A., Wilson-Poe A.R., et al. Pain-induced negative affect is mediated via recruitment of the nucleus accumbens Kappa opioid system. Neuron. 2019;102(3):564–573.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X., Yue L., Liu A., et al. Distinct basolateral amygdala excitatory inputs mediate the somatosensory and aversive-affective components of pain. J. Biol. Chem. 2022;298(8) doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2022.102207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Medina J.C., Bautista-Carro M.A., Serrano-Bello G., Sánchez-Teoyotl P., Vásquez-Ramírez A.G., Iannitti T. Persistent peripheral inflammation and pain induces immediate early gene activation in supraspinal nuclei in rats. Behav. Brain Res. 2023;446 doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2023.114395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MuLey M.M., Krustev E., McDougall J.J. Preclinical assessment of inflammatory pain. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2016;22(2):88–101. doi: 10.1111/cns.12486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita M., Kaneko C., Miyoshi K., et al. Chronic pain induces anxiety with concomitant changes in opioidergic function in the amygdala. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31(4):739–750. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omorogbe O., Ajayi A.M., Ben-Azu B., et al. Jobelyn® attenuates inflammatory responses and neurobehavioural deficits associated with complete Freund-adjuvant-induced arthritis in mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018;98:585–593. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.12.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadogiannis A., Dimitrov E. A possible mechanism for development of working memory impairment in male mice subjected to inflammatory pain. Neuroscience. 2022;503:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2022.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent A.J., Beaudet N., Beaudry H., et al. Increased anxiety-like behaviors in rats experiencing chronic inflammatory pain. Behav. Brain Res. 2012;229(1):160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitzer C., La Porta C., Treede R.D., Tappe-Theodor A. Inflammatory and neuropathic pain conditions do not primarily evoke anxiety-like behaviours in C57BL/6 mice. Eur. J. Pain. 2019;23(2):285–306. doi: 10.1002/ejp.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahmani N., Mohammadi M., Manaheji H., et al. Carbamylated erythropoietin improves recognition memory by moduLating microglia in a rat model of pain. Behav. Brain Res. 2022;416 doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2021.113576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raja S.N., Carr D.B., Cohen M., et al. The revised international association for the study of pain definition of pain: concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain. 2020;161(9):1976–1982. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Refsgaard L.K., Hoffmann-Petersen J., Sahlholt M., Pickering D.S., Andreasen J.T. Modelling affective pain in mice: Effects of inflammatory hypersensitivity on place escape/avoidance behaviour, anxiety and hedonic state. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2016;262:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2016.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong Z., Yang L., Chen Y., et al. Sophoridine alleviates hyperalgesia and anxiety-like behavior in an inflammatory pain mouse model induced by complete freund’s adjuvant. Mol. Pain. 2023;19 doi: 10.1177/17448069231177634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da SA J., E B, UL J, et al. Anti-nociceptive, anti-hyperalgesic and anti-arthritic activity of amides and extract obtained from Piper amalago in rodents. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016;179 doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao F., Fang J., Qiu M., et al. Electroacupuncture ameliorates chronic inflammatory pain-related anxiety by activating PV interneurons in the anterior cingulate cortex. Front. Neurosci. 2021;15 doi: 10.3389/fnins.2021.691931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao F.B., Fang J.F., Wang S.S., et al. Anxiolytic effect of GABAergic neurons in the anterior cinguLate cortex in a rat model of chronic inflammatory pain. Mol. Brain. 2021;14(1):139. doi: 10.1186/s13041-021-00849-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao S., Zheng Y., Fu Z., et al. Ventral hippocampal CA1 moduLates pain behaviors in mice with peripheral inflammation. Cell Rep. 2023;42(1) doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheahan T.D., Siuda E.R., Bruchas M.R., et al. Inflammation and nerve injury minimally affect mouse voluntary behaviors proposed as indicators of pain. Neurobiol. Pain. 2017;2:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ynpai.2017.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Z., Zhang H., Wu Z., et al. Electroacupuncture alleviates chronic pain-induced anxiety disorders by regulating the rACC-thalamus circuitry. Front. Neurosci. 2020;14 doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.615395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi P., Zhang M.J., Liu A., et al. Acid-sensing ion channel 1a in the central nucleus of the amygdala reguLates anxiety-like behaviors in a mouse model of acute pain. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2022;15 doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2022.1006125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Q., Wei A., Xu H., et al. An ACC–VTA–ACC positive-feedback loop mediates the persistence of neuropathic pain and emotional consequences. Nat. Neurosci. 2024 doi: 10.1038/s41593-023-01519-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinieli R.L., Cazuza R.A., Sales A.J., et al. Persistent inflammatory pain is linked with anxiety-like behaviors, increased blood corticosterone, and reduced global DNA methylation in the rat amygdala. Mol. Pain. 2022;18 doi: 10.1177/17448069221121307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein C., Millan M.J., Herz A. Unilateral inflammation of the hindpaw in rats as a model of prolonged noxious stimuLation: alterations in behavior and nociceptive thresholds. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1988;31(2):445–451. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(88)90372-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su C., D’amour J., Lee M., et al. Persistent pain alters AMPA receptor subunit levels in the nucleus accumbens. Mol. Brain. 2015;8:46. doi: 10.1186/s13041-015-0140-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun T., Wang J., Li X., et al. Gastrodin relieved complete Freund’s adjuvant-induced spontaneous pain by inhibiting inflammatory response. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2016;41:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2016.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban R., Scherrer G., Goulding E.H., Tecott L.H., Basbaum A.I. Behavioral indices of ongoing pain are largely unchanged in male mice with tissue or nerve injury-induced mechanical hypersensitivity. Pain. 2011;152(5):990–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villemure C., Bushnell C.M. Cognitive modulation of pain: how do attention and emotion influence pain processing? Pain. 2002;95(3):195–199. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G.Q., Cen C., Li C., et al. Deactivation of excitatory neurons in the prelimbic cortex via Cdk5 promotes pain sensation and anxiety. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7660. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.S., Guan S.Y., Liu A., et al. Anxiolytic effects of Formononetin in an inflammatory pain mouse model. Mol. Brain. 2019;12(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s13041-019-0453-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.S., Jiang Y.L., Lu L., et al. Activation of GIPR exerts analgesic and anxiolytic-like effects in the anterior cingulate cortex of mice. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.887238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.T., Lu K., Yao D.D., Zhang S.X., Chen G. Anti-inflammatory and analgesic effect of Forsythiaside B on complete Freund’s adjuvant-induced inflammatory pain in mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2023;645:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2023.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D.S., Tian Z., Guo Y.Y., et al. Anxiolytic-like effects of translocator protein (TSPO) ligand ZBD-2 in an animal model of chronic pain. Mol. Pain. 2015;11:16. doi: 10.1186/s12990-015-0013-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z., Liu H., Yan E., et al. DesuLfovibrio confers resilience to the comorbidity of pain and anxiety in a mouse model of chronic inflammatory pain. Psychopharmacology. 2023;240(1):87–100. doi: 10.1007/s00213-022-06277-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Yao X., Jiang Y., et al. Pain aversion and anxiety-like behavior occur at different times during the course of chronic inflammatory pain in rats. J. Pain. Res. 2017;10:2585–2593. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S139679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi N., Sato K., Sato K., et al. Chronic pain-induced neuronal plasticity in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis causes maladaptive anxiety. Sci. Adv. 2022;8(17) doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abj5586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P., Chen H., Wang T., et al. Electroacupuncture attenuates chronic inflammatory pain and depression comorbidity by inhibiting hippocampal neuronal apoptosis via the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Neurosci. Lett. 2023;812 doi: 10.1016/j.neuLet.2023.137411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue C., Luan W., Gu H., et al. The role of the gut-microbiota-brain axis via the subdiaphragmatic vagus nerve in chronic inflammatory pain and comorbid spatial working memory impairment in complete Freund’s adjuvant mice. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2023;166:61–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2023.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue J., Wang X.S., Guo Y.Y., et al. Anxiolytic effect of CPEB1 knockdown on the amygdala of a mouse model of inflammatory pain. Brain Res. Bull. 2018;137:156–165. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbuLl.2017.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Chen C., Qi J. Activation of HDAC4 and GR signaling contributes to stress-induced hyperalgesia in the medial prefrontal cortex of rats. Brain Res. 2020;1747 doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2020.147051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Manders T., Tong A.P., et al. Chronic pain induces generalized enhancement of aversion. eLife. 2017;6 doi: 10.7554/eLife.25302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J., Jiang Y.Y., Xu L.C., et al. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis along the dorsoventral axis contributes differentially to environmental enrichment combined with voluntary exercise in alleviating chronic inflammatory pain in mice. J. Neurosci. 2017;37(15):4145–4157. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3333-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W., Jin Y., Meng Q., et al. A neural circuit for comorbid depressive symptoms in chronic pain. Nat. Neurosci. 2019;22(10):1649–1658. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0468-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W., Li Y., Meng X., et al. Switching of delta opioid receptor subtypes in central amygdala microcircuits is associated with anxiety states in pain. J. Biol. Chem. 2021;296 doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.100277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y.S., Meng F.C., Cui Y., et al. ReguLar aerobic exercise attenuates pain and anxiety in mice by restoring serotonin-modulated synaptic plasticity in the anterior cingulate cortex. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2022;54(4):566–581. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.