Abstract

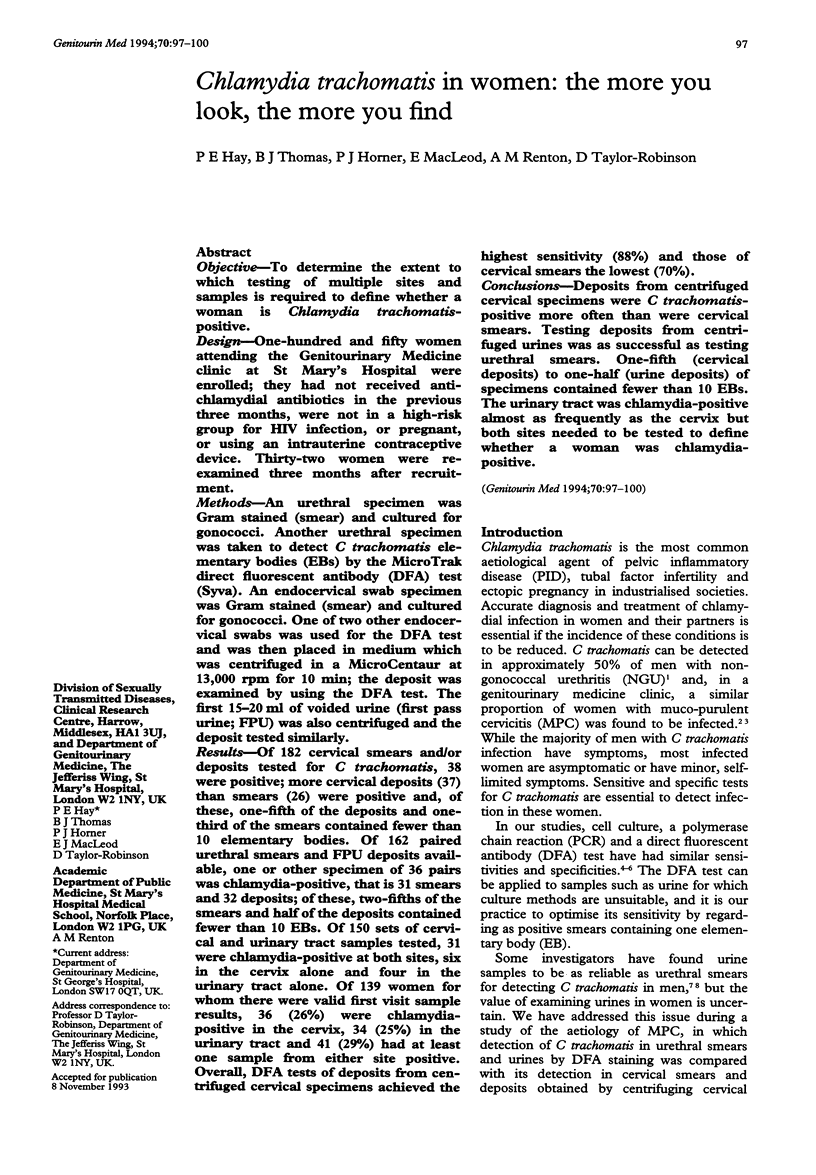

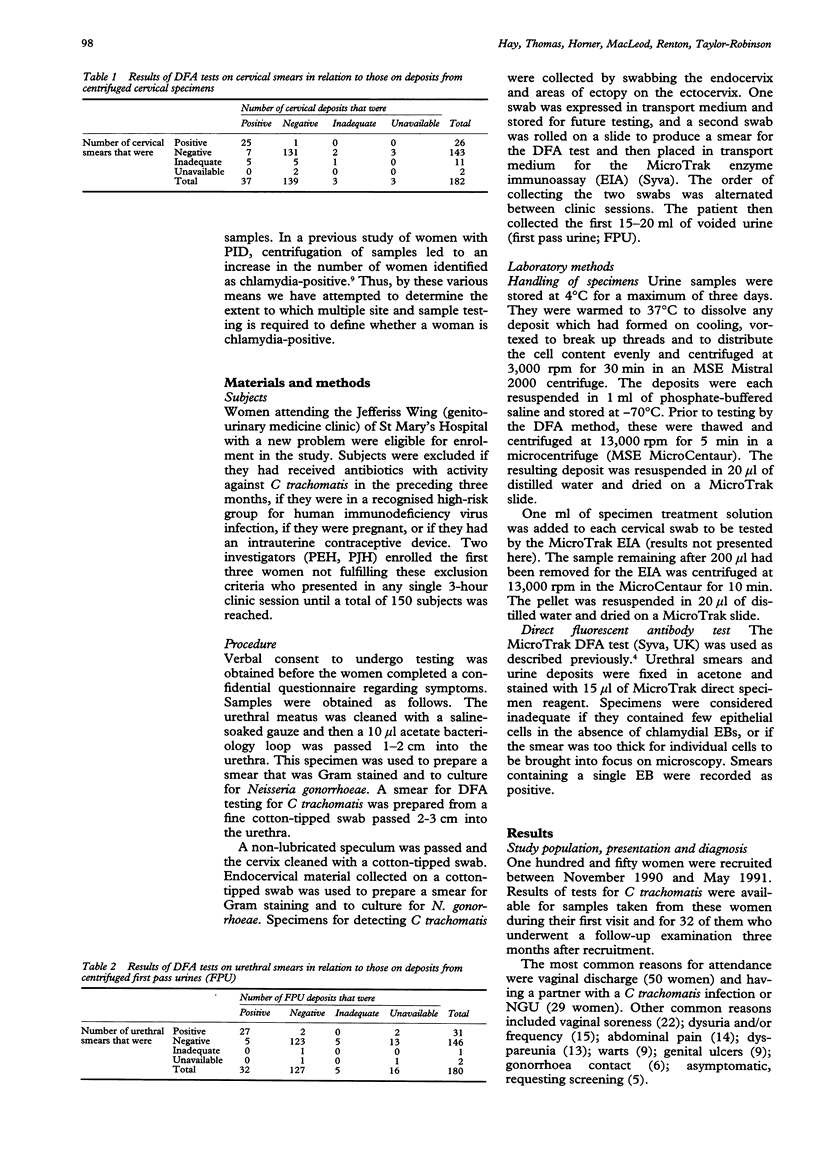

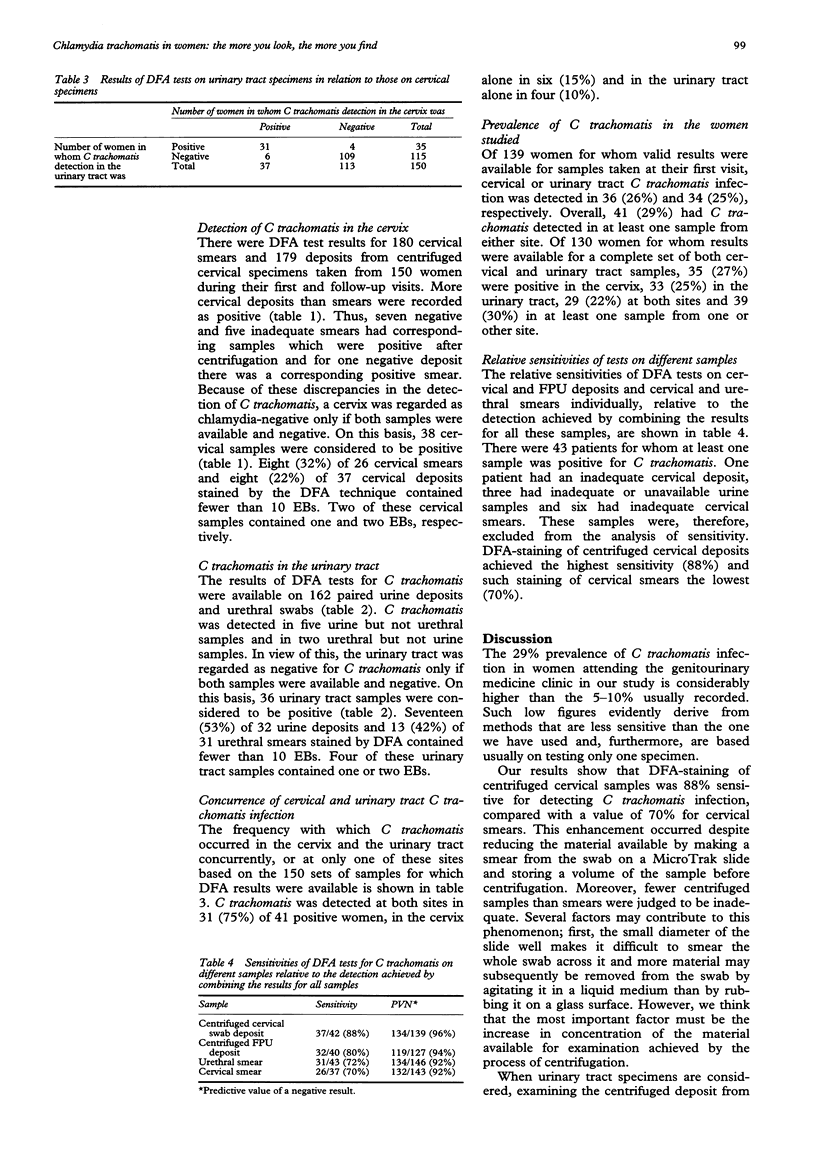

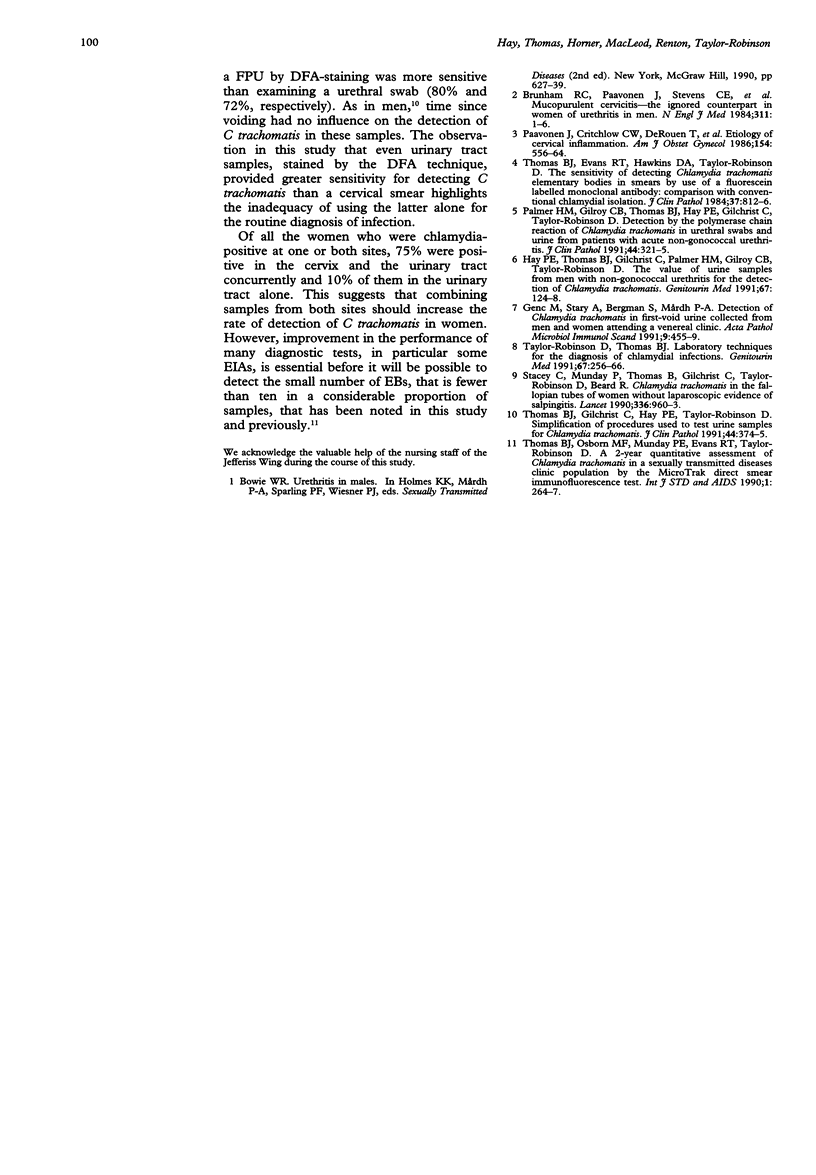

OBJECTIVE--To determine the extent to which testing of multiple sites and samples is required to define whether a woman is Chlamydia trachomatis-positive. DESIGN--One-hundred and fifty women attending the Genitourinary Medicine clinic at St Mary's Hospital were enrolled; they had not received antichlamydial antibiotics in the previous three months, were not in a high-risk group for HIV infection, or pregnant, or using an intrauterine contraceptive device. Thirty-two women were re-examined three months after recruitment. METHODS--An urethral specimen was Gram stained (smear) and cultured for gonococci. Another urethral specimen was taken to detect C trachomatis elementary bodies (EBs) by the MicroTrak direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) test (Syva). An endocervical swab specimen was Gram stained (smear) and cultured for gonococci. One of two other endocervical swabs was used for the DFA test and was then placed in medium which was centrifuged in a MicroCentaur at 13,000 rpm for 10 min; the deposit was examined by using the DFA test. The first 15-20 ml of voided urine (first pass urine; FPU) was also centrifuged and the deposit tested similarly. RESULTS--Of 182 cervical smears and/or deposits tested for C trachomatis, 38 were positive; more cervical deposits (37) than smears (26) were positive and, of these, one-fifth of the deposits and one-third of the smears contained fewer than 10 elementary bodies. Of 162 paired urethral smears and FPU deposits available, one or other specimen of 36 pairs was chlamydia-positive, that is 31 smears and 32 deposits; of these, two-fifths of the smears and half of the deposits contained fewer than 10 EBs. Of 150 sets of cervical and urinary tract samples tested, 31 were chlamydia-positive at both sites, six in the cervix alone and four in the urinary tract alone. Of 139 women for whom there were valid first visit sample results, 36 (26%) were chlamydia-positive in the cervix, 34 (25%) in the urinary tract and 41 (29%) had at least one sample from either site positive. Overall, DFA tests of deposits from centrifuged cervical specimens achieved the highest sensitivity (88%) and those of cervical smears the lowest (70%). CONCLUSIONS--Deposits from centrifuged cervical specimens were C trachomatis-positive more often than were cervical smears. Testing deposits from centrifuged urines was as successful as testing urethral smears. One-fifth (cervical deposits) to one-half (urine deposits) of specimens contained fewer than 10 EBs. The urinary tract was chlamydia-positive almost as frequently as the cervix but both sites needed to be tested to define whether a woman was chlamydia-positive.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Brunham R. C., Paavonen J., Stevens C. E., Kiviat N., Kuo C. C., Critchlow C. W., Holmes K. K. Mucopurulent cervicitis--the ignored counterpart in women of urethritis in men. N Engl J Med. 1984 Jul 5;311(1):1–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198407053110101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genç M., Stary A., Bergman S., Mårdh P. A. Detection of Chlamydia trachomatis in first-void urine collected from men and women attending a venereal clinic. APMIS. 1991 May;99(5):455–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay P. E., Thomas B. J., Gilchrist C., Palmer H. M., Gilroy C. B., Taylor-Robinson D. The value of urine samples from men with non-gonococcal urethritis for the detection of Chlamydia trachomatis. Genitourin Med. 1991 Apr;67(2):124–128. doi: 10.1136/sti.67.2.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paavonen J., Critchlow C. W., DeRouen T., Stevens C. E., Kiviat N., Brunham R. C., Stamm W. E., Kuo C. C., Hyde K. E., Corey L. Etiology of cervical inflammation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1986 Mar;154(3):556–564. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(86)90601-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacey C., Munday P., Thomas B., Gilchrist C., Taylor-Robinson D., Beard R. Chlamydia trachomatis in the fallopian tubes of women without laparoscopic evidence of salpingitis. Lancet. 1990 Oct 20;336(8721):960–963. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92418-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor-Robinson D., Thomas B. J. Laboratory techniques for the diagnosis of chlamydial infections. Genitourin Med. 1991 Jun;67(3):256–266. doi: 10.1136/sti.67.3.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas B. J., Evans R. T., Hawkins D. A., Taylor-Robinson D. Sensitivity of detecting Chlamydia trachomatis elementary bodies in smears by use of a fluorescein labelled monoclonal antibody: comparison with conventional chlamydial isolation. J Clin Pathol. 1984 Jul;37(7):812–816. doi: 10.1136/jcp.37.7.812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas B. J., Osborn M. F., Munday P. E., Evans R. T., Taylor-Robinson D. A 2-year quantitative assessment of Chlamydia trachomatis in a sexually transmitted diseases clinic population by the MicroTrak direct smear immunofluorescence test. Int J STD AIDS. 1990 Jul;1(4):264–267. doi: 10.1177/095646249000100407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]