ABSTRACT

Hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) play a pivotal role in blood cell production, maintaining the health and homeostasis of individuals. Dysregulation of HSPC function can lead to blood‐related diseases, including cancer. Despite its importance, our understanding of the genes and pathways underlying HSPC development and the associated pathological mechanisms remains limited. To elucidate these unknown mechanisms, we analyzed databases of patients with blood disorders and performed functional gene studies using zebrafish. We employed bioinformatics tools to explore three public databases focusing on patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and related model studies. This analysis identified significant alterations in several genes, especially SMC2 and other condensin‐related genes, in patients with MDS. To further investigate the role of Smc2 in hematopoiesis, we generated smc2 loss‐of‐function zebrafish mutants using CRISPR mutagenesis. Further analyses of the mutants revealed that smc2 depletion induced G2/M cell cycle arrest in HSPCs, leading to their maintenance and expansion failure. Notably, although the condensin II subunits (ncaph2, ncapg2, and ncapd3) were essential for HSPC maintenance, the condensin I subunits did not affect HSPC development. These findings emphasize the crucial role of condensin II in ensuring healthy hematopoiesis via promoting HSPC proliferation.

Keywords: condensin, hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells, myelodysplastic syndrome, smc2, zebrafish

1. Introduction

Hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) are multipotent progenitor cells with the capacity for both self‐renewal and differentiation (Seita and Weissman 2010). Located within the bone marrow, these cells continuously generate all types of blood cells, including the erythroid, myeloid, and lymphoid lineages (Copley and Eaves 2013; Sawai et al. 2016). Consequently, they play crucial roles in supporting immune responses and efficient oxygen transport throughout the body (Shevyrev et al. 2023). Furthermore, HSPCs dynamically maintain blood homeostasis by adjusting their proliferation or maturation according to the body's needs (Glauche et al. 2009). Proper HSPC development, maintenance, and function are thus essential for the overall homeostasis of the body and effective response to various challenges.

Defective HSPC development and function can lead to various blood diseases and disorders (Robertson et al. 2016; Risitano et al. 2007; Bao et al. 2019). Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) results from malfunctioning HSPCs, leading to inadequate or aberrant production of certain blood cell types (Zhan and Park 2021). Aplastic anemia, characterized by insufficient production of blood cells, often originates from dysfunctional HSPCs in the bone marrow (Medinger et al. 2018). Furthermore, leukemia, a cancer that affects both blood and bone marrow, can originate from mutations within HSPCs, causing uncontrolled production of atypical white blood cells (Passegué et al. 2003). These disorders highlight the vital role of HSPCs in maintaining blood health, emphasizing the need for comprehensive research into HSPC biology and related diseases.

Blood disorders primarily arise from hematopoietic homeostasis failure and the aberrant regulation of molecular mechanisms supervising hematopoiesis (Sachs 1996; Enciso et al. 2015). Therefore, to understand the roles of genes potentially associated with hematopoietic malignancies, it is crucial to functionally validate those genes related to regular hematopoiesis. Zebrafish are excellent vertebrate model systems for studying hematopoiesis and blood diseases owing to their unique experimental advantages and conserved hematopoietic system, similar to that of mammals (Han et al. 2017; Traver et al. 2003). For instance, our studies using zebrafish embryos revealed the association of FAM213A with both the prognosis of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and the modulation of oxidative stress and myelopoiesis (Oh, Ha, et al. 2020). Additionally, we determined the association between TPD52, a poor prognostic indicator of AML, and HSPC maintenance, specifically its influence on cell proliferation during zebrafish embryogenesis (Kang et al. 2020). The condensin complex subunit, CAP‐G2, is intricately linked to erythroid cell differentiation (Xu et al. 2006). Zebrafish research has provided diverse insight into the functions of genes associated with blood disorders.

Condensin is an essential protein complex involved in chromosomal condensation and segregation during mitosis and meiosis (Ono et al. 2003; Hagstrom et al. 2002). The structure of the condensin complex depends on the structural maintenance of chromosome (SMC) proteins and non‐SMC condensin complex subunits. The heterodimers of SMC2 and SMC4 form the primary axis of the condensin complex, where both subunits feature crucial ATP‐ and nucleotide‐binding motifs (Ono et al. 2003; Hagstrom et al. 2002; Palou et al. 2018). By complementing these SMC proteins, non‐SMC subunits complete the condensin complex. Based on their configuration of non‐SMC subunits, condensins are categorized as condensin I (composed of CAP‐H, CAP‐G, and CAP‐D2) and condensin II (composed of CAP‐H2, CAP‐G2, and CAP‐D3) (Hirano 2012). These complexes, which are evolutionarily conserved among vertebrates, are instrumental in chromosomal assembly and segregation (Ono et al. 2003; Hirano 2012; Hirano et al. 1997).

Each condensin subunit plays a distinct role during mitosis, influencing the chromosome structure according to its cellular distribution ratio (Skibbens 2019). Condensin I facilitates cohesin dissociation from chromosome arms and chromosome shortening via prometaphase and metaphase, whereas condensin II primarily contributes to chromosome condensation in early prophase (Hirota et al. 2004). Individual non‐SMC components affect the development and function of specific cells or organs. For example, the condensin I complex regulates the survival of proliferating cells in the neural retina of the zebrafish (Seipold et al. 2009). Condensin II subunits function as regulators of mammalian T‐cell differentiation and cell fate determination in Drosophila (Gosling et al. 2007; Klebanow et al. 2016).

Despite these insights, our understanding of the specific functions of SMC2 and the associated non‐SMC proteins in blood disorders and hematopoiesis remains incomplete. This study aims to identify candidate genes and pathways implicated in blood diseases and their associated hematopoietic processes. We analyzed genomic data from patients diagnosed with MDS and performed loss‐of‐function experiments using zebrafish to determine how the condensin complex contributes to HSPC development. Our findings will enhance our understanding of the condensin complex's role in hematopoiesis and its relevance to blood disorders.

2. Methods

2.1. Analysis of RNA‐seq Datasets

Three MDS‐associated transcriptome datasets, bulk RNA‐seq datasets under the accession GSE173108 (Mian et al. 2023), GSE183325 (Berastegui et al. 2022), and GSE131581 (Ochi et al. 2020) were downloaded from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and reanalyzed. At first, a typical differential analysis on four different bulk RNA‐seq datasets was processed through DESeq. 2 (Love et al. 2014) (log2 fold change > 0 for upregulation, log2 fold change < 0 for downregulation, and p value < 0.05) and visualized using EnhancedVolcano. From the differentially expressed genes (DEGs), protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks were generated through STRING (Szklarczyk et al. 2023), which is a protein interaction database containing known direct/indirect associations, where each interaction score was higher than 0.9. Those PPI networks narrowed down into three protein clusters from the DEGs, and one of the protein complexes from those clusters known to be irrelevant to MDS to the best of our knowledge was selected. Finally, one of the protein families (condensin complex), smc2, was considered as a potential MDS‐associated gene for further investigation.

2.2. Zebrafish Maintenance and Chemical Treatment

Wild‐type (WT) AB zebrafish were maintained in an automatic circulation system (Genomic‐Design) at 28.5°C. All experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology (UNIST) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) (approval number: UNISTIACUC‐20‐09). Eggs and embryos were maintained with E3 solution in incubators at 28.5°C. Nocodazole (500 μg/mL [Sigma Aldrich, USA]) dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was prepared to induce G2/M cell cycle arrest. Twelve zebrafish embryos were incubated with nocodazole (500 ng/mL) from 24 h post fertilization (hpf) for 48 h, whereas the control group was treated with 0.1% DMSO.

3. Results

3.1. Alteration of Condensin Components in Samples From Patients With MDS and an Experimental MDS Model

Based on the hypothesis that there are genetic alterations related to general hematopoiesis in the development of blood diseases (Bao et al. 2019), we examined multiple databases of patients with such conditions. As MDS involves challenges in both normal blood cell development and HSPC genesis and function (Zhan and Park 2021), we conducted an analysis on MDS to understand the mechanisms related to hematopoiesis, including HSPC development.

To investigate the functional mechanisms of genes associated with MDS, we focused on identifying candidate genes using RNA‐seq datasets from patients with MDS. Three bulk RNA‐seq datasets were collected: (i) human CD34+ HSPCs from patients with MDS (GSE173108) (Mian et al. 2023), (ii) four human hematopoietic stem cells characterized as CD34+ CD38− CD90+ CD45RA− (GSE183325) (Berastegui et al. 2022), and (iii) cells with cohesin mutation linked to MDS (GSE131581) (Ochi et al. 2020). Equipped with these datasets, we conducted a comprehensive analysis to identify significantly DEGs and determine the overlapping gene lists across all three datasets. Furthermore, we performed protein‐interaction profiling for these candidates to understand their potential interplays.

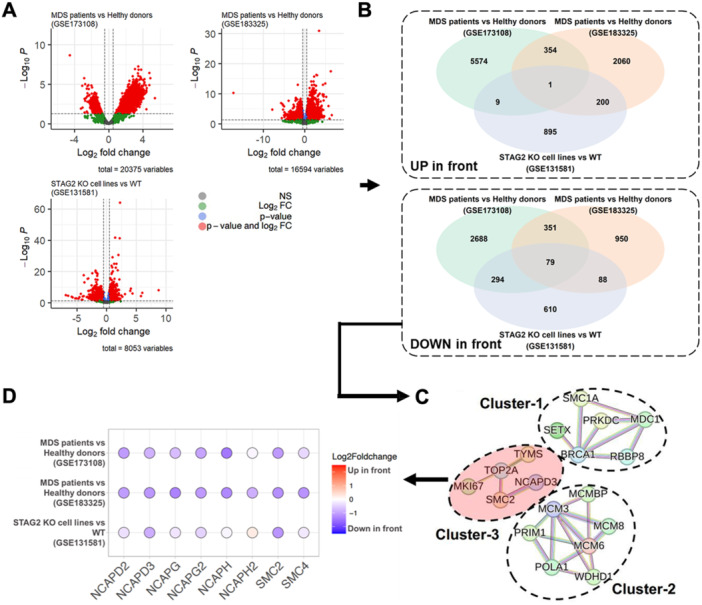

We first performed differential analyses of gene expression levels in three groups: (i) patients with MDS and healthy individuals (GSE173108), (ii) patients with MDS and healthy young adults (GSE183325), and (iii) STAG2 knock‐out HL‐60 cell lines presenting MDS‐like phenotypes and WT controls (GSE131581). A significant number of DEGs were revealed in each comparison: 9329 in the first, 4107 in the second, and 2184 in the third (Figure 1A). Interestingly, one gene was upregulated, whereas the expression of 80 genes was consistently downregulated in all three groups (Figure 1B). One gene that was found to be upregulated is SLC29A2, which, according to the results of previous studies, has been shown to have little impact on MDS (Follo et al. 2019; Kutyna et al. 2023). Thus, we focused on transcriptional profile changes in downregulation.

Figure 1.

Selection procedure of target proteins using RNA‐seq datasets of MDS‐associated samples via three different comparisons. (A) Volcano plots of significantly differentially expressed MDS‐associated genes for the three comparisons: (i) MDS patients versus healthy donors (GSE173108), (ii) MDS patients versus healthy young adults (GSE183325), and (iii) STAG2 knock‐out (KO) HL‐60 cells versus WT HL‐60 cells (GSE131581). (B) Venn diagrams comparing the three DEGs for up/downregulations. (C) Protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks connected using significant DEGs. (D) Transcriptional profiles of the condensin family across the three comparisons.

Next, we generated PPI networks from the overlapping DEG list of downregulated genes. Subsequently, we narrowed them down to three protein families that were significantly related to each other (Figure 1C). The first group of Cluster 1 includes genes such as SMC1A, MDC1, SETX, BRCA1, PRKDC, and RBBP, which are primarily involved in DNA repair processes (BRCA1‐C complex [BRCA1 and RBBP] and the DNA repair complex [BRCA1 and PRKDC]). Cluster 2 contains genes such as PRIM1, MCM3, MCMBP, POLA1, MCM6, MCM8, and WDHD1, which are involved in DNA replication (regulation of DNA‐directed DNA polymerase activity containing the MCM complex [MCM3, MCM6, and MCM8] and alpha DNA polymerase complex [MCM3, POLA1, and PRIM1]). Finally, the third group, Cluster 3, involves genes such as TYMS, MKI67, TOP2A, SMC2, and NCAPD3, which play essential roles in cell division processes like chromatid segregation and mitotic spindle checkpoint signaling.

Genes or pathways involved in DNA replication and repair are associated with MDS (Zhou et al. 2015; Borges et al. 2023; Ribeiro et al. 2016; Flach et al. 2021). However, the role of the condensin complex in MDS has not yet been thoroughly explored. Consequently, our study focused on Cluster 3 of the condensin complex, which includes genes such as SMC2 and NCAPD3. We further examined the expression patterns of these genes and expanded our analysis to other genes in the complex‐ SMC4, NCAPG, NCAPG2, NCAPD2, NCAPH, and NCAPH2−, as shown in Figure 1D. Notably, all condensin complex genes were significantly downregulated. SMC2, in particular, exhibited the most consistent suppression across all three datasets, indicating a potentially strong link with MDS. Collectively, our findings suggested that the condensin complex may be involved in MDSs, with SMC2 possibly playing a pivotal role in this association.

3.2. Generation of Zebrafish smc2 Null Mutants

Our bioinformatics study, using datasets of patients with MDS and cellular models, revealed an association between the condensin complex, including SMC2, and blood diseases. To elucidate its role in hematopoiesis, we used a zebrafish model, capitalizing on the considerable conservation of SMC2 between zebrafish and humans (Supporting Information S1: Figure 1). This evolutionary conservation established the relevance of zebrafish in modeling human hematopoiesis in our study.

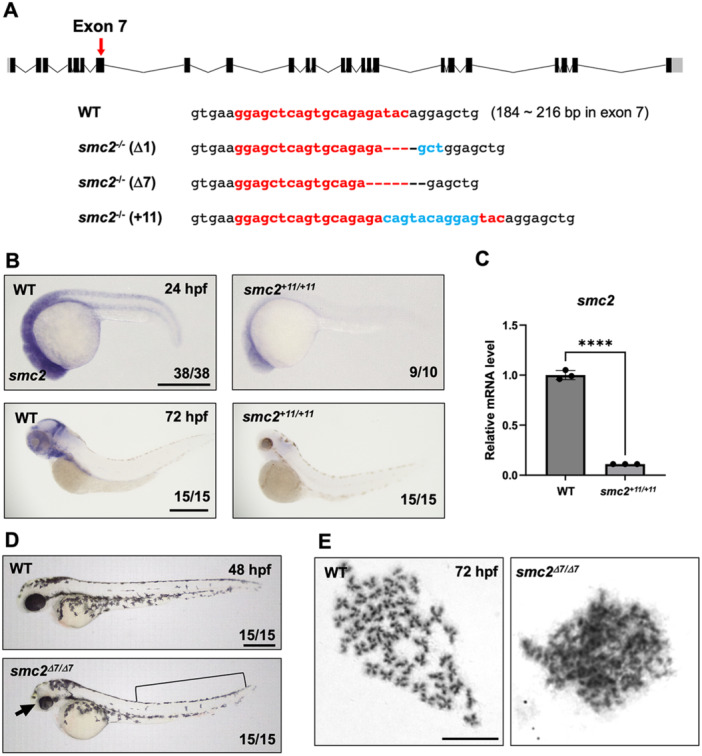

Focusing on the function of smc2 in hematopoiesis, we created smc2 zebrafish mutants via CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis using a single guide RNA (sgRNA) targeting exon 7 in smc2, resulting in mutants with three distinct allelic variants (Figure 2A). All three mutants possess small insertions/deletions (in/del) alleles that generate frameshift mutations, possibly leading to nonsense mRNA decay becoming functionally null (Shalem et al. 2014). To examine the stability of smc2 mRNA in the mutants, we performed whole‐mount in situ hybridization (WISH) using smc2 probes and quantitative PCR (qPCR) analyses. Our observations revealed that smc2 mRNA began to decrease from 24 hpf and was mostly abolished at 72 hpf, confirming that our mutants lacked normal Smc2 function (Figure 2B,C).

Figure 2.

Generation of smc2 mutants via CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis. (A) A diagram of smc2 targeted by a sgRNA at exon 7 (a red arrow) and the sequences of three different smc2 mutant alleles generated using CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis. Numbers in parentheses with WT sequences indicate the position in the open reading frame of the targeted exon 7 of smc2. The sgRNA sequence is shown in red bold letters. Deletions are illustrated as dashed lines and insertions as blue letters. (B) Whole‐mount in situ hybridization (WISH) using a smc2 probe of smc2 mutant embryos and its WT sibling controls at 24 and 72 h post fertilization (hpf). The numbers shown at the bottom of the images represent the count of representative outcomes observed relative to the total number of embryos obtained. Data from two independent experiments. Scale bar = 400 μm. (C) Quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis assessing the relative expression levels of the smc2 gene in WT and smc2 null mutant zebrafish embryos at 72 hpf. Expression levels of smc2 were normalized to β‐actin, with results presented as relative fold changes. Data were quantified and expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) from three independent biological replicate experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using a t‐test to calculate p‐values. (****p < 0.0001). (D) Lateral view of smc2 mutant embryos and WT controls at 48 hpf. smc2 mutants demonstrated morphological defects in the head (black arrow) and yolk extension (black square bracket). Data from two independent experiments. Scale bar = 400 μm. (E) Chromosome‐spreading assay of WT and smc2 mutant embryos at 72 hpf from three independent experiments performed. The scale bar indicates the designated length in the images. Scale bar = 10 μm.

To characterize the effects of smc2 depletion during embryogenesis, we monitored the morphology of smc2 mutants. Homozygous mutant embryos displayed distinct morphological abnormalities from 48 hpf, including reduced head size, smaller eyes, and aberrant yolk extension, leading to lethality by 5‐day post fertilization (dpf) (Figure 2D). To examine the effects of Smc2 on chromosomal condensation at the organismal level, we performed chromosome‐spreading assays using zebrafish smc2 mutants. WT zebrafish embryos exhibited normal condensation during mitosis, whereas smc2 mutants failed to form normally condensed chromosomes (Figure 2E). Collectively, our results demonstrated that smc2 null mutants created using CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing successfully function as loss‐of‐function reagents.

3.3. Smc2 Is Necessary for HSPC Maintenance

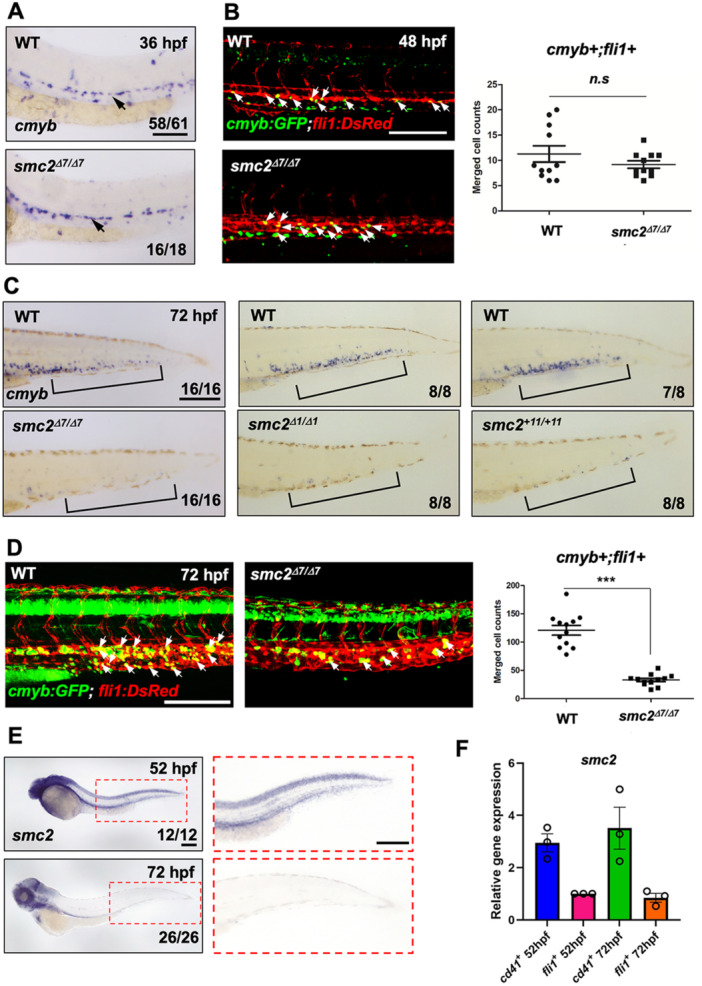

Zebrafish hematopoiesis proceeds sequentially with primitive and definitive waves of blood cells, similar to that of the mammalian system (Gore et al. 2018; Davidson and Zon 2004). Primitive hematopoiesis generates erythroid and myeloid populations from unipotent mesodermal precursors, whereas definitive multipotent HSPCs arise from the hemogenic endothelium (Espanola et al. 2020; Zhen et al. 2013). To examine whether any hematopoietic events are affected by the loss of Smc2, we performed WISH on smc2 mutants using each blood marker. WISH using the erythroid‐specific marker, gata1, and the myeloid marker, mpx, showed that primitive hematopoiesis commenced normally in the absence of smc2 (Supporting Information S1: Figure 2A). Next, we examined definitive HSPC formation in the hemogenic endothelium of the dorsal aorta using a probe targeting cmyb at 36 hpf. Similar to WT sibling control embryos, smc2 mutants showed normal cmyb expression in the dorsal aorta (Figure 3A). This was further corroborated via confocal microscopy of cmyb:GFP;fli1:DsRed transgenic reporter lines, which showed no differences in the initial formation of HSPCs in the dorsal aorta at 48 hpf between smc2 mutants and controls (Figure 3B). Additionally, blood circulation in the aorta, essential for the specification and emergence of HSPCs in the dorsal aorta (North et al. 2009), was normal in the mutants as shown in Supporting Information S2: Movie 1.

Figure 3.

SMC2 is required for hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell (HSPC) maintenance. (A) WISH of smc2 mutant embryos and WT controls using HSPC marker cmyb in the dorsal aorta (black arrows). The numbers shown at the bottom of the images represent the count of representative outcomes observed relative to the total number of embryos obtained. Results from three independent experiments. (B) Confocal imaging of smc2 mutant embryos and sibling controls with a cmyb:GFP;fli1:DsRed transgenic background at 48 hpf (white arrows indicate HSPCs). Right panel: quantification of cmyb+;fli1+ double positive cells in the dorsal aorta at 48 hpf (WT, n = 11; mutants, n = 10). Data were quantified and expressed as the mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using a t‐test to calculate p‐values (n.s., no significance at p > 0.05). Data from a single experiment. (C) WISH using a HSPC‐specific cmyb antisense probe of three distinct smc2 mutant embryos and their WT controls in caudal hematopoietic tissue (CHT) at 72 hpf. Black square brackets indicate CHT. Data obtained from a single experiment. (D) Confocal imaging of WT embryos and smc2 mutants at 72 hpf using cmyb:GFP;fli1:DsRed transgenic zebrafish. White arrows indicate HSPCs. Right panel: quantification of cmyb+;fli1+ double positive HSPCs in the CHT at 72 hpf (WT, n = 11; mutants, n = 10; ***p < 0.001). Results from two independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using a t‐test to calculate p‐values. (E) Transcriptional expression of smc2 during embryogenesis with smc2 WISH of WT embryos at 52 and 72 hpf. The red‐dotted box is a magnified image of the CHT at 52 and 72 hpf. Combined data from two independent experiments. (F) qPCR analysis of smc2 expression in CD41‐positive HSPCs and fli1‐positive endothelial cells at 52 and 72 hpf. The expression levels of smc2 were normalized to the β‐actin, with results presented as relative fold changes. Data were quantified and expressed as the mean ± SEM of three independent biological replicates. Scale bar = 200 μm.

After emergence from hemogenic endothelial cells in the dorsal aorta, HSPCs migrate to the caudal hematopoietic tissue (CHT) through the circulatory blood to expand and mature into functional blood stem cells (Mahony and Bertrand 2019; Tamplin et al. 2015). WISH analysis using a cmyb antisense probe and confocal imaging of cmyb:GFP;fli1:DsRed zebrafish embryos at 72 hpf showed that the HSPC population in the CHT was robustly reduced in smc2 mutants compared to WT controls (Figure 3C,D). Additionally, the absence of lymphoid cells in the thymus, as indicated by a lymphoid‐specific rag1 probe at 4 dpf, suggested a failure in lymphoid generation from definitive HSPCs (Supporting Information S1: Figure 2B). Collectively, these findings implied that although Smc2 is not necessary for HSPC emergence in the dorsal aorta, it plays a crucial role in maintaining these progenitor cells within the CHT.

To further characterize the role of Smc2 in HSPC maintenance, we traced the spatial expression pattern of smc2 during embryogenesis using WISH. smc2 was broadly expressed in the anterior part of the embryo, including the head, and was prominently observed in the CHT at 52 hpf, although its expression declined by 72 hpf (Figure 3E), indicating its potential importance in HSPC maintenance from as early as 52 hpf. To closely investigate smc2 expression within the CHT, we utilized CD41:GFP and fli1:GFP transgenic reporter lines to examine its expression levels in FACS‐sorted CD41‐positive HSPCs and fli1‐positive vascular endothelial cells (Supporting Information S1: Figure 3). Interestingly, at both 52 and 72 hpf, smc2 expression was markedly higher in CD41‐positive HSPCs than in fli1‐positive endothelial cells (Figure 3F). The sustained high expression of smc2 in HSPCs appears critical for their maintenance during this period, suggesting a possible cell‐autonomous effect of Smc2 on HSPC maintenance in zebrafish embryos.

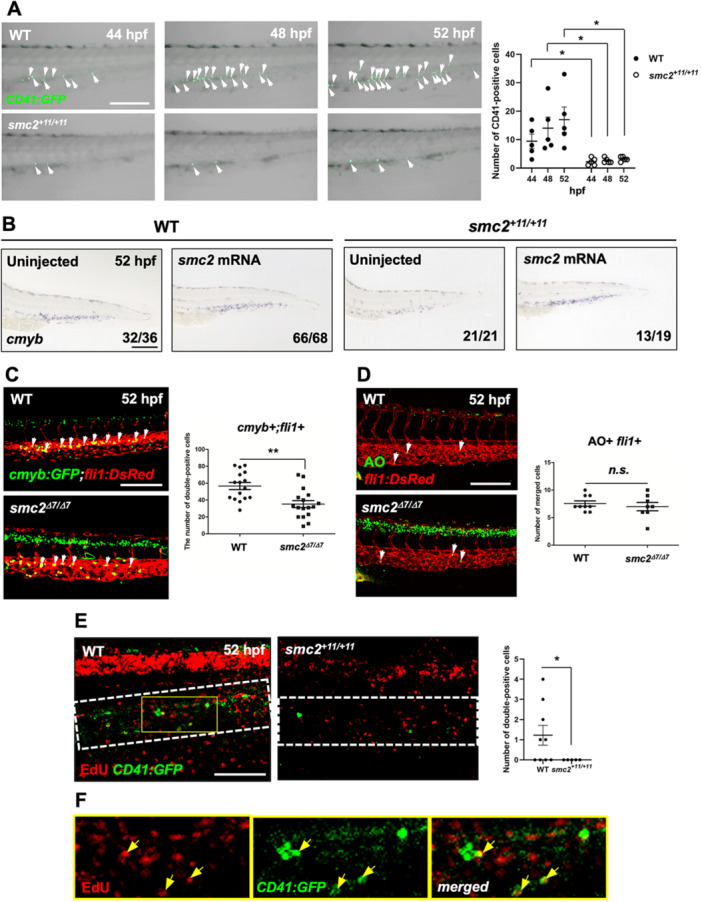

3.4. Depletion of Smc2 Inhibited HSPC Proliferation in the CHT

To evaluate the phenotypes of smc2 mutants with HSPC maintenance failure, we tracked HSPCs within the CHT during the homing and expansion stages which are critical for HSPC development (Mahony and Bertrand 2019; Xue et al. 2017). Using CD41:GFP transgenic animals in an smc2 mutant background, we monitored CD41‐positive HSPCs starting at 44 hpf, the onset of HSPC homing to the CHT. From 44 to 52 hpf, the number of HSPCs in the CHT showed a significantly larger difference between the control and mutant groups (Figure 4A). Although HSC emergence normally occurs during this period (Figure 3B), the noticeable difference starting from 44 hpf in mutants suggests possible impaired HSPC lodgment within the CHT. Furthermore, although HSPC numbers continuously increased in the WT group from 44 to 52 hpf, the mutant group showed little to no increase, indicating potential defects in both lodgment and subsequent expansion. Restoration of normal HSPC formation at 52 hpf in mutants through the injection of normal smc2 mRNA confirms the role of smc2 in these processes (Figure 4B). Additional experiments using morpholino (MO) to knock down smc2 showed that although initial HSPC emergence was unaffected, their maintenance or expansion from 52 to 72 hpf was disrupted, mirroring findings in smc2 mutants (Supporting Information S1: Figure 4). Confocal microscopy using cmyb:GFP;fli1:DsRed further confirmed a significant reduction in HSPCs at 52 hpf in smc2 mutants (Figure 4C). These results highlight the crucial role of Smc2 in the maintenance and expansion of HSPCs in the CHT of zebrafish embryos from 52 hpf.

Figure 4.

Smc2 is required for HSPC proliferation in the CHT. (A) Confocal imaging of smc2 mutant embryos and sibling controls with a CD41:GFP transgenic background at 44, 48, and 52 hpf. Right panel: quantification of CD41‐positive HSPCs in the CHT (WT at 44 hpf, n = 5; mutants at 44 hpf, n = 5; WT at 48 hpf, n = 5; mutants at 48 hpf, n = 5; WT at 52 hpf, n = 5; mutants at 52 hpf, n = 5; *p < 0.05). White arrows indicate CD41‐positive HSPCs. Data from a single experiment. (B) WISH of smc2 mutant embryos and WT controls at 52 hpf following injection with smc2 mRNA. Black square brackets indicate the cmyb signal in the CHT. The numbers shown at the bottom of the images represent the count of representative outcomes observed relative to the total number of embryos obtained. Data from two independent experiments. (C) Confocal microscopy images of smc2 mutant embryos and their sibling controls in the cmyb:GFP;fli1:DsRed background. White arrows indicate HSPCs. Right panel: quantification of cmyb+;fli1+ cells in the CHT at 52 hpf (WT, n = 16; mutants, n = 17; **p < 0.01). Data from a single experiment. (D) Confocal imaging of smc2 mutant embryos and WT controls at 52 hpf with acridine orange (AO) staining using fli1:DsRed transgenic zebrafish embryos. White arrows indicate AO‐positive apoptotic cells. Right panel: quantification of AO+;fli1+ cells in the CHT (WT, n = 8; mutants, n = 8; n.s., no significance at p > 0.05). Data from a single experiment. (E) Confocal microscopy imaging of EdU‐stained (incorporating 24 h) smc2 mutant embryos and WT sibling controls in the background of CD41:GFP at 52 hpf. White‐dotted box indicates CHT. Right panel: quantification of EdU‐ and CD41‐double positive cells in the CHT (WT, n = 9; mutants, n = 5; *p < 0.05). The results represent data from two independent experiments. (F) Higher magnification images of the yellow box in EdU‐stained WT;CD41:GFP transgenic zebrafish embryos from (E). Yellow arrows indicate EdU‐ and CD41‐double positive cells in the CHT. All quantification data were quantified and expressed as the mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using a t‐test to calculate p‐values. Scale bar = 200 μm.

To investigate the cellular mechanisms underlying the observed HSPC maintenance defects in smc2 mutants, we evaluated cellular apoptosis and proliferation rates. Acridine orange (AO) staining of endothelium‐specific fli1:DsRed transgenic embryos indicated no significant changes in apoptosis within the CHT of smc2 mutants at 52 hpf, whereas a notable increase in apoptosis was observed within the neural tissues of the mutants (Figure 4D). Similarly, TUNEL staining confirmed no alteration in cell death under the smc2 MO knockdown conditions (Supporting Information S1: Figure 5A). Moreover, vasculature formation in the CHT, including the appearance of vascular plexus—a critical HSPC niche for retention (Wattrus and Zon 2018)—appeared normal in the absence of Smc2 (Figure 4C,D and Supporting Information S1: Figure 5B,C). In contrast, EdU staining for cell proliferation revealed a complete absence of detectable cell division in smc2 mutants and morphants across all tissues, including the CHT, during a 10‐min EdU exposure at 52 hpf (Supporting Information S1: Figure 5D,E). This suggests that Smc2 plays a critical, systemic role in cell proliferation. Further EdU staining after 24‐h exposure detected some proliferating cells in neural cells and the CHT of mutants (Figure 4E,F). However, these were significantly fewer compared to the WT controls, and particularly, the number of CD41‐ and EdU‐double positive HSPCs in the CHT was completely absent in smc2 mutants relative to the WT group. Collectively, these results demonstrate that Smc2 is essential for the proliferation of HSPCs within the CHT, which is critical for the proper maintenance and expansion of the blood progenitor cell population.

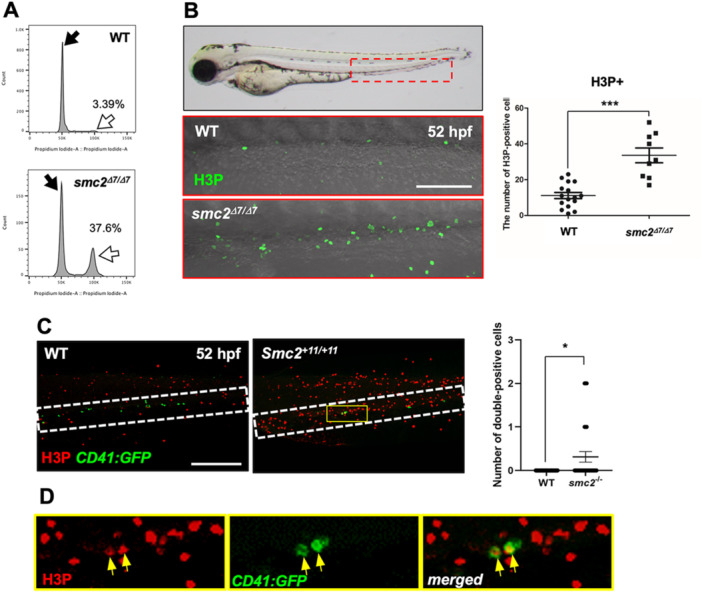

3.5. G2/M Arrest Disrupts HSPC Maintenance in the CHT of smc2 Mutants

Previous studies have established the critical role of condensin subunits, including SMC proteins, in chromosome segregation and cell cycle progression (Jensen and Shapiro 1999; Graumann 2001). Specifically, non‐SMC2 subunits such as Ncaph1 are essential for cell cycle progression, with their knockdown suppressing the proliferation of pancreatic cancer cell lines (Kim et al. 2019). To investigate the potential impact of the loss of smc2 on cell cycle events and its consequent effect on HSPC proliferation, we performed DNA content analysis on smc2 mutant and control embryos at 52 hpf using flow cytometry after staining the DNA with propidium iodide. The results revealed an increased occurrence of G2/M phase cell cycle arrest in smc2 mutants compared to WT controls (Figure 5A). To ascertain if this cell cycle arrest was induced in the HSPCs, we conducted immunohistochemistry staining with H3P, a marker for G2/M cell cycle arrest (Sun et al. 2014; Jin et al. 2017). The number of H3P‐positive cells within the CHT was significantly higher in smc2 mutants than that in WT controls (Figure 5B). Additionally, using CD41:GFP transgenic zebrafish embryos, we found that H3P+ and CD41+ double‐positive cells were present in smc2 mutants, whereas no double‐positive cells were observed in WT controls (Figure 5C,D). This result indicated that cell cycle arrest occurred at the G2/M phase within HSPCs lacking smc2. Likewise, nocodazole treatment, which can induce cell cycle arrest at the G2/M phase as a microtubule polymerization inhibitor (Blajeski et al. 2002), blocked HSPC expansion and maintenance in the CHT, similar to that in smc2 mutants (Supporting Information S1: Figure 6). Taken together, these findings suggested that G2/M cell cycle arrest in HSPCs, induced by the loss of Smc2, leads to failure in HSPC expansion and maintenance.

Figure 5.

G2/M cell cycle arrest disrupts HSPC maintenance in the CHT in smc2 mutants. (A) Fluorescence‐activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis of DNA content in WT and smc2 mutant embryos at 52 hpf following propidium iodide (PI) staining. Black and white arrows indicate the G1 and G2/M phase peak, respectively. The indicated percentage represents the DNA content in the G2/M phase. Data from two independent biological replicate experiments. (B) Confocal microscopy images of smc2 mutants (n = 9) and WT controls (n = 16) immunohistochemically stained with the H3P antibody in the CHT (red‐dotted box) at 52 hpf. Red‐dotted box indicates CHT. Right panel: quantification of H3P+ cells in the CHT (***p < 0.001). Data combined from two independent experiments. (C) Confocal imaging of H3P‐stained smc2 mutant embryos (n = 29) and WT sibling controls (n = 50) in the CHT at 52 hpf using CD41:GFP transgenic zebrafish. White‐dotted box indicates CHT. Right panel: quantification of H3P‐ and CD41‐double positive cells in the CHT (*p < 0.05). The results represent data from two independent experiments. (D) Higher magnification images of the white‐dotted box in H3P‐stained smc2 −/ −;CD41:GFP transgenic zebrafish embryos from (C). Yellow arrows indicate H3P‐ and CD41‐ double positive cells in the CHT of smc2 mutants. All quantification data were quantified and expressed as the mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using a t‐test to calculate p‐values. Scale bar = 200 μm.

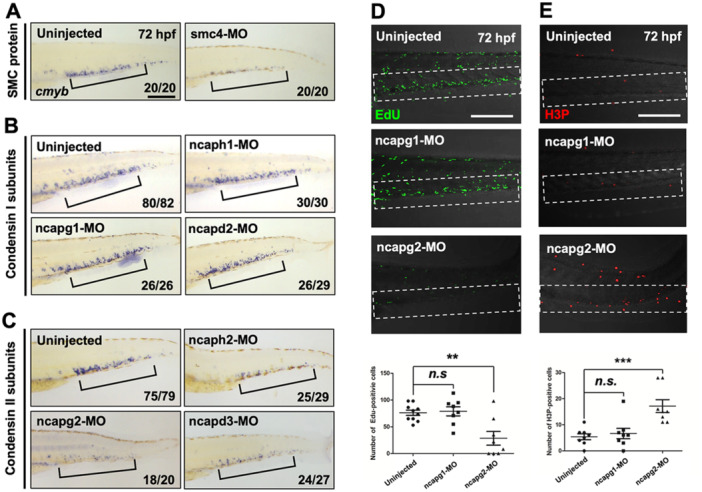

3.6. Condensin II Subunits Are Crucial for HSPC Maintenance

To further understand the role of the condensin complex in hematopoiesis, we examined the function of other condensin subunits in hematopoiesis via knockdown approaches using splice‐blocking MOs (Supporting Information S1: Figure 7). Notably, smc4 knockdown led to the loss of HSPCs in the CHT, like the phenotype of smc2 null mutants, indicating a consistent requirement of both Smc2 and Smc4 in HSPC development (Figure 6A). Furthermore, our functional assessment revealed a distinct role between condensin I and II subunits. Knockdown of condensin II components (ncaph2, ncapg2, and ncapd3) significantly reduced HSPCs in the CHT like smc2 mutants, whereas knockdown of condensin I subunits (ncaph1, ncapg1, and ncapd2) showed no visible alteration of cmyb expression in the CHT (Figure 6B,C). To further validate the specific requirement of condensin II for HSPC proliferation, we performed EdU and H3P staining using morphants against ncapg1 and ncapg2. The ncapg2 knockdown markedly decreased the number of Edu+ cells and increased the number of H3P+ cells in the CHT, compared to controls (Figure 6D,E). In contrast, ncapg1 knockdown did not alter the number of EdU+ or H3P+ cells. Collectively, these findings suggested that condensin II plays an essential role in the regulation of HSPC proliferation and maintenance within the CHT.

Figure 6.

Condensin II subunits are required for HSPC maintenance. (A–C) WISH using the cmyb antisense probe at 72 hpf in WT embryos injected with morpholinos (MOs) targeting smc4 (A), condensin I subunits (ncaph1, ncapg1, and ncapd2) (B), condensin II subunits (ncaph2, ncapg2, and ncapd3) (C), and their corresponding uninjected controls. Black square brackets indicate cmyb‐positive HSPCs in the CHT. The numbers shown at the bottom of the images represent the count of representative outcomes observed relative to the total number of embryos obtained. WISH data from a single experiment. (D) Confocal microscopy images of EdU‐stained morphants of ncapg1 and ncapg2 and their uninjected controls at 72 hpf. White‐dotted box indicates CHT. Bottom panel: quantification of EdU+ cells in the CHT (uninjected, n = 10; ncapg1‐MO, n = 10; ncapg2‐MO, n = 10; n.s., no significance at p > 0.05; **p < 0.01). Data from a single experiment. (E) Confocal microscopy images of H3P‐stained morphants targeting ncapg1 and ncapg2 and their uninjected controls at 72 hpf. Bottom panel: quantification of H3P+ cells in the CHT (uninjected, n = 10; ncapg1‐MO, n = 10; ncapg2‐MO, n = 10; n.s., no significance at p > 0.05; ***p < 0.001). All quantification data were quantified and expressed as the mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using a t‐test to calculate p‐values. Data from a single experiment. Scale bar = 200 μm.

4. Discussion

MDS includes a group of diverse bone marrow disorders characterized by insufficient production of one or more blood cell types, often leading to anemia, infection, or bleeding (Dotson and Lebowicz 2023). Central to these disorders is the dysfunction of HSPCs, which play a critical role in the genesis of all the blood cell types (Zhan and Park 2021; Veiga et al. 2021; Li 2013). Various mutations or abnormalities can affect both HSPCs and the bone marrow microenvironment in MDS (Ganan‐Gomez et al. 2022; Shastri et al. 2017). Our analysis using patient databases and cellular models revealed a significant correlation between the expression of condensin complex subunits, particularly SMC2, and MDS occurrence.

Research utilizing animal models, particularly mice and zebrafish, has been pivotal in elucidating MDS characteristics. Diagnosis in these models typically relies on the morphology of blood cells, but the embryonic stage presents challenges, necessitating the use of specific blood cell markers. For example, mutations of TET2 and APC on chromosome 5q, known to be associated with MDS in mice, lead to enhanced self‐renewal capacity of HSPCs and impair their differentiation. This resulted in MDS‐related hematologic features including abnormal monocytosis or leukocytosis in mutants (Quivoron et al. 2011; Lane et al. 2010). In zebrafish, knockdown of TET2 resulted in defective erythroid development, an anemic phenotype, and a decrease in HSPC markers at 36 hpf (Ge et al. 2014). Additionally, the SF3B1 mutation, commonly observed in MDS patients, disrupt erythroid differentiation and HSPC development in zebrafish (De La Garza et al. 2016). Thus, various models of MDS demonstrate the disease's phenomena through defects in the differentiation of leukocytes, including erythroid, and the development of HSPCs.

Our investigation into smc2's role revealed that although hemogenic endothelium specification and initial HSPC emergence are normal in smc2 mutants, these mutants exhibit significant deficits in HSC expansion and maintenance. Specifically, a marked reduction in CD41‐positive HSPCs from 44 hpf indicates potential abnormalities in HSPC lodgment in the CHT. Further analysis of HSPC counts between 44, 48, and 52 hpf showed diminished expansion in the mutants, supported by EdU staining, which highlighted proliferation defects. Moreover, an increase in H3P‐positive cells points to potential cell cycle arrest at the G2/M phase in smc2 mutants, suggesting a multifaceted impact on initial homing, cell proliferation, and cell cycle regulation of HSPCs. To fully elucidate these processes, continued investigation is necessary, including further tissue‐specific functional studies to verify the potential cell‐autonomous effects of Smc2 on HSPCs.

These results align with our previous research using zebrafish models, which demonstrated a strong link between various blood disease‐related genes and hematopoiesis, specifically supervising HSPC development (Oh, Ha, et al. 2020; Oh, Kang, et al. 2020; Kang et al. 2020). In particular, the effects of condensins, including SMC2, on HSPC development observed in MDS patients and cellular models suggest that SMC2 may be functionally related to the onset of MDS.

Furthermore, our studies distinguished between the roles of condensin I and II in HSPC development. Notably, the suppression of condensin II subunits led to HSPC maintenance failure, whereas condensin I knockdown had no evident effects on HSPC development. This indicated a distinct and crucial role of the condensin II complex in zebrafish hematopoiesis.

Condensins and their subunits play crucial roles in various developmental processes and cancer pathogenesis (Gosling et al. 2007; Klebanow et al. 2016). For example, the overexpression of SMC2 is associated with tumorigenesis, and the blockade of SMC2 with antibodies has been proposed as a novel cancer treatment (Montero et al. 2020). Furthermore, the ectopic expression of SMC2 was observed in colon cancer, and its suppression impaired tumor growth in a xenograft mouse model (Dávalos et al. 2012). SMC4 expression is markedly increased in human gliomas, and its activity is associated with the aggressiveness of the TGF‐β signaling pathway (Jiang et al. 2017). Moreover, the fusion protein NUP214‐ABL1, associated with SMC4, has been identified in T‐cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia as a proliferation and survival enhancer for T lymphoblasts (De Keersmaecker et al. 2014).

In addition to the major subunits, non‐SMC condensin components contribute to tumorigenesis (Dávalos et al. 2012; Jiang et al. 2017). Condensin I subunits play vital roles in organogenesis and oncogenesis. For instance, NCAPG has been identified as a prognostic marker of hepatocellular carcinoma (Liu et al. 2017), and NCAPD2 was reported as a factor in the prognosis of triple‐negative breast cancer (Zhang et al. 2020). Additionally, NCAPHs show high expression in pancreatic cancer (Kim et al. 2019), highlighting the integral role of condensin I in solid tumor growth.

In contrast, condensin II subunits play a more prominent role in hematopoiesis and blood disorders. CAP‐G2 participates in erythropoiesis by interacting with the SCL protein, and a mutation in NCAPH2 leads to defects in T‐cell development in mouse cell strains (Xu et al. 2006; Gosling et al. 2007). Mutations in the condensin II subunit, Caph2, have been linked to genome instability and T‐cell lymphoma due to uncontrolled accumulation of mature T cells in the lymph nodes (Woodward et al. 2016). Likewise, our study extends this understanding by demonstrating the essential role of condensin II subunits in normal hematopoiesis and their potential correlation with MDS. This emphasizes the need for comprehensive research on the role of the condensin II complex in blood health and disease.

In summary, our findings reinforce the critical role of condensin complexes, particularly condensin II, in hematopoiesis and blood disorders. These results highlight the need for further research into the specific mechanisms through which condensin II affects HSPC function and contributes to MDS development. However, it is important to recognize that our results and interpretation are based on specific experimental conditions and may not fully represent the complexity of in vivo conditions. Therefore, more detailed research on the tissue‐specific effects of condensin complexes and distinct molecular mechanisms of condensin II subunits in hematopoiesis at the cellular level is needed. Future studies exploring the interplay between condensin complexes and HSPC functionality may provide new strategies for diagnosing and treating hematological diseases.

Author Contributions

Y.L., C.‐K.O., and K.M. designed the experiments. C.‐K.O., M.S.K., U.S., J.W.K., Y.H.K., H.S.K., J.S.R., S.A., E.Y.C., S.Y., U.N., and T.C. performed the experiments. C.‐K.O., M.S.K., U.S., K.M., and Y.L. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Ethics Statement

Zebrafish were raised in accordance with Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology and Use Committees (IACUC: UNISTIACUC‐20‐09).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Acknowledgments

We thank Eun‐Sun Kim for the technical support as well as Dr. Raman Sood and Dr. Shawn Burgess from the NIH for their initial efforts to establish the smc2 zebrafish mutant line. This work was supported by a grant from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF‐2022R1A2C100677813 and NRF‐2022R1A2C300781813 to Y.L.), the Institute for Basic Science (grant number IBS‐R022‐D1 to K.M.), Learning & Academic Research Institution for Master's·PhD Students, Postdocs (LAMP) Program of the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Ministry of Education (No. RS‐2023‐00301938 to C.‐K.O.), and the Bio&Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. RS‐2023‐00223764 to C.‐K.O.).

Chang‐Kyu Oh, Man S. Kim, and Unbeom Shin contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Kyungjae Myung, Email: kmyung@ibs.re.kr.

Yoonsung Lee, Email: ylee3699@khu.ac.kr.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

- Bao, E. L. , Cheng A. N., and Sankaran V. G.. 2019. “The Genetics of Human Hematopoiesis and Its Disruption in Disease.” EMBO Molecular Medicine 11, no. 8: e10316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berastegui, N. , Ainciburu M., Romero J. P., et al. 2022. “The Transcription Factor DDIT3 Is a Potential Driver of Dyserythropoiesis in Myelodysplastic Syndromes.” Nature Communications 13, no. 1: 7619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blajeski, A. L. , Phan V. A., Kottke T. J., and Kaufmann S. H.. 2002. “G(1) and G(2) Cell‐Cycle Arrest Following Microtubule Depolymerization in Human Breast Cancer Cells.” Journal of Clinical Investigation 110, no. 1: 91–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges, D. P. , Dos Santos R. M. A. R., Velloso E. R. P., et al. 2023. “Functional Polymorphisms of DNA Repair Genes in Latin America Reinforces the Heterogeneity of Myelodysplastic Syndrome.” Hematology, Transfusion and Cell Therapy 45, no. 2: 147–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copley, M. R. , and Eaves C. J.. 2013. “Developmental Changes in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Properties.” Experimental & Molecular Medicine 45, no. 11: e55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dávalos, V. , Súarez‐López L., Castaño J., et al. 2012. “Human SMC2 Protein, a Core Subunit of Human Condensin Complex, Is a Novel Transcriptional Target of the WNT Signaling Pathway and a New Therapeutic Target.” Journal of Biological Chemistry 287, no. 52: 43472–43481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, A. J. , and Zon L. I.. 2004. “The ‘Definitive’ (and ‘Primitive’) Guide to Zebrafish Hematopoiesis.” Oncogene 23, no. 43: 7233–7246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Keersmaecker, K. , Porcu M., Cox L., et al. 2014. “NUP214‐ABL1‐Mediated Cell Proliferation in T‐Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Is Dependent on the LCK Kinase and Various Interacting Proteins.” Haematologica 99, no. 1: 85–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Garza, A. , Cameron R. C., Nik S., Payne S. G., and Bowman T. V.. 2016. “Spliceosomal Component Sf3b1 Is Essential for Hematopoietic Differentiation in Zebrafish.” Experimental Hematology 44, no. 9: 826–837.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dotson, J. L. , and Lebowicz Y.. 2023. Myelodysplastic Syndrome. StatPearls. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enciso, J. , Mendoza L., and Pelayo R.. 2015. “Normal Vs. Malignant Hematopoiesis: The Complexity of Acute Leukemia Through Systems Biology.” Frontiers in Genetics 6: 290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espanola, S. G. , Song H., Ryu E., et al. 2020. “Haematopoietic Stem Cell‐Dependent Notch Transcription Is Mediated by p53 Through the Histone Chaperone Supt16h.” Nature Cell Biology 22, no. 12: 1411–1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flach, J. , Jann J. C., Knaflic A., et al. 2021. “Replication Stress Signaling Is a Therapeutic Target in Myelodysplastic Syndromes With Splicing Factor Mutations.” Haematologica 106, no. 11: 2906–2917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follo, M. Y. , Pellagatti A., Armstrong R. N., et al. 2019. “Response of High‐Risk MDS to Azacitidine and Lenalidomide Is Impacted by Baseline and Acquired Mutations in a Cluster of Three Inositide‐Specific Genes.” Leukemia 33, no. 9: 2276–2290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganan‐Gomez, I. , Yang H., Ma F., et al. 2022. “Stem Cell Architecture Drives Myelodysplastic Syndrome Progression and Predicts Response to Venetoclax‐Based Therapy.” Nature Medicine 28, no. 3: 557–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge, L. , Zhang R., Wan F., et al. 2014. “TET2 Plays an Essential Role in Erythropoiesis by Regulating Lineage‐Specific Genes Via DNA Oxidative Demethylation in a Zebrafish Model.” Molecular and Cellular Biology 34, no. 6: 989–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glauche, I. , Moore K., Thielecke L., Horn K., Loeffler M., and Roeder I.. 2009. “Stem Cell Proliferation and Quiescence—Two Sides of the Same Coin.” PLoS Computational Biology 5, no. 7: e1000447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gore, A. V. , Pillay L. M., Venero Galanternik M., and Weinstein B. M.. 2018. “The Zebrafish: A Fintastic Model for Hematopoietic Development and Disease.” WIREs Developmental Biology 7, no. 3: e312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosling, K. M. , Makaroff L. E., Theodoratos A., et al. 2007. “A Mutation in a Chromosome Condensin II Subunit, Kleisin β, Specifically Disrupts T Cell Development.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104, no. 30: 12445–12450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graumann, P. 2001. “SMC Proteins in Bacteria: Condensation Motors for Chromosome Segregation?” Biochimie 83, no. 1: 53–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagstrom, K. A. , Holmes V. F., Cozzarelli N. R., and Meyer B. J.. 2002. “ C. elegans Condensin Promotes Mitotic Chromosome Architecture, Centromere Organization, and Sister Chromatid Segregation During Mitosis and Meiosis.” Genes & Development 16, no. 6: 729–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han, S. H. , Kim S. H., Kim H. J., et al. 2017. “Cobll1 Is Linked to Drug Resistance and Blastic Transformation in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia.” Leukemia 31, no. 7: 1532–1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano, T. 2012. “Condensins: Universal Organizers of Chromosomes With Diverse Functions.” Genes & Development 26, no. 15: 1659–1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano, T. , Kobayashi R., and Hirano M.. 1997. “Condensins, Chromosome Condensation Protein Complexes Containing XCAP‐C, XCAP‐E and a Xenopus Homolog of the Drosophila Barren Protein.” Cell 89, no. 4: 511–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota, T. , Gerlich D., Koch B., Ellenberg J., and Peters J. M.. 2004. “Distinct Functions of Condensin I and II in Mitotic Chromosome Assembly.” Journal of Cell Science 117, no. Pt 26: 6435–6445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, R. B. , and Shapiro L.. 1999. “The Caulobacter Crescentus smc Gene Is Required for Cell Cycle Progression and Chromosome Segregation.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 96, no. 19: 10661–10666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L. , Zhou J., Zhong D., et al. 2017. “Overexpression of SMC4 Activates TGFβ/Smad Signaling and Promotes Aggressive Phenotype in Glioma Cells.” Oncogenesis 6, no. 3: e301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin, X. , Fang Y., Hu Y., et al. 2017. “Synergistic Activity of the Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor Trichostatin A and the Proteasome Inhibitor PS‐341 Against Taxane‐Resistant Ovarian Cancer Cell Lines.” Oncology Letters 13, no. 6: 4619–4626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J. W. , Kim Y., Lee Y., Myung K., Kim Y. H., and Oh C. K.. 2020. “AML Poor Prognosis Factor, TPD52, Is Associated With the Maintenance of Haematopoietic Stem Cells Through Regulation of Cell Proliferation.” Journal of Cellular Biochemistry 122, no. 3‐4: 403–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. H. , Youn Y., Kim K. T., Jang G., and Hwang J. H.. 2019. “Non‐SMC Condensin I Complex Subunit H Mediates Mature Chromosome Condensation and DNA Damage in Pancreatic Cancer Cells.” Scientific Reports 9, no. 1: 17889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klebanow, L. R. , Peshel E. C., Schuster A. T., et al. 2016. “ Drosophila Condensin II Subunit Chromosome‐Associated Protein D3 Regulates Cell Fate Determination Through Non‐Cell‐Autonomous Signaling.” Development 143, no. 15: 2791–2802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutyna, M. M. , Loone S., Saunders V. A., White D. L., Kok C. H., and Hiwase D. K.. 2023. “Solute Carrier Family 29A1 Mediates In Vitro Resistance to Azacitidine in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cell Lines.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 24, no. 4: 3553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane, S. W. , Sykes S. M., Al‐Shahrour F., et al. 2010. “The Apc(min) Mouse Has Altered Hematopoietic Stem Cell Function and Provides a Model for MPD/MDS.” Blood 115, no. 17: 3489–3497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. 2013. “Myelodysplastic Syndrome Hematopoietic Stem Cell.” International Journal of Cancer 133, no. 3: 525–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W. , Liang B., Liu H., et al. 2017. “Overexpression of NonSMC Condensin I Complex Subunit G Serves as a Promising Prognostic Marker and Therapeutic Target for Hepatocellular Carcinoma.” International Journal of Molecular Medicine 40, no. 3: 731–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love, M. I. , Huber W., and Anders S.. 2014. “Moderated Estimation of Fold Change and Dispersion for RNA‐seq Data With DESeq. 2.” Genome Biology 15, no. 12: 550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahony, C. B. , and Bertrand J. Y.. 2019. “How HSCS Colonize and Expand in the Fetal Niche of the Vertebrate Embryo: An Evolutionary Perspective.” Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 7: 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medinger, M. , Drexler B., Lengerke C., and Passweg J.. 2018. “Pathogenesis of Acquired Aplastic Anemia and the Role of the Bone Marrow Microenvironment.” Frontiers in Oncology 8: 587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mian, S. A. , Philippe C., Maniati E., et al. 2023. “Vitamin B5 and Succinyl‐CoA Improve Ineffective Erythropoiesis in SF3B1‐mutated Myelodysplasia.” Science Translational Medicine 15, no. 685: eabn5135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero, S. , Seras‐Franzoso J., Andrade F., et al. 2020. “Intracellular Delivery of Anti‐SMC2 Antibodies Against Cancer Stem Cells.” Pharmaceutics 12, no. 2: 185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North, T. E. , Goessling W., Peeters M., et al. 2009. “Hematopoietic Stem Cell Development Is Dependent on Blood Flow.” Cell 137, no. 4: 736–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochi, Y. , Kon A., Sakata T., et al. 2020. “Combined Cohesin‐RUNX1 Deficiency Synergistically Perturbs Chromatin Looping and Causes Myelodysplastic Syndromes.” Cancer Discovery 10, no. 6: 836–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh, C. K. , Ha M., Han M. E., et al. 2020. “FAM213A Is Linked to Prognostic Significance in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Through Regulation of Oxidative Stress and Myelopoiesis.” Hematological Oncology 38, no. 3: 381–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh, C. K. , Kang J. W., Lee Y., et al. 2020. “Role of kif2c, a Gene Related to ALL Relapse, in Embryonic Hematopoiesis in Zebrafish.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21, no. 9: 3127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono, T. , Losada A., Hirano M., Myers M. P., Neuwald A. F., and Hirano T.. 2003. “Differential Contributions of Condensin I and Condensin II to Mitotic Chromosome Architecture in Vertebrate Cells.” Cell 115, no. 1: 109–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palou, R. , Dhanaraman T., Marrakchi R., Pascariu M., Tyers M., and D'Amours D.. 2018. “Condensin ATpase Motifs Contribute Differentially to the Maintenance of Chromosome Morphology and Genome Stability.” PLoS Biology 16, no. 6: e2003980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passegué, E. , Jamieson C. H. M., Ailles L. E., and Weissman I. L.. 2003. “Normal and Leukemic Hematopoiesis: Are Leukemias a Stem Cell Disorder or a Reacquisition of Stem Cell Characteristics?” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 100, no. Suppl 1: 11842–11849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quivoron, C. , Couronné L., Della Valle V., et al. 2011. “TET2 Inactivation Results in Pleiotropic Hematopoietic Abnormalities in Mouse and Is a Recurrent Event During Human Lymphomagenesis.” Cancer Cell 20, no. 1: 25–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, H. L. , Soares Maia A. R., Costa M. B., et al. 2016. “Influence of Functional Polymorphisms in DNA Repair Genes of Myelodysplastic Syndrome.” Leukemia Research 48: 62–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risitano, A. , Maciejewski J., Selleri C., Rotoli B., M. Risitano A., and P. Maciejewski J.. 2007. “Function and Malfunction of Hematopoietic Stem Cells in Primary Bone Marrow Failure Syndromes.” Current Stem Cell Research & Therapy 2, no. 1: 39–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, A. L. , Avagyan S., Gansner J. M., and Zon L. I.. 2016. “Understanding the Regulation of Vertebrate Hematopoiesis and Blood Disorders—Big Lessons From a Small Fish.” FEBS Letters 590, no. 22: 4016–4033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, L. 1996. “The Control of Hematopoiesis and Leukemia: From Basic Biology to the Clinic.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 93, no. 10: 4742–4749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawai, C. M. , Babovic S., Upadhaya S., et al. 2016. “Hematopoietic Stem Cells Are the Major Source of Multilineage Hematopoiesis in Adult Animals.” Immunity 45, no. 3: 597–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seipold, S. , Priller F. C., Goldsmith P., Harris W. A., Baier H., and Abdelilah‐Seyfried S.. 2009. “Non‐SMC Condensin I Complex Proteins Control Chromosome Segregation and Survival of Proliferating Cells in the Zebrafish Neural Retina.” BMC Developmental Biology 9: 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seita, J. , and Weissman I. L.. 2010. “Hematopoietic Stem Cell: Self‐Renewal Versus Differentiation.” WIREs Systems Biology and Medicine 2, no. 6: 640–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalem, O. , Sanjana N. E., Hartenian E., et al. 2014. “Genome‐Scale CRISPR‐Cas9 Knockout Screening in Human Cells.” Science 343, no. 6166: 84–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shastri, A. , Will B., Steidl U., and Verma A.. 2017. “Stem and Progenitor Cell Alterations in Myelodysplastic Syndromes.” Blood 129, no. 12: 1586–1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevyrev, D. , Tereshchenko V., Berezina T. N., and Rybtsov S.. 2023. “Hematopoietic Stem Cells and the Immune System in Development and Aging.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 24, no. 6: 5862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skibbens, R. V. 2019. “Condensins and Cohesins—One of These Things Is Not Like the Other!.” Journal of Cell Science 132, no. 3: 220491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S. , Han Y., Liu J., et al. 2014. “Trichostatin A Targets the Mitochondrial Respiratory Chain, Increasing Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species Production to Trigger Apoptosis in Human Breast Cancer Cells.” PLoS One 9, no. 3: e91610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szklarczyk, D. , Kirsch R., Koutrouli M., et al. 2023. “The STRING Database in 2023: Protein–Protein Association Networks and Functional Enrichment Analyses for Any Sequenced Genome of Interest.” Nucleic Acids Research 51, no. D1: D638–D646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamplin, O. J. , Durand E. M., Carr L. A., et al. 2015. “Hematopoietic Stem Cell Arrival Triggers Dynamic Remodeling of the Perivascular Niche.” Cell 160, no. 1‐2: 241–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traver, D. , Herbomel P., Patton E. E., et al. 2003. “The Zebrafish as a Model Organism to Study Development of the Immune System.” Advances in Immunology 81: 253–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veiga, C. B. , Lawrence E. M., Murphy A. J., Herold M. J., and Dragoljevic D.. 2021. “Myelodysplasia Syndrome, Clonal Hematopoiesis and Cardiovascular Disease.” Cancers 13, no. 8: 1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wattrus, S. J. , and Zon L. I.. 2018. “Stem Cell Safe Harbor: The Hematopoietic Stem Cell Niche in Zebrafish.” Blood Advances 2, no. 21: 3063–3069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward, J. , Taylor G. C., Soares D. C., et al. 2016. “Condensin II Mutation Causes T‐Cell Lymphoma Through Tissue‐Specific Genome Instability.” Genes & Development 30, no. 19: 2173–2186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y. , Leung C. G., Lee D. C., Kennedy B. K., and Crispino J. D.. 2006. “MTb, the Murine Homolog of Condensin II Subunit CAP‐G2, Represses Transcription and Promotes Erythroid Cell Differentiation.” Leukemia 20, no. 7: 1261–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Y. , Lv J., Zhang C., Wang L., Ma D., and Liu F.. 2017. “The Vascular Niche Regulates Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cell Lodgment and Expansion via klf6a‐ccl25b.” Developmental Cell 42, no. 4: 349–362.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, D. , and Park C. Y.. 2021. “Stem Cells in the Myelodysplastic Syndromes.” Frontiers in Aging 2: 719010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. , Liu F., Zhang C., et al. 2020. “Non‐SMC Condensin I Complex Subunit D2 Is a Prognostic Factor in Triple‐Negative Breast Cancer for the Ability to Promote Cell Cycle and Enhance Invasion.” American Journal of Pathology 190, no. 1: 37–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhen, F. , Lan Y., Yan B., Zhang W., and Wen Z.. 2013. “Hemogenic Endothelium Specification and Hematopoietic Stem Cell Maintenance Employ Distinct Scl Isoforms.” Development 140, no. 19: 3977–3985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T. , Chen P., Gu J., et al. 2015. “Potential Relationship Between Inadequate Response to DNA Damage and Development of Myelodysplastic Syndrome.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 16, no. 1: 966–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.