Abstract

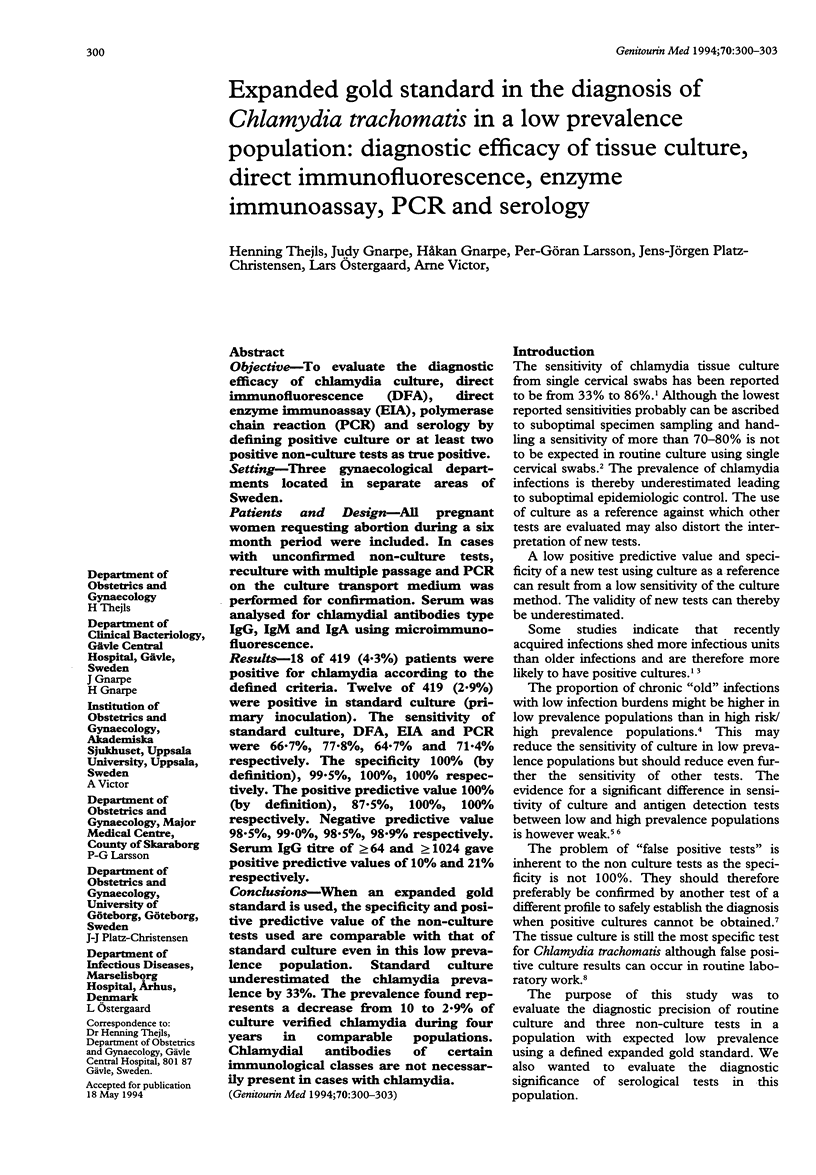

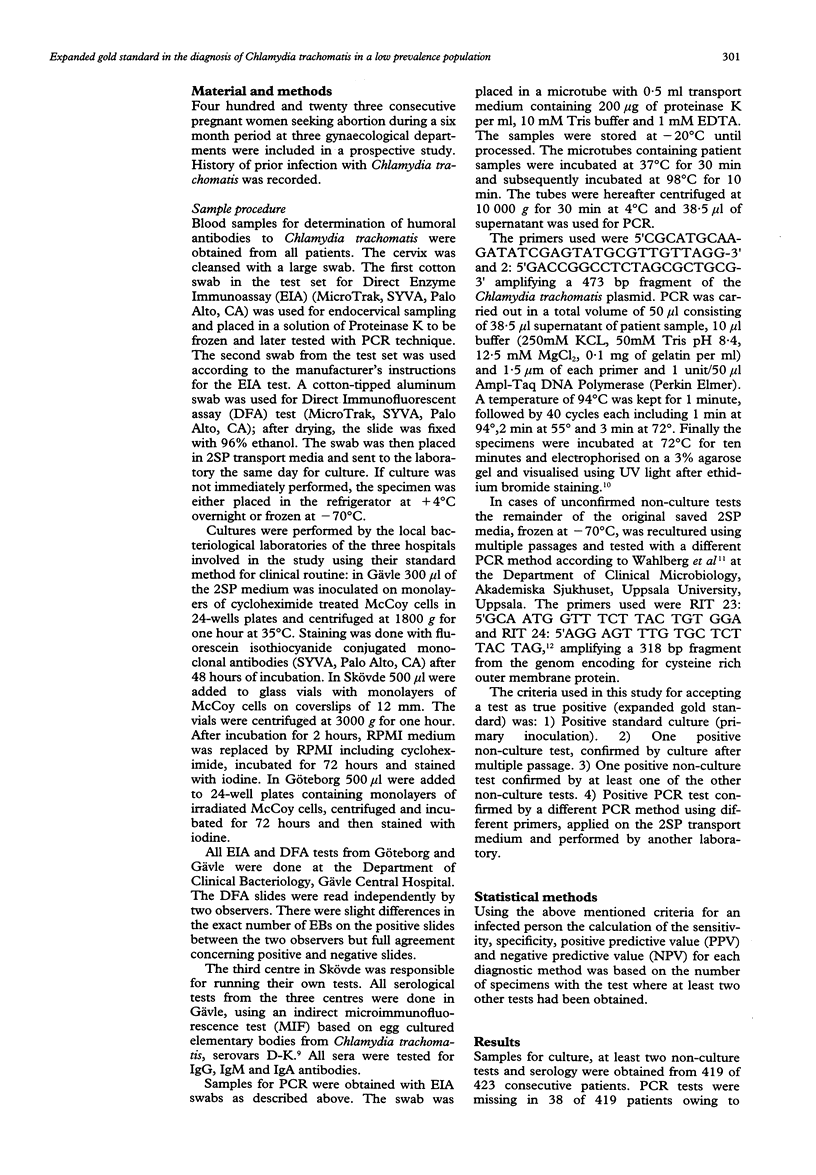

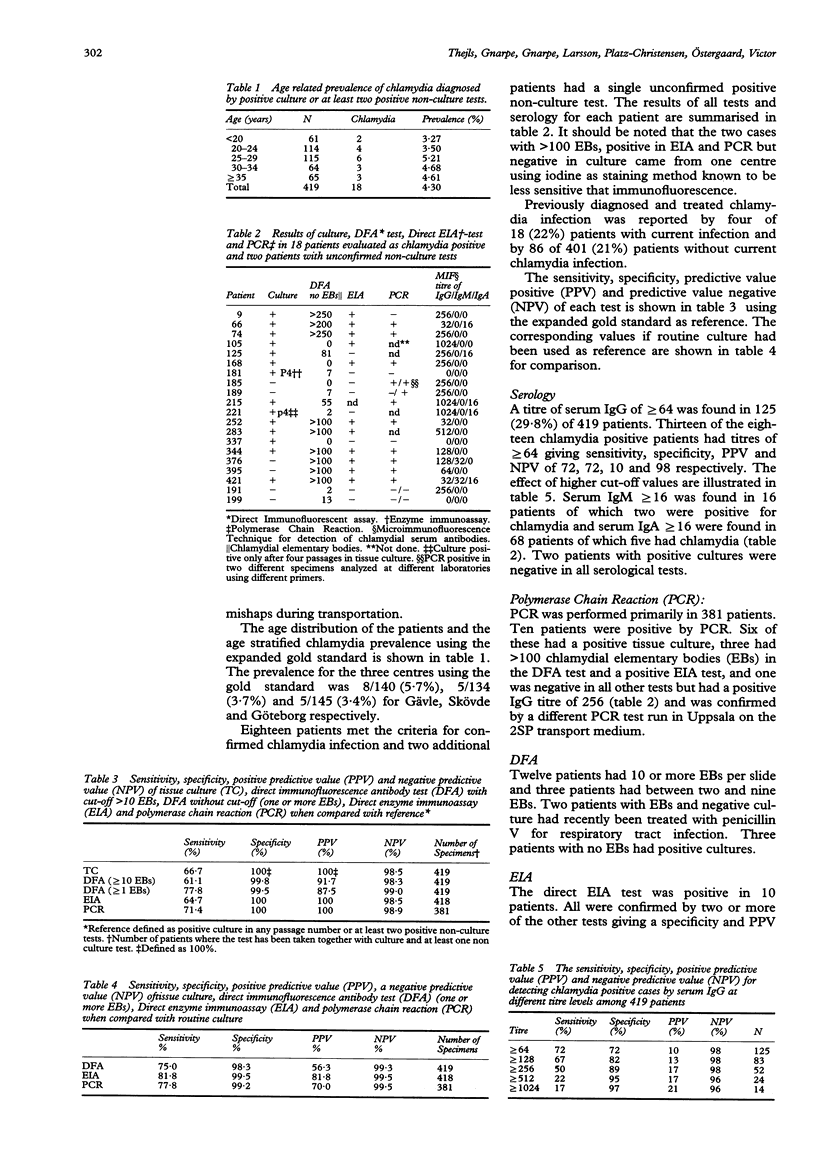

OBJECTIVE--To evaluate the diagnostic efficacy of chlamydia culture, direct immunofluorescence (DFA), direct enzyme immunoassay (EIA), polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and serology by defining positive culture or at least two positive non-culture tests as true positive. SETTING--Three gynaecological departments located in separate areas of Sweden. PATIENTS AND DESIGN--All pregnant women requesting abortion during a six month period were included. In cases with unconfirmed non-culture tests, reculture with multiple passage and PCR on the culture transport medium was performed for confirmation. Serum was analysed for chlamydial antibodies type IgG, IgM and IgA using microimmunofluorescence. RESULTS--18 of 419 (4.3%) patients were positive for chlamydia according to the defined criteria. Twelve of 419 (2.9%) were positive in standard culture (primary inoculation). The sensitivity of standard culture, DFA, EIA and PCR were 66.7%, 77.8%, 64.7% and 71.4% respectively. The specificity 100% (by definition), 99.5%, 100%, 100% respectively. The positive predictive value 100% (by definition), 87.5%, 100%, 100% respectively. Negative predictive value 98.5%, 99.0%, 98.5%, 98.9% respectively. Serum IgG titre of > or = 64 and > or = 1024 gave positive predictive values of 10% and 21% respectively. CONCLUSIONS--When an expanded gold standard is used, the specificity and positive predictive value of the non-culture tests used are comparable with that of standard culture even in this low prevalence population. Standard culture underestimated the chlamydia prevalence by 33%. The prevalence found represents a decrease from 10 to 2.9% of culture verified chlamydia during four years in comparable populations. Chlamydial antibodies of certain immunological classes are not necessarily present in cases with chlamydia.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Barnes R. C. Laboratory diagnosis of human chlamydial infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1989 Apr;2(2):119–136. doi: 10.1128/cmr.2.2.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunham R. C., Kuo C. C., Cles L., Holmes K. K. Correlation of host immune response with quantitative recovery of Chlamydia trachomatis from the human endocervix. Infect Immun. 1983 Mar;39(3):1491–1494. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.3.1491-1494.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke I. N., Ward M. E., Lambden P. R. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of a developmentally regulated cysteine-rich outer membrane protein from Chlamydia trachomatis. Gene. 1988 Nov 30;71(2):307–314. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90047-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gann P. H., Herrmann J. E., Candib L., Hudson R. W. Accuracy of Chlamydia trachomatis antigen detection methods in a low-prevalence population in a primary care setting. J Clin Microbiol. 1990 Jul;28(7):1580–1585. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.7.1580-1585.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang D., Sellors J. W., Mahony J. B., Pickard L., Chernesky M. A. Effects of broadening the gold standard on the performance of a chemiluminometric immunoassay to detect Chlamydia trachomatis antigens in centrifuged first void urine and urethral swab samples from men. Sex Transm Dis. 1992 Nov-Dec;19(6):315–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg J. A. Clinical and laboratory considerations of culture vs antigen assays for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis from genital specimens. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1989 May;113(5):453–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson P. G., Platz-Christensen J. J., Thejls H., Forsum U., Påhlson C. Incidence of pelvic inflammatory disease after first-trimester legal abortion in women with bacterial vaginosis after treatment with metronidazole: a double-blind, randomized study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992 Jan;166(1 Pt 1):100–103. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(92)91838-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostergaard L., Traulsen J., Birkelund S., Christiansen G. Evaluation of urogenital Chlamydia trachomatis infections by cell culture and the polymerase chain reaction using a closed system. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1991 Dec;10(12):1057–1061. doi: 10.1007/BF01984929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rettig P. J. Chlamydial infections in pediatrics: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1986 Jan-Feb;5(1):158–162. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198601000-00052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachter J., Stamm W. E., Chernesky M. A., Hook E. W., 3rd, Jones R. B., Judson F. N., Kellogg J. A., LeBar B., Mårdh P. A., McCormack W. M. Nonculture tests for genital tract chlamydial infection. What does the package insert mean, and will it mean the same thing tomorrow? Sex Transm Dis. 1992 Sep-Oct;19(5):243–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacey C., Munday P., Thomas B., Gilchrist C., Taylor-Robinson D., Beard R. Chlamydia trachomatis in the fallopian tubes of women without laparoscopic evidence of salpingitis. Lancet. 1990 Oct 20;336(8721):960–963. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92418-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor-Robinson D., Thomas B. J. Laboratory techniques for the diagnosis of chlamydial infections. Genitourin Med. 1991 Jun;67(3):256–266. doi: 10.1136/sti.67.3.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thejls H., Gnarpe J., Gnarpe H., Larsson G. Age-related decrease in prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis among pregnant women. Sex Transm Dis. 1991 Jul-Sep;18(3):137–137. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199107000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas B. J., Osborn M. F., Munday P. E., Evans R. T., Taylor-Robinson D. A 2-year quantitative assessment of Chlamydia trachomatis in a sexually transmitted diseases clinic population by the MicroTrak direct smear immunofluorescence test. Int J STD AIDS. 1990 Jul;1(4):264–267. doi: 10.1177/095646249000100407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treharne J. D., Darougar S., Jones B. R. Modification of the microimmunofluorescence test to provide a routine serodiagnostic test for chlamydial infection. J Clin Pathol. 1977 Jun;30(6):510–517. doi: 10.1136/jcp.30.6.510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlberg J., Lundeberg J., Hultman T., Uhlén M. General colorimetric method for DNA diagnostics allowing direct solid-phase genomic sequencing of the positive samples. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990 Sep;87(17):6569–6573. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]