Abstract

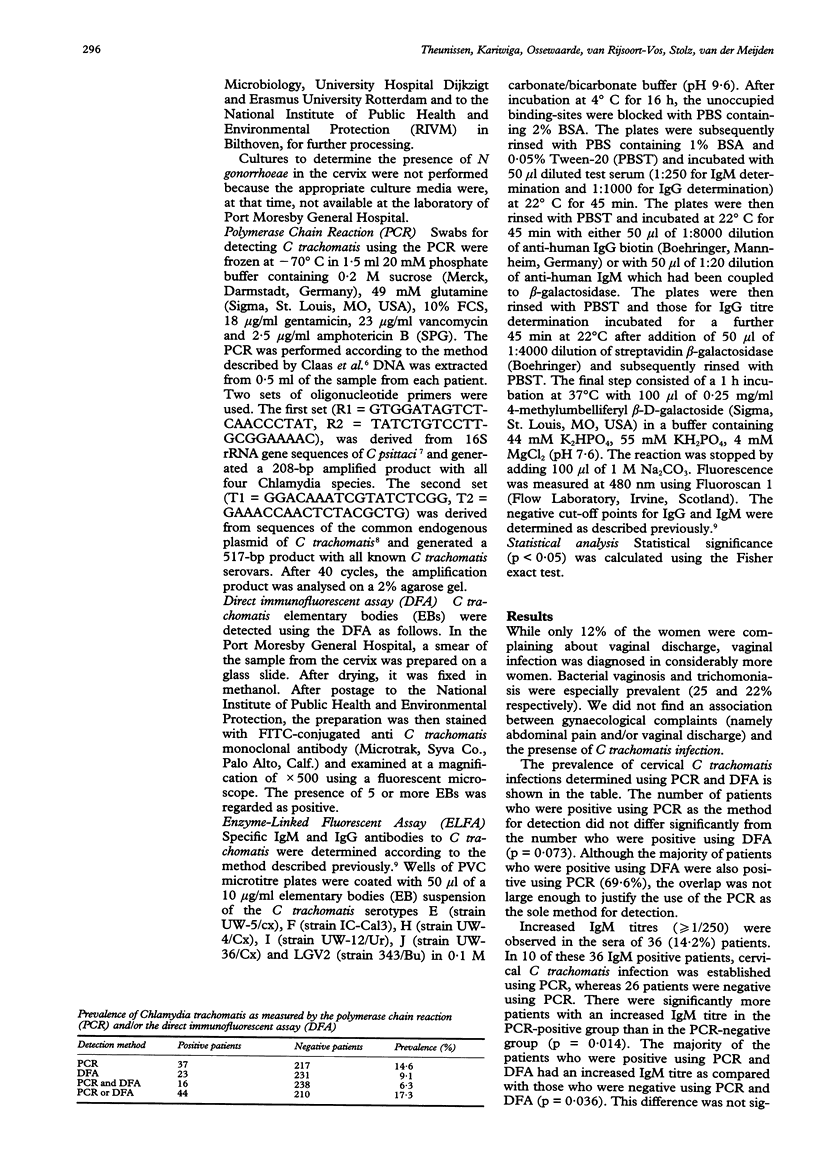

OBJECTIVE--To determine the prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis infection in women attending a family planning clinic in Papua New Guinea, in the period between April and June 1991. SETTING--The outpatient department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of Port Moresby General Hospital, Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, the departments of Dermato-Venereology and Clinical Microbiology of the Erasmus University, Rotterdam, The Netherlands and the National Institute of Public Health and Environmental Protection, Bilthoven, The Netherlands. PATIENTS--A total of 254 consecutive women who attended the family planning clinic at Port Moresby General Hospital, Papua New Guinea were enrolled into this study. METHODS--Cervical infections with C trachomatis were diagnosed using the direct immunofluorescent assay (DFA) and the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Serum IgM and IgG antibodies directed against C trachomatis were detected using the enzyme-linked fluorescent assay (ELFA). RESULTS--The prevalence of C trachomatis was 14.6% using the PCR, 9.1% using the DFA and 17.3% when the results of the PCR and the DFA were combined. An elevated IgM titre was observed in 14.2% of the women, whereas 44.1% had an elevated IgG titre. The titres of IgM or IgG were significantly higher in women who were positive using the PCR or the DFA than in those who were negative in both the PCR and the DFA (p = 0.032 and p = 0.0046, respectively). CONCLUSION--Cervical infection by C trachomatis can be considered a major health problem in at least the studied population in Papua New Guinea. The prevalence of C trachomatis infection is at least comparable with that in groups with a high prevalence in industrialized countries. Effective screening and treatment programmes are imperative to combat this problem.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Barnes R. C. Laboratory diagnosis of human chlamydial infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1989 Apr;2(2):119–136. doi: 10.1128/cmr.2.2.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanding J., Hirsch L., Stranton N., Wright T., Aarnaes S., de la Maza L., Peterson E. M. Comparison of the Clearview Chlamydia, the PACE 2 assay, and culture for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis from cervical specimens in a low-prevalence population. J Clin Microbiol. 1993 Jun;31(6):1622–1625. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.6.1622-1625.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels H., Nyongo A., Temmerman M., Quint W. G., Van Marck E., Eylenbosch W. J. Cervical cancer screening and detection of genital HPV-infection and chlamydial infection by PCR in different groups of Kenyan women. Ann Soc Belg Med Trop. 1992 Mar;72(1):53–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail S. O., Ahmed H. J., Jama M. A., Omer K., Omer F. M., Brundin M., Olofsson M. B., Grillner L., Bygdeman S. Syphilis, gonorrhoea and genital chlamydial infection in a Somali village. Genitourin Med. 1990 Apr;66(2):70–75. doi: 10.1136/sti.66.2.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klufio C. A., Amoa A. B., Delamare O., Kariwiga G. Endocervical Chlamydia trachomatis infection in pregnancy: direct test and clinico-sociodemographic survey of pregnant patients at the Port Moresby General Hospital antenatal clinic to determine prevalence and risk markers. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992 Feb;32(1):43–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.1992.tb01897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclerc A., Frost E., Collet M., Goeman J., Bedjabaga L. Urogenital Chlamydia trachomatis in Gabon: an unrecognised epidemic. Genitourin Med. 1988 Oct;64(5):308–311. doi: 10.1136/sti.64.5.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posada A. B., Jonasson J., de Linares L., Bygdeman S. Prevalence of urogenital Chlamydia trachomatis infection in El Salvador. I. Infection during pregnancy and perinatal transmission. Int J STD AIDS. 1992 Jan-Feb;3(1):33–37. doi: 10.1177/095646249200300108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puolakkainen M., Vesterinen E., Purola E., Saikku P., Paavonen J. Persistence of chlamydial antibodies after pelvic inflammatory disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1986 May;23(5):924–928. doi: 10.1128/jcm.23.5.924-928.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somji S., Kazmi S. U., Sultana A. Prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis infections in Karachi, Pakistan. Jpn J Med Sci Biol. 1991 Oct-Dec;44(5-6):239–243. doi: 10.7883/yoken1952.44.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sriprakash K. S., Macavoy E. S. Characterization and sequence of a plasmid from the trachoma biovar of Chlamydia trachomatis. Plasmid. 1987 Nov;18(3):205–214. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(87)90063-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theunissen J. J., van Heijst B. Y., Chin-A-Lien R. A., Wagenvoort J. H., Stolz E., Michel M. F. Detection of IgG, IgM and IgA antibodies in patients with uncomplicated Chlamydia trachomatis infection: a comparison between enzyme linked immunofluorescent assay and isolation in cell culture. Int J STD AIDS. 1993 Jan-Feb;4(1):43–48. doi: 10.1177/095646249300400109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treharne J. D., Darougar S., Simmons P. D., Thin R. N. Rapid diagnosis of chlamydial infection of the cervix. Br J Vener Dis. 1978 Dec;54(6):403–408. doi: 10.1136/sti.54.6.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisburg W. G., Hatch T. P., Woese C. R. Eubacterial origin of chlamydiae. J Bacteriol. 1986 Aug;167(2):570–574. doi: 10.1128/jb.167.2.570-574.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]